Abstract

Epigenetic gene regulatory mechanisms play a central role in the biological control of cell and tissue structure, function, and phenotype. Identification of epigenetic dysregulation in cancer provides mechanistic into tumor initiation and progression and may prove valuable for a variety of clinical applications. We present an overview of epigenetically driven mechanisms that are obligatory for physiological regulation and parameters of epigenetic control that are modified in tumor cells. The interrelationship between nuclear structure and function are not mutually exclusive and are instead synergistic. We explore concepts influencing the maintenance of chromatin structures including phase separation, recognition signals, factors that mediate enhancer-promoter looping and insulation and how these are altered in during the cell cycle and in cancer. Understanding how these processes are altered in cancer provides potential for advancing capabilities for diagnosis and identification of novel therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Chromatin, Nuclear Structure, Epigenetic Control, Transcription, Nucleosomes, Spatial Transcriptomics, Cell Cycle Control, Histones, Tumor Suppression, Non-coding RNAs

An epigenetic perspective of biological control and pathology

A detailed understanding of the complex mechanisms that govern physiological gene expression states is rapidly evolving. Collectively, mechanisms that regulate chromatin structure, including the posttranslational modification of histone proteins (histone PTMs) DNA methylation, transcription factor (TF) binding, and chromatin accessibility, have been classified as so-called epigenetic gene regulatory mechanisms [1]. The plasticity of epigenetic mechanisms that intersect to regulate physiological responses to intrinsic and extrinsic cues (i.e. intracellular signaling, or interactions between specialized cells and the tissue microenvironment, respectively) have been demonstrated to play central roles in a variety of biological processes including, tissue remodeling, metabolism, cell growth, cell cycle, and cell survival as well as competency to establish and sustain the integrity of phenotype-specific requirements for cell and tissue structure and function [2-6].

Alterations in epigenetic mechanisms are increasingly recognized to drive the departure of cells from their specialized properties. Bidirectional epigenetic crosstalk between cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment are decisive for tumor onset and progression. Evidence is accruing for aberrant epigenetic control as key for tumor initiation, progression, and maintenance of the cancer-compromised phenotype [7, 8].

Nuclear structure-gene expression relationships are increasingly considered complementary dimensions to control. There is growing appreciation for the requirement to mechanistically understand the organization, assembly, and localization of regulatory complexes within the context of nuclear architecture [9, 10]. Intranuclear trafficking and phase condensates with requirements for regulatory determinants of transcription factors are being investigated to understand gene expression from a structure-function perspective [11-14]. Nuclear structure and function are no longer considered mutually exclusive and are instead synergistic. Nuclear structure mediates the physiological expression of genes, while the functional molecular mechanisms by which genes are expressed generate dynamic and phase-separated multi-dimensional mega-dalton protein/DNA/RNA complexes. Both processes continuously and synergistically redefine the components of nuclear architecture as a sophisticated factor that generates and responds to external demands for cell-based activities.

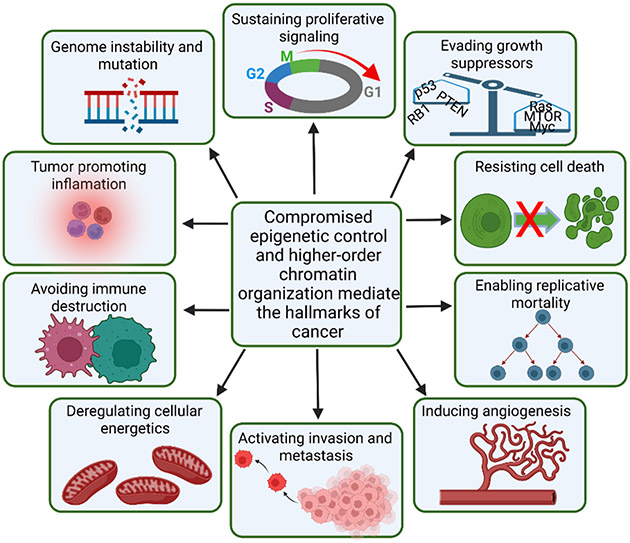

There is increasing recognition that perturbations in parameters of epigenetic control are functionally linked to the determinants of cancer that were identified by Hanahan and Weinberg [15] (Figure 1). A guiding concept is emerging that cancer is predominantly initiated by genetic modifications while predisposition and progression are epigenetically dominated. Clinically, epigenetic pathways provide therapeutic targets because the factors and enzymes that mediate epigenetics have active sites amenable to blockage by small molecules. Furthermore, epigenetic events are capable of priming and enhancing the responsiveness of treatment-refractory tumors to radiation, cytotoxic chemotherapy, and immunotherapy by lowering kinetic barriers to incoming cues emanating from signaling pathways [16-18].

Figure 1. Compromised epigenetic control and higher-order chromatin organization mediate the hallmarks of cancer.

Higher-order chromatin organization supports the gene expression required for cellular identity. Interconnected with the chromosome conformation are the epigenetic states of chromatin that are critical for this genomic regulation. Dysregulation of these chromatin states in the cancer-compromised genome drive all the hallmarks of cancer including sustained proliferation, evasion of growth suppressors, resistance to cell death, enabling of replicative immortality, induction of angiogenesis, deregulation of cellular energetics, avoidance of immune destruction, tumor promoting inflammation, and genome instability and mutation.

The overarching theme of this chapter is to highlight contributions of epigenetic mechanisms that alter gene expression leading to malignant transformation in normal cells. Understanding how these fundamental processes are altered during tumorigenesis will provide a potential for improved cancer diagnosis and identification of novel therapeutics. For the purposes of this chapter we will critically discuss: 1) DNA and histone post-translation modifications and their involvement in tumorigenesis; 2) maintenance of chromatin structures including chromatin fibers, topologically associating domains and compartments and their potential roles in disease states; 3) epigenetic and topological domains that are associated with distinct phases of the cell cycle that may be altered in cancer progression and 4) the requirement for mitotic bookmarking to maintain intranuclear localization of transcriptional regulatory machinery to reinforce cell identity throughout the cell cycle to prevent malignant transformation.

The human epigenome is organized in hierarchical, yet interdependent levels.

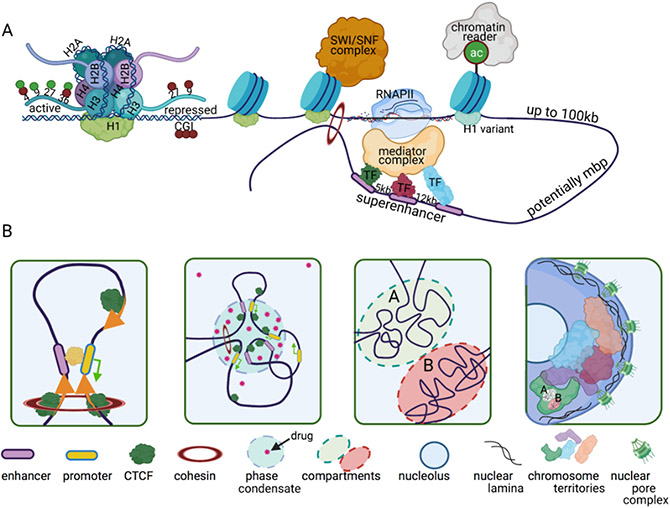

The structure and function of the human genome are integrated to support obligatory parameters of biological control including gene activation or suppression, DNA replication and repair, cell survival and fidelity of cell division[7, 9, 19-31]. Approximately two meters of DNA are contained and organized within the human cell nucleus with an average diameter of 10 micrometers. Proper organization of this length of DNA thus requires a scaling factor of up to five orders of magnitude to fit the genome into the confines of the nucleus. Scaling is primarily mediated by the sequestration of DNA into nucleosomes, but as such packaging of DNA affords gene regulation by altering steric access to genes with the nuclear space. Therefore, the linear DNA sequence of the genome conveys vital but only a limited component of the regulatory information required for physiological control. A hierarchy of interrelated structural and epigenetic information including, DNA methylation, nucleosomes to chromatin fibers, long-range chromosome interactions, topologically associating domains, chromosome territories-- is not encoded within the DNA sequence, but is superimposed on this basic blueprint thereby supporting biological activity (figure 2). Although nuclear compartments are not subdivided by membranes, the regulatory machinery for the various functions carried out by these regulatory compartments that include transcription, splicing, replication, and repair are architecturally organized in nuclear microenvironments that represent phase separated domains (discussed below). Many aspects of these levels of epigenetic and architectural control are compromised during cancer initiation and progression [2, 7, 9, 11, 22-24, 32-76]. While mutations at the level of the DNA sequence are often causative for disease pathology, epigenetic abnormalities are frequently involved in predisposition to cancer and tumor progression. While mutations are difficult to reverse, epigenetic alterations provide more tractable targets and in fact a number of pharmaceutical inhibitors of epigenetic processes have been examined in clinical trials and some have already become standards of care. A comprehensive understanding of the epigenetic alterations in cancer-compromised nuclei will inform enhanced capabilities for tumor diagnosis, prognosis, indications for recurrence, and options for targeted therapy and precision oncology [2, 7, 9, 53].

Figure 2. The human epigenome is organized in hierarchical, yet interdependent levels.

A hierarchy of interrelated structural and epigenetic information is not encoded within the DNA sequence, but is superimposed on this basic blueprint thereby supporting biological activity. A) PTMs of histones within active or repressed chromatin are depicted. While red circles indicate methylation, green circles indicate acetylation. DNA is methylated at CPG islands (CGI). A chromatin loop is depicted wherein a super-enhancer interacts with a promoter. B) A chromatin loop is depicted in which orange arrows indicate the directionality of CTCF motifs. At two convergent motifs a loop is formed. This loop is present in a topologically associating domain (TAD) within a phase condensate (blue circle). Anti-cancer drugs are concentrated within these phase condensates (red stars). These TADs coalesce into active A (green circle) or inactive B (red circle) compartments. At the highest-level compartments are contained within chromosome territories in the interphase nucleus. The chromatin interacts with the nuclear lamina at the nuclear periphery and at the around the nucleoli where heterochromatin in preferentially localized. Although nuclear compartments are not subdivided by membranes, the regulatory machinery for the various functions carried out by these regulatory compartments that include transcription, splicing, replication, and repair are architecturally organized in nuclear microenvironments.

Epigenetic modifications establishing lineage specification are crucial points of alterations during tumorigenesis.

DNA methylation in normal cells and dysregulation in the cancer-compromised genome.

DNA methylation of cytosine residue occurs at regions of chromatin containing CpG dinucleotides, and large repeat regions of CpGs are defined as “CpG islands” (CGI; Figure 2; reviewed extensively in [77-80]). In general, DNA methylation is associated with long term transcriptional silencing and wide-spread chromatin inactivation (e.g., X-chromosome inactivation[81], imprinting[82] and silencing of transposable genomic elements [79, 83]. The regulation of DNA methylation can be characterized by three distinct phases: establishment, maintenance, and demethylation. In humans, the methylation of DNA is established by two DNA methyltransferase enzymes, DNMT3A and DNMT3B, which contain two chromatin reading domains ATRX-DNMT3-DNMT3L (ADD) and PWWP and an MTase domain [79]. DNA methylation is maintained during replication by DNMT1 recruited by the E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase UHRF1 which binds to hemimethylated CpGs at replication forks through its SET and RING associated domains. Demethylation of DNA can occur passively, where non-maintained CpG methylation is diluted during successive rounds of DNA replication or can occur actively through the enzymatic activities of three ‘ten-eleven translocation’ (TET)-dioxygenases that mediate the Vitamin C dependent hydroxylation of methylcytosine: TET1, TET2 and TET3 [84, 85]. DNA methylation at gene promoter or enhancer regions has been demonstrated to affect the binding of transcriptional regulators and other DNA binding proteins through altered affinity to their consensus binding motifs [86]. In addition, methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD) proteins interact directly with methylated CpGs and are bound by several zinc finger domains to contribute to DNA-methylation-based silencing [87]. Furthermore, 5-hydroxymethylation of cytosine (5hmC) is recognized as a highly relevant dynamic epigenetic mark on DNA [88]. Stringent control of DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation is therefore critical for development, to establish and sustain gene expression cell-type specific function, and required to support tissue remodeling.

Abnormal DNA methylation in cancer, mediated by compromised control of the methylation regulatory machinery, results in hypermethylation of CpG sites regulating several tumor suppressor genes (e.g. BRCA1, MLH1, MORT) [89]. The microsatellite landscape is another parameter of genome structure and function influenced by DNA methylation. For example, in Lynch Syndrome, it is known that mutations in the mismatch repair genes such as MLH1 result in microsatellite instability [89] and an increased predisposition to develop colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, or other cancers [89]. In tumor specimens from endometrial patients, methylation of the MLH1 promoter was found to be a common mechanism of gene silencing resulting in MLH1 deficiency [90, 91]. The clinical significance of MLH1 methylation was assessed and not linked to patient survival. However, a retrospective study determined that MLH1 methylation status could be used to predict patient response to adjuvant therapy [92]. Consequently, MLH1 methylation status may provide prognostic value. Other studies have assessed the methylation status of BRCA1 in mammary gland carcinomas that are predominantly associated with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Sharma and colleagues reported methylation at the promoter of BRCA1 in 30% of patients (n=39) [93]. Methylation of the BRCA1 gene was also found to be associated with lower detectable levels of BRCA1 transcript. In a larger study (n=239), 57.3% of TNBC patients were found to have methylation at the promoter of BRCA1 [94]. Methylation of the BRCA1 promoter was found to be an independent predictor of overall survival and disease-free survival in TNBC cases. A recently identified long noncoding RNA, Mortal obligate RNA Transcript (MORT), is silenced by DNA methylation in the initial stages breast tumorigenesis.

Alterations in the enzymes involved in DNA methylation have been identified in cancer. For example, DNMT1 was found to be overexpressed in triple negative breast, pancreatic, gastric, lung, and thyroid cancers [95]. DNMT3A expression is increased in pituitary adenoma, and AML. Similarly, higher levels of DNMT3B are observed in the lung, hepatocellular carcinoma, ovarian and breast cancer. Consequently, targeting their DNA methyltransferase activity using 5-aza-2’deoxycytidine (decitabine, 5-azadmC) is an FDA-approved therapeutic strategy with proven effectiveness in TNBC and hematological malignancies [96]. Mutations or copy-number variations within methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD) proteins occur in many cancers, leading to loss of MBD binding specificity to methylated sites and gene deregulation [87, 97].

Crosstalk between DNA methylation and post-translational histone modifications

The organization_of DNA into higher-order structures is critical for the regulation of biological functions such as gene transcription, replication, and DNA repair. This process is accomplished at the level of nucleosomes, in which ~146 base pairs of this DNA are wrapped around an octameric core of histone protein subunits (H2A, H2B, H3, H4) [98]. These histone proteins are assembled into nucleosomes, where their N-terminal domains can be post-translationally modified at specific residues by acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and poly-ADP-ribosylation. Methylation of H3K4 has been extensively studied, and numerous studies have linked mono-methylation (H3K4me1) to active enhancers [99], whereas trimethylation (H3K4me3) is predominately associated with transcriptionally active or poised promoters [100]. The methylation of H3K4 is largely controlled through the actions of KMT2-family proteins (MLL1, MLL2, MLL3, MLL4, SETD1A, SETD1B) and demethylases of the KDM1 and KDM5 families (LSD1, LSD2, JARID1A, JARID1B, JARID1C, JARID1D) [101]. Acetylation of lysine residues by histone lysine acetyltransferases (KATs) is generally associated with loosening of chromatin for replication, or euchromatic transcriptional activation which is marked by histone H3 lysine 4 acetylation (H3K4ac) at active promoters and H3K27ac at enhancers. This epigenetic modification is reversed by histone deacetylases (HDACs) that remove acetyl groups from the histone tails. While acetylation is an active mark, methylation of histone tail residues denotes either heterochromatic inactivation or gene activation depending on which residue is modified. In contrast to H3K4 methylation which is associated with active enhancers or promoters, H3K27me3 is a facultative heterochromatic mark present over gene bodies that are repressed [102] and H3K9me3 is a constitutive heterochromatic modification present at silenced regions of the genome [103]. The H3K27me3 modification is written by the methyltransferase ‘Enhancer of Zeste Homolog’ (i.e., EZH1 and EZH2) that represents the enzymatic component of the Poly-comb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) multi-protein complex that also contains auxiliary proteins (e.g., EED, SUZ12). The H3K27me3 marks deposited by PRC2 are recognized by chromobox proteins (e.g., CBX2, CBX4, CBX6) and facilitate the recruitment of PRC1, that mediates H2AK119 ubiquitination, resulting in chromatin compaction and repression of transcription. The formation of heterochromatin propagates along chromatin by spreading these repressive post-translational modifications (PTMs), structural proteins, and the associated effector proteins outwards from nucleation sites. The exact extent of this heterochromatic spreading is heritable and has crucial consequences for establishing and maintaining cellular identity.

In pluripotent embryonic stem cells (ESCs), a great deal of functionally significant regulatory elements within the genome are simultaneously marked by both activating and suppressing PTMs. This phenomenon termed bivalency results in poised chromatin states which allows these ESCs cells to rapidly respond to differentiation stimuli to either activate or repress key genes involved in differentiation [104, 105]. While, both poised promoters and poised enhancers contain suppressive H3K27me3, bivalent promoters contain the activating H3K4me3 modification, while bivalent enhancers contain H3K4me1. As a result, this bivalency is resolved into active or suppressed chromatin states during differentiation [106, 107]. The histone code within chromatin is complex in that many residues on a single histone can be modified simultaneously, and different combinations have varying effects on chromatin states. The establishment and maintenance of these chromatin states through the epigenetic landscape of PTMs gives rise to cellular identity and tissue specificity. Recapitulation of bivalency within critical development related genes has been detected in early-stage breast cancer cells_and designated as oncofetal epigenetic control[108-110].

There is significant crosstalk between histone modifications to render genome domains poised for transcription, active or suppressed in a context-dependent manner [111]. While, histone phosphorylation is a critical component of the DNA damage response pathway in the case of H2AX phosphorylation, this epigenetic mark works in concert with acetylation to synergistically regulate gene expression. Moreover, there is significant crosstalk between histone modifications to control replication, transcriptional regulation to maintain cellular identity, and during DNA damage responses [112]. For example, H2BK120ub is associated with active transcription and signals for transcriptional elongation, H3 lysine methylation, and recruitment of the heterodimeric histone chaperone, FACT, including the SSRP1 and SPT16 proteins. During DNA damage and repair, histone tails at damaged chromatin are not only phosphorylated, but additionally acetylated and ubiquitinated [113]. Moreover, since many methyl PTMs on histone H3 are adjacent to residues that are phosphorylatable, a ‘phospho-methyl switch’ is a potential prevalent mechanism to control the association of reader proteins with chromatin in various biological processes [114, 115].

Not only do the epigenetic histone PTMs synergize and crosstalk with each other, but these histone modifications also interact with DNA methylation through the factors that write, erase, and read these modifications [116, 117]. For example, CpG DNA methylation is excluded from the promoters of actively transcribed genes since DNMT3A and 3B bind to H3K4, but are repelled by increased H3K4 methylation thereby activating auto-inhibition of these DNA methylases. Consequently, when H3K4 is methylated, de novo DNA methylation does not occur [79]. In contrast, during transcription RNA PolII recruits the histone methyltransferase, SETD2, to trimethylate H3K36. The PWWP of DNMT3A and B bind to this H3K36me3, thereby deactivating the auto-inhibition, resulting in subsequent DNA methylation of the gene body. Therefore, DNA methylation at the gene body is positively correlated with transcription [118]. H3K27me3 at CpG islands at promoters by Polycomb Repressive Complex 2, is more readily reversible than DNA methylation of these sites, DNA methylation is crucial for mechanisms that include gene imprinting, X chromosome inactivation, and suppression of transposable elements [119]. Maintenance of DNA methylation is also connected with histone H3K9 methylation in that UHRF1 binds to di and trimethylated H3K9 residues [120].

The complex interplay between activating and suppressive marks and DNA methylation at bivalent poised genes is highlighted by the fact that these genes only contain low levels of methylation in normal undifferentiated cells, but are hypermethylated in cancer cells. While DNA methylation is usually associated with decreased expression, in cancer cells is often indicative of upregulated expression [121]. Depletion of DNA methylation has been demonstrated to impact H3K27me3 distribution at bivalent promoters. Recently, bivalent promoters were subdivided into two groups, ones with a high HK27me3: HK4me3 ratio (hiBiv) and those with a low HK27me3: HK4me3 ratio (loBiv). LoBiv promoters are less enriched in canonical Polycomb components, had a lower level of intrachromosomal interactions, and were less sensitive to DNA hypomethylation. In cancer, hiBiv promoters lose HK27me3 and are more susceptible to DNA hypermethylation than loBiv promoters [122].

Alterations in histone modification enzymes in cancer.

Alterations due to dysregulated epigenetic machinery that writes, reads, and erases histone PTMs result in aberrant function of tumor suppressors and promoters in cancer. Disruption of the balance between active and repressive histone-modifying enzymes have been implicated in breast, lung, and colorectal cancer tumorigenesis through mis-regulated post-translational modification of both histone and non-histone substrates that are critical proteins involved in cancer progressions such as p53, MYC, and RB1 [123]. Mutations resulting in haploinsufficiency for these critical factors regulating the epigenetic landscape are among the most mutated genes in cancer [123, 124]. For example, aberrant SET1A activity results in the methylation of histones and YAP [125, 126]. In acute myeloid and lymphoid leukemia (AML and ALL), MLL1 (also known as KMT2A) is frequently translocated with other oncogenic partners resulting in the loss of its catalytic SET domain. These mutations are present in approximately 80% of childhood leukemia and 5–10% of adult leukemia [127]. ]. Moreover, MLL3 and MLL4 are often mutated in cancer as well [128-131]. Mutations within the PHD cluster of MLL3 interferes with its interaction with the tumor suppressor BAP1 which is the catalytic subunit within the Polycomb repressive deubiquitinase complex [129]. While, germline mutations in BAP1 have been demonstrated to predispose patients towards mesothelioma and melanocytic skin tumors, somatic mutations are prevalent in breast, lung, melanoma, clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

Altered KAT activity resulting from chromosomal translocations is involved in the initiation of some types of cancers, specifically lymphoid and hematopoietic tumors. Chromosomal translocations either result in the formation of oncogenic fusion proteins or activate oncogenes by generating new enhancers or promoters [132]. Such translocations have been identified in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in which (q23; p13) (11:16) translocations lead to the generation of the MLL-CBP fusion protein [133]. Other examples of hematopoietic malignancies resulting from oncogenic chromosomal translocations include MLL-P300 fusion protein resulting from t(11;22) (q23; p13) translocation and MOZ-CBP fusion protein because of the t(8;16) (p11;p13) translocation [132, 134]. The overall oncogenic or tumor-suppressive role of KATs is determined by the level of their activity i.e., enhanced activity is associated with oncogenesis or reduced expression results in reduced acetylation. This makes KATs a potential therapeutic target for cancer therapy.

Altered activity of HDACs (e.g., HDAC1, HDAC2) has been reported in many malignancies [135]. To date, eighteen genes encoding four major classes of HDACs (Class I, II, III, and IV) have been identified in the human genome. Class I, II, and IV share sequence and structure homology and require zinc ions for their catalytic activity, whereas class III HDACs or sir-2 like proteins (sirtuins e.g., SIRT1, SIRT2) depend on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) for their catalytic activity and share no sequence or structural homology with other classes of HDACs [17, 135, 136]. Changes in HDACs activity caused by chromosomal translocations can lead to aberrant deacetylation of tumor suppressor genes, and have been implicated in tumorigenesis. In acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) the chromosomal translocations t(15;17) (11:17) leads to abnormal recruitment of HDACs which results in repression of RAR target genes [135, 137, 138]. Other examples where abnormal HDACs recruitment leads to gene silencing and contributes to tumorigenesis include AML-1-ETO t(8;21) and CBFβ-MYH11 (chromosome inversion 16(p13; q22) [137].

Another component of epigenetic machinery involved in regulation of gene expression are “reader” enzymes which selectively bind to individual or a combination of histone PTMs and read the molecular information defined by them [139]. These epigenetic readers recognize specific histone PTMs and have conserved domains, on basis of which they are classified into different families For instance bromodomains (BRDs) that are well known to recognize acetyled-lysine residues, while plant homeodomains (PHDs), chromatin organization modifier (chromodomains or CRDs), tudor domain, the proline-tryptophan-tryptophan-proline (PWWP) motif, and the malignant brain tumor (MBT) domains all bind to methyl-lysine or methyl-arginine residues [139-141]. Tumor cells are frequently associated with abnormalities due to mutations, insertions, deletions, or chromosomal translocations in histone reader enzymes. These aberrations can cause deregulated gene expression or expression of TFs that ultimately leads to oncogenesis and foster cancer progression. For instance, a loss-of-function mutation in the bromodomain BAF180 is associated with clear cell renal carcinoma. Moreover, mutations in PHD finger domains have been reported in breast cancer and melanoma and fusion of the PHD finger region of lysine demethylase 5A (KDM5A) with nucleoporin 98 (NUP98) results in abnormalities leading to leukemia [139]. Fusion of bromodomain proteins such as BRD-3 or BRD-4 to nuclear protein of the testis (NUT) transcriptional regulators results in formation of an oncoprotein that binds to acetylated histones which drives aberrant transcriptional machinery activity and ultimately leads to NUT carcinoma. Overexpression of another critical bromodomain reader protein ATAD2, recognizes the diacetylated histone H4K5ac and 4K12ac modification during replication, and is predictive of poor prognosis in breast cancer, lung cancer, and ovarian cancer [142-150]. Since these enzymes play a crucial role in the regulation of cell function, cancer initiation, and progression, they can serve as potential therapeutic targets in oncology. Current research suggests that small molecules targeting chromatin reader domains such as BET bromodomain inhibitors are efficacious in the treatment of cancer [151, 152].

Chromatin structures including chromatin fibers, topologically associating domains and compartments and histone modifications

Chromatin organization beyond the single nucleosome level is first characterized by their association into the chromatin fiber. These are arrangements of repeated nucleosomes that are periodically separated by 20 to 75bp of DNA [153, 154] that are heterogeneous in diameter ranging in size from 5 to 24nm [155]. In between these nucleosomes, the H1 linker histone protein binds at a ratio of approximately 1 per nucleosome [156]. Histone H1 variants are differentially localized in euchromatin or heterochromatin and perform various functions in chromatin structure and dynamics through differences in post-translational modifications (PTMs) [157]. Due to their capability to stabilize nucleosomal arrays and to promote compaction of the chromatin fiber, the H1 linker histones have been considered general transcriptional repressors. Despite this, knockouts of specific H1 variants do not result in global genomic activation, but differential patterns of down and upregulation of specific genes [158]. Knockout of three H1 variants in ES cells, also resulted in differences in DNA methylation , suggesting a further connection between the epigenetics of the H1 linker histones and DNA methylation [159]. Histone H1 PTMs and their impact on chromatin compaction, transcription, DNA repair, and differentiation are extensively reviewed by Andrés and colleagues [160]. Another dimension to H1 mediated control is suggested by the recent demonstration that ablation of the Histone Nuclear Factor P (HINFP) factor regulating H1 gene expression in drosophila results in altered chromatin organization, transposon activation, and genomic instability [161]. Mutations in genes encoding histones and their expression levels have been associated with oncogenesis. For example, downregulation of histone H1 mRNA expression 40% has been reported in ovarian adenocarcinoma. Moreover, different expression levels of histone H1 subtypes are associated with several malignancies such as upregulation of histone H1.5, which has been reported in metastatic prostate cancer [162-164].

A key component controlling chromatin remodeling is the activity of the SWI-SNF complex. SWItch - Sucrose Non-Fermentable (SWI-SNF) is a set of genes encoding enzyme complexes that are involved in transcriptional regulation through ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. SWI-SNF complexes alter histone-DNA contacts thereby changing the position or completely disrupting the nucleosomal structure [165]. Consequently, the access of DNA regulatory factors to the chromatin is altered which in turn affects processes such as replication, transcription, recombination, and repair[166]. In addition to the composition of the SWI-SNF subunits, post-translational modifications including acetylation, sumoylation, methylation, and phosphorylation play a key role in modulating the activity of the SWI-SNF complex. For example, phosphorylation of SWI-SNF complex components by P38 kinases at the onset of myogenic differentiation modulates chromatin structure and facilitates activation of genes associated with myogenesis [167]. Mutations in genes encoding the components of SWI-SNF complex are emerging in tumor initiation and progression. It has been hypothesized that almost 20% of human tumor cases are associated with mutations in at least one component of SWI-SNF complex. ARID1A, a tumor suppressor gene of the SWI-SNF complex, is frequently mutated in cancer and is associated with a worse clinical prognosis [165, 166, 168]. Another example is with the SMRCB1 gene, which is also a component of SWI-SNF complex, where alterations are associated with multiple familial malignancies and familial schwannomatosis [166].

SWI/SNF is critical for paraspeckle (PS) assembly in the interchromatin domain of the nucleolus, distinct from nuclear speckles [169], by recruiting and facilitating essential Paraspeckle protein (PSP) interactions for proper assembly[170]. In fact, BRG1, the core ATPase subunit of the hSWI/SNF complex, physically interacts with PSPs and lncRNAs independent of ATPase activity [170, 171], suggesting a structural role of BRG1 in paraspeckles separate from its canonical chromatin remodeling function. While the exact function of these paraspeckles remains unclear, there is speculation that their purpose is associated with the presence and retention of specific RNAs involved in determining cell fate, such as pluripotency versus differentiation [171]. Current models suggest that coordinated assembly by long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) and DBHS proteins occurs in close proximity to chromosomal loci to create distinct sub-nuclear bodies. The initiating cellular signal or event that triggers paraspeckle assembly remains unclear. These unique nuclear bodies display a rich composition of RNA, especially the mammal-specific lncRNA, NEAT1, which is essential for paraspeckle assembly, architecture, and maintenance [171]. The remaining elements of paraspeckles consist of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) involved in transcription and RNA processing [171]. At this point, more evidence is required to determine if the information for paraspeckle assembly and function is epigenetically regulated and conserved through subsequent cellular division cycles.

How the chromatin fiber folds into higher-order structures

The three-dimensional conformation of the chromatin fiber is a critical component regulating gene expression under a variety of physiological conditions, including cell cycle, differentiation, and disease states. Although enhancers can be megabases away from the gene(s) they regulate, they can support transcription by looping in 3D space [33, 34, 172, 173]. These enhancer-promoter contacts are re-organized in response to developmental and signaling cascades. Examples include IFNG [174], MHC Class II [175], the β-globin locus [176-178] and CFTR [179]. The binding of transcription factors is coincident with this conformation. For example, the transcription factor RUNX1 interacts with the CD34 gene promoter and its downstream regulatory elements in hematopoietic stem cells[35]. Similarly, the interaction between the beta-globin gene and its regulatory sites is dependent upon the transcription factors EKLF1 and GATA1 [180]. The osteocalcin gene is architecturally remodeled to support bone tissue-specific gene expression and promotor occupancy by the RUNX2 transcription factor [181-202]. The histone gene loci respond to transcriptional requirements at the G1/S phase cell cycle transition with modifications in chromatin structure that include histone modifications [187, 203-213], nucleosome organization [214], and higher-order chromatin confirmation [43, 187, 215, 216], to orchestrate competency for promotor occupancy by regulatory complexes in a cell cycle responsive manner [217-219] with modifications in tumor cells [43, 210, 220-230]. In addition, the transcription factor SATB1 is required for an enhancer to interact with the Rag1 and Rag2 genes during thermal cell development [231]. Although, many studies have demonstrated that transcription is simultaneous with enhancer-promoter contacts, it is still unclear as to whether these interactions are causative for gene expression. Despite this, evidence suggests that enhancer-promoter looping can influence transcription. For example, forced chromatin looping between the mouse beta globulin gene and its locus of control leads to a dramatic increase in transcription [172] More recently, with the advent of catalytically inactive dCAS9 variants that are dimerized after treatment with light [232] or small molecules [233], it has been demonstrated that such forced chromatin looping can reversibly activate transcription.

While there is considerable data demonstrating support for the requirement of enhancer-promoter interactions for the induction of transcription, several alterative lines of evidence suggest that they are not required. For example, the distance between the Sonic Hedgehog gene (Shh) and its enhancers was actually shown to increase during differentiation of neural progenitors [234]. Moreover, looping of enhancers to promoters that pre-exist before transcription have been described including TNF-responsive enhancers [235] and during thrombopoietin signaling in hematopoietic stem cells [236]. While studies have shown that these signaling cascades do not induce widespread alterations in enhancer-promoter interactions, other studies have attempted to interfere with transcription to determine if these interactions can be disrupted. For example, depletion of P53 resulted in decreased expression of target genes, but the persistence of long-range enhancer-promoter contacts [237]. Similarly, BET inhibition has been shown to inhibit transcription, but there were few changes in the configuration of chromatin [238]. While these are compelling findings suggesting that transcription and enhancer-promoter looping are independent, they are not mutually exclusive with the idea that these contacts are required in many cases. For example, the factors that are altered may not be driving specific contacts but are recruited to pre-existing loops.

Subnuclear trafficking and phase separation- mechanisms that contribute to the subnuclear organization assembly and activity of regulatory complexes in nuclear microenvironments.

One major question in the field of nuclear structure is how membrane-free compartments and microenvironments form and how the nuclear machinery is properly localized within these domains. Proper localization of nuclear machinery is critical for proper epigenetic regulation. Historically, one hypothesis has been that the nucleus contains a nuclear matrix wherein a 3-D filamentous network, analogous to the cytoskeleton, including the nuclear lamina, residual nucleolus, and ribonucleoprotein complexes, and nuclear matrix-associated DNA, collectively provides a structural framework for nuclear organization [24, 239]. The nuclear matrix is a composite organization of architecturally organized regulatory machinery within the nucleus. This architectural organization is dynamic and remodeled structurally and functionally in response to regulatory cues. Mechanisms that mediate the organization and assembly of the nuclear matrix are open-ended, however recent findings have demonstrated that many of these components are dynamically assembled. While an inclusive model for the steps that target proteins to subnuclear sites is unclear, there are many apparent intranuclear targeting signals within transcription factors. Alterations in the binding to aspects of this nuclear matrix affect the proper subnuclear localization of transcriptional machinery. For example, mutation of as little as one amino acid in the nuclear matrix targeting signal of RUNX factors results in their mis-localization. The addition of Matrix Attachment Regions (MARs) [240], which serve as chromatin attachment points within the DNA sequence, have been shown to increase transgene expression and transfection efficiency [241-246]. In contrast, while Lamina Associated Domains (as reviewed in [247, 248]) are also associated with organizing the nucleus, artificially tethering genes to the nuclear lamina by targeted recruitment of YY1 results in chromatin repression and re-localization to the nuclear periphery or nucleolus [249].

Another proposed mechanism driving the formation of membrane-free nuclear bodies is termed lipid-like phase separation (LLPS) in which liquid-like condensates or droplets form through weak multivalent interactions between macromolecules [250-252]. Physiological levels of cations have been shown to induce LLPS of reconstituted arrays of nucleosomes. The addition of the linker histone H1 to these reconstituted arrays promoted LLPS and increased the concentration of nucleosomes within condensates and while also decreasing the dynamics of droplets consistent with H1’s generally repressive function. While reconstituted chromatin microinjected into nuclei form condensates, nucleosomal arrays with acetylated histone tails did not readily form droplets [253]. The dissolution of droplet formation was restored upon the addition of BRD4 before microinjection [253]. The droplets with acetylated and BRD4-associated chromatin associate, but do not coalesce with condensates with chromatin that is not acetylated [254]. In addition, the presence of transcription factors such as HOXA13, HOXD13, RUNX2, and TBP, within these droplets is dependent upon the macromolecular interactions that occur with the transcriptional machinery [253]. Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs) within these transcription factors drive their ability to form LLPS bodies. Lengthening of these IDRs interferes with their ability to form condensates and to co-condensate with transcriptional coactivators. These two mechanisms, subnuclear trafficking versus LLPS, are not mutually exclusive. Both models posit that the physical properties of macromolecular complexes drive principles of nuclear organization. LLPS of regulatory components that comprise transcriptional conjugates into nuclear sub-compartments such as the nuclear lamina, nucleolus, histone locus bodies, cajal bodies, splicing domains, and other subnuclear domains, contribute to the architectural organization of regulatory machinery in nuclear microenvironments. Recognition Signals within regulatory factors may drive their inclusion within nuclear microenvironments simultaneously with the physical properties in other domains such as IDRs.

Super-enhancers in cancer

Hotspots within the genome wherein multiple enhancers are generally clustered within 5-12.5kb of each other, are collectively termed super-enhancers (SEs). These sites are critical for supporting gene expression profiles to maintain cellular identity and regulate the expression of master transcription factors that control cell fate. As expected with the observation that nucleosomal arrays that are acetylated and associated with BRD4 form condensates that are separated from un-acetylated chromatin, LLPS has also been demonstrated to play a critical role in the formation of super-enhancers [252, 255-257]. Moreover, the LLPS of anti-cancer drugs into these critical genome regulatory elements is a key property to consider in that their inclusion or exclusion from condensates can affect efficacy. A comprehensive understanding of which SEs are active within disease states and the properties governing LLPS of SEs and drugs will provide insight into therapeutic strategies.

SEs have been linked to cancer development and progression. Li et al. performed ChIP-Seq of H3K27ac in tumors grown in the thoracic mammary gland of mice and identified a total of 661 SEs compared to control [258]. Elevated levels of histone H3K27ac and H4K8ac were found in clinical breast cancer patient samples (Luminal A, Luminal B, Basal-like, and Her-2) compared to native tissues when assessed by IHC arrays. Additionally, a subgroup of SEs marked with H3K27ac was identified (n=148) and associated with higher transcriptional activity and cancer-related pathways. Recently, Huang et al. performed ChIP-Seq for H3K27ac in TNBC and non-TNBC subtypes [259]. For example, the promoter of FOXC1 has a SE specific to TNBC and is more highly expressed in TNBC patients than in other subtypes (Her-2, Luminal A, Luminal B, and Normal-like) and correlates with an overall poorer survival. Depletion of FOXC1 by CRISPRi inhibits spheroid growth and invasiveness that is rescued by FOXC1 over-expression [259].

To study the role of SEs in colorectal cancer, 73 pairs of primary tumor tissues and corresponding adjacent tissues were collected from patients to generate 147 transcriptome profiles of H3K27ac using ChIP-Seq [260]. A total of 9896 and 10663 active promoters were identified in native and tumor tissues respectively. Comparison to other studies revealed that 32.4% of the enhancers identified in this study were novel enhancers. A total of 6690 variant enhancer loci were identified in colorectal cancer (5590 gain and 1100 lost, respectively). Of these, 455 variant super-enhancer loci (VSEL) were identified (334 gain and 121 lost, respectively). The VSEL in tumor tissues was located at well-known oncogenic targets such as MYC, VEGFA, and LIF. To verify the function of VSELs identified, 11 SEs were targeted by CRISPRi. Enhancers and super-enhancers are constrained within higher nuclear microenvironments described in the subsequent section.

Higher-order chromatin structures, TADs, and compartments

The chromatin fiber is folded into globular, self-interacting, insulated topologically associating domains (TADs) [261-264]. One of the major proteins involved in the insulation of TADs and mediating intra- and inter-chromosomal looping interactions is CTCF [265]. CTCF contributes to the interconnected nature of the various levels of nuclear organization through its interactions with chromatin remodeling proteins, histone-modifying enzymes, and transcription factors. Through these interactions it is implicated in a myriad of fundamental regulatory functions including imprinting [266], X chromosome inactivation [267], and organizing the major histone locus [43]. Although the mechanism by which TAD and chromatin loops are constructed is not fully understood, interaction between CTCF and the cohesin complex (SMC) for chromosomal structure maintenance are vital for the process known as the loop extrusion model [268, 269]. This model posits that two strands of DNA are held together by a cohesin ring and create loops by actively extruding the DNA. Once cohesin encounters a CTCF protein occupying a motif in a convergent orientation, a loop is formed [269]. Even though CTCF cannot be knocked out due to its essentiality [270], studies have depleted it using siRNAs or by tagging it with an auxin-inducible degron (AID). siRNA knockdown of CTCF decreased intra-TAD interactions slightly while increasing inter-TAD contacts [271]. Auxin-induced degradation of CTCF [272] resulted in a greater decrease in CTCF levels and led to a loss in TAD insulation, but did not alter intra-TAD contacts [273]. Less than 20% of TAD boundaries were unaffected by depletion of CTCF. Another study found that although CTCF depletion reduced genomic occupancy of cohesin, its knockdown slightly weakened TAD boundaries and most TADs remained unchanged [274]. More recently, it has been determined that some CTCF binding sites are more resistant to the removal of CTCF [275] . While CTCF sites that are maintained are unaltered, sites where CTCF is lost, are more altered in their TAD structure. Despite the fact that CTCF knockout is lethal, it was determined at a very early stage that the loss of CTCF results in disruption of TAD insulation [276].

TADs coalesce into two primary compartments that are either euchromatic, termed A, or heterochromatic, termed B [277, 278]. These compartments are further subdivided into six computationally distinct sub-compartments, two that are euchromatic and four that are heterochromatic [279]. More recently, these sub-compartments have been posited as a spectrum of compartments from those that are at the extremes and are either heterochromatic or euchromatic, while some TADs associate with both A and B compartments [280]. The euchromatic B compartments are noticeably less gene-rich, transcriptionally inactive, marked by inactive epigenetic signatures, and preferentially inaccessible to DNaseI than euchromatic A compartments [69, 281]. While, nucleosomal spacing is directly regulated by histone H1 PTMs, the triple knockout of three histone H1 variants in mESC cells resulted in more global alterations in higher-order nuclear organization. Although segregation between A and B compartments generally appears at TAD boundaries, depletion of cohesin and/or CTCF did not alter A and B compartmentalization [273, 282]. These results suggest that compartmentalization is independent of CTCF and the establishment of TADs.

Although CTCF is a major player in chromatin organization, other factors are likely are involved in these processes. Compelling evidence for other mechanisms driving TAD delineation include the fact that CTCF is absent at many TAD boundaries and that orthologues of CTCF do not exist in some species [283-287]. In these ancestral genomes, phase separation may be the predominant mechanism by which TAD structures form. As described above, high acetylation of histone tail leads to destabilization of chromatin domain [288]. This destabilization of the chromatin domain may explain the accumulation of epigenetic markings indicating genes actively transcribed at the TAD boundary (such as housekeeping genes) [263]. Indeed, expression data can predict the three-dimensional folding of the genome [289, 290]. Splitting the TAD boundary based on active expression independent of CTCF binding appears to be more common in Drosophila melanogaster [289, 291]. The Drosophila TAD boundary indicates that there are more transitions between open and closed compartments than in the nucleus of human cells [289]. The different properties of the active and inactive genes have been shown to predict Drosophila TAD boundaries based on polymer simulations [291]. Therefore, Drosophila TAD responds to transcriptional stimuli (e.g., recovery from heat shock [292] or activation or transcriptional inhibition of the conjugated genome [293]. The fact that higher-order chromatin organization within ancestral genomes are more specified by epigenetic states than that of the human genome suggests that human cells have greater control over these processes.

At the highest level of organization within the nucleus, chromosomes occupy discrete territories [24, 294]. These chromosome territories (CTs) are non-randomly distributed within the interphase nucleus. For example, the relative radial positioning of individual CTs has been demonstrated to be correlated with gene density, chromosome sequence length, and euchromatic state. Because transcriptionally inactive heterochromatin is preferentially localized around the nuclear periphery, the inactive X (Xi) CT is more peripheral than its active (Xa) counterpart. Chromosomes with longer sequence lengths have also been shown to be more peripheral than shorter ones. Several other factors have been implicated in the radial positioning of CTs such as interactions with nucleoli [295-297] or the nuclear lamina [298]. Nuclei from patients with Progeria express abnormally truncated lamin-A and as a result have a disordered radial arrangement of CTs [299].

Alteration of nuclear organization is implicated in hallmarks of cancer

The nucleus of cancer cells are generally larger, more irregularly shaped, and intranuclear sub-compartments, such as the nucleoli, are altered in their number and morphology [11, 59, 300]. Pathologists have long exploited these changes in nuclear architecture as useful diagnostic tools for recognizing malignancy [11, 59]. While it is well-known that epigenetics signals and nuclear morphology are disrupted in cancer onset and progression, emerging evidence demonstrates significant concomitant changes in higher-order chromatin organization.

Alterations in the epigenetic landscape in cancer nuclei affect chromatin structure. All of the functional properties of epigenetic regulation such as DNA methylation, histone PTM, nucleosome spacing, and chromatin remodeling are altered in cancer. Changes in these features influence the phase separation of condensates resulting in modifications to chromatin accessibility and/or long-range chromatin interactions at regulatory elements such as promoters, enhancers, insulators, and silencers. Moreover, alterations in these properties contribute to differences in topologically associating domains in cancer. Moreover, TAD boundaries can be shifted or disrupted in cancer. Since enhancer-promoter interactions are generally constrained within TADs, translocations, inversions or deletions that result in aberrant TADs can result in enhancers contacting inappropriate promoters. Even in unaltered TADs, mutations and/or dysregulated expression levels in transcription factors, such as YY1 and RUNX1, that facilitate enhancer-promoter interactions may perturb these contacts. Beyond the gene regulatory loops being altered, the fact that CTCF and its binding sites are mutated in many cancers, including breast cancer, suggests its functions in gene regulation and chromatin insulation are also perturbed upon malignant transformation [301-304].

Higher-order chromatin organization facilitates DNA repair and directly suppresses endogenous DNA damage. Chromatin with increased accessibility is more prone to exogenous and endogenous damage. Interestingly, heterochromatin is preferentially localized to the nuclear periphery where exogenous insults such as UV radiation are more prevalent [305]. Hence, heterochromatin could in principle absorb DNA damage insults. Indeed, it has recently been demonstrated that mutations occur more frequently in the chromatin at the nuclear periphery [305]. These regions of the genome are also less likely to contain critical regulatory genes. An open question is whether the nonrandom probabilistic radial positioning of chromosomes within nuclei as homologous recombination requiring physical interaction between homologs. Since, smaller chromosomes are confined to the nuclear interior and larger chromosomes are more peripheral the chance of self-interaction is likely higher. Alterations in the radial positioning of chromosome territories and interactions between small chromosomes has been identified in breast cancer [306].

Epigenetics and higher-order chromatin organization impact on all the hallmarks of cancer [15] including the resisting of induction of angiogenesis [307-309], activation of invasion and metastasis, cell death, replicative immortality [308, 310], evasion of growth suppressors, and sustained proliferative signaling [308, 311]. These hallmarks are all critical in the alterations that occur within the cell cycle of cancer cells.

Cell cycle

The cell cycle is controlled by complex and interdependent processes that require epigenetically mediated remodeling of the genome and the structural and functional regulatory machinery that governs fidelity of DNA replication and cell division. Crosstalk between mechanisms that coordinate proliferation and cell growth is obligatory, with unique requirements that are phenotype dependent. Many normal and tumor cells exhibit unrestricted proliferation. However, stringent control of the cell cycle is compromised in tumor cells, often reaching the balance between proliferation, cell survival, and responsiveness to physiological cues as well as acquiring resistance to therapy that targets cell cycle check points. We will provide an overview of the decisive regulatory parameters for cell cycle control that are mechanistically and clinically informative. Emphasis is on genome reconfiguration during the cell cycle that is required for epigenetically-mediated cell cycle and mitotic progression with competency to retain regulatory machinery during mitosis for transmission from parental to progeny cells.

Interplay between cell cycle progression, cellular transcriptional machinery, and epigenetics

Progression between distinct phases of cell cycle depends on correct timing of various events, which are coordinated by cellular transcriptional machinery and epigenetics controlling genome accessibility.

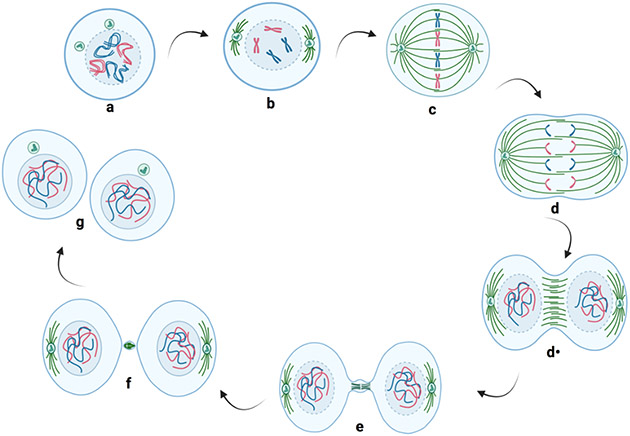

The cell cycle consists of interphase (G1, S, and G2 phases), mitotic phase (mitosis and cytokinesis, figure 3). During G1, cells nearly double their size, preparing for DNA replication. At the restriction point late in G1, the genes for deoxynucleotide biosynthesis are expressed, supporting competency for DNA synthesis. This preparation is carried out by assembling the pre-complex DNA replication at the replication origins. CDC6 is essential for the assembly of pre-replicative complex (pre-RCs), which are located on the origins of DNA replication [225, 228]. At S-phase, histone gene expression is initiated. The pre-replication complexes become active followed by the separation of the two DNA strands of the double helix, and by an elongation step catalyzed by DNA polymerase. Once DNA replication is completed, the chromosomes and Centrosomes are duplicated, and the amount of DNA is doubled in the cell. During G2 phase, the cells grow rapidly, and the checkpoint machinery ensures that the DNA is properly replicated and repaired when damage occurs. Centrosomes detach and undergo growth by the accumulation of pericentriolar material around the centrioles. This leads to centrosome maturation, which is a necessary step for assembly of the mitotic apparatus to enter M-phase.

Figure 3. Chromosomes during interphase and mitotic M-phase.

a. The chromatin is present within chromosome territories during interphase. b. In prophase, the chromatin starts to condense into chromosomes and the nucleolus disappears. Centrosomes migrate to the opposite poles of the nucleus and initiate the formation of the mitotic spindle. c. During prometaphase-metaphase, the nuclear envelope breaks. Then, the chromosomes are oriented and aligned on the metaphase plate. d. In early anaphase, the sister chromatids separate, and the microtubules pull the chromatids apart toward the two opposite poles of the mitotic spindle. d· In late anaphase, the plasma membrane begins to invaginate to the equatorial plane. e. During telophase, the plasma membrane continues to invaginate, and the chromosomes decondense. f. During cytokinesis-abscission, the invagination of the plasma membrane appears through a contractile ring. The cleavage furrow progresses to create a midbody between the progeny cells, which disappears during the abscission process. g. This results in separation of the two progeny cells, which enter interphase and begin the process again.

Several studies investigated the structure, function, and regulation of the human histone genes, focusing especially on the cell cycle regulation of histone gene transcription and histone mRNA coupling with DNA replication. Genome-wide high-resolution chromosome conformation capture (HiC) technologies indicate that non-random higher-order organization of genes into structural domains supports regulatory activities involving non-contiguous sequences that influence transcription [212, 221, 312, 313]. The human histone locus bodies (HLBs) are nonmembrane bound, phase-separated domains that provide microenvironments for dynamic regulation of histone genes. The human histone gene transcription factor HINFP mediates coordinate expression of multiple histone H4 genes at the G1/S transition in normal and cancer cells, as well as the abbreviated human embryonic stem cell cycle [212, 221, 225, 228, 312]. Importantly, HINFP loss-of-function causes increased nucleosome spacing, induces replicative stress, and leads to genomic instability [313]. The overall increase in nucleosome spacing could be due to the insufficiency of newly synthesized histone H4 during DNA replication. In vivo mouse models, HINFP is essential for fidelity of histone H4 gene expression and required for early embryonic development [313, 314]. Furthermore, the role of HINFP in guarding normal chromatin organization is functionally conserved in flies [315]. NPAT is an essential and prototypical HLB resident protein that regulates expression of all replication-dependent histone gene classes (H4, H3, H2A, H2B, H1). HINFP is the critical anchor that tethers NPAT to histone H4 genes [316, 317]. In response to activation of the cyclin E/CDK2 cell cycle signaling cascade at the onset of S phase, NPAT is phosphorylated to initiate histone gene transcription [318-320]. Furthermore, deregulation of histone gene expression upon sustained loss of HINFP or NPAT causes disruption of HLBs and has drastic consequences for cell division and cell survival in both normal and cancer cells [313, 321, 322]. These findings establish that regulatory interactions involving HINFP and NPAT are essential for chromatin conformations at HLBs during the cell cycle to regulate histone gene transcription. Thus, understanding molecular mechanisms that control histone synthesis at the onset of S-phase would be a paradigm for transcriptional control that is obligatory for cell cycle progression.

GRO-seq, RNA-seq, and ChIP-seq analyzed the transcriptional and epigenetic dynamics during the cell cycle in breast cancer MCF-7 cells [323]. This study identified genes differentially transcribed at the G0/G1, G1/S, and M phases in MCF-7. There was no correlation between the transcription and steady-state mRNA abundance at the cell-cycle level. Active transcription occurred only during early mitosis. However, an overall increase in histone modification marks was reported at mitosis. Thousands of enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) and their associated transcription factors were identified, which were related to cell-cycle–regulated transcription but not to the steady-state expression.

Consequently, these results showed that the interplay between the transcriptional machinery and epigenetics are crucial for cell-cycle progression and that the precise understanding of cell cycle control is of great interest for understanding such pathologies as cancers.

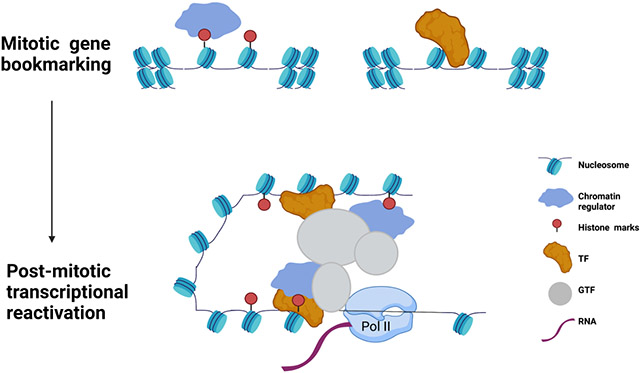

Epigenetic control during mitosis

Mitosis plays a fundamental role to transmit stable inheritance of gene expression pattern from parental cells to their progeny [324]. During this phase, the nuclear envelop breaks down is disaggregated, triggered by the disassembly of nuclear pore complexes and lamina depolymerization [325, 326]. This process leads to chromatin becoming highly compacted into chromosomes [327]. During mitosis, many transcription factors dissociate from chromatin leading to significant downregulation of transcriptional activity [328]. However, there is little knowledge of how lineage-specific epigenetic information is faithfully maintained in progeny cells. Several studies suggest that the gene regulatory networks are controlled by epigenetic bookmarks that are maintained during mitosis [53-55, 328-331] (figure 4). In human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), bivalent genes with both the activation mark (H3K4me3) and repressive mark (H3K27me3) are important for maintaining pluripotency [332, 333]. However, during mitosis, the bivalent genes containing H3K4me3 are the most upregulated genes upon differentiation of hESC, showing a new aspect of epigenetic regulation crucial for the maintenance of pluripotency [332-334].

Figure 4. Mitotic bookmarking establishes post-mitotic reactivation of gene expression.

During mitosis, histone marks and chromatin regulators bind the open regions on the chromatin thus bookmarking specific loci for the memory program. Transcription factors can additionally associate to the chromatin targets. Consequently, these mechanisms result in a post-mitotic transcriptional activation after mitosis.

The entry of mitosis is controlled by CDK1/cyclin B kinase also known as MPF (M-phase Promoting Factors). CDK1/cyclin B is responsible for direct and indirect phosphorylation of substrates involved in mitosis. Histone H1 is a direct substrate of CDK1/cyclin B [335]. Other substrates include CDK1 regulators like CDC25 and Wee1, and cytoskeletal proteins like microtubules, nuclear lamina, and vimentin, are required for the proper progression of mitosis [336-339]. Most recently, it has demonstrated that the S-phase initiator CDC6 plays a crucial role in controlling mitotic M-phase entry. CDC6 regulates CDK1 activity and determines the timing of mitosis in Xenopus cell-free extract [340-344]. Inhibition of CDC6 results in earlier M-phase entry in Xenopus cell-free extract as well as in mouse zygotes. CDC6 modulates the activity of CDK1 via cyclin B and not cyclin A and acts through a bona fide CDK inhibitor Xic1 [340, 343]. Additionally, CDC6 regulates both G2/M transition and metaphase-to-anaphase transition during the first meiosis of mouse oocytes [345]. This suggests that the time of mitosis is not only under the control of cyclins as it has been described in the last 20 years [346, 347], but additionally under the control of CDC6 which can counterbalances the cyclins to control CDK1 activation, and subsequently to specify the timing of mitosis.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the epigenetic control and correct timing of mitosis play a coordinating role between gene regulatory networks, cell cycle machinery, and the developmental program, ensuring accurate inheritance of the genome during cell division.

Mechanisms of chromosome behavior during mitosis

Mitosis is composed of four basic phases: prophase, prometaphase-metaphase, anaphase, and telophase [348].

During prophase, the chromatin begins to condense into chromosomes and the nucleolus disappears. The chromosomes consist of two sister chromatids; each contains a DNA element called centromere that connects both chromatids [349]. The two sister chromatids are glued with cohesin. However, kinetochores are assembled at centromeres to ensure the interaction of chromosomes with spindle microtubules. In prophase, microtubules depolymerize, centrosomes migrate to opposite poles of the nucleus, and initiate the formation of the mitotic spindle.

During prometaphase-metaphase, the breakdown of the nuclear envelope (NEBD) occurs, and chromosome condensation begins. This is carried out by activation of the histone H1 kinase activity resulting in hyperphosphorylation of nuclear lamins, leads to NEBD, and shortens microtubules by phosphorylation of Microtubule-Associated Proteins (MAPs). Then, the chromosomes are captured by microtubules attached to kinetochores. At metaphase, the chromosomes are distributed at their kinetochores and assembled uniformly on the equatorial plate of the spindle. Three types of microtubules nucleated at the centrosomes can be distinguished i) kinetochore microtubules ii) polar microtubules pointing directly to the opposite spindle pole iii) astral microtubules radiating out of the spindle. The balance between ejection and pulling forces exerted on chromosomes permits the alignment of chromosomes on the metaphase plate. At this stage, the ubiquitin ligase Anaphase Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C), which is involved in the degradation of cyclins, becomes active [350]. This activation is carried out by a series of phosphorylation on APC/C complex induced by CDK1. Therefore, APC/C triggers degradation of the cyclins, allowing inactivation of CDK1 and subsequently separation of the sister-chromatid.

During anaphase, active segregation of sister chromatids takes place within the mitotic spindle. When APC/C becomes active, it catalyzes ubiquitination and degradation of securin relieving the inhibition from separase. The latter is responsible for the cleavage of cohesins allowing separation of sister chromatids [351]. In parallel, the microtubules pull the chromatids apart toward the two opposite poles of the mitotic spindle. In late anaphase, the plasma membrane starts to invaginate to the equatorial plane and the cell enters telophase.

In telophase, the nuclear envelope is reformed around the chromosomes entering the interphase state of de-condensation. The plasma membrane continues to invaginate, and the elongation of polar microtubules stops leading to the formation of the central spindle. In higher eukaryotes, this process is known as open mitosis, ensuring inheritance of chromosomes to the newly formed cells [352]. However, because the nuclear envelope does not break down during mitosis in lower eucaryotes, the mode of mitosis is referred to as closed mitosis [353].

During cytokinesis, the cytoplasm, organelles, cell membrane and the two formed nuclei split into two progeny cells. This is characterized by a cleavage furrow formed perpendicular to the mitotic spindle. The invagination of the plasma membrane appears through a contractile ring, where actin and myosin microfilaments play mechanical roles. The cleavage furrow progresses to create a midbody between the progeny cells. The midbody disappears during the abscission process leading to separation of the two daughter cells.

Taken together, these results showed how accurately chromosomes are distributed and organized at each stage of mitosis. Chromosome organization must be highly dynamic during mitosis to ensure inheritance to the progeny cells.

Recent reports have provided an update about the current knowledge on mechanisms of chromosome regulation across mitosis [354-356]. They examined how the pairs of homologous chromosomes are continuously separated at mitosis. It has been shown that mammalian cells disrupted homologous chromosome pairing by keeping the two haploid chromosome sets separately and by positioning them on either edge of the nuclear division axis, defined by centrosomes. Loss of mitotic anti-pairing causes loss of heterozygosity (LOH) and is correlated with gene mis-regulation in cancer cells. This suggests that anti-pairing plays a significant role in inhibition of genetic recombination or allelic mis-regulation across cell division. How mitotic recombination is prevented and how genomic stability is maintained during division are fundamental unanswered questions. For example, what are the regulatory mechanisms involved in haploid set chromosome sequestration? Is the cytoskeleton implicated in this process? In Drosophila, chromosome pairing can be actively inhibited, and several studies suggest that condensin II could play a role in regulating the anti-pairing activity [357-360]. Consequently, how does condensin II regulate mitotic anti-pairing in human cells?

Condensin-mediated remodeling of mitotic chromosomes

Nuclear DNA is highly condensed and wrapped around nucleosomes to fit inside the nucleus [361]. Each nucleosome is formed by a set of eight histone proteins — two copies each of the histone H2A, H2B, H3, H4, and 146-nucleotide pair DNA double helix. The latter is wrapped 1.65 times around the histone core to form a fiber structure of 10 nm width, described as ‘beads on a string’. Nucleosomes are stabilized by the histone H1 and compact the genomic DNA sevenfold. Additional compaction occurs during interphase to fully organize the DNA inside the nucleus. Upon mitotic entry, the chromatin highly condenses into mitotic chromosomes, positions at the metaphase plate, and avoids being disrupted during anaphase. The condensation of chromatin is controlled by condensins and post translational modifications [362]. The condensation events start before NEBD. The chromatin fibers fold and reach 700nm of diameter by the end of prophase approximately [363]. These events are in part due to the activation of CDK1/cyclin B and of condensins by phosphorylation [364]. Condensins depletion leads to a delay in mitotic compaction [365, 366].

Atomic force microscopy is an excellent technique to visualize condensins during mitosis [367]. Unlike other microscopes, it does not use photons nor electrons (like in electron microscopy) to produce images. Condensin is composed of two proteins of the family of SMC (Structural maintenance of chromosome) as well as three non-SMC subunits: a kleisin (NCAPH) and two HEAT domain proteins (NCAPG/D) [368]. There are two condensin types, condensin I and II, which differ by their non-SMC proteins. Condensin II binds the chromatin fiber throughout the cell cycle, while the condensin I complex binds the chromosomes only after NEBD. Both condensins I and II contribute to mitotic compaction [369]. However, it seems that condensin I act on the fibers that condensin II did not compact, thus promoting a lateral compaction of the fibers, and subsequently sustaining a stable condensed chromatin [370].

Cohesins interact with chromatin in G1 and attach the sister chromatids to each other during S-phase. A fraction of condensins II associates with duplicated regions during S-phase then initiates sister chromatid resolution. In prophase, the majority of cohesins are released from the chromosomal arms, condensins II associates with chromosomes inducing condensation. After NEBD, condensins I is directed to chromosomes and keep facilitating the condensation. In anaphase, the separase cleaves the kleisin subunit of cohesins, and allows separation of sister chromatids.

Several studies have shown that binding of condensin I to prometaphase requires the mitotic kinase Aurora B [371]. In the presence of topoisomerases I, Condensins fold the chromatin fiber into super loops to form the mitotic chromosome [372]. Later in mitosis, the axial compaction of chromosomal arms requires condensins activities in combination with sister chromatid resolution mediated by topoisomerase II and release of cohesins [373].

The condensation can take place in condensing-depleted cells; however, it is associated with chromosomal structural defects [370]. In S. pombe yeast, mutants of SMC proteins are not able to condense their chromosomes but remain capable of carrying out the elongation of the mitotic spindle and cell division [374]. In animals, condensation is affected but not completely abolished by the loss of condensins [370]. Moreover, Knock-out of SMC2 in chicken DT40 cells or Knock-down by RNAi (RNA interference) in C. elegans affects the architecture of the mitotic chromosome but has a limited impact on the condensation itself [365, 366]. Together these results suggest that several factors are important for the chromosome compaction during mitosis.

Chromatin decondensation upon the mitotic exit

In mitosis, Haspin and Aurora B are dissociated from the chromosomes and recruited to the centromeres [375]. Therefore, the histone H3S10PO4 and H3T3PO4 modification levels gradually decrease during metaphase/anaphase transition. Despite the reduction in H3 phosphorylation, the chromosomes remain condensed until telophase. During telophase, the mitotic chromosomes decondense and regain its interphase nuclear structure.

The exit from mitosis requires inactivation of kinases and reversion of mitotic dephosphorylations of mitotic substrates by phosphatases PP1 (protein phosphatase 1) and PP2A (protein phosphatase 2A) [341, 342, 344]. Depletion of PP1 and PP2A delays the exit from mitosis [376]. PP1 is responsible for the dephosphorylation of Thr23, Ser10 and Ser28 of histone H3 [377]. These dephosphorylations allow histone H4K16 reacetylation and chromosome decondensation. However, PP1 is directed to chromosomes by its Repo-man subunit. Depletion of Repo-Man alters the reformation of the nuclear envelope but has no visible consequence on the chromatin decondensation [378, 379]. PP1 is recruited at chromosomes undergoing decondensation by Ki-67 (MKI67) [380], which could compensate the loss of Repo-man. Because PP1 is recruited before the reformation of the nuclear envelope, this suggests a direct role of PP1 in mitotic decondensation; yet the mechanism is still unclear [381].

To study decondensation mechanisms upon mitosis exit, an interesting approach has been developed in vitro using Xenopus laevis cytoplasmic egg extract system which recapitulates mitotic decondensation [382]. These experiments showed that chromatin decondensation requires energy in the form of ATP and GTP, suggesting that decondensation is an active process and not just chromatin relaxation caused by the dissociation of condensation factors. This is consistent with the fact that decondensation is dependent on the presence of factors present in Xenopus eggs [382]. The dependency on ATP can be explained by the fact that the dissociation of Aurora B requires the ATPase protein p97/VCP [383]. Another ATPase complex has been involved in decondensation, the RuvB-like 1/2 complex [382]. In addition to its implications in many cellular processes, RuvB-like 1/2 is a component of several interphase ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes [269], suggesting that it may act at the end of mitosis to regain an interphasic structure.

Involvement of TADs and CTCF in chromatin structure re-configuration after mitosis

As mentioned above, TADs play a key role in the regulation of gene expression along promoters, enhancers and silencers respectively activate or repress transcription [384]. For example, by folding DNA in space, enhancers and promoters interact and modulate transcription. It is then obvious that an enhancer must be in the same TAD as its target genes. This allows for several genes within the same TAD to be co-regulated by the same enhancer.

The formation of TADs was demonstrated by validating the Loop extrusion model [384]. This mechanism involves cohesin and CTCF proteins which recognize motifs around TADs and drag chromatin through rings [279, 285] . Both cohesin and CTCF are enriched at TAD boundaries [271]; however, their depletion makes TADs less prominent [385].

During mitosis TADs are absent; however, how TAD formation is controlled during the cell cycle remains unclear. Recent 5C analysis demonstrated that TADs and CTCF loops are present in interphase, but absent on mitotic chromatin [386], as stated in previous studies [387]. Additionally, ATAC-seq and CUT&RUN analysis showed reduced accessibility and loss of CTCF binding in prometaphase.

More recently, it has been demonstrated that depletion of CTCF during the M- to G1-phase progression alters the re-formation of chromatin domain boundary and structural loops, leading to inappropriate interactions between cis-regulatory elements (CREs) [388]. Thus, CTCF plays a crucial role in the formation of nuclear architecture during G1 entry, and along transcription, it contributes to chromatin structure re-configuration after mitosis.

Mitotic gene bookmarking: an epigenetic program for cell identity