ABSTRACT

Candida species are the most prevalent cause of invasive fungal infections, of which Candida albicans is the most common. Translocation across the epithelial barrier into the bloodstream by intestinal-colonizing C. albicans cells serves as the main source for systemic infections. Understanding the fungal mechanisms behind this process will give valuable insights on how to prevent such infections and keep C. albicans in the commensal state in patients with predisposing conditions. This review will focus on recent developments in characterizing fungal translocation mechanisms, compare what we know about enteric bacterial pathogens with C. albicans, and discuss the different proposed hypotheses for how C. albicans enters and disseminates through the bloodstream immediately following translocation.

KEYWORDS: Candida albicans, intestinal translocation, dissemination, fungi, gut colonization

1. Introduction

Species within the Candida genus are the most prevalent cause of invasive fungal infections. Such Candida infections that reach the bloodstream, termed candidemia, can occur in patients with a variety of predisposing medical conditions, from gastrointestinal surgery to immunosuppression.1,2 Once in the bloodstream, Candida spp. can disseminate and colonize other organs, such as the spleen and kidneys.1,2 The opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans accounts for most candidemia cases.2,3 C. albicans is known to reside as a commensal in the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract and several studies propose that the GI tract population serves as a source for systemic infections.4 For example, it was shown that intestinal colonizing strains were identical with strains isolated from the bloodstream prior to systemic infection.5,6 A review of data from studies available at the time concluded that an endogenous source of infection from the gut, as opposed to an external source, was the most likely and well supported.7 It was recently observed that systemic infection of various Candida spp. was preceded by expansion of a single Candida species in the GI tract of hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. The intestinal isolates were identical to those later isolated from the bloodstream.8 The expansion of C. parapsilosis in the GI tract was also associated with a decrease in the total number of bacteria, while domination by C. albicans was associated with decreased bacterial diversity.8,9 These data all suggest that the GI tract likely functions as the main source for disseminated candidiasis in humans. The process from intestinal colonization, crossing the epithelial barrier, and subsequently colonizing other organs via the bloodstream has been described using various in vivo murine models of endogenously disseminated candidiasis.10–15 While colonization of the GI tract by C. albicans and host–cell interactions during the early stages of infection have been extensively studied in vitro and discussed,16–19 the later stages of translocation across the gut epithelial barrier and dissemination via the bloodstream remain more undefined. Here, we will review what is known about commensal growth of C. albicans during intestinal colonization, how C. albicans translocates from the GI tract into the bloodstream, and how this differs from what is already known for more well-studied bacteria. We will further discuss the current open questions regarding C. albicans translocation and dissemination.

2. Intestinal colonization phenotype

A fundamental aspect of C. albicans that sets it apart from other intestinal colonizers, like bacteria, and even other fungi is its morphological plasticity (Figure 1a). C. albicans morphology is influenced by many environmental factors, such as body temperature, physiological pH and the presence of certain amino acids among others.20 The ability of C. albicans to freely transition from yeast to hyphal morphologies greatly contributes to its success as a commensal colonizer and opportunistic pathogen.21,22 There is a large body of evidence that the yeast morphology favors commensal colonization of the GI tract of antibiotic-treated and germ-free mice, though both morphologies are present.23–26 In fact, evolution of C. albicans within the murine GI tract selects for hypha-defective mutant strains.27 Passage through the GI tract can even induce a specialized yeast cell type called GUT cells via the transcription factor WOR1. These cells exhibit a shift in their metabolism toward nutrients that are prevalent in the GI tract.28

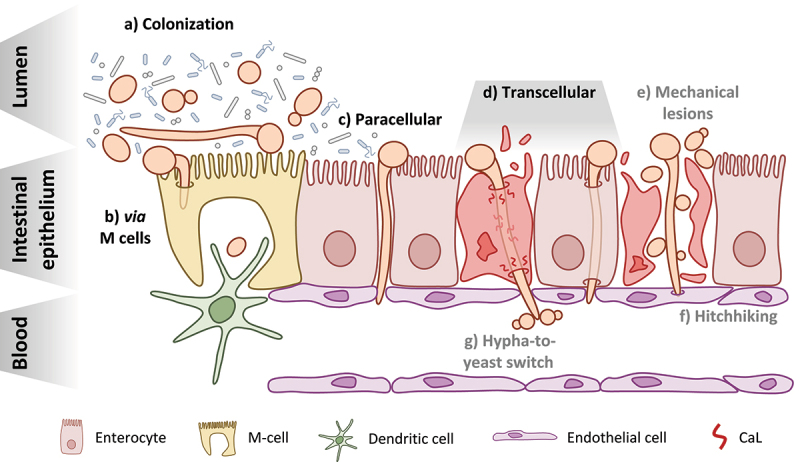

Figure 1.

Candida albicans at the intestinal barrier: from colonization to translocation and dissemination. a) C. albicans can be found in both the yeast and hyphal morphotypes during colonization of the GI tract of healthy individuals and must compete with other members of the microbiota b) Translocation via M cells present in intestinal lymphoid tissues like Peyer’s patches may occur following either induced endocytosis or active penetration by C. albicans and may also involve the fungus hijacking the sampling function of resident phagocytes, like dendritic cells c) The paracellular route of translocation refers to invasion of the intestinal barrier by C. albicans hyphae in the spaces between enterocytes without actually invading the host cells d) The transcellular route of translocation could occur in two manners: with candidalysin (CaL)-dependent damage of the epithelial cells resulting in necrotic cell death (left) or in the absence of host-cell damage (right) This appears to be the major route used by C. albicans to cross the intestinal barrier e) One hypothesis for how yeast reach the bloodstream is that they are able to move across the epithelial barrier from the GI tract to the bloodstream via physical disruptions in the tissue, caused either by the fungus itself or some other factors like surgery or chemotherapy f) The so-called “hitchhiking” hypothesis posits that yeast present in the GI tract may move through the barrier along with invading hyphae by attaching to them as they invade the epithelium g) Finally, the hypha-to-yeast switch hypothesizes that translocating hyphae undergo a morphological transition once reaching the bloodstream that initiates the formation of yeast cells from the hyphae.

Hypha formation and genes expressed during filamentation can also trigger negative selection from the host. Loss of the major hyphal regulator genes EFG1, ROB1, BRG1, or TEC1 during competition in a murine model increased colonization of C. albicans.24 Vice versa, increased filamentation of C. albicans via loss of a negative regulator for hypha formation significantly decreased colonization in an antibiotic-treated mouse model.29 Similarly, loss of the hyphal regulator genes ZCF8, ZFU2, and TRY4 led to hyper-filamentation and decreased colonization of the GI tract of germ-free mice.25 In the same study, Böhm and colleagues25 also found that overexpression of UME6 had a detrimental effect on intestinal colonization. UME6 is responsible for hyphal extension during growth in filamentation-inducing conditions.30 While overexpression of UME6 reduced competitive fitness in the GI tract of antibiotic-treated mice, loss of the gene conferred a competitive advantage and allowed a deletion mutant strain to outcompete the WT during intestinal colonization.24,25 Interestingly, the in vivo ratio of yeast to hyphae in the gut of a Ume6-deficient strain was similar to that of the wild-type strain.30 This increased competitive fitness was instead due to a loss of the secreted protease Sap6 and the surface adhesin Hyr1, suggesting that hypha-associated factors rather than the hyphal morphology per se are detrimental for colonization in antibiotic-treated mice.24

Within a healthy host, C. albicans must cope with competition with other microorganisms and a variety of host factors, with a potential impact on fungal morphology (Figure 1a). The host seems able to actively select for the yeast morphology during colonization via the adaptive immune system. Intestinal IgA specifically targets hypha-specific adhesins to select against hyphae and may actually increase the competitive fitness of C. albicans yeast cells during intestinal colonization.31,32 Additionally, C. albicans colonization of the murine GI tract induces the production of anti-fungal IgG that protects against systemic infection.33 This IgG pool also prevents fungal translocation from the GI tract, thereby helping to keep C. albicans in a commensal state.33 Intestinal colonization with C. albicans also induces anti-fungal Th-17 cells that protect against systemic infection and are even cross-reactive against other fungal pathogens; however, it has not yet been shown whether such Th-17 responses directly influence C. albicans morphology or translocation from the GI tract into the bloodstream.34,35 The role that these adaptive immune responses play in colonization and infection of C. albicans has been recently reviewed.36,37

Recent studies suggest that the microbiome composition and level of bacterial colonization are key factors that determine the degree of C. albicans colonization in mice and humans.9,26,38 In fact, most mouse models rely on removal of gut bacteria by antibiotic treatment to allow for stable intestinal colonization of C. albicans lab strains.15,39,40 Without antibiotic treatment, antagonistic effects of gut microbiota on fungal growth or morphology may limit C. albicans colonization. Some Lactobacillus species, for example, have been shown to antagonize C. albicans pathogenicity on intestinal epithelial cells as well as interfere with hyphal elongation via a variety of mechanisms, such as production of short chain fatty acids.41–44 Lactobacillus rhamnosus can even induce a hypha-to-yeast switch in C. albicans through production of various metabolites when cultured with enterocytes, thereby reducing the fungus’ ability to cause damage.42 A similar inhibition of hypha formation has been observed in the presence of Enterococcus faecalis.43 The extent to which such antagonistic effects affect fungal colonization in vivo, is not fully understood. In fact, colonization by C. albicans is also possible without antibiotics, though to a lesser degree.45 In addition, there is conflicting evidence whether or not laboratory mice are naturally resistant to colonization with C. albicans.46,47 Recent studies showed increased fungal colonization when using rewilded mice or human C. albicans isolates instead of standard laboratory strains.26,38 Diet alterations have also been shown to facilitate stable C. albicans gut colonization in mice even without antibiotic treatment, possibly due to changes in the bacterial microbiome.48

While there are many factors which seem to promote yeast growth in the GI tract during colonization, this does not appear to be sufficient to completely suppress hyphal growth (Figure 1a). Though they showed a competitive advantage for strains lacking major hyphal regulators, Witchley and colleagues24 observed yeast and hyphae present in all gut compartments of antibiotic-treated mice, matching results from other studies.25,26 They also found increased expression of hypha-associated genes in the gut compared to the yeast inoculum, such as ECE1, ALS3 and HWP1, similarly to a previous study.24,49 The transition from yeast to hyphal growth has long been considered one of the most important virulence factors for C. albicans. This process of filamentation plays a vital role during C. albicans infection and has been discussed as a promising target for antifungal drugs.21,22 In fact, the previously mentioned hypha-associated genes (ECE1, ALS3, and HWP1) are some of the most well-characterized virulence factors for C. albicans and also part of the core filamentation response that comprises commonly upregulated genes under a variety of filament-inducing conditions.50,51 Whether hyphae play a distinct role during colonization or filamentation simply cannot be fully suppressed by the host and microbiota remains to be determined. However, since the majority of C. albicans isolates have kept the potential to form hyphae and the commensal stage is the predominant lifestyle of C. albicans, there must be a selective advantage of hypha formation during colonization.

Furthermore, the presence of hyphae in the GI tract prior to infection may provide some benefit to C. albicans as it transitions from commensal to pathogen. In the following sections, we will discuss the stages of infection immediately following colonization of the gut, dissect the mechanisms involved, and how these morphotypes contribute to each step.

3. Translocation across the intestinal epithelium

As previously mentioned, many predisposing factors increase the risk of translocation of C. albicans from the GI tract to the bloodstream. Trauma, intestinal surgery, chemotherapy, and immunosuppression can all lead to candidemia.1,2 Many host factors are critical for preventing fungal translocation from the gut, including a balanced gut microbiome, intact intestinal barrier and cellular immunity, particularly neutrophils.15,45 The contribution of surgery and physical disruption of the intestinal barrier will be discussed in section 4.2, but here we will focus on C. albicans-mediated translocation and the strategies the fungus uses to overcome the intestinal epithelium. The interaction of C. albicans with the host at mucosal barriers has been recently reviewed with detailed descriptions of the different players (gut microbiota, intestinal epithelial cells, and gut mucosal immunity) as well as the fungal factors involved and models that can be used to study such processes.19 Here, we focus on the major translocation routes observed or proposed for C. albicans (transcellular, via microfold cells, and paracellular), compare the knowledge on fungal translocation to known mechanisms used by bacteria, and highlight the current knowledge gaps concerning fungal translocation.

3.1. Transcellular translocation

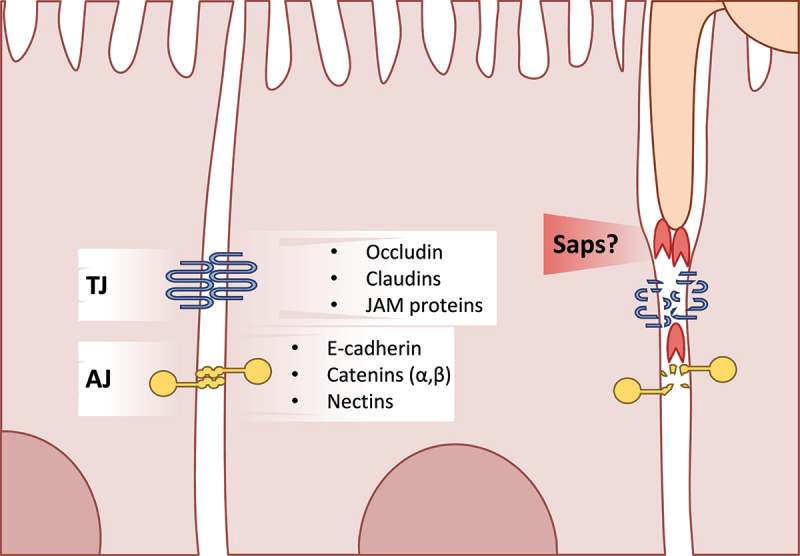

Translocation across the intestinal epithelium via non-phagocytic cells, referred to as transcytosis, is well characterized for many bacteria both in vitro and in vivo.52 Salmonella typhimurium induces actin rearrangements and endocytosis by the direct injection of the SopE, SopE2, and SopB effector proteins via its type III secretion system.53 Listeria monocytogenes specifically binds E-cadherin on the surface of enterocytes to induce internalization and subsequent exocytosis.54 This is similar to the process of induced endocytosis observed during infection of oral epithelial cells in vitro with C. albicans. During the early stages of infection, adhesion of C. albicans to oral epithelial cells triggers actin-dependent, induced endocytosis via binding of the fungal adhesin Als3 to host E-cadherin.55,56 This process can also be observed during infection of intestinal epithelial cells in vitro, though only with alteration of tight junction proteins between host cells (Figure 2). Induced endocytosis of C. albicans by enterocytes was observed after widening of the intercellular spaces with patulin treatment.57 This study also shows that intact and mature tight junctions of the intestinal epithelium inhibit induced endocytosis by C. albicans, limiting invasion to active penetration by hyphae.

Figure 2.

A glance at intestinal epithelial cell junctions. An overview of the major components of cell-cell junctions of enterocytes Tight junctions (TJ) are mainly comprised of the occludin, claudin, and junction adhesion molecule (JAM) proteins Adherens junctions (AJ) in intestinal epithelial cells are mostly comprised of E-cadherin, catenins, and nectins C. albicans is capable of degrading tight and adherens junction proteins, potentially via secretion of Sap5.

The major route for invasion of intestinal epithelial cells by C. albicans in in vitro models is active penetration.56 This suggests that the main mode of translocation through the intestinal epithelium likely involves filamentation, penetration and damage of host cells, in contrast to the more host-driven mechanisms of bacterial transcytosis. Damage of epithelial cells is driven by the ECE1 gene, which encodes the peptide toxin candidalysin (CaL).58 CaL-mediated damage was shown to be required for the efficient translocation of C. albicans across enterocytes.59 The main route appeared to be transcellular in this system as efficient translocation was associated with necrotic cell death and required the full damage potential of invading hyphae (Figure 1d). However, a recent study showed that C. albicans invasion of enterocytes occurs largely in the absence of any apparent disruption of the host membrane for up to 9 hours of infection.60 Though host-cell damage and death were observed for invasion events after 20 hours,59,60 this supports the hypothesis that transcellular translocation is possible through enterocytes in the absence of significant host damage (Figure 1d). This might also explain the low levels of translocation seen for the non-damaging C. albicans strain lacking ECE1, as it exhibits normal hypha formation and invasion of epithelial cells.58,59 Translocation was also dependent on hypha formation as filamentation-deficient strains lacking both EFG1 and CPH1 also showed a decreased rate of translocation.59 This is further supported by the observation that L. rhamnosus, which protects intestinal epithelial cells from C. albicans damage and limits filamentation, also significantly decreased fungal translocation.41

In contrast to the more host-driven process of induced endocytosis that is utilized by bacteria, C. albicans translocation through enterocytes seems to be mainly dependent on hypha formation, invasion, and host damage. While we know that both yeast and hyphae are present in the GI tract during colonization, the roles these morphologies play during intestinal translocation in vivo remain unknown. The contribution of colonization-induced host responses during fungal translocation of C. albicans is also largely unknown as most studies focus on in vitro model systems, which lack any host immune system. Further studies are required to elucidate, for example, whether yeast cells are able to translocate themselves or together with hyphae and if the colonizing hyphae are sufficient to initiate translocation or if there is an expansion of hyphae preceding translocation.

3.2. Translocation via microfold cells and Peyer’s patches

The contributions of microfold (M) cells and Peyer’s patches of the intestine to translocation of bacterial pathogens during systemic infection has been well studied and reviewed.52 M cells are specialized intestinal epithelial cells for phagocytosis of material from the lumen and its presentation to resident phagocytes, like dendritic cells (Figure 1b).61 M cells are located within lymphoid tissues of the gut, like Peyer’s patches in the small intestine.61 Bacteria such as Shigella flexneri and S. typhimurium are known to specifically target M cells during infection. S. flexneri can also enter M cells, though not exclusively, and use these as a mechanism for translocation across the epithelium.62 S. typhimurium exclusively invades M cells causing extensive host-cell death and is even able to enter adjacent epithelial cells.63 S. typhimurium has also been shown to use phagocytic cells present at Peyer’s patches for transport into the bloodstream. The presence of dendritic cells in an in vitro model with intestinal epithelial cells facilitated transport across the barrier.64 The same study also showed the uptake of S. typhimurium from the intestine in an in vivo mouse model.

In contrast to bacteria, the involvement of M cells during translocation of C. albicans across the intestinal epithelium has not been fully elucidated. It is known that C. albicans, along with C. tropicalis, are sampled by Peyer’s patches and taken into lymphoid tissues in a partially M cell-dependent manner in vivo (Figure 1b).65 C. albicans was also shown to preferentially invade M cells in a mixed, in vitro model of enterocytes and M cells via both induced endocytosis and active penetration.66 Whether this invasion translates to translocation across the epithelial barrier, however, remains to be investigated. The contribution of phagocytic cells within Peyer’s patches to the translocation of C. albicans has yet to be investigated. However, De Jesus et al.65 also observed that C. albicans is sampled from Peyer’s patches in vivo by dendritic cells (Figure 1b). C. albicans was also shown to be recognized and internalized by intestinal CX3CR1+ mononuclear phagocytes in a mouse model of intestinal colonization.67 The fate of these yeast cells has yet to be investigated. It is possible that internalized C. albicans cells are able to hijack this mechanism to facilitate their own transport across the intestine in a similar fashion to bacteria. It has been well documented that C. albicans is able to survive within phagocytes, filament, damage the host cell, and ultimately escape.68 In an in vivo zebrafish model of disseminated candidiasis, yeast cells phagocytosed by macrophages were transported away from the infection site through the blood and later escaped.69

3.3. Paracellular translocation

Though the main route for C. albicans translocation is via direct invasion and damage of epithelial cells in vitro, low levels of translocation could still be observed in a damage-independent manner when using a mutant strain lacking CaL.59 As mentioned in section 3.1, this could be the result of invasion and transcellular translocation in the absence of host damage; however, a paracellular route between epithelial cells has also been discussed (Figure 1c).19 Enterocytes likely limit fungal translocation to a degree through increased expression of tight and adherens junction proteins during these early stages (Figure 2).57 Additionally, the presence of antimicrobial peptides or the quorum sensing molecule farnesol increases the expression of tight junction proteins and consequently improves the epithelial barrier integrity.70,71 Nevertheless, the intestinal epithelial barrier shows increased permeability during infection with C. albicans even at early time points before significant levels of damage can be detected.59,60,72,73 C. albicans can degrade tight and adherens junction proteins like E-cadherin, occludin, and demoglein-2.73 In fact, C. albicans decreases levels of occludin, JAM-A, and claudins 1, 3, 4 starting 6 hours after infection of intestinal epithelial cells with E-cadherin levels dropping after 21 hours.72 A similar mechanism can be found in some pathogenic bacteria. Vibrio cholerae secretes multiple proteins and toxins that degrade and alter tight junctions.74 The secreted haemagglutinin/protease specifically degrades extracellular occludin of host cells.75 V. cholerae also produces the zonula occludens toxin (ZOT). ZOT reorganizes tight junctions of intestinal epithelial cells via interactions with occludin and ZO-1.76 Though this rearrangement of tight junctions was not associated with a decrease in the barrier integrity or permeability, in vivo experiments have shown that ZOT increases the permeability of the small intestine resulting in a leaky epithelium.77

E-cadherin degradation of oral epithelial cells by C. albicans has been linked to the secreted aspartyl protease Sap5.78 A strain lacking SAP5, however, showed no decrease in translocation in an in vitro model system of cultured enterocytes.59,78 While paracellular translocation is possible and even likely, thus far there is no study with direct evidence that C. albicans crosses the intestinal epithelium by degrading tight junctions between enterocytes. Basmaciyan and colleagues19 do, however, highlight that disruption of the intestinal barrier and tight junctions by external factors in vivo could allow for paracellular translocation via mechanisms like the induced endocytosis described in section 3.1.57 Further studies are required to elucidate the contribution of the paracellular route to C. albicans translocation, the involved fungal factors, and what impact this has under clinically relevant conditions.

4. Dissemination via the bloodstream

4.1. Disseminating phenotype

A unique aspect of C. albicans pathogenicity comes into focus when looking at dissemination as compared to bacteria. Most bacteria do not filament and they reach the bloodstream as an easily disseminated shape and size. This is not the case for C. albicans. While hyphae are the main invasive form of C. albicans during epithelial infection and translocation, yeast cells are thought of as the morphotype best suited for dissemination once the fungus has entered the bloodstream due to their smaller size and rounder shape.21 While hyphal and pseudohyphal cells are able to adhere to endothelial cells under flow and shear stress, adhesion of yeast cells was increased under such conditions.79 Indeed, yeast with short germ tubes were shown to be the optimal morphology for adhesion to endothelial cells in in vitro conditions mimicking physiological flow in the bloodstream.80

Distinct roles for both yeast and hyphae have been described in a zebrafish model of disseminated candidiasis.81 A hyper-filamentous C. albicans strain readily invaded and killed the zebrafish without disseminating through the blood, while hypo-filamentous and yeast-locked strains were able to cause disseminated disease with decreased mortality. When hyper- and hypo-filamentous strains were co-infected there was an additive effect of both morphologies, but no enhancement of virulence.81 The same study even observed dissemination of a yeast-locked strain of C. albicans. The ability of yeast to exit the bloodstream independently of hypha formation has also been observed in murine models of disseminated candidiasis.82 Saville and coworkers82 showed that strains locked in the yeast morphology are capable of translocating across the endothelium and colonizing organs of mice to a similar degree as normal filamenting C. albicans, though with decreased mortality. Recently, however, it was shown that a C. albicans strain lacking the gene EED1 that is deficient in maintaining hyphal growth is capable of dissemination with no associated drop in virulence.83

4.2. How do yeast cells reach the bloodstream?

As current studies on C. albicans translocation using in vitro models suggest, the fungus reaches the bloodstream as long hyphae following continuous invasion and translocation across the intestinal epithelium. Given that yeast cells or short hyphae seem to be better suited for exit from the bloodstream as a prerequisite of organ colonization, the question remains as to how yeast appear in the bloodstream in the first place.79–82 Here we explore three different hypotheses that have been proposed to explain the presence of yeast in the bloodstream following translocation: mechanical lesions, a “hitchhiking” mechanism, and a hypha-to-yeast transition (Figure 1e-g).

Mechanical lesions

Disruption of the intestinal barrier is a major predisposing factor for systemic infection and intestinal translocation in mice colonized with C. albicans.15 In humans, immunocompromised patients are particularly susceptible to systemic candidemia and often suffer from mucosal damage to the GI tract as a result of chemotherapy treatments.1,2,84–86 Given that both yeast and hyphae are present in the GI tract during colonization, physical disruption of the epithelial barrier could allow for the passive translocation of yeasts into the bloodstream.24–26 While this is a probable mechanism for patients with disturbed intestinal epithelia, not all individuals at high risk for developing candidemia suffer from this. Critically ill patients in intensive care units are another group that is particularly susceptible to candidemia, though they do not consistently present with mucosal damage due to chemotherapy treatment or abdominal surgery.1,84–86 These studies suggest that the development of physical lesions in the epithelium is only responsible for the presence of yeast in the bloodstream for a subset of clinical cases, but it is likely not the only mechanism.

“Hitchhiking” mechanism

Another possibility is that the yeast present in the GI tract during colonization simply move through the intestinal epithelium together with hyphae as they invade the tissue (Figure 1f). It has been suggested before that adhesins expressed during the later stages of biofilm formation, like Fav2 and Hyr1, may contribute to cell-to-cell adhesion of C. albicans.87 Loss of YWP1, a gene encoding an adhesion protein associated with the yeast morphology of C. albicans, decreased the biofilm mass only during the late stages of biofilm development.88,89 Additionally, the adhesins encoded by HWP1 and ALS3 also interact with each other and Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast cells expressing C. albicans Hwp1 were able to bind C. albicans hyphae, though only when the hyphae expressed ALS3.90 Taken together, these in vitro studies show that there is the potential for C. albicans yeast cells to attach to hyphal cells. However, this has not been showed directly thus far and more studies are required to determine whether this adhesion between morphologies is sufficient to transport yeast cells. It should be noted that a similar mechanism has been proposed for Candida glabrata yeast cells attached to C. albicans hyphae during oral infections.91

A study where immunosuppressed gnotobiotic piglets developed systemic candidiasis following oral inoculation with C. albicans showed lesions and extensive necrosis of the intestinal epithelium.92 Both yeast and hyphae were observed in the intestinal lesions, which might suggest a “hitchhiking” mechanism where yeast from the intestine move along with translocating hyphae following sufficient damage of host tissue. However, this could also be due to a transition from hyphal to yeast growth during translocation. In an in vitro model of intestinal translocation, the damage to host cells caused by invading hyphae is able to degrade the epithelial barrier enough to allow for the passage of dextran particles through.59 In a mouse model of colonization and disseminated candidiasis, hyphae and yeast were present invading the intestinal epithelium.13 While these studies did not provide direct evidence that yeast cells from the intestinal side cross the epithelium with hyphae, they do provide some support that hyphae are not the only morphotype present during intestinal translocation. These studies and others also show that invading C. albicans hyphae produce substantial host damage that allows for material to pass through the barrier, potentially leading to translocation via mechanical lesions.13,14,59 This degree of epithelial damage during translocation in vivo is likely given that there is an expansion of Candida spp. just prior to bloodstream infections along with a decrease in the total bacterial burden.8 This suggests that both mechanisms, mechanical lesions and “hitchhiking”, may contribute to the presence of yeast cells in the bloodstream given that C. albicans reaches a sufficient abundance within the GI tract (Figure 1e, f).

Hypha-to-yeast transition in human blood

The morphology of C. albicans that dominates in vivo during growth in the bloodstream is difficult to determine. There are a multitude of different environmental factors like blood cells, serum, flow, and temperature that make finding a simple answer challenging. C. albicans seems to readily form filaments during incubation with either serum or whole human blood.93–96 Incubation with human serum resulted in over 90% of yeast cells forming hyphae, while incubation with whole blood only resulted in just over 50%.94 This difference in morphology was mirrored in a less drastic increase in the expression of hypha-associated genes in whole blood compared to serum. Indeed, during incubation in whole blood C. albicans cells mostly associate with neutrophils which overwhelmingly govern the fungal transcriptional response and seem to dampen filamentation.93 Over 90% of fungal cells incubated with polymorphonuclear cells were still in the yeast form after 30 minutes. Germ tubes of C. albicans incubated in whole blood were also noticeably shorter than those incubated in blood fractions lacking neutrophils.93 This agrees with a recent study where only around 20% of counted fungal cells were hyphae following 3 hours of incubation in whole blood.96 Though there is evidence that yeast cells are crucial for dissemination through the bloodstream, whether these yeast cells form from invading hyphae originating from the gut has proven more challenging to determine. Understanding what fungal genes are involved in and the conditions that could trigger a switch back to yeast growth is necessary to answer this question.

While the transition from yeast to hypha is well understood, the transition in the opposite direction remains less well defined. This hypha-to-yeast switch, however, is a promising hypothesis and potential mechanism for how yeast reach the bloodstream during translocation (Figure 1g). The transcriptional regulator Pes1 was identified in C. albicans to be required for formation of yeast cells from hyphae.97 A deletion mutant strain showed decreased formation of lateral yeast from filaments in hypha-inducing conditions but had no effect on filamentous growth itself. PES1 controls the transition to yeast growth via an interaction with Nrg1, a repressor of filamentation in C. albicans, during dispersal from biofilms.98 These dispersed yeast cells more closely resemble hyphae within the biofilm on a transcriptional level than they do planktonically grown yeast cells. Specifically, they had increased expression of hypha-associated genes (PGA13, ACE2), adhesin genes (ALS5, ALS6), and secreted aspartyl protease genes (SAP3/6/8-9) among others compared to planktonic cells. PES1 also shows some function for dissemination during in vivo infection. In a jugular-vein catheter mouse model of infection, catheters with biofilms of PES1-depleted C. albicans showed decreased levels of dissemination and colonization of the kidneys due to impaired lateral yeast formation.98

The loss of PES1 not only decreased C. albicans dissemination during systemic infection but attenuated the virulence in a Galleria mellonella model of infection.97 The contribution of PES1 to the pathogenicity of C. albicans has also been studied in more complex in vivo infection models. Uppuluri et al.99 showed that not only the depletion, but also the overexpression of PES1 in a mouse model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis has a negative impact on the virulence of C. albicans. Both the overexpression and depletion of PES1 resulted in decreased mortality during infection. However, overexpression of PES1 led to a fungal load in organs similar to that of the control and depletion of PES1 decreased the fungal burden in the brain and kidneys.99 The beneficial effect of physiological PES1 expression during systemic infection highlights the importance of phenotypic plasticity for the pathogenicity of C. albicans as well as the likely role of a hypha-to-yeast transition during dissemination (Figure 1g).

5. Conclusions and future perspectives

It is clear that C. albicans owes much of its success as a commensal and as a pathogen to its morphological plasticity. The contributions of each morphotype to colonization and infection are still not fully understood. This is key to understanding the mechanisms behind intestinal translocation and further dissemination during systemic candidemia. While there has been significant progress in recent years to characterize C. albicans translocation in vitro, we still lack comprehensive knowledge about how this process is initiated, what it looks like in more complex models or in vivo and what happens when the fungus reaches the bloodstream. Further studies are needed to determine which routes C. albicans uses to cross the intestinal barrier, the fungal and host factors involved, and how the fungus ultimately spreads throughout the bloodstream to other organs. A better understanding of each of these is important to develop strategies that can ultimately prevent C. albicans dissemination and the development of systemic infections.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Theresa Lange for critically reading the manuscript.

Funding Statement

JLS and BH were supported by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft—DFG) within the Collaborative Research Centre (CRC)/Transregio (TRR) 124 “FungiNet” project C1 (DFG project number 210879364). LK was supported by the DFG Priority Program 2225 “Exit strategies of intracellular pathogens.” The authors declare that they have no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to disclose.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- 1.Kullberg BJ, Arendrup MC, Campion EW.. Invasive Candidiasis. N Engl J Med. Oct 8 2015;373(15):1445–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1315399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pappas PG, Lionakis MS, Arendrup MC, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Kullberg BJ. Invasive candidiasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers May. 2018;11(4):18026. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruhnke M, Groll AH, Mayser P, Ullmann AJ, Mendling W, Hof H, Denning DW. 2015. Denning DW estimated burden of fungal infections in Germany. Mycoses. Oct;58(Suppl 5):22–28. doi: 10.1111/myc.12392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nash AK, Auchtung TA, Wong MC, Smith DP, Gesell JR, Ross MC, Stewart CJ, Metcalf GA, Muzny DM, Gibbs RA, et al. The gut mycobiome of the Human Microbiome Project healthy cohort. Microbiome. Nov 25 2017;5(1):153. 10.1186/s40168-017-0373-4. PMC5702186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reagan DR, Pfaller MA, Hollis RJ, Wenzel RP. Wenzel RP Characterization of the sequence of colonization and nosocomial candidemia using DNA fingerprinting and a DNA probe. J Clin Microbiol Dec. 1990;28(12):2733–2738. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2733-2738.1990. PMC268264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miranda LN, van der Heijden IM, Costa SF, Sousa AP, Sienra RA, Gobara S, Santos CR, Lobo RD, Pessoa VP Jr. Levin AS Candida colonisation as a source for candidaemia. J Hosp Infect May. 2009;72(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nucci M. Anaissie E Revisiting the source of candidemia: skin or gut? Clin Infect Dis. Dec 15 2001;33(12):1959–1967. doi: 10.1086/323759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhai B, Ola M, Rolling T, Tosini NL, Joshowitz S, Littmann ER, Amoretti LA, Fontana E, Wright RJ, Miranda E, et al. 2020. High-resolution mycobiota analysis reveals dynamic intestinal translocation preceding invasive candidiasis. Nat Med. Jan;26(1):59–64. 10.1038/s41591-019-0709-7: PMC7005909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rolling T, Zhai B, Gjonbalaj M, Tosini N, Yasuma-Mitobe K, Fontana E, Amoretti LA, Wright RJ, Ponce DM, Perales MA, et al. 2021. Haematopoietic cell transplantation outcomes are linked to intestinal mycobiota dynamics and an expansion of Candida parapsilosis complex species. Nat Microbiol.Nov11;6(12):1505–1515. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00989-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim AS, Garni RM, Henry-Stanley MJ, Bendel CM, Erlandsen SL, Wells CL. 2003. Wells CL Hypoxia and extraintestinal dissemination of Candida albicans yeast forms. Shock. Mar;19(3):257–262. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200303000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi K, Kita E, Konishi M, Yoshimoto E, Mikasa K, Narita N, Kimura H. 2003. Translocation model of Candida albicans in DBA-2/J mice with protein calorie malnutrition mimics hematogenous candidiasis in humans. Microb Pathog. Nov;35(5):179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadosh D, Najvar LK, Bocanegra R, Olivo M, Kirkpatrick WR, Wiederhold NP, Patterson TF. 2016. Patterson TF effect of antifungal treatment in a diet-based murine model of disseminated candidiasis acquired via the gastrointestinal tract. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. Nov;60(11):6703–6708. PMC5075076. doi: 10.1128/aac.01144-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirayama T, Miyazaki T, Ito Y, Wakayama M, Shibuya K, Yamashita K, Takazono T, Saijo T, Shimamura S, Yamamoto K, et al. Virulence assessment of six major pathogenic Candida species in the mouse model of invasive candidiasis caused by fungal translocation. Sci Rep. Mar 2 2020;10(1):3814. 10.1038/s41598-020-60792-y. PMC7052222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan CH, Lo HJ, Yan JY, Hsiao YJ, Hsueh JW, Lin DW, Lin TH, Wu SH, Chen Y-C. Chen YC Candida albicans colonizes and disseminates to the gastrointestinal tract in the presence of the microbiota in a severe combined immunodeficient mouse model. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:619878. PMC7819875. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.619878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh AY, Köhler JR, Coggshall KT, Van Rooijen N, Pier GB. Mucosal damage and neutropenia are required for Candida albicans dissemination. PLoS Pathog Feb 8. 2008;4(2):e35. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040035. PMC2242836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumamoto CA, Gresnigt MS, Hube B. Hube B The gut, the bad and the harmless: candida albicans as a commensal and opportunistic pathogen in the intestine. Curr Opin Microbiol Aug. 2020;56:7–15. PMC7744392. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2020.5.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naglik JR, Gaffen SL, Hube B. Hube B Candidalysin: discovery and function in Candida albicans infections. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2019. Dec;52:100–109 . PMC6687503. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alonso-Monge R, Gresnigt MS, Román E, Hube B, Pla J, Jarosz D. 2021. Candida albicans colonization of the gastrointestinal tract: a double-edged sword. PLoS Pathog. Jul;17(7):e1009710. PMC8297749. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basmaciyan L, Bon F, Paradis T, Lapaquette P, Dalle F. Candida Albicans Interactions With The Host: crossing The Intestinal Epithelial Barrier. Tissue Barriers. 2019;7(2):1612661. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2019.1612661. PMC6619947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sudbery PE. Growth of Candida albicans hyphae. Nat Rev Microbiol Aug. 2011;9(10):737–748. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobsen ID, Wilson D, Wächtler B, Brunke S, Naglik JR, Hube B. 2012. Candida albicans dimorphism as a therapeutic target Expert. Rev Anti Infect Ther. Jan;10(1):85–93. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobsen ID, Hube B. Candida albicans morphology: still in focus Expert. Rev Anti Infect Ther Apr. 2017;15(4):327–330. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2017.1290524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vautier S, Drummond RA, Chen K, Murray GI, Kadosh D, Brown AJ, Gow NA, MacCallum DM, Kolls JK, Brown GD. C andida albicans colonization and dissemination from the murine gastrointestinal tract: the influence of morphology and Th17 immunity. Cell Microbiol Apr. 2015;17(4):445–450. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12388. PMC4409086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witchley JN, Penumetcha P, Abon NV, Woolford CA, Mitchell AP, Noble SM. Candida albicans morphogenesis programs control the balance between gut commensalism and invasive infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2019. Mar;25(3):432–443 e6. PMC6581065. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Böhm L, Torsin S, Tint SH, Eckstein MT, Ludwig T, Pérez JC. 2017. The yeast form of the fungus Candida albicans promotes persistence in the gut of gnotobiotic mice. PLoS Pathog. Oct;13(10):e1006699. PMC5673237. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonough LD, Mishra AA, Tosini N, Kakade P, Penumutchu S, Liang SH, Maufrais C, Zhai B, Taur Y, Belenky P, et al. 2021. Candida albicans Isolates 529L and CHN1 exhibit stable colonization of the murine gastrointestinal. Tract mBio Nov.2;12(6):e0287821. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02878-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tso GHW, Reales-Calderon JA, Tan ASM, Sem X, Gtt L, Tan TG, Lai GC, Srinivasan KG, Yurieva M, Liao W, et al. 2018. Experimental evolution of a fungal pathogen into a gut symbiont. Science.Nov2;362(6414):589–595. doi: 10.1126/science.aat0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pande K, Chen C, Noble SM. 2013. Passage through the mammalian gut triggers a phenotypic switch that promotes Candida albicans commensalism. Nat Genet. Sep;45(9):1088–1091. PMC3758371. doi: 10.1038/ng.2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Regan H, Scaduto CM, Hirakawa MP, Gunsalus K, Correia-Mesquita TO, Sun Y, Chen Y, Kumamoto CA, Bennett RJ, Whiteway M. 2017. Negative regulation of filamentous growth in Candida albicans by Dig1p. Mol Microbiol. Sep;105(5):810–824. PMC5724037. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banerjee M, Thompson DS, Lazzell A, Carlisle PL, Pierce C, Monteagudo C, López-Ribot JL, Kadosh D. UME6, a novel filament-specific regulator of Candida albicans hyphal extension and virulence. Mol Biol Cell Apr. 2008;19(4):1354–1365. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e07-11-1110. PMC2291399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ost KS, O’Meara TR, Stephens WZ, Chiaro T, Zhou H, Penman J, Bell R, Catanzaro JR, Song D, Singh S, et al. 2021. Adaptive immunity induces mutualism between commensal eukaryotes. Nature Aug. 596(7870):114–118. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03722-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doron I, Mesko M, Li XV, Kusakabe T, Leonardi I, Shaw DG, Fiers WD, Lin WY, Bialt-DeCelie M, Román E, et al. 2021. Mycobiota-induced IgA antibodies regulate fungal commensalism in the gut and are dysregulated in Crohn’s disease. Nat Microbiol. Dec;6(12):1493–1504. 10.1038/s41564-021-00983-z: PMC8622360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doron I, Leonardi I, Li XV, Fiers WD, Semon A, Bialt-DeCelie M, Migaud M, Gao IH, Lin WY, Kusakabe T, et al. Human gut mycobiota tune immunity via CARD9-dependent induction of anti-fungal IgG antibodies. Cell. Feb 18 2021;184(4):1017–1031.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.016. PMC7936855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bacher P, Hohnstein T, Beerbaum E, Röcker M, Blango MG, Kaufmann S, Röhmel J, Eschenhagen P, Grehn C, Seidel K, et al. Human Anti-fungal Th17 immunity and pathology rely on cross-reactivity against Candida albicans. Cell. Mar 7 2019;1766:1340–1355 e15. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shao TY, Ang WXG, Jiang TT, Huang FS, Andersen H, Kinder JM, Pham G, Burg AR, Ruff B, Gonzalez T, et al. Commensal Candida albicans positively calibrates systemic Th17 immunological responses. Cell Host Microbe. 2019. Mar 13;25(3):404–417 e6. PMC6419754. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swidergall M, LeibundGut-Landmann S. 2022. Immunosurveillance of Candida albicans commensalism by the adaptive immune system. Mucosal Immunol. May;15(5):829–836. PMC9385492. doi: 10.1038/s41385-022-00536-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shao TY, Haslam DB, Bennett RJ, Way SS. 2022. Friendly fungi: symbiosis with commensal Candida albicans Trends. Immunol. Sep;43(9):706–717. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2022.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yeung F, Chen YH, Lin JD, Leung JM, McCauley C, Devlin JC, Hansen C, Cronkite A, Stephens Z, Drake-Dunn C, et al. Altered immunity of laboratory mice in the natural environment is associated with fungal colonization. Cell Host Microbe. 2020. May 13;27(5):809–822 e6. PMC7276265. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White SJ, Rosenbach A, Lephart P, Nguyen D, Benjamin A, Tzipori S, Whiteway M, Mecsas J, Kumamoto CA. 2007. Self-regulation of Candida albicans population size during GI colonization. PLoS Pathog. Dec;3(12):e184. PMC2134954. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiesner SM, Jechorek RP, Garni RM, Bendel CM, Wells CL. 2001. Gastrointestinal colonization by Candida albicans mutant strains in antibiotic-treated mice. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. Jan;8(1):192–195. PMC96034. doi: 10.1128/cdli.8.1.192-195.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graf K, Last A, Gratz R, Allert S, Linde S, Westermann M, Gröger M, Mosig AS, Gresnigt MS, Hube B. Keeping Candida commensal: how lactobacilli antagonize pathogenicity of Candida albicans in an in vitro gut model. Dis Model Mech. Sep 12 2019; 12(9): 10.1242/dmm.039719. PMC6765188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alonso-Roman R, Last A, Mirhakkak MH, Sprague JL, Möller L, Großmann P, Graf K, Gratz R, Mogavero S, Vylkova S, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus colonisation antagonizes Candida albicans by forcing metabolic adaptations that compromise pathogenicity. Nat Commun. Jun 9 2022;13(1):3192. 10.1038/s41467-022-30661-5. PMC9184479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeise KD, Woods RJ, Huffnagle GB. Interplay between Candida albicans and Lactic Acid Bacteria in the Gastrointestinal Tract: impact on Colonization Resistance, Microbial Carriage, Opportunistic Infection, and Host Immunity . Clin Microbiol Rev. Dec 15 2021;34(4):e0032320. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00323-20. PMC8404691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Förster TM, Mogavero S, Dräger A, Graf K, Polke M, Jacobsen ID, Hube B. 2016. Enemies and brothers in arms: candida albicans and gram-positive bacteria. Cell Microbiol. Dec;18(12):1709–1715. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mishra AA, Koh AY. 2018. Adaptation of Candida albicans during gastrointestinal tract colonization. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep. Sep;5(3):165–172. PMC6294318. doi: 10.1007/s40588-018-0096-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leonardi I, Gao IH, Lin WY, Allen M, Li XV, Fiers WD, De Celie MB, Putzel GG, Yantiss RK, Johncilla M, et al. Mucosal fungi promote gut barrier function and social behavior via Type 17 immunity. Cell Mar. 2022;185(5):831–846 e14. PMC8897247. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsuo K, Haku A, Bi B, Takahashi H, Kamada N, Yaguchi T, Saijo S, Yoneyama M, Goto Y. 2019. Fecal microbiota transplantation prevents Candida albicans from colonizing the gastrointestinal tract. Microbiol Immunol. May;63(5):155–163. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamaguchi N, Sonoyama K, Kikuchi H, Nagura T, Aritsuka T, Kawabata J. 2005. Gastric colonization of Candida albicans differs in mice fed commercial and purified diets. J Nutr. Jan;135(1):109–115. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenbach A, Dignard D, Pierce JV, Whiteway M, Kumamoto CA. 2010. Adaptations of Candida albicans for growth in the mammalian intestinal tract Eukaryot. Cell. Jul;9(7):1075–1086. PMC2901676. doi: 10.1128/ec.00034-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martin R, Albrecht-Eckardt D, Brunke S, Hube B, Hünniger K, Kurzai OA, Chauhan N. core filamentation response network in Candida albicans is restricted to eight genes. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58613. PMC3597736 in biomathematical services, which has been commissioned for routine analyses of transcriptome data by the Septomics Research Center This does not alter the authors’ adherence to all the PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garbe E, Gerwien F, Driesch D, Müller T, Böttcher B, Gräler M, Vylkova S, Liebeke M. Systematic metabolic profiling identifies de novo sphingolipid synthesis as hypha associated and essential for Candida albicans filamentation. mSystems. 2022. Oct 20;e0053922. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00539-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ribet D, Cossart P. 2015. Cossart P how bacterial pathogens colonize their hosts and invade deeper tissuest. Microbes Infec. Mar;17(3):173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou D, Chen LM, Hernandez L, Shears SB, Galán JE. 2001. A Salmonella inositol polyphosphatase acts in conjunction with other bacterial effectors to promote host cell actin cytoskeleton rearrangements and bacterial internalization. Mol Microbiol. Jan;39(2):248–259. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nikitas G, Deschamps C, Disson O, Niault T, Cossart P, Lecuit M. Transcytosis of Listeria monocytogenes across the intestinal barrier upon specific targeting of goblet cell accessible E-cadherin. J Exp Med. Oct 24 2011;208(11):2263–2277. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110560. PMC3201198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phan QT, Myers CL, Fu Y, Sheppard DC, Yeaman MR, Welch WH, Ibrahim AS, Edwards JE Jr, Filler SG, Heitman J. Als3 is a Candida albicans invasin that binds to cadherins and induces endocytosis by host cells. PLoS Biol. 2007. Mar;5(3):e64. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050064. PMC1802757 Therapeutics, Inc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dalle F, Wächtler B, L’Ollivier C, Holland G, Bannert N, Wilson D, Labruère C, Bonnin A, Hube B. Cellular interactions of Candida albicans with human oral epithelial cells and enterocytes. Cell Microbiol Feb. 2010;12(2):248–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goyer M, Loiselet A, Bon F, L’Ollivier C, Laue M, Holland G, Bonnin A, Dalle F. Intestinal cell tight junctions limit invasion of Candida albicans through active penetration and endocytosis in the early stages of the interaction of the fungus with the intestinal barrier. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0149159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149159. PMC4775037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moyes DL, Wilson D, Richardson JP, Mogavero S, Tang SX, Wernecke J, Höfs S, Gratacap RL, Robbins J, Runglall M, et al. Candidalysin is a fungal peptide toxin critical for mucosal infection. Nature. 2016. Apr 7;532(7597):64–68. PMC4851236. doi: 10.1038/nature17625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allert S, Förster TM, Svensson CM, Richardson JP, Pawlik T, Hebecker B, Rudolphi S, Juraschitz M, Schaller M, Blagojevic M, et al. Candida albicans-Induced Epithelial Damage Mediates Translocation through Intestinal Barriers. mBio. Jun 5 2018;9(3): 10.1128/mBio.00915-18. PMC5989070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lachat J, Pascault A, Thibaut D, Le Borgne R, Verbavatz JM, Weiner A. Trans-cellular tunnels induced by the fungal pathogen Candida albicans facilitate invasion through successive epithelial cells without host damage. Nat Commun. Jun 30 2022;13(1):3781. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31237-z. PMC9246882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mabbott NA, Donaldson DS, Ohno H, Williams IR, Mahajan A. 2013. Microfold (M) cells: important immunosurveillance posts in the intestinal epithelium. Mucosal Immunol. Jul;6(4):666–677. PMC3686595. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perdomo OJ, Cavaillon JM, Huerre M, Ohayon H, Gounon P, Sansonetti PJ. Acute inflammation causes epithelial invasion and mucosal destruction in experimental shigellosis. J Exp Med. 1994. Oct;180(4):1307–1319. PMC2191671. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones BD, Ghori N, Falkow S. Salmonella typhimurium initiates murine infection by penetrating and destroying the specialized epithelial M cells of the Peyer’s patches. J Exp Med. Jul 1 1994;180(1):15–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.15. PMC2191576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rescigno M, Urbano M, Valzasina B, Francolini M, Rotta G, Bonasio R, Granucci F, Kraehenbuhl JP, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Ricciardi-Castagnoli P Dendritic cells express tight junction proteins and penetrate gut epithelial monolayers to sample bacteria. Nat Immunol Apr. 2001;2(4):361–367. doi: 10.1038/86373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.De Jesus M, Rodriguez AE, Yagita H, Ostroff GR, Mantis NJ. 2015. Sampling of Candida albicans and Candida tropicalis by Langerin-positive dendritic cells in mouse Peyer’s patches. Immunol Lett. Nov;168(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Albac S, Schmitz A, Lopez-Alayon C, d’Enfert C, Sautour M, Ducreux A, Labruère-Chazal C, Laue M, Holland G, Bonnin A, et al. 2016. . Candida albicans is able to use M cells as a portal of entry across the intestinal barrier in vitro. Cell Microbiol. Feb;18(2):195–210. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leonardi I, Li X, Semon A, Li D, Doron I, Putzel G, Bar A, Prieto D, Rescigno M, McGovern DPB, et al. CX3CR1(+) mononuclear phagocytes control immunity to intestinal fungi. Science. Jan 12 2018;359(6372):232–236. 10.1126/science.aao1503. PMC5805464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Austermeier S, Kasper L, Westman J, Gresnigt MS. Gresnigt MS I want to break free - macrophage strategies to recognize and kill Candida albicans, and fungal counter-strategies to escape. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2020. Dec;58:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scherer AK, Blair BA, Park J, Seman BG, Kelley JB, Wheeler RT, May RC. 2020. Redundant Trojan horse and endothelial-circulatory mechanisms for host-mediated spread of Candida albicans yeast. PLoS Pathog. Aug;16(8):e1008414. PMC7447064. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fusco A, Savio V, Donniacuo M, Perfetto B, Donnarumma G. Antimicrobial peptides human beta-defensin-2 and −3 protect the gut during Candida albicans infections enhancing the intestinal barrier integrity: in vitro study front. Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:666900. PMC8223513. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.666900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fang Y, Wu C, Wang Q, Tang J. 2019. Farnesol contributes to intestinal epithelial barrier function by enhancing tight junctions via the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway in differentiated Caco-2 cells. J Bioenerg Biomembr. Dec;51(6):403–412. doi: 10.1007/s10863-019-09817-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Böhringer M, Pohlers S, Schulze S, Albrecht-Eckardt D, Piegsa J, Weber M, Martin R, Hünniger K, Linde J, Guthke R, et al. 2016. Candida albicans infection leads to barrier breakdown and a MAPK/NF-κB mediated stress response in the intestinal epithelial cell line C2BBe1. Cell Microbiol. Jul;18(7):889–904. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Frank CF, Hostetter MK. Cleavage of E-cadherin: a mechanism for disruption of the intestinal epithelial barrier by Candida albicans. Transl Res Apr. 2007;149(4):211–222. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eichner M, Protze J, Piontek A, Krause G, Piontek J. 2017. Targeting and alteration of tight junctions by bacteria and their virulence factors such as Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin. Pflugers Arch. Jan;469(1):77–90. doi: 10.1007/s00424-016-1902-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu Z, Nybom P, Magnusson KE. Distinct effects of Vibrio cholerae haemagglutinin/protease on the structure and localization of the tight junction-associated proteins occludin and ZO-1. Cell Microbiol Feb. 2000;2(1):11–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schmidt E, Kelly SM. van der Walle CF Tight junction modulation and biochemical characterisation of the zonula occludens toxin C-and N-termini. FEBS Lett. Jun 26 2007;581(16):2974–2980. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fasano A, Uzzau S, Fiore C, Margaretten K. 1997. The enterotoxic effect of zonula occludens toxin on rabbit small intestine involves the paracellular pathway. Gastroenterology. Mar;112(3):839–846. pm9041245. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Villar CC, Kashleva H, Nobile CJ, Mitchell AP, Dongari-Bagtzoglou A. 2007. Mucosal tissue invasion by Candida albicans is associated with E-cadherin degradation mediated by transcription factor Rim101p and protease Sap5p Infect. Immun. May;75(5):2126–2135. PMC1865768. doi: 10.1128/iai.00054-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grubb SE, Murdoch C, Sudbery PE, Saville SP, Lopez-Ribot JL, Thornhill MH. 2009. Adhesion of Candida albicans to endothelial cells under physiological conditions of flow Infect. Immun. Sep;77(9):3872–3878. PMC2738003. doi: 10.1128/iai.00518-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wilson D, Hube B. Hgc1 mediates dynamic Candida albicans-endothelium adhesion events during circulation Eukaryot. Cell Feb. 2010;9(2):278–287. doi: 10.1128/ec.00307-09. PMC2823009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Seman BG, Moore JL, Scherer AK, Blair BA, Manandhar S, Jones JM. 2018. Yeast and filaments have specialized, independent activities in a zebrafish model of Candida albicans infection infect. Immun. Oct;86:10. 10.1128/iai.00415-18. PMC6204735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saville SP, Lazzell AL, Monteagudo C, Lopez-Ribot JL. 2003. Engineered control of cell morphology in vivo reveals distinct roles for yeast and filamentous forms of Candida albicans during infection Eukaryot. Cell. Oct;2(5):1053–1060. PMC219382. doi: 10.1128/ec.2.5.1053-1060.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dunker C, Polke M, Schulze-Richter B, Schubert K, Rudolphi S, Gressler AE, Pawlik T, Prada Salcedo JP, Niemiec MJ, Slesiona-Künzel S, et al. Rapid proliferation due to better metabolic adaptation results in full virulence of a filament-deficient Candida albicans strain. Nat Commun. Jun 23 2021;12(1):3899. 10.1038/s41467-021-24095-8. PMC8222383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Eggimann P, Que YA, Revelly JP, Pagani J-L. Pagani JL Preventing invasive candida infections where could we do better? J Hosp Infect Apr. 2015;89(4):302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Davidson L, Netea MG, Kullberg BJ. Patient susceptibility to candidiasis-a potential for adjunctive immunotherapy. J Fungi (Basel). Jan 9 2018; 4(1): 10.3390/jof4010009. PMC5872312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Eggimann P, Pittet D. 2014. Candida colonization index and subsequent infection in critically ill surgical patients: 20 years later Intensive. Care Med. Oct;40(10):1429–1448. PMC4176828. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3355-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fox EP, Bui CK, Nett JE, Hartooni N, Mui MC, Andes DR, Nobile CJ, Johnson AD. An expanded regulatory network temporally controls Candida albicans biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol Jun. 2015;96(6):1226–1239. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13002. PMC4464956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Heilmann CJ, Sorgo AG, Siliakus AR, Dekker HL, Brul S, de Koster CG, de Koning LJ, Klis FM. 2011. Hyphal induction in the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans reveals a characteristic wall protein profile. Microbiology. Aug;157(Pt 8):2297–2307. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.049395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McCall AD, Pathirana RU, Prabhakar A, Cullen PJ, Edgerton M. Candida albicans biofilm development is governed by cooperative attachment and adhesion maintenance proteins. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2019;5(1):21. doi: 10.1038/s41522-019-0094-5. PMC6707306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nobile CJ, Schneider HA, Nett JE, Sheppard DC, Filler SG, Andes DR, Mitchell AP. Complementary adhesin function in C albicans biofilm formation. Curr Biol. Jul 22 2008;18(14):1017–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.034. PMC2504253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tati S, Davidow P, McCall A, Hwang-Wong E, Rojas IG, Cormack B, Edgerton M, Noverr MC. 2016. Candida glabrata binding to Candida albicans hyphae enables its development in oropharyngeal candidiasis. PLoS Pathog. Mar;12(3):e1005522. PMC4814137. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Andrutis KA, Riggle PJ, Kumamoto CA. Tzipori S Intestinal lesions associated with disseminated candidiasis in an experimental animal model. J Clin Microbiol Jun. 2000;38(6):2317–2323. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.6.2317-2323.2000. PMC86791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fradin C, De Groot P, MacCallum D, Schaller M, Klis F, Odds FC, Hube B. Granulocytes govern the transcriptional response, morphology and proliferation of Candida albicans in human blood. Mol Microbiol Apr. 2005;56(2):397–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fradin C, Kretschmar M, Nichterlein T, Gaillardin C, d’Enfert C, Hube B. Stage-specific gene expression of Candida albicans in human blood. Mol Microbiol Mar. 2003;47(6):1523–1543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hünniger K, Lehnert T, Bieber K, Martin R, Figge MT. Kurzai O A virtual infection model quantifies innate effector mechanisms and Candida albicans immune escape in human blood. PLoS Comput Biol Feb. 2014;10(2):e1003479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003479. PMC3930496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Machata S, Sreekantapuram S, Hünniger K, Kurzai O, Dunker C, Schubert K, Krüger W, Schulze-Richter B, Speth C, Rambach G, et al. Significant differences in host-pathogen interactions between murine and human whole blood. Front Immunol. 2020;11:565869. PMC7843371. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.565869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shen J, Cowen LE, Griffin AM, Chan L, Köhler JR. The Candida albicans pescadillo homolog is required for normal hypha-to-yeast morphogenesis and yeast proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Dec 30 2008;105(52):20918–20923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809147105. PMC2634893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Uppuluri P, Acosta Zaldívar M, Anderson MZ, Dunn MJ, Berman J, Lopez Ribot JL, Köhler JR. Candida albicans dispersed cells are developmentally distinct from biofilm and planktonic. Cells mBio. Aug 21 2018; 9(4): 10.1128/mBio.01338-18. PMC6106089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Uppuluri P, Chaturvedi AK, Jani N, Pukkila-Worley R, Monteagudo C, Mylonakis E, Köhler JR, Lopez Ribot JL. 2012. Physiologic expression of the Candida albicans pescadillo homolog is required for virulence in a murine model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis Eukaryot. Cell. Dec;11(12):1552–1556. PMC3536276. doi: 10.1128/ec.00171-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]