Abstract

Deep learning has been widely used to analyze digitized hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained histopathology whole slide images. Automated cancer segmentation using deep learning can be used to diagnose malignancy and to find novel morphological patterns to predict molecular subtypes. To train pixel-wise cancer segmentation models, manual annotation from pathologists is generally a bottleneck due to its time-consuming nature. In this paper, we propose Deep Interactive Learning with a pretrained segmentation model from a different cancer type to reduce manual annotation time. Instead of annotating all pixels from cancer and non-cancer regions on giga-pixel whole slide images, an iterative process of annotating mislabeled regions from a segmentation model and training/finetuning the model with the additional annotation can reduce the time. Especially, employing a pretrained segmentation model can further reduce the time than starting annotation from scratch. We trained an accurate ovarian cancer segmentation model with a pretrained breast segmentation model by 3.5 hours of manual annotation which achieved intersection-over-union of 0.74, recall of 0.86, and precision of 0.84. With automatically extracted high-grade serous ovarian cancer patches, we attempted to train an additional classification deep learning model to predict BRCA mutation. The segmentation model and code have been released at https://github.com/MSKCC-Computational-Pathology/DMMN-ovary.

Keywords: Computational pathology, Deep learning, Ovarian cancer, Segmentation, Annotation

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A deep learning-based ovarian cancer segmentation model in pathology is developed

-

•

Only 3.5 hours of manual annotation were needed to train the segmentation model

-

•

BRCA mutation prediction is attempted based on H\&E-stained cancer morphology

1. Introduction

Deep learning, a subfield of machine learning, has shown an outstanding advancement in image analysis1,2 by training models using large public datasets.3, 4, 5, 6 Deep learning models have been used to analyze and understand digitized histopathology whole slide images to support some tedious and error-prone tasks.7, 8, 9, 10 For example, a deep learning model was used to identify breast cancers to search micrometastases and reduce review time.11 Similarly, another deep learning model was used as a screening tool for breast lumpectomy shaved margin assessment to save time for pathologists by excluding the majority of benign tissue samples.12 In addition, deep learning models have been investigated to discover novel morphological patterns indicating molecular subtypes from histologic images.13 Correlating digitized pathologic images with molecular information has contributed to prognosis prediction and personalized medicine.14 Specifically, molecular features from lung cancer,15 colorectal cancer,16,17 and breast cancer18, 19, 20 can be predicted by deep learning models from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained images.

All computational methods listed above either to diagnose cancers or to find biomarkers from cancer morphologies require accurate cancer segmentation of whole slide images. Unlike common cancers where public datasets with annotation are provided,21, 22, 23 training deep learning-based segmentation models for rare cancers would require a vast amount of manual annotation which is generally time-consuming. To overcome this challenge, we recently proposed Deep Interactive Learning (DIaL) to efficiently annotate osteosarcoma whole slide images to train a pixel-wise segmentation model.24 During an initial annotation step, annotators partially annotate tissue regions from whole slide images. By iteratively training/finetuning a segmentation model and adding challenging patterns from mislabeled regions to the training set to improve the model, an osteosarcoma model was able to be trained by 7 hours of manual annotation.

In this paper, we develop an ovarian cancer segmentation model by 3.5 hours of manual annotation using DIaL. We hypothesize that we can utilize a pretrained triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) segmentation model25 to train a high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) segmentation model because both TNBC and HGSOC show common high-grade carcinoma morphologies such as large pleomorphic nuclei and clumped chromatin. Transfer learning has been used when a data set is limited to train a model. The main challenge of training an ovarian cancer segmentation model is not the limited data set but the limited time for pathologists to annotate the data set. To reduce the annotation time from pathologists, our approach different from transfer learning finds essential regions to be annotated on a set of ovarian images. The main contribution of this work to train a HGSOC segmentation model is to start DIaL from a pretrained TNBC segmentation model25 to reduce manual annotation time by avoiding the initial annotation step. Ovarian cancer accounts for approximately 2% of cancer cases in the United States but is the fifth leading cancer causing death among women and the leading cause of death by cancer of the female reproductive system.26 HGSOC is the most common histologic subtype and accounts for 70-80% of deaths from all ovarian cancer.27 Identifying BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation status from HGSOC is important because family members of patients with germline mutations are at increased risk for breast and ovarian cancer and can benefit from early prevention strategies. In addition, it offers increased treatment options for making therapeutic decisions. Deleterious variants in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes are strong predictors of response to poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors such as olaparib, niraparib, and rucaparib.28,29 Hence, the analysis of BRCA1/2 mutational status is crucial for individualized strategies for the management of patients with HGSOC. Identification of BRCA1/2 mutation is currently done by genetic tests but some patients may not be able to get the genetic tests due to its high cost and limited resources. Although these limitations have been overcome by many factors including reduced BRCA testing costs and next-generation sequencing, only 20% of eligible women have accessed genetic testing in the United States.30 A cheaper approach to test BRCA1/2 mutation from H&E-stained slides is desired to examine wider range of ovarian cancer patients and to provide proper treatments to them. There has been an attempt to manually find morphological patterns of BRCA1/2 mutation.31 In this study, we conduct deep learning-based experiments to screen BRCA1/2 mutation from cancer regions on H&E-stained ovarian whole slide images automatically segmented by our model to potentially provide opportunities for more patients to examine their BRCA mutational statuses.

2. Material and methods

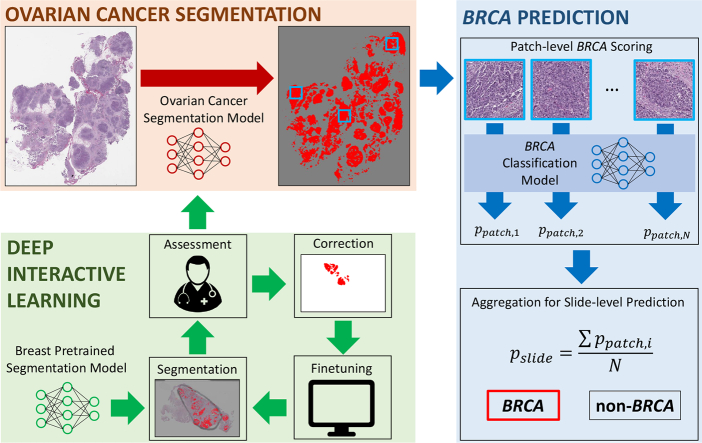

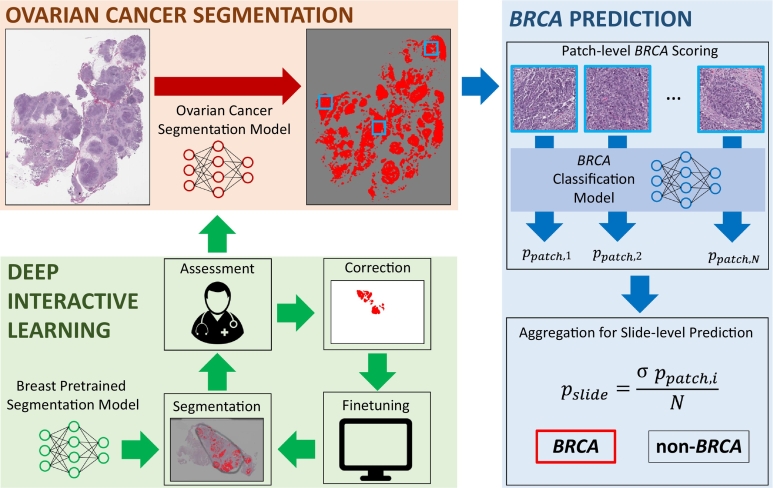

Fig. 1 shows the block diagram of our proposed method. Our method is composed of two steps: (1) ovarian cancer segmentation and (2) BRCA prediction. The goal of this study is to predict BRCA mutation from high-grade serous ovarian cancer, with a hypothesis that morphological patterns of the mutation would be shown on cancer regions. Therefore, we trained a deep learning model for automated segmentation of ovarian cancer from H&E-stained whole slide images to explore BRCA-related patterns on segmented cancer regions. Manual annotation process to train a deep learning-based segmentation model can be extremely time-consuming and tedious. To reduce annotation time, we used Deep Interactive Learning we previously proposed.24 Our previous work had an initial annotation step to start manual annotation from scratch. One contribution of this work is that we used a breast pretrained segmentation model25 as our initial model to start Deep Interactive Learning to further reduce annotation time by avoiding initial annotation. As a result, we were able to train our ovarian segmentation model with 3.5 hours of manual annotation. After the segmentation model was trained, we attempted to predict BRCA mutation based on cancer morphologies. We trained another model using ResNet-182 to generate patch-level scores indicating the probabilities of BRCA mutation. The patch-level scores were aggregated by averaging all patch-level scores to generate a slide-level score to classify an input slide image to either BRCA or non-BRCA. In this work, PyTorch32 was used for our implementation and an Nvidia Tesla V100 GPU was used for our experiments.

Fig. 1.

Block diagram of our proposed method to predict BRCA mutation from H&E-stained ovarian whole slide images. The first step was to segment ovarian cancer regions from whole slide images. To efficiently train the ovarian segmentation model, we used Deep Interactive Learning.24 Since we started the process from a breast pretrained segmentation model, an annotator only spent 3.5 hours to annotate/correct whole slide images. After segmentation was done, cancer patches were processed by a BRCA classification model to generate patch-level scores indicating the probability of BRCA mutation. All patch-level scores were aggregated by averaging them to generate a slide-level prediction for BRCA mutation.

2.1. Data set

To segment ovarian cancer and to predict BRCA mutation based on tumor morphology, we collected 609 high-grade serous ovarian cancer cases at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The MSK-IMPACT whole slide images were digitized in 20× magnification by Aperio AT2 scanners. Approximately 20% of the cohort (119 images) have either BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and the other 80% of the cohort (490 images) have no BRCA mutation. We randomly split 60% of cases as a training set, 20% as a validation set, and the remaining 20% as a testing set, where the number of BRCA and non-BRCA images for training, validation, and testing are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The number of BRCA and non-BRCA whole slide images for our training, validation, and testing sets.

| BRCA | Non-BRCA | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Images | 73 | 294 | 367 |

| Validation Images | 23 | 98 | 121 |

| Testing Images | 23 | 98 | 121 |

| Total | 119 | 490 | 609 |

2.2. Ovarian cancer segmentation

We hypothesize that morphological patterns caused by BRCA mutation would most likely be present in cancer regions on ovarian whole slide images. To train our BRCA prediction model at scale, we trained an ovarian cancer segmentation model to automatically extract cancer regions and avoid any time-consuming manual segmentation. In this work, we used Deep Multi-Magnification Network (DMMN) with multi-encoder, multi-decoder, and multi-concatenation25 for ovarian cancer segmentation. DMMN generates a segmentation patch in size of 256 × 256 pixels in 20× based on various morphological features from a set of patches in size of 256 × 256 pixels from multiple magnifications in 20×, 10×, and 5×.

To train our DMMN model, manual annotation acquired from pathologists generally becomes a bottleneck. Hence, we adopted Deep Interactive Learning (DIaL)24 to reduce time for manual annotation. As shown in Fig. 1, DIaL is composed of multiple iterations of segmentation, assessment, correction, and finetuning. In each iteration, the annotators assess segmentation predictions generated by the previous model and correct any mislabeled regions. The annotated patches are then included in a training set to train/finetune the segmentation model. These iterations during DIaL help the annotators to efficiently annotate challenging morphological patterns so the training set can contain heterogeneous patterns of classes. In our previous DIaL work, we started our initial annotation from scratch which took the majority of our annotation time. To further reduce annotation time, we utilized a pretrained segmentation model from another cancer type to skip the initial annotation step. In this work, we used a pretrained model to segment high-grade invasive ductal carcinoma from triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) images25 to train our model to segment high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC) because HGSOC and TNBC have shared morphological features such as large pleomorphic nuclei.

The pretrained model can segment 6 classes which are carcinoma, benign epithelium, stroma, necrosis, adipose tissue, and background. During DIaL iterations, we kept the model to segment 6 classes but we converted benign epithelium, stroma, necrosis, adipose tissue, and background to be non-cancer to have binary segmentation. The training set contained patches from both TNBC images and ovarian images. To optimize the model, we used stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with a weighted cross entropy loss function, where a weight for class c, wc, was determined by where Nc was the number of annotated pixels for class c and Nt is the total number of annotated pixels. Random rotation, vertical and horizontal flips, and color jittering were used as data augmentation transformations.33 During the first training, we trained the model from randomly initialized parameters with a learning rate of 5 × 10−5, a momentum of 0.99, and a weight decay of 10−4, where the same hyperparameters were used from our previous breast segmentation training.25 After the first iteration, we finetuned the model from the previous parameters with a learning rate of 5 × 10−6. During training/finetuning iterations, we selected a model with the maximum intersection-over-union on a validation set as the final model of the iteration. The final segmentation model processes patches on tissue regions extracted by Otsu Algorithm.34

2.3. BRCA prediction

With our hypothesis that BRCA morphological patterns would be shown on cancer regions, we trained a patch-level classification model predicting BRCA status from cancer patches. Cancer patches were extracted from cancer masks from the ovarian cancer segmentation model. A patch from a whole slide image was extracted if more than 50% of pixels in the patch were segmented as cancer. It was observed that the number of cancer patches from training images was imbalanced. If all cancer patches were used during training, morphological patterns on images with large cancer size would be more emphasized. Therefore, we set an upper limit, Nm, as the maximum number of patches from a training whole slide image. Specifically, if a whole slide image contained more than Nm patches, Nm training patches were randomly subsampled from the whole slide image. Otherwise, all patches from the whole slide image were included in the training set. In this work, we set NBRCAm = 5000 and NnonBRCAm = 1000 where NBRCAm was selected as the median value of the number of patches for BRCA cases, and NnonBRCAm was selected to balance the number of training patches between BRCA and non-BRCA classes. Note that we did not subsample patches from the validation and testing sets to produce slide-level predictions based on all cancer regions on whole slide images. The numbers of training, validation, and testing patches for BRCA and non-BRCA classes are shown in Table 2. We trained three models in three different magnifications, 20×, 10×, and 5×. We used ResNet-182 with patch size of 224 × 224 pixels. We used the same weighted cross entropy as a loss function, Adam35 with learning rate of 10−5 as an optimizer, and used random horizontal and vertical flips, 90-degree rotations, and color jittering as data augmentation transformations.33

Table 2.

The number of cancer patches for the training set, the validation set, and the testing set. Training patches between BRCA and non-BRCA are subsampled for balancing.

| BRCA | Non-BRCA | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Patches | 247,059 | 252,166 | 499,225 |

| Validation Patches | 120,753 | 592,232 | 712,985 |

| Testing Patches | 142,983 | 624,231 | 767,214 |

Although our prediction model generates patch-level scores, ppatch, the final goal of this work is to classify BRCA mutation in slide-level. Hence, we validated and tested our models in slide-level by aggregating patch-level scores. In this work, a slide-level score, pslide, was calculated by averaging the N patch scores in an input whole slide image:

| (1) |

We used area-under-curves (AUCs) as our evaluation metric.

2.4. Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (Protocol #21-473).

3. Results

3.1. Training an ovarian cancer segmentation model with Deep Interactive Learning

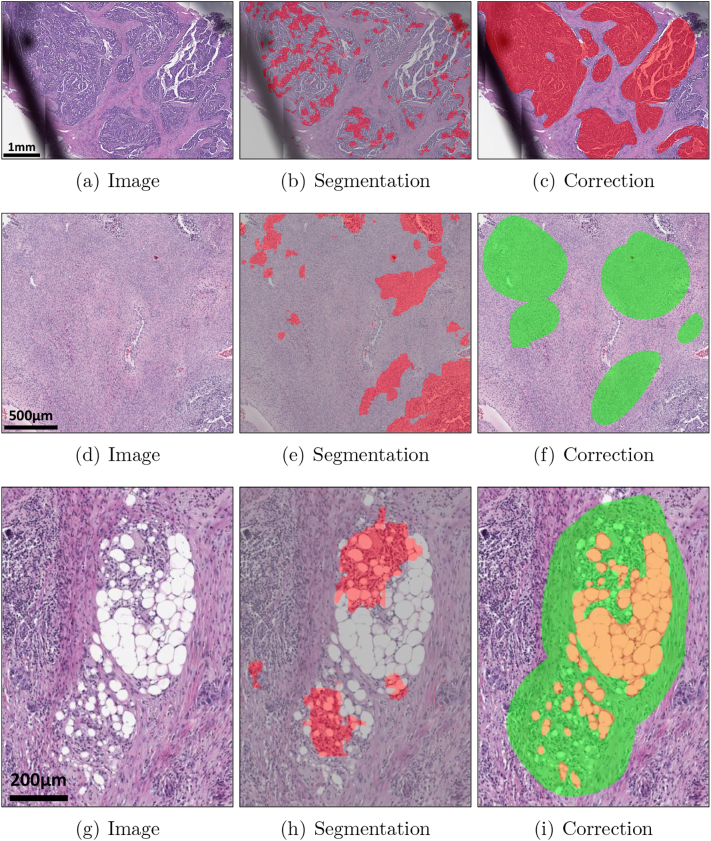

We iteratively trained our ovarian cancer segmentation model using Deep Interactive Learning (DIaL) where annotation was done by an in-house slide viewer.36 We randomly selected 60 whole slide images from our training set where 20 images with BRCA1 status, 20 images with BRCA2 status, and 20 images with no BRCA status were selected to make sure our ovarian cancer segmentation model can successfully segment all molecular subtypes. After segmenting all 60 images using the pretrained breast model, denoted as 0, we observed papillary pattern for carcinoma and ovarian stroma were mislabeled because these patterns were not presented on triple-negative breast cancer images. The annotator corrected mislabeled regions on 14 whole slide images to train the first model denoted as 1, which took approximately 1 hour. Note that papillary pattern is combined within carcinoma class and ovarian stroma is combined within stroma class without introducing new class. During the second iteration, we observed that carcinoma and stroma were segmented correctly but some challenging patterns such as fat necrosis and fat cells in lymph node were mislabeled by 1. The annotator looked for those challenging patterns in detail and annotated 11 whole slide images (3 images overlapping with the first correction step) to train the second model denoted as 2, took approximately 2 hours. During the third iteration, we observed that some markers were mislabeled as carcinoma by 2, so the annotator corrected the other 3 whole slide images in 30 minutes to train the third model denoted as 3. After finetuning the model, we observed 3 can successfully segment cancers on the training set so we completed the training stage. In total, we annotated 25 ovarian whole slide images and spent 3.5 hours. As a comparison, exhaustively annotating cancer regions on one ovarian whole slide image without DIaL took 1.5 hours, indicating one would be able to annotate only 2–3 training whole slide images within the same 3.5 hours. Fig. 2 shows mislabeled regions by a segmentation model and corrected regions using DIaL.

Fig. 2.

Deep Interactive Learning for efficient annotation to train an ovarian cancer segmentation model. Instead of annotating all regions on ovarian whole slide images, the annotator can only annotate a subset of regions to train/finetune the ovarian cancer segmentation model. (a–c) The first iteration of correction of mislabeled cancer regions from 0. (d–f) The first iteration of correction of mislabeled stroma regions from 0. (g–i) The second iteration of correction of mislabeled fat necrosis regions from 1. Cancers are highlighted in red, stroma in green, and adipose tissue in orange.

3.2. Ovarian cancer segmentation evaluation

To quantitatively analyze ovarian cancer segmentation models, another pathologist who was not involved in training manually generated groundtruth for 14 whole slide images randomly selected from the testing set. Intersection-over-union (IOU), recall, and precision are used to evaluate segmentation models, where they are defined as:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

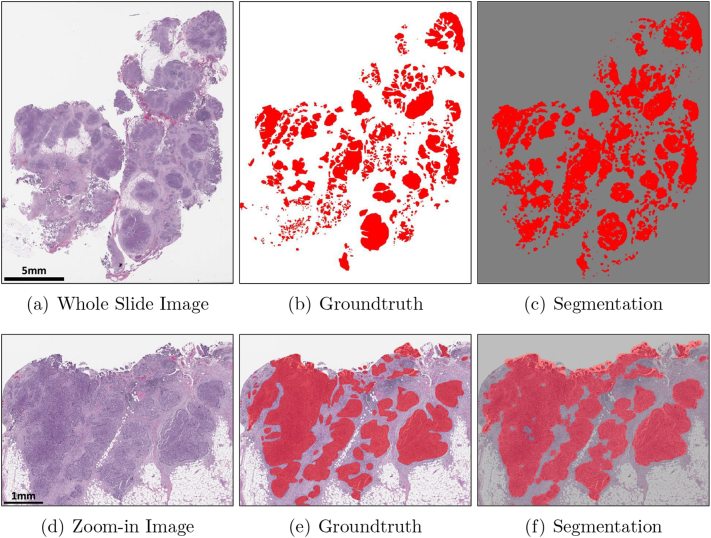

where NTP, NFN, and NFP are the number of true-positive pixels, the number of false-negative pixels, and the number of false-positive pixels, respectively. Table 3 shows IOU, recall, and precision values for 0, 1, 2, and 3 where the final model achieved IOU of 0.74, recall of 0.86, and precision of 0.84. A high precision value and a low recall value from 0 indicate that the initial model trained by triple-negative breast cancer was not able to segment all high-grade serous ovarian cancer. After the first iteration by adding papillary patterns for carcinoma, both the IOU value and the recall value were significantly improved. The second and third iterations had minor updates for correction so the IOU value, the recall value, and the precision value were not significantly improved. We were able to achieve the highest recall value from the final model indicating the majority of high-grade serous ovarian cancer regions were successfully segmented and heterogeneous morphological patterns would be used to train the BRCA classification model. Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S1 and S2 show that our final model can successfully segment ovarian cancers present on three testing whole slide images. We observed the final model generates false negatives and false positives, shown in Supplementary Fig. S3 and S4. Specifically, false negatives we observed were caused by cautery artifact or poor staining. False positives were caused by smooth muscles on fallopian tube, colon epithelium, or blood vessels which were underrepresented in the training data. By including normal tissue samples from metastasized cases from other organ types in the training set to further finetune our segmentation model, we expect to reduce false positives. The segmentation model and code have been released at https://github.com/MSKCC-Computational-Pathology/DMMN-ovary.

Table 3.

Intersection-over-union (IOU), recall, and precision for the initial model (0), the first model (1), the second model (2), and the final model (3). Note that the initial model is the pretrained breast model.25 The highest IOU, recall, and precision values are highlighted in bold.

| IOU | Recall | Precision | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.93 |

| 1 | 0.74 | 0.84 | 0.86 |

| 2 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.87 |

| 3 | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.84 |

Fig. 3.

Ovarian image, its groundtruth, and its segmentation. (a–c) show the entire whole slide image and (d–f) show a zoom-in image. Cancers are highlighted in red. White regions in (b,e) and gray regions in (c,f) are non-cancer.

3.3. BRCA prediction

Based on cancer segmentation, we trained three BRCA classification models in 20×, 10×, and 5×, denoted as 20×, 10×, and 5×, respectively. During training, the model with the highest area-under-curves (AUCs) on the validation set was selected as the final model. Table 4 shows AUCs on the validation set and the testing set using the three models in various magnifications where the AUCs were ranging between 0.49 and 0.67 on the validation set and between 0.40 and 0.43 on the testing set.

Table 4.

Area-under-curves (AUCs) of three classification models on the validation set and the testing set.

| 20× | 10× | 5× | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validation AUC | 0.49 | 0.65 | 0.67 |

| Testing AUC | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.43 |

4. Discussion

In this paper, we described Deep Interactive Learning (DIaL) which helps annotators to reduce their annotation time to train deep learning-based pixel-wise segmentation models. Our ovarian cancer segmentation model was able to accurately segment cancer regions presented in H&E-stained whole slide images with intersection-over-union of 0.74, recall of 0.86, and precision of 0.84.

Cancer segmentation of histologic whole slide images is used to accurately diagnose malignant tissue. For example, a patch-wise model is designed to identify invasive carcinoma in breast whole slide images.37 Multiple techniques for automated breast cancer metastasis detection in lymph nodes38,39 has been developed through challenges such as CAMELYON1621 and CAMELYON17.22 For more accurate segmentation, pixel-wise semantic segmentation models such as Fully Convolutional Network (FCN),40 SegNet,41 and U-Net42 have been utilized on whole slide images.43, 44, 45 One limitation of these semantic segmentation models is that their input is a patch from a single magnification, where pathologists generally review tissue samples via a microscope in multiple magnifications for cancer diagnosis. To overcome this challenge in pathology, Deep Multi-Magnification Network (DMMN) utilizing a set of patches from multiple magnifications has been proposed.25 In DMMN, patches from 20×, 10×, and 5× magnifications in a multi-encoder, multi-decoder, multi-concatenation architecture are fully utilized to fuse morphological features from both low magnification and high magnification. The proposed segmentation network outperformed other single-magnification-based networks.

Cancer segmentation is a critical process not only for diagnosis but also for downstream tasks such as molecular subtyping from H&E-stained whole slide images. Molecular status is currently detected by genetic tests but the genetic tests are generally costly and may not be available for all patients. Deep learning models as screening tools can help patients to get proper treatment from cheap H&E stains.46 Six mutations were predicted from patches classified as lung adenocarcinoma.15 Microsatellite instability (MSI) status was predicted from patches classified as gastrointestinal cancer.16 More molecular pathways and mutations in colorectal cancer were predicted on tumor regions.17 Furthermore, molecular alterations from 14 tumor types were predicted from tumor patches.47 BRCA mutation18 and HER2 status20 in breast cancer were predicted from tumor patches on H&E-stained images. To train deep learning models to determine molecular subtypes from H&E-stained images, manual annotation of tumor regions on whole slide images was required.18,20,47 To avoid manual annotation of tumor regions for downstream predictions, automated segmentation would be desired.

Alternatively, weakly-supervised learning has been proposed to avoid manual annotation of cancer regions to train cancer segmentation models. Weakly-supervised learning provides approaches to train classification models by weak labels, such as case-level labels instead of pixel-level labels.48,49 Weakly-supervised learning can be a promising solution for common cancers because it require a large training set representing one whole slide image as one data point. For example, a weakly-supervised method to predict estrogen receptor status in breast cancer was trained by 2,728 cases.50 However, for relatively rare cancers such as high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) where the number of cases is limited, weakly-supervised learning can be challenging to detect morphological patterns representing molecular mutations on whole slide images. In our study, the total number of cases of HGSOC was 609 where only 20% has BRCA status (119 cases). Therefore, instead of weakly-supervised learning, supervised mutation predictions from cancer segmentation would be more proper especially for rare cancers with limited number of cases.

For automated cancer segmentation, reducing manual annotation time on digitized histopathology images to train segmentation models has been a practical challenge. Deep learning-based approaches require large quantities of training data with annotations, but pixel-wise annotation for a segmentation model is extremely time-consuming and especially difficult for pathologists with their busy clinical duty. To reduce annotation burden, approaches to train cell segmentation models with a few scribbles were suggested.51,52 Human-Augmenting Labeling System (HALS) introduced an active learner selecting a subset of training patches to reduce annotation burden for cell annotation.53 To segment tissue subtypes, an iterative tool, known as Quick Annotator, was developed to speed up the annotation time within patches extracted from whole slide images.54 Patch-level annotation may limit tissue subtypes’ field-of-view, potentially causing poor segmentation.25,55 Deep Interactive Learning (DIaL)24 was proposed to efficiently label multiple tissue subtypes in whole slide image-level to reduce time for manual annotation but to have accurate segmentation. After an initial segmentation training based on initial annotations, mislabeled regions are corrected by annotators and included in the training set to finetune the segmentation model. As challenging or rare patterns are added during correction, the model can improve its segmentation performance iteratively. Within 7 hours of manual annotation, the osteosarcoma segmentation model achieved an error rate between its multi-class segmentation predictions and pathologists’ manual assessment within an inter-observer variation rate.24 In this paper, we further reduced the annotation time by starting from a pretrained segmentation model from a different cancer type to skip the initial annotation step. In our case, we used a triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) segmentation model25 as our initial model and the annotator spent only 3.5 hours to train an accurate HGSOC segmentation model. We considered to use a TNBC segmentation model to train HGSOC segmentation model because both TNBC and HGSOC share high-grade carcinoma morphologic features. It is remained as a future step to generalize our approach by quantitatively comparing cellular representations between a training set for a pretrained model and a testing set.

We desired to predict BRCA mutation status from cancer regions from H&E-stained ovarian whole slide images. BRCA mutation status can determine patients’ future treatment but it is currently detected by expensive genetic examinations. A deep learning-based tool to screen potential BRCA cases for genetic examinations from cheap and common H&E staining would expect to enhance patients’ treatment and outcome. Based on our experiments, we were not able to discover morphological patterns on ovarian cancer indicating BRCA mutation. Several future steps are proposed: (1) We had a hypothesis that the BRCA-related morphological patterns may be shown on cancer regions. In the future, we may want to expand our hypothesis to non-cancer regions.56 For example, one could train a model from tumor-stroma regions. (2) We had a hypothesis that the BRCA-related morphological patterns may be shown globally. Therefore, we included all cancer patches to the training set with case-level labels. If the BRCA patterns are shown locally (i.e., some cancer regions may not contain the BRCA pattern although its case is labeled as BRCA), then weakly-supervised learning approaches48,49 may be a better option by increasing the number of cases. (3) Lastly, cancer morphologies with BRCA mutation could be heterogeneous because their mutational spectrum is highly heterogeneous.57 A self-supervised clustering technique could be used to discover multiple morphological patterns of BRCA mutation by increasing the number of BRCA-mutated cases.

In conclusion, we developed an accurate deep learning-based pixel-wise cancer segmentation model for ovarian cancer. Especially, by Deep Interactive Learning with a pretrained model from breast cancer, we were able to reduce manual annotation time for training. Although our study had suboptimal performance on predicting BRCA mutation based on morphological patterns, we are confident that our ovarian segmentation model can be used to discover other mutation-related patterns from H&E-stained images for screening tools to determine treatment and to enhance patient care.

Data availability

The segmentation model and code are publicly available at https://github.com/MSKCC-Computational-Pathology/DMMN-ovary. The data set used and/or analyzed during the current study is available on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Warren Alpert Foundation Center for Digital and Computational Pathology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 to T.J.F. and the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government (NRF-2021R1C1C2007816) to J.R.

Author contributions

D.J.H., C.-S.P., T.J.F., J.R. conceived the study; D.J.H. developed the machine learning model and provided statistical analysis in consultation with M.H.C., J.J., M.E.R., and J.R.; M.H.C. and C.M.V. reviewed and annotated whole slide images; D.J.H. and J.R. wrote the initial manuscript; All authors read, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

T.J.F. is co-founder, chief scientist and equity holder of Paige.AI.

C.M.V. is a consultant for Paige.AI.

D.J.H., M.H.C., J.J., M.E.R., C.-S.P., and J.R. declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpi.2022.100160.

Contributor Information

Jin Roh, Email: jin.roh@aumc.ac.kr.

Thomas J. Fuchs, Email: Thomas.Fuchs.AI@mssm.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.LeCun Y., Bengio Y., Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. 2015;521:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature14539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He K., Zhang X., Ren S., Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2016:770–778. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russakovsky O., Deng J., Su H., et al. ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. International Journal of Computer Vision. 2015;115:211–252. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krizhevsky A. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images. Tech Report. 2009:1–58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Everingham M., Van Gool L., Williams C.K.I., Winn J., Zisserman A. The PASCAL Visual Object Classes (VOC) Challenge. International Journal of Computer Vision. 2010;88:303–338. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin T.-Y., Maire M., Belongie S., et al. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. 2014:740–755. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs T.J., Buhmann J.M. Computational pathology: Challenges and promises for tissue analysis. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics. 2011;35(7):515–530. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Litjens G., Kooi T., Ehteshami Bejnordi B., et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Medical Image Analysis. 2017;42:60–88. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srinidhi C.L., Ciga O., Martel A.L. Deep neural network models for computational histopathology: A survey. Medical Image Analysis. 2021;67 doi: 10.1016/j.media.2020.101813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Laak J., Litjens G., Ciompi F. Deep learning in histopathology: the path to the clinic. Nature Medicine. 2021;27:775–784. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner D.F., MacDonald R., Liu Y., et al. Impact of deep learning assistance on the histopathologic review of lymph nodes for metastatic breast cancer. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2018;42(12):1636–1646. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Alfonso T.M., Ho D.J., Hanna M.G., et al. Multi-magnification-based machine learning as an ancillary tool for the pathologic assessment of shaved margins for breast carcinoma lumpectomy specimens. Modern Pathology. 2021;34:1487–1494. doi: 10.1038/s41379-021-00807-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bera K., Schalper K.A., Rimm D.L., Velcheti V., Madabhushi A. Artificial intelligence in digital pathology — new tools for diagnosis and precision oncology, Nature Reviews. Clinical Oncology. 2019;16:703–715. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komura D., Ishikawa S. Machine learning methods for histopathological image analysis, Computational and Structural. Biotechnology Journal. 2018;16:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coudray N., Ocampo P.S., Sakellaropoulos T., et al. Classification and mutation prediction from non–small cell lung cancer histopathology images using deep learning. Nature Medicine. 2018;24:1559–1567. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0177-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kather J.N., Pearson A.T., Halama N., et al. Deep learning can predict microsatellite instability directly from histology in gastrointestinal cancer. Nature Medicine. 2019;25:1054–1056. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0462-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bilal M., Raza S.E.A., Azam A., et al. Development and validation of a weakly supervised deep learning framework to predict the status of molecular pathways and key mutations in colorectal cancer from routine histology images: a retrospective study. The Lancet Digital Health. December 2021;3(12):e763–e772. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00180-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X., Zou C., Zhang Y., et al. Prediction of BRCA gene mutation in breast cancer based on deep learning and histopathology images. Frontiers in Genetics. 2021;12:1147. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.661109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ektefaie Y., Yuan W., Dillon D.A., et al. Integrative multiomics-histopathology analysis for breast cancer classification, npj. Breast Cancer. 2021;7:147. doi: 10.1038/s41523-021-00357-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farahmand S., Fernandez A.I., Ahmed F.S., et al. Deep learning trained on hematoxylin and eosin tumor region of Interest predicts HER2 status and trastuzumab treatment response in HER2+ breast cancer. Modern Pathology. 2022;35:44–51. doi: 10.1038/s41379-021-00911-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehteshami Bejnordi B., Veta M., Johannes van Diest P., et al. Diagnostic assessment of deep learning algorithms for detection of lymph node metastases in women with breast cancer. JAMA. 2018;318(22):2199–2210. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.14585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandi P., Geessink O., Manson Q., et al. From detection of individual metastases to classification of lymph node status at the patient level: the camelyon17 challenge. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2019;28(2):550–560. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2018.2867350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amgad M., Elfandy H., Hussein H., et al. Structured crowdsourcing enables convolutional segmentation of histology images. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(18):3461–3467. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho D.J., Agaram N.P., Schüffler P.J., et al. Deep interactive learning: An efficient labeling approach for deep learning-based osteosarcoma treatment response assessment. Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. 2020:540–549. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho D.J., Yarlagadda D.V.K., D’Alfonso T.M., et al. Deep multi-magnification networks for multi-class breast cancer image segmentation. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics. 2021;88 doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2021.101866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Fuchs H.E., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2022;72(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lisio M.A., Fu L., Goyeneche A., Gao Z.H., Telleria C. High-grade serous ovarian cancer: Basic sciences, clinical and therapeutic standpoints. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019;20:952. doi: 10.3390/ijms20040952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.G. Kim, G. Ison, A. E. McKee, H. Zhang, S. Tang, T. Gwise, R. Sridhara, E. Lee, A. Tzou, R. Philip, H. Chiu, T. Ricks, T. Palmby, A. Russell, G. Ladouceur, E. Pfuma, H. Li, L. Zhao, Q. Liu, R. Venugopal, A. Ibrahim, P. R, Fda approval summary: Olaparib monotherapy in patients with deleterious germline brca-mutated advanced ovarian cancer treated with three or more lines of chemotherapy, Clinical Cancer Research 21 (19) (2015) 4257–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Ray-Coquard I., Pautier P., Pignata S., et al. Investigators, Olaparib plus bevacizumab as first-line maintenance in ovarian cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381(25):2416–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Childers C.P., Childers K.K., Maggard-Gibbons M., Macinko J. National estimates of genetic testing in women with a history of breast or ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(34):3800–3806. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.6314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soslow R.A., Han G., Park K.J., et al. Morphologic patterns associated with brca1 and brca2 genotype in ovarian carcinoma. Modern Pathology. 2012;25:625–636. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paszke A., Gross S., Massa F., et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2019;32:8024–8035. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buslaev A., Iglovikov V.I., Khvedchenya E., Parinov A., Druzhinin M., Kalinin A.A. Albumentations: Fast and flexible image augmentations. Information. 2020;11(2) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otsu N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics. 1979;9(1):62–66. [Google Scholar]

- 35.D. P. Kingma, J. Ba, Adam: A method for stochastic optimization, arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 (December 2014).

- 36.Schüffler P.J., Geneslaw L., Yarlagadda D.V.K., et al. Integrated digital pathology at scale: A solution for clinical diagnostics and cancer research at a large academic medical center. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2021;28(9):1874–1884. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocab085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cruz-Roa A., Gilmore H., Basavanhally A., et al. Accurate and reproducible invasive breast cancer detection in whole-slide images: A deep learning approach for quantifying tumor extent. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(46450):1–14. doi: 10.1038/srep46450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D. Wang, A. Khosla, R. Gargeya, H. Irshad, A. H. Beck, Deep learning for identifying metastatic breast cancer, arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.05718 (June 2016).

- 39.Lee B., Paeng K. A robust and effective approach towards accurate metastasis detection and pN-stage classification in breast cancer. Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. 2018:841–850. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Long J., Shelhamer E., Darrell T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2015:3431–3440. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2572683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Badrinarayanan V., Kendall A., Cipolla R. SegNet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 2017;39(12):2481–2495. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2644615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ronneberger O., Fischer P., Brox T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. 2015:231–241. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gecer B., Aksoy S., Mercan E., Shapiro L.G., Weaver D.L., Elmore J.G. Detection and classification of cancer in whole slide breast histopathology images using deep convolutional networks. Pattern Recognition. 2018;84:345–356. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2018.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hermsen M., de Bel T., den Boer M., et al. Deep learning–based histopathologic assessment of kidney tissue. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2019;30(10):1968–1979. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019020144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seth N., Akbar S., Nofech-Mozes S., Salama S., Martel A.L. Automated segmentation of DCIS in whole slide images, Proceedings of the European Congress on Digital. Pathology. 2019:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baxi V., Edwaqrds R., Michael M., Saha S. Digital pathology and artificial intelligence in translational medicine and clinical practice. Modern Pathology. 2022;35:23–32. doi: 10.1038/s41379-021-00919-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kather J.N., Heij L.R., Grabsch H.I., et al. Pan-cancer image-based detection of clinically actionable genetic alterations, Nature. Cancer. 2020;1:789–799. doi: 10.1038/s43018-020-0087-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.G. Campanella, M. G. Hanna, L. Geneslaw, A. Miraflor, V. Werneck Krauss Silva, K. J. Busam, E. Brogi, V. E. Reuter, D. S. Klimstra, T. J. Fuchs, Clinical-grade computational pathology using weakly supervised deep learning on whole slide images, Nature Medicine 25 (2019) 1301–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Lu M.Y., Williamson D.F.K., Chen T.Y., Chen R.J., Barbieri M., Mahmood F. Data-efficient and weakly supervised computational pathology on whole-slide images, Nature. Biomedical Engineering. 2021;5:555–570. doi: 10.1038/s41551-020-00682-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naik N., Madani A., Esteva A., et al. Deep learning-enabled breast cancer hormonal receptor status determination from base-level H&E stains. Nature Communications. 2020;11:5727. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19334-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee H., Jeong W.-K. Scribble2label: Scribble-supervised cell segmentation via self-generating pseudo-labels with consistency. Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. 2020:14–23. [Google Scholar]

- 52.N. Martinez, G. Sapiro, A. Tannenbaum, T. J. Hollmann, S. Nadeem, Impartial: Partial annotations for cell instance segmentation, bioRxiv 2021.01.20.427458 (January 2021).

- 53.van der Wal D., Jhun I., Laklouk I., et al. Biological data annotation via a human-augmenting AI-based labeling system, npj Digital Medicine. 2021;4:145. doi: 10.1038/s41746-021-00520-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.R. Miao, R. Toth, Y. Zhou, A. Madabhushi, A. Janowczyk, Quick Annotator: an open-source digital pathology based rapid image annotation tool, The Journal of Pathology: Clinical Research (July 2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Bokhorst J.M., Pinckaers H., van Zwam P., Nagtegaal I., van der Laak J., Ciompi F. Learning from sparsely annotated data for semantic segmentation in histopathology images. Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Imaging with Deep Learning. 2019:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brockmoeller S., Echle A., Ghaffari Laleh N., et al. Deep learning identifies inflamed fat as a risk factor for lymph node metastasis in early colorectal cancer. Journal of Pathology. 2022;256(3):269–281. doi: 10.1002/path.5831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.J. Hirst, J. Crow, A. Godwin, Ovarian cancer genetics: Subtypes and risk factors, in: O. Devaja, A. Papadopoulos (Eds.), Ovarian Cancer, IntechOpen, Rijeka, 2018, Ch. 1.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.