Abstract

Introduction

Integrated care interventions for type 2 diabetes (T2D) and hypertension (HT) are effective, yet challenges exist with regard to their implementation and scale-up. The ‘SCale-Up diaBetes and hYpertension care’ (SCUBY) Project aims to facilitate the scale-up of integrated care for T2D and HT through the co-creation and implementation of contextualised scale-up roadmaps in Belgium, Cambodia and Slovenia. We hereby describe the plan for the process and scale-up evaluation of the SCUBY Project. The specific goals of the process and scale-up evaluation are to (1) analyse how, and to what extent, the roadmap has been implemented, (2) assess how the differing contexts can influence the implementation process of the scale-up strategies and (3) assess the progress of the scale-up.

Methods and analysis

A comprehensive framework was developed to include process and scale-up evaluation embedded in implementation science theory. Key implementation outcomes include acceptability, feasibility, relevance, adaptation, adoption and cost of roadmap activities. A diverse range of predominantly qualitative tools—including a policy dialogue reporting form, a stakeholder follow-up interview and survey, project diaries and policy mapping—were developed to assess how stakeholders perceive the scale-up implementation process and adaptations to the roadmap. The role of context is considered relevant, and barriers and facilitators to scale-up will be continuously assessed.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained from the Institutional Review Board (ref. 1323/19) at the Institute of Tropical Medicine (Antwerp, Belgium). The SCUBY Project presents a comprehensive framework to guide the process and scale-up evaluation of complex interventions in different health systems. We describe how implementation outcomes, mechanisms of impact and scale-up outcomes can be a basis to monitor adaptations through a co-creation process and to guide other scale-up interventions making use of knowledge translation and co-creation activities.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, PUBLIC HEALTH, PRIMARY CARE, Health policy

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY

The evaluation methods in this paper combine implementation science and scale-up theories in a joint framework.

The identification of sequential indicators for different steps in the scale-up process is innovative and useful to conceptually advance research on scale-up.

The insertion of mechanisms of impact in the evaluation framework allows for empirical testing of theory-based concepts that facilitate scale-up.

The set of data collection tools to track the policy dialogue and scale-up roadmaps are hands-on and can accelerate empirical scale-up research.

A limitation of this study is the delay in data collection due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which in turn could lead to recall bias of stakeholders in interviews on the process of stakeholder collaboration in policy dialogues.

Introduction

To address the rising burden of chronic diseases across the world, global commitments have been made toward an integrated care approach offering multi-disciplinary, non-episodic and patient-centred care.1–5 Integrated care leads to better care coordination and (cost) efficiency, and improves the quality of care and patient outcomes by linking services along the continuum of care.3 6 7 However, the scale-up of integrated care is challenging because chronic diseases pose a wicked problem8–12 requiring multi-stakeholder action and intersectoral coordination at individual healthcare practice, organisational and political/system levels.13 14

Moreover, little is known about how to scale up complex, adaptive and strongly contextualised interventions.14–16 Blueprint approaches to scaling up healthcare interventions commonly described in the literature and global health initiatives are linear process models and do not fit the dynamic, emergent and adaptive scale-up process of complex health interventions.17 Complexity is not just a property of wicked problems, but also of the intervention and the context (or system) into which the intervention takes place.18 A complex intervention can be perceived as a process of changing complex systems,19 involving multi-component, multi-stakeholder and multi-level efforts that are tailored to the contexts in which they are delivered.14 20

The ‘SCale-Up diaBetes and hYpertension care’ (SCUBY) Project aims to develop, co-create and assess roadmaps, which can be adapted for use in different contexts, for scaling up of an integrated care package (ICP) for type 2 diabetes (T2D) and hypertension (HT) in dissimilar types of health systems.21 The ICP comprises of: (a) early detection and diagnosis, (b) treatment in primary care services, (c) health education, (d) self-management support to patients and caregivers, and (e) collaboration between caregivers.21–24 These generic components are implemented via country-specific delivery models, which have been elaborated in the SCUBY protocol paper.21

SCUBY is a multiple case study, in which each country (Belgium, Cambodia and Slovenia) is a case of the ICP scale-up for T2D and HT. These three countries were chosen in view of the lessons that can be drawn from these diverse health system contexts: a developing health system in a lower middle-income country (Cambodia); a centrally steered health system in a high-income country (Slovenia); and a publicly funded, highly privatised healthcare health system in a high-income country (Belgium).21 Hence, the selection of the three cases was based on their health system characteristics, as well as current focus on scale-up strategies. Scale-up is multi-dimensional and requires various efforts to: (1) increase population coverage, (2) integrate or institutionalise ICP into health system services, and (3) expand the intervention package, that is, diversifying the ICP with additional components.21 25–27 Online supplemental appendix 1 provides details on this three-dimensional framework.21 25 The scale-up activities are specifically targeted toward improving primary (low-level) care, in all three countries. Each country focuses on a different scale-up dimension and adopts a suitable scale-up strategy that is in line with contextual needs. In Belgium, where multiple projects have been developed in several areas (current horizontal strategy), the roadmap will focus on how the ICP can be made routine practice in the Belgian health system, and which financial, policy and regulatory reforms can support this transition (integration). In Cambodia, where the vertical (ie, institutional; top-down) strategy is established, the roadmap mainly focuses on adopting a horizontal strategy to increase population coverage of the ICP for T2D and HT care, more specifically, increasing the number of health facilities at the primary care level providing T2D and HT care. In Slovenia, the aim of the roadmap is to strengthen diversification (expanding the ICP) through enhancing the involvement of patients and informal caregivers in healthcare. This will be achieved by down-stepping care from healthcare professionals at the primary care level to patients and informal caregivers. The focus is therefore on patient empowerment and self-management of T2D and HT.

bmjopen-2022-062151supp001.pdf (443.6KB, pdf)

The SCUBY interventions for scale-up involve the development of evidence-based roadmaps and policy dialogues.21 These two methodologies—roadmaps and policy dialogues—are very much intertwined and considered to be key elements for successful stakeholder-supported scale-up.17 The first versions of the roadmaps in each country were developed based on the findings of the formative phase and initial policy dialogues with stakeholders in each country. Subsequently, a feasible and relevant evaluation protocol was developed, in accordance with evaluations of complex interventions, which have a flexible, adaptable design.28 The protocol also describes the framework to guide the evaluation of the scale-up intervention in the SCUBY Project.

The evaluation of the SCUBY intervention constitutes the third phase of the project and includes four (process, scale-up, cost and impact) evaluations with separate research questions.21 This protocol comprises the first two evaluations only: the process and scale-up evaluation of the SCUBY intervention. This will increase the understanding of the process of implementing roadmaps to scale up integrated care and to improve health outcomes, and how this is influenced by different contexts. The specific research questions we aim to address are: (1) how has the country-specific roadmap been implemented and to what extent?; (2) how can the differing contexts influence the implementation process of the scale-up strategies?; and (3) what progress has been made on each of the three axes of scale-up? Table 1 provides key definitions and their application to the SCUBY Project.

Table 1.

Key definitions and their application to the SCUBY Project

| Concept | Definition | Application in the SCUBY Project |

| Roadmap | An action plan delineating the targets, planning and progression of scale-up strategies, identifying actors, actions and timelines based on priorities in place and time.21 | Scale-up intervention In SCUBY, a scale-up roadmap constitutes an overall scale-up strategy and aim; roadmap actions or activities; a problem statement, rationale and objectives/aim(s) for each roadmap action, a timeline to plan roadmap activities within a time frame; and a description of the evidence base and key partners/stakeholders involved in the scale-up (the coordination mechanism per roadmap action). |

| Policy dialogue | An essential component of the policy and decision-making process, where it is intended to contribute to informing, developing or implementing a policy change following a round of evidence-based discussions, workshops and consultations on a particular subject. It is seen as an integrated part of the policymaking process and can be conducted at any level of the health system where a problem is perceived and a decision, policy, plan or action needs to be made.30 | Implementation strategy (to guide the roadmap development to implementation) In SCUBY, policy dialogues are used as an approach in the policymaking process to engage with key stakeholders and to develop the countries’ scale-up roadmaps. They will comprise structured formal events, one-to-one interactions with key stakeholders, workshops, consultations and joining ongoing dialogues within the context.30 |

| Context | Complex adaptive systems that form the dynamic environment(s) in which implementation processes are situated63; a set of characteristics and circumstances that consist of active and unique factors, within which the implementation is embedded. As such, context is not a backdrop for implementation, but interacts, influences, modifies, and facilitates or constrains the intervention and its implementation. Context is usually considered in relation to an intervention, with which it actively interacts. It is an overarching concept, comprising not only a physical location but also roles, interactions and relationships at multiple levels.64 | Mediator The context in SCUBY is assessed at micro, meso and macro levels. Since scale-up is targeting the country level, the process evaluation focuses on the macro-level context, specifically the barriers and facilitators to scale-up. We look at the WHO health system building blocks65 66 and broader political, economic, social, technological, environmental and legal factors. |

| Scale-up | The efforts to increase the impact of health interventions so as to benefit more people and to foster policy and programme development on a sustainable basis.26 | Study aim/goal Scale-up efforts in SCUBY can include various efforts to make progress on any of the three axes. Examples of efforts are: increasing coverage of existing interventions, strengthening or expanding the existing ICP package, and changing financing or monitoring systems. |

ICP, integrated care package; SCUBY, SCale-Up diaBetes and hYpertension care.

The SCUBY intervention: a scale-up roadmap

The SCUBY intervention is an adaptable, evidence-based roadmap for scale-up. This roadmap comprises an action plan with steps and strategies towards a set goal—the scale-up of an ICP to improve access to affordable quality care for T2D and HT. It thus includes both processes and actions by which the ICP is brought to scale. The roadmaps can consist of a mix of scale-up strategies. The term ‘scale-up roadmap’ is derived from the WHO/ExpandNet framework, which also provides classifications according to the degree of the intention of scale-up, formal planning and locus of initiative26 29: (a) top-down strategies whereby the central level decides to implement the innovation and institutionalises it through planning, policy changes or legal action; (b) horizontal strategies to expand geographically or population-based; and (c) diversification strategies referring to adding new elements to an existing intervention. Thus, three major strategic scale-up options are available for roadmaps: a, b, c or a combination of the aforementioned. The three implementing countries in the SCUBY Project follow this categorisation in focus and approach: a vertical, government-steered top-down (type a) strategy in Cambodia; a horizontal strategy (type b) in Belgium and a diversification scale-up strategy (type c) in Slovenia. In addition, countries may deviate from the dominant strategy to include other strategies to maintain progress.

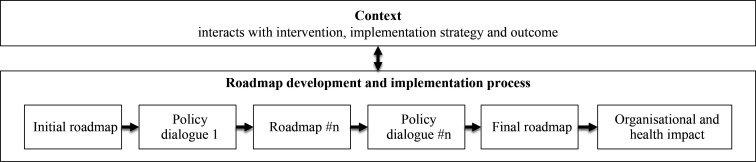

Context in this multi-country study is key, as it interacts with the intervention and the implementation strategy, as well as the (implementation and scale-up) outcomes,28 as shown in figure 1. Contextual factors include barriers and facilitators to scale-up. Each context will influence the development and implementation process of the roadmap differently due to the large cultural, socio-political and economic differences between the implementation countries, and vice versa; in each country under study, the roadmap development and implementation process will have a different impact on the context.

Figure 1.

The interaction between context and the roadmap development and implementation process.

The main implementation strategy: policy dialogues

Within the SCUBY Project, policy dialogues play a crucial role in the implementation of the scale-up roadmaps. Policy dialogues have been introduced by the WHO as a tool to support organisational and/or systemic changes in health and healthcare.30 Concepts linked to policy dialogue are co-creation,31–34 co-production,34–37 deliberative methods and processes,38 social and community participation,39 40 and collaborative governance.41 42

The policy dialogue is the strategy that all implementing countries have in common. This illustrates the necessity of high-level policy engagement and multi-stakeholder collaboration. The policy dialogue can therefore be viewed as SCUBY’s main implementation strategy for the development and implementation of the roadmaps in each country. Because of this ongoing engagement with stakeholders in policy dialogues, the roadmap (intervention) can continue to be adapted and amended over time.

The roadmap development and implementation process in figure 1 represents the ‘co-creative’, emergent process towards scale-up, with multiple feedback loops from the policy dialogues to the roadmap. In addition to scientific and local evidence, the policy dialogues are literally feeding into the roadmap development and implementation; the policy dialogues provide a means to increase stakeholder (and community) support and subsequently contribute to roadmap implementation and thus the scale-up of integrated care for T2D and HT.

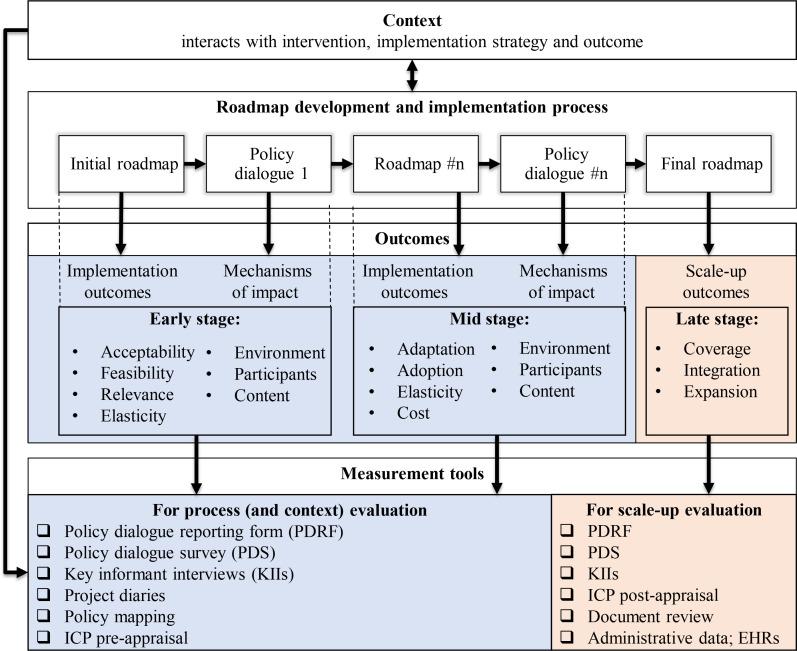

An overarching framework for evaluation

Figure 2 presents a comprehensive framework to guide the evaluation of the roadmap implementation. This framework has been developed to support the process and scale-up evaluation of the SCUBY intervention. It is useful to gain insight into how the key steps of the roadmap development and implementation process can be linked to outcomes and what effective measurement tools are used to capture the roadmap implementation and scale-up process.

Figure 2.

An overall framework for process and scale-up evaluation. Key informant interviews in SCUBY include interviews with stakeholders from resource and implementing organisations26 and with SCUBY research team members in the different implementing countries. EHRs, electronic health records; ICP, integrated care package; SCUBY, SCale-Up diaBetes and hYpertension care.

This framework was adapted from the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance framework for process evaluations,28 emphasising the relevance of context and its interaction with not only the intervention, but also the implementation process, the underlying mechanisms of impact, and early, midterm implementation outcomes and scale-up outcomes. As an overarching framework, it brings together the complex intervention and implementation strategy, presenting it as a process of incremental and cyclical change and adaptation, while linking this process to key indicators, tools and types of evaluation.

The framework distinguishes two types of evaluation: process and scale-up evaluation. Context evaluation can be seen as a subpart of the process evaluation, whereas context has a major influence on the development and implementation process of the complex intervention. The outcomes and measurement tools in this framework are further described in the Methods section of this protocol.

Methods and analysis

Study population and design

The SCUBY Study is a multiple case study, in which each country is a case. The process and scale-up evaluation in this protocol use a mixed-methods design, the process evaluation being qualitative and the scale-up evaluation partly quantitative.43 The study population for the process evaluation are the stakeholders involved in the policy dialogues and the roadmap development and implementation process. The WHO/ExpandNet framework26 derives two main categories: resource and implementing (user) organisations.44 45 Another meaningful classification for stakeholder categorisation comes from Campos and Reich.46 These authors distinguish stakeholder groups that are likely to influence implementation: interest groups, bureaucrats (civil servants from public administration), financial decision-makers, political leaders, beneficiaries and external actors.46 In the SCUBY Project, we distinguish one additional (seventh) group: scientific actors. The study population for the scale-up evaluation is the target population (eg, healthcare providers; patients) living in the areas in which scale-up activities were performed.

Implementation process and scale-up outcomes

This project focuses on the implementation process and scale-up (or progression) outcomes. Their definitions, as well as their theoretical basis, application to the SCUBY Project, and corresponding assessment methods and tools are described in table 2.

Table 2.

Roadmap implementation and scale-up outcomes and measurement

| Outcomes | Definition | Theoretical basis | Application to SCUBY | Assessment methods and tools |

| Roadmap implementation outcomes | ||||

| Acceptability | The perception among implementation stakeholders that a given treatment, service, practice or innovation is agreeable, palatable or satisfactory.47 | Cf. social validity67 | Acceptable: (resource and implementation) stakeholders have mostly consensus or at least majority on way to go. | Surveys; key informants’ interviews |

| Feasibility | The extent to which a new treatment, innovation, strategy or programme can be successfully used or carried out within a given agency or setting.68 | Cf. compatibility69 | Feasibility signifies it is possible to reach the set goals specified within the roadmap. | Surveys; key informants’ interviews |

| Relevance | The perceived fit, appropriateness, or compatibility of the innovation or evidence-based practice (roadmap) for a given practice setting, provider or consumer; and/or perceived fit of the innovation to address a particular issue or problem.47 | Cf. appropriateness, perceived fit47 | Fit and relevance of the proposed framework, strategies, and actions to government policy agenda and stakeholder perception/interest. | Surveys; key informants’ interviews |

| Adoption | The intention, initial decision, or action to try or employ an innovation or evidence-based practice.47 Can be expressed as the absolute number, proportion, and representativeness of settings (contexts) and intervention agents (implementers) that are willing to initiate a programme (policy or intervention). | RE-AIM49; NASSS framework, Cf. non-adoption/abandonment15 50 | Uptake of the proposed roadmap (element). | Policy dialogue reporting form; surveys; key informants’ interviews |

| Adaptation | The extent to which a policy or intervention is changed, the opposite of delivered as intended by its developers and in line with the programme model. It refers to the customisation and ongoing adaptation of the care package or programme model15; in this study, the adaptation of (preliminary and non-final versions of) the roadmap. Also linked to the concept of plasticity—‘the extent to which interventions and their components are malleable and can be moulded to fit their contexts’.48 |

MRC implementation fidelity28; plasticity48 | Policy dialogue reporting form; surveys; key informants’ interviews; document reviews |

|

| Elasticity of the context | Elasticity can be defined as ‘the extent to which contexts can be stretched or compressed in ways that make space for intervention components and allow them to fit’.70 | Elasticity48 | Changes in the context that allow an acceleration or slow-down of roadmap strategies. Example 1: COVID-19 (slow-down because of other priorities, accelerator because of increased digitalisation efforts). Example 2: government change. | Follow-up stakeholder interviews (question on B&F); policy mapping on timeline (keep eye on policy developments and implications) |

| Scale-up outcomes | ||||

| Coverage (horizontal scale) | The extent to which the target group is reached, in absolute and relative count.71 | RE-AIM49 Cf. reach |

Target population reached; number of people actually covered by the intervention. Example: people who have access to GPs/practices with improved ICP/ACIC score in Belgium. Number of HCs (population covered by HCs) implementing newly modified PEN package in Cambodia. Target group members reached with m-health and peer support intervention in Slovenia. |

EHRs; population survey; health report/data; health facility assessment |

| Integration | Integration into health system and services (based on Meessen et al (2017), inspired by the universal coverage framework.25 72 | RE-AIM49 Cf. maintenance Cf. penetration, institutionalisation, sustainability47 |

The extent to which complex systems (structure and processes) allow (maintain and institutionalise) ICP implementation. Example 1: through laws, regulation, financing. The level of institutionalisation of the recommendations in the roadmap. Example 2: in Belgium, health financing reforms and legal reform facilitating nurses in primary care. Example 3: in Cambodia, functioning NCD clinics and community-based peer support are linked to HC-PEN. Example 4: in Slovenia, integration of telemedicine and peer support for chronic patients’ management to primary care. |

Key informants’ interviews; document reviews; Health facility assessment/ICP grid, EHRs |

| Expansion | Expanding the intervention programme (the ICP package to cover other elements). Similar to diversification as a type of scaling up in ExpandNet, also called functional scaling up or grafting, consists of testing and adding a new innovation to one that is in the process of being scaled up, hence, exploring the possibility of pilot testing an added component to the innovation.26 |

Cf. diversification26 | Additional components in ICP; addition of comorbidities to package. Example: in Belgium, addition of nurses to GP practice; in Cambodia, newly modified PEN package; in Slovenia, addition of m-health and peer support to ICP. |

Pre/post-ICP implementation evaluation via ICP grid appraisal of practices; key informants’ interviews |

Tools can be found in the online supplemental appendices.

ACIC, assessment of chronic illness care; B&F, barriers and facilitators; EHRs, electronic health records; GP, general practitioner; HC, health centre; ICP, integrated care package; MRC, Medical Research Council; NASSS, non-adoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability; NCD, non-communicable disease; PEN, package of essential non-communicable disease interventions; RE-AIM, reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance; SCUBY, SCale-Up diaBetes and hYpertension care.

bmjopen-2022-062151supp002.pdf (570.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062151supp003.pdf (85.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062151supp004.pdf (619.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062151supp005.pdf (112.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062151supp006.pdf (67.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062151supp007.pdf (88KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062151supp008.pdf (22.1KB, pdf)

Specific outcomes will be used depending on the stage of the project: early, mid and late.47 Acceptability, feasibility and relevance are key implementation outcomes of roadmaps in the early stage, while adaptation, adoption and cost of roadmap activities will become more relevant from an early to mid-stage as displayed in the middle row in figure 2. In each of these stages (early, mid and late), the role of context will remain relevant, and barriers and facilitators to scale-up will be continuously assessed. Relevant attributes of the context and intervention used in implementation science are elasticity (of the context) and plasticity (of the intervention). Elasticity is linked to institutional fit and change in context brought about by the intervention (and implementation) process, while plasticity is related to the concept of adaption.48 Measurement of the implementation outcomes is guided by multiple evaluation frames, including reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance (RE-AIM)49; the MRC implementation fidelity28; and the non-adoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability (NASSS) framework.15 50

The mechanisms of impact refer to the effects or (causal) pathways of a specific intervention and answer the question ‘how does the delivered intervention produce change?’. The assessment of mechanisms of impact focuses on the policy dialogue which is the major implementation strategy for the roadmap. Potential mechanisms of impact were identified through literature review on the success factors of policy dialogues51–54 and related to: (1) environment, (2) content and (3) participants.55 The mechanisms of impact specific to policy dialogues are presented in table 3.

Table 3.

Mechanisms of impact specific to policy dialogues

| Policy dialogue indicators | Clarification or definition | Relating question |

| ‘Theme—environment’ | ||

| Location | The location the policy dialogue takes place. | Was the room/location suitable? |

| Moderation/ facilitation |

How well the dialogue was moderated; this is key to having meaningful and comprehensive discussions. | How was the moderation? Who was moderating? Why was this person selected? |

| Technical/material conditions | Such as PowerPoint presentation, video, paper/report/information package provided, catering (lunch/snacks/reception). | How were technical/material conditions? |

| ‘Theme—content’ | ||

| High-priority issue | An issue of local, regional, national and international concern. | Was it a high-priority issue (for dialogue participants)? |

| Clear meeting objectives | This goes hand in hand with a clear vision of what outcomes and results would be expected. | Were clear meeting objectives set? |

| Information shared | A pre-circulated information package, including the agenda, evidence summaries, a list of policy directions to be discussed, related background information and an evaluation form. | Which information was shared with participants (in advance, during and after policy dialogue)? |

| Evidence used | Synthesis of high-quality research evidence used to identify needs and educate participants: policy dialogue discussions and participants need to be based on effective stakeholder and context analyses, part of which is evidence-based background information. | Was evidence used/presented in the meeting? |

| Agreement on outcomes and action plan | List of possible and tangible actions or steps. | Was agreement reached on outcomes and action plan? |

| Rules of engagement | The format of the meeting and rules of engagement (giving a clear overview of purpose, participants, design, method and materials). | Was there a formal or informal format? What was the set-up or rules? |

| Preparation of content | The materials created for the policy dialogue and the management of the event of the meeting overall. | Was the policy dialogue well-prepared? |

| Follow-up | The continuation of the policy dialogue, in terms of ongoing communication of next steps and engagement, to keep the momentum alive and renew or regenerate the project’s or programme’s goals.14 | Was there proper follow-up (on next actions, next meeting, evidence/information shared)? |

| ‘Theme—participants’ | ||

| Representation | The stakeholder groups represented or excluded. A mix of participants and stakeholders representing all perspectives and interests: representation of decision-makers, researchers and those affected by the issue under discussion (user/patients groups, formal and informal caregivers). | Which stakeholder groups were represented? Which were excluded? |

| Participation | Social participation requires all stakeholders in the participatory process to be able to adequately and fully exercise their roles. In order to do so, all stakeholders should be, as far as possible, on an equal footing with each other in terms of ability to have influence on the participation-based discussions.73 | Was there equal participation of stakeholders during the discussion? Who participated more? Who participated less? |

| Collaboration | The process of two or more people or organisations working together to complete a task or achieve a goal. | How was the collaboration between stakeholders? |

| Consensus | General agreement on something (by most participants). Five steps in the consensus-building process are: convening, clarifying responsibilities, deliberating, deciding and implementing agreements. | Was consensus reached between stakeholders on a certain issue? |

| Trust | Firm belief in the reliability (or ability) of someone, relational | Was there trust between stakeholders? |

| Mutual respect | Mutual respect is defined as a proper regard for the dignity of a person or position; due regard for each other’s feelings, wishes or rights. | Was there mutual respect? |

| Willingness to implement | Gore et al distinguish three types of commitment,74 namely: expressive commitment, institutional commitment and budgetary commitment. ‘Expressed commitment refers to verbal declarations of support for an issue by high-level, influential political leaders. Institutional commitment comprises the adoption of specific policies and organisational infrastructure in support of an issue. Finally, budgetary commitment consists of earmarked allocations of resources towards a specific issue relative to a particular benchmark. The combination of the three dimensions signals that a state has an explicit intention or policy platform to address this health area.’ | Was there willingness to implement a discussed strategy or action? If yes, which strategy and who showed this will to implement? Type of political commitment? (expressive/financial/institutional (ie, policy)?) How has COVID-19 influenced political will towards NCD care? |

| Leadership | The willingness to initiate, convoke or lead an action for or against the health reform policy.75 | Which stakeholder displayed the most leadership? |

| Urgency | The degree to which stakeholder claims call for immediate attention.76 | Which stakeholder displayed the most urgency? |

| Legitimacy | A generalised perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions.76 | Which stakeholder displayed the most legitimacy? |

| Ownership | Act, right or degree of ownership (possession) and responsibility (taken by the resource/implementing organisation, community and/or beneficiaries) towards any programmes or activities | Which stakeholder had most ownership over the issue? |

NCD, non-communicable disease.

Next to implementation outcomes, scale-up outcomes (‘late stage’ box of the conceptual model displayed in figure 2) will be tracked. We distinguish three scale-up outcomes: (1) coverage, (2) integration and (3) expansion. In the literature, some overlapping concepts are used.47 In implementation literature, the concept of reach is often used interchangeably with coverage. Similarly, maintenance, sustainability and institutionalisation are used to assess integration.47 Expansion as a third dimension—in SCUBY specifically used to indicate an extra element added in the ICP—is similar to the WHO’s use of diversification in their ExpandNet strategy for scale-up.26 The scale-up outcomes will be assessed qualitatively and include some quantitative elements. Expansion will be measured via a questionnaire with items on the five ICP components (the ICP grid). The questionnaire contains items per ICP component which are scored on a 5-point Likert scale. This instrument—the ICP grid—was developed in collaboration between the different SCUBY country teams. It was adapted from the WHO’s Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions56 framework situation assessment and the assessment of chronic illness care,57 which has been validated in high-income countries. This way, ICP implementation in a particular area/organisation is assessed before the start of scale-up and at the end of the project. Furthermore, we can assess whether ICP coverage along its five components has expanded over 4 years (2019 vs 2022). To complement the ICP grid, interviews with implementors will be conducted, especially if a specific programme-intervention (eg, training or new health education programme for patients) or new policy gets implemented. Coverage (ie, number of people covered by the ICP) will be measured quantitatively, using a population survey or electronic health records. If time and resources allow, multiple time series data can be used to track ICP coverage. The axis integration will be assessed through health facility stakeholder interviews, and review of policy documents and grey literature. Hence, progress on integration will be reported descriptively.

Data sources and collection tools

Key data collection tools developed for the process evaluation include:

The policy dialogue reporting form.

The policy dialogue survey.

The researcher interview guide.

The follow-up stakeholder interview guide.

Project diaries.

Policy mapping: document review to generate a policy timeline.

ICP grid for implementation assessment.

Most of these are used to collect data on the policy dialogue and roadmap process, as well as on context. Tools were defined based on both the indicators (as displayed in tables 2 and 3) to be included and the activities entailed in the roadmap. Some tools, in particular, the policy dialogue reporting form and the survey are based on instruments developed by CHRODIS+.52 All methods and tools will be adapted to the specific needs and context of the countries’ scale-up strategies.

The policy dialogue reporting form (tool 1 in online supplemental appendix 2) serves as a self-report to be filled in by the research team to evaluate the policy dialogue, the roadmap progress and contextual barriers.52 Aside from a section with general questions concerning the policy dialogue, a section is foreseen for the rapporteur to write the minutes of the meeting, preferably during (and/or immediately after) the policy dialogue.

The policy dialogue survey (tool 2 in online supplemental appendix 3) is to be completed by participants at the end of each policy dialogue (that is organised by SCUBY).52 A survey link is generated through the REDCap database58 59 and can be made accessible to participants online using mobile phones. A paper version can be an option if country teams prefer this and if this better fits the circumstances (depending on the location). Items are related to the relevance and feasibility of discussed (roadmap) actions and strategies (implementation outcomes) and to barriers and facilitators for the implementation and scale-up of discussed strategies (context).

Qualitative, in-depth follow-up researcher interviews (tool 3 in online supplemental appendix 4) with the country teams will be planned regarding the reporting forms to elaborate on items related to the roadmap and policy dialogue (in line with the implementation outcomes and mechanisms). Additional qualitative explanatory follow-up stakeholder interviews (tool 4 in online supplemental appendix 5) will be undertaken to further explore perceptions of policy dialogue and roadmap processes and contextual factors in depth.

The aim of the project diary (tool 5 in online supplemental appendix 6) is to display key research activities undertaken for roadmap development and implementation. The policy mapping (tool 6 in online supplemental appendix 7) will help track key policy developments and evolutions in the field of integrated care. Furthermore, as a tool, it can be used to guide or contextualise the purpose of the (next) policy dialogue meeting. Both the project diary (tool 5) and the policy document mapping (tool 6)—which will generate a policy timeline on integrated care—assess how the context influences SCUBY’s activities and vice versa. The policy mapping will inform the stakeholder interview (tool 3) and vice versa, especially in relation to the existing policy and political barriers and facilitators that stakeholder participants might wish to further comment on. Also, other policies and political events or activities (eg, elections) might be tracked if they impact integrated chronic care policy, such as COVID-19 restrictions or new regulations for the care and control of the chronically ill in COVID-19 times (eg, different modes of delivery, changed duration, materials or location, increased use of information technology tools and online consultations, etc).

The ICP grid at the healthcare practices (tool 7), which was used as part of context analysis in year 1,21 will be used again to evaluate expansion of the ICP grid, so that it can serve as a before–after evaluation in those areas where it was used before.21

Data management and analysis

Qualitative data will be stored as transcripts in country-specific databases as pseudonymised data. The transcripts will be stored in formats that are exportable to NVivo software (NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International) for analysis. Primary and secondary quantitative data (related to the scale-up dimensions of coverage and expansion) collected from the implementation sites will be collated into the main study REDCap database via validated electronic survey forms. Anonymised data will be transferred over the internet using secured data communication protocols for analyses.

For the qualitative implementation outcomes, thematic analyses will be conducted based on the reporting forms, interviews and surveys. As such, evidence from different tools on policy dialogue (success factors), roadmap (progress on adoption and implementation) and context (barriers and facilitators to scale-up) will be triangulated, considering the various perspectives of implementors, other stakeholders and the SCUBY researchers. Themes will be deduced both from existing literature and theory surrounding policy dialogues and roadmaps and grounded in the data. Many of the developed tools have clear topics, relating either to underlying policy dialogue mechanisms or to roadmap implementation outcomes. A theorising approach will be used to explore how context, actors, roadmap activities and outcomes (cf. framework) are connected.60

The dynamic policy and political processes (events, actions and activities) unfolding over time in context will be explored using processual analysis.61 62 Policy document review, desk research and input from interview participants on an initial policy mapping will be triangulated and further refined to enable tracking the emergence of integrated care policies from a historical perspective, resulting in a more detailed chronic care policy timeline. A minor part of the analysis will consist of a retrospective stakeholder analysis on the sole attribute of the position of stakeholders on the roadmap development and implementation.

For the analysis of the scale-up dimensions, findings from different measurement tools will be triangulated. Progress on integration will be assessed qualitatively—while cross-checking information from (policy) document review and interviews—using thick descriptions, on the ways in which roadmap actions (including interventions, programmes and reforms) have become institutionalised. Quantitative data analysis on the scale-up dimensions (coverage and expansion) will entail a pre/post-design. For expansion, interviews with implementors and the ICP grid will be analysed again at the end of the project to give an estimate on how ICP implementation has improved or deteriorated across its five components, in comparison with the previous ICP implementation assessment of 2019.

A flow chart of how data collection tools feed into the different types of analyses can be found in online supplemental appendix 8. By employing multiple methods, data sources and a larger analysis team (independent researchers conducting the analysis and feeding back to country research teams for discussion on the findings), we cross-check information and conclusions drawn from the data via triangulation and data saturation and thereby ensuring the credibility of the data.

Regarding the planned start and end dates for the study, data collection commenced in year 2 of the SCUBY Project (early 2020), shortly following the development of the tools and this protocol paper. Data collection will be finalised end of December 2022. Data analysis will run from October 2022 until March 2023.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. The individual countries are likely to have community and patient involvement (eg, in the policy dialogues), depending on the specifics of each scale-up roadmap, and hence, their involvement is beyond the scope of this current protocol.

Ethics and dissemination

The Institutional Review Board (ref. 1323/19) at the Institute of Tropical Medicine (Nationalestraat 155, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium) approved this study on 1 July 2021. Findings will be (1) reported to national, regional and local governments to inform policy; (2) reported to funding bodies (European Commission) and networks, such as the Global Alliance of Chronic Diseases, in line with their 2019 Scale Up Call; (3) presented at local, national and international conferences; and (4) disseminated by peer-reviewed publications.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @MonikaMartens5, @SreanChhim

Contributors: The first (MM) and final (DB) authors were responsible for the conceptualisation and writing of the manuscript. EW, JvO and KK-G reviewed different versions throughout the drafting process. MM, DB, EW, JvO, KK-G, GMVK, ZKK, SChhim, SChham, VB, KD, NS, CZ, APS, WVD, IP and RR were involved in the development of the data collection tools. All authors contributed to the final draft of the manuscript, have read the manuscript and approved it for submission.

Funding: This protocol is part of the ‘SCale-Up diaBetes and hYpertension care’ (SCUBY) Project, supported by funding from the Horizon 2020 programme of the European Union (grant number 825432).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Facts sheet: noncommunicable diseases, 2018. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases [Accessed 4 May 2020].

- 2.World Health Organization . Global status report on noncommunicable diseases, 2014. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/148114/9789241564854_eng.pdf [Accessed 25 Nov 2021]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Timpel P, Lang C, Wens J, et al. The Manage Care Model - Developing an Evidence-Based and Expert-Driven Chronic Care Management Model for Patients with Diabetes. Int J Integr Care 2020;20:2–13. 10.5334/ijic.4646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armitage GD, Suter E, Oelke ND, et al. Health systems integration: state of the evidence. Int J Integr Care 2009;9:e82. 10.5334/ijic.316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrer L, Goodwin N. What are the principles that underpin integrated care? Int J Integr Care 2014;14:e037. 10.5334/ijic.1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Expert Group on Health Systems Performance Assessment . BLOCKS - Tools and Methodologies to Assess Integrated Care in Europe. European Union, 2017. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/default/files/systems_performance_assessment/docs/2017_blocks_en_0.pdf [Accessed 4 May 2020].

- 7.Maruthappu M, Hasan A, Zeltner T. Enablers and barriers in implementing integrated care. Health Syst Reform 2015;1:250–6. 10.1080/23288604.2015.1077301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakab M, Palm W, Figueras J. Health systems respond to NCDS: the opportunities and challenges of leapfrogging. Eurohealth 2018;24:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kickbusch I, Buckett K. Implementing health in all policies: Adelaide 2010. Adelaide: government of South Australia, 2010. Available: https://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/implementinghiapadel-sahealth-100622.pdf [Accessed 25 Nov 2021].

- 10.Lin V, Jones C, Wang S. The world bank health in all policies as a strategic policy response to NCDS. World Bank, 2014Available:. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/20064 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neel D. A “Wicked Problem”: Combating Obesity in the Developing World. Harvard College Global Health Review, 2011. https://www.hcs.harvard.edu/hghr/online/obesity-developing/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.The PloS medicine editors. addressing the Wicked problem of obesity through planning and policies. PLOS Medicine 2013;10:e1001475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breda J, Wickramasinghe K, Peters DH, et al. One size does not fit all: implementation of interventions for non-communicable diseases. BMJ 2019;367:l6434. 10.1136/bmj.l6434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willis CD, Riley BL, Stockton L, et al. Scaling up complex interventions: insights from a realist synthesis. Health Res Policy Syst 2016;14:88. 10.1186/s12961-016-0158-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C, et al. Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating Nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e367. 10.2196/jmir.8775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grooten L, Alexandru C-A, Alhambra-Borrás T, et al. A scaling-up strategy supporting the expansion of integrated care: a study protocol. J Integr Care 2019;27:215–31. 10.1108/JICA-04-2018-0029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paina L, Peters DH. Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy Plan 2012;27:365–73. 10.1093/heapol/czr054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawe P. Lessons from complex interventions to improve health. Annu Rev Public Health 2015;36:307–23. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore GF, Evans RE. What theory, for whom and in which context? reflections on the application of theory in the development and evaluation of complex population health interventions. SSM Popul Health 2017;3:132–5. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trompette J, Kivits J, Minary L, et al. Dimensions of the complexity of health interventions: what are we talking about? A review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17. 10.3390/ijerph17093069. [Epub ahead of print: 28 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Olmen J, Menon S, Poplas Susič A, et al. Scale-Up integrated care for diabetes and hypertension in Cambodia, Slovenia and Belgium (SCUBY): a study design for a quasi-experimental multiple case study. Glob Health Action 2020;13:1824382. 10.1080/16549716.2020.1824382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pruitt S, Epping-Jordan J. Innovative care for chronic conditions: building blocks for action: global report. World Health Organization, 2002. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42500/WHO_NMC_CCH_02.01.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demaio AR, Kragelund Nielsen K, Pinkowski Tersbøl B, et al. Primary health care: a strategic framework for the prevention and control of chronic non-communicable disease. Glob Health Action 2014;7:24504. 10.3402/gha.v7.24504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization . Package of essential noncommunicable (Pen) disease interventions for primary health care in low-resource settings, 2010. Available: http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases [Accessed 20 May 2021].

- 25.Meessen B, Shroff ZC, Ir P, et al. From scheme to system (Part 1): notes on conceptual and methodological innovations in the multicountry research program on scaling up Results-Based financing in health systems. Health Syst Reform 2017;3:129–36. 10.1080/23288604.2017.1303561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization/Expandnet . Nine steps for developing a scaling-up strategy, 2010. Available: https://www.who.int/immunization/hpv/deliver/nine_steps_for_developing_a_scalingup_strategy_who_2010.pdf [Accessed 25 Nov 2021].

- 27.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 2004;82:581–629. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258. 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghiron L, Ramirez-Ferrero E, Badiani R, et al. Promoting scale-up across a global project platform: lessons from the evidence to action project. Glob Implement Res Appl 2021;1:69–76. 10.1007/s43477-021-00013-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajan D, Adam T, Husseiny D. Briefing note: policy dialogue: what it is and how it can contribute to evidence-informed decision-making. World Health Organization, 2015. https://www.uhcpartnership.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/2015-Briefing-Note.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bammer G. Key issues in co-creation with stakeholders when research problems are complex. Evid Policy 2019;15:423–35. 10.1332/174426419X15532579188099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frow P, McColl-Kennedy JR, Payne A. Co-Creation practices: their role in shaping a health care ecosystem. Industrial Marketing Management 2016;56:24–39. 10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenhalgh T, Jackson C, Shaw S, et al. Achieving research impact through co-creation in community-based health services: literature review and case study. Milbank Q 2016;94:392–429. 10.1111/1468-0009.12197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voorberg WH, Bekkers VJJM, Tummers LG. A systematic review of co-creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Management Review 2015;17:1333–57. 10.1080/14719037.2014.930505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beckett K, Farr M, Kothari A, et al. Embracing complexity and uncertainty to create impact: exploring the processes and transformative potential of co-produced research through development of a social impact model. Health Res Policy Syst 2018;16:118. 10.1186/s12961-018-0375-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beran D, Pesantes MA, Berghusen MC, et al. Rethinking research processes to strengthen co-production in low and middle income countries. BMJ 2021;372:m4785. 10.1136/bmj.m4785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Social Care Institute for Excellence . Co-production in social care: What it is and how to do it - What is co-production - Principles of co-production. SCIE Guide 51 2010;2013:1–20 http://www.scie.org.uk/publications/guides/guide51/what-is-coproduction/principles-of-coproduction.asp [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abelson J, Forest P-G, Eyles J, et al. Deliberations about deliberative methods: issues in the design and evaluation of public participation processes. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:239–51. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00343-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization . Handbook on social participation for UHC - UHC2030, 2020. Available: https://www.uhc2030.org/what-we-do/voices/accountability/handbook-on-social-participation-for-uhc/ [Accessed 17 May 2021].

- 40.Irvin RA, Stansbury J. Citizen participation in decision making: is it worth the effort? Public Adm Rev 2004;64:55–65. 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00346.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torfing J, Peters B, Pierre J. Interactive Governance: Advancing the Paradigm. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emerson K. Collaborative governance of public health in low- and middle-income countries: lessons from research in public administration. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000381. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grant A, Treweek S, Dreischulte T, et al. Process evaluations for cluster-randomised trials of complex interventions: a proposed framework for design and reporting. Trials 2013;14:15. 10.1186/1745-6215-14-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simmons R, Shiffman J. Scaling-up health service innovations - a framework for action. In: Simmons R, Fajans P, Ghiron L, eds. Scaling up health service delivery: from pilot innovations to policies and programmes. Geneva: WHO, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simmons R, Fajans P, Ghiron L. Scaling up health service delivery: from pilot innovations to policies and programmes. World health Organization/ExpandNet, 2007. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43794/9789241563512_eng.pdf [Accessed 25 Nov 2021].

- 46.Campos PA, Reich MR. Political analysis for health policy implementation. Health Syst Reform 2019;5:224–35. 10.1080/23288604.2019.1625251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.May CR, Johnson M, Finch T. Implementation, context and complexity. Implement Sci 2016;11:141. 10.1186/s13012-016-0506-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1322–7. 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abimbola S, Patel B, Peiris D, et al. The NASSS framework for ex post theorisation of technology-supported change in healthcare: worked example of the Torpedo programme. BMC Med 2019;17:233. 10.1186/s12916-019-1463-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Damani Z, MacKean G, Bohm E, et al. The use of a policy dialogue to facilitate evidence-informed policy development for improved access to care: the case of the Winnipeg central intake service (WciS). Health Res Policy Syst 2016;14:78. 10.1186/s12961-016-0149-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.EuroHealthNet . Policy dialogues: Chrodis plus guide. National level, 2018. Available: www.chrodis.eu [Accessed 25 Nov 2021].

- 53.Lavis JN, Boyko JA, Oxman AD, et al. Support tools for evidence-informed health Policymaking (STP) 14: organising and using policy dialogues to support evidence-informed policymaking. Health Res Policy Syst 2009;7 Suppl 1:S14. 10.1186/1478-4505-7-S1-S14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lavis JN, Boyko JA, Gauvin F-P. Evaluating deliberative dialogues focussed on healthy public policy. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1287. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mulvale G, McRae SA, Milicic S. Teasing apart "the tangled web" of influence of policy dialogues: lessons from a case study of dialogues about healthcare reform options for Canada. Implement Sci 2017;12:96. 10.1186/s13012-017-0627-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.World Health Organization . Innovative care for chronic conditions: building blocks for action. global report, 2002. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42500/WHO_NMC_CCH_02.01.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed 13 July 2022].

- 57.Bonomi AE, Wagner EH, Glasgow RE, et al. Assessment of chronic illness care (ACIC): a practical tool to measure quality improvement. Health Serv Res 2002;37:791–820. 10.1111/1475-6773.00049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap Consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kislov R, Pope C, Martin GP, et al. Harnessing the power of theorising in implementation science. Implement Sci 2019;14:103. 10.1186/s13012-019-0957-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pettigrew AM. What is a processual analysis? Scandinavian Journal of Management 1997;13:337–48. 10.1016/S0956-5221(97)00020-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mills A, Durepos G, Wiebe E. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 63.May C. Towards a general theory of implementation. Implementation Science 2013;8:8–18. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pfadenhauer LM, Mozygemba K, Gerhardus A, et al. Context and implementation: a concept analysis towards conceptual maturity. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2015;109:103–14. 10.1016/j.zefq.2015.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.World Health Organization . Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action, 2007. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43918/9789241596077_eng.pdf [Accessed 25 Nov 2021].

- 66.World Health Organization . Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a Handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies, 2010. Available: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/WHO_MBHSS_2010_full_web.pdf [Accessed 25 Nov 2021].

- 67.World Health Organization . A guide to implementation research in the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases, 2016. Available: http://apps.who.int/bookorders [Accessed 25 Nov 2021].

- 68.Karsh B-T. Beyond usability: designing effective technology implementation systems to promote patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:388–94. 10.1136/qshc.2004.010322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. 4th ed. New York: Free Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci 2013;8:117. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Steenaart E, Crutzen R, de Vries NK. Implementation of an interactive organ donation education program for Dutch lower-educated students: a process evaluation. BMC Public Health 2020;20:739. 10.1186/s12889-020-08900-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.World Health Organization . The world health report 2008. Primary Health Care. Now More Than Ever 2008. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43949/9789241563734_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 73.World Health Organization . Voice, agency, empowerment: Handbook on social participation for universal health coverage, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027794 [Accessed 25 Nov 2021].

- 74.Gore RJ, Fox AM, Goldberg AB, et al. Bringing the state back in: understanding and validating measures of governments' political commitment to HIV. Glob Public Health 2014;9:98–120. 10.1080/17441692.2014.881523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schmeer K. Guidelines for conducting a Stakeholder analysis, 1999. Available: https://www.who.int/management/partnerships/overall/GuidelinesConductingStakeholderAnalysis.pdf [Accessed 20 Sep 2020].

- 76.Mitchell RK, Agle BR, Wood DJ. Toward a theory of Stakeholder identification and salience: defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad Manage Rev 1997;22:853. 10.2307/259247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-062151supp001.pdf (443.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062151supp002.pdf (570.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062151supp003.pdf (85.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062151supp004.pdf (619.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062151supp005.pdf (112.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062151supp006.pdf (67.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062151supp007.pdf (88KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062151supp008.pdf (22.1KB, pdf)