Abstract

Background: Although healthcare workers (HCWs) in long-term care (LTC) have experienced significant emotional and psychological distress throughout the pandemic, little is known about their unique experiences. Objective: This scoping review synthesizes existing research on the experiences of HCWs in LTC during the COVID-19 pandemic. Method: Following Arksey and O’Malley’s framework, data published between March 2020 to June 2022, were extracted from six databases. Results: Among 3808 articles screened, 40 articles were included in the final analysis. Analyses revealed three interrelated themes: carrying the load (moral distress); building pressure and burning out (emotional exhaustion); and working through it (a sense of duty to care). Conclusion: Given the impacts of the pandemic on both HCW wellbeing and patient care, every effort must be made to address the LTC workforce crisis and evaluate best practices for supporting HCWs experiencing mental health concerns during and post-COVID-19.

Keywords: healthcare workers, long-term care, mental health, moral distress, older adults, COVID-19

What this paper adds

• This paper provides valuable insights into the psychological burdens and long-term care (LTC)-specific challenges experienced by healthcare workers (HCWs) during the pandemic.

• In addition to COVID-19-related stressors, LTC workers are especially vulnerable during the pandemic due to systemic and intersectional inequalities.

• Despite many challenges and pressures, some HCWs reported immense satisfaction and pride in caring for LTC residents during the pandemic.

Applications of study findings

• Finding from this study can inform best practices and development of mental health policies to support HCWs, as well as address intersectional inequalities within the LTC sector.

• Programs to reward, encourage, and build resilience among HCWs in LTC should be expanded to mitigate the multi-faceted impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

• Occupational supports in LTC settings should address staffing and ongoing systematic challenges that disproportionately harm some HCWs over others.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has severely disadvantaged many groups, including older adults and those living in long-term care (LTC) homes. Across the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, 93% of COVID-19 deaths were among those age 60 or older (OECD, 2021). Amongst 16 other OECD countries, Canada reported the highest proportion of all COVID-19-related deaths (∼81%) among LTC residents during the initial wave of the pandemic (Canadian Institute for Health Information [CIHI], 2020; Comas-Herrera et al., 2020). In Canada, the profound impact of the pandemic in the LTC sector was attributed to pre-existing deficiencies including economic and operational difficulties (Estabrooks et al., 2020). Pre-pandemic, LTC homes in many countries, including the United States (US), Canada, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom (UK), and Denmark, were plagued for decades by underfunding, overcrowding, inadequate facilities, and a lack of appropriate regulation and oversight (Bourgeault et al., 2010; Estabrooks et al., 2015; Langins et al., 2020). Moreover, limited resources (human and non-human) including long-standing staffing shortages in the LTC sector have resulted in an increased use of part-time and casual workers and workers holding multiple jobs. Since the pandemic, staffing shortages have worsened with over 86% of LTC homes in Canada reporting at least one staffing related challenge in 2020, and a 71–77% increase in overtime hours and absenteeism in the sector (Clarke, 2021). In addition to the staffing inadequacies, many Canadian LTC homes face existing infrastructure challenges, including older buildings, poor technology and lack modern resources that are necessary to deliver quality resident care (Langins et al., 2020). In many cases, the facility size, design, and age of LTC homes, including shared rooms, narrower hallways and limited space for social gatherings, make physical distancing and segregation of infected residents and other safety measures difficult to implement (Estabrooks et al., 2020), thus enabling easier transmission of the virus (Applegate & Ouslander, 2020).

Emerging evidence (Fisher et al., 2021; Kang et al., 2020) suggests that the unpreparedness of health systems to tackle the pandemic and worsening LTC conditions across many of the OECD countries have severely impacted the health and well-being of healthcare workers (HCWs) (e.g., care aides, nurses, physicians, social workers), as many report high stress and mental problems such as anxiety, panic attacks, and depressive symptoms. A Canadian longitudinal study found the prevalence of anxiety and depression had increased by 10%–15% among nurses in all healthcare sectors during COVID-19 compared to pre-pandemic; cross-sector analysis, however, showed the largest increase in these mental health symptoms were experienced by nurses in LTC (Havaei et al., 2021). Similarly, a 2020 study from the US reported that 50% of LTC workers are at increased risk of severe illness from COVID-19, including hospitalization and death (Gibson & Greene, 2020). Although HCWs in all sectors faced tremendous stress during the pandemic, HCWs in LTC encounter additional challenges and stressors, such as job insecurity, chronic low pay, temporary and part-time work compared to their counterparts in other sectors (International Labour Organization, 2018; Osman, 2020). On average, across the OECD countries, women hold about 90% of the jobs in the LTC sector, and earn significantly less than half the national median annual earnings (OECD, 2021). In Canada, unregulated care providers (73%), immigrant and racialized women are overrepresented among care workers in LTC (Estabrooks et al., 2015)—a group that has been especially vulnerable during the pandemic due to systemic and intersectional inequalities (Lightman, 2022). The unstable and precarious nature of employment in the LTC workforce (e.g., part-time, under-paid) requires critical attention.

Throughout the pandemic, LTC homes have been in the media spotlight, eliciting much needed and long overdue discussions on potential redesign of the sector (Estabrooks et al., 2020). While there are emerging studies recounting the experiences and mental health concerns of general HCWs (Gialeb et al., 2022; Muller et al., 2020), only a few have focused on the experiences of HCWs in LTC. Despite the critical role that LTC workers continue to play in supporting the needs of residents and their families, little is known about the psychological and mental health impact of COVID-19 on this precarious workforce. This review aims to synthesize the available evidence on the experiences of HCWs in LTC during the COVID-19 pandemic to shed light on their unique challenges, and effective strategies for improving HCWs’ mental wellbeing during and post-pandemic. The study findings will shed light on the global LTC workforce, resident care outcomes, and offer strategies to support this vulnerable healthcare sector.

The Review

Aim

The aim of this scoping review was to synthesize the evidence pertaining to the experiences of HCWs in LTC during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research Question

The review sought to answer the following research question: What are the experiences of HCWs in LTC during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Methods

Study Design

This scoping review was guided by the five stages described in Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework, with recommendations from Levac et al. (2010) for advancing the methodology of scoping reviews. This methodology was chosen due to its capacity to support knowledge synthesis pertaining to an exploratory research question, various types of evidence, and gaps in a research field area (Levac et al., 2010). The scoping review results were reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021).

Data Sources

In consultation with an experienced health sciences librarian trained in conducting systematic reviews, an appropriate search strategy was developed, revised, and updated for the following databases: CIHNAL, AgeLine, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, OVID, and Google Scholar. The search strategy, including an eligibility checklist, was developed to identify studies on HCWs in LTC.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria required results to be peer-reviewed empirical research studies published in English between March 1, 2020, and June 1, 2022, with no restrictions in terms of country, thus establishing a broad review of the literature on LTC HCWs’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Supplementary Table 1). Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method studies were included. Review studies, commentaries, and policy reports/briefs were excluded.

Search Strategy

A systematic and comprehensive search strategy was created using the medical subject heading (MeSH) for relevant studies that met the inclusion criteria. Under supervision of the project lead (SB), two of the study authors (AI and AH) independently searched the computerized databases using the finalized string of search terms and combined Boolean key search terms such as, “COVID-19,” “novel coronavirus 2019,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “health care worker,” “mental health,” “nurse,” and “long-term care” (see Supplementary Table 2). Search terms were adapted to each databases search format (e.g., separating the sting of phrases into different search boxes separated by “AND”). The reference lists of all relevant articles and “related citations” were hand-searched for additional articles and studies not identified in our original search. All potentially relevant studies were scrutinized against pre-specified inclusion criteria to confirm eligibility in and contribution to our study.

Study Selection and Abstraction

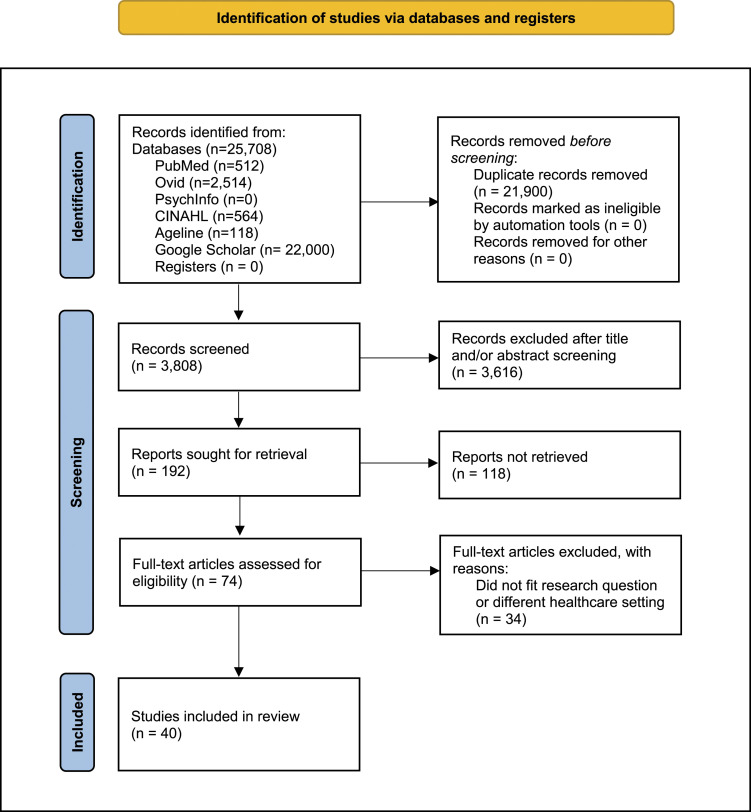

The study selection was an iterative process involving three interrelated steps: (1) title and abstract reviews, (2) full-article reviews, and (3) reviewers’ examination of reference lists from full articles to identify articles for possible inclusion. The authors used Covidence online software (https://www.covidence.org/), the standard platform for Cochrane Reviews, to manage study selection. Initially, 25,708 articles were identified using the search design and inclusion criteria, of which, 21,900 duplicates were removed, yielding a total of 3808 articles. Each of the team members independently screened/scrutinized the titles and abstracts against the selection criteria and indicate “Yes” or “No” whether to be included or excluded. Ambiguities and disparities were discussed and resolved with a third reviewer. Abstracts that met the eligibility criteria automatically moved to the full text review list in Covidence for the research team to perform a complete review of the articles (n = 192). Once all titles and abstracts were reviewed twice and all discrepancies arbitrated during regular bi-weekly Zoom meetings, the research team performed full-text reviews of the resulting 74 articles. In the second phase of study selection, each team member was randomly assigned a set of articles for full-text review using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria––approximately 18 articles per reviewer. The third and final phase involved examining (i.e., hand searching) the reference lists of included articles for additional pertinent studies that were not previously identified, resulting in a total of 40 articles for review (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of literature search and screen process (Page et al., 2021).

Note. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Data Extraction

Two authors (SB and RW) independently extracted and organized data from the full-texts of articles included in the review using descriptive analytical techniques (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005) in ATLAS.ti 8 based on the inclusion criteria. The results were cross-checked for accuracy and coding validity. Any discordance between the reviewers was discussed among the team until consensus is reached. The data were exported into Microsoft Excel. The Joanna Briggs Institute’s (2016) “Data Extraction Form for Experimental/Observational Studies” was adapted to analyze and tabulate the characteristics and findings of the studies. See Table 1 for details about the articles.

Table 1.

Article Summary.

| Author, year | Country | Aim of study | Study design/methods | Sample | Study findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilal et al. (2020) | Pakistan | To explore the experiences of staff providing care to elderly residents during the COVID pandemic | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) | n = 27 (5 male, 22 female) | Professional “caregivers” experienced fear of contagion and in turn felt lower motivation to work |

| Blanco- Donoso et al. (2021) | Spain | To explore levels of satisfaction among nursing home workers during the COVID-19 pandemic | Cross-sectional quantitative | n = 335 (66 male, 269 female) | Workers (including physicians, nurses, social workers, and other workers) had high levels of satisfaction with social support at work helping found to promote satisfaction |

| Blanco- Donoso et al. (2020) | Spain | To examine the psychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on nursing home workers | Cross-sectional quantitative (online questionnaires) | n = 228 (45 male, 183 female) | Workers (including physicians, social workers, and other workers) report high workload and social pressure, as well as fear of contagion, and secondary traumatic stress |

| Brady et al. (2022) | Ireland | To evaluate the mental health of long-term care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic | Cross-sectional quantitative (online survey) | n = 390 (86.4% female) | Workers (including nurses, healthcare assistants, and non-clinical staff) had suicidal thoughts and well-being scores indicating low mood |

| Briggs et al. (2021) | United Kingdom | To explore the perspectives and experiences of long-term care workers during the pandemic | Qualitative (open ended interviews) | n = 15 | Adult social care workers experienced stress, increased workload and feelings of pressure as well as faced mental health problems |

| Brito Fernandes et al. (2021) | Portugal | To explore the perceived readiness and safety of nursing homes against the COVID-19 pandemic as well as worker experiences | Quantitative (survey plus open-ended questions) | n = 720 (93% female) | Workers (including nurses, social workers, physicians, and other workers) reported outbreak capacity and training as areas for improvement for pandemic response |

| Bunn et al. (2021) | United Kingdom | To evaluate the experiences of care home staff during two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic | Mixed methods (online surveys participants (including senior care and in-depth interviews) | n = 238 survey (n = 15 for interviews) | The pandemic had a significant effect on the well-being of care home staff. Participants (including senior care workers, junior care workers, and other workers) reported good morale due to a supportive environment |

| Cohen- Mansfield (2022) | Israel | To understand the impact of COVID-19 on staff in long term care facilities | Mixed methods (survey and open- ended questions) | n = 52 facilities | Workers (including nurses, physicians, social workers, and other workers) experienced increased workload due to a reduced workforce and negative mental health effects |

| Corpora et al. (2021) | United States | To explore nursing home staff perceptions of a person-centered communication intervention during the pandemic | Qualitative (telephone interviews) | n = 11 | Nursing home providers, namely, nursing staff, experienced disproportionately greater burdens and pressures |

| Dohmen et al. (2022) | Netherlands | To explore care home staff experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic | Qualitative (open ended narrative responses) | n = 424 (all female) | Workers (including nurses, nursing assistants, activity workers, and other workers) experienced a great degree of internal conflict when enforcing pandemic mitigation measures |

| Freidus and Shenk (2020) | United States | To explore the experiences of care workers working in COVID-19 units during a major outbreak | Qualitative (in-depth semi-structured interviews) | n = 5 (4 staff members, 1 administrator) | Workers (including nurses, nursing assistants, and a facility manager) in COVID-19 units experienced fear of contagion, frustration, and trauma |

| Giebel et al. (2022) | United Kingdom | To explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of workers in long term care homes | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) | n = 42 (11 male, 31 female) | Participants (including carers, managers, and other workers) experienced anger and frustration, stress, and burnout. They reported an overall negative impact on their mental health |

| Hoedl et al. (2022) | Austria | To explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of nursing home staff | Qualitative (interviews) | n = 18 (14 female) | Workers (including nurses, nursing aides, and care aides) reported feelings of uncertainty, fear, and stress |

| Hung et al. (2022) | Canada | To explore the experiences of long-term care home staff during a COVID-19 outbreak | Qualitative (focus groups and interviews) | n = 30 (6 male, 24 female) | Workers (including nurses, care aides, and dietary staff) reported feelings of anxiety with regards to safety and safety protocols, and lack of PPE |

| Husky et al. (2022) | France | To explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health nursing home staff | Quantitative (questionnaires) | n = 127 (89% female) | Workers (including all nursing home roles) reported a fear of infecting others and mental health issues and feelings of depression |

| Krzyzaniak et al. (2021) | Australia | To evaluate the experiences of LTC workers during the COVID-19 pandemic | Quantitative (survey with open-ended questions) | n = 371 (87% female) | Workers (including all residential care facility roles) reported problems with regards to adequate PPE availability. Workers experienced increased workload, stress, and emotional toll |

| Leontjevas et al. (2021) | Netherlands | To understand from the perspective of nursing home practitioners whether challenges in dealing with residents during the COVID-19 pandemic changed | Mixed methods (online survey consisted of closed and open-ended questions) | n = 323 (psychologists, physicians, nurse practitioners) | Workers (including elderly care physicians, psychologists, and nurse practitioners) reported increases in challenging behavior among residents, an overall increase in workload and a decrease in work satisfaction |

| Leskovic et al. (2020) | Slovenia | To explore job satisfaction and burnout levels among healthcare workers in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic | Mixed methods (survey and in-depth interview) | n = 781 (nurses, nursing assistants) | An increase in burnout syndromes was evident with workers (including nurses, nurse assistants, and nurse aides) experiencing heightened emotional exhaustion and lack of recognition |

| Lethin et al. (2021) | Sweden, Italy, Germany, and United Kingdom | To compare staff experiences of stress and anxiety as well as internal and external organizational support | Quantitative (questionnaire) | n = 595 (nurses, nursing assistants, and other providers) | Support provided to staff differed greatly across staff categories (nurses vs. aides) and within each country. Structural, political, cultural, and economic factors within each country played a key role |

| Lightman (2022) | Canada | To explore the impact of the pandemic on the working lives of immigrant women in long term care facilities | Qualitative (in-depth online interviews) | n = 25 (all women) | Mmigrant women health care aides in LTC facilities reported experiences of economic and social exclusion being heightened by pandemic conditions |

| Martín et al. (2021) | Spain | To explore mental health and health related quality of life among care home workers | Quantitative (questionnaires) | n = 210 (86.19% female) | Symptomatology of stress, depression, anxiety, health related quality of life, etc. were affected among LTC workers (including nurses, administrators, cooking staff, psychologists, and other workers) |

| Martínez- López et al. (2021) | Spain | To explore how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected healthcare workers in residential centers/nursing homes for the elderly | Cross-sectional quantitative (survey) | n = 296 (13.9% male, 86.1% women) | Many workers (including nurses, nursing assistants, and other workers) were found to be emotionally exhausted and suffering from depersonalization |

| McGilton et al. (2021) | Canada | To understand the roles of nurse practitioners in optimizing care in long term care homes during the COVID-19 pandemic | Phenomenological approach qualitative (interviews) | n = 14 (nurse practitioners: 11 women, 3 male) | Nurse practitioners showed concerns regarding the spread of COVID-19 and the ability to adequately support staff |

| Miller et al. (2021) | United States | To understand perceptions of preparedness among nursing home social workers for the COVID-19 pandemic | Cross-sectional quantitative (social media surveys) | n = 63 (1 male, 62 female) | Majority of social workers felt unprepared to meet the demands and challenges posed by the pandemic |

| Pardos et al. (2022) | Spain | To analyze the extent to which potential risk and protective factors against burnout have influenced nursing home workers during the COVID-19 pandemic | Cross-sectional quantitative (online survey) | n = 340 (health professionals) | Increase in hours has negative impacts on burnout among workers (including managers, direct care staff, technical staff, and other workers). Perceived social support and availability of resources were found to have protective effects |

| Nyashanu et al. (2022) | United Kingdom | To explore the triggers of mental health problems among healthcare workers in care homes during the COVID-19 pandemic | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) | n = 40 (20 female, 10 male) | Triggers of mental health problems among frontline workers (all types) were found to include fear of contagion and infection of others and lack of recognition |

| Pförtner et al. (2021) | Germany | To investigate whether the demands of the COVID-19 pandemic are increasing the intent to quit the profession among long-term care managers | Cross-sectional quantitative (online survey) | n = 532 and n = 301 (two cycles of surveys) | A significant association was found between the perceived pandemic-specific demands and the intention to leave the profession among care managers |

| Reynolds et al. (2022) | Canada | To explore the experiences and needs of staff during the COVID-19 pandemic in long term care homes | Mixed methods (survey with open-ended questions) | n = 70 (care home staff and management) | Workers (including clinical staff, managers, administrators, and other workers) experienced stress, increased workloads, fear of contagion, and overall caregiver burden |

| Riello et al. (2020) | Italy | To test the prevalence of anxiety and post-traumatic symptoms among care home workers during the first COVID-19 outbreak | Cross-sectional quantitative (online survey) | n = 1140 (188 nursing and care home) | Workers (including healthcare staff, technical staff, and administrative staff) commonly reported post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety |

| Rutten et al. (2021) | Netherlands | To understand the experiences of workers in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic | Qualitative (focus groups) | n = 29 (5 male, 24 female) | Workers (including nurse assistants, managers, therapists, and other workers) experienced a loss of daily working structure and expressed an increased need for social support |

| Sarabia-Cobo et al. (2021) | Spain, Italy, Peru, and Mexico | To understand the emotional impact and experiences of geriatric nurses in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) | n = 24 (7-Spain, 7-Italy, 4-Peru, 6-Mexico) | Geriatric nurses experienced emotional exhaustion and shared fears of contagion |

| Scerri et al. (2022) | Malta | To understand the experiences of long-term care nurses working during the COVID-19 pandemic | Qualitative (interviews, open-ended) | n = 9 (6 females, 3 males) | Nurses reported having feelings of frustration, anger, and sadness and also reported facing an increased workload |

| Snyder et al. (2021) | United States | To understand the experiences of nursing home staff during the COVID-19 pandemic | Qualitative (focus groups) | n = 110 (23 focus groups) | Workers reported a toll on their well-being and increased stress along with staffing issues within facilities |

| Spilsbury et al. (2021) | United Kingdom | To identify pertinent care and organizational concerns expressed by care home staff members | Qualitative (self-formed closed WhatsApp discussion group) | n = 250 (mixed of care home staff) | Workers’ (including certified nursing assistants and environmental services staff) concerns about infection prevention and support and maintenance of effective care for residents and staff |

| Tebbeb et al. (2022) | France | To evaluate the mental health of nursing home staff and the psychological impact of the COVID pandemic on workers using a questionnaire | Mixed methods (12 semi-structured interviews) | n = 373 (survey - 82% female; interviews) | Workers (including healthcare staff, managers, and other workers) found the questionnaire and preventative measures helpful in terms of reducing stress |

| Tomaszewsk a et al. (2022) | Poland | To evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychosocial burden and job satisfaction among LTC workers | Quantitative (survey questionnaires) | n = 138 (96.4% female) | Nurses rated the characteristics in the workplace relating to psychosocial risks as being at an average level with emotional commitment also being rated as being a medium level |

| van Dijk et al. (2022) | Netherlands | To evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of workers in LTC homes | Quantitative (questionnaires) | n = 1669 (91.6% female) | Some workers (including healthcare professionals and non-care workers) reported high levels of burnout and depressive symptoms |

| White et al. (2021) | United States | To explore the experiences of front-line nursing home staff during the COVID-19 pandemic | Mixed methods (electronic survey and open-ended questions) | n = 152 | Workers (including direct-care staff and administrators) expressed concerns regarding constraints on testing and lack of PPE equipment. Workers also experienced fear of contagion and reported burnout |

| Yau et al. (2021) | Canada | To describe the experiences of long-term care workers during COVID-19 outbreaks | Qualitative (key informant, semi-structured interview) | n = 23 | Workers (including frontline staff, nurses, managers, administrators, and other workers) reported needing better management of outbreaks including early case identification, public health interventions, training and education, PPE, workplace culture, leadership, communication, and staffing |

| Zhao et al. (2021) | China | To understand the challenges faced by nursing home staff during the COVID-19 pandemic | Qualitative (in-depth semi-structured interview) | n = 21 (all females) | Workers (including nurse managers, nurses, and nursing assistants) experienced fear of contagion and faced heavy workloads. Workers described coping strategies involving support from fellow peers and management groups |

Synthesis

Given the emergence of the COVID-19 literature and the limited number of relevant articles, no meta-analysis or formal assessment of the methodological quality or appraisal of individual studies was performed and/or explored in depth. Because of the broad nature of scoping reviews, no rating of quality or level of evidence is provided, thus recommendations for practice cannot be graded (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2016). However, each stage of the Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework provides both clarity and rigor of the review process. The analysis was conveyed in prose to outline and explain the results, which allowed key concepts from the research questions to be used as the initial coding categories (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). The findings from the included studies were synthesized into thematic groups using thematic content analysis.

Findings

The initial search strategy identified 25,708 records, of which 40 studies were included in the final review, consisting of 18 (45%) qualitative studies, 14 (35%) quantitative studies, and 8 (20%) mixed-method studies (see Table 1). Most of the publications were from Europe (e.g., Spain, Netherlands, UK) and North America. Figure 1 displays the PRISMA Flow Diagram summarizing the literature search and the screening process used to identify studies for inclusion in this review.

Thematic analysis

To synthesize the core concepts underpinning the scoping review, findings were categorized/organized according to three interrelated themes pertinent to our study aims, while recognizing that experiences/emotions are rarely discrete categories: (i) carrying the load; (ii) building pressure and burning out; and (iii) working through it. The themes were named based on the data extraction and discussion within the research team.

Carrying the Load

Carrying the load refers to the cognitive, socio-emotional, and psychological burden carried by HCWs throughout the pandemic and the impact on their health and wellbeing. This burden, or “emotional load” (Dohmen et al., 2022), was directly linked to work-related demands and tremendous responsibilities placed on HCWs in the LTC sector. Twenty-five of the 40 studies reported negative emotions and internal struggles that diverse groups of LTC workers (i.e., care aides, nurses, physicians) experienced in caring for infected and dying residents. Some of the emotions described include a deep sense of sadness, helplessness, anger, frustration, discomfort, and fatigue caused by high-intensity work and concerns for residents’ safety as many were dying from COVID-19, and what HCWs felt could have been preventable. Many of the workers reported psychological consequences of working in LTC such as uncertainty and fear and described how witnessing suffering and preventable deaths illuminated both “their individual devaluation as low-paid formal caregivers, and that of their aging residents, by the larger society” (Freidus & Shenk, 2020, p. 206). One care home staff in the US described a sense of helplessness and frustration as they witnessed immerse grief by stating: “they’re literally smothering to death; they’re literally choking to death. And all you can do is sit there and hold their hand and try to make them comfortable... This possibly could have been prevented” (Freidus & Shenk, 2020, p. 204).

The effects of carrying this emotional burden and feelings of guilt often led to “internal conflict” and “moral distress” for HCWs (Dohmen et al., 2022). Most HCWs conveyed a deep-seated grief, anxiety, and concern for the quality of life of residents as many deteriorated. One Maltese nurse expressed that “[h]er emotional turmoil was associated with moral distress of not being able ‘to be a nurse’ in the current circumstances” (Scerri et al., 2022, p.6) as a result of COVID-19 mitigation measures. These statements reflected HCWs’ concerns regarding the precautionary measures that were put into place to ensure physical distancing, in particular the ban of visitors and the psychological toll on both residents and caregivers. To cope with the pandemic-induced stressors, HCWs adopted various strategies, including seeking support/guidance from peers and leadership, which they felt was integral to their wellbeing. A study of 720 Portuguese LTC staff identified teamwork (78%), and staff training (70%) as key strategies to ensure staff wellbeing and a safety culture (Brito Fernandes et al., 2021).

Building Pressure and Burning Out

Building pressure and burning out refers to the chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors that HCWs experienced as job demands rose. Twenty of the 40 studies reported various symptoms associated with staff burnout, which are categorized as: physical (chronic fatigue, extreme exhaustion), emotional (fear, anger, frustration), cognitive (mental fatigue, difficulty in making decisions), and behavioral (cynicism, negativism). More profoundly, there were reports of increase in burnout syndromes, especially intensified emotional exhaustion and lack of personal accomplishment (Krzyzaniak et al., 2021; van Dijk et al., 2022), resulting in job dissatisfaction and high turnover. One British care home staff said, “I burned out in the end. [...] In hindsight, it was so draining because it was constant. And it was constant fear, and I think fear is the just the worst thing, the fear from getting ill and my actions making someone ill—or my lack of actions, I should say. That’s a horrible thought to have” (Bunn et al., 2021, p. 395). In other instances, staff including carers and managers were “overburdened and burned out” and experienced “emotional upset” (Giebel et al., 2022, p. 10) when working with dying patients/residents. In fact, a national study of aged care facility workers in Australia found that 33% of respondents suffered from burnout during the pandemic (Krzyzaniak et al., 2021), underscoring the immense impact of COVID-19 on the mental well-being of LTC workers.

In all the studies reviewed, HCWs reported feeling physically and emotionally exhausted due to longer workdays and unmanageable workloads associated with a constantly changing environment, monitoring and documentation processes, screening staff and visitors, and providing additional communication and support to residents and their families. In a sample of 1669 Dutch nursing home staff, 19.1% reported high levels of depressive symptoms and 22.2% burnout (van Dijk et al., 2022). Another study with Spanish nursing home workers (n = 335), found that social pressure from work and emotional exhaustion were negatively related to their professional satisfaction (r = −0.14, p < 0.05; r = −0.42, p < 0.01, respectively), while contact with death and suffering and social support at work were positively related to professional satisfaction (r = 0.20, p < 0.01; r = 0.25, p < 0.01, respectively) (Blanco-Donoso et al., 2021). LTC workers also expressed mental exhaustion, as one Austrian carer stated, “I was at home and really started to cry. Because my nerves just felt like they could not take anymore. Hopefully it’s over soon, because otherwise I’ll break” (Hoedl et al., 2022, p. 6). In referencing the long-standing deficiencies that existed within the LTC sector pre-and during the COVID-19 pandemic, one HCW noted that “we and all the patients are the victims of politicians. I barely worked and lived before the coronavirus, but now I’m a zombie” (Leskovic et al., 2020, p. 668).

In addition to burnout, HCWs reported experiencing mental health conditions including generalized anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to the ongoing exposure to the traumatic events and in performing day-to-day tasks. One nurse in a US study was quoted stating: “I have PTSD... Going through this trauma, I’m still trying to come out of it.... I say that I don’t think I mentally could do it, but I sit here, and I tell myself, like I just told you, if I had to do it, I would do it again...” (Freidus & Shenk, 2020, p. 205). This statement reflects the ongoing stressors that HCWs continue to face since the emergence of the pandemic. An Italian study found that HCWs, especially women, who had recently been in contact with COVID-19-positive patients or colleagues were more likely to report moderate-to-severe symptoms of anxiety (22%) and PTSD (40%) (Riello et al., 2020). Similarly, in a sample of 390 Irish nursing home staff, 38.7% reported a WHO-5 score ≤32, indicating significantly low mood and poor wellbeing, and 13.8% reported suicidal ideation and suicide planning (Brady et al., 2022). Excessively high levels of mental and emotional exhaustion were consistently reported by HCWs in almost all the articles (Blanco-Donoso et al., 2021; Corpora et al., 2021; Prados et al., 2022). Participants emphasized that they did their best to offer quality care to residents while working under exceptionally challenging circumstances. While most of the articles reported increased burnout and dissatisfaction with the LTC work environment, none explicated mentioned high staff turnover. A study of German managers in LTC facilities (n = 833), however, found a significant association between the perceived pandemic-specific and general demands and intention to leave the profession (Pförtner et al., 2021). Overall, all the articles stressed the importance of supportive work environments.

Working Through It

Working through it represents that structural and systemic barriers and challenges that exists within the LTC sector that HCWs constantly had to overcome in caring for residents throughout the pandemic. Twenty-two of the 40 studies reported HCWs’ concerns about the LTC work environment including the facility size, design, and/or age of the home (e.g., narrowing hallways, shared accommodations), short-staffing, lack of preparedness and safety, availability/lack of job resources such as personal protective equipment (PPE) (Blanco-Donoso et al., 2020; Tomaszewska et al., 2022). Many studies commented on how the pandemic has worsened the already precarious working conditions in LTC pre-COVID-19 including the lack of social, economic, and professional recognition of LTC workers compared to their counterparts in other sectors.

HCWs also expressed fear of contagion (contracting the virus) and of infecting their loved ones when working under conditions of extensive contact with suffering and death of residents. The fear of getting infected and infecting others was a primary cause of concern shared among HCWs of all job types. In a multi-national study conducted in Spain, Italy, Peru, and Mexico, a geriatric nurse stated, “Ofcourse I am afraid, I am terrified to think that I have it without knowing, and that I am infecting the residents ... and that is very scary” (Sarabia-Cobo et al., 2021, p. 872). Due to short staffing, many HCWs felt a sense of obligation to return to work even if their own lives were at risk as one UK care staff noted, “I’ve had so many people say to me in my personal life, ‘I’m still going to work even if I test positive’ because I can’t afford not to work” (Bunn et al., 2021, p. 394). The stigma associated with contracting and transmitting the virus caused many HCWs to withdraw from friends and family leading to increased loneliness and social isolation. A certified nursing assistant in a study of American staff summed up the duality of the fear by stating: “You’re not only worried about yourself and your residents, but you’re worried about bringing it home as well” (Snyder et al., 2021, p. 6). While HCWs continue to risk their lives to care after patients, some felt attacked for upholding the COVID-19-related infection control policies/practices. In an Australian study, 43% of aged-care facility workers reported unfair or abusive treatment by family or friends of residents (Krzyzaniak et al., 2021). Many HCWs felt that they were being blamed for “bringing in the virus to the LTC site from their community” (Lightman, 2022, p. 7)—sentiments that some HCWs felt were prejudicial and discriminatory because of their race/ethnicity, further highlighting the widespread racial and social inequalities that LTC workers experienced at work.

Support and recognition were commonly cited as important factors in motivating HCWs especially during the pandemic (Giebel et al., 2022; Lethin et al., 2021; Lightman, 2022; Nyashanu et al., 2022). Many workers reported a sense of disappointment, felt undervalued, and unrecognized even though they were doing their best to adapt to the evolving crisis. One Canadian care home staff said, “You are my hero! You are doing essential work, blah blah blah’, you know guys, what about money? We didn’t get enough to be secure, you know” (Lightman, 2022, p. 6). HCWs felt that they were not being appreciated for their contributions. In a multi-country qualitative study of geriatric nurses, one Spanish health worker described a sense of under-appreciation stating: “Governments have failed...there has been no foresight, we are abandoned, exhausted...we fight alone” (Sarabia-Cobo et al., 2021, p. 873). Similar sentiment was expressed by care home staff and family carers in the UK, as one person was quoted saying, “I’m a bit angry with the government really and in another way, I can see that they’ve got to keep everybody safe” (Giebel et al., 2022, p. 6). In another study, a nurse in Slovenian nursing home was quoted saying that; “The politicians have sacrificed us. We will totally burnout and the elderly will die due to COVID-19. We are worth nothing to them!” (Leskovic et al., 2020, p. 668). The sense of despair and disappointment was also attributed to the lack of recognition for their contribution in the healthcare system compared to their counterparts in hospitals (Nyashanu et al., 2022), no designated time off, and delays in receiving PPE and testing at the peak of the pandemic.

Despite the enormous burden of distress and potentially traumatic events experienced by HCWs in LTC homes, some studies (Blanco-Donoso et al., 2021; Dohmen et al., 2022) highlighted the positive feelings experienced by HCWs including a sense of duty and commitment to care and gratification and fulfillment working during the crisis and how their work contributed to the greater good of society. For instance, participants reported feelings of pride, satisfaction in helping others (Hung et al., 2022) and professional fulfillment in providing care to residents during the pandemic. HCWs who had more social support at work experienced higher levels of professional satisfaction despite the demanding work conditions.

Discussion

This paper presents the results of a scoping review examining the experiences of HCWs in LTCs during the COVID-19 pandemic. While emerging research during the pandemic has considered the experiences of HCWs broadly, a relatively smaller body of evidence has focused on the experiences of those working in LTC––a sector that has been greatly impacted by the pandemic (Ghaleb et al., 2021). Thematic findings from this review highlight the unique challenges and burdens experienced by HCWs in LTC across many job types (e.g., care aides, nurses, physicians, social workers, managers) and in different countries including the US, Canada, UK, Spain, and Italy (Di Mattei et al., 2021; Rabow et al., 2021), and points to areas for future practice and research.

Findings of this review indicate that the psychological and emotional burden experienced by HCWs related to the COVID-19 pandemic are directly linked to structural and environmental factors within the LTC sector (Boamah et al., 2021a). In particular, the unpreparedness of this sector, rapid spread of the COVID-19 virus/illness, the high rate of resident mortality, and concerns about physical distancing measures and other COVID-19-related policies created moral distress and immerse pressure for front-line staff (CIHI, 2020; Comas-Herrera et al., 2020), and increased loneliness and social isolation for residents and their families (Boamah et al., 2021b). These findings align with emerging research from various countries including Italy (Di Mattei et al., 2021) and the US (Rabow et al., 2021), which have documented widespread grief, anger, and mental distress experienced by HCWs.

Our findings suggest a need for LTC-specific strategies to improve the health and wellbeing of front-line staff. Promoting positive mental health and coping through supportive workplace environments will not only benefit HCWs, but also improve the quality of care and life of residents and their family caregivers (Boamah et al., 2021b). Strategies that could be employed include expanded sick leave and mental health policies for HCWs that promote psycho-emotional and physical health. While so-called “mental health days” among HCWs have been documented in countries such as Australia (Lamont et al., 2017), they do not appear to be widely available or documented across other jurisdictions. There also remain significant barriers and stigma associated with taking time off for mental––rather than physical––health reasons. Given the impact of COVID-19 on both HCW wellbeing and patient care, there is an urgent need to evaluate best practices for supporting HCWs exposed to workplace-related stressors, while considering factors that might predispose workers to severe burnout and turnover.

Results of this review indicate that HCWs in LTC settings particularly geriatric nurses (Sarabia-Cobo et al., 2021) and other care staff (Leskovic et al., 2020) experienced high stress, anxiety, and depression, which heightens their risk of burnout. This finding is noteworthy given the mounting evidence including systematic reviews linking COVID-19 to poor patient care and burnout among HCWs in other sectors (Al Maqbali et al., 2021; Pappa et al., 2020). As such, policymakers and LTC leaders must provide essential resources for workers (e.g., PPE, virus testing policies), adopt strategies to support mental health concerns (e.g., counseling, employee assistance programs) and daily needs of staff outside of work (e.g., childcare), and improve crisis leadership skills (Wu et al., 2020). Other strategies could include evaluating COVID-19 responses within organizations and HCWs’ first-hand perspectives, which can inform the refinement of best practices whilst simultaneously curbing future harm amongst HCWs (Stelnicki et al., 2020). Furthermore, lessons learned from the pandemic can aid in structuring better staffing and workload management tools to improve staff work experiences (Udod et al., 2021).

Despite the challenges and hardships experienced by LTC workers during the pandemic, our findings suggest that their care work has been at times rewarding. These experiences suggest that not all pandemic-related experiences in LTC have been negative. This finding is thought to align with emerging COVID-19 research. For example, a recent study (Ke et al., 2021) of nurses working in hospitals in Wuhan, China found that most front-line nurses maintained a strong commitment to their work throughout the pandemic. Future research and practice should, therefore, consider means of acknowledging and rewarding HCWs for their ongoing work while building resilience among staff as the pandemic continues. These factors can serve to protect HCWs from burnout and other harmful secondary outcomes related to COVID-19 (Baskin & Bartlett, 2021). Further, in the context of LTC, there is growing work precarity and social marginalization as well as worsening of workplace inequalities and intersectional racism. The results of this review confirmed that research must address intersectional inequalities within LTC to better support HCWs during and post-pandemic (Lightman, 2022). As such, every effort must be made to prioritize principles of cultural safety and eradicate systemic barriers that exacerbate mental distress among HCWs and hinder quality of resident care.

Strengths and Limitations

This scoping review has several overarching strengths. The studies included were published in 12 countries, suggesting that the results are not country or region-specific. In other words, while LTC policies and structures may differ across countries, the experiences and challenges faced by HCWs in the included studies (i.e., stress, burnout, fear) were consistent across diverse geographical regions/locations. Only studies published in the US, Canada, and Australia reported significant fears and anxiety among HCWs linked to PPE shortages, indicating possible differences in contagion preparedness levels and supply chain effects across different regional and/or national LTC systems. With this in mind, future studies should examine whether trends in HCW experiences differ across countries that operate exclusively public LTC homes versus countries that offer a mix of public and private LTC services. As well, more studies are needed to identify possible contextual and occupational factors that may shape or mediate long-term impacts of the pandemic.

This scoping review was limited by the fact that studies not yet published (after June 2022) or translated in English have been missed and/or excluded. Also, detailed findings are not compared across worker type/role (e.g., nurses, care aides) as many studies included in this review did not often specify how the results differed by role. In line with scoping studies, the quality of evidence identified was not explored in-depth. Despite this, we are confident that the findings are meaningful, widely applicable given the various regions represented among included studies and offer valuable insight into the impacts of COVID-19 to date and lay the foundation for studies of long-term effects in the future.

Implications

Our exploration of literature identified a multitude of workplace factors which impact HCWs’ job performance and wellbeing, and addressed a crucial knowledge gap in the growing body of COVID-19-related research. Going forward, researchers, practitioners, and decision-makers are urged to consider means of supporting HCWs in LTC in order to promote their wellbeing, and those of their care recipients. Future research into HCW supports must consider: (1) how existing workplace supports have fallen short in the context of COVID-19; (2) how and to what extent current promising approaches at various levels (e.g., directed funding mechanisms, wellness coaching) can be administered in additional settings/contexts; and (3) how specific sub-groups of HCWs in LTC (e.g., racialized women) can be empowered and protected from disproportionate burden. The psycho-emotional and social health of HWCs must be both protected and supported through critical enhancements to the LTC sector. Findings from this review can inform future research agenda to highlight gaps in knowledge regarding the long-term and system-wide impacts of the pandemic on LTC staff and residents. Additionally, studies should consider investigating how COVID-19 may have affected HCWs during co-occurring climate-related disasters such as hurricanes and wildfires and the additional strain they placed on the already unstable healthcare systems. In doing so, researchers can develop context-specific strategies and interventions to strengthen health systems across the globe.

Our findings also point to areas for improvement within and beyond the LTC context to support HCWs and residents/patients alike. Several regions have begun to implement promising strategies in response to the growing need for expanded HCW supports. For example, an innovative program in the US trained advanced nursing students to provide one-on-one wellness support to nurses working in a COVID-19 hotspot via wellness coaching sessions with coaching support focused on eating, sleep, stress, and physical activity guidance (Teall & Melnyk, 2021). Program results show immense promise as 94.7% of participating nurses felt the program contributed to improved mental and physical health (Teall & Melnyk, 2021). Given the findings from this review, exceptional measures must be in place to retain LTC workers. In Canada, US, and other countries, the federal government has implemented programs such as, the new Recruitment and Retention Incentive Programs, to attract and retain skilled HCWs to LTC homes with the highest level of staffing need to help safeguard the health of residents and their families. In terms of improved support for compensation and benefits, so-called “pass-through” or “directed payment” programs (Feng et al., 2010), and more recently, the “Patriot Pay” plan, a temporary bonus or increase in hourly wage, have been implemented in several US states since the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure that essential workers receive high compensation than the unemployment insurance rate (Romney, 2020). These funding mechanisms not only reduces the incentive for second job holding and turnover but are essential for minimizing the spread of the virus thus ensuring safety of residents and better outcomes (Loomer et al., 2022). Given these promising approaches, policymakers and LTC administrators are urged to consider additional means of supporting staff through such creative and innovative programs.

Additional recommendations for supporting HCWs during and post-COVID-19 include creating safe and healthy work environments for staff and providing appropriate recognition (e.g., reward system, flexible working hours) to show appreciation for the significant role and contributions that HCWs make to the healthcare system, and in doing so, foster resilience among workers and increase organizational commitment (Greenberg, 2020). Protecting the psychological and mental health of HCWs should be of outmost importance for all health care leaders and organization. Health care administrators and leaders are urged to provide specialist counseling services for HCWs to ensure that trauma and strain linked to work do not manifest into long-term psychological impacts (Brophy et al., 2021). The vast scientific literature on psychological trauma, exposure, and consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic shows that some individuals, including those from racialized and immigrant groups are at even higher risk of experiencing psychological distress and adverse outcomes (Greenberg, 2020). Yet, only few studies have focused on specific psychological support intervention programs for HCWs despite the WHO’s urgent call for tailored and culturally sensitive mental health interventions and psychological support programs for HCWs (Holmes et al., 2020). With the awareness of a growing work precarity, social marginalization, and worsening of workplace inequalities and intersectional racism in healthcare as highlighted in this review, LTC leaders and administrators should pay particular attention to HCWs in high-risk groups. Moreover, policymakers and leaders must recognize potential psychological difficulties some workers may face and implement “return to normal work” interviews as an approach to ensure HCWs’ mental health and identify the presence of pertinent stressors (e.g., bereavement or burnout), which can help reduce absenteeism rates and staff shortages (Greenberg, 2020). Other innovative strategies to support HCWs could include digital approaches such as remote psychological first aid (PFA) and online platforms or learning packages where experts with direct pandemic experiences from the front-line provide advice and evidence-based mental health guidance to other HCWs, including self-care strategies (e.g., shift work, breaks, healthy lifestyle behaviors), and managing emotions/coping (e.g., anxiety, moral injury) (Blake et al., 2020). Studies in the UK and Malaysia (Blake et al., 2020; Sulaiman et al., 2020) have shown the PFA protocol to be an effective method of assessing the psychological impacts of COVID-19 remotely via mobile application and phone calls, and can help people in distress and support them to cope well with their psychological, emotional, and social needs/challenges. Given the immense pressure faced by HCWs and LTC facilities during this time, significant improvements are unlikely to take place without strong leadership and meaningful improvements to working conditions.

Conclusion

This paper shed light on the immense pressure that HCWs globally faced during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and the tremendous impact on their mental and physical health and wellbeing. The findings also highlighted the extreme vulnerabilities within the LTC sector. With the rising death toll in LTC coupled with the human resource issues and lack of pandemic preparedness, every effort must be made to address these long-standing systemic challenges to redress the workforce crisis in LTC and avoid more catastrophic outcomes presently and in future pandemics. By taking steps to build supportive work environments for HCWs and staff empowerment, LTC homes can limit many of the harmful secondary effects of the pandemic.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Experiences of Healthcare Workers in Long-Term Care during COVID-19: A Scoping Review by Sheila A. Boamah, Rachel Weldrick, Farinaz Havaei, Ahmed Irshad, and Amy Hutchinson in Journal of Applied Gerontology

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#478306).

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online

ORCID iDs

Sheila A. Boamah https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6459-4416

Rachel Weldrick https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5679-6066

Ahmed Irshad https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8866-9379

References

- Al Maqbali M., Al Sinani M., Al-Lenjawi B. (2021). Prevalence of stress, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 141, Article 110343. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applegate W. B., Ouslander J. G. (2020). COVID-19 presents high risk to older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68681(4), 681. https://doi:10.1111/jgs.16426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin R. G., Bartlett R. (2021). Healthcare worker resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(8), 2329–2342. 10.1111/jonm.13395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilal A., Saeed M. A., Yousafzai T. (2020). Elderly care in the time of coronavirus: Perceptions and experiences of care home staff in Pakistan. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 35(12), 1442–1448. 10.1002/gps.5386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake H., Bermingham F., Johnson G., Tabner A. (2020). Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: A digital learning package. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 172997(9), Article 2997. 10.3390/ijerph17092997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Donoso L. M., Moreno-Jiménez J., Amutio A., Gallego-Alberto L., Moreno-Jiménez B., Garrosa E. (2020). Stressors, job resources, fear of contagion, and secondary traumatic stress among nursing home workers in face of the COVID-19: The case of Spain. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 40(3), 244–256. 10.1177/0733464820964153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Donoso L. M., Moreno-Jiménez J., Gallego-Alberto L., Amutio A., Moreno-Jiménez B., Garrosa E. (2021). Satisfied as professionals, but also exhausted and worried!!: The role of job demands, resources and emotional experiences of Spanish nursing home workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(1), e148–e160. 10.1111/hsc.13422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boamah S.A., Dal Bello-Haas V., Weldrick R., Durepos P., Kaasalainen S. (2021. a). The cost of isolation: A protocol for exploring the experiences of family caregivers. Social Science Protocol, 4, 1–9. 10.7565/ssp.2021.v4.6190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boamah S. A., Weldrick R., Lee T. S. J., Taylor N. (2021. b). Social isolation among older adults in long-term care: A scoping review. Journal of Aging & Health, 33(7–8), 618–632. 10.1177/08982643211004174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeault I. L., Atanackovic J., Rashid A., Parpia R. (2010). Relations between immigrant care workers and older persons in home and long-term care. Canadian Journal on Aging, 29(01), 109–118. 10.1017/S0714980809990407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady C., Fenton C., Loughran O., Hayes B., Hennessy M., Higgins A., Leroi I., Shanagher D., McLoughlin D. M. (2022). Nursing home staff mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic in the Republic of Ireland. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 37(1), 1–10. 10.1002/gps.5648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs D., Telford L., Lloyd A., Ellis A. (2021). Working, living and dying in COVID times: Perspectives from frontline adult social care workers in the UK. Safer Communities, 20(3), 208–222. 10.1108/SC-04-2021-0013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brito Fernandes O., Lobo Julião P., Klazinga N., Kringos D., Marques N. (2021). COVID-19 preparedness and perceived safety in nursing homes in Southern Portugal: A cross-sectional survey-based study in the initial phases of the pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 187983(15), Article 7983. 10.3390/ijerph18157983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy J. T., Keith M. M., Hurley M., McArthur J. E. (2021). Sacrificed: Ontario healthcare workers in the time of COVID-19. NEW SOLUTIONS: A Journal of Environmental & Occupational Health Policy, 30(4), 267–281. 10.1177/1048291120974358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn D., Brainard J., Lane K., Salter C., Lake I. (2021). The lived experience of implementing infection control measures in care homes during two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. A mixed-methods study. Journal of Long-Term Care, 2021, 386–400. 10.31389/jltc.109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information . (2020). Pandemic experience in the long-term care sector: How does Canada compare with other countries? CIHI snapshot [research report]. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/covid-19-rapid-response-long-term-care-snapshot-en.pdf

- Clarke J. (2021). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in nursing and residential care facilities in Canada [research report]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2021001/article/00025-eng.htm

- Cohen-Mansfield J. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on long-term care facilities and their staff in Israel: Results from a mixed methods study. Journal of Nursing Management. 30(7), 2470–2478, 10.1111/jonm.13667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Herrera A., Zalakaín J., Lemmon E., Henderson D., Litwin C., Hsu A. T., Schmidt A. E., Arling G., Kruse F., Fernández J. L. (2020). Mortality associated with COVID-19 in care homes: International evidence. International Long-Term Care Policy Network, 2020. https://ltccovid.org/2020/04/12/mortality-associated-with-covid-19-outbreaks-in-care-homes-early-international-evidence/ [Google Scholar]

- Corpora M., Kelley M., Kasler K., Keppner A., van Haitsma K., Abbott K. M. (2021). “It’s been a whole new world”: Staff perceptions of implementing a person-centred communication intervention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 47(5), 9–13. https://doi:10.3928/00989134-20210407-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Mattei V., Perego G., Milano F., Mazzetti M., Taranto P., Di Pierro R., De Panfilis C., Madeddu F., Preti E. (2021). The “healthcare workers’ wellbeing (benessere operatori)” project: A picture of the mental health conditions of Italian healthcare workers during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 185267(10), Article 5267. 10.3390/ijerph18105267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohmen M. D., van den Eijnde C., Thielman C. L., Lindenberg J., Huijg J. M., Abma T. A. (2022). A narrative approach to care home staff’s experiences of the pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), Article 2106. 10.3390/ijerph19042106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks C. A., Squires J. E., Carleton H. L., Cummings G. G., Norton P. G. (2015). Who is looking after mom and dad? Unregulated workers in Canadian long-term care homes. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement, 34(1), 47–59. 10.1017/S0714980814000506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks C. A., Straus S. E., Flood C. M., Keefe J., Armstrong P., Donner G. J., Boscart V., Ducharme F., Silvius J. L., Wolfson M. C. (2020). Restoring trust: COVID-19 and the future of long-term care in Canada. Facets, 5(1), 651–691. https://doi:10.1139/facets-2020-0056 [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z., Lee Y. S., Kuo S., Intrator O., Foster A., Mor V. (2010). Do Medicaid wage pass-through payments increase nursing home staffing? Health Services Research, 45(3), 728–747. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01109.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher E., Cárdenas L., Kieffer E., Larson E. (2021). Reflections from the “forgotten front line”: A qualitative study of factors affecting wellbeing among long-term care workers in New York city during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geriatric Nursing, 42(6), 1408–1414. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freidus A., Shenk D. (2020). “It spread like wildfire”: Analyzing affect in the narratives of nursing home staff during a COVID-19 outbreak. Anthropology & Aging, 41(2), 199–206. https//doi:10.5195/aa.2020.312 [Google Scholar]

- Ghaleb Y., Lami F., Al Nsour M., Rashak H. A., Samy S., Khader Y. S., Al Serouri A., BahaaEldin H., Afifi S., Elfadul M., Ikram A., Akhtar H., Hussein A. M., Barkia A., Hakim H., Taha H. A., Hijjo Y., Kamal E., Ahmed A. Y., Hussein M. H. (2021). Mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers in the eastern mediterranean region: A multi-country study. [Supplemental material]. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 43(Supplement_3), iii34–iii42. 10.1093/pubmed/fdab321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson D. M., Greene J. (2020). Risk for severe COVID-19 illness among health care workers who work directly with patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(9), 2804–2806. 10.1007/s11606-020-05992-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel C., Hanna K., Marlow P., Cannon J., Tetlow H., Shenton J., Faulkner T., Rajagopal M., Mason S., Gabbay M. (2022). Guilt, tears and burnout—impact of UK care home restrictions on the mental well-being of staff, families and residents. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(7), 2191–2202, 10.1111/jan.15181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg N. (2020). Mental health of health-care workers in the COVID-19 era. Nature Reviews Nephrology, 16(8), 425–426. 10.1038/s41581-020-0314-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaei F., Smith P., Oudyk J., Potter G. G. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of nurses in British Columbia, Canada using trends analysis across three time points. Annals of Epidemiology, 62, 7–12. https://doi:10.1016/J.ANNEPIDEM.2021.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoedl M., Thonhofer N., Schoberer D. (2022). Burdens on and consequences for nursing home staff. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(8), 2495–2506, 10.1111/jan.15193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E. A., O’Connor R. C., Perry V. H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L., Ballard C., Christensen H., Cohen Silver R., Everall I., Ford T., John A., Kabir T., King K., Madan I., Michie S., Przybylski A. K., Shafran R., Sweeney A., Bullmore E. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560. https://doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H. F., Shannon S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi:10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung L., Yang S. C., Guo E., Sakamoto M., Mann J., Dunn S., Horne N. (2022). Staff experience of a Canadian long-term care home during a COVID-19 outbreak: A qualitative study. BMC Nursing, 21(1), 45–45. 10.1186/s12912-022-00823-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husky M. M., Villeneuve R., Teguo M. T., Alonso J., Bruffaerts R., Swendsen J., Amieva H. (2022). Nursing home workers' mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in France. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 23(7), 1095–1100, 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization . (2018). Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work [research report]. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/–-dgreports/–-dcomm/–-publ/documents/publication/wcms_633135.pdf

- Joanna Briggs Institute . (2016). Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual: 2016 edition. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL

- Kang L., Li Y., Hu S., Chen M., Yang C., Yang B. X., Wang Y., Hu J., Lai J., Ma X., Chen J., Guan L., Wang G., Ma H., Liu Z. (2020). The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(3), Article e14. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Q., Chan S. W. C., Kong Y., Fu J., Li W., Shen Q., Zhu J. (2021). Frontline nurses’ willingness to work during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(9), 3880–3893. 10.1111/jan.14989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzyzaniak N., Scott A. M., Bakhit M., Bryant A., Taylor M., del Mar C. (2021). Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the Australian residential aged care facility (Raf) workforce. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 38(3), 47–58. 10.37464/2020.383.490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamiani G., Borghi L., Argentero P. (2017). When healthcare professionals cannot do the right thing: A systematic review of moral distress and its correlates. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(1), 51–67. 10.1177/1359105315595120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont S., Brunero S., Perry L., Duffield C., Sibbritt D., Gallagher R., Nicholls R. (2017). ‘Mental health day’ sickness absence amongst nurses and midwives: Workplace, workforce, psychosocial and health characteristics. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(5), 1172–1181. 10.1111/jan.13212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langins M., Curry N., Lorenz-Dant K., Comas-Herrera A., Rajan S. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and long-term care: What can we learn from the first wave about how to protect care homes. Eurohealth, 26(2), 77–82. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/336303 [Google Scholar]

- Leontjevas R., Knippenberg I. A. H., Smalbrugge M., Plouvier A. O. A., Teunisse S., Bakker C., Koopmans R. T. C. M., Gerritsen D. L. (2021). Challenging behavior of nursing home residents during COVID-19 measures in The Netherlands. Aging & Mental Health, 25(7), 1314–1319. 10.1080/13607863.2020.1857695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leskovic L., Erjavec K., Leskovar R., Vukovic G. (2020). Burnout and job satisfaction of healthcare workers in Slovenian nursing homes in rural areas during the COVID-19 pandemic. Annuals of Agricultural & Environmental Medicine, 27(4), 664–671. 10.26444/aaem/128236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lethin C., Kenkmann A., Chiatti C., Christensen J., Backhouse T., Killett A., Fisher O., Malmgren Fänge A. (2021). Organizational Support Experiences of Care Home and Home Care Staff in Sweden, Italy, Germany and the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 9(6), 767–779. 10.3390/healthcare9060767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K. K. (2010). Scoping studies Advancing the methodology. Implementation science, 5(1), Article 69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightman N. (2022). Caring during the COVID-19 crisis: Intersectional exclusion of immigrant women health care aides in Canadian long-term care. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(4), 1343–1351. 10.1111/hsc.13541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomer L., Grabowski D. C., Yu H., Gandhi A. (2022). Association between nursing home staff turnover and infection control citations. Health Services Research, 57(2), 322–332. 10.1111/1475-6773.13877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín J., Padierna Á., Villanueva A., Quintana J. M. (2021). Evaluation of the mental health of care home staff in the Covid-19 era. What price did care home workers pay for standing by their patients? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 36(11), 1810–1819. 10.1002/gps.5602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-López J. Á., Lázaro-Pérez C., Gómez-Galán J. (2021). Burnout among direct-care workers in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A preventative and educational focus for sustainable workplaces. Sustainability, 13(5), Article 2782. https://doi:10.3390/SU13052782 [Google Scholar]

- McGilton K. S., Krassikova A., Boscart V., Sidani S., Iaboni A., Vellani S., Escrig-Pinol A. (2021). Nurse practitioners rising to the challenge during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in long-term care homes. The Gerontologist, 61(4), 615–623. 10.1093/geront/gnab030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller V. J., Fields N. L., Anderson K. A., Kusmaul N., Maxwell C. (2021). Nursing home social workers perceptions of preparedness and coping for COVID-19. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 76(4), e219–e224. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller A. E., Hafstad E. V., Himmels J. P. W., Smedslund G., Flottorp S., Stensland S. Ø., Stroobants S., Van de Velde S., Vist G. E. (2020). The mental health impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: A rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Research, 293, Article 113441. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyashanu M., Pfende F., Ekpenyong M. S. (2022). Triggers of mental health problems among frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in private care homes and domiciliary care agencies: Lived experiences of care workers in the Midlands region, UK. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(2), e370–e376. 10.1111/hsc.13204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (OECD) . (2021). Ageing and Long-term Care . https://www.oecd.org/fr/els/systemes-sante/long-term-care.htm

- Osman L. (2020). No easy fix for long-term care home problems highlighted by COVID-19. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/Canada/no-easy-fix-for-long-term-care-home-problems-highlighted-by-covid-19-1.4932175 [Google Scholar]

- Page M., McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T. C., Mulrow C. D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J. M., Akl E. A., Brennan S. E., Chou R., Glanville J., Grimshaw J. M., Hróbjartsson A., Lalu M. M., Li T., Loder E. W., Mayo-Wilson E., McDonald S., Whiting P. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Online), 372, Article n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., Giannakoulis V. G., Papoutsi E., Katsaounou P. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88(August 2020), 901–907. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pförtner T.-K., Pfaff H., Hower K. I. (2021). Will the demands by the Covid-19 pandemic increase the intent to quit the profession of long-term care managers? A repeated cross-sectional study in Germany. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 43(3), e431–e434. 10.1093/pubmed/fdab081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prados N., Jiménez García-Tizón S., Meléndez J. C. (2022). Sense of coherence and burnout in nursing home workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(1), 244–252. https://doi:10.1111/HSC.13397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabow M. W., Huang C.-H. S., Tucker R. O. (2021). Witnesses and victims both: Healthcare workers and grief in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 62(3), 647–656. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.01.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds K., Ceccarelli L., Pankratz L., Snider T., Tindall C., Omolola D., Feniuk C., Turenne-Maynard J. (2022). COVID-19 and the experiences and needs of staff and management working at the front lines of long-term care in central Canada. Cardiovascular Journal of Africa, 1, 6. 10.1017/S0714980821000696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riello M., Purgato M., Bove C., MacTaggart D., Rusconi E. (2020). Prevalence of post-traumatic symptomatology and anxiety among residential nursing and care home workers following the first COVID-19 outbreak in Northern Italy. Royal Society Open Science, 7200880(9), 200880, 10.1098/rsos.200880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romney M. (2020). Romney “patriot pay” plan would support America’s frontline workers. https://www.romney.senate.gov/romney-patriot-pay-plan-would-support-americas-frontline-workers/

- Rutten J. E. R., Backhaus R., Hamers J. P., Verbeek H. (2021). Working in a Dutch nursing home during the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences and lessons learned. Nursing Open, 9(6), 2710–2719. 10.1002/nop2.970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]