Abstract

Epithelial tissues comprise heterogeneous cellular subpopulations, which often compartmentalize specialized functions such as absorption and secretion to distinct cell types. In the liver, hepatocytes and biliary epithelial cells (BECs; also called cholangiocytes) are the 2 major epithelial lineages and play distinct roles in (1) metabolism, protein synthesis, detoxification; and (2) bile transport and modification, respectively. Recent technological advances, including single-cell transcriptomic assays, have shed new light on well-established heterogeneity among hepatocytes, endothelial cells, and immune cells in the liver. However, a “ground truth” understanding of molecular heterogeneity in BECs has remained elusive, and the field currently lacks a set of consensus biomarkers for identifying BEC subpopulations. Here, we review long-standing definitions of BEC heterogeneity as well as emerging studies that aim to characterize BEC subpopulations using next-generation single-cell assays. Understanding cellular heterogeneity in the intrahepatic bile ducts holds promise for expanding our foundational mechanistic knowledge of BECs during homeostasis and disease.

Keywords: Cellular heterogeneity, Cholangiocyte, Intrahepatic bile ducts, Liver, Single cell biology

Introduction

Cellular heterogeneity supports tissue function in homeostasis and provides tissues with the ability to adapt to environmental challenges. The gastrointestinal (GI) tract holds many well-defined examples of cell type–specific functions that aid in digestion and homeostasis. Well-characterized intestinal epithelial cells demonstrate specialized functions spanning absorption of nutrients to secretion of hormones, mucus, or antimicrobial peptides.1 Epithelial heterogeneity also varies regionally along the small intestine and colon and appears to be at least partially cell autonomous, with cells maintaining their identity when transplanted from the small intestine to the colon.2 Pancreatic beta cells provide another example of GI epithelial heterogeneity, with subpopulations responding to different thresholds of glucose, exhibiting varied gap junction expression patterns, and demonstrating differential proliferative capacity.3 In both intestinal epithelial cells and pancreatic beta cells, recent single-cell transcriptomic studies have identified previously unappreciated heterogeneity, generating exciting new insight on GI epithelial function.4, 5, 6 Refining models of cellular heterogeneity and regulation of cellular identity can provide foundational mechanistic understanding of tissue function and may help identify cellular and molecular targets for novel therapeutics.

Hepatocytes and BECs represent the 2 epithelial lineages of the liver. Hepatocytes make up ∼80% of the liver by weight and are responsible for a variety of functions, including glucose metabolism, detoxifying exogenous compounds, and bile salt secretion.7 BECs are polarized epithelial cells that line the biliary tree and are responsible for regulating net bile volume, modifying bile, and maintaining bile alkalinity.8 BECs represent only 3%–5% of the liver by mass but can produce up to 40% of daily bile output volume.9 Although normally quiescent, BECs demonstrate extensive remodeling and proliferation after liver injury in a process called “ductular reaction.”10, 11, 12 Although BECs of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tree share many biomarkers and make up a continuous ductal network, these cells have distinct embryologic origins.13,14 In this review, we focus on BEC heterogeneity in the intrahepatic bile ducts (IHBDs).

Hepatocyte heterogeneity during homeostasis is well defined in relation to hepatocyte zonation, which refers to the functional compartmentalization of specific metabolic processes in the liver that is regulated through signaling gradients.15, 16, 17 In contrast, classical definitions of BEC heterogeneity have focused on morphologic characteristics rather than molecular heterogeneity. The recent use of novel biomarkers and emerging single-cell technologies has characterized the molecular identity of individual BECs and shed new light on cellular subpopulations of the IHBDs. These studies support the existence of multiple BEC subpopulations with distinct morphologic, functional, and molecular properties.

Bile Duct Anatomy

BECs line the bile ducts that, collectively, form the biliary tree. The biliary tree is subdivided into extrahepatic bile ducts (EHBDs) and IHBDs. In humans, EHBDs are composed of the common hepatic duct, cystic duct, common bile duct, main pancreatic duct, and the ampulla of Vater. Human IHBDs consist of hepatic ducts (>800 μm diameter), segmental ducts (400–800 μm diameter), area ducts (300–400 μm diameter), septal ducts (100 μm diameter), interlobular ducts (15–100 μm diameter), and bile ductules (<15 μm diameter).18, 19, 20 These ducts can be grouped by duct diameter into small and large ducts.21, 22, 23, 24 Small ducts consist of septal ducts, interlobular ducts, and bile ductules, whereas large ducts consist of area, segmental, and hepatic ducts. Although they lack the exact structural complexity observed in human IHBDs, rodent IHBDs mimic this variation in size with large (rat: >15 μm diameter) and small ducts (rat: <15 μm diameter).21,25 Human and rat EHBDs and IHBDs also contain peribiliary glands (PBGs), which are small invaginations along the bile ducts that secrete mucus and other compounds.26 PBGs are thought to serve as niches for immature BECs, as they exhibit a hyperproliferative response to injury and can give rise to biliary tract cancers.27, 28, 29, 30 Although mice have well-characterized PBGs along the EHBD, PBGs have not been characterized in mouse IHBDs.31,32

IHBDs play an important role in modifying primary canalicular bile produced by hepatocytes and funneling bile into the EHBDs. BECs perform secretory and absorptive functions, which adjust bile flow and alkalinity to meet physiological needs. When bile removal is seriously altered in the context of cholestatic liver injury or disease, progressive cirrhosis can occur and lead to liver failure. Cholangiopathies, liver diseases that directly impact BECs, account for additional morbidity and mortality, given their progressive nature and lack of effective medical therapies.33 Some cholangiopathies can affect the bile ducts heterogeneously. For example, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) varies in etiology, with most cases affecting large ducts and a subset of cases affecting small ducts (∼10%).34 Small-duct PSC is associated with better long-term outcomes compared with large-duct PSC.35, 36, 37 In a minority of PSC cases, both small and large ducts are affected.35 In contrast, primary biliary cholangitis is an autoimmune disorder resulting in progressive IHBD destruction specific to small ducts.27,38 The heterogeneous nature of primary biliary cholangitis and PSC demonstrates the need for an improved understanding of IHBD heterogeneity and how this heterogeneity promotes proper duct function.

Comparative Anatomy of Model Organisms for Studying IHBD

Standard animal models for studying IHBDs are zebrafish, rats, and mice. The existence of distinct liver lobes, referred to as lobation, is a common structural variation between species (Table 1). Zebrafish have bilobated livers (dorsal and ventral lobes), whereas mouse and rat livers consist of median, left, right, and caudate lobes (Table 1).46,58 Generally, liver size and lobation are influenced by organism size, with smaller mammals presenting lobated livers (ie, mice, rats, and cats) and larger mammals possessing nonlobated livers (ie, humans, dolphins, and cattle).39 In mammals, the hepatic artery, portal veins, and bile ducts are organized into a portal triad, with hepatocyte plates (also known as chords) extending away from the triad. Mammals, including humans, rats, and mice, have conserved IHBD development. Hepatic progenitor cells, called hepatoblasts, give rise to hepatocytes and BECs through asymmetric specification.59 During biliary tubulogenesis, early BECs align around the portal vein to form a single-layered ring termed the ductal plate. Portions of the ductal plate become a bilayer and form expanding luminal structures, which give rise to bile ducts.60, 61, 62, 63 BEC specification from hepatoblasts is promoted by several pathways, including Notch, transforming growth factor beta, and Hippo, which may also play roles in regulating BEC heterogeneity.41,47,63,64

Table 1.

Comparative Liver Anatomy Across Commonly Used Models of Intrahepatic Biliary Biology

| Zebrafish |

Rat |

Mouse |

Human |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Citations | |

| Lobation | Bilobated; Dorsal lobe (DL) and ventral lobe (VL) | Lobated; Left lobe (LL), median lobe (ML), right lobe (RL), caudate lobe (CL) | Lobated; Left lobe (LL), median lobe (ML), right lobe (RL), caudate lobe (CL) | Not lobated; However, the human liver is described in segments of left, right, and caudate (not shown) lobes | 39,40 |

| Gallbladder (G) | Present | Absent | Present | Present | 41,42 |

| Hepatocyte zonation | Absent | Present | Present | Present | 46 |

| Lobule organization |  |

|

40,43, 44, 45 | ||

| Portal triad | Absent; bile ducts intermittently dispersed | Present | Present | Present | (Same as above) |

| Hepatic artery | Poorly identified/unidentified | Present | Present | Present | 45 |

| Intrahepatic bile duct heterogeneity studies | • Small and large ducts | • Small and large ducts | • Small and large ducts | • Small and large ducts | 21,23,47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 |

| • scRNA-seq | • scRNA-seq | • Proliferation preference(clonal assays) | • scRNA-seq | ||

| • Small and large BECs | • ST14 and Sox9EGFP high and low subpopulations | • snRNA-seq | |||

| • scRNA-seq | |||||

Although rat liver development is very similar to mouse and human liver development, rats do not develop a gallbladder or cystic duct due likely to a lack of Sox17 in the biliary bud (Table 1).42 In teleosts, including zebrafish, there is no evidence of a ductal plate.43 Instead, BECs first appear near the EHBD and expand to the rest of the liver.40 Resulting from these developmental differences, zebrafish lack portal triads and instead have bile ducts dispersed throughout the liver lobule (Table 1). These luminal structures gradually enlarge in size, eventually joining larger ducts, which carry bile to the common bile duct.44 To date, there is no evidence of a hepatic artery in zebrafish, although some studies have described small hepatic artery radicles.44,45,65 Zebrafish BEC heterogeneity remains the least well characterized among common animal models of liver biology but has been studied morphologically (small and large ducts) and, recently, through single-cell RNA (scRNA)-seq (Table 1).48,66

Although zebrafish have substantial structural differences in duct organization relative to mammals, they present some technical advantages for modeling IHBD development. As zebrafish embryos are transparent, ductal development can be observed easily using whole mount brightfield microscopy or fluorescent microscopy to visualize transgenic reporters.65 Zebrafish also develop quickly, with the first BECs appearing at 50–60 hours postfertilization and duct-like structures forming 70 hours postfertilization.44 Critical BEC developmental gene expression such as NOTCH activation and the expression of Hnf6, Sox9 (sox9b in zebrafish), and Onecut3 is conserved in all vertebrates, including zebrafish.44,67 Transparency, quick gestation time, high fecundity, and conserved developmental genetics allow zebrafish to be a useful tool in unraveling the importance and molecular regulation of BEC heterogeneity in addition to studying liver development and liver disease mechanisms.

Although zebrafish are a useful model, mice and rats are advantageous in that rodent liver development and organization is largely similar to humans. However, due to the expression of Cyp2c70, which converts chenodeoxycholic acid to 6-hydroxylated muricholic acids by 6-hydroxylation, rodent bile is more hydrophilic than human bile.68,69 The differences in bile acid (BA) composition between rodents and humans may be important to consider when comparing differences in human and rodent BEC heterogeneity, especially if aspects of cell-cell heterogeneity are impacted by BA signaling. In rodents, many well-established injury models and transgenic mouse lines facilitate assays of liver homeostasis and repair and simplify genetic manipulation.70, 71, 72 Techniques for producing organoids from ductal fragments or single BECs have been well characterized in mice, rats, and patient samples.73,74 Ductal organoids are complementary systems to in vivo studies of bile duct development, disease, and heterogeneity and are amenable to genetic manipulation and drug screening. To study BEC heterogeneity, single-cell organoids can be grown in culture to determine differences in proliferation, survival, and responses to exogenous factors introduced into the culture system.49 Although BEC organoids are still evolving as a model system, they are likely to prove useful in unraveling mechanisms regulating BEC heterogeneity.

Classical Definitions of BEC Morphologic Heterogeneity

Intrahepatic BEC heterogeneity was first described in the context of duct size.21, 22, 23, 24 BECs that line small ducts were observed to be significantly smaller and less columnar than BECs that line large ducts (Table 2). This led to the classification of BECs as “small” or “large,” corresponding to the relative diameter of the resident duct as well as the area of the BECs themselves.18,26 Small BECs have also been characterized as having a high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, whereas large BECs exhibit a more extensive cytoplasm.26

Table 2.

Defining Characteristics Between Rat Small and Large Intrahepatic Bile Ducts

| Small IHBDs | Large IHBDs | Citations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duct diameter | <15 μm | >15 μm | 75 |

| Cell size | 8.49 ± 0.05 μm | 14.53 ± 0.05 μm | 23 |

| Cilia length | 3.58 ± 1.12 μm | 7.35 ± 1.32 μm | 29,30 |

| Markers | HRH1, NFAT2, and NFAT4 | SCTR(SR), Cl-/HCO3-AE2, CFTR, ASBT, NFAT3, SSTR, MT1, and MT2 | 21,75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90 |

| Proliferation | Regulated by HRH1; proliferate in response to CCl4 | cAMP dependence; HRH2 regulation; proliferate in response to BDL | 76, 77, 78, 79, 80,85,91 |

| Shared markers | KRT19, SPP1(OPN), γ-GT, SOX9, CD326(EpCAM), HNF1 , and HNF6 | 58,89,92 | |

Measurements provided for duct diameter, cell size, and cilia length are from rat IHBDs.

Primary cilium length is another structural difference between small and large BECs. The apical cell membrane of BECs possesses a single primary cilium, which has sensory function and regulates biological activities, such as cell differentiation, proliferation, and secretion.28,29 Small BECs have been reported to have shorter cilia, which are less than half the size of cilia found on large BECs (Table 2; in rats: 3.58 ± 1.12 μm and 7.35 ± 1.32 μm, respectively).29,30 However, there is not a clear consensus in the literature regarding the percentage of BECs, which possess a primary cilium. Some reports describe as few as 43.5 ± 2.0% of BECs possessing primary cilia in rats.93 Another study has detected a similar heterogeneity in mouse BEC cilia, reporting ∼0.3 cilia per duct cell.94 Other studies demonstrate that 80%–100% of BECs possess primary cilia in mice and rats.95,96 Differences in reports of cilia count may be due in part to histologic artifacts, as some cilia could be excluded based on the orientation and thickness of the duct captured in the tissue section. Further examination of primary cilium presence and length may be warranted in future studies characterizing structural heterogeneity among BECs.

Functional Heterogeneity in Small and Large BECs

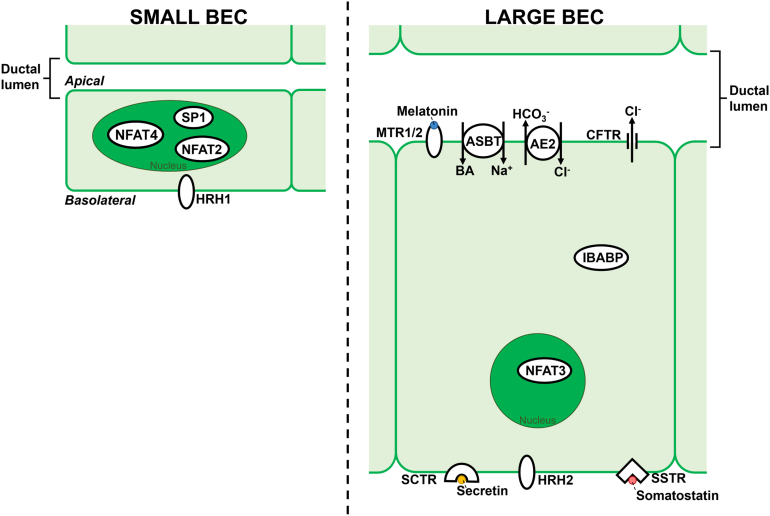

In addition to distinct morphologic characteristics, small and large BECs also exhibit functional differences in terms of how they modify bile. General BEC secretory and absorptive function has been extensively reviewed elsewhere; here, we focus on functional differences between small and large BECs.97 In IHBDs, intracellular calcium (Ca2+) modulates diverse processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, bile alkalization, and secretion of electrolytes and water.98, 99, 100 In BECs, Ca2+ release is regulated predominately by 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3), which binds to InsP3 receptors (InsP3R) to promote Ca2+ release from the ER.98,99 Although both small and large BECs can signal through InsP3Rs, they differ in Ca2+-mobilizing receptors. In small ducts, histamine receptor H1 is found in the basolateral membrane and modulates small BEC proliferation and secretion (Figure).76,77 Small BECs also regulate proliferation by Ca2+-dependent activation of the transcription factors: NFAT2, NFAT4, and SP1 (Figure).78 Similarly, although they have been reported to lack histamine receptor H1, large BECs express HRH2, which has been shown to be a key regulator of large BEC proliferation (Figure).76,77,79,80 Large BECs also have Ca2+-dependent activation of the transcription factor NFAT3.78

Figure.

Heterogeneity within small and large intrahepatic biliary epithelial cells. The apical membrane of each BEC lines the ductal lumen within which melatonin and bile acids, large BEC-specific signaling molecules, are found. Large ducts have a larger diameter in the ductal lumen than small ducts. When compared with small BECs, large BECs are more columnar in morphology and have a reduced nucleus to cytoplasm ratio. In small BECs, NFAT2, NFAT4, and SP1 are transcription factors that localize to the nucleus. Also, in small BECs, HRH1 localizes to the basolateral membrane. Large BECs express MTR1/2, ASBT, AE2, and CFTR on the apical membrane and SCTR, HRH2, and SSTR on the basolateral membrane. AE2, anion exchanger 2; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; SCTR, secretin receptor; SSTR, somatostatin receptor.

Unlike small BECs, large BECs have been reported to be cyclic AMP (cAMP) responsive and regulators of bile flow. Bile flow is controlled by large BEC-specific receptors: cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, Cl−/HCO3− anion exchanger 2, secretin receptor, somatostatin receptor, melatonin receptors (MT1 and MT2), and apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (ASBT). Secretin regulates large BEC bicarbonate (HCO3−) secretion through interaction with the G protein–coupled secretin receptor, resulting in cAMP signaling.24,81 cAMP signaling induces cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, which activates anion exchanger 2 and Ca2+ is released into bile (Figure).23,75,82 Somatostatin acts to counter regulate the stimulatory effects of secretin by binding somatostatin receptor, leading to inhibition of ductal fluid secretion and, in some instances, ductal fluid absorption.79,83, 84, 85, 86, 87 cAMP signaling is also decreased in large BECs by melatonin, which has been shown to suppress BEC proliferation during cholestasis. Melatonin is found in bile (2–3 times higher than in circulation and other bodily fluids) and interacts with large BEC-specific melatonin receptors (MT1 and MT2; Figure).88,89 BA is transported inside BECs by ASBT.90 Once inside the cell, BAs bind the ileal bile acid–binding protein (IBABP). ASBT and IBABP have been reported to be expressed at higher levels in large BECs but are present in small BECs.90 The functional differences between small and large BECs suggest that large ducts may be more important than small ducts in regulating bile flow due to large BEC responsiveness to secretin, somatostatin, melatonin, and BAs.

In addition to heterogeneous mechanisms for mobilizing Ca2+, BECs exhibit functional differences in proliferation rates after injury. Although BECs remain largely quiescent in the normal liver and homeostatic turnover is poorly understood, proliferative heterogeneity of BECs has been studied during injury and regeneration.101 Animal models of ductular reaction rely on a range of established surgical and chemical damage models, often resulting in cholestasis secondary to hepatocyte injury (common damage models are reviewed extensively in a study by Ko et al102). In both mice and rats, bile duct ligation (BDL) reportedly stimulates the proliferation of large—but not small—BECs. These data were obtained by measuring duct size in tissue sections and measuring relative cell size and cell cycle using flow cytometry.21,85 In contrast, IHBD proliferation following carbon tetrachloride feeding in rats occurs primarily in small BECs, as assayed by measuring the number of BECs, which were positive for proliferating cell nuclear antigen in tissue sections.91 Another study found a significant increase in both small and large BEC proliferation following BA feeding in mice, suggesting that this model does not induce a heterogenous proliferative response between small and large ducts.103

Proliferative heterogeneity in BECs has also been assayed using an in vivo clonal labeling technique. Kamimoto et al50 used Prom1CreERT2;R26tdTomato transgenic mice to track proliferation via inducible, BEC-specific recombination and tdTomato expression. By administering a low dose of tamoxifen, BECs were sparsely labeled, allowing the proliferation and clonal expansion of individual BECs to be traced over time. BECs were labeled at a rate of 0.2%, and after 6 weeks of thioacetamide injury, most BECs exhibited no or minimal proliferation. However, rare BEC clones had formed colonies of dozens of cells at the same time point.50 These findings clearly demonstrate that BECs do not proliferate uniformly after damage. The authors also sought to determine if BEC proliferation is anatomically compartmentalized. Rather than using established “small” and “large” duct definitions, the authors defined ductules as <8 μm in diameter and ducts as >8 μm based on anatomical relationships between the IHBDs and portal veins observed by 3-dimensional microscopy.50 The authors reported no large clones of proliferating BECs in the ducts. Instead, large proliferative clones were localized to peripheral ductules.50 These results differ from earlier findings that reported proliferation following BDL to be restricted to large BECs and instead bear similarity to small BEC proliferation following carbon tetrachloride injury in rats. Collectively, these studies suggest that proliferative heterogeneity among BECs is likely influenced by the nature of the damage modality inducing ductular reaction. New and ongoing ductular reaction studies should consider small and large duct heterogeneity so that comparisons can be made to long-standing definitions of biliary heterogeneity.

Genetic Biomarkers for Studying BEC Heterogeneity

Cell type–specific biomarkers have long been advantageous for identifying epithelial subpopulations in other GI tissues and are often related to specialized cellular function. Well-accepted examples include lysozyme expression specific to small intestinal Paneth cells and glutamine synthetase expression specific to pericentral hepatocytes.104,105 Although many studies on small and large BECs have focused on differential expression of specific genes and proteins, these markers are rarely used to identify or describe BEC subpopulations. A potential challenge is that many classic BEC physiology studies used rat tissue or immortalized cell lines, which may not directly translate to mouse models used in more recent genetic studies. In addition, many of the most well-accepted BEC markers, including EPCAM, K19, and SOX9, appear to be expressed ubiquitously throughout IHBDs and are therefore unsuitable for pursuing questions of BEC heterogeneity. Flow cytometry/FACS and 3-dimensional immunofluorescence demonstrate that CD326 reliably labels all cells of the IHBD in mice.49,106, 107, 108, 109, 110 Similarly, SOX9 has been proposed as a marker of immature BECs but is an early transcriptional regulator of BEC specification during development and is expressed in all adult BECs of the IHBDs.49,63,111, 112, 113 SOX9 is also expressed in rare peribiliary hepatocytes (termed “hybrid hepatocytes” or HybHeps) and may promote hepatocyte-to-BEC transdifferentiation during injury and tumorigenesis.49,113, 114, 115

ST14 was identified as a marker of BEC heterogeneity through a targeted screen of potential cell surface markers for cells expressing MIC1-1C3, an oval cell antigen that labels BECs.116 MIC1-1C3+ cells were found to contain ST14lo and ST14hi subpopulations. A clonogenic biliary organoid assay demonstrated that although ST14lo cells could form organoids at P0, only ST14hi cells are capable of efficiently generating organoids that survive for greater than 2 passages.51 Furthermore, RNA-seq of ST14lo vs ST14hi cells identified 899 differentially expressed genes. One such candidate marker of ST14hi cells, Pkhd1l1, was examined by single-molecule FISH (smFISH) and determined to be expressed in a minority of IHBD BECs. Although the study reports that Pkhd1l1+ cells appear dispersed throughout the IHBDs, their localization to small or large ducts was not reported.51

With the advent of transgenic mice, knowledge of biomarkers was leveraged with fluorescent reporters to identify and isolate specific cell populations. The use of Lgr5EGFP mice to identify GI epithelial stem cell populations, first in the small intestine and colon and later in the stomach, is perhaps the most broadly applied example of this strategy.117,118 Of note, although Lgr5 was initially postulated to be expressed in a subpopulation of BECs based on Lgr5EGFP expression and organoid-forming capacity, subsequent studies have failed to identify Lgr5 mRNA in BECs.47,52,119,120 Rather, Lgr5 and Lgr5EGFP appear restricted to hepatocytes, and whether Lgr5+ hepatocytes have a privileged role in liver growth or regeneration remains controversial.121,122

Our laboratory recently applied a Sox9EGFP transgenic mouse model to explore BEC heterogeneity. The Sox9EGFP allele was developed as a part of the GENSAT Project and previously used to isolate distinct intestinal epithelial subpopulations, including stem and progenitor cells.123, 124, 125, 126 Biliary epithelial expression of Sox9 and the EGFP reporter is broad, with all EPCAM+ or K19+ BECs expressing EGFP.49 However, distinct expression levels of the EGFP transgene facilitate identification and isolation of BEC subpopulations. Specifically, EGFPlo and EGFPhi cells represent transcriptomically distinct BEC subpopulations that also demonstrate differential functional characteristics in clonal organoid-forming assays. Although EGFPlo and EGFPhi BECs were found in both small and large IHBDs, smaller ductules were more enriched for EGFPhi BECs. EGFPhi BECs were also significantly smaller in area relative to EGFPlo BECs, further suggesting consistency between this population and small BECs. As expected from the known expression of Sox9 in HybHeps, cells expressing a very low level of the EGFP reporter (termed EGFPsub) were demonstrated to be consistent with peribiliary hepatocytes.49 All EGFP+ populations, including EGFPsub HybHeps, were capable of forming organoids in biliary and hepatocyte organoid conditions. Interestingly, organoids from EGFPsub and EGFPhi populations were more likely to express HNF4A in hepatocyte media conditions.49,127 Although hepatocyte function was not assayed, this may suggest differences in transdifferentiation potential between Sox9EGFP populations. Although the Sox9EGFP allele may aid in dissecting BEC heterogeneity, it is limited in that it requires the presence of a transgenic allele and may not capture the full spectrum of BEC subpopulations.

Transcriptomic Heterogeneity and Emerging Single-Cell Technologies in BEC Biology

The emergence of transcriptomic technologies, beginning with microarrays in the 1990s, has long supported biomarker discovery and studies of cellular heterogeneity.128 However, determining transcriptomic heterogeneity between cell types through “bulk” assays, which rely on pooled samples of many individual cells, presents a circular problem. Bulk assays rely on well-defined biomarkers or techniques to fraction cells into known, distinct populations. Early attempts to characterize transcriptome-wide BEC gene expression applied microarray assays to immortalized small and large BEC lines from mouse liver. These studies demonstrated substantial transcriptomic differences between the cell types, including confirmatory differential expression of genes previously reported to distinguish small and large BECs.129 However, similar to all studies relying on immortalized cell lines, it is unclear to what degree in vitro cultivation impacted transcriptomic results. More recently, BEC subpopulations isolated by ST14 or Sox9EGFP expression were subjected to RNA-seq, once again demonstrating substantial transcriptomic differences between BEC populations presumed to be distinct.49,51 Although these studies are important in that they provide conceptual proof of concept that all intrahepatic BECs are not transcriptomically homogeneous, they all failed to identify or validate distinct genetic biomarkers of BEC subpopulations that have been adopted widely in the field.

Although biomarkers are an important tool for identifying and studying cellular heterogeneity, they remain intrinsically limited by the fact that genes are rarely, if ever, expressed in a single cell type. In recent years, rapid technological advancements in scRNA-seq have facilitated unprecedented studies of single-cell transcriptomes in increasing numbers of cells.130, 131, 132 Similarly, rapid gains in computational tools have allowed cell biologists to identify and validate novel cellular subpopulations in scRNA-seq without any a priori knowledge of cell type–specific biomarkers. Such studies have led to remarkable findings, including the identification of many new cellular subpopulations within cell types that were previously thought to be relatively homogenous, including intestinal tuft cells and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells.5,133 Because of its central relevance to organismal homeostasis and involvement in a wide range of human pathologic conditions, the liver has been the focus of several large scRNA-seq studies aimed at generating cell “atlases.”53, 54, 55,134 However, because liver cell isolation protocols do not often provide robust isolation of BECs, they are frequently underrepresented in “whole liver” scRNA-seq data sets. Regardless, the first human liver cell atlas project examined EPCAM+ cells in an attempt to identify putative bipotent hepatic progenitors.53 An analysis of 1087 EPCAM+ cells demonstrated the existence of subpopulations enriched for conventional hepatocyte or BEC genes. Furthermore, TROP2 was identified as a putative progenitor marker, with organoid-forming capacity restricted to EPCAM+ cells co-expressing intermediate or high levels of TROP2.53 This led to the conclusion that EPCAM+/TROP2int cells represent bipotent human liver progenitors, which may require additional characterization in light of emerging evidence that liver regeneration is driven by transdifferentiation of mature hepatocytes and BECs rather than bipotent liver progenitor cells in mouse models.53,102,108,135, 136, 137, 138

The first scRNA-seq studies to analyze purified BECs were conducted in mice and focused on BEC heterogeneity in homeostasis and following injury.47,52 In one study, 1468 EPCAM+ BECs from 2 C57Bl/6 mice subjected to 16 days of 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC) feeding were analyzed and characterized into 3 major categories: proliferating BECs, inflammatory BECs, and BECs expressing hepatocyte-related genes.52 Classical BEC markers, including Epcam, Spp1, and Krt19, were noted to be expressed in all cells. High levels of YAP target genes were also broadly expressed, but WNT pathway components, including Lgr5, were not.52 Dimensionality reduction, a computational method that attempts to group cells based on their transcriptomes, failed to clearly resolve the well-defined “clusters” generally associated with distinct cell types in scRNA-seq analyses. Although heterogenous distribution of genes associated with the 3 identified BEC subpopulations was observed, the lack of distinct clustering may suggest that transcriptomic differences between these populations are subtle. Notably, the only BECs analyzed in this study were isolated from damaged IHBDs undergoing ductular reaction, and matched control samples were not assessed. An independent study, published concurrently, examined homeostatic IHBDs by scRNA-seq on 2344 EPCAM+ BECs isolated from 3 C57Bl/6 mice. In these analyses, the authors described 2 major BEC subpopulations based on low or high expression of YAP target genes, including Cyr61, Klf6, and Hes1 (also a Notch target gene).47 A subsequent experiment in the same study examined 1268 BECs from a single mouse subjected to DDC for 1 week. Although control BECs failed to form well-defined clusters on dimensionality reduction, control and DDC-treated BECs demonstrated strong differential clustering, explained in part by broad upregulation of inflammatory genes.47 Increased YAP activation was also observed in DDC samples, potentially explaining why YAP heterogeneity was not observed in DDC-treated BECs from Planas-Paz et al.47,52 The lack of distinct BECs “clusters” in both experiments is somewhat confounding in the pursuit of clear genetic biomarkers of BEC subpopulations. One possible explanation is that BEC transcriptomes are largely homogenous. However, technical nuances in scRNA-seq cell isolation, library prep, and sequencing depth can lead to unintended exclusion of difficult-to-isolate cell types or an inability to detect low-expressed genes, impacting the ability to detect or resolve biologically relevant cell subpopulations.139

In a recent study building on their prior liver scRNA-seq atlas, Andrews et al applied single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) in addition to scRNA-seq to increase the detection of rare cell types in human liver.55,56 snRNA-seq, which involves directly releasing nuclei from intact tissues, was compared with scRNA-seq and shown to improve the representation of BECs as a percent of total nuclei/cells examined (3.4% BECs in snRNA-seq vs 2.4% BECs in scRNA-seq, whole liver).56 With snRNA-seq, 6 clusters were identified among 448 BECs by SNN-Louvain clustering, a standard method applied to identify distinct subpopulations in single-cell transcriptomics.56,57 BEC subpopulations were named “Chol-1” through “Chol-6” and classified as progenitor like, cholangiocyte like, and hepatocyte like, based on relative expression levels of genes associated with each classification group.56 Chol-4 BECs were classified as the most “mature” BEC subpopulation based on the highest expression of canonical BEC markers such as AQP1, KRT7, and KRT8. Similar to findings by Aizarani et al, Chol-2, Chol-3, and Chol-6 were described as hepatocyte biased based on the expression of hepatocyte-associated genes, HNF4A and ALB.53,56 Two populations, Chol-1 and Chol-5, were only well represented in snRNA-seq data sets, and interestingly, both were characterized as a less mature/progenitor phenotype. Chol-1 was classified as the least differentiated progenitor based on elevated expression of transcription factors associated with BEC development and pseudotime computational algorithms, which attempt to predict cellular lineage relationships based on gene expression patterns between cell clusters.56 Chol-5 was found to have the highest level of BCL2 expression and was therefore proposed to contain small BECs.56,140 Finally, single-cell transcriptomic assays in human BECs contradicted mouse studies in that WNT signaling was among enriched pathways terms in GO analysis of Chol-4 and Chol-5 BECs, although WNT enrichment was observed only in scRNA-seq and not in snRNA-seq data.47,52,56 Collectively, emerging single-cell assays demonstrate that there is significant transcriptomic heterogeneity in BECs of the IHBDs, although the biological significance of interpopulation gene expression differences and similarity between mouse and human BEC heterogeneity remains unclear.

Limitations of Single-Cell Transcriptomics in BEC Biology

Although single-cell transcriptomics represents a powerful approach to dissecting cellular heterogeneity, inherent limitations in both wet laboratory and computational aspects of scRNA-seq present unique challenges to examining cell types with poor a priori definitions of heterogeneity. As shown in Andrews et al and demonstrated independently in other cell/tissue systems, isolation and enrichment protocols can bias which cell types are observed in scRNA-seq experiments and even alter gene expression.56,141,142 Differences between the number of cells analyzed, sequencing depth, and number of unique genes/transcripts detected per cell can all vary between laboratories as well as experimental “batches” in the same laboratory and lead to difficulty in resolving conflicting observations (current best practices for single-cell transcriptomic experiments are reviewed comprehensively in a study by Luecken and Theis139). Depth of read and transcripts/genes detected per cell, which are closely linked, can have particularly significant impacts on cell subpopulation resolution in tissues such as IHBDs, where biologically significant gene expression differences are unlikely to arise from highly expressed (and easily detected) genes.92 Although computational resolution of distinctly different cell types (such as mesenchymal vs epithelial cells) is facile using standard scRNA-seq analysis pipelines, identifying unique subpopulations in a relatively homogenous tissue remains challenging. Dimensionality reduction and clustering algorithms are also highly sensitive to user input, and decisions about clustering “resolution” (ie, how many clusters are identified by computational pipelines) often require prior knowledge of subpopulation biomarkers or are somewhat arbitrary.143,144 Even the task of comparing previously defined cell subpopulations between different scRNA-seq data sets remains challenging, with a growing number of computational tools being produced to “match” clusters generated in different experiments, often through machine learning–based approaches.145,146

Another limitation of scRNA-seq studies is the loss of spatial information, making it difficult to frame novel BEC subpopulations in the context of classical small vs large BEC definitions. Although emerging spatial transcriptomic assays have been applied to liver sections in several studies, currently accessible commercial solutions for spatial transcriptomics fail to reach single-cell resolution.56,147 As BEC nuclei tend to be tightly packed within sections of IHBDs, these assays are likely insufficient to capture BEC-BEC heterogeneity. Furthermore, the complex, 3-dimensional structure of IHBDs presents an additional hurdle to spatial transcriptomic analyses, as many BEC-BEC spatial relationships may be hard to capture on tissue sections. Advances in spatial transcriptomic assays that facilitate single-cell/single-molecule resolution, as well as 3-dimensional imaging, will be of great interest in further dissecting BEC heterogeneity.148,149

Lineage Relationships and Cellular Identities of Transcriptomically Distinct BEC Subpopulations

Pseudotime analysis of human BEC scRNA-seq in Andrews et al was used to identify a putative progenitor subpopulation of BECs, and a similar approach was used to argue that EPCAM+/TROP2int cells represent bipotent progenitors in human liver.53,56 Although pseudotime analyses are a commonly used computational tool for predicting lineage relationships between subpopulations identified by scRNA-seq, their accuracy remains controversial.150,151 The determination of a BEC progenitor cell type in adult IHBDs is also somewhat difficult to interpret in light of known BEC biology. In mouse and rat models, BEC proliferation at homeostasis has been reported to be <5% by immunohistochemical detection of proliferative markers KI67 or proliferating cell nuclear antigen, with some studies reporting <1% proliferating BECs.50,101,152,153 Studies of proliferative heterogeneity during thioacetamide-induced ductular reaction identified highly proliferative BEC clones in small ductules, whereas BDL is associated with proliferation in large ducts.21,50 Although this could indicate the existence of a singular progenitor-like BEC population interspersed throughout the IHBDs, it could also suggest that multiple populations of functionally distinct BECs (ie, small and large BECs) share similar proliferative capacity after injury and respond in context-dependent manners.

An alternative possibility for relationships between BEC subpopulations observed in scRNA-seq data is that individual BECs cycle through diverse transcriptomically defined “states,” rather than existing as fixed cell “types” defined by stable gene expression. It would then be possible for BECs to adopt new transcriptomic states without proliferating or giving rise to new cells. This model is supported in part by studies from Pepe-Mooney et al47 demonstrating that BECs cycle through transcriptional states defined by YAP levels. An elegant lineage tracing approach demonstrated that BECs could cycle from YAPhi to a YAPlo state by using Cre-lox and smFISH to genetically label Yaphi cells and examine transcription of Yap target genes over time. These experiments showed that BECs labeled while they were expressing high levels of YAPhi marker Hes1 could later downregulate YAP targets, including Cyr61, in the absence of mitosis. YAP activity was further shown to be upregulated in response to BAs through ASBT, suggesting that dynamic BEC transcriptional programs are responsive to environmental changes.47 In further support of Yap-mediated BEC heterogeneity, Sox9EGFP levels in BECs were shown to correlate with expression of Yap target genes, with EGFPlo cells being consistent with Yaplo BECs and EGFPhi cells demonstrating increased expression of Yap target genes.49 Although these data present a compelling argument for dynamic BEC “states,” it remains unknown if observed changes in YAP target genes reflect similar dynamics in global, transcriptome-level expression changes.

With the emergence and progressively lower cost barrier of scRNA-seq, one immediate solution to circumvent the lack of consensus BEC subpopulation biomarkers is to apply unbiased single-cell transcriptomics to studies of IHBD biology. A recent study on the role of primary cilia in hepatic cyst formation leveraged this approach to demonstrate that loss of Wdr35 in adult BECs upregulates transforming growth factor beta and extracellular matrix genes to drive cystogenesis in IHBDs.154 In this case, single-cell transcriptomics allowed for consideration of BEC heterogeneity while facilitating mechanistic insight into a disease phenotype.

Conclusions and Outlook

Despite known BEC morphologic and functional heterogeneity and several candidate biomarkers (ST14, Yap activity, Sox9EGFP levels), a widely accepted consensus set of genetic biomarkers that can be used to identify discrete BEC subpopulations remains elusive. The ability of the field to establish such a gene set from existing knowledge may be hindered in part by species-specific differences between models used to study BECs and the ability of such models to recapitulate human liver biology. Emerging evidence also suggests that the intrinsic biology of BECs themselves may defy simple classification into fixed subpopulations. In all currently published scRNA-seq data sets, expression of genes identified as cluster-specific markers does not appear to be unique to any one subpopulation of BECs. Rather, genetic heterogeneity of BECs appears to emerge largely from differences in expression levels of gene sets, rather than an “on”/“off” state for individual biomarkers.47,52,53,56 Reaching a “ground truth” definition of different BEC subpopulations might therefore require novel conceptual framework that moves beyond the search for single, cell type defining biomarkers often applied in other epithelial tissues. In addition, if individual BECs are capable of actively cycling between distinct transcriptomic states, the task of assigning BECs to subpopulations representing stable cell identities might be conceptually impossible. Further studies are needed to generate a deeper understanding of BEC heterogeneity, dynamic transcriptional changes in IHBDs, and how BEC states or types may change in the setting of disease or injury.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Fransky Hantelys for critical reading of the article and helpful comments.

Authors’ Contributions

Hannah R. Hrncir generated figures and tables. Hannah R. Hrncir and Adam D. Gracz drafted and edited the article.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01DK132653 to ADG and F31DK134199 to HRH). HRH received additional support from the Emory University Training Program in Biochemistry, Cell and Developmental Biology (T32GM135060).

Ethical Statement: The study did not require the approval of an institutional review board.

References

- 1.Bowcutt R., Forman R., Glymenaki M., et al. Heterogeneity across the murine small and large intestine. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:15216–15232. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i41.15216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukuda M., Mizutani T., Mochizuki W., et al. Small intestinal stem cell identity is maintained with functional Paneth cells in heterotopically grafted epithelium onto the colon. Genes Dev. 2014;28:1752–1757. doi: 10.1101/gad.245233.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutierrez G.D., Gromada J., Sussel L. Heterogeneity of the pancreatic beta cell. Front Genet. 2017;8:22. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2017.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burclaff J., Bliton R.J., Breau K.A., et al. A proximal-to-distal survey of healthy adult human small intestine and colon epithelium by single-cell transcriptomics. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;13:1554–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2022.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haber A.L., Biton M., Rogel N., et al. A single-cell survey of the small intestinal epithelium. Nature. 2017;551:333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature24489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segerstolpe A., Palasantza A., Eliasson P., et al. Single-cell transcriptome profiling of human pancreatic islets in health and type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2016;24:593–607. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozougwu J.C. Physiology of the liver. Int J Res Pharm Biosci. 2017;4:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esteller A. Physiology of bile secretion. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5641–5649. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masyuk A.I., Marinelli R.A., LaRusso N.F. Water transport by epithelia of the digestive tract. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:545–562. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyer J.L. Bile duct epithelium: frontiers in transport physiology. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1996;270:G1–G5. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.270.1.G1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clerbaux L.A., Manco R., Van Hul N., et al. Invasive ductular reaction operates hepatobiliary junctions upon hepatocellular injury in rodents and humans. Am J Pathol. 2019;189:1569–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamimoto K., Nakano Y., Kaneko K., et al. Multidimensional imaging of liver injury repair in mice reveals fundamental role of the ductular reaction. Commun Biol. 2020;3:289. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-1006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemaigre F.P. Development of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tract: a framework for understanding congenital diseases. Annu Rev Pathol. 2020;15:1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-013013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roskams T., Desmet V. Embryology of extra- and intrahepatic bile ducts, the ductal plate. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2008;291:628–635. doi: 10.1002/ar.20710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huppert S.S., Iwafuchi-Doi M. In: Wellik D.M., editor. Vol. 132. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA: 2019. Chapter four - molecular regulation of mammalian hepatic architecture; pp. 1–136. (Current topics in developmental biology). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma R., Martínez-Ramírez A.S., Borders T.L., et al. Metabolic and non-metabolic liver zonation is established non-synchronously and requires sinusoidal Wnts. Elife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.46206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben-Moshe S., Itzkovitz S. Spatial heterogeneity in the mammalian liver. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:395–410. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaffner F., Popper H. Electron microscopic studies of normal and proliferated bile ductules. Am J Pathol. 1961;38:393–410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludwig J. New concepts in biliary cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis. 1987;7:293–301. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasaki H., Schaffner F., Popper H. Bile ductules in cholestasis: morphologic evidence for secretion and absorption in man. Lab Invest. 1967;16:84–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glaser S.S., Gaudio E., Rao A., et al. Morphological and functional heterogeneity of the mouse intrahepatic biliary epithelium. Lab Invest. 2009;89:456–469. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanno N., LeSage G., Glaser S., et al. Functional heterogeneity of the intrahepatic biliary epithelium. Hepatology. 2000;31:555–561. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alpini G., Roberts S., Kuntz S.M., et al. Morphological, molecular, and functional heterogeneity of cholangiocytes from normal rat liver. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1636–1643. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alpini G., Glaser S., Robertson W., et al. Large but not small intrahepatic bile ducts are involved in secretin-regulated ductal bile secretion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1997;272:G1064–G1074. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.5.G1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Jong I.E.M., van Leeuwen O.B., Lisman T., et al. Repopulating the biliary tree from the peribiliary glands. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864:1524–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benedetti A., Bassotti C., Rapino K., et al. A morphometric study of the epithelium lining the rat intrahepatic biliary tree. J Hepatol. 1996;24:335–342. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gershwin M.E., Mackay I.R. The causes of primary biliary cirrhosis: convenient and inconvenient truths. Hepatology. 2008;47:737–745. doi: 10.1002/hep.22042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masyuk A.I., Masyuk T.V., Splinter P.L., et al. Cholangiocyte cilia detect changes in luminal fluid flow and transmit them into intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP signaling. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:911–920. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansini A.P., Peixoto E., Thelen K.M., et al. The cholangiocyte primary cilium in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864:1245–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang B.Q., Masyuk T.V., Muff M.A., et al. Isolation and characterization of cholangiocyte primary cilia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G500–G509. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00064.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiPaola F., Shivakumar P., Pfister J., et al. Identification of intramural epithelial networks linked to peribiliary glands that express progenitor cell markers and proliferate after injury in mice. Hepatology. 2013;58:1486–1496. doi: 10.1002/hep.26485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayata Y., Nakagawa H., Kurosaki S., et al. Axin2(+) peribiliary glands in the periampullary region generate biliary epithelial stem cells that give rise to ampullary carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:2133–2148.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lazaridis K.N., LaRusso N.F. The cholangiopathies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:791–800. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindkvist B., Benito de Valle M., Gullberg B., et al. Incidence and prevalence of primary sclerosing cholangitis in a defined adult population in Sweden. Hepatology. 2010;52:571–577. doi: 10.1002/hep.23678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Björnsson E., Olsson R., Bergquist A., et al. The natural history of small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:975–980. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Björnsson E. Small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11:37–41. doi: 10.1007/s11894-009-0006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Björnsson E., Boberg K.M., Cullen S., et al. Patients with small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis have a favourable long term prognosis. Gut. 2002;51:731–735. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.5.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chung B.K., Karlsen T.H., Folseraas T. Cholangiocytes in the pathogenesis of primary sclerosing cholangitis and development of cholangiocarcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864:1390–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kruepunga N., Hakvoort T.B.M., Hikspoors J.P.J.M., et al. Anatomy of rodent and human livers: what are the differences? Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2019;1865:869–878. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorent K., Moore J.C., Siekmann A.F., et al. Reiterative use of the notch signal during zebrafish intrahepatic biliary development. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:855–864. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russell J.O., Ko S., Monga S.P., et al. Notch inhibition promotes differentiation of liver progenitor cells into hepatocytes via sox9b repression in zebrafish. Stem Cells Int. 2019;2019:8451282. doi: 10.1155/2019/8451282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higashiyama H., Uemura M., Igarashi H., et al. Anatomy and development of the extrahepatic biliary system in mouse and rat: a perspective on the evolutionary loss of the gallbladder. J Anat. 2018;232:134–145. doi: 10.1111/joa.12707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pham D.-H., Zhang C., Yin C. Using zebrafish to model liver diseases-where do we stand? Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2017;5:207–221. doi: 10.1007/s40139-017-0141-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lorent K., Yeo S.-Y., Oda T., et al. Inhibition of Jagged-mediated Notch signaling disrupts zebrafish biliary development and generates multi-organ defects compatible with an Alagille syndrome phenocopy. Development. 2004;131:5753–5766. doi: 10.1242/dev.01411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yao Y., Lin J., Yang P., et al. Fine structure, enzyme histochemistry, and immunohistochemistry of liver in zebrafish. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2012;295:567–576. doi: 10.1002/ar.22416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ota N., Shiojiri N. Comparative study on a novel lobule structure of the zebrafish liver and that of the mammalian liver. Cell Tissue Res. 2022;388:287–299. doi: 10.1007/s00441-022-03607-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pepe-Mooney B.J., Dill M.T., Alemany A., et al. Single-cell analysis of the liver epithelium reveals dynamic heterogeneity and an essential role for YAP in homeostasis and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;25:23–38.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrison J.K., DeRossi C., Alter I.L., et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals conserved cell identities and fibrogenic phenotypes in zebrafish and human liver. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:1711–1724. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tulasi D.Y., Castaneda D.M., Wager K., et al. Sox9EGFP defines biliary epithelial heterogeneity downstream of Yap activity. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;11:1437–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kamimoto K., Kaneko K., Kok C.Y., et al. Heterogeneity and stochastic growth regulation of biliary epithelial cells dictate dynamic epithelial tissue remodeling. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.15034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li B., Dorrell C., Canaday P.S., et al. Adult mouse liver contains two distinct populations of cholangiocytes. Stem Cell Rep. 2017;9:478–489. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Planas-Paz L., Sun T., Pikiolek M., et al. YAP, but not RSPO-LGR4/5, signaling in biliary epithelial cells promotes a ductular reaction in response to liver injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;25:39–53.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aizarani N., Saviano A., Sagar, et al. A human liver cell atlas reveals heterogeneity and epithelial progenitors. Nature. 2019;572:199–204. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1373-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen T., Oh S., Gregory S., et al. Single-cell omics analysis reveals functional diversification of hepatocytes during liver regeneration. JCI Insight. 2020;5 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.141024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacParland S.A., Liu J.C., Ma X.Z., et al. Single cell RNA sequencing of human liver reveals distinct intrahepatic macrophage populations. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4383. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06318-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andrews T.S., Atif J., Liu J.C., et al. Single-cell, single-nucleus, and spatial RNA sequencing of the human liver identifies cholangiocyte and mesenchymal heterogeneity. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:821–840. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Satija R., Farrell J.A., Gennert D., et al. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:495–502. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Couinaud C. Liver anatomy: portal (and suprahepatic) or biliary segmentation. Dig Surg. 1999;16:459–467. doi: 10.1159/000018770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Germain L., Blouin M.J., Marceau N. Biliary epithelial and hepatocytic cell lineage relationships in embryonic rat liver as determined by the differential expression of cytokeratins, alpha-fetoprotein, albumin, and cell surface-exposed components. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4909–4918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shiojiri N. The origin of intrahepatic bile duct cells in the mouse. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1984;79:25–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lemaigre F.P. Development of the biliary tract. Mech Dev. 2003;120:81–87. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kodama Y., Hijikata M., Kageyama R., et al. The role of notch signaling in the development of intrahepatic bile ducts. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1775–1786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Antoniou A., Raynaud P., Cordi S., et al. Intrahepatic bile ducts develop according to a new mode of tubulogenesis regulated by the transcription factor SOX9. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2325–2333. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lozier J., McCright B., Gridley T. Notch signaling regulates bile duct morphogenesis in mice. PLoS One. 2008;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilkins B.J., Pack M. Zebrafish models of human liver development and disease. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:1213–1230. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pham D.-H., Yin C. Zebrafish as a model to study cholestatic liver diseases. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1981:273–289. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9420-5_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tao T., Peng J. Liver development in zebrafish (Danio rerio) J Genet Genomics. 2009;36:325–334. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guo G.L., Chiang J.Y. Is CYP2C70 the key to new mouse models to understand bile acids in humans? J Lipid Res. 2020;61:269–271. doi: 10.1194/jlr.C120000621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Takahashi S., Fukami T., Masuo Y., et al. Cyp2c70 is responsible for the species difference in bile acid metabolism between mice and humans. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:2130–2137. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M071183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Palmes D., Spiegel H.-U. Animal models of liver regeneration. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1601–1611. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Delire B., Stärkel P., Leclercq I. Animal models for fibrotic liver diseases: what we have, what we need, and what is under development. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2015;3:53–66. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2014.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mariotti V., Strazzabosco M., Fabris L., et al. Animal models of biliary injury and altered bile acid metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864:1254–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prior N., Inacio P., Huch M. Liver organoids: from basic research to therapeutic applications. Gut. 2019;68:2228–2237. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kuijk E.W., Rasmussen S., Blokzijl F., et al. Generation and characterization of rat liver stem cell lines and their engraftment in a rat model of liver failure. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep22154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Han Y., Glaser S., Meng F., et al. Recent advances in the morphological and functional heterogeneity of the biliary epithelium. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2013;238:549–565. doi: 10.1177/1535370213489926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Francis H., Glaser S., DeMorrow S., et al. Small mouse cholangiocytes proliferate in response to H1 histamine receptor stimulation by activation of the IP3/CaMK I/CREB pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C499–C513. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00369.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hall C., Sato K., Wu N., et al. Regulators of cholangiocyte proliferation. Gene Expr. 2017;17:155–171. doi: 10.3727/105221616X692568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alpini G., Franchitto A., Demorrow S., et al. Activation of alpha(1)-adrenergic receptors stimulate the growth of small mouse cholangiocytes via calcium-dependent activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells 2 and specificity protein 1. Hepatology. 2011;53:628–639. doi: 10.1002/hep.24041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alvaro D., Benedetti A., Marucci L., et al. The function of alkaline phosphatase in the liver: regulation of intrahepatic biliary epithelium secretory activities in the rat. Hepatology. 2000;32:174–184. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.9078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kennedy L., Meadows V., Kyritsi K., et al. Amelioration of large bile duct damage by histamine-2 receptor vivo-morpholino treatment. Am J Pathol. 2020;190:1018–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Afroze S., Meng F., Jensen K., et al. The physiological roles of secretin and its receptor. Ann Transl Med. 2013;1:29. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2012.12.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alpini G., Ulrich C., Roberts S., et al. Molecular and functional heterogeneity of cholangiocytes from rat liver after bile duct ligation. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G289–G297. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.2.G289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.René E., Danzinger R.G., Hofmann A.F., et al. Pharmacologic effect of somatostatin on bile formation in the dog. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:120–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ricci G.L., Fevery J. Somatostatin inhibits the effect of secretin on bile flow and on hepatic bilirubin transport in the rat. Gut. 1989;30:1266–1269. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.9.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alpini G., Glaser S.S., Ueno Y., et al. Heterogeneity of the proliferative capacity of rat cholangiocytes after bile duct ligation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1998;274:G767–G775. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.4.G767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tietz P.S., Alpini G., Pham L.D., et al. Somatostatin inhibits secretin-induced ductal hypercholeresis and exocytosis by cholangiocytes. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:G110–G118. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.1.G110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gong A.-Y., Tietz P.S., Muff M.A., et al. Somatostatin stimulates ductal bile absorption and inhibits ductal bile secretion in mice via SSTR2 on cholangiocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C1205–C1214. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00313.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Renzi A., Glaser S., Demorrow S., et al. Melatonin inhibits cholangiocyte hyperplasia in cholestatic rats by interaction with MT1 but not MT2 melatonin receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G634–G643. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00206.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tan D., Manchester L.C., Reiter R.J., et al. High physiological levels of melatonin in the bile of mammals. Life Sci. 1999;65:2523–2529. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Luo Z.-L., Cheng L., Wang T., et al. Bile acid transporters are expressed and heterogeneously distributed in rat bile ducts. Gut Liver. 2019;13:569–575. doi: 10.5009/gnl18265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.LeSage G.D., Benedetti A., Glaser S., et al. Acute carbon tetrachloride feeding selectively damages large, but not small, cholangiocytes from normal rat liver. Hepatology. 1999;29:307–319. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pollen A.A., Nowakowski T.J., Shuga J., et al. Low-coverage single-cell mRNA sequencing reveals cellular heterogeneity and activated signaling pathways in developing cerebral cortex. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:1053–1058. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li X., Yang S., Deepak V., et al. Identification of cilia in different mouse tissues. Cells. 2021;10:1623. doi: 10.3390/cells10071623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Poncy A., Antoniou A., Cordi S., et al. Transcription factors SOX4 and SOX9 cooperatively control development of bile ducts. Dev Biol. 2015;404:136–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xu W.P., Cui Y.L., Chen L.L., et al. Deletion of Sox9 in the liver leads to hepatic cystogenesis in mice by transcriptionally downregulating Sec63. J Pathol. 2021;254:57–69. doi: 10.1002/path.5636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Masyuk T.V., Huang B.Q., Ward C.J., et al. Defects in cholangiocyte fibrocystin expression and ciliary structure in the PCK rat. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Banales J.M., Huebert R.C., Karlsen T., et al. Cholangiocyte pathobiology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:269–281. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0125-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Amaya M.J., Nathanson M.H. Calcium signaling in the liver. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:515–539. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hirata K., Dufour J.F., Shibao K., et al. Regulation of Ca(2+) signaling in rat bile duct epithelia by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor isoforms. Hepatology. 2002;36:284–296. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Banales J.M., Arenas F., Rodríguez-Ortigosa C.M., et al. Bicarbonate-rich choleresis induced by secretin in normal rat is taurocholate-dependent and involves AE2 anion exchanger. Hepatology. 2006;43:266–275. doi: 10.1002/hep.21042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kaneko K., Kamimoto K., Miyajima A., et al. Adaptive remodeling of the biliary architecture underlies liver homeostasis. Hepatology. 2015;61:2056–2066. doi: 10.1002/hep.27685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ko S., Russell J.O., Molina L.M., et al. Liver progenitors and adult cell plasticity in hepatic injury and repair: knowns and unknowns. Annu Rev Pathol. 2020;15:23–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012419-032824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Alpini G.P., Ueno Y., Glaser S.S., et al. Bile acid feeding increased proliferative activity and apical bile acid transporter expression in both small and large rat cholangiocytes. Hepatology. 2001;34:868–876. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Erlandsen S.L., Parsons J.A., Taylor T.D. Ultrastructural immunocytochemical localization of lysozyme in the Paneth cells of man. J Histochem Cytochem. 1974;22:401–413. doi: 10.1177/22.6.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gaasbeek Janzen J.W., Gebhardt R., ten Voorde G.H., et al. Heterogeneous distribution of glutamine synthetase during rat liver development. J Histochem Cytochem. 1987;35:49–54. doi: 10.1177/35.1.2878950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cardinale V., Wang Y., Carpino G., et al. Multipotent stem/progenitor cells in human biliary tree give rise to hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, and pancreatic islets. Hepatology. 2011;54:2159–2172. doi: 10.1002/hep.24590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Carpentier R., Suner R.E., van Hul N., et al. Embryonic ductal plate cells give rise to cholangiocytes, periportal hepatocytes, and adult liver progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1432–1438. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.049. 1438.e1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lu W.Y., Bird T.G., Boulter L., et al. Hepatic progenitor cells of biliary origin with liver repopulation capacity. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:971–983. doi: 10.1038/ncb3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vestentoft P.S., Jelnes P., Hopkinson B.M., et al. Three-dimensional reconstructions of intrahepatic bile duct tubulogenesis in human liver. BMC Dev Biol. 2011;11:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-11-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhan Y., Ward S.C., Fiel M.I., et al. EpCam is required for maintaining the integrity of the biliary epithelium. Liver Int. 2021;41:2132–2138. doi: 10.1111/liv.14891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Athwal V.S., Pritchett J., Llewellyn J., et al. SOX9 predicts progression toward cirrhosis in patients while its loss protects against liver fibrosis. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9:1696–1710. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201707860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Furuyama K., Kawaguchi Y., Akiyama H., et al. Continuous cell supply from a Sox9-expressing progenitor zone in adult liver, exocrine pancreas and intestine. Nat Genet. 2011;43:34–41. doi: 10.1038/ng.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Han X., Wang Y., Pu W., et al. Lineage tracing reveals the bipotency of SOX9(+) hepatocytes during liver regeneration. Stem Cell Rep. 2019;12:624–638. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Font-Burgada J., Shalapour S., Ramaswamy S., et al. Hybrid periportal hepatocytes regenerate the injured liver without giving rise to cancer. Cell. 2015;162:766–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Liu Y., Zhuo S., Zhou Y., et al. Yap-Sox9 signaling determines hepatocyte plasticity and lineage-specific hepatocarcinogenesis. J Hepatol. 2022;76:652–664. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dorrell C., Tarlow B., Wang Y., et al. The organoid-initiating cells in mouse pancreas and liver are phenotypically and functionally similar. Stem Cell Res. 2014;13:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Barker N., Huch M., Kujala P., et al. Lgr5(+ve) stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Barker N., van Es J.H., Kuipers J., et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cao W., Chen K., Bolkestein M., et al. Dynamics of proliferative and quiescent stem cells in liver homeostasis and injury. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:1133–1147. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Huch M., Dorrell C., Boj S.F., et al. In vitro expansion of single Lgr5+ liver stem cells induced by Wnt-driven regeneration. Nature. 2013;494:247–250. doi: 10.1038/nature11826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sun T., Pikiolek M., Orsini V., et al. AXIN2(+) pericentral hepatocytes have limited contributions to liver homeostasis and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26:97–107.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wang B., Zhao L., Fish M., et al. Self-renewing diploid Axin2(+) cells fuel homeostatic renewal of the liver. Nature. 2015;524:180–185. doi: 10.1038/nature14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Formeister E.J., Sionas A.L., Lorance D.K., et al. Distinct SOX9 levels differentially mark stem/progenitor populations and enteroendocrine cells of the small intestine epithelium. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1108–G1118. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00004.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gong S., Zheng C., Doughty M.L., et al. A gene expression atlas of the central nervous system based on bacterial artificial chromosomes. Nature. 2003;425:917–925. doi: 10.1038/nature02033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gracz A.D., Ramalingam S., Magness S.T. Sox9 expression marks a subset of CD24-expressing small intestine epithelial stem cells that form organoids in vitro. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G590–G600. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00470.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Raab J.R., Tulasi D.Y., Wager K.E., et al. Quantitative classification of chromatin dynamics reveals regulators of intestinal stem cell differentiation. Development. 2020;147 doi: 10.1242/dev.181966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Peng W.C., Logan C.Y., Fish M., et al. Inflammatory cytokine TNFalpha promotes the long-term expansion of primary hepatocytes in 3D culture. Cell. 2018;175:1607–1619.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lowe R., Shirley N., Bleackley M., et al. Transcriptomics technologies. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ueno Y., Alpini G., Yahagi K., et al. Evaluation of differential gene expression by microarray analysis in small and large cholangiocytes isolated from normal mice. Liver Int. 2003;23:449–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2003.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Jaitin D.A., Kenigsberg E., Keren-Shaul H., et al. Massively parallel single-cell RNA-seq for marker-free decomposition of tissues into cell types. Science. 2014;343:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.1247651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Macosko E.Z., Basu A., Satija R., et al. Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell. 2015;161:1202–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Tang F., Barbacioru C., Wang Y., et al. mRNA-Seq whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell. Nat Methods. 2009;6:377–382. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Halpern K.B., Shenhav R., Massalha H., et al. Paired-cell sequencing enables spatial gene expression mapping of liver endothelial cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:962–970. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Halpern K.B., Shenhav R., Matcovitch-Natan O., et al. Single-cell spatial reconstruction reveals global division of labour in the mammalian liver. Nature. 2017;542:352–356. doi: 10.1038/nature21065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Aloia L., McKie M.A., Vernaz G., et al. Epigenetic remodelling licences adult cholangiocytes for organoid formation and liver regeneration. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21:1321–1333. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0402-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Gadd V.L., Aleksieva N., Forbes S.J. Epithelial plasticity during liver injury and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;27:557–573. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hu S., Russell J.O., Liu S., et al. beta-Catenin-NF-kappaB-CFTR interactions in cholangiocytes regulate inflammation and fibrosis during ductular reaction. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.71310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Raven A., Lu W.Y., Man T.Y., et al. Cholangiocytes act as facultative liver stem cells during impaired hepatocyte regeneration. Nature. 2017;547:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature23015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]