Abstract

Despite historical mischaracterization as a cosmetic condition, patients with the autoimmune disorder vitiligo experience substantial quality‐of‐life (QoL) burden. This systematic literature review of peer‐reviewed observational and interventional studies describes comprehensive evidence for humanistic burden in patients with vitiligo. PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus and the Cochrane databases were searched through February 10, 2021, to qualitatively assess QoL in vitiligo. Two independent reviewers assessed articles for inclusion and extracted data for qualitative synthesis. A total of 130 included studies were published between 1996 and 2021. Geographical regions with the most studies were Europe (32.3%) and the Middle East (26.9%). Dermatology‐specific instruments, including the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI; 80 studies) and its variants for children (CDLQI; 10 studies) and families (FDLQI; 4 studies), as well as Skindex instruments (Skindex‐29, 15 studies; Skindex‐16, 4 studies), were most commonly used to measure humanistic burden. Vitiligo‐specific instruments, including the Vitiligo‐specific QoL (VitiQoL; 11 studies) instrument and 22‐item Vitiligo Impact Scale (VIS‐22; 4 studies), were administered in fewer studies. Among studies that reported total scores for the overall population, a majority revealed moderate or worse effects of vitiligo on patient QoL (DLQI, 35/54 studies; Skindex, 8/8 studies; VitiQoL, 6/6 studies; VIS‐22, 3/3 studies). Vitiligo also had a significant impact on the QoL of families and caregivers; 4/4 studies reporting FDLQI scores indicated moderate or worse effects on QoL. In general, treatment significantly (P < 0.05) improved QoL, but there were no trends for types or duration of treatment. Among studies that reported factors significantly (P ≤ 0.05) associated with reduced QoL, female sex and visible lesions and/or lesions in sensitive areas were most common. In summary, vitiligo has clinically meaningful effects on the QoL of patients, highlighting that greater attention should be dedicated to QoL decrement awareness and improvement in patients with vitiligo.

Introduction

Vitiligo is an autoimmune depigmentation disorder 1 for which there is no cure or approved medical treatment for repigmentation of lesions. 2 Vitiligo lesions are characterized by a progressive loss of pigmentation caused by the destruction of functioning melanocytes in the epidermis. 3 The process of repigmentation is typically slow, and acral body areas (i.e. hands and feet) tend to be more refractory to repigmentation. 4 Patients experience a high quality‐of‐life (QoL) burden, 5 including significant psychological comorbidity. 6 , 7 Vitiligo onset typically occurs before 30 years of age, 8 and patients with a family history of vitiligo exhibit earlier disease onset. 9 The risk of vitiligo has been attributed to heritable genetic factors (approximately 80%) and environmental factors (approximately 20%). 1 Physical, environmental and psychosocial stressors not only contribute to vitiligo onset but are also involved in disease progression. 10

Quality of life is a multidimensional concept based on subjective perceptions of health, comfort and happiness in psychosocial and physical domains, among others. 11 Although patients with vitiligo may have comparatively lower levels of symptomatic impairment versus atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, the psychosocial impact of vitiligo is vast and distressing. 12 Studies investigating willingness to pay (WTP) in dermatological diseases have shown that WTP among patients with vitiligo is higher than in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. 13 , 14 , 15 Evidence of substantial reduction in overall QoL, together with high WTP among patients, highlights the significant patient burden of this disease.

The objective of this systematic literature review was to describe the evidence for humanistic burden (a holistic concept including impact on health‐related QoL, activities of daily living, caregiver health and QoL, as well as treatment benefit or satisfaction 16 ) in patients with vitiligo, including the instruments used to assess burden and factors affecting burden.

Methods

Literature search

PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus and the Cochrane database were searched for articles from the earliest entry in respective databases through February 10, 2021. The search string (Appendix S1), which was limited to articles published in English, included the keywords vitiligo, leucoderma, leukoderma, quality of life and patient‐reported outcomes. No limitations were placed on interventions. Duplicate results from the separate databases were removed before assessment of article eligibility. Subsequent to the searches, additional articles were identified from other sources, including through appraisal of existing systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Peer‐reviewed primary publications, including interventional and observational studies, were selected for inclusion. Two independent reviewers (WvdS and KW) performed title and abstract review as well as a full‐text review and data extraction. Studies excluded during these processes were reviews, editorials and commentaries, study protocols, articles with content irrelevant to general QoL in vitiligo, data sets that had <5 participants (e.g. patients with vitiligo or their caregivers), and retracted articles. The reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias in a qualitative manner and resolved disagreements by discussion.

This systematic literature review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 17 No institutional review board approval was required for the study because all data were collected from published articles. The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021260138).

Data extraction and analysis

Extracted data included study design, geographical region of the study, sample sizes, detailed patient demographics, clinical characteristics of vitiligo, QoL measures and outcomes, factors associated with QoL burden, the effect of treatment on QoL and caregiver burden. Where available, data reporting the burden of vitiligo in comparison with healthy controls and other skin diseases were also collected. All outcomes were analysed in a descriptive manner.

Results

Literature search

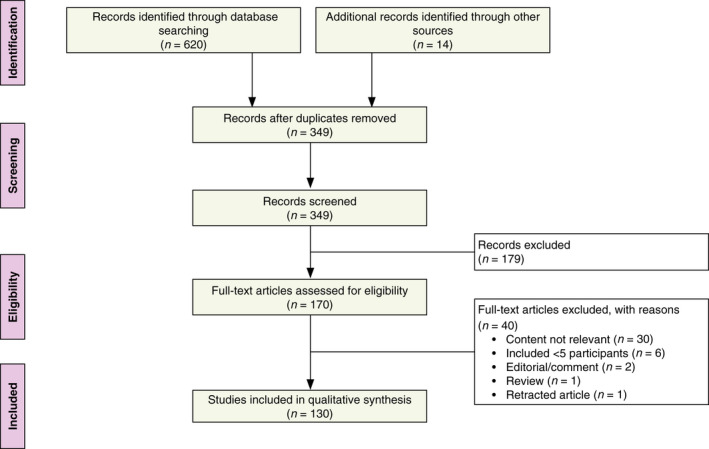

Initial database searches yielded 620 results, of which 285 were duplicate records that were excluded from screening; 14 records were identified through other sources. Screening resulted in the exclusion of 179 articles during title and abstract review; an additional 40 articles were excluded upon full‐text review due to irrelevant content (n = 30), inclusion of <5 patients with vitiligo or their caregivers (n = 6), editorials/commentaries (n = 2), reviews (n = 1) and retracted articles (n = 1). A total of 130 articles were retained for data extraction and inclusion in qualitative synthesis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses.

Study characteristics

Included studies were published between 1996 and 2021, with 78% published since 2010 (Fig. S1). Studies were characterized as observational (n = 97, 74.6%) or interventional (n = 33, 25.4%; including studies reporting pharmaceutical treatment, phototherapy, photochemotherapy, surgical treatment, climatotherapy, homeopathic/natural treatment, camouflage and counselling); paediatric and adult populations were represented. Study characteristics and sample sizes are presented in Table 1. Studies representing populations from most geographical regions were included (Fig. S2); regions with the most studies were Europe (32.3%) and the Middle East (26.9%). All studies were qualitatively assessed to minimize the risk of bias and were deemed to be of acceptable quality for inclusion in the systematic literature review.

Table 1.

Summary of study characteristics

| Characteristic |

Number of studies, n (%) N = 130 |

|---|---|

| Study type | |

| Observational | 97 (74.6) |

| Interventional* | 33 (25.4) |

| Geographical region† | |

| Africa | 2 (1.5) |

| Europe | 42 (32.3) |

| Eastern Asia‡ | 18 (13.8) |

| Southern Asia | 21 (16.2) |

| Middle East | 35 (26.9) |

| North America | 12 (9.2) |

| South America | 5 (3.8) |

| Age group of patients with vitiligo§ | |

| Adult only (≥18 years) | 58 (44.6) |

| Paediatric only (<18 years) | 14 (10.8) |

| Mixed¶ | 50 (38.5) |

| Number of patients with vitiligo | |

| ≤50 | 42 (32.3) |

| 51–150 | 59 (45.4) |

| 151–250 | 14 (10.8) |

| >250 | 15 (11.5) |

QoL, quality of life.

Interventions included pharmaceutical treatment, phototherapy, photochemotherapy, surgical treatment, climatotherapy, homeopathic/natural treatment, camouflage and counselling.

Multinational studies conducted in 2 geographical regions are listed under both regions (Europe/Middle East, 2 studies; Europe/North America, 2 studies; Southern Asia/North America, 1 study).

Includes Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia.

Patient age groups were not reported for 8 (6.2%) studies.

Studies with mixed populations often included patients ≥16 years of age, who are considered to be adults for the application of some QoL instruments.

Per‐instrument QoL burden in patients with vitiligo

Dermatology‐specific instruments were most commonly used to measure humanistic burden (including QoL and patient satisfaction or benefit), followed by vitiligo‐specific instruments and generic tools. Study characteristics and findings from observational and interventional study assessments that reported results in the overall population are summarized in Table 2 (dermatology‐ and vitiligo‐specific instruments) and Table S1 (generic tools). Several studies reported differences between the QoL in patients with vitiligo and other groups. Compared with healthy controls, QoL in patients with vitiligo was significantly reduced (P ≤ 0.05) in 13 studies 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 and similar in six studies. 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 Compared with other dermatological diseases, QoL in patients with vitiligo was significantly worse (P ≤ 0.05) compared with melasma 36 and significantly better (P ≤ 0.05) compared with psoriasis 21 , 37 , 38 , 39 ; reports of QoL impairment in vitiligo compared with atopic dermatitis were inconsistent. 19 , 26 Below, data for instruments measuring QoL are presented by decreasing order of use among included studies.

Table 2.

Dermatology‐ and vitiligo‐specific quality‐of‐life assessment tools and outcomes among studies that reported total scores in the overall population

| Study | Country | Sample size at baseline | Total score, mean (SD) | Total score, median (Range) | Estimated effect on QoL* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLQI * | |||||

| Aghaei 2004 44 | Iran | 70 | 7.05 (5.13) | – | Moderate |

| Al Robaee 2007 46 | Saudi Arabia | 109 | 14.7 (5.17) | – | Very large |

| Al‐Shobaili 2015 47 | Saudi Arabia | 134 | 10.6 (4.3) | – | Moderate |

| Amatya 2019 48 | Nepal | 100 | 4.13 (3.74) | 3 (0–17) | Small |

| Anaba 2020 49 | Nigeria | 29 | – | 5 (IQR, 2–10) | Small |

| Bassiouny 2021 50 | Egypt | 100 | 12.5 (4.2) | – | Very large |

| Bin Saif 2013 51 | Saudi Arabia | 141 | 9 (6.5) | – (0–25) | Moderate |

| Boza 2015 53 | Brazil | 74 | – | 3 (IQR, 1–7) | Small |

| Catucci Boza 2016 55 | Brazil | 93 | – | 3.00 (IQR, 1.00–6.50) | Small |

| Chahar 2018 57 | India | 54 | 9.64 (4.32) | – | Moderate |

| Chan 2012 59 | Singapore | 145 | 4.4 (4.5) | 3.0 (0–23) | Small |

| Chan 2013 58 | Singapore | 222 | 4.0 (4.4) | – | Small |

| Chen 2019 60 | China | 884 | 5.83 (5.75) | – (0–30) | Small |

| Dabas 2019 36 | India | 95 | 10.3 (6.65) | – | Moderate |

| Doʇruk Kaçar 2014 61 | Turkey | 34 | 6.02 (2.55) | – (2–14) | Moderate |

| Dolatshahi 2008 62 | Iran | 100 | 8.16 (5.42) | – (0–28) | Moderate |

| Ezzedine 2015 64 | France | 261 | 8.7 (6.2) | 7.0 (0–28.0) | Moderate |

| Fawzy 2013 65 | Egypt | 104 | 9.52 (5.88) | – (1–24) | Moderate |

| Ghaderi 2014 66 | Iran | 70 | 8.40 (5.80) | – | Moderate |

| Ghajarzadeh 2012 37 | Iran | 100 | 8.4 (6.9) | – | Moderate |

| Gupta 2014 67 | India | 161 | 8.25 (6.93) | – | Moderate |

| Gupta 2019 68 | India | 382 | 7.8 (6.6) | – (0–28) | Moderate |

| Hartmann 2005 71 | Germany | 9 | 13 (6.1) | – (8–25) | Very large |

| Hartmann 2008 70 | Germany | 30 | 12.4 (6.5) | – (2–27) | Very large |

| Ingordo 2012 75 | Italy | 47 | 1.82 (2.95) | – | No effect |

| Ingordo 2014 74 | Italy | 161 | 4.3 (4.9) | – (0–22) | Small |

| Karelson 2013 21 | Estonia | 54 | 4.7 (–) | – (0–22) | Small |

| Kent 1996 77 | United Kingdom | 614 | 4.82 (4.84) | – (0–26) | Small |

| Kiprono 2013 78 | Tanzania | 88 | 7.2 (4.8) | – | Moderate |

| Kostopoulou 2009 79 | France | 48 | 7.17 (4.8) | – (0–18) | Moderate |

| Kota 2019 80 | India | 150 | 7.02 (5.58) | – | Moderate |

| Kruger 2015 22 | Germany | 96 | 4.9 (–) | – | Small |

| Mashayekhi 2010 83 | Iran | 83 | 7.54 (4.97) | – (0–20) | Moderate |

| Mishra 2014 84 | India | 100 | 6.86 (–) | – | Moderate |

| Morales‐Sanchez 2017 85 | Mexico | 150 | 5.2 (5.4) | – | Small |

| Noh 2013 26 | South Korea | 60 | 7.61 (–) | – | Moderate |

| Ongenae 2005a 38 | Belgium | 102 | 4.95 (–) | – (0–8) | Small |

| Ongenae 2005b 89 | Belgium | 78 | 6.9 (5.6) | – (0–20) | Moderate |

| Parsad 2003 91 | India | 150 | 10.7 (4.56) | – (2–21) | Moderate |

| Radtke 2009 15 | Germany | 1023 | 7.0 (5.9) | – (0–27) | Moderate |

| Salman 2016 94 | Turkey | 37 | 5.6 (5.1) | – | Small |

| Sangma 2015 28 | India | 100 | 9.08 (4.46) | – | Moderate |

| Senol 2013 97 | Turkey | 183 | 15.0 (4.6) | 14.0 (IQR, 11.0–17.0) | Very large |

| Silpa‐Archa 2020 99 | Thailand | 104 | 7.46 (6.06) | 6 (0–26) | Moderate |

| Silverberg 2013 100 | United States | 1541 | 5.9 (5.5) | – | Small |

| Tejada 2011 102 | Brazil | 16 | – | 13 (IQR, 9–15.5) | Very large |

| Temel 2019 103 | Turkey | 50 | 4.70 (5.33) | – | Small |

| Udaya Kiran 2020 104 | India | 14 | 12.4 (4.48) | – | Very large |

| van Geel 2006 105 | Belgium | 40 | 6.95 (6.68) | 4.5 (0–21) | Moderate |

| van Geel 2021 106 | Belgium | 315 | – | 2 (0–21) | Small |

| Wang 2011 35 | China | 101 | 8.41 (7.31) | – | Moderate |

| Wong 2012 107 | Malaysia | 102 | 6.4 (–) | – (0–20) | Moderate |

| Xu 2017 39 | South Korea | 37 | 4.49 (3.97) | – | Small |

| Zandi 2011 110 | Iran | 124 | 9.09 (6.2) | – | Moderate |

| CDLQI * | |||||

| Catucci Boza 2016 55 | Brazil | 24 | – | 3 (IQR, 1.3–7.3) | Small |

| Dertlioglu 2013 19 | Turkey | 50 | 11.7 (6.54) | – | Very large |

| Kruger 2014 24 | Germany, United States | 74 | 2.8 (–) | – | Small |

| Kruger 2018 23 | Germany, United States | 85 | 2.81 (3.65) | – (0–17) | Small |

| Manzoni 2012 111 | Brazil | 43 | – | 2 (IQR, 1–6) | Small |

| Njoo 2000 112 | Netherlands | 51 | 5.6 (3.8) | – | Small |

| Ramien 2014 113 | Canada | 9 | 5.0 (–) | – | Small |

| Savas Erdogan 2020 114 | Turkey | 29 | 2.76 (2.39) | – (0–8) | Small |

| Silverberg 2014 115 | United States | 336 | – | 3.0 (IQR, 5) | Small |

| FDLQI * | |||||

| Andrade 2020 149 | United States | 118 | 13.1 (3.5) | – | Very large |

| Bin Saif 2013 51 | Saudi Arabia | 141 | 10.3 (6.4) | – (range, 0–26) | Moderate |

| Handjani 2013 151 | Iran | 15 | 14.4 (5.08) | – | Very large |

| Saeedeh 2019 152 | Iran | 150 | 6.1 (6.1) | 5 (0–24) | Moderate |

| Skindex‐29 † | |||||

| Choi 2010 121 | South Korea | 57 | 21.8 (–) | – | Moderate |

| Kim 2009 122 | South Korea | 133 | 30.7 (19.2) | – | Moderate |

| Komen 2015 123 | Netherlands | 60 | 20.8 (–) | – | Moderate |

| Linthorst Homan 2009 125 | Netherlands | 245 | 22.8 (17.1) | – | Moderate |

| Sanclemente 2017 129 | Colombia | 99 | – (16.2) | 21.5 (–) | Moderate |

| Xu 2017 39 | South Korea | 37 | 33.1 (12.4) | – | Moderate |

| Skindex‐16 † | |||||

| Essa 2018 131 | Egypt | 21 | 39.4 (19.2) | – | Severe |

| Gupta 2014 67 | India | 161 | 32.0 (23.1) | – | Moderate |

| VitiQoL ‡ | |||||

| Anaba 2020 49 | Nigeria | 29 | – | 38 (IQR, 17–54) | Moderate |

| Boza 2015 53 | Brazil | 74 | 40.0 (27.3) | – | Severe |

| Catucci Boza 2016 55 | Brazil | 93 | – | 37.0 (IQR, 17.0–64.5) | Moderate |

| Hedayat 2016 133 | Iran | 173 | 30.5 (14.5) | 31 (0–60) | Moderate |

| Morales‐Sanchez 2017 85 | Mexico | 150 | 32.1 (22.7) | – | Moderate |

| Pun 2021 135 | Nepal | 22 | 37.2 (24.2) | – | Moderate |

| VIS | |||||

| Pun 2021 135 | Nepal | 22 | 23.9 (15.9) | – | – |

| VIS‐22 § | |||||

| Gupta 2014 67 | India | 161 | 26.5 (14.5) | – | Large |

| Gupta 2019 68 | India | 391 | 24.8 (14.0) | – (0–61) | Moderate |

| Kota 2019 80 | India | 150 | 16.4 (9.57) | – | Moderate |

| VLQI | |||||

| Senol 2013 97 | Turkey | 183 | 44.0 (12.1) | 43.0 (IQR, 35.0–52.0) | – |

CDLQI, Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; FDLQI, Family Dermatology Life Quality Index; IQR, interquartile range; QoL, quality of life; VIS, Vitiligo Impact Scale; VitiQoL, Vitiligo‐specific Quality of Life; VLQI, Vitiligo Life Quality Index.

Interpretation of total scores based on mean. If mean was not available, median was used for interpretation.

DLQI/CDLQI/FDLQI total score interpretation: 0–1, no effect at all on patient’s life; 2–5, small effect on patient’s life; 6–10, moderate effect on patient’s life; 11–20, very large effect on patient’s life; 21–30, extremely large effect on patient’s life.

Skindex total score interpretation: ≤5, very little effect; 6–17, mild effect; 18–36, moderate effect; ≥37, severe effect.

VitiQoL total score interpretation: 0–5, no effect; 6–20, mild effect; 21–38, moderate effect; ≥39, severe effect.

VIS‐22 total score interpretation: 0–5, no effect; 6–15, mild effect; 16–25, moderate effect; 26–40, large effect; and 41–66, very large effect.

Dermatology Life Quality Index

The majority of studies (91/130) used the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and/or its variants for children (CDLQI) and family (FDLQI), all of which have possible scores that range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating worse QoL. 40 , 41 , 42 DLQI‐based instruments are scored as follows: total score of 0–1 translates to no effect at all on a patient’s life; 2–5, small effect; 6–10, moderate effect; 11–20, very large effect; 21–30, extremely large effect.

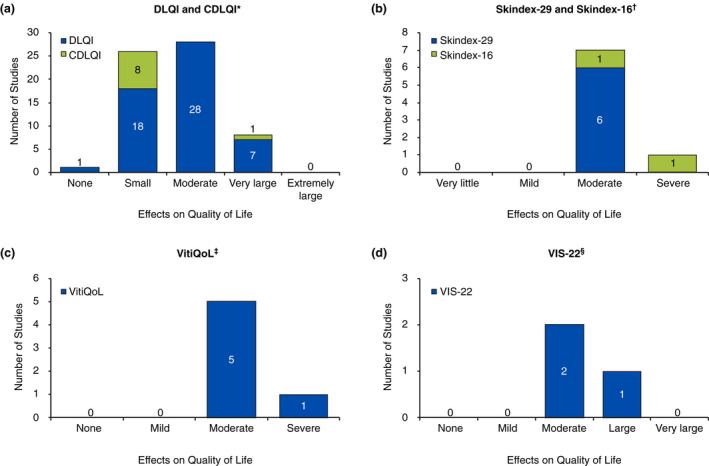

The DLQI was administered in 80 studies 15 , 21 , 22 , 25 , 26 , 28 , 30 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 ; the instrument can be administered to patients ≥16 years old. Among studies that reported a total DLQI mean score for the overall population, mean scores ranged from 1.82 to 15.0 15 , 21 , 22 , 26 , 28 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 44 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 50 , 51 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 70 , 71 , 74 , 75 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 89 , 91 , 94 , 97 , 99 , 100 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 107 , 110 ; as such, vitiligo effects on the lives of patients ranged from no effects to very large effects (Fig. 2a). In general, QoL was least impaired among patients from Italy (DLQI total scores, 1.82 and 4.3) 74 , 75 and Singapore (4.0 and 4.4) 58 , 59 and most impaired among patients from Saudi Arabia (9, 10.6 and 14.7) 46 , 47 , 51 and Egypt (9.52 and 12.5). 50 , 65

Figure 2.

Categorization of mean total scores for (a) DLQI and CDLQI,* (b) Skindex‐29 and Skindex‐16,† (c) VitiQoL,‡ and (d) VIS‐22.§ CDLQI, Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; VIS, Vitiligo Impact Scale; VitiQoL, Vitiligo‐specific Quality of Life. * DLQI/CDLQI total score interpretation: 0–1, no effect at all on patient’s life; 2–5, small effect on patient’s life; 6–10, moderate effect on patient’s life; 11–20, very large effect on patient’s life; 21–30, extremely large effect on patient’s life. † Skindex total score interpretation: ≤5, very little effect; 6–17, mild effect; 18–36, moderate effect; ≥37, severe effect. ‡ VitiQoL total score interpretation: 0–5, no effect; 6–20, mild effect; 21–38, moderate effect; ≥39, severe effect. § VIS‐22 total score interpretation: 0–5, no effect; 6–15, mild effect; 16–25, moderate effect; 26–40, large effect; and 41–66, very large effect.

The CDLQI, utilized in 10 studies, 19 , 23 , 24 , 43 , 55 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 is administered to patients 5 to 16 years old. Among studies that reported CDLQI total mean scores in the overall population, scores ranged from 2.76 to 11.7 19 , 23 , 24 , 112 , 113 , 114 ; vitiligo scores indicated that the disease had small to very large effects on patients’ lives (Fig. 2a). One additional study used a modified DLQI questionnaire 116 that included items on marriageability and spirituality to fit the cultural context of the Iranian study population, with higher scores indicating worse QoL. Female patients had significantly worse QoL than their male counterparts (P = 0.002). 116

Skindex

Skindex instruments were used in 19 studies; scores range from 0 to 100 on both the 29‐item (Skindex‐29) and 16‐item (Skindex‐16) instruments, with higher scores indicating reduced QoL. 117 The Skindex total score can be interpreted as having very little effect (score ≤ 5), mild effect (scores 6–17), moderate effect (scores 18–36) and severe effect (scores ≥ 37) on QoL. 118 The Skindex‐29 was administered in 15 studies. 33 , 39 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 , 123 , 124 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 , 129 , 130 Among studies that reported mean global scores in the overall population, scores ranged from 20.8 to 33.1 39 , 121 , 122 , 123 , 125 ; these scores indicate that vitiligo had moderate effects on patients’ lives (Fig. 2b). The Skindex‐16 was administered in four studies. 67 , 81 , 82 , 131 Among studies that reported mean global scores in the overall population, scores were 32.0 and 39.4, 67 , 131 indicating that patients experienced moderate to severe effects (Fig. 2b).

Vitiligo‐specific QoL instrument

The Vitiligo‐specific Quality of Life (VitiQoL) instrument, with scores that range from 0 to 90, was employed in 11 studies 49 , 53 , 55 , 82 , 85 , 120 , 132 , 133 , 134 , 135 , 136 ; higher scores indicate poorer QoL. One study shared an interpretation of VitiQoL scores with 0–5 representing no effect, 6–20 mild effect, 21–38 moderate effect and ≥39 severe effect. 49 Among studies that reported mean total scores for the overall population, the range was 30.5 to 40.0, 53 , 85 , 133 , 135 suggesting that patients with vitiligo experienced moderate to severe QoL impairment (Fig. 2c).

Vitiligo Impact Scale

The Vitiligo Impact Scale (VIS) was used in six studies, two of which employed the original 27‐item questionnaire (scores ranging from 0–8 81 , 135 and four of which employed the abbreviated 22‐item questionnaire (VIS‐22; scores ranging from 0–66). 60 , 67 , 68 , 80 Although no ratings of severity have been recognized for VIS scores, higher scores indicate poorer psychosocial QoL. VIS‐22 scores can be interpreted as follows: 0–5, no effect; 6–15, mild effect; 16–25, moderate effect; 26–40, large effect and 41–66, very large effect. 68 One study presented a VIS mean total score of 23.9 in the overall population. 135 VIS‐22 mean total scores ranged from 16.4 to 26.5, 67 , 68 , 80 indicating moderate to large effects of vitiligo on QoL (Fig. 2d).

Vitiligo Life Quality Index

Only one study reported results of the Vitiligo Life Quality Index (VLQI), 97 which is a vitiligo‐specific version of the DLQI. The mean score on the VLQI was 44.0, 97 which was shown to correlate significantly with the DLQI and with the perceived severity of vitiligo (both P < 0.001).

Generic instruments

The Short‐Form 36 (SF‐36) health survey questionnaire was used in nine studies, 29 , 33 , 35 , 37 , 39 , 66 , 124 , 125 , 137 one of which used version 2 of the questionnaire 29 ; on this instrument, higher scores indicate better QoL. Among studies that reported mean mental and physical component scores of the SF‐36 in the overall population, physical component scores ranged from 53.6 to 54.9, 29 , 33 , 125 and mental component scores ranged from 46.3 to 48.1 29 , 33 , 125 ; overall, it appears that patients with vitiligo experience more mental than physical impairment. This was also demonstrated in one study that used the abbreviated Short‐Form 12 (SF‐12) questionnaire. 64

The Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL) inventory was completed in three studies, 27 , 32 , 34 two of which also administered the proxy questionnaire to parents of patients with vitiligo 27 , 32 ; scores range from 0 to 100, with higher total scores indicating better QoL. 138 Questionnaires administered to paediatric patients and their parents yielded relatively similar total scores regarding the perception of vitiligo impact on children/adolescents; mean scores among children/adolescents ranged from 76.5 to 90.2, 27 , 32 , 34 and parent’s mean scores ranged from 72.3 to 73.5. 27 , 32

The 60‐item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) was used in two studies, 76 , 103 and the abbreviated 28‐item questionnaire (GHQ‐28) was used in two studies 20 , 52 ; higher scores indicate worse QoL. GHQ total scores in patients who reported that vitiligo had an effect on their lives during the past 3 weeks were significantly higher (P < 0.001) versus those who reported no effects on their lives. 76 Other generic questionnaires used in studies included the EuroQol 5‐Dimension (EQ‐5D; 2 studies), 15 , 31 EQ‐5D five level (EQ‐5D‐5L; 1 study), 120 Child Health Utility 9‐Dimension (CHU‐9D; 1 study), 120 Perceived Health Status (PHS; 1 study), 103 Self‐Rated Health Measurement Scale (SRHMS; 1 study), 18 World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQOL‐BREF; 1 study), 43 ENRICH marital inventory (1 study) 35 and generic study‐specific QoL questionnaires (6 studies). 139 , 140 , 141 , 142 , 143 , 144 Measures of patient‐perceived severity of vitiligo included the Visual Analog Scale (VAS; 4 studies), 45 , 47 , 67 , 73 generic questionnaires (5 studies, 54 , 93 , 105 , 145 , 146 including one that used a VAS‐based questionnaire 145 ), the Patient Benefit Index (PBI [2 studies] 63 , 147 and PBI 2.0 [1 study] 148 ) and EuroQol VAS (EQ‐VAS; 1 study). 31

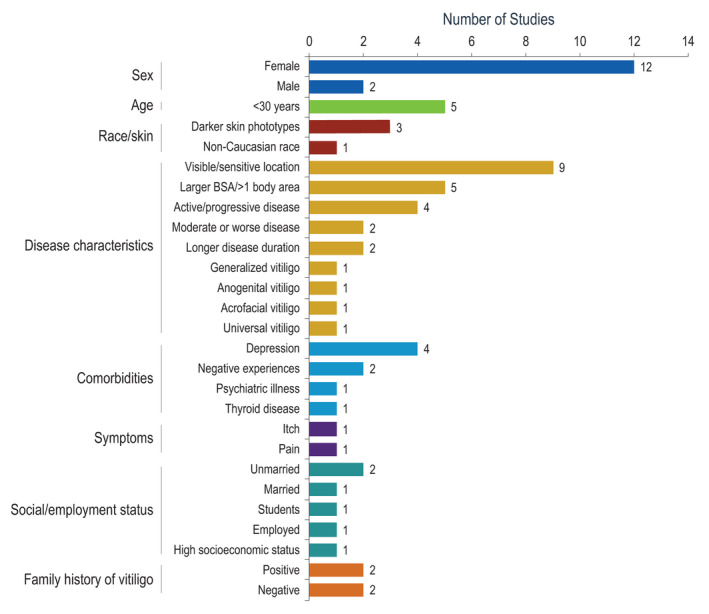

Factors that reduced QoL in patients with vitiligo

Several articles discussed factors that significantly (P ≤ 0.05) reduced QoL; Fig. 3 summarizes factors that affected total scores on the previously discussed instruments. Women generally had worse QoL, 37 , 38 , 50 , 52 , 55 , 60 , 65 , 81 , 83 , 133 , 139 , 145 although two studies showed significantly poorer QoL in men. 46 , 116 QoL was reduced in patients with visible lesions (i.e. face, neck, hands) and/or lesions in sensitive areas (i.e. genital, anogenital) 15 , 24 , 30 , 50 , 60 , 75 , 85 , 107 , 132 ; patients <30 years old (especially adolescents) 50 , 60 , 80 , 115 , 133 ; patients with involvement of a larger body surface area or lesions on several body areas, 15 , 75 , 89 , 110 , 149 including those with moderate or worse vitiligo 81 , 121 ; and in patients with active and/or progressive disease. 36 , 50 , 75 , 99 Darker skin phototypes 62 , 64 , 99 and non‐Caucasian race 77 (notably, some studies reported no significant differences among patients with fairer or darker skin phototypes 22 , 50 , 65 , 133 ); longer disease duration 15 , 133 ; as well as generalized, 58 anogenital, 60 acrofacial 65 and universal vitiligo 85 were associated with reduced QoL. General QoL was reduced in patients with reported psychosocial burden including psychiatric illness, 55 depression, 21 , 58 , 59 , 99 and negative experiences due to vitiligo 33 , 76 ; patients with thyroid disease 58 ; and patients who reported symptoms including itching and pain. 60 Employment status and socioeconomic status also affected QoL; worse QoL was seen in students versus employed patients 50 and employed versus unemployed patients, 107 as well as patients with high versus middle or low socioeconomic status. 50 Marital status showed inconsistent results, with two studies showing reduced QoL in unmarried patients 36 , 92 and one study showing reduced QoL in married individuals. 62 Family history of vitiligo also showed inconsistent results; positive family history reduced QoL in two studies, 62 , 65 whereas negative family history reduced QoL in two studies. 24 , 107

Figure 3.

Factors significantly associated with reduced QoL. BSA, body surface area; QoL, quality of life.

Effects of interventions on QoL in patients with vitiligo

Tables 3 and S2 summarize findings from interventional studies (in dermatology‐ and vitiligo‐specific and generic instruments respectively), including the effects of pharmaceutical treatment, phototherapy, photochemotherapy, surgical treatment, climatotherapy, homeopathic/natural treatment, camouflage and counselling on QoL. In general, most interventions significantly improved QoL at end of follow‐up compared with baseline 25 , 43 , 45 , 47 , 50 , 54 , 57 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 86 , 89 , 90 , 93 , 104 , 105 , 108 , 112 , 134 , 136 , 144 ; however, differences between treatment comparators within studies were rarely reported as significant. DLQI was used in the majority (23/33) of interventional studies 25 , 43 , 45 , 47 , 50 , 54 , 56 , 57 , 63 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 86 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 93 , 98 , 101 , 104 , 105 , 108 ; meaningful score changes (4‐point score reduction) 150 were achieved with ≥1 treatment arm in 10 studies. 25 , 45 , 47 , 50 , 54 , 57 , 73 , 93 , 104 , 108 Among studies that assessed patient satisfaction or patient benefit with previous or current treatment (8 interventional studies 45 , 47 , 54 , 63 , 73 , 93 , 105 , 145 and 5 observational studies 31 , 67 , 146 , 147 , 148 ), approximately half showed significant improvement in patient satisfaction with their vitiligo after treatment. 45 , 47 , 54 , 73 , 93 , 145

Table 3.

Dermatology‐ and vitiligo‐specific quality‐of‐life assessment tools and outcomes in interventional studies

| Study | Country | Sample size at baseline | Treatment group | Baseline | Follow‐up | P value vs baseline | P value vs comparator | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | Last follow‐up | Total score | ||||||

| DLQI | ||||||||

| Agarwal 2005 43 | India | 25 | Levamisole | Median (range), 4 (0–18) | 6 months | Median (range), 1 (0–7) | 0.003 | NS |

| 17 | Placebo | Median (range), 3.5 (0–15) | 6 months | Median (range), 1 (0–14) | 0.025 | Ref | ||

| Akdeniz 2014 45 | Turkey | 15 | NB‐UVB + topical calcipotriol + betamethasone |

Mean (SD), 7.67 (0.50) |

6 months |

Mean (SD), 2 (0.64) |

<0.01* | NA |

| 15 | NB‐UVB + topical calcipotriol |

Mean (SD), 8.40 (0.39) |

6 months |

Mean (SD), 2 (0.54) |

<0.01* | NA | ||

| 15 | NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 9.93 (0.63) |

6 months |

Mean (SD), 4 (0.71) |

<0.01* | NA | ||

| Al‐Shobaili 2015 47 | Saudi Arabia | 134 | Monochrome excimer light |

Mean (SD), 10.6 (4.3) |

16 weeks |

Mean (SD), 4.5 (3.9) |

<0.001* | NA |

| Bassiouny 2021 50 | Egypt | 40 | Camouflage |

Mean (SD), 13.4 (3.6) |

1 month |

Mean (SD), 7.5 (3.7) |

<0.001* | NA |

| 60 | None |

Mean (SD), 11.9 (4.5) |

1 month |

Mean (SD), 10.6 (4.2) |

<0.001 | NA | ||

| Budania 2012 54 | India | 21 | Non‐cultured epidermal cell suspension grafting |

Mean, 11.5 |

16 weeks |

Mean 2.24 |

<0.001* | 0.045† |

| 20 | Suction blister epidermal grafting |

Mean, 9.7 |

16 weeks |

Mean, 2.9 |

<0.001* | Ref | ||

| Cavalie 2015 56 | France | 16 | Placebo |

Mean (SD), 6.48 (2.80) |

6 months |

Mean (SD), 4.59 (3.53) |

NS | NA |

| 19 | Tacrolimus |

Mean (SD), 4.79 (3.58) |

6 months |

Mean (SD), 3.54 (2.91) |

NS | NA | ||

| Chahar 2018 57 | India | 54 | NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 9.64 (4.32) |

6 months |

Mean (SD), 4.86 (2.15) |

<0.001* | NA |

| Eleftheriadou 2014 63 | United Kingdom | 19 | Hand‐held NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 2.8 (3.2) |

16 weeks |

Mean (SD), 3.2 (2.3) |

NS | NS |

| 10 | Placebo |

Mean (SD), 3.8 (3.2) |

16 weeks |

Mean (SD), 3.7 (3.8) |

NS | Ref | ||

| Hartmann 2005 71 | Germany | 9 | UVB (narrow‐band or broadband) + calcipotriol ointment (right side of body) or placebo ointment (left side of body) |

Mean (SD), 13 (6.1) |

12 months |

Mean (SD), 9.4 (4.9) |

<0.05 | NA |

| Hartmann 2008 70 | Germany | 30 | Tacrolimus 0.1% ointment |

Mean (SD), 12.4 (6.5) |

12 months |

Mean (SD), 9.3 (5.6) |

0.001 | NA |

| Hosseinkhani 2015 72 | Iran | 15 | Sabgh formulation for camouflage |

Mean (SD), 12.9 (5.68) |

8 weeks |

Mean (SD), 9.60 (4.32) |

<0.001 | NA |

| 15 | Exuviance formulation for camouflage |

Mean (SD), 12.8 (7.22) |

8 weeks |

Mean (SD), 10.3 (6.18) |

0.006 | NA | ||

| Ibrahim 2020 73 | Egypt | 19 | MBEH 20% |

Mean (SD), 11.9 (6.11) |

12 months |

Mean (SD), 2.39 (4.39) |

<0.001* | NA |

| 20 | MBEH 40% |

Mean (SD), 11.2 (6.27) |

12 months |

Mean (SD), 1.70 (3.73) |

<0.001* | NA | ||

| Kruger 2011 25 | Germany, Jordan | 71 | Climatotherapy with PC‐KUS (year 1) |

Mean, 7.8 |

Day 20 (year 1) |

Mean, 1.9 |

<0.001* | Ref |

| 33 | Climatotherapy with PC‐KUS (year 2) |

Mean, 6.2 |

Day 20 (year 2) |

Mean, 2.1 |

<0.001* | NS | ||

| Mou 2016 86 | China | 37 | Oral compound glycyrrhizin |

Mean (SD), 4.8 (4.5) |

6 months |

Mean (SD), 2.9 (2.6) |

<0.001 | NA |

| 36 | NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 6.3 (4.8) |

6 months |

Mean (SD), 3.1 (2.4) |

<0.001 | NA | ||

| 42 | Oral compound glycyrrhizin + NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 5.6 (3.2) |

6 months |

Mean (SD), 1.8 (1.5) |

<0.001 | NA | ||

| Ongenae 2005b 89 | Belgium | 62 | Camouflage |

Mean (SD), 7.3 (5.6) |

≥1 month |

Mean (SD), 5.9 (5.2) |

0.006 | NA |

| Papadopoulos 1999 90 | United Kingdom | 8 | Cognitive behavioural therapy‐based counselling | NA | 5 months | NA | <0.001 | NA |

| Parsad 2003 91 | India | 91 | PUVA/OMP betamethasone (treatment success) | NA | 12 months |

Mean, 7.06 |

NA | <0.0001 |

| 50 | PUVA/OMP betamethasone (treatment failure) | NA | 12 months |

Mean, 13.12 |

NA | Ref | ||

| Sahni 2011 93 | India | 13 | Non‐cultured melanocyte transplant + saline |

Mean, 8.85 |

16 weeks |

Mean, 3.62 |

0.002* | Ref |

| 12 | Non‐cultured melanocyte transplant + serum |

Mean, 11.42 |

16 weeks |

Mean, 2.17 |

0.002* | 0.005† | ||

| Shah 2014 98 | United Kingdom | 24 | Enhanced cognitive behavioural self‐help leaflet |

Mean (SD), 5.43 (6.17) |

8 weeks |

Percentage change from baseline, ~53% |

NA | NS |

| 25 | Cognitive behavioural self‐help leaflet |

Mean (SD), 6.75 (5.31) |

8 weeks |

Percentage change from baseline, ~58% |

NA | NS | ||

| 26 | None |

Mean (SD), 6.73 (5.98) |

8 weeks |

Percentage change from baseline, ~46% |

NA | Ref | ||

| Tanioka 2010 101 | Japan | 21 | Cosmetic camouflage lessons |

Mean, 5.90 |

1 month |

Mean, 4.48 |

NA | 0.005† |

| 11 | None |

Mean, 3.18 |

1 month |

Mean, 4.36 |

NA | Ref | ||

| Udaya Kiran 2020 104 | India | 14 | Cosmetic camouflage + camouflage lessons |

Mean (SD), 12.42 (4.48) |

30 days |

Mean (SD), 3.78 (1.52) |

<0.0001* , † | NA |

| van Geel 2006 105 | Belgium | 40 | Non‐cultured epidermal cellular graft surgery |

Mean (SD), 6.95 (6.68) |

6 or 12 months |

Mean (SD), 3.85 (4.13) |

0.016 | NA |

| Yones 2007 108 | United Kingdom | 25 | NB‐UVB |

Median, ~6 |

End of treatment (median, 97 sessions) |

Median, ~3 |

<0.001 | 0.8 |

| 25 | PUVA |

Median, ~10 |

End of treatment (median, 47 sessions) |

Median, ~4 |

<0.001* | Ref | ||

| CDLQI | ||||||||

| Agarwal 2005 43 | India | 7 | Levamisole | Median (range), 1.5 (0–6) | 6 months |

Median (range), 1 (0–6) |

0.17 | NS |

| 11 | Placebo | Median (range), 3 (0–8) | 6 months |

Median (range), 1 (0–2) |

0.57 | Ref | ||

| Njoo 2000 112 | Netherlands | 51 | NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 5.6 (3.8) |

12 months |

Mean (SD), 2.1 (2.0) |

<0.001 | NA |

| Ramien 2014 113 | Canada | 9 | Cosmetic camouflage |

Mean, 5.0 |

6 months |

Mean, 3.2 |

NS† | NA |

| Skindex‐29 | ||||||||

| Batchelor 2020 120 | United Kingdom | 133 | Topical corticosteroids |

Mean (SD), 22.8 (15.7) |

21 months |

Mean (SD), 22.5 (16.5) |

NA | Ref |

| 130 | NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 21.4 (18.6) |

21 months |

Mean (SD), 19.1 (16.6) |

NA | NS | ||

| 135 | Topical corticosteroids + NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 23.8 (18.7) |

21 months |

Mean (SD), 25.9 (17.5) |

NA | NS | ||

| Middelkamp‐Hup 2007 126 | Netherlands | 24 | Polypodium leucotomos + NB‐UVB | – | 26 weeks | Change from baseline, 4 | NA | NS |

| 24 | Placebo + NB‐UVB | – | 26 weeks | Change from baseline, 2 | NA | Ref | ||

| Sassi 2008 130 | Italy | 42 | Excimer laser |

Mean (SEM), 19.4 (2.53) |

12 weeks |

Mean (SEM), 14.2 (2.25) |

NA | 0.727 |

| 42 | Excimer laser + topical hydrocortisone |

Mean (SEM), 23.7 (2.18) |

12 weeks |

Mean (SEM), 19.0 (2.30) |

NA | Ref | ||

| VitiQoL | ||||||||

| Batchelor 2020 120 | United Kingdom | 133 | Topical corticosteroids |

Mean (SD), 34.7 (21.8) |

21 months |

Mean (SD), 36.1 (21.1) |

NA | Ref |

| 130 | NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 33.3 (23.8) |

21 months |

Mean (SD), 31.1 (22.8) |

NA | NS | ||

| 135 | Topical corticosteroids + NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 35.6 (23.3) |

21 months |

Mean (SD), 38.4 (23.6) |

NA | NS | ||

| Liu 2020 134 | China | 52 | Home‐based NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 42 (1.10) |

20 weeks |

Mean (SD), 19.0 (1.14) |

<0.001 | NS |

| 48 | Hospital‐based NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 42.2 (3.69) |

20 weeks |

Mean (SD), 14.6 (2.84) |

<0.001 | Ref | ||

| Zhang 2019 136 | China | 48 | Home‐based NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 68.3 (10.8) |

6 months |

Mean (SD), 32.4 (5.4) |

<0.01 | 0.22 |

| 48 | Outpatient NB‐UVB |

Mean (SD), 65.9 (10.8) |

6 months |

Mean (SD), 31.0 (5.8) |

<0.01 | Ref | ||

CDLQI, Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; MBEH, monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone; NA, not available/applicable; NB‐UVB, narrow‐band ultraviolet B; NS, not significant; OMP, oral minipulse; PC‐KUS, narrow‐band ultraviolet B‐activated pseudocatalase; PUVA, psoralen plus ultraviolet A; UVB, ultraviolet B; VitiQoL, Vitiligo‐specific Quality of Life.

Achieved meaningful score changes (4‐point score reduction) in DLQI score.

P value based on change from baseline.

Humanistic burden of caregivers

The FDLQI was used in four studies 51 , 149 , 151 , 152 ; the instrument can be administered to family members ≥16 years old. All studies reported mean scores in the overall population, which ranged from 6.1 to 14.4, 51 , 149 , 151 , 152 indicating moderate to very large effects of vitiligo on families and/or caregivers. The Dermatitis Family Impact (DFI) questionnaire was used in one study, 18 which showed significantly reduced QoL in parents of patients with vitiligo versus parents of healthy controls (P = 0.000). The Quality of Life in a Child’s Chronic Disease Questionnaire (QLCCDQ) for caregivers 149 and the Dermatological Family Impact Scale (DeFIS) 114 were each used in one study.

Discussion

This systematic literature review highlights the significance of QoL burden in patients with vitiligo. Despite no limitations on publication date, included studies addressing QoL in vitiligo were first published in 1996, indicating that interest in vitiligo‐related QoL only emerged in the last 25 years. Furthermore, only one‐quarter of included studies were interventional, showing limitation in the evaluation of patient perceptions in studies investigating treatment options.

Instruments used to quantify QoL included questionnaires (i.e. validated or study‐specific questionnaires) and visual analogue scales. The widespread use of validated instruments including the VitiQoL and DLQI enabled qualitative appraisal of burden in this systematic review. The most common instruments used to measure QoL in patients with vitiligo were dermatology‐specific, including the DLQI and CDLQI, as well as Skindex tools. Dermatology‐specific tools including the DLQI and Skindex account for physical symptoms such as itching, burning/stinging and pain, 40 , 117 which may not be present in patients with vitiligo, and may lack sensitivity for application in vitiligo. Vitiligo‐specific instruments were used in comparatively fewer studies, with the VitiQoL and VIS‐22 being the most common. Among studies that reported interpretable scores, vitiligo was estimated to have moderate or worse effects on patient QoL in a majority of studies (i.e. DLQI, 35/54 studies; Skindex, 8/8 studies; VitiQoL, 6/6 studies; VIS‐22, 3/3 studies). Vitiligo also had a significant impact on the QoL of families and/or caregivers; interpretable scores indicated moderate or worse effects of vitiligo on their QoL (i.e. FDLQI, 4/4 studies). Factors that were most commonly associated with reduced QoL in patients with vitiligo were female sex and lesions in visible or sensitive areas. It is notable that none of the aforementioned instruments were designed to differentiate among skin phototypes; this limitation is evident in the inconsistent reports of differences in QoL burden among patients with fair and dark skin phototypes. Another vitiligo‐specific instrument, the Vitiligo Impact Patient scale (VIPs; including the 29‐item VIPs and the 12‐item short‐form VIPs), includes response models for fair and dark skin. 153 , 154 However, the VIPs has not been applied in published studies beyond initial development and validation. Future studies quantifying QoL in vitiligo may benefit from the use of this cross‐culturally validated tool.

In interventional studies, treatment was generally shown to lessen the impact of vitiligo on QoL, but there were no trends indicating superiority of any type of treatment or longer treatment duration. A 2021 study showed that 94% of patients indicated the need for new and improved treatment modalities; half of the patients were not satisfied with currently available therapies and did not find them effective. 88 It follows that the impact of interventions on vitiligo is still limited and warrants further investigation. Repigmentation of vitiligo lesions is typically a slow process, and psychosocial stress together with previous treatment failure can affect long‐term treatment adherence. 4 The complexity of treatment regimens (including time taken to treat and experience satisfactory results) is expected to compound the burden experienced by patients and their caregivers. 155 Additionally, the likelihood of repigmentation is dependent on lesion location, with facial lesions being more responsive to treatment than lesions on the hands and feet. 156 , 157 It is also generally accepted that patient satisfaction is associated with near‐complete (≥80%) repigmentation. 158 , 159 It follows that QoL improvements may be minimal with less complete repigmentation, particularly in patients with lesions in visible and/or sensitive areas. Therefore, more effective treatments and an emphasis on patient well‐being and coping mechanisms are needed.

Limitations to this systematic review include the heterogeneity of studies and instruments used to determine QoL, particularly considering that included studies were published over a period of 25 years (1996–2021). Differences in reporting among studies, especially with regard to reporting of total scores versus subscales of instruments measuring QoL, limited the interpretation of results among studies. Furthermore, differences across geographical regions, cultures, skin colour, or gender perceptions of vitiligo and the subsequent impact on QoL were not always considered in studies.

In summary, vitiligo has clinically meaningful effects on the overall QoL of patients. Several studies using instruments with interpretable scores indicate that a majority of patients experience moderate to severe effects of vitiligo on their QoL. Although a breadth of instruments are used to measure QoL, the use of vitiligo‐specific instruments in the literature is limited. These findings highlight that greater attention should be dedicated to QoL decrement awareness and improvement of burden in patients with vitiligo.

Author contributions

All authors (MP, RHH, HJ, RM, MO and JS) contributed to the study design, developed the search strategy for the literature review, and took part in the development and drafting of the study and PROSPERO protocols. RM served as a contact for the PROSPERO protocol submission. All authors contributed to the interpretation of extracted data, drafting and critical appraisal of the manuscript and approved the final version for submission. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Search strategy.

Figure S1. Number of studies by year of publication*.

Figure S2. Number of studies by country and geographic region*.

Table S1. Generic quality‐of‐life assessment tools and outcomes among studies that reported total scores in the overall population.

Table S2. Generic quality‐of‐life assessment tools and outcomes in interventional studies.

Acknowledgements

Writing assistance was provided by Wendy van der Spuy, PhD, and Ken Wannemacher, PhD, of ICON (Blue Bell, PA, USA) and was funded by Incyte Corporation (Wilmington, DE, USA). The authors thank PrecisionHR (Carnegie, PA, USA) for data extraction support.

Conflicts of interest

MP has served as a consultant for Incyte Corporation and Pfizer, a principal investigator for Pfizer and PPM, and received non‐restricted research grants from Pierre Fabre and PPM. RHH has served as a principal investigator for Incyte Corporation and Pfizer and a subinvestigator for Immune Tolerance Network. HJ was an employee and shareholder of Incyte Corporation when the study was conducted. RM and MO are employees and shareholders of Incyte Corporation. JS has received grants and/or honoraria from AbbVie, Calypso Biotech, Bristol Myers Squibb, Incyte Corporation, LEO Pharma, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre‐Fabre, Sanofi, Sun Pharmaceuticals and Viela Bio; and has patents on MMP9 inhibitors and uses thereof in the prevention or treatment of a depigmenting disorder, and three‐dimensional model of depigmenting disorder.

Funding sources

The study was funded by Incyte Corporation, Wilmington, DE, USA, which was involved in design of the literature search, analysis of the search results, manuscript preparation and publication decisions in collaboration with the authors.

Data availability statement

All data were collected from published articles available in the public domain.

References

- 1. Spritz RA, Santorico SA. The genetic basis of vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol 2021; 141: 265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bergqvist C, Ezzedine K. Vitiligo: a focus on pathogenesis and its therapeutic implications. J Dermatol 2021; 48: 252–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rodrigues M, Ezzedine K, Hamzavi I et al. New discoveries in the pathogenesis and classification of vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 77: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taieb A, Alomar A, Böhm M et al. Guidelines for the management of vitiligo: the European Dermatology Forum consensus. Br J Dermatol 2013; 168: 5–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morrison B, Burden‐Teh E, Batchelor JM et al. Quality of life in people with vitiligo: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177: e338–e339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Osinubi O, Grainge MJ, Hong L et al. The prevalence of psychological comorbidity in people with vitiligo: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol 2018; 178: 863–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Jones H et al. Psychosocial effects of vitiligo: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Dermatol 2021; 22: 757–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ezzedine K, Sheth V, Rodrigues M et al. Vitiligo is not a cosmetic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 73: 883–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pajvani U, Ahmad N, Wiley A et al. The relationship between family medical history and childhood vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55: 238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Henning SW, Jaishankar D, Barse LW et al. The relationship between stress and vitiligo: Evaluating perceived stress and electronic medical record data. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0227909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohen SR, Mount BM, MacDonald N. Defining quality of life. Eur J Cancer 1996; 32a: 753–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sampogna F, Tabolli S, Abeni D. Impact of different skin conditions on quality of life. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2013; 148: 255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bae JM, Kim JE, Lee RW et al. Beyond quality of life: a call for patients' own willingness to pay in chronic skin disease to assess psychosocial burden – a multicenter, cross‐sectional, prospective survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 85: 1321–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beikert FC, Langenbruch AK, Radtke MA et al. Willingness to pay and quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res 2014; 306: 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Radtke MA, Schafer I, Gajur A et al. Willingness‐to‐pay and quality of life in patients with vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 2009; 161: 134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schoser B, Bilder DA, Dimmock D et al. The humanistic burden of Pompe disease: are there still unmet needs? A systematic review. BMC Neurol 2017; 17: 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Amer AA, McHepange UO, Gao XH et al. Hidden victims of childhood vitiligo: impact on parents' mental health and quality of life. Acta Derm Venereol 2015; 95: 322–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dertlioglu SB, Cicek D, Balci DD et al. Dermatology Life Quality Index scores in children with vitiligo: comparison with atopic dermatitis and healthy control subjects. Int J Dermatol 2013; 52: 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hamidizadeh N, Ranjbar S, Ghanizadeh A et al. Evaluating prevalence of depression, anxiety and hopelessness in patients with vitiligo on an Iranian population. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2020; 18: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karelson M, Silm H, Kingo K. Quality of life and emotional state in vitiligo in an Estonian sample: comparison with psoriasis and healthy controls. Acta Derm Venereol 2013; 93: 446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kruger C, Schallreuter KU. Stigmatisation, avoidance behaviour and difficulties in coping are common among adult patients with vitiligo. Acta Derm Venereol 2015; 95: 553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krüger C, Schallreuter KU. Increased levels of anxious‐depressive mood in parents of children with vitiligo. Eur J Pediatr Dermatol 2018; 28: 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kruger C, Panske A, Schallreuter KU. Disease‐related behavioral patterns and experiences affect quality of life in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Int J Dermatol 2014; 53: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kruger C, Smythe JW, Spencer JD et al. Significant immediate and long‐term improvement in quality of life and disease coping in patients with vitiligo after group climatotherapy at the Dead Sea. Acta Derm Venereol 2011; 91: 152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Noh S, Kim M, Park CO et al. Comparison of the psychological impacts of asymptomatic and symptomatic cutaneous diseases: vitiligo and atopic dermatitis. Ann Dermatol 2013; 25: 454–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Önen Ö, Kundak S, Özek Erkuran H et al. Quality of life, depression, and anxiety in Turkish children with vitiligo and their parents. Psychiatr Clin Psychopharmacol 2018; 29: 492–501. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sangma LN, Nath J, Bhagabati D. Quality of life and psychological morbidity in vitiligo patients: a study in a teaching hospital from north‐East India. Indian J Dermatol 2015; 60: 142–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang Y, Zapata L, Rodgers C et al. Quality of life in patients with vitiligo using the short form‐36. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177: 1764–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yucel D, Sener S, Turkmen D et al. Evaluation of the Dermatological Life Quality Index, sexual dysfunction and other psychiatric diseases in patients diagnosed with vitiligo with and without genital involvement. Clin Exp Dermatol 2021; 46: 669–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Balieva F, Kupfer J, Lien L et al. The burden of common skin diseases assessed with the EQ5D: a European multicentre study in 13 countries. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176: 1170–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bilgic O, Bilgic A, Akis HK et al. Depression, anxiety and health‐related quality of life in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Clin Exp Dermatol 2011; 36: 360–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Linthorst Homan MW, de Korte J, Grootenhuis MA et al. Impact of childhood vitiligo on adult life. Br J Dermatol 2008; 159: 915–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ucuz I, Altunisik N, Sener S et al. Quality of life, emotion dysregulation, attention deficit and psychiatric comorbidity in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Clin Exp Dermatol 2021; 46: 510–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang KY, Wang KH, Zhang ZP. Health‐related quality of life and marital quality of vitiligo patients in China. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011; 25: 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dabas G, Vinay K, Parsad D et al. Psychological disturbances in patients with pigmentary disorders: a cross‐sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: 392–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ghajarzadeh M, Ghiasi M, Kheirkhah S. Associations between skin diseases and quality of life: a comparison of psoriasis, vitiligo, and alopecia areata. Acta Med Iran 2012; 50: 511–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ongenae K, Van Geel N, De Schepper S et al. Effect of vitiligo on self‐reported health‐related quality of life. Br J Dermatol 2005; 152: 1165–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xu ST, Oh EH, Kim JE et al. Comparative study of quality of life between psoriasis, vitiligo and autoimmune bullous disease. Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol 2017; 25: 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994; 19: 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lewis‐Jones MS, Finlay AY. The Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol 1995; 132: 942–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Basra MK, Sue‐Ho R, Finlay AY. The Family Dermatology Life Quality Index: measuring the secondary impact of skin disease. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156: 528–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Agarwal S, Ramam M, Sharma VK et al. A randomized placebo‐controlled double‐blind study of levamisole in the treatment of limited and slowly spreading vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 2005; 153: 163–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aghaei S, Sodaifi M, Jafari P et al. DLQI scores in vitiligo: reliability and validity of the Persian version. BMC Dermatol 2004; 4: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Akdeniz N, Yavuz IH, Gunes Bilgili S et al. Comparison of efficacy of narrow band UVB therapies with UVB alone, in combination with calcipotriol, and with betamethasone and calcipotriol in vitiligo. J Dermatolog Treat 2014; 25: 196–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Al Robaee AA. Assessment of quality of life in Saudi patients with vitiligo in a medical school in Qassim province, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2007; 28: 1414–1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Al‐Shobaili HA. Treatment of vitiligo patients by excimer laser improves patients' quality of life. J Cutan Med Surg 2015; 19: 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Amatya B, Pokhrel DB. Assessment and comparison of quality of life in patients with melasma and vitiligo. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2019; 17: 114–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Anaba EL, Oaku RI. Prospective cross‐sectional study of quality of life of vitiligo patients using a vitiligo specific quality of life instrument. West Afr J Med 2020; 37: 745–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bassiouny D, Hegazy R, Esmat S et al. Cosmetic camouflage as an adjuvant to vitiligo therapies: effect on quality of life. J Cosmet Dermatol 2021; 20: 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bin Saif GA, Al‐Balbeesi AO, Binshabaib R et al. Quality of life in family members of vitiligo patients: a questionnaire study in Saudi Arabia. Am J Clin Dermatol 2013; 14: 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bonotis K, Pantelis K, Karaoulanis S et al. Investigation of factors associated with health‐related quality of life and psychological distress in vitiligo. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2016; 14: 45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Boza JC, Kundu RV, Fabbrin A et al. Translation, cross‐cultural adaptation and validation of the vitiligo‐specific health‐related quality of life instrument (VitiQoL) into Brazilian Portuguese. An Bras Dermatol 2015; 90: 358–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Budania A, Parsad D, Kanwar AJ et al. Comparison between autologous noncultured epidermal cell suspension and suction blister epidermal grafting in stable vitiligo: a randomized study. Br J Dermatol 2012; 167: 1295–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Catucci Boza J, Giongo N, Machado P et al. Quality of life impairment in children and adults with vitiligo: a cross‐sectional study based on dermatology‐specific and disease‐specific quality of life instruments. Dermatology 2016; 232: 619–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cavalie M, Ezzedine K, Fontas E et al. Maintenance therapy of adult vitiligo with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment: a randomized, double blind, placebo‐controlled study. J Invest Dermatol 2015; 135: 970–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chahar YS, Singh PK, Sonkar VK et al. Impact on quality of life in vitiligo patients treated with narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. Indian J Dermatol 2018; 63: 399–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chan MF, Thng TG, Aw CW et al. Investigating factors associated with quality of life of vitiligo patients in Singapore. Int J Nurs Pract 2013; 19(Suppl 3): 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chan MF, Chua TL, Goh BK et al. Investigating factors associated with depression of vitiligo patients in Singapore. J Clin Nurs 2012; 21: 1614–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chen D, Tuan H, Zhou EY et al. Quality of life of adult vitiligo patients using camouflage: a survey in a Chinese vitiligo community. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0210581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Doʇruk Kaçar S, Özuʇuz P, Baʇcioʇlu E et al. Is a poor Dermatology Life Quality Index score a sign of stigmatization in patients with vitiligo? Turkiye Klinikleri Dermatoloji 2014; 24: 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dolatshahi M, Ghazi P, Feizy V et al. Life quality assessment among patients with vitiligo: comparison of married and single patients in Iran. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008; 74: 700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Eleftheriadou V, Thomas K, Ravenscroft J et al. Feasibility, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, multi‐centre trial of hand‐held NB‐UVB phototherapy for the treatment of vitiligo at home (HI‐Light trial: home intervention of light therapy). Trials 2014; 15: 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ezzedine K, Grimes PE, Meurant JM et al. Living with vitiligo: results from a national survey indicate differences between skin phototypes. Br J Dermatol 2015; 173: 607–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Fawzy MM, Hegazy RA. Impact of vitiligo on the health‐related quality of life of 104 adult patients, using Dermatology Life Quality Index and stress score: first Egyptian report. Eur J Dermatol 2013; 23: 733–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ghaderi R, Saadatjoo A. Evaluating of life quality in Iranian patients with vitiligo using generic and special questionnaires. Shiraz E‐Med J 2014; 15: e22359. 10.17795/semj22359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gupta V, Sreenivas V, Mehta M et al. Measurement properties of the Vitiligo Impact Scale‐22 (VIS‐22), a vitiligo‐specific quality‐of‐life instrument. Br J Dermatol 2014; 171: 1084–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gupta V, Sreenivas V, Mehta M et al. What do Vitiligo Impact Scale‐22 scores mean? Studying the clinical interpretation of scores using an anchor‐based approach. Br J Dermatol 2019; 180: 580–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gupta AK, Pandey SS, Pandey BL. Effectiveness of vitiligo therapy in prospective observational study of 250 cases with review of consensus and individualized care perspective. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2013; 23: 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hartmann A, Brocker EB, Hamm H. Occlusive treatment enhances efficacy of tacrolimus 0.1% ointment in adult patients with vitiligo: results of a placebo‐controlled 12‐month prospective study. Acta Derm Venereol 2008; 88: 474–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hartmann A, Lurz C, Hamm H et al. Narrow‐band UVB311 nm vs. broad‐band UVB therapy in combination with topical calcipotriol vs. placebo in vitiligo. Int J Dermatol 2005; 44: 736–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hosseinkhani A, Montaseri H, Sodaifi M et al. A randomized double blind clinical trial on a Sabgh formulation for patients with vitiligo. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 2015; 20: 254–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ibrahim S, El Mofty M, Mostafa W et al. Monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone 20 and 40% cream in depigmentation of patients with vitiligo: a randomized controlled trial. J Egypt Womens Dermatol Soc 2020; 17: 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ingordo V, Cazzaniga S, Medri M et al. To what extent is quality of life impaired in vitiligo? A multicenter study on Italian patients using the Dermatology Life Quality Index. Dermatology 2014; 229: 240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ingordo V, Cazzaniga S, Gentile C et al. Dermatology Life Quality Index score in vitiligo patients: a pilot study among young Italian males. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2012; 147: 83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kent G, Al'Abadie M. Psychologic effects of vitiligo: a critical incident analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996; 35: 895–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kent G, Al‐abadie M. Factors affecting responses on Dermatology Life Quality Index items among vitiligo sufferers. Clin Exp Dermatol 1996; 21: 330–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kiprono S, Chaula B, Makwaya C et al. Quality of life of patients with vitiligo attending the Regional Dermatology Training Center in Northern Tanzania. Int J Dermatol 2013; 52: 191–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kostopoulou P, Jouary T, Quintard B et al. Objective vs. subjective factors in the psychological impact of vitiligo: the experience from a French referral centre. Br J Dermatol 2009; 161: 128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kota RS, Vora RV, Varma JR et al. Study on assessment of quality of life and depression in patients of vitiligo. Indian Dermatol Online J 2019; 10: 153–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Krishna GS, Ramam M, Mehta M et al. Vitiligo Impact Scale: an instrument to assess the psychosocial burden of vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2013; 79: 205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lilly E, Lu PD, Borovicka JH et al. Development and validation of a vitiligo‐specific quality‐of‐life instrument (VitiQoL). J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 69: e11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mashayekhi V, Javidi Z, Kiafar B et al. Quality of life in patients with vitiligo: a descriptive study on 83 patients attending a PUVA therapy unit in Imam Reza Hospital, Mashad. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2010; 76: 592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Mishra N, Rastogi MK, Gahalaut P et al. Dermatology specific quality of life in vitiligo patients and its relation with various variables: a hospital based cross‐sectional study. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8:YC01‐03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Morales‐Sanchez MA, Vargas‐Salinas M, Peralta‐Pedrero ML et al. Impact of vitiligo on quality of life. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2017; 108: 637–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mou KH, Han D, Liu WL et al. Combination therapy of orally administered glycyrrhizin and UVB improved active‐stage generalized vitiligo. Braz J Med Biol Res 2016; 49: e5354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Narahari SR, Prasanna KS, Aggithaya MG et al. Dermatology Life Quality Index does not reflect quality of life status of Indian vitiligo patients. Indian J Dermatol 2016; 61: 99–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Narayan VS, Uitentuis SE, Luiten RM et al. Patients' perspective on current treatments and demand for novel treatments in vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021; 35: 744–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ongenae K, Dierckxsens L, Brochez L et al. Quality of life and stigmatization profile in a cohort of vitiligo patients and effect of the use of camouflage. Dermatology 2005; 210: 279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Papadopoulos L, Bor R, Legg C. Coping with the disfiguring effects of vitiligo: a preliminary investigation into the effects of cognitive‐behavioural therapy. Br J Med Psychol 1999; 72(Pt 3): 385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Parsad D, Pandhi R, Dogra S et al. Dermatology Life Quality Index score in vitiligo and its impact on the treatment outcome. Br J Dermatol 2003; 148: 373–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ramakrishna P, Rajni T. Psychiatric morbidity and quality of life in vitiligo patients. Indian J Psychol Med 2014; 36: 302–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Sahni K, Parsad D, Kanwar AJ et al. Autologous noncultured melanocyte transplantation for stable vitiligo: can suspending autologous melanocytes in the patients' own serum improve repigmentation and patient satisfaction? Dermatol Surg 2011; 37: 176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Salman A, Kurt E, Topcuoglu V et al. Social anxiety and quality of life in vitiligo and acne patients with facial involvement: a cross‐sectional controlled study. Am J Clin Dermatol 2016; 17: 305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Sarhan D, Mohammed GF, Gomaa AH et al. Female genital dialogues: female genital self‐image, sexual dysfunction, and quality of life in patients with vitiligo with and without genital affection. J Sex Marital Ther 2016; 42: 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Sawant NS, Vanjari NA, Khopkar U. Gender differences in depression, coping, stigma, and quality of life in patients of vitiligo. Dermatol Res Pract 2019; 2019: 6879412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Senol A, Yucelten AD, Ay P. Development of a quality of life scale for vitiligo. Dermatology 2013; 226: 185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Shah R, Hunt J, Webb TL et al. Starting to develop self‐help for social anxiety associated with vitiligo: using clinical significance to measure the potential effectiveness of enhanced psychological self‐help. Br J Dermatol 2014; 171: 332–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Silpa‐Archa N, Pruksaeakanan C, Angkoolpakdeekul N et al. Relationship between depression and quality of life among vitiligo patients: a self‐assessment questionnaire‐based study. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2020; 13: 511–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Association between vitiligo extent and distribution and quality‐of‐life impairment. JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149: 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Tanioka M, Yamamoto Y, Kato M et al. Camouflage for patients with vitiligo vulgaris improved their quality of life. J Cosmet Dermatol 2010; 9: 72–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Tejada CDS, Mendoza‐Sassi RA, Almeida HL, Jr et al. Impact on the quality of life of dermatological patients in southern Brazil. An Bras Dermatol 2011; 86: 1113–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Temel A, Bozkurt S, Senol Y et al. Internalized stigma in patients with acne vulgaris, vitiligo, and alopecia areata. Turk J Dermatol 2019; 13: 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Udaya Kiran K, Potharaju AR, Vellala M et al. Cosmetic camouflage of visible skin lesions enhances life quality indices in leprosy as in vitiligo patients: an effective stigma reduction strategy. Lepr Rev 2020; 91: 343–352. [Google Scholar]

- 105. van Geel N, Ongenae K, Vander Haeghen Y et al. Subjective and objective evaluation of noncultured epidermal cellular grafting for repigmenting vitiligo. Dermatology 2006; 213: 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. van Geel N, Uitentuis SE, Zuidgeest M et al. Validation of a patient global assessment for extent, severity and impact to define the severity strata for the Self Assessment Vitiligo Extent Score (SA‐VES). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021; 35: 216–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Wong SM, Baba R. Quality of life among Malaysian patients with vitiligo. Int J Dermatol 2012; 51: 158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Yones SS, Palmer RA, Garibaldinos TM et al. Randomized double‐blind trial of treatment of vitiligo: efficacy of psoralen‐UV‐A therapy vs narrowband‐UV‐B therapy. Arch Dermatol 2007; 143: 578–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Zabetian S, Jacobson G, Lim HW et al. Quality of life in a vitiligo support group. J Drugs Dermatol 2017; 16: 344–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Zandi S, Farajzadeh S, Saberi N. Effect of vitiligo on self reported quality of life in southern part of Iran. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2011; 21: 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 111. Manzoni AP, Pereira RL, Townsend RZ et al. Assessment of the quality of life of pediatric patients with the major chronic childhood skin diseases. An Bras Dermatol 2012; 87: 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Njoo MD, Bos JD, Westerhof W. Treatment of generalized vitiligo in children with narrow‐band (TL‐01) UVB radiation therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 42: 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Ramien ML, Ondrejchak S, Gendron R et al. Quality of life in pediatric patients before and after cosmetic camouflage of visible skin conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71: 935–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Savas Erdogan S, Falay Gur T, Dogan B. Anxiety and depression in pediatric patients with vitiligo and alopecia areata and their parents: a cross‐sectional controlled study. J Cosmet Dermatol 2021; 20: 2232–2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Quality of life impairment in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Pediatr Dermatol 2014; 31: 309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Borimnejad L, Parsa Yekta Z, Nikbakht‐Nasrabadi A et al. Quality of life with vitiligo: comparison of male and female Muslim patients in Iran. Gend Med 2006; 3: 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Chren M‐M. The Skindex instruments to measure the effects of skin disease on quality of life. Dermatol Clin 2012; 30: 231–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Nijsten T, Sampogna F, Abeni D. Categorization of Skindex‐29 scores using mixture analysis. Dermatology 2009; 218: 151–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Bae JM, Lee SC, Kim TH et al. Factors affecting quality of life in patients with vitiligo: a nationwide study. Br J Dermatol 2018; 178: 238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Batchelor JM, Thomas KS, Akram P et al. Home‐based narrowband UVB, topical corticosteroid or combination for children and adults with vitiligo: HI‐Light vitiligo three‐arm RCT. Health Technol Assess 2020; 24: 1–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Choi S, Kim DY, Whang SH et al. Quality of life and psychological adaptation of Korean adolescents with vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24: 524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Kim DY, Lee JW, Whang SH et al. Quality of life for Korean patients with vitiligo: Skindex‐29 and its correlation with clinical profiles. J Dermatol 2009; 36: 317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Komen L, van der Kraaij GE, van der Veen JP et al. The validity, reliability and acceptability of the SAVASI; a new self‐assessment score in vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29: 2145–2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Linthorst Homan MW, Sprangers MA, de Korte J et al. Characteristics of patients with universal vitiligo and health‐related quality of life. Arch Dermatol 2008; 144: 1062–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Linthorst Homan MW, Spuls PI, de Korte J et al. The burden of vitiligo: patient characteristics associated with quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 61: 411–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Middelkamp‐Hup MA, Bos JD, Rius‐Diaz F et al. Treatment of vitiligo vulgaris with narrow‐band UVB and oral Polypodium leucotomos extract: a randomized double‐blind placebo‐controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007; 21: 942–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Sampogna F, Raskovic D, Guerra L et al. Identification of categories at risk for high quality of life impairment in patients with vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 2008; 159: 351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Sampogna F, Picardi A, Chren MM et al. Association between poorer quality of life and psychiatric morbidity in patients with different dermatological conditions. Psychosom Med 2004; 66: 620–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Sanclemente G, Burgos C, Nova J et al. The impact of skin diseases on quality of life: a multicenter study. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2017; 108: 244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Sassi F, Cazzaniga S, Tessari G et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of 308‐nm excimer laser alone or in combination with topical hydrocortisone 17‐butyrate cream in the treatment of vitiligo of the face and neck. Br J Dermatol 2008; 159: 1186–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Essa N, Awad S, Nashaat M. Validation of an Egyptian Arabic version of Skindex‐16 and quality of life measurement in Egyptian patients with skin disease. Int J Behav Med 2018; 25: 243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Florez‐Pollack S, Jia G, Zapata L, Jr et al. Association of quality of life and location of lesions in patients with vitiligo. JAMA Dermatol 2017; 153: 341–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Hedayat K, Karbakhsh M, Ghiasi M et al. Quality of life in patients with vitiligo: a cross‐sectional study based on vitiligo quality of life index (VitiQoL). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016; 14: 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Liu B, Sun Y, Song J et al. Home vs hospital narrowband UVB treatment by a hand‐held unit for new‐onset vitiligo: a pilot randomized controlled study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2020; 36: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Pun J, Randhawa A, Kumar A et al. The impact of vitiligo on quality of life and psychosocial well‐being in a Nepalese population. Dermatol Clin 2021; 39: 117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Zhang L, Wang X, Chen S et al. Comparison of efficacy and safety profile for home NB‐UVB vs. outpatient NB‐UVB in the treatment of non‐segmental vitiligo: a prospective cohort study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2019; 35: 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Hans A, Reddy KA, Black SM et al. Transcultural assessment of quality of life in patients with vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 2022; 86: P1114–P1116. 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA. The PedsQL: measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Med Care 1999; 37: 126–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]