Abstract

In previous studies, we reported the isolation and preliminary characterization of a DNA ligase-encoding gene of Candida albicans. This gene (LIG4) is the structural and functional homologue of both yeast and human ligase IV, which is involved in nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) of DNA double-strand breaks. In the present study, we have shown that there are no other LIG4 homologues in C. albicans. In order to study the function of LIG4 in morphogenesis and virulence, we constructed gene deletions. LIG4 transcript levels were reduced in the heterozygote and were completely absent in null strains. Concomitantly, the heterozygote showed a pronounced defect in myceliation, which was slightly greater in the null strain. This was true with several solid and liquid media, such as Spider medium, medium 199, and 2% glucose–1% yeast extract–2% Bacto Peptone, at several pHs. Reintroduction of the wild-type allele into the null mutant partially restored the ability of cells to form hyphae. In agreement with the positive role of LIG4 in morphogenesis, we detected a significant rise in mRNA levels during the morphological transition. LIG4 is not essential for DNA replication or for the repair of DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation or UV light, indicating that these lesions are repaired primarily by homologous recombination. However, our data show that the NHEJ apparatus of C. albicans may control morphogenesis in this diploid organism. In addition, deletion of one or both copies of LIG4 resulted in attenuation of virulence in a murine model of candidiasis.

Candida albicans is an opportunistic pathogen that usually lives as a commensal in the healthy human host. Alterations in the balance between the commensal and the host, like those that occur in the immunocompromised patient, may trigger infection of the mucosal epithelia, followed by dissemination via the bloodstream and colonization of internal organs. As the major fungal pathogen of humans (40), C. albicans has been the focus of intense research. However, the study of its biology has been hindered by the fact that C. albicans is an obligate diploid (44), although recent studies have indicated that the organism may have some type of sexual cycle (22, 33). Following adherence of the organism to the mucosal epithelia of human tissues, invasion and disease progression seem to require a reversible conversion of yeast cells to a filamentous (hyphal) morphology (5, 40). Hence, numerous molecular studies of C. albicans have focused on genes required for filamentation; many of these genes are required for its virulence.

The yeast-hypha transition may be induced in vitro by a number of environmental signals (40), and this observation has been useful in screening for mutations that effect signaling and the regulation of filamentation. Most of the genes that are required for morphogenesis can be assigned to two independently regulated signal pathways, represented by the transcription factors Cph1p and Efg1p. The Cph1p pathway includes a number of mitogen-activated protein kinase proteins (Cek1p, Cst20p, and Hst7p) that convey starvation signals to Cph1p. This pathway is similar to the pseudohypha or mating pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (30). In fact, the C. albicans homologues were isolated by their ability to enhance pseudohyphal growth (CPH1) (31) or to complement both mating and pseudohyphal defects in S. cerevisiae (26, 27). C. albicans homozygotes with deletions of CPH1, HST7, or CST20 were defective in hypha formation in some media but were still induced to form hyphae by serum, an indication that an additional filamentation pathway exists (26, 31, 32, 34).

Efg1p is a member of the conserved class of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins. These proteins include StuA and Phd1 (Sok2), which regulate conidiophore morphogenesis in Aspergillus nidulans (36) and pseudohyphal growth in S. cerevisiae (19, 61), respectively. Overexpression of C. albicans EFG1 enhanced filamentous growth, whereas efg1 null mutants exhibited severe filamentation defects (32, 56). A efg1 cph1 null mutant did not germinate in serum and was avirulent in a murine model of candidiasis (32). Recent results indicate that Efg1p is a direct target of the catalytic subunit of a cyclic AMP-dependent kinase (Tpk2p) (55).

Two-component histidine kinases and response regulators have also been identified for C. albicans (6–10). Likewise, they seem to be required for the yeast-to-hyphal transition under certain growth conditions, and strains with deletions in these genes are attenuated or avirulent in murine systemic candidiasis (6, 8, 64). Their relationship to the Cph1p and Efg1p pathways is not known.

On the basis of population genetic studies (47), it is assumed that C. albicans reproduces primarily by clonal propagation. However, different isolates of C. albicans exhibit variability in heritable phenotypes, such as colony morphology (53), antigenic profiles (54), and electrophoretic karyotypes (25, 57, 59). Both mitotic recombination involving natural heterozygosity and chromosomal translocations, which are known to occur, could account for some of this variability. For instance, unequal crossing over between homologues in rRNA repeats contributes to the variation in the size of chromosome R (11, 23). However, the differential mobility of the two homologues of other pairs of chromosomes in other strains is not known. Recently, a new mechanism for the regulation of gene expression, consisting of changes in the chromosome copy number, has been described (25, 42). These examples provide a general hypothesis for the control of gene expression by chromosomal rearrangements.

We have recently cloned LIG4 from C. albicans (1). Like the yeast and human counterparts, Lig4p also appears to be involved in nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) of double-strand breaks (DSB) in C. albicans, since LIG4 is able to complement a lig4 mutant of S. cerevisiae (2). This illegitimate recombination process is able to produce novel arrangements of genes, as illustrated by its involvement in the generation of the antigen-binding repertoire in higher eukaryotes (49). Accordingly, NHEJ could well provide a prevalent recombination mechanism in an organism unable to create variability by sexual recombination, such as C. albicans, although, as stated above, mating in C. albicans has been reported. In addition, since irradiation or anticancer drugs are given to cancer patients infected with C. albicans, it is important to know how this organism responds to DNA-damaging agents and the pathways used to repair DNA DSB. In the current report, we present a phenotypic analysis of C. albicans lig4 disruptants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

The C. albicans strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. C. albicans 3153A is a protrotrophic strain previously used in our laboratory (1). Strains 1001 and 4918 have also been described previously (1, 2). Other strains used as controls in this study were kindly provided by G. Fink (CST20, HST7, and CPH1 null mutants) (32) and J. Ernst (EFG1 null mutant) (56). A diploid S. cerevisiae rad52/rad52 mutant, constructed by crossing W303 derivative haploid strains W839-5C and W839-11D (Table 1), was kindly provided by A. Aguilera (University of Sevilla). C. albicans cells were routinely grown in YPD medium (2% glucose, 1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone) at 28°C unless otherwise noted. Spider medium and medium 199 (M-199) (Gibco-BRL; adjusted to pH 7.5) plates were prepared as described by Gimeno et al. (18) and Ramon et al. (48), respectively. Lee's medium was prepared as described previously (28). Ura− auxotrophs were selected on medium containing 5′-fluoro-orotic acid (5′-FOA) (3, 15). Colony morphology on plates was inspected microscopically using a Nikon Optiphot microscope. To induce filamentation, cells of C. albicans were grown for 48 h at either 28 or 37°C. This culture was used to inoculate fresh YPD liquid medium prewarmed to 37°C. After 30 min, most cells had formed germ tubes, which continued to elongate during the next 60 to 90 min. Subsequently, the filaments produced yeast cells.

TABLE 1.

C. albicans strains used in this study

| Strain | Parent | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | |||

| 3153A | Prototrophic | CECT | |

| 1001 | Prototrophic | CECT | |

| 4918 | Prototrophic | R. Calderone | |

| SC5314 | Prototrophic | 15 | |

| CAF2 | SC5314 | Δura3::imm434/URA3 | 15 |

| CAI4 | CAF2 | Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434 | 15 |

| CEA1 | CAI4 | Like CAI4 but LIG4/lig4::hisG-URA3-hisG | This work |

| CEA1.5 | CEA1 | Like CAI4 but LIG4/lig4::hisG | This work |

| CEA2 | CEA1.5 | Like CAI4 but lig4::hisG-URA3-hisG/lig4::hisG | This work |

| CEA2.5 | CEA2 | Like CAI4 but lig4::hisG/lig4::hisG | This work |

| CEA3 | CEA2.5 | Like CEA3 but lig4::hisG/LIG4::URA3-hisG | This work |

| S. cerevisiae W839-5C × W839-11D | MATa/MATα ade2-1/ade2-1 can1-100/can1-100 his2-11,15/his2-11,15 leu2-3,112/leu2-3,112 trp1-1/trp1-1 ura3-1/ura3-1 rad52-8::TRP1/rad52-8::TRP1 | A. Aguilera |

Gene disruption.

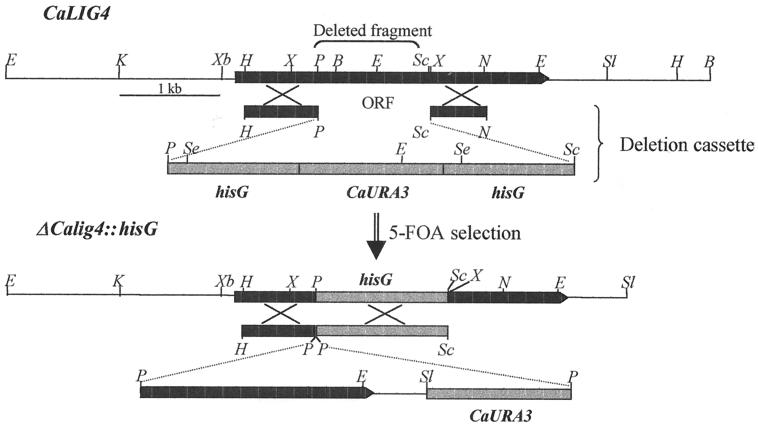

Sequential disruption of both alleles of LIG4 was performed as described by Fonzi and Irwin (15) using strain CAI4 (ura3). The C. albicans URA3 gene flanked by repeats of the Salmonella typhimurium hisG gene was used to disrupt LIG4, and Ura3+ transformants were isolated. Segregants that become Ura3− by recombination between the hisG repeats were selected by growing the transformants on agar plates containing 0.1% 5′-FOA and 0.2 mM uridine. The resulting Ura3− strain was then used to disrupt the second allele by transformation with the same cassette. The disruption cassette was prepared as follows. An XbaI/NsiI fragment containing most of LIG4 was subcloned into the pGEM-7Zf+ vector (Promega) and digested with both PstI and SacI to release a 1-kb fragment, which included the active site of the ligase (see Fig. 2). This fragment was replaced with a PstI/SacI fragment of hisG-URA3-hisG from plasmid pMB7 (15). Digestion of the resulting plasmid with HindIII and NsiI released the disruption cassette which, in turn, was used to transform strain CAI4 or the single-allele disruptant. The disruption of one or both alleles of LIG4 was confirmed by Southern blot hybridization (see Fig. 3A and B) and by PCR (see Fig. 3C). For the verification of gene disruption by PCR, oligonucleotides flanking the deleted region of LIG4 were used as primers. These were 5′-GTATACCAGAAGTAAGATGGC-3′, complementary to positions 562 to 583 (with position 1 corresponding to A from the translation initiation codon ATG), for the 5′ region and 5′-CAGGGTGCCTGCTCGAGTGTC-3′, complementary to positions 1791 to 1812 for the 3′ region on the complementary strand.

FIG. 2.

Restriction map of C. albicans (Ca) LIG4 and scheme showing the replacement of wild-type LIG4 (top [above arrow]) as well as the construction of the revertant allele (bottom [below arrow]). An internal PstI/SacI fragment from LIG4 was replaced with the hisG-URA3-hisG cassette. Following selection on 5′-FOA plates, URA3 and one copy of hisG were deleted in the LIG4/lig4 heterozygote before replacement of the second wild-type allele. Wild-type LIG4 was reintroduced into the null mutant lig4/lig4 (Ura3−) to construct the revertant, as indicated in the scheme (bottom). Abbreviations: B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; N, NsiI; P, PstI; Sc, SacI; Sl, SalI; X, XhoI; Xb, XbaI; Se, SceI.

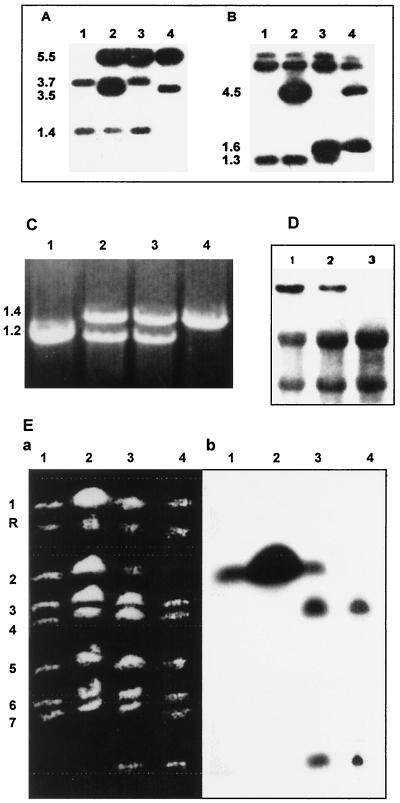

FIG. 3.

Analysis of LIG4 mutants. (A and B) Southern blots of LIG4 deletion mutants with the whole deletion cassette as a probe (Fig. 2, top). (A) Candida genomic DNA digested with EcoRI. Lane 1, parental strain CAI4 yields fragments of 1.4 and 3.7 kb. Lane 2, heterozygous LIG4/lig4::URA3 (single) disruptant (CEA1); note that, in addition to the bands from the wild-type allele, two new bands of 3.5 and 5.5 kb are present. Lane 3, heterozygous LIG4/lig4 strain after 5′-FOA selection (CEA1.5); the 3.5- and 5.5-kb bands are resolved into a new, 5.4-kb band. Lane 4, lig4::URA3/lig4 double disruptant (CEA2); note the 3.5- and 5.5-kb bands from the second disruption with hisG-URA3-hisG and the 5.4-kb fragment from the first allele disruption. (B) Like panel A, but digested with XhoI. Lane 1, parental strain CAI4 yields a 1.3-kb fragment and two large fragments. Lane 2, heterozygous LIG4/lig4::URA3 (CEA1); note that in addition to the bands arising from the wild-type allele, a new, 4.5-kb band indicates the insertion of the cassette in the other allele. Lane 3, heterozygous LIG4/lig4 strain after 5′-FOA selection (CEA1.5); The 4.5-kb band is reduced to a 1.6-kb fragment because of the loss of the URA3-hisG part of the cassette. Lane 4, lig4::URA3/lig4 double disruptant (CEA2). (C) Verification of LIG4 mutants and the revertant by PCR analysis. Shown in an agarose gel are PCR products obtained by amplification of genomic DNA from CAI4 (lane 1), the heterozygote (LIG4/lig4) (lane 2), the null mutant (lig4/lig4) (lane 4), and the revertant (lane 3) with the oligonucleotides indicated in Materials and Methods. (D) Top Northern analysis of LIG4 expression in wild-type CAI4 (lane 1), the heterozygote (LIG4/lig4) (CEA1) (lane 2), and the null strain (CEA2) (lane 3) with the XhoI/XhoI fragment as a probe. All the strains are Ura3+. (Bottom) rRNAs from the same samples stained with methylene blue. (E) Electrophoretic karyotypes of strains CAI4 (lane 1), CEA1 (LIG4/lig4::URA3) before (lane 2) and after (lane 3) treatment with SceI, and CEA2 (lig4::URA3/lig4) after treatment with SceI (lane 4), as shown by ethidium bromide staining (a) and Southern blot hybridization with the whole disruption cassette as a probe (b).

In order to obtain a reconstituted strain with one LIG4 allele, we first constructed a modified pMB7 in which one copy of hisG had been eliminated by treatment with XbaI followed by religation. Then, a 2.2-kb HindIII/SalI fragment from pEA5, containing most of the LIG4 open reading frame (ORF), was subcloned in the HindIII/SalI site of the modified pMB7 to generate pMB7-LIG4-URA3-hisG (see Fig. 2). The LIG4-URA3-hisG cassette was released by treatment with HindIII/SacI and used to transform the Ura3− lig4 null mutant. The transformants were selected in synthetic complete minimal medium lacking uridine, and integration was verified by Southern blotting (data not shown) and PCR (see Fig. 3C) using the primers described above.

DNA extraction and analysis.

Standard techniques were routinely used for DNA manipulations (52). Genomic DNA was prepared from protoplasts obtained by incubation of cells with Zymolyase stabilized with 1 M sorbitol and lysed in 50 mM Tris–50 mM EDTA–0.6% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). For Southern analysis, genomic DNA was digested with restriction enzymes, electrophoresed in an agarose gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with the gene fragment (see Fig. 2) KpnI-XbaI at high stringency (6× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate]–5× Denhart's solution–0.5% SDS for 12 h at 65°C). Following hybridization, the nitrocellulose filter was washed (65°C in 2× SSC–0.5% SDS and then 0.2× SSC–0.5% SDS). Xomat X-AR film (Kodak) was used to expose blots. Northern analysis was carried out as described previously (2).

Sample preparation for electrophoresis.

An exponentially growing culture of C. albicans (0.1 ml) was used to inoculate 10 ml of YPD medium. The culture was maintained in a rotary shaker at 30°C for 48 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with 50 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), and resuspended in 1 ml of CPES (40 mM citric acid, 120 mM sodium phosphate, 20 mM EDTA [pH 8], 1.2 M sorbitol, 5 mM dithiothreitol) supplemented with 0.2 mg of Zymolyase 20000. One milliliter of CPE (like CPES but lacking sorbitol and dithiothreitol) containing 1% low-melting-point agarose at 50°C was added and gently mixed. Aliquots of 200 μl were then transferred into a sample mold and kept at −20°C. Upon solidification, plugs were transferred to test tubes, supplemented with 6 ml of CPE, and incubated at 30°C for 4 h. CPE was replaced with 5 ml of TESP (1 M Tris-HCl, 0.5 M EDTA, 2% SDS) containing 1 mg of proteinase K per ml, and the samples were incubated overnight at 50°C. The samples were then washed three times with TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA) at 50°C and six times at room temperature. The plugs were stored at 4°C in 50 mM EDTA (pH 8). The gel containing C. albicans chromosomes was run in 0.6% agarose for 24 h at 80 V with a 120- to 300-s linear ramp and then for 48 h at 80 V with a 420- to 900-s linear ramp in a rotating gel electrophoresis apparatus.

UV and MMS treatments.

For UV irradiation, exponentially growing cells were resuspended in sterile water and exposed to UV radiation at 50 J/m2 (Stratalinker; Stratagene). Aliquots of serial fivefold dilutions of cells were spotted onto YPD plates and incubated for 36 h at 30°C to measure the survival of UV-treated cells. For treatment with the radiomimetic compound methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), fivefold cell dilutions were seeded onto YPD plates containing 0.0025 to 0.0075% (wt/vol) MMS and incubated as described previously (58).

Murine model of candidiasis.

BALB/c male mice were infected with 106 yeast cells via the lateral tail vein according to published procedures (6, 8). Four groups of mice were infected with LIG4 parental (CAF2), heterozygote (CEA1), null (CEA2), or reconstituted (CEA3) strains. Five mice from each of the four groups were sacrificed daily for the first 72 h postinfection, and sections of the infected kidneys and livers from each infected animal were prepared and stained using Gomori's methenamine-silver nitrate reagent. The number of infectious foci at 24 h postinfection in kidney sections from animals infected with each strain was determined. An additional 10 animals from each group were monitored daily for a total of 21 days, and moribund animals were sacrificed.

RESULTS

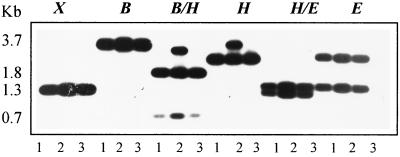

Number of LIG4 homologues.

Southern hybridization was done to determine if C. albicans has other homologues of LIG4. As indicated in Fig. 1, total genomic DNAs from strains 1001 (lane 1), 3153A (lane 2), and 4918 (lane 3) were cut with different restriction enzymes and probed with an internal XhoI/XhoI fragment of the LIG4 gene (Fig. 2). The restricted fragments obtained were those expected for a single gene, based upon the restriction map (Fig. 2, top), except for fragments generated by digestion with HindIII. This enzyme yielded a single band from strains 1001 and 4918 and two bands from strain 3153A, suggesting allelic differences in LIG4 for that strain. Our cloned gene is represented by the largest HindIII fragment of the two derived from strain 3153A. The other copy of LIG4 from this strain and both copies from strains 1001 and 4918 carry an additional HindIII site very close to the 3′ end of the ORF. This finding was confirmed when DNA was cut with a mixture of HindIII and BamHI. It should be noted that digestion with both HindIII and EcoRI yielded two bands for all strains. On the basis of the size of the smaller fragment, we have localized the new HindIII site several base pairs downstream from the EcoRI site located at the 3′ end of the ORF (Fig. 2, top). Other studies have indicated that neither of the CAI4 LIG4 alleles carries this HindIII site (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Determination of LIG4 homologues in C. albicans. Genomic DNAs from strains 1001 (lanes 1), 3153A (lanes 2), and 4918 (lanes 3) were cut with the indicated restriction enzymes, electrophoresed, and subjected to Southern hybridization using the XhoI/XhoI internal fragment of C. albicans LIG4 (see Fig. 2). Abbreviations: B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; X, XhoI. Size markers are indicated.

We conclude that there are no additional homologues of LIG4 in the C. albicans genome. The presence of a new band in HindIII digests must be attributed to a restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). RFLPs have been demonstrated for many genes in C. albicans. With LIG4, the presence of a restriction site dimorphism of HindIII provides a potential marker to distinguish chromosomal homologues in some strains.

Disruption of LIG4.

C. albicans heterozygotes were made by disruption of LIG4 in strain CAI4 (ura3/ura3) (Fig. 3A and B). The disruption consisted of a 1-kb deletion of the LIG4 ORF, including the putative active site of the protein (Fig. 2, top). Both N- and C-terminal regions of the ligase as well as the entire promoter and terminator were left intact to ensure that other proximal loci were not affected by the disruption. The heterozygote was confirmed by Southern blot analysis before (CEA1) the loss of the hisG-URA3 fragment by selection on 5′-FOA plates (Fig. 3A and 3B, lanes 2) using the whole deletion cassette as a probe. Also, Northern analysis indicated that the amount of the LIG4 transcript was reduced compared to that in control cells (CAI4) (Fig. 3D, compare lanes 1 and 2). The decrease in the amount of message was independent of the presence or absence of the URA3 gene (data not shown).

The growth of strain CEA1 on 5′-FOA-containing agar allowed us to select for strains that had lost URA3 and one copy of hisG (CEA1.5), as demonstrated by Southern hybridization (Fig. 3A and 3B, lanes 3) and PCR (Fig. 3C, lane 2). Strain CEA1.5 was then transformed with the same disruption cassette in order to construct a strain with deletions of both copies of LIG4. The lig4/lig4::URA3 double disruptant (CEA2) was confirmed by Southern hybridization (Fig. 3A and 3B, lanes 4). As expected, the LIG4 message was absent in the double disruptant (Fig. 3D, lane 3). Again, growth on 5′-FOA-containing agar resulted in the generation of a null Ura3− lig4/lig4 strain (CEA2.5) (Fig. 3C, lane 4).

The chromosomal profile of strain CEA1 cells was similar to that of wild-type cells (CAI4), as demonstrated by both ethidium bromide staining and Southern hybridization (Fig. 3Ea and b, lanes 1 and 2). Also, when the chromosomal preparation of CEA1 was treated with SceI, one copy of chromosome 2 migrated as in wild-type cells, but the second chromosome split into two fragments, one migrating in a manner similar to that of chromosome 3 and the other migrating as a smaller fragment (Fig. 3E, panels a and b, compare lanes 1 and 2 to lane 3). Since the chromosomal karyotype of strain CAI4 is similar to that of a reference strain (1006) (15), we calculated that the sizes of the two split products of chromosome 2 were 1,900 and 400 kbp, respectively. As expected, when a chromosomal preparation of strain CEA2 was treated with SceI, no trace of chromosome 2 was detected by ethidium bromide staining, but the 400-kbp fragment was evident (Fig. 3E, panel a, lane 4). In addition, no hybridization with chromosome 2 was seen, and only the two split products were detected in Southern blots (Fig. 3E, panel b, lanes 4). It should be noted that the SceI restriction site is found in the hisG gene and not in the C. albicans CAI4 genome.

In order to be sure that the phenotype of these strains was a consequence of the absence of LIG4, LIG4-URA3 (from C. albicans) was reintegrated into the genome of CEA2.5 (a Ura3− lig4/lig4 homozygote) to yield a lig4/LIG4::URA3 heterozygote revertant (CEA3) (Fig. 2, middle). It should be noted that LIG4 was reintegrated at its own locus. This construct was confirmed by PCR (Fig. 3C) and Southern blot analysis (data not shown). Also, the karyotype of CEA3 (revertant) was similar to that of the null strain (CEA2). As expected from the presence of one copy of hisG in each copy of chromosome 2 (Fig. 2), only the two split products derived from this chromosome (Fig. 3E, panels a and b, lanes 4) were detected following treatment with SceI (data not shown).

Effect of C. albicans LIG4 disruption on morphogenesis.

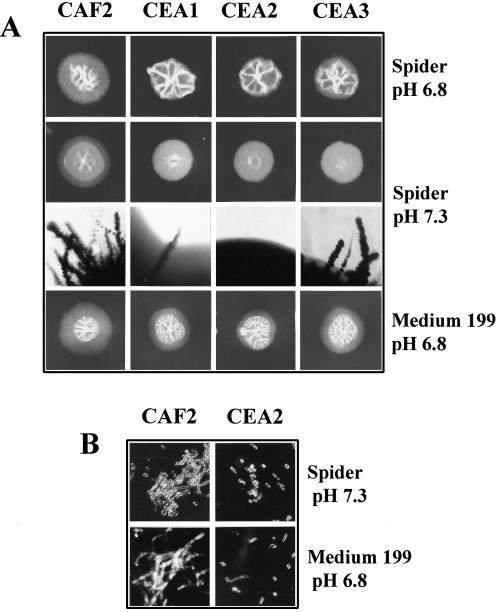

In order to determine whether the absence of Lig4p affects germination, wild-type cells (CAF2), single- and double-disruption strains (CEA1 and CEA2), and the reconstituted strain (CEA3) were grown on Spider agar at pHs 6.8 and 7.3. For comparison, we analyzed in parallel a number of deletion strains known to be affected in filamentation. All the strains tested carried one copy of URA3, since it has been reported that the absence of URA3 negatively affects the capacity of some strains of C. albicans, including SC5314, to form filaments on solid media (26, 27). As shown in Fig. 4A, at pH 6.8, filamentation of CEA2 was negligible compared to that of CAF2, which produced colonies whose periphery was composed of hyphal filaments. Strain CEA1 behaved in a manner similar to that of strain CEA2. Curiously, CEA3, generated by reintroduction of LIG4 into the null strain CEA2, produced more peripheral filaments than CEA1, although still much less than CAF2. This result suggests that the cloned gene, derived from strain 655 (20), may be more active than its counterpart present in heterozygous CEA1 derived from CAI4. At pH 7.3, the behavior of all strains was similar, although the ability of mutant strains to form filaments was decreased compared to that of CAF2 (Fig. 4A, row 2). This observation was verified by a microscopic comparison of the edges of the colonies (Fig. 4A, row 3), which clearly showed that although CEA1 was similar to CEA2, reintroduction of the wild-type allele into the latter (CEA3) resulted in a significant development of radial filaments (Fig. 4A, row 3). At a slightly higher pH (7.36), colonies of CEA2 were smoother than they were at pH 7.3. Again, only CAF2 formed filaments at pH 7.36 (data not shown). As expected, strains with deletions of cph1, hst7, cst20, and efg1 were unable to form filaments under the above-mentioned conditions (data not shown). Myceliation of all the strains, including CAF2, improved when they were grown on YPD plates, but again, strain CEA2 was defective compared to CAF2 (data not shown). It should be mentioned that control strains for cph1, hst7, and cst20 but not efg1 formed filaments under these conditions (data not shown). When we measured filamentation with M-199 at pH 6.8, we obtained similar results; i.e., myceliation of the null mutant CEA2 was significantly decreased compared to that of the wild type, whereas filamentation of CEA1 and CEA3 was intermediate but closer to that of CEA2 (Fig. 4A, row 4). Similar results were obtained at pH 7.5 (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Effect of LIG4 mutations on hyphal development. The indicated strains were grown on or in each medium for 5 days (solid media, panel A) or 36 h (liquid media, panel B). (A) Growth of strains in Spider medium at pH 6.8 (row 1) or pH 7.3 (row 2). The edges of colonies from each strain in Spider medium at pH 7.3 were photographed (magnification, ∼×15) (row 3). The growth of each strain on M-199 agar is also shown (row 4). (B) Microscopic growth of parental strain (CAF2) and CEA2 (null mutant) in liquid Spider medium and M-199 at 30°C. Pictures were taken with a Normarski objective (magnification, ∼×27).

Impairment of myceliation following disruption of LIG4 was also observed in M-199 at pH 6.8 (Fig. 4B). Although all the strains were able to form hyphae in this medium, the percentage of yeast cells was significantly higher for CEA2 than for CAF2. The same general behavior was seen with Spider medium, although the morphology of the strains was different (Fig. 4B). Taken together, these data indicate that Lig4p is required for hyphal growth in C. albicans.

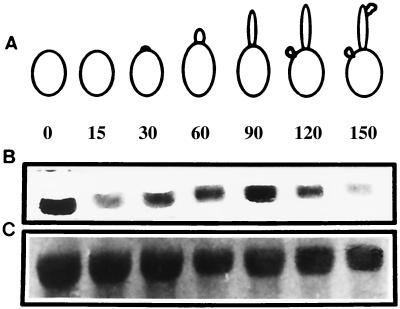

Expression of LIG4 during morphogenesis.

Previously, we showed that the transcription of LIG4 is cell cycle regulated (2). On the other hand, the current studies indicate that, at least under several conditions, the absence of LIG4 impairs or even prevents myceliation. In order to determine if the expression of LIG4 is affected during germination, we performed Northern analysis. Germ tube formation in C. albicans can be induced by a number of factors, including carbohydrates, amino acids, salts, serum, pH, and temperatures of >30°C (40). For our studies, we induced germination by transferring cells grown for 48 h to fresh medium (YPD) prewarmed to 37°C (Fig. 5). In order to avoid possible effects of nonspecific heat shock-induced transcription, cells were grown in YPD at both 28 and 37°C. Upon transfer of the cells to fresh medium at 37°C, samples were collected at intervals, total RNA was obtained, and the relative levels of abundance of specific mRNAs were assessed by Northern analysis. Cells grown at 28°C contained detectable levels of the LIG4 transcript. Fifteen minutes after the transfer to 37°C, a significant reduction in the levels of the LIG4 transcript was observed. Germ tube extension (60 to 90 min) coincided with a significant increase in LIG4 mRNA levels. After 90 min, yeast cells formed by budding or fragmentation and, correspondingly, the amounts of the transcript slightly decreased. The pattern was similar for cells grown at 37°C, except that the initial sample (0 min) contained smaller amounts of message (data not shown). The reduction in the levels of message detected at 15 min after the transfer of the cells from 28 to 37°C may be explained by the fact that the transcription of LIG4 is down regulated during the DNA replication period of the budding cycle (S phase) (2). Under myceliation conditions, this 15- to 30-min window could well correspond to a DNA replication period that precedes germ tube formation. In summary, these results agree with the behavior of the lig4 mutants, indicating again that the expression of LIG4 is temporally associated with myceliation.

FIG. 5.

Northern analysis of the LIG4 transcript during the induction of germination. Cells from C. albicans 3153A grown in YPD medium for 2 days at 28°C were transferred to prewarmed YPD medium and incubated at 37°C. Samples were taken at the indicated times (minutes). (A) Schematic representation of the germination process. (B) Northern analysis of the samples shown in panel A with the XhoI/XhoI fragment as a probe (Fig. 2). (C) 23S rRNA from the same samples stained with methylene blue for quantification purposes.

LIG4-dependent recombination pathway in DNA repair.

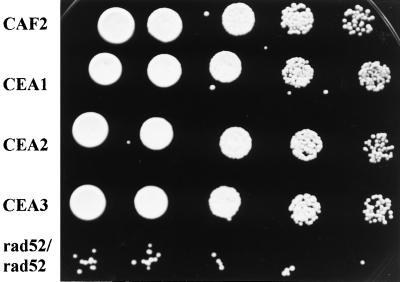

In S. cerevisiae, the RAD52 epistasis group of genes is used to repair radiation-induced DNA DSB primarily by homologous recombination (16). When this pathway is nonfunctional, as in rad52 mutants, cells use the alternative NHEJ pathway for DNA repair, involving Lig4p (58, 63). In order to determine the relative importance of the NHEJ pathway in C. albicans, we treated wild-type cells and single and double lig4 disruptants with UV or the radiomimetic compound MMS. As shown in Fig. 6, disruption of one or both copies of LIG4 did not influence the sensitivity of C. albicans cells to 0.005% MMS. In contrast, most cells of an S. cerevisiae rad52 mutant were killed under the same conditions. Likewise, at 0.0075% MMS, we obtained similar results for C. albicans, while the S. cerevisiae rad52 mutant did not grow (data not shown). As expected, LIG4 mutations did not affect the sensitivity of the corresponding strains to UV treatment (data not shown). We conclude that, as shown for S. cerevisiae, C. albicans possesses an additional recombination pathway that is involved in the repair of single-strand breaks and DSB, probably by homologous recombination, and that operates under most circumstances.

FIG. 6.

Sensitivities of C. albicans lig4 and S. cerevisiae rad52/rad52 mutants to 0.005% MMS (for details, see the text). Left to right, growth at fivefold dilutions.

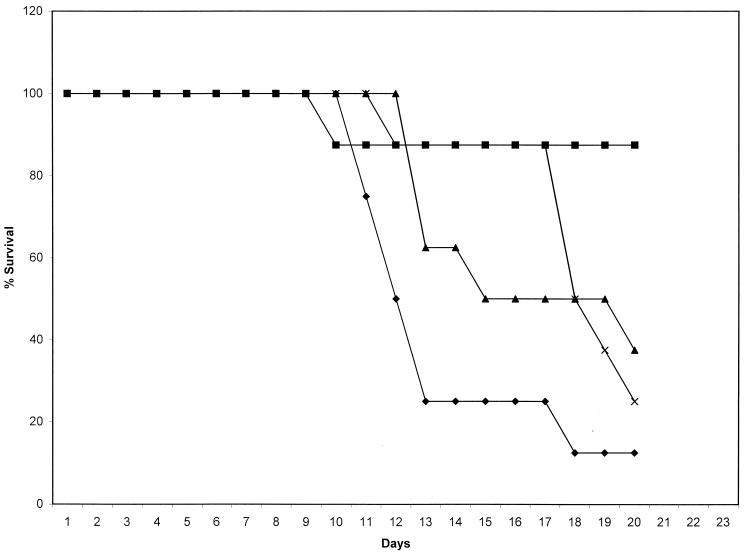

Animal studies.

We used a hematogenously disseminated murine model of candidiasis to measure the virulence of C. albicans strains lacking a single copy or both copies of LIG4. All strains used in the animal studies had a single copy of URA3+. Animals were infected intravenously via the tail vein, and morbidity was measured daily for 21 days. Prior to the animal studies, the generation time for each strain was determined, and all strains appeared to be similar. The data in Fig. 7 show that mice infected with CEA2 (lig4/lig4), CEA1 (LIG4/lig4), or CEA3 (lig4/LIG4) survived longer than those infected with wild-type (CAF2) cells. The histopathology at 24 h postinfection of the kidneys (Fig. 8) and of the liver (data not shown) from infected animals revealed more hyphal elements in CAF2-infected animals than in animals infected with the other strains. Also, infectious foci in kidneys from animals infected with each strain were higher with the CAF2 strain than with the single- or double-disruption strains (infectious foci per low-power-field: CAF2, 5.6; CEA1, 2.7; CEA2, 0.2; CEA3, 2.5). The hyphae from all infected animals, appeared to be similar. At 48 and 72 h, similar results were obtained (data not shown). These data indicate that single- and double-allele deletions of LIG4 attenuate the virulence of the organism.

FIG. 7.

Survival of mice following infection with C. albicans Δlig4 mutants (CEA1 [▴], CEA2 [■], and CEA3 [×]) and parental strain CAF2 (⧫). Moribund animals were monitored daily for 21 days.

FIG. 8.

Histological presentation of kidneys obtained from mice 24 h after infection with C. albicans CAF2 (A), CEA1 (B), CEA2 (C), and CEA3 (D). Original magnification, ×150. Sections were stained with Gomori's methenamine-silver nitrate.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that LIG4 influences morphogenesis in C. albicans under the conditions tested and that strains with deletions of one or both alleles of LIG4 are attenuated in their virulence. As shown for both yeast and human Lig4p, C. albicans Lig4p appears to be involved in NHEJ of DSB, since the expression of C. albicans LIG4 complements the NHEJ defect of a lig4 deletant of S. cerevisiae, as determined with a plasmid religation assay (2). Little is known about the physiological meaning of NHEJ in yeast. S. cerevisiae LIG4 is not essential, and the only reported phenotype of homozygous lig4 mutant diploids is that they sporulate less efficiently than isogenic wild-type cells and show retarded progression through meiotic prophase I and a higher proportion of tetrads with only three viable spores. Thus, the presence of Lig4p appears to ensure efficient meiosis in S. cerevisiae (50). However, the involvement of Lig4p in other processes is unknown.

Thus far, there are no reports of genes involved in DSB repair in C. albicans by any of the pathways described for S. cerevisiae (4, 41); one could expect the presence of homologues of the RAD52 epistasis group, Ku and Sir proteins, all of which are conserved, as is our ligase. In fact, C. albicans SIR2 recently has been cloned (43), and we have cloned a homologue of RAD52 (unpublished results). In addition, RAD6 has been recently shown to protect C. albicans cells from UV damage (29). Our present results indicate that the disruption of LIG4 does not lead to marked sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents, such as UV, which produces thymine dimers, or the radiomimetic compound MMS which, in addition to 3-methyladenine adducts, also produces DSB (38, 51). It follows that, as shown for S. cerevisiae, DSB in C. albicans are repaired primarily by homologous recombination and that LIG4 is not essential for the latter process. However, recent results obtained with diploid cells from S. cerevisiae have indicated that a RAD52-independent pathway, most probably NHEJ, repairs extensively damaged chromosomes (39). Construction of rad52 mutants in a lig4 background will help us to evaluate in detail the role of lig4 in C. albicans.

The presence of LIG4 appears to favor hyphal development. Thus, mutants with deletions of both copies of this gene exhibited significantly reduced mycelial growth compared to wild-type cells under a variety of conditions, including minimal media, such as Spider medium and M-199, and rich media, such as YPD or YPD plus serum (unpublished results). In agreement with the role of LIG4 in hyphal growth, we have demonstrated induction of LIG4 expression during temperature-induced germination and down regulation of mRNA levels during the reformation of yeast cells.

The extent of myceliation of the lig4 mutants tested was also pH dependent. For instance, deletion of one allele caused an almost complete block of myceliation on Spider agar plates at pHs higher than 7. However, at pH 6.8, both the heterozygote (CEA1) and the null mutant (CEA2) exhibited some myceliation, although much less than CAF2. This result is not surprising, since pH controls the differential expression of several genes that affect morphogenesis in C. albicans, including PRR1 and PRR2; these are the respective homologues of palF and pacC, two well-characterized components of the pH response pathway in A. nidulans (45, 48). Although we have not analyzed whether C. albicans LIG4 expression is pH dependent, we have found two copies of the core consensus PacC binding site of A. nidulans (5′-GCCAAG-3′ (13) upstream of C. albicans LIG4. However, the two copies of the PacC recognition site found in the 5′ regulatory region of PHR1 are not required for its pH-dependent expression (48). More interesting is the fact that reconstituted strain CEA3 myceliated more than the original heterozygote, CEA2, under some conditions, suggesting that different alleles could provide different levels of ligase activity. This notion is also supported by our preliminary observations on the isolation of two kinds of LIG4/lig4 heterozygotes, which vary in their ability to form hyphae (data not shown). The existence of natural heterozygosity in C. albicans was postulated by Whelan et al. (62) and is well documented for auxotrophic markers (59). It is possible that in addition to heterozygosity, gene polymorphisms may be quite common in C. albicans and may represent the RFLP patterns observed for some genes, including LIG4, perhaps an indication of additional differences between alleles conserved in natural populations. It should be noted that polymorphisms in coding or regulatory sequences are likely to have functional consequences. However, while both the heterozygote (CEA1) and the revertant (CEA3) differed in their degree of filamentation, this difference was not reflected in virulence; in fact, CEA3 appeared to be somewhat less virulent than CEA1, even though the former produced more mycelia in vitro.

How can LIG4 regulate a morphological transition in C. albicans? One possibility is that the effect of Lig4p on morphogenesis is related to gene silencing. In S. cerevisiae, there seems to be an association between silencing factors (SIR) and DNA repair mediated by Lig4p (24, 60). On the other hand, disruption of a SIR2-like gene in C. albicans causes a higher frequency of switching and a higher tendency toward hyphal or pseudohyphal growth (43). It has been recently reported that under normal conditions, Sir proteins residing at S. cerevisiae telomeres relocate in response to induced DNA damage, a fact that transiently causes a moderate derepression of telomere-silenced markers (35, 37). In this scenario, one could speculate that, when the lesions are not readily sealed, as might occur in the absence of Lig4p, Sir proteins could remain for longer periods at the sites of damage; they could cause more prolonged derepression of telomeric and/or subtelomeric genes, some of which could be involved in morphogenesis. Thus, Lig4p and Sir2p could play opposite roles in morphogenesis, which might indicate that whereas the absence of the former causes moderate and transient derepression of an otherwise small set of genes, the absence of the latter may relieve from telomere silencing a much larger number of genes. Interestingly, Rad6p, which represses yeast-hypha morphogenesis in C. albicans (29), also plays a role in postreplicative DNA repair, chromatin organization, and gene silencing in S. cerevisiae (21, 46). However, the role of Rad6p in morphogenesis is likely executed through its participation in the ubiquitination-mediated protein degradation pathway (29).

Another possibility is that, on the basis of its role in NHEJ, LIG4 is necessary for chromosome stability in C. albicans, a characteristic that also appears to be controlled by SIR2 (43). In fact, recent studies have concluded that the NHEJ pathway of DNA repair is a crucial caretaker of the mammalian genome, since null mutants with mutations in several components of the pathway, including Ku80, XRCC4, and DNA ligase IV, exhibit genomic instability as well as increased chromosomal fragmentation and nonreciprocal translocations (12, 14, 17). With LIG4 of C. albicans, controlled chromosomal rearrangements underlying phenotypic changes might generate endogenous, environmentally independent variation that should be advantageous for C. albicans. The Lig4p-dependent chromosomal alterations underlying the subsequent phenotypic changes, i.e., switching or myceliation, should be reversible. Theoretically, this is not a problem, since the initial state could be reached by homologous recombination using the unaltered copy of the corresponding chromosome. In order to gain insight into this possibility, we are currently carrying out a detailed karyotypic analysis of lig4 mutants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Leocadia Franco for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Fondo de Investigaciones Santarias de la Seguridad Social (grant 96/1646), Junta de Extremadura (IPR98031), and FEDER (IDF97-1173) and by NIH grants AI47047 and AI35097 to R.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andaluz E, Larriba G, Calderone R. A Candida albicans gene encoding a DNA ligase. Yeast. 1996;12:893–898. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199607)12:9%3C893::AID-YEA973%3E3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andaluz E, Ciudad A, Rubio Coque J, Calderone R, Larriba G. Cell cycle regulation of a DNA ligase-encoding gene (CaLIG4) from Candida albicans. Yeast. 1999;15:1199–1210. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19990915)15:12<1199::AID-YEA447>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeke J D, LaCroute F, Fink G R. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5-phosphate carboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;197:345–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00330984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boulton S J, Jackson S P. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ku70 potentiates illegitimate DNA double-strand repair and serves as a barrier to error-prone DNA repair pathways. EMBO J. 1996;15:5093–5103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calderone R, Braun P. Adherence and receptor relationships of Candida albicans. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:1–20. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.1.1-20.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calera J A, Zhao X-J, Calderone R. Defective hyphal development and avirulence caused by a deletion of the SSK1 response regulator gene in Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 2000;68:518–525. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.518-525.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calera J A, Calderone R. Flocculation of hyphae is associated with a deletion in the putative CaHK1 two-component histidine kinase gene from Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1999;145:1431–1442. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calera J A, Zhao X-J, DeBernardis F, Sheridan M, Calderone R. Avirulence of Candida albicans CaHK1 mutants in a murine model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4280–4284. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4280-4284.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calera J A, Calderone R. Identification of a putative response regulator two-component phosphorelay gene (CaSSK1) from Candida albicans. Yeast. 1999;15:1243–1254. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19990915)15:12<1243::AID-YEA449>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calera J A, Calderone R. Histidine kinases, two-component signal transduction proteins of Candida albicans and the pathogenesis of candidiasis. Mycoses. 1999;42(Suppl. 2):49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu W S, Magee B B, Magee P T. Construction of an SfiI macrorestriction map of the Candida albicans genome. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6637–6651. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6637-6651.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeFilippantonio M J, Zhu J, Chen H T, Meffre E, Nussenzweig M C, Max E E, Reid T, Nussenzweig A. DNA repair protein Ku80 suppresses chromosomal aberrations and malignant transformation. Nature. 2000;404:510–514. doi: 10.1038/35006670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espeso E A, Tilbum J, Sanchez-Pulido L, Brown C V, Valencia H N, Arst H N, Penalva M A. Specific DNA recognition by the Aspergillus nidulans three finger transcription factor, PacC. J Mol Biol. 1997;274:466–480. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferguson D O, Sekiguchi J M, Chang S, Frank K M, Gao Y, DePinho R A, Alt F W. The nonhomologous end-joining pathway of DNA repair is required for genomic stability and the suppression of translocations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6630–6633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110152897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fonzi W A, Irwin M Y. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics. 1993;134:717–728. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedberg E C, Walker G C, Sided W. DNA repair and mutagenesis. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao Y, Ferguson D O, Xie W, Manis J P, Sekiguchi J, Frank K M, Chaudhuri J, Horner J, DePinho R A, Alt F W. Interplay of p53 and DNA-repair protein XRCC4 in tumorigenesis, genome stability and development. Nature. 2000;404:897–900. doi: 10.1038/35009138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gimeno C J, Ljungdahl P O, Styles C A, Fink G R. Unipolar cell divisions in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae lead to filamentous growth: regulation by starvation and RAS. Cell. 1992;68:1077–1090. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90079-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gimeno C J, Fink G R. Induction of pseudohyphal growth by overexpression of PHD1, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene related to transcriptional regulators of fungal development. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2100–2112. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goshborn A K, Grindle S M, Scherer S. Gene isolation by complementation in Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1992;60:876–884. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.876-884.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang H, Kahana A, Gottschling D E, Prakash L, Liebman S. The ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Rad6 (Ubc2) is required for silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6693–6699. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hull C M, Raisner R M, Johnson A D. Evidence for mating of the “asexual” yeast in a mammalian host. Science. 2000;289:307–310. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwaguchi S I, Homma M, Tanaka K. Variation in the electrophoretic karyotype analyzed by the assignment of DNA probes in Candida albicans. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:2433–2442. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-12-2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson S P. Silencing and DNA repair connect. Nature. 1997;388:829–830. doi: 10.1038/42136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janbon G, Sherman F, Rustchenko E. Monosomy of a specific chromosome determines l-sorbose utilization: a novel regulatory mechanism in Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5150–5155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Köhler J R, Fink G R. Candida albicans strains heterozygous and homozygous for mutations in mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling components have defects in hyphal development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13223–13228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leberer E, Harcus D, Broadbent I D, Clark K L, Dignard D, Ziegelbauer K, Schmidt A, Gow N A R, Brown A J P, Thomas D Y. Signal transduction through homologs of the Ste20 and Ste7p protein kinases can trigger hyphal formation in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13217–13222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee K L, Buckley H R, Campbell C C. An amino acid liquid synthetic medium for the development of mycelial and yeast forms of Candida albicans. Sabouraudia. 1975;13:148–153. doi: 10.1080/00362177585190271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leng P, Sudbery P E, Brown A J P. Rad6p represses yeast-hypha morphogenesis in the human pathogen Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1264–1275. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu H, Styles C A, Fink G R. Elements of the yeast pheromone response pathway required for filamentous growth of diploids. Science. 1993;262:1741–1744. doi: 10.1126/science.8259520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu H, Köhler J, Fink G R. Suppression of hyphal formation in Candida albicans by mutation of a STE12 homolog. Science. 1994;266:1723–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.7992058. . (Erratum, 267:17, 1995.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lo H J, Köhler J R, DiDomenico B, Loebenberg D, Cacciapuoti A, Fink G R. Nonfilamentous Candida albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell. 1997;90:939–949. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80358-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magee B B, Magee P T. Induction of mating in Candida albicans by construction of MTLa and MTLα strains. Science. 2000;289:310–313. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magee P T. Which came first, the hypha or the yeast? Science. 1997;277:52–53. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin S G, Laroche T, Suka N, Grunstein M, Gasser S M. Relocalization of telomeric Ku and SIR proteins in response to DNA strand breaks in yeast. Cell. 1999;97:621–633. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80773-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller K Y, Wu J, Miller B L. StuA is required for cell pattern formation in Aspergillus. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1770–1782. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mills K D, Sinclair D A, Guarente L. MEC-1-dependent redistribution of the Sir3 silencing protein from telomeres to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell. 1999;97:609–620. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitchel R E, Morrison D P. Inducible DNA-repair systems in yeast: competition for lesions. Mutat Res. 1987;183:149–159. doi: 10.1016/0167-8817(87)90057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore C W, McKoy J, Dardalhon M, Davermann D, Martinez M, Averbeck D. DNA damage-inducible and RAD52-independent repair of DNA double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2000;68:518–525. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.3.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odds F C. Candida and candidiosis. 2nd ed. London, England: Balliere Tindall; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paques F, Haber J E. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:349–404. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.349-404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perepnikhatka V, Fisher F J, Niimi M, Baker R A, Cannon R D, Wang Y, Sherman F, Rustchenko E. Specific alterations in fluconazole-resistant mutants of Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4041–4049. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.4041-4049.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pérez-Martín J, Uría J A, Johnson A D. Phenotypic switching in Candida albicans is controlled by a SIR2-like gene. EMBO J. 1998;18:2580–2592. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pla J, Monteoliva L, Navarro-García F, Sánchez M, Nombela C. Understanding Candida albicans at the molecular level. Yeast. 1996;12:1677–1702. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199612)12:16%3C1677::AID-YEA79%3E3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porta A, Ramon A M, Fonzi W. PRR1, a homolog of Aspergillus nidulans palF, controls pH-dependent gene expression and filamentation in Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7516–7523. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.24.7516-7523.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prakash S, Sung P, Prakash L. DNA repair genes and proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Genet. 1993;27:33–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.27.120193.000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pujol C, Reynes J, Renaud F, Raymond M, Tibayrenc M, Ayala F J, Janbon F, Mallié M, Bastide J. The yeast Candida albicans has a clonal mode of reproduction in a population of infected human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9456–9459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramon A M, Porta A, Fonzi W. Effect of environmental pH on morphological development of Candida albicans is mediated by the PacC-related transcription factor encoded by PRR2. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7524–7530. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.24.7524-7530.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramsden D A, Paull T T, Gellert M. Cell-free V(D)J recombination. Nature. 1997;388:488–491. doi: 10.1038/41351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schär P, Herrmann G, Daly G, Lindahl T. A newly identified DNA ligase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae involved in RAD52-independent repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1912–1924. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.15.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwartz J L. Monofunctional alkylating agent-induced S-phase-dependent DNA damage. Mutat Res. 1989;216:11–18. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(89)90011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sherman S, Fink G K, Hicks J B. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slutsky B, Buffo J, Soll D R. High-frequency switching of colony morphology in Candida albicans. Science. 1985;230:666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.3901258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soll D R. The emerging molecular biology of switching in Candida albicans. ASM News. 1996;62:415–420. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sonnerborn A, Bockmuhl D P, Gerards M, Kurpanek K, Sanglard D, Ernst J. Protein kinase A encoded by TPK2 regulates dimorphism of Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:386–396. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stoldt V R, Sonneborn A, Leuker C E, Ernst J. Efg1p, an essential regulator of morphogenesis of the human pathogen Candida albicans, is a member of a conserved class of bHLH proteins regulating morphogenetic processes in fungi. EMBO J. 1997;16:1982–1991. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suzuki T, Nishibayashi S, Kuroiwa T, Kanbe T, Tanaka K. Variance of ploidy in Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1982;152:893–896. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.2.893-896.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Teo S H, Jackson S P. Identification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA ligase IV: involvement in DNA double-strand break. EMBO J. 1997;16:4788–4795. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsang P W K, Cao B, Siu P Y L, Wang J. Loss of heterozygosity, by mitotic gene conversion and crossing over, causes strain-specific adenine mutants in constitutive diploid Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1999;145:1623–1629. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-7-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsukamoto Y, Kato J, Ikeda H. Silencing factors participate in DNA repair and recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 1997;388:900–903. doi: 10.1038/42288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ward M P, Gimeno C J, Fink G R, Garrett S. SOK2 may regulate cyclic AMP-dependent kinase-stimulated growth and pseudohyphal development by repressing transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1966;15:6854–6863. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whelan W L, Partridge R M, Magee P T. Heterozygosity and segregation in Candida albicans. Mol Gen Genet. 1980;180:107–113. doi: 10.1007/BF00267358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilson T E, Grawunder U, Lieber M R. Yeast DNA ligase IV mediates non-homologous DNA end joining. Nature. 1997;388:495–498. doi: 10.1038/41365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yamada-Okabe T, Mio T, Non T, Kashima Y, Matsui M, Arisawa M, Yamada-Okabe Y. Roles of three histidine kinase genes in hyphal development and virulence of the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7243–7247. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.23.7243-7247.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]