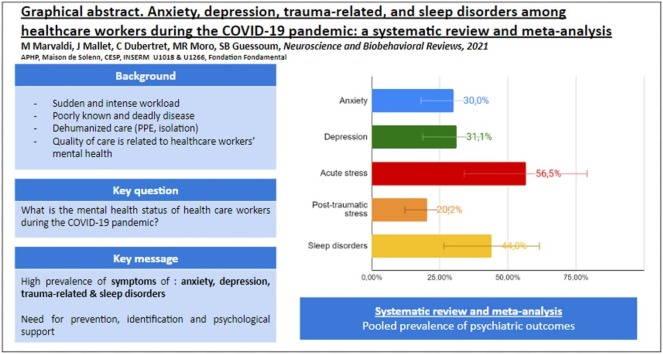

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: HCW, Healthcare worker

Keywords: COVID-19; Depression; Anxiety; Stress disorders, traumatic, acute; Sleep wake disorders; Psychological trauma; Healthcare workers; Meta-analysis; Systematic review

Abstract

Healthcare workers have been facing the COVID-19 pandemic, with numerous critical patients and deaths, and high workloads. Quality of care is related to the mental status of healthcare workers. This PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis, on Pubmed/Psycinfo up to October 8, 2020, estimates the prevalence of mental health problems among healthcare workers during this pandemic. The systematic review included 70 studies (101 017 participants) and only high-quality studies were included in the meta-analysis. The following pooled prevalences were estimated: 300 % of anxiety (95 %CI, 24.2–37.05); 311 % of depression (95 %CI, 25.7–36.8); 565 % of acute stress (95 %CI - 30.6–80.5); 20,2% of post-traumatic stress (95 %CI, 9.9–33.0); 44.0 % of sleep disorders (95 %CI, 24.6–64.5). The following factors were found to be sources of heterogeneity in subgroups and metaregressions analysis: proportion of female, nurses, and location. Targeted prevention and support strategies are needed now, and early in case of future health crises.

1. Introduction

In 2020, healthcare workers (HCWs) have been facing a dramatic pandemic due to a new, poorly known, and deadly disease: Coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) (WHO, 2020). HCWs have been working in critical care conditions, including unprepared doctors and nurses who had to work in urgently opened critical care departments (Zangrillo et al., 2020). Doctors and nurses have been facing extreme work pressure, fast adaptations to intense critical care situations, unseen amounts of severe critical patients, numerous deaths of patients, and risks of infection (WHO, 2020; Guessoum et al., 2020; Spoorthy et al., 2020). Quality of care is known to be related to the mental status of HCWs (Tawfik et al., 2019; Pereira-Lima et al., 2019). Therefore, focusing on the mental health of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic is necessary for their wellbeing and for healthcare quality. Finally, these mental health problems contribute to the high turnover rate of HCWs, which affects the costs of medical institutions through training costs and decreased productivity (Kim et al., 2018).

COVID-19 was first reported in Wuhan in December 2019. COVID-19 quickly spread to the rest of China and then to the rest of the world, leading the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare the situation as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (Huang et al., 2020). To date, more than 70.4 million cases and 1.6 million deaths due to COVID-19 have been reported (WHO, 2020). This sudden thread is an unprecedented worldwide burden on mortality and morbidity, which healthcare workers are directly exposed to.

Studies from previous epidemics, such as SARS, Ebola or MERS, have shown that the sudden onset of an unknown disease with a high mortality rate would affect the mental health of HCWs (Liu et al., 2012; Lung et al., 2009; Maunder et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2009). The lack of personal protective equipment, the reorganization of units and services with the integration of new teams, the fear of being infected or infecting family members or patients, the need to make difficult ethical choices about prioritizing care, feeling of helplessness, and the loss of social support due to lockdown could have a psychological impact on healthcare workers (Sun et al., 2020; Thomaier et al., 2020; Khusid et al., 2020). Moreover, some HCWs have been working in somehow dehumanized conditions, wearing protective personal equipment, and dramatically limiting family visits to all patients, including terminally ill ones (Guessoum et al., 2020; Mallet et al., 2020b).

Some studies have sought to assess the mental health of caregivers at earlier stages of the pandemic (Shaukat et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Carmassi et al., 2020). However, the pandemic is evolving fastly, and numerous studies have been published in the last months. There is a need to gather these data to get a worldwide overview on the mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, early reviews could not capture easily post-traumatic stress disorders, which need a one-month delay after exposure to traumatic events (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). We chose to study four indicators (anxiety, depression, trauma-related, and sleep disorders) for several reasons: First, they are renowned and validated outcomes described in DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), for which there are validated scales usable in the general population (Kroenke et al., 2001; Spitzer et al., 2006; Bastien et al., 2001; Creamer, Bell et al. 2003); Second, many studies have been led on these outcomes among healthcare workers; Third, some specific interventions exist on these outcomes; Finally, these four outcomes are also well described when facing stress factors or psychological trauma in case of crisis (such as COVID-19 pandemic) (Shanafelt et al., 2020; HAS, 2020).

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to estimate the prevalence of anxiety, depression, trauma-related, and sleep disorders of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement, whose checklist was strictly followed (Table S1, supplementary materials), and conceived according to consensus among researchers (Liberati et al., 2009). This study was not prospectively registered with any formal registry.

2.1. Search strategy, selection criteria, study selection, and data extraction

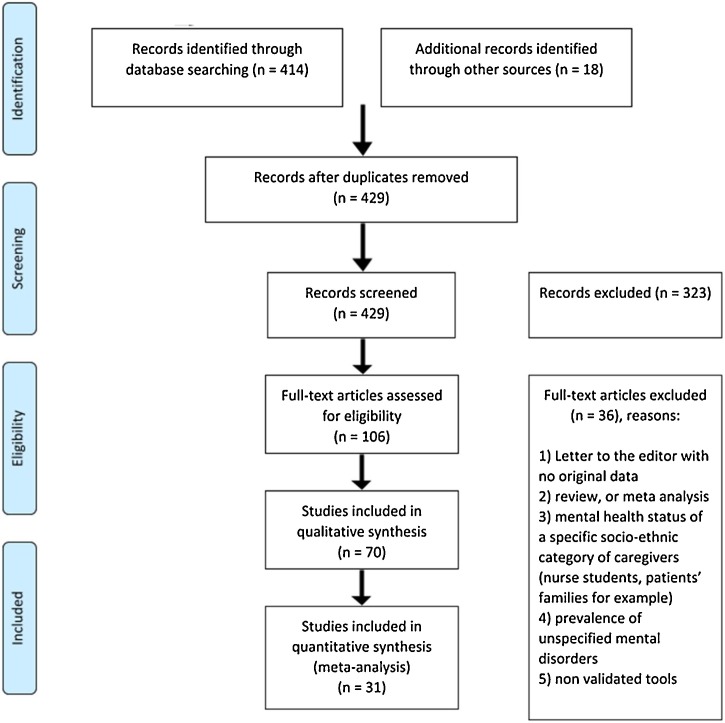

MM and SBG searched on two databases (Pubmed and Psycinfo) using no language restriction. The following words were chosen in regard to previous studies on COVID-19 and mental health: ("Physicians" OR "Nurses" OR "Nursing Assistants" OR "Caregivers") AND ("severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2" OR "COVID-19") AND ("Depression" OR "Anxiety" OR "Suicidal Ideation" OR "stress disorders, traumatic, acute" OR "Mental Health" OR "Mental Disorders" OR "Sleep Initiation and Maintenance Disorders" OR "Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic"). MM and SBG systematically screened then selected the studies by reading titles, abstracts, and full-texts for eligible studies. Additionally, they cross-referenced our research with the last meta-analyses on similar topics (Serrano-Ripoll et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020a, 2020b). The search process is shown in the flowchart (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart diagram.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) study evaluating prevalence rates of mental health symptoms of HCWs in practice during the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) using validated scales, (3) published until October 8th, 2020 in peer-reviewed scientific journals.

The exclusion criteria were : (1) Letter to the editor not providing original results, (2) duplicated publications, (3) studies evaluating impact of the quarantine, (4) mental health status of a particular socio-ethnic category of caregivers (nurse students for example), (5) case reports, qualitative studies, literature reviews, and meta-analyses, (6) full-text non-available, (7) prevalence of unspecified mental disorders. When unclear, inclusion or exclusion was discussed within the group of researchers.

For the meta-analysis, the outcome measure was the prevalence of four well defined mental health outcomes: depression, anxiety, trauma-related disorders (Acute Stress and Post-traumatic Stress), and sleep disorders in HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

MM and SBG extracted data on the following variables independently: authors, year, region, time, study design, target population, study setting, sample size, participation rate, healthcare worker type, gender proportion, assessment methods, and cut-off used. If any of this information was not reported, the necessary calculations (e.g. from percentage to number of HCWs) were done, where possible. When similar scales were used across studies, we selected common cut-offs as much as possible, admitting different cut-offs if no other option. In case of disagreement, the issue was discussed within the group of researchers.

2.2. Quality assessment of the reviewed studies

The risk of bias was evaluated through quality assessment of the studies, using the following criteria, extracted from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the NIH's quality assessment tool for Observational Cohort and Cross‐Sectional Studies, and the Crombie’s items in order to be applicable for our review question (Crombie, 1996; NIH, 2020; Zeng et al., 2015): (a) clearly specified and defined population, (b) participation rate ≥ 50 %, (c) time period used for identifying subjects is indicated, (d) sample size > 600, and consistency in the number of subjects reported throughout the study, (e) outcome measures clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants. Each item answered “yes” scored 1.

2.3. Data analysis

For the meta-analysis’s main outcomes, we extracted data from studies with a score ≥ 4/5.

A proportion meta-analysis was performed to assess the overall pooled prevalence of each outcome. Heterogeneity was assessed by using the Cochran Q test, P values below 0.10 were considered indicative of heterogeneity (Higgins et al., 2019). I2 values were calculated to estimate variation among studies attributable to heterogeneity, with I2 ≥ 75 % representing high heterogeneity (Higgins and Thompson, 2002). Since a high heterogeneity across studies was expected, a random-effect model (DerSimonian-Laird) was considered, as opposed to the fixed effects model to adjust for the observed variability (Ades et al., 2005). This heterogeneity was further explored through subgroup analyses and metaregressions (to test the influence of sample size, study location, proportion of nurses, of females, and scale). Definitions of frontline HCWs were too different from a study to another to enable subgroup analyses. A Freeman-Tukey transformation was used to calculate the weighted summary proportion under the random-effects model, as previously described (Miller, 1978). Meta-analysis results were displayed with forest plots in which the measure of effect for each study is represented by a square, triangle or circle, and the area of each square is proportional to study weight. In addition, we calculated the prediction interval. Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the potential impact on the results (leave-one-out method).

We evaluated the potential publication bias by funnel plots supplemented by the Egger regression asymmetry test (p value<0.10). All statistical tests were two-sided. Significant level α was set at 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc© (Version 19.1, Ostend, Belgium) and OpenMetaAnalyst software. We used the JAMOVI software package for R to perform the Forest and Funnel Plots.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

414 articles were analyzed over database research. After de-duplication and complete screening of the papers, plus cross-referencing with other systematic-reviews, 70 articles were included in the present systematic review (flowchart, Fig. 1).

3.2. Characteristics of the studies

The 70 cross-sectional studies included 101,017 participants. They are presented in Table 1 . Most of the studies were conducted in China (30), India (6), Turkey (5), and the USA (4). The other studies were conducted in 19 countries of Asia and Europe. 43 studies included both physicians and nurses, 12 included nurses only, and 15 included physicians only.

Table 1.

Systematic review.

| Reference | Country & date (months of year 2020) | Total of participants No | response rate | Assessment tools |

Cut off | Healthcare workers (%) |

Gender | Anxiety No (%) | Depression No (%) | PTSD No (%) | ASD No (%) | Burn Out No (%) | Sleep disorders No (%) | Distress No (%) | Appraised quality of the study | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians | Nurses | Others | Female %, No | ||||||||||||||

| Abdulah et al., 2020 | Iraqi Kurdistan April | 268 | 67% | AIS | 6 | 100 % | 29.9 %, 80 | 183 (68.3) | 4 | ||||||||

| AlAteeq et al., 2020 | Saudi Arabia March | 502 | N-A | PHQ-9 GAD-7 | 5 5 | 22,10 % | 26,30 % | 51,60 % | 319%, 160 | 258 (51,4) | 277 (55,2) | 3 | |||||

| Almater et al., 2020 | Saudi Arabia March April | 107 | 30,60 % | PHQ-9 GAD-7 ISI PSS-10 | 5 5 8 14 | 100,00 % | 43,9%, 47 | 50 (46,7) | 54 (50,5) | 48 (44,9) | 77 (72) | 3 | |||||

| An et al., 2020 | China March | 1103 | N-A | PHQ-9 | 5 | 100% | 90,8 %, 1002 | 481 (43,6) | 4 | ||||||||

| Apisarnthanarak et al., 2020 | Thailand March | 160 | N-A | GAD-7 | 5 | 32 % | 38 % | 30 % | 59 %, 94 | 68 (42,5) | 3 | ||||||

| Arafa et al., 2020 | Egypt, Saudi Arabia April | 426 | N-A | DASS-21 - depression - anxiety - stress | 10 8 15 | 48,40 % | 24,20 % | 49,8 %, 212 | 251 (58,9) | 294 (69) | 238 (55,9) | 3 | |||||

| Azoulay et al., 2020 | France, April-May | 1058 | 67,00 % | HADS - depression - anxiety | 7 7 | 29,10 % | 68,30 % | 2,60 % | 71 %, 751 | 533 (50,4) | 322 (30,4) | 5 | |||||

| Badahdah et al., 2020 | Oman April | 509 | N-A | GAD-7 | 10 | 38 % | 62 % | 80 %, 407 | 132 (26) | 3 | |||||||

| Caliskan et al., 2020 | Turkey March | 290 | N-A | HADS - depression - anxiety | 7 10 | 100 % | 38.26 %, 111 | 103 (35.52) | 180 (62.07) | 3 | |||||||

| Chatterjee et al., 2020 | India March-April | 152 | N-A | DASS-21 | N-A | 100 % | 21.7 %, 33 | 60 (39.5) | 53 (34.9) | 50 (32.9) | 2 | ||||||

| Chew et al., 2020 | Singapore & India February-April | 906 | 90,60 % | DASS-21 - depression - anxiety - stress IES-R | 10 8 15 24 | 29,60 % | 39,20 % | 31,20 % | 64,3 %, 583 | 142 (15,7) | 96 (10,6) | 67 (7,4) | 47 (5,2) | 5 | |||

| Cai et al., 2020 | China January February | 709 | N-A | PHQ-9 GAD-7 ISI IES-R | 5 5 8 34 | 100 % | 96,5 %, 684 | 333 (46,9) | 374 (52,8) | 184 (26) | 66 (9,3) | 4 | |||||

| Civantos et al. 2020 | USA April | 349 | 8,00 % | Mini-Z Burnout Assesment GAD-7 IES PHQ-2 | 3 10 26 2 | 100 % | 39 %, 136 | 167 (47,9) | 37 (10,6) | 96 (27,5) | 76 (21,8) | 3 | |||||

| Corbett et al., 2020 | Ireland April-May | 240 | 40 % | GAD-7 PHQ-9 | N-A N-A | 15 % | 36.25 % | 48.75 % | 88.83 %, 175 | 50 (21.0) | 49 (20.3) | 2 | |||||

| De Sio et al., 2020 | Italie April | 695 | 32,40 % | GHQ-12 | 4 | 100 % | 45,5 %, 316 | 619 (89,1) | 4 | ||||||||

| Di Tella et al., 2020 | Italie March April | 145 | N-A | STAI-Y BDI-II PCL-5 | 41 13 33 | 50 % | 50 % | 72 %, 104 | 103 (71) | 106 (31) | 38 (26,2) | 3 | |||||

| Dosil et al., 2020 | Spain April | 421 | N-A | DASS-21 AIS | N-A 6 | N-A | N-A | N-A | 80.285 %, 338 | 156 (37) | 115 (27,4) | 122 (28,9) | 197 (46,7) | 1 | |||

| Elbay et al. 2020 | Turkey March | 442 | N-A | DASS | N-A | 100 % | 57 %, 252 | 228 (51,6) | 286 (64,7) | 182 (41,2) | 2 | ||||||

| Elkholy et al., 2020 | Egypt April may | 502 | N-A | PHQ GAD-7 ISI PSS | 5 5 8 9 | 60 % | 40,00 % | 50 %, 251 | 384 (76,4) | 388 (77,2) | 340 (67,7) | 406 (80,8) | 3 | ||||

| Gupta et al., 2020 | India March-April | 1124 | 79,44 % | HADS | 8 | 66,60 % | 12 % | 36,1 %, 406 | 419 (37,2) | 353 (31,4) | 5 | ||||||

| Han et al., 2020 | China February | 21199 | 96,21 % | SAS SDS | 50 53 | 100 % | 99 %, 20987 | 4573 (20,6) | 6371 (28,7) | 5 | |||||||

| Hong et al., 2020 | Chine February | 4692 | N-A | PHQ-9 GAD-7 | 10 10 | 100 % | 96,9 %, 4547 | 380 (8,1) | 441 (9,4) | 4 | |||||||

| Hu et al., 2020 | China February | 2014 | 99,60 % | SAS SDS | 50 50 | 100 % | 87,1 %, 1754 | 834 (41,4) | 876 (43,5) | 5 | |||||||

| Huang et al., 2020 | China February | 364 | N-A | SAS | 50 | 32,70 % | 67,30 % | 59 %, 214 | 85(23,4) | 3 | |||||||

| Imran et al., 2020 | Pakistan April May | 178 | N-A | PHQ-9 GAD-7 SASRQ | 8 7 N-A | 100 % | 56 %, 100 | 40 (22,6) | 47 (26,4) | 8 (4,4) | ESA : 3 Depression : 4 Anxiety : 4 | ||||||

| Jahrami et al., 2020 | Bahrain April | 257 | 91.78% | PSQI PSS | 5 14 | 31.1% | 46.3 % | 22.6 % | 70.0 %, 180 | 193 (75.2) | 216 (84) | 4 | |||||

| Juan et al., 2020 | Chine February | 456 | 91,20 % | PHQ-9 GAD-7 IES-R | 5 5 24 | 42,80 % | 57,20 % | 70,6 %, 322 | 144 (31,6) | 135 (29,6) | 197 (43,2) | Depression : 4 Anxiety : 4 ASD : 3 | |||||

| Kannampallil et al., 2020 | USA April | 393 | 29,00 % | DASS-21 - depression - anxiety - stress PFI | 10 8 15 1,33 | 100,00 % | 55 %, 216 | 73 (18,6) | 107 (27,2) | 160 (40,7) | 97 (24,7) | 3 | |||||

| Khanal et al., 2020 | Nepal April-May | 475 | N-A | HADS - depression - anxiety ISI | 8 8 8 | 33,90 % | 35,20 % | 526%, 250 | 112 (23,6) | 114 (24) | 127 (26,7) | 3 | |||||

| Khanna et al., 2020 | India April | 2355 | N-A | PHQ-9 | 5 | 100 % | 43.44 %, 1023 | 768 (32,6) | 4 | ||||||||

| Koksal et al., 2020 | Turkey April | 702 | N-A | HADS - depression - anxiety | - 7 - 10 | 48,30 % | 51,70 % | 70,1 %, 492 | 404 (57,5) | 259 (36,9) | 4 | ||||||

| Labrague and Santos, 2020 | Philippine N-A | 325 | 93,00 % | COVID-19 anxiety scale | 9 | 100 % | 74,8 %, 243 | 123 (37,8) | 3 | ||||||||

| Lai et al., 2020 | Chine January February | 1257 | 68,70 % | PHQ-9 GAD-7 ISI IES-R | 10 7 15 26 | 39,20 % | 60,80 % | 76,7 %, 964 | 561 (44,6) | 634 (50,4) | 440 (35) | 427 (34) | 5 | ||||

| Li et al., 2020 | Chine January-February | 176 | N-A | HAMA | 7 | 100 % | 77,3 %, 136 | 136 (77,3) | 2 | ||||||||

| Liu et al., 2020 | China February | 512 | 14,70 % | SAS | 50 | N-A | N-A | N-A | 84,7 %, 433 | 64 (12,5) | 3 | ||||||

| Lu et al., 2020 | China February | 2299 | 94.88 % | HAMA HAMD | 7 7 | 88,82 % (physicians + nurses) |

11.18 % | 77.64 %, 1785 | 569 (24.75) | 268 (11.66) | 3 | ||||||

| Mahendran et al., 2020 | China April | 120 | 96,00 % | GAD-7 | N-A | 30 % | 50 % | 20 % | 73 %, 88 | 64 (53,3) | 3 | ||||||

| Ng et al., 2020 | Singapore April | 421 | 92,00 % | GAD-7 MBI - EE - DP | 10 27 10 | 57 % (physicians + nurses) | 43 % | 73,9 %, 311 | 59 (14) | 183 (43,5) | 3 | ||||||

| Ni et al., 2020 | China February | 214 | N-A | GAD-2 PHQ-2 | 3 3 | 37,80 % | 50,5 | 11,6 | 68,8 %, 147 | 47 (22.0) | 41 (19.2) | 3 | |||||

| Nie et al., 2020 | China February | 263 | 30 à 40 % | IES-R GHQ-12 | 20 4 | 100 % | 76,7 %, 202 | 194 (73,8) | 66 (25,1) | 2 | |||||||

| Ning et al., 2020 | China February | 612 | N-A | SAS SDS | 50 53 | 51,80 % | 48,20 % | 72,9 %, 446 | 100 (16,3) | 153 (25) | 4 | ||||||

| Podder et al., 2020 | Inde April | 373 | N-A | PSS-10 | 14 | 100 % | 44,5 %, 171 | 320 (85,9) | 3 | ||||||||

| Pouralizadeh et al., 2020 | Iran April | 441 | N-A | GAD-7 PHQ-9 | 10 10 | 100 % | 95,2 %, 420 | 171 (38,7) | 165 (37,5) | 3 | |||||||

| Prasad et al., 2020 | USA April | 347 | N-A | Mini-Z GAD-7 IES PHQ-2 | 3 5 26 3 | 71,50 % | 28,50 % | 908%, 315 | 241 (69,5) | 79 (22,8) | 208 (60) | 104 (30) | 327 (94,2) | ASD : 2 Depression : 3 Anxiety : 3 Stress : 3 Burn Out : 3 | |||

| Que et al., 2020 | Chine February | 2285 | N-A | GAD7 PHQ-9 ISI | 10 10 15 | 78% | 9% | 13 % | 69 %, 1577 | 1052 (46,04) | 1014 (44,37) | 657 (28,75) | 4 | ||||

| Ruiz‐Fernández et al., 2020 | Spain March April | 506 | N-A | ProQoL/Burn Out | 19 | 21,30 % | 78,70 % | 76,7%, 388 | 425 (84) | 3 | |||||||

| Sahin et al., 2020 | Turkey April May | 931 | N-A | PHQ-9 GAD-7 ISI IES-R | 10 5 10 24 | 61,80 % | 27,10 % | 66 %, 614 | 559 (60) | 722 (77,6) | 711 (76,4) | 469 (50,4) | 4 | ||||

| Sandesh et al., 2020 | Pakistan May | 112 | N-A | DASS-21 | N-A | N-A | N-A | N-A | 42,9 %, 48 | 96 (85,7) | 81 (72,3) | 101 (90,1) | 1 | ||||

| Sanghavi et al., 2020 | Portugal April | 29 | 78,00 % | BDI-II | 14 | 100 % | 62 %, 18 | 8 (28) | 4 | ||||||||

| Shah et al., 2020 | UK N-A | 207 | N-A | PHQ-2 GAD-2 | 3 3 | 100 % | 81,1 %, 168 | 51 (24,6) | 33 (15,9) | 2 | |||||||

| Shechter et al., 2020 | USA April | 657 | 13,70 % | PC-PTSD PHQ-2 GAD-2 | 3 3 3 | 52,40 % | 47,60 % | 70 %, 460 | 217 (33) | 315 (48) | 374 (57) | 4 | |||||

| Si et al., 2020 | China February-March | 863 | 76,00 % | IES-6 DASS-21 | 10 N-A | 43,70 % | 24,40 % | 70,7 %, 610 | 120 (13,9) | 117 (13,6) | 347 (40,2) | 74 (8,6) | PTSD : 5 DASS : 4 | ||||

| Skoda et al., 2020 | Germany March | 2224 | N-A | GAD-7 | 10 | 22,10 % | 67,90 % | 10 % | 76 %, 1690 | 211 (9,5) | 4 | ||||||

| Song et al., 2020 | China February-March | 14825 | N-A | CES-D PCL-5 | 16 33 | 41,10 % | 58,90 % | 64,3 %, 9532 | 3736 (25,2) | 1349 (9,1) | 4 | ||||||

| Stojanov et al., 2020 | Serbia N-A | 201 | 63.0% | GAD-7 SDS | 10 60 | 49% | 61 % | 65.67 %, 132 | 76 (37.6) | 32 (15.78) | 3 | ||||||

| Suryavanshi et al., 2020 | India May | 197 | 24,00 % | PHQ-9 GAD-7 | 5 5 | 63 % | 24 % | 13 % | 51 %, 99 | 99 (50) | 93 (47) | 3 | |||||

| Tu et al., 2020 | Chine February | 100 | 100,00 % | PSQI GAD-7 PHQ-9 | 7 4 4 | 100 % | 100 %, 100 | 46 (46) | 40 (40) | 60 (60) | 3 | ||||||

| Uyaroğlu et al., 2020 | Turkey April | 113 | N-A | GAD-7 | 5 | 100 % | 46,9 %, 53 | 56 (49,6) | 3 | ||||||||

| Vafaei et al., 2020 | Iran March | 599 | N-A | PHQ-9 | 5 | 54,10 % | 45,9 % (+ midwives) | 100 %, 599 | 407 (67,9) | 3 | |||||||

| Wang et al., 2020 | Chine February-March | 202 | 96,00 % | PCL-C | 38 | 100 % | 88 %, 178 | 34 (16,83) | 4 | ||||||||

| Huang et al., 2020 | China February | 1045 | 80,10 % | HADS -depression -anxiety ISI | 11 11 15 | 14,30 % | 74 % | 11,70 % | 85,8 %, 897 | 209 (20) | 142 (13,6) | 109 (10,4) | 5 | ||||

| Xiong et al., 2020 | China February | 223 | 61,80 % | GAD-7 PHQ-9 | 5 5 | 100 % | 97,3 %, 217 | 91 (40,8) | 59 (26,4) | 4 | |||||||

| Yang et al., 2020 | China February | 449 | N-A | SAS | N-A | 63,50 % | 36,50 % | N-A | 131 (29,18) | 1 | |||||||

| Yin et al., 2020 | China February | 371 | PCL-5 | 33 | 18,10 % | 71,20 % | 10,20 % | 61,5 %, 228 | 14 (3,8) | 3 | |||||||

| Zhan et al., 2020 | Chine March | 2667 | N-A | GAD-7 PHQ-9 CPSS | N-A N-A N-A | 100 % | 96,96 %, 2586 | 1062 (39,82) | 1458 (54,65) | 1654 (62) | 3 | ||||||

| Zhang et al., 2020a, 2020b | China March | 2182 | N-A | ISI PHQ-2 GAD-2 SCL-90-R - Psychosomatic - OCS - Phobic anxiety | 8 3 3 2 2 2 | 31,20 % | 11,30 % | 57,50 % | 64,2 %, 1401 | 227 (10,4) | 231 (10,6) | 740 (33,9) | 4 | ||||

| Zhang et al., 2020a, 2020b | China January February | 1563 | N-A | ISI PHQ-9 GAD-7 IES-R | 8 5 5 26 | 29 % | 63 % | 8 % | 82,7 %, 1293 | 699 (44,7) | 792 (50,7) | 585 (37,4) | 564 (36,1) | ASD : 3 Depression : 4 Anxiety : 4 Sleep disorder : 4 | |||

| Zhou et al., 2020 | China February | 1931 | N-A | PSQI | 7 | 16,40 % | 83,60 % | 85,4 %, 1843 | 355 (18,4) | 4 | |||||||

| Zhu et al., 2020 | China February | 165 | N-A | SAS SDS | 50 50 | 47,90 % | 52,10 % | 83 %, 137 | 33 (20) | 73 (44,2) | 3 | ||||||

| Zhu, Xu et al., 2020 | China February | 5062 | 77,10 % | PHQ-9 GAD-7 IES-R | 10 8 33 | 19,80 % | 67,50 % | 12,70 % | 85 %, 4304 | 1218 (24,1) | 681(13,5) | 1509 (29,8) | 5 | ||||

Abreviations : No : number; PTSD : Post Traumatic Stress Disorder ; ASD : Acute Stress Syndrom ; N-A : non applicable ; AIS : Athens Insomnia Scale; SCL-90-R : Symptom Check List-90-revised; GHQ : General Health Questionnaire; ProQOl : Professional Quality of Life Scale; SAS : Statistical Anxiety Scale ; SDS : Statistical Depression Scale ; DASS : Depression Anxiety Stress Scale ; PHQ : Patient Health Questionnaire ; GAD : General Anxiety Disorder ; ISI : Insomnia Severity Index ; IES : Impact of Event Revised; IES-R : Impact of Event Scale Revised ; PCL-C : PTSD Checklist-Civilian ; CES-D : Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depressions Scale ; PCL : PTSD Checklist ; HADS : Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ; PC-PTSD : 4-item Primary Care PTSD screen ; BDI : Beck Depression Inventory ; MBI : Maslach Burnout Inventory ; EE : emotional exhaustion; DP : depersonalization; PSQI : Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index ; PSS : Perceived Stress Scale ; STAI Y1 : State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Form Y1 ; BDI-II : Beck Depression Inventory ; SASRQ : Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire ; HADS : Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ; CPSS : Chines Perceived Stress Scale ; HAMA : Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HAMD : Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

A meta-analysis (Table S2, supplementary materials) was performed on the whole sample (heterogeneous quality), then focused on high-quality studies (score ≥ 4/5): 22 for anxiety, 25 for depression, 9 for ASD and PTSD, and 10 for sleep disorders. The results of the risk of bias assessment are provided in Table S2. There was no publication bias when focusing on studies assessed ≥ 4/5 (funnel plot and Egger’s test p-value > 0.1). For each pooled prevalence presented in this research, there was no significant change in the degree of heterogeneity even if an attempt was done to exclude the expected outliers or according quality criteria ≥ 4/5.

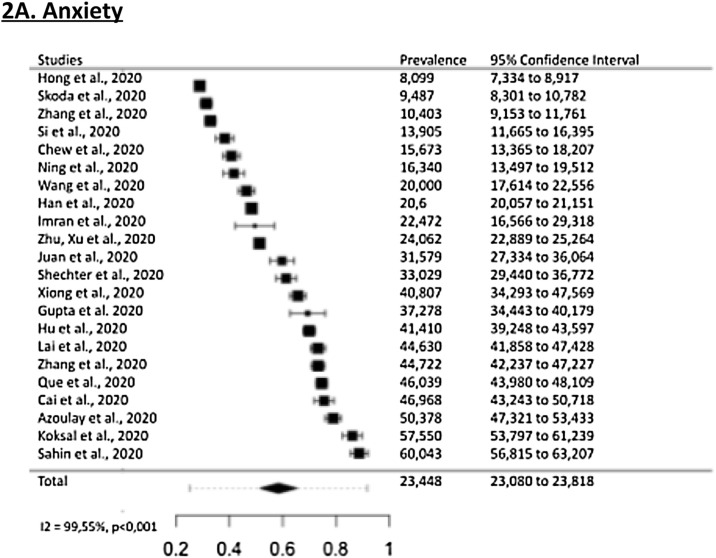

3.3. Anxiety

The pooled prevalence of anxiety was 30,0 % (95 % CI, 24,2 - 37,0), in a total of 51 942 participants, with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 99,55 %, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2 A). No factor explained high heterogeneity (criteria ≥ 4/5, female or nurse proportion, location, scale, sample size) (supplementary materials).

Fig. 2.

A. Forest plots of the prevalence of symptoms of anxiety in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The figure shows the results of the meta-analysis of the studies using random-effect models after Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation. Error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals.

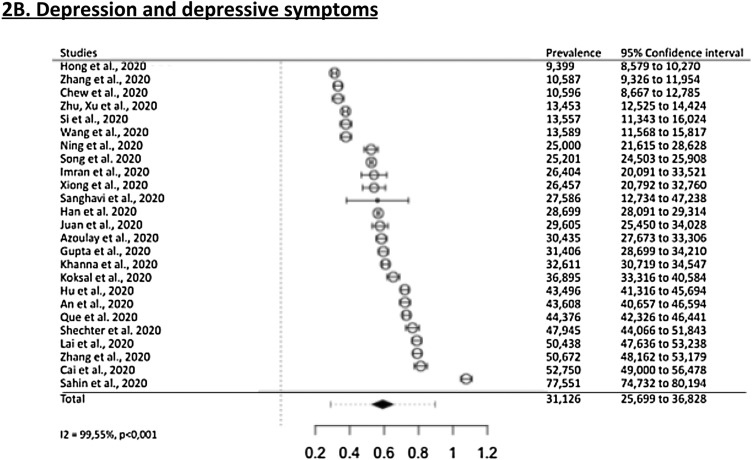

B. Forest plots of the prevalence of symptoms of depression in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The figure shows the results of the meta-analysis of the studies using random-effect models after Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation. Error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals

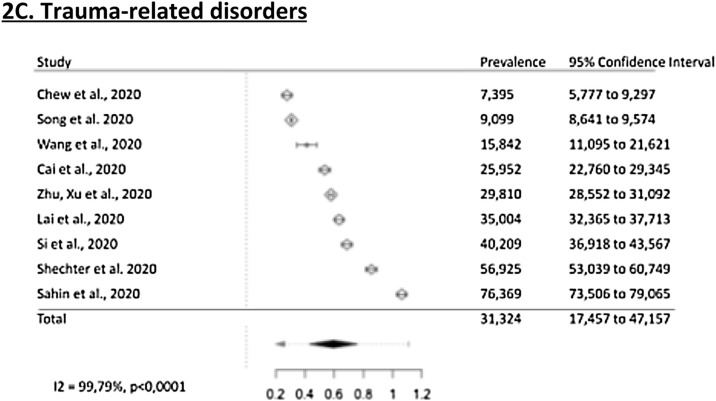

C. Forest plots of the prevalence of trauma-related symptoms in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The figure shows the results of the meta-analysis of the studies using random-effect models after Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation. Error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals

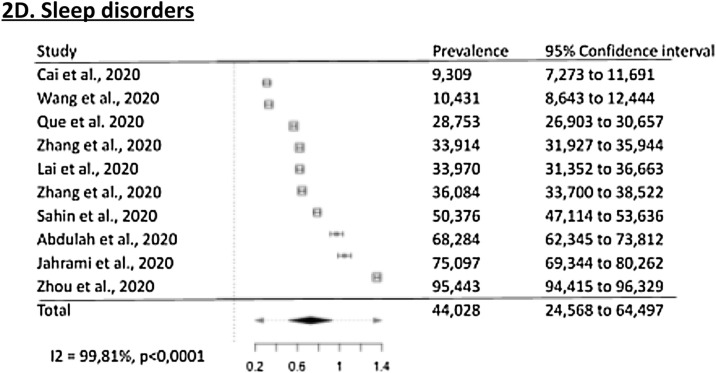

D. Forest plots of the prevalence of symptoms of sleep disorders in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The figure shows the results of the meta-analysis of the studies using random-effect models after Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation. Error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals.

3.4. Depression and depressive symptoms

The pooled prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms was 31,1 % (95 % CI, 25,7 - 36,8), in a total of 68 030 participants, with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 99,55 %, p < .001). (Fig. 2B). No factor explained high heterogeneity in subgroup analyses and metaregressions (criteria ≥ 4/5, female or nurse proportion, location, scale, sample size) (supplementary materials).

3.5. Post-Traumatic Stress and Acute Stress

The pooled prevalence of psychotraumatic disorders was 31,4 % (95 % CI - 17,5 - 47.3), out of 25 412 participants, with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 99,79 %, p < .001). No factor explained high heterogeneity (criteria ≥ 4/5, female or nurse proportion, location, scale, sample size) (supplementary materials). Sensitivity analysis identified Sahin et al. (Şahin et al., 2020) as a possible outlier.

Focusing on acute stress, the pooled prevalence was 56,5% (95 % CI, 29.9–82.3), among 3 studies (quality score ≥ 4/5), in a total of 2 845 participants, with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 99,56 %, p < .001). The estimated pooled prevalence of post-traumatic stress in 6 studies was 21.5 % (95 %CI, 11.2–31.8), I2 = 99.62 %.

3.6. Sleep disorders

The pooled prevalence of sleep disorders was 44,0 % (95 % CI, 24,568−64,497), out of 12 428 participants, with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 99,81 %, p < .001) (Fig. 2D). These studies used 3 different scales, mostly the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), using different cut-offs, but the use of this scale was not identified as a moderator in the metaregression. Subgroup analyses and metagressions identified two moderators: the female proportion (p < 0.001, associated with fewer sleep disorders), and the location (China studies being associated with lower prevalence). Nurse proportion, location, scale, and sample size did not explain high heterogeneity (supplementary materials).

3.7. Effect of time

For anxiety, depression, trauma, and sleep disorders, we calculated the time effect on the prevalence of each outcome, including all studies (quality ≥ 4/5) or only studies in China (to limit the effect of location). The results suggested increased sleep disorders throughout time (22,8% (95 % IC, 13,9–31,7) for january-february period versus 568% (95 % IC, 38,4–75,2) for march-may). No significant result was observed for other outcomes (supplementary materials). Overall, due to the scarcity of data, we could not conclude on any time effect on these outcomes among healthcare workers.

3.8. Assessment of psychiatric comorbidities

Three studies reported the ratio of comorbidity among these four psychiatric outcomes (anxiety, depression, trauma-related, and sleep disorders), using validated scales (within studies quality ≥ 4/5). Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2020a), find out that 26,2% had both insomnia (assessed with the ISI scale) and moderate to severe symptoms of acute stress (IES-R), 14,3 % had both insomnia and moderate to severe symptoms of depression (PHQ-9) and 10,8 % had both insomnia and moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety (GAD-7). Koksal et al. (Koksal et al., 2020), report that 34,0 % had both depression (HADS) and anxiety (HADS). Zhu, Xu et al. (Zhu, Xu et al. 2020), report that 20,3 % cumulated at least two outcomes: 7,5 % had both acute stress (IES-R) and anxiety (GAD-7), 1,5 % had both acute stress and depression (PSQ-9), 0,9 % had both anxiety and depression and 10,4 % had acute stress, depression, and anxiety.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis reports a high prevalence of anxiety, depression, trauma-related, and sleep disorders among caregivers in practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, there is a major concern for the mental health of caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as in potential future health crises.

During the MERS and SARS epidemics, a high rate of severe emotional distress and psychiatric symptoms among caregivers was also found, but studies were sporadic and do not allow any comparison to our results (Lee et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2009). Earlier reviews and meta-analyses of HCWs’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic reported high levels of anxiety (23.2 % (95 % CI, 17.8–29.1) (Pappa et al., 2020); 26 % (95 % CI, 18 %–34 %) (Luo et al., 2020) and depression (22.8 % (95 % CI, 15.1–31.5) (Pappa et al., 2020); 25 % (95 %CI, 19 %–32 %)(Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020)). These results, similar to ours, support the external validity of our study. Given the significant and steady increase in the number of publications since these papers, our review provides updated (versus researches until April in previous papers) and exhaustive data on this topic. The variation in prevalence estimation may be due to various factors including time-effect of the pandemic on the exhaustion of HCWs, and accumulation of adverse experiences.

In the general population, some meta-analyses also found similar prevalences of anxiety (31.9 % (95 % CI, 27.5–36.7)), depression (33.7 % (95 % IC, 27.5–40.6)), post-traumatic stress symptoms (23.9 % (95 % CI, 14.01–33.76), and sleep problems (32.3 % (95 % CI, 25.3–40.2) (Cooke et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020a; Jahrami et al., 2020)

Post-traumatic stress and acute stress among HCWs may be due to the high amounts of brutal and unexpectable deaths they are exposed to. Experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of traumatic events are potentially traumatic (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In the emergency context of the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers are exposed to potentially traumatic or stress factors: unpredictability of daily caseloads, having to frequently manage patients and their families’ expectations in unexpected situations, the making-decision burden, high daily fatality rates, and constant updates of hospital procedures (Carmassi et al., 2020; WJEM, 2020.; Fjeldheim et al., 2014). Lack of social support is also an important adverse factor for HCWs’ mental health enhanced by quarantine, perceived stigmatization, and fear of contaminating relatives (Carmassi et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Serrano-Ripoll et al., 2020).

Sleep problems may be associated with other disorders, such as PTSD, depression, anxiety in a bidirectional relationship (Salari et al., 2020b; Sanghera et al., 2020; Geoffroy et al., 2020b). Two factors may contribute to sleep problems among HCWs: the high workload (including night work, which modifies circadian rhythms) and stress-induced sleep problems (Lucchini et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020b).

4.2. Implications for public health

Mental health problems experienced by HCWs decrease productivity (Kim et al., 2018). Moreover, some studies have found a reduced quality of care when the psychological health of HCWs is impaired (Tawfik et al., 2019; Pereira-Lima et al., 2019), highlighting the potential impact of non-addressing this issue. The frequent occurrence of psychiatric symptoms and psychological suffering among HCWs during this pandemic should trigger measures to address the HCWs ongoing suffering, as they may have specific work-related stress factors. High work pressure and workload, uncertainty about a poorly known and deadly disease, dehumanized healthcare working conditions in protective personal equipment, shorter time for social interactions with patients, numerous deaths, and family visit bans, are examples of factors that may specifically contribute to the psychological suffering of HCWs (Guessoum et al., 2020; Mallet et al., 2020b).

In these unique situations, HCWs develop coping behaviors, such as physical exercise or talk therapy (Shechter et al., 2020). HCWs may experience positive feelings such as an increased sense of meaning (Shechter et al., 2020). However, healthcare managers need to take steps to protect the mental well-being of staff (Greenberg et al., 2020). Since the beginning of the pandemic, China set up online and telephone consultations without time restrictions (Zhang et al., 2020b) and information and prevention materials for caregivers (Bao et al., 2020), which was quickly followed by other countries (D’Agostino et al., 2020). In France, some university hospitals developed specific hotlines and programs for psychological support of HCWs during the pandemic (relaxation, empathetic support, soothing and low-impact physical activities, assistance of mental health professionals) (Lefèvre et al., 2020; Geoffroy et al., 2020a). In the UK, a team developed a digital learning and support package on psychological well-being (Blake et al., 2020). Such interventions need to be evaluated (Viswanathan et al., 2020).

4.3. Implications for research

This study presents several limitations. The reviewed studies have been conducted in real-world conditions, in the present context of global pandemic. In such a context of emergency, some studies had weak methods and could not be included in the final meta-analysis, in order to decrease clinical and methodological heterogeneity. The heterogeneity of methods in the different studies makes comparisons difficult (assessment scales, various thresholds). In addition, the study populations varied. For example, some studies included nurses exclusively; others included administrative staff and technicians. We tried to overcome these limitations by conducting subgroup analyses and meta-regressions and thus, examining potential sources of heterogeneity (female or nurse proportion, location, scale, sample size). Homogenizing future studies ‘methods would allow better comparability across studies and countries. Moreover, most studies were cross-sectional. There is a need for longitudinal studies. Longitudinal studies are necessary to understand the time effect on these psychiatric outcomes. Indeed, there are limits in estimating the time effect by comparing different cross-sectional studies in different locations. Most studies were conducted with auto questionnaires, without clinical diagnostic confirmation. However, all the included studies have used validated screening tools. Third, the small number of studies included in some of the subgroups may have biased some of the subgroup analysis results (e.g acute stress). Fourth, most studies assessed large countries (US, China…). Consequently, although we performed metaregression according to large location, the results may not be generalizable to HCWs in other countries (and the location was identified as a moderator of the estimated prevalence of sleep disorders). Finally, no evidence of publication bias was found with the Egger test but the exclusion of grey literature and unpublished data may have introduced selection bias to this analysis.

Few studies reported the prevalence of comorbidity of these outcomes among healthcare workers, despite being clinically pertinent data. Reporting comorbidity of psychiatric outcomes would be indicated in all future studies. Indeed, quality of life is significantly impaired with increasing comorbidity (Watson et al., 2011).

As a supplementary concern regarding HCWs’ health, focusing on substance abuse and suicidal ideations would be relevant. There are serious concerns regarding substance abuse in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic (Mallet et al., 2020a).

4.4. Conclusion

This review and meta-analysis provides a relevant picture of the mental health status of HCWs across the world during the COVID-19 pandemic: they endure high levels of psychiatric symptoms, including anxiety, depression, acute stress, post-traumatic stress, and sleep disorders. For HCWs’ wellbeing and the quality of care during the pandemic, targeted prevention and psychological support should be provided to this population during such situations.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributions

SBG designed the study. Two authors SBG and MM screened the titles and abstracts of the studies based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. They also collected the full texts, evaluated the eligibility of the studies for final inclusion, assessed the quality of the study. SBG drafted the manuscript. JM commented on the review, performed the meta-analysis and drafted the manuscript. CD suggested improvements, reviewed and drafted the manuscript. MRM supervised the whole research and drafted the manuscript. All authors analyzed/interpreted the data and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors declare none.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.03.024.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Ades A.E., Lu G., Higgins J.P.T. The interpretation of random-effects meta-analysis in decision models. Med. Decis. Mak. 2005 doi: 10.1177/0272989x05282643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Pub.; 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) [Google Scholar]

- Bao Yanping, Sun Yankun, Meng Shiqiu, Shi Jie, Lu Lin. 2019-nCoV epidemic: address mental health care to empower society. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):e37–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30309-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien C.H., Vallières A., Morin C.M. Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake Holly, Bermingham Fiona, Johnson Graham, Tabner Andrew. Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a digital learning package. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(9) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17092997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmassi Claudia, Foghi Claudia, Dell’Oste Valerio, Cordone Annalisa, Bertelloni Carlo Antonio, Bui Eric, Dell’Osso Liliana. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: what can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292(October) doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke Jessica E., Eirich Rachel, Racine Nicole, Madigan Sheri. Prevalence of posttraumatic and general psychological stress during COVID-19: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292(October) doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer Mark, Bell Richard, Failla Salvina. Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale—revised. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombie I.K. The Pocket Guide to Critical Appraisal: A Handbook for Health Care Professionals. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; London: 1996. Appraising review papers; pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino Armando, Demartini Benedetta, Cavallotti Simone, Gambini Orsola. Mental health services in Italy during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(5):385–387. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjeldheim Celine B., Nöthling Jani, Pretorius Karin, Basson Marina, Ganasen Keith, Heneke Robin, Cloete Karen J., Seedat Soraya. Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder and the effect of explanatory variables in paramedic trainees. BMC Emerg. Med. 2014;14(April):11. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-14-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoffroy Pierre A., Le Goanvic V.éronique, Sabbagh Olivier, Richoux Charlotte, Weinstein Aviv, Dufayet Geoffrey, Lejoyeux Michel. Psychological support system for hospital workers during the Covid-19 outbreak: rapid design and implementation of the Covid-Psy hotline. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11(May):511. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoffroy Pierre A., Tebeka Sarah, Blanco Carlos, Dubertret Caroline, Le Strat Yann. Shorter and longer durations of sleep are associated with an increased twelve-month prevalence of psychiatric and substance use disorders: findings from a nationally representative survey of US adults (NESARC-III) J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;124(May):34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg Neil, Docherty Mary, Gnanapragasam Sam, Wessely Simon. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during Covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368(March):m1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guessoum Sélim Benjamin, Moro Marie Rose, Mallet Jasmina. The COVID-19 pandemic: do not turn the health crisis into a humanity crisis. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22(4) doi: 10.4088/PCC.20com02709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAS, and Collège de la Haute Autorité de Santé (France) 2020. Réponse Rapide Dans Le Cadre Du COVID-19 - Souffrance Des Professionnels Du Monde de La Santé: Prévenir, Repérer, Orienter.http://cn2r.fr/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/rr_souffrance_des_professionnels_du_monde_la_sante.pdf May 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins Julian P.T., Thompson Simon G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins Julian P.T., Thomas James, Chandler Jacqueline, Cumpston Miranda, Li Tianjing, Page Matthew J., Welch Vivian A. John Wiley & Sons; 2019. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Chaolin, Wang Yeming, Li Xingwang, Ren Lili, Zhao Jianping, Hu Yi, Zhang Li, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahrami Haitham, BaHammam Ahmed S., Bragazzi Nicola Luigi, Saif Zahra, Faris Moezalislam, Vitiello Michael V. Sleep problems during COVID-19 pandemic by population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2020 doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8930. October. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khusid Johnathan A., Weinstein Corey S., Becerra Adan Z., Kashani Mahyar, Robins Dennis J., Fink Lauren E., Smith Matthew T., Weiss Jeffrey P. Well‐being and education of urology residents during the COVID‐19 pandemic: results of an American national survey. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Min-Seok, Kim Taeshik, Lee Dongwook, Yook Ji-Hoo, Hong Yun-Chul, Lee Seung-Yup, Yoon Jin-Ha, Kang Mo-Yeol. Mental disorders among workers in the healthcare industry: 2014 national health insurance data. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018;30(May):31. doi: 10.1186/s40557-018-0244-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koksal Ersin, Dost Burhan, Terzi Özlem, Ustun Yasemin B., Özdin Selçuk, Bilgin Sezgin. Evaluation of depression and anxiety levels and related factors among operating theater workers during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. J. Perianesthesia Nurs. 2020;35(5):472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2020.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy Yuvaraj, Nagarajan Ramya, Saya Ganesh Kumar, Menon Vikas. Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293(November) doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Sang Min, Kang Won Sub, Cho Ah-Rang, Kim Tae, Park Jin Kyung. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr. Psychiatry. 2018;87(November):123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefèvre Hervé, Stheneur Chantal, Cardin Charlotte, Fourcade Lola, Fourmaux Christine, Tordjman Elise, Touati Marie, et al. The bulle: support and prevention of psychological decompensation of health care workers during the trauma of the COVID-19 epidemic. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;(September) doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gotzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P.A., Clarke M., Devereaux P.J., Kleijnen J., Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Xinhua, Kakade Meghana, Fuller Cordelia J., Fan Bin, Fang Yunyun, Kong Junhui, Guan Zhiqiang, Wu Ping. Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr. Psychiatry. 2012;53(1):15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchini Alberto, Iozzo Pasquale, Bambi Stefano. Nursing workload in the COVID-19 era. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lung For-Wey, Lu Yi-Ching, Chang Yong-Yuan, Shu Bih-Ching. Mental symptoms in different health professionals during the SARS attack: a follow-up study. Psychiatr. Q. 2009;80(2):107–116. doi: 10.1007/s11126-009-9095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Min, Guo Lixia, Yu Mingzhou, Jiang Wenying, Wang Haiyan. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291(September) doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet Jasmina, Dubertret Caroline, Le Strat Yann. Addictions in the COVID-19 era: current evidence, future perspectives a comprehensive review. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2020;(August) doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet Jasmina, Le Strat Yann, Colle Maxime, Cardot Hélène, Dubertret Caroline. Sustaining the unsustainable: rapid implementation of a support intervention for bereavement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2020;(December) doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder Robert, Hunter Jonathan, Vincent Leslie, Bennett Jocelyn, Peladeau Nathalie, Leszcz Molyn, Sadavoy Joel, Verhaeghe Lieve M., Steinberg Rosalie, Mazzulli Tony. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003;168(10):1245–1251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller John J. The inverse of the freeman – Tukey double arcsine transformation. Am. Stat. 1978 doi: 10.1080/00031305.1978.10479283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NIH, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute . 2020. Study Quality Assessment Tools.https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools Accessed December 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pappa Sofia, Ntella Vasiliki, Giannakas Timoleon, Giannakoulis Vassilis G., Papoutsi Eleni, Katsaounou Paraskevi. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88(August):901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Lima Karina, Mata Douglas A., Loureiro Sonia R., Crippa JoséA., Bolsoni L.ívia M., Sen Srijan. Association between physician depressive symptoms and medical errors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(11) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şahin Mustafa K.ürşat, Aker Servet, Şahin Gülay, Karabekiroğlu Aytül. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, distress and insomnia and related factors in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. J. Community Health. 2020;45(6):1168–1177. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00921-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari Nader, Hosseinian-Far Amin, Jalali Rostam, Vaisi-Raygani Aliakbar, Rasoulpoor Shna, Mohammadi Masoud, Rasoulpoor Shabnam, Khaledi-Paveh Behnam. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global. Health. 2020;16(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari Nader, Khazaie Habibolah, Hosseinian-Far Amin, Ghasemi Hooman, Mohammadi Masoud, Shohaimi Shamarina, Daneshkhah Alireza, Khaledi-Paveh Behnam, Hosseinian-Far Melika. The prevalence of sleep disturbances among physicians and nurses facing the COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global. Health. 2020;16(1):92. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00620-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghera Jaspinder, Pattani Nikhil, Hashmi Yousuf, Varley Kate F., Cheruvu Manikandar Srinivas, Bradley Alex, Burke Joshua R. The impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the mental health of healthcare workers in a hospital Setting-a systematic review. J. Occup. Health. 2020;62(1) doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Ripoll Maria J., Meneses-Echavez Jose F., Ricci-Cabello Ignacio, Fraile-Navarro David, Fiol-deRoque Maria A., Pastor-Moreno Guadalupe, Castro Adoración, Ruiz-Pérez Isabel, Campos Rocío Zamanillo, Gonçalves-Bradley Daniela C. Impact of viral epidemic outbreaks on mental health of healthcare workers: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;277(December):347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt Tait D., Ripp Jonathan, Brown Marie, Sinsky Christine A. 2020. Caring for Health Care Workers during Crisis - Creating a Resilient Organization.https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-05/caring-for-health-care-workers-covid-19.pdf August 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shaukat Natasha, Ali Daniyal Mansoor, Razzak Junaid. Physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a scoping review. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2020;13(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s12245-020-00299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechter Ari, Diaz Franchesca, Moise Nathalie, Edmund Anstey D., Ye Siqin, Agarwal Sachin, Birk Jeffrey L., et al. Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among new york healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2020;66(September):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer Robert L., Kroenke Kurt, Williams Janet B.W., Löwe Bernd. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoorthy Mamidipalli Sai, Pratapa Sree Karthik, Mahant Supriya. Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 Pandemic-a review. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;51(June) doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Niuniu, Wei Luoqun, Shi Suling, Jiao Dandan, Song Runluo, Ma Lili, Wang Hongwei, et al. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2020;48(6):592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik Daniel S., Scheid Annette, Profit Jochen, Shanafelt Tait, Trockel Mickey, Adair Kathryn C., Bryan Sexton J., Ioannidis John P.A. Evidence relating health care provider burnout and quality of care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019;171(8):555–567. doi: 10.7326/M19-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomaier Lauren, Teoh Deanna, Jewett Patricia, Beckwith Heather, Parsons Helen, Yuan Jianling, Blaes Anne H., Lou Emil, Hui Jane Yuet Ching, Vogel Rachel I. Emotional health concerns of oncology physicians in the United States: fallout during the COVID-19 pandemic. PloS One. 2020;(June) doi: 10.1101/2020.06.11.20128702. medRxiv : The Preprint Server for Health Sciences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan Ramaswamy, Myers Michael F., Fanous Ayman H. Support groups and individual mental health care via video conferencing for frontline clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychosomatics. 2020;61(5):538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson Hunna J., Swan Amanda, Nathan Paula R. Psychiatric diagnosis and quality of life: the additional burden of psychiatric comorbidity. Compr. Psychiatry. 2011;52(3):265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, World Health Organization, “Weekly Operational Update - 14 December 2020.” n.d. Accessed December 14, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update---14-december-2020.

- WJEM . 2020. World Journal of Emergency Medicine. n.d. Accessed December 4, 2020. http://www.wjem.com.cn/default/articlef/index/id/213. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Ping, Fang Yunyun, Guan Zhiqiang, Fan Bin, Kong Junhui, Yao Zhongling, Liu Xinhua, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can. J. Psychiatry. 2009;54(5):302–311. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangrillo Alberto, Beretta Luigi, Silvani Paolo, Colombo Sergio, Scandroglio Anna Mara, Dell’Acqua Antonio, Fominskiy Evgeny, et al. Fast reshaping of intensive care unit facilities in a large metropolitan hospital in Milan, Italy: facing the COVID-19 pandemic emergency. Crit. Care Resusc. J. Australas. Acad. Crit. Care Med. 2020;22(2):91–94. doi: 10.51893/2020.2.pov1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Xiantao, Zhang Yonggang, Kwong Joey S.W., Zhang Chao, Li Sheng, Sun Feng, Niu Yuming, Liang Du. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J. Evid. Med. 2015;8(1):2–10. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Chenxi, Yang Lulu, Liu Shuai, Ma Simeng, Wang Ying, Cai Zhongxiang, Du Hui, et al. Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11(April):306. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Jun, Wu Weili, Zhao Xin, Zhang Wei. Recommended psychological crisis intervention response to the 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia outbreak in China: a model of West China Hospital. Precis. Clin. Med. 2020;3(1):3–8. doi: 10.1093/pcmedi/pbaa006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Zhou, Xu Shabei, Wang Hui, Liu Zheng, Wu Jianhong, Li Guo, Miao Jinfeng, et al. COVID-19 in Wuhan: sociodemographic characteristics and hospital support measures associated with the immediate psychological impact on healthcare workers. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;24(July) doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AlAteeq D.A., Aljhani S., Althiyabi I., Majzoub S. Mental health among healthcare providers during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2020;13:1432–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An Y., Yang Y., Wang A., Li Y., Zhang Q., Cheung T., Ungvari G.S., Qin M.-Z., An F.-R., Xiang Y.-T. Prevalence of depression and its impact on quality of life among frontline nurses in emergency departments during the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;276:312–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apisarnthanarak A., Apisarnthanarak P., Siripraparat C., Saengaram P., Leeprechanon N., Weber D.J. Impact of anxiety and fear for COVID-19 toward infection control practices among Thai healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41:1093–1094. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arafa A., Mohammed Z., Mahmoud O., Elshazley M., Ewis A. Depressed, anxious, and stressed: What have healthcare workers on the frontlines in Egypt and Saudi Arabia experienced during the COVID -19 pandemic? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.080. S0165032720327762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay E., Cariou A., Bruneel F., Demoule A., Kouatchet A., Reuter D., Souppart V., Combes A., Klouche K., Argaud L., Barbier F., Jourdain M., Reignier J., Papazian L., Guidet B., Géri G., Resche-Rigon M., Guisset O., Labbé V., Mégarbane B., Van Der Meersch G., Guitton C., Friedman D., Pochard F., Darmon M., Kentish-Barnes N. The FAMIREA study group (2020) Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression and Peritraumatic Dissociation in Critical Care Clinicians Managing COVID-19 Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2568OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badahdah A., Khamis F., Al Mahyijari N., Al Balushi M., Al Hatmi H., Al Salmi I., Albulushi Z., Al Noomani J. The mental health of health care workers in Oman during the COVID -19 pandemic. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020939596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z., Cui Q., Liu Z., Li J., Gong X., Liu J., Wan Z., Yuan X., Li X., Chen C., Wang G. Nurses endured high risks of psychological problems under the epidemic of COVID-19 in a longitudinal study in Wuhan China. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2020;131:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., Tan B.Y.Q., Jing M., Goh Y., Ngiam N.J.H., Yeo L.L.L., Ahmad A., Ahmed Khan F., Napolean Shanmugam G., Sharma A.K., Komalkumar R.N., Meenakshi P.V., Shah K., Patel B., Chan B.P.L., Sunny S., Chandra B., Ong J.J.Y., Paliwal P.R., Wong L.Y.H., Sagayanathan R., Chen J.T., Ying Ng A.Y., Teoh H.L., Tsivgoulis G., Ho C.S., Ho R.C., Sharma V.K. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID -19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Tella M., Romeo A., Benfante A., Castelli L. Mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID ‐19 pandemic in Italy. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jep.13444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkholy H., Tawfik F., Ibrahim I., Salah El-din W., Sabry M., Mohammed S., Hamza M., Alaa M., Fawzy A.Z., Ashmawy R., Sayed M., Omar A.N. Mental health of frontline healthcare workers exposed to COVID -19 in Egypt: A call for action. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020960192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Prasad A.S., Dixit P.K., Padmakumari P., Gupta S., Abhisheka K. Survey of prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms among 1124 healthcare workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic across India. Medical Journal Armed Forces India. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.07.006. S0377123720301325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L., Wong F.K.Y., She D.L.M., Li S.Y., Yang Y.F., Jiang M.Y., Ruan Y., Su Q., Ma Y., Chung L.Y.F. Anxiety and Depression of Nurses in a North West Province in China During the Period of Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Outbreak. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jnu.12590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S., Ai M., Xu X., Wang W., Chen J., Zhang Q., Wang L., Kuang L. Immediate psychological impact on nurses working at 42 government-designated hospitals during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A cross-sectional study. Nursing Outlook. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2020.07.007. S0029655420306102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D., Kong Y., Li W., Han Q., Zhang X., Zhu L.X., Wan S.W., Liu Z., Shen Q., Yang J., He H.-G., Zhu J. Frontline nurses’ burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: A large-scale cross-sectional study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;24:100424. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imran N., Masood H.M.U., Ayub M., Gondal K.M. Psychological impact of COVID -19 pandemic on postgraduate trainees: a cross-sectional survey. Postgrad Med J. 2020 doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan Y., Yuanyuan C., Qiuxiang Y., Cong L., Xiaofeng L., Yundong Z., Jing C., Peifeng Q., Yan L., Xiaojiao X., Yujie L. Psychological distress surveillance and related impact analysis of hospital staff during the COVID-19 epidemic in Chongqing, China. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2020;103:152198. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanal P., Devkota N., Dahal M., Paudel K., Joshi D. Mental health impacts among health workers during COVID-19 in a low resource setting: a cross-sectional survey from Nepal. Global Health. 2020;16:89. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00621-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrague L.J., Santos J.A.A. COVID‐19 anxiety among front‐line nurses: Predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28:1653–1661. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., Cai Z., Hu J., Wei N., Wu J., Du H., Chen T., Li R., Tan H., Kang L., Yao L., Huang M., Wang H., Wang G., Liu Z., Hu S. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Chen Y., Lv J., Liu L., Zong S., Li H., Li H. Anxiety and related factors in frontline clinical nurses fighting COVID-19 in Wuhan. Medicine. 2020;99:e21413. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahendran K., Patel S., Sproat C. Psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on staff in a dental teaching hospital. Br Dent J. 2020;229:127–132. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-1792-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng K.Y.Y., Zhou S., Tan S.H., Ishak N.D.B., Goh Z.Z.S., Chua Z.Y., Chia J.M.X., Chew E.L., Shwe T., Mok J.K.Y., Leong S.S., Lo J.S.Y., Ang Z.L.T., Leow J.L., Lam C.W.J., Kwek J.W., Dent R., Tuan J., Lim S.T., Hwang W.Y.K., Griva K., Ngeow J. Understanding the Psychological Impact of COVID -19 Pandemic on Patients With Cancer, Their Caregivers, and Health Care Workers in Singapore. JCO Global Oncology. 2020:1494–1509. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning X., Yu F., Huang Q., Li X., Luo Y., Huang Q., Chen C. The mental health of neurological doctors and nurses in Hunan Province, China during the initial stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:436. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02838-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podder I., Agarwal K., Datta S. Comparative analysis of perceived stress in dermatologists and other physicians during national lock‐down and COVID ‐19 pandemic with exploration of possible risk factors: A web‐based cross‐sectional study from Eastern India. Dermatologic Therapy. 2020:33. doi: 10.1111/dth.13788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouralizadeh M., Bostani Z., Maroufizadeh S., Ghanbari A., Khoshbakht M., Alavi S.A., Ashrafi S. Anxiety and depression and the related factors in nurses of Guilan University of Medical Sciences hospitals during COVID-19: A web-based cross-sectional study. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences. 2020;13:100233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2020.100233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad A., Civantos A.M., Byrnes Y., Chorath K., Poonia S., Chang C., Graboyes E.M., Bur A.M., Thakkar P., Deng J., Seth R., Trosman S., Wong A., Laitman B.M., Shah J., Stubbs V., Long Q., Choby G., Rassekh C.H., Thaler E.R., Rajasekaran K. Snapshot Impact of COVID -19 on Mental Wellness in Nonphysician Otolaryngology Health Care Workers: A National Study. OTO Open. 2020:4. doi: 10.1177/2473974X20948835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que J., Shi L., Deng J., Liu J., Zhang L., Wu S., Gong Y., Huang W., Yuan K., Yan W., Sun Y., Ran M., Bao Y., Lu L. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in China. Gen Psych. 2020;33:e100259. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz‐Fernández M.D., Ramos‐Pichardo J.D., Ibáñez‐Masero O., Cabrera‐Troya J., Carmona‐Rega M.I., Ortega‐Galán Á.M. Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction, and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID‐19 health crisis in Spain. J Clin Nurs. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jocn.15469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandesh R., Shahid W., Dev K., Mandhan N., Shankar P., Shaikh A., Rizwan A. Impact of COVID -19 on the Mental Health of Healthcare Professionals in Pakistan. Cureus. 2020 doi: 10.7759/cureus.8974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghavi P.B., Au Yeung K., Sosa C.E., Veesenmeyer A.F., Limon J.A., Vijayan V. Effect of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic on Pediatric Resident Well-Being. Journal of Medical Education. 2020:7. doi: 10.1177/2382120520947062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah N., Raheem A., Sideris M., Velauthar L., Saeed F. Mental health amongst obstetrics and gynaecology doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a UK-wide study. European. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2020;253:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.07.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si M.-Y., Su X.-Y., Jiang Y., Wang W.-J., Gu X.-F., Ma L., Li J., Zhang S.-K., Ren Z.-F., Ren R., Liu Y.-L., Qiao Y.-L. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on medical care workers in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:113. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoda E.-M., Teufel M., Stang A., Jöckel K.-H., Junne F., Weismüller B., Hetkamp M., Musche V., Kohler H., Dörrie N., Schweda A., Bäuerle A. Psychological burden of healthcare professionals in Germany during the acute phase of the COVID -19 pandemic: differences and similarities in the international context. Journal of Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Fu W., Liu X., Luo Z., Wang R., Zhou N., Yan S., Lv C. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the Coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z., He J., Zhou N. Sleep quality and mood symptoms in conscripted frontline nurse in Wuhan, China during COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2020;99:e20769. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyaroğlu O.A., Başaran NÇ, Ozisik L., Karahan S., Tanriover M.D., Guven G.S., Oz S.G. Evaluation of the effect of COVID ‐19 pandemic on anxiety severity of physicians working in the internal medicine department of a tertiary care hospital: a cross‐sectional survey. Intern Med J. 2020 doi: 10.1111/imj.14981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vafaei H., Roozmeh S., Hessami K., Kasraeian M., Asadi N., Faraji A., Bazrafshan K., Saadati N., Kazemi Aski S., Zarean E., Golshahi M., Haghiri M., Abdi N., Tabrizi R., Heshmati B., Arshadi E. Obstetrics Healthcare Providers’ Mental Health and Quality of Life During COVID-19 Pandemic: Multicenter Study from Eight Cities in Iran. PRBM. 2020;13:563–571. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S256780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.-X., Guo H.-T., Du X.-W., Song W., Lu C., Hao W.-N. Factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder of nurses exposed to corona virus disease 2019 in China. Medicine. 2020;99:e20965. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H., Yi S., Lin Y. The Psychological Status and Self-Efficacy of Nurses During COVID -19 Outbreak: A Cross-Sectional Survey. INQUIRY. 2020:57. doi: 10.1177/0046958020957114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Zhang Y., Li S., Chen X. Risk factors for anxiety of otolaryngology healthcare workers in Hubei province fighting coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01928-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Y., Zhao S., Yuan J., Liu H., Liu Y., Gui L., Zheng H., Zhou Y., Qiu L., Chen J., Yu J., Li S. Prevalence and Influencing Factors on Fatigue of First-line Nurses Combating with COVID-19 in China: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. CURR MED SCI. 2020;40:625–635. doi: 10.1007/s11596-020-2226-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Further reading

Chen H, Sun L, Du Z, Zhao L, Wang L (2020) A cross‐sectional study of mental health status and self‐psychological adjustment in nurses who supported Wuhan for fighting against the COVID‐19. J Clin Nurs jocn.15444. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15444.

Cici R, Yilmazel G (2020) Determination of anxiety levels and perspectives on the nursing profession among candidate nurses with relation to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Perspect Psychiatr Care ppc.12601. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12601.

Elhadi M, Msherghi A, Elgzairi M, Alhashimi A, Bouhuwaish A, Biala M, Abuelmeda S, Khel S, Khaled A, Alsoufi A, Elmabrouk A, Alshiteewi FB, Alhadi B, Alhaddad S, Gaffaz R, Elmabrouk O, Hamed TB, Alameen H, Zaid A, Elhadi A, Albakoush A (2020) Psychological status of healthcare workers during the civil war and COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 137:110221. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110221.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed during this study are included in this article.