Abstract

Objectives

To compare the efficacy and efficiency between clear aligners and 2 × 4 fixed appliances for correcting maxillary incisor position irregularities in the mixed dentition.

Materials and Methods

The sample comprised 32 patients from 7 to 11 years of age randomly allocated into two parallel treatment groups: the clear aligners group, 14 patients (6 girls, 8 boys) with a mean initial age of 9.33 years (standard deviation [SD] = 1.01) treated with clear aligners; and the fixed appliances group, 13 patients (9 girls, 4 boys) with a mean initial age of 9.65 years (SD = 0.80) treated with partial (2 × 4) fixed appliances. Digital models were acquired before treatment and after appliance removal. Primary outcomes were incisor irregularity index and treatment time. Secondary outcomes were arch width, perimeter, length, size and shape, incisor leveling, incisor mesiodistal angulation, plaque index, and white spot lesion formation (International Caries Detection and Assessment System index). Intergroup comparisons were evaluated using t-tests or Mann-Whitney U-tests with Holm-Bonferroni correction (P < .05).

Results

Treatment time was approximately 8 months in both groups. No intergroup differences were observed for changes in any of the variables. Similar posttreatment arch shapes were observed in both groups.

Conclusions

Clear aligners and 2 × 4 mechanics displayed similar efficacy and efficiency for maxillary incisor position corrections in the mixed dentition. The choice of appliance should be guided by clinician and family preference.

Keywords: Interceptive orthodontics, Fixed orthodontic appliances, 3D printing

INTRODUCTION

Prevalence of malocclusion in the mixed dentition can range from 39% to 93%, depending on sex, ethnic group, age, and type of malocclusion.1,2 Dental crowding, interdental spacing, and increased overjet are commonly associated with appearance dissatisfaction and negatively affect a child's oral health–related quality of life.3,4

Simplified “two by four” (2 × 4) orthodontic mechanics with brackets bonded to the four permanent incisors and tubes or bands placed on the two first permanent molars5 is especially indicated to resolve maxillary and mandibular incisor crowding in the mixed dentition.5,6

Currently, clear aligners are an option for resolving incisor crowding during the mixed dentition. Previous studies have shown that aligners were adequate for the correction of anterior crowding in the permanent and mixed dentition, with predictability rates of 48.7% to 61.1%.7–11 There is agreement among recent studies that the evidence reporting on clear aligners in children remains scarce, indicating that more clinical trials are still needed.9–11

Previous studies recommended clear aligner use during the mixed dentition only for mild to moderate malocclusions.9–11 Applicability for treating anterior crowding in children is still questionable because of the high dependence of clear aligner success on compliance. No previous studies have compared the treatment outcomes between clear aligners and 2 × 4 mechanics in the mixed dentition. The purpose of this study was to evaluate and compare the efficacy and efficiency between fixed appliances and clear aligners for resolving maxillary incisor irregularity in the mixed dentition. The null hypothesis was that both orthodontic appliances would have similar outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Collection

The present study was a single-center, randomized clinical trial with two parallel arms in a 1:1 allocation ratio. The protocol of this study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials12 and was registered in the Registro Brasileiro de Ensaios Clinicos (Brazilian Register Center of Clinical Trials) under the RBR-9kvw9t identification. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Institutional Board of Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo (process number 14962119.2.0000.5417) before trial commencement.

This study was conducted from 2019 to 2020, and recruitment occurred at the Orthodontic Clinic of Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo. The eligibility criteria included patients of both sexes from 7 to 11 years of age, in the mixed dentition with permanent incisors and first molars completely erupted, and with Little's Irregularity Index in the maxillary arch of at least 3 mm. Patients with incisor agenesis, white spot lesions, cleft lip and palate, and syndromes were excluded. Participants who met the eligibility criteria were invited to participate, and informed consent was obtained from all volunteers and legal guardians.

Interventions

The patients treated with clear aligners were allocated to the clear aligner group (CA). Pretreatment maxillary dental models were scanned using a 3Shape Scanner (3Shape A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark) and prepared for digital setup. Digital setup was performed using MAESTRO3D (AGE Solutions, Pisa, Italy) by the same operator (Dr Merino da Silva). The software automatically generated the number of aligners necessary to reach the final predictive model considering a maximum change of 0.1 mm per aligner for mesial or distal, buccal or lingual, and intrusion or extrusion movements and a maximum of two degrees for rotation, tip, and torque movements. An overcorrection of 20% for each movement was applied. Attachments were planned for all movements except in the buccal direction. Attachment architecture was standardized with a 0.8-mm depth through the MAESTRO3D software with a triangular format, positioning the ramp to guide the movements. In regions with recent deciduous molar exfoliation, a negative space was digitally created to allow for premolar eruption without interfering with retention of the appliance. The digital models generated by the software were printed using a Moonray S100 3D printer (Sprintray, Los Angeles, Calif). Clear aligners were fabricated using a 0.75-mm biocompatible thermoplastic transparent sheet composed of PET-G (Bio-art, São Carlos, Brazil) using a vacuum-forming machine (Bio-art). The aligners were replaced every 15 days, and patients were instructed to wear the clear aligners 20 h/d.13 Orthodontic appointments were scheduled every month.

The patients treated with fixed appliances were assigned to the fixed appliance group (FA) using “two by four” (2 × 4) mechanics in the maxillary arch. Preadjusted metal brackets (Morelli, São Paulo, Brazil) were bonded to all permanent incisors, and orthodontic buccal tubes were bonded to the maxillary permanent first molars. On the maxillary lateral incisors, the right and left brackets were switched to maintain the natural distal angulation observed in the mixed dentition phase. The arch wire sequence was 0.014 and 0.016-inch nickel-titanium and 0.016, 0.018, and 0.020-inch stainless steel. Oral hygiene and dietary instructions were provided to both groups.

All patients from both groups received 7 mm of rapid maxillary expansion before treatment (T1) because of the presence of unilateral/bilateral posterior crossbites. T1 dental models were taken 6 months after RME when the expander was removed. Clear aligners/2 × 4 mechanics started immediately after T1. Digital dental models were obtained at T1 and after appliance removal (T2). All digital dental models were saved in .stl file format.

Evaluations

Blinding was not possible because the operator and patients were aware of the type of appliance used in each case. Outcome assessment was blinded. The primary outcomes were maxillary incisor irregularity index and treatment time. Secondary outcomes included arch width, perimeter, length, size and shape, incisor leveling (incisor step), incisor mesiodistal angulation, plaque index, and International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) index.

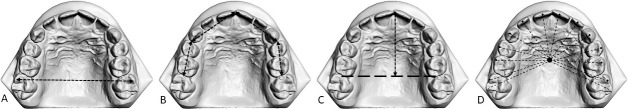

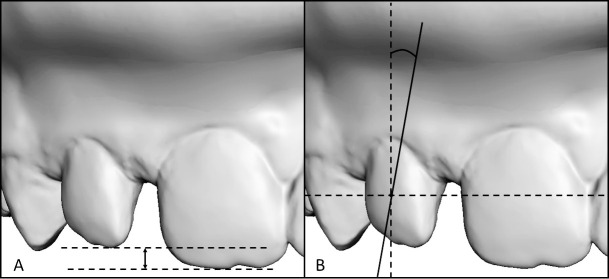

The incisor irregularity index and arch width, perimeter, and length were measured with OrthoAnalyzer software (3Shape A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark) (Figure 1). Maxillary dental arch size and shape were assessed using Stratovan Checkpoint (Stratovan Corporation, Davis, Calif) and MorphoJ (Klingenberg Lab, Manchester, UK) software. A total of 14 landmarks on the occlusal surface of the maxillary teeth were used to access arch measurements on the T1 and T2 digital dental models (Figure 1D).14,15 Maxillary incisor leveling and mesiodistal angulation were assessed using 3DSlicer software (www.slicer.org) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Assessment of maxillary arch dimension. (A) Arch width was measured at the level of the cusp tips of the first permanent molars. (B) Arch perimeter was the sum of the four segments from the mesial aspect of the right first permanent molar to the mesial aspect of the contralateral tooth. (C) Arch length was measured on the horizontal plane from the mesial aspect of the first permanent molars to the mesial edge of the right permanent incisor. (D) A total of 14 landmarks were selected on the cusp tips and incisal edges of the maxillary teeth to provide raw coordinates to evaluate dental arch shape and size. The dental arch size was automatically calculated using the centroid size method in the MorphoJ software (the square root of the sum of the squared distances between the arch centroid to all landmarks).

Figure 2.

Analyses using the vertical plane (occlusal plane) as a reference. (A) Incisor leveling (incisor step) was measured as the distance between the most incisal point of the lateral incisal edge to the same point on the central incisor on each side (right and left); a +0.5-mm step is indicative of an adequate relationship between the central and lateral incisors. (B) Incisor mesiodistal angulation was calculated using a frontal image of each patient's digital casts oriented parallel to the occlusal plane; the angle was measured using the center point of the clinical crown on the central and lateral incisors. A positive sign indicates a mesial tip.

The labial surfaces of the maxillary incisors were assessed for noncavitated carious lesions (white spot lesions) using the ICDAS index. Plaque index was assessed using color-based plaque staining.

Sample Size Calculation

The maxillary incisor irregularity index was selected for sample size calculation. Considering a test power of 80%, an α of 5%, a standard deviation (SD) of 2.6 mm from a preliminary group of the first five patients, and a minimum difference to be detected of 3 mm, a minimum sample of 13 patients in each group was required. Considering 20% of dropouts, 32 patients were randomly assigned.

Randomization

Stratified block randomization16 was performed considering the ascending order of maxillary incisor irregularity index at T1. In pairs, with a 1:1 proportion, a coin-tossing method randomly assigned the patients to the different sample groups.

Statistical Analysis

All measurements were performed by the same observer (Dr Merino da Silva). Of the sample, 50% was reevaluated after a minimum 15-day interval. The intraexaminer error was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs).17 Reproducibility of the ICDAS index was evaluated using a κ score.

Intergroup initial age and sex ratio at baseline were analyzed using tests t-tests and χ2 tests, respectively. Normal distribution was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk tests. Intergroup comparisons were evaluated with t-tests or Mann-Whitney U-tests with Holm-Bonferroni correction. The significance level was 5%. All statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot for Windows version 12.0 (Systat Software Inc., Chicago, Ill).

RESULTS

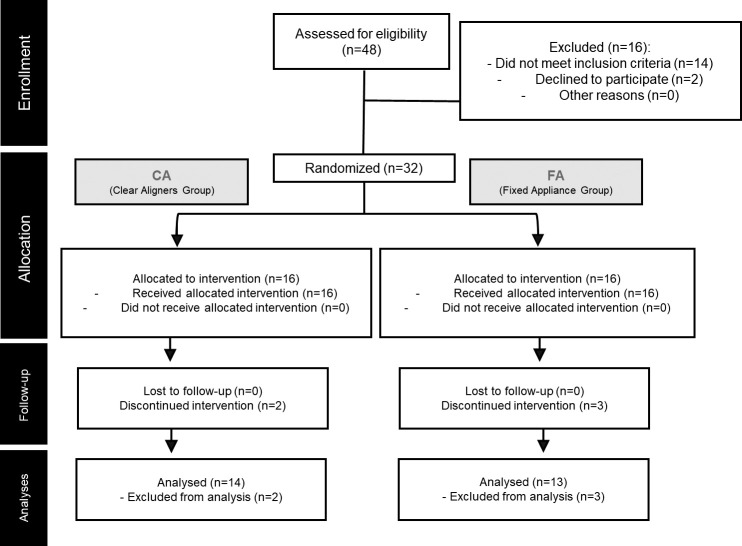

A total of 48 volunteers were evaluated for participation; 14 did not meet the inclusion criteria, and two declined to participate (Figure 3). A total of 32 patients were enrolled at the study commencement. During follow-up, two patients from CA and three from FA terminated treatment because of the coronavirus pandemic. A total of 27 patients completed treatment and were included in the analyses (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Participant flowchart.

Baseline characteristics were similar in both groups (Table 1). All variables showed normal distribution except arch width and incisor step.

Table 1.

Intergroup Comparisons at Baselinea

| Variables |

CA (n = 14) | FA (n = 13) |

P Value |

| Mean (SD), n (%), or Median (Q1/Q3) |

Mean (SD), n (%), or Median (Q1/Q3) |

||

| Initial age, y | 9.33 (1.01) | 9.65 (0.80) | .322b |

| Male | 6 (42.8%) | 9 (69.2%) | .981c |

| Female | 8 (57.1%) | 4 (30.7%) | |

| Little Irregularity Index | 8.29 (2.73) | 8.52 (2.73) | .830b |

| Arch width | 51.90 (50.20/52.70) | 51.63 (49.81/53.86) | 1.000d |

| Arch perimeter | 78.38 (4.03) | 77.55 (3.46) | .569b |

| Arch length | 29.84 (2.64) | 29.15 (1.35) | .408b |

| Arch size | 87.10 (3.82) | 87.60 (4.30) | .782b |

| Central incisor angulation | 0.20 (3.64) | 0.32 (3.16) | .926b |

| Lateral incisor angulation | −7.22 (5.11) | −8.32 (6.66) | .637b |

| Right incisor step | 1.55 (0.98) | 1.07 (0.7) | .154b |

| Left incisor step | 1.37 (0.82/2.14) | 0.57 (0.30/1.66) | .216d |

| Plaque index (%) | 12.50 (0.00/50.00) | 50.00 (25.00/100.00) | .057d |

| ICDAS | 0.00 (0.00/0.00) | 0.00 (0.00/0.00) | 1.000d |

Q1 indicates first quartile; Q3, third quartile. P < .05.

t-test.

χ2 test.

Mann-Whitney U-test.

CA comprised 14 patients (6 girls, 8 boys) with a mean age of 9.33 years (SD = 1.01). FA comprised 13 patients (9 girls, 4 boys) with a mean initial age of 9.65 years (SD = 0.80).

Measurement error evaluation showed good intraexaminer reproducibility for all variables, with ICCs varying from 0.75 to 0.9.18 The κ score for the ICDAS index was strong (≥0.9).

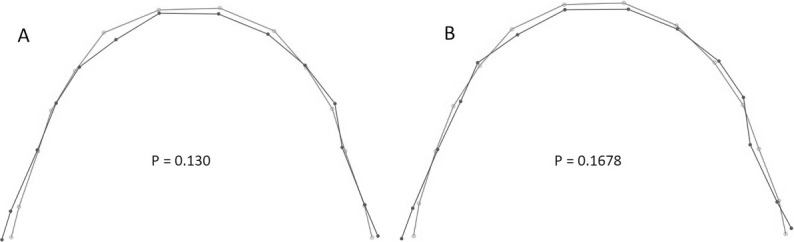

All changes from T1 to T2 showed normal distribution except incisor step and lateral incisor angulation (Table 2). No significant intergroup difference was found for any of the changes in the variables assessed in the study (Table 2 and Figure 4).

Table 2.

Intergroup Comparisons for Treatment Changesa

| Variables |

CA (n = 14) | FA (n = 13) |

P Value |

Holm-Bonferroni (P Value) |

| Mean (SD) or Median (Q1/Q3) |

Mean (SD) or Median (Q1/Q3) |

|||

| Treatment time (months) | 8.00 (2.90) | 8.69 (2.65) | .525b | .010 |

| Little Irregularity Index (mm) | −5.84 (2.92) | −5.15 (2.75) | .536b | .016 |

| Arch width (mm) | 0.20 (0.7) | 0.98 (1.19) | .048b | .005 |

| Arch perimeter (mm) | −1.44 (1.35) | −2.21 (1.65) | .196b | .007 |

| Arch length (mm) | 0.03 (0.93) | −1.18 (1.16) | .006b | .004 |

| Arch size (mm) | 0.01 (1.74) | 0.12 (1.28) | .865b | .025 |

| Central incisor angulation (°) | 0.26 (3.45) | 0.04 (3.62) | .873b | .050 |

| Lateral incisor angulation (°) | 2.85 (0.84/7.49) | −0.67 (−2.79/0.93) | .027c | .004 |

| Right incisor step (mm) | −0.65 (0.04/1.22) | −0.20 (−0.40/1.09) | .157c | .006 |

| Left incisor step (mm) | −0.55 (0.07/0.99) | 0.02 (−0.24/1.03) | .297c | .008 |

| Plaque index (%) | 17.85 (31.66) | −10.00 (44.11) | .063b | .005 |

| ICDAS | 0.00 (0.00/0.50) | 0.00 (0.00/0.50) | .531c | .012 |

P < .05; Holm-Bonferroni correction was applied.

t-test.

Mann-Whitney U-test.

Figure 4.

Superimpositions of maxillary dental arch shape before and after treatment. (A) Pretreatment maxillary dental arch in CA (gray line) and in FA (black line). (B) Posttreatment maxillary dental arch in CA (gray line) and in FA (black line).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have compared fixed orthodontic appliances with clear aligners in the permanent dentition with conflicting results regarding effectiveness, predictability of movement, and treatment time.19–22 In the current study, baseline comparisons confirmed the homogeneity of the sample, reducing the risk of bias for intergroup comparisons (Table 1).23

The initial irregularity index of the maxillary anterior teeth of both groups was moderate to severe. Previous studies considered an incisor irregularity index greater than 5 as severe incisor irregularity.24,25 Both clear aligners and 2 × 4 mechanics produced a decrease of 5 mm in the maxillary incisor irregularity index; the efficacy of both appliances was similar. A previous study comparing clear aligners and comprehensive fixed appliances in the permanent dentition also reported that both were adequate to correct slight to moderate crowding.8

Treatment time for resolving the maxillary incisor crowding was similar with both appliances (Table 2). The 2 × 4 fixed appliances used five different arch wires with monthly changes. Some were maintained more than 1 month for severe incisor rotations, and, in addition, bracket failures occurred in all 14 patients. Previous studies reported a treatment time for 2 × 4 fixed appliances from 5 to 13 months.26–28 In contrast to the findings of the current study, a recent study reported that treatment with clear aligners took 4.8 months longer than fixed appliances to obtain the same quality of results in adult patients.29

In CA, a mean of 10 aligners in the treatment phase and 6 aligners in the refinement phase was planned. Considering that the aligners were replaced every 15 days, a treatment time close to 8 months was expected. The movement most commonly needed during refinement was rotation. Some previous studies also showed similarity in treatment times between clear aligners and fixed appliances in the permanent dentition.19,22 Conversely, other studies demonstrated shorter treatment times for clear aligners20 and for fixed appliances.21

To provide a visual representation of the treatment changes in the dental arch shape, an evaluation based on the centroid size and location was performed.14,30,31 Slight changes were noticed for the secondary outcomes in both groups without intergroup differences (Table 2). The arch perimeter decrease in both groups might have been attributed to natural changes in the late mixed dentition, such as mesial movement of the maxillary molars into the Leeway space.32 Previous studies in adults showed that clear aligners can increase arch width in cases with mild to moderate crowding.10,11,33,34

The distal angulation of the maxillary lateral incisors was maintained in FA, whereas a slight mesial tip was observed in CA. The better control of lateral incisor angulation with fixed 2 × 4 mechanics was probably attributed to passive bonding of the lateral incisor brackets. In contrast, clear aligners increased mesial angulation of the lateral incisors during treatment. Previous studies demonstrated that aligners were not able to control undesired dental inclination throughout treatment, showing that fixed appliances are better indicated for root control.34,35

Steps between the incisal edges of the central and lateral maxillary incisors are recommended for adequate smile esthetics.36 Both groups had a final (T2) mean step of 0.79 mm between the central and lateral incisors in agreement with previous studies.36 Extrusion and intrusion are difficult movements to achieve with clear aligners. Previous studies reported true extrusion/intrusion ranging from 0.72 to 1.50 mm with aligners, which should have been enough in the mixed dentition for adequate leveling of the maxillary incisiors.8,37,38

Previous studies showed that adolescents demonstrated greater compliance rates with oral hygiene when treated with clear aligners.39 Despite hygiene guidance and adequate follow-up, white spot lesions were observed in both groups after treatment. The increase in white spot lesions in both groups was in agreement with a previous study in adult patients showing that both fixed and removable appliances were capable of causing white spot lesions.40

Considering the similarities in the primary and secondary outcomes found between clear aligners and 2 × 4 fixed appliances in this study, appliance choice should be guided by clinician and family preferences.

CONCLUSIONS

Clear aligners and fixed 2 × 4 mechanics showed similar efficacy and efficiency for the correction of maxillary incisor crowding in the mixed dentition.

Both appliances showed similar dental plaque index and white spot lesion incidence during treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) (grant 2017/24115-2) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) (grant 88887.356781/2019-00). This article is based on research submitted by Dr Vinicius Merino da Silva in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MSc in Orthodontics at Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo. The authors thank Bauru Dental School, University of São Paulo for their support. Clinical trial registration: Registro Brasileiro de Ensaios Clínicos (Brazilian Register Center of Clinical Trials) ReBEC-RBR-9kvw9t; date of register: April 6, 2020.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) (grant 2017/24115-2) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) (grant 88887.356781/2019-00).

REFERENCES

- 1.Dimberg L, Lennartsson B, Arnrup K, Bondemark L. Prevalence and change of malocclusions from primary to early permanent dentition: a longitudinal study. Angle Orthod . 2015;85(5):728–734. doi: 10.2319/080414-542.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tschill P, Bacon W, Sonko A. Malocclusion in the deciduous dentition of Caucasian children. Eur J Orthod . 1997;19(4):361–367. doi: 10.1093/ejo/19.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kragt L, Dhamo B, Wolvius EB, Ongkosuwito EM. The impact of malocclusions on oral health-related quality of life in children—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig . 2016;20(8):1881–1894. doi: 10.1007/s00784-015-1681-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Góis EG, Vale MP, Paiva SM, Abreu MH, Serra-Negra JM, Pordeus IA. Incidence of malocclusion between primary and mixed dentitions among Brazilian children: a 5-year longitudinal study. Angle Orthod . 2012;82(3):495–500. doi: 10.2319/033011-230.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isaacson RJ, Lindauer SJ, Rubenstein LK. Activating a 2 × 4 appliance. Angle Orthod . 1993;63(1):17–24. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1993)063<0017:AAA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowsing P, Sandler P. How to effectively use a 2 × 4 appliance. J Orthod . 2004;31(3):248–258. doi: 10.1179/146531204225020541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haouili N, Kravitz ND, Vaid NR, Ferguson DJ, Makki L. Has Invisalign improved? A prospective follow-up study on the efficacy of tooth movement with Invisalign. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop . 2020;158(3):420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieger E, Seiferth J, Marinello I, et al. Invisalign® treatment in the anterior region. J Orofac Orthop . 2012;73(5):365–376. doi: 10.1007/s00056-012-0097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorton J, Bekmezian S, Mah JK. Mixed-dentition treatment with clear aligners and vibratory technology. J Clin Orthod . 2020;54(4):208–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lione R, Paoloni V, Meuli S, Pavoni C, Cozza P. Upper arch dimensional changes with clear aligners in the early mixed dentition a prospective study. J Orofac Orthop . [published online ahead of print September 3, 2021] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Levrini L, Carganico A, Abbate L. Maxillary expansion with clear aligners in the mixed dentition: a preliminary study with Invisalign® First system. Eur J Paediatr Dent . 2021;22(2):125–128. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2021.22.02.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT. 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med . 2010;152(11):726–732. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Nadawi M, Kravitz ND, Hansa I, Makki L, Ferguson DJ, Vaid NR. Effect of clear aligner wear protocol on the efficacy of tooth movement: a randomized clinical trial. Angle Orthod . 2021;91(2):157–163. doi: 10.2319/071520-630.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pugliese F, Palomo JM, Calil LR. de Medeiros Alves A, Lauris JRP, Garib D. Dental arch size and shape after maxillary expansion in bilateral complete cleft palate: a comparison of three expander designs. Angle Orthod . 2020;90(2):233–238. doi: 10.2319/020219-74.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massaro C, Janson G, Miranda F, et al. Dental arch changes comparison between expander with differential opening and fan-type expander: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthod . 2021;43(3):265–273. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjaa050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandis N. Randomization. Part 1: sequence generation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop . 2011;140(5):747–748. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleiss JL. Analysis of data from multiclinic trials. Control Clin Trials . 1986;7(4):267–275. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med . 2016;15(2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Djeu G, Shelton C, Maganzini A. Outcome assessment of Invisalign and traditional orthodontic treatment compared with the American Board of Orthodontics objective grading system. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop . 2005;128(3):292–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuncio D, Maganzini A, Shelton C, Freeman K. Invisalign and traditional orthodontic treatment postretention outcomes compared using the American Board of Orthodontics objective grading system. Angle Orthod . 2007;77(5):864–869. doi: 10.2319/100106-398.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li W, Wang S, Zhang Y. The effectiveness of the Invisalign appliance in extraction cases using the ABO model grading system: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Int J Clin Exp Med . 2015;8(5):8276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 22.Pavoni C, Lione R, Laganà G, Cozza P. Self-ligating versus Invisalign: analysis of dento-alveolar effects. Ann Stomatol . 2011;2(1–2):23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berger VW, Exner DV. Detecting selection bias in randomized clinical trials. Control Clin Trials . 1999;20(4):319–327. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(99)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little RM. The irregularity index: a quantitative score of mandibular anterior alignment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop . 1975;68(5):554–563. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(75)90086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kau CH, Durning P, Richmond S, Miotti F, Harzer W. Extractions as a form of interception in the developing dentition: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthod . 2004;31(2):107–114. doi: 10.1179/146531204225020391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sockalingam S, Zakaria ASI, Khan KAM, Azmi FM, Noor NM. Simple orthodontic correction of rotated malpositioned teeth using sectional wire and orthodontic appliances in mixed-dentition: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dent 2020; 30; 2020:6972196. doi: 10.1155/2020/6972196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singhal P, Namdev R, Jindal A, Bodh M, Dutta S. A multifaceted approach through two by four appliances for various malocclusions in mixed dentition Clin Dent. 9(4)14–19. 2015.

- 28.Gu Y, Rabie AB, Hägg U. Treatment effects of simple fixed appliance and reverse headgear in correction of anterior crossbites. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop . 2000;117(6):691–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin E, Julien K, Kesterke M, Buschang PH. Differences in finished case quality between Invisalign and traditional fixed appliances: a randomized controlled trial. Angle Orthod . 2022;92(2):173–179. doi: 10.2319/032921-246.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klingenberg CP. Size, shape, and form: concepts of allometry in geometric morphometrics. Dev Genes Evol . 2016;226(3):113–137. doi: 10.1007/s00427-016-0539-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webster M, Sheets HD. A practical introduction to landmark-based geometric morphometrics. The Paleontological Society Papers . 2010;16:163–188. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moorrees CF. The Dentition of the Growing Child Vol 1959 Cambridge MA Harvard University Press; 1959.

- 33.Duncan LO, Piedade L, Lekic M, Cunha RS, Wiltshire WA. Changes in mandibular incisor position and arch form resulting from Invisalign correction of the crowded dentition treated nonextraction. Angle Orthod . 2016;86(4):577–583. doi: 10.2319/042415-280.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grünheid T, Gaalaas S, Hamdan H, Larson BE. Effect of clear aligner therapy on the buccolingual inclination of mandibular canines and the intercanine distance. Angle Orthod . 2016;86(1):10–16. doi: 10.2319/012615-59.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drake CT, McGorray SP, Dolce C, Nair M, Wheeler TT. Orthodontic tooth movement with clear aligners. ISRN Dent . 2012;2012:657973. doi: 10.5402/2012/657973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Machado AW. 10 commandments of smile esthetics. Dental Press J Orthod . 2014;19(4):136–157. doi: 10.1590/2176-9451.19.4.136-157.sar. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu J, Tang JS, Skulski B, et al. Evaluation of Invisalign treatment effectiveness and efficiency compared with conventional fixed appliances using the Peer Assessment Rating index. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop . 2017;151(2):259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khosravi R, Cohanim B, Hujoel P, et al. Management of overbite with the Invisalign appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop . 2017;151(4):691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.09.022. e692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abbate GM, Caria MP, Montanari P, et al. Periodontal health in teenagers treated with removable aligners and fixed orthodontic appliances. J Orofac Orthop . 2015;76(3):240–250. doi: 10.1007/s00056-015-0285-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albhaisi Z, Al-Khateeb SN, Abu Alhaija ES. Enamel demineralization during clear aligner orthodontic treatment compared with fixed appliance therapy, evaluated with quantitative light-induced fluorescence: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop . 2020;157(5):594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]