Abstract

The cytokine gamma-interferon (IFNγ) activates cell-autonomous immunity against intracellular bacterial and protozoan pathogens by inducing a slew of antimicrobial proteins, some of which hinge upon immunity-related GTPases (IRGs) for their function. Three regulatory IRG clade M (Irgm) proteins chaperone about 20 effector IRGs (GKS IRGs) to localize to pathogen-containing vacuoles (PVs) within mouse cells, initiating a cascade that results in PV elimination and killing of PV-resident pathogens. However, the mechanisms that allow IRGs to identify and traffic specifically to “non-self” PVs have remained elusive. Integrating recent findings demonstrating direct interactions between GKS IRGs and lipids with previous work, we propose that three attributes mark PVs as GKS IRG targets: the absence of membrane-bound Irgm proteins, Atg8 lipidation, and the presence of specific lipid species. Combinatorial recognition of these three distinct signals may have evolved as a mechanism to ensure safe delivery of potent host antimicrobial effectors exclusively to PVs.

Introduction

Most non-immune cells are equipped with cell-intrinsic defense programs to protect against intracellular bacterial and protozoal pathogens, and these programs are frequently activated by cytokines called interferons [1]. While IFN signaling triggers a variety of different defense mechanisms in different cell types, many of these responses are conducted by families of IFN-inducible GTPases. Type I IFNs induce the Mx family of proteins, which interfere with viral replication to conduct antiviral immunity. Among the defense programs induced in response to both type I and type II interferon (IFNγ) are the p65 guanylate binding proteins (GBPs) and the p47 immunity-related GTPases (IRGs), which conduct defense against viral, bacterial, and protozoan pathogens [2,3].

Both the IRG and GBP families are structurally related to dynamins, GTPases that function in membrane biology and vesicle trafficking. The mouse IRG family consists of ~20 cytosolic effector IRGs that contain a canonical GxxxxGKS amino acid sequence in the P-loop of the G-domain, and three membrane-bound regulatory IRG clade M (Irgm) proteins that contain a non-canonical GxxxxGMS sequence (Figure 1,[4]). Effector GKS IRGs have been shown to target to and colocalize with intracellular pathogens, although the specific effector mechanism of each individual GKS IRG has not been shown. However, it has been observed that IRG-targeted PV membranes (PVMs) vesiculate and rupture, and it is thought that IRGs via their membrane binding and GTPase activity may directly mediate PVM disruption, exposing luminal pathogens for destruction by cytosolic defenses [5–7]. Deletion of individual effector IRGs results in partial defects in resistance to certain intracellular pathogens, but deletion of mouse Irgm1 and/or Irgm3, which reside on host organelle membranes, results in a failure of GKS IRGs to target to intracellular pathogens [2], leading to broad and severe defects in resistance to intracellular bacterial and protozoal pathogens including Chlamydia trachomatis and Toxoplasma gondii (Table 1). Thus, the murine IRG family comprises a robust IFNγ-inducible antimicrobial program, with Irgm proteins orchestrating the subcellular localization and activity of the cytosolic effector GKS IRGs.

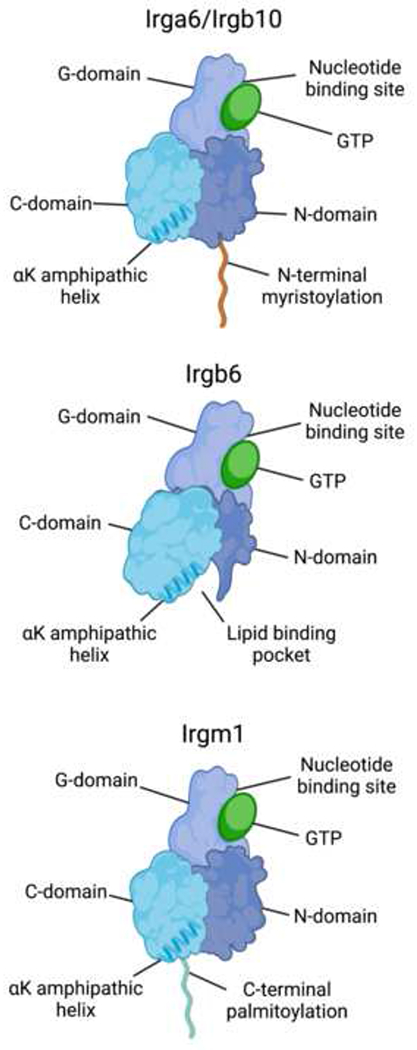

Figure 1. Structural features of IRGs.

All IRGs contain a C-domain, G-domain, and N-domain. The G-domain contains the nucleotide binding pocket, with GKS IRGs such as Irga6, Irgb6, and Irgb10 containing a canonical GxxxxGKS amino acid sequence in the nucleotide-binding pocket and Irgm proteins containing a non-canonical GxxxxGMS sequence. Homo- and hetero-oligomerization among IRGs occurs via G-domain interactions. Membrane binding requires a conserved αK amphipathic helix in the C-domain. Additionally, Irga6 and Irgb6 possess an N-terminal myristoylation motif, and Irgm1 contains a C-terminal palmitoylation motif allowing for covalent lipid attachments that assist in membrane binding. In contrast, Irgb6 harbors a binding pocket for specific phospholipids such as PI5P. Figure created with BioRender.com

Table 1.

IRG table

Mechanisms of cell-autonomous immunity can differ substantially between mice and humans. There are several mouse and human GBPs that share significant structural and functional homology, but the IRG system is far more divergent [2,8]. While mice feature an expansive set of IRG genes, humans lack antimicrobial effector IRGs. Only one functional IRG is broadly expressed in human tissues, the human clade M paralog IRGM [4]. Human IRGM and the murine Irgm paralogs do share roles in orchestrating inflammation but execute divergent functions in cell-autonomous immunity. Specifically, murine Irgm1 and Irgm3 are essential in regulating GKS IRG localization and cell-autonomous immunity, but also play additional roles in cellular homeostasis (Table 1). While Irgm2 is less critical for GKS IRG localization [9,10], it was recently found to regulate noncanonical inflammasome activation in response to LPS or gram-negative bacterial infection [11,12]. While the phenotypes in GKS-deficient mice appear to be limited to defects in cell-autonomous immunity, Irgm-deficient animals display pleiotropic phenotypes that include altered host defense, exacerbated inflammation, and disruption of cellular homeostasis [2].

While the importance of the IRG family in murine cell-autonomous immunity has been readily demonstrated, many questions remain regarding their function and regulation. GKS IRGs specifically localize to cytosolic pathogens or the membranes of PVs rather than host membranes. A variety of features on cytosolic bacteria, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and flagella, is evident and accessible to the host for identification and differentiation from host membranes. However, the PVM of pathogens such as Chlamydia and Toxoplasma are originally derived from the host cell plasma membrane and are not known to display such obvious identifying features. How, then, are GKS IRGs able to identify and specifically target to the PVM? In this review, we integrate different mechanistic concepts for controlling the subcellular localization of IRGs, incorporating recent structural insights in IRG-lipid interactions into a unified model for IRG targeting to PVs.

The ”missing self” hypothesis

Initial models of IRG targeting to PVs derived from early observations regarding IRG subcellular localization. In IFNγ-primed cells, it was initially observed that GKS IRGs Irga6 and Irgb6 accumulate at the Toxoplasma PVM, but in uninfected IFNγ-primed cells, these proteins adopt a diffuse cytosolic staining pattern with a slight enrichment on the endoplasmic reticulum [5,13]. Ectopically expressed Irga6 in unprimed cells formed cytoplasmic aggregates, implying that other IFNγ-induced proteins are required to regulate the localization of Irga6 and other GKS proteins [13].

A possible explanation for the formation of GKS aggregates was provided by biochemical studies revealing that Irga6 and Irgb6 form GTP-dependent oligomers in vitro [14]. In the absence of IFNγ, ectopic expression of Irga6 or Irgb6 could therefore result in GKS protein oligomerization in the host cell cytosol, thereby sequestering proteins otherwise destined for delivery to Toxoplasma PVMs. However, ectopic expression of Irga6 or Irgb6 along with the three Irgm proteins abolished the cytoplasmic aggregation of GKS IRGs and restored their targeting to the Toxoplasma PV. Yeast two-hybrid assays demonstrated direct nucleotide-dependent interactions between GKS IRGs and Irgm proteins, indicating that Irgm proteins regulate GKS localization and function by acting as guanine dissociation inhibitors (GDIs) [13]. These observations led to the “missing self” hypothesis: Irgm proteins reside on host organellar membranes and inhibit the GTP-dependent oligomerization and binding of GKS IRGs. In contrast, the PVM, which is devoid of Irgm proteins, allows for disinhibited GKS oligomerization and subsequent antimicrobial function. Although GKS proteins can oligomerize in the absence of lipids [14], it is likely that oligomerization occurs with accelerated kinetics in the presence of an appropriate lipid template, as it has been shown for many other dynamin-related proteins including GBP1 [15–17]. Therefore, it is the absence of Irgm proteins that acts as a signal for oligomerization-dependent GKS localization and activation on a target membrane such as the PVM (Figure 2).

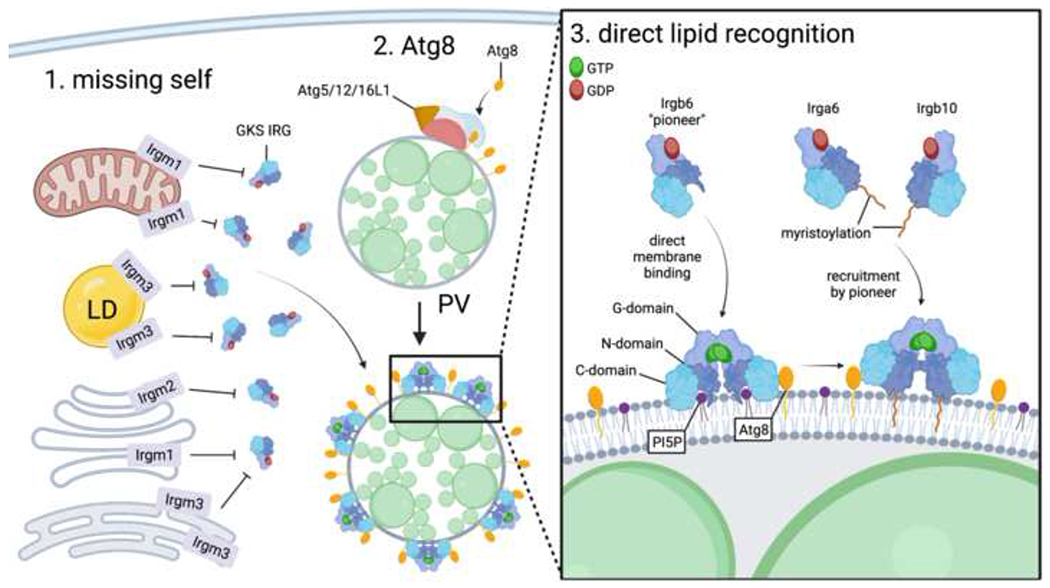

Figure 2. Three-signal model for IRG recruitment.

Irgm proteins reside on the membranes of host organelles such as mitochondria, lipid droplet (LD), endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus. As Irgm proteins inhibit GTPase activity of GKS IRGs, their absence (i.e. “missing self”) on the membranes of vacuoles containing intracellular pathogens such as C. trachomatis (green circles) renders those membranes permissive to GKS IRG recruitment. Conjugation of Atg8 proteins to phosphotidylethanolamine by Atg5/12/16L1 at the PVM comprises a second signal for GKS IRG recruitment. Finally, some IRGs such as Irgb6 specifically bind PV-enriched lipid species such as PI5P and may go on to recruit other IRGs such as Irga6 and Irgb10. Figure created with BioRender.com.

The “missing self” hypothesis was corroborated and expanded in subsequent work. Irgb10 was found to localize to inclusions (vacuoles containing the bacterial pathogen C. trachomatis) in a manner dependent on Irgm proteins. Similar to Irga6 and Irgb6, Irgb10 GTP-dependent oligomerization was required for stable recruitment to non-self target membranes. Forced tetramerization or oligomerization of an Irgb10 mutant lacking its G-domain was sufficient to target Irgb10 to C. trachomatis inclusions independent of Irgm proteins [18]. Collectively, these observations indicated that Irgm proteins regulate proper IRG localization by regulating nucleotide-dependent protein oligomerization. Further supporting this model, lipid droplets were found to be decorated with Irgm3 but largely devoid of GKS proteins in IFNγ-primed wildtype cells. In contrast to wildtype cells in which lipid droplets showed limited enrichment for GKS IRGs, lipid droplets in Irgm3-deficient cells were heavily decorated with Irga6, Irgb6, and Irgb10 [18]. These findings demonstrating vastly amplified GKS IRG localization to host organelles in the absence of inhibitory Irgms further supported the “missing self” hypothesis.

“Targeting by AutophaGy (TAG)”

The “missing self” hypothesis was eventually found to be insufficient to explain the complex process of GKS protein delivery to PVs, as components of the autophagy pathway were implicated in regulating GKS targeting. Briefly, a complex of autophagy-related proteins (E1-like Atg7, E2-like Atg3, and E3-like Atg5/12/16L1) conjugates the Atg8 family of small proteins to phosphotidylethanolamine (PE) for incorporation into autophagosomes at various stages of development. Murine Atg8 homologs include the two microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 family members LC3a and LC3b as well as three γ-butyric acid receptor-associated proteins Gabarap, GabarapL1, and GabarapL2 [19]. Adaptor proteins such as p62 bind mammalian Atg8 homologs as well as ubiquitin, targeting ubiquitinated substrates for autophagic consumption [19]. It was initially found that Atg5-deficient cells were defective for IFNγ-mediated destruction of Toxoplasma PVs and resistance to Listeria monocytogenes, and subsequent findings hinted at a potential link between IRGs and autophagy proteins [20]. GKS IRG aggregates in Irgm-deficient cells were found to colocalize with Atg8 and p62 [21], and GKS IRGs also aggregated and failed to target C. trachomatis or Toxoplasma PVs and execute cell-autonomous immunity in Atg3- or Atg5-deficient cells [22,23]. These findings demonstrated that Atg8 conjugation to PE is required for proper GKS IRG localization and PV targeting.

Subsequent studies revealed that proteins involved upstream of Atg8 lipidation in canonical autophagy were not required for cell-autonomous immunity or GKS IRG localization, implying that the Atg8 lipidation process specifically is coopted by the IRG system rather than other components of canonical autophagy (Figure 2). Indeed, Atg5 was found to transiently associate with the Toxoplasma PV early in infection, and Atg8 proteins were found to decorate the Toxoplasma PV alongside GKS IRGs [24]. Additionally, conjugation-dependent localization of Atg8 proteins on viral replication centers promoted GKS IRG recruitment independently of canonical autophagy [25]. Deletion of individual Atg8 proteins – especially Gate-16/GabarapL2 – disrupted targeting of GKS IRGs to Toxoplasma PVs and induced their cytoplasmic aggregation [26]. In a landmark study, Hwang and colleagues showed that ectopic expression of the Atg8 lipidation complex, Atg5/12/16L1, was sufficient to drive GKS IRG recruitment to certain host membranes. Atg16L1 mutants that localized specifically to mitochondria or plasma membrane were expressed in cells deficient for wildtype Atg16L1, resulting in Atg8 conjugation at those target membranes and Irga6 recruitment to those sites in IFNγ-treated cells under most conditions [27]. Given that some IRGs contain putative LC3-interacting regions, these findings situate Atg8 conjugation to PE upstream of IRG targeting to intracellular pathogens and suggest that Atg8 conjugation and incorporation into target membranes may act as a second signal for GKS IRG recruitment via direct Atg8-IRG interactions [26–28].

These findings supporting Atg8 conjugation as a second signal are consistent with the “missing self” hypothesis. Mitochondria are decorated with Irgm1 and the plasma membrane is devoid of Irgm proteins. Accordingly, in cells expressing plasma membrane targeted Atg16L1, IFNγ alone was sufficient to drive GKS IRG recruitment to Atg8-decorated plasma membrane. However, in cells expressing mitochondria-targeting Atg16L1, infection with Toxoplasma was required in addition to IFNγ to drive Irga6 localization to mitochondria [27]. These observations suggest that Toxoplasma infection somehow interferes with the inhibitory activity of Irgm proteins on mitochondria. While the absence of Irgm proteins and the presence of PE-conjugated Atg8 on target membranes comprises a first and second signal, respectively, for GKS IRG localization, the detailed mechanisms underlying how these signals result in GKS IRG recruitment remain to be fully elucidated.

Direct lipid binding to deliver IRGs to vacuolar pathogens

While most investigations aimed to identify protein signals to trigger IRG recruitment, some studies have evaluated the capabilities of IRGs to bind to specific membrane compartments. Palmitoylation of Irgm1 supports localization with Golgi and mitochondrial membranes [29], and Irgm1 has been shown to colocalize with some endosomes and phagosomes, although conflicting reports exist [30–32]. Irgm-decorated host vesicles generally do not contain luminal pathogens, however Irgm1 appears to localize to phagosomes containing the avirulent Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) and promote fusion with lysosomes [30,33]. Irgm1 recruitment to BCG-containing phagosomes was mediated via direct preferential binding of phosphatidylinositol-(3,4,5)P3 (PtdIns(3,4,5)P3) and PtdIns(3,4)P2, as well as diphosphatidylglycerol (cardiolipin). Modulation of phosphoinositide kinase (PI(3)K) activity disrupted Irgm1 localization, demonstrating that membrane lipid composition may serve as a signal for Irgm1 recruitment [30]. However, these observations did not address GKS IRG recruitment to bona fide PVs containing virulent pathogens and fell short of explaining how Irgm1 may regulate GKS IRG localization.

Some GKS IRGs display membrane-binding activity via conserved amphipathic helical domains and covalent lipid attachments (Figure 1). While Irgb10 localizes to C. trachomatis and Toxoplasma PVs [18,22,34], it also has been shown to localize to the inner membrane of cytosolic bacteria such as Francisella novocida, albeit in a GBP-dependent manner [35]. The precise binding partner for Irgb10 on bacterial membranes is unknown, but oligomerized Irgb10 requires a C-terminal amphipathic helix for recruitment to C. trachomatis inclusions [18]. This amphipathic helix comprises a putative membrane-binding domain that is found among many GKS IRGs including Irga6, suggesting a possible conserved membrane docking mechanism. In addition to these amphipathic helices, Irgb10 and Irga6 are also myristoylated at their N-terminal domains [18,36,37], and recent structural analysis of Irgb10 has generated a putative model for GTP-dependent insertion of this myristoyl moiety into target membranes [38]. Therefore, spatial control over GTPase activity and the resulting myristoyl switch could promote Irgb10 binding specifically to PVMs. However, forced tetramerization of Irgb10, which eliminates any spatial regulation of Irgb10 oligomerization, still resulted in preferential localization of Irgb10 to C. trachomatis inclusions, in a manner dependent upon the N-terminal myristoylation and the C-terminal amphipathic helix motifs [18]. These findings imply that myristoylation provides non-specific membrane anchoring properties but that amphipathic helices, commonly found in GKS IRGs, delineate target membrane specificity.

Irgb6 has been identified as a “pioneer” GKS IRG that loads onto Toxoplasma PVs prior to other IRGs such as Irga6 [22]. Irga6 and Irgb10 recruitment to Toxoplasma PVs was decreased in Irgb6-deficient cells, tempting the speculation that Irgb6 may identify PV-specific lipid species and trigger recruitment of other IRGs. Indeed, Irgb6 was found to specifically bind phosphoinositol monophosphates in vitro, especially phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate (PI5P) and phosphotidylserine (PS), lipid species that are enriched on the Toxoplasma PVM [39]. Structural analysis of Irgb6 and in silico phospholipid-binding simulations characterized a putative mechanism for direct binding between Irgb6 and PI5P which was corroborated in cell culture [40]. These findings indicate that some IRGs such as Irgb6 may have developed a binding pocket with affinities for specific lipid moieties, conferring a preference for certain membranes enriched for these lipid species, and that these IRGs may act as “pioneers” to promote recruitment of other IRGs such as Irga6 (Figure 2).

Conclusions and open questions

Since the discovery of the IRG family, the working model for the immune detection of intracellular pathogens by IRGs has progressed substantially. GDP-bound GKS IRGs were shown to exist in a cytosolic pool and oligomerize and localize to the PVM in a manner dependent on GTP binding and hydrolysis. Host membrane-bound Irgm proteins were shown to be required for proper localization of GKS IRGs, and to act as guanine dissociation inhibitors of GKS IRGs. These observations implicated the absence of Irgm proteins as a necessary but not sufficient signal for GKS IRG membrane targeting. The lipid conjugation of Atg8 proteins was shown to drive GKS IRG recruitment, suggesting a second signal, yet these two signals were also insufficient in some circumstances. Therefore, additional factors must exist that enable GKS IRGs to differentiate the PVM from host membranes.

The preference of Irgb6 for PI5P as a preferred lipid binding partner represents a viable third signal (Figure 2). Upon IFNγ stimulation, cytosolic Irgb6 may identify potential target membranes by the presence of lipidated Atg8 proteins, and in the absence of inhibitory Irgm proteins, may oligomerize, bind tightly to PI5P, and execute its antimicrobial function. It has been shown that in defense against Toxoplasma, Irgb6 acts as a “pioneer” IRG, initially localizing to PVs and subsequently promoting recruitment of other GKS IRGs such as Irga6 and Irgb10 [22,39]. While Irgb6 contains a PI5P-specific binding pocket, it is currently unknown whether amphipathic helices found in other GKS IRGs such as Irga6 and Irgb10 exert any specificity for certain lipid species. In sum, PVM-specific lipid moieties as well as conjugated Atg8 together drive recruitment of GKS IRGs, which, in the absence of Irgm proteins, undergo GTP-dependent oligomerization and subsequent antimicrobial function.

Deficiencies in one or more IRGs are associated with susceptibilities to an extremely broad range of intracellular bacterial pathogens (Table 1), and based on their mechanisms of cell entry, nutrient acquisition, and host cell modulation, the PVMs of different pathogens are surely composed of different lipid species, although these differences have not been robustly explored. Different “pioneer” IRGs may therefore identify the PVMs of different pathogens based on their membrane compositions, subsequently recruiting other GKS IRGs that lack membrane specificity thereby initiating a specialized antimicrobial defense pathway.

Other interferon-inducible GTPases may also assist in identifying and exposing target membranes for IRG recruitment. Recent work has demonstrated that GBPs may directly bind LPS on cytosolic bacterial membranes and recruit other host effectors such as caspase-4 or ApoL3 [15,41–44]. Additionally, Irgb10 has been shown to be recruited to cytosolic bacterial pathogens in a GBP-dependent manner [35]. Work from our lab has shown that GBPs are able to localize to the LPS-coated outer membrane of cytosolic bacterial pathogens and act as detergent-like membrane permeabillizer to render bacteria susceptible to antimicrobials [15]. The surfactant activity of GBPs may thus explain their role in facilitating the delivery of Irgb10 to the inner bacterial membrane of cytosolic bacteria, where Irgb10 promotes bacterial killing and the liberation of bacterial ligands for sensing by the host [35]. Whether Irgb10 interacts directly with specific microbial ligands is currently unknown, but this mechanism highlights the possibility that, while some GKS proteins may function to disrupt the PVM, others may execute downstream antimicrobial functions at the level of the microbial membrane itself.

Mechanisms of cell-autonomous immunity in mice and humans share some similarities but are significantly divergent. Although there are several GBPs that share functional homology between mouse and human systems, IRGM is the sole human IRG that is broadly expressed. Throughout human evolution, the IRGM gene family contracted to a single locus which was pseudogenized. However, the insertion of a transposon restored the open reading frame of human IRGM, which expresses a protein that is not IFN-inducible and is truncated compared to murine Irgms but that otherwise retains some structural homology [45,46]. Without GKS IRGs to regulate, human IRGM was initially considered to be a cryptic pseudogene until genetic association studies linked IRGM variants with Crohn’s disease, sepsis, resistance to mycobacterial disease, and other effects on immunity and inflammation [47–51]. Mechanistic studies investigating human IRGM function revealed that it plays a role in autophagic flux and autophagosome-lysosome fusion [33,52], paralleling roles of murine Irgm paralogs [53]. Humans may have evolved different mechanisms of cell-autonomous immunity to compensate for their lost IRGs: for example, in infection with C. trachomatis or Toxoplasma, IFNγ stimulation of human cells induces indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which depletes the cell of tryptophan and deprives the auxotrophic microbes of a necessary metabolite [54,55]. Additional mechanisms of human cell-autonomous immunity to C. trachomatis or Toxoplasma are not well understood but appear to rely more heavily on xenophagy-related mechanisms compared to membrano-lytic defenses employed by the mouse systems [56,57]. However, both mouse and human cells rely on ubiquitination of pathogens and PVs, as well as noncanonical components of the autophagy pathway to resist intracellular pathogens [24,58–61].

One interesting observation was that, in IFNγ-primed cells, forced localization of the Atg8 lipidation machinery on the plasma membrane was sufficient to drive GKS IRG localization, while Atg8-loaded mitochondria required infection with Toxoplasma to display GKS IRG recruitment [27]. Because Irgm proteins are present on the mitochondria and not the plasma membrane, one possible interpretation of this finding is that Toxoplasma infection interferes with the inhibitory effects of mitochondrial Irgm proteins on GKS IRG recruitment. Irgm1 and human IRGM promote the fusion of early phagosomes and other vesicles with lysosomes [30,33,52], and it is possible that vacuolar pathogens such as Toxoplasma evolved effector mechanisms that block Irgm1/IRGM function to avoid direct delivery of PVs to degradative lysosomes. However, blocking Irgm recruitment to PVs would therefore render those PVs accessible to GKS IRGs, which may themselves represent a co-adaptation by the host to identify and destroy Irgm-deficient vesicles. Further study would be required to test this mechanism, but similar “guard models” of host resistance provide precedents, especially in plant immunity [62].

Many questions remain regarding mechanisms of IRG membrane targeting. While humans lack GKS IRGs, Atg8 lipidation appears to play important roles in both humans and mice, and human IRGM also promotes autophagy and lysosomal fusion. It therefore prompts the question as to whether humans also use the absence of IRGM as a marker for PVs, and if so, which host factors mediate this recognition. Other questions include whether lipidated Atg8 proteins also mark PVs for an antimicrobial attack in human cells, how the Atg8 lipidation machinery is delivered to PVs, whether the lipid composition of PVs is relevant for this type of immune recognition, and whether this process differs in mouse and human cells. Recent advances have highlighted IRG recruitment to PVs as a model system to understand fundamental principles of detection of vacuolar pathogens by the mammalian immune system. Future studies should aim to further identify the factors that differentiate host from foreign membranes and break down the differences between mouse and human systems of cell-autonomous immunity.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI148243 (to JC). JC holds an Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Borden EC, Sen GC, Uze G, Silverman RH, Ransohoff RM, Foster GR, Stark GR: Interferons at age 50: past, current and future impact on biomedicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2007, 6:975–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pilla-Moffett D, Barber MF, Taylor GA, Coers J: Interferon-Inducible GTPases in Host Resistance, Inflammation and Disease. J Mol Biol 2016, 428:3495–3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang S, Meng Q, Maminska A, MacMicking JD: Cell-autonomous immunity by IFN-induced GBPs in animals and plants. Curr Opin Immunol 2019, 60:71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bekpen C, Hunn JP, Rohde C, Parvanova I, Guethlein L, Dunn DM, Glowalla E, Leptin M, Howard JC: The interferon-inducible p47 (IRG) GTPases in vertebrates: loss of the cell autonomous resistance mechanism in the human lineage. Genome Biol 2005, 6:R92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.**.Martens S, Parvanova I, Zerrahn J, Griffiths G, Schell G, Reichmann G, Howard JC: Disruption of Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuoles by the mouse p47-resistance GTPases. Plos Pathogens 2005, 1:187–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Martens et al, Ling et al., and Zhao et al. identify the membranolytic activity of GKS proteins resulting in PV lysis and host cell death. Ling et al. further demonstrate that some GKS IRGs can directly target the plasma membrane of the parasite resulting in parasite killing.

- 6.**.Ling YM, Shaw MH, Ayala C, Coppens I, Taylor GA, Ferguson DJ, Yap GS: Vacuolar and plasma membrane stripping and autophagic elimination of Toxoplasma gondii in primed effector macrophages. J Exp Med 2006, 203:2063–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; See comments for Martens et al.

- 7.*.Zhao YO, Khaminets A, Hunn JP, Howard JC: Disruption of the Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuole by IFNgamma-inducible immunity-related GTPases (IRG proteins) triggers necrotic cell death. PLoS Pathog 2009, 5:e1000288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; See comments for Martens et al.

- 8.Muller UB, Howard JC: The impact of Toxoplasma gondii on the mammalian genome. Curr Opin Microbiol 2016, 32:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.*.Dockterman J, Fee BE, Taylor GA, Coers J: Murine Irgm Paralogs Regulate Nonredundant Functions To Execute Host Defense to Toxoplasma gondii. Infect Immun 2021, 89:e0020221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrates that Irgm2 is required for host defense to Toxoplasma and implicates Irgm2-mediated GABARAP PV targeting as a critical terminal step in cell-autonomous immunity to Toxoplasma.

- 10.*.Pradipta A, Sasai M, Motani K, Ma JS, Lee Y, Kosako H, Yamamoto M: Cell-autonomous Toxoplasma killing program requires Irgm2 but not its microbe vacuolar localization. Life Sci Alliance 2021, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pradipta et al. demonstrate that Irgm2 promotes cell-autonomous immunity to Toxoplasma, but that its localization on the PV is not required for this function. This study suggests that Irgm2 indirectly mediates host defense via regulation of additional host effectors.

- 11.**.Eren E, Planes R, Bagayoko S, Bordignon PJ, Chaoui K, Hessel A, Santoni K, Pinilla M, Lagrange B, Burlet-Schiltz O, et al. Irgm2 and Gate-16 cooperatively dampen Gram-negative bacteria-induced caspase-11 response. EMBO Rep 2020, 21:e50829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Work by Eren et al. demonstrates that the autophagy protein GABARAPL2 and its interaction partner Irgm2 attenuate activation of the LPS sensor caspase-11 in response to Gram-negative bacterial infections. Similar observations were made by Finethy et al.

- 12.*.Finethy R, Dockterman J, Kutsch M, Orench-Rivera N, Wallace GD, Piro AS, Luoma S, Haldar AK, Hwang S, Martinez J, et al. Dynamin-related Irgm proteins modulate LPS-induced caspase-11 activation and septic shock. EMBO Rep 2020, 21:e50830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; See comments for Eren et al.

- 13.**.Hunn JP, Koenen-Waisman S, Papic N, Schroeder N, Pawlowski N, Lange R, Kaiser F, Zerrahn J, Martens S, Howard JC: Regulatory interactions between IRG resistance GTPases in the cellular response to Toxoplasma gondii. EMBO J 2008, 27:2495–2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hunn et al. show that IRGM proteins resident on host cell organelles transiently interact with GKS proteins and are required for delivery of effector IRGs to PVs

- 14.*.Uthaiah RC, Praefcke GJ, Howard JC, Herrmann C: IIGP1, an interferon-gamma-inducible 47-kDa GTPase of the mouse, showing cooperative enzymatic activity and GTP-dependent multimerization. J Biol Chem 2003, 278:29336–29343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrates GKS protein oligomerization in vitro.

- 15.**.Kutsch M, Sistemich L, Lesser CF, Goldberg MB, Herrmann C, Coers J: Direct binding of polymeric GBP1 to LPS disrupts bacterial cell envelope functions. EMBO J 2020, 39:e104926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kutsch et al. demonstrate that GBPs act as surfactants to disrupt the outer membrane of cytosolic bacteria. This study offers a model to account for the GBP-dependent recruitment of Irgb10 to the surface of Gram-negatve bacteria.

- 16.Sistemich L, Kutsch M, Hamisch B, Zhang P, Shydlovskyi S, Britzen-Laurent N, Sturzl M, Huber K, Herrmann C: The Molecular Mechanism of Polymer Formation of Farnesylated Human Guanylate-binding Protein 1. J Mol Biol 2020, 432:2164–2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daumke O, Praefcke GJK: Mechanisms of GTP hydrolysis and conformational transitions in the dynamin superfamily. Biopolymers 2018, 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.**.Haldar AK, Saka HA, Piro AS, Dunn JD, Henry SC, Taylor GA, Frickel EM, Valdivia RH, Coers J: IRG and GBP host resistance factors target aberrant, “non-self” vacuoles characterized by the missing of “self” IRGM proteins. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9:e1003414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This work demonstrates that IRGM proteins protect organelles and lipid droplets from mistargeting by activated GKS proteins, thus supporting the missing-self hypothesis of PV targeting.

- 19.Nieto-Torres JL, Leidal AM, Debnath J, Hansen M: Beyond Autophagy: The Expanding Roles of ATG8 Proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 2021,46:673–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Z, Fux B, Goodwin M, Dunay IR, Strong D, Miller BC, Cadwell K, Delgado MA, Ponpuak M, Green KG, et al. Autophagosome-independent essential function for the autophagy protein Atg5 in cellular immunity to intracellular pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 4:458–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Traver MK, Henry SC, Cantillana V, Oliver T, Hunn JP, Howard JC, Beer S, Pfeffer K, Coers J, Taylor GA: Immunity-related GTPase M (IRGM) proteins influence the localization of guanylate-binding protein 2 (GBP2) by modulating macroautophagy. J Biol Chem 2011, 286:30471–30480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khaminets A, Hunn JP, Konen-Waisman S, Zhao YO, Preukschat D, Coers J, Boyle JP, Ong YC, Boothroyd JC, Reichmann G, et al. Coordinated loading of IRG resistance GTPases on to the Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuole. Cell Microbiol 2010, 12:939–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haldar AK, Piro AS, Pilla DM, Yamamoto M, Coers J: The E2-like conjugation enzyme Atg3 promotes binding of IRG and Gbp proteins to Chlamydia- and Toxoplasma-containing vacuoles and host resistance. PLoS One 2014, 9:e86684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.**.Choi J, Park S, Biering SB, Selleck E, Liu CY, Zhang X, Fujita N, Saitoh T, Akira S, Yoshimori T, et al. The parasitophorous vacuole membrane of Toxoplasma gondii is targeted for disruption by ubiquitin-like conjugation systems of autophagy. Immunity 2014, 40:924–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrates that a non-canonical autophagy pathway is required for the delivery of effector GKS proteins to Toxoplasma PVs and that Atg5 transiently associates with PVMs.

- 25.*.Biering SB, Choi J, Halstrom RA, Brown HM, Beatty WL, Lee S, McCune BT, Dominici E, Williams LE, Orchard RC, et al. Viral Replication Complexes Are Targeted by LC3-Guided Interferon-Inducible GTPases. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22:74–85 e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Biering et al demonstrates a role for IRGs in antiviral immunity.

- 26.*.Sasai M, Sakaguchi N, Ma JS, Nakamura S, Kawabata T, Bando H, Lee Y, Saitoh T, Akira S, Iwasaki A, et al. Essential role for GABARAP autophagy proteins in interferon-inducible GTPase-mediated host defense. Nat Immunol 2017, 18:899–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study shows that GABARAPs are critical for GKS protein delivery o PVs.

- 27.**.Park S, Choi J, Biering SB, Dominici E, Williams LE, Hwang S: Targeting by AutophaGy proteins (TAG): Targeting of IFNG-inducible GTPases to membranes by the LC3 conjugation system of autophagy. Autophagy 2016, 12:1153–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrates that forced delivery of the ATG12–ATG5-ATG16L1 complex to membranes can be sufficient to label membranes as GKS targets.

- 28.Coers J, Brown HM, Hwang S, Taylor GA: Partners in anti-crime: how interferon-inducible GTPases and autophagy proteins team up in cell-intrinsic host defense. Curr Opin Immunol 2018, 54:93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henry SC, Schmidt EA, Fessler MB, Taylor GA: Palmitoylation of the immunity related GTPase, Irgm1: impact on membrane localization and ability to promote mitochondrial fission. PLoS One 2014, 9:e95021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.*.Tiwari S, Choi HP, Matsuzawa T, Pypaert M, MacMicking JD: Targeting of the GTPase Irgm1 to the phagosomal membrane via PtdIns(3,4)P(2) and PtdIns(3,4,5)P(3) promotes immunity to mycobacteria. Nat Immunol 2009, 10:907–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study identifies a role for Irgm1 in promoting the fusion of Mycobacteria-containing phagosomes with lysosomes. However, some of these findings were disputed - see Springer et al.

- 31.*.Springer HM, Schramm M, Taylor GA, Howard JC: Irgm1 (LRG-47), a regulator of cell-autonomous immunity, does not localize to mycobacterial or listerial phagosomes in IFN-gamma-induced mouse cells. J Immunol 2013, 191:1765–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; See comments for Tiwari et al.

- 32.Zhao YO, Konen-Waisman S, Taylor GA, Martens S, Howard JC: Localisation and mislocalisation of the interferon-inducible immunity-related GTPase, Irgm1 (LRG-47) in mouse cells. PLoS One 2010, 5:e8648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.**.Singh SB, Davis AS, Taylor GA, Deretic V: Human IRGM induces autophagy to eliminate intracellular mycobacteria. Science 2006, 313:1438–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study identifes a role for human IRGM in antibacterial cell-autonomous immunity.

- 34.Coers J, Bernstein-Hanley I, Grotsky D, Parvanova I, Howard JC, Taylor GA, Dietrich WF, Starnbach MN: Chlamydia muridarum evades growth restriction by the IFN-gamma-inducible host resistance factor Irgb10. J Immunol 2008, 180:6237–6245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.*.Man SM, Karki R, Sasai M, Place DE, Kesavardhana S, Temirov J, Frase S, Zhu Q, Malireddi RKS, Kuriakose T, et al. IRGB10 Liberates Bacterial Ligands for Sensing by the AIM2 and Caspase-11-NLRP3 Inflammasomes. Cell 2016, 167:382–396 e317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This work demonstrates that Irgb10 directly targets Gram-negative bacteria in the host cell cytosol and promotes the lytic release of bacterial molecules activating immune sensors.

- 36.Pawlowski N, Khaminets A, Hunn JP, Papic N, Schmidt A, Uthaiah RC, Lange R, Vopper G, Martens S, Wolf E, et al. The activation mechanism of Irga6, an interferon-inducible GTPase contributing to mouse resistance against Toxoplasma gondii. BMC Biol 2011, 9:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papic N, Hunn JP, Pawlowski N, Zerrahn J, Howard JC: Inactive and active states of the interferon-inducible resistance GTPase, Irga6, in vivo. J Biol Chem 2008, 283:32143–32151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.*.Ha HJ, Chun HL, Lee SY, Jeong JH, Kim YG, Park HH: Molecular basis of IRGB10 oligomerization and membrane association for pathogen membrane disruption. Commun Biol 2021, 4:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ha et al. generate in silico structural models of Irgb10 oligomerization and membrane interactions, proffering putative mechanisms for protein oligomerization, myristoylation-dependent membrane association, and Irgb10-mediated disruption of target membranes.

- 39.**.Lee Y, Yamada H, Pradipta A, Ma JS, Okamoto M, Nagaoka H, Takashima E, Standley DM, Sasai M, Takei K, et al. Initial phospholipid-dependent Irgb6 targeting to Toxoplasma gondii vacuoles mediates host defense. Life Sci Alliance 2020, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrates that Irgb6 binds to phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate (PIP5), two lipid species enriched on Toxoplasma PVs.

- 40.*.Saijo-Hamano Y, Sherif AA, Pradipta A, Sasai M, Sakai N, Sakihama Y, Yamamoto M, Standley DM, Nitta R: Structural basis of membrane recognition of Toxoplasma gondii vacuole by Irgb6. Life Sci Alliance 2022, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Saijo-Hamano et al. perform biochemical structural analysis of interactions of Irgb6 with a variety of membrane species. These findings characterize a mechanism for specific affinity of a binding pocket withing Irgb6 to PI5P, confirming binding specificity to PV-enriched lipid species.

- 41.Gaudet RG, Zhu S, Halder A, Kim BH, Bradfield CJ, Huang S, Xu D, Maminska A, Nguyen TN, Lazarou M, et al. A human apolipoprotein L with detergent-like activity kills intracellular pathogens. Science 2021, 373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wandel MP, Kim BH, Park ES, Boyle KB, Nayak K, Lagrange B, Herod A, Henry T, Zilbauer M, Rohde J, et al. Guanylate-binding proteins convert cytosolic bacteria into caspase-4 signaling platforms. Nat Immunol 2020, 21:880–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santos JC, Boucher D, Schneider LK, Demarco B, Dilucca M, Shkarina K, Heilig R, Chen KW, Lim RYH, Broz P: Human GBP1 binds LPS to initiate assembly of a caspase-4 activating platform on cytosolic bacteria. Nat Commun 2020, 11:3276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisch D, Bando H, Clough B, Hornung V, Yamamoto M, Shenoy AR, Frickel EM: Human GBP1 is a microbe-specific gatekeeper of macrophage apoptosis and pyroptosis. EMBO J 2019, 38:e100926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.**.Bekpen C, Marques-Bonet T, Alkan C, Antonacci F, Leogrande MB, Ventura M, Kidd JM, Siswara P, Howard JC, Eichler EE: Death and resurrection of the human IRGM gene. PLoS Genet 2009, 5:e1000403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bekpen et al provides evidence that IRGM was pseudogenized and subsequently reestablished as a functional gene throughout human evolution.

- 46.Bekpen C, Xavier RJ, Eichler EE: Human IRGM gene “to be or not to be”. Semin Immunopathol 2010, 32:437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.**.McCarroll SA, Huett A, Kuballa P, Chilewski SD, Landry A, Goyette P, Zody MC, Hall JL, Brant SR, Cho JH, et al. Deletion polymorphism upstream of IRGM associated with altered IRGM expression and Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet 2008, 40:1107–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This work establishes IRGM polymorphisms correlated with altered IRGM expression as a risk factor for Crohn’s disease.

- 48.**.Intemann CD, Thye T, Niemann S, Browne EN, Amanua Chinbuah M, Enimil A, Gyapong J, Osei I, Owusu-Dabo E, Helm S, et al. Autophagy gene variant IRGM -261T contributes to protection from tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis but not by M. africanum strains. PLoS Pathog 2009, 5:e1000577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This work links genetic variability in human IRGM with susceptibility to tubercolsis.

- 49.Kimura T, Watanabe E, Sakamoto T, Takasu O, Ikeda T, Ikeda K, Kotani J, Kitamura N, Sadahiro T, Tateishi Y, et al. Autophagy-related IRGM polymorphism is associated with mortality of patients with severe sepsis. PLoS One 2014, 9:e91522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xia Q, Wang M, Yang X, Li X, Zhang X, Xu S, Shuai Z, Xu J, Fan D, Ding C, et al. Autophagy-related IRGM genes confer susceptibility to ankylosing spondylitis in a Chinese female population: a case-control study. Genes Immun 2017, 18:42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yao QM, Zhu YF, Wang W, Song ZY, Shao XQ, Li L, Song RH, An XF, Qin Q, Li Q, et al. Polymorphisms in Autophagy-Related Gene IRGM Are Associated with Susceptibility to Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018:7959707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.*.Kumar S, Jain A, Farzam F, Jia J, Gu Y, Choi SW, Mudd MH, Claude-Taupin A, Wester MJ, Lidke KA, et al. Mechanism of Stx17 recruitment to autophagosomes via IRGM and mammalian Atg8 proteins. J Cell Biol 2018, 217:997–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This work provides the framework for a molecular mechanism by which IRGM promotes autophagic flux.

- 53.MacMicking JD, Taylor GA, McKinney JD: Immune control of tuberculosis by IFN-gamma-inducible LRG-47. Science 2003, 302:654–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thomas SM, Garrity LF, Brandt CR, Schobert CS, Feng GS, Taylor MW, Carlin JM, Byrne GI: IFN-gamma-mediated antimicrobial response. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-deficient mutant host cells no longer inhibit intracellular Chlamydia spp. or Toxoplasma growth. J Immunol 1993, 150:5529–5534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pfefferkorn ER, Eckel M, Rebhun S: Interferon-gamma suppresses the growth of Toxoplasma gondii in human fibroblasts through starvation for tryptophan. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1986, 20:215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frickel EM, Hunter CA: Lessons from Toxoplasma: Host responses that mediate parasite control and the microbial effectors that subvert them. J Exp Med 2021, 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finethy R, Coers J: Sensing the enemy, containing the threat: cell-autonomous immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2016, 40:875–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haldar AK, Piro AS, Finethy R, Espenschied ST, Brown HE, Giebel AM, Frickel EM, Nelson DE, Coers J: Chlamydia trachomatis Is Resistant to Inclusion Ubiquitination and Associated Host Defense in Gamma Interferon-Primed Human Epithelial Cells. mBio 2016, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.*.Haldar AK, Foltz C, Finethy R, Piro AS, Feeley EM, Pilla-Moffett DM, Komatsu M, Frickel EM, Coers J: Ubiquitin systems mark pathogen-containing vacuoles as targets for host defense by guanylate binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112:E5628–5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrates that IRG proteins control PV ubiquitylation.

- 60.Clough B, Wright JD, Pereira PM, Hirst EM, Johnston AC, Henriques R, Frickel EM: K63-Linked Ubiquitination Targets Toxoplasma gondii for Endo-lysosomal Destruction in IFNgamma-Stimulated Human Cells. PLoS Pathog 2016, 12:e1006027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Selleck EM, Orchard RC, Lassen KG, Beatty WL, Xavier RJ, Levine B, Virgin HW, Sibley LD: A Noncanonical Autophagy Pathway Restricts Toxoplasma gondii Growth in a Strain-Specific Manner in IFN-gamma-Activated Human Cells. mBio 2015, 6:e01157–01115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones JD, Dangl JL: The plant immune system. Nature 2006, 444:323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Collazo CM, Yap GS, Sempowski GD, Lusby KC, Tessarollo L, Vande Woude GF, Sher A, Taylor GA: Inactivation of LRG-47 and IRG-47 reveals a family of interferon gamma-inducible genes with essential, pathogen-specific roles in resistance to infection. J Exp Med 2001, 194:181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mahmoud ME, Ui F, Salman D, Nishimura M, Nishikawa Y: Mechanisms of interferon-beta-induced inhibition of Toxoplasma gondii growth in murine macrophages and embryonic fibroblasts: role of immunity-related GTPase M1. Cell Microbiol 2015, 17:1069–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Feng CG, Collazo-Custodio CM, Eckhaus M, Hieny S, Belkaid Y, Elkins K, Jankovic D, Taylor GA, Sher A: Mice deficient in LRG-47 display increased susceptibility to mycobacterial infection associated with the induction of lymphopenia. J Immunol 2004, 172:1163–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Santiago HC, Feng CG, Bafica A, Roffe E, Arantes RM, Cheever A, Taylor G, Vieira LQ, Aliberti J, Gazzinelli RT, et al. Mice deficient in LRG-47 display enhanced susceptibility to Trypanosoma cruzi infection associated with defective hemopoiesis and intracellular control of parasite growth. J Immunol 2005, 175:8165–8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feng CG, Zheng L, Jankovic D, Bafica A, Cannons JL, Watford WT, Chaussabel D, Hieny S, Caspar P, Schwartzberg PL, et al. The immunity-related GTPase Irgm1 promotes the expansion of activated CD4+ T cell populations by preventing interferon-gamma-induced cell death. Nat Immunol 2008, 9:1279–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu H, Wu ZY, Fang F, Guo L, Chen D, Chen JX, Stern D, Taylor GA, Jiang H, Yan SS: Genetic deficiency of Irgm1 (LRG-47) suppresses induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by promoting apoptosis of activated CD4+ T cells. FASEB J 2010, 24:1583–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.King KY, Lew JD, Ha NP, Lin JS, Ma X, Graviss EA, Goodell MA: Polymorphic allele of human IRGM1 is associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis in African Americans. PLoS One 2011, 6:e16317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Coers J, Gondek DC, Olive AJ, Rohlfing A, Taylor GA, Starnbach MN: Compensatory T cell responses in IRG-deficient mice prevent sustained Chlamydia trachomatis infections. PLoS Pathog 2011, 7:e1001346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Taylor GA, Huang HI, Fee BE, Youssef N, Jewell ML, Cantillana V, Schoenborn AA, Rogala AR, Buckley AF, Feng CG, et al. Irgm1-deficiency leads to myeloid dysfunction in colon lamina propria and susceptibility to the intestinal pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16:e1008553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alwarawrah Y, Danzaki K, Nichols AG, Fee BE, Bock C, Kucera G, Hale LP, Taylor GA, MacIver NJ: Irgm1 regulates metabolism and function in T cell subsets. Sci Rep 2022, 12:850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gutierrez MG, Master SS, Singh SB, Taylor GA, Colombo MI, Deretic V: Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell 2004, 119:753–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Feng CG, Zheng L, Lenardo MJ, Sher A: Interferon-inducible immunity-related GTPase Irgm1 regulates IFN gamma-dependent host defense, lymphocyte survival and autophagy. Autophagy 2009, 5:232–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.He S, Wang C, Dong H, Xia F, Zhou H, Jiang X, Pei C, Ren H, Li H, Li R, et al. Immune-related GTPase M (IRGM1) regulates neuronal autophagy in a mouse model of stroke. Autophagy 2012, 8:1621–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dong H, Tian L, Li R, Pei C, Fu Y, Dong X, Xia F, Wang C, Li W, Guo X, et al. IFNg-induced Irgm1 promotes tumorigenesis of melanoma via dual regulation of apoptosis and Bif-1-dependent autophagy. Oncogene 2015, 34:5363–5371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou RX, Li YY, Qu Y, Huang Q, Sun XM, Mu DZ, Li XH: Regulation of hippocampal neuronal apoptosis and autophagy in mice with sepsis-associated encephalopathy by immunity-related GTPase M1. CNS Neurosci Ther 2020, 26:177–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tian B, Yuan Y, Yang Y, Luo Z, Sui B, Zhou M, Fu ZF, Zhao L: Interferon-Inducible GTPase 1 Impedes the Dimerization of Rabies Virus Phosphoprotein and Restricts Viral Replication. J Virol 2020, 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Henry SC, Daniell X, Indaram M, Whitesides JF, Sempowski GD, Howell D, Oliver T, Taylor GA: Impaired macrophage function underscores susceptibility to Salmonella in mice lacking Irgm1 (LRG-47). J Immunol 2007, 179:6963–6972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Henry SC, Traver M, Daniell X, Indaram M, Oliver T, Taylor GA: Regulation of macrophage motility by Irgm1. J Leukoc Biol 2010, 87:333–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bafica A, Feng CG, Santiago HC, Aliberti J, Cheever A, Thomas KE, Taylor GA, Vogel SN, Sher A: The IFN-Inducible GTPase LRG47 (Irgm1) Negatively Regulates TLR4-Triggered Proinflammatory Cytokine Production and Prevents Endotoxemia. The Journal of Immunology 2007, 179:5514–5522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Singh SB, Ornatowski W, Vergne I, Naylor J, Delgado M, Roberts E, Ponpuak M, Master S, Pilli M, White E, et al. Human IRGM regulates autophagy and cell-autonomous immunity functions through mitochondria. Nat Cell Biol 2010, 12:1154–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Taylor GA, Feng CG, Sher A: Control of IFN-gamma-mediated host resistance to intracellular pathogens by immunity-related GTPases (p47 GTPases). Microbes Infect 2007, 9:1644–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang C, Wang C, Dong H, Wu XM, Wang C, Xia F, Li G, Jia X, He S, Jiang X, et al. Immune-related GTPase Irgm1 exacerbates experimental auto-immune encephalomyelitis by promoting the disruption of blood-brain barrier and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier. Mol Immunol 2013, 53:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu Y, He Z, Li Z, Fang S, Zhang Y, Wan C, Ma Y, Lin P, Liu C, Wang G, et al. Irgm1 is required for the inflammatory function of M1 macrophage in early experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Leukoc Biol 2017, 101:507–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xia F, Li R, Wang C, Yang S, Tian L, Dong H, Pei C, He S, Jiang P, Cheng H, et al. IRGM1 regulates oxidized LDL uptake by macrophage via actin-dependent receptor internalization during atherosclerosis. Sci Rep 2013, 3:1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schmidt EA, Fee BE, Henry SC, Nichols AG, Shinohara ML, Rathmell JC, MacIver NJ, Coers J, Ilkayeva OR, Koves TR, et al. Metabolic Alterations Contribute to Enhanced Inflammatory Cytokine Production in Irgm1-deficient Macrophages. J Biol Chem 2017, 292:4651–4662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Murray HW, Mitchell-Flack M, Taylor GA, Ma X: IFN-gamma-induced macrophage antileishmanial mechanisms in mice: A role for immunity-related GTPases, Irgm1 and Irgm3, in Leishmania donovani infection in the liver. Exp Parasitol 2015, 157:103–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu B, Gulati AS, Cantillana V, Henry SC, Schmidt EA, Daniell X, Grossniklaus E, Schoenborn AA, Sartor RB, Taylor GA: Irgm1-deficient mice exhibit Paneth cell abnormalities and increased susceptibility to acute intestinal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2013, 305:G573–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rogala AR, Schoenborn AA, Fee BE, Cantillana VA, Joyce MJ, Gharaibeh RZ, Roy S, Fodor AA, Sartor RB, Taylor GA, et al. Environmental factors regulate Paneth cell phenotype and host susceptibility to intestinal inflammation in Irgm1-deficient mice. Dis Model Mech 2018, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mehto S, Jena KK, Nath P, Chauhan S, Kolapalli SP, Das SK, Sahoo PK, Jain A, Taylor GA, Chauhan S: The Crohn’s Disease Risk Factor IRGM Limits NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Impeding Its Assembly and by Mediating Its Selective Autophagy. Mol Cell 2019, 73:429–445 e427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tian L, Li L, Xing W, Li R, Pei C, Dong X, Fu Y, Gu C, Guo X, Jia Y, et al. IRGM1 enhances B16 melanoma cell metastasis through PI3K-Rac1 mediated epithelial mesenchymal transition. Sci Rep 2015, 5:12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Maric-Biresev J, Hunn JP, Krut O, Helms JB, Martens S, Howard JC: Loss of the interferon-gamma-inducible regulatory immunity-related GTPase (IRG), Irgm1, causes activation of effector IRG proteins on lysosomes, damaging lysosomal function and predicting the dramatic susceptibility of Irgm1-deficient mice to infection. BMC Biol 2016, 14:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fang S, Xu Y, Zhang Y, Tian J, Li J, Li Z, He Z, Chai R, Liu F, Zhang T, et al. Irgm1 promotes M1 but not M2 macrophage polarization in atherosclerosis pathogenesis and development. Atherosclerosis 2016, 251:282–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fang S, Sun S, Cai H, Zou X, Wang S, Hao X, Wan X, Tian J, Li Z, He Z, et al. IRGM/Irgm1 facilitates macrophage apoptosis through ROS generation and MAPK signal transduction: Irgm1 (+/−) mice display increases atherosclerotic plaque stability. Theranostics 2021, 11:9358–9375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Azzam KM, Madenspacher JH, Cain DW, Lai L, Gowdy KM, Rai P, Janardhan K, Clayton N, Cunningham W, Jensen H, et al. Irgm1 coordinately regulates autoimmunity and host defense at select mucosal surfaces. JCI Insight 2017, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rai P, Janardhan KS, Meacham J, Madenspacher JH, Lin WC, Karmaus PWF, Martinez J, Li QZ, Yan M, Zeng J, et al. IRGM1 links mitochondrial quality control to autoimmunity. Nat Immunol 2021, 22:312–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Miyairi I, Tatireddigari VR, Mahdi OS, Rose LA, Belland RJ, Lu L, Williams RW, Byrne GI: The p47 GTPases Iigp2 and Irgb10 regulate innate immunity and inflammation to murine Chlamydia psittaci infection. J Immunol 2007, 179:1814–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Taylor GA, Collazo CM, Yap GS, Nguyen K, Gregorio TA, Taylor LS, Eagleson B, Secrest L, Southon EA, Reid SW, et al. Pathogen-specific loss of host resistance in mice lacking the IFN-gamma-inducible gene IGTP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97:751–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Halonen SK, Taylor GA, Weiss LM: Gamma interferon-induced inhibition of Toxoplasma gondii in astrocytes is mediated by IGTP. Infect Immun 2001, 69:5573–5576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Melzer T, Duffy A, Weiss LM, Halonen SK: The gamma interferon (IFN-gamma)-inducible GTP-binding protein IGTP is necessary for toxoplasma vacuolar disruption and induces parasite egression in IFN-gamma-stimulated astrocytes. Infect Immun 2008, 76:4883–4894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bougneres L, Helft J, Tiwari S, Vargas P, Chang BH, Chan L, Campisi L, Lauvau G, Hugues S, Kumar P, et al. A role for lipid bodies in the cross-presentation of phagocytosed antigens by MHC class I in dendritic cells. Immunity 2009, 31:232–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bernstein-Hanley I, Coers J, Balsara ZR, Taylor GA, Starnbach MN, Dietrich WF: The p47 GTPases Igtp and Irgb10 map to the Chlamydia trachomatis susceptibility locus Ctrq-3 and mediate cellular resistance in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103:14092–14097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu Z, Zhang HM, Yuan J, Ye X, Taylor GA, Yang D: The immunity-related GTPase Irgm3 relieves endoplasmic reticulum stress response during coxsackievirus B3 infection via a PI3K/Akt dependent pathway. Cell Microbiol 2012, 14:133–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Guo J, McQuillan JA, Yau B, Tullo GS, Long CA, Bertolino P, Roediger B, Weninger W, Taylor GA, Hunt NH, et al. IRGM3 contributes to immunopathology and is required for differentiation of antigen-specific effector CD8+ T cells in experimental cerebral malaria. Infect Immun 2015, 83:1406–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Taylor GA, Feng CG, Sher A: p47 GTPases: regulators of immunity to intracellular pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 2004, 4:100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nelson DE, Virok DP, Wood H, Roshick C, Johnson RM, Whitmire WM, Crane DD, Steele-Mortimer O, Kari L, McClarty G, et al. Chlamydial IFN-gamma immune evasion is linked to host infection tropism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102:10658–10663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Al-Zeer MA, Al-Younes HM, Braun PR, Zerrahn J, Meyer TF: IFN-gamma-inducible Irga6 mediates host resistance against Chlamydia trachomatis via autophagy. PLoS One 2009, 4:e4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Martens S, Parvanova I, Zerrahn J, Griffiths G, Schell G, Reichmann G, Howard JC: Disruption of Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuoles by the mouse p47-resistance GTPases. PLoS Pathog 2005, 1:e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liesenfeld O, Parvanova I, Zerrahn J, Han SJ, Heinrich F, Munoz M, Kaiser F, Aebischer T, Buch T, Waisman A, et al. The IFN-gamma-inducible GTPase, Irga6, protects mice against Toxoplasma gondii but not against Plasmodium berghei and some other intracellular pathogens. PLoS One 2011, 6:e20568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Carlow DA, Teh SJ, Teh HS: Specific antiviral activity demonstrated by TGTP, a member of a new family of interferon-induced GTPases. J Immunol 1998, 161:2348–2355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Christgen S, Place DE, Zheng M, Briard B, Yamamoto M, Kanneganti TD: The IFN-inducible GTPase IRGB10 regulates viral replication and inflammasome activation during influenza A virus infection in mice. Eur J Immunol 2022, 52:285–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]