Abstract

Binge eating disorder (BED) is characterized by regular binge-eating episodes during which individuals ingest comparably large amounts of food and experience loss of control over their eating behavior. The worldwide prevalence of BED for the years 2018 – 2020 is estimated to be 0.6–1.8% in adult women and 0.3–0.7% in adult men. BED is commonly associated with obesity and with somatic and mental health comorbidities. People with BED experience considerable burden and impairments in quality of life, at the same time, BED often goes undetected and untreated. The aetiology of BED is complex, including genetic and environmental factors as well as neuroendocrinological and neurobiological contributions. Neurobiological findings highlight impairments in reward processing, inhibitory control and emotion regulation in people with BED, and these neurobiological domains are targets for emerging treatment approaches. Psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for BED. Recognition and research on BED has increased since its inclusion into DSM-5; however, continuing efforts are needed to understand underlying mechanisms of BED and to improve prevention and treatment outcomes for this disorder. These efforts should also include screening, identification, and implementation of evidence-based interventions in routine clinical practice settings like primary care and mental health outpatient clinics.

Introduction

Binge-eating disorder (BED) is an eating disorder that was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 20131 and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) in 20192 (Figure 1, Table 1 and Box 1). The core psychopathology characterizing BED includes regular binge-eating episodes during which individuals ingest comparably large amounts of food in a discrete time period (such as within any 2-hour period), whilst experiencing loss of control over their eating behaviour1. To fulfill the diagnosis according to DSM-5 criteria1, these episodes have to occur at least once a week for at least three months and have to be associated with distress regarding binge-eating (Table 1). Moreover, DSM-5-defined binge-eating episodes are associated with at least three of the following five characteristics: eating much more rapidly than normal, eating until feeling uncomfortably full, eating despite not feeling physically hungry, eating alone because of embarrassment about the amount and negative feelings after overeating1. BED and the eating disorder bulimia nervosa (BN) are both characterized by regular binge-eating episodes1; however, the regular use of one or more inappropriate compensatory behaviours to prevent weight gain (such as self-induced vomiting or fasting) is part of the diagnostic criteria for BN1, whereas individuals with BED do not regularly compensate using inappropriate methods. Moreover, diagnostic criteria for the eating disorders anorexia nervosa (AN)3,4 and BN also include disturbances associated with body image (such as overevaluation of weight and shape), which is not required for a BED diagnosis1.

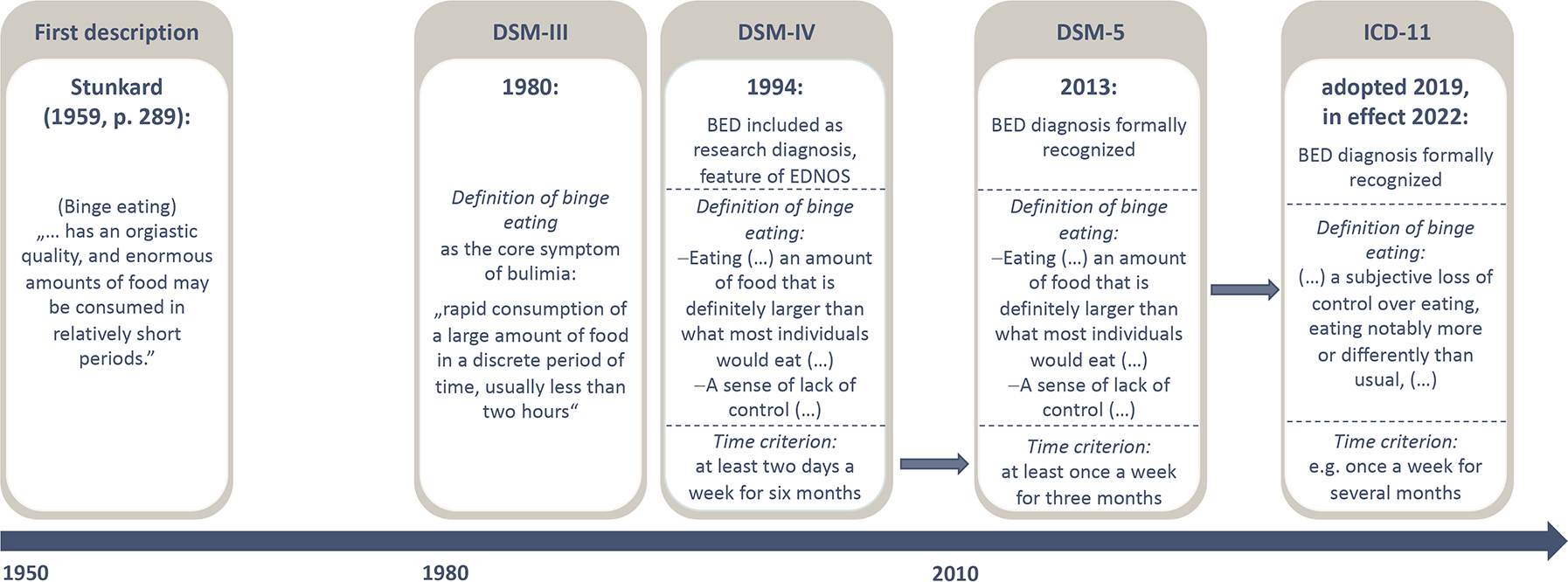

Figure 1: Timeline of the evolution of classification criteria for BED.

The first description of binge eating is attributed to the American psychiatrist Albert J Stunkard in the late 1950s237, while another American psychiatrist, Walter W Hamburger, a few years earlier laid the foundation for the understanding that obesity entails also emotional aspects238. These early notions focus on binge eating as a behaviour, and it took two decades until binge eating was introduced as a core symptom of an eating disorder, bulimia nervosa (BN), in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)239. Fourteen years later, BED was included as a research diagnosis into the fourth edition of the DSM240, including a more specified definition of binge eating as a core psychopathology and a time criterion. BED was finally recognized as an official diagnosis in DSM-5 a decade later1. Compared with the research criteria, the DSM-5 criteria include a loosening of the time criterion with binge eating episodes occurring at least once a week over three months necessary to fulfil the diagnosis. BED is also included in the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11)2. The ICD has loosened criteria around the ‘large amount’ of food ingested, allowing subjective binge eating2, which will put challenges towards consistent application of diagnostic criteria. EDNOS, eating disorder not otherwise specified.

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria (reduced version) of BED and differential eating disorder diagnoses according to DSM-5.

| Criterion | BED | BN | AN |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both: Eating in a discrete period of time, an amount of food that is definitely larger than what most individuals would eat A sense of lack of control over eating |

Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both: Eating in a discrete period of time, an amount of food that is definitely larger than what most individuals would eat A sense of lack of control over eating |

Restriction of energy intake relative to requirements, leading to a significantly low body weight |

| B | Binge eating episodes are associated with three or more of the following: 1. eating much more rapidly 2. feeling uncomfortably full 3. not feeling physically hungry 4. alone because of feeling embarrassed 5. Feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or very guilty afterwards |

Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications, fasting, or excessive exercise. | Intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat, or persistent behaviour that interferes with weight gain, even though at a significantly low weight. |

| C | Marked distress regarding binge eating is present. | The binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors both occur, on average, at least once a week for 3 months. | Disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or persistent lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current low body weight |

| D | The binge eating occurs, on average, at least once a week for 3 months. | Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape and weight. | |

| E | does not occur exclusively during the course of bulimia nervosa or anorexia nervosa | does not occur exclusively during episodes of anorexia nervosa | |

| Specifier |

Restricting type: During the last three months, the individual has not engaged in recurrent episodes of binge eating or purging behaviour; weight loss is accomplished primarily through dieting, fasting and/or excessive exercise. Binge-eating/purging type: During the last three months the individual has engaged in recurrent episodes of binge eating or purging behaviour. |

AN: Anorexia Nervosa, BED: Binge Eating Disorder, BN: Bulimia Nervosa. Similarities between BED and BN (green), similarities between BN and AN (purple) and differences between BED and BN/AN (blue)

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Box 1: ICD-11 criteria for BED.

Binge eating disorder is characterized by frequent, recurrent episodes of binge eating (such as once a week or more over a period of several months). A binge eating episode is a distinct period of time during which the individual experiences a subjective loss of control over eating, eating notably more or differently than usual, and feels unable to stop eating or limit the type or amount of food eaten. Binge eating is experienced as very distressing, and is often accompanied by negative emotions such as guilt or disgust. However, unlike in bulimia nervosa, binge eating episodes are not regularly followed by inappropriate compensatory behaviours aimed at preventing weight gain (such as self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives or enemas or strenuous exercise).

Similar to other mental disorders, the pathophysiology of BED is complex and multifactorial, with biological, individual and social variables contributing to dysregulated eating and other related behaviours. Dysfunctions across the spectrum of impulsivity might lie at the core of BED, which include alterations related to reward processing, inhibitory control and emotion regulation.

BED constitutes an important health issue as it is highly prevalent in the general population5–7 and is often associated with obesity and extreme obesity7. Indeed, up to 30% of individuals with obesity seeking behavioural or surgical weight loss treatment have co-occurring BED8,9. This highlights the clinical importance of BED, especially given that average Body Mass Index (BMI) continues to rise globally10 and the World Health Organization has identified the worldwide obesity ‘epidemic’ as one of the major global health problems11. However, although elevated BMI is associated with BED, weight loss as a treatment outcome for BED is controversial, with guidelines prioritizing behavioral outcomes such as reduction in or abstinence from binge-eating as a primary treatment goal for BED12,13.

This Primer focuses on the epidemiology, comorbidities, etiological and maintenance mechanisms of BED, as well as diagnosis, screening, prevention and management approaches for BED and quality of life of individuals with this disorder. The Primer predominantly focuses on BED in adults. As research into BED is rapidly expanding, we also outline emerging fields of research, particularly regarding novel innovative treatment approaches. Moreover, owing to the frequent comorbidity of BED with obesity, this Primer outlines the differential diagnosis and management of BED across the obesity spectrum; however, it will not give a general overview on the evidence related to treatment of obesity as this topic has been covered previously14.

Epidemiology

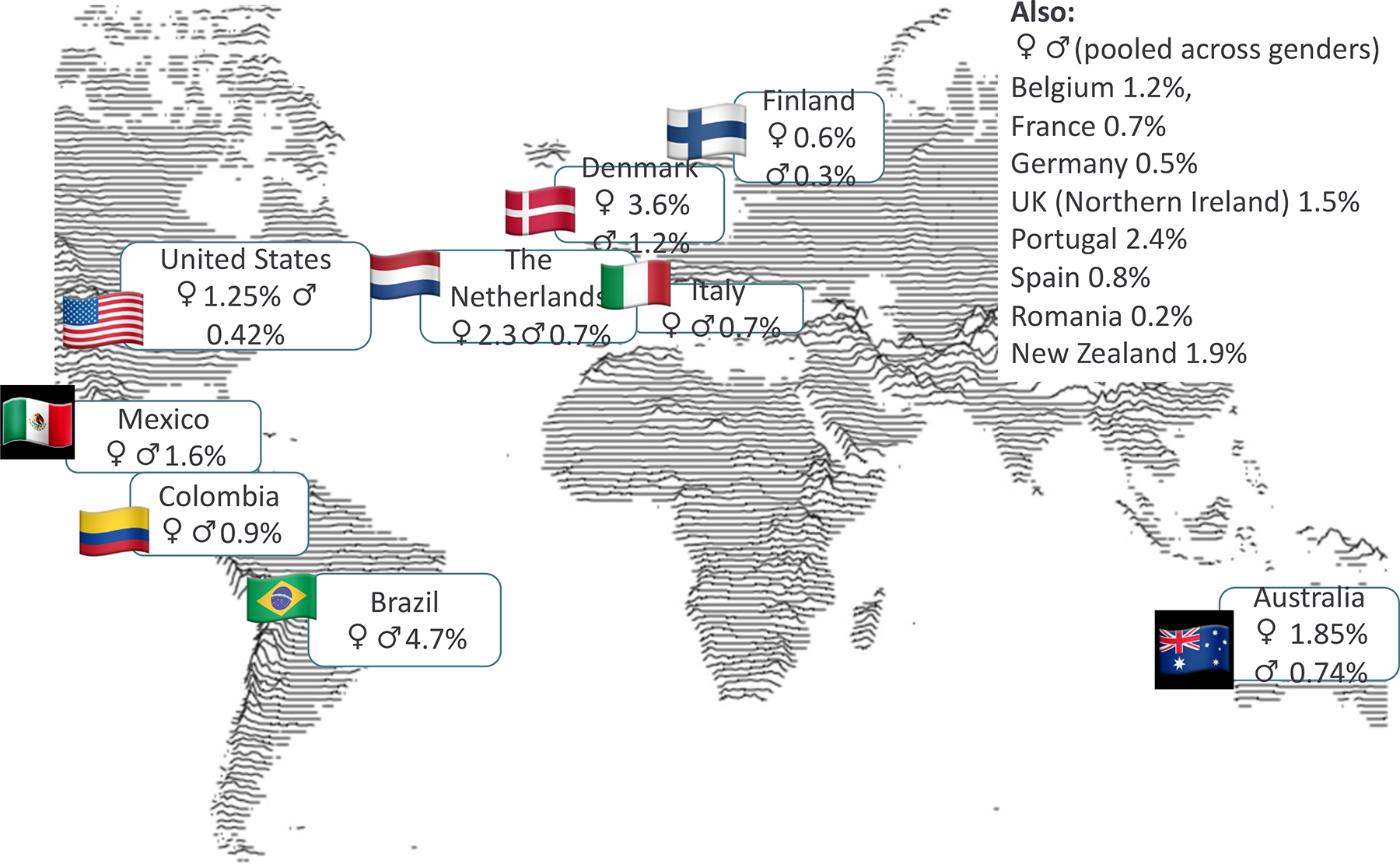

The epidemiology of BED is still emerging. Although BED has a high prevalence and causes significant burden, it was not included in the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 201915. Present understanding of the epidemiology of BED is from clinical and community-based studies conducted in North America, Australia and Europe. Data from other parts of the world are preliminary. Estimates of the prevalence of BED are highly disparate between geographical regions (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Lifetime prevalence of binge eating disorder.

World map displaying lifetime prevalence for binge eating disorder (BED) for different regions 19,241–244. For most regions, only the pooled lifetime prevalence (an average of male and female prevalence) is available.

Prevalence and incidence

The incidence of BED ranges from 35 to 343 per 100,000 person-years, but these estimates are based on only two studies of young women between ages 10 and 24.16,17 The World Mental Health Survey18 provided the first population-based estimates of the prevalence and correlates of BED among adults in different countries and found that prevalence estimates varied widely across regions. One meta-analysis of studies completed before 2018 found an estimated past-year prevalence of DSM-5 BED in adults of 1.3% (95% CI 0.6–2.3%), 0.3% (95% CI 0.1–0.6%) in men and 1.5% (95% CI 1.2–1.7%) in women5. However, methodologically rigorous population-based studies of BED completed after the meta-analysis have arrived at widely varying estimates of 0.2–3.6% in women and 0.03–1.2% in men19.

The highest past-year prevalence of BED has been found in adolescents, with a prevalence of 1.8–3.6% in girls, 1.5% in gender-diverse youths and 0.2–1.2% in boys 20,21. Symptoms of BED in adolescents may be transient. In support of this, one longitudinal community study found that 6.1% of adolescent girls met DSM-5 criteria for BED in at least one assessment but only few met BED criteria over time22.

One potential explanation for widely varying estimates of BED occurrence is a social constructivist view of psychiatric diagnoses. Psychiatric diagnoses try to make meaning out of information that is inherently ambiguous and dynamic and more likely to reflect the diagnostician’s training and context than underlying biological mechanisms. For this reason, a careful study of local meanings and conditions is important. Critical researchers have also pointed out that the construct BED is deeply rooted in Western consumer culture23. For this reason, the global relevance of BED is still unclear.

Burden of disease, deaths and morbidity

BED is associated with a considerable burden of disease and excess mortality15,24. Reports of specialist clinics in Europe estimate that the standardized mortality ratio associated with BED is 1.50 (95% CI 0.87–2.40)9 to 1.77 (95% CI 0.60–5.27)8. Despite this high mortality ratio, the healthcare needs of individuals with BED are rarely met. Indeed, <10–50% of individuals with BED receive care in high-income countries16,25,26, perhaps because care of individuals with BED often requires highly specialized expertise.

Co-occurring conditions and mental health issues

In a nationally representative study of US adults, past-year health conditions commonly co-occurring with BED included obesity, hypertension (31%), various heart conditions (17%), arthritis (24%), elevated cholesterol (27%) and triglycerides (15%), diabetes mellitus (14%), smoking (40%), sleep problems (29%) and general poor health. Obesity and metabolic syndrome are common consequences of BED. The metabolic syndrome refers to a clustering of at least three of the following five medical conditions: abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, high blood sugar, high serum triglycerides, and low serum high-density lipoprotein. BED is common in individuals with Type 2 diabetes27 and candidates for obesity surgery28. In a nationally representative study of US adults, the mean body mass index of participants with BED was 33.9 kg/m27.

Studies of individuals with BED demonstrated increased metabolic and inflammatory markers associated with increased morbidity and mortality29. Up to 20% of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have an underlying, yet often undetected, eating disorder, the most common of which is BED 30. This is especially relevant as binge-eating behaviours worsen metabolic markers, including glycemic control30. Moreover, type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and other autoimmune disorders are also more common in individuals with BED than controls31. In two pilot studies, 23%32 to 28%33 of people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) screened positive for BED, with this pattern of comorbidity probably arising from shared risk factors including obesity, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and an unfavourable body composition33.

Individuals with BED in the general population report a range of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including dysphagia, acid reflux, bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation and lower GI urgency34. BED seems to be associated with both upper and lower GI symptoms, independent of the level of obesity34. Additionally, respiratory (30%) and musculoskeletal problems (21%) are significantly increased in patients with BED compared with the general population35. Moreover, patients with BED—particularly due to obesity and increased risk for T2D—have multiple risk factors for cancer, including colorectal cancer, esophageal adenocarcinoma, pancreas and liver cancer, as well as cancer of the gallbladder, kidney, postmenopausal breast, endometrial, thyroid, ovarian, and prostate cancer29. Other health concerns in patients with BED includes urinary incontinence as well as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), which is associated with insulin resistance and increased risk of infertility36. Between 17 and 23 % of patients with PCOS meet criteria for BED36.

BED often co-occurs with other mental health conditions. In a nationally representative study of US-based adults, 94% of individuals with BED met diagnostic criteria for at least one additional psychiatric disorder37 and 23% of individuals with BED had attempted suicide 38. Common comorbid mental health conditions of BED include lifetime mood disorders (70%), post-traumatic stress disorder (32%) and anxiety disorders (16%) 37. Disorders characterized by poor impulse control39 are also frequent, including borderline personality disorder37, alcohol use disorder 37 and pathological gambling40. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) also co-exists with BED41. In particular, individuals with BED who seek obesity surgery report serious problems with impulse control before surgery, such as intermittent explosive disorder, gambling and compulsive buying42.

Similar to with other mental disorders, the temporal order of the emergence of comorbid conditions is often difficult to disentangle and they might even dynamically evolve together as, in the case of BED, for instance there is considerable neurobiological overlap in the regulation of mood and food intake. Psychiatric comorbidity is associated with more severe BED pathology as patients with BED and comorbid mood disorders are less likely to remit43 and, therefore, might need different or additional treatments. Of note, mental health comorbidity does not moderate weight loss in patients with BED43. Depending on the complexity of the comorbidity pattern, the primary condition should be clarified and treatments prescribed accordingly.

Sociodemographic factors

Most research on BED has been conducted in the US, where BED is prevalent in all socioeconomic groups44. Issues with weight and weight-related teasing, body dissatisfaction and dieting are key risk factors for binge-eating45. Over-evaluation of weight and body shape is associated with greater BED-related functional impairment46. Moreover, people who have experienced poverty, violence, traumatic events, combat, food insecurity or major mental illness seem to be at an increased risk of BED47–52. Several mostly US-based reports suggest that the prevalence of BED might be higher in black and Latino populations 7,53–55 and among sexual minorities compared with the general population. 56–58 Furthermore, in the US and Australia, recent immigrants were at a lower risk59 and indigenous people60 at an equal or higher risk for BED than the general population. Stigma and stereotypes associated with gender, mental health, weight, age and various disadvantaged positions, such as disability and lack of resources, may decrease the visibility of BED61. For this reason, prevention, detection and management of BED is a medical question, but at the same time is also a question of social justice.

Mechanisms/pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of BED is still unclear. However, several studies have described biological and neural mechanisms that are associated with BED symptomatology, suggesting that alterations in biological processes and neural circuits are linked to binge eating episodes62.

Food intake regulation pathways

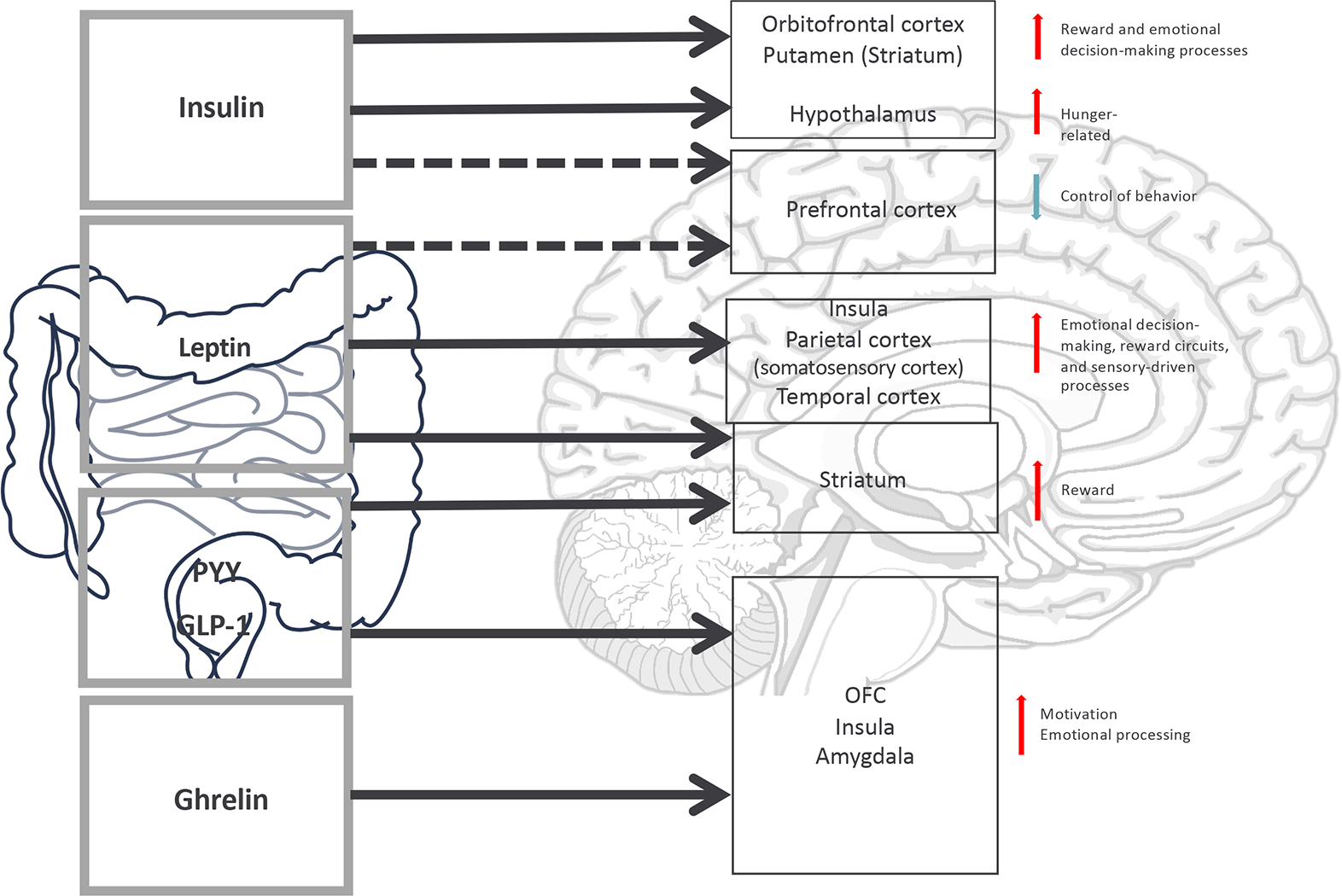

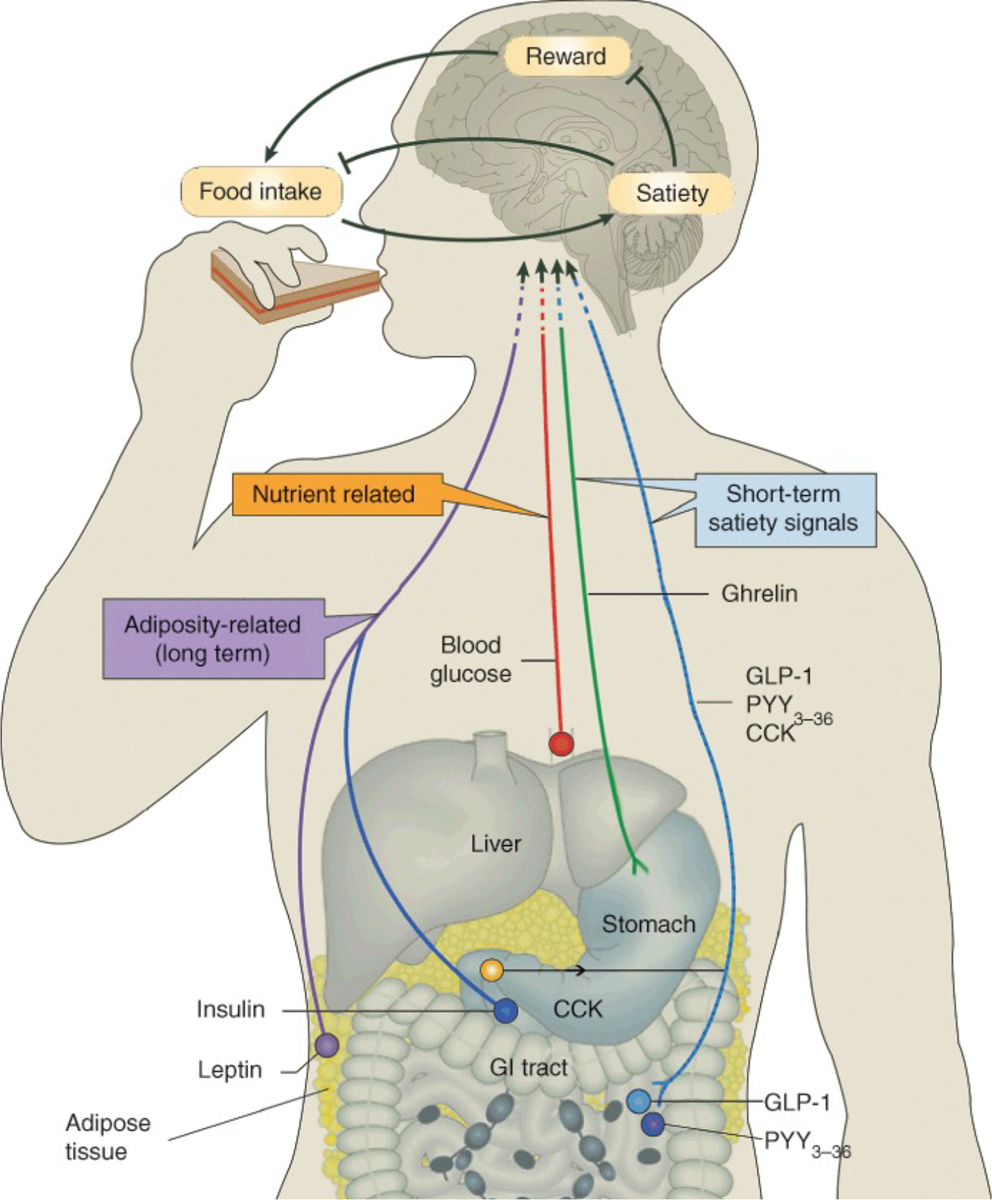

Pathways regulating food intake might be involved in overeating in BED (Figures 3 and 4). Hunger and satiety are regulated by the gastrointestinal, endocrine and nervous system through the integration of hormonal, neuronal, metabolic, behavioural and cognitive signals63. At the neuroendocrine level, a central structure for homoeostatic control is the hypothalamus64 (Figure 3). Ghrelin is secreted from the gastrointestinal tract in conditions of low nutrients, increasing motivation to seek food, whereas leptin acts in the central nervous system enhancing satiety signals64 (Figures 3 and 4). From hunger to satiety states, a cascade of endocrine satiety signals, in addition to ghrelin and leptin, support meal completion through the release of peptide hormones such as cholecystokinin (CCK), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY)65,66 (Figure 4). Moreover, other neurotransmitters such as dopamine, endogenous opioids and endocannabinoids modulate food intake by regulating rewarding aspects of foods, such as increasing orosensory or palatability of foods.

Figure 3: Schematic display of pathways of Gut-brain communication.

Eating behaviour is regulated by a complex interaction of the gastrointestinal, endocrine and central nervous system. Hormonal signalling from the gastrointestinal system to brain structures involved in homeostatic regulation (the hypothalamus), reward system functioning (the striatum) and cognitive control (the prefrontal cortex) influencing behavioural outcomes involved in the regulation of eating behaviour, such as processes of decision-making and emotion regulation, which are altered in individuals suffering from BED.

Figure 4: Food intake regulation.

Different peptide hormones, including ghrelin, leptin and insulin, promoting hunger and satiety signals are directly secreted from the gastrointestinal tract and predominantly communicate with brain regions involved in homeostatic regulation and reward system functioning. Research on alterations in gut-brain communication in binge eating disorder (BED) is in its infancy; however, putative dysregulated peptide hormone functioning has been hypothesized to be associated with altered hunger-satiety signalling in individuals with BED.

To date, few studies have evaluated the neuroendocrinological alterations in BED or other forms of overeating (such as grazing). However, in populations with loss of control eating, which is also a characteristic of BED, dysregulated peptide hormone functioning has been reported, including lower levels of fasting ghrelin, higher levels of leptin and dysregulated post-meal ghrelin concentrations 67. Mixed results were described regarding postprandrial alterations in CCK and peptide YY, with scarce studies describing augmented secretion after eating68,69. Such alterations could suggest a resistance to satiety signalling that could be a risk factor to trigger uncontrolled food intake in individuals with binge eating.

Underlying brain regions

The hypothalamus is critical in homeostasis via modulation of peripheral metabolic signals and motivational circuits, receiving afferent transmission from the nucleus accumbens (NAcc). Corticostriatal circuits regulate motivated behaviour in response to reward stimuli such as food or money. Alterations in corticostriatal circuits have been hypothesized to be due to excess consumption of high-calorie and palatable food70. The increased activity in striatal regions is associated with dopaminergic signalling that promotes craving for food, similar to craving in individuals with substance use disorders71. In patients with BED, neuroanatomical and functional alterations in corticostriatal circuits are the most consistent finding associated with the severity of BED symptomatology62. As corticostriatal circuits have a regulatory role on motivation and impulse control, it has been hypothesized that alterations in inhibitory control could be implicated in increased binge eating behavior70.

Individuals with BED also have distinctive neural activation patterns during tasks involving inhibitory control and reward processing compared with people with obesity and without a BED (Figure 5)72–74. Decreased inhibitory control is associated with diminished activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and the insula in individuals with BED compared with the general population75. During a functional MRI (fMRI) Stroop color-word interference task, individuals with BED had more diminished activity in the vmPFC, IFG and the insula than individuals with obesity or healthy controls75. The Stroop task presents in color words which are printed in either the incongruent color (e.g., the word “red” printed in green) or the congruent color. This produces cognitive interference effects, while high interference scores indicate high inhibitory control capacities. Structural and functional changes in brain regions involving frontal and striatal networks76, including those involved in emotional processing62, might be associated with uncontrolled eating in patients with BED. These corticostriatal alterations could be contributing to overeating, often acting as a way for short-term alleviation of negative emotions77. Putative relationships between emotion processing and binge eating which are mirrored in these neurobiological findings have been proposed by the emotion regulation model77 and the interpersonal model of BED78. The emotion regulation model outlines the role of negative affect as trigger for binge eating77, whereas the interpersonal model suggests that interpersonal problems might be a key source of negative affect in BED78.

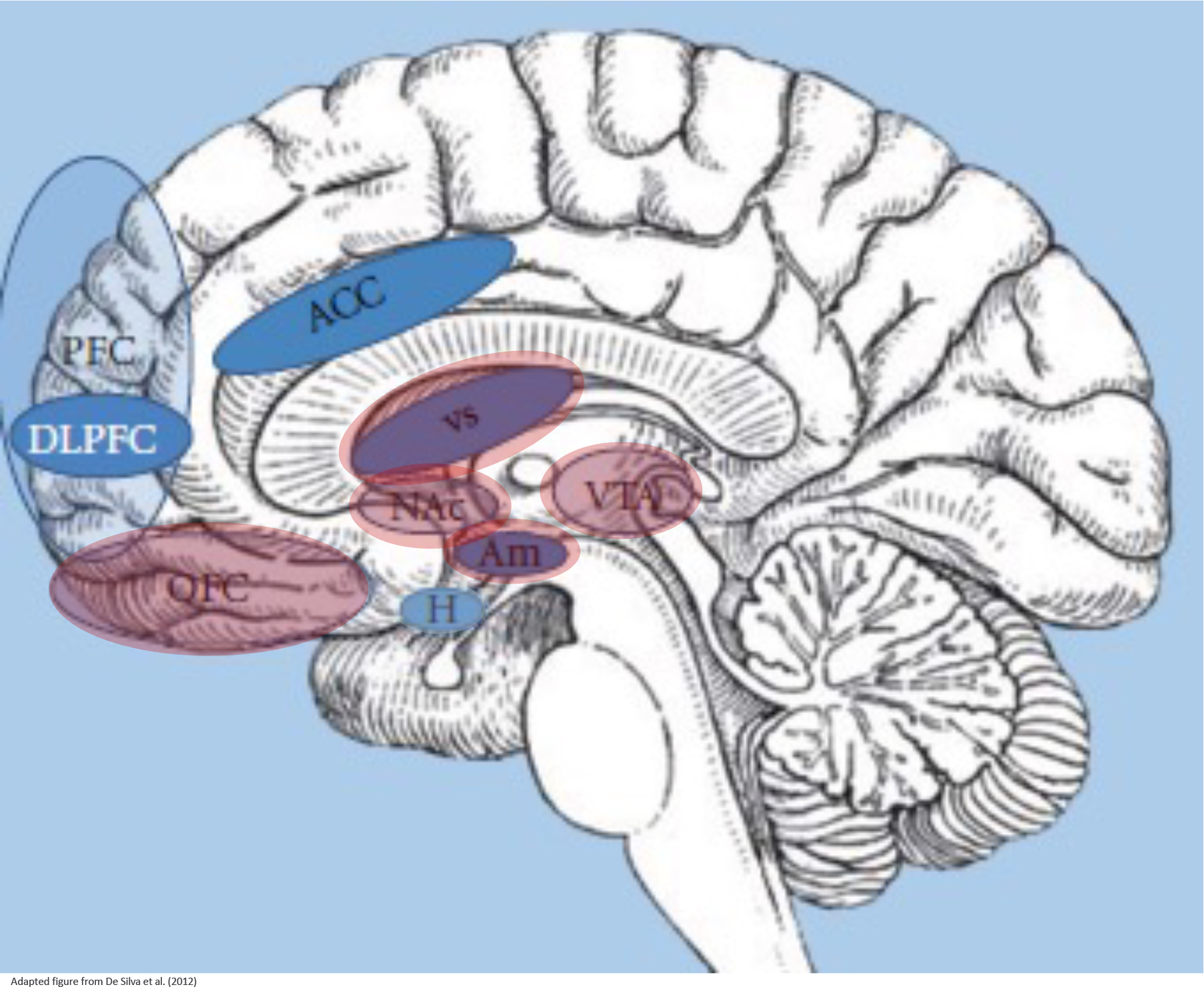

Figure 5: Brain circuits involved in the pathopsychology of BED.

Neuropsychological impairments of binge eating disorder (BED) have been explored in several brain imaging studies. The neurological basis of binge eating is composed of the hypothalamus (H) that regulates energy balance, such as food intake stimulated by gut hormones, the reward system that is representing motivational-affective functions (comprising the amygdala (Am), nucleus accumbens (Nac), ventral tegmental area (VTA), ventral striatum (VS) and orbitofrontal / ventromedial prefrontal cortex (OFC)), and cortical regions that are responsible for inhibitory control processes (comprising the prefrontal cortex (PFC), dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC); insula and inferior frontal gyrus not shown). These three systems interact while binge eating episodes and mirror main components of impulsivity, that is, reward sensitivity and inhibitory control.

Cognitive impairments in BED

Systematic reviews have demonstrated cognitive impairments in patients with BED when assessed with neuropsychological tasks79. In terms of the specific cognitive domains affected, individuals with BED had lower performance in decision-making, inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility as well as an attenuated food-related attentional bias, compared with healthy participants79–82. This lower performance has been also observed in individuals with substance use disorders, behavioural addictions or BN, suggesting a similar impairment in prefrontal executive function83,84. Cognitive impairment in patients with BED was associated with higher BMI85, although higher impulsivity was also reported for individuals with BED and normal-weight86. Moreover, cognitive impairment was associated with higher BED severity and greater general psychopathology (e.g., anxiety and depressive symptoms)85 and with poorer therapy outcomes87. In general terms, some of these cognitive impairments seem to be remediable88. However, some studies found a greater relevance of comorbid psychopathology in individuals with BED, namely depressive symptomatology, than cognitive dysfunction for therapy outcomes 89.

Decision-making is a complex cognitive process, involving conscious and habitual components, which ultimately results in the choice of an outcome over other alternatives. There are different decision-making circumstances, for instance, requiring choices under conditions of ambiguity. Patients with BED make riskier decisions in tasks involving decision-making under ambiguity compared with people with obesity without BED and normal-weight individuals90. Another facet of decision-making refers to delay discounting which comprises the ability to resist an immediate smaller reward in favour of a later larger incentive. Previous research has found that high delay discounting rates are associated with overeating and its reward value, namely in BED and obesity91–94, but also with specific personality traits including impulsivity94,95 and other psychiatric disorders91. Lack of delayed reward was associated with specific neural circuitry associated with activation of the limbic system and hypoactivation of inhibitory control, mediated by PFC, namely dmPFC96. Choosing immediate rewards over delayed rewards, based on emotional states, is more common in individuals with BED than in healthy controls or in those with disorders characterised by high levels of dietary restriction, such as AN94. Hypoactivation in the anterior insula may underlie increased delay discounting in individuals with BED96.

Genetics

BED aggregates in families 97,98, independent of obesity98. Twin and family studies of BED, using varyingly broad definitions of illness, have estimated its heritability as between 0.39 and 0.57 (Ref99–101). The study of molecular genetics of BED has lagged behind that of other eating disorders, particularly AN. Although the field of psychiatric genetics has progressed beyond candidate gene studies, here we acknowledge two reviews of historical interest. One study reviewed all published candidate gene studies and identified several polymorphisms with weak evidence of association in BED largely due to small sample size (many <100 cases or controls) and variable replication: 5-HTTLPR (5-HTT), Taq1A (ANKK1/DRD2), A118G (OPRM1), C957T (DRD2), rs2283265 (DRD2), Val158Met (COMT), rs6198 (GR), Val103Ile melanocortin receptor gene (MC4R), Ile251Leu (MC4R), rs6265 (BDNF), and Leu72Met (GHRL)102. MC4R is of particular interest owing to its known roles in energy homeostasis, food intake, satiety and body weight103. A systematic review and meta-analysis of six studies evaluated the association between coding variants in MC4R and BED in individuals with obesity 104. The analysis yielded a significant positive association between gain-of-function (GOF) variants in MC4R and BED (odds ratio [OR] = 3.05; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.82, 5.04; p = 1.7 × 10−5), with no significant association observed with loss-of-function (LOF) mutations (OR = 1.50; 95% CI: 0.73, 2.96; p = 0.25). Adjusting for study quality did not appreciably alter results. However, the included studies were judged to be of low quality and have serious risk of bias, limiting confidence and generalizability of the results.

No GWAS for BED have been carried out. One study used polygenic risk scoring (PRS) to explore differences between AN, BN and BED in the UK Biobank 105. In terms of psychiatric traits and disorders, BED was positively associated with PRS for schizophrenia, major depressive disorder and ADHD. Moreover, BED had positive associations with several anthropometric traits including waist circumference, hip circumference, overweight, obesity and childhood obesity —the opposite pattern as seen in AN. Furthermore, BED was negatively associated with the age at menarche PRS, meaning that increased genetic risk for BED was associated with increased genetic risk for earlier age at menarche. Notably, whereas the associations with PRS for psychiatric traits were similar across eating disorders (with the exception of ADHD only being associated with BED), the associations for anthropometric traits diverged considerably between AN and BED105. Associations between BED and PRS for overweight and obesity were replicated in a second sample. This study was the first to show similarities across eating disorders in genomic psychiatric liability, but divergent underlying biology in body mass regulation. Large GWAS are needed in order to confirm these observations.

Intestinal Microbiota

Emerging research suggests a role of the intestinal microbiota in both physical and psychological wellbeing106. The intestinal microbiome contributes to important functions such as digestion and absorption of calories from the gut107. Moreover, the gut microbiome is influenced by short-term and long-term dietary changes108,109 and has been associated with adiposity 110 and various mental disorders via the gut-brain axis111, including AN112. Several hypotheses have been forwarded regarding the potential role of the intestinal microbiota in BED113 including a dysbiosis or particular microbial composition that may influence host food choice114, the effect of short chain fatty acids (SFCA) produced by intestinal bacteria on dysregulated appetite115, and the effect of the gut-brain axis on mood with binge-eating serving as an emotion regulation strategy116–118.

One small empirical investigation has explored the composition of the gut microbiota from stool samples of 42 individuals with obesity and BED compared with 59 individuals with obesity and no BED using 16S rDNA sequencing119. In this study, individuals with BED had increased levels of Anaerostipes and decreased Akkermansia, Desulfovibrio, and Intestinimonas compared with people without BED. Although the meaning of these changes could be speculated, replication in larger well-characterized samples is recommended before definitive interpretations or causal conclusions can be drawn. Moreover, this study included only individuals with obesity, so conclusions regarding the the intestinal microbiota of individuals with BED who do not have overweight or obesity cannot be made. The study of the intestinal microbiota and intestinal microbiome in BED is in its infancy and no recommendations can be made regarding novel treatments that target the intestinal microbiota, until larger scale, standardized, and well-controlled studies are completed.

Diagnosis, screening and prevention

In western countries, health care professionals and the public are often not aware that BED is a discrete eating disorder 120. Related to this research-practice-gap, the dissemination of information on screening, prevention and management for BED and related clinical practice seems low established across the globe121,122.

Diagnostic criteria

As previously discussed, DSM-5 classifies BED as an eating disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of ingestion of an unusually large amount of food in a discrete period of time accompanied by feelings of loss of control and that are accompanied by at least three out of five common characteristics1 (Table 1). Studies that have attempted to quantify the amount ingested during a binge-eating episode report quantities between 3000–4500 kcal123. BED was included in the ICD-11 diagnostic system in 2018 (Box 1). ICD-11 classification of BED is broadly in accordance with DSM-5 (Box 1), except for the time criterion regarding frequency of binge-eating and size of binge-eating episode, which are more liberal in ICD2. As Figure 1 outlines, there has been some change especially regarding the time criterion during the process of recognizing BED as an official diagnosis, impacting prevalence estimates and transition between eating disorder diagnoses124. In the DSM-5, binge-eating frequency is used to determine the severity of BED1, as mild (one to three episodes per week), moderate (four to seven episodes per week), severe (eight to thirteen episodes per week) or extremely severe (fourteen or more episodes per week). The severity may be assessed higher if other symptoms and the degree of functional impairment are additionally considered, e.g. if an individual is significantly impaired in daily functioning by three episodes per week, this can be classified as moderate severity instead of a mild severity based on the mere binge-eating frequency. First studies conclude that this DSM-5 severity specifier is valid125, whereas others propose to specify BED severity according to overvaluation of shape and weight126.

Partial remission from BED is fulfilled if, after full criteria were previously met, binge-eating frequency is reduced to less than once per week for a sustained period of time1. DSM-5 does not specify the duration of this sustained period of time. If none of the DSM-5 criteria for BED which were previously met have been fulfilled for a sustained period of time, a person is in full remission according to DSM-51. ICD-11 does not determine severity or partial remission of BED2.

Health seeking behaviour

Regarding help-seeking behaviour, data from the US suggests that only about 50% of affected persons with BED are ever seeking help for their eating disorder, with lower help-seeking rates in men and in ethnic minority groups 26. The most frequent barriers to help-seeking behaviour experienced by affected patients are stigma and shame127. People affected by BED often seek for help with the aim to lose weight and are sometimes even not aware that they have an eating disorder122 as public awareness concerning BED is still low 120. Children and adolescents often do not meet full criteria for BED, but show “loss of control eating”, a concept in which the amount of food eaten is considered less relevant, as children often have restricted access to food or increased difficulties to quantify the amount eaten128.

Screening tools and assessment

As eating disorders, and BED in particular, are common disorders that are often unrecognized and undertreated129, effective screening tools and diagnostic strategies are essential. Owing to the considerable overlap between obesity and BED7 and a higher prevalence of BED in populations seeking out treatment for weight loss8,9, screening for BED is especially important in these risk groups.

The most commonly used screening tool for eating disorders in the general population is the 5-item SCOFF (Sick, Control, One, Fat and Food) questionnaire130. However, BED was not defined when the SCOFF was developed. Other specific self-report instruments and expert interviews have been developed that also include BED based on DSM-5 (Table 2). Structured clinical expert interviews are considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of BED12 (Table 2). For patients at high risk of BED, such as those with obesity assigned to receive surgery for weight loss, general recommendations have been published towards a combination of an established self-report instrument (such as EDE-Q) with an expert interview (EDE)131.

Table 2.

Frequently used instruments to assess binge eating pathology (adapted from Parker & Brennan, 2015 [1]).

| Instrument | Items | Description | Diagnostic instrument? |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Self-report instruments | |||

|

| |||

| BEDS-7 [2] | 7 | Screening tool for BED assessing DSM-5 criteria | no |

| BES [3] | 16 | Total score reflecting severity of binge eating behaviour | no |

| DEBQ [4] | 33 | 3 scales: Restrained eating, Emotional eating, External Eating | no |

| EDE-Q [5] | 28 | Adapted from the EDE, global score & 4 subscales: Restraint, Eating Concern, Shape Concern, Weight Concern | no |

| EDI-3 [6] | 91 | 12 scales: Drive for Thinness, Bulimia, Body Dissatisfaction, Low Self-Esteem, Personal Alienation, Interpersonal Insecurity, Interpersonal Alienation, Interoceptive Deficits, Emotional Dysregulation, Perfectionism, Asceticism, and Maturity Fears. | no |

| SDE [7] | Screening tool for EDs in primary care | no | |

| TFEQ [8] | 51 | 3 scales: Cognitive restraint, Disinhibition, Hunger | no |

| QEWP-5 [9] | 28 | Screening tool for BED assessing DSM-5 criteria | no |

|

| |||

| Expert Interviews | |||

|

| |||

| EDE [10] | 40 | current ED diagnoses, global score & 4 subscales: Restraint, Eating Concern, Shape Concern, Weight Concern | yes |

| SCID-5-RV [11] | Module I | Feeding and Eating Disorders diagnoses according to DSM-5 | yes |

BEDS-7: 7-Item Binge-Eating Disorder Screener; BES: Binge Eating Scale; DEBQ: Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire; ED: Eating Disorder; EDE: Eating Disorder Examination; EDE-Q: Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire, EDI Eating Disorder Inventory; QEWP and QEWP-R: Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns (Revised); SDE: Screen for Disordered Eating; SCID-5-RV: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders – Research Version; TFEQ: Three Factor Eating Questionnaire.

Generally, the use of single measures, for instance such as BMI or a screening score, should not be used to decide whether a person should be offered treatment for BED 12. Across health care settings, clinicians should routinely conduct confidential psychosocial assessments that include questions regarding eating behaviour, body image and mood in patients at risk of an eating disorder132. In addition, they should monitor patients’ weight and height in terms of BMI including the respective percentiles changes and growth curves for children and adolescents to identify the favorable window for early intervention. In addition, diagnostic assessment of BED should also evaluate weight history including weight cycling and extreme body weight, eating patterns including irregular, restrictive and selective eating as well as overeating and feelings of loss of control, compensatory and exercise behaviours as well as body image including dissatisfaction and preoccupation with weight and shape132.

Similar to other eating disorders and obesity, BED is associated with considerable stigma61 and shame133. Both can result in fear and reticence towards help seeking and disclosing eating disorder symptoms61 and experienced stigma or discrimination can contribute to distress and depression as well as maintaining maladaptive eating behaviour61. A nonjudgmental and motivational stance has proven successful in establishing a working alliance with patients with eating and weight disorders132.

Medical morbidity and complications in BED

Owing to the high prevalence of BED, especially in those with marked obesity, patients should also undergo evaluation for metabolic syndrome134,14. Based on the harmonized definitions and clinical criteria of metabolic syndrome, waist circumference, triglyceride levels, low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and fasting blood glucose levels should be recorded in addition to anthropometric parameters (weight and height), weight history and blood pressure14. In particular, as diabetes is a major concern for patients with BED, a stepwise evaluation of blood glucose levels is encouraged.

Differential diagnosis

A considerable subgroup of patients with BED have other patterns of maladaptive eating and overeating, such as grazing (the uncontrolled intake of smaller food amounts over prolonged time). BED should be differentiated from grazing, which is highly prevalent in patients with BED but is not a diagnostic criterion for BED, and is also common in patients with obesity who do not have BED and patients with other eating disorders135. In addition to the differential diagnosis from other eating disorders (Table 1), BED must be differentiated from other mental disorders that can be associated with an increase in food intake, such as primary depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Moreover, BED should also be differentiated from personality disorders, in particular borderline personality disorder, which can be associated with impulsive behaviour, including binge-eating. Differential diagnosis should also exclude alcohol or cannabis abuse or the use of other appetite-enhancing substances. In unclear cases, one must also consider endocrine disorders (Cushing’s syndrome, hypothyroidism and insulinomas), neurological disorders (neuronal lesions to the medial hypothalamus and craniopharyngeoma) and rare genetic syndromes (such as Prader Willi syndrome) as somatic differential diagnoses.

Natural course of BED

The evidence on the natural course of BED is heterogeneous and is mainly based on data from high-income countries. However, most long-term studies suggest that the natural course of BED is often long-standing, particularly in adults19, with an average duration of 14–16 years 7,136. In addition, there is a high rate of transmission from a BED diagnosis to other eating disorders, in particular BN7 and vice versa.

Prevention

Prevention efforts towards the establishment or maintenance of healthy eating behaviour and healthy body weight can be divided into measures and programs involving educational and behavioural interventions targeting the individual, and larger-scale interventions targeting structural and situational factors at the societal level.

Large-scale interventions are especially relevant in terms of the food environment which has been termed as being ‘toxic’137 in most parts of the western world, that is, an environment that encourages the consumption of high-fat, high-sugar food137. As such, there is considerable overlap between approaches to prevent obesity and eating disorders, including BED. In line with this, recent approaches have advocated universal prevention of eating and weight disorders138. Multi-component strategies integrating regulation of eating behavior and body weight will likely be the most effective 14. However, the effects of larger-scale efforts that incorporate policy-changes are often hard to conduct, making it difficult to identify which components are effective for prevention139. Individuals at risk of binge eating might profit from prevention efforts on a societal level, which predominantly address factors contributing to food choices and opportunities to be physically active in an individual’s everyday life140. Potential influencing factors include the quality of food and access to unhealthy food at workplace or school cafeterias, availability of supermarkets, convenience stores and fast-food restaurants in the neighbourhood, industrial food marketing strategies and governmental tax policy141. For example, one meta-analysis concludes that specific school policies concerning food and beverage availability can improve dietary behaviors142.

Prevention strategies targeting the individual incorporate interventions derived from individual risk factor research. As previously mentioned, the first occurrence of BED is typically preceded by a series of stressful life events that may represent triggering factors for instance comments about shape, weight or eating, or physical abuse143. However, similar life events were also found in women with different mental disorders 143, underlining the challenges of targeted disorder-specific prevention efforts. Typical prospective antecedents of a BED diagnosis in girls comprised binge-eating, compensatory behaviours, weight/shape overvaluation, fear of weight gain and feeling fat144; these prodromal risk factors predicted onset of BED with an accuracy between 67 and 83%144, representing promising starting points for prevention efforts. Moreover, negative mood is also an antecedent factor for the immediate triggering of binge-eating in BED77, representing a highly relevant mechanism for both prevention and management approaches. A meta-analysis found that structured prevention programs using different approaches offered at universities to high-risk students are effective in reducing the onset of sub-threshold or threshold eating disorders, predominantly by influencing dieting behaviour, drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction145. Another meta-analysis found that structured programs increasing media literacy are effective in reducing eating disorder risk in adolescents 146. In terms of more targeted prevention efforts, cognitive dissonance approaches were most effective in reducing eating disorder risk factors146 and future onset of eating disorders147. The main idea of this approach is to challenge the thin ideal via inducing dissonance between attitudes and behaviors147. Hence, this targeted prevention approach has strongest effects in reduction of thin-ideal internalization146, which is however not the only risk factor or prodromal symptom for an emerging BED144, and as most trials assess eating disorder symptoms as outcomes146, it remains unclear if prevention efforts eventually translate into reduced diagnoses and if they are more useful to reduce one diagnosis over the other.

Management

Goals

Goals of treatment for BED include reduction or cessation of binge eating and associated psychopathology, improvements in mood and other psychiatric symptoms, improvement in metabolic indicators (such as HBA1c) and improvement in quality of life. As outlined above, weight-related treatment targets such as stabilisation or reduction in weight are controversial for BED.

Evidence-based treatments for BED, recommended by international guidelines12,148,149 include psychological therapies (particularly cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT)) and pharmacotherapy with second generation antidepressants, anti-convulsants (topiramate and zonisamide), CNS stimulants (lisdexamfetamine) and anti-obesity medications (orlistat). A network meta-analysis assessed the comparative effectiveness of BED treatments, with a total of 28 treatment comparisons and only one pharmacological comparison (2nd generation antidepressants versus lisdexamfetamine)150.. This meta-analysis found three contrasting outcomes: higher abstinence rates were found in people treated with lisdexamfetamine compared to second generation antidepressants, lower binge frequency was found in those treated with therapist-led CBT compared to behavioural weight loss, but lower weight was found in those treated with behavioural weight loss. There were few other advantages found for any treatment in comparative trials.150.

Psychological treatments

International guidelines recommend evidence-based psychological therapy as first-line care for BED and for a considerable subgroup is sufficient treatment to achieve remission from binge-eating12,148,149. This therapy is usually carried out in an outpatient setting but can be part of partial or full hospital programs with outpatient follow-up151. Three main therapies for BED have evidence of efficacy from randomised controlled trials: CBT152, interpersonal psychotherapy153 (IPT) and dialectical behaviour therapy154 (DBT) (Table 3). All three therapies are manualized 152–154 and have been tested in group as well as individual formats. CBT has the most extensive evidence and adaptations to scalable forms such as guided and pure self-help155, both of which have good outcomes for BED. DBT also has a guided self-help form156.

Table 3.

Manualised evidence-based psychological therapies for Binge Eating Disorder (BED)

| Therapy | Theoretical model | Core elements |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) Full, pure and guided self-help forms and CBT–enhanced (CBT-E) |

CBT formulation - Core beliefs (overvaluation of shape and weight) initiate weight control behaviours that with negative mood states & life events initiate and maintain binge eating without compensatory behaviours. | Personalised psychoeducation Behaviour monitoring & experiments Cognitive restructuring & chain analyses Enhanced with modules for mood intolerance, clinical perfectionism, interpersonal deficits, low self-esteem |

| Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) | There is a bidirectional relationship between BED symptoms and interpersonal function mediated by self-esteem & negative affect. Focus on four problem areas (grief, role transitions, role disputes, interpersonal deficits). |

Exploration of interpersonal function/current relationships (inventory) & for mulation Affect clarification & communication analysis A strong therapeutic relationship |

| Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) and and guided self-help DBT | Understanding the dialectic of opposing views of ED behaviours and their use in distress reduction. | ‘Meaning making’ of symptoms as acceptance and change; Validation & Training in: mindfulness; distress tolerance; emotion regulation; & interpersonal effectiveness. |

A network meta-analysis of 81 studies comprising 7,515 participants identified 43 psychological therapy conditions (of which 36 were CBT) and 14 structured self-help approaches (of which 7 were guided and 5 were pure self-help CBT) across the included studies157. Most trials encompassed a wait-list control arm, female (90% across the studies) participants, with study mean ages in the mid-40 years, and mean BMI of above 35 kg/m2. The mean duration of BED was 17.9 years and mean number of therapy sessions was 16.5 weeks. This meta-analysis157 demonstrated moderate effect sizes at end of therapy for reduction of binge-eating (that is, fewer binge eating episodes), other eating disorder psychopathology and improved mood for full and guided therapies, and significantly greater improvements compared with wait list, but no improvement in BMI. Similar findings were reported for self-help interventions157. Improvements were generally maintained at 6 and 12 month follow-ups. Unusually, a small but significant increase in lost-to-follow-up assessments was found in the active psychotherapy condition compared with wait list controls. Of note, quality grades were low to very low, mostly due to limitations in study design or execution (risk of bias), inconsistency (such as high heterogeneity), lack of direct evidence and imprecision (low confidence).

IPT has proven effective for the treatment of BED in RCTs compared with behavioural weight loss treatment, guided self-help158 or CBT159. One meta-analysis on the efficacy on DBT in BED summarizes that DBT has greater efficacy than the control group in improving emotion dysregulation and eating disorder psychopathology160.

Few head to head comparisons of psychological therapies for BED have been reported157. In three trials, CBT reduced binge-eating days more than humanistic therapy (an active supportive therapy aiming to improve self regard), IPT or focal psychodynamic therapy but no other significant differences were observed157. In one RCT, CBT resulted in greater improvements in binge-eating and other eating disorder symptoms than DBT161. Psychological therapy outcomes did not differ from outcomes with combination psychological and pharmacological therapy, but attrition was lower with psychological therapy alone157.

Overall, although the majority of evidence for psychological therapies for BED is for CBT, the risk of bias is high across all trials of psychological therapies owing to lack of blinding and the use of inactive wait list control groups. Psychological treatments for BED can be combined with treatments for comorbid conditions such as major depression. Moreover, management of some comorbidities may be integrated into the BED therapy. In particular, mood intolerance and emotion regulation skills are an integral part of enhanced CBT (CBT-E)152 and DBT154. Similarly, interpersonal deficits are integral to IPT153 and to a lesser degree in DBT154 and CBT-E152.

Regarding moderators and predictors of treatment outcome in BED, a specific synthesis of available studies is required and findings have been hard to replicate; however, features associated with a better outcome are an early response to therapy (reduction of binge-eating within the first weeks), an absence of substance use disorder, lower age, lower BMI and good premorbid interpersonal functioning157,162. Moreover, CBT trials identified low weight concern as a predictor for remission163 and a history of trauma as negative predictor of treatment success164. Overall, around half of people with BED achieve abstinence from binge-eating, which is maintained at 12-month follow-up; however, longer-term outcomes are less clear165.

Pharmacological therapies

Box 2 provides an overview on drugs that have been tested for the treatment for BED in at least one RCT. Meta-analyses157,166 have found that a range of pharmacological treatments have significant short-term effects on reducing or stopping binge-eating episodes compared with placebo in patients with BED, mostly consisting of second generation antidepressants or the CNS stimulant lisdexamfetamine (LDX); however, pharmacological treatments have inconsistent effects on eating disorder psychopathology and mood. Most studies lack longer-term follow-up. Available data on second generation antidepressants suggest that reductions in binge symptoms are no longer significant at 3–6 months follow-up165. Another systematic review focused on combinations of psychological or weight loss therapies with medication, with the idea that these combinations might be more ‘potent’ or helpful for patients with comorbidities compared with monotherapy 167. However, pharmacotherapy significantly enhanced both binge-eating and weight outcomes only in two of 12 included trials (both with antiseizure medications) and modestly enhanced weight loss, but not binge-eating outcomes in two (both with the weight-loss medication orlistat) trials 167.

Box 2: Medications that have been tested in at least one randomised controlled clinical trial in BED157,245,246.

Antidepressants

Bupropion

Citalopram

Duloxetine

Escitalopram

Fluoxetine

Fluvoxamine

Sertraline

Vortioxetine

CNS stimulants

Armodafinil

Atomoxetine

Lisdexamfetamine

Methylphenydate

Anticonvulsants

Lamotrigene

Topiramate

Zonisamide

Anti-obesity medications

Other medications

Chromium Picolinate

Acamprosate

ALKS-33

Baclofen

Dasotraline a

GSK 1521498

Combination treatments

Phentermine plus topiramate

Phentermine plus fenfluramine a

Phentermine plus fluoxetine

Naltrexone plus bupropion

aMedication has been discontinued.

Lisdexamfetamine (a prodrug of d-amfetamine) is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe BED in adults168. In short-term trials, lisdexamfetamine significantly reduces binge-days/week, improves associated psychopathology and reduces body weight by ~5–6%, with beneficial effects observed one week after commencing treatment. In an open label 52-week extension of the short term trials, 344 of 604 participants (57%) took lisdexamfetamine for the full 12 months extension169. Weight loss at 12 months in those who completed treatment was ~ 7.7 kgs. Common adverse effects term included dry mouth, headaches and insomnia. Overall, the authors concluded that the safety and tolerability profile of lisdexamfetamine in adults with BED was broadly consistent with that in ADHD. One other study started with a 12-week, open-label phase during which the dose of lisdexamfetamine was optimised170. Of the 418 participants enrolled in the open-label phase of the study, 275 were deemed to be responders and were randomised to receive either lisdexamfetamine or placebo for a further 26 weeks. The proportions of participants meeting relapse criteria during the study period were 3.7% (5 of 136) for lisdexamfetamine and 32.1% (42 of 131) for placebo. Patients randomised to lisdexamfetamine had a significantly longer time-to-relapse (primary outcome) than those on placebo. The treatment-emergent adverse events observed were generally consistent with the known profile of lisdexamfetamine 170.

Two placebo controlled double-blind trials have evaluated the efficacy and safety of dasotraline (a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor) in adults with BED171,172. One trial172 used once-daily, flexible doses (4, 6 or 8 mg/d) of dasotraline or placebo over 12 weeks in 315 adults, and found a significantly greater reduction in binge-eating days in the dasotraline group compared with placebo. Discontinuation due to adverse events occurred in 11.3% of patients on dasotraline compared with 2.5% on placebo. The second trial171 examined two fixed doses (4 and 6 mgs of dasotraline) compared with placebo in 491 adults with BED over 12 weeks. At week 12, treatment with dasotraline was associated with significant improvement in number of binge-eating days per week with 6 mg/d dasotraline versus placebo but not with the 4 mg/d dose of dasotraline. In both studies the most common adverse events on dasotraline were insomnia, dry mouth, headache, decreased appetite, nausea and anxiety. Changes in blood pressure and pulse were minimal. Both studies assessed dasotraline treatment as safe and effective; however, the company has withdrawn the drug development application and will not pursue it further for the treatment of BED.

Managing high body weight

As many people with BED have a high BMI with associated physical and mental health morbidity37 numerous treatment trials have reported weight loss outcomes, and weight loss treatments have been trialled extensively. Most trials have reported short term greater weight loss with behavioural weight loss treatment (BWL) than with psychological therapies such as CBT, but there is less improvement in binge-eating frequency with BWL 10,157. BWL is a psychobehavioural therapy that was developed for weight loss and has some similarities to CBT (such as monitoring eating behaviour), but BWL is not derived from psychological theory and is delivered by health professionals without formal psychological training.

The efficacy of psychological treatments in inducing weight loss in people with BED are inconsistent173. In one longer term trial, psychological therapies had similar weight loss and better eating disorder outcomes at 2 years follow-up158 but this was not demonstrated in another trial with a 6-year follow-up174. ‘Weight-neutral’ approaches have also been advocated in people with eating disorders for whom dietary restriction may risk relapse of binge-eating and other symptoms, and some evidence supports their positive psychological and physical health (including increasing activity levels) outcomes generally175. Notwithstanding the need for caution, people with BED with medical compromise and a high BMI may benefit from approaches that integrate weight loss management with eating disorder treatment. A small number of trials have examined BWL and CBT treatments, for example, the SMART stepped care trial (that started with BWL, then moved to CBT with additional randomisation to weight-loss medication or placebo)176 and one RCT of integrated psychological therapy of CBT-E and BWL for people with disorders of recurrent binge-eating (BED, BN and OSFED)177. However, there was no evidence for a superiority of a certain intervention sequence or an integrated approach for weight-loss and most BED outcomes176,177.

By contrast, there are demonstrable benefits supporting the need for psychological therapy for people receiving weight loss treatment such as surgery 178. Pre-operative BED does not contraindicate obesity surgery and, according to data from a meta-analysis, does not seem to influence weight loss after surgery179; however, the number of high-quality studies in this field is limited. Binge eating can still occur after surgery178 (with intake of high caloric and easily digestible food despite the highly restricted stomach capacities) and binge eating pathology can return to pre-surgery severity in the long-term180. The post-operative prevalence rate of BED has been quantified as 4% across studies181.

As discussed above, psychological therapies for BED are effective in reducing binge eating, whereas weight loss is not an aim of psychological therapies and is not necessarily expected. However, some studies revealed wide inter-individual variability in terms of weight loss or gain with BED treatment, and people who achieve binge eating abstinence with the help of psychosocial therapies can lose weight 182,183. However, deficits in metabolism due to chronic dieting and restriction can contribute to maintenance of higher weight status.

Emerging treatments

A broad range of novel approaches to treating BED are being tested, some of which are stand-alone interventions whereas others augmenting established treatments. Neurobiologically-informed multi-component psychological therapies, targeting impulsivity, inhibitory control and/or emotion regulation have been trialled for BED with some success184,185; however whether these therapies are superior to more conventional cognitive behavioural treatments for BED is not clear.

Neurocognitive approaches, including face-to-face cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) and various computerised trainings, focusing on processes related to inhibition, general and food-related impulsivity and associated biases, have been used to reduce overeating and weight in BED and/or obesity80,186,187. CRT is a psychotherapy approach that aims to improve neurocognitive functioning. One trial comparing CRT with no treatment in 80 patients with obesity (of whom 70% reported binge eating) showed significant improvements in cognitive flexibility, weight and binge-eating in the CRT group188. Feasibility trials of different cognitive trainings, including attention, approach bias and inhibitory control training, have been conducted with somewhat mixed results, given different methodologies, comparison groups and training ‘dose’ 189–191. Learning models suggest that exposure-based therapy may be effective in reducing food cue reactivity, overeating and body dissatisfaction in BED. In line with this thinking, exposure interventions to illness-related stimuli (food and body) have been developed and tested in small trials192,193. Increasingly, virtual reality (VR) enhanced approaches have been used to tackle food-craving or food or body-related fears in bulimic EDs194 with some success in reducing binge-eating. VR-approaches rely on the creation and therapeutic use of computer-generated virtual environment which exposes the person to stimuli that are closely related to disorder symptoms and foster the opportunity for the person to develop and practice skills that reduce binge eating. An adjunctive VR-CBT module added to a behavioural inpatient weight loss approach and focused on rescripting negative body memories was successful in supporting or maintaining longer term weight loss195. In addition, refinements of psychological treatments have been developed and tested, for instance, integrated cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) which has a strong focus on affect intensity and emotion regulation and might help patients with increased difficulties in these areas196. For individuals with partners, a cognitive-behavioural couple intervention (Uniting Couples in the Treatment of Eating Disorders-UNITE) has shown preliminary evidence of efficacy for the treatment of BED197.

Medications used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus, namely glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, such as liraglutide and dulaglutide, have both a peripheral and central effect on appetite control. These medications have shown promise in reducing binge-eating and body weight in patients with obesity198 and in those with BED and diabetes mellitus 199.

Improved understanding of the neurocircuitry involved in EDs has allowed the exploration of a range of non-invasive neuromodulation (NIBS) treatments, such as repetitive transcranial current stimulation (rTMS), transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and neurofeedback200,201. A handful of proof-of-concept or feasibility trials have used NIBS in populations with BED, a mixture of BED and BN or obesity per se 202,166. The potential of these interventions for the treatment of BED is uncertain. Combinations of neuromodulation interventions with different cognitive trainings are also being piloted in BED203,204; whether combining these therapies is associated with synergistic effects on efficacy is unknown.

Quality of life

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) can be measured using the WHO Brief QOL Assessment Scale (WHOQOL-BREF)205 and well-being can be measured using the WHO-5 Well-Being Index206. General measures of HRQOL (such as the WHOQOL-BREF and the Medical Outcomes Short Form (SF) health survey 12 (SF-12))207, inform the comparative level of health burden and cost utility estimates. The most frequently used instrument to examine HRQOL in patients with eating disorders is the SF-12 or its parent version the SF-36 8. Eating disorder illness specific instruments, such as the Clinical Impairment Assessment scale, are also widely used for this purpose208. Moreover, a measure of the family burden of caring for someone with an eating disorder has been developed, the Eating Disorders Symptom Impact Scale (EDSIS) 209.

HRQOL is impaired in people with BED compared with people without an eating disorder in representative community populations8, to a similar extent as in people with other eating disorders. As previously mentioned, BED is associated with both physical and mental health morbidities such as high weight and depression8 (Box 3). These observations apply both when the stricter DSM-5 definition of a binge episode as objectively large or the broader ICD-11 definitions are applied210.

Box 3: Patient’s perspective.

Could you describe a typical binge eating episode?

“So, for me, my binges are triggered by negative emotions, so when I feel bad or when I am lonely. (…) And then all of a sudden, the entire pastry was gone and I was totally - I hadn’t even noticed, because I lost track of it. Immediately afterwards, I usually felt better (…). But then as time went by, I felt much worse than before, because first you are physically full from overeating, and then also because you have, uhm, a guilty conscience (…).”

How has BED affected your life overall?

“It was especially like, you were constantly preoccupied with food, and were also always checking “do I have anything to eat?”. (…) But then of course, there was also the constantly guilty conscience, uhm, because you would always be eating and then accordingly having these [guilty] thoughts, and that was a pretty big burden in [my] day-to-day life.”

What caused you the most significant distress?

“The guilty conscience, the negative thoughts. Because you then always completely question your own identity, and you can’t look at this in isolation anymore, i.e. only in relation to eating. (…)

[My weight] was a huge burden [as well]. Especially because over time it was impacting [my] physical health as well, through hip problems and shortness of breath, so that you could notice that you couldn’t keep up with friends during walks or sport. Which is all very stressful.”

The effects of BED translate into personal and public health economic costs. A revision of the Global Burden on Disease estimates to include BED found that of an estimated 41.9 million global eating disorders cases in 2019, 17.3 million were BED, and accounted for one fifth of the total Disability Life Adjusted years (DALYs)15 due to eating disorders. Further research has supported the effect of the presence of recurrent binge-eating, and the DSM-5 diagnostic specifier of distress related to binge-eating, on health state utility values (HSUVs; the ‘Q’ in Quality ALYs)211. Population estimates of fiscal costs for BED are high. In one Australian study212, the total economic cost of an eating disorder was AUS$84 billion from years of life lost due to disability and death, and annual lost earnings were $1.646 billion. These lost earnings peaked for both males and females aged 35 to 44 years, a period of high personal productivity. In this study, costs of BED were similar to those of other eating disorders, and binge-eating in itself accounted for 65% of the yearly financial cost of eating disorders.

Moreover, health care use and costs are increased for people with BED. In a Swedish case register study213, hospital and other health care costs were present for some years prior to and after their peak at the time of diagnosis and were also incurred for the treatment of comorbid disorders. Under-treated or undetected BED is a major problem214 that can increase personal, fiscal and health care burden. People with BED are likely to have additional effects from weight stigma, which diverts their treatment seeking to weight loss clinics and adds to treatment delays214,215. This adds to physical and psychiatric morbidity which has been found to be high in the general population and to comprise a large number of diverse disorders 37.

Outlook

Conceptualization

Since its inclusion in DSM-5 in 20131, BED has received increasing recognition and the volume of research into this eating disorder is growing. The diagnostic criteria for BED have evolved over decades (Figure 1), and the relative novelty of this eating disorder diagnosis is also reflected in an ongoing nosological debate on how to best conceptualize BED. For instance, the concept of food addiction216 has been introduced, a phenotype that largely overlaps with both substance-use disorder and BED, assuming that especially ultraprocessed food can be ‘addictive’ and trigger addictive-like eating patterns216 including loss of control eating as in BED. Alternatively, impulsive eating patterns have been conceptualized as a behavioural addiction217. These different conceptualizations potentially have significant consequences for prevention and treatment approaches. At the same time, there is little consensus regarding the introduction of such novel ‘neighbourhood’ diagnoses.

Epidemiology and burden of disease

Despite increased recognition, awareness and high prevalence estimates of BED, research into many facets of this disorder lags behind the other two primary eating disorders diagnoses, AN and BN. These gaps in research cover important questions regarding epidemiology and quality of life, such as findings on the mortality of people with BED, which are more mixed and lower than for AN or BN218, in addition to wider family and carer burden 218. As mentioned earlier, the prevalence of BED in many regions is unknown 15. Lacking data and awareness regarding epidemiology and burden of disease of BED is problematic for many reasons219, not least, because eating disorder research in general is grossly underfunded, partly due to the neglect of the effect of eating disorders on the individual and society15,219,220.

Pathomechanisms

Genetics and epigenetics are other emerging fields in the study of BED, with currently very limited specific evidence. No genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of BED have been completed, although studies are in progress221,222. However, one strength of the BED field are advances in delineating the neurobiological mechanisms of BED which, together with more clinical findings39, are supporting the view that individuals with BED represent a distinct phenotype within the obesity spectrum characterized by increased difficulties associated with reward processing, inhibitory control80,82 and emotion regulation capacities77. This research has led to translational research efforts, probing novel approaches which are informed by these mechanisms185,187,189,200,201 and which could be important components in the management of BED. As in other field of mental health research, emerging novel methods from machine learning might contribute to a better understanding of disease mechanisms by integration of large-scale data as well as to a better prediction of the course and outcomes of BED223.

Treatment and prevention

Improving the outcome of BED treatment should be a main priority in coming years as first-line therapy achieves abstinence rates of only 50%165. Within this endeavour, the common overlap between obesity and BED poses a major challenge; both conditions have shared risk factors, comorbidities and pathogenesis, yet, the optimal preventive and treatment strategies remains unclear, such as whether targeting weight loss and eating behaviour simultaneously, choosing one of these treatment goals and related interventions first, or pursuing a “weight neutral” approach is optimal175,176,224. Moreover, it remains widely unclear if successful BED and obesity prevention strategies are largely overlapping or how BED prevention would differ from obesity prevention, how we can guard against obesity prevention efforts promoting more binge-eating, and, regarding a more eating disorder focused perspective, how specific prevention approachs for BED would look like along the spectrum of different eating disorders.

An important next step, given that there is a considerable progress in the development of psychological treatments for BED, is to ensure that evidence-based treatments are translated into clinical practice. Scalable solutions for the training of clinicians to deliver evidence-based psychotherapy have been proposed and investigated225. Another avenue for making evidence-based care more accessible for patients is the implementation of digital intervention and delivery technologies and strategies, also in terms of stepped-care-approaches226.

Other issues

Closely related to those important clinical questions is the notion that obesity is a heterogeneous condition14 with different phenotypes characterized by specific underlying vulnerability factors. Patients with BED represent one such phenotype. To improve treatment outcomes for these different phenotypes, implementing assessment of eating behaviour, including binge-eating, into research studies investigating individuals on the overweight spectrum is important. A better characterization of study samples in terms of eating behaviour and eating disorders will help the field to learn more about individual vulnerability factors, develop more targeted interventions and, ultimately, help advance etiological research on BED. This is vital as there is no consensus model integrating state-of-the-art evidence on different factors contributing to the etiology of this multi-factorial eating disorder, although approaches looking at specific topics such as underlying neurobiological mechanisms have been proposed81. Another priority for the coming years is to work toward and debate an integrated etiological model of BED to encourage more theory-driven research in the field. Ideally, such a model would go beyond the individual and also acknowledge the important influence of environmental factors on the regulation of eating behaviour and body weight141.

From a global health perspective, addressing the obesity epidemic, as it has been termed by the WHO11, constitutes one of the top long-term priorities for societies and health care systems worldwide. This aim is unlikely to be successful without a comprehensive consideration of eating disorders, especially BED. In particular, the severe effect of BED on individuals and society 15 (Box 3), elevates the reduction of this burden to an additional long-term health priority.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements