Abstract

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) is an emerging febrile systemic disease caused by the HGE agent, an obligatory intracellular bacterium of granulocytes. The pathogenicity- and immunity-related mechanisms of HGE are unknown. In this study, several cytokines generated in human peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) incubated with the HGE agent or a recombinant 44-kDa major surface protein (rP44) of the HGE agent were examined by reverse transcription-PCR and a capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The HGE agent induced expression of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and IL-6 mRNAs and proteins in PBLs in a dose-dependent manner to levels as high as those resulting from Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide stimulation. The kinetics of induction of these three cytokines in PBLs by rP44 and by the HGE agent were similar. Proteinase K treatment of the HGE agent or rP44 eliminated the ability to induce these three cytokines. Induction of these cytokine mRNAs was not dependent on superoxide generation. These results suggest that P44 proteins have a major role in inducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines by PBLs. Expression of IL-8, IL-10, gamma interferon, transforming growth factor β, and IL-2 mRNAs in response to the HGE agent was not remarkable. Among PBLs, neutrophils and lymphocytes expressed IL-1β mRNA but not TNF-α or IL-6 mRNA in response to the HGE agent, whereas monocytes expressed all three of these cytokine mRNAs. These observations suggest that induction of proinflammatory-cytokine gene expression by the major outer membrane protein of the HGE agent in monocytes, which are not the primary host cells of the HGE agent, contributes to HGE pathogenesis and immunomodulation.

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE), a tick-borne zoonosis, was first reported in 1994 and has been increasingly recognized in the United States (2, 4, 29, 30). Evidence of HGE also has been reported in Europe (1, 8, 16, 21, 23). HGE is characterized by fever, chills, headache, myalgia, and laboratory findings such as leukopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver enzyme activities (2, 29, 30). Patients with HGE frequently require prolonged hospitalization, and the disease can be fatal when treatment is delayed due to misdiagnosis or in immunocompromised patients. HGE is caused by infection with the HGE agent, an obligatory intracellular gram-negative bacterium that is in the membrane-bound inclusions of peripheral blood granulocytes of patients (4). The small amounts of ehrlichial organisms detected in the blood of patients suggest that the clinical signs and hematological changes seen in HGE are mediated by proinflammatory-cytokine production by the host.

Recent studies of the HGE agent showed that 38- to 49-kDa proteins of this organism are dominant antigens recognized by the sera from patients with HGE (33). We have demonstrated that these proteins are present in the outer membranes of our five human patient isolates of the HGE agent and of a tick isolate (USG3) of the granulocytic Ehrlichia sp. (15). More recently, we cloned, sequenced, and expressed in Escherichia coli a gene encoding a 44-kDa protein of the HGE agent (32). In the present study, we examined expression of mRNAs of several proinflammatory and other cytokines, as well as their products, by human peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) incubated with the HGE agent or a recombinant 44-kDa major outer membrane protein (rP44). We also examined whether neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes are responsible for generation of these proinflammatory cytokines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultures.

HGE agent HZ (24) was propagated in HL-60 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, Ga.), 1% minimal essential medium nonessential amino acid mixture (GIBCO-BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.), 1 mM minimal essential medium sodium pyruvate (GIBCO-BRL), and 2 mM l-glutamine (GIBCO-BRL). Ehrlichia chaffeensis Arkansas in THP-1 cells (American Type Culture Collection) was propagated in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM l-glutamine. All cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2–95% air atmosphere. Infected cells were examined by using Diff-Quik stain (modified Giemsa; Baxter Scientific Products, Obetz, Ohio) after centrifugation of cells onto microscope slides in a cytocentrifuge (Cytospin 3; Shandon, Inc., Pittsburgh, Pa.).

Preparation of human PBLs, neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes.

Peripheral blood buffy coats from healthy donors were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min. Erythrocytes in the pellet were lysed in sterile 0.83% NH4Cl solution for 3 min at room temperature, and PBLs were washed twice by centrifugation (500 × g for 5 min) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2.7 mM KCl, and 1.8 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.2]). To separate neutrophils, buffy coats diluted 1:2 in PBS were layered on Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) and centrifuged for 15 min at 750 × g and room temperature as previously described (6). The pellet was washed twice in PBS at 400 × g for 5 min and suspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS. The cell suspension was layered on top of a 62% Percoll (Pharmacia) solution and centrifuged for 15 min at 400 × g and room temperature, and the band of neutrophils was collected. The percentage of neutrophils in the preparation was >95% as assessed by morphological examination of Diff-Quik-stained cells. The viabilities of both the PBL and neutrophil preparations were >95% as assessed by the trypan blue dye exclusion test. To obtain adherent monocyte and nonadherent lymphocyte populations, the interface of the centrifuged Ficoll-Paque gradient was collected and incubated at 37°C for 2 h in 150-mm-diameter culture dishes (Corning, Corning, N.Y.) containing RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. All experiments were independently repeated two to six times, on different days, using PBLs and subpopulations of PBLs derived from different donors, and the host-cell-free HGE agent was freshly prepared each time. Donor cells were never mixed, and each donor leukocyte assay included positive and negative controls to ensure the quality of both the leukocytes and the HGE agent preparation.

Preparation of host-cell-free ehrlichiae.

When >90% of the host cells were infected, the cell suspension (107 cells in 5 ml of RPMI 1640 medium) was sonicated by using an ultrasonic processor (model W-380; Heat Systems, Farmingdale, N.Y.) under conditions predetermined to be minimally damaging to ehrlichiae (setting 2 at 20 kHz for 7 s) and centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min. The supernatants, containing host-cell-free ehrlichiae, were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 × g and 4°C. Because the HGE agent and E. chaffeensis are small and multiply as dense microcolonies, it is impractical to accurately count individual organisms. Therefore, the number of host-cell-free ehrlichiae was estimated each time by using the following formula: number of ehrlichial organisms = total number of infected cells × average number of morulae in an infected cell (typically 5 for the HGE agent and 3.6 for E. chaffeensis) × average number of ehrlichial organisms in a morula (typically 19 for the HGE agent and 23 for E. chaffeensis) × percentage of ehrlichiae recovered as host cell free (typically 50% as determined by using metabolically [35S]methionine-labeled ehrlichiae [25]).

Treatment of cells.

Either PBLs or subpopulations of PBLs (107 cells) in 1 ml of RPMI 1640 medium in a well of a 24-well plate were incubated at 37°C with each treatment. For the HGE agent, 1011 ehrlichial organisms in 1 ml of cold RPMI 1640 medium were freshly prepared each time, and ∼100 ehrlichial organisms per cell were used in all experiments, except for the dose-response experiment. rP44 was induced in pEP44-transformed E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS by adding 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (GIBCO-BRL) and purified by using a His-Bind buffer kit (Novagen, Inc., Madison, Wis.) as previously described (15, 32) and was used at 1 μg/ml. Endotoxin contamination of rP44 preparations and RPMI 1640 medium was tested by Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) assay (BioWhittaker, Inc., Walkersville, Md.). To remove rP44 from the rP44 preparation, 10 μl of a 100-μg/ml rP44 solution was incubated at room temperature for 1 h with nitrocellulose membranes coated (or not coated [control]) with 100 μg of monoclonal antibody (MAb) 5C11 from ascites fluid or culture supernatant (15). Heat-killed HGE agent and boiled rP44 were prepared by boiling for 10 min. For proteinase K treatment, either the HGE agent (1011 bacteria) or rP44 (100 μg) was incubated with 1 mg of proteinase K (GIBCO-BRL) in 1 ml of distilled water at 60°C for 2 h. After incubation, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was added, and after 10 min the HGE agent was washed three times in RPMI 1640 medium (19). To prevent the loss of any soluble components after addition of 1 mM PMSF, proteinase K-treated rP44 was not washed and was used at 1 μg/ml. As a control for this treatment, PBLs (107 cells/ml) were incubated with the mixture of proteinase K and PMSF. As a positive control, lipopolysaccharide (LPS; E. coli O127:B8; Difco, Detroit, Mich.) was used at 1 μg/ml. As negative controls, PBLs in RPMI 1640 medium were incubated with 10 μl of the medium supplemented with 10% FBS containing either no lysate or the lysate derived from 105 uninfected HL-60 cells or THP-1 cells. Cells were incubated for 2 h with each treatment, except for the time course experiment. RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% FBS was used for the time course experiment. To investigate the role of reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI), PBLs (107 cells) were preincubated with superoxide dismutase (SOD; Sigma) at 60 U/ml for 40 min and were further incubated for 2 h with the HGE agent (100 bacteria/cell) in the presence of SOD.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis.

Total RNA was extracted from either PBLs or subpopulations of cells (107 cells each) by using TRIzol reagent (GIBCO-BRL) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The concentration and purity of the RNA were determined by measuring the A260 and the A260/A280 ratio with a GeneQuant II RNA and DNA calculator (Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, N.J.). The RNA was stored at −85°C until used. Total cellular RNA (2 μg) was reverse transcribed in a 30-μl reaction mixture containing 1× reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2), 0.5 mM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1 U of an RNase inhibitor (GIBCO-BRL), 1.5 μM oligo(dT) primer, and 10 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (GIBCO-BRL) at 42°C for 1 h. The reaction was terminated by heating the reaction mixture at 94°C for 5 min, and the cDNA was used in the PCR.

PCR.

The cDNA (2 μl) was amplified in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing 1× PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2), 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 0.4 μM (each) 3′ and 5′ primers (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.) in a DNA thermal cycler (model 480; Perkin-Elmer Corp., Norwalk, Conn.). Positive controls for all cytokines were obtained from Clontech. To reduce nonspecific priming, all PCRs were performed by the hot-start method. Taq DNA polymerase (2 U; GIBCO-BRL) was added after incubation of the mixture at 94°C for 5 min. One PCR cycle consisted of denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, annealing at 60°C for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 2 min. PCR was conducted for 25 cycles in all experiments, except for interleukin-8 (IL-8) mRNA (20 cycles). The final extension was for 7 min. After PCR, 10 μl of PCR product was electrophoresed in a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (EtBr; final concentration, 0.5 μg/ml). DNA size markers (HaeIII fragments of φX174 replicative-form [RF] DNA; GIBCO-BRL) providing bands of from 1,353 to 72 bp were run in parallel.

For competitive PCR, competitive internal standards, i.e., MIMICs for IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-6, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH), were synthesized with a MIMIC construction kit (Clontech). The optimum amounts of MIMICs were determined and added to the reaction mixtures as follows: 7.5 amol for G3PDH, 5 amol each for IL-1β and IL-6, and 2.5 amol for TNF-α. The MIMIC PCR conditions were the same as those for non-MIMIC PCR. Amplified target and MIMIC DNA bands were identified by their predicted positions in the gel. The amounts of the target and MIMIC PCR products were determined by a gel video system (Gel Print 2000i; BioPhotonics Corp., Ann Arbor, Mich.), using image analysis software (ImageQuant; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). The ratio of target to each MIMIC was calculated and normalized against the amount of G3PDH mRNA in the corresponding sample.

Capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Duplicate 24-well plates containing PBLs (106/ml of RPMI 1640 medium/well) were treated in triplicate wells for 24 h. After 24 h of incubation, one set of cultures was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min, and supernatant was collected into microcentrifuge tubes and then assayed for secreted-cytokine levels. IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 levels were measured by using human cytokine immunoassay kits (Quantikine; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

RESULTS

Cytokine induction in human PBLs.

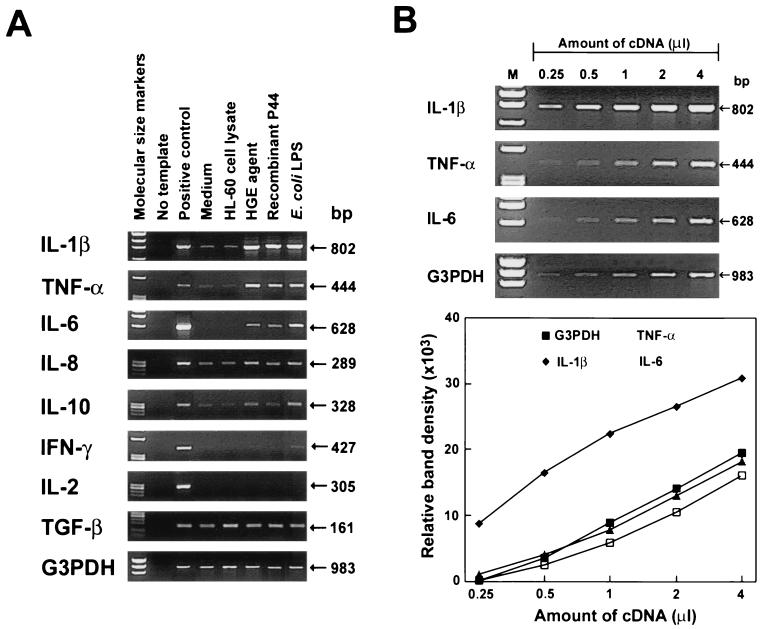

Expression of several cytokine (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, gamma interferon [IFN-γ], TNF-α, and transforming growth factor β [TGF-β]) mRNAs and one chemokine (IL-8) mRNAs in PBLs from several donors was measured by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. Cellular cytokine compositions and levels of cytokine gene expression in PBLs from six donors are shown in Table 1. Figure 1A shows RT-PCR results for donor no. 2 in Table 1. PCR products were not obtained for any of the negative controls lacking reverse transcriptase, indicating that contamination of RNA with genomic DNA was negligible. Constitutively expressed G3PDH mRNA served as a control for the amount of input RNA across the samples in each experiment. RPMI 1640 medium alone or HL-60 cell lysate was used as a negative control, since the HGE agent was cultivated in HL-60 cells and thus the HGE agent preparation contains HL-60 cell debris. There was no significant cytokine gene expression in these negative controls, with the exception of TGF-β. E. coli LPS, used as a positive control, consistently induced IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNA expression (six of six blood donors) in human PBLs (Fig. 1A). A linear reaction was obtained with a PCR cycle number of 25 (20 for IL-8 mRNA). For example, relationships between densities of target PCR products and amounts of cDNA from mRNA extracted from PBLs incubated with E. coli LPS for 2 h (r values) were 0.88 for IL-1β, 0.96 for TNF-α, 0.98 for IL-6, and 0.95 for G3PDH (Fig. 1B). The freshly prepared host-cell-free HGE agent (approximately 100 bacteria/cell) and the rP44 preparation (1 μg/ml) consistently induced IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNA expression to levels as high as those induced by E. coli LPS (1 μg/ml) stimulation (Fig. 1A) in all six healthy blood donors (Table 1) examined after 2 h of incubation. The remaining cytokines examined (IL-8, IL-10, IFN-γ, IL-2, and TGF-β) were weakly or not induced by the HGE agent, rP44, or E. coli LPS at 2 h of stimulation (Table 1; Fig. 1A). As reported previously for whole blood (7) and for purified neutrophils (3), IL-8 mRNA was weakly expressed in PBLs with the medium-alone control. IL-8 mRNA was weakly induced in PBLs with the HGE agent or rP44 (one of four donors), as well as with LPS (four of four donors). IL-10 mRNA expression was weakly upregulated either with the HGE agent or rP44 (three of five donors) or with E. coli LPS (five of five donors). IFN-γ mRNA expression was weakly upregulated with the HGE agent or rP44 (one of four donors), as well as with E. coli LPS (two of four donors). TGF-β mRNA was constitutively expressed at high levels and was not induced in any of the five individuals tested, regardless of the treatment. IL-2 mRNA was not detectable with any treatment in any of the five individuals tested.

TABLE 1.

Cytokine mRNA expression by individual classes of human PBLs in response to the HGE agent or rP44

| Donor no. | Composition of PBLsa

|

Cytokine mRNA inductionb

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | Lymphocytes | Monocytes | Eosinophils | IL-1β | TNF-α | IL-6 | IL-10 | IFN-γ | IL-2 | IL-8 | TGF-βc | |

| 1 | 63.8 ± 0.9 | 29.4 ± 0.4 | 6.1 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2 | 66.2 ± 0.7 | 24.5 ± 0.5 | 8.3 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| 3 | 65.2 ± 0.4 | 27.3 ± 0.4 | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| 4 | 64.8 ± 0.5 | 27.2 ± 0.6 | 6.9 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| 5 | 61.1 ± 0.6 | 30.2 ± 0.4 | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | + | + | + | + | ND | − | ND | − |

| 6 | 62.9 ± 1.1 | 28.9 ± 1.2 | 7.4 ± 1.0 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | + | + | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Values are mean percentages ± standard deviations of data from three slides.

+, induced; −, not induced; ND, not done.

Constitutively expressed.

FIG. 1.

Cytokine mRNA expression in human PBLs exposed to the HGE agent or rP44. (A) Cytokine mRNA expression in human PBLs exposed to the HGE agent (100 bacteria/cell), rP44 (1 μg/ml), or E. coli LPS (1 μg/ml) for 2 h. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to RT-PCR. The cDNAs, in quantities normalized against G3PDH mRNA levels in corresponding samples, were amplified for 25 cycles (20 cycles for IL-8 mRNA), and PCR products were resolved on agarose gels containing EtBr. DNA size markers (HaeIII fragments of φX174 RF DNA) were run in the leftmost lanes. The data presented (donor no. 2 in Table 1) are representative of six donors (Table 1) who had similar results for IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and LPS. (B) Linearity of RT-PCR. Different amounts of cDNA from human PBLs (107 cells) incubated with E. coli LPS (1 μg/ml) for 2 h were amplified for 25 cycles. The PCR products were resolved on agarose gels containing EtBr. DNA size markers (HaeIII fragments of φX174 RF DNA) were run in the leftmost lanes (M). The data presented (donor no. 1 in Table 1) are representative of two independent experiments (donor no. 1 and 2) that gave similar results. The lower panel shows a plot of the relative band densities of the PCR products, recorded by a gel video system and analyzed by an image analysis software, against the amounts of cDNA present in the PCR.

After incubation of PBLs with the HGE agent or rP44 for 24 h, levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 similar to those obtained with E. coli LPS stimulation were detected by capture ELISA (Table 2). The medium alone did not induce PBLs to produce IL-1β or IL-6, whereas low levels of TNF-α (<18 pg/ml) were detected (Table 2). The TNF-α level, however, was insignificant compared with the ∼120-fold increase in TNF-α concentration that occurred in response to the HGE agent, rP44, or E. coli LPS (Table 2). HL-60 cell debris also did not have a significant influence on cytokine production by PBLs. Overall, these findings at the protein level were consistent with the RT-PCR results (Fig. 1A; Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 2.

Cytokine production by human PBLs in response to HGE agent or rP44a

| Treatment | Concnb (pg/ml) of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | TNF-α | IL-6 | |

| Medium | <1 | 15 ± 1 | <0.7 |

| HL-60 cell lysate | 10 ± 1 | 18 ± 2 | <0.7 |

| HGE agent | 998 ± 57 | 2,517 ± 296 | 1,059 ± 51 |

| Proteinase K-treated HGE agent | 7 ± 1 | 27 ± 4 | <0.7 |

| Heat-killed HGE agent | 253 ± 3 | 270 ± 2 | 301 ± 18 |

| rP44 | 877 ± 30 | 1,873 ± 277 | 1,118 ± 40 |

| Proteinase K-treated rP44 | 34 ± 1 | 99 ± 4 | <0.7 |

| Boiled rP44 | 100 ± 1 | 775 ± 10 | 685 ± 3 |

| E. coli LPS | 899 ± 12 | 2,121 ± 347 | 929 ± 77 |

Each cytokine level was measured by using a capture ELISA kit. Human PBLs (106 cells) were incubated for 24 h with either freshly freed HGE agent (100 bacteria per cell) or rP44 (1 μg/well) including other treatments (1 μg/well).

Culture supernatants were used to measure the cytokine levels because there were no differences between the levels in culture supernatant and those in supernatant plus cell lysate. The assay detection limits of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 were 1, 4.4, and 0.7 pg/ml, respectively. The values are the means ± standard deviations of data from triplicate wells. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

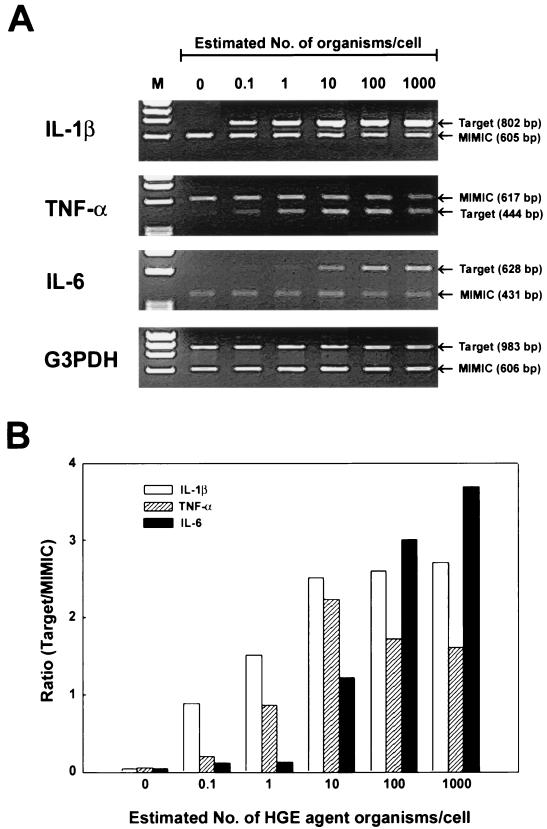

Dose response of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNA expression in PBLs to the HGE agent as determined by competitive RT-PCR.

The levels of expression of cytokine IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNAs in PBLs in response to the freshly prepared host-cell-free HGE agent were dose dependent (Fig. 2). Both IL-1β and TNF-α mRNAs were maximally induced at 10 bacteria/cell, whereas IL-6 mRNA was maximally induced at 1,000 organisms per cell (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Dose-dependent induction of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNA expression in human PBLs. (A) PBLs were incubated for 2 h with different amounts of the HGE agent. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to the competitive RT-PCR. The PCR products were resolved on agarose gels containing EtBr. DNA size markers (HaeIII fragments of φX174 RF DNA) were run in the leftmost lanes (M). (B) Relative amounts of cytokine mRNAs expressed in human PBLs in response to the HGE agent. Band densities were recorded by a gel video system and analyzed by an image analysis software, and ratios of target to MIMIC PCR products were plotted against the estimated HGE agent numbers per cell. The amounts of cDNAs were normalized against G3PDH mRNA levels in corresponding samples. The data presented (donor no. 2 in Table 1) are representative of two independent experiments (donor no. 2 and 3 in Table 1) that gave similar results.

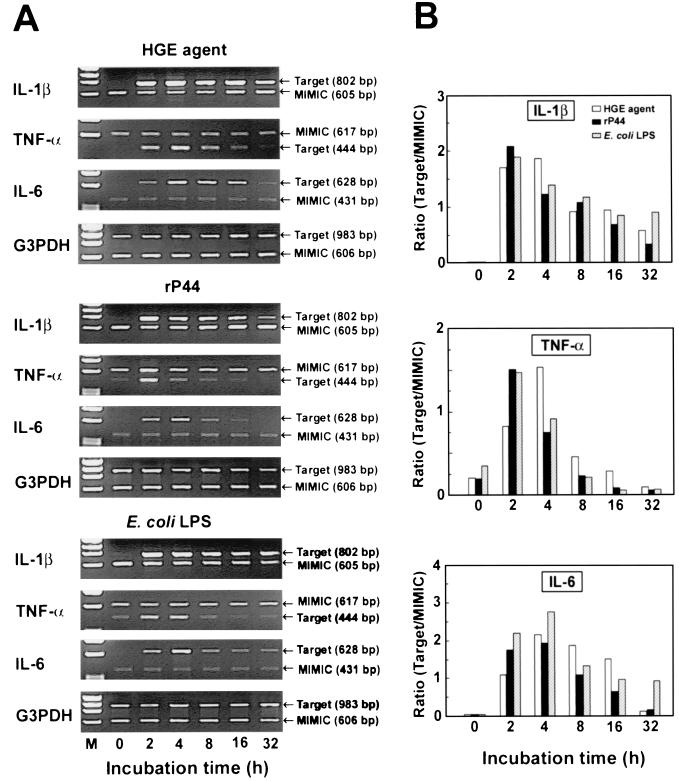

Time course analysis of cytokine mRNA expression in PBLs.

IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNA expression was maximally induced at 2 to 4 h, and their levels were significantly elevated at 16 to 32 h of incubation with the HGE agent, rP44, or E. coli LPS (Fig. 3). Expression of IL-10 and IFN-γ mRNAs in response to the HGE agent increased slightly and peaked at 4 h in PBLs when the expression was upregulated at 2 h. However, when IL-10 or IFN-γ mRNA expression was not upregulated at 2 h, it was not upregulated at 4 h (data not shown). Therefore, the lack of or weak IL-10 and IFN-γ mRNA expression in PBLs at 2 h does not appear to be due to a delayed response to the HGE agent.

FIG. 3.

Time course analysis of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNA expression in human PBLs in response to the HGE agent (100 bacteria/cell), rP44 (1 μg/ml), or E. coli LPS (1 μg/ml). (A) Human PBLs were incubated for the indicated time periods. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to the competitive RT-PCR. The PCR products were resolved on agarose gels containing EtBr. DNA size markers (HaeIII fragments of φX174 RF DNA) were run in the leftmost lanes. (B) Relative amounts of cytokine mRNAs expressed. Band densities were recorded by a gel video system and analyzed by an image analysis software, and the ratios of target to MIMIC PCR products were plotted against the incubation time. The amounts of cDNAs were normalized against G3PDH mRNA levels in corresponding samples. The data presented (donor no. 3 in Table 1) are representative of two independent experiments (donor no. 2 and 3) that gave similar results.

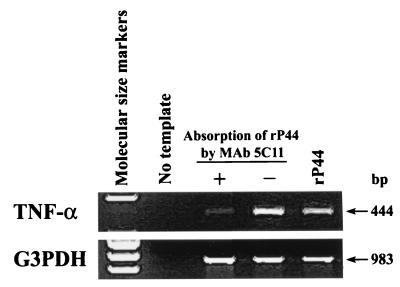

Examination of rP44 preparation for contamination by E. coli endotoxin and other cytokine-inducing components.

Analysis of the rP44 preparation and the culture medium by LAL assay revealed that the endotoxin activity of the former (at 10 μg/ml) was 0.24 endotoxin units (EU; 0.024 ng of LPS)/ml and that of the medium was 0.20 EU (0.020 ng of LPS)/ml. The endotoxin detection sensitivity of the assay was 0.1 EU (0.010 ng of LPS)/ml. After removal of rP44 protein from the rP44 preparation by adsorption with MAb 5C11, which was previously found to specifically react with native P44 and rP44 (15), the preparation was negative for TNF-α mRNA induction (Fig. 4). This was not due to the loss of rP44 by nonspecific adsorption of rP44 to the nitrocellulose membrane, since an rP44 preparation incubated with an uncoated nitrocellulose membrane was capable of full induction of TNF-α mRNA expression in human PBLs (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Examination of rP44 preparation for contamination of endotoxin and other cytokine-inducing components. rP44 preparation was incubated with a nitrocellulose membrane coated with a MAb against P44 (5C11) (+) or an uncoated membrane (−). The solutions were then added to PBLs and incubated at 37°C for 2 h, and TNF-α mRNA was examined by RT-PCR. The PCR products were resolved on agarose gels containing EtBr. DNA size markers (HaeIII fragments of φX174 RF DNA) were run in the leftmost lanes. The data presented (donor no. 5 in Table 1) are representative of two independent experiments (donor no. 5 and 6) that gave similar results.

HGE agent components required for expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6.

RT-PCR and capture ELISA revealed that the protein in the HGE agent and in the rP44 was required for induction of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6, because proteinase K treatment of the HGE agent or rP44 preparation significantly reduced the levels of expression of these three cytokine mRNAs and the resulting proteins (Fig. 5; Table 2). As a negative control, proteinase K plus PMSF had no influence on PBL cytokine gene expression (data not shown). Boiling of the HGE agent or rP44 also significantly reduced the generation of these proinflammatory cytokines by PBLs, but to a lesser degree (Fig. 5; Table 2). ROI generated in PBLs in response to LPS or other bacterial components are known to activate NF-κB, which is a typical transcription factor involved in proinflammatory-cytokine gene expression (11, 20, 26). Because pretreatment of PBLs with SOD did not prevent proinflammatory-cytokine gene expression in PBLs exposed to the HGE agent (Fig. 5), induction of these cytokines was deemed independent of superoxide generation.

FIG. 5.

Influences of various treatments on expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNAs in human PBLs exposed to the HGE agent (100 bacteria/cell), rP44 (1 μg/ml), or E. coli LPS (1 μg/ml). To examine which components of the HGE agent are responsible for expression of the three proinflammatory-cytokine mRNAs, PBLs (107 cells) were incubated for 2 h with HGE agent that had been subjected to different treatments as described in Materials and Methods. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to RT-PCR. The amounts of cDNAs used were normalized against G3PDH mRNA levels in corresponding samples. The PCR products were resolved on agarose gels containing EtBr. DNA size markers (HaeIII fragments of φX174 RF DNA) were run in the leftmost lanes. The data presented (donor no. 4 in Table 1) are representative of three independent experiments (donor no. 3 to 5) that gave similar results.

Determination of cell populations responding to the HGE agent or rP44.

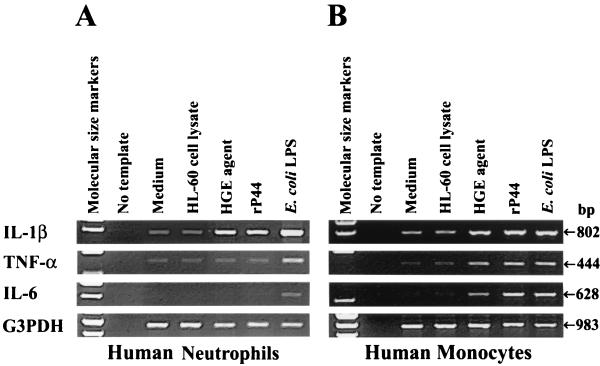

When PBLs were incubated with the HGE agent or rP44 for 2 h and neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes were separated, only IL-1β mRNA expression was induced in neutrophils and lymphocytes (neutrophil results are shown in Fig. 6A) whereas expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNAs was induced in monocytes (Fig. 6B). E. coli LPS, a positive control, induced the expression of all three proinflammatory cytokines in neutrophils and monocytes, although IL-6 mRNA expression was weaker in neutrophils than in monocytes, as previously reported by others (3). The proportion of neutrophils in the preparation was >95%. Similar results were obtained when neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes were first separated and then individually incubated with the HGE agent (data not shown). These results indicate that the monocytes present in the PBL preparation were responsible for expression of TNF-α and IL-6 mRNAs whereas IL-1β was generated by all three types of cell populations in response to the HGE agent or rP44.

FIG. 6.

Cytokine mRNA expression in human neutrophils and monocytes. (A) Human neutrophils purified (>95%) by Ficoll-Paque and Percoll gradient centrifugation were used for IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNA expression. Neutrophils (107 cells) were incubated for 2 h with the HGE agent (100 bacteria/cell), rP44 (1 μg/ml), or E. coli LPS (1 μg/ml). The data presented (donor ID 4 in Table 1) are representative of two independent experiments (donor no. 4 and 5) that gave similar results. (B) Purified (>95%) monocytes (107 cells) were incubated for 2 h under the stimulation conditions used for the neutrophils. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to RT-PCR. The amounts of cDNAs used were normalized against G3PDH mRNA levels in corresponding samples. The PCR products were resolved on agarose gels containing EtBr. DNA size markers (HaeIII fragments of φX174 RF DNA) were run in the leftmost lanes. The data presented (donor ID 5 in Table 1) are representative of two independent experiments (donor no. 5 and 6) that gave similar results.

IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNA expression in human PBLs exposed to E. chaffeensis.

E. chaffeensis, a monocytotropic ehrlichia, causes human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME), which is characterized by clinical signs and hematological abnormalities similar to those of HGE (29). However, we previously found that E. chaffeensis induces expression of IL-1β mRNA but does not induce expression of TNF-α or IL-6 mRNA in isolated human peripheral blood monocytes (17). To compare cytokine gene expression in response to E. chaffeensis with that in response to the HGE agent under the same experimental conditions, expression of these three proinflammatory cytokine mRNAs in response to E. chaffeensis (100 bacteria/cell) was examined in PBLs. In PBLs, as in isolated monocytes, only IL-1β mRNA expression was induced in response to E. chaffeensis; expression of TNF-α and IL-6 mRNAs was not induced (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNAs in human PBLs exposed to freshly released E. chaffeensis. PBLs (107 cells) were incubated with E. chaffeensis (100 bacteria/cell), the lysate of uninfected THP-1 cells in which E. chaffeensis had been cultivated, or medium for 2 h. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to RT-PCR. The amounts of cDNA used were normalized against G3PDH mRNA levels in corresponding samples. PCR products were resolved on agarose gels containing EtBr. DNA size markers (HaeIII fragments of φX174 RF DNA) were run in the leftmost lanes. The data presented (donor no. 4 in Table 1) are representative of two independent experiments (donor no. 3 and 4) that gave similar results.

DISCUSSION

In this study we demonstrated that the HGE agent is capable of strongly inducing the expression of proinflammatory-cytokine (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6) mRNAs and proteins in human PBLs in vitro. Individual human genetic factors do not appear to influence these three cytokine responses since PBLs from all donors tested responded to the HGE agent in a similar fashion. Expression of the remaining cytokines examined was weakly or not induced by the HGE agent, and responses differed among donors. Whether these low levels of cytokine expression contribute to individual variation in clinical manifestations of HGE is unknown. The cell population that produced TNF-α and IL-6 in response to the HGE agent was the human monocyte, whereas IL-1β mRNA was expressed by monocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes. Thus, although the HGE agent does not usually infect monocytes, it interacts with and can strongly induce proinflammatory cytokine expression in monocytes. Intracellular growth of various bacteria was influenced by proinflammatory cytokines (14). It is not known whether these proinflammatory cytokines influence the growth of the HGE agent, but this strong proinflammatory signal transduction by the HGE agent in monocytes may be one of reasons why this agent cannot infect monocytes. The fact that E. chaffeensis, which preferentially infects monocytes, does not induce TNF-α or IL-6 expression in monocytes (17) supports this speculation.

We demonstrated that rP44 induces the expression of these three proinflammatory cytokines, suggesting that the major outer membrane protein P44 of the HGE agent is responsible for proinflammatory-cytokine generation. The proinflammatory activity of rP44 was not due to contamination with LPS or other components of E. coli in the rP44 preparation, since (i) the endotoxin level in the rP44 preparation was 0.24 EU (0.024 ng of LPS)/ml and that in RPMI 1640 medium was 0.20 EU (0.020 ng of LPS)/ml by the LAL assay, (ii) preabsorption of the rP44 preparation with MAbs specific to both native P44 and rP44 completely removed the activity required to induce proinflammatory-cytokine expression, and (iii) proteinase K or heat treatment eliminated the ability of rP44 to induce the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. P44 is one of scores of homologous major outer membrane proteins (OMPs) of the HGE agent encoded by a multigene family (32, 33). Approximately 18 polymorphic p44 homologues were identified in the HGE agent HZ strain (31). These P44 proteins consist of a single central hypervariable region of approximately 94 amino acid residues which is flanked by two conserved regions, of approximately 52 and approximately 56 amino acids (31). rP44 of the present study lacks one-third of P44 at the C terminus, including the second (∼56-amino-acid) conserved region, suggesting that this region is not essential for proinflammatory-cytokine gene expression in human PBLs. We are in the process of comparing the products of systematically mutated p44 in order to deduce the minimum peptide sequence of P44 required for proinflammatory-cytokine gene expression in human PBLs. Since p44 homologues are differentially expressed in cell culture and patients (31), it is also of importance to compare the abilities of different p44 gene products to induce proinflammatory-cytokine gene expression. The differential expression of p44 genes may influence levels of proinflammatory-cytokine gene expression and thus the severity and outcome of the disease as well as the development of immunity to the HGE agent in the host.

Bacterial membrane proteins such as porin and lipoprotein are known to induce the expression of proinflammatory cytokines (12). Isolated porins from Salmonella typhimurium, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Helicobacter pylori were shown to stimulate monocytes and lymphocytes to release a range of proinflammatory and immunomodulatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and IFN-γ (10, 27, 28), although it remains to be determined whether P44s, the immunodominant major OMPs, have a porin-like function. By using MAbs to P44 and immunogold labeling, we previously demonstrated that antigenic epitopes of P44 proteins are present on the ehrlichial surface and on the ehrlichial inclusion membrane (15). The mechanism by which P44 proteins are localized on the inclusion membrane is unknown, but this localization suggests that monocytes and lymphocytes are not necessarily interacting with P44 on the surface of the intact HGE agent but may be interacting with P44s released from the organisms.

Induction of proinflammatory-cytokine gene expression by LPS or various infectious agents may be mediated by ROI generated by monocytes or neutrophils, which in turn activate transcription factor NF-κB (11, 20, 26). We found that proinflammatory-cytokine gene expression in human PBLs was not dependent on ROI. This result is in agreement with our finding that the HGE agent does not induce superoxide generation by human neutrophils (J. Mott and Y. Rikihisa, Abstr. 99th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. D/B-128, p. 234, 1999).

The high levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 generated in the blood of patients exposed to P44s of the HGE agent may be responsible for the clinical signs and hematological abnormalities associated with HGE. Our dose-response data reveal that IL-1β and TNF-α generation may be fast whereas IL-6 generation may require a larger inoculum of the HGE agent or occur at a later stage, after multiplication of the HGE agent to a sufficient level. We previously studied cytokine generation by human monocytes in response to E. chaffeensis (17, 18). Although the clinical signs and hematological abnormalities of HGE and HME are similar (2, 9, 13), cytokine generation in human PBLs or monocytes in response to the HGE agent was different from that in response to E. chaffeensis in several ways. First, for E. chaffeensis, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 generation at a level comparable to that seen with E. coli LPS stimulation requires antibody against E. chaffeensis (18), whereas high-level IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 generation occurs in response to the HGE agent in the absence of the specific antibody. Second, E. chaffeensis strongly induces expression of IL-8 and IL-10 mRNAs in human monocytes, but the HGE agent does not. Third, neither viability nor protein of E. chaffeensis is required for induction of IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-10 (17), but the protein of the HGE agent is primarily responsible for IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 generation. We cloned 28-kDa major OMPs of E. chaffeensis, which are also encoded by a multigene family (22). The protein structure and the gene arrangement of the major OMPs are distinct (22) from those of P44s, suggesting that these structural differences between major OMPs of the HGE agent and E. chaffeensis may be partly responsible for these different cytokine responses in PBLs. Furthermore, our present and previous (17, 18) studies suggest that HGE patients develop clinical signs independent of development of anti-HGE antibodies whereas in HME patients anti-HME antibody development exacerbates the clinical signs. In agreement with this speculation, approximately 50% (four of eight) (9) or 33% (three of nine) (5) of HME patients had immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) titers of >64 by the first IFA test when a pair of serum specimens was available. On the other hand, 25% (two of eight) (13) or 0% (zero of nine) (33) of HGE patients had IFA titers of >64 or 80 by the first IFA when a pair of serum specimens was available.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants AI30010 and AI40934 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bakken J S, Krueth J, Tilden R L, Dumler J S, Kristansen R E. Serologic evidence of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Norway. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;15:829–832. doi: 10.1007/BF01701530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakken J S, Krueth J, Wilson-Nordskog C, Tilden R L, Asanovich K, Dumler J S. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. JAMA. 1996;275:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassatella M A. Cytokines produced by polymorphonuclear neutrophils: molecular and biological aspects. R. G. Austin, Tex: Landes Company; 1996. Production of specific cytokines by neutrophils in vitro; pp. 59–111. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen S-M, Dumler J S, Bakken J S, Walker D H. Identification of a granulocytotropic Ehrlichia species as the etiological agent of human disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:589–595. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.589-595.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Childs J E, Sumner J W, Nicholson W L, Massung R F, Standaert S M, Paddock C D. Outcome of diagnostic tests using samples from patients with culture-proven human monocytic ehrlichiosis: implications for surveillance. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2997–3000. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.2997-3000.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colatta F, Orlando S, Fadlon E J, Sozzani S, Matteucci C, Mantovani A. Chemoattractants induce rapid release of interleukin 1 type II decoy receptor in human polymorphonuclear cells. J Exp Med. 1995;181:2181–2188. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeForge L E, Kenney J S, Jones M L, Warren J S, Remick D G. Biphasic production of IL-8 in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated human whole blood. Separation of LPS- and cytokine-stimulated components using anti-tumor necrosis factor and anti-IL-1 antibodies. J Immunol. 1992;148:2133–2141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dumler J S, Dotevall L, Gustafson R, Granström M. A population-based seroepidemiologic study of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis and Lyme borreliosis on the west coast of Sweden. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:720–722. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.3.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumler J S, Dawson J E, Walker D H. Human ehrlichiosis: hematology and immunohistologic detection of Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Hum Pathol. 1993;24:391–396. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90087-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galdiero F, Cipollaro de L'Ero G, Benedetto N, Galdiero M, Tufano M A. Release of cytokines induced by Salmonella typhimurium porins. Infect Immun. 1993;61:155–161. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.155-161.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giri D K, Mehta R T, Kansal R G, Aggarwal B B. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex activates nuclear transcription factor-κB in different cell types through reactive oxygen intermediates. J Immunol. 1998;161:4834–4841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson B, Poole S, Wilson M. Bacterial modulins: a novel class of virulence factors which cause host tissue pathology by inducing cytokine synthesis. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:316–341. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.316-341.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horowitz H W, Aguero-Rosenfeld M E, McKenna D F, Holmgren D, Hsieh T-C, Varde S A, Dumler J S, Wu L M, Schwartz I, Rikihisa Y, Wormser G P. Clinical and laboratory spectrum of culture-proven human granulocytic ehrlichiosis: comparison with culture-negative cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:1314–1317. doi: 10.1086/515000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanangat S, Meduri G U, Tolley E A, Patterson D R, Meduri C U, Pak C, Griffin J P, Bronze M S, Schaberg D R. Effects of cytokines and endotoxin on the intracellular growth of bacteria. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2834–2840. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2834-2840.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim H-Y, Rikihisa Y. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies to the 44-kilodalton major outer membrane protein of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3278–3284. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3278-3284.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lebech A M, Hansen K, Pancholi P, Sloan L M, Magera J M, Persing D H. Immunoserologic evidence of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Danish patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:173–176. doi: 10.1080/003655498750003582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee E H, Rikihisa Y. Absence of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor expression but presence of IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-10 expression in human monocytes exposed to viable or killed Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4211–4219. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4211-4219.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee E H, Rikihisa Y. Anti-Ehrlichia chaffeensis antibody complexed with E. chaffeensis induces potent proinflammatory cytokine mRNA expression in human monocytes through sustained reduction of IκB-α and activation of NF-κB. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2890–2897. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2890-2897.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee E H, Rikihisa Y. Protein kinase A-mediated inhibition of gamma interferon-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Janus kinases and latent cytoplasmic transcription factors in human monocytes by Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2514–2520. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2514-2520.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J R, Koretzky G A. Production of reactive oxygen intermediates following CD40 ligation correlates with c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation and IL-6 secretion in murine B lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:4188–4197. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<4188::AID-IMMU4188>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lotric-Furlan S, Petrovec M, Avsic-Zupanc T, Nicholson W L, Sumner J W, Childs J E, Strle F. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Europe: clinical and laboratory findings for four patients from Slovenia. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:424–428. doi: 10.1086/514683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohashi N, Zhi N, Zhang Y, Rikihisa Y. Immunodominant major outer membrane proteins of Ehrlichia chaffeensis are encoded by a polymorphic multigene family. Infect Immun. 1998;66:132–139. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.132-139.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrovec M, Lotric-Furlan S, Avsic Zupanc T, Strle F, Brouqui P, Roux V, Dumler J S. Human disease in Europe caused by a granulocytic Ehrlichia species. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1556–1559. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1556-1559.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rikihisa Y, Zhi N, Wormser G P, Wen B, Horowitz H W, Hechemy K E. Ultrastructural and antigenic characterization of a granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent directly isolated and stably cultivated from a patient in New York State. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:210–213. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.1.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rikihisa Y, Zhang Y, Park J. Inhibition of infection of macrophages with Ehrlichia risticii by cytochalasins, monodansylcadaverine, and taxol. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5126–5132. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5126-5132.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt K N, Amstad P, Cerutti P, Baeuerle P A. The roles of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide as messengers in the activation of transcription factor NF-κB. Chem Biol. 1995;2:13–22. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tufano M A, Rossano F, Catalanotti P, Liguori G, Capasso C, Ceccarelli M T, Marinelli P. Immunobiological activities of Helicobacter pylori porins. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1392–1399. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1392-1399.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tufano M A, Rossano F, Catalanotti P, Liguori G, Marinelli A, Baroni A, Marinelli P. Properties of Yersinia enterocolitica porins: interference with biological functions of phagocytes, nitric oxide production and selective cytokine release. Inst Pasteur Res Microbiol. 1994;145:297–307. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(94)90185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker D H, Dumler J S. Emergence of the ehrlichioses as human health problems. Emerg Infect Dis. 1996;2:18–29. doi: 10.3201/eid0201.960102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wormser G, McKenna D, Aguero-Rosenfeld M, et al. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis—New York. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1995;44:593–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhi N, Ohashi N, Rikihisa Y. Multiple p44 genes encoding major outer membrane proteins are expressed in the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17828–17836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhi N, Ohashi N, Rikihisa Y, Horowitz H W, Wormser G P, Hechemy K. Cloning and expression of the 44-kilodalton major outer membrane protein gene of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent and application of the recombinant protein to serodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1666–1673. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1666-1673.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhi N, Rikihisa Y, Kim H-Y, Wormser G P, Horowitz H W. Comparison of major antigenic proteins of six strains of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent by Western immunoblot analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2606–2611. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2606-2611.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]