Abstract

Cancer is being considered as a serious threat to human health globally due to limited availability and efficacy of therapeutics. In addition, existing chemotherapeutic drugs possess a diverse range of toxic side effects. Therefore, more research is welcomed to investigate the chemo-preventive action of plant-based metabolites. Ampelopsin (dihydromyricetin) is one among the biologically active plant-based chemicals with promising anti-cancer actions. It modulates the expression of various cellular molecules that are involved in cancer progressions. For instance, ampelopsin enhances the expression of apoptosis inducing proteins. It regulates the expression of angiogenic and metastatic proteins to inhibit tumor growth. Expression of inflammatory markers has also been found to be suppressed by ampelopsin in cancer cells. The present review article describes various anti-tumor cellular targets of ampelopsin at a single podium which will help the researchers to understand mechanistic insight of this phytochemical.

Keywords: Ampelopsin, Anti-proliferation, Apoptotic, Cell cycle arrest, Angiogenesis inhibition, Anti-inflammation

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The incidence of cancer diseases is continually increasing worldwide to cause millions of deaths each year. Based on the latest estimates, the global cancer burden will considerably increase over the next decades, being expected to reveal a 47% rise by 2040 as compared to the year 2020 [1], [2], [3], [4]. Due to various shortcomings in the traditional therapeutic formulations, more and more researchers all over the world are working on identifying novel anticancer agents and developing new efficient modalities to manage this dreadful disease [5], [6], [7]. A great majority of the current clinically approved chemotherapeutic drugs was came from various natural sources, from microbes, terrestrial and marine plants [8], [9], [10], [11]. In fact, well-known medications such as vinblastine and vincristine, paclitaxel and podophyllotoxin were all discovered in plants [8]. Being inspired by this initial success, many research groups around the world are devoted to separation of novel structural leads from different plant species and testing them regarding potential anticancer activities [12], [13], [14], [15].

One of such promising compounds is ampelopsin, also termed dihydromyricetin, that was first isolated from the plant Ampelopsis meliaefolia Kudo already in 1940, and was later detected as a major bioactive ingredient in Ampelopsis grossedentata (Handel-Mazzetti) W. T. Wang [16]. Several preclinical studies have displayed the ability of ampelopsin to suppress the growth of breast [17], ovarian [18], prostate [19], lung [20], colon [21], liver [22], renal [23] and bladder cancer [24] as well as glioma [25], osteosarcoma [26] and leukemia cells [27] via modulating various cellular signaling pathways. Ampelopsin has been indeed shown to inhibit proliferation, induce apoptosis, suppress migration, invasion and metastasis in various types of tumoral cells [17], [18], [27], [28]. Moreover, treatment of malignant cells with ampelopsin was also demonstrated to confer overcoming resistance and potentiating the responses to standard anticancer drugs like erlotinib [29] or carboplatin [30], opening new avenues in cancer treatment. Therefore, in this review article the molecular mechanisms behind these promising effects are described in depth. In addition, modern nanotechnological opportunities are discussed for enhancing the bioavailability of ampelopsin and improving its anticancer potential in vivo conditions. It is expected that intensifying the studies of natural anticancer agents will ultimately get us a step closer to solving the riddle of successful cancer therapy. Table 1, Table 2 gives a bird eye view of various in vivo and in vitro antiproliferative actions of ampelopsin.

Table 1.

An overview of in vitro anticancer potential of Ampelopsin.

| Type Of Cancer | Cell Lines | Effects | Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukemia | HL60 and K562 | Induces Apoptosis | ↓AKT and NF-κB | [27] |

| Hepatoma | HepG2 | Induces Apoptosis | ↑ERK1/2 and P38 | [31] |

| Glioma | U251 and A172 | Induces Apoptosis | ↑JNK, G1 and S phase arrest | [32] |

| Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 | Induces Apoptosis | ↑ Bax/Bcl-2 | [17] |

| Pheochromocytoma | PC12 | Induces Apoptosis | ↑ERK and Akt | [33] |

| Human Lung Adenocarcinoma | A549 | Induces Apoptosis | ↓ c-Myc/Skp2 and HDAC1 | [34] |

| Cervical Cancer | HeLa | Induces Apoptosis | ↑ Bax/Bcl-2 | [35] |

| Renal Cell Carcinoma | 786-O cells. | Induces Apoptosis, inhibits cell viability and metastasis | ↓PI3K/AKT | [23] |

| Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231 | Induces Apoptosis | ↓TNF-α/NF-κB | [36] |

| Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 | Induces Apoptosis | ↓GRP78 and CHOP | [37] |

| colon cancer | HCT-116, HCT-8 and HT-29 | Induces Apoptosis | ↑AMPK/MAPK/XAF1 | [21] |

| Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 | Induces Autophagy | ↓Akt-mTOR | [38] |

| osteosarcoma | MG-63 cells | Induces Apoptosis | ↑p21(CIP1) and G0/G1 phase arrest | [26] |

| non-small cell lung cancer | H1975 and H1650 | Induces Apoptosis | ↑Nox2-Bim | [29] |

| Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231 | Induces Apoptosis | ↓AxL, TYRO3, and FYN | [39] |

| Breast Cancer | MCF-7 | Induces Apoptosis (with Resveratrol, ampelopsin A and balanocarpol) | ↓sphingosine kinase 1 | [40] |

| Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231 | Induces Apoptosis | ↓mTOR | [41] |

| Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231 | induces Apoptosis | G2/M arrest | [42] |

| human lung adenocarcinoma | SPC-A-1 cell | induces Apoptosis | promoted tubulin polymerization | [43] |

| human bladder carcinoma and murine sarcoma | EJ cells (human) and 180 cells (Murine) | Inhibited proliferation | cell cycle arrest | [24] |

| Prostate cancer | PC-3 and LNCaP | Inhibits migration, invasion and metastasis | ↓Bcl-2 | [19] |

| Melanoma | B16 | Inhibits metastasis | [44] | |

| ovarian cancer cell | A2780 cells | Proliferation, migration and invasion | inhibited EMT, ↓NF-κB/Snail pathway | [18] |

| Melanoma | B16 | Inhibits, migration, invasion, and metastasis | [45] |

Table 2.

In vivo anticancer action of Ampelopsin.

| Type of Cancer | subject model | Effects | Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glioma | U251 and A172 | Induces Apoptosis | ↑JNK, G1 and S phase arrest | [25] |

| Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231 | Induces Apoptosis | ↓mTOR | [41] |

| human bladder carcinoma and murine sarcoma | EJ cells (human) and 180 cells (Murine) | Inhibited proliferation | cell cycle arrest | [24] |

| Prostate cancer | PC-3 cells | Induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation, reduces prostate tumor angiogenesis | ↓ CXCR4 | [19] |

| Melanoma | B16 | Inhibits metastasis | [44] | |

| Melanoma | B16 | Inhibits, migration, invasion, and metastasis | [45] |

2. Chemistry of ampelopsin

The chemical name of ampelopsin is 3, 5, 7, 3′, 4′, 5′-hexahydroxyl-2, 3-dihydroflavonol (Fig. 1), initially isolated from traditional Chinese medicinal plants Ampelopsis grossedentata and Ampelopsis meliaefolia. It is a major bioactive constituent approximately 30–40% (w/w) of Ampelopsis grossedentata. It has also been reported in other plants/ plants-based foods such as Hovenia dulcis and Cedrus deodara/ grapes and red bayberry [46].

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of Ampelopsin.

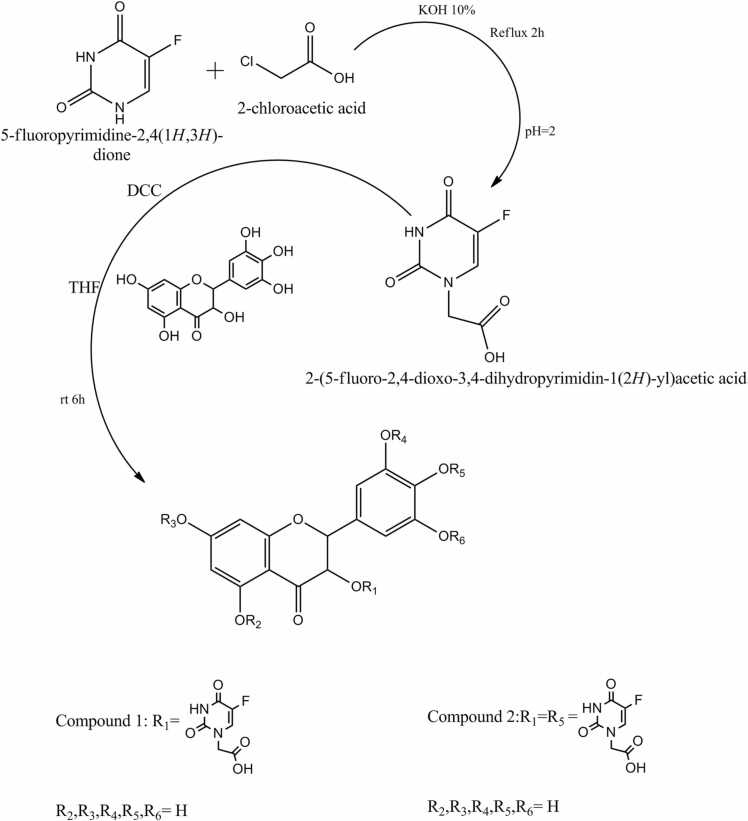

Zhou et al. investigated laboratory based synthetic methods of two novel 5-fluorouracil-substituted ampelopsin derivatives from 5-fluorouracil-1-carboxylic acid [47]. They established the structures of synthesized compounds by spectroscopic and elemental analysis methods (Fig. 2). Researchers found that new 5-FU-substituted ampelopsin derivatives were more effective anticancer agents against K562 and K562/ADR, cancer cell lines in comparison to native moiety.

Fig. 2.

: Schematic representations of two novel 5-fluorouracil-substituted ampelopsin derivatives.

3. Pharmacokinetics of ampelopsin

Pharmacokinetic investigations have indicated that the maximal plasma concentrations are 81.3 and 107 ng/ml of dextroisomer and racemate ampelopsin, respectively. This was after oral administration of 100 mg/kg [48]. The half-lives during degradation were recorded to be 288 and 367 min. This confirms weak absorption and rapid degradation nature of ampelopsin into the bloodstream [49]. According to Fan et al., unconverted ampelopsin is promptly distributed in the gastrointestinal system. It was also discovered that ampelopsin gets metabolized to three components by microflora through dihydroxylation and reduction [49].

Ampelopsin is also capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier. Xiang et al. investigated poor absorption nature of ampelopsin in Caco-2 cells, and lowering in the pH from 8.0 to 6.0 significantly improved its absorption [50]. Similarly, the pH of the solution has a significant impact on the intestinal stability of ampelopsin [51]. It was steady in a pH range of 1.0–5.0 in the stomach, whereas partial degradation occurred at a pH of 6.8 in the intestinal environment even though ampelopsin metabolites were only detectable in negligible concentrations in plasma, urine and feces revealed a total of eight metabolites [51].

Glucuronidation and sulfation metabolites have been observed in urinary samples, while dihydroxylation and reduction based intermediates were only found in feces [52]. Past research has shown that methylation pathways may be found in both urinary and fecal samples. Furthermore, some unchanged ampelopsin is also eliminated in the fecal samples [50]. Flavonoids' based intermediates are usually excreted through the biliary or urine systems [53]. The biliary system is in charge of excretion of both unchanged ampelopsin and its intermediates, while ampelopsin metabolism involves the urinary system. Significant enhancement of detection peak of ampelopsin levels in germ free rat vs. controlled models implicated the pharmacokinetic modulatory action of gut microbiota [53]. Due to its low water solubility, the bioavailability of ampelopsin is poor. Its absolute bioavailability in rats was found to be only less than 10% [54]. This shows a high need for improving the bioavailability to apply all beneficial pharmacological effects of ampelopsin in vivo conditions in the future.

4. Chemo-preventive action of ampelopsin

4.1. Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest

There are multiple anti-cancer properties reported for ampelopsin, including the potential to induce apoptosis (Fig. 3). In breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7), and cervical cancer (HeLa) cell line apoptotic potential of ampelopsin is imparted through mitochondrial dysfunction, loss of MMP, accumulation of reactive oxygen species, and upregulated Bax/Bcl-2 expression [17], [35]. It was shown that along with mitochondrial damage, ampelopsin also activates caspase-9,− 3 and PARP and downregulates AKT and NF-κB expressions [27]. Ampelopsin treatment reduces the phosphorylated levels of IκBα and NF-κB p65, both independent and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α-stimulated thus disrupting the TNF-α/NF-κB signaling axis as reported in MDA-MB-231/IR cells [36]. In lung adenocarcinoma SPC-A-1 cells, ampelopsin treatment leads to increased Ca2+ levels, mitochondrial nitric oxide production and decreased total ATPase activity and ΔΨm [55]. Anti-glioma role of ampelopsin was reported in human glioma (U251 and A172) cell lines (treated at 0, 25, 50, and 100 μM for 24 h) and human glioma xenograft models (50 and 100 mg/kg). Ampelopsin exerted its anti-glioma effects both through intrinsic and extrinsic pathways and upregulated c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK) expression [32]. In hepatoma HepG2 cells ampelopsin induces apoptosis through activating death receptor 4 and 5 mediated increase of Bax/Bcl-2 ratio. Moreover, minimal expression of JNK1/2 and activated p38, upon ampelopsin treatment were reported in HepG2 cells [31]. Similar report on ampelopsin induced apoptosis through upregulated TRAIL/DR5 and downstream activation of p38 signaling has been reported in Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive cells [56]. In renal cell carcinoma, ampelopsin treatment at 100 μM has been reported to induce apoptosis by negatively regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [57]. In lung cancer A549 cell line, ampelopsin has been reported to induce apoptotic cell death via modulating multiple c-Myc/S-phase kinase-associated protein 2/F-box and WD repeat-containing protein 7/histone deacetylase 2 signaling mechanisms [34]. Ampelopsin has also been reported to exert its apoptosis inducing potential through endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathway. In, breast cancer (MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7) cell lines, ampelopsin treatment induces ER-stress as evidenced by activated ER-stress related proteins such as including GRP78, p-PERK, p-elF2α, cleaved ATF6α and CHOP [37]. Ampelopsin induced ER-stress activates AMPK, and MAPKs pathway in colon cancer cells. RNAi mediated blocking of JNK or p-38/MAPK and not AMPK inhibits apoptosis suggesting ER-stress may be independent of AMPK induction and involve ROS mediated activation [58]. Therefore ROS production results in induction of ER stress followed by activation of MAPK signaling and apoptotic cell death via upregulation of XAF-1. Ampelopsin also showed anti-cancer potential against breast cancer (MDA-MB 231) cells via inhibition of increased mTOR activity. Possible explanation provided suggests inhibition of Akt, mTOR complexes 1/2 and decreased activation of p70-S6 kinase [41].

Fig. 3.

: Apoptotic mechanisms of action of ampelopsin in cancer. It initiates intrinsic (mitochondrial) as well extrinsic (Death receptor medicated) mechanisms of apoptosis induction.

Ampelopsin may impart its anti-cancer activities independent of apoptosis, such as by regulating cell cycle mechanism. Ampelopsin has been reported to arrest HL60 cells at the sub-G1 phase and K562 cells in S-phase. Differential regulation may be explained on the basis of ampelopsin regulation of cyclins and CDK’s [59]. Moreover, ampelopsin-treated U251 and A172 glioma cells were observed to be arrested in G1 and S phase initiated through ROS generation and autophagy [32]. It has also been suggested that ampelopsin may induce tubulin polymerization in lung adeno carcinoma SPC-A-1 cell line which may subsequently disrupt mitosis and arrest cells in S- phase both in SPC-A-1 and Hela cells [35], [43].

4.2. Anti-angiogenic and anti-metastatic mechanisms

Neo-vasculature is the development of new blood vessels from the preexistent vessels. All living cells including tumors need oxygen and nutrients to survive and proliferate. Angiogenesis is a critical step in proliferation and metastasis of cancer cells. One indirect way to prevent cancer is through halting this process and depriving the tumor of nutrients. In addition angiogenesis is important in wound healing, reproduction and pregnancy too [60], [61], [62], [63]. Deregulated angiogenesis causes a variety of pathological conditions such as malignancies, neurodegeneration, psoriasis and proliferative retinopathy [64], [65], [66]. Tumorigenesis relies on angiogenesis because all metabolic processes such as necessary nutrients, growth hormones, and molecular oxygen are circulated by angiogenesis process [67], [68], [69]. As a result, inhibiting angiogenesis could be a viable technique for treating cancer and other disorders linked to angiogenesis in humans[15], [70]. The primary hallmarks of angiogenesis are endothelial cell proliferation, metastasis and tubulogenesis by growth factors [71], [72], [73]. [74]. VEGFR2 plays a main role in signaling that promotes the migration and proliferation of endothelial cells by activating several downstream mediators, including signal STAT 3, ERK 1/2 and AKT (Fig. 4). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are extracellular basement membrane digesting enzymes that facilitates tumor invasion and migration from one site to other [75], [76], [77]. MMP-2 and MMP-9 are known to hold promising actions in the breakdown of laminin, type IV collagen and gelatin as well as other ECM and basement membrane components [78]. Therefore, MMPs are the key players in the deprivation of basement membrane and VEGFR2-mediated cascades that are used in cancer metastasis. Hence, inhibiting VEGFR2 and MMPs signal transduction may be used as an anti-angiogenesis therapy. Naturally isolated compounds such as paclitaxel, camptothecin, combretastatin and farnesiferol C showed angiogenesis regulating properties [79], [80], [81]. Ampelopsin showed antiproliferation potential against human hepatocellular carcinoma (Bel-7402) cell through downregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) [82]. Ni et al., 2012 reported that ampelopsin dose-dependently reduced the metastasis of prostate cancer (PC-3) cells via downregulation CXCR4 expression [19]. Zhang et al., 2014 reported that ampelopsin dose-dependently inhibits the migration of hepatoma cell lines (SK-Hep-1 and MHCC97L) via downregulation in the expression of MMP-9, p38, ERK1/2 and JNK [83]. Ampelopsin significantly upregulated E-cadherin and downregulated EMT via the NF-κB/Snail pathway in human ovarian cancer (A2780) cell line [18]. Han et al., 2017, reported that ampelopsin isolated from Hovenia dulcis reduced angiogenesis with no sign of toxicity in HUVECs via downregulation of VEGFR2 and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α) expression [60]. Huang et al., 2019 investigated that ampelopsin A and ampelopsin C isolated from Vitis thunbergii showed anti-metastatic and apoptosis-inducing against breast cancer (MDA-MB-231) cells via decreasing phosphorylation of AXL, Dtk (TYRO3), EphA2, EphA6, Fyn, Hck and SRMS [39]. Ampelopsin significantly inhibit PI3K/Akt signaling by inactivation of NF-κB and thereby reducing the MMP-9 expression leading to anti-metastasis of Leukemia Cells (HL60 and K562) [59].

Fig. 4.

: Anti-angiogenic and anti-metastatic action of ampelopsin via modulation of VEGF and MMPs expression.

4.3. Anti-inflammatory effect

Inflammation is a natural reaction of the body’s immunological cells and mediators such as cytokines (e.g. TNFα), chemokines (e.g. CCL2), reactive oxygen species (ROS) (e.g. O− 2), reactive nitrogen species (RNS) (e.g. NO3−) etc. released by these cells to protect against injury and infections by pathologic agents such as viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa etc. [84], [85]. However, uncontrolled or overproduction of inflammatory mediators leads to complication and propagation of various disease conditions including different cancers [86], [87], [88], [89], [90]. The anticancer activities of ampelopsin are widely supported by its anti-inflammatory (Fig. 5) and anti-oxidative activities. The supporting evidence originated from a number of in vitro studies by using cancer cell lines. In one such study Han et al. used ampelopsin to show decreased level of cell proliferation as well as increased level of apoptosis of HL60 and KL562 leukemia cell lines by down regulating AKT and NF-kB dependent signaling pathways respectively [59]. In another study Liu et al. showed that ampelopsin attenuated TNFα-induced migration and invasion of osteosarcoma cells. The mechanism relates to the ampelopsin dependent suppression of p38MAPK/MMP-2 signaling pathways [91]. In microglial cells, ampelopsin inhibited lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory signals via downregulation of NF-κB and JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathways [92]. Of note, NF-κB and STATs are recognized as proinflammatory transcription factors [93], [94], [95], [96]. Various levels of cross-talk exist between proinflammatory and prooxidative molecules [97]. Significantly, ampelopsin is now well accepted as a potential redox balance mediator by inhibiting LPS induced ROS generation in cancer cells [98]. Studies by Qi et al. also confirmed that ampelopsin reduces endotoxic inflammation via repressing ROS-mediated activation of PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathways [99]. Confirmatory in vivo studies are required to ascertain the anti-inflammatory activities of ampelopsin as one of the important mediators to attenuate various types of cancer complications.

Fig. 5.

: Anti-inflammatory mechanisms governed by ampelopsin. It mainly regulates PI3K/Akt/NF-κB and STATs signaling to inhibit inflammation in tumor microenvironment.

4.4. Ampelopsin mediated regulation of microRNAs

Accumulating evidence revealed that human biological system contains ~98% non-coding genes and ~2% coding genes [100], [101], [102]. Due to the abundance of non-coding genes, scientists are trying to investigate the biological, molecular, and cellular roles in human physiology. Several studies have shown that microRNAs (miRNAs), a highly conserved member of non-coding genes, are 20–23 nucleotides in size and are closely associated with cancer development [103], [104]. miRNAs play a significant role in apoptosis, cell cycle regulation, cell proliferation, and metastasis of various cancer cells and thus facilitate cancer pathogenesis such as esophageal cancer [105], cholangiocarcinoma. (CCA) [106], [107]. Due to their widespread role in regulating cancer phenotypes, miRNAs can be utilized in cancer therapy. However, the literature suggests that miRNA’s efficacy can be enhanced by incorporating bioactive compound molecules [106], [107].

For example, Lei Chen et al. [107] showed anti-tumor effects of ampelopsin in two human CCA cell lines, HCCC9810 and TFK-1. The authors showed that the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of 150 μM of ampelopsin inhibited the HCCC9810 and TFK-1 cells proliferation by 60%, cell migration by 60% and invasion by 80% compared to control CCA cells [107]. In contrast, the apoptosis rate was increased four times compared to control CCA cells. At molecular levels, treated HCCC9810 and TFK-1 with 150 μM of ampelopsin significantly enhanced the protein levels of cleaved caspase-3 and Bad as well as inhibited the protein levels of Bcl-2 and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP9) and Vimentin compared to the endogenous level in the control cells [107], suggesting the role of ampelopsin in cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion in CCA. Mechanistically, ampelopsin possesses anti-cancer effects in CCA through negatively regulating the well-known miR-21. miR-21 acts as an oncogene in CCA, and their oncogenic property gets abrogated by incorporating ampelopsin in a dose-dependent manner through the miR-21/phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN)/protein kinase B (Akt) pathway [107]. Interestingly, HCCC9810 and TFK-1 cells treated with ampelopsin promoted the protein level of PTEN and inhibited the phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt). However, reverse effects were demonstrated in the protein level of PTEN and p-Akt in cells with overexpressed miR-21 levels [107].

Moreover, studies showed that ampelopsin not only acts through oncogenic miRNA but also through negatively targeting tumor suppressor miR-455–3p in CCA cells [106]. Interestingly, miR-455–3p executes its function by negatively regulating zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) expression in CCA cells RBE and TFK-1. Furthermore, inhibition of miR-455–3p expression abolished the tumor-suppressing property of ampelopsin on cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in RBE and TFK-1 cells via PI3K/Akt mechanisms [106]. Mechanistically, the inhibitory effect of ampelopsin was abrogated by the downregulation of miR-455–3p and hence increased the protein expression levels of mesenchymal marker ZEB1 and Vimentin and suppressed the protein expression levels of mesenchymal marker E-Cadherin [106].

Overall, ampelopsin exerts great anti-tumorigenic effects on cell proliferation and metastasis through regulating the miR-21/PTEN/Akt pathway and miR-455–3p/ZEB1/PI3K/Akt pathway (Fig. 6) in CCA, which provides an alternative option for the future treatment of cancer.

Fig. 6.

: Ampelopsin incorporation into the cancer cells attenuates the oncogenic effect of miR-21 and tumor-suppressive effect of miR-455–3p through PTEN and PI3K pathway, which results in the activation of protein kinase B (p-Akt), which leads to the sequestration of mesenchymal markers and anti-apoptotic genes and enrichment of epithelial markers and pro-apoptotic genes.

5. Synergistic applications of ampelopsin

Phytochemicals such as flavonoids are known to possess anti-tumor effect with lower side effects in comparison to chemotherapeutics [14], [108]. Various synergistic chemo-preventive techniques with greater sensitivity in combination with known chemotherapeutic medications have attracted a lot of interest in recent years [109], [110], [111], [112]. Ampelopsin has been well demonstrated to exhibit potent cancer chemopreventive efficiency through regulation of different mechanisms [36] and also manifest hypoglycemic, antioxidant, antiviral and hepato-protective activities [35]. Furthermore, research suggests that ampelopsin improves the efficacy of some medications that could be used in chemoprevention and anticancer therapy. The drug was demonstrated to have a synergistic effect with irinotecan (CPT-11) or gemcitabine (GM), in an AOM/DSS-induced colitis-associated colon cancer model and a Min (Apc Min/+) mouse model, suggesting that a sufficient dose of ampelopsin could operate as a co-adjuvant to CPT-11 chemotherapy [113]. Furthermore, studies have also revealed that a combination of ampelopsin with ERK, JNK inhibitors and the reactive oxygen species scavenger, NAC resulted in reversal of ampelopsin-induced ERK and JNK activation and also sensitized the anti-tumorigenic effect of ampelopsin on Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells, thus prove to be an effective strategy for preventing NSCLC proliferation [114]. Due to possibility of tumors acquiring chemotherapeutic drug resistance cancer management sometimes becomes more challenging.

As a result, combination therapeutic techniques have emerged as a preferable option because they not only minimize the amount of chemotherapy necessary, i.e. for improving chemo-sensitivity, but they also amplify the anticancer effect of regular medications [109], [115], [116], [117]. Likewise, combinational effects of ampelopsin with oxaliplatin (OXA) have been found to increase OXA-induced apoptosis and reduced 5(6)-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein accumulation in OXA-resistant colorectal cancer (CRC HCT116/L-OHP) cells, thus indicating inhibition of multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2) mediated MDR, enhancement of chemo sensitivity and increasing anticancer activity induced by oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer cells [118]. Moreover, ampelopsin has also been found to potentiate retinoic acid mediated differentiation therapy for leukemia patients. It was observed that ampelopsin sensitized the APL (NB4) cells to ATRA-induced cell growth inhibition, CD11b expression, NBT reduction and myeloid regulator expression, thus posing possibility to explore ampelopsin and retinoic acid therapy [119]. Additionally, this natural flavonoid compound, in synergism with an improved platinum-containing drug, In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients, nedaplatin (NDP) has also been demonstrated to improve tumor susceptibility to chemotherapeutics and to prevent significant hepatocyte damage as well as drug resistance. The combination of ampelopsin and nedaplatin was shown to activate the p53/Bcl-2 signaling pathway, resulting in mitochondrial malfunction, cell death, and growth inhibition in HCC cells [120].

6. Safety studies

Before introducing clinical trials, safety issues must be carefully controlled for any new promising pharmaceutical agents. To date, only few toxicity studies have been performed with ampelopsin, showing that this natural compound did not induce any acute toxicity or significant side effects in mice at doses ranging from 150 mg/kg to 1.5 g/kg body weight [121]. Although this work clearly indicates that ampelopsin possesses very low toxicity, more studies are needed to establish safety limits and determine the values of no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL) for this attractive compound. Furthermore, a very recent study confirmed the safety of ampelopsin-containing cationic nanocapsules for topical application; however, these tests were performed with cell lines and not in animal models [122]. Therefore, further studies on the safety of ampelopsin are definitely needed.

7. Conclusion

In this review article, diverse anticancer effects of the flavanonol ampelopsin are described, focusing on its anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, proapoptotic, antiangiogenic and antimetastatic activities. The knowledge presented in this paper may be important for further unraveling the molecular pathways regulated by this biomolecule, but could also help to modify the structure of ampelopsin for enhancing its activities. In the future, further toxicity studies should be performed to ensure the safe application of this attractive phytochemical. Nanotechnology based methods could also be opted to decrease required doses of ampelopsin as well to enhance targeted delivery in cancer microenvironment.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Handling Editor: Lawrence Lash

References

- 1.Kashyap D., Tuli H.S., Yerer M.B., Sharma A., Sak K., Srivastava S., Pandey A., Garg V.K., Sethi G., Bishayee A. Natural product-based nanoformulations for cancer therapy: Opportunities and challenges. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021;69:5–23. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kashyap D., Garg V.K., Tuli H.S., Yerer M.B., Sak K., Sharma A.K., Kumar M., Aggarwal V., Sandhu S.S. Fisetin and quercetin: promising flavonoids with chemopreventive potential. Biomolecules. 2019;9:174. doi: 10.3390/biom9050174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrasco-Esteban E., Domínguez-Rullán J.A., Barrionuevo-Castillo P., Pelari-Mici L., Leaman O., Sastre-Gallego S., López-Campos F. Current role of nanoparticles in the treatment of lung cancer. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2021;7:140. doi: 10.18053/jctres.07.202102.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kashyap D., Garg V.K., Goel N. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Pathways Of Apoptosis: Role In Cancer Development And Prognosis. First ed. Elsevier Inc,; 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Z., Xu Y., Bi Y., Zhang N., Wang H., Xing T., Bai S., Shen Z., Naz F., Zhang Z., Yin L., Shi M., Wang L., Wang L., Wang S., Xu L., Su X., Wu S., Yu C. Immune escape mechanisms and immunotherapy of urothelial bladder cancer. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2021;7:485. doi: 10.18053/jctres.07.202104.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luna J., Sotoca A., Fernández P., Miralles C., Rodríguez A. Recent advances in early stage lung cancer. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2021;7:163. doi: 10.18053/jctres.07.202102.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furukawa F. Effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors on cancer patients with preexisting autoimmune disease. Trends Immunother. 2021;5:5–6. doi: 10.24294/ti.v5.i1.1250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demain A.L., Vaishnav P. Natural products for cancer chemotherapy. Microb. Biotechnol. 2011;4:687–699. doi: 10.1111/J.1751-7915.2010.00221.X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu C., Ho P.C.L., Wong F.C., Sethi G., Wang L.Z., Goh B.C. Garcinol: current status of its anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer effects. Cancer Lett. 2015;362:8–14. doi: 10.1016/J.CANLET.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel S.M., Nagulapalli Venkata K.C., Bhattacharyya P., Sethi G., Bishayee A. Potential of neem (Azadirachta indica L.) for prevention and treatment of oncologic diseases. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2016;40–41:100–115. doi: 10.1016/J.SEMCANCER.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung Y.Y., Ko J.H., Um J.Y., Sethi G., Ahn K.S. A novel role of bergamottin in attenuating cancer associated cachexia by diverse molecular mechanisms. Cancers. 2021;13:1–16. doi: 10.3390/cancers13061347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirtonia A., Gala K., Fernandes S.G., Pandya G., Pandey A.K., Sethi G., Khattar E., Garg M. Repurposing of drugs: an attractive pharmacological strategy for cancer therapeutics. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021;68:258–278. doi: 10.1016/J.SEMCANCER.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ong S.K.L., Shanmugam M.K., Fan L., Fraser S.E., Arfuso F., Ahn K.S., Sethi G., Bishayee A. Focus on formononetin: anticancer potential and molecular targets. Cancers. 2019;11:611. doi: 10.3390/cancers11050611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tuli H.S., Mistry H., Kaur G., Aggarwal D., Garg V.K., Mittal S., Yerer M.B., Sak K., Khan M.A. Gallic acid: a dietary polyphenol that exhibits anti-neoplastic activities by modulating multiple oncogenic targets. Anticancer. Agents Med. Chem. 2021;22:499–514. doi: 10.2174/1871520621666211119085834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuli H.S., Sak K., Gupta D.S., Kaur G., Aggarwal D., Parashar N.C., Choudhary R., Yerer M.B., Kaur J., Kumar M., Garg V.K., Sethi G. Anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties of birch bark-derived betulin: Recent developments. Plants. 2021;10:2663. doi: 10.3390/plants10122663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kou X., Chen N. Pharmacological potential of ampelopsin in Rattan tea. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness. 2012;1:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2012.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y., Zhou Y., Wang M., Lin X., Zhang Y., Laurent I., Zhong Y., Li J. Ampelopsin inhibits breast cancer cell growth through mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2021;44:1738–1745. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b21-00470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu T., Liu P., Ding F., Yu N., Li S., Wang S., Zhang X., Sun X., Chen Y., Wang F., Zhao Y., Li B. Ampelopsin reduces the migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells via inhibition of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Oncol. Rep. 2015;33:861–867. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ni F., Gong Y., Li L., Abdolmaleky H.M., Zhou J.R. Flavonoid ampelopsin inhibits the growth and metastasis of prostate cancer in vitro and in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu L., Zhang B., Luo J., Dong S., Zang K., Wu Y. Ampelopsin-sodium induces apoptosis in human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines by promoting tubulin polymerization in vitro. Oncol. Lett. 2019;18:189–196. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bin Park G., Jeong J.Y., Kim D. Ampelopsin-induced reactive oxygen species enhance the apoptosis of colon cancer cells by activating endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated AMPK/MAPK/XAF1 signaling. Oncol. Lett. 2017;14:7947–7956. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi S., Kou X., Lv J., Qi Z., Yan L. Ampelopsin induces apoptosis in HepG2 human hepatoma cell line through extrinsic and intrinsic pathways: Involvement of P38 and ERK. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015;40:847–854. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2015.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Z., Jiang Y., Liu Z., Li Q., Gao T., Zhang S. Ampelopsin inhibits cell viability and metastasis in renal cell carcinoma by negatively regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Evid. -Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/4650566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang B., Dong S., Cen X., Wang X., Liu X., Zhang H., Zhao X., Wu Y. Ampelopsin sodium exhibits antitumor effects against bladder carcinoma in orthotopic xenograft models. Anticancer. Drugs. 2012;23:590–596. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32835019f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo Z., Guozhang H., Wang H., Li Z., Liu N. Ampelopsin inhibits human glioma through inducing apoptosis and autophagy dependent on ROS generation and JNK pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019;116 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu M., Huang W., Bao N., Zhou G., Zhao J. The flavonoid ampelopsin inhibited cell growth and induced apoptosis and G0/G1 arrest in human osteosarcoma MG-63 cells in vitro. Pharmazie. 2015;70:388–393. doi: 10.1691/ph.2015.4871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han J.M., Kim H.L., Jung H.J. Ampelopsin inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in hl60 and k562 leukemia cells by downregulating akt and nf-κb signaling pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:4265. doi: 10.3390/ijms22084265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tieng F.Y.F., Latifah S.Y., Md Hashim N.F., Khaza’ai H., Ahmat N., Gopalsamy B., Wibowo A. Ampelopsin E reduces the invasiveness of the triple negative breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-231. Molecules. 2019;24:2619. doi: 10.3390/molecules24142619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong S.W., Park N.S., Noh M.H., Shim J.A., Ahn B.N., Kim Y.S., Kim D., Lee H.K., Hur D.Y. Combination treatment with erlotinib and ampelopsin overcomes erlotinib resistance in NSCLC cells via the Nox2-ROS-Bim pathway. Lung Cancer. 2017;106:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu L., ning Yang L., xi Wang X., li Song C., Qin H., jie Wu Y. Synergistic cytotoxicity of ampelopsin sodium and carboplatin in human non-small cell lung cancer cell line SPC-A1 by G1 cell cycle arrested. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2017;23:125–131. doi: 10.1007/s11655-016-2591-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qi S., Kou X., Lv J., Qi Z., Yan L. Ampelopsin induces apoptosis in HepG2 human hepatoma cell line through extrinsic and intrinsic pathways: Involvement of P38 and ERK. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015;40:847–854. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2015.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo Z., Guozhang H., Wang H., Li Z., Liu N. Ampelopsin inhibits human glioma through inducing apoptosis and autophagy dependent on ROS generation and JNK pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019;116 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kou X., Shen K., An Y., Qi S., Dai W.X., Yin Z. Ampelopsin inhibits H₂O₂-induced apoptosis by ERK and Akt signaling pathways and up-regulation of heme oxygenase-1. Phytother. Res. 2012;26:988–994. doi: 10.1002/PTR.3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen X.M., Xie X.B., Zhao Q., Wang F., Bai Y., Yin J.Q., Jiang H., Xie X.L., Jia Q., Huang G. Ampelopsin induces apoptosis by regulating multiple c-Myc/S-phase kinase-associated protein 2/F-box and WD repeat-containing protein 7/histone deacetylase 2 pathways in human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015;11:105–112. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng P., Gui C., Huang J., Xia Y., Fang Y., Da G., Zhang X. Molecular mechanisms of ampelopsin from Ampelopsis megalophylla induces apoptosis in HeLa cells. Oncol. Lett. 2017;14:2691–2698. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Truong V.N.P., Nguyen Y.T.K., Cho S.K. Ampelopsin suppresses stem cell properties accompanied by attenuation of oxidative phosphorylation in chemo-and radio-resistant MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14 doi: 10.3390/ph14080794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou Y., Shu F., Liang X., Chang H., Shi L., Peng X., Zhu J., Mi M. Ampelopsin induces cell growth inhibition and apoptosis in breast cancer cells through ROS generation and endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou Y., Liang X., Chang H., Shu F., Wu Y., Zhang T., Fu Y., Zhang Q., Zhu J.D., Mi M. Ampelopsin-induced autophagy protects breast cancer cells from apoptosis through Akt-mTOR pathway via endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1279–1287. doi: 10.1111/cas.12494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang C., Huang Y.L., Wang C.C., Pan Y.L., Lai Y.H., Huang H.C. Ampelopsins A and C Induce Apoptosis and Metastasis through Downregulating AxL, TYRO3, and FYN Expressions in MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019;67:2818–2830. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim K.G., Gray A.I., Pyne S., Pyne N.J. Resveratrol dimers are novel sphingosine kinase 1 inhibitors and affect sphingosine kinase 1 expression and cancer cell growth and survival. Br. J. Pharm. 2012;166:1605–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01862.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hui C., Xiaoli P., Qian B., Yong Z., Xiaoping Y., Qianyong Z., Jundong Z., Mantian M. Ampelopsin suppresses breast carcinogenesis by inhibiting the mTOR signalling pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35 doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rahman N.A., Yazan L.S., Wibowo A., Ahmat N., Foo J.B., Tor Y.S., Yeap S.K., Razali Z.A., Ong Y.S., Fakurazi S. Induction of apoptosis and G2/M arrest by ampelopsin E from dryobalanops towards triple negative breast cancer cells, MDA-MB-231. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016;16 doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1328-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu L., Zhang B., Luo J., Dong S., Zang K., Wu Y. Ampelopsin-sodium induces apoptosis in human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines by promoting tubulin polymerization in vitro. Oncol. Lett. 2019;18:189–196. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.D.Y. Liu, H.Q. Zheng, G.Q. Luo, Effects of ampelopsin on invasion and metastasis of B16 mouse melanoma in vivo and in vitro, Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 28 (2003) 960–961. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15620188/ (Accessed March 20, 2022). [PubMed]

- 45.H.Q. Zheng, D.Y. Liu, Anti-invasive and anti-metastatic effect of ampelopsin on melanoma, Ai Zheng. 22 (2003) 363–367. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12703989/ (Accessed March 20, 2022). [PubMed]

- 46.Sacks D., Baxter B., Campbell B.C.V., Carpenter J.S., Cognard C., Dippel D., Eesa M., Fischer U., Hausegger K., Hirsch J.A., Shazam Hussain M., Jansen O., Jayaraman M.V., Khalessi A.A., Kluck B.W., Lavine S., Meyers P.M., Ramee S., Rüfenacht D.A., Schirmer C.M., Vorwerk D. Multisociety consensus quality improvement revised consensus statement for endovascular therapy of acute ischemic stroke. Int. J. Stroke. 2018;13:612–632. doi: 10.1177/1747493018778713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou W.M., He R.R., Ye J.T., Zhang N., Liu D.Y. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new 5-fluorouracil-substituted ampelopsin derivatives. Molecules. 2010;15:2114–2123. doi: 10.3390/molecules15042114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tong Q., Hou X., Fang J., Wang W., Xiong W., Liu X., Xie X., Shi C. Determination of dihydromyricetin in rat plasma by LC-MS/MS and its application to a pharmacokinetic study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015;114:455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fan L., Tong Q., Dong W., Yang G., Hou X., Xiong W., Shi C., Fang J., Wang W. Tissue distribution, excretion, and metabolic profile of dihydromyricetin, a flavonoid from vine Tea (Ampelopsis grossedentata) after oral administration in rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017;65:4597–4604. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiang D., Fan L., long Hou X., Xiong W., Yang Shi C., qing Wang W., guo Fang J. Uptake and transport mechanism of dihydromyricetin across human intestinal caco-2 cells. J. Food Sci. 2018;83:1941–1947. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiang D., Wang C.G., Wang W.Q., Shi C.Y., Xiong W., Wang M.D., Fang J.G. Gastrointestinal stability of dihydromyricetin, myricetin, and myricitrin: an in vitro investigation. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017;68:704–711. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2016.1276518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Y., Que S., Yang X., Wang B., Qiao L., Zhao Y. Isolation and identification of metabolites from dihydromyricetin. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2007;45:909–916. doi: 10.1002/mrc.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen J., Wang X., Xia T., Bi Y., Liu B., Fu J., Zhu R. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications of dihydromyricetin in liver disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021;142 doi: 10.1016/J.BIOPHA.2021.111927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu D., Mao Y., Ding L., Zeng X.A. Dihydromyricetin: a review on identification and quantification methods, biological activities, chemical stability, metabolism and approaches to enhance its bioavailability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019;91:586–597. doi: 10.1016/J.TIFS.2019.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jiang J.F., Zhai J., Liu Z.R.J., Chao L., Zhao Y.F., Wu Y.J., Cui M.X. Ampelopsin sodium induces mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in human lung adenocarcinoma SPC-A-1 cell line. Pharmazie. 2016;71:455–459. doi: 10.1691/ph.2016.6571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yun S.M., Kim Y.S., Kim K.H., Hur D.Y. Ampelopsin induces DR5-mediated apoptotic cell death in EBV-infected cells through the p38 pathway. Nutr. Cancer. 2020;72:489–494. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2019.1639778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao Z., Jiang Y., Liu Z., Li Q., Gao T., Zhang S. Ampelopsin inhibits cell viability and metastasis in renal cell carcinoma by negatively regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling Pathway. Evid. -Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/4650566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bin Park G., Jeong J.Y., Kim D. Ampelopsin-induced reactive oxygen species enhance the apoptosis of colon cancer cells by activating endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated AMPK/MAPK/XAF1 signaling. Oncol. Lett. 2017;14:7947–7956. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han J.M., Kim H.L., Jung H.J. Ampelopsin inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in hl60 and k562 leukemia cells by downregulating akt and nf-κb signaling pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22084265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Han J.M., Lim H.N., Jung H.J. Hovenia dulcis Thunb. and its active compound ampelopsin inhibit angiogenesis through suppression of VEGFR2 signaling and HIF-1α expression. Oncol. Rep. 2017;38:3430–3438. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.6021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Siveen K.S., Ahn K.S., Ong T.H., Shanmugam M.K., Li F., Yap W.N., Kumar A.P., Fong C.W., Tergaonkar V., Hui K.M., Sethi G. γ-tocotrienol inhibits angiogenesis-dependent growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma through abrogation of AKT/mTOR pathway in an orthotopic mouse model. Oncotarget. 2014;5:1897–1911. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee J.H., Kim C., Kim S.H., Sethi G., Ahn K.S. Farnesol inhibits tumor growth and enhances the anticancer effects of bortezomib in multiple myeloma xenograft mouse model through the modulation of STAT3 signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2015;360:280–293. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yihui Yang J.W., Ren Liwen, Yang Hong, Ge Binbin, Li Wan, Wang Yumin, Wang Hongquan, Du Guanhua, Tang Bo. Research progress on anti-angiogenesis drugs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2021;3 doi: 10.18063/CP.V3I2.319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morbidelli L., Terzuoli E., Donnini S. Use of nutraceuticals in angiogenesis-dependent disorders. Molecules. 2018;23 doi: 10.3390/molecules23102676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Risau W. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature. 1997;386:671–674. doi: 10.1038/386671A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tremolada G., Del Turco C., Lattanzio R., Maestroni S., Maestroni A., Bandello F., Zerbini G. The role of angiogenesis in the development of proliferative diabetic retinopathy: impact of intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/728325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lugano R., Ramachandran M., Dimberg A. Tumor angiogenesis: causes, consequences, challenges and opportunities. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020;77:1745–1770. doi: 10.1007/S00018-019-03351-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ma Z., Wang L.Z., Cheng J.T., Lam W.S.T., Ma X., Xiang X., Wong A.L.A., Goh B.C., Gong Q., Sethi G., Wang L. Targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1-mediated metastasis for cancer therapy. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021;34:1484–1497. doi: 10.1089/ARS.2019.7935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mirzaei S., Zarrabi A., Hashemi F., Zabolian A., Saleki H., Ranjbar A., Seyed Saleh S.H., Bagherian M., omid Sharifzadeh S., Hushmandi K., Liskova A., Kubatka P., Makvandi P., Tergaonkar V., Kumar A.P., Ashrafizadeh M., Sethi G. Regulation of nuclear factor-KappaB (NF-κB) signaling pathway by non-coding RNAs in cancer: inhibiting or promoting carcinogenesis? Cancer Lett. 2021;509:63–80. doi: 10.1016/J.CANLET.2021.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tuli H.S., Kashyap D., Sharma A.K., Sandhu S.S. Molecular aspects of melatonin (MLT)-mediated therapeutic effects. Life Sci. 2015;135:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kashyap D., Garg V.K., Sandberg E.N., Goel N., Bishayee A. Oncogenic and tumor suppressive components of the cell cycle in breast cancer progression and prognosis. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:1–28. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13040569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kashyap D., Tuli H.S., Sak K., Garg V.K., Goel N., Punia S. Role of reactive oxygen species in cancer progression. Curr. Pharm. Rep. 2019;5:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Teleanu R.I., Chircov C., Grumezescu A.M., Teleanu D.M. Tumor angiogenesis and anti-angiogenic strategies for cancer treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2019;9 doi: 10.3390/JCM9010084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Melincovici Carmen Stanca, Boşca Adina Bianca, Şuşman Sergiu, Mărginean Mariana, Mihu Carina, Istrate Mihnea, Moldovan Ioana Maria, Roman Alexandra Livia, Mihu Carmen Mihaela. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) - key factor in normal and pathological angiogenesis - PubMed. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2018:455–467. 〈https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30173249/〉 (accessed March 28, 2022) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gialeli C., Theocharis A.D., Karamanos N.K. Roles of matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression and their pharmacological targeting. FEBS J. 2011;278:16–27. doi: 10.1111/J.1742-4658.2010.07919.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ko J.H., Um J.Y., Lee S.G., Yang W.M., Sethi G., Ahn K.S. Conditioned media from adipocytes promote proliferation, migration, and invasion in melanoma and colorectal cancer cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234:18249–18261. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Monisha J., Roy N.K., Padmavathi G., Banik K., Bordoloi D., Khwairakpam A.D., Arfuso F., Chinnathambi A., Alahmadi T.A., Alharbi S.A., Sethi G., Kumar A.P., Kunnumakkara A.B. NGAL is downregulated in oral squamous cell carcinoma and leads to increased survival, proliferation, migration and chemoresistance. Cancers. 2018;10:228. doi: 10.3390/cancers10070228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lai W.-C., Zhou M., Shankavaram U., Peng G., Wahl L.M. Differential regulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced monocyte Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 and MMP-9 by p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Immunol. 2003;170:6244–6249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee J.H., Choi S., Lee Y., Lee H.J., Kim K.H., Ahn K.S., Bae H., Lee H.J., Lee E.O., Ahn K.S., Ryu S.Y., Lü J., Kim S.H. Herbal compound farnesiferol C exerts antiangiogenic and antitumor activity and targets multiple aspects of VEGFR1 (Flt1) or VEGFR2 (Flk1) signaling cascades. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010;9:389–399. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Han J.M., Kwon H.J., Jung H.J. Tricin, 4′,5,7-trihydroxy-3′,5′-dimethoxyflavone, exhibits potent antiangiogenic activity in vitro. Int. J. Oncol. 2016;49:1497–1504. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fan T.P., Yeh J.C., Leung K.W., Yue P.Y.K., Wong R.N.S. Angiogenesis: from plants to blood vessels. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2006;27:297–309. doi: 10.1016/J.TIPS.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.G. qin Luo, S. Zeng, D. yu Liu, Inhibitory effects of ampelopsin on angiogenesis, Zhong Yao Cai. 29 (2006) 146–150. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16617784/ (accessed March 28, 2022). [PubMed]

- 83.Zhang Q.Y., Li R., Zeng G.F., Liu B., Liu J., Shu Y., Liu Z.K., Qiu Z.D., Wang D.J., Miao H.L., Li M.Y., Zhu R.Z. Dihydromyricetin inhibits migration and invasion of hepatoma cells through regulation of MMP-9 expression. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10082–10093. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i29.10082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aggarwal V., Kashyap D., Sak K., Tuli H.S., Jain A., Chaudhary A., Garg V.K., Sethi G., Yerer M.B. Molecular mechanisms of action of tocotrienols in cancer: recent trends and advancements. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20030656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kashyap D., Sharma A., Garg V.K., Tuli H.S., Kumar G., Kumar M. Reactive oxygen species (ros): an activator of apoptosis and autophagy. Cancer, J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2016;3:256–264. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen L., Deng H., Cui H., Fang J., Zuo Z., Deng J., Li Y., Wang X., Zhao L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget. 2018;9:7204–7218. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Coussens L.M., Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morgan D., Garg M., Tergaonkar V., Tan S.Y., Sethi G. Pharmacological significance of the non-canonical NF-κB pathway in tumorigenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Rev. Cancer. 2020;1874 doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Arora L., Kumar A.P., Arfuso F., Chng W.J., Sethi G. The role of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and its targeted inhibition in hematological malignancies. Cancers. 2018;10:327. doi: 10.3390/cancers10090327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ong P.S., Wang L.Z., Dai X., Tseng S.H., Loo S.J., Sethi G. Judicious toggling of mTOR activity to combat insulin resistance and cancer: current evidence and perspectives. Front. Pharmacol. 2016;7:395. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu C., Zhao P., Yang Y., Xu X., Wang L., Li B. Ampelopsin suppresses TNF-α-induced migration and invasion of U2OS osteosarcoma cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016;13:4729–4736. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weng L., Zhang H., Li X., Zhan H., Chen F., Han L., Xu Y., Cao X. Ampelopsin attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response through the inhibition of the NF-κB and JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathways in microglia. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017;44:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim C., Lee S.G., Yang W.M., Arfuso F., Um J.Y., Kumar A.P., Bian J., Sethi G., Ahn K.S. Formononetin-induced oxidative stress abrogates the activation of STAT3/5 signaling axis and suppresses the tumor growth in multiple myeloma preclinical model. Cancer Lett. 2018;431:123–141. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shanmugam M.K., Ahn K.S., Hsu A., Woo C.C., Yuan Y., Tan K.H.B., Chinnathambi A., Alahmadi T.A., Alharbi S.A., Koh A.P.F., Arfuso F., Huang R.Y.J., Lim L.H.K., Sethi G., Kumar A.P. Thymoquinone inhibits bone metastasis of breast cancer cells through abrogation of the CXCR4 signaling axis. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:1294. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang J., Ahn K.S., Kim C., Shanmugam M.K., Siveen K.S., Arfuso F., Samym R.P., Deivasigamanim A., Lim L.H.K., Wang L., Goh B.C., Kumar A.P., Hui K.M., Sethi G. Nimbolide-Induced oxidative stress abrogates STAT3 signaling cascade and inhibits tumor growth in transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate model. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2016;24:575–589. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Garg M., Shanmugam M.K., Bhardwaj V., Goel A., Gupta R., Sharma A., Baligar P., Kumar A.P., Goh B.C., Wang L., Sethi G. The pleiotropic role of transcription factor STAT3 in oncogenesis and its targeting through natural products for cancer prevention and therapy. Med. Res. Rev. 2020;41:1291–1336. doi: 10.1002/MED.21761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Reuter S., Gupta S.C., Chaturvedi M.M., Aggarwal B.B. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;49:1603–1616. doi: 10.1016/J.FREERADBIOMED.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen L., Shi M., Lv C., Song Y., Wu Y., Liu S., Zheng Z., Lu X., Qin S. Dihydromyricetin acts as a potential redox balance mediator in cancer chemoprevention. Mediat. Inflamm. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/6692579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Qi S., Xin Y., Guo Y., Diao Y., Kou X., Luo L., Yin Z. Ampelopsin reduces endotoxic inflammation via repressing ROS-mediated activation of PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathways. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2012;12:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Khandelwal A., Bacolla A., Vasquez K.M., Jain A. Long non-coding RNA: a new paradigm for lung cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 2015;54:1235–1251. doi: 10.1002/mc.22362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sharma U., Barwal T.S., Acharya V., Singh K., Rana M.K., Singh S.K., Prakash H., Bishayee A., Jain A. Long non-coding RNAs as strategic molecules to augment the radiation therapy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:1–18. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.An X.J.Ting, Liu Jie, Yang Qian, Xiao Li. Anti-tumor role of microRNA-4782-3p in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2021;3 doi: 10.18063/CP.V3I1.294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Khandelwal A., Seam R.K., Gupta M., Rana M.K., Prakash H., Vasquez K.M., Jain A. Circulating microRNA-590-5p functions as a liquid biopsy marker in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:826–839. doi: 10.1111/cas.14199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Khandelwal A., Sharma U., Barwal T.S., Seam R.K., Gupta M., Rana M.K., Vasquez K.M., Jain A. Circulating miR-320a acts as a tumor suppressor and prognostic factor in non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.645475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Malhotra A., Sharma U., Puhan S., Chandra Bandari N., Kharb A., Arifa P.P., Thakur L., Prakash H., Vasquez K.M., Jain A. Stabilization of miRNAs in esophageal cancer contributes to radioresistance and limits efficacy of therapy. Biochimie. 2019;156:148–157. doi: 10.1016/J.BIOCHI.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Li X., Yang Z.S., Cai W.W., Deng Y., Chen L., Tan S.L. Dihydromyricetin inhibits tumor growth and epithelial-mesenchymal transition through regulating miR-455-3p in cholangiocarcinoma. J. Cancer. 2021;12:6058–6070. doi: 10.7150/jca.61311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chen L., Yang Z.S., Zhou Y.Z., Deng Y., Jiang P., Tan S.L. Dihydromyricetin inhibits cell proliferation, migration, invasion and promotes apoptosis via regulating mir-21 in human cholangiocarcinoma cells. J. Cancer. 2020;11:5689–5699. doi: 10.7150/jca.45970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yadav P., Jaswal V., Sharma A., Kashyap D., Tuli H.S., Garg V.K., Das S.K., Srinivas R. Celastrol as a pentacyclic triterpenoid with chemopreventive properties. Pharm. Pat. Anal. 2018;7:155–167. doi: 10.4155/ppa-2017-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tuli H.S., Kashyap D., Sharma A.K., Sandhu S.S. Molecular aspects of melatonin (MLT)-mediated therapeutic effects. Life Sci. 2015;135:147–157. doi: 10.1016/J.LFS.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Manu K.A., Shanmugam M.K., Ramachandran L., Li F., Siveen K.S., Chinnathambi A., Zayed M.E., Alharbi S.A., Arfuso F., Kumar A.P., Ahn K.S., Sethi G. Isorhamnetin augments the anti-tumor effect of capeciatbine through the negative regulation of NF-κB signaling cascade in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015;363:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Manu K.A., Shanmugam M.K., Li F., Chen L., Siveen K.S., Ahn K.S., Kumar A.P., Sethi G. Simvastatin sensitizes human gastric cancer xenograft in nude mice to capecitabine by suppressing nuclear factor-kappa B-regulated gene products. J. Mol. Med. 2014;92:267–276. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Srivani G., Peela S., Alam A., Nagaraju G.P. Gemcitabine for pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2021;S1 doi: 10.18063/CP.V3I3.323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhu X.H., Lang H.D., Wang X.L., Hui S.C., Zhou M., Kang C., Yi L., Mi M.T., Zhang Y. Synergy between dihydromyricetin intervention and irinotecan chemotherapy delays the progression of colon cancer in mouse models. Food Funct. 2019;10:2040–2049. doi: 10.1039/c8fo01756e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kao S.J., Lee W.J., Chang J.H., Chow J.M., Chung C.L., Hung W.Y., Chien M.H. Suppression of reactive oxygen species-mediated ERK and JNK activation sensitizes dihydromyricetin-induced mitochondrial apoptosis in human non-small cell lung cancer. Environ. Toxicol. 2017;32:1426–1438. doi: 10.1002/tox.22336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tuli H.S., Aggarwal V., Kaur J., Aggarwal D., Parashar G., Parashar N.C., Tuorkey M., Kaur G., Savla R., Sak K., Kumar M. Baicalein: A metabolite with promising antineoplastic activity. Life Sci. 2020;259 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lee J.H., Chiang S.Y., Nam D., Chung W.S., Lee J., Na Y.S., Sethi G., Ahn K.S. Capillarisin inhibits constitutive and inducible STAT3 activation through induction of SHP-1 and SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatases. Cancer Lett. 2014;345:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Manu K.A., Shanmugam M.K., Ramachandran L., Li F., Fong C.W., Kumar A.P., Tan P., Sethi G. First evidence that γ-tocotrienol inhibits the growth of human gastric cancer and chemosensitizes it to capecitabine in a xenograft mouse model through the modulation of NF-κB pathway. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:2220–2229. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang Z., Sun X., Feng Y., Liu X., Zhou L., Sui H., Ji Q., Qiukai E., Chen J., Wu L., Li Q. Dihydromyricetin reverses MRP2-mediated MDR and enhances anticancer activity induced by oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer cells. Anticancer. Drugs. 2016;28:281–288. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.hui He M., Zhang Q., Shu G., chun Lin J., Zhao L., xia Liang X., Yin L., Shi F., lin Fu H., xiang Yuan Z. Dihydromyricetin sensitizes human acute myeloid leukemia cells to retinoic acid-induced myeloid differentiation by activating STAT1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;495:1702–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jiang L., Zhang Q., Ren H., Ma S., Lu C.J., Liu B., Liu J., Liang J., Li M., Zhu R. Dihydromyricetin enhances the chemo-sensitivity of nedaplatin via regulation of the p53/Bcl-2 pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhang Q., Liu J., Liu B., Xia J., Chen N., Chen X., Cao Y., Zhang C., Lu C., Li M., Zhu R. Dihydromyricetin promotes hepatocellular carcinoma regression via a p53 activation-dependent mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4628. doi: 10.1038/srep04628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Dalcin A.J.F., Roggia I., Felin S., Vizzotto B.S., Mitjans M., Vinardell M.P., Schuch A.P., Ourique A.F., Gomes P. UVB photoprotective capacity of hydrogels containing dihydromyricetin nanocapsules to UV-induced DNA damage. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2021;197 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]