Abstract

Introduction

Individuals living with and beyond cancer from rural and remote areas lack accessibility to supportive cancer care resources compared with those in urban areas. Exercise is an evidence-based intervention that is a safe and effective supportive cancer care resource, improving physical fitness and function, well-being and quality of life. Thus, it is imperative that exercise oncology programs are accessible for all individuals living with cancer, regardless of geographical location. To improve accessibility to exercise oncology programs, we have designed the EXercise for Cancer to Enhance Living Well (EXCEL) study.

Methods and analysis

EXCEL is a hybrid effectiveness-implementation study. Exercise-based oncology knowledge from clinical exercise physiologists supports healthcare professionals and community-based qualified exercise professionals, facilitating exercise oncology education, referrals and programming. Recruitment began in September 2020 and will continue for 5 years with the goal to enroll ~1500 individuals from rural and remote areas. All tumour groups are eligible, and participants must be 18 years or older. Participants take part in a 12-week multimodal progressive exercise intervention currently being delivered online. The reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance (RE-AIM) framework is used to determine the impact of EXCEL at participant and institutional levels. Physical activity, functional fitness and patient-reported outcomes are assessed at baseline and 12-week time points of the EXCEL exercise intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board of Alberta. Our team will disseminate EXCEL information through quarterly newsletters to stakeholders, including participants, qualified exercise professionals, healthcare professionals and community networks. Ongoing outreach includes community presentations (eg, support groups, fitness companies) that provide study updates and exercise resources. Our team will publish manuscripts and present at conferences on EXCEL’s ongoing implementation efforts across the 5-year study.

Trial registration number

Keywords: ONCOLOGY, Adult oncology, REHABILITATION MEDICINE

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

A strength of EXercise for Cancer to Enhance Living Well (EXCEL) is that it incorporates methodology (ie, outreach, program delivery, continued support) tailored for developing partnerships with healthcare professionals and qualified exercise professionals in rural and remote communities on a national scale for sustainable exercise oncology implementation.

An additional strength of the EXCEL study is the integration of health behaviour change techniques within the online 12-week exercise intervention, addressing a critical gap in the current exercise oncology literature.

The primary limitation of the EXCEL study is the inability to compare individuals who exercised to a usual care group as this hybrid effectiveness-implementation study design includes a single exercise group.

Additional limitations include ensuring consistent delivery of the exercise intervention across different qualified exercise professionals as well as addressing the current culture of ‘standard cancer care’, which does not include exercise and thus may impact our ability to build clinic-to-community links.

Introduction

While cancer incidence and survival rates are relatively similar across Canada, health disparities in oncological and survivorship care persist. Many Canadians living with and beyond cancer remain underserved in rural and remote communities with respect to supportive cancer care services and resources, and consequently report greater psychological distress and poorer health compared with urban counterparts.1 2 Lack of access to supportive cancer care, such as community-based exercise oncology programmes, is a significant concern, as exercise is an evidence-based intervention that can improve overall health, well-being, and quality of life (QOL) for those living with and beyond cancer.3 Barriers to supportive cancer care in rural and remote communities include having populations with lower socioeconomic status as well as geographical isolation resulting in fewer healthcare providers, increased travel distances/times to the nearest supportive resources and facilities, and lack of infrastructure (eg, unable to access telehealth services).4–6 Furthermore, as the COVID-19 pandemic places further strain on healthcare systems, those from underserved communities continue to be disproportionately impacted as supportive cancer care is delayed and inaccessible telehealth services persist.7 As such, these disparities have increased the burden of cancer on overall health and QOL, and there is a clear need to make exercise as a supportive cancer care resource more easily accessible for those in rural and remote areas.

Exercise improves cancer survivorship outcomes and QOL,8 and research has resulted in the development of cancer-specific exercise guidelines.9–12 However, despite this evidence, guidelines and advocacy, less than a quarter of people with cancer are considered to be physically active,13 and these participation rates may be even less for rural and remote populations due to a lack of exercise oncology resources within these communities.14 To ensure equitable access, there must be development, dissemination and implementation of exercise oncology evidence-based resources to deliver sustainable exercise programmes safely and effectively for all individuals with cancer.

Members of our team are conducting a community-based, hybrid effectiveness-implementation exercise oncology study, the Alberta Cancer Exercise (ACE) study.15 A limitation of the ACE study is that it focuses on delivering services to urban populations and only in one region (Alberta), and as such, the implementation processes may not be generalisable to rural and remote communities. Moreover, an important opportunity exists to examine wide-spread implementation and assess the development and dissemination of exercise intervention effectiveness on a national scale. This type of evaluation is critical for building exercise as a supportive cancer care resource for more individuals living with and beyond cancer in all regions of a geographically and sociodemographically diverse nation, providing valuable information on feasibility and impact on participant and system-level outcomes in real-world settings. To specifically address the commonly reported barriers to exercise for rural and remote individuals with cancer, we aim to improve accessibility of required expertise, make use of digital technology and develop a network of clinic-to-community partnerships for sustainable implementation.16 17 Accordingly, we have designed a 5-year hybrid effectiveness-implementation study to address these disparities in access to exercise—the EXercise for Cancer to Enhance Living Well (EXCEL) study.

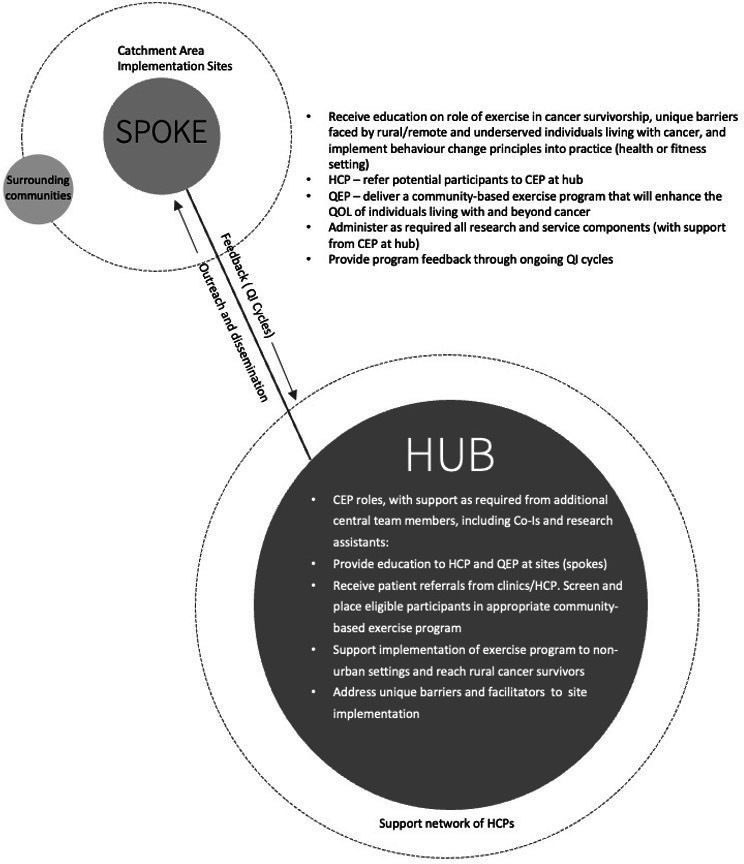

Previous work indicates that successful implementation for rural and remote populations requires personnel training, program support from healthcare professionals (HCPs) and sustainable community partnerships.14 17 Therefore, we will implement our exercise oncology ‘hub and spoke’ model (figure 1) that connects exercise oncology expertise and clinical support in primarily hub settings (ie, urban areas) to intervention implementation within spokes (ie, rural and remote communities). Specifically, EXCEL will provide HCPs with exercise oncology resources, including education and support for participant intake (referral and screening) in the clinical setting, and build clinic-to-community referral pathways that bridge HCPs and rural and remote communities with qualified exercise professionals (QEPs). This will reduce the reliance on participant self-referrals. In addition, EXCEL will provide exercise oncology-specific training to QEPs in these ‘spokes’ to deliver an evidence-based exercise oncology programme online that is safe, effective and tailored to meet participants’ needs. Our objectives are to disseminate, implement and assess the effectiveness of EXCEL to increase the reach, delivery and impact of an exercise intervention to rural and remote individuals living with cancer. In doing so, the EXCEL study will provide a better understanding of the various factors associated with making evidence-based exercise oncology interventions accessible and sustainable.

Figure 1.

Exercise oncology survivorship hub and spoke model. CEP, clinical exercise physiologist; HCPs, healthcare professionals; QEP, qualified exercise professional; QI, quality improvement; QOL, quality of life.

Methods and analysis

Design and setting

A hybrid effectiveness-implementation study design18 that uses mixed methods is being used to determine the effectiveness and implementation of the EXCEL exercise intervention (NCT04478851). Due to the pandemic, the original clinical trial registration varies in methodology with the current version of EXCEL. Specifically, EXCEL is primarily being implemented in an online format, rather than delivering in-person community-based fitness classes and assessments. As such, fitness assessment methodology differs slightly from the clinical trial registration to feasibly and safely use the online format. It is important to note that EXCEL was intended to include online delivery via ZOOM to increase reach to the targeted underserved populations. As the pandemic allows, the study will begin to implement in-person exercise classes and fitness assessments, with slight variations to the current protocol (see online supplemental appendix 1 for a list of program components for online and in-person delivery).

bmjopen-2022-063953supp001.pdf (46.5KB, pdf)

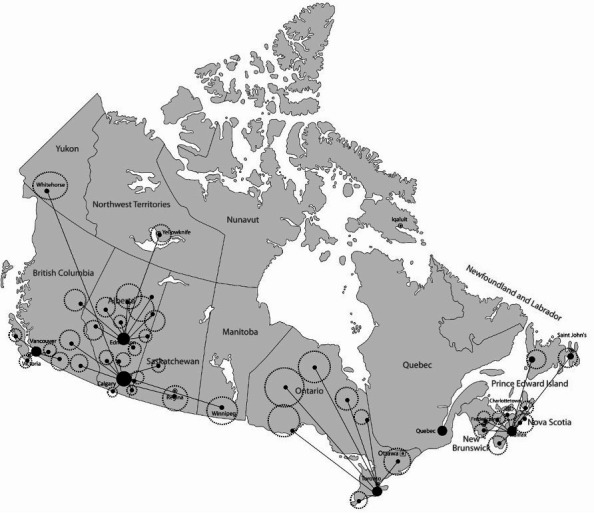

The effectiveness-implementation research design has been used previously by members of the research team to implement ACE.15 EXCEL is implemented by establishing geographical hubs in urban settings that link to both academic and clinical expertise. Hub expertise includes clinical exercise physiologists (CEPs), responsible for exercise screening of participants, developing and maintaining partnerships with HCPs and QEPs for exercise referral and delivery, and when required, delivering the supervised exercise intervention for high-risk participants. Refer to table 1 for hub outreach roles. Hubs established at the project outset are in Alberta, Nova Scotia and Ontario, with plans to add British Columbia and Quebec in years 2–4. See figure 2 for the current geographical map of EXCEL hub and the community rural and remote regions (ie, spokes) they currently serve. EXCEL employs the Canadian Institutes of Health Research knowledge to action framework19 to guide the process of translating research evidence into practice, as well as a participant-oriented research approach to tailor implementation strategies to better address participants’ needs. Specifically, a monthly Participant Advisory Board (PAB) meeting with former exercise oncology program (including EXCEL) participants discusses recurring implementation issues that need to be addressed, and 6-month quality improvement (QI) cycles (electronic surveys sent to participations, HCPs and QEPs), provide feedback to the study team regarding outreach, intervention delivery and provision of supportive resources (eg, educational webinars), all of which are used to inform the continued implementation and evaluation of EXCEL.

Table 1.

Outreach from central hubs to healthcare and qualified exercise professionals

| Outreach from central hubs | |

| HCPs |

|

| QEPs |

|

EXCEL, EXercise for Cancer to Enhance Living Well; HCPs, Healthcare Professionals; QEPs, qualified exercise professionals.

Figure 2.

EXCEL hub and spoke map. EXCEL, EXercise for Cancer to Enhance Living Well.

Participants and screening

EXCEL participant enrolment occurs from September 2020 to September 2025. Participants are included if they are: 18 years or older living with and beyond cancer, able to participate in mild levels of physical activity, can consent in English (French translation work is underway), and live in underserved rural/remote communities that do not have access to exercise oncology programs (The term ‘underserved’ expanded during COVID-19 restrictions to also include those from additional areas (eg, smaller urban areas) who did not have any access to exercise oncology resources.).

Participants can self-refer or be referred by an HCP to a hub CEP who screens for study eligibility and provides participants with the electronic study consent form (see online supplemental file 1). Consent forms and study data are collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).20 21 REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data capture; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources. After providing informed consent, intake information is gathered about cancer-related medical history, treatment-related side effects, other chronic conditions or injuries, and physical activity readiness via the PARQ+.22 The intake form and PARQ+ are reviewed by the hub CEP to screen for exercise participation.

bmjopen-2022-063953supp002.pdf (136.6KB, pdf)

Exercise intervention

Prior to delivering the EXCEL exercise intervention, QEPs are provided with exercise oncology and health behaviour change training to facilitate exercise intervention delivery of our ‘Exercise and Educate’ model (see further description below). Training includes online modules related to exercise screening, cancer exercise prescription, and psychosocial, and health behaviour change principles from Thrive Health Services (www.thrivehealthservices.com). An EXCEL-specific training day also covers study-specific needs, additional health behaviour change educational topics delivered as part of the intervention, and logistics of the overall exercise program delivery. Prior to leading an exercise class, QEPs are required to moderate exercise classes to become familiar with online exercise delivery. Moderating ranges from 6 to 24 classes and is dependent on the QEPs background and previous experience working in exercise oncology.

The exercise intervention is guided by the template for intervention desciption and replication (TIDieR) checklist23 and is based on previous successful online implementation of ACE15 and current exercise oncology guidelines.11 EXCEL’s online exercise intervention is delivered via ZOOM with password-protected exercise classes, and the exercise class instructor (QEP or CEP, depending on the participant needs; eg, high-risk individuals such as those on-treatment are always under the exercise supervision of a CEP) is assisted by a trained moderator (QEP). Each class consists of 8–15 participants to ensure safety and ability to tailor to meet participant needs within the online delivery format. The intervention is a standardised 12-week evidence-based exercise intervention with two sessions per week, with at least 1 day of rest between classes. Classes are 60 min in duration and include the following: (1) 5 min warm-up; (2) 45–50 min of circuit style training consisting of strength/resistance, balance, and aerobic activities and (3) 5–10 min cool-down consisting of full-body stretching. Instructors demonstrate each exercise, tailoring to address participants’ needs including exercise progressions (eg, push-ups from wall to floor) or regressions (eg, push-ups from floor to wall). Fidelity checks are carried out by the central (Calgary) hub CEPs to ensure consistency and safety in the delivery of the exercise intervention across partner sites. Using a standardised fidelity reporting form for each site, a random 10% of exercise classes for each 12-week session are observed and reviewed, and any feedback to improve delivery is provided to the exercise leaders (CEP/QEP).

To support both adoption and maintenance of physical activity, the EXCEL study implements the ‘Exercise and Educate’ model within the exercise intervention. The trained QEPs are tasked with implementing ‘Exercise and Educate’ within each exercise class, via a positive motivational approach to instructing (ie, teach from the positive, focusing on what someone can do vs cannot do to build a sense of confidence and control within participants) and engaging in discussion within classes on the key behaviour change techniques. In addition, throughout the 12-week exercise intervention participants are provided weekly educational and worksheet handouts and attend webinars to facilitate further learning and connecting with experts on behaviour change techniques and key exercise principles as they relate to their physical activity engagement. Specifically, the education topics include (1) Principles of Exercise and Cancer, (2) Self-Monitoring for Physical Activity (3) Setting Physical Activity Goals, (4) Behaviour Change and Relapse Prevention, (5) Fatigue and Stress Management, and (6) Social Support and Long-Term Maintenance. These education topics have been built based on participant feedback (ie, what they want to learn more about), and are designed to engage participants in discussion, foster self-efficacy and equip them with the behaviour change techniques to apply in their daily life. Specific skills learnt include self-monitoring, barrier management, planning, goal setting, how to build social support, and building confidence to see oneself as ‘an exerciser’.

Assessing implementation: the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance framework

The reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance (RE-AIM)24 framework is used to evaluate the implementation of EXCEL (refer to table 2 for a summary of outcomes), and has been used previously for the ACE exercise oncology programme implementation evaluation.15 This framework has also been used to assess health/lifestyle behaviours and their public health impact25–28 as a function of five factors: reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance. Reach and effectiveness are considered at the individual/participant level, while adoption, implementation and maintenance are factors typically specific to programs and sites. Reach is assessed by tracking referrals and enrolment into the EXCEL program. Referral types are classified as ‘direct HCP referral’, ‘indirect HCP referral’ or ‘self-referral’. Direct HCP referral is defined as a hub CEP receiving a referral directly from an HCP, whereas indirect HCP referrals are defined as a participant contacting the hub CEP after receiving information about EXCEL from an HCP (eg, HCP hands participant a study brochure in clinic). Self-referrals are defined as participants contacting the hub CEP without any interaction with an HCP (eg, participant heard about EXCEL through word of mouth, saw a poster or video ad). Enrolment is assessed by tracking the number and characteristics of eligible participants who enrol in EXCEL compared with those eligible who do not enrol. Reasons for study refusal will be tracked in addition to context specific needs to rural and remote areas such as distance to the nearest cancer centre and internet accessibility. Effectiveness of EXCEL is assessed through the functional fitness outcomes, patient-reported outcomes (PRO), and objective and self-reported physical activity measures that are detailed below. To assess adoption of EXCEL, characteristics of adopting and non-adopting spoke sites throughout rural and remote communities will be tracked. This includes tracking the number of referral sites (clinical sources), resources that are being used to refer to EXCEL, and the number of clinical personnel involved to implement EXCEL (ie, who is involved and how many personnel at the respective clinical site). Additional measures of adoption include fitness professional partnerships and characteristics, tracking the number of trained QEPs, number of exercise classes provided at each site, and both the number and type of fitness partnership that is implementing EXCEL (eg, individual QEPs, established fitness centres, fitness partners through healthcare settings, other sites). Implementation is tracked through fidelity checks, number of adverse events via the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V5.0,29 exercise class adherence (ie, attendance at each scheduled exercise session), and overall program costs per site (training, personnel/administrative support, other costs). Maintenance is assessed through long-term engagement with exercise/physical activity from both program sites (eg, the number of established exercise programmes in the community) and participants (eg, long-term physical activity levels and exercise program participation, assessed at follow-up time points up to 1 year after baseline program participation).

Table 2.

RE-AIM summary outcomes

| Construct | Reporting outcomes |

| Reach |

|

| Effectiveness |

|

| Adoption |

|

| Implementation |

|

| Maintenance |

|

CEPs, clinical exercise physiologists; EXCEL, EXercise for Cancer to Enhance Living Well; HCP, healthcare professional; QEPs, qualified exercise professionals; QOL, quality of life; RE-AIM, reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures are completed at four time points: (1) baseline; (2) 12 weeks (postintervention); (3) 24 weeks; and (4) 1 year (see table 3 for measurement time points). Online functional fitness assessments take place at baseline and 12-week time points, PROs are completed at each time point via REDCap,20 21 and wearable physical activity trackers are worn from baseline to the 24-week time point, with all wearable data stored in the Wearable Technology Research and Collaboration (We-TRAC), a level-4 secure database at the University of Calgary supported by funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). Qualitative data collected through semistructured interviews occur on a rolling basis as part of the 6-month recurring QI cycles.

Table 3.

Outcome measures and time points

| Domain/outcome | Measure | Baseline | 12 weeks | 24 weeks | 1 year |

| Physical fitness/function | |||||

| Shoulder range of motion | Shoulder flexion | X | X | ||

| Musculoskeletal fitness | 30 s sit-to-stand | X | X | ||

| Lower body flexibility | Chair sit-and-reach | X | X | ||

| Aerobic endurance | Two-minute step test | X | X | ||

| Balance | Single-leg stance | X | X | ||

| Patient-reported outcomes | |||||

| Physical activity | Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire | X | X | X | X |

| Health status | EQ-5D 5L | X | X | X | X |

| Quality of life | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General | X | X | X | X |

| Fatigue | Functional Assessment of Cancer Illness Therapy-Fatigue | X | X | X | X |

| Symptom burden | Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale | X | X | X | X |

| Barriers and facilitators | Exercise Barriers and Facilitators | X | X | X | X |

| Wearable activity tracker | |||||

| Objective physical activity | Garmin Vivo Smart4 | X | X | X | |

Notes: All Functional Fitness Assessments are completed online via ZOOM with results stored in REDCap, PROs are completed online via REDCap, and Objective Physical Activity is tracked and stored within We-TRAC online secure database.

EQ-5D 5L, EuroQol-5 Dimension 5 Level; WE-TRAC, Wearable Technology Research and Collaboration.

Functional fitness outcomes

Online functional fitness assessments are completed individually for each participant before and after the 12-week exercise intervention, with results recorded in REDCap. Assessments take approximately 30 min and follow the Canadian Society of Exercise Physiology’s Physical Activity Training for Health Protocol (CSEP-PATH).30 All assessors at each hub are trained in the assessment protocol and have exercise oncology experience and specific training. Primary assessors (CEPs) explain and demonstrate each assessment prior to the participants’ attempt. Secondary assessors (QEP or volunteers) help to ensure participant safety through additional monitoring during fitness assessments and record results, confirming results with the primary assessor after each assessment and during data entry. The functional fitness assessment includes measures of (1) self-reported height and weight (calculation of body mass index); (2) upper body flexibility via shoulder flexion range of motion31; (3) musculoskeletal fitness via a 30 s sit to stand assessment32 33; (4) lower body flexibility via a sit and reach assessment34; (5) aerobic endurance with a 2 min step test35 and (6) balance with a single-leg balance assessment.36 Due to the pandemic, modifications were required to assess participants to the best of our ability while maintaining scientific rigour (see online supplemental appendix 1 for comparison of in-person vs online assessment tools).

Shoulder flexion range of motion

Participants begin by sitting perpendicular to their computer camera in their chair, with arms by their side and palms facing inward. Participants are instructed to raise their arm in forward flexion, while remaining in the sagittal plane, with the goal of bringing their hand above their shoulder. Ensuring that the elbow is visible, this final position is held briefly while the CEP takes a screenshot on their computer screen. This process is repeated twice for each arm with the participant changing their chair position for the opposite arm. Range of motion is determined in degrees by measuring the final angle (screenshot) with a goniometer, using the head of the humerus, midline of the humerus and mid-axillary line as anatomical landmarks for consistent measurements.

30 s sit to stand

Participants start in a seated upright position (~43 cm chair) with arms across the chest and hands placed on opposite shoulders, with no contact on the back of the chair. Participants are then instructed to complete as many ‘sit to stands’ as possible within 30 s, with one ‘sit to stand’ defined as standing with full hip extension and arms remaining in the crossed-chest position. On a ‘ready-set-go’ cue, participants begin the assessment and the number of fully completed sit to stands within the 30 s time frame is recorded.

Chair Sit and Reach

Participants complete warm-up stretches before the test is conducted. They start in a seated position on the edge of a chair with one leg fully extended and ankle bent at 90°. Participants are then instructed to place one hand on top of the other (palms facing down), fully extend their arms and slowly reach forward while keeping their back and extended leg straight. They hold this stretch for 20 s, on each leg twice. The test is performed by repeating the same stretching movement in the warm-up, however, participants are then asked to measure the distance from their toes to their fingertips with a tape measure, which is then reported to the nearest±0.5 cm (+=fingers went beyond toes; 0 cm=fingers just touched toes; −=fingers did not reach toes). This process is repeated twice on both legs, with the highest number being reported for each leg.

2- min Step Test

Participants begin by standing perpendicular to the camera (ie, right leg facing the camera) while marching in place for 2 min. The target knee height is determined by having the participant measure the distance between the patella and iliac crest to find the midpoint of the thigh. Participants are then instructed to measure the distance from the thigh midpoint to the floor, and this distance is recorded by the assessor. If the participant is unable to determine the thigh midpoint, target knee height is set so that the thigh is parallel to the floor when marching. On a ‘ready-set-go’ cue, participants begin marching in place and the number of steps completed within the 2 min time frame on the leg facing the camera are recorded. Rate of perceived exertion (1–10)37 is recorded after the assessment has been completed.

Single leg balance

Participants start by standing on a flat surface, with shoes removed and eyes open, near a stable object (ie, chair or wall) for safety purposes, while facing the camera. Participants start with arms placed across their chest (or hands on hips) with feet shoulder width apart, and the assessment begins when the participant lifts one foot off the ground to the height of the opposite ankle with eyes remaining open. The assessment ends when either arms move away from the body, the raised foot touches the floor, the raised foot touches the standing leg, the raised leg moves from static position or the maximum limit of 45 s is reached. This process is repeated for the opposite leg and both balance times are recorded. If the assessments end before three seconds (due to the above listed conditions), they may repeat the test one more time and the longest duration is recorded.

Patient-reported outcomes

Questionnaires are completed online in REDCap at baseline, 12 weeks, 24 weeks, and 1 year. Self-reported physical activity is assessed using the modified Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire,38 which asks participants to recall average typical weekly exercise. Recall includes the frequency and duration of mild, moderate and vigorous aerobic activity, in addition to resistance and flexibility exercise. QOL is measured with the EuroQol-5 Dimension 5 Level (EQ-5D-5L)39 questionnaire and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G)40 questionnaire. The EQ-5D 5L measures general health as well as clinical and economic evaluations of healthcare. The FACT-G assesses QOL through four subdomains: physical, social/family, emotional and functional well-being. A final score is calculated from the sum of each subdomain score and is representative of overall QOL. Fatigue is assessed with the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue41 scale. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale-Revised42 assesses symptom burden from nine cancer related symptoms. Confidence (ie, self-efficacy) to participate in exercise is assessed with the Exercise Barriers and Facilitators questionnaire.43 Participants are asked to rank their confidence level to participate in exercise in certain situations (eg, when they feel nauseated, during bad weather, when there is lack of time). Barrier and facilitator self-efficacy scales are rated from 0% to 100% at 10% intervals. Interpretation of the scales are as follows: 0%–20%=not at all confident; 20%–40%=slightly confident; 40%–60%=moderately confident; 60%–80%=very confident and 80%–100%=extremely confident.

Objective physical activity levels

An activity tracker (Garmin Vivo Smart4) is used to capture objective data on exercise volume in a subset of the EXCEL participants. This is a commercially available activity tracker, and similar models have been found to be highly acceptable in cancer populations.44 45 Categories of meeting or not-meeting current exercise oncology guidelines11 are used as a marker of implementation success (ie, achieving 90 min of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week), as well as percent change in physical activity levels over time (baseline to postintervention; maintenance to follow-up). Activity trackers are distributed across hubs, based on the number of active participants at each hub and the number of trackers available. Participants are mailed the tracker after consent into the study and provided with instructions for use (an additional webinar is available to support use and troubleshoot common issues). Participants are instructed to wear the activity tracker for at least 10 hours per day, for 24 weeks, unless the device is charging. To be included for weekly physical activity calculations, at least four valid days are required. Valid days are defined as wearing the activity tracker for at least 10 hours/day46 47 with non-wear time being defined as not wearing the tracker for 60 consecutive minutes.48 Objective physical activity data are synced weekly and stored in the NSERC supported We-TRAC secure database at the University of Calgary. Collected data includes step counts and continuously recorded heart rate.

Semistructured interviews

The RE-AIM QuEST49 framework guides the semistructured qualitative interviews conducted as part of the 6-month recurring QI cycles. RE-AIM QuEST supplements quantitative measures by identifying and providing additional context to implementation barriers and can subsequently be used to help improve interventions in real time. Interviews occur with a purposive sample of participants, QEPs and HCPs to assess program implementation as well as outcomes from the exercise program itself. Sampling of participants includes considerations of location, participation age and cancer diagnosis, gender and activity levels at baseline. For QEPs and HCPs, sampling considers location, role and years of experience. This purposive sampling will ensure diverse views are collected across program participants and networks of HCPs and QEPs. The interviews are guided by interpretive description methodology,50 which has been used as a reliable qualitative guide within multiple health-related disciplines.51–53 Interviews are conducted either online (ie, ZOOM) or via telephone with trained study personnel. The qualitative analysis will provide a deeper understanding into program implementation and effectiveness from participant, HCP, and QEP perspectives, complementary and adding depth of potential understanding to the PROs and exercise data.

Sample size and statistical analysis

Based on previous work with the ACE study,15 with alpha level set at 0.05, we will need to enrol 1225 individuals to evaluate the effectiveness of the exercise intervention on our primary outcome of physical activity. Assuming a 15% drop-out rate, EXCEL will enrol 1500 individuals living with and beyond cancer from underserved rural and remote communities across Canada. The sample size estimation and proposed enrolment goal also take into account testing for differences in secondary outcomes. This helps ensure we will have sufficient power to examine the effectiveness of the exercise program on physical activity as well as to examine effects on secondary outcomes with consideration for covariates (ie, age, gender, primary cancer diagnosis, comorbidities and treatment received). In addition, due to physical restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, EXCEL will include participants from larger centres (ie, more urban locations) who do not have access to exercise oncology resources during this time. This inclusion is practical and ensures reach of the evidence-based exercise oncology resource during a time of restrictions to an underserved population who may benefit both physically and mentally during the pandemic by having access to exercise as a supportive cancer care resource. Analyses will, therefore, consider geographical location within subanalyses and/or as a covariate in the primary analysis.

Descriptive statistics will summarise participant demographic factors of age, sex, rural/urban, primary diagnosis of cancer, comorbidities, treatment received, including the procedure, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and exercise-related variables, as well as RE-AIM dissemination and implementation components. The indicators of effectiveness of implementation observed in this study will compare between groups at preimplementation and post-implementation using χ2 test or Student’s t-test, where appropriate. We will perform generalised linear mixed models to evaluate effectiveness changes in outcome measures over time. To deal with the geographical variance in effectiveness of implementation, we will employ multilevel modelling to examine site differences (ie, geographical location) in relation to reported physical activity levels and adherence to the exercise intervention. Quantitative data will be analysed using SAS statistical software (V.9.4). Qualitative analyses will be transcribed in ExpressScribe, coded in NVivo V.12, and thematically analysed by two independent authors per the interpretive description methodology.50

Patient and public involvement

Rural and remote individuals living with and beyond cancer, in addition to caregivers, have informed the EXCEL Project conception, delivery, assessments and implementation of our hub and spoke model to support the ‘Exercise and Educate’ training and intervention. Three individuals living with cancer from rural and remote communities make up our PAB, which has better informed our team in conceptualising and delivery the 12-week exercise intervention. Our team also engages with HCPs and QEPs while evaluating ongoing implementation components of the entire project (ie, referral support and exercise programme delivery) to continually improve the exercise programme experience for participants.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was received from the Health Research Ethics Board of Alberta (HREBA.CC-20-0098). Our team will disseminate information regarding the EXCEL study via quarterly newsletters sent to our partnership networks (ie, HCPs, QEPs and participants). Quarterly newsletters will include study updates on overall recruitment in addition to suggested changes and subsequent actions taken as a result of QI cycle feedback. EXCEL education sessions will also be provided to both HCPs (ie, during grand rounds) and QEPs (ie, wellness organisations) to continue to build partnership networks. Our team also plans to submit abstracts to research conferences and publish manuscripts that are guided by the RE-AIM framework. Analyses for conference presentations and published manuscripts will focus on the ongoing implementation efforts over the course of the 5-year study.

Discussion

Exercise is an evidence-based supportive cancer care resource that is both safe and effective at alleviating symptom burden, improving fitness, QOL3, and survival.54 55 Unfortunately, disparities in access to exercise for rural and remote individuals living with and beyond cancer prevent equitable potential realisation of these benefits.5 The EXCEL study aims to address this inequity by implementing and evaluating the effectiveness of bringing evidence-based exercise oncology programs to these communities via our hub and spoke model to facilitate online and in-person delivery when available. As the first large-scale study to disseminate, implement and evaluate the effectiveness of exercise for rural and remote individuals living with and beyond cancer, findings will inform how to reduce disparities in access to exercise as a supportive cancer care resource and ensure sustainable implementation of evidence-based exercise oncology interventions. This will enhance the physical and mental well-being, and ultimately the overall QOL, of more individuals living with and beyond cancer.

The final products for EXCEL dissemination and implementation across Canada will include training, program protocols (assessment and delivery), and established clinic-to-community partnerships that are sustainably supported within the hub and spoke model. Resources within each of these elements will be available to support the continued building and implementation of our exercise oncology ‘Exercise and Educate’ intervention, training and network development, linking participants in clinical settings to exercise as an evidence-based supportive cancer care resource that can be accessed within community settings (online and/or in-person). Building clinic-to-community pathways through the hub and spoke model to support exercise oncology as part of standard supportive cancer care is a unique feature and overall strength of the EXCEL study. Implementation will ‘bridge the gap’ from clinic to rural and remote communities, building referral sources at the clinical level and a network of trained fitness professionals at the community level. Bridging between these two networks is the critical role of the CEP, which is not yet a widespread role within cancer care. Building on our ‘pathways model’,56 57 CEP expertise ensures that referral to exercise resources is appropriately addressed through expert screening, understanding of tailored needs within an exercise setting, and supports access to safe and effective exercise resources that will meet participant needs. Ultimately, building exercise via EXCEL into standard supportive cancer care will equip individuals living with and beyond cancer with the resources to use exercise to manage their wellness, health, and overall QOL.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the additional members of the EXCEL Project Team, beyond core members and their trainees, which includes the following: Researchers and Clinicians: Kristin Campbell, Amanda Wurz, Rosemary Twomey, Scott Grandy, David Langelier, Robin Urquhart, Chris Blanchard, Erin McGowan, Travis Saunders, Danielle Bouchard, Robert Rutledge, Tallal Younis, Lori Wood, Stephanie Snow, Nicholas Giacomantonio, Miroslaw Rajda, Judith Purcell, Carolina Chamorro Vina, Shabbir Alibhai, Anil Abraham Joy, David Eisenstat, Beverly Wilson, Sarah McKillop, Danielle Briand, Terri Billard, Naomi Dolgoy, Paula Ospina-Lopez, Leslie Hill, Shaneel Pathak; Community Partners: Pam Manzara (City of Calgary-Calgary Recreation), and Sheena Clifford (Wellspring Calgary); Admin: Jacqueline Hochhausen; and all individuals living with and beyond cancer including those on our initial Participant Advisory Board: Duane Kelly, Gail Muir, Janice Wilson, and Judy Paterson; as well as those included on the initial grant proposal: Colin Robertson, Bill Richardson and Trevor Willmer.

Footnotes

Twitter: @MargieMcNeely@MargieMcneely, @DR_SantaMina, @danvsibley

Collaborators: EXCEL Project Team: Kristin Campbell, Amanda Wurz, Rosemary Twomey, Scott Grandy, David Langelier, Robin Urquhart, Chris Blanchard, Erin McGowan, Travis Saunders, Danielle Bouchard, Robert Rutledge, Tallal Younis, Lori Wood, Stephanie Snow, Nicholas Giacomantonio, Miroslaw Rajda, Judith Purcell, Carolina Chamorro Vina, Shabbir Alibhai, Anil Abraham Joy, David Eisenstat, Beverly Wilson, Sarah McKillop, Danielle Briand, Terri Billard, Naomi Dolgoy, Paula Ospina-Lopez, Leslie Hill, Shaneel Pathak.

Contributors: NC-R, MLM, MK, DSM, CC, LCC and GJF developed the study concept and protocol. NC-R and CWW drafted the manuscript in addition to JD, MLM, MK, DSM and CC contributing to major manuscript revisions and providing critical feedback. GC contributed to the sample size determination and development of the statistical analysis plan. MEs, EM, MEi, DS, JL, JC and TC all contribute to the acquisition of data for the EXCEL study outcomes, deliver the EXCEL study intervention, and provide critical feedback on the protocol prior to manuscript submission. We want to emphasise that every author listed will oversee the implementation of the protocol and contribute to the analysis and interpretation/application of study data.

Funding: EXCEL is funded by a Canadian Institute of Health Research and Canadian Cancer Society Cancer Survivorship Team Grant (Grant # 706673). Additional programme funding provided by the Alberta Cancer Foundation (Grant # N/A).

Disclaimer: Funding sources had no role in the study design and execution. Nor will they have a role in data interpretation.

Map disclaimer: The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries therein), or of any geographic or locational reference, does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

EXCEL Project Team:

Kristin Campbell, Amanda Wurz, Rosemary Twomey, Scott Grandy, David Langelier, Robin Urquhart, Chris Blanchard, Erin McGowan, Travis Saunders, Danielle Bouchard, Robert Rutledge, Tallal Younis, Lori Wood, Stephanie Snow, Nicholas Giacomantonio, Miroslaw Rajda, Judith Purcell, Carolina Chamorro Vina, Shabbir Alibhai, Anil Abraham Joy, David Eisenstat, Beverly Wilson, Sarah McKillop, Danielle Briand, Terri Billard, Naomi Dolgoy, Paula Ospina-Lopez, Leslie Hill, and Shaneel Pathak

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Weaver KE, Palmer N, Lu L, et al. Rural-urban differences in health behaviors and implications for health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control 2013;24:1481–90. 10.1007/s10552-013-0225-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, et al. Rural-Urban disparities in health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer 2013;119:1050–7. 10.1002/cncr.27840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rajotte EJ, Yi JC, Baker KS, et al. Community-Based exercise program effectiveness and safety for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2012;6:219–28. 10.1007/s11764-011-0213-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lawler S, Spathonis K, Masters J, et al. Follow-Up care after breast cancer treatment: experiences and perceptions of service provision and provider interactions in rural Australian women. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1975–82. 10.1007/s00520-010-1041-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Butow PN, Phillips F, Schweder J, et al. Psychosocial well-being and supportive care needs of cancer patients living in urban and rural/regional areas: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:1–22. 10.1007/s00520-011-1270-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levit LA, Byatt L, Lyss AP, et al. Closing the rural cancer care gap: three institutional approaches. JCO Oncol Pract 2020;16:422–30. 10.1200/OP.20.00174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ala A, Wilder J, Jonassaint NL, et al. COVID-19 and the uncovering of health care disparities in the United States, United Kingdom and Canada: call to action. Hepatol Commun 2021;5:1791–800. 10.1002/hep4.1790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Speck RM, Courneya KS, Mâsse LC, et al. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv 2010;4:87–100. 10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2012;62:242–74. 10.3322/caac.21142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cormie P, Atkinson M, Bucci L, et al. Clinical oncology Society of Australia position statement on exercise in cancer care. Med J Aust 2018;209:184–7. 10.5694/mja18.00199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, et al. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019;51:2375–90. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mina DS, Alibhai SMH, Matthew AG, et al. Exercise in clinical cancer care: a call to action and program development description. Current Oncology 2012;19:136–44. 10.3747/co.19.912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Courneya KS, Katzmarzyk PT, Bacon E. Physical activity and obesity in Canadian cancer survivors: population-based estimates from the 2005 Canadian community health survey. Cancer 2008;112:2475–82. 10.1002/cncr.23455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rogers LQ, Goncalves L, Martin MY, et al. Beyond efficacy: a qualitative organizational perspective on key implementation science constructs important to physical activity intervention translation to rural community cancer care sites. J Cancer Surviv 2019;13:537–46. 10.1007/s11764-019-00773-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McNeely ML, Sellar C, Williamson T, et al. Community-Based exercise for health promotion and secondary cancer prevention in Canada: protocol for a hybrid effectiveness-implementation study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e029975. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hardcastle SJ, Hince D, Jiménez-Castuera R, et al. Promoting physical activity in regional and remote cancer survivors (PPARCS) using wearables and health coaching: randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open 2019;9:e028369. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:4–23. 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012;50:217–26. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham ID. Knowledge translation in health care: moving from evidence to practice. John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap Consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bredin SSD, Gledhill N, Jamnik VK, et al. PAR-Q+ and ePARmed-X+: new risk stratification and physical activity clearance strategy for physicians and patients alike. Can Fam Physician 2013;59:273–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1322–7. 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health 2019;7:64. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE. Translating effective clinic-based physical activity interventions into practice. Am J Prev Med 2006;31:45–56. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ory MG, Altpeter M, Belza B, et al. Perceived utility of the RE-AIM framework for health Promotion/Disease prevention initiatives for older adults: a case study from the U.S. evidence-based disease prevention initiative. Front Public Health 2014;2:143. 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stoutenberg M, Galaviz KI, Lobelo F, et al. A pragmatic application of the RE-AIM framework for evaluating the implementation of physical activity as a standard of care in health systems. Prev Chronic Dis 2018;15:170344. 10.5888/pcd15.170344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.

- 30. Canadian Society of Exercise Physiology. CSEP-PATH: physical activity training for health 2021.

- 31. Kolber MJ, Hanney WJ. The reliability and concurrent validity of shoulder mobility measurements using a digital inclinometer and goniometer: a technical report. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2012;7:306–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eden MM, Tompkins J, Verheijde JL. Reliability and a correlational analysis of the 6MWT, ten-meter walk test, thirty second sit to stand, and the linear analog scale of function in patients with head and neck cancer. Physiother Theory Pract 2018;34:202–11. 10.1080/09593985.2017.1390803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Beam WC. A 30-S chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport 1999;70:113–9. 10.1080/02701367.1999.10608028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Max J, et al. The reliability and validity of a chair sit-and-reach test as a measure of hamstring flexibility in older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport 1998;69:338–43. 10.1080/02701367.1998.10607708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Development and validation of criterion-referenced clinically relevant fitness standards for maintaining physical independence in later years. Gerontologist 2013;53:255–67. 10.1093/geront/gns071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Franchignoni F, Tesio L, Martino MT, et al. Reliability of four simple, quantitative tests of balance and mobility in healthy elderly females. Aging 1998;10:26–31. 10.1007/BF03339630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Borg GA. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scale. Human Kinetics, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci 1985;10:141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pickard AS, De Leon MC, Kohlmann T, et al. Psychometric comparison of the standard EQ-5D to a 5 level version in cancer patients. Med Care 2007;45:259–63. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254515.63841.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:570–9. 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, et al. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the functional assessment of cancer therapy (fact) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997;13:63–74. 10.1016/S0885-3924(96)00274-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton symptom assessment scale. Cancer 2000;88:2164–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Verhulst S, et al. Exercise barrier and task self-efficacy in breast cancer patients during treatment. Support Care Cancer 2006;14:84–90. 10.1007/s00520-005-0851-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hardcastle SJ, Galliott M, Lynch BM, et al. Acceptability and utility of, and preference for wearable activity trackers amongst non-metropolitan cancer survivors. PLoS One 2018;13:e0210039. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Beg MS, Gupta A, Stewart T, et al. Promise of wearable physical activity monitors in oncology practice. J Oncol Pract 2017;13:82–9. 10.1200/JOP.2016.016857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gell NM, Grover KW, Humble M, et al. Efficacy, feasibility, and acceptability of a novel technology-based intervention to support physical activity in cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:1291–300. 10.1007/s00520-016-3523-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hartman SJ, Nelson SH, Weiner LS. Patterns of Fitbit use and activity levels throughout a physical activity intervention: exploratory analysis from a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e29. 10.2196/mhealth.8503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003-2004. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:875–81. 10.1093/aje/kwm390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Forman J, Heisler M, Damschroder LJ, et al. Development and application of the RE-AIM quest mixed methods framework for program evaluation. Prev Med Rep 2017;6:322–8. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thorne SE. Interpretive description: qualitative research for applied practice. Routledge,, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thorne S, Con A, McGuinness L, et al. Health care communication issues in multiple sclerosis: an interpretive description. Qual Health Res 2004;14:5–22. 10.1177/1049732303259618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Olsen NR, Bradley P, Lomborg K, et al. Evidence based practice in clinical physiotherapy education: a qualitative interpretive description. BMC Med Educ 2013;13:52. 10.1186/1472-6920-13-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cuthbert CA, Culos-Reed SN, King-Shier K, et al. Creating an upward spiral: A qualitative study of caregivers’ experience of participating in a structured physical activity programme. Eur J Cancer Care 2017;26:e12684. 10.1111/ecc.12684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ibrahim EM, Al-Homaidh A. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis: meta-analysis of published studies. Med Oncol 2011;28:753–65. 10.1007/s12032-010-9536-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, et al. Physical activity and survival after prostate cancer diagnosis in the health professionals follow-up study. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:726–32. 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.5226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mina DS, Sabiston CM, Au D, et al. Connecting people with cancer to physical activity and exercise programs: a pathway to create accessibility and engagement. Curr Oncol 2018;25:149–62. 10.3747/co.25.3977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wagoner CW, Capozzi LC, Culos-Reed SN. Tailoring the evidence for exercise oncology within breast cancer care. Curr Oncol 2022;29:4827–41. 10.3390/curroncol29070383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-063953supp001.pdf (46.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-063953supp002.pdf (136.6KB, pdf)