On June 2, 2022, a disgruntled patient entered St. Francis hospital in Tulsa with a pistol and a semi–automatic rifle. The gunman had previously had back surgery by a physician, Preston Phillips, MD, and, per reports, blamed him for his post–surgical pain and wanted revenge.1

He ultimately ended up murdering his intended target, Dr. Phillips, as well as another physician and two others who got in his way. Though Dr. Phillips’ story got more attention in the press and physician murders are more sensationalized, his story is unfortunately not unique; less than two weeks after the Tulsa shooting, a nurse, and a paramedic were stabbed and critically injured by a patient in a St. Louis hospital.2

Overall, there is not a lot of data on the murders of healthcare workers, but the Bureau of Labor statistics reported 64 on–the–job fatalities for healthcare workers in 2020.3 Non–fatal assaults, on the other hand, are far more prevalent, with close to half a million in 2020,4 and with healthcare accounting for nearly as many serious violent injuries as all other industries combined.5,6 The data are limited by the sheer lack of reporting on workplace violence. Even the American Medical Association (AMA) Taskforce on Workplace Violence acknowledges that “available data indicate that health care workers experience high rates of workplace violence [but] such events are widely underreported.”5–7 This is typically due to a lack of faith that reporting would lead to meaningful change, not having time to report, lack of a formal reporting system, and fear of retaliation.5,7 In this review, we discuss the scope and magnitude of workplace violence in healthcare, the subgroups most affected, how the COVID–19 pandemic has impacted rates of violence against healthcare workers, and strategies for reducing risk.

Workplace Violence by Subgroups

Patients are responsible for the majority of violence towards healthcare workers, thus trends in violence can be best understood by examining which patients pose the highest risk for violence. The risk of workplace violence is not distributed evenly across specialty. Data shows that those who work in the emergency department, in geriatrics, or in psychiatry are substantially more likely to experience violence.8 This may be partly explained by the fact that these patient populations are more likely to be intoxicated, exhibiting psychosis, delirious, or have dementia, which are known risk factors for violence.5,6,9–13

Beyond specialty, practice setting also impacts the risk of violence. Rates of workplace violence in hospitals are over double the risk of ambulatory care settings.4 Unsurprisingly, psychiatric workers have the highest incidence rate of non–fatal injuries at more than 10 times the rate of other hospitals.4,5 Long–term nursing and residential care facilities are also at increased rates of violence, about 75% higher than the rate of violence in the hospital.

Job position contributes to a worker’s vulnerability to violence. Nurses, who typically have more day–to–day interactions with patients,14,15 are far more susceptible to workplace violence than physicians.3,4 It is worth noting that position and specialty have an intersectional effect and nurses who work in nursing homes or psychiatric facilities experience 3.5 times as many violent incidents as registered nurses5 because of the additive effects of their position and their specialty. The cumulative burden of violence faced by psychiatric and nursing home nurses has contributed to a staggering shortfall of nurses in these areas.16,17 In Missouri, the Department of Mental Health reports that “35% of registered nurse positions are vacant, 57% of licensed practical nurses are vacant, [and] 32% of entry–level psychiatric tech positions are vacant” and are unable to be filled.17

Despite the overall elevated rates of violence in United States (U.S.),18 American healthcare workers experience comparable rates of violence as workers in other countries.19 Studies show that healthcare workers who were born and educated in another country, but currently practice in the U.S. are more susceptible to workplace violence.20 This is likely due to both xenophobic attitudes towards foreign physicians,21 as well as potential language barriers.20,21

The Impact of COVID–19

In the context of the ongoing Covid–19 pandemic, violence against healthcare workers has worsened; the baseline environment is tenser, ‘fuses’ are substantially shorter, and it is far easier for violence to materialize. A meta–analysis performed in 2019 found that 69% (95% CI 58% to 78%) of healthcare workers experience workplace violence,19 while a comparable meta–analysis performed in 2021 showed a sharp increase to 77% (95% CI 72% to 82%).19 These statistics have become such a concern that the AMA adopted a new health policy to address the astounding rise in violence towards physicians. In their resolution, the AMA acknowledged the increase in violence “including physical violence, intimidating actions of word or deed, and cyber–attacks, ...particularly those [violent incidents] which appear motivated simply by [the victim’s] identification as health care workers.”22 A study categorizing the increased violence towards healthcare workers during the pandemic found that the majority were related to disputes over masks, but in 22% of cases, the perpetrator intentionally coughed or spit on the healthcare worker while threatening to infect them.23

In the high–intensity setting of a hospital during the pandemic, increased violence compounds the burnout experienced by healthcare workers and contributes to healthcare’s increasing resignations. It is well–established that workplace violence, both verbal and physical, contribute to burnout and drive high turnover rates in medicine.24–28 In the face of violence and burnout, healthcare is experiencing an exodus of skilled healthcare employees. The number of physicians leaving medicine has quadrupled since 2019, increasing from 0.39% of physicians each year in 2019 to 1.3% of physicians in 2021,29 resulting in an additional 10,000 doctors per year are leaving medicine.30 Nurses have also been quitting in droves.31 Surveys and interviews overwhelmingly report that their decision was driven by the violence and burnout they’ve experience during the pandemic.32–34

Strategies to Protect Healthcare Workers

While violence towards healthcare workers is an evident problem, and one necessary to improve for workplace sustainability, there is wide disagreement on how to address the problem. Although the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has created sets of recommendations on how to limit violence towards healthcare workers, there is no specific enforceable standard.6 Without a national enforceable standard, the decision is left up to the states and at the time OSHA published their report, only 10 states had passed legislation requiring programs on workplace violence prevention.6 Concerningly, hospitals with these programs are seen to be the models to aspire to, rather than the standard.

Ultimately, there is no simple solution. An international report breaks the problem down into three phases: prevention measures to reduce violence, protection measures to handle violent incidents in the moment, and treatment measures to prevent the long–term consequences to healthcare workers.35 When examining how to address violence towards healthcare workers, interventions must include a mixture of these three things to target prevention, protection, and treatment.

Starting first with prevention, hospital prevention strategies look at ways to prevent violence altogether and encompass a wide–range of strategies including de–escalation training for staff, electronic medical record flags and risk assessments for previously violent patients, and appropriate staffing ratios. A qualitative study investigating effective de–escalation techniques found that the most effective de–escalators apply rules thoughtfully, actively demonstrate equality and break down social barriers with patients, demonstrate shared humanity (through humor or self–disclosure), and show authenticity.36 Studies have found that de–escalation training programs which teach healthcare workers these strategies to reduce tensions with patients are effective in preventing violence. The joint commission discusses several such programs, all of which focus on identifying the triggers and strategies for defusing tension.37 One such program, Safewards, focuses on how staff may impact the environment, as well as how they can identify and react to flashpoints, which may spark conflict with patients. This program, which has a wide array of resources online, includes interventions such as clear mutual expectations, bad news mitigation, mutual help meeting, and calming down methods. Data suggests that the benefits gained from de–escalation training extinguishes at about six months, underlining the need for continuous education.38

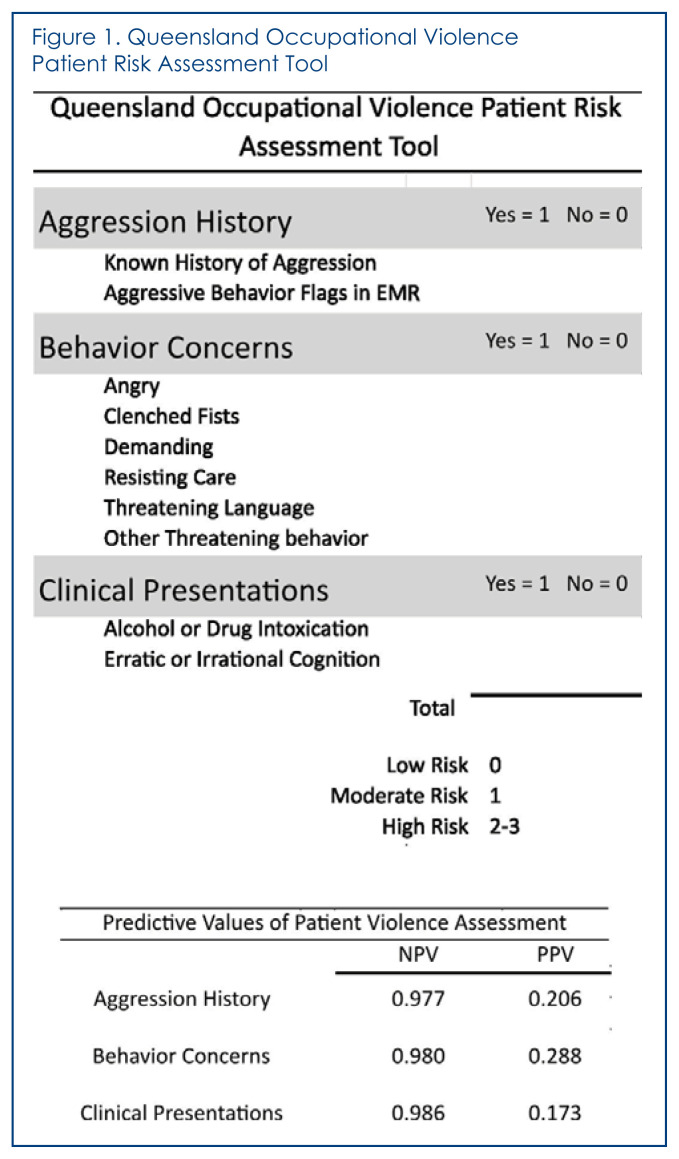

Studies of risk assessment in psychiatric wards found a significant reduction in patient aggression after implementing a risk assessment on violent patients.39,40 Several patient risk assessments tools exist, ranging in length from three to sixteen metrics.41–44 The most effective assessments, like the Queensland Occupational Violence Patient Risk Assessment Tool, are quick, reliable, and allow healthcare workers to effectively evaluate potential risk (Figure 1). Finally, appropriate patient ratios are linked to a decreased risk of violence.5 Providers who worked evening shifts, where patient ratios are less favorable, were up to 5.5 times more likely to be assaulted by patients;45,46 though more investigation is needed to determine the size of effect. There has been substantial efforts by nursing organizations to pass legally mandated patient ratios, but so far only two states (California and Massachusetts) have laws codifying safe nurse to patient ratios or standards.47 Nursing organizations have proposed fixed nursing ratios, ranging from 1:1 in the operating room and trauma bay to 1:6 in a well–baby nursery.48 The ratios suggested for the ED and psychiatric units, areas at high risk for violence, were 1:3 and 1:4 respectively.48

Figure 1.

The Queensland Occupational Violence Patient Risk Assessment Tool (QOVPRAO, pronounced kvow-pro) provides a quick and effective method for evaluating patient’s potential for violence in the hospital without relying on a patient’s cooperation or putting the provider at any unknown risk in simply asking questions. It looks a history of aggression (as either noted in their chart or legal history), behavioral cues of the patient, and clinical presentation to assist providers in evaluating risk and provides a validated mechanism for quantifying risk during notes (low, moderate, high). Most importantly, each metric has a high negative predictive value (97.7–98.7), meaning that a patient with a score of zero is highly unlikely to pose a threat to healthcare providers. This figure, as well as the positive and negative predictive values were adapted from Cabilan et al.41

Protection strategies focus on how to mitigate the risk in the moment and include interventions like panic buttons, metal detectors, and self–defense courses aimed at protecting staff. Unlike prevention strategies, which aim to prevent violence completely, protection strategies aim to minimize the severity of violence once it has erupted. After COVID–19 tripled the number of assaults of staff, a hospital in Branson, Missouri, issued panic buttons to staff. Reports from other hospitals using panic buttons indicate that it has decreased security response time.49 Similarly, studies have demonstrated that while metal detectors effectively remove weapons in the hospital,50,51 they do not decrease the number of assaults overall.50 Although these mitigation strategies seem to be common sense approaches, little data has been published on their efficacy, making it difficult to fully assess their role in decreasing violence against healthcare workers.

Finally, if violence actually reaches the healthcare worker, the hospital should have safe, easy, and confidential reporting combined with treatment for the victims. One of the primary difficulties in violence reduction is the lack of standardization in how data is collected. A 2022 study examined the compliance of California hospitals with workplace violence reporting regulations and found huge variation in reporting practices. Even within the same state, following the same legislation, some hospitals required reports to be made to security or management and some hospitals only reported incidents in physical harm to the employee.52 A system which requires healthcare workers to report to a manager or limits reporting only to incidents in which the victim was physically harmed exacerbates the problem, since fear of retribution and lack of confidentiality is a major driver of under–reporting.5 The reporting system needs to acknowledge that physical and verbal assaults impact healthcare workers equally 28 and need to be addressed equally. Given the potential for assaults to contribute to worsened mental health outcomes,53 it is important that employees have quick, affordable, and easy access to confidential care, if or when they need it.

Conclusion

Violence impacts all healthcare workers and unfortunately, the rise of incivility means that assaults on healthcare workers will continue to be a problem for the foreseeable future. There is the pragmatic argument that reducing violence in the hospitals brings ensuing benefits (increased patient metrics, decreased staff turnover, and increased productivity), which ultimately benefit the hospital and patients. There are also more compelling moral arguments to ensuring the safety of healthcare workers. Every worker is entitled to a safe workplace, no matter where they work, in what role, or in what specialty. Evidence shows that certain employees will be at increased risk due to non–modifiable factors (e.g., country of origin), so addressing violence in the healthcare setting is not just an issue of safety, but one of equity. Healthcare workers, who often make huge sacrifices for their professions, and often put their patients before themselves, should not be put at risk in their jobs, period. Making investments in staff training and infrastructure now is the most effective way to ensure staff safety and create a healthcare system that is more humane for both its employees and its patients.

Footnotes

Alison L. Huckenpahler, MD, PhD, and Jessica A. Gold, MD, MS, (above), are in the Department of Psychiatry, Washington University and the Department of Psychiatry, Barnes-Jewish Hospital. Both are in St. Louis, Missouri.

References

- 1.Maule I. Tulsa World. Jun 2, 2022. 2 doctors, a receptionist and a visitor were killed in the Tulsa shooting. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson J, Van de Riet E. Patient charged after nurse, paramedic stabbed at Missouri hospital. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fatal occupational injuries by occupation and event or exposure, all United States, 2020. Online: United States Department of Labor; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Number of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away from work by industry and selected natures of injury or illness, private industry 2020. United States Department of Labor; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Workplace Violence in Healthcare: Understanding the Challenge. United States Department of Labor: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preventing Violent Acts Against Health Care Providers. Online American Medical Association. :7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnetz JE, Hamblin L, Ager J, et al. Underreporting of Workplace Violence: Comparison of Self–Report and Actual Documentation of Hospital Incidents. Workplace Health Saf. 2015;63(5):200–210. doi: 10.1177/2165079915574684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnetz JE, Hamblin L, Ager J, et al. Application and implementation of the hazard risk matrix to identify hospital workplaces at risk for violence. Am J Ind Med. 2014;57(11):1276–1284. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas KS, Guy LS, Hart SD. Psychosis as a risk factor for violence to others: a meta–analysis. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(5):679–706. doi: 10.1037/a0016311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fazel S, Langstrom N, Hjern A, Grann M, Lichtenstein P. Schizophrenia, substance abuse, and violent crime. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2016–2023. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Dorn R, Volavka J, Johnson N. Mental disorder and violence: is there a relationship beyond substance use? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(3):487–503. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0356-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imlach Gunasekara F, Butler S, Cech T, et al. How do intoxicated patients impact staff in the emergency department? An exploratory study. N Z Med J. 2011;124(1336):14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tachibana M, Inada T, Ichida M, Ozaki N. Risk factors for inducing violence in patients with delirium. Brain Behav. 2021;11(8):e2276. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler R, Monsalve M, Thomas GW, et al. Estimating Time Physicians and Other Health Care Workers Spend with Patients in an Intensive Care Unit Using a Sensor Network. Am J Med. 2018;131(8):972 e979–972 e915. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollingsworth JC, Chisholm CD, Giles BK, Cordell WH, Nelson DR. How do physicians and nurses spend their time in the emergency department? Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31(1):87–91. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson D. Staffing shortages have U.S. nursing homes in crisis. U.S. News2022;Health News [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinberg T. Across Missouri mental health facilities, staffing shortages limit access to patient care. Missouri Independent2021;Health Care [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grinshteyn E, Hemenway D. Violent Death Rates: The US Compared with Other High–income OECD Countries, 2010. Am J Med. 2016;129(3):266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nowrouzi–Kia B, Chai E, Usuba K, Nowrouzi–Kia B, Casole J. Prevalence of Type II and Type III Workplace Violence against Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta–analysis. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2019;10(3):99–110. doi: 10.15171/ijoem.2019.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choiniere JA, MacDonnell J, Shamonda H. Walking the talk: insights into dynamics of race and gender for nurses. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2010;11(4):317–325. doi: 10.1177/1527154410396222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heponiemi T, Hietapakka L, Lehtoaro S, Aalto AM. Foreign–born physicians’ perceptions of discrimination and stress in Finland: a cross–sectional questionnaire study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):418. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3256-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Protecting Physicians and Other Healthcare Workers in Society. Online: American Medical Association; 2020. H–515.950. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiesman H, Marsh S, Konda S, et al. Workplace violence during the COVID–19 pandemic: March–October, 2020. United States Journal of Safety Research. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2022.07.004. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heponiemi T, Kouvonen A, Virtanen M, Vanska J, Elovainio M. The prospective effects of workplace violence on physicians’ job satisfaction and turnover intentions: the buffering effect of job control. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quine L. Workplace bullying in nurses. J Health Psychol. 2001;6(1):73–84. doi: 10.1177/135910530100600106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherman MF, Gershon RR, Samar SM, Pearson JM, Canton AN, Damsky MR. Safety factors predictive of job satisfaction and job retention among home healthcare aides. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(12):1430–1441. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31818a388e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamothe J, Guay S. Workplace violence and the meaning of work in healthcare workers: A phenomenological study. Work. 2017;56(2):185–197. doi: 10.3233/WOR-172486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schablon A, Kersten JF, Nienhaus A, et al. Risk of Burnout among Emergency Department Staff as a Result of Violence and Aggression from Patients and Their Relatives. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9) doi: 10.3390/ijerph19094945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neprash HT, Chernew ME. Physician Practice Interruptions in the Treatment of Medicare Patients During the COVID–19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2021;326(13):1325–1328. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.16324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young A, Chaudhry HJ, Pei X, Arnhart K, Dugan M, Simons KB. FSMB Census of Licensed Physicians in the United States, 2020. Journal of Medical Regulation. 2021;107(2):57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mensik H. Third of nurses plan to quit their jobs by end of 2022, survey shows. Healthcare Dive. 2022 March 16; 2022: Dive Brief. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galanis P, Vraka I, Fragkou D, Bilali A, Kaitelidou D. Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID–19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta–analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(8):3286–3302. doi: 10.1111/jan.14839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan D, Sullivan V, Weatherspoon D, Frazer C. Comparison of Nurse Burnout, Before and During the COVID–19 Pandemic. Nurs Clin North Am. 2022;57(1):79–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2021.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hear Us Out Campaign Reports Nurses’ COVID–19 Reality [press release] Online: American Association of Critical–Care Nurses. 2021 Sep 21; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiskow C. Guidelines on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. Geneva: ILO, WHO, ICN, PSI; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price O, Baker J, Bee P, et al. Patient perspectives on barriers and enablers to the use and effectiveness of de–escalation techniques for the management of violence and aggression in mental health settings. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(3):614–625. doi: 10.1111/jan.13488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De–escalation in health care. Quick Safety. 2019;47:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gillespie GL, Farra SL, Gates DM. A workplace violence educational program: a repeated measures study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2014;14(5):468–472. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaynes BN, Brown CL, Lux LJ, et al. Preventing and De–escalating Aggressive Behavior Among Adult Psychiatric Patients: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(8):819–831. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaynes BN, Brown C, Lux LJ, et al. Strategies to De–escalate Aggressive Behavior in Psychiatric Patients. Rockville (MD): 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cabilan CJ, McRae J, Learmont B, et al. Validity and reliability of the novel three–item occupational violence patient risk assessment tool. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(4):1176–1185. doi: 10.1111/jan.15166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luck L, Jackson D, Usher K. STAMP: components of observable behaviour that indicate potential for patient violence in emergency departments. J Adv Nurs. 2007;59(1):11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chapman R, Perry L, Styles I, Combs S. Predicting patient aggression against nurses in all hospital areas. Br J Nurs. 2009;18(8):476, 478–483. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2009.18.8.41810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barzman DH, Brackenbury L, Sonnier L, et al. Brief Rating of Aggression by Children and Adolescents (BRACHA): development of a tool for assessing risk of inpatients’ aggressive behavior. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2011;39(2):170–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farrell GA, Shafiei T, Chan SP. Patient and visitor assault on nurses and midwives: an exploratory study of employer ‘protective’ factors. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2014;23(1):88–96. doi: 10.1111/inm.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun S, Gerberich SG, Ryan AD. The Relationship Between Shiftwork and Violence Against Nurses: A Case Control Study. Workplace Health Saf. 2017;65(12):603–611. doi: 10.1177/2165079917703409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Advocating for Safe Staffing [press release] Online: American Nurses Association; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 48.United NN, editor. RN Staffing Ratios: A Necessary Solution to the Patient Safety Crisis in U.S. Hospitals. Online: National Nurses United; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shivaram D. A Hospital Gives Its Staff Panic Buttons After Assaults by Patients Triple. STLPR. 2021 9/30/21. Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rankins RC, Hendey GW. Effect of a security system on violent incidents and hidden weapons in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(6):676–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Malka ST, Chisholm R, Doehring M, Chisholm C. Weapons Retrieved After the Implementation of Emergency Department Metal Detection. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(3):355–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Odes R, Chapman S, Ackerman S, Harrison R, Hong O. Differences in Hospitals’ Workplace Violence Incident Reporting Practices: A Mixed Methods Study. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2022;23(2):98–108. doi: 10.1177/15271544221088248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.d’Ettorre G, Pellicani V. Workplace Violence Toward Mental Healthcare Workers Employed in Psychiatric Wards. Saf Health Work. 2017;8(4):337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]