Abstract

We conducted a scoping review of contextual factors impeding uptake and adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis in transgender communities as an in-depth analysis of the transgender population within a previously published systematic review. Using a machine learning screening process, title and abstract screening, and full-text review, the initial systematic review identified 353 articles for analysis. These articles were peer-reviewed, implementation-related studies of PrEP in the U.S. published after 2000. Twenty-two articles were identified in this search as transgender related. An additional eleven articles were identified through citations of these twenty-two articles, resulting in thirty-three articles in the current analysis. These thirty-three articles were qualitatively coded in NVivo using adapted constructs from the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research as individual codes. Codes were thematically assessed. We point to barriers of implementing PrEP, including lack of intentional dissemination efforts and patience assistance, structural factors, including sex work, racism, and access to gender affirming health care, and lack of provider training. Finally, over 60% of articles lumped cisgender men who have sex with men with trans women. Such articles included sub-samples of transgender individuals that were not representative. We point to areas of growth for the field in this regard.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Pre-exposure prophylaxis, Transgender health, Implementation science, Determinants of implementation, Scoping review, Qualitative analysis

Resumen

En este revisión de alcance, examinamos los factores contextuales que impiden la adopción y el cumplimiento de la profilaxis previa a la exposición en las comunidades transgénero. Este revisión sistemática se formó a partir de una revisión sistemática más grande. Utilizando un proceso de selección de aprendizaje automático, filtración de los titulus y examines, y revision del texto complete, el primer revisión sistemática identificó 353 artículos por el analisis. Estes artículos fueron estudios revisados por pares, relacionados con la implementación de la PrEP en los EE.UU. publicados despues de 2000. Veintidós artículos se identificaron en esta b?squeda como relacionados con personas transgénero. Se identificaron once artículos adicionales a través de citas de estos veintidós artículos, lo que resultó en treinta y tres artículos en el análisis actual. Estos treinta y tres artículos fueron codificados cualitativamente en NVivo utilizando construcciones adaptadas del Marco Consolidado para la Investigación de Implementación (CFIR) como códigos individuales. Los códigos fueron evaluados temáticamente. Señalamos las barreras de la implementación de la PrEP, como la falta de esfuerzos intencionales de difusión y asistencia al paciente, las barreras estructurales como el trabajo sexual, el racism, y el acceso a la salud de afirmación de género, y la falta del entrenamiento de los doctores. Finalmente, más de sesenta por ciento de los artículos tuvieron submuestras de personas transgénero que no eran representativas. Se?alamos áreas de crecimiento para el campo en este sentido.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an oral pill taken once daily, or, as of 2022, a bimonthly injection, to prevent the acquisition of HIV. There are two options for oral PrEP—Truvada (emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) and Descovy (emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide)—and one option for long acting injectable (LAI) PrEP—Apretude (cabrotegravir). When taken daily or injected bimonthly, PrEP has been found to reduce likelihood of HIV acquisition by 99%, with 60% effectiveness in real world trials (Jourdain, de Gage, Desplas, & Dray-Spira, 2022; Raphael J Landovitz et al., 2021; Mayer et al., 2020).

PrEP has been found effective at reducing rates of HIV seroconversion for transgender women, transgender men, and nonbinary people (Grant et al., 2020), in addition to cisgender populations (i.e., those who identify with the sex they were assigned at birth). Provider prescription of PrEP has increased, with 25% of those indicated for PrEP use by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria (e.g. cisgender men who have sex with men [cisgender MSM], transgender women, and Black/Latinx individuals, among others) having a prescription for PrEP in 2020 compared to only about 3% in 2015 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). However, large disparities in PrEP uptake and reach exist across minoritized populations, including Black, Latinx, transgender, and/or youth populations (Kuehn, 2018; Poteat & Radix, 2020; Spinelli and Buchbinder, 2019). A recent study details that these disparities may have widened between 2015 and 2020 (Kamitani, Johnson, Wichser, Adegbite, & Mullins, 2020). The first National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System’s Transgender Cycle found 92% of HIV-negative transgender women surveyed were aware of PrEP, but only 32% reported using it (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). Recent research found that while 84.1% of transgender men who have sex with men (transgender MSM; i.e. men who were assigned female at birth and who have sex with other men) surveyed had heard of PrEP, only 28% of all participants reported using PrEP (Reisner, Moore, Asquith, Pardee, & Mayer, 2021). Implementation science enables analysis of the gap between knowledge and uptake of PrEP that can inform strategies for effectively bringing this intervention to this population with unmet need.

While myriad evidence-based innovations (EBIs; e.g., PrEP, motivational interviewing, housing first) have been identified for HIV prevention and treatment, in addition to other illnesses and infections, researchers have identified a gap, referred to as the implementation gap, of seventeen years between identification of an EBI and its translation into real-world settings (Morris, Wooding, & Grant, 2011). That is, if the EBI is ever implemented in real-world settings at all. Implementation science is the study of how to increase uptake of EBIs (referred to as “innovations”), promote adherence and/or sustainment, and, thus, improve quality and effectiveness (Bauer, Damschroder, Hagedorn, Smith, & Kilbourne, 2015). The U.S. plan to end the HIV epidemic requires speedy translation of findings into practice, ensuring that the right innovations are utilized to their greatest effect by highly vulnerable populations (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2022). Implementation science examines what changes are needed in policy, practice, procedure, or behavior to actualize that goal in real time. Researchers know that PrEP is efficacious and effective and have identified disparities in uptake and adherence. Implementation science takes the reigns from there to identify how to then overcome barriers leading to disparities.

Within implementation science, barriers, as well as facilitators, to implementing, adapting, modifying, and/or improving innovations are referred to as determinants of implementation; that is, they enable and/or hinder adoption, acceptability, and reach of an innovation, among other outcomes (Wensing et al., 2011). A predominant framework for conceptualizing determinants is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). CFIR has five domains, or categories of determinants, each broken down by sub-constructs (Damschroder et al., 2009). CFIR domains include: innovation characteristics (e.g. innovation source, evidence), inner setting (i.e. factors of implementation internal to an organization—may be identified by studies in delivery settings but may also include perceptions of patients), outer setting (i.e. sociopolitical, structural, and environmental factors), characteristics of individuals (including providers and patients), and process determinants (e.g. how engaging patients in implementation may shape the outcome of delivery or uptake).

Building on a larger systematic review (Li et al., 2022) of determinants of PrEP implementation for all populations, this manuscript focuses on transgender populations. While the larger review provides breadth, this manuscript contributes depth by focusing on a specific population and qualitatively exploring how factors hinder and enable implementation, how researchers identify determinants, and how specific constructs are experienced by transgender people and those that provide care for them. However, most articles included focus on transgender women, with few including transgender men and/or nonbinary people. While we included four studies that explicitly examined determinants of PrEP implementation for transgender men and one that did so for nonbinary transfeminine individuals, given the scope of the literature that we review, this manuscript is more centrally focused on determinants of implementation for transgender women, except when explicitly detailed otherwise. In this review, we ask:

What barriers and facilitators have been identified as determinants of PrEP implementation for transgender populations, and how are these barriers and facilitators experienced by transgender people?

What existing gaps in the literature on potential barriers and facilitators need greater analysis?

How do study designs, samples, and methods hinder or enable identification of determinants of PrEP implementation for transgender populations?

Methods

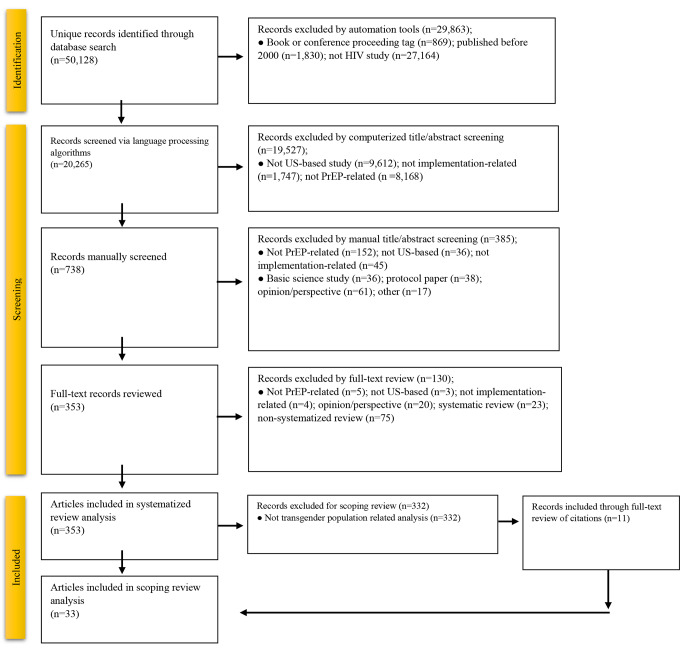

The authors conducted this scoping review as an in-depth, qualitative analysis of the transgender population within a previously published systematic review of PrEP for all populations (Li et al., 2022). Between November 2020 and January 2022, our team conducted a database search of studies related to implementation of PrEP. The full protocol of the initial systematic review has been described elsewhere (Li et al., 2022). Through a multi-step, computerized, and manual-screening process, 50,128 unique records were identified through a database search of Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. The number of unique records was then reduced through deduplication, title and abstract screening, and full-text review (see Fig. 1 for the PRISMA-ScR and full details of exclusion by number). The initial systematic review included 353 articles for analysis.

Authors of the initial systematic review coded studies using CFIR constructs as codes (Damschroder et al., 2009), as well as by common implementation settings (e.g., HIV/AIDS health centers, LGBT health centers, pharmacies) and priority populations (e.g., Latinx communities, transgender communities). The first author (az) conducted full-text review of each of the twenty-three articles coded through this process as “transgender population” and found that one article simply mentioned transgender populations but did not include them in their study or analysis. This article was excluded, reducing the number of articles to twenty-two. An additional eleven articles were identified from the citations of these twenty-two articles as potentially relevant to this scoping review. These eleven articles were not identified in the initial review, as many were published after the initial computerized search or were published in more niche journals that were not uploaded that our initial search did not identify. After screening, these eleven articles were included into the scoping review, resulting in a total of 33 articles. These thirty-three articles were uploaded to NVivo (Version 1.6.1) and qualitatively coded using adapted CFIR constructs (Damschroder et al., 2009; Li et al., 2022) as individual codes. Additional codes included study methods; purpose of the study; whether analyses and results lumped transgender women and cisgender MSM and/or lumped transgender men and cisgender women (i.e., women assigned female at birth); and whether multi-population analyses had large enough transgender sub-populations for substantive analysis.

We added two additional codes as outer setting barriers, “cissexism” and “racism,” and used these two sociopolitical concepts as codes. Segments coded as cissexism and/or racism included findings from studies that demonstrated the presence of interpersonal, institutional, and/or systemic discrimination, and oppression that shaped the health outcomes and experiences of transgender patients and/or patients of color. This coding scheme was intentionally chosen in order to more explicitly attend to health inequities experienced by Black transgender women and other transgender populations as structural and systemic (Shelton, Adsul, & Oh, 2021).

Codes were thematically assessed by the first author (az), examining not only the prevalence of analysis of determinants but also how determinants were measured, what authors found, and how they analyzed the data. Axial coding was also performed to examine differences across year of publication, intersecting population(s), and types of method(s) used by researchers. Analysis of the codes “cissexism” and “racism” occurred intersectionally, with an attentiveness to the ways in which the two sociopolitical forces differentially shape health and implementation outcomes. We used intersectional theory (Bowleg, 2012; Crenshaw 2018) to elucidate the interlocking nature of various axes of power (e.g. race, gender, sexual orientation, etc.).

We conducted a search for existing reviews of determinants of PrEP implementation in transgender populations. We did not identify any existing published reviews of PrEP implementation that focused on transgender populations; however, we identified several ongoing reviews by Matos et al. (PROSPERO ID: CRD42021239360), Peixoto et al. (PROSPERO ID: CRD42020154059), Canoy, Hannes, and Thapa (PROSPERO ID: CRD42018089956), Algarin et al. (PROSPERO ID: CRD42019130858) and Garcia, Rehman, and Mbuagbaw (PROSPERO ID: CRD42022300631). These reviews examine factors associated with PrEP in transgender populations. Our scoping review differs, in that, we sought to qualitatively explore factors leading to and/or hindering implementation of PrEP solely for transgender people. Further, our review goes beyond identifying determinants of implementation and analyzes how determinants are hindering and/or enabling uptake and adherence. To the best of our knowledge, no published or registered ongoing review examines determinants of PrEP implementation along the PrEP cascade for transgender people of all genders and races, as a group separate from cisgender people, using implementation science frameworks.

Results

Delivery Setting

Four studies examined determinants of PrEP implementation in non-specialty primary care (Brooks et al. 2019; Chan et al. 2019; Rhodes et al. 2020; Wu et al. 2020), one in pharmacies (Havens et al., 2019), and five in multiple settings (Carter et al. Jr 2022; Cohen et al. 2015; Hoenigl et al., 2019; Rael et al. 2018; Sevelius, Keatley, Calma, & Arnold, 2016). The remaining twenty-three studies examined determinants broadly, without attention to specific delivery settings. The single study focused on PrEP delivery in pharmacies examined the acceptability and feasibility of implementing PrEP in pharmacies and identified determinants in CFIR’s inner and outer settings and characteristics of individuals domains (Havens et al., 2019). This study described delays in communication between pharmacists and medical providers and pharmacist discomfort with discussing sexual histories as barriers to PrEP delivery that could be enhanced to facilitate better delivery in the future. Studies examining delivery in non-specialty primary care or multiple settings identified determinants in each of the CFIR domains but with little attention to process determinants.

Study Methods

There was little variation in identification of barriers and facilitators across study methods (see Table 1). Most articles utilized either qualitative methods or quantitative methods, with only three utilizing a mixed-methods approach (Rael et al. 2018; Theodore et al. 2020; Zarwell et al., 2021). Across study methods, outer setting determinants, characteristics of individuals (patients), and innovation characteristics were the most analyzed CFIR domains. However, qualitative articles were more likely to identify process determinants than quantitative or mixed-methods articles (n = 5, 2, & 0 respectively). Qualitative articles identified the facilitative role that engaging with consumers/patients plays in implementing PrEP in transgender communities (Brooks et al. 2019; Carter et al. Jr 2022; Galindo et al. 2012; Klein and Golub 2019; Reback et al. 2019).

Table 1.

Number of measured determinants by CFIR 2.0 construct and study method among n = 33 articles

| CFIR 2.0 Domain | Qualitative Articles | Quantitative Articles | Mixed Methods Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation Characteristics | 7 | 6 | 2 |

| Outer Setting | 9 | 9 | 1 |

| Inner Setting | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Characteristics of Individuals | 9 | 8 | 2 |

| Process | 5 | 2 | 0 |

Years of Publication

Over 72% (n = 24) of articles were published between 2018 and 2022. One article was identified from 2012 (Galindo et al. 2012), one from 2013 (Golub et al. 2013), one from 2015 (Cohen et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2016), one from 2016 (Liu et al. 2016), three from 2017 (Eaton et al. 2017; Landovitz et al. 2017; Wood et al. 2017), and two from 2018 (Lalley-Chareczko et al. 2018; Rael et al. 2018). The single article from 2012 examined barriers and facilitators that we coded in each of the five CFIR domains through focus groups with transgender women (Galindo et al. 2012). Of the nine articles prior to 2018, only one focused on barriers and facilitators of PrEP implementation specifically for transgender communities (Sevelius, Keatley, et al., 2016). The other seven each categorized transgender women with cisgender MSM in their study design and focused on cisgender MSM more so than their smaller sub-samples of transgender women. Articles published 2018 and after largely identified barriers in the outer setting, barriers and facilitators vis-à-vis characteristics of individuals, and barriers regarding innovation characteristics.

Study Priority Populations

Twenty of the thirty-three articles (60.6%) examined transgender women and cisgender MSM together. Only nine (27.3%) attended to determinants for Black transgender communities, and eight (24.2%) identified determinants for Latinx transgender communities. Only three identified determinants for transgender people who use injectable drugs (PWID) (Chan et al. 2019; Havens et al., 2019; Wu et al. 2020). While there was little variation in determinants identified across priority populations, articles that included transgender PWIDs in their studies largely examined outer setting determinants, with none identifying process or innovation characteristic determinants.

Innovation Characteristics

Fifteen articles (45.5%) measured and identified determinants regarding innovation characteristics (see Table 2). Another five mentioned determinants identified by other scholars, for example, noting identified disparities and issues of medical mistrust when introducing the study, but these articles did not study innovation characteristics as determinants of implementation within their own research. Innovation characteristics refer to core and adaptable pieces of an innovation (Damschroder et al., 2009). Study authors utilized focus group, interview, and/or survey data to assess patients’ and—to a lesser extent—providers’ perceptions of PrEP’s complexity, and cost. Four articles identified “acceptable” and “unacceptable” side effects of PrEP: using semi-structured interviews with six transgender women, Galindo et al. (2012) highlighted that participants deemed mild (e.g., headaches, nausea) and/or short-term side effects as acceptable and long-term and more serious side-effects (e.g., bone damage) as unacceptable. However, Rael et al. (2018) found that participants from four focus groups (n = 18 participants) were more seriously concerned about stomach pain and nausea than Galindo et al.’s sample. Rael et al. (2020; 2021) were also the only study authors to focus on determinants of injectable PrEP implementation; using focus group data with a sample of eighteen in 2020 and interviews with a sample of fifteen in 2021, they found participant concerns lay in where the injection occurs. Participants felt that the gluteal muscle was unacceptable due to fears of disfiguration or scarring in the area, as well as potential incompatibility of gluteal injections due to prior or future silicone injections. However, these same participants displayed excitement at the idea of injectable PrEP and felt that it was more compatible with their routine injections of estradiol than oral PrEP.

Table 2.

Number and proportion of articles measuring v. mentioning determinants by CFIR 2.0 construct among n = 33 articles

| CFIR 2.0 Domain & Construct | Mentioning | Proportion of Articles Only Mentioning (%) | Measuring | Proportion of Articles Measuring (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation Characteristics | Innovation source | 4 | 12.1 | 12 | 36.4 |

| Evidence strength & quality | 7 | 21.2 | 7 | 21.2 | |

| Relative advantage | 2 | 6.1 | 1 | 3.0 | |

| Adaptability | 1 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Trialability | 0 | 3.0 | 1 | 3.0 | |

| Complexity | 4 | 12.1 | 8 | 24.2 | |

| Design quality and packaging | 6 | 18.2 | 7 | 21.2 | |

| Cost | 1 | 3.0 | 8 | 24.2 | |

| Other intervention characteristic | 2 | 6.1 | 8 | 24.2 | |

| Subtotal | 5 | 15.2 | 15 | 45.5 | |

| Outer Setting | Mass disruptions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Population needs & resources | 12 | 36.4 | 11 | 33.3 | |

| Community characteristics | 7 | 21.2 | 16 | 48.5 | |

| Partnerships & connections | 2 | 6.1 | 2 | 6.1 | |

| Market forces | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| External policy & incentives | 2 | 6.1 | 3 | 9.1 | |

| Other outer setting characteristic | 1 | 3.0 | 1 | 3.0 | |

| Subtotal | 8 | 24.2 | 19 | 57.6 | |

| Inner Setting | Structural characteristics | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Networks & communications | 0 | 0 | 3 | 9.1 | |

| Culture/climate | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6.1 | |

| Tension for change | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Compatibility | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.0 | |

| Relative priority | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Organizational incentives & rewards | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Goals & feedback | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Leadership engagement | 1 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Available resources | 1 | 3.0 | 3 | 9.1 | |

| Access to knowledge and information | 0 | 0 | 3 | 9.1 | |

| Other inner setting characteristic | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.0 | |

| Subtotal | 2 | 6.1 | 5 | 15.2 | |

| Characteristics of Individuals—Patients | Knowledge & beliefs about the intervention | 7 | 21.2 | 10 | 30.3 |

| Self-efficacy | 0 | 0 | 8 | 24.2 | |

| Individual stage of change | 0 | 0 | 5 | 15.2 | |

| Individual identification with organization | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other personal attributes | 2 | 6.1 | 10 | 30.3 | |

| Other individual characteristic | 2 | 6.1 | 17 | 51.5 | |

| Subtotal | 3 | 9.1 | 19 | 57.6 | |

| Characteristics of Individuals–Providers | Knowledge & beliefs about the intervention | 0 | 0 | 3 | 9.1 |

| Self-efficacy | 1 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Individual stage of change | 1 | 3.0 | 1 | 3.0 | |

| Individual identification with organization | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other personal attributes | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.0 | |

| Other individual characteristic | 0 | 0 | 6 | 18.2 | |

| Subtotal | 1 | 3.0 | 7 | 21.2 | |

| Process | Planning | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Engaging | 1 | 3.0 | 6 | 18.2 | |

| Executing | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6.1 | |

| Reflecting & evaluating | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other process | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.0 | |

| Subtotal | 1 | 3.0 | 7 | 21.2 | |

As a CFIR construct, complexity refers to the perceived difficulty of an intervention (Greenhalgh et al. 2004). Studies that attended to the complexity of PrEP described a recurring question of whether a daily pill is acceptable to transgender patients. While articles noted that the use of a daily pill could be integrated into other pill regimens (including hormone replacement therapy [HRT]), they also note that there are many reasons that may be undesirable for transgender people. For example, Rael et al. (2018) described three patient concerns regarding oral PrEP. Patients worried about the size of PrEP and difficulty of swallowing larger pills, as well as a lack of desire to add another daily pill to an already complex hormone regimen that may include taking estradiol in the morning and/or evening along with one or two androgen blockers and, perhaps, progesterone. Further, participants explained that patients who are homeless, impoverished, or otherwise socioeconomically marginalized may have higher priorities than remembering to take PrEP each day. Finally, the addition of recurring visits for lab tests can be cumbersome for some transgender individuals who are unable to fit another doctor appointment into their routine, particularly for those in rural areas who must travel to access gender-affirming care, let alone PrEP-care. While injectable or long-acting PrEP, including Apretude (cabotegravir), may solve the problem regarding pill size and daily use, Rael et al. found that “overwhelmingly, participants felt that visits with their healthcare provider to administer injectable PrEP were cumbersome and inconvenient” (2020, p. 1455).

Eight articles identified participant concerns regarding the costs of PrEP. A lack of knowledge of PrEP among patients across studies also resulted in a lack of awareness that there are payment assistance programs, including that of Gilead, the manufacturer of both Truvada and Descovy. Further, Klein and Golub (2019) detailed participants’ desires for “active assistance” vis-à-vis cost support. Klein and Golub conceptualized “active assistance” as “navigation services that include help with obtaining/maintaining insurance and other payment options” (2019, p. 266) through patient navigation and by facilitating systemic change in cost and access to PrEP. Interestingly, Rael et al.’s (2018) participants were the sole sample to not identify cost as a significant barrier to PrEP. The authors utilized focus groups with eighteen participants, and nearly the entire sample had prior knowledge of PrEP. Instead of concerns with cost, they were more concerned with pill side effects (long-term and short-term) and pill size. However, this may be in part due to the location of the study, with participants solely from New York City, where, as Rael et al. mention, “the Department of Health, public health clinics, and other community-based organizations proactively outreach to city residents to enroll qualifying individuals in healthcare plans, including Medicaid” (2018, p. 12). Study authors also noted patient desires for stronger evidence regarding the efficacy of PrEP for transgender women, as well as transgender people as a whole. Additionally, study authors noted a need for studies of potential cross-interactions between HRT and PrEP. This note came from studies of transgender women participants, thus only focusing on patient concerns of cross-interactions of estradiol and PrEP but not testosterone HRT.

Regarding the innovation source, or who/what organization is promoting the innovation, twelve articles utilized focus group and interview data to identify a lack of trust in medical providers and researchers by transgender participants, and two articles found similar results through quantitative analyses. For example, 16.7% of Restar et al.’s (2018) sample (n = 230 participants) cited mistrust with providers and researchers as reasons for not wanting to take PrEP. Regression analysis detailed that access to trans-affirming providers significantly increased acceptability of PrEP amongst transgender participants.

Finally, seven articles (21.2%) examined design quality and packaging of PrEP, including marketing, as a determinant of implementation in transgender communities. Such articles highlighted findings from qualitative research that the marketing for PrEP has resulted in transgender women feeling as though PrEP is not for them. This is due to an overwhelming marketing of PrEP towards cisgender MSM in advertisements and by providers. A transfeminine participant from Klein et al.’s (2019) focus group research described an experience of a provider handing them a flyer for PrEP. The flyer asked if the reader of the flyer was a cisgender MSM and/or a transgender woman. This direct lumping of cisgender MSM and transgender women resulted in the participant declining PrEP. Indeed, 90% of Klein et al.’s sample (n = 30 participants) felt that poor uptake of PrEP among transgender populations is due to poor marketing. Participants across studies also felt that even when marketing focuses on transgender women, the models/actresses “pass” as cisgender, or in other words are not “noticeably” transgender, and that such marketing often does not include transgender women of all body sizes, transgender women who engage in survival sex work, non-monogamous transgender women, and/or other diverse representations of transgender women. Thus, participants desired marketing that addresses transgender patients’ fears regarding cross-interactions between HRT and PrEP, as well as cost assistance program information. Sevelius et al. (2016), for example, detailed that empowering, gender-affirming, and sex-positive marketing can serve to facilitate uptake and acceptability of PrEP for transgender populations .

Outer Setting

Nearly all articles (n = 27; 81.8%) mentioned determinants of PrEP implementation in the outer setting for transgender communities and patients. Fewer articles (n = 19; 57.6%) measured determinants in the outer setting. No article examined market forces (e.g., pressure to be competitive by providing additional or unique services/programming) or mass disruptions (e.g., inability to manufacture or transport PrEP due to local, state, or national emergencies). Only a small number looked at the role of external policy and incentives or partnerships and connections as barriers and/or facilitators (n = 5 and n = 4 respectively). Eleven articles (33.3%) identified disparities in prevalence as determinants of implementation. All twenty-three noted that transgender women have a higher risk of HIV infection compared to cisgender women, with higher lifetime risks of HIV acquisition for Black and/or Latina transgender women than for white transgender women, transgender women engaged in sex work, and transgender women who inject drugs. These articles highlighted structural factors, such as incarceration, homelessness, and poverty, are barriers to preventing HIV acquisition and increasing PrEP uptake. However, some also found that, when presented with information about PrEP and disparities in HIV rates and PrEP uptake, transgender women were more likely to desire PrEP and were upset that they did not previously know about PrEP. For example, transgender women sex workers identified support to initiate PrEP from other transgender women engaged in sex work (Brooks et al. 2019; Sevelius, Keatley, et al., 2016). In these cases, PrEP was viewed as a mechanism to protect themselves and their clientele. Wilson et al. (2019) additionally elucidated that transgender women’s HIV acquisition rates are different and more varied than cisgender MSM, noting that the repetitive grouping of transgender women and cisgender MSM in PrEP-related implementation research may be preventing more robust analysis and more accurate PrEP guidelines and specific supports for transgender women.

Sixteen articles (48.5%) also identified community characteristics as barriers in PrEP implementation. Community characteristics include social determinants of health (SDOH), the built environment, and discrimination. These included disparities in homelessness, poverty, incarceration, engaging in survival sex work, unemployment, and intimate partner violence, as well as a lack of access to gender-affirming health care, health insurance, and familial support, and lower rates of educational attainment. Articles detailed that these disparities are informed by experiences of discrimination, as well as structural level factors (e.g., policy), and as such, we coded many of these disparities as part of a larger structure of cissexism and racism. Brooks et al. (2019), for example, discussed the intersecting roles of cissexism and racism for Black and Latina transgender women who reported many incidents of cisgender women of color’s viewing all Black and Latina transgender women as HIV-positive, vectors of HIV, and “whores” who take no health precautions. The interview participants of Brooks et al. explained that when cisgender women see their PrEP, they use it as further evidence that Black and Latina transgender women are HIV-positive and are keeping it secret from others.

Mehrota et al. (2018) surveyed individuals who participated in the original iPrex trials that found PrEP to be efficacious. They found a significant relationship between social integration and PrEP uptake; thus, the greater connection to an LGBT community, the greater probability that an individual (i.e., cisgender MSM or transgender woman) would be likely to initiate and maintain PrEP use. Access to LGBT community, though, is not universal across the US, and Latina transgender women reported to Rhodes et al. (2020) that their migration to the US came with disappointment, as they expected greater social acceptance. Spaces created to provide services for women—often targeting cisgender women—were identified as spaces that are not yet trans-inclusive enough to enhance transgender women’s health care access. Further, the presence of LGBT and trans-inclusive agencies/organizations does not guarantee that transgender individuals are able to access such spaces. Due to fears of deportation and criminalization, undocumented transgender women, transgender women engaged in sex work, and transgender women who use drugs and/or street hormones may avoid even inclusive agencies.

Using baseline survey data from a behavioral intervention for transgender women, Restar et al. (2018) found, in part, that creating partnerships between PrEP prescribers and gender-affirming care serves a facilitative role to PrEP uptake. Finally, Klein and Golub’s (2019) transgender women and nonbinary interview participants reported frustration with researchers and implementers who continue to group transgender women and nonbinary individuals with cisgender MSM, with such grouping serving as a barrier to PrEP uptake.

Inner Setting

Only five articles (15.2%) identified inner setting determinants of PrEP implementation. The studies that identified inner setting determinants utilized qualitative methods—primarily in-depth interviews and focus groups—and only noted the inner setting briefly. Instead, the focus was often on outer setting determinants or characteristics of individuals, and inner setting determinants were mentioned as a small portion of the article.

Four articles elucidated the facilitative role of available resources, noting that staff capacity building, technical assistance, agency capacity to provide transportation to patients, and the ability to integrate gender-affirming care into PrEP services or vice versa may each increase PrEP uptake among transgender patients (Carter et al. Jr 2022; McMahan et al. 2020; Sevelius, Keatley, et al., 2016). Article authors also point to the importance of leadership buy-in for the development of an equity-centered culture within organizations to facilitate patient-centered approaches to care. For example, Carter et al. (2022) evaluated three health departments funded by a CDC health equity cluster grant. Using mixed methods from the three health departments’ projects, the authors cited a need for CBO staff to have access to ongoing training that provides information and skills needed to provide PrEP to transgender patients.

Characteristics of Individuals

Twenty articles (60.6%) identified individual-level patient and provider barriers and facilitators, with more attention to patient determinants (n = 19; 67.6% of all articles) than provider (n = 7; 21.2% of all articles). At the provider-level, study authors detailed participant reports of their providers’ telling them to not disclose PrEP use to others. While these providers encouraged their patients to keep their PrEP use a secret to mitigate stigma, interview participants felt it made them more cognizant of the stigma placed on transgender women’s use of PrEP. Other interview participants wished that their providers would grow in comfort and capacity to navigate discussions of sexual assault, sex work, and other experiences transgender women experience at a disproportionate rate. Finally, Sevelius, Keatley, Calma, and Arnold (2016) argued from interviews with transgender women that “providers and clinics that serve MSM are not necessarily equipped to recruit, retain, and provide care to transgender women” (2016, p. 1073). They explained that providers and implementers often expect that they can map cisgender MSM interventions, strategies, and guidelines onto transgender women due to a shared sex assignment at birth, but unique barriers, needs, and lived experiences of transgender women require providers and clinicians to expand their knowledge and toolsets.

At the patient-level, the largest barrier noted was a lack of knowledge and awareness about PrEP. Additionally, though transgender individuals may have had knowledge of PrEP, they did not always believe that it was a necessary intervention for them. This, in part, was due to the marketing of PrEP to cisgender MSM, resulting in transgender women feeling that PrEP is only for cisgender MSM. This was also due to perceptions that an individual needs to be engaging in a high rate of unprotected sex to be PrEP indicated.

Articles also identified barriers in self-efficacy. For example, McMahan et al. (2020) found that transgender women who used methamphetamine sought daily reminders to take their PrEP as their drug use made it difficult to remember. Brooks et al. (2019) conducted focus groups with Black and Latina transgender women and found low self-efficacy vis-à-vis condom use because of interrelationship power dynamics that made it difficult for Black and Latina transgender women to negotiate the use of a condom. Their participants reported fears of even lower confidence in ability to demand condom usage if their partners knew they were on PrEP. Many participants across studies did not feel confident in their ability, or desire, to take a pill every day, and some did not want to have to start with oral PrEP to access injectable PrEP (Rael et al. 2020), a step that was required in injectable PrEP efficacy trials.

Additional barriers lay in Black and Latina transgender women’s high rates of mental illness, making daily adherence to oral PrEP difficult; lower educational attainment, which limits health literacy; and prioritization of hormone replacement therapy. One barrier arose for those who were on HRT: HRT can require numerous appointments for doctor check-ups and routine blood work, and transgender women on HRT did not feel they had the time or capacity to have to add on additional frequent appointments for PrEP (Sevelius, Keatley, et al., 2016). Lastly, Brooks et al. (2019) detailed experiences of “anticipated stigma” for heterosexual, transgender women. One transgender Latina participant explained to researchers:

Most of the sexual partners that I have sex with are heterosexual men. So…when you tell them PrEP, they’re like, ‘‘What’s that?’’ And then I don’t want to go explain…because then they’re going to start thinking, “Oh, you’re HIV-positive.” (p. 192)

A lack of in PrEP (and general HIV) awareness by cisgender, heterosexual men can make such conversations difficult for transgender, heterosexual women.

Facilitators for PrEP initiation and maintenance included gender affirmation, with transgender women who had socially or medically transitioned being more likely to engage in protective behaviors including PrEP use; familial and peer acceptance of their identity; and engagement in sex work. Transgender women who engaged in sex work experienced encouragement and celebration from fellow sex workers for initiating PrEP. Further, transgender women engaging in sex work felt that PrEP offered them the possibility of gaining some control over their bodies that they often do not have otherwise due to pressure from clients to forgo condoms and higher pay for not using condoms. Similarly, transgender women in relationships also felt that PrEP offered them a way to protect themselves, as they may feel powerless to negotiate condom use or bring up sexual histories when their dating pool is already constrained. Rael et al. (2021) identified self-efficacy in self-injections of PrEP as a source of empowerment; thus, patients being able to inject Apretude themselves rather than having to visit their provider may facilitate PrEP uptake. Transgender women who lacked familial support but hoped for it in the future felt that PrEP offered them a way to survive and remain “healthy” for when their family comes around. Finally, while not a facilitator of PrEP use for transgender women, one article identified transgender women’s use of PrEP as a potential facilitator of uptake by cisgender, heterosexual men who could gain greater awareness of PrEP’s utility and efficacy through their transgender women partners.

Process

Only seven articles (21.2%) identified process determinants. The most noted (50% of coded “process” references) were regarding engaging patients and customers. Six out of seven articles identified facilitators to increase PrEP uptake by engaging patients through numerous methods. Carter et al. (2022) found that one health department’s use of patient storytelling of experiences of cissexism and racism increased staff empathy and served to potentially reduce medical mistrust. They also found that another health department’s engagement in a workshop, Undoing Racism, enhanced staff motivation to work with patients to overcome barriers to PrEP implementation. Galindo et al. (2012) noted the role of community mobilization strategies in increasing PrEP uptake by engaging with consumers more broadly and working with the community to create buy-in. In large, Carter et al. (2022), Galindo et al. (2012), and other articles that identified similar determinants explicated a need to engage with transgender communities, actively listen to transgender patients, and learn from transgender people. Transgender participants in numerous studies provided feedback on marketing to aid researchers in better reaching transgender communities, and transgender communities may be able to provide feedback and assistance on PrEP implementation in other regards.

Rhodes et al. (2020) analyzed the implementation of HOLA, an implementation strategy to increase PrEP uptake and other sexual health practices, among transgender Latinas. HOLA relied on the development of formally appointed implementation leaders and identification of key stakeholders to provide peer navigation assistance to transgender Latinas. Finally, Brooks et al. (2019) noted a need to adapt PrEP implementation for Black and Latina transgender women through interviews with medical providers. They highlighted that providers need to adapt strategies to the unique needs of Black and Latina transgender women and that “supportive services [specific to them] should be embedded within the delivery of PrEP to [Black and Latina transgender women]” (p. 194). Such supportive services specific to Black and Latina transgender women might include tapping into the familial and peer networks of Black and Latina transgender women that, when supportive of their gender identity, have been found to enhance PrEP uptake and levels of resilience and protective factors (Brooks et al. 2019).

Lumping Cisgender MSM & Transgender Women and Cisgender Women & Transgender Men

Twenty-one articles (63.6%) identified determinants from studies that either analyzed cisgender MSM and transgender women together (often referring to this lumped category of populations as MSMTW) or cisgender women and transgender men together. Ten articles (30.3%) focused solely on transgender people. Three of these (Rael et al. 2018, 2020, 2021) were from the same primary author, and only one (3% of all articles) included transgender men (Zarwell et al., 2021). The majority of articles lumping cisgender MSM and transgender women together did not detail that the MSM included are cisgender. Rather, this was deduced from acknowledgment within study methods that all participants had to be assigned male at birth and were either cisgender MSM or transgender women. Often, studies that included cisgender men and women and transgender men and women combined transgender men and transgender women as “transgender people” due to the small sample size of transgender people compared to the much larger sample size of cisgender people. For example, Wu et al. (2020) included a sample of 412 participants, only 20 of whom were transgender. Results were not broken out between sub-samples, except for one regression comparing “low-level PrEP retention” by gender and sexual orientation. There were not significant findings regarding the transgender sub-sample, though, most likely due to the sample size. Only one study explicitly sought to analyze determinants of PrEP implementation among transgender women and nonbinary people (Klein and Golub 2019). While three articles explicitly attended to determinants for transgender men (Theodore et al., 2020; Westmoreland et al., 2020; Zarwell et al., 2021) one of these three lumped together cisgender women with transgender men, briefly mentioning that transgender men are rarely included in studies of PrEP implementation before continuing to largely focus on cisgender women (Theodore et al., 2020).

More quantitative articles lumped cisgender MSM and transgender women than did qualitative articles (thirteen and seven, respectively; see Table 3). This lumping of cisgender MSM and transgender women made it difficult to tease apart the results of each study that pertain to transgender women and whether such studies are representative of transgender women. This is, in part, due to the small sub-samples of transgender women that were ultimately overwhelmed by much larger sub-samples of cisgender MSM. For example, Chan et al. (2019) included two transgender women in a sample of 282 participants, the rest of whom were cisgender MSM. While the study identified numerous barriers to PrEP retention and uptake among cisgender MSM, it did not do so, nor could it, for transgender women. Cohen et al. (2015) included fourteen transgender women in a sample of 1,069 participants. While articles like ones by Colson et al. (2020) found associations between education, depression, and time in follow-up and PrEP adherence—and this seems plausible to be true for transgender women, as well—it cannot be known due to only ten transgender women being included in a study of 204 total participants, all of whom else were cisgender MSM .

Table 3.

Number of articles lumping cisgender MSM and transgender women and cisgender women and transgender men, as well as number of articles that had too few transgender participants for sub-population analysis by study method of n = 21 articles

| Axial Code | Qualitative Articles | Quantitative Articles | Mixed-Method Article |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lumping cisgender MSM and transgender women | 7 | 13 | 0 |

| Lumping cisgender women and transgender men | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Too Few Transgender Participants to Break Out Results2 | 2 | 10 | 0 |

1 Less than 10% of the total sample.

Havens et al. (2019), one of the few to include transgender men, had a total sample of sixty, which included two transgender men. They noted, though, that the majority, 91.7% (55 out of 60) were men. Another three were cisgender women, and transgender men were not included in their categorization of “men.” Due to the small sample size of transgender people, article titles and abstracts often mentioned transgender women, transgender people, and, sometimes, transgender men, only for the small handful of transgender participants included to be referenced in the literature review and then again at the end of the study as a limitation. Further, Rael et al. noted in their article that, at the time, “We found that with the exception of one study, all research on [transgender women and oral PrEP] grouped transgender women with gay and bisexual men” (2018, p. 2).

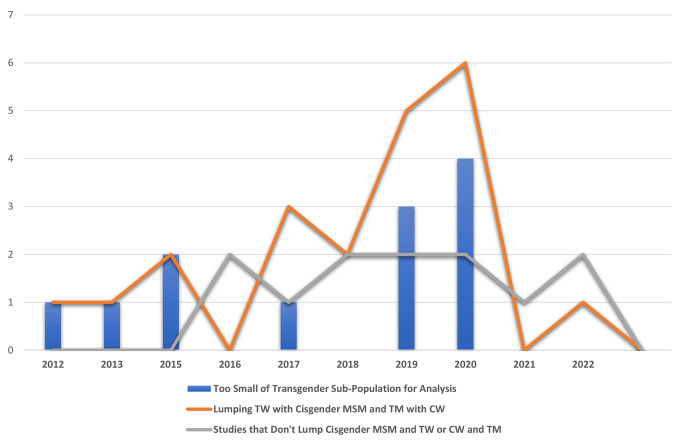

As seen in Fig. 2, there is an association between the lumping of cisgender MSM and transgender women and a lack of a large enough transgender sub-sample to breakout the results. Thus, including cisgender MSM and transgender women in a single study may not serve to identify determinants of PrEP implementation for transgender women. Finally, more studies lumping cisgender MSM and transgender women and cisgender women and transgender men have been published in the past four years than the earlier four-year period of 2012–2016 (see Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Number of articles lumping cisgender MSM and transgender women and cisgender women and transgender men, as well as number of articles with unsubstantiated findings for transgender sub-samples by year of n = 33 articles. (1TW refers to transgender women, CW refers to cisgender women, and TM refers to transgender men. 2 Less than 10% of the total sample.)

Table 4.

Number of articles lumping cisgender MSM and transgender women and cisgender women and transgender men, as well as number of articles with unsubstantiated findings for transgender sub-samples by year of n = 21 articles

| Axial Code | 2012 | 2013 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumping cisgender MSM and transgender women | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 20 |

| Lumping cisgender women and transgender men | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Too Few Transgender Participants to Break Out Results1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

1 Less than 10% of the total sample.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA-ScR flowchart for PrEP implementation in transgender populations

Discussion

While more studies lumping cisgender MSM and transgender women, as well as those lumping cisgender women and transgender men, have been published in recent years, this may in part be due to an increase in attention to transgender health within the field of HIV research in the U.S. (Siskind et al., 2016; Wansom, Guadamuz, & Vasan, 2016). In part, the increase in trans-focused studies after 2018 may have been influenced by coinciding institutional factors. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) officially formed the Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office in 2015, the CDC expanded their National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System to focus on transgender women as a distinct population for the first time in 2019, and NIH released its first R01 focused on sex and gender with particular attention to transgender populations in the Fall of 2020.

Though insufficient, the growth in this area of research has provided formative knowledge regarding determinants of PrEP implementation for transgender individuals. The findings point to barriers to overcome for expanding PrEP implementation in transgender communities and facilitators that can be utilized to do so. Such barriers include a need to actively and intentionally expand awareness of PrEP availability, side effects, safety to take with HRT, and cost assistance programs. Additionally, whatever form education and awareness-building take, transgender individuals should be engaged in the development of these. Further, marketing of PrEP at large needs to better engage transgender individuals in the design process. In doing so, PrEP marketing can better target the needs and experiences of transgender people. Additionally, scholars highlight structural factors impeding transgender individuals’ access to PrEP uptake and, especially, adherence. These include engagement in sex work, histories of incarceration, access to gender affirming health care and health insurance, educational attainment, and systemic racism. Structural barriers will require structural strategies. System-level barriers include the need for providers to increase their awareness and knowledge of transgender experiences and transgender health needs, as well as for non-HIV-specific primary care providers and pharmacists to obtain training and resources to prescribe PrEP and mitigate transportation barriers, such as reducing the number of required appointments.

Gaps in the literature remain, though, preventing scholars and practitioners from a clear understanding of how best to implement PrEP in transgender communities. Few articles attended to process determinants. Our research team similarly found few articles attending to process determinants in the initial systematic review that provided the basis for this manuscript (Li et al., 2022). This is most likely due to the overlap between implementation strategies and process determinants. Implementation strategies are “methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of a clinical program or practice” (Proctor et al., 2013). Process determinants include engaging customers, clients, and patients, executing interventions and implementation strategies, planning (e.g., building local capacity, tailoring interventions to localized communities), and reflecting and evaluating. Each of these are actions undertaken to overcome barriers or utilize facilitators to implementing an innovation. Thus, there may be literature on implementation strategies for PrEP with transgender communities that contain process determinants that were not included within our review. As such, our research team is currently conducting a systematic review of PrEP implementation strategies.

Other scholars, as well, should attend to such strategies for barriers and facilitators we have identified in this manuscript. An example includes the facilitative role of peer navigators. Community role models or peer navigators with shared lived experiences can help increase knowledge about PrEP and model its use by individuals having various rates and kinds of sex (Klein and Golub, 2019; McMahan et al., 2020; Waltz et al., 2019) developed a tool matching CFIR determinants with implementation strategies from the Expert Recommendations for Implementation Change compilation. Using this tool can be helpful in matching barriers with the strategies to overcome them. For example, the need to adapt behavioral interventions for increasing PrEP uptake and adherence can be facilitated through capturing and sharing local knowledge (Waltz et al., 2019). Integrating gender affirmation surgery and PrEP may also serve to increase uptake by overcoming transportation burdens and time constraints, as well as integrating PrEP care into health care that is outwardly inclusive and aware of transgender individuals’ health needs (Sevelius, Deutsch, et al., 2016). Developing ongoing training and education and hiring transgender women can also help to cultivate organizations, clinics, and healthcare facilities with climates that are open and affirmative of transgender individuals and thus increase sustained engagement with transgender patients (Auerbach et al., 2021). Connecting already trialed implementation strategies, such as these with specified determinants, may facilitate PrEP uptake and adherence.

Domestic implementation science, transgender health, and applied transgender studies are each nascent, albeit burgeoning, fields. As such, gaps identified in this manuscript identify key opportunities for future PrEP implementation research with these key populations. There are currently numerous studies identifying individual-level determinants for transgender women (e.g., self-efficacy), community and society-level—or outer setting—determinants (e.g., cissexism, racism, lack of access to gender-affirming healthcare), and innovation-level determinants (e.g., saturation of marketing with cisgender MSM and a lack of marketing specifically to transgender people). We identify four areas of needed growth: expanding research on determinants for transgender men and nonbinary people, analyzing inner setting determinants, rethinking the continued lumping of transgender women and cisgender MSM, and better identifying facilitators of implementation. Finally, we identify what implementation science may offer the field of transgender health writ large.

First, much of the literature on determinants of PrEP implementation for transgender people focuses on transgender women. In our search, we identified only four articles that explicitly included transgender men in their study samples and only one explicitly including nonbinary people. Two studies including transgender men (Theodore et al., 2020; Westmoreland et al., 2020) had too small of sub-samples (3.9% and 0.3% of the total sample respectively) to analyze transgender men’s barriers and facilitators to PrEP implementation. While Descovy is not yet indicated for use by transgender men and nonbinary people assigned female at birth (AFAB), Truvada and Apretude are. And while HIV prevalence rates are not fully known for transgender MSM and nonbinary people, transgender MSM and nonbinary people have been found to engage in high-risk sexual behavior (Herbst et al., 2008; Reisner et al., 2016). Thus, as HIV implementation science continues to grow and develop, researchers must ensure that they expand their focus beyond focusing primarily on transgender women. If future effectiveness trials are conducted with Descovy and other forms of PrEP for transgender men and nonbinary people, we recommend the use of hybrid approaches involving the collection of data on barriers and facilitators to PrEP within these populations (Curran et al. 2013).

Additionally, it may be useful to examine determinants of implementation at the partner-level. For example, Gamarel and Golub (2015) found that partner-level determinants influenced PrEP adoption for cisgender MSM, with participants who reported condomless anal sex outside their primary relationship reporting higher likelihood to initiate PrEP use. As noted earlier, transgender women have reported difficulties negotiating PrEP use with cisgender, heterosexual men partners due to stigma; fear; and lack of awareness among cisgender, heterosexual men. Thus, it may be important to analyze determinants of implementation among cisgender, heterosexual men and to match those determinants with strategies to overcome barriers at the individual- and partner-levels.

Second, implementation researchers should undertake more studies analyzing inner setting barriers and facilitators of PrEP implementation for transgender people. For example, our scoping review details that gender-affirming health care may be an ideal location to increase PrEP uptake. Thus, studies like those examining inner setting determinants for implementing PrEP within pharmacies and primary care settings (Hopkins et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021) are needed for gender-affirming health care. Do gender-affirming care providers have the education and awareness to prescribe PrEP and maintain patients in care? Are there policy, protocol, or guideline factors to consider in the outer setting to undertake such implementation, particularly in the wake of increasing attacks on transgender health care across the US (Conron et al., 2022)? Do gender-affirming care environments have the capacity to implement PrEP? These and more questions are worth examining. Similar analyses can be undertaken examining inner setting determinants for implementing PrEP for transgender women in women-centered care, as well as within trans-specific and trans-led nonprofit organizations.

Third, implementation science (and public health at large) needs to analyze determinants for implementing PrEP for transgender women separate from studies on cisgender MSM. The historical categorization of transgender women as MSM has shifted to current studies analyzing cisgender MSM and transgender women. However, differences in HIV rates and acquisition between cisgender MSM and transgender women (Poteat, German, & Flynn, 2016) and the continued lumping of cisgender MSM and transgender women has made it difficult to assess and review literature on PrEP implementation for our review, as well as others, such as Baldwin, Light, and Allison’s (2020) narrative review of literature on PrEP for cisgender and transgender women. While there are additional factors to consider in making such decisions regarding the lumping of transgender women and cisgender MSM (e.g., funding), this recurring practice is not contributing to the literature for transgender women as much as it may appear from a glance at titles and abstracts in a PubMed search. An alternative approach would be to include transgender MSM with cisgender MSM and transgender women with cisgender women. Such studies would categorize by gender rather than sex assigned at birth and would better represent gendered dynamics of individuals’ social ecologies that shape their health behaviors and experiences. Examples of such research can be found in some implementation strategies and interventions trials, including Walters et al.’s (2021) implementation of a PrEP intervention for cisgender and transgender women and Auerbach et al.’s (2021) interviews with cisgender and transgender women on developing HIV care for all women. It must be noted, though, that limited sub-samples of transgender individuals within samples lumping cisgender MSM and transgender women is not unique to implementation science. Indeed, a review of the inclusion of transgender women in PrEP trials found that transgender women comprised just 0.2% of total trial enrollments (Escudero et al., 2015).

In order to attend to transgender populations’ needs separate from cisgender MSM and cisgender women, researchers can identify strategies used by other researchers in transgender health to obtain larger sample sizes. For example, Kronk et al. (2022) detail a two-step gender and sex identification system within electronic health records that could be utilized for data reporting and analysis. Other scholars have utilized internet samples to reach “hard to reach” sexual and gender minority populations for studies of cannabis-use comorbidities (Gonzalez, Gallego, & Bockting, 2017), mental health and resilience (Bockting, Miner, Romine, Hamilton, & Coleman, 2013), and other analyses (Mathy, Schillace, Coleman, & Berquist, 2002). Researchers can utilize alternative measures for sex and gender in survey research to better capture cisgender, transgender, and nonbinary identification (Puckett, Brown, Dunn, Mustanski, & Newcomb, 2020; Saperstein & Westbrook, 2021). It is also possible that fostering an increased presence of Black and/or Latinx transgender researchers in implementation science as faculty and lead researchers could lead to shifts in how research is undertaken and planned in formative phases (Everhart et al., 2022). Further, creating equitable partnerships with community members by engaging in community-based participatory research can mitigate missteps on the part of researchers (Israel et al., 1998). Finally, it is important that scholars begin to mark analyses of cisgender MSM as such (Brekhus, 1998). In our review, few studies explicitly stated that their analyses were of cisgender MSM despite the MSM included all being AMAB.

Implementation scientists and researchers need to additionally utilize and continue developing and adapting implementation frameworks centering health equity (Baumann and Cabassa, 2020; Brownson et al., 2021). Implementation scientists and researchers develop strategies to mitigate barriers to implementing innovations in everyday life; however, if health equity is not central to such work, including explicit attention to issues of systemic racism, capitalism, cissexism, and ableism, among other axes of oppression, then huge opportunities to increase access to health care and health services will be missed. Institutionalizing health equity within implementation science requires that researchers adequately study and acquire the knowledge and skills necessary to engage in such work (e.g. developing community-engaged recruitment and research skills, engaging in conversation through citation with scholars who have developed a foundation for health equity research, and committing to ongoing racial justice praxis) (Lett et al., 2022). To do so, implementation scientists and researchers can utilize the framework of Critical Race Public Health Praxis, which builds on Critical Race Theory to better capture race as a structural (rather than individual or “biological”) factor and requires that researchers address racism in research context, conceptualization, and measurement and knowledge production (Ford and Airhihenbuwa, 2010). Finally, scholars can look to existing adaptations of implementation frameworks, including Allen et al.’s (2021) racism-conscious adaptation of CFIR and Woodward et al.’s (2019) development of a health equity implementation framework, which was constructed from integration and adaptation of the integrated-promoting action on research implementation in health services (i-PARIHS) framework (Harvey and Kitson, 2016) and the health care disparities framework (Kilbourne et al., 2006). As Shelton et al. (2021) note, “To be a part of the solution in helping to achieve racial/ethnic justice, [implementation science] needs to ground the field in extant scholarship on health equity and racism, and reframe a foundational focus on social justice, equity, and real-world impact.”

While many barriers to implementation (e.g., stigma, SDOH, medical mistrust) are well identified, fewer facilitators of implementation are identified and assessed. Here, implementation researchers could look to the work of transnational implementation science, as well as intersectional HIV research in the US. Wilson et al. (2019) examined barriers and facilitators to PrEP among 339 Brazilian transgender women. They highlighted how transgender women’s engagement in sex work served as a source of “PrEP empowerment,” a potential facilitator of implementation rather than simply a barrier as it almost entirely was in our review. Additionally, researchers can expand work on facilitative factors of PrEP implementation by expanding attention to transgender individuals who currently are on PrEP, with particular attention to determinants of sustained use at a prevention effective level. While not a PrEP- or trans-focused study, Dācus, Voisin, and Barker (2017) performed interviews with HIV-negative, Black, cisgender MSM to better understand how they stayed HIV-negative. They identified individual, social, and community-level resiliency characteristics that serve as facilitators. Xavier Hall et al. (2022) qualitatively analyzed daily diaries of YMSM who were PrEP adherent to understand what facilitated their adherence. They identified strategies for adherence, including checking in with friends, having pill counters, and counseling that adapts strategies to individuals prior to initiating PrEP. Johns et al. (2018; 2021) similarly identified individual-, social-, and community-level protective factors for transgender youths’ overall health and wellbeing, including parental and familial support, having romantic and sexual relationships, transgender visibility, and self-advocacy. Implementation researchers could similarly examine whether such attributes and characteristics facilitate PrEP implementation for transgender people.

Finally, transgender health can gain from implementation science. Transgender people, particularly Black transgender individuals, experience barriers to most, if not all, types of care across the US. Use of CFIR can guide evaluations of barriers and facilitators to implementing new centers of care, as scholars have recently done for the creation of a rural transgender health center (Tinc, Wolf-Gould, Wolf-Gould, & Gadomski, 2020). As clinical advances are made in the field of transgender health, hybrid study designs trialing effectiveness and implementation can be utilized to ensure advances are put into practice with the greatest reach from the start. Implementation strategies can be developed to enhance health equity for transgender populations vis-à-vis COVID-19 prevention (Teixeira da Silva et al., 2021), eating disorder treatment (Duffy, Henkel, & Earnshaw, 2016; Rosenvinge & Pettersen, 2015), and even employment interventions to address structural health inequities (Thompson et al. 2022). Further, it is possible that leveraging implementation science in transgender health and vice versa could provide benefits to both fields and transgender populations at large.

Limitations

Our review has some limitations that should be considered. First, studies included in our review largely focused on transgender women with only four including transgender men and one including nonbinary individuals. Second, we did not differentiate determinant coding by stages of the PrEP cascade, and it will be useful for researchers to do so in the future to assess barriers and facilitators that may require more attention in awareness compared to uptake and/or adherence. Third, our review does not include studies based outside the US. There is a wealth of non-domestic implementation research that attends to the barriers and facilitators of PrEP implementation for transgender populations, and it may be beneficial for future researchers to examine what non-US implementation research on PrEP for transgender individuals has to offer domestic researchers and implementers. Fourth, there were few articles coded as identifying determinants within the process domain of CFIR; process constructs are similar to implementation strategies, which would not have been captured in the initial systematic review identification and selection process focused on determinants. Fifth, our review only consisted of published scholarship in peer-reviewed journals. We did not seek to include the grey literature of unpublished studies. Finally, only the first author (az) performed coding and substantive analysis for this manuscript. We did not assess coding reliability; however, az did routinely assess similarities and differences between her coding and coding in the initial systematic review as a form of reliability checking.

Conclusion

Utilizing CFIR to identify barriers and facilitators to implementing PrEP, we found numerous barriers identified regarding individual characteristics for transgender women; innovation characteristics like cost, marketing, and evidence quality; and outer setting factors, including structural cissexism/racism and other SDOHs. We recommend that implementation researchers expand analyses on inner setting determinants of barriers and facilitators for implementing PrEP for transgender populations in general and specialty health care settings, individual-level barriers and facilitators at the deliverer level, and individual-level barriers and facilitators at the recipient level for transgender men and nonbinary people. Our review also identifies a need for researchers to increase sample sizes of transgender women in multi-population analyses, as well as to attend to the unique barriers, facilitators, and needs of transgender individuals alone (i.e., separate from cisgender MSM and cisgender women). The next step for researchers is to match trans-specific determinants of PrEP implementation with strategies to overcome barriers, enhance facilitators of implementation, and mitigate health inequities.

Authors’ Contributions

The first author conducted the identification of articles for the scoping review, coded the data, analyzed, and drafted the manuscript. The second author provided leadership in the initial systematic review from which this scoping review was developed. The second, third, fourth, and fifth authors contributed to writing and editing of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a supplement grant to the Third Coast Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded center (P30 AI117943; PIs: Mustanski & D’Aquila; Supplement PIs: Mustanski & Benbow), and a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH130325; PI: Newcomb). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The sponsors had no involvement in the conduct of the research or the preparation of the article.

Data Availability

Individuals interested in obtaining data from this review can contact the corresponding author. A list of all articles included within the analysis is also included at the end of the manuscript.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Allen M, Wilhelm A, Ortega LE, Pergament S, Bates N, Cunningham B. (2021). Applying a race(ism)conscious adaptation of the CFIR framework to understand implementation of a school-based equity-oriented intervention. Ethn Dis, 31. doi:10.18865/ed.31.S1.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Auerbach JD, Moran L, Weber S, Watson C, Keatley J, Sevelius J. Implementation strategies for creating inclusive, all-women HIV care environments: perspectives from trans and cis women. Women’s Health Issues. 2021;31(4):332–40. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2021.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin A, Light B, Allison WE. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV infection in cisgender and transgender women in the US: a narrative review of the literature. Arch Sex Behav. 2021;50(4):1713–28. doi: 10.1007/s10508-020-01903-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Cabassa LJ. (2020). Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. Implement Sci, 20(190). doi:10.1186/s12913-020-4975-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bockting WO, Miner MH, Romine RES, Hamilton A, Coleman E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 2013;103(5):943–51. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2013.301241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg LJ. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267–73. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekhus W. A sociology of the unmarked: redirecting our focus. Sociol Theory. 1998;16(1):34–51. doi: 10.1111/0735-2751.00041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks RA, Cabral A, Nieto O, Fehrenbacher A, Landrian A. (2019). Experiences of pre-exposure prophylaxis stigma, social support, and information dissemination among Black and Latina transgender women who are using pre-exposure prophylaxis. Transgender Health, 4. doi:10.1089/trgh.2019.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brownson RC, Kumanyika SK, Kreuter MW, Haire-Joshu D. (2021). Implementation science should give higher priority to health equity. Implement Sci, 16(28). doi:10.1186/s13012-021-01097-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carter JW Jr, Salabarría-Pena Y, Fields EL, Robinson WT. (2022). Evaluating for health equity among a cluster of health departments implementing PrEP services. Eval Program Plan, 90. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2021.101981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). PrEP for HIV prevention in the US. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/fact-sheets/hiv/PrEP-for-hiv-prevention-in-the-US-factsheet.html#:~:text=Preliminary%20CDC%20data%20show%20only%20about%2016%25%20(38%2C454)%20of,among%20people%20based%20on%20sex.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). HIV infection, risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among transgender women–national HIV behavioral surveillance, 7 U.S. cities, 2019–2020. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-special-report-number-27.pdf.

- Chan PA, Patel RR, Mena L, Marshall BD, Rose J, Coats S, Nunn C, A. (2019). Long-term retention in pre-exposure prophylaxis care among men who have sex with men and transgender women in the United States. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 22(e25385). doi:http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jia | 10.1002/jia2.25385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Bacon O, Doblecki-Lewis S, Postle BS, Feaster DJ,. . Liu AY. (2015). High interest in pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV-infection: baseline data from the US PrEP demonstration project. J Acquir immune Defic syndrome, 68(4). doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Colson PW, Franks J, Wu Y, Winterhalter FS, Knox J, Ortega H,. . Hirsch-Moverman Y. (2020). Adherence to pre–exposure prophylaxis in black men who have sex with men and transgender women in a community setting in Harlem, NY. AIDS Behav, 24. doi:10.1007/s10461-020-02901-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Conron KJ, O’Neill KK, Vasquez LA, Mallory C. (2022). Prohibiting gender-affirming medical care for youth. Retrieved from https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/bans-trans-youth-health-care/.

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics [1989]. In: Feminist legal theory. Routledge; 2018. pp. 57–80.

- Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. (2013). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs. Med Care, 50(3). doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dācus J-d, Voisin DR, Barker J. “Proud i am negative”: maintaining HIV-seronegativity among Black MSM in New York City. Men and Masculinities. 2018;21(2):276–90. doi: 10.1177/1097184x17696174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]