Abstract

A crisis is an immediate threat to the functioning of society, while disaster is an actual manifestation of a crisis. Both are now even more critically socially constructed. In the middle of battle with the COVID-19 pandemic, the Republic of Croatia's capital of Zagreb was afflicted with another disaster – two severe earthquakes. Restrictive public health measures were already in place, including restriction on public transport, travel between regions, closure of educational and other public institutions, alongside measures of physical distancing. Most previous cases of COVID-19 were centered in Zagreb, leading to concern of spreading the disease into disease-free communities. It seems that earthquakes did not have an effect on disease transmission - the number of COVID-19 cases remained stable through the 14-day incubation period, with a linear pandemic curve in Croatia in April, and flattened in May. This leads to a conclusion that the earthquake did not have a direct effect on disease spread. Despite the fact that the current pandemic and its responses are unique, this paradox can have interesting repercussions on how we conceptualize and approach notions as vulnerability and resilience.

Keywords: Earthquake, Pandemic, COVID-19, resilience, Crisis

Discussion

A crisis is an immediate threat to the usual functioning of society, while disaster is an actual manifestation of a crisis with unfavorable outcomes. (Rodríguez et al., 2018) So, societies shape a wider context of crises and disasters beyond their initial definition. (Rodríguez et al., 2018, Arcaya et al., 2020)

Whether natural or technological, crises and disasters are still widespread, but humans’ abilities to absorb their effects are increasing. (Rodríguez et al., 2018, Morabia and Benjamin, 2018, Benjet et al., 2016) Indeed, the history of humanity is a history of overcoming such undesirable, threatening events. In that sense, terms such as resistance, resilience and vulnerability emerged stressing the complex interrelationships between traits and states, processes and outcomes of (mal)adaptation at many different levels of social functions and structures (ranging from individual to society as a whole). (Bonanno, 2004, Bonanno et al., 2010)

Global disasters occurring in contemporary, highly interconnected societal context have some uniqueness. Such disasters usually involve emergence of a novel threatening agent (that may have both “traditional”, and “non-traditional” features), they easily crosses functional and societal boundaries and settings (making it difficult to disentangle the initial threat from its’ immediate and distant consequences), and are more critically shaped by mass communication systems. (Rodríguez et al., 2018, Korman et al., 2019, Albrecht, 2018, Kaniasty, 2019) Crises and disasters are now even more critically socially constructed, and they often have more significant symbolic than material importance.

This becomes evident as we witness the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic swiftly overcoming all previously established preparations, mitigation scenarios and response strategies while resulting in tragic consequences. (Fauci et al., 2020, Bedford et al., 2020, Gostin et al., 2020, Emanuel et al., 2020, Auerbach and Miller, 2020) This provoked previously unimaginable, secondary response strategies - highly restrictive, containment and mitigation, public health measures. Although now considered as necessary, such responses are characterized by an unprecedented level of disruption of core social functions – itself fulfilling the definition of a disastrous event. (Gostin et al., 2020, Horesh and Brown, 2020, Brooks et al., 2020) As possible effects of such response strategies are far from clear, especially relative to the neutralization of the infectious threat, they are followed by omnipresent ambiguity and uncertainty.

In the middle of battle with COVID-19 pandemic the Republic of Croatia's capital city of Zagreb was afflicted with another disaster - earthquakes. Two most extensive earthquakes were 5.5 and 5.0 on Richter scale occurring on 6:24 and 7:04 AM, March 22nd, 2020. Ever since, the ground continued shaking (in a less physically devastating manner) for next three weeks. At that time, Zagreb was a COVID-19 pandemic “hot spot” in Croatia, counting 122 of total 254 of positive cases. Restrictive public health measures were introduced on March 22nd, including restriction on public transport, travel between regions, closure of educational and other public institutions, alongside generally applied measures of physical distancing and recommended (self)isolation. Curiously enough, Zagreb is the home city of dr. Andrija Stampar, one of the most renown epidemiologists and public health experts of the 20 th Century and the first president of the World Health Organization. (Brown and Fee, 2006)

So, one could expect that earthquakes occurring alongside ongoing pandemic, especially in the place where they are not commonly experienced (last significant one was about 140 years ago), could have additional/reinforcing negative direct and indirect effects on pandemic dynamics and its’ foreseeable consequences. (Reifels et al., 2013, Dar et al., 2014, Lowe et al., 2019, Malilay et al., 2014) Both disasters often strike unexpectedly without warning and bring adversity to a great deal of people, but a serious earthquake occurring during the current pandemic managed by a strategy of generally applied restrictive infection containment measures has raised additional concern. With the earthquake causing devastating damage to the entire city center including major hospitals, leaving over half a million inhabitants barred entry into their homes, the situation represented a peculiar combination of the need to reinforce measures of physical distancing and humanitarian relief alongside urgent measures aimed at damage control and assessment. Aditionally, natural and even adaptive responses to earthquakes could potentiate infection transmission, within the city (as people immediately left their homes after the earthquake) as well within the country (as people tried to evacuate to other areas). In that sense, the Civil Service Headquarters immediately called for upholding restrictive containment measures, in fear of the citizens’ prolonged contact and grouping outside their homes, but that was impossible to forestall and effectively monitor. However, a substantial number of citizens left the city in fear of a follow-up earthquakes and attempted to reach their relatives and residences in other parts of the country. Most of them were successfully halted at various checkpoints surrounding the city, but many managed to relocate, bringing entire families with them. As most previous cases of COVID-19 were centered in Zagreb, this led to concerns of spreading the disease into disease-free communities, breaking down previously quite successful epidemiologic chains of disease contact monitoring and possible concerns on straining local health care resources in case of disease escalation. Effective epidemiological surveillance was continued, proposing strict self-isolation criteria and quarantine measures for COVID-19 positive patients and their contacts, but the number of screening tests has not been increased. Many citizens whose homes were destroyed needed to be displaced and settled in other places (20 000 citizens needed to find alternative residences while 450 citizens who were unable to do so, were settled in one public institution). Also, as a part of earthquake recovery processes, many “non-essential” workers, such as construction workers, need to be “activated”. Additionally, indirect effects included serious damage to cities’ major hospitals, which put additional pressure on the health care system and urged a need for reorganization of already adopted pandemic mitigation and response procedures and strategies, as these institutions could not fulfill their initially planned purposes (f.e. some inpatients needed to be moved from damaged institutions to others, that were previously intended to care for COVID-19 infected patients) (Fig. 1 ).

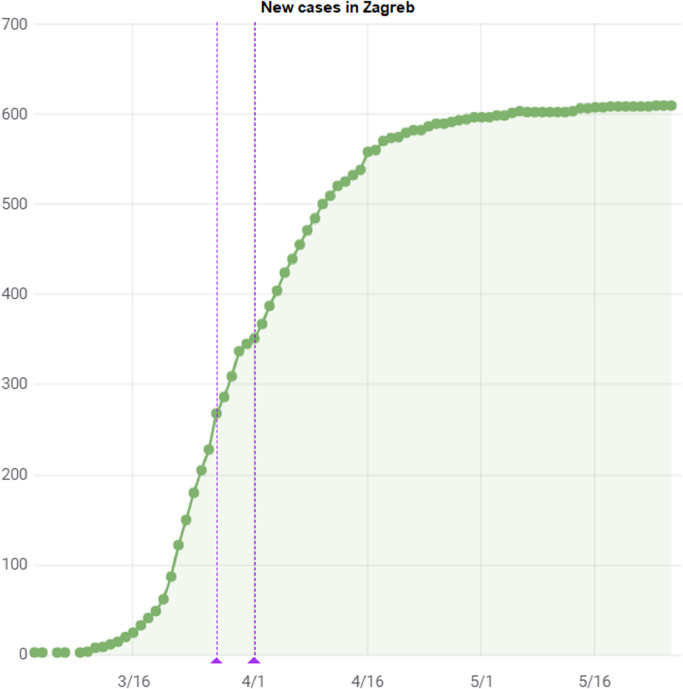

Fig. 2.

New COVID-19 positive cases in Zagreb during the epidemic.

Fig. 1.

Maternity ward in Zagreb being evacuated immediately after the earthquake at 7 am, March 22nd.

The health system braced for imminent impact five to seven days later.

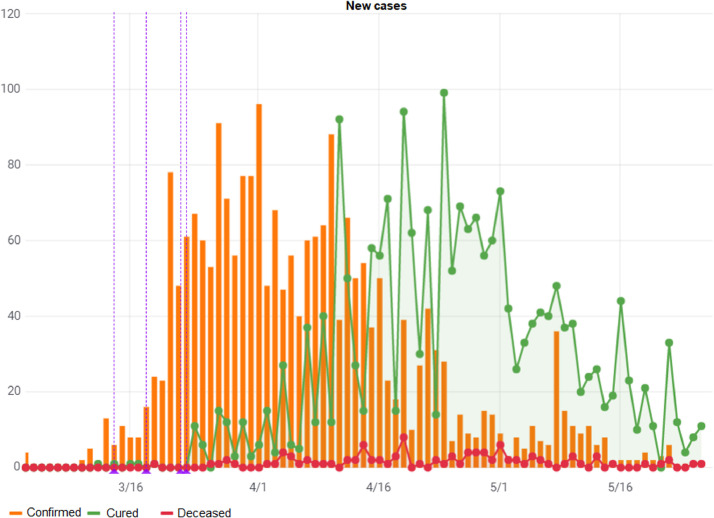

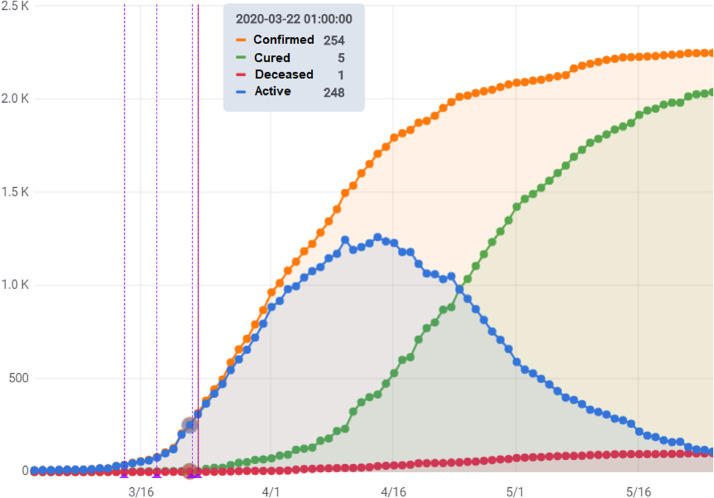

However, it seems that earthquake did not have a significant effect on disease transmission - the number of total COVID-19 cases on March 30th, 8 days later was 790, with a stable average of 60 new daily cases in the whole country, and remained stable for the next ten days, through the 14-day incubation period. It stands at 1182 on April 5th, dropping to around 50 new daily cases in the past several days and dropping sharply after April 15th to virtually no new cases in late May. The average number of confirmed cases in Zagreb alone was 122 on March 22nd, and also dropped significantly in the 14 days’ post-earthquake and stood at 424 total on April 5th, with a linear pandemic curve flattening out in May. The data was accessed through an AI data mining site (https://covid19hr.velebit.ai) linked to official daily government data reports.

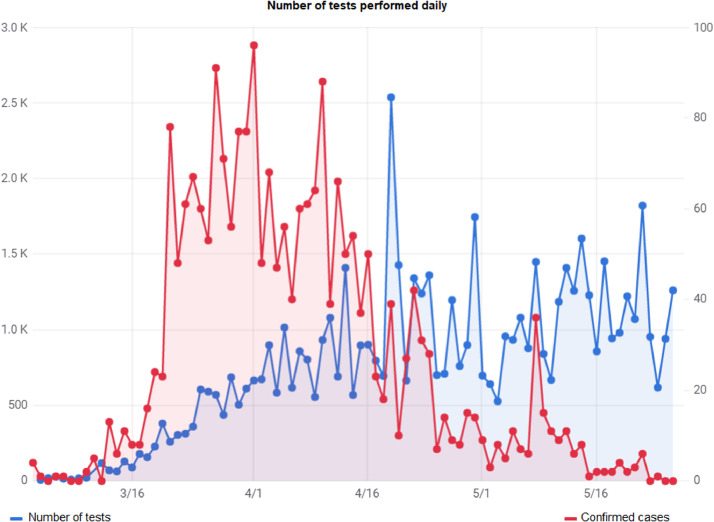

This leads to a conclusion that the earthquake did not have a direct effect on disease spread, which is difficult to explain considering that thousands of people remained in close (involuntary) contact through a period of several days and the earthquake disrupted health care and civil services severely. Possible lack of such effect could be strongly confounded by still widely unknown characteristics of the infectious agent (f.e. the way of spreading, number of mild/asymptomatic forms of infection) and/or response strategies (f.e. selectively applied testing strategy). This may be attributed to changes in national policy for testing, changes in number of conducted test (for example due to resource allocation to earthquake-related event), changes in the reporting system, decrease in number of testing due to disruption in supply-chain of testing consumables or an array of other reasons. But, none of these were altered before, during or after the earthquake. The transmission rate and number of positive cases before and after the earthquake were unhanged, and dropped within a month after the earthquake (Fig. 3, Fig. 4 ). Other reasons for absent disease escalation may be that the baseline level of infection was not high enough to be affected by whatever increased contact and disruption to daily lives the earthquake brought. Relocation of earthquake victims to shelters, (450 people), was made maintaining proper social distancing and disinfection procedures, and the people relocated to rural regions returned within a few days, possibly avoiding disease spread due to limited contact with local inhabitants.

Fig. 3.

Representation of newly diagnosed, cured and deceased patients during the epidemic.

Fig. 4.

Testing frequency during the earthquake and epidemic timeframe.

Similarly, a pandemic co-occurring alongside an earthquake could have significant influences on earthquake related consequences. Because of highly restrictive public health measures being introduced just before the earthquake, human casualties were contained (one earthquake related death was reported). Crisis public management was already in place, and operational because of a pandemic which made response to earthquakes presumably more effective, as is seen from the figures suggesting that the epidemic in Croatia is under control (Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Number of total positive, cured patients and deaths during the epidemic.

The effects of co-occurring disasters are highly complex, and almost certainly not reinforcing, nor additive. In that sense, the influence of social context on disasters can once again be emphasized. Paradoxically, possible negative effects of an earthquake occurring during a pandemic did not materialize, while possible positive effects are certainly possible. In other words, the response to one disaster could have provided a (short-term) preparedness for another. The real, long-term costs of such preparedness may be analyzed by assessing mental health issues as a valid proxy outcome measure of disasters’ recovery process. (Rodríguez et al., 2018, Reifels et al., 2013, Tsutsumi et al., 2015, Généreux et al., 2019) Such a multifaceted traumatic exposures could have a significant long-term effects on mental health, as alongside a deep feeling of uncertainty with limited possibilities for “healthy” coping streaming from pandemic setting, came a similarly distressful feeling of insecurity streaming from earthquakes. (Korman et al., 2019, Horesh and Brown, 2020, Reifels et al., 2013, Lowe et al., 2019, North et al., 2012, North and Pfefferbaum, 2013) In that sense, although the long-term effect of the earthquake occurring alongside the ongoing pandemic cannot be fully currently assessed, it is reasonable to believe that those are going to be more significant than both these adversities occurring apart from each other.

Despite the fact that the current pandemic and its responses are unique, this may present an opportunity to investigate notions as vulnerability and resilience. Within the resilience framework the high frequency of adversity (traumatic) events is often used in argumentation that some may even have positive effects. In that sense, one could even argue that adversity is a precursor of any thriving.

Role of funding source

No funding was received for the preparation of this manuscript.

Authors contribution

MC provided initial idea and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. MC, LS and AK edited, reviewed, and prepared the manuscript for submission. All of the authors contributed to and approved final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

MC have received lecture honoraria from Lundbeck, Sandoz, Janssen, Pliva (Teva) and Alkaloid. DC, AK, and LS have no conflicts of interest to declare

References

- 8 Albrecht F. Natural hazard events and social capital: the social impactof natural disasters. Disasters. 2018;42:336–360. doi: 10.1111/disa.12246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2 Arcaya M, Raker EJ, Waters MC. The social consequences of disasters: individual and community change. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2020;46:111–121. [Google Scholar]

- 14 Auerbach J, Miller BF. COVID-19 Exposes the cracks in our already fragile mental health system. Am J Public Health. 2020:e1–e2. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305699. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11 Bedford J, Enria D, Giesecke J, et al. COVID-19: towards controlling of a pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1015–1018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30673-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4 Benjet C, Bromet E, Karam EG, et al. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychol. Med. 2016;46:327–343. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6 Bonanno GA, Brewin CR, Kaniasty K, Greca AM. Weighing the costs of disaster consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2010;11(1):1–49. doi: 10.1177/1529100610387086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5 Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am. Psychol. 2004;59:20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16 Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17 Brown TM, Fee E. Andrija Stampar: charismatic leader of social medicine and international health. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1383. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.090084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19 Dar O, Buckley EJ, Rokadiya S, Huda Q, Abrahams J. Integrating health into disaster risk reduction strategies: Key considerations for success. Am. J. Public Health. 2014;104:1811–1816. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13 Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10 Fauci AS, Lane HC, Redfield RR. Covid-19 — Navigating the Uncharted. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2002387. [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23 Généreux M, Schluter PJ, Takahashi S, et al. Psychosocial management before, during, and after emergencies and disasters—results from the kobe expert meeting. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1309. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16081309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12 Gostin LO, Friedman EA, Wetter SA. Responding to COVID-19: how to navigate a public health emergency legally and ethically. Hastings Cent Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hast.1090. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15 Horesh D, Brown AD. Traumatic stress in the age of COVID-19: a call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(4):331–335. doi: 10.1037/tra0000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9 Kaniasty K. Social support, interpersonal, and community dynamics following disasters caused by natural hazards. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019;32:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7 Korman MB, Goldberg L, Klein C, et al. Code orange: a systematic review of psychosocial disaster response. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2019;34:S69–S70. [Google Scholar]

- 20 Lowe SR, McGrath JA, Young MN, et al. Cumulative disaster exposure and mental and physical health symptoms among a large sample of gulf coast residents. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32(2):196–205. doi: 10.1002/jts.22392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21 Malilay J, Heumann M, Perrotta D, et al. The role of applied epidemiology methods in the disaster management cycle. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2092–2102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3 Morabia A, Benjamin GC. Preparing and rebuilding after natural disasters: a new public health normal! Am J Public Health. 2018;108(1):9–10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25 North CS, Pfefferbaum B. Mental health response to community disasters: a systematic review. JAMA. 2013;310:507–518. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.107799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24 North CS, Oliver J, Pandya A. Examining a comprehensive model of disaster-related posttraumatic stress disorder in systematically studied survivors of 10 disasters. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(10):e40–e48. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18 Reifels L, Pietrantoni L, Prati G, et al. Lessons learned about psychosocial responses to disaster and mass trauma: An international perspective. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2013;4 doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.22897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1 Rodríguez H, Donner W, Trainor JE. 2nd ed. Springer; Cham, Switzerland: 2018. Handbook of disaster research. [Google Scholar]

- 22 Tsutsumi A, Izutsu T, Ito A, Thornicroft G, Patel V, Minas H. Mental health mainstreamed in new UN disaster framework. Lancet. 2015;2:679–680. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]