Abstract

Introduction.

Women with genitourinary pain, a hallmark symptom of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome (IC/BPS), are at a two-to four-fold risk for depression as compared to women without genitourinary pain. Despite the pervasive impact of IC/BPS on psychological health, there is a paucity of empirical research on understanding the relation between IC/BPS and psychological distress. It has been previously reported that women with overactive bladder use increased compensatory coping and these behaviors are associated with heightened anxiety and stress. However, it is unknown whether a similar pattern emerges in IC/BPS populations, as ICBPS and OAB share many similar urinary symptoms. The current study examined the relationship between compensatory coping behaviors and symptoms of psychological distress in a sample of women with IC/BPS to inform understanding of risk and potential mechanisms for intervention.

Method.

This was a secondary analysis of an observational cohort of women with bladder symptoms. Fifty-five adult women with IC/BPS completed validated assessments of genitourinary symptoms, emotional distress, and bladder coping behaviors. Five compensatory coping behaviors were summed to create a total Bladder Coping Score. Linear regression examined associations between individual coping behaviors, total compensatory coping scores, and other risk variables.

Results.

Most (93%) participants reported use of at least one compensatory coping behavior. Age, education level, history of vaginal birth, and symptom severity were all associated with greater compensatory coping scores, and anxiety was not. Beyond the influence of symptom severity, higher levels of depression were significantly associated with higher compensatory coping scores.

Discussion.

Greater compensatory coping was associated with increased depression but not anxiety, suggesting different profiles of coping and psychological distress may exist among different types of bladder dysfunction.

Introduction

Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome (IC/BPS) affects between 3 and 6% of women in the United States.1 Hallmark symptoms of IC/BPS include pelvic pain, urinary urgency, bladder pressure or discomfort, and urinary frequency.2 Symptoms of IC/BPS drastically decrease quality of life.3 IC/BPS can impair both physical and emotional functioning and this, in turn, often leads to lifestyle adjustments in occupational, social, and family roles.4 Depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation occur at high rates in IC/BPS.5,6

Qualitative evidence provides insight into patients’ experience of living with IC/BPS. In one study, focus groups consistently reported that medication only partially (if at all) treated their IC/BPS symptoms and they required the use of myriad strategies to address and cope with symptoms.4 Further, patients reported self-blame and self-responsibility for managing symptoms, and an understanding that self-reliance is required in the management of bladder disorders.7 Examples of compensatory coping strategies identified in people with overactive bladder, which shares many of the same bladder symptoms as ICBPS, include wearing pads, restricting fluid intake, and altering daily activities based on proximity to available restrooms.8

While the use of some coping strategies may be practical and even adaptive for patients with bladder disorders, over-reliance on these strategies can negatively impact quality of life and exacerbate symptoms.8 Daily and colleagues found that toileting behaviors such as convenience voiding (urinating without urge) relate to overactive bladder symptoms.9 Convenience voiding might represent a maladaptive coping behavior in which OAB patients feel compelled to empty the bladder without urge in order to prevent urgency episodes, but exacerbate OAB symptoms by sensitizing the bladder to empty at smaller volumes.

The cognitive effort involved in employing many coping strategies can be emotionally taxing for IC/BPS patients, and dependence on such coping strategies can negatively affect patients’ social lives.4 Further, many IC/BPS and OAB patients experience heightened anxiety in response to urinary urgency triggers, such as unlocking the door to one’s home. They subsequently employ coping strategies aimed at reducing this anxiety. Through alleviating anxiety related to urgency triggers, these strategies reinforce and perpetuate compensatory coping behaviors, even if they are not actually helpful in managing urinary urgency symptoms.8

The current study sought to examine the relation between compensatory bladder coping behaviors and mood and anxiety symptoms in a sample of women with IC/BPS, hypothesizing a pattern similar to the relation found in women with OAB: a positive association between increased use of bladder coping and psychological distress.

Methods

This study is a secondary analysis of data collected from women with bladder problems recruited between 2014 and 2019 to undergo clinical phenotyping and mechanistic studies.10 Criteria for inclusion in this analysis included a diagnosis of interstitial cystitis, either diagnosed by the principal investigator (W.S.R) using the AUA criteria (n = 8) or either definite (n = 44) or likely (n = 3) interstitial cystitis using RICE criteria.11,1 Exclusion criteria included diagnosis of neurologic conditions that might contribute to urinary symptoms (e.g., spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, stroke, autonomic dysfunction); history of bladder cancer, pelvic irradiation, or bowel diversions; and inability or unwillingness to complete all study protocols.8 Fifty-five women met all study criteria.

Participants completed the RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology (RICE) scale using sensitivity criteria for study inclusion.1 This identification technique shows 81% specificity in identifying patients with IC/BPS.1 The Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms questionnaire (B-FLUTS) was used to assess 12 symptoms of filling, voiding, and urinary incontinence with five-point scales.12

Compensatory bladder behaviors were assessed using five items from the OAB quality of life questionnaire (OABq-QOL).13,8 Compensatory behaviors are those that entail patient modification of daily activities in order to address bladder behaviors, compensating for abnormal function.

The OABq-QOL assesses five behaviors: always locating the nearest restroom, planning escape routes to restrooms, avoiding activities away from restrooms, decreasing physical activity to avoid bladder problems, and addressing discomfort when traveling with others. Participants indicated frequency of each behavior using a six-point scale (“1, none of the time” to “6, all of the time”) in response to the stem “In the past 7 days, how often have your bladder symptoms…”. A total Compensatory Coping score was generated by summing these five variables (range 6 – 30). A higher score represents greater compensatory coping burden and greater negative quality of life impact.

Participants completed Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) subscales for anxiety and depression.14 The PROMIS Anxiety and Depression scales each consist of eight items asking about specific symptoms related to anxiety or depression within the past week using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely). Total raw scores for each scale are summed and can range from 8 to 40, which convert to standardized scores following a normal distribution, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity.

Statistical analysis.

We hypothesized that greater use of compensatory coping behaviors would be significantly associated with greater psychological distress as evidenced by higher anxiety and depression symptom scores. For preliminary inspection, we examined demographic and clinical variables in relation to urologic and psychological variables using Spearman and Pearson correlations, and examined use of compensatory coping strategies by inspecting frequency and percentages. To address study hypotheses, linear regression examined associations between individual coping behaviors, total compensatory coping scores, bladder symptoms, and demographic variables. For these primary analyses, our independent variables were coping scores and our dependent variable was psychological distress (anxiety or depression symptoms). Finally, we used individual multivariable linear regression models for anxiety and depression, controlling for clinical variables identified as potential confounding variables via correlation. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 27.15

Results

Fifty-five women met inclusion criteria and comprised the study sample. The median age for the sample was 55.05 (SD 14.97) years. Table 1 displays all other demographic and clinical data for the subjects.

Table 1:

Study Participant Characteristics

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age years | 45.05 (14.97) |

| Race (May select more than one) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 44 (80%) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 9 (16.5%) |

| Asian | 2 (3.6%) |

| Hispanic | 2 (3.6%) |

| At least one vaginal birth | 28 (50.9%) |

| Education | |

| High school | 4 (7.3%) |

| Partial college | 17 (30.9%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 15 (27.3%) |

| Graduate or professional degree | 19 (34.5%) |

| Relationship status | |

| Single | 18 (32.7%) |

| Partnered | 24 (43.6%) |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 13 (23.6%) |

| PROMIS Depression (t score) | 47.73 (9.48) |

| PROMIS Anxiety (t score) | 52.65 (10.07 |

| ICIQ FLUTS Total Score | 19.81 (8.22) |

| Coping score (range: 0–5) | 3.65 (1.54) |

Note.

Bivariate correlations on all study variables are presented in Table 2. Participant age, marital/partnership status, and history of vaginal birth all positively related to both bladder symptom severity and use of coping behaviors. No demographic or clinical study variables related to symptoms of either depression or anxiety.

Table 2.

Correlations among study variables

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | −0.099 | 0.109 | .543** | −0.199 | −.519** | .525** | 0.142 | −0.099 | .400** |

| 2. Hispanic/Latinx | 1 | 0.097 | −0.101 | 0.121 | 0.004 | −0.068 | −0.086 | −0.093 | −0.146 |

| 3. Race | 0.097 | 1 | 0.236 | 0.252 | 0.036 | −0.029 | 0.191 | 0.167 | −0.112 |

| 4. Marital Status | −0.101 | 0.236 | 1 | 0.036 | −.453** | .325* | 0.149 | 0.023 | 0.264 |

| 5. Highest Educ. | 0.121 | 0.252 | 0.036 | 1 | 0.196 | −.352** | −0.200 | −0.035 | −.309* |

| 6. Vaginal Birth | 0.004 | 0.036 | .453** | 0.196 | 1 | .456** | −0.074 | 0.040 | .347* |

| 7. FLUTS Score | −0.068 | −0.029 | .325* | −.352** | −.456** | 1 | 0.144 | 0.066 | .670** |

| 8. Depression | −0.086 | 0.191 | 0.149 | −0.200 | −0.074 | 0.144 | 1 | .711** | .354** |

| 9. Anxiety | −0.093 | 0.167 | 0.023 | −0.035 | 0.040 | 0.066 | .711** | 1 | 0.203 |

| 10. Coping | −0.146 | −0.112 | 0.264 | −.309* | −.347** | .670** | .354** | 0.203 | 1 |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Figure 1 displays breakdown of individual coping behavior frequencies, with more than 92% of participants reporting frequently locating the nearest restroom or planning escapes from social situations when outside the home. Further, 70% of participants reported coping with significant discomfort when traveling or decreasing their physical activity to cope with bladder distress, and more than two-thirds of participants reporting that they avoid activities away from restrooms altogether.

Figure 1.

Frequency of coping skill endorsement

Table 3 displays linear regression coefficients for study variables predicting depressive symptoms. Even when controlling for participant age, education, prior vaginal births, and most importantly, urinary symptoms, depressive symptoms positively predicted use of compensatory coping, t(52) = 2.33, p = .024. After controlling for demographic variables and urinary symptoms, anxiety was not significantly related to compensatory coping, t(52) = 1.310, p = .142, (results presented in Table 4).

Table 3.

Linear Regression Predicting PROMS Depression Scores

| Predictor | B | SE B | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age | .029 | .075 | .063 | .711 |

| Education | −.965 | .984 | −.142 | .332 |

| Vaginal birth | .730 | 2.22 | .053 | .744 |

| ICIQ-FLUTS Score | −.168 | .173 | −.199 | .336 |

| Number of Coping Strategies | 1.921 | .824 | .425 | .024 |

Table 4.

Linear Regression Predicting PROMIS Anxiety Scores

| Predictor | B | SE B | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age | −.102 | .083 | −.214 | .227 |

| Education | −.086 | 1.05 | −.012 | .935 |

| Vaginal birth | .792 | 2.37 | .056 | .739 |

| ICIQ-FLUTS Score | .009 | .184 | .010 | .961 |

| Number of Coping Strategies | 1.31 | .877 | .282 | .142 |

Discussion

This study provides insight into how individuals with IC/BPS cope with symptoms, and the relationship between coping and psychological distress. Results indicate that compensatory coping behaviors demonstrate unique relationships with symptoms of depression and anxiety in IC/BPS patients. Several novel findings emerged from study analyses. We identified a high use of all compensatory coping strategies assessed, with most participants reporting use of at least one of these behaviors. Further, use of coping strategies related to greater symptoms of depression, but not anxiety.

Participants reported using numerous coping strategies to alleviate or prevent distress related to pain or urinary urgency. Often, coping strategies couple together. For example, someone who employs one strategy to alleviate distress (e.g. locating the nearest restroom) might feel compelled to employ a preventative strategy (e.g. avoiding activities far away from a restroom) if they perceive risk that the alleviating strategy will not be available. Further, if an individual experiences a reduction in distress after using one coping strategy, they may be more likely to subsequently utilize additional strategies.

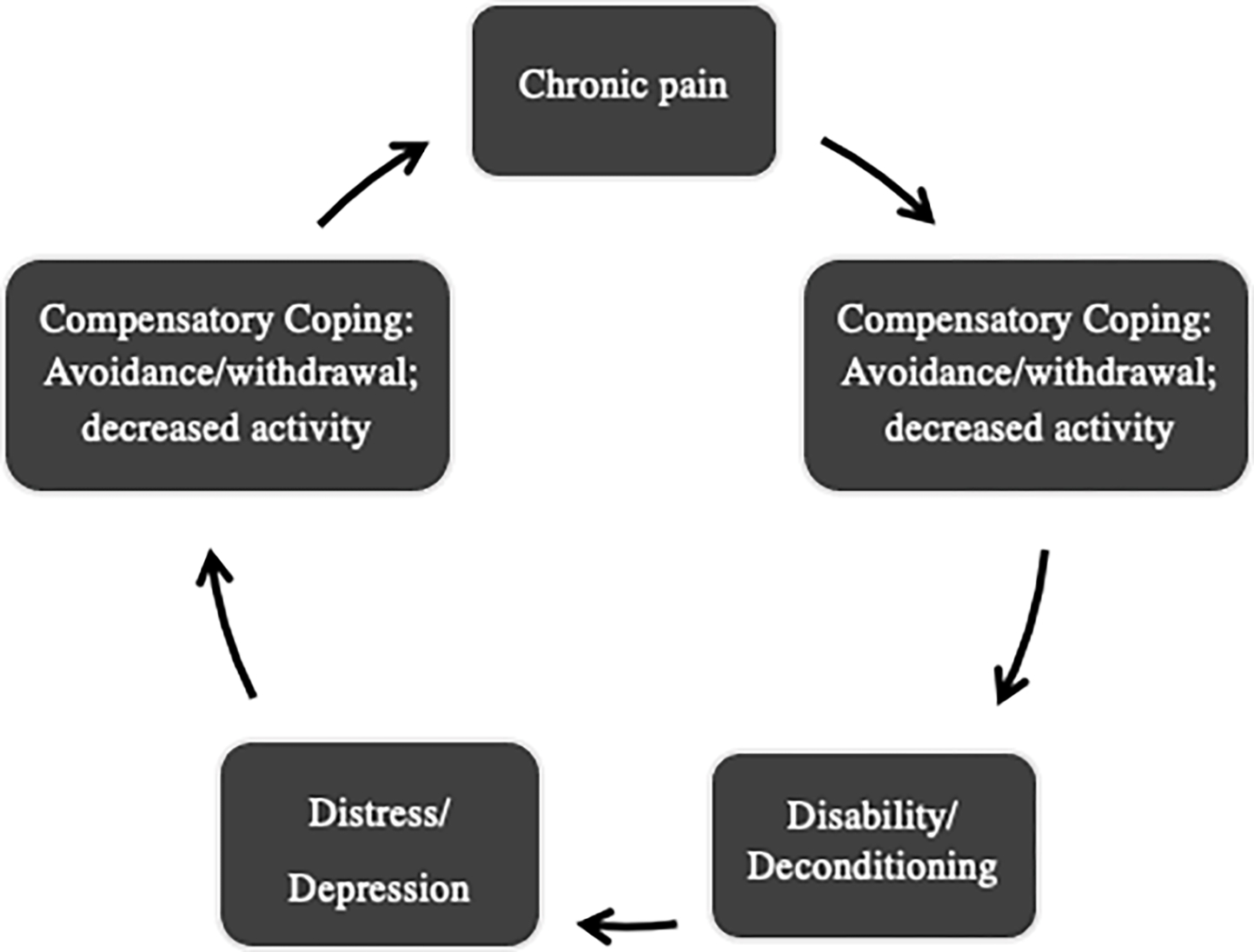

The current research on bladder coping adds to a rich literature that details theories of compensatory coping behaviors related to distress more broadly. While not previously examined in the context of urinary symptoms, a well-validated three-factor structure of responses to physical or emotional stress has been identified and replicated in populations experiencing primary pain and with pain-specific coping measures.16,17 This model (Figure 2) describes the following three factors: primary control or active coping (e.g. problem-solving), secondary control or accommodative coping (e.g. cognitive reappraisal, acceptance, or healthy distraction), and disengagement or passive coping (e.g. avoidance of stressful stimuli or withdrawal). Generally, primary and secondary control coping represent adaptive techniques and better psychological functioning. Disengagement, or passive coping includes maladaptive techniques that relates to poorer psychological functioning.16

Figure 2.

Three-factor model of psychosocial coping; proposed IC/BPS coping

Qualitative work indicates that IC/BPS patients report coping strategies that fall within all three factors, including primary or active coping via problem-solving symptom management (e.g. diet restriction and pelvic floor physical therapy) or self-advocacy (see Figure 2). Although less frequently reported, secondary/accommodative coping included cognitive strategies to cope with emotional distress, such as gratitude for support and treatment. Finally, examples of reported passive/disengaged coping include social isolation or abstinence from sexual activity, and may closely relate to and include the compensatory coping strategies examined in the current study.4

Maladaptive or disengaged coping strategies provide immediate reinforcement by amelioration of uncomfortable feelings or situations through withdrawal or avoidance. Thus, individuals reduce initial negative emotions by withdrawing from or avoiding unpleasant situations rather than working to either improve the unpleasant situations or accept them. This process becomes maladaptive via operant learning, by removing positive experiences that naturally accompany distressing experiences (e.g. positive social interactions coupled with urinary distress when away from the home). This reinforces long-term psychological distress, and losing confidence in coping abilities outside of immediate disengagement.17,8 Figure 3 displays a proposed conceptual model incorporating extant understanding of these psychological processes applied to IC/BPS. While principal pain pathology may primarily be linear, proposed understandings of chronic pain point more to a cyclic understanding of pain, whereby initial biological experiences of pain may elicit maladaptive cognitive and behavioral responses, which ultimately maintain or exacerbate the original biological experiences of pain.18,19 Thus, a person’s biological symptoms, social environment, psychological reactions to, and coping with IC/BPS symptoms all influence pain experiencing and serve as potential opportunities to interrupt the pain cycle through intervention.

Figure 3.

Proposed IC/BPS Compensatory Coping Cycle

The present findings suggest that women with IC/BPS may be at risk for different types of psychological distress. Women with IC/BPS may demonstrate distinct patterns of coping behavior from women with urinary symptoms alone, as the experience of and reactions to stress may be different in IC/BPS patients.

Previous quantitative examination identified clear evidence for risk of anxiety and potential evidence for symptoms of depression in women with OAB related to use of compensatory coping; however, only elevation of depression presented in this sample.8 This is not surprising, given existing research indicating over a third of women with IC/BPS meet criteria for probable depressive disorder.4, 20 The primary distinction between OAB and IC/BPS is pain, and therefore results suggest that coping behaviors may function differently in the context of pain.

As hallmark symptoms of OAB include frequent urination and bladder incontinence, OAB may require increased hypervigilance or worry about the future or promote feelings of agitation or restlessness. In contrast, pain may impact hopelessness, anhedonia, lack of energy, or even the sense that life is no longer worth living.21 Previous research suggests that the effects of negative coping strategies may be more pronounced for individuals with depression,3 and that depression can worsen the perception of pain.21,22 Depression may affect a person’s ability to effectively cope, as people with depression may be more likely to perceive coping as ineffective and less likely to start or maintain new habits while also struggling to identify hope and their own incremental successes.

Potential moderators of the relationship between compensatory behaviors and psychological functioning include frequency of behavior (low vs. high), and duration of high-frequency use of behavior (short vs. long-term).

There is a potential curvilinear relationship between level of cognitive arousal or coping and psychological health. At some level, planning or awareness of surroundings is adaptive for those with unpredictable urinary symptoms. Identification of a nearby restroom or planned proximity to restrooms may facilitate access to social or mood-boosting activities outside of the home. However, as frequency of this planning becomes repetitive or ruminative, returns may diminish, such that excessive cognitive planning impedes social engagement, pleasure, or mindful participation in activities.

Similarly, the initial implementation of these strategies serve to support the newly-symptomatic or diagnosed. Learning to quickly locate restroom options or to rehearse a route or excuse for a planned escape upon exposure to a trigger or escalation of pain might work well in the short-term. However, long-term use may contribute to cognitive burden and perpetuate stress, and prolonged stress can exacerbate physical health problems, including but not limited to potential problems with the cardiovascular, metabolic, immune, and CNS systems.4,23

Using a variety of coping strategies can contribute to mental and physical fatigue, as they often require a great deal of forethought and can prohibit certain activities with family and friends due to activity restriction. Therefore, a struggling patient may need to reconsider the appropriate balance of engagement and self-management that does not further detract from their quality of life.

Strengths and Limitations

There are a number of strengths of this study. Among one of the first studies to examine coping with bladder symptoms in IC/BPS, the present study provides additional insight into a greatly understudied condition. A more nuanced understanding of the relation between biological and psychosocial factors in IC/BPS is necessary.5 The current study utilized well-validated measures of urinary symptoms, depression, and anxiety. Further, the current study expanded upon the extant literature examining the incidence of psychological disorders in a bladder sample by including a relatively novel measure of compensatory bladder coping not previously used in a urological pain sample.8

Current analyses were limited to cross-sectional data of a modestly-sized sample of all women. Research indicates that the condition may be underdiagnosed in males and both prevalence rates of the condition and associations between symptom profiles in males might be similar to those of females.24,25 Future research should include both males and females to assess for sex differences in relations between symptom profiles, compensatory coping and psychological distress in the context of IC/BPS.25

Future studies should also consider the difference between adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies in the context of LUTS and pelvic pain and their relationship with overall functioning and quality of life. For instance, some evidence supports the use of more adaptive, or positive, coping strategies, and how these techniques might be combined with strategies for reducing bladder compensatory coping is currently understudied.3 We may also want to understand how specific symptoms of depression such as hopelessness or catastrophizing may drive coping. As in the broader coping literature, it is likely that various coping strategies are more or less adaptive, but a two- or three-factor structure has not yet been fully examined in the urological literature. Such a structure may provide a basis for examining appropriateness and efficacy of other coping strategies and treatment targets, such as cognitive behavioral techniques or acceptance and commitment therapy.

Conclusion

In sum, greater use of compensatory coping behaviors related to increased symptoms of depression, even after controlling for level of bladder impairment. However, this association was not present for symptoms of anxiety. These findings have implications for identification of patients at high risk for problematic coping, the development of targeted prevention programs, and more nuanced treatment of the IC/BPS population. Understanding the mechanisms of coping and their relation to specific symptoms of psychopathology may pave a path for directed discussion on a stigmatized topic within IC/BPS patients.

Acknowledgments

All authors declare that (1) they have support from Vanderbilt University Medical Center for the submitted work; (2) they have no relationships with companies that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; (3) their spouses, partners, or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and (4) they have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Funding information:

Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction Foundation; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Grant/Award Numbers: K23DK103910, K23DK118118; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant/Award Number: UL1 TR002243/

Footnotes

Competing interest declaration: No authors have commercial relationships that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; their spouses, partners, or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and no authors have non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work

Other declarations: This study was not a randomized, controlled trial, and therefore did not require registration as such. This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board.

Two authors had full access to the data and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; the lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

Data sharing:

no additional data available

References

- 1.Berry SH, Bogart LM, Pham C, et al. Development, validation and testing of an epidemiological case definition of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. J Urol. 2010;183(5):1848–1852. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kairys AE, Schmidt-Wilcke T, Puiu T, Ichesco E, Labus JS, Martucci K, Farmer MA, Ness TJ, Deutsch G, Mayer EA, Mackey S. Increased brain gray matter in the primary somatosensory cortex is associated with increased pain and mood disturbance in patients with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. The Journal of Urology. 2015. Jan;193(1):131–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Windgassen S, McKernan L Cognition, Emotion, and the Bladder: Psychosocial Factors in Bladder Pain Syndrome and Interstitial Cystitis (BPS/IC). Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep 15, 9–14 (2020). 10.1007/s11884-019-00571-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKernan LC, Bonnet KR, Finn MTM, Williams DA, Bruehl S, Reynolds WS, Clauw D, Dmochowski RR, Schlundt DG, Crofford LJ. Qualitative analysis of treatment needs in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: Implications for intervention, Canadian Journal of Pain. 2020, 4(1): 181–198, DOI: 10.1080/24740527.2020.1785854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKernan LC, Nash M, Carr ER. An integrative trauma-based approach toward chronic pain: Specific applications to interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 2016; 26(4): 378–393. doi: 10.1037/a0040050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tripp DA, Nickel JC, Krsmanovic A, et al. Depression and catastrophizing predict suicidal ideation in tertiary care patients with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Can Urol Assoc J. 2016;10(11–12):383–388. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.3892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anger JT, Nissim HA, Le TX, et al. Women’s experience with severe overactive bladder symptoms and treatment: insight revealed from patient focus groups. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(7):1295–1299. doi: 10.1002/nau.21004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds WS, Kaufman MR, Bruehl S, Dmochowski RR, McKernan LC. Compensatory bladder behaviors (“coping”) in women with overactive bladder. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2021; 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daily AM, Kowalik CG, Delpe SD, Kaufman MR, Dmochowski RR, Reynolds WS. Women with overactive bladder exhibit more unhealthy toileting behaviors: a cross- sectional study. Urology. 2019;134:97–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynolds WS, Kowalik C, Cohn J, et al. Women undergoing third line overactive bladder treatment demonstrate elevated thermal temporal summation. J Urol. 2018;200(4):856–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanno PM, Burks DA, Clemens JQ, et al. AUA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. Journal of Urology. 2011;185(6):2162–2170. doi:doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brookes ST, Donovan JL, Wright M, Jackson S, Abrams P. A scored form of the Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms questionnaire: Data from a randomized controlled trial of surgery for women with stress incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coyne KS, Thompson CL, Lai JS, and Sexton CC. An overactive bladder symptom and health-related quality of life short-form: Validation of the OAB-q SF. Neurourol. Urodynam. 2015; 34(3): 255–263. 10.1002/nau.22559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, et al. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain. 2010;150(1):173–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows [Computer software]. Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Compas BE, Jaser SS, Bettis AH, et al. Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(9):939–991. doi: 10.1037/bul0000110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Compas BE, Jaser SS, Dunn MJ, Rodriguez EM. Coping with chronic illness in childhood and adolescence. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2012. Apr 27;8:455–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curtin KB, Norris D. The relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain, anxiety and mindfulness: Adjustments to the Fear-Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain. Scandinavian journal of pain. 2017. Oct 1;17(1):156–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCaffrey R, Frock TL, Garguilo H. Understanding chronic pain and the mind-body connection. Holistic Nursing Practice. 2003. Nov 1;17(6):281–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watkins KE, Eberhart N, Hilton L, Suttorp MJ, Hepner KA, Clemens JQ, Berry SH. Depressive disorders and panic attacks in women with bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis: a population-based sample. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(2):143–49. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li JX. Pain and depression comorbidity: a preclinical perspective. Behavioural brain research. 2015. Jan 1;276:92–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doan L, Manders T, and Wang J. Neuroplasticity underlying the comorbidity of pain and depression. Neural plasticity. 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oken BS, Chamine I. and Wakeland W. A systems approach to stress, stressors, and resilience. Behavioral brain research. 2015; 282:144–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naliboff BD, Locke K, Schrepf AD, Griffith JW, Moldwin R, Krieger JN, Rodriguez LV, Stephens-Shields AJ, Clemens JQ , Lai HH, Sutcliffe S, Taple BJ, Williams D, Pontari MA, Mullins C, Landis JR, for the MAPP Research Network, Reliability and Validity of Pain and Urinary Symptom Severity Assessment in Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain; A MAPP Network Analysis, The Journal of Urology. 2021; doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000002438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Windgassen SS, Sutherland SL, Finn M, Bonnet K, Schlundt DG, Reynolds WS, Dmochowski RR, McKernan LC. Gender Differences in the Experience of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. Frontiers in Pain Research.:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

no additional data available