Abstract

Background:

The interaction between cerebral vessel disease (CVD) pathology and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology in the development of dementia is controversial. We examined the association of cerebral vascular neuropathology and cerebrovascular risk factors with mild stage of Alzheimer’s dementia and cognitive function.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study included men and women aged 60 years or over who had yearly clinical assessments and had agreed to brain autopsy at the time of death, and who contributed to data stored at the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) in the USA. Cognitively normal and impaired subjects with presumptive aetiology of AD, including mild cognitive impairment (ADMCI) and dementia (Alzheimer’s dementia), and with complete neuropathological data, were included in our analyses. We used neuropsychological data proximate to death to create summary measures of global cognition and cognitive domains. Systematic neuropathological assessments documenting the severity of cerebral vascular pathology were included. Logistic and linear regression analyses corrected for age at death, sex and Lewy body pathology were used to examine associations of vessel disease with severity of Alzheimer’s disease dementia, and cognitive function respectively.

Results:

No significant relationship was observed between late life risk factors and Alzheimer’s dementia. The severity of arteriosclerosis and presence of global infarcts/lacunes were related to mild Alzheimer’s dementia (B=0.423, p<0.001;B=0.366, p=0.026), and the effects were significant after adjusting for neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (B=0.385, p<0.001;B=0.63, p=0.001). When vascular brain injuries were subdivided into old and acute/subacute types, we found that old microinfarcts and old microbleeds were associated with mild Alzheimer’s dementia (B=0.754, p=0.007; B=2.331, p=0.032). The old microinfarcts remained significantly associated with mild Alzheimer’s dementia after correcting for AD pathologies (B=1.31, p<0.001). In addition, the number of microinfarcts in cerebral cortex had significant relation with mild Alzheimer’s dementia, whether or not the data were corrected for AD pathologies (B=0.616, p=0.016; B=0.884, p=0.005). Atherosclerosis, arteriosclerosis and white matter rarefarction were found to be significantly associated with faster progression of Alzheimer’s dementia (B=0.068, p=0.001; B=0.046, p=0.016, B=0.081, p=0.037), but white matter rarefarction no longer had a significant effect after adjusting for AD pathologies. We also found that the severity of atherosclerosis was related to impairment in processing speed (β=−0.112, p=0.006) and executive function (β=−0.092, p=0.023). Arteriosclerosis was significantly associated with language (β=−0.103, p=0.011) and global cognition (β=−0.098, p=0.016) deficits.

Conclusion:

Our study found the significant relation of global, old, acute/subacute and regional cerebral vascular pathologies, but not white matter rarefaction, to the onset and severity of Alzheimer’s dementia. We also showed that late-life risk factors were found to have no relation with Alzheimer’s dementia, and the increased risk of dementia with APOE ε4 is not mediated by CVD. The best interpretation of these findings is that CVD has an additive effect with AD pathologies in the development and progression of what is clinically diagnosed as Alzheimer’s dementia, and it is very likely that CVD and AD are to a major degree independent pathologies.

Keywords: Cerebrovascular pathology, Alzheimer’s disease, Alzheimer’s dementia, Cognition

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic, age-related neurodegenerative disorder that leads to gradual cognitive decline. AD is characterised pathologically by accumulation of extracellular amyloid plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. However, the aetiological role of these two pathologies in AD is still a matter of debate. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that one third of elderly individuals did not present with dementia symptoms even though intermediate and high levels of neuritic plaques and tau pathology were present 1. This suggests the probable involvement of other pathologies in the onset and progression of Alzheimer dementia.

Dementia was primarily considered a disorder of cerebral vascular impairment prior to Alois Alzheimer’s discovery of Alzheimer’s type pathologies, because of the evidence of vascular pathologies in patients with decline in cognitive domains. There is some emerging evidence for vascular contribution to Alzheimer’s dementia 2. Mixed pathology is common in the elderly. A neuropathological study showed that about 80% of individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia have concomitant vascular pathologies such as microinfarcts and atherosclerosis of cerebral arteries 3. In addition, cerebral vascular disease (CVD) and AD share several risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, smoking and excessive alcohol, and have some shared pathobiology, such as blood brain barrier leakage, cerebral hypoperfusion, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and metabolic dysfunction. Additionally, there is cumulative evidence that several cardiovascular risk gene polymorphisms also increase the risk of developing Alzheimer dementia 4. Owing to the failure of almost all clinical trials using drugs targeting Aβ and tau protein in treating or preventing Alzheimer’s dementia, a greater understanding of the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s dementia is important and examining the role of CVD has become paramount.

In this article, we used pathological data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centre (NACC) in the USA to identify the relationship between cerebrovascular pathologies and the mild stage of clinical Alzheimer’s dementia. We also examined the differences between pathologies across various stages of AD. Finally, we looked at the contribution of CVD pathologies to cognitive dysfunction in all groups.

Methods

Data selection

Subjects were drawn from autopsied participants in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) clinical cases series gathered from approximately 31 NIA funded Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers (ADRCs) across the United States 5–7. Data collected from these Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers and submitted to NACC between September 2005 and December 2019 were included. Clinical Data used in this study were obtained from Uniform Data Set (UDS) in NACC, including age at death, sex, education years, APOE status, hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesteromia, atrial fibrillation, heart attack, smoking, alcohol abuse and dementia diagnosis through the NIA-AA or NINCDS/ADRDA criteria. Neuropathological data were collected via a standardized Neuropathology Form and Coding Guidebook. The following NACC neuropathology variables were used: NACCNEUR (CERAD score), NACCBRAA (Braak staging), NACCARTE (arteriolosclerosis), NACCAVAS (atherosclerosis), NACCINF (infarcts and lacunes), and NACCMICR (microinfarcts).

Procedures

Inclusion criteria were: subjects aged 60 years and over; subjects with at least 1 visit and neuropathological assessment; cognitively normal and impaired subjects with presumptive aetiology of AD, including mild cognitive impairment (ADMCI) and dementia (Alzheimer’s dementia); the time interval between last visit and death less than 2 years. Exclusion criteria were: familial Alzheimer’s dementia and cognitive impairment of other aetiology; subjects with missing variables of AD pathologies and CVD pathologies ( for certain analysis such as regional CVD pathologies and the relationship with Alzheimer’s dementia and cognition analysis, subjects were removed if they have relative data missed). Demented subjects were further classified into 3 groups according to global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR ® Dementia Staging Instrument) score: Mild Alzheimer’s dementia, global CDR score ≤1; Moderate Alzheimer’s dementia, global CDR score=2; Severe Alzheimer’s dementia, global CDR score =3.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data for demographics, health history and neuropathological characteristics were reported for normal, ADMCI and different stages of Alzheimer’s dementia. We examined the association between CVD pathologies with mild stage of Alzheimer’s dementia. The simple logistic regression model was utilized to examine the contribution to mild Alzheimer’s dementia by severity of atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis and presence of infarcts/lacunes, microinfarcts, haemorrhages/microbleeds and white matter rarefaction. First, the regression model was only corrected for age at death, sex and Lewy body pathology, and a second regression model corrected additionally for neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques (AD pathologies). NACC applied a new version (version 10) of data collection method reporting regional CVD pathologies, old and acute/subacute infarcts/lacunes, microinfarcts, haemorrhages and microbleeds, which had a smaller sample size. Regression analysis was performed to determine their association with mild Alzheimer’s dementia. In the primary analyses, the severity of atherosclerosis and arteriosclerosis was grouped as not present, mild, moderate, and severe. Secondary analyses examined the difference in proportion in cerebral vascular neuropathologies from mild to severe stage of Alzheimer’s dementia. In this analysis, the proportion of moderate to severe vessel pathologies was utilized for atherosclerosis and arteriosclerosis. A regression model was used to study the association of brain pathologies with dementia stages. The statistically significant pathologies were plotted with their percentage at each stage.

Neuropsychological test performance was assessed using the UDS neuropsychological battery 6. The tests were grouped into cognitive domains based on a previous factor analysis of the UDS battery 8. The episodic memory domain was measured by the two Logical Memory Tests, the language domain by the Boston Naming Test and the object naming tests, attention/working memory by the Digit Span tests, processing speed domain by the Trail Making test A and Digit Symbol test, and executive function domain by Trail Making test B. Cognition data assessed at the last visit antemortem were utilised and the individual test score was converted to a z-score by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation among cognitively normal subjects at initial visit. The z-scores for the tests within each domain were then averaged to obtain a standardized domain-specific composite score. Averaging all the domain-specific scores created a global cognitive composite score.

The last analysis investigated whether the presence of APOE ε4 allele (one or two alleles) or vascular risk factors (at least one including hypertension, diabetes, or smoking) affected the association between pathologies and mild Alzheimer’s dementia by using mediation regression analysis 9.

Results

Demographics

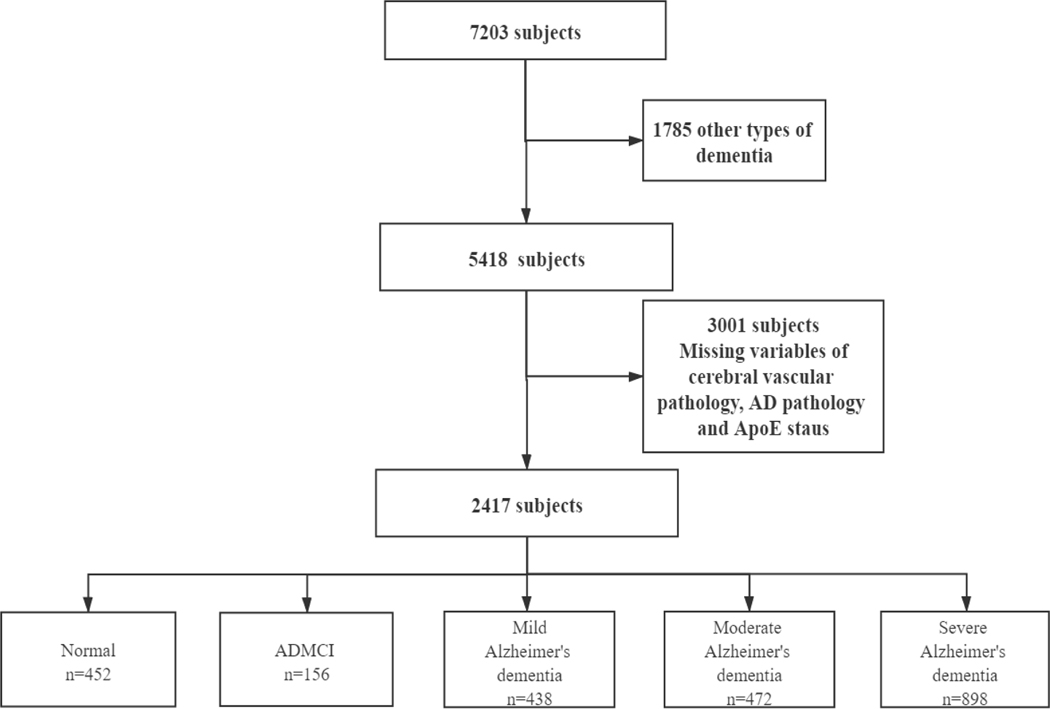

Figure 1 illustrates the selection process based on inclusion and exclusion criteria in our study. There were 7203 participants having the last visit in less than 2 years before death. Only participants who were cognitively normal or had cognitive impairment with presumptive aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease were included in our study. Individuals (N=1785) with other types of dementia were excluded so as to focus on Alzheimer’s dementia. Finally, 2417 subjects were selected after excluding participants missing the following variables: neuritic plaque, neurofibrillary tangles, atherosclerosis, arteriosclerosis, infarcts/lacunes, microinfarcts, haemorrhages/microbleeds, white matter rarefaction, Lewy body pathology, and APOE genotype.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the Selection Process

There were 452 ‘cognitive’ healthy controls, 156 with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) of presumptive AD aetiology, and 1808 with Alzheimer’s dementia in three stages (Mild: n=438, Moderate: n=472, Severe: n=898). The demographic, clinical, and neuropathological characteristics of individuals included in the study are shown in table 1. As expected, demented patients were significantly younger than cognitively normal subjects at the time of death (Mild: t=−2.888, p=0.004, Moderate: t=−6.091, p<0.001, Severe: t=−12.993, p<0.001). The MCI group had the highest age compared with normal and AD. The sex distribution was quite different across the different groups, that is, the male proportion was highest in severe dementia and lowest in cognitively normal individuals. Normal subjects had a higher degree of education than Mild AD patients (t=−2.038, p=0.042), but there was no difference in years of education between cognitively normal participants and middle or Severe AD dementia or MCI subjects.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Normal (n=452) | ADMCI (n=156) | Mild Alzheimer’s dementia (n=438) | Moderate Alzheimer’s dementia (n=472) | Severe Alzheimer’s dementia (n=898) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

|

| |||||

| Age_visit (years) | 85.94±8.44 | 89.74±7.25 a | 84.24±9.12 b | 82.18±10.28 c | 79.15±10.17 d |

| Age_death (years) | 86.76±8.42 | 90.46±7.08 a | 85.09±8.97 b | 83.05±10.21 c | 79.75±10.15 d |

| Interval between last visit and death (months) | 9.86±5.67 | 9.1±5.54 | 10.85±6.46 b | 10.72±6.24 c | 7.6±5.88 d |

| Sex (male%) | 44.00% | 50.60% | 58.7% b | 54% c | 52.6% d |

| Education (years) | 16.68±9.16 | 16.24±7.42 | 15.66±5.06 b | 15.92±9.19 | 15.87±8.11 |

| APOE ε4 carriers | b | c | d | ||

| No e4 allele | 77.80% | 76.30% | 55.10% | 51.30% | 39.50% |

| 1 copy of e4 allele | 21.50% | 23.10% | 37.40% | 39.20% | 45.90% |

| 2 copy of e4 allele | 0.70% | 0.60% | 7.50% | 9.50% | 14.60% |

| Smoke recent | 3.6% (448) | 0.60% (155) | 3.2% (434) | 1.5% (470) c | 1.5% (884) d |

| Alcohol abuse | 4.2% (451) | 3.80% | 6.9% (437) | 6.60% | 8.7% (889) |

| Diabetes | 15.90% | 11.50% | 14.4% (437) | 12.5% c | 12.9% (893) |

| Hypertension | 70% (450) | 72.40% | 66.70% | 62.70% | 55% (892) d |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 55.6% (446) | 51.6% (155) | 57.5% (435) | 54.90% | 56.7% (883) |

| Heart attack | 14% (449) | 16.70% | 12.8% (437) | 11.50% | 8.0% (892) d |

| Atrial fibrillation | 25.9% (448) | 27.70% | 18.8% (436) | 16.2% c | 13.2% (893) d |

| Pathology | |||||

| Braak stage | a | b | c | d | |

| Stage 0 | 5.30% | 0.60% | 4.10% | 2.10% | 1.90% |

| Stage I/II | 47.80% | 29.50% | 15.10% | 8.10% | 5.70% |

| Stage III/IV | 39.60% | 51.30% | 34.70% | 22.50% | 9.90% |

| Stage V/VI | 7.30% | 18.60% | 46.10% | 67.40% | 82.50% |

| Neuritic plaque | a | b | c | d | |

| No | 50.00% | 28.20% | 18.70% | 9.30% | 4.60% |

| Sparse | 24.30% | 29.50% | 13.20% | 7.80% | 4.90% |

| Moderate | 17.30% | 31.40% | 24.70% | 22.00% | 17.40% |

| Frequent | 8.40% | 10.90% | 43.40% | 60.80% | 73.20% |

| Atherosclerosis | |||||

| No | 17.70% | 15.40% | 16.00% | 18.20% | 19.60% |

| Mild | 38.30% | 36.50% | 39.50% | 41.70% | 35.70% |

| Moderate | 31.00% | 37.20% | 31.50% | 28.20% | 29.20% |

| Severe | 13.10% | 10.90% | 13.00% | 11.90% | 15.50% |

| Arteriosclerosis | a | b | c | d | |

| No | 23.90% | 16.00% | 18.30% | 18.60% | 20.20% |

| Mild | 46.50% | 36.50% | 35.40% | 34.30% | 31.00% |

| Moderate | 22.80% | 33.30% | 32.40% | 31.60% | 32.30% |

| Severe | 6.90% | 14.10% | 13.90% | 15.50% | 16.60% |

| Infarcts/lacunes | 21.00% | 25.60% | 26% b | 19.90% | 19.30% |

| Hemorrhages | 5.80% | 3.80% | 7.80% | 5.90% | 6.50% |

| Microinfarcts | 22.80% | 25.60% | 26.50% | 23.90% | 17.90% |

| WM rarefarction | 25.20% | 32.70% | 26.70% | 32.8% c | 34.1% d |

| Lewy body | 16.60% | 14.10% | 30.1% b | 35% c | 39.5% d |

p<0.05 in the comparison between Control and ADMCI

p<0.05 in the comparison between Control and early stage Alzheimer’s dementia

p<0.05 in the comparison between Control and middle stage Alzheimer’s dementia

p<0.05 in the comparison between Control and late stage Alzheimer’s dementia

ADMCI: Mild cognitive impairment with presumptive etiology of Alzheimer’s disease; WM: White matter

There was a significantly larger proportion of APOE ε4 carriers in the AD group compared with MCI and cognitively normal subjects, while no difference was found between normal and MCI group. Age and sex were both adjusted for further analysis of vascular risk factors and brain pathologies. With regards to modifiable vascular risk factors, there were significantly smaller proportions of current smokers in moderate and severe Alzheimer’s dementia compared with normal group, while no difference was found between mild Alzheimer’s dementia and normal. Current alcohol abuse did not differ across groups. Other risk factors including diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, heart attack and atrial fibrillation were not significantly different between MCI or Mild Alzheimer’s dementia and normal. However, the proportion of diabetes was lower in Moderate Alzheimer’s dementia, and hypertension, heart attack and atrial fibrillation were significantly lower in Severe Alzheimer’s dementia compared with normal.

AD pathologies including neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaque were significantly more severe in cognitively impaired patients than normal subjects. The severity of AD pathologies increased, as expected, from MCI to Severe Alzheimer’s dementia. Cerebral vessel disease such as atherosclerosis was only significantly different between normal and Severe AD, showing more severe pathologies after adjustment for age, sex and education. Alzheimer’s dementia overall did not show a significant difference in atherosclerosis with normal control. However, arteriosclerosis presented consistently more progressed pathologies in all three stages of AD dementia compared with normal. Cerebral vascular brain injuries except infarcts/lacunes showed no difference between normal group and MCI or mild of stage of Alzheimer’s dementia. The proportion of infarcts/lacunes were higher in mild AD dementia and white matter rarefaction was more prevalent in the middle and severes of AD dementia. All vascular brain injuries except white matter rarefaction showed a decreasing trend from early to Severe of Alzheimer’s dementia. Lewy bodies, which represent another age-related and cognition related pathological hallmark, were significantly higher in dementia groups and no differences were found between Alzheimer’ dementia and ADMCI group.

Contribution of cerebral vascular pathologies to mild Alzheimer’s dementia

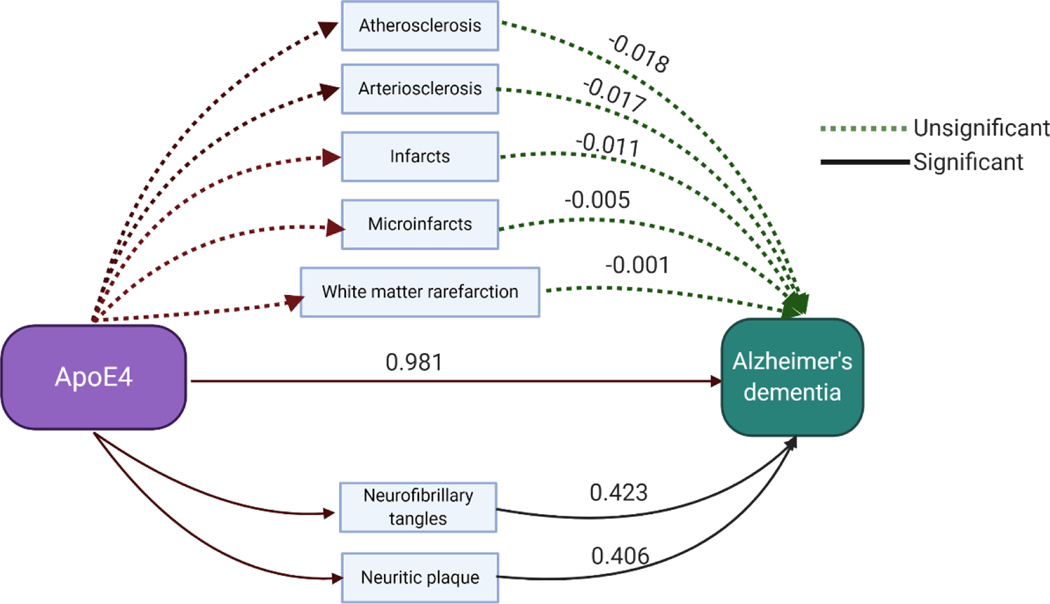

The primary objective of this study was to explore the contribution of cerebral vascular pathologies to the development of AD dementia. Therefore, the comparison between normal controls and mild Alzheimer’s dementia was used to examine the differential occurrence of CVD pathologies in the Milds of AD. Estimated coefficients of total CVD pathologies for the regression model are presented in table 2. Simple regression analysis was performed adjusting for age at death, sex, education and Lewy body pathology. Arteriosclerosis and infarcts/lacunes were found significantly related to mild Alzheimer’s dementia. The potential contribution of CVD pathologies to Alzheimer’s dementia independent of AD pathologies was examined in regression model 2, adjusting additionally for AD pathologies. We observed that arteriosclerosis and infarcts/lacunes were significantly related with mild Alzheimer’s dementia even after correcting for AD pathologies. Only APOE ε4 genotype showed significant relationship to Alzheimer’s dementia using a simple regression model adjusted for age, sex and Lewy body pathology (B=0.981, p<0.001). Mediation analysis was conducted to explore whether the relationship between APOE ε4 and Alzheimer’s dementia was mediated by brain pathology (figure 2). As shown in the plot, the contribution of APOE ε4to dementia was partially mediated by neurofibrillary tangles (B=0.423) and neuritic plaques (B=0.406) instead of any form of cerebral vascular pathology.

Table 2.

Relation of total cerebrovascular pathology to mild Alzheimer’s dementia

| B coefficient a | P value a | B coefficient b | P value b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular pathology | ||||

|

| ||||

| Atherosclerosis | 0.087 | 0.264 | ||

| Arteriosclerosis | 0.423 | <0.001 | 0.385 | <0.001 |

| Infarcts/lacunes | 0.366 | 0.026 | 0.63 | 0.001 |

| Hemorrhages/microbleeds | 0.324 | 0.241 | ||

| Microinfarcts | 0.289 | 0.074 | ||

| White matter raefarction | 0.076 | 0.631 | ||

Simple regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, education and lewy body pathology

Simple regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, education, lewy body pathology and AD pathologies.

Figure 2.

Mediation regression analysis on relation of APOE4 with Alzheimer’s dementia through brain pathologies.

The data of old and acute/subacute infarcts/lacunes, microinfarcts, haemorrhages and microbleeds and regional CVD pathologies were only collected in the newest version (version 10) and therefore the sample size of these data was limited. As a result, 190 cognitively normal, 73 ADMCI, 152 mild Alzheimer’s dementia, 182 moderate Alzheimer’s dementia and 397 severe Alzheimer’s dementia were finally included in our study. Results of the relationship between old and acute/subacute cerebrovascular pathologies to mild Alzheimer’s dementia are shown in table 3. The presence of microinfarcts and microbleeds was significantly related to mild Alzheimer’s dementia even after correction for neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques. None of the other pathologies was found to be significantly associated with mild Alzheimer’s dementia. We further studied the effect of old regional CVD pathologies and found that only the number of microinfarcts in cerebral cortex was related to mild Alzheimer’s dementia regardless of whether the data were corrected for AD pathologies or not.

Table 3.

Relation of old and acute/subacute cerebrovascular pathology to mild Alzheimer’s dementia

| B coefficient a | P value a | B coefficient b | P value b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old vascular pathology | ||||

|

| ||||

| Infarcts/lacunes | 0.555 | 0.088 | ||

| Microinfarcts | 0.754 | 0.007 | 1.31 | <0.001 |

| Hemorrhages | −0.69 | 0.425 | ||

| Microbleeds | 2.331 | 0.032 | 2.247 | 0.064 |

|

| ||||

| Acute/subacute vascular pathology | ||||

|

| ||||

| Infarcts/lacunes | 0.71 | 0.176 | ||

| Microinfarcts | 0.241 | 0.628 | ||

| Hemorrhages | 0.38 | 0.051 | ||

| Microbleeds | 0.998 | 0.264 | ||

Sinmple regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, education and lewy body pathology

Simple regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, education, lewy body pathology and AD pathologies.

Differential cerebral vascular pathologies across severity levels of Alzheimer’s dementia

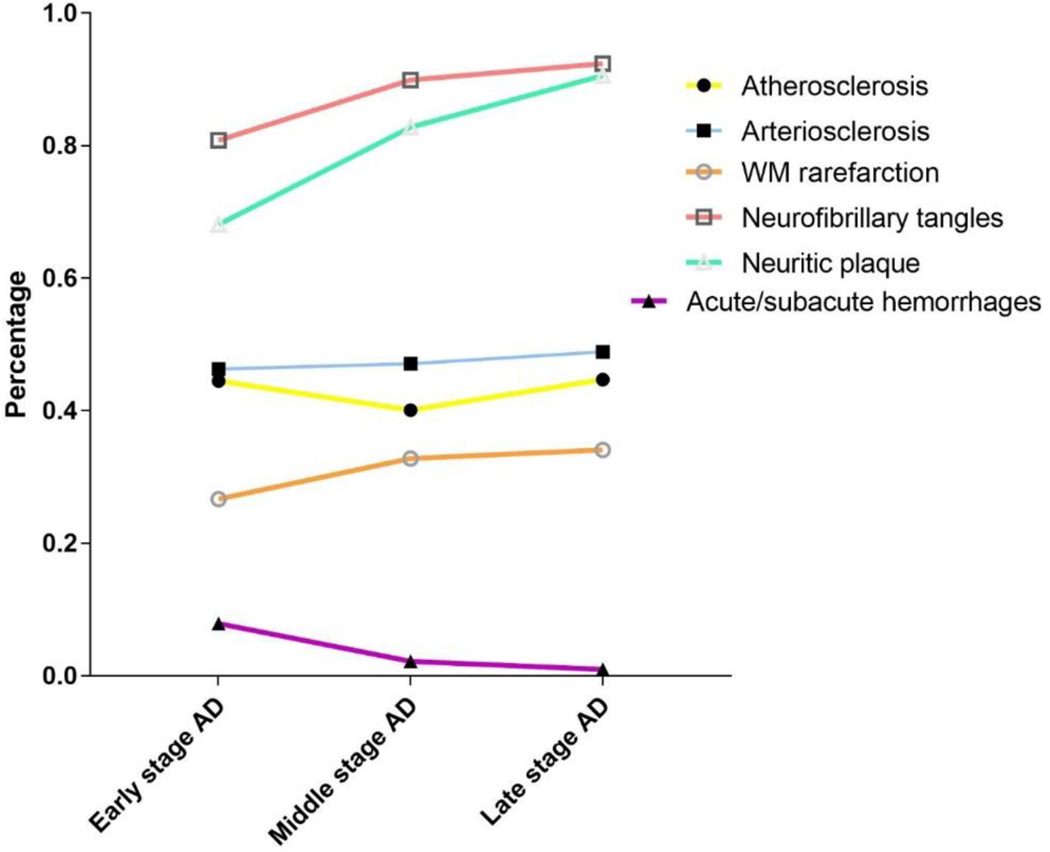

To examine the differential contribution of vascular pathologies to various levels of severity of Alzheimer’s dementia, simple regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, education and lewy body pathology was performed (supplementary table 1) and the percentages of these significant pathologies were plotted in figure 3. Proportion of moderate and severe atherosclerosis, arteriosclerosis neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaque were used. Consistently, and as expected, both neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaque, which are the two main pathological hallmarks of AD, increased from mild to severe Alzheimer’s dementia. The trajectories of cerebral vascular pathologies were variable. Proportions of atherosclerosis, arteriosclerosis and white matter rarefaction increased with increasing severity. However, the number of acute/sub-acute haemorrhages showed an inverse relationship.

Figure 3.

Percentage of significant brain pathologies across the spectrum of Alzheimer’s dementia severity

According to findings from our regression analysis, atherosclerosis and arteriosclerosis were significantly related to the severity of dementia, whether or not the data were adjusted for AD pathologies. White matter rarefaction was significantly greater in severe dementia, but was not significant after correcting for AD pathologies. Other cerebral vascular pathologies did not show significant association with severity of dementia.

Association between brain pathologies and cognition

609 subjects were included in the cognition analysis after excluding subjects with missing data on cognitive tests. Five cognitive domains consisting of attention, memory, language, processing speed and executive function, as well as global cognition were studied in relation to brain pathologies (table 5). In the simple regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, education and Lewy body pathology, AD pathologies, such as neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaque, was found to be significantly associated with cognitive function in all 5 domains. With regard to CVD pathologies, the severity of atherosclerosis was related to impairment in processing speed and executive function. As well, arteriosclerosis was significantly associated with language and global cognitive deficits, and correlated with impaired attention, memory and processing speed, although the latter did not reach statistical significance.

Table 5. Relationship of brain pathologies to cognitive function.

Simple regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, education and lewy body pathology.

| Pathology | Attention | Memory | Language | Processing speed | Executive function | Global | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | |

| Vascular pathology | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Atherosclerosis | −0.032 | 0.434 | −0.013 | 0.76 | −0.032 | 0.44 | −0.112 | 0.006 | −0.092 | 0.023 | −0.074 | 0.07 |

| Arteriosclerosis | −0.081 | 0.051 | −0.078 | 0.056 | −0.103 | 0.011 | −0.077 | 0.055 | −0.072 | 0.076 | −0.098 | 0.016 |

| Infarcts/lacunes | −0.02 | 0.626 | 0.033 | 0.419 | 0.012 | 0.768 | −0.063 | 0.111 | −0.064 | 0.11 | −0.032 | 0.426 |

| Hemorrhages/microbleeds | −0.06 | 0.199 | −0.071 | 0.078 | −0.056 | 0.161 | 0.006 | 0.88 | −0.02 | 0.621 | −0.044 | 0.272 |

| Microinfarcts | 0 | 0.996 | 0.063 | 0.123 | 0.047 | 0.246 | 0.043 | 0.277 | 0.034 | 0.392 | 0.045 | 0.26 |

| WM rarefarction | 0.008 | 0.839 | 0.01 | 0.808 | −0.004 | 0.923 | −0.038 | 0.336 | 0.014 | 0.734 | 0.001 | 0.985 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| AD pathology | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Neurofibrillary tangles | −0.287 | <0.001 | −0.41 | <0.001 | −0.367 | <0.001 | −0.27 | <0.001 | −0.305 | <0.001 | −0.394 | <0.001 |

| Neuritic plaque | −0.247 | <0.001 | −0.44 | <0.001 | −0.399 | <0.001 | −0.253 | <0.001 | −0.307 | <0.001 | −0.397 | <0.001 |

Discussion

In this study, a total of over 2400 participants aged 60 and over who had an autopsy were included to study the relationship of CVD pathologies with Alzheimer’s dementia. About 1000 subjects were included to analyse regional and acute/subacute CVD pathologies. Of those, over 600 people were screened to explore the relationship of brain pathologies to cognitive domains. We first examined the demographics and brain pathologies of participants. Age at death was significantly lower in individuals with diagnosed Alzheimer’s dementia, especially with those at the severe end. This is consistent with previous studies showing demented subjects die at an earlier age than cognitively ‘healthy’ individuals. The male proportion was higher in MCI and Alzheimer’s dementia compared with controls, which is different from much evidence 10 suggesting that women are at a higher risk of Alzheimer’s dementia. This may represent an ascertainment bias in the NACC database, considering that it is a clinical sample. Our data analyses were corrected for age and sex to reduce the selection bias in autopsy data.

As the most important genetic risk factor, APOE*4 carrier status was higher in those with severe dementia. Strong evidence from clinical and basic research suggests APOE4 increases the risk of AD dementia by driving earlier and more abundant amyloid pathology, influencing tau pathology, tau-mediated neurodegeneration and microglial responses to AD-related pathologies 11. In addition, our study showed that the contribution of APOE4 to AD dementia was only partially mediated by amyloid beta and tau pathology but not through cerebral vascular lesions 12. A recent study showed widespread APOE immunoreactivity in the VaD brain which included evidence of fragmentation of the APOE protein. Therefore, it may be concluded that harbouring APOE ε4 alleles elevates the risk for AD, but not to the same extent in CVD. Most other modifiable risk factors in late life, including hypertension, heart attack and atrial fibrillation did not differ between control and Alzheimer’s dementia. The relationship between cognitive decline and blood pressure has been debated. A recent retrospective study on using a cohort aged 90+ 13 showed that the age of onset of hypertension >80 had a significantly lower risk of developing dementia, and participants with an onset age of 90+ years had the lowest risk. Most reports have examined cohorts of older patients and with short follow up periods and concluded that there was no association between cognitive decline and higher cholesterolemia 14. In addition, a study reported a higher incidence of cognitive impairment in familial hypercholesterolemia 15. Taken together, early but not late life vascular risk factors are significant risk factor for cognitive decline.

We used a simple regression analysis to study the relation of CVD pathologies to mild stage of Alzheimer’s dementia. It is to some extent possible to explore the contribution of CVD pathologies to the onset of Alzheimer’s dementia dependent or independent of AD pathologies, since mild stage is close to the start of clinical symptoms. We found a significant relationship of increased proportion of arteriosclerosis and infarcts/lacunes to dementia 16. The relationships remained significant after adjusting for neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaque. These findings suggest an independent contribution of CVD pathologies to Alzheimer’s dementia, and partially explains why about one third of participants with intermediate and severe AD pathologies do not show dementia symptoms. By examining old and acute/subacute cerebral vascular pathologies, we found that old microinfarcts and old microbleeds were greater even in mild AD dementia relative to controls (table 3). As well, the number of microinfarcts in the cerebral cortex was observed to be associated with mild Alzheimer’s dementia. The unchanged significance after correcting for AD pathologies suggested that microinfarcts might have additive contribution to Alzheimer’s dementia. Our data showed that microbleeds did not contribute to Alzheimer’s dementia after correcting for AD pathologies, suggesting that the cerebral microbleeds are possibly related to cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer’s dementia subjects. No significant relationship was observed between acute/subacute CVD pathologies and Alzheimer’s dementia. It is very likely that the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia was not made in those with acute CVD pathologies, such as recent stroke, but chronic CVD was a significant contributor even though the clinical diagnosis was Alzheimer’s dementia.

The severity of atherosclerosis, arteriosclerosis and white matter rarefaction was greatest in severe dementia. The independent effect of these two vessel pathologies might support their additive contribution to the development of Alzheimer’s dementia. Even though white matter rarefaction was not increased in mild Alzheimer’s dementia, it was significantly correlated with severity, but the effect was non-significant after adjusting for AD pathologies (Figure 3 and supplementary table 1), This suggests that white matter rarefaction is possibly an integral part of AD pathologies and not exclusively driven by cerebrovascular pathologies.

In order to fully understand the contribution of CVD pathologies to cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s dementia, we analysed the relationship between total CVD pathologies and impairment in 5 different cognitive domains. The severity of arteriosclerosis was associated with significant deficits in most cognitive domains. Moreover, atherosclerosis was associated with processing speed and executive function, which is a hallmark of clinical vascular type cognitive impairment (table 5). Our data are consistent with previous findings that peripheral atherosclerosis is associated with cognitive deficits 17. Another study showed that CVD, including arteriosclerosis or lipohyalinosis, was inversely correlated with the CDR score. Recently, one study showed that a greater severity in cerebral atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis was associated with lower levels of cognitive function 18. Taken together, these finding further support the major contribution of vascular pathologies to the diagnosis of dementia in AD.

Our study has some limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional post-mortem study, and may not be representative of the general population. Moreover, our groups were not fully matched and we needed to control for age, sex, and Lewy body pathology to reduce bias. Secondly, our cross-sectional study does not reveal the causal effects of pathologies to AD dementia, and cautious interpretation is therefore necessary. Thirdly, we mainly used dichotomous or categorical data of risk factors and pathologies which might not reflect the complete characteristics of these variables. In our study, we were not able to know the age of onset of cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes. Prospective epidemiological cohorts that come to autopsy are the best samples to examine the role of historical risk factors.

However, our data has some strength. The sample size was relatively large, with more than 400 samples in control and mild dementia groups. The subjects had been assessed in research centres and harmonised clinical and pathological criteria had been used. Our data support the view that CVD has an additive effect with AD pathologies in the development and progression of what is clinically diagnosed as Alzheimer’s dementia, and it is very likely that CVD and AD are to a major degree independent pathologies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary table 1. Relation of CVD pathology and AD to progress with Alzheimer’s dementia.

Table 4.

Relation of old regional cerebrovascular pathologies to mild Alzheimer’s dementia

| B coefficient a | P value a | B coefficient b | P value b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infarcts/lacunes | ||||

| Cerebral cortex | 0.657 | 0.117 | ||

| Periventricular white matter | 1.043 | 0.191 | ||

| Deep gray matter/Internal capsule | 0.805 | 0.114 | ||

| Brainstem/Cerebellum | 0.264 | 0.583 | ||

| Microinfarcts | ||||

| Cerebral cortex | 0.616 | 0.016 | 0.884 | 0.005 |

| Subcortical/Periventricular white matter | 0.809 | 0.126 | ||

| Subcortical gray Matter | 0.278 | 0.123 | ||

| Brainstem/Cerebellum | 0.067 | 0.874 | ||

| Microbleeds | ||||

| Cerebral cortex | 18.994 | 0.99 | ||

| Subcortical/Periventricular white matter | 1.341 | 0.084 | ||

| Subcortical gray Mtter | 18.279 | 0.998 | ||

| Brainstem/Cerebellum | 7.083 | 0.999 | ||

Simple regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, education and lewy body pathology

Simple regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, education, lewy body pathology and AD pathologies.

Acknowledgement

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P30 AG062428-01 (PI James Leverenz, MD) P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P30 AG062421-01 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P30 AG062422-01 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI Robert Vassar, PhD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P30 AG062429-01(PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P30 AG062715-01 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

References

- 1.Azarpazhooh MR, Avan A, Cipriano LE, et al. A third of community-dwelling elderly with intermediate and high level of Alzheimer’s neuropathologic changes are not demented: A meta-analysis. Ageing research reviews 2019;58:101002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attems J, Jellinger KA. The overlap between vascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease--lessons from pathology. BMC Med 2014;12:206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toledo JB, Arnold SE, Raible K, et al. Contribution of cerebrovascular disease in autopsy confirmed neurodegenerative disease cases in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centre. Brain 2013;136:2697–2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broce IJ, Tan CH, Fan CC, et al. Dissecting the genetic relationship between cardiovascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 2019;137:209–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, van Belle G, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) Database: an Alzheimer disease database. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2004;18:270–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2006;20:210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serrano-Pozo A, Qian J, Monsell SE, Frosch MP, Betensky RA, Hyman BT. Examination of the clinicopathologic continuum of Alzheimer disease in the autopsy cohort of the National Alzheimer Coordinating Center. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2013;72:1182–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayden KM, Jones RN, Zimmer C, et al. Factor structure of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centers uniform dataset neuropsychological battery: an evaluation of invariance between and within groups over time. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2011;25:128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee H, Herbert RD, McAuley JH. Mediation Analysis. JAMA 2019;321:697–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prince M, Ali GC, Guerchet M, Prina AM, Albanese E, Wu YT. Recent global trends in the prevalence and incidence of dementia, and survival with dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther 2016;8:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamazaki Y, Zhao N, Caulfield TR, Liu CC, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: pathobiology and targeting strategies. Nat Rev Neurol 2019;15:501–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohn TT, Day RJ, Sheffield CB, Rajic AJ, Poon WW. Apolipoprotein E pathology in vascular dementia. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014;7:938–947. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corrada MM, Hayden KM, Paganini-Hill A, et al. Age of onset of hypertension and risk of dementia in the oldest-old: The 90+ Study. Alzheimers Dement 2017;13:103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arvanitakis Z, Schneider JA, Wilson RS, et al. Statins, incident Alzheimer disease, change in cognitive function, and neuropathology. Neurology 2008;70:1795–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zambon D, Quintana M, Mata P, et al. Higher incidence of mild cognitive impairment in familial hypercholesterolemia. Am J Med 2010;123:267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Orantes M, Wiestler OD. Vascular pathology in Alzheimer disease: correlation of cerebral amyloid angiopathy and arteriosclerosis/lipohyalinosis with cognitive decline. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2003;62:1287–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rafnsson SB, Deary IJ, Fowkes FG. Peripheral arterial disease and cognitive function. Vasc Med 2009;14:51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Relation of cerebral vessel disease to Alzheimer’s disease dementia and cognitive function in elderly people: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:934–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary table 1. Relation of CVD pathology and AD to progress with Alzheimer’s dementia.