Abstract

Background:

Depressive episodes during pregnancy are widely investigated but it is still unknown whether pregnancy is a high-risk period compared to the pre-pregnancy period. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the incidence and recurrence of depressive episodes before, during, and after pregnancy.

Methods:

In the current population-based registry study, we calculated monthly incidence and recurrence of psychiatric inpatient admissions and outpatient psychiatric contact for depressive episodes. We identified a population consisting of all first childbirths in Denmark from 1999 through 2015 (N=392,287).

Results:

Incidence of inpatient admission during pregnancy was lower than before pregnancy. After childbirth, a significant increase in first-time and recurrent psychiatric inpatient admissions was observed, especially in the first months. In contrast, outpatient psychiatric treatment incidence and recurrence were increased both during pregnancy as well as in the postpartum period, as compared to pre-pregnancy.

Limitations:

Analyses were performed on depressive episodes representing the severe end of the spectrum, questioning generalizability to milder forms of depression treated outside psychiatric specialist treatment facilities.

Conclusion:

We found a different pattern of severe episodes of depression compared to moderate episodes before, during, and after pregnancy. In light of our findings and those of others, we suggest distinguishing between timing of onset in the classification of depression in the perinatal period: Depression with pregnancy onset OR with postpartum onset (instead of the current DSM classifier “with perinatal onset”), as well as severity of depression, which is important for both clinical and future research endeavors.

Keywords: pregnancy, postpartum, depression, incidence, recurrence, DSM-V

Introduction

The incidence and prevalence of depression are high in women both during pregnancy and in the postpartum period. A large meta-analysis found an overall pooled prevalence of 11.9% for the occurrence of a major depressive episode either during pregnancy or after delivery (Woody et al., 2017). The current classification system, the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), contains a specifier to indicate that a depressive episode has a peripartum onset, defined as onset of depression either during pregnancy or in the first four weeks postpartum.

Both the DSM committee and experts in the field have suggested that the failure of the current classifier to distinguish between depression with pregnancy onset and depression with postpartum onset may be problematic. The DSM committee stated that “the postpartum period is unique with respect to the degree of neuroendocrine alterations and psychosocial adjustments”, thereby indicating an important difference between pregnancy and the postpartum period (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This is supported by clinicians, who have argued that timing of onset matters, given that both diagnosis and treatment of depression differ between pregnancy and the postpartum period (Altemus et al., 2012; Putnam et al., 2017; Uher et al., 2014).

A small number of studies have investigated phenotypic differences between depression with pregnancy and postpartum onset (Altemus et al., 2012; Stowe et al., 2005). They found that women with onset of depression during pregnancy had much higher rates of prior episodes of major depression and that pregnancy onset was associated with a lack of social support, unplanned pregnancy, and a history of physical or sexual abuse. The symptom profile also differed, such that women with postpartum onset more often experienced distressing intrusive violent thoughts and other obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and more often had psychotic symptoms.

Some researchers have argued that postpartum depression might be considered a distinct disorder from major depressive disorder due to differences in symptom severity, hormone contributions, heritability, epigenetic mechanisms, and response to standard and novel treatment interventions (Batt et al., 2020; Di Florio and Meltzer-Brody, 2015; Jolley and Betrus, 2007). Clearly, more research is needed to support such a statement.

The current DSM specifier indicates peripartum depression has an onset either during pregnancy or in the first four weeks postpartum. There is currently little population-based epidemiological evidence on monthly incidence and prevalence patterns of perinatal depression supportive of this specification. In addition, no studies on depression included the preconception period for comparison to both pregnancy and the postpartum period. Accordingly, in this population-based register study, we investigated the monthly incidence and recurrence of moderate and severe depressive episodes before, during, and after pregnancy.

Materials & Methods

Study design and data sources

The current population-based registry study was conducted using a descriptive prospective study design based on information on the entire Danish population. We aimed to present both first-time and recurrent treatment rates of women treated for perinatal depressive episodes, combining records of treatment in secondary/tertiary health-care settings. To that end, two different Danish population registers were linked using the Civil Personal Registration (CPR) number, which is a personal identification number assigned to all residents in the country. Women were identified through the Civil Registration System, which was initiated in 1968 and contains updated personal information including vital status (dates of birth, migration, and death), citizenship, birth registration, and links to legal family members (Pedersen, 2011). In addition, the Psychiatric Central Research Register provided information on inpatient treatment (since 1969) and outpatient treatment (since 1995) (Mors et al., 2011).

Identification of women, births and perinatal depressive episodes

We identified a population consisting of all first childbirths in Denmark with a Danish-born mother within the years 1999 through 2015 (N=392,287). We restricted our study period to end in 2015 allowing for a one-year follow-up period of all childbirths. Only first births were included to avoid dependency related to health-seeking behavior and treatment strategy between pregnancies/births by the same woman. Women had to be at least 15 years of age on the day of childbirth, and reside in Denmark without having emigrated prior to giving birth.

Each individual pregnancy and first childbirth among the identified women were examined. For all births, we identified (1) a preconception period, defined as the 12 months preceding pregnancy, (2) a pregnancy period, defined as the period of time from nine months before to date of birth, and (3) a postpartum period, defined as the 12 months following the date of birth. We considered each month when looking at first-time and recurrent records, with each month being defined as 30 days.

Since 1994, all diagnosis in Denmark are recorded using the ICD-10 classification system. In Denmark, most depressions are treated by general practitioners (Musliner et al., 2019). If the depression is more severe, women are referred for psychiatric outpatient treatment, and the most severe depressive cases are treated at a psychiatric inpatient facility. As the aim of the current study was to focus on mild/moderate and severe episodes of depression, we included information on women in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Depressive episodes were identified with the ICD-10 codes F32.xx and F33.xx (“ICD-10-CM Code F32 - Major depressive disorder, single episode,” n.d.; “ICD-10-CM Code F33 - Major depressive disorder, recurrent,” n.d.).

Statistical analysis

Incidence and recurrence in both the inpatient and outpatient treatment setting was calculated for each month. The incidence provides information about how many new cases of treated depressive episodes during each month were recorded per treatment setting, while recurrence measures how many women with previous treatment needed recurrent treatment for depression in each month. Incidence was calculated counting the first-ever admission or outpatient contact and dividing this number by the total number of births. A treatment episode was considered first-ever if the woman had no previous records of treatment in the specific treatment setting. Recurrence rates were calculated each month counting all recurrent admissions and outpatient contacts (one contact per birth for each month) and dividing this by the total number of births.

Consider the following examples to illustrate definitions of incident and recurrent treatment as used in the study: Woman A experiences a first-ever depressive episode in the third month after giving birth to her first live-born child. She is then diagnosed and treated at an outpatient psychiatric treatment facility. She has never received inpatient or outpatient psychiatric treatment for a depressive episode before. Thus, she is recorded with her first-time outpatient treatment episode three months after childbirth and contributes to the calculated outpatient first-time incidence for this particular month. If she is subsequently admitted to an inpatient psychiatric hospital six months after birth, she is recorded with her first-time inpatient treatment episode six months after childbirth and contributes to the calculated first-time admission incidence for this particular month. Woman B has a long history of inpatient admissions and outpatient visits for depressive disorders before conception. During her pregnancy leading up to her first live-born child, she develops new symptoms of depression and is admitted in her sixth month of pregnancy at a tertiary psychiatric care facility. She therefore contributes to the calculated recurrence for this particular month. Woman B is discharged one month later, but again admitted for treatment of depression four months after childbirth. She again contributes to the calculated recurrence for this particular month. She does not contribute to any calculations of first-time incidence in this set-up.

Results

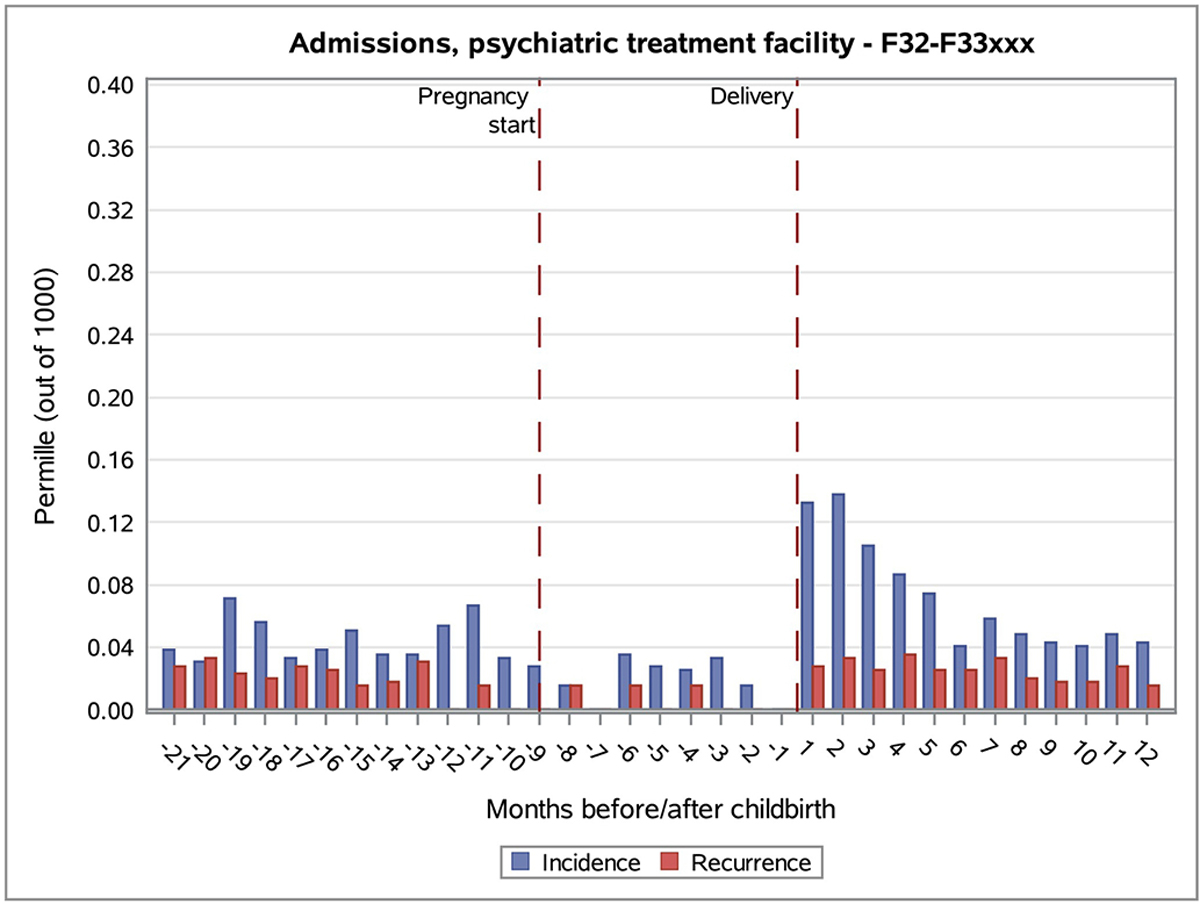

Psychiatric inpatient treatment

The first-time and recurrent number of depressive episodes treated at psychiatric inpatient facilities were highest during the 12 months after childbirth with a peak in incidence in the second month after childbirth (Figure 1). In contrast, the figure shows that during pregnancy both incidence and recurrence of psychiatric inpatient admission was lower than before pregnancy.

Figure 1.

Incidence and recurrence of inpatient psychiatric hospital treatment for depression before, during, and after first childbirth.

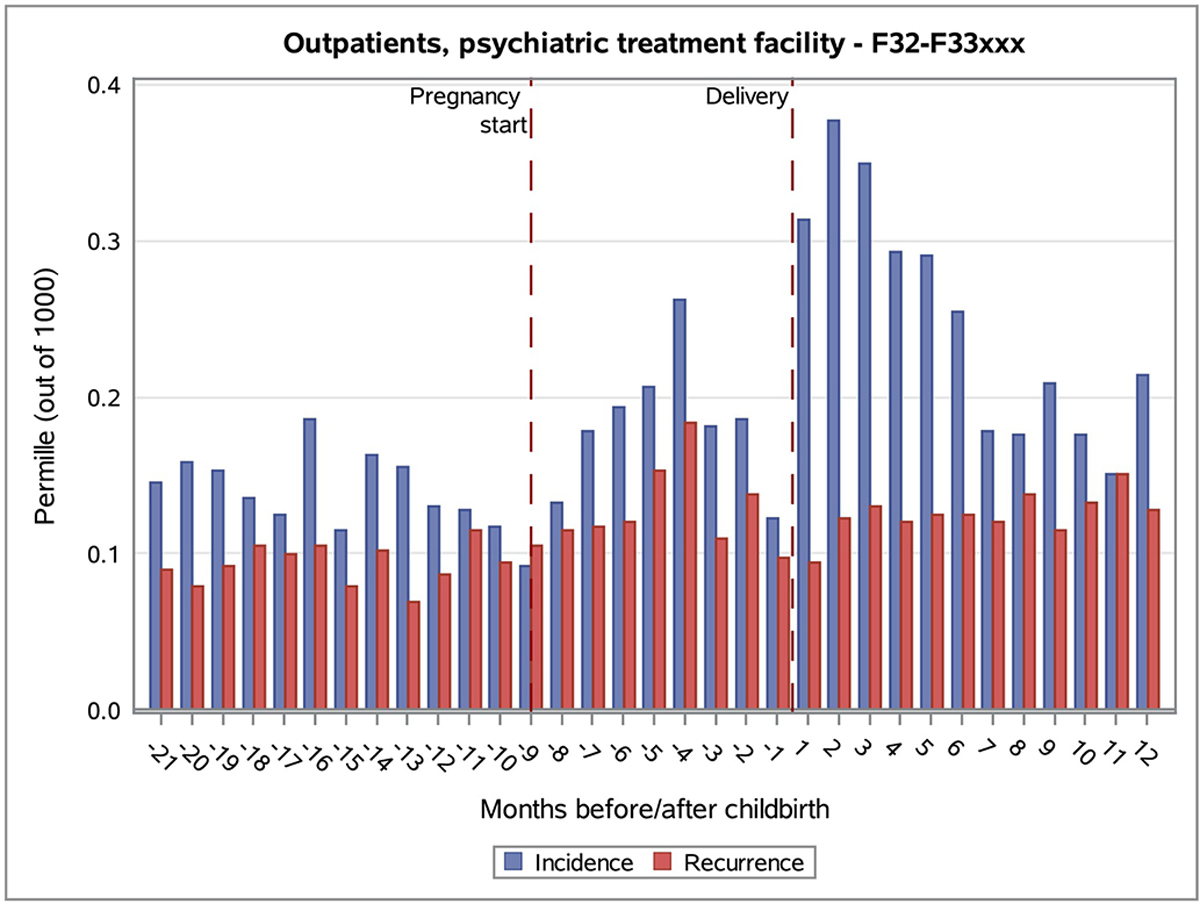

Psychiatric outpatient treatment

First-time number of depressive episodes treated at a psychiatric outpatient facility were highest the first five months after childbirth, while there appeared to be no substantial increase for recurring outpatient visits after childbirth (Figure 2). During pregnancy, an increase of both incidence and recurrence was seen from the first to second trimester, with a gradual decrease in the third trimester.

Figure 2.

Incidence and recurrence of outpatient psychiatric treatment for depression before, during, and after childbirth.

Discussion

Our data indicate that there is a peak in the incidence of moderate to severe and very severe depressive episodes the first months after delivery. After childbirth, a significant increase in first-time admissions was observed, reaching a maximum at two months after childbirth. Previous studies have identified a peak in mania and psychosis in the first months after childbirth (Munk-Olsen et al., 2006; Munk-Olsen and Agerbo, 2015; Valdimarsdóttir et al., 2009), and our study showed a similar peak for severe first-time depressive episodes. Our findings are in line with findings in an Australian population study from Xu et al. showing a rise in inpatients admissions for depression compared to the pre-pregnancy period, however this study did not include pregnancy data (Xu et al., 2012). In addition, we show a similar peak in outpatient treatment compared to inpatient treatment for depression in the first months postpartum. There is no indication for a peak in incidence or recurrence limited to the first four weeks after delivery and based on this specific observation, our results do not support the rationale for using this timeframe as specifier as is the case in the DSM-5.

Our data suggest that incidence and recurrence of depressive episodes change after conception. We found an increase in outpatient depression treatment during the first two trimesters of pregnancy, but not in the third trimester. This finding is novel, because prior reviews and meta-analyses have concluded that no conclusions can be made regarding the relative incidence of depression among pregnant (and postpartum) women compared with women at non-childbearing times (Gavin et al., 2005; Guo et al., 2018; Woody et al., 2017). The relative decrease in the third trimester has not been described in other studies either (Boekhorst et al., 2019; Santos et al., 2017). The increase we found in the prevalence during the first 2 trimester of pregnancy could be due to medication change as it well described by our group and others that up to 50% of women taper or stop antidepressant medication around conception (Molenaar et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2019).

For more severe depressive episodes, requiring psychiatric inpatient treatment, the pattern was very different. Remarkably, we found that for both first-time and recurrence rates of inpatient admissions, there seemed to be lower incidence and recurrence rates during pregnancy compared to both the preconception period and to the postpartum period. This has not been reported before, but a similar pattern has been described for all psychiatric episodes by a study from the UK, showing lower inpatient admission rates during pregnancy compared to pre- and post-pregnancy rates (Martin et al., 2016). Notably, this specific pattern of low incidence during pregnancy and a peak in the postpartum period, has been described for autoimmune diseases, such as Rheumatoid Arthritis, Multiple Sclerosis, or auto-immune thyroid disease (Airas and Kaaja, 2012; Amino et al., 1999; Krause and Makol, 2016; Littlejohn, 2020), and is linked to the immunologically suppressed state of pregnancy with a rebound postpartum. It is unclear if a similar mechanism holds true for severe depression or whether this pattern is better explained by endocrine changes, psychosocial changes occurring at the beginning of pregnancy and after delivery, trivialization by the patient or health care provider, stigma, and/or conception coinciding with improved mental health status (Branquinho et al., 2022; Button et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2004).

Limitations

Our study should be interpreted in light of its strengths and limitations. We had data available for the entire Danish female population across decades and based on a health care system providing free treatment for all ensuring no woman need to go untreated if she actively seeks help. We were able to compare monthly rates throughout pregnancy, allowing us to distinguish peak incidence by trimester, and in the post-delivery period. And importantly, we compared pregnancy and post-delivery rates to preconception rates. Limitations include analyses were performed on depressive episodes representing the severe end of the spectrum, questioning generalizability to milder forms of depression treated outside psychiatric specialist treatment facilities. In addition, this study provides summary statistics at a population level; it does not allow us to highlight the evolution of certain episodes which, for example, worsen over time. Interpretation of our results should further consider risk of potential bias with the calculated incidence and recurrence preconception and during pregnancy as these were conditional on the survival of the women during the months until delivery (conditioning on a future event). However, such bias is unlikely given the relatively young age of the women included in the study. As we condition on the future event (childbirth), we similarly acknowledge that incidence of depression in our pre-pregnancy/pregnancy group and incidence of depression in a female background population may not be completely identical.

Conclusion

In the DMS-5, the latest version of the DSM classification system, the specifier “depression with postpartum onset” was changed into “depression with peripartum onset”. We found a peak in severe and very severe depressive episodes after delivery while the first and second trimester of pregnancy had the highest incidence of moderate and severe depression onset. In light of our findings and those of others, we suggest distinguishing timing of onset: depression with pregnancy onset OR depression with postpartum onset, without limiting the onset to four weeks postpartum. This is important for both clinical practice as well as for future research endeavors.

Highlights.

Incidence of inpatient admission during pregnancy was lower than before pregnancy

Outpatient psychiatric treatment was higher during pregnancy than before pregnancy

The DSM-5 should not limit onset of postpartum depression to 4 weeks after birth

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health (grant number 1R01MH122869-01).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors state there is no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Airas L, Kaaja R, 2012. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis. Obstet Med 5, 94–7. 10.1258/om.2012.110014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altemus M, Neeb CC, Davis A, Occhiogrosso M, Nguyen T, Bleiberg KL, 2012. Phenotypic differences between pregnancy-onset and postpartum-onset major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 73. 10.4088/JCP.12m07693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amino N, Tada H, Hidaka Y, 1999. Postpartum autoimmune thyroid syndrome: A model of aggravation of autoimmune disease, in: Thyroid. Mary Ann Liebert Inc., pp. 705–713. 10.1089/thy.1999.9.705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batt MM, Duffy KA, Novick AM, Metcalf CA, Epperson CN, 2020. Is Postpartum Depression Different From Depression Occurring Outside of the Perinatal Period? A Review of the Evidence. 10.1176/appi.focus.20190045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekhorst MGBM, Beerthuizen A, Endendijk JJ, van Broekhoven KEM, van Baar A, Bergink V, Pop VJM, 2019. Different trajectories of depressive symptoms during pregnancy. J Affect Disord 248, 139–146. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branquinho M, Shakeel N, Horsch A, Fonseca A, 2022. Frontline health professionals’ perinatal depression literacy: A systematic review. Midwifery 111. 10.1016/J.MIDW.2022.103365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button S, Thornton A, Lee S, Ayers S, Shakespeare J, 2017. Seeking help for perinatal psychological distress: a meta-synthesis of women’s experiences. The British Journal of General Practice 67, e692. 10.3399/BJGP17X692549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Florio A, Meltzer-Brody S, 2015. Is Postpartum Depression a Distinct Disorder? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 10.1007/s11920-015-0617-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T, 2005. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics and gynecology 106, 1071–1083. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.DB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo N, Robakis T, Miller C, Butwick A, 2018. Prevalence of Depression among Women of Reproductive Age in the United States. Obstetrics and Gynecology 131, 671–679. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICD-10-CM Code F32 - Major depressive disorder, single episode [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://icd.codes/icd10cm/F32 (accessed 2.24.21). [Google Scholar]

- ICD-10-CM Code F33 - Major depressive disorder, recurrent [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://icd.codes/icd10cm/F33 (accessed 2.24.21). [Google Scholar]

- Jolley SN, Betrus P, 2007. Comparing postpartum depression and major depressive disorder: Issues in assessment. Issues Ment Health Nurs 28, 765–780. 10.1080/01612840701413590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause ML, Makol A, 2016. Management of rheumatoid arthritis during pregnancy: Challenges and solutions. Open Access Rheumatol. 10.2147/OARRR.S85340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohn EA, 2020. Pregnancy and rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Plana-Ripoll O, Ingstrup KG, Agerbo E, Skjærven R, Munk-Olsen T, 2020. Postpartum psychiatric disorders and subsequent live birth: a population-based cohort study in Denmark. Hum Reprod 35, 958–967. 10.1093/humrep/deaa016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JL, McLean G, Cantwell R, Smith DJ, 2016. Admission to psychiatric hospital in the early and late postpartum periods: Scottish national linkage study. BMJ Open 6, e008758. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar NM, Lambregtse-van den Berg MP, Bonsel GJ, 2019. Dispensing patterns of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors before, during and after pregnancy: a 16-year population-based cohort study from the Netherlands. Arch Womens Ment Health. 10.1007/s00737-019-0951-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB, 2011. The Danish psychiatric central research register. Scand J Public Health 39, 54–57. 10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munk-Olsen T, Agerbo E, 2015. Does childbirth cause psychiatric disorders? A population-based study paralleling a natural experiment. Epidemiology 26, 79–84. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Mors O, Mortensen PB, 2006. New parents and mental disorders: A population-based register study. J Am Med Assoc 296, 2582–2589. 10.1001/jama.296.21.2582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musliner KL, Liu X, Gasse C, Christensen KS, Wimberley T, Munk-Olsen T, 2019. Incidence of medically treated depression in Denmark among individuals 15–44 years old: a comprehensive overview based on population registers. Acta Psychiatr Scand 139, 548–557. 10.1111/acps.13028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CB, 2011. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health 39, 22–25. 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam KT, Wilcox M, Robertson-Blackmore E, Sharkey K, Bergink V, Munk-Olsen T, Deligiannidis KM, Payne J, Altemus M, Newport J, Apter G, Devouche E, Viktorin A, Magnusson P, Penninx B, Buist A, Bilszta J, O’Hara M, Stuart S, Brock R, Roza S, Tiemeier H, Guille C, Epperson CN, Kim D, Schmidt P, Martinez P, Di Florio A, Wisner KL, Stowe Z, Jones I, Sullivan PF, Rubinow D, Wildenhaus K, Meltzer-Brody S, 2017. Clinical phenotypes of perinatal depression and time of symptom onset: analysis of data from an international consortium. Lancet Psychiatry 4, 477–485. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30136-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos H, Tan X, Salomon R, 2017. Heterogeneity in perinatal depression: how far have we come? A systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 10.1007/s00737-016-0691-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. v., Rosenheck RA, Cavaleri MA, Howell HB, Poschman K, Yonkers KA, 2004. Screening for and detection of depression, panic disorder, and PTSD in public-sector obstetric clinics. Psychiatr Serv 55, 407–414. 10.1176/APPI.PS.55.4.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe ZN, Hostetter AL, Newport DJ, 2005. The onset of postpartum depression: Implications for clinical screening in obstetrical and primary care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 192, 522–526. 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.07.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Dreier JW, Liu X, Glejsted Ingstrup K, Mægbæk ML, Munk-Olsen T, Christensen J, 2019. Trend of antidepressants before, during, and after pregnancy across two decades-A population-based study. Brain Behav 9. 10.1002/BRB3.1441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uher R, Payne JL, Pavlova B, Perlis RH, 2014. Major depressive disorder in DSM-5: Implications for clinical practice and research of changes from DSM-IV. Depress Anxiety. 10.1002/da.22217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdimarsdóttir U, Hultman CM, Harlow B, Cnattingius S, Sparén P, 2009. Psychotic illness in first-time mothers with no previous psychiatric hospitalizations: a population-based study. PLoS Med 6, e13. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody CA, Ferrari AJ, Siskind DJ, Whiteford HA, Harris MG, 2017. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J Affect Disord. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Austin MP, Reilly N, Hilder L, Sullivan EA, 2012. Major depressive disorder in the perinatal period: Using data linkage to inform perinatal mental health policy. Arch Womens Ment Health 15, 333–341. 10.1007/s00737-012-0289-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]