Abstract

Purpose

Public involvement is widely considered a means to improve health and quality of health services. The research literature reveals ambiguities concerning added value and unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes. The aim of this study is to identify, synthesise and present an overview of added value and unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes in the planning, development and implementation of community health services.

Methods

Data from 36 peer‐reviewed articles retrieved from a systematic search in the CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed, ProQuest, and Scopus databases in October 2019 and updated in April 2021 were extracted. A three‐step thematic synthesis was conducted involving (1) line‐by‐line text coding, (2) developing descriptive themes and (3) generating analytical themes.

Results

Two main themes along with their corresponding themes provided an overview of the added value of public involvement processes at the individual, service and political levels. Unintended negative consequences concerning individual resources, uncertainty about the effect of involvement and power differences were revealed.

Conclusion

Added value of public involvement processes is primarily reported on an individual and service level. The added value seems to be accompanied by unintended negative consequences. Training of professional facilitators and recruitment of participants that come from vulnerable groups could help promote equality in public involvement. Unintended negative consequences need to be further explored in future evaluations in order to achieve the desired goals of public involvement.

Keywords: added value, community health services, community involvement, public involvement, review, unintended negative consequences

Highlights

This study identifies added value and unintended negative consequences of public involvement.

Added value of public involvement was primarily reported on individual and service levels.

Unintended negative consequences concerned requirement of individual resources, influence uncertainty and power differences.

Professional facilitators and recruitment of vulnerable participants is important to promote equality in public involvement.

1. INTRODUCTION

Public involvement is widely considered a means for improving individual health and quality of health services. 1 , 2 , 3 Divergent understandings and interpretations of public involvement are apparent in the research literature. Public involvement in organisational decision‐making processes is often applied to shape the development and planning of health services. Public involvement in organisational decision making refers to how lay communities and individuals participate in decisions about the development and planning of health services. 4

Contradictory understanding of the added value of public involvement can be seen in several studies. Bath & Wakerman 5 reported an association between public involvement and improved public health, while Rifkin 3 found no connection between public involvement and health improvements. If the benefits of public involvement in health planning continues, we need to find ways to involve stakeholders more equally. Viewing public involvement as strongly influenced by contextual factors, Haldane et al. 1 emphasise looking into the public involvement processes. As stated by Minkler and Wallerstein, 6 we need to understand the added value and identify characteristics of successful public involvement processes.

Uncertainties and conflicting views of public involvement might explain difficulties in assessing added value. 7 Even though a wide range of studies have been conducted, there seems to be no consensus on the desired level of influence on decisions offered to the public when it comes to public involvement in organisational decision making. These studies—some of which are positioned in health intervention research 1 , 2 and others in implementation research 3 , 8 , 9 —aim to evaluate public involvement. Researchers have debated the use of randomised controlled trials to evaluate public involvement, as it might not be possible to intervene with standardised ‘doses’ independent of processes and contexts. 8 Public involvement should instead be explored by investigating added value and by looking into the processes rather than being considered an intervention with predefined outcomes. 3 , 8 , 9

Several studies have reported unintended consequences of public involvement processes. 7 , 10 , 11 Among these unintended consequences, differences in decision‐making processes between involved participants have been observed. These differences may potentially lead to tokenistic public involvement and power differences may be experienced as exclusionary when some groups do not influence the decision‐making process. 7 Staniszewska, Brett, Mockford & Barber 11 emphasise the need to explore unintended negative consequences of public involvement as most studies have exclusively reported positive outcomes and thus ignore the negative aspects that could pose potential barriers. Rifkin, 3 Draper et al. 8 and Minkler & Wallerstein 6 call for a broader perspective to elucidate both added value and unintended negative consequences of public involvement. A comprehensive exploration of pros and cons when practicing public involvement ranging from planning to provision of services is relevant and needed.

This current article is Part 2 of a scoping review. Results of Part 1 are presented in an article by Pedersen et al. 12 and provides a comprehensive overview of the research literature on public involvement in the planning, development and implementation of community health services. In the first part of the review, we examined and characterised public involvement methods. This second part aims to identify, synthesise and present an overview of added value and unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes in the planning, development and implementation of these services.

2. METHODS

Prior to the thematic synthesis, we conducted a systematic literature search inspired by the framework developed by Arksey and O'Malley 13 and advanced by Levac et al. 14 regarding the literature on public involvement. As mentioned in the Introduction, the results of Part 1 of the review are presented in a scoping review article by Pedersen et al. 12 . The research question raised in Part 1 was ‘Which public involvement methods are used in the planning, development, and implementation of community health services and what characterises these public involvement methods?’ For the present study, a thematic synthesis of the 36 articles included from Part 1 of the scoping review aims to provide an overview of the added value and negative consequences related to public involvement processes. Inspired by Rifkin, 3 we defined added value as positive aspects of public involvement processes. Added value of public involvement processes pertained to several levels: individual, service and political. We defined unintended negative consequences as negative aspects of public involvement processes. 11

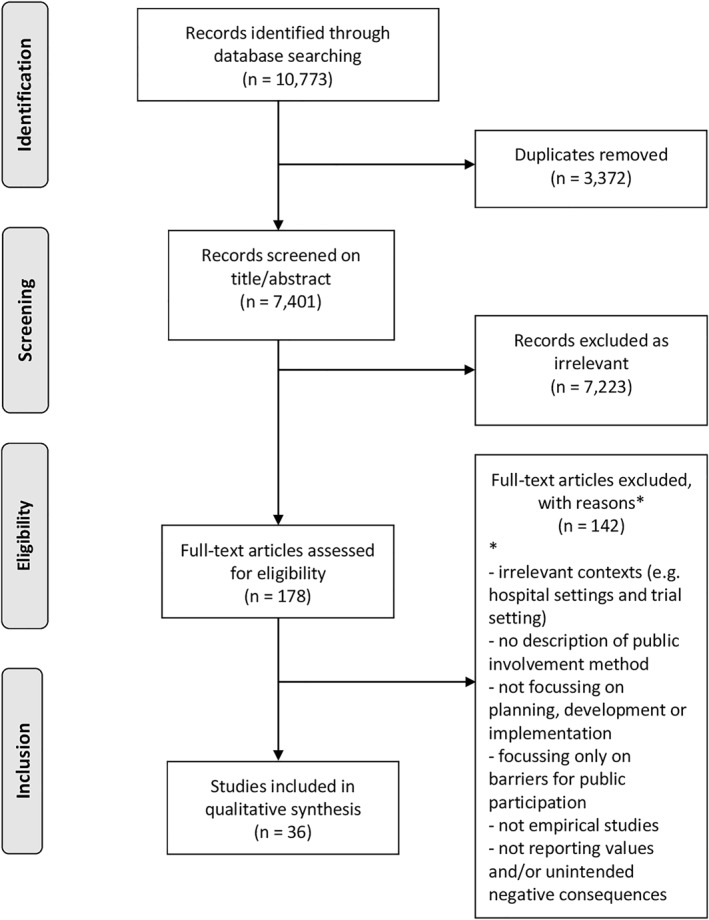

The articles included in the thematic synthesis were retrieved from a systematic search in the CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed, ProQuest and Scopus databases. The search was conducted in October 2019 and repeated and updated in April 2021. Inspired by the Joanna Briggs Institute's work, 15 a focussed research question containing terms related to Patient (P), Concept (C) and Context (C) was applied and operationalised into Public Involvement (P), Methods of Public Involvement (C) and Community Health Services (C). The scoping review by Pedersen et al. 12 included 39 articles, three of which were excluded for the thematic synthesis as they did not report added value and/or unintended negative consequences of public involvement 16 , 17 , 18 (see Figure 1). The remaining 36 articles, published between 1992 and 2020, were included in this study. A detailed description of the methods and results of the scoping review is provided in Pedersen et al. 12

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA Flow diagram of the search strategy and results of the screening process

2.1. Included articles

Table 1 provides an overview of the 36 included articles. Seven articles were reported as ‘evaluation studies’ with evaluation as the primary aim. Thirteen studies with various study designs carried out some kind of evaluation but had evaluation as the secondary aim. Seven different design types were identified in the included articles (Table 1). Table 4 provides an overview of which articles reported which added value. In 24 of the 36 articles, added value pertaining to the individual level were reported. 30 of the 36 articles reported added value on the service level while 4 of the 36 articles reported added value on a political level. Unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes were reported in 17 of the 36 articles.

TABLE 1.

Overview of the 36 included articles, study design, whether or not evaluated, assessment of relevance of focus on how sufficient added values and unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes were described

| Author (year) | Study design | Carried out evaluation (Yes/no) | Assessment of relevance (1–2 point) a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carlisle et al. (2018) | Evaluation study | Yes | 2 |

| Clark (1997) | Case study | No | 1 |

| Crowley et al. (2002) | Case study | Yes | 1 |

| Díez et al. (2018) | Participatory approach | No | 2 |

| Farmer and Nimegeer (2014) | Participatory approach | Yes | 1 |

| Goold et al. (2005) | Evaluation study | Yes | 2 |

| Iyer et al. (2015) | Participatory approach | Yes | 1 |

| Jeffery and Ervin (2011) | Participatory approach | No | 1 |

| Katzburg et al. (2009) | Mixed methods | Yes | 1 |

| Khodyakov et al. (2014) | Mixed methods | Yes | 2 |

| Lamb et al. (2014) | Evaluation study | Yes | 1 |

| LaNoue et al. (2016) | Mixed methods | No | 1 |

| Lazenbatt et al. (2001) | Case study | No | 2 |

| Lee et al. (2009) | Evaluation study | Yes | 1 |

| Morain et al. (2017) | Mixed methods | Yes | 1 |

| Munoz (2013) | Case study | No | 2 |

| Muurinen (2019) | Case study | No | 2 |

| Myers et al. (2020) | Survey | Yes | 2 |

| Nancarrow et al. (2004) | Case study | Yes | 1 |

| Nimegeer et al. (2016) | Participatory approach | Yes | 1 |

| Owens et al. (2010) | Participatory approach | Yes | 1 |

| Rains and Ray (1995) | Case study | No | 2 |

| Risisky et al. (2008) | Mixed methods | No | 1 |

| Rosén (2006) | Intervention study | No | 2 |

| Seim and Slettebø (2011) | Action research | Yes | 2 |

| Serapioni and Duxbury (2012) | Evaluation study | Yes | 2 |

| Timotijevic and Raats (2007) | Evaluation study | Yes | 2 |

| Twible (1992) | Case study | No | 1 |

| Uding et al. (2009) | Feasibility study | Yes | 1 |

| Valaitis et al. (2019) | Participatory approach | No | 2 |

| Wainwright et al. (2014) | Case study | No | 1 |

| Wang (2006) | Participatory approach | No | 1 |

| Winter et al. (2016) | Participatory approach | No | 2 |

| Woods (2009) | Mixed methods | No | 2 |

| Yankeelov et al. (2019) | Intervention study | Yes | 2 |

| Zani and Cicognani (2009) | Evaluation study | Yes | 1 |

1: ‘partially described’; 2 ‘fully described’.

TABLE 4.

Overview of articles reporting added value and unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes within main themes and corresponding themes

| Author (year) | Public involvement activity | Added value of public involvement processes (Main theme 1) | Unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes (Main theme 2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Added value on the individual level | Added value on the service level | Added value on the political level | Individual resources required | Influence uncertainty | Power differences | ||

| Carlisle et al. (2018) | Combination of activities | • | |||||

| Clark (1997) | Combination of activities | • | |||||

| Crowley et al. (2002) | Combination of activities | • | |||||

| Díez et al. (2018) | Combination of activities | • | • | • | |||

| Farmer and Nimegeer (2014) | Workshop | • | • | • | |||

| Goold et al. (2005) | User group | • | • | • | • | ||

| Iyer et al. (2015) | User panel and Committee | • | • | • | |||

| Jeffery and Ervin (2011) | Combination of activities | • | |||||

| Katzburg et al. (2009) | Combination of activities | • | |||||

| Khodyakov et al. (2014) | Combination of activities | • | • | • | |||

| Lamb et al. (2014) | Combination of activities | • | • | ||||

| LaNoue et al. (2016) | Combination of activities | • | • | ||||

| Lazenbatt et al. (2001) | Combination of activities | • | • | ||||

| Lee et al. (2009) | User group | • | • | ||||

| Morain et al. (2017) | Combination of activities | • | |||||

| Munoz et al. (2013) | Combination of activities | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Muurinen (2019) | Combination of activities | • | • | • | |||

| Myers et al. (2020) | User group | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Nancarrow et al. (2004) | User panel and Committee | • | • | ||||

| Nimegeer et al. (2016) | Workshop | • | • | ||||

| Owens et al. (2010) | Workshop | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Rains and Ray (1995) | Combination of activities | • | • | ||||

| Risisky et al. (2008) | Combination of activities | • | |||||

| Rosén (2006) | Combination of activities | • | |||||

| Seim and Slettebø (2011) | User group | • | • | ||||

| Serapioni and Duxbury (2012) | User panel and Committee | • | • | • | |||

| Timotijevic and Raats (2007) | Combination of activities | • | • | • | • | ||

| Twible (1992) | Nominal group technique | • | |||||

| Uding et al. (2009) | Focus group | • | • | • | |||

| Valaitis et al. (2019) | Workshop | • | • | • | • | ||

| Wainwright et al. (2014) | Nominal group technique | • | • | ||||

| Wang (2006) | Photovoice | • | • | ||||

| Winter et al. (2016) | Combination of activities | • | |||||

| Woods (2009) | Combination of activities | • | • | • | • | ||

| Yankeelov et al. (2019) | User group | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Zani and Cicognani (2009) | Combination of activities | • | • | ||||

2.2. Prior to thematic synthesis: Charting of studies

Added value on the individual, service and political levels and unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes were charted according to a predefined data extraction form. The data extraction form guided the abductive coding process by looking at these levels. Three of the authors extracted data on added value and unintended negative consequences as they were reported in the articles' results and discussion sections. As proposed by Peters et al., 15 we continuously developed and refined the data extraction form and extraction variables to ensure that all relevant data on added value and unintended negative consequences were included in the coding process. An abductive charting process was applied to refine the extraction variables and identify relevant data. The initial charting process was conducted independently by three of the authors, and the results of the coding were compared until consensus was obtained. Based on the results of the initial charting process, the extracted data material was transferred into the qualitative software programme NVivo, version 11 19 to support the thematic synthesis.

2.3. Three‐step thematic synthesis

A three‐step thematic synthesis was conducted, that is, (1) Line‐by‐line text coding, (2) Developing descriptive themes and (3) Generating analytical themes. 20 Based on the line‐by‐line coding, descriptive themes were formulated in the second step of the thematic synthesis which guided the third step, that is, the generation of analytic themes (see Table 2). The coding, development of descriptive themes and generation of analytical themes (Steps 1, 2, and 3) were carried out by the first and last author. The initial and final themes were continuously discussed by these authors, and all four authors took part in critical discussion regarding the identified themes. Based on the abductive approach, we identified themes related to added value of public involvement processes at the individual (e.g., appreciation experienced by those engaged in public involvement activities), service (e.g., health service improvements) and political (e.g., future service priorities) levels. Unintended negative consequences (Main theme 2) revealed three themes based on the inductive approach.

TABLE 2.

Application of the three steps in the thematic synthesis, inspired by Thomas and Harden (2008)

| Thematic synthesis | Application of the three analytical steps |

|---|---|

| Step 1: Coding of text ‘line‐by‐line’ | Text excerpts reporting the values and/or unintended negative consequences of public involvement activities in the studies were coded line‐by‐line, compared and then stored in NVivo. |

| Step 2: Development of ‘descriptive themes’ | Descriptive themes based on the initial coding of the two predefined main themes that is, (1), added value of public involvement processes and (2) unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes, were developed. |

| Step 3: Generation of ‘analytical themes’ | Analytic themes and corresponding sub‐themes were developed based on the descriptive themes derived from step 2. |

| Added value—(1a) added value on the individual level with sub‐themes (i) appreciation, (ii) satisfaction, (iii) health benefits, (iv) attachment (1b) added value on the service level with sub‐themes (i) improved relationships, (ii) understanding of needs, (iii) environmental change and (1c) added value on the political level with sub‐theme (i) service priorities and (ii) policy recommendations. | |

| Unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes that is, (2a) individual resources required, (2b) influence uncertainty and (2c) power differences and then presented as the results with illustrative excerpts from the coded articles. |

2.4. Relevance assessment

Methodological literature on scoping reviews and thematic syntheses does not normally include a quality assessment of included articles. 15 , 20 Inspired by Movsisyan et al., 21 we decided to assess the degree to which the included articles were able to address our research question. Here we focussed on the articles' relevance, that is, the reporting adequacy of added value and unintended negative consequences. As illustrated in Table 1, 1 point was given for a partial description of added value and/or unintended negative consequences, and 2 points were given for an exhaustive description. Despite the significant variation in the reporting adequacy of added value and unintended negative consequences, no articles were excluded due to scores given in the relevance assessment. Seventeen articles exhaustively addressed the relevance aspect in their reporting of added value and/or unintended negative consequences. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 Added value and/or unintended negative consequences were only partially reported in 19 articles 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 (see Table 1).

3. RESULTS

In accordance with our aim, themes and subthemes related to the two predefined main themes were identified: added value of public involvement processes (Main theme 1) and unintended negative consequences (Main theme 2) (see Table 3 Overview of the themes and Table 4 Overview of the characteristics of the included articles).

TABLE 3.

Overview of the identified main themes with corresponding themes and sub‐themes

| Main theme | Theme | Sub‐theme |

|---|---|---|

| Added value of public involvement processes (1) | Added value on the individual level (1a) | (i) Appreciation |

| (ii) Satisfaction | ||

| (iii) Health benefits | ||

| (iv) Attachment | ||

| Added value on the service level (1b) | (i) Improved relationship | |

| (ii) Understanding of needs | ||

| (iii) Environmental change | ||

| Added value on the political level (1c) | (i) Service priorities | |

| (ii) Policy recommendations | ||

| Unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes (2) | Individual resources required (2a) | |

| Influence uncertainty (2b) | ||

| Power differences (2c) |

3.1. Added value of public involvement processes (Main theme 1)

Added value of public involvement processes consisted of three themes which characterised the nature of added value on the individual (Theme 1a), service (Theme 1b) and political levels (Theme 1c).

3.1.1. Added value on the individual level (Theme 1a)

Added individual value concerned values generated for people engaged in involvement activities in terms of greater appreciation of and satisfaction with services and health benefits. This theme was organised into four subthemes: (i) Appreciation, (ii) Satisfaction, (iii) Health Benefits and (iv) Attachment (see Table 3). Table 5 shows quotes from the included articles illustrating added value on the individual level.

TABLE 5.

Quotes illustrating added value on the individual level

| Added value on the individual level | Quotes | References |

|---|---|---|

| Appreciation | ‘Clients appreciated being asked their opinions and feeling they had knowledge to contribute’ (Muurinen, 2019) | Diez et al. (2018), Iyer et al. (2015), Jeffery and Ervin (2011), Lamb et al. (2014), LaNoue et al. (2016), Lazenbatt et al. (2001), Munoz et al. (2013), Muurinen (2019), Myers et al. (2020), Nancarrow et al. (2004), Seim and Slettebø (2011), Timotjevic and Raats (2007), Valaitis et al. (2019), Wang (2006), Woods (2009), Yankeelov et al. (2019) |

| Satisfaction | ‘… analysis showed that community members identified some positive aspects of being involved in service co‐production relating to sense of community, empowerment and personal satisfaction.’ (Munoz et al., 2013) | Diez et al. (2018), Farmer and Nimegeer (2014), Lamb et al. (2014), LaNoue et al. (2016), Munoz et al. (2013), Muurinen (2019), Nimegeer et al. (2016), Rains and Ray (1995), Rosén (2006), Timotjevic and Raats (2007), Yankeelov et al. (2019) |

| Health benefits | ‘… benefits include opportunities to learn more about health and the health system, … greater diffusion of health knowledge in the community…’ (Lee et al., 2009) | Goold et al. (2005), Lazenbatt et al. (2001), Lee et al. (2009), Muurinen (2019), Rains and Ray (1995), Uding et al. (2009), Yankeelov et al. (2019) |

| Attachment | ‘Participants developed trust, relationships and confidence. They expressed that, by meeting service providers and managers, they felt more able to engage in constructive dialogue about services’ (Nimegeer et al., 2016) | Diez et al. (2018), Munoz et al. (2013), Muurinen (2019), Nimegeer et al. (2016), Owens et al. (2010), Yankeelov et al. (2019) |

The added individual value to the people engaged in public involvement activities were:

-

(i)

Appreciating the opportunity to express views on the development of services and feeling that service providers listened to them. Members of deprived and marginalised groups appreciated the opportunity to express their wishes for future health services and their health needs, which they were invited to rank according to their priorities.

-

(ii)

Experiencing greater satisfaction with the community health workers' provision of services. Understanding of services provided as well as appreciation of dialogue with service providers increased. During the involvement process, service users came to understand the organisation of community health services and improved understanding of the provided services thereby increasing satisfaction.

-

(iii)

Reporting benefits to health including a positive impact on mental state and capability to manage daily life. People involved felt empowered, less isolated and many experienced improved self‐esteems.

-

(iv)

Reporting a stronger sense of attachment to services and positive impacts on social life. Interaction with other people in the involvement process expanded social networks. Stronger attachment to services in which participants were actively involved as the services were being developed created a sense of ownership.

3.1.2. Added value on the service level (Theme 1b)

Added service value had three subthemes: (i) improved relationships, (ii) understanding of needs and (iii) environmental change. The subthemes concerned the added values to the relationship between the public and health service providers and the public's provision of services. In particular, value was added not only through improvements in the authorities' understanding of public needs but also led to environmental change. Table 6 shows quotes from the included articles illustrating added value on the service level.

TABLE 6.

Quotes illustrating added value on the service level

| Added value on the service level | Quotes | References |

|---|---|---|

| Improved relationship | ‘… felt comfortable expressing their point of view… partners reported that their willingness to speak and express opinions increased since they had joined …’ (Khodyakov et al. 2014) | Clark (1997), Diez et al. (2018), Khodyakov et al. (2014), Myers et al. (2020), Winter et al. (2016), Yankeelov (2019), Zani and Cicognani (2009) |

| Understanding of needs | ‘… walking through the streets, shops, parks and market making field notes and taking photographs. These field notes provided an overview of local expertise and knowledge and gave us important insights into the motivations and needs (of the citizens) …’ (Lamb et al., 2014) | Clark (1997), Crowley et al. (2002), Farmer and Nimegeer (2014), Katzburg et al. (2009), Khodyakov et al. (2014), Lamb et al. (2014), LaNoue et al. (2016), Lazenbatt et al. (2001), Lee et al. (2009), Munoz (2013), Rains and Ray (1995), Risisky et al. (2008), Timotijevic and Raats (2007), Woods (2009), Yankeelov et al. (2019), Zani and Cicognani (2009) |

| Environmental change | ‘… older adults and adolescents with little prior experience in the use of electronic tablets or advocacy strategies can be empowered … to use innovative technology to gather information about features of their neighbourhood environment that influence active living, analyse their information and identify potential solutions…’ (Winter et al., 2016) | Crowley et al. (2002), Goold et al. (2005), Lee et al. (2009), Muurinen (2019), Rains and Ray (1995), Uding et al. (2009), Winter et al. (2016), Yankeelov et al. (2019) |

Public involvement processes added value to services by improving:

-

(i)

Relationships between service users and service providers. The trustful dialogue gave the public knowledge of providers and managers of services which fostered co‐learning and affected the general public's view of services.

-

(ii)

Service providers' and managers' understanding of the needs of the public by understanding the public's views. Vulnerable and marginalised groups' participation also increased awareness of particular needs for health services and support.

-

(iii)

The communication environment between the public and authorities regarding local living conditions. The improved access to sports, leisure and cultural activities supported citizens' everyday health.

3.1.3. Added value on the political level (Theme 1c)

Two subthemes were formulated to describe added value gained on the political level: (i) service priorities and (ii) political recommendations. The subthemes illustrated the potential influence on political decisions brought by the public involvement in the development of services. Added political value concerned the influence exerted by the public on future service priorities and policy recommendations. Table 7 shows quotes from the included articles illustrating added value on the political level.

TABLE 7.

Quotes illustrating added value on the political level

| Added value on the political level | Quotes | References |

|---|---|---|

| Service priorities | ‘… selected priorities from the need assessment were addressed with elaboration and implementation of social programs’. (Zani & Cicognani, 2009) | Diez et al. (2018), Myers et al. (2020), Yankeelov et al. (2019), Zani and Cicognani (2009) |

| ‘… session provided a ranked set of the 11 policy recommendations’. (Diez et al., 2018) | ||

| Policy recommendations | ‘…participants decided to become actively involved in translating their research findings into concrete policy recommendations to improve their food/physical activity environment’. (Diez et al., 2018) | Diez et al. (2018), Myers et al. (2020), Yankeelov et al. (2019), Zani and Cicognani (2009) |

| ‘… results of the needs assessment were presented to representatives of the local government’. (Zani & Cicognani, 2009) |

The public involvement processes added political value by influencing:

-

(i)

Service priorities as a result of politicians' greater understanding of the public's priorities for health issues. This impacted the implementation of health programmes.

-

(ii)

Policy recommendations at local and regional government levels. The dialogue between residents, public health practitioners, local decision‐makers and an academic research team led to recommendations that seemed to influence politicians who expressed their clear appreciation of the involvement of these stakeholders.

3.2. Unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes (Main theme 2)

Three themes illustrating the unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes were identified: individual resources required (Theme 2a), influence uncertainty (Theme 2b) and power differences (Theme 2c). The three themes concerned potential inequalities affecting the dialogue between the public and service providers as well as among various groups representing the public which was not an expected result of the involvement process. Table 8 shows quotes from the included articles illustrating unintended negative consequences.

TABLE 8.

Quotes illustrating unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes

| Unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes | Quotes | References |

|---|---|---|

| Individual resources required | ‘Findings raise concerns about the ability of deliberative procedures to engage all citizens equally […] some vulnerable and disenfranchised groups indicate potential problems with their experiences’. (Goold et al., 2005) | Carlisle et al. (2018), Goold et al. (2005), Khodyakov et al. (2014), Munoz et al. (2013), Myers et al. (2020), Owens et al. (2010), Serapioni and Duxbury (2012), Yankeelov et al. (2019) |

| Influence uncertainty | ‘…a significant number of users’ spokespersons showed a tendency to problematise the relationship with the decision‐makers, citing the limited impact of their proposals and recommendations’ (Serapioni & Duxbury, 2012). | Gold et al. (2005), Iyer et al. (2015), Khodyakov et al. (2014), Munoz et al. (2013), Muurinen (2019), Owens et al. (2010), Serapioni and Duxbury (2012), Timotijevic and Raats (2007), Valaitis et al. (2019), Wainwright et al. (2014), Woods (2009) |

| Power differences | ‘…decision‐making power ultimately resides with the provider’. (Wainwright et al., 2014) | Farmer and Nimegeer (2014), Iyer et al. (2015), Morain et al. (2017), Munoz et al. (2013), Myers et al. (2020), Owens et al. (2010), Timotjevic and Raats (2007), Uding et al. (2009), Valaitis et al. (2019), Wainwright et al. (2014), Woods (2009), Yankeelov et al. (2019) |

3.2.1. Individual resources required (Theme 2a)

Involvement requires certain resources in terms of time, knowledge, competences, etc. Vulnerable and disenfranchised groups seemed to be particularly challenged when it came to assembling resources required for participation in the public involvement processes. The unintended negative consequences reported in the articles thus raise concerns regarding the feasibility of equal involvement of all citizens.

3.2.2. Influence uncertainty (Theme 2b)

Questioning their influence on decisions concerning future services, participants in the involvement processes expressed uncertainty as to whether their views and recommendations would be heard. They felt that their decision‐making power regarding the design of services were negligible if their preferences were deemed ‘impractical’ or ‘unaffordable’ by service providers and managers. This could have been a valid point as, although the service providers aimed to understand the users' preferences, they did not necessarily intend to use them to change their practice.

3.2.3. Power differences (Theme 2c)

The public's experience of differences in power seemed to negatively affect the involvement process by limiting participants' perceived freedom of expression. This applied to relations between involved groups and service providers as well as between different groups of people some of whom were perceived to have a stronger voice than others. This seemed to hinder more vulnerable and disenfranchised groups from voicing their opinions as they felt their preferences were often overruled by ‘expert opinion’ or by other group participants. Some voices were thus less heard than others.

4. DISCUSSION

The results of the thematic synthesis offered an overview of added value and unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes in the planning, development and implementation of community health services. The results of the thematic synthesis showed a number of positive aspects of public involvement and added value on the individual, service and political levels. The results suggest that added value seems to be accompanied by unintended negative consequences concerning level of individual resources as well as uncertainty regarding the result of people's investment in the involvement process: ‘Will my efforts matter?’ Inequality was reported in several of the included articles (Table 4). Inequality appearing in public involvement processes should be considered in future efforts and calls for special attention. 11 The articles that reported unintended consequences (see Table 4) did not mention if these consequences were caused by either public involvement process or particularly by failures in the implementation of public involvement.

Most of the articles included in this thematic synthesis reported added value on both the individual and service levels while added value of public involvement processes pertaining to the political level were reported in only 4 of the 36 articles. Nevertheless, value on the political level could offer the potential for influencing future health services. Our results complement the reviews of Haldane et al. 1 and Milton et al. 9 by contributing with an overview of added value and unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes identified in articles exploring public involvement in developing public health services. It was not possible to draw a causal connection between a specific public involvement activity used in the included articles and added value or unintended negative consequences. This result is in line with Draper et al. 8 and argues that added value of public involvement must be seen as a result of the process.

The identified themes show the interconnectedness of the added value of public involvement processes across predefined levels. During public involvement activities covered in the articles included in this thematic synthesis, the public was invited to voice opinions and share individual experiences which resulted in adding both individual and service values. This is in contrast to the values on a political level which were found to be limited. Information sharing and comprehensive dialogue before making decisions are traditionally seen as cornerstones of deliberative involvement processes 58 which have the potential to maximise mutual learning of all involved groups. 59 Public involvement thus allows for knowledge exchange between participants although this does not necessarily lead to guaranteed outcomes. If successful, public involvement could bring about changes in policies which, in the long run, could lead to improved services in the public's perspective.

In addition to empowering the public at the community level, involvement of the public rooted in democratic ideals emphasises the importance of influence on the decision‐making processes. 7 Such democratic ideals may foster change on multiple levels by stimulating interaction among individuals, local communities and service providers. 7 Valaitis et al. 35 have found that added value of public involvement applies at both individual and service levels. Our study contributes by showing that a certain level of individual resources is necessary, that many feel uncertain about the real effects on the policy and that challenges relating to power inequality exist. All of these factors seem to discourage some groups from getting involved which could lead to even greater inequality regarding public involvement in developing community health services.

Our findings bring into question the widely held assumption that public involvement is solely associated with positive aspects. We identified possible negative consequences which is a topic not often addressed in the literature. This was particularly seen in relation to involvement of less resourceful and vulnerable groups. This lack of representatives points to challenges regarding whether all voices are heard. Leaving vulnerable groups without influence on decision‐making processes and not empowering them with necessary competences and resources could lead to even greater inequality in health. 6 Boivin et al. 58 maintain that such unintended negative consequences can be alleviated by offering preparation courses to stimulate and empower people's communication skills.

As a strategy to achieve democratisation of knowledge and prevention of health inequalities, a socio‐ecological approach to public involvement could be helpful and should include voices of users who are hardly ever heard or are hard to reach regarding their services needs. 60 This socio‐ecological approach to public involvement could be an alternative to the more dominant consumerist approach used in the improvement of services. 7 , 61 In line with the socio‐ecological approach, Butterfoss et al. 62 propose that individual, community, organisational and societal factors be considered in the planning of health promotion interventions. By highlighting unintended negative consequences on both individual and service levels, our findings reveal asymmetric relations caused mainly by disadvantageous public involvement processes and lack of success in involving participants equally. 6 , 7 Aiming to involve the public in service development thus leaves us with great challenges in our attempts to fight inequity in public involvement.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

In the systematic literature search conducted in Part 1 of the scoping review, 12 we identified 36 articles reporting added value and unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes. The present thematic synthesis was a relevant method for providing an overview of added value and unintended negative consequences of public involvement in the planning, development and implementation of community health services. In our assessment of relevance, 20 , 21 none of the identified articles were excluded although some were deemed insufficient in their reporting of added value and/or unintended negative consequences. The lack of quality in the included articles reporting added value and unintended consequences has to be considered as high‐quality evaluation studies are needed. The scarcity of included articles which systematically evaluated the process of public involvement 22 , 24 , 33 , 34 , 45 , 47 , 57 led us to include articles with different study designs. This decision offered us insights into a wide range of added values and unintended negative consequences associated with public involvement processes although we did not form categories about the type of public involvement and type of community health service which is a limitation of this study. The inclusion of articles that did not systematically evaluate public involvement could also be viewed as a limitation.

4.2. Implications for practice and research

Significant value from involving the public in the planning, development, and implementation of community health services has been reported, highlighting the importance of public involvement. The way in which public involvement processes are facilitated seem to have an impact on the added value to individual, service and political levels. Examples include methods used to investigate the public's views as well as opinions and facilitation of how consensus is achieved. Service providers' and politicians' interpretation of the results of the public involvement process could also influence the added value on the service and political levels. Professionals conducting public involvement activities need training to better the facilitation process. 58 This could come by, for example, using deliberative techniques, 48 rapid appraisal techniques 16 or nominal group techniques. 63

The strategies used in recruiting participants for public involvement activities may not only influence added value but also have unintended negative consequences. 64 Attention to recruitment strategies to ensure equal opportunities for participation are key to giving vulnerable groups the opportunity for equal participation in the involvement processes.

The majority of the included articles were characterised by poor detailing of methods used to secure involvement and assessment of added value. Of the included articles, only seven had evaluations of the added value of public involvement as their primary aim. Hence, our findings demonstrate that evaluation of the effect and contextual factors' influence on public involvement is sparse. This finding corroborates the findings of Evans et al. 65 although their study focuses on public involvement within a research context. Our findings are in line with Rifkin, 3 Draper et al. 8 and Minkler & Wallerstein 6 and support the argument that qualitative evaluation designs could offer better insight into a range of important added value and unintended consequences of public involvement processes not yet reported in the literature.

5. CONCLUSION

This thematic synthesis has generated knowledge on the added value of public involvement processes and pertains to several levels of value which have been primarily reported to be added at the individual and service levels. Reported added value from public involvement processes seems to be accompanied by unintended negative consequences that may be generated from the way the involvement process is carried out in practice, how recruitment of participants is done and how facilitation of the involvement process is performed. Despite the positive aspects of public involvement processes in developing community health services, risk of unintended negative consequences should always be considered. This is especially true if needs and wishes expressed by the public or certain vulnerable groups are not considered by politicians and service providers in charge of services. Involving less resourceful groups in the involvement processes and improving training of professionals to facilitate involvement processes is needed. Balancing the pros and cons of public involvement processes in practice will continue to pose challenges as the call for public involvement grows. As we strive to involve the public in all phases of the service development process, more awareness of unintended negative aspects of public involvement is required. Future process evaluations of public involvement processes could help explore not only positive aspects of the involvement process but also potential negative consequences.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There is no conflict of interest to disclose.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material 1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Jette Thise Pedersen (Librarian RSLIS, Research Librarian), Mette Buje Grundsøe (MLISc) and Sabine Dreier (MLISc, Aalborg University Library) for contributing with expert knowledge and support. A research grant received from Aalborg Municipality (Denmark) is gratefully acknowledged. This review was funded by a grant from Aalborg Municipality (Denmark) and Aalborg University (Denmark). Funders and stakeholders had no role in the study design, data analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Pedersen JF, Overgaard C, Egilstrød B, Petersen KS. The added value and unintended negative consequences of public involvement processes in the planning, development and implementation of community health services: results from a thematic synthesis. Int J Health Plann Mgmt. 2022;37(6):3250‐3268. 10.1002/hpm.3553

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Haldane V, Chuah FLH, Srivastava A, et al. Community participation in health services development, implementation, and evaluation: a systematic review of empowerment, health, community, and process outcomes. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):1‐25. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mockford C, Staniszewska S, Griffiths F, Herron‐Marx S. The impact of patient and public involvement on UK NHS health care: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(1):28‐38. 10.1093/intqhc/mzr066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rifkin SB. Examining the links between community participation and health outcomes: a review of the literature. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(suppl 2):ii98‐ii106. 10.1093/heapol/czu076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coulter A. Patient engagement—what works? J Ambul Care Manag. 2012;35(2):80‐89. 10.1097/JAC.0b013e318249e0fd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bath J, Wakerman J. Impact of community participation in primary health care: what is the evidence? Aust J Prim Health. 2015;21(1):2‐8. 10.1071/PY12164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Introduction to community‐based participatory research. New issues and emphases. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community Based Participatory Research for Health: Process to Outcomes. 2nd ed. Jossey‐Bass; 2008:5‐24. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ocloo J, Matthews R. From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(8):626‐632. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Draper AK, Hewitt G, Rifkin S. Chasing the dragon: developing indicators for the assessment of community participation in health programmes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(6):1102‐1109. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Milton B, Attree P, French B, Povall S, Whitehead M, Popay J. The impact of community engagement on health and social outcomes: a systematic review. Community Dev J. 2012;47(3):316‐334. 10.1093/cdj/bsr043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Attree P, French B, Milton B, Povall S, Whitehead M, Popay J. The experience of community engagement for individuals: a rapid review of evidence: experience of community engagement: a review. Health Soc Care Community. 2011;19(3):250‐260. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00976.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Staniszewska S, Brett J, Mockford C, Barber R. The GRIPP checklist: strengthening the quality of patient and public involvement reporting in research. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27(4):391‐399. 10.1017/S0266462311000481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pedersen JF, Egilstrød B, Overgaard C, Petersen KS. Public involvement in the planning, development, and implementation of community health services: a scoping review of public involvement methods. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;30(3):809‐835. 10.1111/hsc.13528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19‐32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141‐146. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rowa‐Dewar N, Ager W, Ryan K, Hargan I, Hubbard G, Kearney N. Using a rapid appraisal approach in a nationwide, multisite public involvement study in Scotland. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(6):863‐869. 10.1177/1049732308318735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Green S, Considine R, Parkinson L, Bonevski B. Community health needs assessment for health service planning: realising consumer participation in the health service setting. Health Promot J Aust. 2004;15(2):142‐150. 10.1071/HE04142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Velonis AJ, Molnar A, Lee‐Foon N, Rahim A, Boushel M, O'Campo P. “One program that could improve health in this neighbourhood is ____?” using concept mapping to engage communities as part of a health and human services needs assessment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(150):1‐12. 10.1186/s12913-018-2936-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. QSR International . NviVo; 2015:11.

- 20. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Movsisyan A, Arnold L, Evans R, et al. Adapting evidence‐informed complex population health interventions for new contexts: a systematic review of guidance. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):1‐105. 10.1186/s13012-019-0956-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carlisle K, Farmer J, Taylor J, Larkins S, Evans R. Evaluating community participation: a comparison of participatory approaches in the planning and implementation of new primary health‐care services in northern Australia. Int J Health Plan Manag. 2018;33(3):704‐722. 10.1002/hpm.2523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Díez J, Gullón P, Sandín Vázquez M, et al. A community‐driven approach to generate urban policy recommendations for obesity prevention. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2018;15(4):1‐15. 10.3390/ijerph15040635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goold SD, Biddle AK, Klipp G, Hall CN, Danios M. Choosing healthplans all together: a deliberative exercise for allocating limited health care resources. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2005;30(4):563‐601. 10.1215/03616878-30-4-563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khodyakov D, Sharif M, Dixon E, et al. An implementation evaluation of the community engagement and planning intervention in the CPIC depression care improvement trial. Community Ment Health J. 2014;50(3):312‐324. 10.1007/s10597-012-9586-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lazenbatt A, Lynch U, O'Neill E. Revealing the hidden ‘troubles’ in Northern Ireland: the role of participatory rapid appraisal. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(5):567‐578. 10.1093/her/16.5.567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Munoz S. Co‐producing care services in rural areas. J Integrated Care. 2013;21(5):276‐287. 10.1108/JICA-05-2013-0014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Muurinen H. Service‐user participation in developing social services: applying the experiment‐driven approach. Eur J Soc Work. 2019;22(6):961‐973. 10.1080/13691457.2018.1461071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Myers CD, Kieffer EC, Fendrick AM, et al. How would low‐income communities prioritize medicaid spending? J Health Polit Policy Law. 2020;45(3):373‐418. 10.1215/03616878-8161024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rains JW, Ray DW. Participatory action research for community health promotion. Publ Health Nurs. 1995;12(4):256‐261. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1995.tb00145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rosén P. Public dialogue on healthcare prioritisation. Health Policy. 2006;79(1):107‐116. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Seim S, Slettebø T. Collective participation in child protection services: partnership or tokenism? Eur J Soc Work. 2011;14(4):497‐512. 10.1080/13691457.2010.500477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Serapioni M, Duxbury N. Citizens' participation in the Italian health‐care system: the experience of the Mixed Advisory Committees. Health Expect. 2012;17(4):488‐499. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00775.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Timotijevic L, Raats MM. Evaluation of two methods of deliberative participation of older people in food‐policy development. Health Policy. 2007;82(3):302‐319. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Valaitis R, Longaphy J, Ploeg J, et al. Health TAPESTRY: co‐designing interprofessional primary care programs for older adults using the persona‐scenario method. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):1‐11. 10.1186/s12875-019-1013-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Winter S, Goldman Rosas L, Padilla Romero P, et al. Using citizen scientists to gather, analyze, and disseminate information about neighborhood features that affect active living. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18(5):1126‐1138. 10.1007/s10903-015-0241-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Woods VD. African American Health Initiative Planning Project: a social ecological approach utilizing community‐based participatory research methods. J Black Psychol. 2009;35(2):247‐270. 10.1177/0095798409333589 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yankeelov PA, Faul AC, D'Ambrosio JG, Gordon BA, McGeeney TJ. World cafés create healthier communities for rural, older adults living with diabetes. Health Promot Pract. 2019;20(2):223‐230. 10.1177/1524839918760558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Clark A. Community participation in determining the needs of users and carers of rural community care services. Health Bull. 1997;55(5):305‐308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Crowley P, Green J, Freake D, Drinkwater C. Primary care trusts involving the community. Is community development the way forward? J Manag Med. 2002;16(4):311‐322. 10.1108/02689230210445121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Farmer J, Nimegeer A. Community participation to design rural primary healthcare services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):1‐10. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Iyer SP, Pancake LS, Dandino ES, Wells KB. Consumer‐involved participatory research to address general medical health and wellness in a community mental health setting. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(12):1268‐1270. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jeffery V, Ervin K. Responding to rural health needs through community participation: addressing the concerns of children and young adults. Aust J Prim Health. 2011;17(2):125‐130. 10.1071/PY10050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Katzburg JR, Yano EM, Washington DL, et al. Combining women's preferences and expert advice to design a tailored smoking cessation program. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44(14):2114‐2137. 10.3109/10826080902858433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lamb J, Dowrick C, Burroughs H, et al. Community engagement in a complex intervention to improve access to primary mental health care for hard‐to‐reach groups. Health Expect. 2014;18(6):2865‐2879. 10.1111/hex.12272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. LaNoue M, Mills G, Cunningham A, Sharbaugh A. Concept mapping as a method to engage patients in clinical quality improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(4):370‐376. 10.1370/afm.1929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee SK, Thompson SC, Amorin‐Woods D. One service, many voices: enhancing consumer participation in a primary health service for multicultural women. Qual Prim Care. 2009;17(1):63‐69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Morain S, Whicher D, Kass N, Faden R. Deliberative engagement methods for patient‐centered outcomes research. Patient – Patient‐Centered Outcomes Res. 2017;10(5):545‐552. 10.1007/s40271-017-0238-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nancarrow S, Johns A, Vernon W. ‘The squeaky wheel gets the grease’: a case study of service user engagement in service development. J Integrated Care. 2004;12(6):14‐21. 10.1108/14769018200400044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nimegeer A, Farmer J, Munoz SA, Currie M. Community participation for rural healthcare design: description and critique of a method. Health Soc Care Community. 2016;24(2):175‐183. 10.1111/hsc.12196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Owens C, Farrand P, Darvill R, Emmens T, Hewis E, Aitken P. Involving service users in intervention design: a participatory approach to developing a text‐messaging intervention to reduce repetition of self‐harm. Health Expect. 2010;14(3):285‐295. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00623.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Risisky D, Hogan VK, Kane M, Burt B, Dove C, Payton M. Concept mapping as a tool to engage a community in health disparity identification. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(1):77‐83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Twible RL. Consumer participation in planning health promotion programmes: a case study using the nominal group technique. Aust Occup Ther J. 1992;39(2):13‐18. 10.1111/j.1440-1630.1992.tb01741.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Uding N, Kieckhefer GM, Trahms CM. Parent and community participation in program design. Clin Nurs Res. 2009;18(1):68‐79. 10.1177/1054773808330096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wainwright D, Boichat C, McCracken LM. Using the nominal group technique to engage people with chronic pain in health service development. Int J Health Plan Manag. 2014;29(1):52‐69. 10.1002/hpm.2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang C. Youth participation in photovoice as a strategy for community change. J Community Pract. 2006;14(1–2):147‐161. 10.1300/J125v14n01_09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zani B, Cicognani E. Evaluating the participatory process in a community‐based health promotion project. J Prev Interv Community. 2009;38(1):55‐69. 10.1080/10852350903393459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Boivin A, Lehoux P, Burgers J, Grol R. What are the key ingredients for effective public involvement in health care improvement and policy decisions? A randomized trial process evaluation. Milbank Q. 2014;92(2):319‐350. 10.1111/1468-0009.12060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lehoux P, Daudelin G, Demers‐Payette O, Boivin A. Fostering deliberations about health innovation: what do we want to know from publics? Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(11):2002‐2009. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kastelic SL, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG. Socio‐ecologic framework for CBPR. Development and testing of a model. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community Based Participatory Research for Health: Process to Outcomes. 2nd ed. Jossey‐Bass; 2008:77‐93. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pestoff V. Co‐production at the crossroads of public administration regimes: what role for users, providers and the third sector. In: Osborne SP, ed. Co‐production and Public Service Management. Routledge; 2019:127‐139. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Butterfoss FD, Kegler MC, Francisco VT. Mobilizing organizations for health promotion: theories of organizational change. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. Jossey‐Bass; 2008:335‐361. [Google Scholar]

- 63. McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(3):655‐662. 10.1007/s11096-016-0257-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cyril S, Smith BJ, Possamai‐Inesedy A, Renzaho AMN. Exploring the role of community engagement in improving the health of disadvantaged populations: a systematic review. Glob Health Action. 2015;8(1):1‐12. 10.3402/gha.v8.29842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Evans D, Pilkington P, McEachran M. Rhetoric or reality? A systematic review of the impact of participatory approaches by UK public health units on health and social outcomes. J Public Health. 2010;32(3):418‐426. 10.1093/pubmed/fdq014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.