Abstract

The plasticity region of Helicobacter pylori strain J99 is a large chromosomal segment containing 33 strain-specific open reading frames (ORFs) with characteristics of a pathogenicity island. To study the diversity of the plasticity region, 22 probes corresponding to 20 ORFs inside the plasticity region and two ORFs on its boundaries were hybridized to genomic DNA isolated from clinical strains of H. pylori from patients with gastritis or gastric adenocarcinoma. Highly variable hybridization patterns were observed. The majority of the clinical strains presented a hybridization profile similar to that of J99; thus, these ORFs are not J99 strain specific. No association was found between a particular hybridization pattern and the clinical origin of the strain. Nevertheless, two single ORFs (JHP940 and JHP947) were more likely to be found in gastric cancer strains. They may be new pathogenicity markers. An in vitro expression study of these ORFs was also performed for the J99 strain, under different conditions. Thirteen ORFs were consistently expressed, six were consistently shut off, and three were expressed differentially. Most of the constitutionally expressed genes were located on the 3′ part of the plasticity region. Our results show that the plasticity region, rather than being considered a pathogenicity island per se, should be considered a genomic island, which represents a large fragment of foreign DNA integrated into the genome and not necessarily implicated in the pathogenic capacity of the strain.

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium which colonizes the gastric mucosa of humans (21). Chronic infection with this pathogen is strongly associated with an increased risk of different gastric diseases, ranging from chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer to two types of gastric cancer, adenocarcinoma and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (12, 13, 14, 17). Only a minimal percentage of infected subjects develop clinical disease. Environment-, host-, and strain-dependent factors could play a role in the evolution of the infection. Similarly to other bacterial pathogens which present pathogenic and nonpathogenic variants of the same species, such as uropathogenic (16, 28) and enteropathogenic (22) Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (11, 23), and highly pathogenic Yersinia species (4, 25), H. pylori strains isolated from patients suffering from the most severe gastric diseases possess a pathogenicity island in their genome named the cag pathogenicity island (1, 6, 7, 15, 19). The term “pathogenicity island” is used to indicate the presence of a large chromosomal segment (30 kb or more in size) containing a cluster of virulence genes and presenting several characteristics suggesting a possible origin by horizontal transfer from another bacterial species, such as a G+C content different from that of the rest of the genome, the presence of repeated sequences, and a possible insertion within tRNA genes (10, 11).

H. pylori is the first bacterium for which the genomes of two strains have been sequenced, allowing the determination of their complete variability. Genome sequence analysis of H. pylori 26695 (20, 29) and J99 (2, 9) strains indicates the presence of several regions of different G+C contents (eight and nine regions, respectively), some of which may represent potential pathogenicity islands. In both strains, one of these regions is indeed the cag pathogenicity island. Among these regions in both the J99 and 26695 strains, a large region of approximately 45 kb in J99 and 68 kb in 26695 (3 to 4% of the chromosome; G+C content, 35%) has been termed the “plasticity region” (2, 9). Comparison of these two genomes showed that this region included many of the strain-specific open reading frames (ORFs) (2). Indeed, among the 38 ORFs included in the J99 plasticity region (ranging from JHP914 to JHP951), 33 were not contained in H. pylori 26695. Although the ORFs of the major part of the plasticity region encode putative proteins with unknown function, some ORFs have been found to share similarity to genes encoding proteins involved in DNA replication (JHP919 and JHP931) as well as DNA restriction, modification, recombination, and repair systems (JHP941 and JHP951).

This study had three principal purposes: (i) to analyze the diversity of the plasticity zone in geographically similar strains to determine whether the apparent variability is an artifact of comparing only the two sequenced strains, (ii) to determine if the plasticity zone is a true pathogenicity island or just a cluster of genes (some of which may play a role in pathogenesis) and to determine if the presence of any particular gene correlates with disease, and (iii) to study the expression of selected ORFs found in this region to determine whether the plasticity zone contains true genes or rather pseudogenes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical samples, bacterial strains, and culture.

Forty-three H. pylori strains were isolated from gastric biopsy specimens obtained from patients suffering from gastric carcinoma (17 patients) and patients with chronic gastritis-associated dyspepsia (26 patients) at Max Peralta and Calderón Guardia Hospitals in Costa Rica. All gastric biopsy specimens were ground in brucella broth (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) and cultured on three media: Columbia agar (Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-la-Coquette, France), supplemented with 5% sheep blood without antibiotics; Pylori agar (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France); and an in-house medium made of Wilkins-Chalgren agar (Oxoid Unipath, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) supplemented with 10% human blood and antibiotics (vancomycin, 10 mg/liter; cefsulodin, 5 mg/liter; trimethoprim, 5 mg/liter; and cycloheximide, 100 mg/liter). Incubation was performed at 37°C for up to 12 days in a microaerobic atmosphere generated using Gaspaks (Oxoid Unipath) in jars. Identification was based on morphology on Gram staining and the presence of oxidase, catalase, and urease activities.

Four H. pylori reference strains were included in this study: the two H. pylori strains whose genomes have been sequenced previously (2, 29) (access on the websites at http://scriabin.astrazeneca-boston.com/hpylori and http://www.tigr.org), strain J99, isolated from a patient with duodenal ulcer, and strain 26695 (NCTC 12455), isolated from a gastritis patient; strain SS1, a strain adapted to mouse infection (18); and strain CCUG 17874 (identical to strain NCTC 11638) (5).

For extraction of total DNA, each H. pylori isolate was subcultured on one in-house plate for 48 to 72 h. The cells were harvested in 1 ml of brucella broth and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 15 min, and the pellets were stored at −80°C for further studies.

For extraction of total RNA, strain J99 was grown for 24 and 48 h in solid and liquid media (brucella broth containing 10% fetal bovine serum and four antibiotics [vancomycin, 10 mg/liter; cefsulodin, 5 mg/liter; trimethoprim, 5 mg/liter; and cycloheximide, 100 mg/liter]).

Preparation of genomic DNA.

The DNA of H. pylori culture was extracted using the standard phenol-chloroform procedure. Briefly, the pellets of bacteria, stored at −80°C, were resuspended in 1 ml of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 1 mM EDTA). They were then treated successively with sodium dodecyl sulfate (1%) and proteinase K (0.1 g/liter). Proteins were eliminated by solvent extraction (twice with phenol and once with chloroform). DNA was precipitated with 70% ethanol and 0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 4.8) at −20°C overnight. The DNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol, dried, resuspended in sterile water, and stored at −20°C. The DNA concentration was determined as optical density at 260 nm.

Plasticity region probe design.

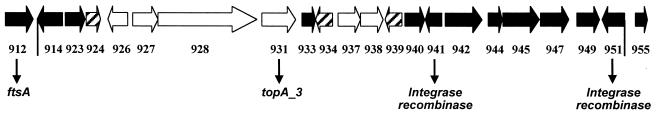

The plasticity region of strain J99 is a large region of chromosomal DNA ranging from nucleotides 1012093 to 1057038, which contains 38 ORFs (from JHP914 to JHP951) (Fig. 1). The genes from this strain were chosen as the reference because they were obtained from a patient with severe gastroduodenal disease and therefore would increase the chance of identifying a virulence gene. The presence of plasticity region ORFs was analyzed by dot blot hybridization. Twenty ORFs inside the plasticity region as well as two ORFs outside (JHP912 and JHP955) encoding potential proteins of more than 250 amino acids were selected. A specific ORF of the 26695 strain chromosome (HP986) was also included in our analysis. For each ORF, a specific DNA fragment was selected in silico for probe design. The probe sequences were compared to J99 and 26695 genome sequences in order to evaluate the scores using the http://scriabin.astrazeneca-boston.com/hpylori website with the WU-Blast 1-4 program (3).

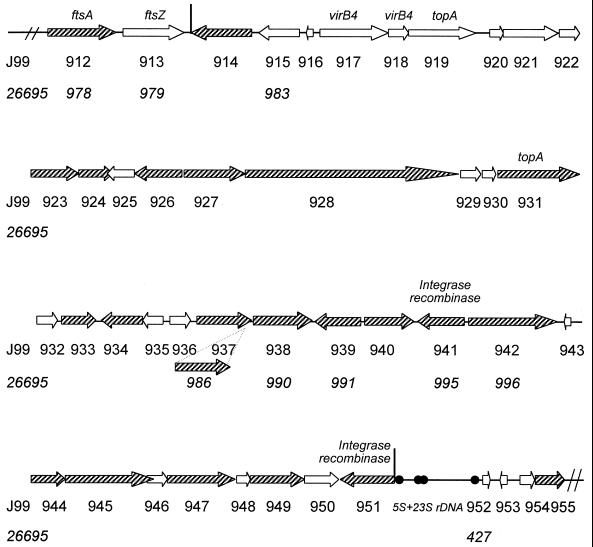

FIG. 1.

Map of the plasticity locus and flanking regions of the H. pylori J99 strain. Vertical lines indicate the estimated boundaries of the plasticity region. The ORFs of the J99 strain, indicated by the prefix JHP, are indicated by arrows and numbered sequentially, below the arrows; the corresponding homologous gene, if it exists in strain 26695, is indicated with numbers (preceded by the prefix HP) below the number of the J99 ORF. The shaded arrows show the ORFs for which DNA fragments were used as probes in hybridization assays and for which an expression study was performed (except HP986, which is not present in strain J99). The ORFs for which orthologous genes were found are indicated by the gene name (9): JHP912/HP978, similar to the ftsA gene encoding the septum formation protein in E. coli (GenBank accession no. X02821); JHP913/HP979, similar to the ftsZ gene encoding a putative GTPase involved in circumferential ring formation in E. coli (GenBank accession no. X55034); JHP917 and JHP918, similar to the virB4 gene of Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GenBank accession no. X53264); JHP919 and JHP931, which encode a putative topoisomerase I protein (topA_3); and JHP941 and JHP951, encoding putative integrase-recombinase proteins (XerCD family).

Amplification of DNA by PCR.

Oligonucleotide primers were derived from the sequence of specific ORFs from the plasticity region (Table 1) and synthesized by Isoprim (Toulouse, France). PCR conditions were optimized using the reference strains J99 and 26695. PCR amplification was performed under a final volume of 50 μl containing 10 ng of H. pylori DNA, 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer (670 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.8], 160 mM [NH4]2SO4, 0.1% Tween 20), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 μM (each) primer, 1 U of Eurobiotaq DNA polymerase (Eurobio, Les Ulis, France), and 200 μM (each) four deoxynucleotides (Eurobio). The cycling programs, preceded by 5 min at 94°C, consisted of 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 62°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final elongation step at 72°C for 7 min, and were performed using an automatic thermal cycler (9700; Perkin-Elmer Corp., Norwalk, Conn.).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in PCRs

| ORF | Nucleotide positions in each ORF | Sequence (5′→3′) | Expected product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| JHP912/HP978a | 156–176 | CAA TAG CCT TGC TCA CGC TTC | 624 |

| 779–759 | GTT AAA TGG TGA GAG CCT ACG | ||

| JHP914 | 710–730 | CCT TAT TGG TGT TAG CTA GAG | 517 |

| 1226–1208 | CCT TGT GCC AAA GCG TTA G | ||

| JHP923 | 3–24 | GGC TAA AAC AGA AAC GGA TAA C | 368 |

| 370–349 | CAC GGC TAT TGA TAG GAT TAT C | ||

| JHP924 | 19–37 | CTC TTA GAG CAT AAG ATC G | 402 |

| 420–403 | GCT GCT AAT ACG AGA CGC | ||

| JHP926 | 25–45 | GAT GAG CAA ATC AAT GGC ATG | 991 |

| 1015–995 | ACC TTT CAA TAC CGC TAG AAG | ||

| JHP927 | 81–99 | CCA CTC TAA AGG ACT ACA C | 1,191 |

| 1271–1253 | GCT TGA ATG ATT GCT GCA C | ||

| JHP928 | 4742–4761 | GCA CGC CTA TAG CTA ATT CC | 1,543 |

| 6284–6264 | AGC TTG ATC TCT GTA TGA GTG | ||

| JHP931 | 824–844 | GTA TTA GCG AAG TGC AAT CAC | 1,133 |

| 1956–1936 | GCT AAT TTG TTT AGG CGT AGC | ||

| JHP933 | 26–43 | GAG TGA GTT TAA GCG AAC | 708 |

| 733–716 | CTT GTT GCT CTT GCA AGG | ||

| JHP934 | 73–92 | CTA AAA CAA GAG CCT AGC AC | 941 |

| 1013–994 | CCC TTG CTC TCT AAA ATC TC | ||

| JHP937 | 25–44 | GGT ATG TTT GTT GAG CCA TC | 1,067 |

| 1091–1072 | CTC TGA TAG GCT TGC TTA AC | ||

| HP986 | 21–39 | GCA TGT CCC AAA TCG TAG G | 566 |

| 586–568 | TGC ATT TCG CAT TGG CTC C | ||

| JHP938/HP990a | 835–853 | GAG ACA GGT AAA TGC GAC C | 397 |

| 1231–1213 | TGG GAA AGC CAA ATT GGT C | ||

| JHP939/HP991a | 433–451 | CAA CTT CAA ACC ATG CTT G | 528 |

| 960–942 | GGT AGT GTT GTC ATA GGA C | ||

| JHP940 | 139–158 | GAA ATG TCC TAT ACC AAT GG | 591 |

| 729–711 | CCT AAG TAG TGC ATC AAG G | ||

| JHP941/HP995a | 3–24 | GCA TGA GCA ATG TTC TAT AAG C | 292 |

| 294–273 | CAT CAC ATA CTT AGC CAT CTT G | ||

| JHP942/HP996a | 281–303 | GTG AAA CAG CTT ACA ATG AAA TG | 1,191 |

| 1471–1451 | GCT TAC TCA CTA GCT CAT AAG | ||

| JHP944 | 407–427 | CTA TGA GTG AAG AAT TAA CGC | 358 |

| 764–744 | CGC TCC ATT CCA ATA TCT TTG | ||

| JHP945 | 246–265 | CAA TGC GAC TAA CAG CAT AG | 1,028 |

| 1273–1254 | CGC ATT TGC TGT CAT CTT TG | ||

| JHP947 | 91–109 | GAT AAT CCT ACG CAG AAC G | 611 |

| 701–682 | GCT AAA GTC ATT TGG CTG TC | ||

| JHP949 | 70–87 | GGA GTG GGT GCT TAC TTG | 465 |

| 534–517 | GAT ACT GTG GTG CGT GTC | ||

| JHP951 | (−)9–11 | GGG AGA AAG ATG AGT GAT TG | 362 |

| 353–335 | GCC ATA GAG CTT GGT TTC C | ||

| JHP955 | 218–236 | GCC AGC AAC GAT TGG CTA C | 425 |

| 642–622 | CTT ATG CGC TAC AAA ATG CAG | ||

| JHP rrn16Sb | 261–285/5599–5623 | GTG CTT ATT CGT TAG ATA CCG TCA T | 399 |

| 659–635/5997–5973 | CTA GCA AGC TAG AAG CTT CAT CGT T | ||

| JHP495-1c | 157–177 | GAT AAC AGG CAA GCT TTT GAG GGA | 394 |

| 550–528 | CCA TGA ATT TTT GAT CCG TTC GG | ||

| JHP495-2c | 2551–2571 | ACC CTA GTC GGT AAT GGG TTA | 595 |

| 3145–3124 | GGC TGT TAG TAG CGT AAT TGT C |

The sequences of these primers were derived from comparison of the two ORFs present in the genomes of both H. pylori strains, J99 (JHP) and 26695 (HP).

These primers were used for amplification of a DNA fragment of the 16S ribosomal DNA gene. The primer positions are based upon the two sequences of JHP rrn16S of H. pylori strain J99.

Two pairs of primers were used to obtain two fragments in ORF JHP495, corresponding to the cagA gene.

The amplified products of the J99 strain were used as probes in the hybridization experiments. They were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide, and the appropriate fragment was cut out of the gel and purified using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) before labeling with the ECL Direct Nucleic Acid Labeling and Detection System according to the conditions specified by the supplier (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Orsay, France).

Southern blot.

Total DNA (2 μg) of the J99 strain was digested overnight with BglII and HindIII restriction endonucleases according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France). DNA fragments were separated on a 0.8% agarose gel at 45 V for 14 h and transferred to a Hybond-N+ nucleic transfer membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) (26). The membranes were hybridized at 42°C overnight in plastic bags containing ECL Gold hybridization buffer supplemented with 5% (wt/vol) blocking agent and 0.5 M NaCl. The membranes were washed twice in primary washing buffer (0.5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate] [pH 7.0], 0.4% sodium dodecyl sulfate) at 50°C for 10 min and twice in secondary washing buffer (2× SSC) at room temperature for 5 min. Finally, the membranes were exposed to Hyperfilm ECL film (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) for 1 to 2 h.

Dot blot.

For each single dot, 200 ng of total DNA was resuspended in 100 μl of TE buffer and mixed with 100 μl of a denaturing buffer (0.8 N NaOH; 1.5 M NaCl). The denatured DNA was transferred to a Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) by means of a Bio-Rad dot blot 96-well filtration system apparatus (Bio-Rad, Ivry-sur-Seine, France). A DNA fragment corresponding to the 16S rRNA gene was used as the hybridization control. DNA samples from the reference strains J99 and 26695 were spotted on each membrane, as control. Hybridization was performed as described above.

RNA extraction.

H. pylori cells were harvested in 1 ml of brucella broth to obtain an opacity equivalent to the McFarland 2 opacity standard (corresponding to 109 CFU/ml for the 24-h culture and 108 CFU/ml for the 48-h culture), centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min, and washed with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.6). Total RNA was extracted using a High Pure RNA Isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the recommendations of the manufacturer.

Reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR).

Total RNA (500 ng) was reverse transcribed in cDNA using the Enhanced Avian RT-PCR Kit (Sigma Aldrich, St. Quentin Fallavier, France) in a total volume of 20 μl containing 2 μl of 10× RT buffer (500 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3; 400 mM KCl; 80 mM MgCl2; 10 mM dithiothreitol), 20 U of RNase inhibitor, 0.5 mM deoxynucleotide mix, 20 U of enhanced avian myeloblastosis virus RT, and 6.25 μM random nanomers (Sigma Aldrich). As a control, RNA corresponding to one fragment of the 16S rRNA genes (JHP rrn16S) and two fragments of the cagA gene (JHP495) (one at the beginning and one at the end) was detected using either a nonamer mixture (at 6.25 μM) or a specific primer (at 1 μM) (Table 1).

PCR amplification was carried out in a total volume of 25 μl containing 2.5 μl of cDNA product, 2.5 μl of 10× PCR buffer (500 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.3; 150 mM ammonium sulfate; 25 mM MgCl2; 1% Tween 20), 25 μM deoxynucleotide mix, 1.25 U of AccuTaq DNA polymerase (Sigma Aldrich), and 1 μM (each) primer. In order to verify whether DNA contamination was present, a control amplification of RNA was performed. The primers and the cycling programs used for PCR amplification of the plasticity region ORFs were the same as those used for obtaining probes (Table 1). Twelve microliters of each amplified sample was analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis with 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide per ml.

Dendrogram construction.

Each strain was assigned to a profile based on a positive or negative hybridization. The distance between the different profiles (combination of bands) was measured by calculating the Dice coefficient [(2 × the number of pairs of characteristics in common)/total number of characteristics in the two profiles] (8). In this calculation, only positive characteristics are taken into consideration. The Dice coefficient was used in the UPGMA formula (unweighted pair group method with averages) to assign levels of hierarchy in the similarity of profiles (27): d (i, jk) = [Mj · d(i,j) + Mk · d(i,k)]/(Mj + Mk). The distance (d) between two clusters was measured as a function of the number of individuals in the cluster (M). In this model, i is a given individual (profile or cluster of profiles) and jk is the cluster to which i is being compared, j being the last member added to the cluster and k being the initial or previous component (profile or cluster of profiles). By using the levels of hierarchy assigned by this model, a dendrogram was constructed to illustrate the relationship between the profiles.

Statistical analysis.

The proportion of each ORF or each profile was compared between strains isolated from patients with gastric adenocarcinoma and strains isolated from patients with chronic gastritis-associated dyspepsia using the χ2 test. Yates' corrected χ2 was applied because of the small sample size and an expected value of <5.

RESULTS

Defining the specificity of hybridization analysis.

Two criteria were used to select the ORFs of the plasticity region targeted in this study: (i) their size (more than 250 codons) and (ii) minimal homology to other parts of the H. pylori chromosome (in order to ensure specificity for plasticity region ORFs). Twenty-two ORFs were then selected for further analysis, 20 ORFs within the plasticity region and 2 outside, in the flanking regions (JHP912/HP978 and JHP955) (Fig. 1).

To ensure that the probes hybridized only with ORFs of the plasticity region of J99 and/or 26695 DNA in our experimental conditions, dot blot hybridizations of each probe with J99 and 26695 DNAs were analyzed first. As expected on the basis of the genome sequences, each probe hybridized with DNA of the reference strains. As an example, the hybridization patterns obtained using different probes are shown in Fig. 2A. All the probes hybridized with their corresponding PCR fragment, as expected. The probes corresponding to the ORFs JHP914, JHP923, and JHP931, which are J99 strain specific, hybridized only with J99 DNA. The probe corresponding to HP986, a 26695 strain-specific ORF, gave a positive result only with the 26695 DNA, and the probes corresponding to JHP939/HP991 and JHP941/HP995, ORFs which are present in both the J99 and the 26695 chromosomes, hybridized with the DNA of both strains.

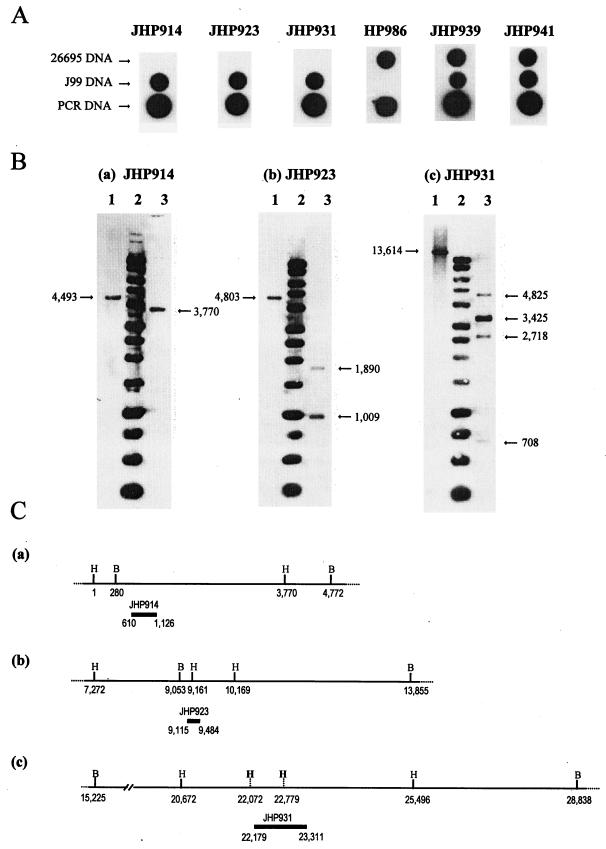

FIG. 2.

Determination of probe specificity. (A) Dot blot hybridization of six probes corresponding to JHP914, JHP923, and JHP931 (J99 specific-strain ORFs); HP986 (26695 specific-strain ORF); JHP939/HP991; and JHP941/HP995 (present in genomes of both J99 and 26295) with DNA extracted from J99 and 26695 and the corresponding PCR product before labeling. (B) Southern blot hybridization analysis of J99 DNA digested with BglII and HindIII. The probes corresponded to ORFs JHP914 (a), JHP923 (b), and JHP931 (c). Lane 1, J99 DNA digested with BglII; lane 2, 1-kb DNA ladder (Promega, Charbonnieres, France); lane 3, J99 DNA digested with HindIII. Sizes are indicated in base pairs. (C) Restriction map of J99 DNA in regions surrounding the JHP914 (a), JHP923 (b), and JHP931 (c) probes. The position of each probe is indicated (black boxes), and putative undigested HindIII sites are also shown (vertical dotted lines). Position 1 has been arbitrarily assigned to nucleotide 1011491 of the J99 strain genome.

We have also looked for the possibility of a nonspecific hybridization due to the presence of sequences similar to our probes elsewhere in the genome. Thus, we compared each probe sequence against the genome sequence databases for the J99 and 26695 H. pylori strains. From this analysis, a list of high-scoring segment pairs was obtained. A score was assigned to each sequence comparison, depending on three criteria: the percentage of nucleotide identity, the size of the sequence query, and the ratio between this size and that of the database sequence. Thus, the score allows us to estimate the risk of a potential hybridization. In comparing the sequence of each probe with the sequence of J99 DNA, all the probes were associated with their own homologous sequences and partial homology with other DNA fragments was found, with maximal scores ranging from 87 to 241. To determine the threshold for negative hybridization, the probes with the highest scores, JHP914 (score of 174), JHP923 (score of 241), and JHP931 (score of 173), were used in Southern blot hybridization. Figure 2B shows the hybridization pattern for these three probes. As expected from the restriction map (Fig. 2C, subpanel a), the JHP914 probe revealed only a BglII fragment of 4,493 bp and a HindIII fragment of 3,770 bp (Fig. 2B, subpanel a). Similarly, a 4,803-bp BglII fragment hybridized with the JHP923 probe. Two HindIII fragments of 1,890 and 1,009 bp were revealed by the probe as expected from the positions of the HindIII sites (Fig. 2B, subpanel b, and 2C, subpanel b). According to the restriction map (Fig. 2C, subpanel c), a 13,614-bp BglII fragment hybridized with the JHP931 probe. When digested by HindIII, the DNA hybridized with four fragments. Hybridization of two of these fragments was probably due to partial digestion (compare Fig. 2B, subpanel c, and 2C, subpanel c). These results indicate that the probes hybridized specifically with the plasticity region ORFs and not with sequences elsewhere in the genome.

Distribution of selected ORFs within the plasticity region.

Since the selected probes hybridized specifically to J99 and/or 26695 DNA, we examined which probes reacted with each isolate in the strain collection including 43 clinical isolates and the H. pylori reference strains SS1 and CCUG 17874. Each strain was assigned to a pattern based on a positive or negative hybridization (Fig. 3).

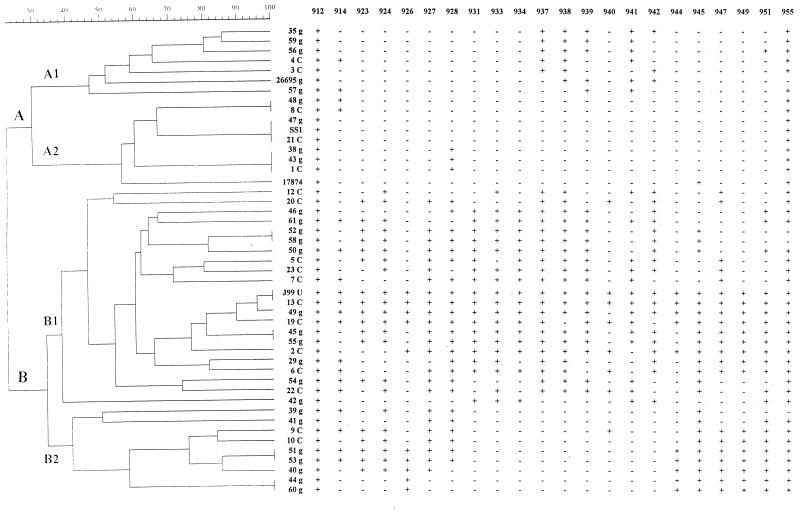

FIG. 3.

Distribution of plasticity region ORFs within the H. pylori strain collection. The dendrogram constructed with the hybridization pattern determined for each strain is presented at the left of the figure. At the right, the hybridization patterns for clinical strains (patterns indicated positive [+] or negative [−] hybridization with each probe) are presented. The different probes and the name of each strain are indicated (g, strain isolated from patient with gastritis; C, strain isolated from patient with gastric adenocarcinoma; U, strain isolated from patient with peptic ulcer).

In order to compare the patterns of the strains, a dendrogram was constructed using the UPGMA method. Thirty-seven different patterns were obtained, indicating high variability (Fig. 3). There were two groups of three strains that exhibited the same pattern: strains 47g, SS1, and 21C and strains 38g, 43g, and 1C. In addition, there were six pairs of isolates (48g-8C, 52g-58g, J99-13C, 45g-55g, 51g-53g, and 44g-60g) that demonstrated similar gene content patterns (Fig. 3). Moreover, the strains could be classified into two clusters, depending on the number of probes for which a positive hybridization signal was obtained. The first cluster, identified as cluster A (Fig. 3), was comprised of the 13 clinical strains (30.2%) which contained less than seven ORFs in the plasticity region, and the second, cluster B, included 30 clinical strains (69.8%) carrying seven or more of the selected ORFs. Thus, the majority of the clinical strains presented a profile similar to that of the J99 strain (cluster B), the reference strains 26695, SS1, and 17874 having a cluster A profile (Table 2). Within cluster A, two subgroups, or branches, could also be observed. Branch A1 includes six strains (13.9%) containing ORFs located in the center of the plasticity region (from JHP937 to JHP942), whereas branch A2 (16.3%) contains either strains with a positive hybridization to only one plasticity region ORF (two cases in JHP914, three cases in JHP928, and one case in JHP945) or strains that lacked any of the J99 plasticity region ORFs (three cases) (Fig. 3). Strains belonging to cluster B could also be subdivided into two branches. Branch B1 includes 21 strains (48.8%) with 7 to 20 plasticity region ORFs dispersed along the plasticity locus, whereas branch B2 has nine strains (20.9%) possessing only the ORFs located at the two ends of the plasticity region (without ORFs from JHP931 to JHP942). Figure 4 shows the percentage of strains hybridizing with each ORF. The distribution was diverse. Probes JHP912 and JHP955, which are outside the plasticity region, were found in 100 and 93% of the strains, respectively. The percentage of positive strains for the other probes ranged from 16.3% (7 of 43, JHP940) to 60.5% (26 of 43, JHP928).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of clinical H. pylori strains among the different hybridization patterns

| Pattern typea | Clinical strains (n = 43)

|

Strains from patients with gastritis (n = 26)

|

Strains from patients with cancer (n = 17)

|

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Cluster A | 13 | 30.2 | 8 | 30.8 | 5 | 29.4 | 0.92 |

| Branch A1 | 6 | 13.9 | 4 | 15.4 | 2 | 11.8 | 0.9 |

| Branch A2 | 7 | 16.3 | 4 | 15.4 | 3 | 17.6 | 0.8 |

| Cluster B | 30 | 69.8 | 18 | 69.2 | 12 | 70.6 | 0.92 |

| Branch B1 | 21 | 48.8 | 11 | 42.3 | 10 | 58.8 | 0.3 |

| Branch B2 | 9 | 20.9 | 7 | 26.9 | 2 | 11.7 | 0.4 |

The patterns were classed using a dendrogram. Cluster A includes strains which contain less than seven plasticity region ORFs and is subdivided into two branches, A1, which contains the ORFs located in the center of the plasticity region (from JHP937 to JHP942), and A2, which includes strains with one ORF or none. Cluster B includes strains carrying seven or more selected ORFs and is subdivided into two branches, B1, in which these ORFs are dispersed throughout the genome, and B2, where the ORFs are located in the central part of the plasticity region (see also Fig. 3).

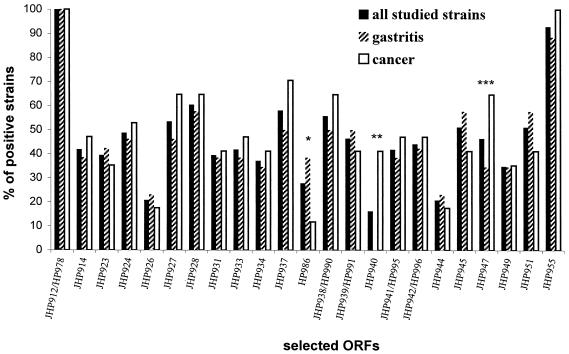

FIG. 4.

Percentage of clinical strains hybridizing with plasticity region ORFs. Each bar represents the percentage of positive strains, in dot blot experiments, for a given ORF, based either on all strains studied (n = 43) or on strains isolated from patients suffering from gastric carcinoma (n = 17) and from gastritis only (n = 26). The P value is indicated when ≤0.08 (∗, P = 0.08; ∗∗, P = 0.0006; ∗∗∗, P = 0.05).

The distribution of the plasticity region ORFs was analyzed in regard to the clinical disease of the patients from whom the strains were isolated (gastric cancer or chronic gastritis-associated dyspepsia). Based on the hybridization patterns, no significant differences between the ORFs present in the strains isolated from patients with chronic gastritis-associated dyspepsia and those in strains isolated from patients with gastric cancer were observed (Fig. 3 and Table 2). Indeed, in both groups, the most widely represented pattern was cluster B (69.2 versus 70.6%, respectively), with no significant difference (P = 0.92) (Table 2). The same analysis was performed to determine the percentage of strains hybridizing with the selected ORFs (Fig. 4). Two probes showed a distribution significantly different between the two disease classes: the JHP940 ORF was present in seven strains (41.2%) isolated from patients with cancer and from none of the strains isolated from patients with gastritis (P = 0.0006), and JHP947 was found more frequently in strains from cancer patients (64.7%) than in strains from patients with gastritis (34.6%) (P = 0.05). A trend, while not statistically significant, was also observed (P = 0.08) for the HP986 ORF, which is specific for the 26695 strain (11.8 versus 38.5%, respectively) (Fig. 4).

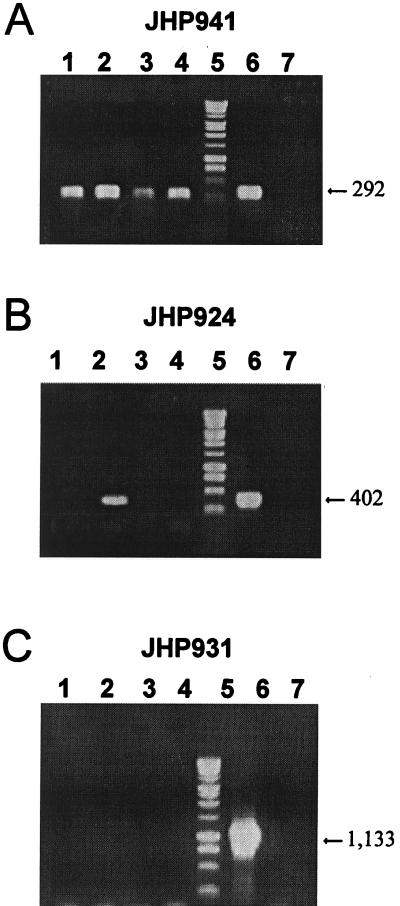

Study of the expression of selected ORFs within the plasticity region in the J99 strain.

To identify the J99 plasticity region ORFs that were expressed, total RNA of the J99 strain was reverse transcribed into cDNA using random primers and PCR amplification was performed using specific primers. Initially, we verified that random primers were able to produce a “representative” cDNA. Two RT-PCRs were performed using random nanomers or primers specific for either the 16S rRNA gene or the cagA gene. Identical results were obtained independently of the primers used to generate the cDNA (data not shown). Thus, the 22 selected ORFs of the plasticity region were analyzed by RT-PCR using random nanomer-generated cDNA. The results for three ORFs are presented in Fig. 5 as an example. The JHP941 ORF was found to be expressed regardless of the growth conditions tested. Indeed, a 292-bp fragment was revealed under all conditions (Fig. 5A, lanes 1 to 4). In contrast, the JHP931 ORF was not obtained under any of the conditions tested (Fig. 5C, lanes 1 to 4). Three ORFs were found to be differentially expressed according to the growth conditions. As an example, the results for JHP924 are shown in Fig. 5B. This ORF was expressed in only one condition among the four tested (24 h, liquid medium [lane 2]). In all experiments, we confirmed the absence of contaminating DNA in the RNA preparation by performing a PCR without a reverse transcription step. In no case was an amplification product obtained (data not shown). In summary, three groups of ORFs were defined: 13 (JHP912, JHP914, JHP923, JHP933, JHP940, JHP941, JHP942, JHP944, JHP945, JHP947, JHP949, JHP951, and JHP955) that were expressed under all growth conditions tested, 6 that were never expressed under the conditions tested (JHP926, JHP927, JHP928, JHP931, JHP937, and JHP938), and 3 that were differentially expressed (JHP924, JHP934, and JHP939) depending on the growth conditions (Fig. 6). Expression of the JHP924 or JHP939 ORF was detected only at 24 h in either liquid medium or solid medium, respectively. Expression of the JHP934 ORF was detected after 24 h in liquid medium and after 48 h in solid medium. Among the expressed ORFs, JHP912, JHP941, and JHP951 showed similarity with genes in other bacteria (2). JHP912 has been found to be orthologous to the ftsA gene of E. coli, which encodes a septum formation protein. The two others are homologous to integrase-recombinase genes (xerCD family). Among the nonexpressed genes, JHP931 encodes a putative DNA topoisomerase I (topA_3 gene). The three ORFs that are differentially expressed currently have no orthologs in other bacterial sequences and therefore can be considered H. pylori specific.

FIG. 5.

Expression study of JHP941 (A), JHP924 (B), and JHP931 (C) ORFs in strain J99 by RT-PCR under different growth conditions. RNA was extracted after culture in solid (lanes 1 and 3) or liquid (lanes 2 and 4) medium for 24 h (lanes 1 and 2) or 48 h (lanes 3 and 4). Lane 5, 1-kb DNA ladder (Promega); lane 6, J99 DNA; lane 7, water. The sizes are indicated in base pairs.

FIG. 6.

Linear distribution of expressed and nonexpressed selected ORFs of the plasticity region of strain J99. The black arrows represent ORFs expressed whatever the growth conditions, shaded arrows represent differentially expressed ORFs, and white arrows are ORFs not expressed under the four conditions tested. The expression study was performed using RT-PCR of J99 strain RNA extracted from cells cultured under different growth conditions. The ORFs for which orthologous genes have been found are indicated by gene names below arrows (9). The vertical lines indicate the limits of the plasticity region (JHP914 to JHP951).

DISCUSSION

The plasticity region is a recently described locus in the chromosome of H. pylori J99 and 26695 that displays some characteristics of a pathogenicity island (2, 9, 10), i.e., a large size (45 or 68 kb, respectively), the presence of putative virulence genes (JHP917 and JHP918 vir homologs), and a G+C content lower (35%) than that of the rest of the genome (39%), suggesting its possible acquisition by horizontal gene transfer. In H. pylori J99, this region contains many ORFs which were considered to be J99 strain specific (33 of 38) because they were found in the J99 genome only (2, 9), and not in the genome of the first H. pylori strain sequenced, 26695 (29).

In this study, we show, for the first time, that 20 selected plasticity region ORFs may also be present in other H. pylori strains. This is an important point, because among these genes, 16 were previously classed as J99 specific based solely on the comparison between the J99 and 26695 strains. Furthermore, the ends of the plasticity zone were defined only by the comparison of these two strains, and they were therefore not precise. Indeed, the 5′ boundary of the plasticity zone had been placed by Doig et al. (9) at the 3′ end of the JHP914 gene (Fig. 1) but could have been placed elsewhere, i.e., at the 3′ end of the JHP916 gene, since the JHP915 gene was found in both strain J99 and strain 26695 (HP983 [Fig. 1]). However, in our study, the JHP914 gene was found in 18 of 43 clinical strains whereas the JHP912/HP978 gene was found conserved in all tested strains (Fig. 3). The 5′ end of the plasticity region was therefore confirmed to be at the 3′ end of the JHP914 gene. Concerning the other end (at the 5′ end of the JHP951 gene [Fig. 1]), the locus had been considered to extend to the JHP962 gene (2). However, this would then require the inclusion of the 5S-23S rRNA locus, a large region of conserved DNA. The hybridization of the JHP955 gene, located outside the plasticity region, showed that only 3 of 43 strains lacked this gene, in comparison to the JHP951 gene, which displayed greater diversity (Fig. 3). Finally, the acquisition of more information pertaining to other strains helped us to define the boundaries of the plasticity zone further, i.e., the 3′ end of the JHP914 gene and the 5′ end of the JHP951 gene. In strain J99, no sequences such as insertion sequence elements, transposons, and inverted repeat elements that could explain the origin of the plasticity zone were found. However, there are no data concerning the clinical strains because none of the nucleotide sequences have been determined.

The presence of 20 ORFs in a large group of clinical strains (n = 43) and in two reference strains (CCUG 17874 and SS1) was analyzed by dot blot hybridization. An in vitro expression study of these ORFs was also performed with the J99 strain.

Because most of the ORFs of the J99 plasticity region were not detected in 26695, PCR amplification was not considered an adequate method for their detection. With only one genome as a basis on which to design primers, together with the known divergence from orthologous genes (which is actually higher in genes of unknown function), the lack of a PCR product could easily be misinterpreted as the absence of a gene, while being due to differences in the primer-binding sequences. For this reason, hybridization seems to be a more accurate method, especially if it is possible to distinguish between paralogs, as demonstrated in this study. However, given the high cost of the chip technology, the traditional approach remains valuable when testing a small number of ORFs on a large number of strains. Our first criterion for the selection of ORFs included in this analysis was the size. We hypothesized that ORFs potentially encoding proteins of more than 250 amino acids are more likely to be real genes, with the smaller ORFs possibly being pseudogenes. The probes used were selected and hybridized specifically with the DNA corresponding to ORFs present in J99 and/or 26695. Moreover, the probes used were more than 300 nucleotides in length, which limited the possibility of a false-negative result due to interstrain variation. Hybridization results performed with two probes corresponding to the JHP917 and JHP919 ORFs were not considered because the DNA of the 26695 strain slightly hybridized with these probes although they were considered J99 strain specific (data not shown). The JHP917 and JHP919 proteins are VirB4 and TopA homologs, and both H. pylori J99 and 26695 contain other homologs in these protein classes.

The genetic variability of the clinical strains included in this study could have been predicted to be limited because they were isolated from patients living in the same geographic area. In contrast, however, a highly variable pattern of this locus was found by hybridization with the specific J99 plasticity region probes. Thus, we have confirmed the concept of genome plasticity at a particular locus.

The dendrogram obtained by comparing the hybridization patterns (Fig. 3) shows that the distribution of the plasticity region ORFs is very different among the H. pylori strains tested, ranging from the presence of all or almost all ORFs, to the deletion of ORFs located in the central part of the plasticity locus, to the lack of most of these ORFs. Thus, the present results suggest that the plasticity region is really a “plastic” or unstable locus. Instability is another characteristic of pathogenicity islands (10). This observation is in agreement with the fact that certain genes in the plasticity region may be partially deleted during subculturing of the J99 strain, although the mechanism responsible for the deletion is unknown (R. Alm, unpublished result).

Since the probes were unique to individual genes, it cannot be ruled out that some of the detected genes could lie outside the plasticity region. Therefore, for a limited number of strains (n = 7) representative of each dendrogram group (A1, A2, B1, and B2 [Fig. 3]), we studied the genetic organization of the genes by using PCR. The experiments were designed to amplify DNA fragments between two primers located in two consecutive genes in strain J99 (data not shown). These preliminary results confirmed the linkage of the genes studied and their genetic organization within the plasticity region.

Expression studies show that most of the selected genes of the plasticity region are expressed and that they do not represent pseudogenes; thus, the plasticity zone is not merely a graveyard of unwanted DNA. The 3′ part of the plasticity region appears to be constitutively expressed (Fig. 6). A preliminary organizational analysis of the plasticity region suggests the possibility of the expression or absence of expression of some ORFs as operons, by being consecutive and oriented in the same direction, such as JHP927-JHP928-JHP931 and JHP942-JHP944-JHP945-JHP947-JHP949. It would be of interest to study the expression of this locus under different cell culture conditions and in animal models, including more strains, to confirm these preliminary results.

A characteristic which is intrinsic to a pathogenicity island is its presence only in pathogenic strains of a given species. We have not found an association between the severity of disease (gastric cancer versus chronic gastritis-associated dyspepsia) and a type of profile of these ORFs in the clinical isolates. Thus, based on these results, this locus cannot be considered a pathogenicity island per se.

Despite the fact that the cag island is considered to be a pathogenic island in H. pylori (1, 6), this region is not present only in H. pylori strains from patients with severe gastric diseases. Moreover, an association between this locus and strain pathogenicity has not been found in all studies (15, 19, 24).

Nevertheless, among all the ORFs of the plasticity region studied, two single ORFs (JHP940 and JHP947) were more likely to be found in gastric cancer strains. RT-PCR analysis showed that these genes were expressed in vitro in the J99 strain. The possibility remains that these ORFs are new markers of pathogenicity. However, the possible role of these ORFs should be investigated in a larger number of strains from different geographic areas and by sequencing and expression analysis.

Since the publication of genome sequences of pathogenic and nonpathogenic bacteria, the concept of the pathogenicity island has been revised. As illustrated by Hacker and Kaper (10), the presence of a pathogenicity island is a particular case of a more general event occurring in genome evolution: the acquisition of an extraneous genetic unit, termed a genomic island. These regions, when integrated into the genome, may confer a survival advantage on the bacteria in certain ecological niches, and for this reason they are in continuous recasting. Thus, the plasticity island could be considered more generally a genomic island because it contains many features suggesting its “alien” origin, while, based on our analysis, it is not possible to link the presence of this entire locus to increasing pathogenic properties.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the financial support of the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC), Villejuif (no. 9313); of the IRMAD (Institut de Recherche sur les Maladies de l'Appareil Digestif), Paris; and of the Conseil Régional d'Aquitaine, Bordeaux, France. A. Occhialini is a recipient of a fellowship from IRMAD. F. Garcia and R. Sierra are supported by research grants from the Universidad de Costa Rica (803-98-257) and from the Service Culturel et de Coopération Scientifique de l'Ambassade de France à San José, Costa Rica.

We thank Sonia Etenna for technical assistance and Kathryn Mayo (Laboratoire de Bactériologie—Université Bordeaux 2) for English corrections.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akopyants N S, Clifton S W, Kersulyte D, Crabtree J E, Youree B E, Reece C A, Bukanov N O, Drazek E S, Roe B A, Berg D E. Analyses of the cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:37–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alm R A, Ling L-S L, Moir D T, King B L, Brown E D, Doig P C, Smith D R, Noonan B, Guild B C, De Jonge B L, Carmel G, Tummino P J, Caruso A, Uria-Nickelsen M, Mills D M, Ives C, Gibson R, Merberg D, Mills S D, Jiang Q, Taylor D E, Vovis G F, Trust T J. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1999;397:176–180. doi: 10.1038/16495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Boguski M S, Gish W, Wootton J C. Issues in searching molecular sequences databases. Nat Genet. 1994;6:119–129. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchrieser C, Rusniok C, Frangeul L, Couve E, Billault A, Kunst F, Carniel E, Glaser P. The 102-kilobase pgm locus of Yersinia pestis: sequence analysis and comparison of selected regions among different Yersinia pestis and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis strains. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4851–4861. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4851-4861.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukanov N O, Berg D E. Ordered cosmid library and high-resolution physical-genetic map of Helicobacter pylori strain NCTC11638. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:509–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Censini S, Lange C, Xiang Z, Crabtree J E, Ghiara P, Borodovsky M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14648–14653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Covacci A, Falkow S, Berg D E, Rappuoli R. Did the inheritance of a pathogenicity island modify the virulence of Helicobacter pylori? Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:205–208. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dice L R. Measures of the amount of ecological association between species. Ecology. 1991;109:273–278. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doig P, De Jonge B L, Alm R A, Brown E D, Uria-Nickelsen M, Noonan B, Mills S D, Tummino P, Carmel G, Guild B C, Moir D T, Vovis G F, Trust T J. Helicobacter pylori physiology predicted from genomic comparison of two strains. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:675–707. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.3.675-707.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hacker J, Kaper J. The concept of pathogenicity islands. In: Kaper J B, Hacker J, editors. Pathogenicity islands and other mobile virulence elements. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hacker J, Blum-Oehler G, Mühldorfer I, Tschäpe H. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1089–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3101672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang J Q, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt R H. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori: views and expert opinions of an IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, France: IARC Monographs; 1994. pp. 177–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeno T, Ota H, Sugiyama A, Ishida K, Katsuyama T, Genta R M, Kawasaki S. Helicobacter pylori-induced chronic active gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and gastric ulcer in mongolian gerbils. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:951–960. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65343-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenks P J, Mégraud F, Labigne A. Clinical outcome after infection with Helicobacter pylori does not appear to be reliably predicted by the presence of any of the genes of the cag pathogenicity island. Gut. 1998;43:752–758. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.6.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kao J-S, Stucker D, Warren J W, Mobley H L. Pathogenicity island sequences of pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli CFT073 are associated with virulent uropathogenic strains. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2812–2820. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2812-2820.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuipers E J. Exploring the link between Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:3–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee A, O'Rourke J, De Ungria M C, Robertson B, Daskalopoulos G, Dixon M F. A standardized mouse model of Helicobacter pylori infection: introducing the Sydney strain. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1386–1397. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maeda S, Yoshida H, Ikenoue T, Ogura K, Kanai F, Kato N, Shiratori Y, Omata M. Structure of cag pathogenicity island in Japanese Helicobacter pylori isolates. Gut. 1999;44:336–341. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.3.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marais A, Mendz G L, Hazell S L, Mégraud F. Metabolism and genetics of Helicobacter pylori: the genome era. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:642–674. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.3.642-674.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall B J, Warren J R. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;i:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDaniel T K, Jarvis K G, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1664–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mills D M, Bajaj V, Lee C A. A 40 kb chromosomal fragment encoding Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes is absent from the corresponding region of the Escherichia coli K-12 chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:749–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan Z J, van der Hulst R W, Feller M, Xiao S D, Tytgat G N, Dankert J, van der Ende A. Equally high prevalences of infection with cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori in Chinese patients with peptic ulcer disease and those with chronic gastritis-associated dyspepsia. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1344–1347. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1344-1347.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rakin A, Noelting C, Schubert S, Heesemann J. Common and specific characteristics of the high-pathogenicity island of Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5265–5274. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5265-5274.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sneath P H-A, Sokat R R. Numerical taxonomy: the principles and practice of numerical classification. W. H. San Francisco, Calif: Freeman & Co.; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swenson D L, Bukanov N O, Berg D E, Welch R A. Two pathogenicity islands in uropathogenic Escherichia coli J96: cosmid cloning and sample sequencing. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3736–3743. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3736-3743.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomb J-F, White O, Kerlavage A R, Clayton R A, Sutton G G, Fleischmann R D, Ketchum K A, Klenk H P, Gill S, Dougherty B A, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness E F, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak H G, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzegerald L M, Lee N, Adams M D, Hickey E K, Berg D E, Gocayne J D, Utterback T R, Peterson J D, Kelley J M, Cotton M D, Weidman J M, Fujii C, Bowman C, Watthey L, Wallin E, Hayes W S, Borodovsky M, Karp P D, Smith H O, Fraser C M, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]