Abstract

The heat-labile toxin (LT) of Escherichia coli is a potent mucosal adjuvant that has been used to induce protective immunity against Helicobacter felis and Helicobacter pylori infection in mice. We studied whether recombinant LT or its B subunit (LTB) has adjuvant activity in mice when delivered with H. pylori urease antigen via the parenteral route. Mice were immunized subcutaneously or intradermally with urease plus LT, recombinant LTB, or a combination of LT and LTB prior to intragastric challenge with H. pylori. Control mice were immunized orally with urease plus LT, a regimen shown previously to protect against H. pylori gastric infection. Parenteral immunization using either LT or LTB as adjuvant protected mice against H. pylori challenge as effectively as oral immunization and enhanced urease-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) responses in serum as effectively as aluminum hydroxide adjuvant. LT and LTB had adjuvant activity at subtoxic doses and induced more consistent antibody responses than those observed with oral immunization. A mixture of a low dose of LT and a high dose of LTB stimulated the highest levels of protection and specific IgG in serum. Urease-specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibody subclass responses were stimulated by all immunization regimens tested, but relative levels were dependent on the adjuvant used. Compared to parenteral immunization with urease alone, LT preferentially enhanced IgG1, while LTB or the LT-LTB mixture preferentially enhanced IgG2a. Parenteral immunization using LT or LTB as adjuvant also induced IgA to urease in the saliva of some mice. These results show that LT and LTB stimulate qualitatively different humoral immune responses to urease but are both effective parenteral adjuvants for immunization of mice against H. pylori infection.

The immunogenicity of foreign proteins administered via mucosal routes is usually poor unless an adjuvant is used. The adjuvants most commonly used for mucosal immunization are cholera toxin (CT) and the similarly structured heat-labile toxin (LT) of Escherichia coli. CT and LT are ADP-ribosylating enterotoxins that cause diarrhea by inducing fluid secretion from intestinal epithelial cells. Coadministration of CT or LT with antigen via the oral, nasal, rectal, or other mucosal routes can result in substantial enhancement of antigen-specific secretory and systemic antibody responses and augmentation of cellular immunity (24, 35).

The mechanisms by which CT and LT exert their adjuvant effects, including the relationship between toxicity and adjuvanticity, are not precisely defined. Both toxins are composed of a single A subunit and five identical B subunits. The nontoxic B subunit (CTB or LTB), which is responsible for binding of toxin to target cells, has been used as a carrier to enhance cellular uptake of physically linked antigens (13, 42) and also has adjuvant activity when mixed with antigen and administered nasally (16, 18, 20, 56, 58, 64). The role of ADP-ribosyltransferase activity, which resides within the A subunit, has been studied using site-directed mutagenesis to create CT and LT molecules with altered enzymatic activity. Although the results vary among different reports, mutant toxins with reduced or absent ADP-ribosyltransferase activity have been found to retain moderate to strong adjuvant activity in some cases, particularly if delivered nasally (17, 18, 20, 27, 57, 66). Some of these studies have shown that while ADP-ribosylation is not required for adjuvanticity, low-level activity enhances the adjuvant effect (20, 27).

Although the adjuvant activity of CT was demonstrated initially with intravenous immunization (49), CT and LT have been used most often to enhance mucosal immunization. Nevertheless, the parenteral adjuvant effects of CT and LT have been confirmed in experiments involving immunization via the subcutaneous (67), intraperitoneal (1, 53, 65), intravenous (36, 59), intradermal (2), and transcutaneous (28, 29) routes. Nontoxic CT and LT mutants also have adjuvant activity when delivered subcutaneously (57, 67). CTB purified from CT holotoxin (thus containing a low level of active toxin) was found to augment antibody and cytolytic-T-cell responses when delivered parenterally (34, 45) but recombinantly produced CTB lacked adjuvant activity when delivered subcutaneously in one study (67).

One pathogen against which mucosally delivered CT and LT adjuvants have been used effectively is Helicobacter pylori. In humans, H. pylori establishes a chronic infection of the gastric mucosa leading to the development of gastritis, gastric and duodenal ulcers, and gastric cancer (4, 11). Mucosal immunization with H. pylori cell lysate or urease antigen mixed with CT or LT reduces gastric colonization of mice by H. pylori or the related bacterium Helicobacter felis upon subsequent challenge (9, 14, 37, 40, 44, 47). CTB purified from holotoxin was reported to protect mice against H. felis infection when delivered orally with antigen (38), but it was shown later that the effect was probably dependent of the presence of residual holotoxin, since recombinant CTB did not have similar adjuvant activity (7). Although initial vaccine studies with mice focused on the mucosal route of immunization, recent studies have shown that a variety of parenteral immunization regimens also protect mice against H. pylori infection (25, 32).

In the study presented here, we explored the parenteral adjuvant activities of LT and LTB for immunization of mice against H. pylori infection. One goal was to determine whether LT delivered subcutaneously or intradermally might have adjuvant activity similar to that of mucosally delivered LT, while avoiding enterotoxicity. We also tested whether recombinant LTB alone might have parenteral adjuvant activity and whether parenteral delivery of LT and LTB together might have an additive or synergistic effect, as has been shown with mucosal delivery (55, 63). Finally, we examined postimmunization immunoglobulin G (IgG) subclass responses in serum and IgA responses in saliva to determine how the adjuvant and route of delivery affect the type of antibody response and whether parenterally delivered LT or LTB enhances secretory antibody responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antigens and adjuvants.

Recombinant H. pylori urease was expressed in E. coli ORV214 and purified by anion-exchange chromatography as described previously (40). Endotoxin concentration, as determined by the Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay, was reduced to 1.5 ng of urease per mg by using a Sartobind Q filter (Sartorius Corp., Edgewood, N.Y.). Recombinant LT was obtained from Berna Products Corp. (Coral Gables, Fla.). For trypsin cleavage, 100 μg of LT was mixed with 1 μg of bovine pancreas trypsin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) in 200 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated for 60 min at 37°C. Enzymatic activity was stopped by addition of 100 μg of soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma). For production of recombinant LTB, the LTB gene was amplified from plasmid pBD94 by PCR and cloned in pET24+ for expression under control of the T7 promoter in E. coli strain XL1-Blue (19). Plasmid pORV319 was introduced into BL21(DE3) for expression. ORV319 was grown in Luria broth containing 50 μg of kanamycin per ml to mid-logarithmic phase and then induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Sigma). Bacterial cells were harvested 5 h later, washed in 200 mM NaCl–50 mM Tris–1 mM EDTA (TEN), and lysed with a French pressure cell. Whole cells and debris were removed by centrifugation, and the cleared lysate was applied to a galactose affinity resin (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Ill.). LTB was eluted with 200 mM galactose in TEN and dialyzed into PBS (pH 7.2) with 5% lactose at a protein concentration of 0.5 mg/ml. Endotoxin was reduced to <5 ng/mg with a Sartobind Q filter.

Y-1 cell-rounding assay.

The toxicity of LT and LTB was assessed with a modified cell-rounding assay (8). In brief, 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates were seeded with Y-1 mouse adrenal cells at 2 × 104 cells/well in minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Following incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 for ≥2 h to allow spreading of cells on the substrate, medium was removed from wells and replaced with medium containing serial twofold dilutions of LT or LTB, and the plates were returned to the incubator. After overnight incubation at 37°C, the cells were viewed with an inverted microscope. The toxin potency was defined as the lowest concentration at which ≥50% of cells were rounded (i.e., the 50% effective dose [ED50]).

Immunization and sampling.

Procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of OraVax, Inc. Specific-pathogen-free, 6- to 8-week-old female Swiss-Webster mice were purchased from Taconic Laboratories (Germantown, N.Y.). Mice were immunized with urease via the oral, subcutaneous, or intradermal route. Three doses were given with a 2-week interval between the doses. For oral immunization, 25 μg of urease and 1 μg of LT in a volume of 25 μl were pipetted into the mouth. For subcutaneous immunization, 10 μg of urease was injected into the lower back, with or without LT, LTB, or aluminum hydroxide (alum) adjuvant, in a volume of 100 μl. Equal volumes of alum (Rehydrageli Reheis, Inc., Berkeley Heights, N.J.) at 4 mg/ml and urease at 200 μg/ml were mixed for 30 to 60 min prior to injection. For intradermal immunization, a patch of skin on the back was shaved, the mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation, and 10 μg of urease with LT or LTB adjuvant was delivered via a 30-gauge needle in a volume of 50 μl.

Blood and saliva were sampled approximately 1 week after the third immunization. Blood was collected from the retro-orbital sinus while mice were under isoflurane inhalation anesthesia, and saliva was collected from the mouth with a micropipette after intraperitoneal injection of 70 to 100 μg of pilocarpine.

Challenge, analysis of colonization, and histopathology.

Approximately 2 weeks after the final immunization, mice were challenged intragastrically with a single dose of 107 live streptomycin-resistant H. pylori X47-2AL bacteria (37). Challenge bacteria were grown on Mueller-Hinton agar plates containing 10% sheep blood and transferred to Brucella broth as described previously (37). The challenge dose was delivered intragastrically in a volume of 100 μl using a blunt-tipped feeding needle. Mice were sacrificed 2 weeks after challenge to assess gastric colonization by H. pylori. The stomach was removed, rinsed with 0.9% NaCl solution, and cut open along the lesser and greater curvatures. One quarter of the antrum was placed into 1 ml of Brucella broth supplemented with 5% calf serum and disrupted using a Dounce homogenizer fitted with a loose pestle. Tenfold dilutions of homogenate were inoculated onto Mueller-Hinton agar containing 10% sheep blood and 5 μg of amphotericin B, 5 μg of trimethoprim, 10 μg of vancomycin, 10 U of polymyxin B sulfate, and 50 μg of streptomycin per ml. Plates were incubated at 37°C in 7% CO2, and colonies were counted 5 to 7 days later.

For analysis of gastritis, a strip of stomach tissue including portions of the antrum and corpus was fixed with 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A previously described scoring system (40) was used to assign gastritis scores of 0 (no infiltration by lymphocytes, plasma cells, or polymorphonuclear cells), 1 (scattered infiltrating cells in the deep mucosa), 2 (moderate infiltrating cells in the deep to mid-mucosa and occasional neutrophils in glands), 3 (dense infiltrates, with occasional abscessed glands and lymphocytic nodules), or 4 (dense infiltrates throughout the lamina propria and in the submucosa and lymphoid nodules).

Antibody analysis.

Antibody responses in serum and saliva were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Flat-bottom 96-well plates were coated overnight at 4°C with 0.5 μg of urease per well in 100 μl of 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.6). Wells were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-Tween), and PBS-Tween containing 2.5% nonfat dry milk (blocking buffer) was added to block nonspecific binding. Blocking buffer was used as a diluent for test samples and antibody conjugates. Samples and reagents were added to wells in 100-μl volumes, and wells were washed with PBS-Tween between steps. For IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a determination, serum was diluted 1/100 and then further diluted with a series of fivefold dilutions. After removal of the blocking buffer, 100 μl of each dilution was added in duplicate and plates were incubated for 60 min at 28°C. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, IgG1, or IgG2a antibodies (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.), each diluted 1/1,000, were added to wells next, and plates were incubated for 60 min at 28°C. For the final step, 100 μl of a 1-mg/ml concentration of p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate (Sigma) in 1 M diethanolamine buffer (pH 9.6) containing 5 mM MgCl2 was added. Plates were incubated for 40 min at 28°C, and the A405 was read with a Vmax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, Calif.). The average absorbance value of duplicate wells was plotted, and a curve was fitted to the data points using the power function of Cricket Graph III software (Computer Associates International, Inc., Islandia, N.Y.) running on an Apple Macintosh computer. The titer of each sample was defined as the reciprocal of the dilution corresponding to an A405 of 0.1, which was approximately three times the background absorbance for normal mouse serum at a 1/100 dilution. Samples with an A405 of >0.1 at a 1/100 dilution were assigned a titer of 50. For determination of salivary IgA levels, saliva was tested at a single dilution of 1/10, and the results are reported as the average A405 for duplicate wells. The assay procedure for IgA determination was otherwise as described above except that goat anti-mouse IgA alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Southern Biotechnology) was used to detect bound salivary IgA antibodies.

For quantitation of IgE to urease, a capture ELISA was used. Flat-bottom 96-well plates were coated overnight with 100 μl of rat monoclonal antibody clone 23G3 against mouse IgE (Southern Biotechnology) at a concentration of 1 μg/ml. Wells were washed and blocked with nonfat milk as described above, and 100 μl of mouse serum, diluted 1/100, was added to wells in duplicate. After incubation for 1 h at 28°C, the plates were washed, and urease, at 2.5 μg/ml, was added to the wells. The plates were again incubated for 1 h at 28°C. In subsequent steps, wells were treated with rabbit antiserum to urease diluted 1/4,000, and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma) at a 1/2,000 dilution. Plates were incubated for 1 h at 28°C at each step. Addition of substrate solution and measurement of absorbance were done as described above.

Statistical analysis.

Differences in H. pylori colonization and antibody responses between groups were analyzed by the Wilcoxon rank sum test using JMP software (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

RESULTS

Characterization of recombinant LT and LTB.

LT and LTB were tested for toxicity using a Y-1 cell-rounding assay (8). LT was tested before and after treatment with trypsin, which activates the toxin by cleavage of the A subunit. The dose of untreated LT required for 50% cell rounding (ED50) was 0.2 ng/ml. After trypsin treatment, the ED50 fell to 0.1 ng/ml, indicating that approximately 50% of the LT was active prior to trypsin treatment. LTB had no activity in the assay when tested at concentrations of up to 100 μg/ml.

Adjuvant effects of parenterally delivered LT and LTB for protection against H. pylori challenge.

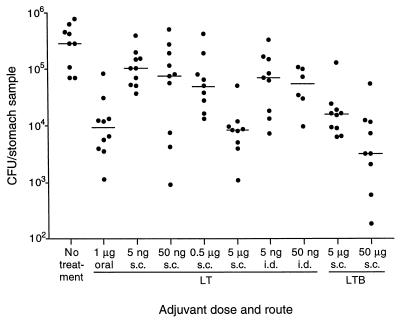

Mice were immunized subcutaneously or intradermally with 10 μg of H. pylori urease mixed with 5 ng to 5 μg of recombinant LT or 5 to 50 μg of recombinant LTB. As a positive control, mice were immunized orally with 25 μg of urease plus 1 μg of LT, a regimen shown previously to protect against H. pylori challenge (25). A schedule of three immunizations with a 2-week interval between doses was used. Mice injected subcutaneously with the two higher doses of LT (0.5 and 5 μg) developed swelling at the injection site that was still present 2 weeks after the first immunization. As a result, the second dose was omitted in these two groups, and a single boosting immunization was given 4 weeks after the first dose, at which point the swelling had subsided. Injection site swelling consisted of a raised area approximately 1 cm in diameter with no skin color change or necrosis apparent. No other signs of toxicity were observed. Mice injected intradermally with 0.5 or 5 μg of LT also experienced injection site swelling. Because swelling did not subside as quickly in these mice, further immunization was not performed and the mice were removed from the study. Two weeks after the final immunization, mice were challenged intragastrically with mouse-adapted H. pylori X47-2AL. Gastric colonization was assessed 2 weeks after challenge. The median level of gastric H. pylori colonization in unimmunized mice was 2.9 × 105 CFU/stomach sample (Fig. 1). In mice immunized orally with urease plus LT, the median level was 9.1 × 103 CFU/sample, a significant reduction in colonization (P = 0.0004, Wilcoxon rank sum test) that was consistent with previous experiments using the X47-2AL challenge strain (25, 37).

FIG. 1.

Gastric H. pylori colonization in mice following oral, subcutaneous (s.c.), or intradermal (i.d.) immunization with urease and various doses of LT or LTB. Mice were either unimmunized (no treatment), immunized two times (subcutaneously with 0.5 or 5 μg of LT), or immunized three times (remaining groups) and challenged with H. pylori orally 2 weeks after the final dose. For oral immunization, 25 μg of urease was delivered with 1 μg of LT. For subcutaneous and intradermal immunization, 10 μg of urease was delivered with the dose of adjuvant shown. Symbols show the CFU per quarter antrum of individual mice. The horizontal lines show the median for each group.

Subcutaneous delivery of urease with the highest dose of LT (5 μg) was as effective as oral immunization, resulting in a significantly reduced (P = 0.0003) median H. pylori level of 8.3 × 103 CFU/sample (Fig. 1). Subcutaneous delivery of urease with lower doses of LT reduced gastric colonization to a lesser, but still significant (P < 0.05) extent. Intradermal injection of urease with 5 or 50 ng of LT was similar in effectiveness to subcutaneous delivery of the same doses. Subcutaneous delivery of urease with 50 μg of LTB reduced the median level of H. pylori to 3.2 × 103 CFU/sample (P = 0.0003), the lowest level in any of the groups. A smaller but significant effect (P = 0.0006) was also seen when 5 μg of LTB was used.

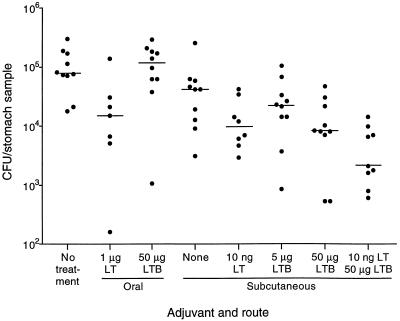

Adjuvant effects of orally delivered LTB and parenterally delivered LT-LTB mixture.

A second experiment, using the same immunization schedule and challenge procedure as described above, was designed to examine several questions regarding the adjuvant activities of LT and LTB with urease, including whether LTB was active orally, whether subcutaneously delivered urease was protective without LT or LTB, and whether a combination of LT and LTB was more effective than either molecule alone. As shown in Fig. 2, oral delivery of urease plus 1 μg of LT reduced gastric colonization to a median level of 1.5 × 104 CFU/sample from a median of 7.9 × 104 CFU/sample in unimmunized mice (P = 0.02). Oral delivery of urease with 50 μg of LTB, however, had no effect on colonization (P = 0.82). Subcutaneous immunization with urease alone reduced the median H. pylori level slightly from that of unimmunized mice (P = 0.02), and addition of LT or LTB enhanced the protective effect (P ≤ 0.01). As in the previous experiment, LTB was more effective at the higher dose (50 μg) than at the lower dose (5 μg). Administration of 50 μg of LTB in the absence of urease had no effect on colonization (data not shown). The greatest effect was seen when a mixture of 50 μg of LTB and 10 ng of LT was used as the adjuvant for subcutaneous immunization. In this group, colonization was reduced to 2.1 × 103 CFU/sample (P = 0.0002).

FIG. 2.

Gastric H. pylori colonization in mice following oral or subcutaneous immunization with urease alone or mixed with LT or LTB. Mice were either unimmunized (no treatment) or immunized three times with urease plus the adjuvants shown and challenged with H. pylori orally 2 weeks after the final immunization. For oral immunization, 25 μg of urease was delivered with 1 μg of LT. For subcutaneous immunization, 10 μg of urease was delivered with the dose of adjuvant shown. Symbols show the numbers of CFU per quarter antrum of individual mice. The horizontal lines show the median for each group.

Stained sections of gastric antrum and corpus collected at sacrifice were examined microscopically, and the extent of gastritis was scored from 0 (no gastritis) to 4 (severe gastritis). In line with previous results (32), only moderate gastritis developed during this relatively short period after H. pylori challenge. The highest median gastritis score of 2.8 was found in the group that received urease plus LT and LTB subcutaneously. In comparison, the median gastritis score was 2.4 in the unimmunized group and 2.5 in the group treated orally with urease plus LT.

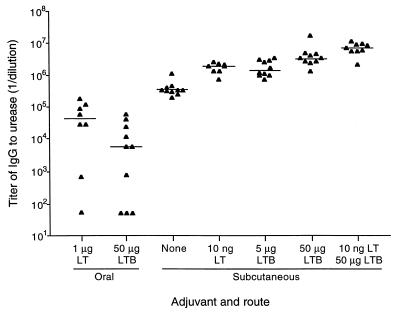

Antibody responses to urease following parenteral delivery of urease with LT and LTB adjuvants.

Serum and saliva collected after immunization, but before H. pylori challenge, were examined to determine the effects of different adjuvants and routes of immunization on the magnitude and type of antibodies elicited against urease. IgG to urease was not detected in the serum of unimmunized mice when tested at a 1/100 dilution. Oral immunization with urease plus LT elicited low to moderate titers of urease-specific IgG (Fig. 3). IgG titers were similar when mice were immunized orally using LTB as adjuvant. In serum from subcutaneously immunized mice, IgG levels in all groups were higher than those obtained with oral immunization, and responses were more uniform within each group. Subcutaneous immunization with urease alone resulted in IgG titers of >5 log10, while the addition of LT or LTB increased titers severalfold (P = 0.06 and P < 0.005, respectively, comparing the LT group and the LTB groups against the no-adjuvant group). As with protection, coadministration of LT and LTB had an additive effect, resulting in a urease-specific IgG titer of 6.9 log10, a 20-fold increase over the median titer in mice immunized with urease in the absence of adjuvant (P = 0.002).

FIG. 3.

Titers of IgG to urease in sera of immunized mice. Mice were immunized three times orally or subcutaneously with urease plus the adjuvants shown. Serum was collected 1 week after the final immunization and tested for urease-specific IgG by ELISA. Endpoint titers for individual mice are shown. Samples in which no specific antibody was detected were assigned a titer of 50. The horizontal lines show the median titer for each group.

Analysis of serum IgG1 and IgG2a levels showed differences in the quality of the urease-specific IgG response among different groups (Table 1). In comparison to subcutaneous immunization, oral immunization tended to elicit lower levels of both IgG1 and IgG2a and a lower IgG1/IgG2a ratio, whether LT or LTB was delivered with urease. In contrast, subcutaneous LT and LTB elicited urease-specific IgG responses that were qualitatively different from each other. Subcutaneous delivery of urease alone elicited strong IgG1 and IgG2a responses, and the levels of both isotypes were enhanced by addition of LT or LTB. However, LT stimulated a greater increase in IgG1 than in IgG2a, while LTB stimulated a greater increase in IgG2a than in IgG1. When LT and LTB were delivered together, the effect of LTB appeared to be dominant, since the median IgG2a titer of 6.7 log10 was the highest of any group and nearly 80-fold higher than that of mice receiving urease without adjuvant.

TABLE 1.

Serum IgG1 and IgG2a antibody responses following immunization with urease alone or urease with LT, LTB, or alum adjuvant

| Adjuvant (amt) | Antigen (μg of urease) | Routeb | Median log10 titer (range)a

|

IgG1/IgG2a ratio (range)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG1 | IgG2a | ||||

| LT (1 μg) | 25 | Oral | 3.1 (1.7–4.5) | 4.3 (1.7–5.2) | 0.2 (0.01–1.6) |

| LTB (50 μg) | 25 | Oral | 2.2 (1.7–4.7) | 3.5 (1.7–4.5) | 0.03 (0.01–5.2) |

| None | 10 | s.c. | 5.7 (5.5–6.3) | 4.8 (3.9–5.4) | 8.3 (3.9–56.7) |

| LT (10 ng) | 10 | s.c. | 6.7 (6.3–7.2) | 5.3 (4.7–6.1) | 30.1 (1.9–257.7) |

| LTB (5 μg) | 10 | s.c. | 6.3 (5.8–6.8) | 5.8 (5.2–6.4) | 4.7 (0.2–8.0) |

| LTB (50 μg) | 10 | s.c. | 6.5 (6.0–6.9) | 6.2 (5.5–6.5) | 2.1 (0.7–5.8) |

| LT (10 ng) plus LTB (50 μg) | 10 | s.c. | 6.8 (6.2–7.2) | 6.7 (6.2–6.9) | 1.0 (0.6–4.0) |

| Alum | 10 | s.c. | 6.6 (6.0–7.0) | 5.5 (4.8–5.8) | 11.8 (3.9–53.2) |

Titers of urease-specific IgG1 and IgG2a were determined by ELISA. Titers are defined as 1/dilution of serum giving an A405 of 0.1. Samples that were negative at the lowest dilution tested (1/100) were assigned a titer of 50 (1.7 log10).

Adjuvant and antigen were mixed and delivered by the oral or subcutaneous (s.c.) route.

Mice with undetectable levels of both IgG1 and IgG2a (two mice in the first group; three mice in the second group) were not included in calculations of IgG1/IgG2a ratios.

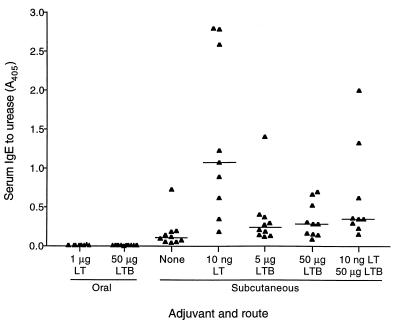

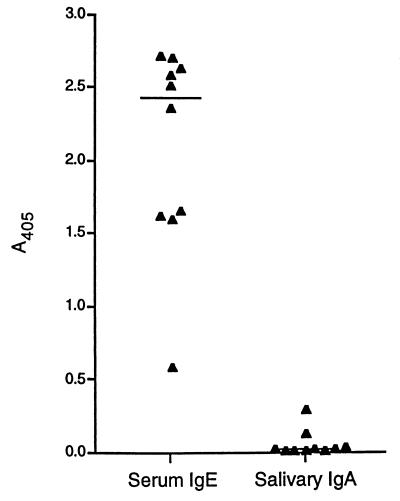

Serum IgE to urease was generated only by parenteral immunization (Fig. 4). Subcutaneous immunization with urease alone stimulated a low level IgE response in most mice. The addition of LT adjuvant increased IgE levels, although responses were highly variable. The median IgE response in mice receiving LTB adjuvant was only slightly higher than that of mice receiving no adjuvant. LT and LTB together led to levels that were somewhat higher than those seen with LTB alone.

FIG. 4.

IgE to urease in sera of immunized mice. Mice were immunized three times orally or subcutaneously with urease plus the adjuvants shown. Serum was collected 1 week after the final immunization and tested for urease-specific IgE at a 1/100 dilution by ELISA. Absorbance values for individual mice are shown. A horizontal line shows the median value for each group.

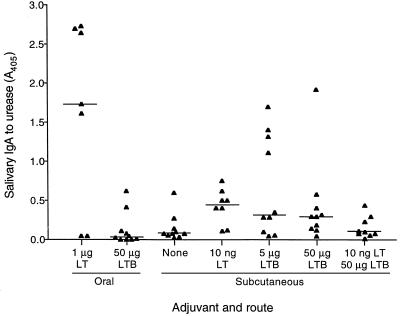

IgA to urease in saliva was greatest when mice were immunized orally and LT adjuvant was used, although not all mice had a detectable IgA response (Fig. 5). Delivery of urease orally with LTB or subcutaneously without adjuvant stimulated only low levels of specific IgA in saliva. LT stimulated low levels of salivary IgA in most mice when delivered subcutaneously with urease, while LTB had a similar effect but also induced moderate levels of salivary IgA in several mice. When LT and LTB were delivered together, specific salivary IgA was not increased over the level seen when mice were immunized with urease alone.

FIG. 5.

IgA to urease in saliva samples of immunized mice. Mice were immunized three times orally or subcutaneously with urease plus the adjuvants shown. Saliva was collected 1 week after the final immunization and tested for urease-specific IgA at a 1/10 dilution by ELISA. Absorbance values for individual mice are shown. A horizontal line shows the median value for each group.

Antibody responses to urease following parenteral delivery of urease with alum adjuvant.

To compare the adjuvant activities of LT and LTB with a more conventional parenteral adjuvant, mice were immunized subcutaneously with urease adsorbed to alum (aluminum hydroxide) adjuvant. As in the experiments described above, mice were immunized three times and blood and saliva were collected 1 week after the final immunization. This regimen was shown previously to reduce colonization of the stomach following H. pylori challenge, but it was less effective than oral immunization with urease plus LT (25). The titer of specific IgG in serum after immunization with urease adsorbed to alum ranged from 5.7 to 7.1 log10, with a median of 6.3 log10. This was the same approximate level of serum IgG elicited by subcutaneous delivery of urease plus LT or LTB. The median titers of IgG1 and IgG2a in serum following urease plus alum immunization were 6.6 and 5.5, respectively (Table 1). IgG1/IgG2a ratios were relatively high, ranging from 3.9 to 53.2. This range was similar to that obtained with subcutaneous delivery of urease alone or with LT. IgE levels were higher with alum than with LT or LTB as adjuvant, with A405 values for urease-specific IgE exceeding 2.0 in over half of the mice that received alum (Fig. 6). Only slight salivary IgA responses were stimulated with alum as adjuvant.

FIG. 6.

Urease-specific IgE in serum and IgA in saliva of mice immunized three times subcutaneously with urease adsorbed to alum adjuvant. Serum and saliva were collected 1 week after the final immunization and tested for urease-specific antibody by ELISA. Absorbance values for individual mice are shown. A horizontal line shows the median value for each group.

DISCUSSION

The adjuvant properties of mucosally delivered CT and LT are well established. Less is known about the activities of these toxins when they are delivered parenterally. The results of our study demonstrate the value of LT and LTB as adjuvants for parenteral immunization of mice against H. pylori and show that holotoxin and B subunit stimulate qualitatively different immune responses to a coadministered antigen.

Previous studies in mice, gnotobiotic pigs, and rhesus monkeys showed that mucosal delivery of antigen mixed with CT or LT adjuvant induces immunity to infection by H. felis or H. pylori (9, 15, 21, 23, 37, 39, 40, 44). The mucosal route of immunization was used in early studies with mice. The choice of this route was logical, since H. pylori colonizes the luminal surface of the gastric epithelium, and secretory IgA, which is best stimulated by mucosally delivered antigen, is considered a major mediator of immunity against mucosal pathogens (46). In support of this, we found previously that parenteral immunization of mice with H. pylori urease plus Freund's adjuvant was minimally protective against H. felis challenge, while oral or nasal immunization with urease plus CT or LT was highly effective (40, 61). Other studies, however, have shown that parenteral immunization can protect against H. pylori challenge as effectively as mucosal immunization (22, 23, 25, 32). Moreover, studies with immunoglobulin-deficient mice show that protection can be achieved in the absence of antibody responses, demonstrating that secretory IgA is not required for protection (6, 25).

Parenteral delivery of LT is advantageous in that the toxin does not contact intestinal epithelial cells and thus does not cause diarrhea. Other toxic effects are possible, however, since ganglioside GM1, the major LT cell surface receptor, is present on most cells (12). It was shown previously that CT has an LD50 of 6.8 μg when delivered intravenously to mice and that a majority of mice died following intraperitoneal delivery of 25 μg of LT (10, 31). In our study, subcutaneous or intradermal delivery of 0.5 to 5 μg of LT caused swelling at the injection site but resulted in no other signs of toxicity. At lower doses, there was no apparent toxicity, but adjuvant activity was retained. No toxicity was observed when LTB was injected at doses of up to 50 μg, yet it matched the effectiveness of LT in augmenting protective immunity when it was delivered at the higher dose.

A mixture of LT and LTB had the greatest adjuvant effect for protection against H. pylori challenge. This effect may be akin to the strong adjuvant activity seen in studies using mucosally delivered mixtures of CT or LT and its B subunit. These studies showed that delivery of a trace amount of holotoxin with a high dose of B subunit results in a synergistic adjuvant effect (55, 63). In these experiments, doses of CT or LT were close to or below the minimally effective level. Our experiment differed in that the LT dose used, although small, was already quite effective on its own. Nevertheless, an additive effect of the combined adjuvants was apparent. It has been hypothesized that the synergism of CT and CTB in mucosal immunization results from blockage of GM1 binding sites by CTB, allowing active CT molecules to bind to a greater number of cells, albeit with fewer CT molecules binding per cell (35). Thus, excess CTB might allow CT to reach more epithelial cells, including antigen-transporting M cells, which have abundant CT receptors (26). The additive effect of LT and LTB that we observed with subcutaneous injection might be explained similarly: excess LTB could allow LT to bind more cells at lower density or could allow LT to reach more of the cells involved in generating protective immunity. Alternatively, LT and LTB might have independent adjuvant activities that in combination induce a greater immune response. In support of this hypothesis, recent experiments using site-directed mutagenesis suggest that there are at least two adjuvant activities for LT, one associated with the B subunit that is dependent on GM1 binding and a second associated with the A subunit that is independent of GM1 binding (17, 18, 60). Neither activity requires ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Other studies suggest that enzymatically inactive CT or LT mutants have adjuvant activity but that low-level ADP-ribosyltransferase activity augments adjuvanticity (20, 27). Toxin mutants with low-level activity might provide the same stimulatory signals as a mixture of B subunit with a small amount of active holotoxin.

In our study, LTB did not exhibit an adjuvant effect for protection of mice against H. pylori challenge when oral immunization was used. This observation supports the recent study by Blanchard et al. (7), which showed that mice are not protected against H. felis challenge when recombinant CTB is used as an oral adjuvant. Our LTB dose was five times higher than the dose of CTB used, providing greater evidence for the lack of oral B subunit activity. These results are consistent with the findings of a number of other studies showing that recombinant or highly purified CTB or LTB has mucosal adjuvant activity when delivered nasally but little or no activity when delivered orally (16, 18, 20, 43, 56, 58, 60, 64).

We found that parenterally delivered LT and LTB were also strong adjuvants for induction of antibody to urease. Although antibody is not required for the protection of mice against H. pylori challenge, we felt that an analysis of antibody responses was warranted in order to characterize the immunomodulating properties of these adjuvants. In the parenterally immunized groups, specific IgG responses mirrored the level of protection against challenge, with a mixture of LT and LTB inducing the highest levels of IgG to urease. However, IgG responses did not correlate with protection overall because mice that were immunized orally were protected but had low specific IgG levels. IgG responses to oral immunization were also more variable than responses to subcutaneous immunization, suggesting that an advantage of parenteral immunization is that it gives more uniform results. IgG levels with LT, LTB, or LT-LTB as adjuvant were all at least as high as those produced by immunization with alum. Our results appear to conflict with those of Yamamoto et al. (67), who found that CTB had no adjuvant activity when delivered subcutaneously with ovalbumin. It is possible that for parenteral immunization, as with intranasal immunization (20), LTB has a greater adjuvant effect than CTB or that activity varies with different antigens.

Analysis of urease-specific IgG subclass responses in our study showed that all immunization regimens tested induced both IgG1 and IgG2a responses but that relative levels of the two subclasses varied with both the route of immunization and the adjuvant. Subcutaneous immunization with urease plus alum adjuvant, which is known to preferentially stimulate the Th2 subset of helper T cells (30), induced relatively high IgG1/IgG2a ratios and a specific IgE response. Oral delivery of urease plus LT resulted in relatively low IgG1/IgG2a ratios and no IgE, which is consistent with stimulation of both Th1 and Th2 cells, as seen with mucosal delivery by others (20, 54). When delivered subcutaneously, LT and LTB had clearly different effects on IgG subclass responses. Relative to subcutaneous delivery of urease alone, IgG1/IgG2a ratios were increased when LT was added and decreased when LTB was added. Although this might suggest that activity of the LT A subunit preferentially stimulates IgG1 responses, a mixture of LT plus LTB gave responses that were more similar to those of LTB alone, i.e., low IgG1/IgG2a ratios and low IgE levels. Others, however, have reported that native LT and nontoxic derivatives give IgG1/IgG2a patterns that are similar to each other, indicating that ADP-ribosyltransferase activity does not modulate IgG subclass responses (20, 54). In all cases, we observed substantial increases in titers of both IgG1 and IgG2a. Yamamoto et al., in contrast, found that there was no antigen-specific IgG2a response when CT was used as a subcutaneous adjuvant (67). This may indicate that, as with mucosal immunization, parenterally administered CT preferentially stimulates Th2 responses, whereas LT stimulates both Th1 and Th2 responses (20, 54, 56, 66).

In previous studies, specific IgG2a and IgG1 levels have also been used as markers of Th1 and Th2 responses in mice immunized with H. pylori urease and different adjuvants (25, 32). In these studies, adjuvants that stimulated higher levels of IgG2a, in addition to IgG1, were more likely to elicit protective immunity against H. pylori challenge. This is consistent with the observation that protection appears to be mediated by a major histocompatibility complex class II-dependent, antibody-independent cellular mechanism (6, 25, 50). In our current study, we did not see a clear correlation between IgG1/IgG2a ratios and protection. A comparison of IgG subclass responses to oral and parenteral immunization is difficult, since oral immunization induces weak circulating antibody levels. Among parenterally immunized groups, protection was associated more with the overall magnitude of the urease-specific IgG response than with increases in either IgG1 or IgG2a. This study was not designed to examine changes in disease, as mice were sacrificed only 2 weeks after challenge. The moderate levels of gastritis observed did not appear to vary in association with the level of bacterial colonization, the magnitude of the circulating IgG response, or the level of either IgG1 or IgG2a subclass antibodies.

Not unexpectedly, we found that the highest IgA responses in saliva were stimulated by oral immunization using LT adjuvant, although levels were highly variable among individual mice. Subcutaneous immunization with urease alone or urease plus alum adjuvant resulted in little or no salivary IgA response. Interestingly, low levels of salivary IgA against urease were stimulated in most mice when LT and LTB were used as subcutaneous adjuvants. Several mice immunized subcutaneously with LTB as adjuvant had moderate salivary IgA responses. These results suggest that LT and LTB may stimulate mucosal immunity to a certain extent even if not delivered by a mucosal route.

A number of recent studies have demonstrated that the B subunits of CT or LT can induce immunological tolerance when linked to or coadministered with antigens. For example, CTB was reported to induce tolerance when conjugated to several different proteins and delivered mucosally at low doses (3, 5, 51, 52). In another study, alum-adsorbed LTB was found to induce tolerance to type II collagen in mice when injected subcutaneously with antigen (62). Tolerance was induced even though LTB and antigen were injected at separate sites or at different times. We found no evidence of a toleragenic response in mice injected with urease plus LTB, although we did not measure other outcomes, such as delayed-type hypersensitivity activity, which might have shown such an effect.

Clinical testing of the mucosal adjuvant activities of CT, LT, and B subunit has begun in recent years (33, 48). Humans have been found to be more sensitive to the diarrheagenic effects of CT and LT than mice (41, 48), suggesting that strategies to reduce toxicity are necessary. Potential strategies include the use of a trace amount of LT supplemented with LTB (33) and the use of mutant toxin molecules with reduced ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Parenteral delivery represents an additional strategy for reduction of toxicity. Our results suggest that parenteral immunization with low doses of LT, LTB, or especially an LT-LTB mixture might provide systemic immunity at levels achieved with alum adjuvant, while also stimulating a modest secretory IgA response, with minimal side effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kathleen Georgakopoulos, Heather Gray, Jennifer Ingrassia, Timothy Tibbitts, Penny Papastathis, and Mary Ann Giel of OraVax for excellent technical assistance and Steven Truong and Nancy Tobin of OraVax for animal care. We also thank Cynthia Lee, Harry Kleanthous, Gwendolyn Myers, and Richard Nichols of OraVax and Kenneth Sokoll of Pasteur Merieux Connaught for helpful discussions and Joseph Hill, Clemson University, for histopathological analysis of stomach tissue.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agren L C, Ekman L, Lowenadler B, Nedrud J G, Lycke N Y. Adjuvanticity of the cholera toxin A1-based gene fusion protein, CTA1-DD, is critically dependent on the ADP-ribosyltransferase and Ig-binding activity. J Immunol. 1999;162:2432–2440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhiani A A, Nilsson L-A, Ouchterlony O. Effect of cholera toxin on vaccine-induced immunity and infection in murine schistosomiasis mansoni. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4919–4924. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4919-4924.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arakawa T, Yu J, Chong D K X, Hough J, Engen P C, Langridge W H R. A plant-based cholera toxin B subunit-insulin fusion protein protects against the development of autoimmune diabetes. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:934–938. doi: 10.1038/nbt1098-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asaka M, Takeda H, Sugiyama T, Kato M. What role does Helicobacter pylori play in gastric cancer? Gastroenterology. 1997;113:S56–S60. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)80013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergerot I, Ploix C, Petersen J, Moulin V, Rask C, Fabien N, Lindblad M, Mayer A, Czerkinsky C, Holmgren J, Thivolet C. A cholera toxoid-insulin conjugate as an oral vaccine against spontaneous autoimmune diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4610–4614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanchard T G, Czinn S J, Redline R W, Sigmund N, Harriman G, Nedrud J G. Antibody-independent protective mucosal immunity to gastric helicobacter infection in mice. Cell Immunol. 1999;191:74–80. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanchard T G, Lycke N, Czinn S J, Nedrud J G. Recombinant cholera toxin B subunit is not an effective mucosal adjuvant for oral immunization of mice against Helicobacter felis. Immunology. 1998;93:22–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman P A, Swift D L. A simplified method for detecting the heat-labile enterotoxin of Escherichia coli. J Med Microbiol. 1984;18:399–403. doi: 10.1099/00222615-18-3-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen M, Lee A, Hazell S L. Immunisation against gastric Helicobacter infection in a mouse/Helicobacter felis model. Lancet. 1992;339:1120–1121. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90720-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chisari F V, Northrup R S. Pathophysiologic effects of lethal and immunoregulatory doses of cholera enterotoxin in the mouse. J Immunol. 1974;113:740–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cover T L, Blaser M J. Helicobacter pylori and gastroduodenal disease. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:135–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.43.020192.001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuatrecasas P. Gangliosides and membrane receptors for cholera toxin. Biochemistry. 1973;12:3558–3566. doi: 10.1021/bi00742a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Czerkinsky C, Russell M W, Lycke N, Lindblad M, Holmgren J. Oral administration of a streptococcal antigen coupled to cholera toxin B subunit evokes strong antibody responses in salivary glands and extramucosal tissues. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1072–1077. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1072-1077.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Czinn S J, Cai A, Nedrud J G. Protection of germ-free mice from infection by Helicobacter felis after active oral or passive IgA immunization. Vaccine. 1993;11:637–742. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90309-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Czinn S J, Nedrud J G. Oral immunization against Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2359–2363. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2359-2363.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Geus B, Dol-Bosman M, Scholten J W, Stok W, Bianchi A. A comparison of natural and recombinant cholera toxin B subunit as stimulatory factors in intranasal immunization. Vaccine. 1997;15:1110–1113. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Haan L, Feil I K, Verweij W R, Holtrop M, Hol W G, Agsteribbe E, Wilschut J. Mutational analysis of the role of ADP-ribosylation activity and GM1-binding activity in the adjuvant properties of the Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin towards intranasally administered keyhole limpet hemocyanin. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1243–1250. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199804)28:04<1243::AID-IMMU1243>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Haan L, Verweij W R, Feil I K, Holtrop M, Hol W G J, Agsteribbe E, Wilschut J. Role of GM1 binding in the mucosal immunogenicity and adjuvant activity of the Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin and its B subunit. Immunology. 1998;94:424–430. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickinson B L, Clements J D. Dissociation of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin adjuvanticity from ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1617–1623. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1617-1623.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Douce G, Fontana M, Pizza M, Rappuoli R, Dougan G. Intranasal immunogenicity and adjuvanticity of site-directed mutant derivatives of cholera toxin. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2821–2828. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2821-2828.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubois A, Lee C K, Fiala N, Kleanthous H, Mehlman P T, Monath T. Immunization against natural Helicobacter pylori infection in nonhuman primates. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4340–4346. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4340-4346.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eaton K A, Krakowka S. Chronic active gastritis due to Helicobacter pylori in immunized gnotobiotic piglets. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1580–1586. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eaton K A, Ringler S S, Krakowka S. Vaccination of gnotobiotic piglets against Helicobacter pylori. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1399–1405. doi: 10.1086/314463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elson C O, Ealding W. Generalized systemic and mucosal immunity in mice after mucosal stimulation with cholera toxin. J Immunol. 1984;132:2736–2741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ermak T H, Giannasca P J, Nichols R, Myers G A, Nedrud J, Weltzin R, Lee C K, Kleanthous H, Monath T P. Immunization of mice with urease vaccine affords protection against Helicobacter pylori infection in the absence of antibodies and is mediated by MHC class II-restricted responses. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2277–2288. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frey A, Giannasca K T, Weltzin R, Giannasca P J, Reggio H, Lencer W I, Neutra M R. Role of the glycocalyx in regulating access of microparticles to apical plasma membranes of intestinal epithelial cells: implications for microbial attachment and oral vaccine targetting. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1045–1059. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giuliani M M, Del Giudice G, Giannelli V, Dougan G, Douce G, Rappuoli R, Pizza M. Mucosal adjuvanticity and immunogenicity of LTR72, a novel mutant of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin with partial knockout of ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1123–1132. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glenn G M, Rao M, Matyas G R, Alving C R. Skin immunization made possible by cholera toxin. Nature. 1998;391:851. doi: 10.1038/36014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glenn G M, Scharton-Kersten T, Vassell R, Matyas G R, Alving C R. Transcutaneous immunization with bacterial ADP-ribosylating exotoxins as antigens and adjuvants. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1100–1106. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1100-1106.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grun J L, Maurer P H. Different T helper cell subsets elicited in mice utilizing two different adjuvant vehicles: the role of endogenous interleukin 1 in proliferative responses. Cell Immunol. 1989;121:134–145. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(89)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guidry J J, Cardenas L, Cheng E, Clements J D. Role of receptor binding in toxicity, immunogenicity, and adjuvanticity of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4943–4950. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.4943-4950.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guy B, Hessler C, Fourage S, Haensler J, Vialon-Lafay E, Rokbi B, Millet M J. Systemic immunization with urease protects mice against Helicobacter pylori infection. Vaccine. 1998;16:850–856. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hashigucci K, Ogawa H, Ishidate T, Yamashita R, Kamiya H, Watanabe K, Hattori N, Sato T, Suzuki Y, Nagamine T, Aizawa C, Tamura S, Kurata T, Oya A. Antibody responses in volunteers induced by nasal influenza vaccine combined with Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit containing a trace amount of the holotoxin. Vaccine. 1996;14:113–119. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00174-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirabayashi Y, Kurata H, Funato H, Nagamine T, Aizawa C, Tamura S, Shimada K, Kurata T. Comparison of intranasal inoculation of influenza HA vaccine combined with cholera toxin B subunit with oral or parenteral vaccination. Vaccine. 1990;8:243–248. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90053-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmgren J, Lycke N, Czerkinsky C. Cholera toxin and cholera B subunit as oral-mucosal adjuvant and antigen vector systems. Vaccine. 1993;11:1179–1184. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90039-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hornquist E, Lycke N. Cholera toxin adjuvant greatly promotes antigen priming of T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2136–2143. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kleanthous H, Myers G A, Georgakopoulos K M, Tibbitts T J, Ingrassia J W, Gray H L, Ding R, Zhang Z Z, Lei W, Nichols R, Lee C K, Ermak T H, Monath T P. Rectal and intranasal immunizations with recombinant urease induce distinct local and serum immune responses in mice and protect against Helicobacter pylori infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2879–2886. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2879-2886.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee A, Chen M. Successful immunization against gastric infection with Helicobacter species: use of a cholera toxin B-subunit-whole-cell vaccine. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3594–3597. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3594-3597.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee C K, Soike K, Hill J, Georgakopoulos K, Tibbitts T, Ingrassia J, Gray H, Boden J, Kleanthous H, Giannasca P, Ermak T, Weltzin R, Blanchard J, Monath T P. Immunization with recombinant Helicobacter pylori urease decreases colonization levels following experimental infection of rhesus monkeys. Vaccine. 1999;17:1493–1505. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00365-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee C K, Weltzin R, Thomas W D, Kleanthous H, Ermak T H, Soman G, Hill J E, Ackerman S K, Monath T P. Oral immunization with recombinant Helicobacter pylori urease induces secretory IgA antibodies and protects mice from challenge with Helicobacter felis. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:161–172. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levine M M, Kaper J B, Black R E, Clements M L. New knowledge on pathogenesis of bacterial enteric infections as applied to vaccine development. Microbiol Rev. 1983;47:510–550. doi: 10.1128/mr.47.4.510-550.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang X-P, Lamm M E, Nedrud J G. Oral administration of cholera toxin-Sendai virus conjugate potentiates gut and respiratory immunity against Sendai virus. J Immunol. 1988;141:1495–1501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lycke N, Tsuji T, Holmgren J. The adjuvant effect of Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxins is linked to their ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2277–2281. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marchetti M, Arico B, Burroni D, Figura N, Rappuoli R, Ghiara P. Development of a mouse model of Helicobacter pylori infection that mimics human disease. Science. 1995;267:1655–1658. doi: 10.1126/science.7886456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mbawuike I N, Wyde P R. Induction of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells by immunization with killed influenza virus and effect of cholera toxin B subunit. Vaccine. 1993;11:1205–1213. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGhee J R, Kiyono H. New perspectives in vaccine development: mucosal immunity to infections. Infect Agents Dis. 1993;2:55–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Michetti P, Corthesy-Theulaz I, Davin C, Haas R, Vaney A-C, Heitz M, Bille J, Kraehenbuhl J-P, Saraga E, Blum A L. Immunization of BALB/c mice against Helicobacter felis infection with Helicobacter pylori urease. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1002–1011. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michetti P, Kreiss C, Kotloff K L, Porta N, Blanco J-L, Bachmann D, Herranz M, Saldinger P F, Corthésy-Theulaz I, Losonsky G, Nichols R, Simon J, Stolte M, Ackerman S, Monath T P, Blum A L. Oral immunization with urease and Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin adjuvant is safe and immunogenic in Helicobacter pylori-infected adults. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:804–812. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Northrup R S, Fauci A S. Adjuvant effect of cholera enterotoxin on the immune response of the mouse to sheep red blood cells. J Infect Dis. 1972;125:672–673. doi: 10.1093/infdis/125.6.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pappo J, Torrey D, Castriotta L, Savinainen A, Kabok Z, Ibraghimov A. Helicobacter pylori infection in immunized mice lacking major histocompatibility complex class I and class II functions. Infect Immun. 1999;67:337–341. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.337-341.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun J B, Holmgren J, Czerkinsky C. Cholera toxin B subunit: an efficient transmucosal carrier-delivery system for induction of peripheral immunological tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10795–10799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun J B, Rask C, Olsson T, Holmgren J, Czerkinsky C. Treatment of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by feeding myelin basic protein conjugated to cholera toxin B subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7196–7201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sverremark E, Fernandez C. Immunogenicity of bacterial carbohydrates: cholera toxin modulates the immune response against dextran B512. Immunology. 1997;92:153–159. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00314.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takahashi I, Marinaro M, Kiyono H, Jackson R J, Nakagawa I, Fujihashi K, Hamada S, Clements J D, Bost K L, McGhee J R. Mechanisms for mucosal immunogenicity and adjuvancy of Escherichia coli labile enterotoxin. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:627–635. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tamura S-I, Asanuma H, Tomita T, Komase K, Kawahara K, Danbara H, Hattori N, Watanabe K, Suzuki Y, Nagamine T, Aizawa C, Oya A, Kurata T. Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin B subunits supplemented with a trace amount of the holotoxin as an adjuvant for nasal influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 1994;12:1083–1089. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tochikubo K, Isaka M, Yasuda Y, Kozuka S, Matano K, Miura Y, Taniguchi T. Recombinant cholera toxin B subunit acts as an adjuvant for the mucosal and systemic responses of mice to mucosally coadministered bovine serum albumin. Vaccine. 1998;16:150–155. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsuji T, Yokochi T, Kamiya H, Kawamoto Y, Miyama A, Asano Y. Relationship between a low toxicity of the mutant A subunit of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli enterotoxin and its strong adjuvant action. Immunology. 1997;90:176–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vadolas J, Davies J K, Wright P J, Strugnell R A. Intranasal immunization with liposomes induces strong mucosal immune responses in mice. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:969–975. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vajdy M, Kosco-Vilbois M H, Kopf M, Kohler G, Lycke N. Impaired mucosal immune responses in interleukin 4-targeted mice. J Exp Med. 1995;181:41–53. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Verweij W R, de Haan L, Holtrop M, Agsteribbe E, Brands R, van Scharrenburg G J M, Wilshut J. Mucosal immunoadjuvant activity of recombinant Escherichia coli heat-labile entertoxin and its B subunit: induction of systemic IgG and secretory IgA responses in mice by intranasal immunization with influenza virus surface antigen. Vaccine. 1998;16:2069–2076. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weltzin R, Kleanthous H, Guirakhoo F, Monath T P, Lee C K. Novel intranasal immunization techniques for antibody induction and protection of mice against gastric Helicobacter felis infection. Vaccine. 1997;15:370–376. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Williams N A, Stasiuk L M, Nashar T O, Richards C M, Lang A K, Day M J, Hirst T R. Prevention of autoimmune disease due to lymphocyte modulation by the B-subunit of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5290–5295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilson A D, Clarke C J, Stokes C R. Whole cholera toxin and B subunit act synergistically as an adjuvant for the mucosal immune response of mice to keyhole limpet haemocyanin. Scand J Immunol. 1990;31:443–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1990.tb02791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu H Y, Russell M W. Induction of mucosal and systemic immune responses by intranasal immunization using recombinant cholera toxin B subunit as an adjuvant. Vaccine. 1998;16:286–292. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu-Amano J, Kiyono H, Jackson R J, Staats H F, Fujihashi K, Burrows P D, Elson C O, Pillai S, McGhee J R. Helper T cell subsets for immunoglobulin A responses: oral immunization with tetanus toxoid and cholera toxin as adjuvant selectively induces Th2 cells in mucosa associated tissues. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1309–1320. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamamoto S, Kiyono H, Yamamoto M, Imaoka K, Yamamoto M, Fujihashi K, van Ginkel F W, Noda M, Takeda Y, McGhee J R. A nontoxic mutant of cholera toxin elicits Th2-type responses for enhanced mucosal immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5267–5272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamamoto S, Takeda Y, Yamamoto M, Kurazono H, Imaoka K, Yamamoto M, Fujihashi K, Noda M, Kiyono H, McGhee J R. Mutants in the ADP-ribosyltransferase cleft of cholera toxin lack diarrheagenicity but retain adjuvanticity. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1203–1210. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]