Abstract

Using sera from mice immunized and protected against Plasmodium yoelii malaria, we identified a novel blood-stage antigen gene, pypag-2. The 2.1-kb pypag-2 cDNA contains a single open reading frame that encodes a 409-amino-acid protein with a predicted molecular mass of 46.8 kDa. Unlike many characterized plasmodial antigens, blocks of tandemly repeated amino acids are lacking in the pypAg-2 protein sequence. Recombinant pypAg-2, comprising the full-length protein minus the predicted N-terminal signal and C-terminal anchor sequences, was produced and used to raise a high-titer polyclonal rabbit antiserum. This antiserum was used to identify and characterize the native protein through immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence assays. Consistent with the presence of a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor, pypAg-2 fractionated with the detergent phase of Triton X-114-solubilized proteins and could be metabolically labeled with [3H]palmitic acid. By immunofluorescence, pypAg-2 expression was localized to both the trophozoite and merozoite membranes. Similar to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1, pypAg-2 contains two C-terminal epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains. Most importantly, immunization with recombinant pypAg-2 protected mice against lethal P. yoelii malaria. Thus, pypAg-2 is a target of protective immune responses and represents a novel addition to the family of merozoite surface proteins that contain one or more EGF-like domains.

Efforts to develop an effective malaria vaccine are concentrated on Plasmodium falciparum, the major cause of malaria morbidity and mortality worldwide (45). Several promising vaccine targets have been identified in each of the major developmental stages of this protozoan parasite (24). These P. falciparum vaccine candidate antigens have been largely identified based on their functional importance and/or as targets of human immune responses. Additional in vivo studies involving the rodent malaria parasites Plasmodium yoelii and Plasmodium chabaudi have facilitated efforts to assess the vaccine potential of several antigens of interest (3, 5, 9, 11, 14–16, 26, 28, 30, 34, 42). Evaluation of the most promising candidate antigens has progressed to human clinical trials, and the initial results are encouraging (18). Even so, it is clear that further efforts to improve overall malaria vaccine efficacy are needed. This includes the characterization of additional parasite antigens and epitopes that induce protective responses upon immunization.

Blood-stage malaria vaccine studies have emphasized the mapping of B-cell epitopes of plasmodial antigens that are targets of protective antibodies. Many immunodominant, linear B-cell epitopes have been identified in association with domains of proteins that contain repeated blocks of amino acids. Many of these determinants are polymorphic and have been suggested to be part of an immune evasion strategy (31, 37). On the other hand, P. falciparum repeat domains, such as those found in the circumsporozoite protein, the ring-infected erythrocyte surface antigen, the serine repeat antigen, and merozoite surface protein 2 (MSP-2) may in fact be targets of protective antibodies (27). A second, very different group of potentially protective B-cell epitopes has been mapped to domains of malaria antigens that are conformationally constrained by multiple disulfide bonds. In P. falciparum, these include the cytoadherence domains of erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (4), the ectodomain of apical membrane antigen 1 (3, 14, 23, 44), the binding domain of the 175-kDa erythrocyte binding antigen (1, 32), and as a group, the epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains of MSP-1, MSP-4, MSP-5, and the sexual-stage antigens Pfs25 and Pfs28 (5, 11, 15, 17, 25, 29, 30, 35, 36). Generally these epitopes are less variable between P. falciparum strains, exhibit conservation across species, and appear to be functionally important. As such, they are of considerable interest for malaria vaccine development.

Previously, we reported that immunization with a particulate fraction of blood-stage antigens (pAg) can protect mice against P. yoelii malaria (10). We attempted to utilize the responses of these immunized and protected animals to identify novel, protective blood-stage antigens. One such antigen, pypAg-1, is a novel membrane protein of P. yoelii-infected erythrocytes that was shown to express at least two distinct protective epitopes (8). Using this immunization-based approach to antigen discovery, we now report the identification and characterization of pypAg-2, a second novel antigen of P. yoelii. We present data indicating that pypAg-2 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane protein of trophozoites and merozoites that lacks repetitive amino acid sequences but contains two C-terminal EGF-like domains. Most importantly, we report that immunization with recombinant pypAg-2 protects mice against lethal P. yoelii blood-stage malaria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental infections.

Male BALB/cByJ mice, 5 to 6 weeks of age, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) and housed in the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-approved Animal Care Facility of Meharry Medical College. Routine screenings were conducted throughout these studies to ensure that mice remained free of infection with common viral and bacterial pathogens (Assessment Plus Profile; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.). The lethal 17XL strain of P. yoelii was originally obtained from William P. Weidanz (University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wis.) and was maintained as cryopreserved stabilates. Blood-stage infections were initiated by intraperitoneal injection of parasitized erythrocytes obtained from donor mice. The resulting parasitemias were monitored by enumerating parasitized erythrocytes in tail blood thin smears stained with Giemsa.

Immune sera.

Sera from five CByB6F1/J mice were obtained 1 week following secondary immunization with pAg but prior to infection. The generation and characterization of these sera and nonimmune adjuvant control sera have been previously reported (10).

A high-titer rabbit antiserum was commercially prepared against purified recombinant pAg-2 (Lampire Biological Laboratories, Pipersville, Pa.). Rabbits received a total of five immunizations over an 8-week period. Each dose contained 200 μg of purified antigen. The first immunization was with antigen emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA). For subsequent boosts, antigen was administered in incomplete Freund's adjuvant. Preimmune serum was collected prior to the first immunization. Immune serum was collected 2 weeks following the final immunization.

Cloning and sequence analysis.

A P. yoelii 17XL cDNA library was constructed in the lambda Uni-ZAP XR expression vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) using poly(A)+ RNA from a mixture of ring, trophozoite, and schizont blood-stage parasites. The library was screened with a pool of sera from mice protected against P. yoelii malaria by pAg immunization. The library construction, screening, and excision of pBSK(−) phagemid sequences have been described previously (8). Of 26 seroreactive recombinant clones identified, 2 were shown to contain pypag-2 sequences by cross-hybridization studies and partial-sequence analysis.

Nested deletions of one pypag-2 cDNA clone were generated by exonuclease III digestion (22) and used to obtain the complete sequences of the coding and noncoding strands. Single-stranded template was prepared, and the sequence was obtained by Sanger dideoxynucleotide chain termination with [35S]dATP (1,250 Ci/mmol; NEN Life Science Products, Boston, Mass.) (40) or by fluorescence-based sequencing using an ABI Prism 377 automated DNA sequencer (work performed at Molecular Biology Core Facility, Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tenn.). Sequence analysis utilized a DNASIS for Windows software package (Hitachi Software, South San Francisco, Calif.). Data bank searches for related sequences were conducted using the BLAST programs available through the National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine (2).

Production of recombinant pypAg-2.

Recombinant pypAg-2 protein (rpAg-2) was produced in Escherichia coli using the pET plasmid vectors and T7 RNA polymerase expression system (43). The complete coding sequence minus the N-terminal signal sequence and hydrophobic C-terminal anchor sequence was PCR amplified from the pypag-2 cDNA clone by using oligonucleotide primers 5′-TTTCATATGGGGAATTGTAATGAAAATGGAAACG-3′ (based on nucleotides 307 to 340) and 5′-CATTCATTCCTCGAGAAATGGCTCATGAACAATA-3′ (based on nucleotides 1402 to 1435) as 5′ and 3′ primers, respectively. To facilitate subcloning, NdeI and XhoI restriction sites were incorporated into the 5′ and 3′ primers, respectively. The amplified fragment was gel purified, digested with NdeI and XhoI, and ligated into NdeI-XhoI-digested pET-15b (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). E. coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS was used for expression. rpAg-2 contained 20 plasmid-encoded amino acids fused to its N terminus, which included six histidine residues.

Bacteria pelleted from 250 ml of induced culture were resuspended in 15 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM dithiothreitol) and lysed by treatment with lysozyme followed by sonication. The 45-kDa rpAg-2 was purified from a soluble fraction of lysed bacteria obtained following centrifugation for 20 min at 25,000 × g. A 25 to 60% ammonium sulfate fraction of the initial lysate was dialyzed into 5 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 3.5). The rpAg-2 was precipitated a second time with ammonium sulfate and then purified by nickel-chelate affinity chromatography (Ni-NTA Superflow matrix; Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, Calif.) in the presence of 6 M guanidine-HCl. To facilitate refolding, the eluted protein was dialyzed into renaturation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM reduced glutathione, 0.3 mM oxidized glutathione) containing 4 M guanidine-HCl. The concentration of guanidine-HCl in renaturation buffer was then sequentially reduced (4, 2, 1, and 0.5 M) by further dialysis (41). The final dialysis buffer contained 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 100 mM NaCl. The protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Protein purity was assessed by Coomassie blue staining following sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (33). The yield of purified rpAg-2 was approximately 1 mg per liter of induced bacterial culture.

Immunoblot analysis.

Total P. yoelii 17XL blood-stage antigen and the corresponding pAg fraction were prepared as described previously (10) and solubilized in SDS-PAGE sample buffer with 2.5% SDS and 5% 2-mercaptoethanol. Total blood-stage antigen (10 μg/lane), the pAg fraction (10 μg/lane), and purified rpAg-2 (1 μg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels under reducing conditions by the method of Laemmli (33) and analyzed by immunoblotting (8). Control and pAg immunization mouse sera were assayed at a dilution of 1:100. Preimmune and immune rabbit sera were diluted 1:500. Bound antibody was detected with 125I-protein A (ICN Biomedicals, Irvine, Calif.).

Triton X-114 solubilization and phase separation of parasite membrane proteins were carried out by modification of a previously described protocol (12). Briefly, blood at approximately 25% parasitemia was collected from P. yoelii 17XL-infected mice, washed, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 0.1% glucose and 0.01% saponin to lyse erythrocytes. Intact parasites were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 5 volumes of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–140 mM NaCl–5% Triton X-114 (Pierce). The parasites were then incubated for 15 to 20 min on ice. Triton X-114-solubilized material was warmed to 34°C for an additional 15 min to permit a temperature-dependent phase separation. Aqueous and detergent phases were separated by centrifugation (1,600 × g for 10 min) at 30°C through a 6% sucrose pad. Following the recovery of the upper, aqueous phase, the detergent phase was diluted to its original volume in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–140 mM NaCl. Equivalent fractions of aqueous-phase proteins and detergent-phase membrane proteins were assayed by immunoblotting.

Immunoprecipitation studies.

Blood from P. yoelii 17XL-infected mice (25 to 30% parasitemia) was collected and washed three times in medium. Erythrocytes were resuspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 2.5 mg of glucose per ml, 20 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) (pH 7.4), 0.1 mM hypoxanthine, and 50 μg of gentamicin per ml (0.2 ml [packed-cell volume] per ml of medium). [3H]palmitic acid (30 to 60 Ci/mmol; NEN Life Science Products Inc.) was added to 100 μCi/ml, and the parasitized cells were incubated at 37°C in 7% CO2 for 4 h. Palmitic acid is incorporated into the GPI anchors of several protozoan surface proteins, including those of P. falciparum MSP-1 and MSP-2 (20, 21). Following incubation, cells were collected by centrifugation at 1,800 × g for 10 min and solubilized on ice in 10 volumes of buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 mM iodoacetic acid. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h.

Approximately 106 cpm of metabolically labeled, trichloroacetic acid-precipitable proteins of P. yoelii 17XL were used for subsequent immunoprecipitations. [3H]palmitic acid-labeled pypAg-2 was immunoprecipitated with rabbit antiserum raised against rpAg-2 (diluted 1:50) along with protein A-agarose (Life Technologies, Frederick, Md.). Precipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels and visualized by fluorography.

Indirect-immunofluorescence assay.

The indirect-immunofluorescence assay to localize the expression of pypAg-2 was conducted as previously reported (8). Thin smears of P. yoelii 17XL-infected erythrocytes were air dried and fixed in acetone-methanol. Preimmune and immune rabbit sera were assayed at a dilution of 1:200 in PBS. The secondary antibody utilized was fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) diluted 1:160 in PBS. Stained cells were washed, mounted with Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, Ala.), and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. For assays of merozoites, an enriched preparation of P. yoelii 17XL schizonts was prepared by centrifugation of parasitized blood through a 15 to 30% metrizamide step gradient (19).

Immunizations.

Groups of five BALB/cByJ mice were immunized subcutaneously with 25 μg of rpAg-2 in adjuvant, adjuvant alone, or PBS alone. Following the primary immunization, the animals were boosted twice at 3-week intervals with the same dose of antigen. In the first experiment, RAS (50 μg of monophosphoryl lipid A plus 50 μg of synthetic trehalose dicorynomycolate [Ribi ImmunoChem Research Inc., Hamilton, Mont.]) was utilized as the adjuvant for all three immunizations. In the second experiment, rpAg-2 was emulsified in CFA (1:1 emulsion [Life Technologies]) for the primary immunization. For the two remaining boosts, CFA was replaced with recombinant mouse interleukin-12 (IL-12) (1 μg/dose) (R & D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, Minn.). Ten days following the third immunization, mice were infected intraperitoneally with 105 P. yoelii 17XL parasitized erythrocytes and blood parasitemias were monitored. The statistical significance of differences in mean parasitemia between immunized and control groups was calculated by analysis of variance using the StatMost statistical analysis software package (DataMost Corp., Salt Lake City, Utah).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession number AY005132.

RESULTS

pypag-2 encodes a novel P. yoelii blood-stage antigen.

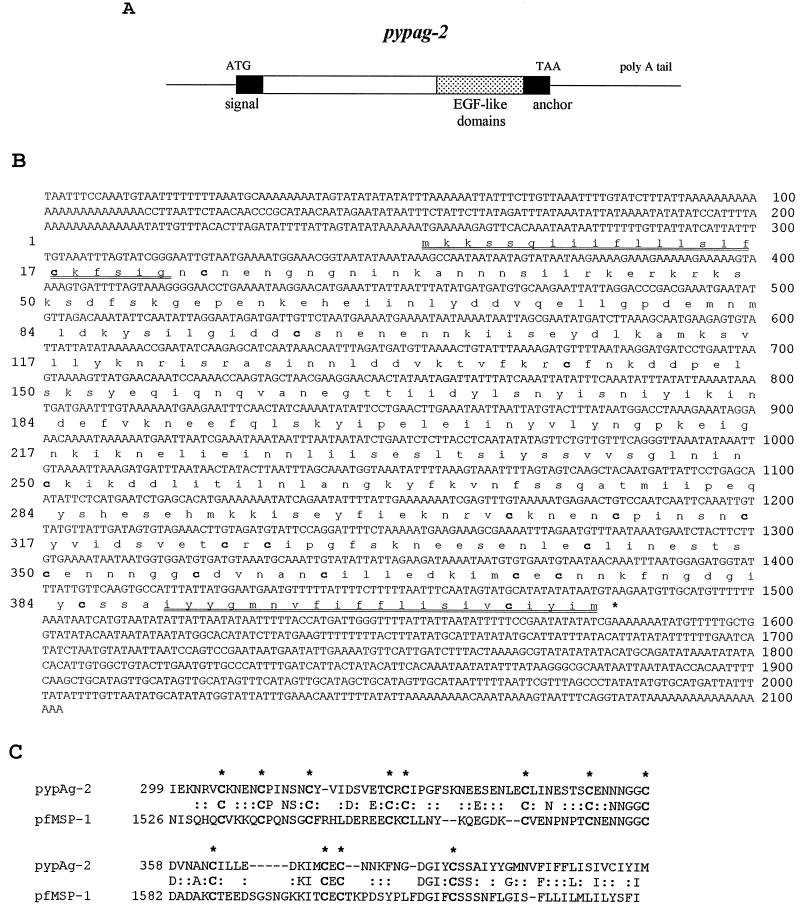

The pypag-2 gene of P. yoelii was identified during the screening of a cDNA expression library with sera from mice immunized with a protective fraction of P. yoelii blood-stage antigens (8). The complete coding and noncoding strands of pypag-2 were determined from the largest of the pypag-2 cDNA clones isolated (Fig. 1A and B). This cDNA contains 2,103 bp with a single open reading frame from nucleotides 253 through 1482. The encoded protein is 409 amino acids in length, with a predicted molecular mass of 46.8 kDa and isoelectric point of 4.81. An N-terminal signal sequence (amino acids 1 to 22) and a C-terminal hydrophobic anchor sequence (amino acids 389 to 409) are predicted. Unlike many characterized plasmodial antigens, blocks of repeated amino acids are lacking in the predicted pypAg-2 protein. Of particular interest, pypAg-2 contains 18 cysteine residues, with 14 of these found within the C-terminal 160 amino acids. Data bank searches revealed significant similarities between this C-terminal cysteine-rich domain of pypAg-2 and the C terminus of P. falciparum MSP-1 (Fig. 1C). The two sequences have approximately 33% identity over 115 amino acids with alignment of 12 cysteine residues. These 12 cysteine residues mediate the folding of the C terminus of MSP-1 into two EGF-like domains (39). Outside of this domain, pypAg-2 has little similarity to MSP-1 or other known protein sequences.

FIG. 1.

Sequence analysis of pypag-2. (A) Diagramatic representation of the pypag-2 cDNA sequence. (B) DNA and deduced amino acid sequences of the 2,103-bp insert of pypag-2. Cysteine residues are indicated in bold. The predicted N-terminal signal sequence and C-terminal hydrophobic anchor sequence are doubly underlined. (C) Amino acid alignment of the C-terminal cysteine-rich domains of pypAg-2 and P. falciparum MSP-1 (accession number X02919). Identical residues are indicated by letter, and conservative and neutral substitutions are indicated by colons. The 12 cysteine residues of P. falciparum MSP-1 that form the two EGF-like domains are indicated in bold and highlighted by asterisks.

Identification of native pypAg-2.

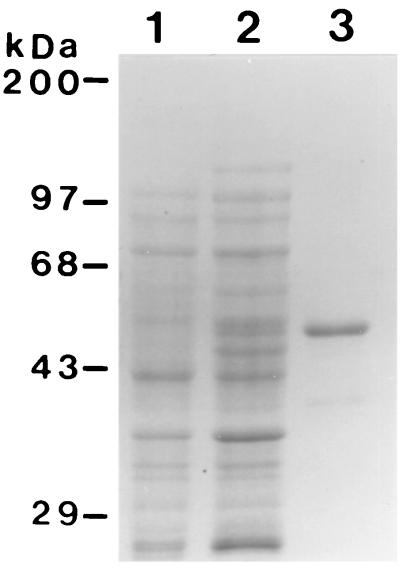

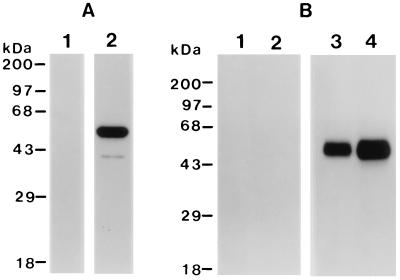

A 45-kDa pypAg-2 recombinant protein was expressed in E. coli, purified by nickel-chelate affinity chromatography, and refolded in the presence of glutathione to facilitate disulfide bond formation. rpAg-2 contained the complete coding sequence of pypAg-2 minus the hydrophobic N-terminal signal and C-terminal anchor sequences. Figure 2 shows a Coomassie blue-stained polyacrylamide gel of purified rpAg-2. Immunoblot analysis confirmed the strong reactivity of rpAg-2 with the pAg immunization serum pool that was initially used to screen the P. yoelii expression library (Fig. 3A, lane 2). Control sera from mice immunized with adjuvant alone were nonreactive with purified rpAg-2 (lane 1).

FIG. 2.

Expression and purification of rpAg-2. A Coomassie blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel containing E. coli lysates of uninduced (lane 1) and induced (lane 2) cells expressing rpAg-2 and purified rpAg-2 alone (2.5 μg, lane 3) is shown. Molecular mass markers are indicated.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot analysis of recombinant and native pypAg-2. (A) Immunoblot of purified rpAg-2 probed with sera from mice immunized with the protective pAg preparation of P. yoelii blood-stage antigens (lanes 2) or with sera from adjuvant control mice (lane 1). (B) Immunoblot of P. yoelii total blood-stage antigen (lanes 1 and 3) or protective pAg fraction (lanes 2 and 4) probed with preimmune rabbit serum (lanes 1 and 2) or rabbit antiserum raised against rpAg-2 (lanes 3 and 4). Molecular mass markers are indicated.

A high-titer polyclonal antiserum was obtained from rabbits immunized with purified rpAg-2. By using this antiserum in immunoblot studies, the native pypAg-2 protein was identified as a prominent protein present in both a total P. yoelii blood-stage antigen preparation (Fig. 3B, lane 3) and the protective pAg fraction (lane 4). Native pypAg-2 appeared as a somewhat diffuse band, with an approximate migration of 46 to 49 kDa. Immunoreactive proteins with lower molecular masses were absent, suggesting little or no proteolytic processing of pypAg-2. Likewise, no cross-reactivity was noted with the 230-kDa precursor of P. yoelii MSP-1 or any of its smaller processed products. The reactivity of preimmune rabbit serum with the P. yoelii antigen preparations was uniformly negative (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 2).

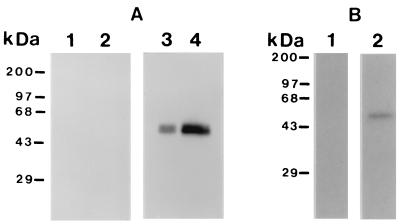

pypAg-2 is a GPI-anchored membrane protein.

The prediction of signal and anchor sequences in pypAg-2, combined with the similarity to MSP-1, suggested that pypAg-2 might also be a GPI-anchored membrane protein. To test for membrane association, P. yoelii blood-stage antigens were solubilized in Triton X-114 and partitioned into aqueous and detergent phases. Phase-separated proteins were then assayed by immunoblotting using the polyclonal rabbit serum raised against rpAg-2. As shown in Fig. 4A, pypAg-2 fractionated predominantly in the Triton X-114 detergent phase (lane 4), with only a small amount detected in the aqueous phase (lane 3). These data support the conclusion that pypAg-2 is in fact membrane associated. To determine if the membrane association of pypAg-2 was mediated by a GPI anchor, the rpAg-2 rabbit antiserum was used to immunoprecipitate P. yoelii 17XL blood-stage proteins metabolically labeled with [3H]palmitic acid. As shown in Fig. 4B, pypAg-2 labeled with [3H]palmitic acid was immunoprecipitated with the rpAg-2 antiserum (lane 2) but not with preimmune rabbit serum (lane 1). Combined, these data indicate that pypAg-2 is a GPI-anchored membrane protein.

FIG. 4.

Membrane association of pypAg-2. (A) Immunoblot of Triton X-114 aqueous-phase (lanes 1 and 3) and detergent-phase (lanes 2 and 4) proteins of P. yoelii blood-stage parasites probed with preimmune rabbit serum (lanes 1 and 2) or rabbit antiserum raised against rpAg-2 (lanes 3 and 4). (B) Immunoprecipitation of P. yoelii 17XL blood-stage antigens metabolically labeled with [3H]palmitic acid using preimmune rabbit serum (lanes 1) or rabbit antiserum raised against rpAg-2 (lanes 2). Molecular mass markers are indicated.

pypAg-2 is expressed on trophozoite and merozoite membranes.

The membrane association of pypAg-2 was further investigated by indirect immunofluorescence. Thin films of P. yoelii-parasitized erythrocytes were prepared, air dried, fixed, and reacted with the polyclonal rabbit antiserum raised against rpAg-2. Bound antibody was detected with a FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody. The expression of pypAg-2 was localized both to the trophozoite membrane (Fig. 5B) and to the membrane of merozoites prior to schizont rupture (Fig. 5C). No fluorescence of P. yoelii-parasitized erythrocytes incubated with preimmune rabbit serum was apparent (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Immunofluorescence staining of fixed smears of erythrocytes infected with P. yoelii. Thin blood smears were incubated with preimmune rabbit serum (A) or rabbit antiserum raised against rpAg-2 (B and C) followed by a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. The same fields of cells were examined by phase-contrast (left panels) and fluorescence (right panels) microscopy.

Immunization with rpAg-2 protects against lethal P. yoelii malaria.

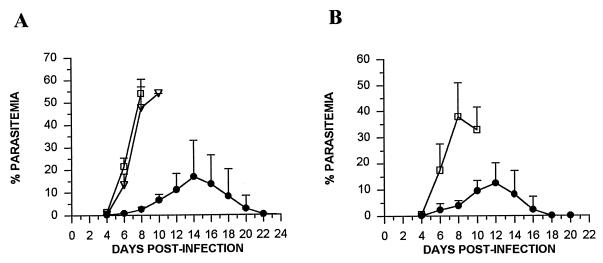

To determine if pypAg-2 is a target of protective immune responses, mice were immunized with rpAg-2 in adjuvant and challenged with lethal P. yoelii 17XL. In the first experiment, mice were immunized with rpAg-2 formulated with RAS. As shown in Fig. 6A, rpAg-2 immunization protected mice against a lethal challenge infection. Uncontrolled parasitemia developed in animals immunized with RAS or PBS alone. As the parasitemia progressed to a high level in control mice, they became moribund, and all were euthanized by day 10 postinfection. In contrast, rpAg-2-immunized mice controlled their infection during this 10-day period, with blood parasitemia not exceeding 10%. Parasitemia peaked in rpAg-2 mice between days 10 and 14, ranging from 4.7 to 34.5% (mean, 19.19% ± 13.08%). All rpAg-2 immunized mice resolved in their infection by day 22 of infection.

FIG. 6.

Protection against lethal P. yoelii malaria induced by immunization with rpAg-2. (A) Groups of five BALB/cByJ mice were immunized with rpAg-2 (●) with RAS as adjuvant. Five control animals were immunized with RAS alone (□) or PBS (▿). (B) Groups of five BALB/cByJ mice were immunized with rpAg-2 (●) with CFA and IL-12 as the adjuvant. Five control animals were immunized with CFA and IL-12 alone (□). Animals were boosted twice at 3-week intervals and challenged with 105 P. yoelii 17XL-parasitized erythrocytes. The resulting parasitemias were monitored by enumerating parasitized RBCs in tail blood thin smears stained with Giemsa and are expressed as the mean and standard deviation. Differences in mean parasitemia between immunized and control mice were statistically significant on days 4 to 10 (P < 0.05 by analysis of variance).

In the second experiment, mice received a single immunization with rpAg-2 emulsified in CFA followed by booster immunizations with rpAg-2 plus IL-12. Upon P. yoelii 17XL challenge, adjuvant-treated control animals developed fulminant infection, and all were euthanized by day 11. As in the first experiment, parasitemia in rpAg-2-immunized mice was markedly reduced, reaching only 9.41% ± 4.12% by day 10 (Fig. 6B). Again, the parasitemia in rpAg-2-immunized animals subsequently increased, with a mean peak of 14.96% ± 7.16%. All rpAg-2-immunized mice survived and cleared their blood parasitemia by day 18 of infection. Combined, these data indicated that immunization with pypAg-2 confers a significant level of protection against lethal P. yoelii malaria.

DISCUSSION

In our previous studies, immunization of mice with a particulate fraction of blood-stage antigens protected against P. yoelii malaria (10). Although reduced in complexity, the immunizing antigen preparation contained a mixture of blood-stage proteins. Consequently, we expected that multiple targets of the protective response existed. Further studies showed that the pAg-induced protection was B-cell dependent and associated with the production of antibodies that recognized six to eight P. yoelii antigens. As such, the number of antigens contributing to the protective response appeared to be limited. Using the P. yoelii pAg immunization sera, we have attempted to define those protective targets.

We previously characterized pypAg-1 as one P. yoelii antigen that contributed to the pAg-induced protection. This antigen is expressed by P. yoelii trophozoites, exported to the erythrocyte membrane, and eventually secreted from infected erythrocytes (7, 8). In addition to a putative transmembrane domain, the N-terminal portion of pypAg-1 contains a domain unusually rich in tryptophan residues. This tryptophan-rich domain is conserved in pypAg-3, another P. yoelii antigen with a similar pattern of expression that was also identified with the pAg immunization serum (7). The C terminus of pypAg-1 contains a 155-amino-acid, highly charged repeat domain. Immunization with either the N-terminal or C-terminal domains of pypAg-1 induced a four- to sevenfold reduction in P. yoelii 17X blood-stage parasitemia (8). While significant, this was several-fold less than the maximal level of protection induced by crude pAg immunization, suggesting that additional components were involved. One of these components appears to be pypAg-2.

pypAg-2 is distinct from both pypAg-1 and pypAg-3 relative to their DNA and deduced amino acid sequences and patterns of expression. PypAg-2 is a GPI-anchored protein, expressed in association with the trophozoite and merozoite membranes. In contrast to many malaria vaccine candidate antigens, pypAg-2 lacks a characteristic immunodominant repeat domain. The most striking feature of pypAg-2 is the presence of two EGF-like domains at its C terminus. These EGF-like domains have now been identified in at least five P. falciparum vaccine candidate antigens including MSP-1 and generally appear to be targets of protective antibodies (17, 25, 29, 35, 36).

The C-terminal EGF-like domains of P. falciparum MSP-1 are well characterized in terms of structure, function, sequence polymorphism, and vaccine potential (25, 39). The combined data make P. falciparum MSP-1 the leading blood-stage vaccine candidate antigen at present. Antibody to the EGF-like domains of MSP-1 blocks merozoite invasion of erythrocytes in vitro (6, 13) and confers immunity to challenge infection in animal models (15). The similarity between the EGF-like domains of pypAg-2 and MSP-1, combined with the expression of pypAg-2 on merozoites, raise the possibility that pypAg-2 is also involved in parasite invasion of erythrocytes. MSP-1 and pypAg-2 have little sequence similarity beyond the C-terminal EGF-like domains. Likewise, the sequence of pypAg-2 differs significantly from those of P. falciparum MSP-4 (35) and MSP-5 (36) as well as of the single fused protein MSP-4/5 of P. chabaudi (5), P. yoelii, and P. berghei (30); additional merozoite surface antigens that each contain a single EGF-like domain. Like MSP-4, however, pypAg-2 appears to be expressed on the trophozoite membrane early in the erythrocyte cycle, prior to its association with the membrane of merozoites (5, 35).

The immunization and challenge experiments provided the key data to establish the protective potential of pypAg-2. Mice immunized with rpAg-2 by using RAS or a combination of CFA and IL-12 as adjuvant resisted an otherwise lethal P. yoelii 17XL challenge. RAS was chosen as a good adjuvant for the overall induction of antibody responses. The CFA-plus-IL-12 combination was selected to promote the production of Th1-associated IgG isotypes (IgG2a and IgG3). Both adjuvants were equally efficient in promoting protective pypAg-2 responses. While a significant increase in the prepatent period was not observed, rpAg-2-immunized mice largely controlled their P. yoelii 17XL infection for the first 8 to 10 days. Parasitemia increased shortly thereafter but was ultimately suppressed. This breakthrough in parasitemia may have resulted from the consumption of immunization-induced antibodies to pypAg-2. It is also worth noting, however, that the late rise in parasitemia occurred as the infection shifted from mature erythrocytes to reticulocytes. This suggests that the level of protection induced by pypAg-2 immunization may in part depend on the type of host erythrocyte infected. This may be particularly relevant to human malaria, given that P. falciparum also infects mature erythrocytes as well as reticulocytes. In the end, we believe that immunization with a combination of pypAg-1, pypAg-2, and pypAg-3 will significantly increase overall protective efficacy. Since these three antigens were identified based on the same protective immunization strategy, it should be possible to optimally formulate such a combination.

Finally, one hallmark of the EGF-like domains of malarial proteins characterized thus far is their conservation across species of Plasmodium, including the rodent malarial parasites. For example, the EGF-like domains of P. falciparum MSP-1 and MSP-4 are conserved in the homologous antigens of P. yoelii, P. chabaudi, and P. berghei (5, 9, 30, 38, 46). By cross-hybridization with pypAg-2 probes, we have isolated genomic clones encoding related P. falciparum antigens. Based on the conservation of the two C-terminal EGF-like domains, we believe that we have cloned the P. falciparum homologue of pypAg-2 (C. C. Belk, P. D. Dunn, and J. M. Burns, Jr., Abstr. 48th Annu. Meet. Am. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg., abstr. 128, 1999). Furthermore, two partial sequences of this antigen gene have been deposited in the P. falciparum genome sequencing database at the Sanger Center (chromosomes 5 and 6). Therefore, we anticipate that our studies of pypAg-2 in the P. yoelii model will contribute to ongoing efforts to develop a P. falciparum blood-stage vaccine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Donna M. Russo, Department of Microbiology, Meharry Medical College, for helpful discussions and critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH-NIAID grant AI35661 and NIH Research Centers in Minority Institutions grant G12RR03032.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams J H, Sim B K L, Dolan S A, Fang X, Kaslow D C, Miller L H. A family of erythrocyte binding proteins of malaria parasites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7085–7089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anders R A, Crewther P E, Edwards S, Margetts M, Matthew M L S M, Pollock B, Pye D. Immunization with recombinant AMA-1 protects mice against infection with Plasmodium chabaudi. Vaccine. 1997;16:240–247. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)88331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baruch D I, Ma X C, Singh H B, Bi X, Pasloske B L, Howard R J. Identification of a region of PfEMP1 that mediates adherence of Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocytes to CD36: conserved function with variant sequence. Blood. 1997;90:3766–3775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black C G, Wang L, Hibbs A R, Werner E, Coppel R. Identification of the Plasmodium chabaudi homologue of merozoite surface proteins 4 and 5 of Plasmodium falciparum. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2075–2081. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2075-2081.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackman M J, Heidrich H-G, Donachie S, McBride J S, Holder A A. A single fragment of a malaria merozoite surface protein remains on the parasite during red cell invasion and is the target of invasion-inhibiting antibodies. J Exp Med. 1990;172:379–382. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns J M, Jr, Adeeku A K, Belk C C, Dunn P D. An unusual tryptophan-rich domain characterizes two secreted antigens of Plasmodium yoelii-infected erythrocytes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;110:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00252-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns J M, Jr, Adeeku E A, Dunn P D. Protective immunization with a novel membrane protein of Plasmodium yoelii-infected erythrocytes. Infect Immun. 1999;67:675–680. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.675-680.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burns J M, Jr, Daly T M, Vaidya A B, Long C A. The 3′ portion of the gene for a Plasmodium yoelii merozoite surface antigen encodes the epitope recognized by a protective monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:602–606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns J M, Jr, Dunn P D, Russo D M. Protective immunity against Plasmodium yoelii malaria induced by immunization with particulate blood-stage antigens. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3138–3145. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3138-3145.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns J M, Jr, Majarian W R, Young J F, Daly T M, Long C A. A protective monoclonal antibody recognizes an epitope in the C-terminal cysteine-rich domain in the precursor of the major merozoite surface antigen of the rodent malarial parasite Plasmodium yoelii. J Immunol. 1989;143:2670–2676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns J M, Jr, Scott J M, Carvalho E M, Russo D M, March C J, Van Ness K P, Reed S G. Characterization of a membrane antigen of Leishmania amazonensis that stimulates human immune responses. J Immunol. 1991;146:742–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chappel J A, Holder A A. Monoclonal antibodies that inhibit Plasmodium falciparum invasion in vitro recognize the first growth factor-like domain of merozoite surface protein-1. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;60:303–312. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90141-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crewther P E, Matthew M L S M, Flegg R H, Anders R. Protective immune responses to apical membrane antigen 1 of Plasmodium chabaudi involve recognition of strain-specific epitopes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3310–3317. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3310-3317.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daly T M, Long C A. Humoral response to a carboxyl-terminal region of the merozoite surface protein-1 plays a predominant role in controlling blood-stage infection in rodent malaria. J Immunol. 1995;155:236–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doolan D L, Hedstrom R C, Rogers W O, Charoenvit Y, Rogers M, de la Vega P, Hoffman S L. Identification and characterization of the protective hepatocyte erythrocyte protein 17 kDa gene of Plasmodium yoelii, homolog of Plasmodium falciparum exported protein 1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17861–17868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duffy P E, Kaslow D C. A novel malaria protein, Pfs28, and Pfs25 are genetically linked and synergistic as falciparum malaria transmission-blocking vaccines. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1109–1113. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.1109-1113.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engers H D, Godal T. Malaria vaccine development: current status. Parasitol Today. 1998;14:56–64. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eugui E M, Allison A C. Separation of erythrocytes infected with murine malaria parasites in metrizamide gradients. Parasitology. 1979;79:267–275. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000053348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerold P, Schofield L, Blackman M J, Holder A A, Schwarz R T. Structural analysis of the glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol membrane anchor of merozoite surface proteins-1 and -2 of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;75:131–143. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haldar K, Ferguson M A J, Cross G A M. Acylation of a Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface antigen via sn-1,2-diacyl glycerol. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:4969–4974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henikoff S. Unidirectional digestion with exonuclease III in DNA sequence analysis. Methods Enzymol. 1987;155:156–165. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)55014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodder A N, Crewther P E, Matthew M L, Reid G E, Moritz R L, Simpson R J, Anders R F. The disulfide bond structure of Plasmodium apical membrane antigen-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29446–29452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.29446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman S L, Miller L H. Perspectives on malaria vaccine development. In: Hoffman S L, editor. Malaria vaccine development: a multi-immune response approach. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holder A A. Preventing merozoite invasion of erythrocytes. In: Hoffman S L, editor. Malaria vaccine development: a multi-immune response approach. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 77–104. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holder A A, Freeman R R. Immunization against blood-stage rodent malaria using purified parasite antigens. Nature. 1981;294:361–364. doi: 10.1038/294361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones T R, Hoffman S L. Malaria vaccine development. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:303–310. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.3.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kappe S H I, Noe A R, Fraser T S, Blair P L, Adams J H. A family of chimeric erythrocyte binding proteins of malaria parasites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1230–1235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaslow D C, Quakyi I A, Syin C, Raum M G, Keister D B, Coligan J E, McCutchan T F, Miller L H. A vaccine candidate from the sexual stage of human malaria that contains EGF-like domains. Nature. 1988;333:74–76. doi: 10.1038/333074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kedzierski L, Black C G, Coppel R L. Characterization of the merozoite surface protein 4/5 gene of Plasmodium berghei and Plasmodium yoelii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;105:137–147. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kemp D J, Coppel R L, Anders R F. Repetitive proteins and genes of malaria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:181–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim B K L, Chitnis C E, Wasniowska K, Hadley T J, Miller L H. Receptor and ligand domains for invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Science. 1994;264:1941–1944. doi: 10.1126/science.8009226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lal A A, de la Cruz V F, Welsh J A, Charoenvit Y, Maloy W L, McCutchan T F. Structure of the gene encoding the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium yoelii. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:2937–2940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall V M, Silva A, Foley M, Cranmer S, Wang L, McColl D J, Kemp D J, Coppel R L. A second merozoite surface protein (MSP-4) of Plasmodium falciparum that contains an epidermal growth factor-like domain. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4460–4467. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4460-4467.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marshall V M, Wu T, Coppel R L. Close linkage of three merozoites surface proteins on chromosome 2 of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;94:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCutchan T F, de la Cruz V F, Good M F, Wellems T E. Antigenic diversity in Plasmodium falciparum. Prog Allergy. 1988;41:173–192. doi: 10.1159/000415223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKean P G, O'Dea K, Brown K N. Nucleotide sequence analysis and epitope mapping of the merozoite surface protein 1 from Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi AS. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;62:199–210. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90109-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgan W D, Birdsall B, Frenkiel T A, Gradwell M G, Burghaus P A, Syed S E H, Uthaipibull C, Holder A A, Feeney J. Solution structure of an EGF module pair from the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1. J Mol Biol. 1999;289:113–122. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheele G, Jacoby R. Conformational changes associated with proteolytic processing of presecretory proteins allow glutathione-catalyzed formation of native disulfide bonds. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:12277–12282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sedegah M, Hedstrom R, Hobart P, Hoffman S L. Protection against malaria by immunization with plasmid DNA encoding circumsporozoite protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9866–9870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas A W, Deans J A, Mitchell G H, Alderson T, Cohen S. The Fab fragments of monoclonal IgG to a merozoite surface antigen inhibit Plasmodium knowlesi invasion of erythrocytes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1984;13:187–199. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(84)90112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. Tropical Disease Research Thirteenth Programme report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1997. pp. 40–61. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhong H, Fan J Y, Yang S, Davidson E A. Cloning and characterization of the merozoite surface antigen 1 gene of Plasmodium berghei. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:994–999. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]