Abstract

Gas-phase ion/ion reactions can be used to alter analyte ion-types for subsequent dissociation both quickly and efficiently without the need for altering analyte ionization conditions. This capability can be particularly useful when the ion-type that is most efficiently generated by the ionization method at hand does not provide the structural information of interest using available dissociation methods. This situation often arises in the analysis of lipids, which constitute a diverse array of chemical species with many possibilities for isomers. Gas-phase ion/ion reactions have been demonstrated to be capable of enhancing the ability of tandem mass spectrometry to characterize the structures of various lipid classes. This review summarizes progress to date in the application of gas-phase ion/ion reactions to lipid structural characterization.

1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction to analytical challenges in lipid analysis

The lipidome is defined as the lipid complement of a cell or organism. A quantitative study of cellular membrane lipids via nano-electrospray ionization (nESI) tandem mass spectrometry reported in 1997 by Brügger et al. [1] ushered in the investigation of diverse lipid species in biological systems. An early discussion of the analysis of the lipidome, referred to as lipidomics, was provided in 2001 by Moriyama and co-workers [2], followed by an outline of the scope of lipidomics by Han and Gross in 2003 [3]. In the ensuing two decades, lipidomics has become integral to the study of cellular function and structure [4]. Lipids can be classified into eight major categories: fatty acids (FAs), glycerolipids (GLs), glycerophospholipids (GPLs), sphingolipids (SPLs), sterol lipids (STs), prenol lipids (PRs), saccharolipids (SLs), and polyketides (PKs), with subclasses associated with each category [5,6,7]. The structural diversity across all lipid classes results in more than 150,000 unique lipid species, making the specific identification of individual lipids particularly challenging. Nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly clear that detailed identification of individual lipids is important in understanding the biology of the cell. For example, the eukaryotic cellular membrane is well-known to be comprised of lipid bilayers, which are mainly composed of phospholipids (PLs) [8]. However, the detailed lipid composition of the cellular membrane can differ by cell-type or even micro-regions on an individual cell to mediate lipid-protein interactions [9, 10]. The general classification of “phospholipid” is too broad for describing the specific lipid function, because each of the GPLs as well as sphingomyelin, which is an SPL, plays a different role in cellular membranes. GPLs share a similar glycerol backbone linked to two fatty acyl chains at the first two positions and a phosphate group at the third position. Each GPL subclass, such as phosphatidic acids (PA), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylinositol (PI), and phosphatidylserine (PS), has a unique head group bound to the phosphate. Therefore, structural differences among GPLs can rise not only from the identities of the head groups, but also from the relative positions of fatty acyl chains, if different, along the glycerol backbone, lengths of the fatty acyl chains, sites and extents of unsaturation within the fatty acyl chains, and possible stereochemical differences (e.g., cis vs. trans double bonds).

Mass spectrometry has been the most commonly used tool for lipidomics analysis, especially for identifying trace lipid components in biosamples [11,12]. Many recent reviews summarize mass spectrometry approaches for structural elucidation of lipid species with different foci, such as general lipidomics [13,14], ion activation [15], ion-mobility mass spectrometry [16], condensed phase derivatization [17, 18], and high resolution mass spectrometry [19]. In addition to the mentioned approaches, gas-phase bimolecular reactions have also been reported for lipid structural elucidation. For example, ion/neutral (ion/molecule) reactions in a chemical ionization source using acetonitrile in the reagent gas was shown to reveal C=C double bond positions [20,21,22,23]. Moreover, Blanksby and co-workers introduced ozone-induced dissociation (OzID) and demonstrated its utility in lipid analysis for a variety of lipid species [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Gas-phase ion/ion reactions have also been used as a means for altering lipid ion types for the purpose of structural characterization. This review focuses on recent advances in the development of gas-phase ion/ion reactions for lipid analysis.

1.2. Introduction to gas-phase ion/ion reactions

Gas-phase ion/ion reactions constitute a type of bimolecular reaction in the overall field of gas-phase chemistry. The three major large particle reactions involve collisions between i) two neutral particles, ii) an ion and a neutral particle (ion/molecule), and iii) two oppositely charged ions (i.e., ion/ion). Mass spectrometry is based upon measurements involving gaseous ions such that reactions involving ion/molecule and ion/ion collisions are most relevant. In general, the efficiency of a reaction of interest (i.e., the fractional conversion of a reactant ion of interest to a product ion of interest) is determined by the reaction rate, the time over which the reaction can proceed, and any competing reactions. For any binary reaction of the form:

| (1) |

the reaction rate, −d[A+/0/−]/dt, is second order,

| (2) |

where k represents the rate constant for the reaction. In the dilute gas phase, the rate constant is dependent upon the long-range attraction between the collision partners [32]. In the case of an ion/molecule reaction,

| (3) |

the interaction potential between the ion and molecule at large separation is dominated by the ion-dipole (if the neutral has a permanent dipole) and ion-induced dipole interactions. Polarization theories [31,32,33] are used to estimate rate constants for ion/molecule reactions. Langevin theory represents the first such model and assumes the ion as a point charge and the other reactant as a polarizable neutral [33]. The Langevin rate constant, kLangevin, is given by,

| (4) |

where Z is the unit charge, e is the absolute electron charge, α is polarizability of the neutral reactant, and μ is reduced mass of the ion/neutral pair. Equation 4 estimates the collision rate constant, which is the maximum expected reaction rate constant (i.e., the rate constant for a ‘unit efficient’ ion/molecule reaction). Using this model, the kL for ion/molecule collisions between the anion of oleic acid ([M−H]− of FA 18:1 = 281 Da) and ozone (mass = 48 Da, α = 3.08 Å3 [NIST]) is estimated to be 6.4 × 10−10 cm3 molecule−1 s−1. Endothermic reactions and those with significant barriers have rate constants orders of magnitude smaller than the collision rate constant [34,35] such that most ion/molecule collisions are unreactive. Under the most common conditions used to study ion/molecule reactions, the neutral reactant, B, is present at a constant concentration (e.g., number density), such that the reactions follow pseudo-first order kinetics with the pseudo-first order rate constant being the product of the biomolecular rate constant and the number density of B:

| (5) |

Hence, the number density of the neutral reagent can be used to modulate the overall reaction rate. Ultimately, the magnitude of kL and the number density of the neutral reagent that can be exposed to the analyte ion determine the practical utility of an ion/molecule reaction for ion-type transformation.

In the case of an ion/ion reaction (note that the absolute charge of one of the reactions must be greater than that of the other to generate a charged product),

| (5) |

the strongly attractive mutual attraction of the opposite charges dominates the interaction potential at long range. In this case, it is possible for the oppositely charged reactants to form a stable orbit via their mutual attraction, which serves as the rate limiting process for reaction. The rate constant for the formation of the bound orbit, ki/i, is approximated by the Thomson three-body interaction model [36,37,38,39] as:

| (6) |

where v is the relative velocity, Z1 and Z2 are the unit charges of the reactant ions, e is the electron charge, ε0 is permittivity of vacuum, and μ is the reduced mass. Using this model, the ki/i value for ion/ion collisions between the same anionic oleic acid ([M−H]− of FA 18:1 = 281 Da) and the one of the common ion/ion reaction reagents, magnesium tris-phenanthroline dication ([Mg(Phen)3]2+, mass = 564 Da) (see below) is estimated to be 4.4 × 10−6 cm3 ion−1 s−1. Mutual neutralization is highly exothermic for virtually any combination of anions and cations in the gas phase, which leads to essentially unit efficiency for all ion/ion reactions. In analogy with the ion/molecule reaction case discussed above, the overall ion/ion reaction rate can be modulated with the number density of the reagent ion. Note that the rate constants for ion/ion reactions exceed those for ion/molecule reactions by orders of magnitude but the number densities of reagent ions are generally far lower than those of neutral species used for ion/molecule reactions. Nevertheless, ion/ion reaction rates of 10–1000 s−1 are typically observed using electrodynamic ion traps as reaction vessels with the highest rates observed for highly charged reactants (see Eq. 6) and high reagent ion densities.

As mentioned above, due to the high potential energies associated with the attraction of oppositely-charged ions, a reaction that reduces the total charge of the system can be expected for any combination of oppositely-charged ions. The question is not if a reaction will occur. Rather, the question surrounds the mechanism(s) by which charge is reduced, which is dependent upon the chemical identities of the reactants [40]. Common mechanisms include proton transfer [39,40,41], electron transfer [42,43], metal-ion transfer [44], ion-ion attachment [45,46], and covalent reactions [47,48,49,50]. For a given analyte ion, therefore, the choice of reagent ion is key to effecting the desired change in ion-type. Ion/ion reactions, therefore, allow for derivatization of analyte ions on-line (in the mass spectrometer), significantly reducing the analytical time relative to off-line condensed phase chemistry, such as sample preparation time, reaction time, and possible purification steps after the reaction.

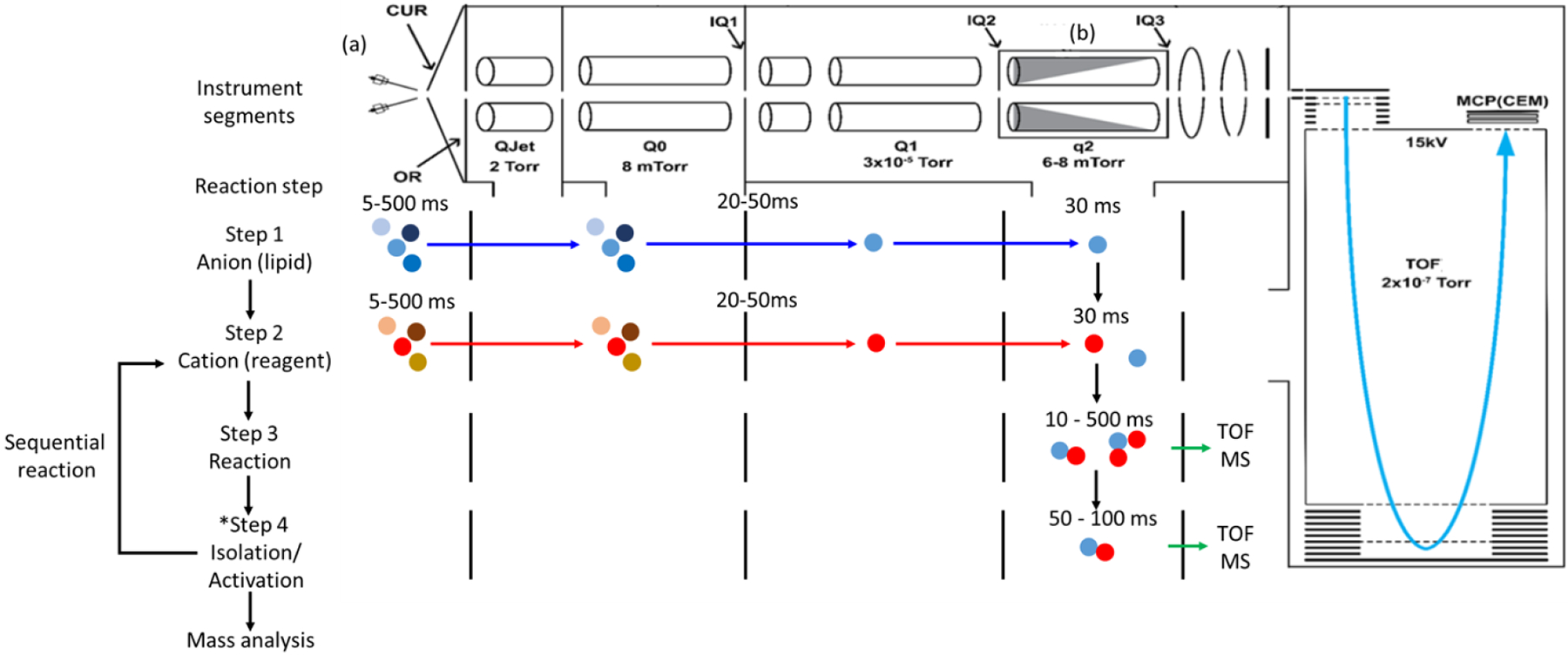

Several tandem mass spectrometer platforms have been used to study ion/ion reactions within the mass spectrometer. We illustrate here a typical work-flow as implemented using a quadrupole/time-of-flight platform (see Figure 1) that has been modified for ion/ion reactions [51]. The major modification to this apparatus was the addition of the ability to apply of AC waveforms to the lenses before (IQ2) and after (IQ3) the collision cell (q2) to allow for mutual storage of ions of opposite polarity. The ions of opposite polarity are generated via nESI emitters placed near the entrance aperture of the instrument. First (step 1), ions (e.g., lipid anions) are generated and transferred into q2. The ions can be mass-selected by apex mass selection using the Q1 quadrupole in RF/DC mode. In step 2, ions of opposite polarity are generated from the second capillary of the dual spray system and then mass selected (Q1) and transferred into q2. AC waveforms are applied to IQ2 and IQ3 lenses to trap and store both polarities of ions in the collision cell. The ion/ion reaction time usually ranges from 10 to 500 ms depending upon ion numbers. After the mutual storage period, the product ions can be further isolated and stored in q2 for another round of reactions, activated for fragmentation analysis, or subjected to the orthogonal acceleration region for mass analysis through TOF mass analyzer. The overall time for a single experiment (single scan) usually ranges from 0.1s to 1s.

Figure 1.

The schematic of mass spectrometer for gas-phase ion/ion reaction in a modified Sciex Triple TOF 5600 Q/TOF system. CUR= curtain plate; OR= orifice; QJet/Q0= RF-only ion guide; IQX= lenses with aperture; Q1= lower pressure RF/DC quadrupole; q2= collisional cell. Representative pressure range throughout the whole mass spectrometer are also listed in the figure. Adapted from [51] copyright 2022 Elsevier.

Thus, gas-phase ion/ion reactions are well-suited for high-throughput shotgun lipidomics analysis based on the relatively short experimental time-scale. In the following sections, we discuss the development of gas-phase ion/ion reactions to facilitate the elucidation of lipid structures for different classes of lipids.

2. Ion/ion reactions for in-depth structural characterization of lipids

Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) plays a major role in many of the ‘omics’ fields (e.g., proteomics, glycomics, metabolomics, lipidomics, etc.) due both to its high sensitivity and exceptional specificity. The latter characteristic derives from the accuracy with which mass measurements can be made, which facilitates determination of elemental composition, and the structural information that can be derived from tandem mass spectrometry. The structural information from a tandem mass spectrometry experiment, which is used for molecular identification and structural isomer distinction, is generally derived from the fragmentation of an ion that is used as a surrogate for the molecule of interest. The information inherent in the identities of the product ions is a function of both the nature of the ion, or ion-types (e.g., protonated molecule, deprotonated molecule, molecular ion, etc.), and the dissociation method (e.g., energetic ion/neutral collisions, photodissociation, etc.) [52]. The ion-type is determined by the nature of the analyte, the ionization method, and ionization conditions, the latter two of which are usually selected to maximize sensitivity. However, the ion-type most readily generated from a given analyte may not yield the structural information of interest using the available dissociation methods. For this reason, it is highly desirable to be able to mix and match ion-type with dissociation methods without a significant compromise in sensitivity. With this in mind, ion/ion reactions are used as a means for converting ion-types that are readily formed directly via the ionization method of choice, but which may not readily yield the structural information of interest, to more informative ion-types both efficiently and on the millisecond time-scale. Ion/ion reactions have been used both prior to the sampling of ions into the mass spectrometer and within the mass spectrometer after one or more stages of mass selection [53]. Electrodynamic ion traps have proved to be particularly useful as reaction vessels because they allow for the storage of both ion polarities simultaneously in overlapping regions of space and are capable of supporting MSn experiments [51,54,55]. Ion-type conversion is accomplished with greatest flexibility within the context of an MSn experiment in which both the analyte and reagent ions can be mass-selected and in which the reaction time and ion storage conditions can be precisely controlled. In the following sections, we describe examples in lipidomics in which ion-types that yield desirable structural information in tandem mass spectrometry are generated from ion-types formed efficiently via electrospray ionization (ESI) that themselves do not yield all of the structural information of interest. The nomenclature and abbreviations generally follow the LIPID MAPS convention [56].

2.1. Lipid cations

Lipid cations are predominantly singly charged and are usually generated as the protonated molecule, [M+H]+, for many lipid classes. PCs, due to the presence of the quaternary ammonium head-group, are most efficiently ionized in the positive ion mode. Collision induced dissociation (CID) of [PC+H]+ ions generates the charged head-group nearly exclusively. Advantage is taken of this behavior to screen for PCs in complex lipid mixtures via a precursor ion scan for the m/z 184 headgroup [1,57]. However, product ions that reveal structural information other than head-group identity are formed at very low abundance, if at all [58]. Anions derived from GPLs, [M−H]−, on the other hand, tend to yield abundant product anions from the fatty acyl chains that can inform about chain length and degree of unsaturation. Therefore, it is of value to be able to convert the cations of this GPL class to anions for further structural characterization. If the analyte ion is singly charged, the reagent ion must be multiply-charged to avoid neutralization and the ion/ion reaction must go through a relatively long-lived complex to result in the charge inversion of the analyte [59,60,61,62]. The first example using gas-phase charge inversion reactions in lipid analysis was described by Stutzman et al., which involved the use of doubly deprotonated 1,4-phenylenedipropionic acid, [PDPA−2H]2−, to react with a protonated PC, [PC+H]+, to form a negatively-charged lipid complex, [PC+PDPA−H]− (Figure 2a). The subsequent ion-trap CID of the complex, [PC+PDPA–H]−, gave rise to a demethylated PC, [PC−CH3]− and structurally informative fatty acyl carboxylate anions, [C16H31CH2COO–H]− and [C14H29CH2COO–H]− (from PC(16:0/18:1)) revealing the FA chain lengths and degrees of unsaturation (Figure 2b) [63]. Furthermore, the cleavage is favored at the sn-2 position [64], which is consistent with the CID behavior of the isomers derived from PC(16:0/18:1) and PC(18:1/16:0) in Figure 2b and 2d. Moreover, Specker et al. reported a relative quantification strategy between for PC sn-positional isomer pairs using the relative abundance ratio, allowing for the quantification of the percentage of the isomers in a binary mixture [65].

Figure 2.

The post-ion/ion reaction mass spectra between doubly deprotonated PDPA and (a) PC(16:0/18:1) and (c) PC(18:1/16:0), and the CID spectra of the charge inverted lipid complex, (b) [PC(16:0/18:1)+PDPA−H]−, and (d) [PC(18:1/16:0)+PDPA−H]−. The ion pair, [C16H31CH2COO–H]− and [C14H29CH2COO–H]−, indicates the carbon numbers and sn-geometry of the fatty acyl composition on PC. Reprinted with permission from [63], copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

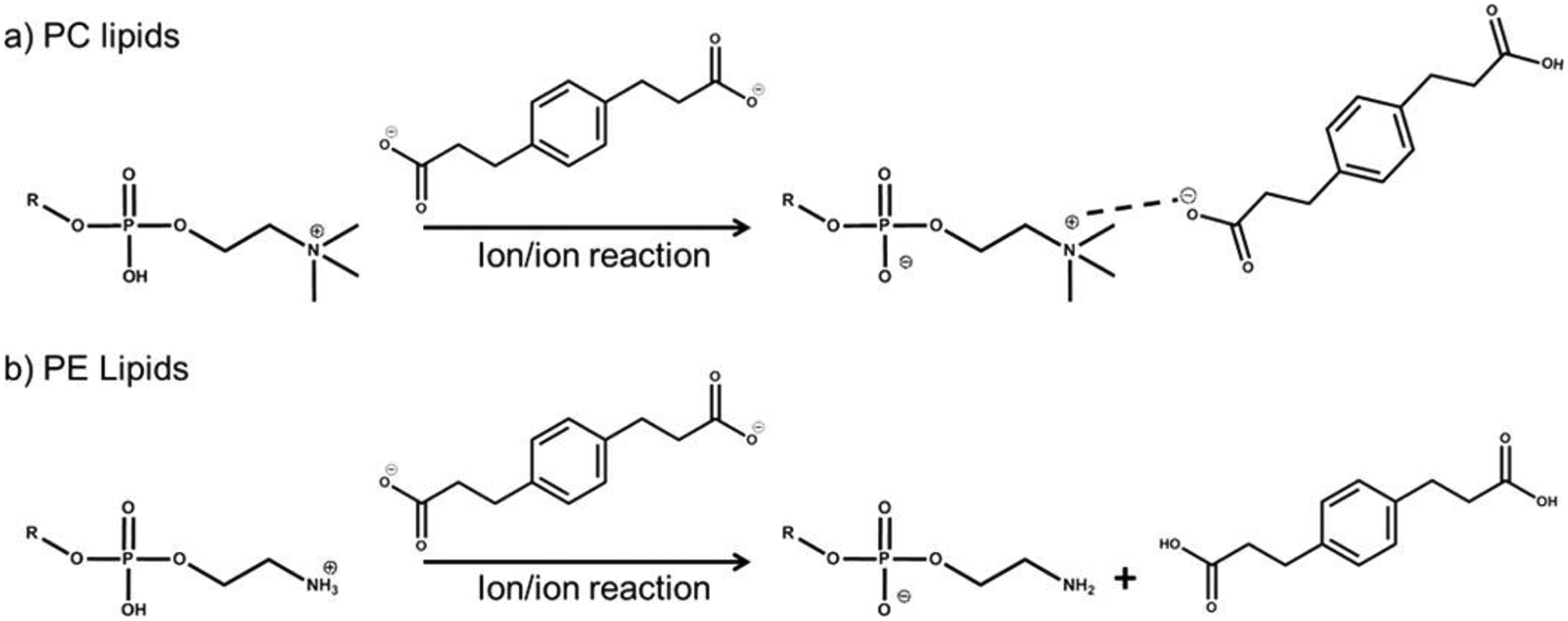

The gas-phase charge inversion reaction using doubly deprotonated PDPA can also be used to differentiate isomeric PC and PE species by producing diagnostic product ions. PC cations undergo charge inversion via attachment to form charge inverted lipid complex ions, [PC+PDPA−H]−, along with demethylated product anions, [PC–CH3]− from the subsequent fragmentation of the complex. The latter ion results from the net transfer of a proton and a methyl cation to the PDPA dianion. In contrast, PE cations undergo charge inversion via “double proton transfer” to produce primarily deprotonated PE anions, [PE–H]− (Scheme 1). This difference in reactivity results in production of diagnostic ions, [PC+PDPA−H]−, [PC–CH3]− and [PE–H]−, that are readily resolved (Figure 3b). Subsequent CID of the diagnostic ions just mentioned generates the fatty acyl carboxylate anions allowing for the identification of the fatty acyl compositions and the sn-geometries from the isomeric PC and PE lipids [28]. The PDPA charge inversion approach was also extended to different phospholipid species, including PC, PE, PS, and SM by coupling condensed-phase trimethylation using 13C-diazomethane to equalize the ionization efficiencies across the various GPL subclasses in positive mode for the PDPA charge inversion reaction [66]. In extension of this work, Franklin et al. coupled trimethylation with the Paternò–Büchi reaction (a condensed-phase photochemical reaction to probe unsaturation site on fatty acyl chain) in solution followed by the PDPA charge inversion reaction to reveal structural information including carbon numbers on the fatty acyl chain, degrees of unsaturation, sn-geometry, and C=C double bond position [67]. The above examples demonstrated the utility of gas-phase ion/ion reactions using PDPA for lipid analysis, and cases in which ion/ion reactions can be combined with condensed-phase chemistries to enhance lipid structural characterization.

Scheme 1.

The reaction between doubly deprotonated PDPA and protonated (a) PC and (b) PE. Reprinted with permission from [28], copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

Figure 3.

(a) The structures of isomeric PC and PE. The mass spectra of isomeric mixture from (b) pre-ion/ion reaction and (c) post-ion/ion reaction with PDPA. Reproduced with permission from [28], copyright 2015 American Chemical Society

2.2. Lipid anions

Many lipid species are most efficiently ionized in the negative ESI mode. This section is focused on ion/ion reactions for the structural characterization of lipids initially formed as anions.

2.2.1. Singly-charged anions

2.2.1.1. Fatty Acids

Fatty acids (FA) are readily observed as singly-deprotonated molecules in negative ESI. Ion trap and low energy beam-type CID of fatty acid anions, however, leads to few structurally informative fragments. Conversion to an ion-type that yields structural information requires reagent cations with at least two charges. Divalent alkaline earth metal complexes, such as magnesium tris-phenanthroline, [Mg(Phen)3]2+, have proved to be useful reagents for the charge inversion of FA anions either formed directly from solution or via the fragmentation of fatty acyl-containing lipid anions such as fatty acid esters of hydroxy fatty acids (FAHFAs) [68], GPLs [69], and CLs [70]. The reaction was first described by Randolph et al., with the objective of localizing unsaturation sites on fatty acids [71]. In this application, free deprotonated FA anions, [FA−H]−, are generated via ESI and reacted with the tris-phenanthroline magnesium reagent to produce a charge inverted lipid complex, [FA−H+Mg(Phen)2]+, followed by subsequent CID to produce, [FA−H+MgPhen]+ (Scheme 2 [71]).

Scheme 2.

The generation of [FA−H+MgPhen]+ ion from gas-phase charge inversion ion/ion reaction between [FA−H]− and [Mg(Phen)3]2+.Reprinted with permission from [71], copyright 2018 American Chemical Society

CID of the complex cation, [FA–H+MgPhen]+, yields a characteristic product ion fragmentation pattern showing a ‘spectral gap’ that allows for the localization of C=C double bond positions on fatty acids. Figure 4 shows examples of CID spectra of [FA–H+MgPhen]+ ions of several monounsaturated FA ions showing the characteristic spectral gaps. Diagnostic fragment ions are obtained whereby the usual 14 Da difference in mass between fragments from C-C bond cleavage shifts to 12 Da at the double bond location (i.e. Figure 4a insert, j’ to C9=C10 is 12 Da, and C9=C10 to i’ is 14Da.) The spectral pattern is highly related to the vinylic suppression of production of C=C double bond cleavages in charge-remote fragmentation (CRF) [72]. The magnesium phenanthroline adduct serves as a fixed-charged site at the FA carboxylate allowing CRF to occur across the fatty acid chain. The [FA−H+MgPhen]+ CID spectra were highly reproducible making the generation of a library from standards useful for unambiguous isomeric distinction and C=C double bond localization with more than one unsaturation site [73]. Combining multiple linear regression analysis with the library, relative quantitation of FA isomers over a broad dynamic range of molar ratios was also demonstrated [73].

Figure 4.

The CID mass spectra of isomeric [FA 18:1−H+MgPhen]+ ions. (a) FA 18:1(n-7), (b) FA 18:1(n-9), and (c) FA 18:1 (n-12). The blue curve highlights the spectral pattern for localization of the double bond. Reprinted with permission from [71], copyright 2018 American Chemical Society

2.2.1.2. Glycerophospholipids

With a slight modification of the workflow described above for FAs, the localization of C=C double bond positions on GPLs is straightforward. In brief, anionic GPLs, [GPL−H]−, release the anionic fatty acids via CID. The FA anions can be subjected to the charge inversion reaction mentioned above and CID workflow to reveal double bond location (Figure 5) [69,74]. This example demonstrates the utility of the described workflow to profile and identify PE 36:2 species in human plasma extract. The workflow can also be applied to the analysis of PC, PE, PS, PI, PG, and PA.

Figure 5.

Example for the determination of fatty acyl composition of PE 36:2 in human plasma extract. (a) Structure of PE (18:0/18:2) (n-6 and 9). (b) The reaction scheme for PE 18:0/18:2(n-6,9) FA identification. (c) The CID spectrum of [PE 36:2–H]−, revealing 3 FA from PE 36:2, including 18:0 (m/z 283), 18:1 (m/z 281), and 18:2 (m/z 279) (d) The post-ion/ion spectrum followed by CID to generate [FA–H+MgPhen]+ from (c). (e) CID spectrum of [FA 18:2 –H+ MgPhen]+ (m/z 483). (f) CID spectrum of [FA 18:1−H+MgPhen]+ (m/z 485). Reprinted with permission from [75], copyright 2020 Elsevier.

Similar to the localization of C=C double bond position, the MgPhen reaction can also be used to identify cyclopropane positions, if present. Charge remote fragmentation along the fatty acyl chain yields distinct fragmentation patterns for a C=C double bond versus a cyclopropane ring. The former generates a spectral gap near the double bond along with a 12 Da spacing between adjacent backbone cleavage peaks adjacent to the double bond, whereas the latter produces doublets with diagnostic neutral loss fragment ions that are not seen in the fragmentation of double bond species (Figure 6). Both features allow for differentiation of a cyclopropane ring from a double bond in fatty acids [70].

Figure 6.

The CID spectra of (a) [FA 19:1(c11)–H+MgPhen]+ (m/z 499.2) and (b) [FA 18:1(n-7)–H+MgPhen]+ (m/z 485.2) and their respective neutral loss CID spectra, highlighting the differences between cyclopropane site and unsaturation site. Reproduced with permission from [70], copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

2.2.1.3. Glycoplipids

Glycolipids are comprised of a carbohydrate headgroup attached to a sphingolipid backbone. Additional possibilities for isomers are present with glycolipids, such as with the headgroup (e.g., glucose vs. galactose) and linkages (e.g., anomers). The magnesium-terpyridine complex cation, [Mg(Terpy)2]2+, was first introduced by Chao and McLuckey to replace [Mg(Phen)3]2+ as the reagent for glycolipids analysis [76]. The major differences between [Mg(Terpy)2]2+ and [Mg(Phen)3]2+ as reagents are (i) one less step of CID is required to produce the targeted charge-inverted lipid complex cation, [M−H+MgTerpy]+ (one Terpy ligand is displaced by the lipid right after the gas-phase ion/ion reaction) and (ii) the mass of the Terpy ligand is 233 Da versus 180 Da for the Phen ligand, eliminating an ambiguity in hexose analysis (i.e. glucose also has a nominal mass at 180 Da). The reaction of [Mg(Terpy)2]2+ with anions of isomeric cerebrosides is shown in Scheme 3, in which MgTerpy cation is nominally indicated to target the deprotonation site on the diastereomeric center of the isomeric monosaccharide head group, glucose and galactose [76].

Scheme 3.

The proposed reaction between deprotonated GSLs and [Mg(Terpy)2]2+. Reprinted with permission from [76], copyright 2020 American Chemical Society

Briefly, the reaction between deprotonated GSLs and [Mg(Terpy)2]2+ produces a charge inverted lipid complex, [GSL−H+MgTerpy]+. CID of this complex yields product ion spectra that reveal in-depth structural information regarding the monosaccharide head group. Figure 7 shows the reaction between deprotonated n-HexCer(d18:1/16:0) and the subsequent CID spectra of three isomeric cerebrosides, revealing distinct product ion spectral patterns across the three isomers, permitting the isomeric differentiation. The predominant neutral loss of 443 Da (loss of the sugar and the sphingosine backbone) in glucosylceramide (GlcCer) and the neutral loss of the Terpy ligand in galactosylceramide (GalCer) distinguish the glucose and galactose head groups (Figure 7c and d). Moreover, the neutral loss of Terpy ligand is absent with α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer, Figure 7b), allowing for the further distinction between alpha or beta glycosidic linkage. The difference in dissociation kinetics between the alpha and beta-galactosylceramides were also reported suggesting the two isomeric lipids undergo distinct fragmentation paths to generate products ion after the charge inversion reaction with MgTerpy. The diagnostic fragment ions were used for both relative and absolute quantitative analysis of the isomers in mixtures [77].

Figure 7.

The CID spectra among cerebrosides after gas-phase ion/ion reaction: (a) post-ion/ion reaction spectrum of cerebroside anion ([n-HexCer−H] with [Mg(Terpy)2]2+ cation; (b) CID spectrum of [α-GalCer−H+MgTerpy]+ (m/z 955.6); (c) CID spectrum of [β-GlcCer−H+MgTerpy]+ (m/z 955.6); (d) CID spectrum of the [β-GalCer−H+MgTerpy]+ (m/z 955.6). The values in parentheses indicate theneutral loss. A lightning bolt signifies the collisionally activated precursor ion. The solid circle (●) indicates the mass selection in the negative ionmode analysis, and the black and white squares (■/□) indicate the positive ion mode analysis with and without mass selection, respectively. Reprinted with permission from [77], copyright 2021 American Chemical Society

The approach can also be used to identify the C=C double bond position on the cerebroside amide bonded fatty acyl chain. Figure 8 shows the representative MS3 spectra of the fragment ion of 443 Da loss from GlcCer(d18:1/18:0) and GlcCer(d18:1/18:1) with the proposed structures in which the amide bonded fatty acyl chains are 18:0 and 18:1, respectively. A similar spectral gap with the 12 Da spacing (ion 398 and 410) at the double bond position on the fatty acyl chain can be found in the result of GlcCer(d18:1/18:1). The overall workflow was used successfully to profile glycolipids in bovine brains [76,77].

Figure 8.

The CID spectra of 443 Da loss ion from (a) [β-GlcCer(d18:1/18:0)−H + MgTerpy]+ and (b) [β-GlcCer(d18:1/18:1(n-9))−H +MgTerpy]+. The inserts give the enlarged spectra of the m/z region 350−500. The red dashed line signifies the special spectral gap pointing tothe double-bond position. The definitions of symbols are the same as those in Figure 7. Reprinted with permission from [77], copyright 2021 American Chemical Society

2.2.3. Multiply charged lipid anions

Multiply charged anions can be the dominant ionic species formed via ESI from some lipid types. Therefore, alternate ion/ion reaction approaches may be appropriate in order to take advantage of the most abundant analyte ion type formed directly via ESI. For example, under typical ESI conditions, cardiolipins tend to generate both singly- and doubly-deprotonated ions (e.g., [CL−H]− and [CL−2H]2−) with the latter being dominant. However, the singly deprotonated species yields abundant fatty acyl chain fragments from all acyl chains while the doubly deprotonated anions do not provide the comprehensive fatty acyl composition from regular low-energy CID [78]. Hence, single proton transfer reactions, using protonated Proton-Sponge™ as the reagent cation, were used to concentrate most of the signal into the singly-charged species [78]. The singly-charged fatty acyl chains can then be subjected to charge inversion reactions to determine sites of unsaturation, as described above.

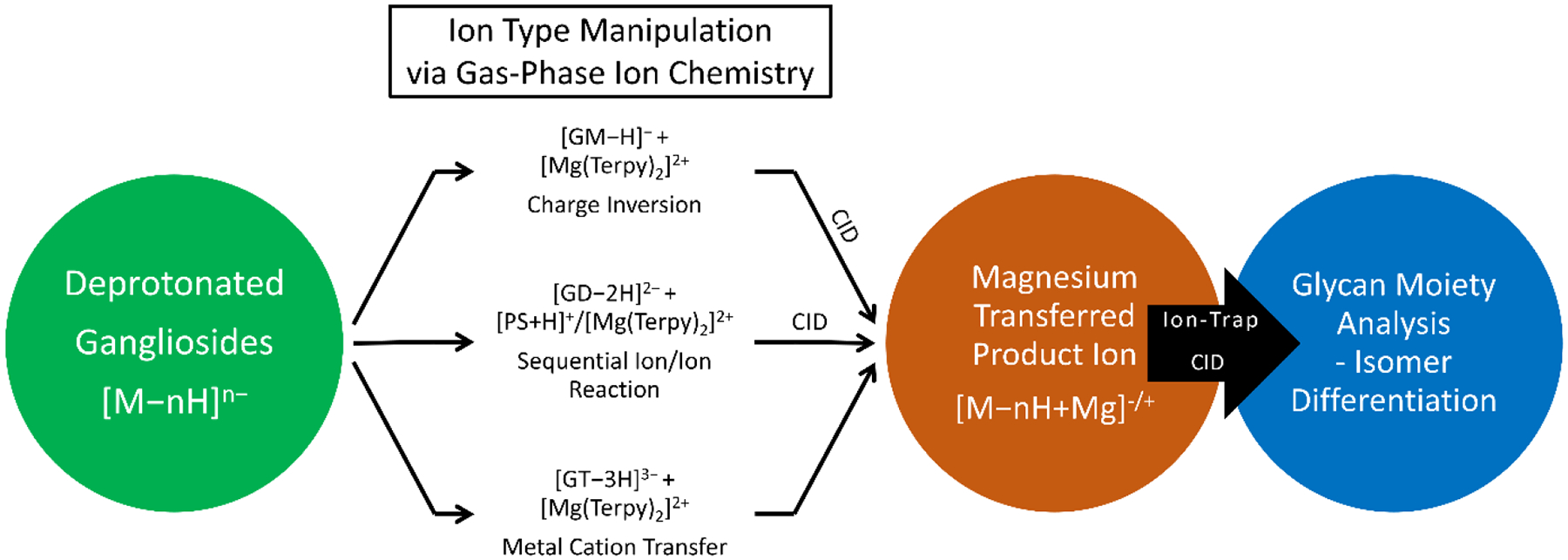

Ion-type manipulation via proton transfer, as illustrated above using the CL example, is one of multiple ion transfer approaches. Metal ion transfer reactions have also been used to yield ion-types that provide useful structural information, as illustrated with gangliosides [79]. The same reagent used for charge inversion of some singly-charged lipids, [Mg(Terpy)2]2+, proved to lead to a net metal ion transfer to gangliosides. The first step of the reaction involves the formation of a long-lived complex with spontaneous loss of one Terpy ligand. A subsequent ion activation step leads to the loss of the second Terpy ligand resulting in the net transfer of Mg2+. The process is summarized below:

| (reaction 1) |

where the ion can either stay the same polarity as the original ion if n>2 or charge inverted when n<2. For some lipid classes, such as FAs, the activation step following the first ligand loss results in covalent bond cleavage of the lipid with retention of one ligand. Gangliosides, with their relatively extensive glycan structures, are apparently able to solvate the metal ion sufficiently well to release the second ligand. Due to the diversity of glycan head groups associated with gangliosides, a single sample preparation strategy for a mixture is likely to lead to the generation of multiple ganglioside charge states. In such a scenario, gas-phase ion/ion chemistry can serve as particularly flexible means for generating optimal ion-types. The general workflow for gangliosides [79] is provided in Scheme 4:

Scheme 4.

The workflow for structural elucidation of the glycan moiety on different classes of ganglioside ions via gas-phase ion/ion reactions. Reprinted with permission from [79], copyright 2021 American Chemical Society

For singly deprotonated gangliosides, for example, GM species, the ion/ion reaction with [Mg(Terpy)2]2+ followed by ion activation leads to a net positively-charged Mg-containing ganglioside, [GM−H+Mg]+ (see reaction 2-2). For gangliosides with a negative charge greater in magnitude than 2− (e.g., GT species), the ion/ion reaction with [Mg(Terpy)2]2+ followed by ion activation leads to a net negatively-charged Mg-containing ganglioside, [GT−nH+Mg](n−2)−. To enable Mg2+ ion transfer onto an initially doubly deprotonated [GT−2H]2− species, a proton transfer reaction (reaction 2-1) using protonated proton sponge™, [PrS+H]+, is performed to reduce the charge state from 2− to 1− (i.e., [GD−H]−). Mg2+ transfer into the charge-reduced ganglioside can then be accomplished via reaction 2-2. Figure 9 shows the results of isomeric differentiation using the sequential ion/ion reaction for GD1 analysis and compared to the conventional CID experiments.

Figure 9.

The CID spectra of isomeric GD1 C36:1. (a) Doubly deprotonated GD1a C36:1, (b) doubly deprotonated GD1b C36:1, (c) magnesium transferred GD1a C36:1, [GD1a−H+Mg]+, and magnesium transferred GD1b C36:1, [GD1b−H+Mg]+. The glycan linkage can be found in the inserts. The definitions of symbols are the same as those in Figure 7. Reprinted with permission from [79], copyright 2021 American Chemical Society

| (reaction 2–1) |

| (reaction 2–2) |

3. Gas-phase ion/ion reactions coupled with imaging techniques for lipid analysis

Gas-phase ion/ion reactions are potentially well-suited for use in the context of mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) applications [65]. The requirement for retaining sample surface spatial information can place constraints on the ionization step that might complicate generating various ion-types. Furthermore, condensed-phase separation techniques, such as liquid chromatography, are difficult to couple with MSI due to the long time-scale of most chromatographic methods and compromises in the retention of spatial information [80,81,82]. Therefore, a gas-phase approach that can generate alternate ion-types for tandem mass spectrometry on the time-scale of an ion imaging experiment has significant potential for enhancing the specificity of an MSI experiment. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) is one of the most popular ionization techniques for MSI (MALDI-MSI) and works well for many lipid classes [83]. Therefore, MALDI may be one of the possible MSI approaches that can couple with gas-phase ion/ion reaction. Specker et al. reported a MALDI approach coupling gas-phase ion/ion reaction using PDPA for mapping PCs in rat brain tissue [65]. As mentioned above, PCs ions are most efficiently generated in the positive ion mode as [PC+H]+ ions. However, mass measurement of protonated PCs alone cannot identify the presence of isomers and tandem mass spectrometry of the cations primarily provides head-group information as mentioned above [56]. Isomeric PC 36:2 ions were reported with at least 2 sn-positional isomers at the same pixel, and a total of up to five sn-positional isomers were profiled across the whole tissue (Figure 11) [65]. In the case illustrated in Figure 11, three isomers (i.e., PC(16:2_18:0), PC(18:2_18:0), and PC(18:1_18:1)) were revealed following the ion/ion reaction and CID. The PC species can also be mapped with MALDI-MSI from their approach based on the MS1 (intact mass results). Further work is needed to generate directly the lipid structural information in the course of a MSI experiment.

Figure 11.

The results from MALDI-MSI-PDPA reaction analysis of rat brain. (a) Ion image for [PC36:2+H]+ (m/z 786.601) from rat brain tissue. (b) The MALDI-MS1 spectrum of protonated [PC36:2+H]+ from the representative location on the sample surface. (c) The post-ion/ion reaction between [PC36:2+H]+ and [PDPA−2H]2−. (d) The CID spectrum of demethylated PC, [PC36:2−CH3]− revealing the profile of fatty acyl content within the PC36:2, including 16:0, 18:2, 18:1, 18:0, and 20:2 fatty acid. Reprinted with permission from [65], copyright 2020 American Chemical Society

3. Conclusions and future perspectives

Gas-phase ion/ion reactions have many characteristics that are attractive for molecular analysis in conjunction with tandem mass spectrometry. They are essentially ‘universal’ in that any combination of oppositely-charged ions will undergo a reaction, they can be driven in millisecond time-scale, and, since both reactants are ions, a high degree of control is afforded over identities of the reactants (via mass selection) and the times over which the reactants are exposed to one another. These characteristics make ion/ion reactions particularly useful for ion-type conversion. Ultimately, the analytical utility/motivation for using ion/ion reactions is the novel or additional information that they can ultimately provide. In the case of lipidomics, there are many cases in which the ability to generate and examine multiple ion-types from a single ion-type can provide complementary structural information. The MSI application, in particular, represents an excellent example in which the generation of different ion-types via the ionization approach may be limited due to the constraints imposed by the need for generating an image (e.g., ideally a single abundant ion-type per component). The potential of the combination of ion/ion chemistry with MSI will be realized using a platform that is optimized for this application. This would entail means for means for admitting ions of opposite polarity that do not compromise each other, a suitable reaction region (e.g., an electrodynamic ion trap that allows for mutual ion polarity storage), and efficient coupling between the reaction region and the ion source(s) and readout (viz., mass analyzer).

To date, several reagents have been described for the manipulation of lipid ion-types. For example, singly-charged GPL cations have been converted to singly-charged anions via reaction with PDPA dianions. PC cations react first by attachment and then, upon activation, transfer a proton and methyl cation to the PDPA dianion. Other GPLs react primarily by double proton transfer. The anions generated from charge inversion yield abundant fatty acyl chain anions that reveal fatty acyl chain carbon numbers and degrees of unsaturation. Relative abundances of the fatty acyl chain anions can reflect sn-substitution. Singly-charged lipid anions, such as fatty acids, GPLs, and glycolipids undergo reactions with divalent metal complexes, such as [Mg(Phen)3]2+ and [Mg(Terpy)2]2+, to yield metal-containing cationic complexes. CID of the cationic complexes has been demonstrated to be capable of localizing double bonds and cyclopropane rings in fatty acyl chains, distinguishing glucose from galactose in glycolipids, and distinguishing glycolipid anomers. Depending upon the extent to which the lipid can solvate a multi-valent metal, metal ion transfer without ligand retention, can also occur to yield cations that are useful in characterizing ganglioside structures. Other reagent ions have been used for specific purposes, such as transferring a proton to a multiply-charged anion (e.g., via reaction with the protonated proton sponge), or electron transfer to multiply-charged lipid cations [84].

The ion/ion reactions reported to date involving lipids represents only a small fraction of the potential for ion/ion chemistry in lipidomics. Both the range of analyte species and the range of reagents are minimally explored. Moreover, several isomer types have yet to be addressed via ion-type manipulation using ion/ion chemistry. These include, for example, cis/trans isomers, fatty acyl chain branching, and the many possibilities for isomerization among glycans in glycolipids. The existing reagents are likely to be useful in applications involving lipid types not yet investigated (e.g. eicosanoids, sulfolipids, saccharolipids, etc.). Further development of reagents based on current designs, such as metal ion identity and oxidation state as well as ligand identity in metal-ligand complex reagents, may prove to be useful in some scenarios. Novel reagents, however, will likely be needed to address the full range of lipid structural characterization challenges. Reagents that are capable of selective functional group-specific reactions, which have already been demonstrated in other contexts [85], may find use for some lipid types. For example, gas-phase ion/ion reactions have been demonstrated to undergo nucleophilic substitution [86], Schiff base formation [47,48], and gas-phase oxidation [49,50]. It may prove to be possible to translate into the gas phase some of the condensed-phase reactions, such as the Paternò–Büchi (PB) photochemical reaction [87] or epoxidation [88], that have been demonstrated to assist structural elucidation of lipids. Also, the combination of condensed-phase reactions with gas-phase ion/ion reactions [66,67] can add further dimensionality. Given the array of gaseous ions that can be generated via modern ionization methods and the strengths of ion/ion reactions, in terms of kinetics and efficiencies, there are many possibilities for novel applications for ion/ion reactions in lipidomics.

Highlights:

Structural information from tandem mass spectrometry of lipids is highly dependent upon ion type.

Gas phase ion/ions reactions are efficient and rapid means for converting one lipid ion-type into another.

Reagent ions have been developed for the conversion of lipid analyte cations to anions as well as lipid anion analytes to cations.

Gas-phase ion/ion reactions have been show to be useful for shotgun lipidomics and this utility will expand to a wider range of lipid classes as novel reagents are developed.

Acknowlegdements

The authors acknowledge funding support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Grants GM R37-45372 and GM R01-118484.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Brügger B, Erben G, Sandhoff R, Wieland FT, Lehmann WD, Quantitative analysis of biological membrane lipids at the low picomole level by nano-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 94 (1997) 2339–2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kishimoto K, Urade R, Ogawa T, Moriyama T, Nondestructive Quantification of Neutral Lipids by Thin-Layer Chromatography and Laser-Fluorescent Scanning: Suitable Methods for “Lipidome” Analysis. Biochem. Biophys 281 (2001) 657–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Han X, Gross RW, R. W., Global analyses of cellular lipidomes directly from crude extracts of biological samples by ESI mass spectrometry: a bridge to lipidomics. J. Lipid Res 44 (2003) 1071–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gross RW, Han X, Lipidomics at the Interface of Structure and Function in Systems Biology. Chem. Biol 18 (2011) 284–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fahy E, Subramaniam S, Brown HA, Glass CK, Merrill AH Jr., Murphy RC, Raetz CRH, Russell DW, Seyama Y, Shaw W, Shimizu T, Spener F, van Meer G, Van Nieuwenhze MS, S,H. White, J.L Witztum, E.A. Dennis, A comprehensive classification system for lipids. J. Lipid Res 46 (2005) 839–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fahy E, Subramaniam S, Murphy RC, Nishijima M, Raetz CRH, Shimizu T, Spener F, van Meer G, Wakelam MJO, Dennis FA, Update of the LIPID MAPS comprehensive classification system for lipids. J Lipid Res, 50 (Suppl.) (2009) S9–S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fahy E, Sud M, Cotter D,Subramaniam S, LIPID MAPS online tools for lipid research. Nucleic Acids Res 35 (Web Server issue) (2007) W606–W612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Yèagle PL, Lipid regulation of cell membrane structure and function. FASEB J 3 (1989) 1833–1842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Komura N, Suzuki KG, Ando H, Konishi M, Koikeda M, Imamura A, Chadda R, Fujiwara TK, Tsuboi H, Sheng R, Cho W, Furukawa K, Furukawa K, Yamauchi Y, Ishida H, Kusumi A, Kiso M, Raft-based interactions of gangliosides with a GPI-anchored receptor. Nat. Chem. Biol 12 (2016) 402–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sezgin E, Levental L, Mayor S, Eggeling C, The mystery of membrane organization: composition, regulation and roles of lipid rafts. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol 18 (2017) 361–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang M, Wang C, Han X, Selection of internal standards for accurate quantification of complex lipid species in biological extracts by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry—What, how and why? Mass Spectrom. Rev 36 (2017) 693–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bowman AP, Heeren RMA, Ellis SR, Advances in mass spectrometry imaging enabling observation of localised lipid biochemistry within tissues. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem 120 (2019) 115197. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bonney JR, Prentice BM, Perspective on Emerging Mass Spectrometry Technologies for Comprehensive Lipid Structural Elucidation. Anal. Chem 93 (2021) 6311–6322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Han X, Gross RW, The foundations and development of lipidomics. J. Lipid Res 63 (2022) 100164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Heiles S, Advanced tandem mass spectrometry in metabolomics and lipidomics—methods and applications. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 413 (2021) 5927–5948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Paglia G, Smith AJ, Astarita G, Ion mobility mass spectrometry in the omics era: Challenges and opportunities for metabolomics and lipidomics. Mass Spectrom. Rev 41 2022. 722–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lu H, Zhang H, Xu S, Li L, Review of Recent Advances in Lipid Analysis of Biological Samples via Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Metabolites 11 (2021) 781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhang W, Jian R, Zhao J, Liu Y, Xia Y, Deep-lipidotyping by mass spectrometry: recent technical advances and applications. J. Lipid Res 63 (2022) 100219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Züllig T; Köfeler HC, High resolution mass spectrometry in lipidomics. Mass Spectrom. Rev 40 (2021) 162–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lawrence P, Brenna JT, Acetonitrile Covalent Adduct Chemical Ionization Mass Spectrometry for Double Bond Localization in Non-Methylene-Interrupted Polyene Fatty Acid Methyl Esters. Anal. Chem 78 (2006) 1312–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Michaud AL, Lawrence P, Adlof R, Brenna JT, On the formation of conjugated linoleic acid diagnostic ions with acetonitrile chemical ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 19 (2005) 363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Michaud AL, P Yurawecz M, Delmonte P, Corl BA, Bauman DE, Brenna JT, Identification and Characterization of Conjugated Fatty Acid Methyl Esters of Mixed Double Bond Geometry by Acetonitrile Chemical Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 75 (2003) 4925–4930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Thomas MC, Mitchell TW, Harman DG, Deeley JM, Murphy RC, Blanksby SJ, Elucidation of Double Bond Position in Unsaturated Lipids by Ozone Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 79 (2007) 5013–5022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Thomas MC, Mitchell TW, Harman DG, Deeley JM, Nealon JR, Blanksby SJ, Ozone-Induced Dissociation: Elucidation of Double Bond Position within Mass-Selected Lipid Ions. Anal. Chem 80 (2008) 303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mitchell TW, Pham H, Thomas MC, Blanksby SJ, Identification of double bond position in lipids: From GC to OzID. J. Chromatogr. B 877 (2009) 2722–2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Brown SHJ, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ, Analysis of unsaturated lipids by ozone-induced dissociation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta – Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids 1811 (2011) 807–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Pham HT; Maccarone AT; Thomas MC; Campbell JL; Mitchell TW; Blanksby SJ, Structural characterization of glycerophospholipids by combinations of ozone- and collision-induced dissociation mass spectrometry: the next step towards “top-down” lipidomics. Analyst 139 (2014) 204–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Rojas-Betancourt S, Stutzman JR, Londry FA, Blanksby SJ, McLuckey SA, Gas-Phase Chemical Separation of Phosphatidylcholine and Phosphatidylethanolamine Cations via Charge Inversion Ion/Ion Chemistry. Anal. Chem 87 (2015) 11255–11262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Poad BLJ, Green MR, Kirk JM, Tomczyk N, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ, High-Pressure Ozone-Induced Dissociation for Lipid Structure Elucidation on Fast Chromatographic Timescales. Anal Chem 2017, 89 (7), 4223–4229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Poad BLJ; Zheng X; Mitchell TW; Smith RD; Baker ES; Blanksby SJ, Online Ozonolysis Combined with Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry Provides a New Platform for Lipid Isomer Analyses. Anal. Chem 90 (2018) 1292–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Paine MRL, Poad BLJ, Eijkel GB, Marshall DJ, Blanksby SJ, Heeren RMA, Ellis SR, Mass Spectrometry Imaging with Isomeric Resolution Enabled by Ozone-Induced Dissociation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 57 (2018) 10530–10534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Le Picard S, Biennier L, Monnerville M, Guo H, Gas-phase Chemistry: Reactive Bimolecular Collisions. In Gas-Phase Chemistry in Space, IOP Publishing: 2019; pp 3–1 to 3–48. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gioumousis G, Stevenson DP, Reactions of Gaseous Molecule Ions with Gaseous Molecules. V. Theory. J. Chem. Phys 29 (1958) 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Olmstead WN, Brauman JI, Gas-phase nucleophilic displacement reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 99 (1977) 4219–4228. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pellerite MJ, I Brauman J, Intrinsic barriers in nucleophilic displacements. J. Am. Chem. Soc 102 (1980) 5993–5999. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Stephenson JL; McLuckey SA, Ion/Ion Reactions in the Gas Phase: Proton Transfer Reactions Involving Multiply-Charged Proteins. J Am Chem Soc 1996, 118 (31), 7390–7397. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Thomson JJ, XXIX. Recombination of gaseous ions, the chemical combination of gases, and monomolecular reactions. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 47 (1924) 337–378. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wells JM, A Chrisman P, McLuckey SA, Formation and Characterization of Protein−Protein Complexes in Vacuo. J. Am. Chem. Soc 125 (2003) 7238–7249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].McLuckey SA, Huang T-Y, Ion/Ion Reactions: New Chemistry for Analytical MS. Anal. Chem 81 (2009) 8669–8676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Scalf M, Westphall MS, Smith LM, Charge Reduction Electrospray Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 72 (2000) 52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].McLuckey SA, Wu J, Bundy JL, Stephenson JL, Hurst GB, Oligonucleotide Mixture Analysis via Electrospray and Ion/Ion Reactions in a Quadrupole Ion Trap. Anal. Chem 74 (2002) 976–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Herron WJ, Goeringer DE, McLuckey SA, Gas-phase Electron Transfer Reactions from Multiply-Charged Anions to Rare Gas Cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 117 (1995) 11555–11562. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Syka JEP, Coon JJ, Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Peptide and protein sequence analysis by electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 (2004) 9528–9533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Newton KA, Amunugama R, McLuckey SA, Gas-Phase Ion/Ion Reactions of Multiply Protonated Polypeptides with Metal Containing Anions. J. Phys. Chem. A 109 (2005) 3608–3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Abdillahi AM, Lee KW, McLuckey SA, Mass Analysis of Macro-molecular Analytes via Multiply-Charged Ion Attachment. Anal. Chem 92 (2020) 16301–16306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Pitts-McCoy AM, Abdillahi AM, Lee KW, McLuckey SA, Multiply Charged Cation Attachment to Facilitate Mass Measurement in Negative-Mode Native Mass Spectrometry, Anal. Chem 94 (2022) 2220–2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Han H, McLuckey SA, Selective Covalent Bond Formation in Polypeptide Ions via Gas-Phase Ion/Ion Reaction Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 131 (2009) 12884–12885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wang N, Pilo AL, Zhao F, Bu J, McLuckey SA, Gas-phase rearrangement reaction of Schiff-base-modified peptide ions. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 32 (2018) 2166–2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Pilo AL, Zhao F, McLuckey SA, Selective Gas-Phase Oxidation and Localization of Alkylated Cysteine Residues in Polypeptide Ions via Ion/Ion Chemistry. J. Proteome Res 15 (2016) 3139–3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Pilo AL, Zhao F, McLuckey SA, Gas-Phase Oxidation via Ion/Ion Reactions: Pathways and Applications. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 28 (2017) 991–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bhanot JS, Fabijanczuk KC, Abdillahi AM, Chao H-C, Pizzala NJ, Londry FA, Dziekonski ET, Hager JW, McLuckey SA, Adaptation and operation of a quadrupole/time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometer for high mass ion/ion reaction studies. Int. J. Mass Spectrom 478 (2022) 116874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].McLuckey SA, Mentinova M, Ion/Neutral, Ion/Electron, Ion/Photon, and Ion/Ion Interactions in Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Do We Need Them All? Are They Enough? J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 22 (2011) 3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Xia Y, Liang X, McLuckey SA, Pulsed Dual Electrospray Ionization for Ion/Ion Reactions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 16 (2005) 1750–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].McLuckey SA, E Reid G, Wells JM, Ion Parking during Ion/Ion Reactions in Electrodynamic Ion Traps. Anal. Chem 74 (2002) 336–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Xia Y, Chrisman PA, Erickson DE, Liu J, Liang X, Londry FA, Yang MJ, McLuckey SA, Implementation of Ion/Ion Reactions in a Quadrupole/Time-of-Flight Tandem Mass Spectrometer. Anal Chem 78 (2006) 4146–4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Liebisch G, Fahy E, Aoki J, Dennis EA, Durand T, Ejsing CS, Fedorova M, Feussner I, Griffiths WJ, Köfeler H, Merrill AH Jr., Murphy RC, O’Donnell VB, Oskolkova O, Subramaniam S, Wakelam MJO, Spener F, Update on LIPID MAPS classification, nomenclature, and shorthand notation for MS-derived lipid structures. J. Lipid Res 61 (2020) 1539–1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Chao H-C, Chen G-Y, Hsu L-C, Liao H-W, Yang S-Y, Li Y-L, Tang S-C, Tseng YJ, Kuo C-H, Using precursor ion scan of 184 with liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry for concentration normalization in cellular lipidomic studies. Anal Chim Acta 971 (2017) 68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Castro-Perez JM, Kamphorst J, DeGroot J, Lafeber F, Goshawk J, Yu K, P Shockcor J, Vreeken RJ, Hankemeier T, Comprehensive LC−MSE Lipidomic Analysis using a Shotgun Approach and Its Application to Biomarker Detection and Identification in Osteoarthritis Patients. J. Proteome Res 9 (2010) 2377–2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].He M, Emory JF, McLuckey SA, Reagent Anions for Charge Inversion of Polypeptide/Protein Cations in the Gas Phase. Anal. Chem 77 (2005) 3173–3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].He M, McLuckey SA, Increasing the Negative Charge of a Macroanion in the Gas Phase via Sequential Charge Inversion Reactions. Anal. Chem 76 (2004) 4189–4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].He M, McLuckey SA, Two Ion/Ion Charge Inversion Steps To Form a Doubly Protonated Peptide from a Singly Protonated Peptide in the Gas Phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 125 (2003) 7756–7757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Chao H-C, Shih M, McLuckey SA, Generation of Multiply Charged Protein Anions from Multiply Charged Protein Cations via Gas-Phase Ion/Ion Reactions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 31 (2020) 1509–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Stutzman JR, Blanksby SJ, McLuckey SA, Gas-Phase Transformation of Phosphatidylcholine Cations to Structurally Informative Anions via Ion/Ion Chemistry. Anal. Chem 85 (2013) 3752–3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Castro-Perez J, Roddy TP, Nibbering NM, Shah V, McLaren DG, Previs S, Attygalle AB, Herath K, Chen Z, Wang SP, Mitnaul L, Hubbard BK, Vreeken RJ, Johns DG, Hankemeier T, Localization of fatty acyl and double bond positions in phosphatidylcholines using a dual stage CID fragmentation coupled with ion mobility mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 22 (2011) 1552–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Specker JT, Van Orden SL, Ridgeway ME, Prentice BM, Identification of Phosphatidylcholine Isomers in Imaging Mass Spectrometry Using Gas-Phase Charge Inversion Ion/Ion Reactions. Anal. Chem 92 (2020) 92 13192–13201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Betancourt SK, Canez CR, Shields SWJ, Manthorpe JM, Smith JC, McLuckey SA, Trimethylation Enhancement Using 13C-Diazomethane: Gas-Phase Charge Inversion of Modified Phospholipid Cations for Enhanced Structural Characterization. Anal. Chem 89 (2017) 9452–9458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Franklin ET, Shields SWJ, Manthorpe JM, Smith JC, Xia Y, McLuckey SA, Coupling Headgroup and Alkene Specific Solution Modifications with Gas-Phase Ion/Ion Reactions for Sensitive Glycerophospholipid Identification and Characterization. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom (2020) 938–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Randolph CE, Marshall DL, Blanksby SJ, McLuckey SA, Charge-switch derivatization of fatty acid esters of hydroxy fatty acids via gas-phase ion/ion reactions. Anal. Chim. Acta 1129 (2020) 31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Randolph CE, Blanksby SJ, McLuckey SA, Toward Complete Structure Elucidation of Glycerophospholipids in the Gas Phase through Charge Inversion Ion/Ion Chemistry. Anal. Chem 92 (2020) 1219–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Randolph CE, Shenault DSM, Blanksby SJ, McLuckey SA, Localization of Carbon–Carbon Double Bond and Cyclopropane Sites in Cardiolipins via Gas-Phase Charge Inversion Reactions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 32 (2021) 455–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Randolph CE, Foreman DJ, Betancourt SK, Blanksby SJ, McLuckey SA, Gas-Phase Ion/Ion Reactions Involving Tris-Phenanthroline Alkaline Earth Metal Complexes as Charge Inversion Reagents for the Identification of Fatty Acids. Anal. Chem 90 (2018) 12861–12869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Tomer KB, Crow FW, Gross ML, Location of double-bond position in unsaturated fatty acids by negative ion MS/MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc 105 (1983) 5487–5488. [Google Scholar]

- [73].Randolph CE, Foreman DJ, Blanksby SJ, McLuckey SA, Generating Fatty Acid Profiles in the Gas Phase: Fatty Acid Identification and Relative Quantitation Using Ion/Ion Charge Inversion Chemistry. Anal. Chem 91 (2019) 9032–9040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Randolph CE, Shenault DSM, Blanksby SJ, McLuckey SA, Structural Elucidation of Ether Glycerophospholipids Using Gas-Phase Ion/Ion Charge Inversion Chemistry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 31 (2020) 1093–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Randolph CE, Blanksby SJ, McLuckey SA, Enhancing detection and characterization of lipids using charge manipulation in electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Chem. Phys. Lipids 232 (2020) 104970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Chao H-C, McLuckey SA, Differentiation and Quantification of Diastereomeric Pairs of Glycosphingolipids Using Gas-Phase Ion Chemistry. Anal. Chem 92 (2020) 13387–13395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Chao H-C, McLuckey SA, In-Depth Structural Characterization and Quantification of Cerebrosides and Glycosphingosines with Gas-Phase Ion Chemistry. Anal. Chem 93 (2021) 7332–7340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Randolph CE, Fabijanczuk KC, Blanksby SJ, McLuckey SA, Proton Transfer Reactions for the Gas-Phase Separation, Concentration, and Identification of Cardiolipins. Anal. Chem 92 (2020) 10847–10855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Chao H-C, McLuckey SA, Manipulation of Ion Types via Gas-Phase Ion/Ion Chemistry for the Structural Characterization of the Glycan Moiety on Gangliosides. Anal. Chem 93 (2021) 15752–15760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Amstalden van Hove ER, Smith DF, Heeren RMA, A concise review of mass spectrometry imaging. J. Chromatogr. A 1217 (2011) 3946–3954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Weickhardt C, Moritz F, Grotemeyer J, Time-of-flight mass spectrometry: State-of the-art in chemical analysis and molecular science. Mass Spectrom. Rev 15 (1996) 139–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Ren J-L, Zhang A-H, Kong L, Wang X-J, Advances in mass spectrometry-based metabolomics for investigation of metabolites. RSC Advances 8 (2018) 22335–22350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Buchberger AR, DeLaney K, Johnson J, Li L, Mass Spectrometry Imaging: A Review of Emerging Advancements and Future Insights. Anal. Chem 90 (2018) 240–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Liang X, Liu J, LeBlanc Y, Covey T, Ptak AC, Brenna JT, McLuckey SA, Electron transfer dissociation of doubly sodiated glycerophosphocholine lipids. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2007, 1783–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Prentice BM, McLuckey SA, Gas-phase ion/ion reactions of peptides and proteins: acid/base, redox, and covalent chemistries. Chem. Commun 49 (2013) 947–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Bu J, Fisher CM, Gilbert JD, Prentice BM, McLuckey SA, Selective Covalent Chemistry via Gas-Phase Ion/ion Reactions: An Exploration of the Energy Surfaces Associated with N-Hydroxysuccinimide Ester Reagents and Primary Amines and Guanidine Groups. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 27 (2016) 1089–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Ma X, Xia Y, Pinpointing Double Bonds in Lipids by Paternò-Büchi Reactions and Mass Spectrometry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 53 (2014) 2592–2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Feng Y, Chen B, Yu Q, Li L, Identification of Double Bond Position Isomers in Unsaturated Lipids by m-CPBA Epoxidation and Mass Spectrometry Fragmentation. Anal. Chem 91 (2019) 1791–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]