Abstract

Accumulating evidence sustains glial cells as critical players during central nervous system (CNS) development, homeostasis and disease. Olfactory ensheathing cells (OECs), a type of specialized glia cells sharing properties with both Schwann cells and astrocytes, are of critical importance in physiological condition during olfactory system development, supporting its regenerative potential throughout the adult life. These characteristics prompted research in the field of cell-based therapy to test OEC grafts in damaged CNS. Neuroprotective mechanisms exerted by OEC grafts are not limited to axonal regeneration and cell differentiation. Indeed, OEC immunomodulatory properties and their phagocytic potential encourage OEC-based approaches for tissue regeneration in case of CNS injury. Herein we reviewed recent advances on the immune role of OECs, their ability to modulate CNS microenvironment via bystander effects and the potential of OECs as a cell-based strategy for tissue regeneration.

Keywords: OECs, immunomodulation, neurotrophic factors, intercellular communication, neuroregeneration

1 Introduction

During the last decades, increasing evidence support the hypothesis that glial cells are important players in crucial aspects of neurogenesis, neuronal functions and diseases (1, 2). Indeed, glial cells guide neuronal migration during development, participate in synaptic formation and plasticity, regulate vasculature and blood–brain barrier (BBB), modulate neuroimmunity, and support neural regeneration (1–3). The term glia, from the Greek “γλíα”, meaning “glue”, was originally assigned assuming that these cells were responsible to keep neural cells together. In the adult central nervous system (CNS) three main types of glial cells can be distinguished: astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, deriving from neural crest, and microglia, which originate from the myeloid lineage. In the peripheral nervous system (PNS), Schwann cells represent the main class of glia. Olfactory ensheathing cells (OECs) are a type of specialized glia cells, restricted to the olfactory system, which play a crucial role in olfactory development and regeneration (4–6). Indeed, the olfactory system has a unique neurogenic niche where unlike most regions of the nervous system, olfactory sensory neurons retain a lifetime regeneration potential (4, 5). Since the olfactory neuroepithelium is in direct contact with the external environment, it has evolved a remarkable ability to recruit sensory neurons during normal cell turnover or after traumatic olfactory nerve injury (7, 8). This unique feature is now widely attributed to the presence of OECs, able to wrap olfactory axons and support olfactory receptor neurons turnover and axonal regeneration (9–11). OECs perform their axon growth-promoting properties and provide structural support by extending thin processes that envelop group of axons as an insulator ( Figure 1 ) (12, 13). Moreover, when new olfactory sensory neurons are generated from stem cells in the olfactory epithelium, OECs establish functional connections along the olfactory neuroaxis (8, 14).

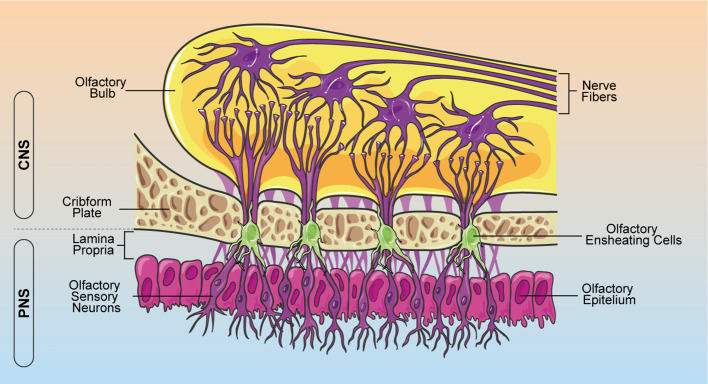

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of OEC localization within the olfactory system. OECs ensheath bundles of olfactory receptor axons along their course through the lamina propria in the PNS. Olfactory nerves and their associated OECs cross through the cribform plate into the CNS, making connections with the olfactory bulb. OEC, olfactory ensheathing cells; CNS, central nervous system; PNS, peripheral nervous system.

In contrast to neural crest-derived PNS glia and neural tube-derived CNS glia, OECs have generally been thought to originate from the olfactory placode (15). However, several studies show that the olfactory placode arises from ontogenetically heterogeneous sources of cells and OECs derive from neural crest, like Schwann cells (16–18). These cells are located in the lamina propria of the olfactory mucosa, as well as the outer layers of the olfactory bulbs, the inner and outer nerve fiber layers ( Figure 1 ) (19).

OECs share many properties with Schwann cells and astrocytes. They express some typical markers such as the p75 neurotrophic receptor (p75NTR), the polysialylated form of neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM), and, like astrocytes, they express the glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP), and the S100 proteins (20, 21). Furthermore, OECs are able to secret high level of growth factors, such as nerve growth factor (NGF), basic fibroblast growth factors (bFBF), brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), neurotrophins NT4, NT5 and neuregulins, which exhibit important functions as neuronal supporting elements (13, 22–24).

In recent years, significant advances have been made in cellular-based therapies, which focus on the restoration, regrowth or replacement of damaged or dysfunctional cells, tissues and organs, in order to treat neurodegenerative diseases (25) and CNS injuries (26–28). Moreover, cell-based approaches, including OEC grafts, have been reported to induce beneficial effects in spinal cord injury (SCI) models. In addition to neuroprotective mechanisms, axon regeneration and remyelination were observed, leading to significant sensory and locomotor functions amelioration (29–31). Thus, OEC transplantation is proposed as a potential therapeutic strategy for SCI, due to their unique characteristics, such as anti-neuroinflammation, growth-promoting factor secretion, and debris clearance activity. However, there is a lack of in-depth studies focusing on the phagocytic function of these cells, particularly the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in this intricate process and on the synergistic effects with neural and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in improving cell differentiation. Exploring these unique features will lead to a better understanding of the role of OECs in development and regeneration and will identify how the use of OECs can be optimized for neural regeneration therapies. These approaches may benefit from accumulating evidence pointing out a significant role of checkpoint therapy in inducing regeneration upon CNS injury (32). Herein we reviewed the current knowledge about the immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties of OECs in neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration and during stem cell differentiation. Owing to the strong pro-regenerative properties of OECs, and their unique ability to promote stem cell differentiation, we explored the potential of OEC transplantation for tissue regeneration.

2 Immune role of OECs

The olfactory system is continuously exposed to various pathogens since the primary olfactory neurons are in direct contact with the external environment (7, 8). However, most cases of CNS infections do not occur through the olfactory system. In this scenario OECs play a crucial role in protecting CNS structures. Specifically, they participate in innate immune responses, secrete immunoregulatory molecules and exert their phagocytic activity thus maintaining microenvironmental homeostasis, supporting neuron survival and axonal growth (33–35).

2.1 Phagocytic activity of OECs

CNS lesions are characterized by neuronal degeneration and death, and by the persistence of cellular and myelinated debris that create an adverse environment for neural survival, germination of neurites and renewal of neurons (36, 37). Since olfactory receptor neurons renew themselves throughout lifetime, a large amount of apoptotic debris is generated continuously (35). Several studies support phagocytic functions of OECs throughout life (35, 38) especially following injury (38, 39). In fact, by switching from a resting state to a phagocytic phenotype to remove axonal debris and bacteria, they protect the olfactory nerve from microbial infections (35, 40, 41). A combination of morphological and phenotypic changes distinguishes reactive OECs from their resting state, including cytoskeletal hypertrophy and rearrangement (34, 42). However, the identification of specific molecular markers capable of discriminating between quiescent and reactive OECs could better elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying their activation.

While Schwann cells participate in debris removal mainly by increasing the secretion of several pro-inflammatory molecules, thus recruiting professional phagocytes, including macrophages and neutrophils (43), OECs operate differently (38, 44). Wright et al. showed that OECs repel macrophages in co-culture, by expressing the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), which would explain the absence of macrophages in the olfactory nerve bundles (45).

In vitro studies reported that OECs possess several phagocytic-related receptors, including toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), phosphatidylserine and mannose receptors (34, 46, 47). Particularly, during apoptosis, olfactory neurons display the “eat me” signal phosphatidylserine, recognized by OEC phosphatidylserine receptor, leading to the engulfment of apoptotic and necrotic cell debris (33, 44). Milk fat globule-EGF factor 8 (MFGE-8), which interacts with integrin receptors (48), is a bridging molecule that participates in several cell surface-mediated regulatory events. Li et al. demonstrated in vitro that OECs express MFGE-8 when apoptotic debris is added to the culture (49). Moreover, OECs have been reported to adopt a “microglia-like” phenotype showing high levels of CD11 expression after their transplantation into the X-irradiated spinal cord of female Sprague Dawley rats (50). However, in vitro immunolabelling of OECs has revealed that they do not express this microglial marker in physiological conditions (34). Interestingly, Nazareth et al. reported that OECs produce less pro-inflammatory cytokines, compared to Schwann cells and macrophages when exposed to necrotic bodies (37). Conversely, some anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) promote OEC phagocytic activity (49).

In summary, the phagocytic activity of OECs plays a crucial role in creating a favorable environment to promote neuronal turnover, aiding the overall process of neuronal regeneration. Hence, this peculiar feature of OECs may be particularly useful for neural repair therapies including their transplantation after SCI.

2.2 OEC-mediated effects during neuroinflammation

As abovementioned, OECs show several unique properties of inflammatory cells, allowing them to modulate immune responses and neuronal pro-regenerative processes. Overall, inflammation is thought to hinder cell differentiation and regeneration but, although OECs are able to secrete a range of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines after injury or infections, they simultaneously promote nervous regeneration.

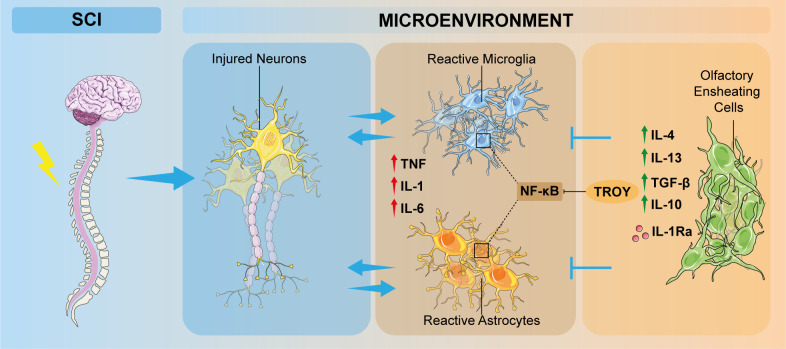

Following SCI, resident immune cells, including microglia and astrocytes, are activated by injured-released inflammatory stimuli (51). Indeed, the microenvironment of lesioned CNS switch towards pro-apoptotic and anti-regenerative milieu. Particularly, inflammatory responses in SCI are mainly mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines secreted by reactive astrocytes and microglia. In this scenario, M1-polarized microglia induces astrocyte activation, resulting in chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (CSPG) deposits and astrocytic scar formation, which limits the spread of inflammation but at the same time hampers axon regeneration (52). Concomitantly, glial cell activation causes the release of specific chemokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, and TNF. These cytokines, by activating their respective cascades, amplify inflammatory responses, alter the microenvironment and promote cell death, therefore blocking axonal regeneration ( Figure 2 ) (53, 54). As a result, inflammatory response induces secondary tissue damage with detrimental consequences to neural tissue and its functions (55). In general terms, inflammatory response maintains a dynamic balance of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine release; therefore, understanding the modulation of the inflammatory response mediated by OECs, could be a successful strategy to improve neuronal functional outcome after CNS injury.

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of the involvement of OECs in inflammation modulation after SCI. Neuronal damage induces pathological increasing of inflammatory responses, which promotes microglia polarization from a resting state to a M1-phenotype and astrocyte activation. OECs are able to modulate these inflammatory events by interacting directly or indirectly with microglia and astrocytes, thus ameliorating the detrimental condition of the altered microenvironment. OEC, olfactory ensheathing cell; SCI, spinal cord injury; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β, IL-1Ra: interleukin-1 receptor antagonist.

OECs are reported to express chemokines/cytokines and their cognate receptors, such as chemokine (CXC motif) ligand 1 (CXCL1), a neurotrophic chemoattractant, which may have a role during embryogenesis or after OECs transplantation in the injured site, CXCL12, CXCL4, chemokine (CX3C motif) ligand 1 (CX3CL1) (56) that have been proven to play pivotal roles in neuroinflammation, acting as a signaling factor for the recruitment of neutrophilis and various leucocytes (57). The inflammatory monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), and its receptor CCR2 specifically mediates monocytes chemotaxis, which results in the recruitment of macrophages to the site of injury. Moreover, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)-mediated signaling pathway, responsible for microglia and astrocytes activation after SCI, is activated by TROY, a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily, which has been detected via in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry investigations in the olfactory system (58). OECs or OEC-released molecules are able to inhibit NF-κB activation, so exerting a neuroprotective role after CNS injury. OECs also release several signaling molecules, such as TNF and IL-1β, to recruit macrophages, thus modulating inflammation and neurodegeneration (14, 44, 59). In this context, OECs could modulate microglia-astrocyte responses by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10, IL-13 and TGF-β, capable to downregulate the pro-inflammatory factors IL-1β, TNF and IL-6 ( Figure 2 ) (60–62). A recent study showed that IL-1α and IL-1β, which are significantly involved in inflammatory responses, were down-regulated after OEC transplantation at the injury site. This response is probably related to IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) mechanism, which is a competitive inhibitor of IL-1 by binding to its receptor ( Figure 2 ). Therefore, OECs, reaching the site of the lesion, are subjected to pro-inflammatory factors released by the activated microglia, and secrete IL-1Ra in response, thus reducing microglial activation and pro-inflammatory factor production and limiting microglia-mediated pro-inflammatory cytokine release (63).

It is worth noticing that the abovementioned OEC-derived anti-inflammatory factors participate in modulating cell survival, proliferation and migration, thus reducing glial scar and promoting regeneration after SCI (64). IL-4 and TGF-β have a direct impact on neural survival given their modulatory effects on acute and chronic immune cell responses and on their expression of detrimental molecules including nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROS), caspase and their secretion of neurotrophins (65).

Taken together these findings suggest that OECs delay the activation of microglia or macrophages and reduce the peak of the immune response, leading to neuroprotection against inflammatory damage.

3 OEC bystander effects on cell fate and differentiation

The ability of OECs in regulating neuroprotection is enhanced by the release of several protective factors in the microenvironment as OEC-conditioned medium (OEC-CM) promotes the differentiation of neural stem cells (NSCs) (66). Specifically, using OEC-CM, it has been shown that soluble factors larger than 30 kDa, which are secreted by OECs, promote migration, differentiation and maturation of NSCs within 7 days. By immunocytochemical analysis, it has been shown that NSCs in contact with OEC-CM, exhibited an up-regulation of neurofilament (NF), beta-III-tubulin (TUJ1), GFAP and a down-regulation of nestin, suggesting a differentiation of NSCs toward neuronal and astrocytic lineages. In addition, the presence in NSCs of synapsin-1, which is involved in the neurotransmitter release mechanism, has also been demonstrated, supporting the effect of OEC-CM in driving and/or stimulating neuronal differentiation. This study also claims that differentiation of NSCs, promoted by OECs, also occurs through indirect contact (67). OECs also exert their trophic effects directly through the secretion of factors involved in neurogenesis, neural differentiation and response, including both NGF and BDNF, small proteins including neurturin (NTN), CNTF, GDNF (68, 69), and heavier soluble factors including secreted protein acidic and cysteine rich (SPARC), sonic hedgehog protein (SHH), matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP 2), fibronectin, and laminin (70–72) ( Table 1 ). Moreover, TGF-β3 secreted by OECs is involved in the regulation of neuronal differentiation, negatively regulating Yes-associated protein (YAP) (76). The potential of OECs to induce differentiation of NSCs into neurons has also been demonstrated by functional electrophysiological studies that showed that NSC-derived neurons exposed to OEC-CM acquire active electrophysiological properties, expressing sodium and potassium channels suitable for onset of action potentials similar to primary neuronal cells (66). In vivo studies demonstrated that OECs are able to promote NSC differentiation into dopaminergic neurons or cholinergic neurons, pointing out that OECs can induce NSC differentiation toward a specific neuron subtype (77, 78). OEC-induced effects would be exerted by influencing Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway, which is important in the proliferation and self-renewal of adult NSCs (79, 80). Indeed, it was shown that CM from Wnt-activated OECs (wOEC-CM) stimulates the proliferation and differentiation of NSCs, by increasing the percentage of Ki67/Sox2 double positive cells, maintaining Nestin expression under differentiation condition, but also stimulating NSC differentiation into Tuj1-positive neurons (81).

Table 1.

OEC released factors involved in neural differentiation and neurogenesis.

| Factors | Molecular weight | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) | 26.7 kDa | Involved in the promotion of Schwann cell migration | (69) |

| Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor (CNTF) | 22.9 kDa | Support neurogenesis | (67) |

| Fibronectin | 440 kDa | Promote neural progenitor cell migration | (73) |

| Laminin | 400 kDa | Involved in neural progenitor cell differentiation | (74) |

| Matrix Metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) | 67 kDa | Important for neural cell migration | (75) |

| Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) | 26.7 kDa | Involved in the promotion of Schwann cell migration | (69) |

| Neurturin (NTN) | 23.6 kDa | Support neurogenesis | (67) |

| Sonic Hedgehog protein (Shh) | 67 kDa | Induce NSC differentiation into neurons | (72) |

| Secreted Protein Acidic and Cysteine Rich (SPARC) | 43 kDa | Implicated in neural differentiation and in neurite extension | (70) |

Many reports have shown that hypoxic preconditioned stem cells survive longer, exhibiting an efficient neuronal differentiation and showing enhanced paracrine effects (82, 83). Wang et al. demonstrated that CM from hyperthermia-conditioned OECs induces NSC neural differentiation more efficiently, thanks to the upregulation of HIF-1α, leading to synergistic effects that improve differentiation (84). By using OEC-CM under hypoxic condition, olfactory mucosa MSCs (OM-MSCs) are stimulated to differentiate into dopaminergic neurons. Specifically, OEC-CM under hypoxia upregulates transcriptional factors mediated by HIF-1α and it is involved in the development of dopaminergic neurons from OM-MSCs (85).

MSCs, including adipose tissue-derived MSCs (ASCs), are a type of non-hematopoietic stem cells which under appropriate conditions can give rise to several precursors (86–90). OEC-CM is also implicated in the differentiation ASCs toward a neuronal phenotype (91). ASCs treated with OEC-CM expressed markers of progenitor and mature neurons, including Nestin, protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5), and microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) in a time-dependent manner and exhibited neuron like morphology, while they were negative for GFAP and A2B5, markers of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, respectively (92). In addition, although a significant increase of Nestin, PGP 9.5, Synapsin I, and GFAP was reported, MAP2 was identified as the most representative, thus suggesting a greater tendency toward the neuronal phenotype (93). This result is confirmed by another study where a neural-like connexin expression was induced in ASCs after OEC-CM treatment (94–98). On the other hand, when ASCs were co-cultured with OECs using 3D collagen scaffolds, they differentiated into cells with OEC-like morphology and were reported to be p75NTR and Nestin positive and GFAP negative. These co-cultured ASCs also expressed various functional markers of mature OECs: BDNF, GDNF and the myelin proteolipid protein (PLP). Thus, these results demonstrate that using specific scaffolds, ASCs might differentiate into OEC-like cells in vitro (99). Altogether, it can be inferred that OECs play a key role in cell differentiation toward a neural type and are able to prompt MSC differentiation towards neural phenotype and even to mature OECs. As such, these intrinsic properties of OECs may be relevant for therapeutic approaches aiming at CNS tissue regeneration.

4 OECs for tissue regeneration and transplantation

In recent years, OECs have been investigated for their reparative ability following acute or chronic lesions that involve CNS. As already mentioned, it appears that OECs may play a crucial role in the treatment of SCI (100–103). Usually, SCI severely affects CNS microenvironment, leading to a series of deleterious processes such as inflammation and hypoxia, and progressive cell death (104). OECs exhibit several characteristics that enable them to have beneficial effects in neuro-repairing potential. They are able to reduce the inflammatory response following injury, thereby decreasing the size of the glial scar and promoting angiogenesis. In addition, they promote regrowth, plasticity and remyelination of axons (105–107). OECs can also interact with resident cell populations, particularly astrocytes and meningeal cells, either within the window of the glial scar formation or once the scar has already established (108, 109). Thus, in addition to penetrate glial tissue, OECs also produce extracellular matrix proteases and can reduce astrocytic reactivity. Overall, these properties may reduce glial scar formation and all consequential limitations, which strongly limit axonal regrowth and injury bridging (110). In SCI animal models, grafted OECs exhibit the ability to promote axon regrowth and propagation (30, 100, 111). In particular, OEC transplantation improves sensorimotor and autonomic nerve recovery, also reducing neuropathic pain due to SCI. OECs secrete a number of neurotrophic factors, which allow the establishment of a favorable microenvironment for the regrowth of damaged axons. Undoubtedly, it is crucial to have functional recovery in transplanted animals in order to consider OEC transplants a successful therapy for the treatment of SCI (107). A study of Ramon-Cueto et al., revealed that adult rats undergoing spinal cord resection and subsequent OEC transplantation, showed both functional and structural recovery. In particular, from 3 to 7 months after surgery, all transplanted animals improved locomotor functions and sensorimotor reflexes (103). To show actual recoveries in transplanted animals, electrophysiological studies were also carried out, demonstrating that animals with transplanted OECs not only exhibited functional recovery, but also showed recovery of action or evoked potentials (112, 113). Studies on OEC transplantation have also been carried out in human clinical in many countries around the world. Completed clinical trials have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of OEC transplantation, but recovery in patients is often highly variable. This variability may be related to a number of factors, such as difficulties in establishing master cell banks and working cell banks, cell purity, and transplantation techniques. Forty-four eligible trials, involving 1,266 SCI patients, investigated several cell-based treatments to improve functional independent misure (FIM) score. Among them, OEC transplantation proved to ameliorate the FIM score at 6 months, thus improving disease prognosis (114). However, a common consequence in these studies is the poor survival of transplanted cells, with survival rates ranging from 0.3 percent to 3 percent. This issue is probably related to the fact that when OECs are isolated, expanded in vitro, and then transplanted into the injury site, their therapeutic potential is reduced, probably due to bleeding, damaged tissue and anatomical structures and hostile microenvironment present in the lesioned area (115–117). Therefore, in vitro models challenging OECs, by mimicking the injured tissue microenvironment, are needed. For example, it has been found that preconditioned OECs showed increased migratory, phagocytic and immunomodulatory capacities. To improve their efficacy and yield upon graft, cells could be then exposed to a low oxygen level, or they could grow into three-dimensional scaffolds before being transplanted into the lesion (116).

Another effective strategy for SCI treatment is the co-transplantation of NSCs and OECs. Indeed, co-grafting of NSCs and OECs ameliorate SCI by inhibiting receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 (RIP3)/mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL)-mediated necroptosis and stimulating NSC proliferation in the medulla. Evidence reports that OECs are able to increase NSCs proliferation and differentiation and, importantly, co-grafts significantly support NSCs survival, opening the way for a potential stem cells-based regenerative approach. In this way, neural regeneration could be improved exploiting the synergistic effect of NSCs and OECs (118). In addition, a study by He Y. t al., showed that curcumin-activated OECs (aOECs) effectively improve neuronal differentiation of NSCs even under conditions of inflammation, and co-transplantation of aOECs and NSCs enhaces the neurological recovery of rats after SCI, providing a hopeful strategy for SCI repair by co-transplantation of aOECs and NSCs (119). Besides OEC transplantation, OECs-CM has also been shown to have therapeutic effects for SCI, enhancing functional recovery and axonal regeneration probably because of various factors previously secreted by OECs in their culture medium (120). In this context, exosomes derived from OECs (OEC-Exo) also promote neuronal survival and improve axon condition, facilitating functional recovery following SCI. OEC-Exo can be internalized by microglia/macrophages and are able to modulate their polarization. The main ability of OEC-Exo consists in an immunomodulatory function that shape immune microenvironment towards a pro-regenerative phenotype, supporting OEC-Exo as neuroprotective and regenerative strategy for CNS diseases (121). Furthermore, OECs secrete, via exosomes, alpha B-crystallin (CryAB), an anti-inflammatory protein, leading to an intercellular immune response. Thus, CryAB, together with other OEC-secreted factors, may ameliorate the hostile growth environment created by neurotoxic reactive astrocytes following CNS injury (122).

SCI microenvironment is characterized by a prevalence of M1-like pro-inflammatory macrophages over M2-like. This phenomenon results in a microenvironment that is unfavorable for cell differentiation and regeneration. Therefore, for a better potential regenerative strategy, a fundamental role is played by immune cell modulation (123, 124). Macrophages are a prominent population in SCI microenvironment, also able to alter the activity of transplanted OECs. However, the interaction appears to be reciprocal, as OECs express MIFs and can also lead to reduced macrophage recruitment in vitro (45). To enhance this interaction in favor of OECs by improving the cellular microenvironment at the injury level, a study of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) modulation in the SCI microenvironment was carried out. It was shown that CM from macrophages exposed to PDGF or combined VEGF and PDGF, under inflammatory conditions, increased OEC phagocytosis, also modulating the expression of genes related to nerve repair. Specifically, both PDGF and VEGF/PDGF reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF) by decreasing NF-κB translocation, promoting phagocytosis of myelin debris. For this reason, administering growth factors before OEC transplantation could improve transplant success and neural recovery (125).

5 Conclusions

Our knowledge of the properties, functions, and therapeutic potential of OECs is markedly increasing. OECs can be considered as a good candidate for cell-replacement and have shown remarkable capabilities to exert neuroprotective mechanisms. The uniqueness of OECs appears to collaborate with other recruited cell types to orchestrate the molecular signaling responsible for resolving the inflammatory state and creating a favorable environment for neural regeneration.

However, the development of human OEC transplants for clinical application in SCI still requires an in-depth understanding of the cellular and molecular biological characteristics of OECs. It seems now clear that OECs expanded in vitro and grafted back in vivo show limited therapeutic potential, probably due to the hostile microenvironment at the damaged tissue. In fact, a major issue limiting spinal cord regeneration is also the poor survival of transplanted cells (126). In order to describe the therapeutic potential of OECs it appears critical to characterize OEC gene expression aiming at identifying OEC-specific markers. Indeed, the most used marker to identify OECs, p75NTR, is also expressed in vitro by Schwann cells (10), astrocytes and lamina propria MSCs (127). The lack of a solid method for OECs identification, isolation and purification is among the main factors limiting reproducibility and reliability of transplantation studies. Furthermore, without a unique method for OEC identification, it is possible that their repair capacity is influenced by the presence of the various cells types co-existing alongside OECs.

One of the most effective approaches in transplantation of OECs is co-grafting with NSCs, achieving better therapeutic effects. Indeed OECs, by releasing trophic factors into the microenvironment, also play an important role in promoting the differentiation of NSCs, able to change their morphology, stimulating their differentiation towards mature neurons.

Despite the variability of results reported and limiting factors, OECs should be considered as valuable cell-based approach for SCI and a potential candidate to promote cell differentiation and regeneration. Finally, a deeper understanding of OEC anti-inflammatory properties and their interplay with other cells involved in neuro-repairing is crucial for the development of future therapies, using transplantation of OECs to treat neural injuries.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: SD, SD’A, NV, and RP; writing—original draft preparation: SD, SD’A, NV, and RP; writing—review and editing: all authors; visualization: SD, SD’A, CA, AP, and FT; supervision: DLF, AZ, RG, DT, GLV, NV, and RP. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Servier Medical Art (smart.servier.com, accessed on 13 November 2022)

Funding

SD, CA, and AP were supported by the PhD program in Biotechnologies, Biometec, University of Catania. FT was supported by Fondazione Umberto Veronesi. NV was supported by the PON AIM R&I 2014-2020-E66C18001240007.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Lobsiger CS, Cleveland DW. Glial cells as intrinsic components of non-cell-autonomous neurodegenerative disease. Nat Neurosci (2007) 10(11):1355–60. doi: 10.1038/nn1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barres BA. The mystery and magic of glia: A perspective on their roles in health and disease. Neuron (2008) 60(3):430–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang X, Jiang C, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Fan H, Zhang Y, et al. The promoting effects of activated olfactory ensheathing cells on angiogenesis after spinal cord injury through the PI3K/Akt pathway. Cell Biosci (2022) 12(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s13578-022-00765-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Graziadei GA, Graziadei PP. Neurogenesis and neuron regeneration in the olfactory system of mammals. II. Degeneration and reconstitution of the olfactory sensory neurons after axotomy. J Neurocytol (1979) 8(2):197–213. doi: 10.1007/BF01175561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Graziadei PP, Graziadei GA. Neurogenesis and neuron regeneration in the olfactory system of mammals. i. morphological aspects of differentiation and structural organization of the olfactory sensory neurons. J Neurocytol (1979) 8(1):1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF01206454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mackay-Sim A, Kittel P. Cell dynamics in the adult mouse olfactory epithelium: A quantitative autoradiographic study. J Neurosci (1991) 11(4):979–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-04-00979.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schwob JE. Neural regeneration and the peripheral olfactory system. Anat Rec (2002) 269(1):33–49. doi: 10.1002/ar.10047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leung CT, Coulombe PA, Reed RR. Contribution of olfactory neural stem cells to tissue maintenance and regeneration. Nat Neurosci (2007) 10(6):720–6. doi: 10.1038/nn1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Doucette R. Glial influences on axonal growth in the primary olfactory system. Glia (1990) 3(6):433–49. doi: 10.1002/glia.440030602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen CR, Kachramanoglou C, Li D, Andrews P, Choi D. Anatomy and cellular constituents of the human olfactory mucosa: A review. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base (2014) 75(5):293–300. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1361837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schwob JE, Jang W, Holbrook EH, Lin B, Herrick DB, Peterson JN, et al. Stem and progenitor cells of the mammalian olfactory epithelium: Taking poietic license. J Comp Neurol (2017) 525(4):1034–54. doi: 10.1002/cne.24105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rieger A, Deitmer JW, Lohr C. Axon-glia communication evokes calcium signaling in olfactory ensheathing cells of the developing olfactory bulb. Glia (2007) 55(4):352–9. doi: 10.1002/glia.20460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ursavas S, Darici H, Karaoz E. Olfactory ensheathing cells: Unique glial cells promising for treatments of spinal cord injury. J Neurosci Res (2021) 99(6):1579–97. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roet KC, Verhaagen J. Understanding the neural repair-promoting properties of olfactory ensheathing cells. Exp Neurol (2014) 261:594–609. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shields SD, Moore KD, Phelps PE, Basbaum AI. Olfactory ensheathing glia express aquaporin 1. J Comp Neurol (2010) 518(21):4329–41. doi: 10.1002/cne.22459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barraud P, Seferiadis AA, Tyson LD, Zwart MF, Szabo-Rogers HL, Ruhrberg C, et al. Neural crest origin of olfactory ensheathing glia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2010) 107(49):21040–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012248107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Forni PE, Taylor-Burds C, Melvin VS, Williams T, Wray S. Neural crest and ectodermal cells intermix in the nasal placode to give rise to GnRH-1 neurons, sensory neurons, and olfactory ensheathing cells. J Neurosci (2011) 31(18):6915–27. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6087-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Katoh H, Shibata S, Fukuda K, Sato M, Satoh E, Nagoshi N, et al. The dual origin of the peripheral olfactory system: Placode and neural crest. Mol Brain (2011) 4:34. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-4-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yao R, Murtaza M, Velasquez JT, Todorovic M, Rayfield A, Ekberg J, et al. Olfactory ensheathing cells for spinal cord injury: Sniffing out the issues. Cell Transpl (2018) 27(6):879–89. doi: 10.1177/0963689718779353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pellitteri R, Spatuzza M, Stanzani S, Zaccheo D. Biomarkers expression in rat olfactory ensheathing cells. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) (2010) 2(1):289–98. doi: 10.2741/s64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barton MJ, John JS, Clarke M, Wright A, Ekberg J. The glia response after peripheral nerve injury: A comparison between schwann cells and olfactory ensheathing cells and their uses for neural regenerative therapies. Int J Mol Sci (2017) 18(2):287–306. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boruch AV, Conners JJ, Pipitone M, Deadwyler G, Storer PD, Devries GH, et al. Neurotrophic and migratory properties of an olfactory ensheathing cell line. Glia (2001) 33(3):225–9. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stepanova OV, Voronova AD, Chadin AV, Fursa GA, Karsuntseva EK, Valikhov MP, et al. Neurotrophin-3 enhances the effectiveness of cell therapy in chronic spinal cord injuries. Bull Exp Biol Med (2022) 173(1):114–8. doi: 10.1007/s10517-022-05504-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Russo C, Patane M, Russo A, Stanzani S, Pellitteri R. Effects of ghrelin on olfactory ensheathing cell viability and neural marker expression. J Mol Neurosci (2021) 71(5):963–71. doi: 10.1007/s12031-020-01716-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lo Furno D, Mannino G, Giuffrida R. Functional role of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of chronic neurodegenerative diseases. J Cell Physiol (2018) 233(5):3982–99. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Golchin A, Shams F, Kangari P, Azari A, Hosseinzadeh S. Regenerative medicine: Injectable cell-based therapeutics and approved products. Adv Exp Med Biol (2020) 1237:75–95. doi: 10.1007/5584_2019_412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mannino G, Russo C, Longo A, Anfuso CD, Lupo G, Lo Furno D, et al. Potential therapeutic applications of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of eye diseases. World J Stem Cells (2021) 13(6):632–44. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v13.i6.632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mannino G, Cristaldi M, Giurdanella G, Perrotta RE, Lo Furno D, Giuffrida R, et al. ARPE-19 conditioned medium promotes neural differentiation of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. World J Stem Cells (2021) 13(11):1783–96. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v13.i11.1783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Menezes K, Nascimento MA, Goncalves JP, Cruz AS, Lopes DV, Curzio B, et al. Human mesenchymal cells from adipose tissue deposit laminin and promote regeneration of injured spinal cord in rats. PloS One (2014) 9(5):e96020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lu J, Feron F, Mackay-Sim A, Waite PM. Olfactory ensheathing cells promote locomotor recovery after delayed transplantation into transected spinal cord. Brain (2002) 125(Pt 1):14–21. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pearse DD, Sanchez AR, Pereira FC, Andrade CM, Puzis R, Pressman Y, et al. Transplantation of schwann cells and/or olfactory ensheathing glia into the contused spinal cord: Survival, migration, axon association, and functional recovery. Glia (2007) 55(9):976–1000. doi: 10.1002/glia.20490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taylor MJ, Thompson AM, Alhajlah S, Tuxworth RI, Ahmed Z. Inhibition of Chk2 promotes neuroprotection, axon regeneration, and functional recovery after CNS injury. Sci Adv (2022) 8(37):eabq2611. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abq2611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. He BR, Xie ST, Wu MM, Hao DJ, Yang H. Phagocytic removal of neuronal debris by olfactory ensheathing cells enhances neuronal survival and neurite outgrowth via p38MAPK activity. Mol Neurobiol (2014) 49(3):1501–12. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8588-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hao DJ, Liu C, Zhang L, Chen B, Zhang Q, Zhang R, et al. Lipopolysaccharide and curcumin Co-stimulation potentiates olfactory ensheathing cell phagocytosis Via enhancing their activation. Neurotherapeutics (2017) 14(2):502–18. doi: 10.1007/s13311-016-0485-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Su Z, Chen J, Qiu Y, Yuan Y, Zhu F, Zhu Y, et al. Olfactory ensheathing cells: the primary innate immunocytes in the olfactory pathway to engulf apoptotic olfactory nerve debris. Glia (2013) 61(4):490–503. doi: 10.1002/glia.22450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vargas ME, Barres BA. Why is wallerian degeneration in the CNS so slow? Annu Rev Neurosci (2007) 30:153–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nazareth L, Shelper TB, Chacko A, Basu S, Delbaz A, Lee JYP, et al. Key differences between olfactory ensheathing cells and schwann cells regarding phagocytosis of necrotic cells: implications for transplantation therapies. Sci Rep (2020) 10(1):18936. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75850-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nazareth L, Lineburg KE, Chuah MI, Tello Velasquez J, Chehrehasa F, St John JA, et al. Olfactory ensheathing cells are the main phagocytic cells that remove axon debris during early development of the olfactory system. J Comp Neurol (2015) 523(3):479–94. doi: 10.1002/cne.23694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wewetzer K, Kern N, Ebel C, Radtke C, Brandes G. Phagocytosis of O4+ axonal fragments in vitro by p75- neonatal rat olfactory ensheathing cells. Glia (2005) 49(4):577–87. doi: 10.1002/glia.20149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Panni P, Ferguson IA, Beacham I, Mackay-Sim A, Ekberg JA, St John JA. Phagocytosis of bacteria by olfactory ensheathing cells and schwann cells. Neurosci Lett (2013) 539:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.01.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jiang Y, Guo J, Tang X, Wang X, Hao D, Yang H. The immunological roles of olfactory ensheathing cells in the treatment of spinal cord injury. Front Immunol (2022) 13:881162. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.881162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li Y, Huo S, Fang Y, Zou T, Gu X, Tao Q, et al. ROCK inhibitor Y27632 induced morphological shift and enhanced neurite outgrowth-promoting property of olfactory ensheathing cells via YAP-dependent up-regulation of L1-CAM. Front Cell Neurosci (2018) 12:489. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hartlehnert M, Derksen A, Hagenacker T, Kindermann D, Schafers M, Pawlak M, et al. Schwann cells promote post-traumatic nerve inflammation and neuropathic pain through MHC class II. Sci Rep (2017) 7(1):12518. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12744-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nazareth L, St John J, Murtaza M, Ekberg J. Phagocytosis by peripheral glia: Importance for nervous system functions and implications in injury and disease. Front Cell Dev Biol (2021) 9:660259. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.660259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wright AA, Todorovic M, Murtaza M, St John JA, Ekberg JA. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor and its binding partner HTRA1 are expressed by olfactory ensheathing cells. Mol Cell Neurosci (2020) 102:103450. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2019.103450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vincent AJ, Choi-Lundberg DL, Harris JA, West AK, Chuah MI. Bacteria and PAMPs activate nuclear factor kappaB and gro production in a subset of olfactory ensheathing cells and astrocytes but not in schwann cells. Glia (2007) 55(9):905–16. doi: 10.1002/glia.20512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Carvalho LA, Nobrega AF, Soares ID, Carvalho SL, Allodi S, Baetas-da-Cruz W, et al. The mannose receptor is expressed by olfactory ensheathing cells in the rat olfactory bulb. J Neurosci Res (2013) 91(12):1572–80. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hanayama R, Tanaka M, Miwa K, Shinohara A, Iwamatsu A, Nagata S. Identification of a factor that links apoptotic cells to phagocytes. Nature (2002) 417(6885):182–7. doi: 10.1038/417182a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li Y, Zou T, Xue L, Yin ZQ, Huo S, Xu H. TGF-beta1 enhances phagocytic removal of neuron debris and neuronal survival by olfactory ensheathing cells via integrin/MFG-E8 signaling pathway. Mol Cell Neurosci (2017) 85:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lankford KL, Sasaki M, Radtke C, Kocsis JD. Olfactory ensheathing cells exhibit unique migratory, phagocytic, and myelinating properties in the X-irradiated spinal cord not shared by schwann cells. Glia (2008) 56(15):1664–78. doi: 10.1002/glia.20718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Orr MB, Gensel JC. Spinal cord injury scarring and inflammation: Therapies targeting glial and inflammatory responses. Neurotherapeutics (2018) 15(3):541–53. doi: 10.1007/s13311-018-0631-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yu SS, Li ZY, Xu XZ, Yao F, Luo Y, Liu YC, et al. M1-type microglia can induce astrocytes to deposit chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan after spinal cord injury. Neural Regener Res (2022) 17(5):1072–9. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.324858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ramesh G, MacLean AG, Philipp MT. Cytokines and chemokines at the crossroads of neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and neuropathic pain. Mediators Inflamm (2013) 2013:480739. doi: 10.1155/2013/480739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jin X, Yamashita T. Microglia in central nervous system repair after injury. J Biochem (2016) 159(5):491–6. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvw009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. David S, Kroner A. Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurosci (2011) 12(7):388–99. doi: 10.1038/nrn3053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yan Y, Su J, Zhang Z. The CXCL12/CXCR4/ACKR3 response axis in chronic neurodegenerative disorders of the central nervous system: Therapeutic target and biomarker. Cell Mol Neurobiol (2022) 42(7):2147–56. doi: 10.1007/s10571-021-01115-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vincent AJ, Taylor JM, Choi-Lundberg DL, West AK, Chuah MI. Genetic expression profile of olfactory ensheathing cells is distinct from that of schwann cells and astrocytes. Glia (2005) 51(2):132–47. doi: 10.1002/glia.20195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hisaoka T, Morikawa Y, Kitamura T, Senba E. Expression of a member of tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, TROY, in the developing mouse brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res (2003) 143(1):105–9. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(03)00101-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Su Z, He C. Olfactory ensheathing cells: biology in neural development and regeneration. Prog Neurobiol (2010) 92(4):517–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Inflammation and its role in neuroprotection, axonal regeneration and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol (2008) 209(2):378–88. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cataldi C, Mari NL, Lozovoy MAB, Martins LMM, Reiche EMV, Maes M, et al. Proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles in psoriasis: use as laboratory biomarkers and disease predictors. Inflammation Res (2019) 68(7):557–67. doi: 10.1007/s00011-019-01238-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Daines JM, Schellhardt L, Wood MD. The role of the IL-4 signaling pathway in traumatic nerve injuries. Neurorehabil Neural Repair (2021) 35(5):431–43. doi: 10.1177/15459683211001026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhang L, Zhuang X, Kotitalo P, Keller T, Krzyczmonik A, Haaparanta-Solin M, et al. Intravenous transplantation of olfactory ensheathing cells reduces neuroinflammation after spinal cord injury via interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Theranostics (2021) 11(3):1147–61. doi: 10.7150/thno.52197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Park J, Decker JT, Margul DJ, Smith DR, Cummings BJ, Anderson AJ, et al. Local immunomodulation with anti-inflammatory cytokine-encoding lentivirus enhances functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Mol Ther (2018) 26(7):1756–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Khankan RR, Griffis KG, Haggerty-Skeans JR, Zhong H, Roy RR, Edgerton VR, et al. Olfactory ensheathing cell transplantation after a complete spinal cord transection mediates neuroprotective and immunomodulatory mechanisms to facilitate regeneration. J Neurosci (2016) 36(23):6269–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0085-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Duan D, Rong M, Zeng Y, Teng X, Zhao Z, Liu B, et al. Electrophysiological characterization of NSCs after differentiation induced by OEC conditioned medium. Acta Neurochir (Wien) (2011) 153(10):2085–90. doi: 10.1007/s00701-011-0955-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sethi R, Sethi R, Redmond A, Lavik E. Olfactory ensheathing cells promote differentiation of neural stem cells and robust neurite extension. Stem Cell Rev Rep (2014) 10(6):772–85. doi: 10.1007/s12015-014-9539-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lipson AC, Widenfalk J, Lindqvist E, Ebendal T, Olson L. Neurotrophic properties of olfactory ensheathing glia. Exp Neurol (2003) 180(2):167–71. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4886(02)00058-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cao L, Zhu YL, Su Z, Lv B, Huang Z, Mu L, et al. Olfactory ensheathing cells promote migration of schwann cells by secreted nerve growth factor. Glia (2007) 55(9):897–904. doi: 10.1002/glia.20511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Au E, Richter MW, Vincent AJ, Tetzlaff W, Aebersold R, Sage EH, et al. SPARC From olfactory ensheathing cells stimulates schwann cells to promote neurite outgrowth and enhances spinal cord repair. J Neurosci (2007) 27(27):7208–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0509-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Higginson JR, Barnett SC. The culture of olfactory ensheathing cells (OECs)–a distinct glial cell type. Exp Neurol (2011) 229(1):2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhang X, Klueber KM, Guo Z, Cai J, Lu C, Winstead WI, et al. Induction of neuronal differentiation of adult human olfactory neuroepithelial-derived progenitors. Brain Res (2006), 1073–1074:109–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kearns SM, Laywell ED, Kukekov VK, Steindler DA. Extracellular matrix effects on neurosphere cell motility. Exp Neurol (2003) 182(1):240–4. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00124-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wilkinson AE, Kobelt LJ, Leipzig ND. Immobilized ECM molecules and the effects of concentration and surface type on the control of NSC differentiation. J BioMed Mater Res A (2014) 102(10):3419–28. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wang L, Zhang ZG, Zhang RL, Gregg SR, Hozeska-Solgot A, LeTourneau Y, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) and MMP9 secreted by erythropoietin-activated endothelial cells promote neural progenitor cell migration. J Neurosci (2006) 26(22):5996–6003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5380-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ge L, Zhang C, Xie H, Zhuo Y, Xun C, Chen P, et al. A phosphoproteomics study reveals a defined genetic program for neural lineage commitment of neural stem cells induced by olfactory ensheathing cell-conditioned medium. Pharmacol Res (2021) 172:105797. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Shukla S, Chaturvedi RK, Seth K, Roy NS, Agrawal AK. Enhanced survival and function of neural stem cells-derived dopaminergic neurons under influence of olfactory ensheathing cells in parkinsonian rats. J Neurochem (2009) 109(2):436–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05983.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Srivastava N, Seth K, Khanna VK, Ansari RW, Agrawal AK. Long-term functional restoration by neural progenitor cell transplantation in rat model of cognitive dysfunction: co-transplantation with olfactory ensheathing cells for neurotrophic factor support. Int J Dev Neurosci (2009) 27(1):103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2008.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Qu Q, Sun G, Li W, Yang S, Ye P, Zhao C, et al. Orphan nuclear receptor TLX activates wnt/beta-catenin signalling to stimulate neural stem cell proliferation and self-renewal. Nat Cell Biol (2010) 12(1):31–40. doi: 10.1038/ncb2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Mannino G, Russo C, Maugeri G, Musumeci G, Vicario N, Tibullo D, et al. Adult stem cell niches for tissue homeostasis. J Cell Physiol (2022) 237(1):239–57. doi: 10.1002/jcp.30562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Yue Y, Xue Q, Yang J, Li X, Mi Z, Zhao G, et al. Wnt-activated olfactory ensheathing cells stimulate neural stem cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation. Brain Res (2020) 1735:146726. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.146726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Peterson KM, Aly A, Lerman A, Lerman LO, Rodriguez-Porcel M. Improved survival of mesenchymal stromal cell after hypoxia preconditioning: role of oxidative stress. Life Sci (2011) 88(1-2):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Stubbs SL, Hsiao ST, Peshavariya HM, Lim SY, Dusting GJ, Dilley RJ. Hypoxic preconditioning enhances survival of human adipose-derived stem cells and conditions endothelial cells in vitro . Stem Cells Dev (2012) 21(11):1887–96. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Wang L, Jiang M, Duan D, Zhao Z, Ge L, Teng X, et al. Hyperthermia-conditioned OECs serum-free-conditioned medium induce NSC differentiation into neuron more efficiently by the upregulation of HIF-1 alpha and binding activity. Transplantation (2014) 97(12):1225–32. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Zhuo Y, Wang L, Ge L, Li X, Duan D, Teng X, et al. Hypoxic culture promotes dopaminergic-neuronal differentiation of nasal olfactory mucosa mesenchymal stem cells via upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Cell Transpl (2017) 26(8):1452–61. doi: 10.1177/0963689717720291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Calabrese G, Giuffrida R, Lo Furno D, Parrinello NL, Forte S, Gulino R, et al. Potential effect of CD271 on human mesenchymal stromal cell proliferation and differentiation. Int J Mol Sci (2015) 16(7):15609–24. doi: 10.3390/ijms160715609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Lo Furno D, Mannino G, Cardile V, Parenti R, Giuffrida R. Potential therapeutic applications of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev (2016) 25(21):1615–28. doi: 10.1089/scd.2016.0135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Mannino G, Longo A, Gennuso F, Anfuso CD, Lupo G, Giurdanella G, et al. Effects of high glucose concentration on pericyte-like differentiated human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22(9):4604–19. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lo Furno D, Graziano AC, Caggia S, Perrotta RE, Tarico MS, Giuffrida R, et al. Decrease of apoptosis markers during adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from human adipose tissue. Apoptosis (2013) 18(5):578–88. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0830-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Musumeci G, Mobasheri A, Trovato FM, Szychlinska MA, Graziano AC, Lo Furno D, et al. Biosynthesis of collagen I, II, RUNX2 and lubricin at different time points of chondrogenic differentiation in a 3D in vitro model of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissue. Acta Histochem (2014) 116(8):1407–17. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Russo C, Mannino G, Patane M, Parrinello NL, Pellitteri R, Stanzani S, et al. Ghrelin peptide improves glial conditioned medium effects on neuronal differentiation of human adipose mesenchymal stem cells. Histochem Cell Biol (2021) 156(1):35–46. doi: 10.1007/s00418-021-01980-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Lo Furno D, Pellitteri R, Graziano AC, Giuffrida R, Vancheri C, Gili E, et al. Differentiation of human adipose stem cells into neural phenotype by neuroblastoma- or olfactory ensheathing cells-conditioned medium. J Cell Physiol (2013) 228(11):2109–18. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Lo Furno D, Mannino G, Giuffrida R, Gili E, Vancheri C, Tarico MS, et al. Neural differentiation of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells induced by glial cell conditioned media. J Cell Physiol (2018) 233(10):7091–100. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Lo Furno D, Mannino G, Pellitteri R, Zappala A, Parenti R, Gili E, et al. Conditioned media from glial cells promote a neural-like connexin expression in human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Front Physiol (2018) 9:1742. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Vicario N, Castrogiovanni P, Imbesi R, Giallongo S, Mannino G, Furno DL, et al. GJA1/CX43 high expression levels in the cervical spinal cord of ALS patients correlate to microglia-mediated neuroinflammatory profile. Biomedicines (2022) 10(9):2246–64. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10092246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Vicario N, Parenti R. Connexins signatures of the neurovascular unit and their physio-pathological functions. Int J Mol Sci (2022) 23(17):9510–26. doi: 10.3390/ijms23179510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Vicario N, Turnaturi R, Spitale FM, Torrisi F, Zappala A, Gulino R, et al. Intercellular communication and ion channels in neuropathic pain chronicization. Inflammation Res (2020) 69(9):841–50. doi: 10.1007/s00011-020-01363-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Mannino G, Vicario N, Parenti R, Giuffrida R, Lo Furno D. Connexin expression decreases during adipogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Biol Rep (2020) 47(12):9951–8. doi: 10.1007/s11033-020-05950-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Wang B, Han J, Gao Y, Xiao Z, Chen B, Wang X, et al. The differentiation of rat adipose-derived stem cells into OEC-like cells on collagen scaffolds by co-culturing with OECs. Neurosci Lett (2007) 421(3):191–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Garcia-Alias G, Lopez-Vales R, Fores J, Navarro X, Verdu E. Acute transplantation of olfactory ensheathing cells or schwann cells promotes recovery after spinal cord injury in the rat. J Neurosci Res (2004) 75(5):632–41. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Lopez-Vales R, Fores J, Verdu E, Navarro X. Acute and delayed transplantation of olfactory ensheathing cells promote partial recovery after complete transection of the spinal cord. Neurobiol Dis (2006) 21(1):57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Lopez-Vales R, Garcia-Alias G, Fores J, Navarro X, Verdu E. Increased expression of cyclo-oxygenase 2 and vascular endothelial growth factor in lesioned spinal cord by transplanted olfactory ensheathing cells. J Neurotrauma (2004) 21(8):1031–43. doi: 10.1089/0897715041651105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ramon-Cueto A, Cordero MI, Santos-Benito FF, Avila J. Functional recovery of paraplegic rats and motor axon regeneration in their spinal cords by olfactory ensheathing glia. Neuron (2000) 25(2):425–35. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80905-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Rossignol S, Schwab M, Schwartz M, Fehlings MG. Spinal cord injury: time to move? J Neurosci (2007) 27(44):11782–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3444-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Andrews MR, Stelzner DJ. Evaluation of olfactory ensheathing and schwann cells after implantation into a dorsal injury of adult rat spinal cord. J Neurotrauma (2007) 24(11):1773–92. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Ramer LM, Au E, Richter MW, Liu J, Tetzlaff W, Roskams AJ. Peripheral olfactory ensheathing cells reduce scar and cavity formation and promote regeneration after spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol (2004) 473(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/cne.20049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Gomez RM, Sanchez MY, Portela-Lomba M, Ghotme K, Barreto GE, Sierra J, et al. Cell therapy for spinal cord injury with olfactory ensheathing glia cells (OECs). Glia (2018) 66(7):1267–301. doi: 10.1002/glia.23282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Li Y, Li D, Raisman G. Interaction of olfactory ensheathing cells with astrocytes may be the key to repair of tract injuries in the spinal cord: the ‘pathway hypothesis’. J Neurocytol (2005) 34(3-5):343–51. doi: 10.1007/s11068-005-8361-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Franssen EH, Roet KC, de Bree FM, Verhaagen J. Olfactory ensheathing glia and schwann cells exhibit a distinct interaction behavior with meningeal cells. J Neurosci Res (2009) 87(7):1556–64. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Pastrana E, Moreno-Flores MT, Gurzov EN, Avila J, Wandosell F, Diaz-Nido J. Genes associated with adult axon regeneration promoted by olfactory ensheathing cells: a new role for matrix metalloproteinase 2. J Neurosci (2006) 26(20):5347–59. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1111-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Chuah MI, Choi-Lundberg D, Weston S, Vincent AJ, Chung RS, Vickers JC, et al. Olfactory ensheathing cells promote collateral axonal branching in the injured adult rat spinal cord. Exp Neurol (2004) 185(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Imaizumi T, Lankford KL, Kocsis JD. Transplantation of olfactory ensheathing cells or schwann cells restores rapid and secure conduction across the transected spinal cord. Brain Res (2000) 854(1-2):70–8. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)02285-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Toft A, Scott DT, Barnett SC, Riddell JS. Electrophysiological evidence that olfactory cell transplants improve function after spinal cord injury. Brain (2007) 130(Pt 4):970–84. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Xu X, Liang Z, Lin Y, Rao J, Lin F, Yang Z, et al. Comparing the efficacy and safety of cell transplantation for spinal cord injury: A systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Front Cell Neurosci (2022) 16:860131. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2022.860131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Kawaja MD, Boyd JG, Smithson LJ, Jahed A, Doucette R. Technical strategies to isolate olfactory ensheathing cells for intraspinal implantation. J Neurotrauma (2009) 26(2):155–77. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Murtaza M, Mohanty L, Ekberg JAK, St John JA. Designing olfactory ensheathing cell transplantation therapies: Influence of cell microenvironment. Cell Transpl (2022) 31:9636897221125685. doi: 10.1177/09636897221125685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Miah M, Ferretti P, Choi D. Considering the cellular composition of olfactory ensheathing cell transplants for spinal cord injury repair: A review of the literature. Front Cell Neurosci (2021) 15:781489. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2021.781489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Wang X, Kuang N, Chen Y, Liu G, Wang N, Kong F, et al. Transplantation of olfactory ensheathing cells promotes the therapeutic effect of neural stem cells on spinal cord injury by inhibiting necrioptosis. Aging (Albany NY) (2021) 13(6):9056–70. doi: 10.18632/aging.202758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. He Y, Jiang Y, Dong L, Jiang C, Zhang L, Zhang G, et al. The aOECs facilitate the neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells in the inflammatory microenvironment through up-regulation of bioactive factors and activation of Wnt3/beta-catenin pathway. Mol Neurobiol (2022). doi: 10.1007/s12035-022-03113-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Gu M, Gao Z, Li X, Guo L, Lu T, Li Y, et al. Conditioned medium of olfactory ensheathing cells promotes the functional recovery and axonal regeneration after contusive spinal cord injury. Brain Res (2017) 1654(Pt A):43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Fan H, Chen Z, Tang HB, Shan LQ, Chen ZY, Wang XH, et al. Exosomes derived from olfactory ensheathing cells provided neuroprotection for spinal cord injury by switching the phenotype of macrophages/microglia. Bioeng Transl Med (2022) 7(2):e10287. doi: 10.1002/btm2.10287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Saglam A, Calof AL, Wray S. Novel factor in olfactory ensheathing cell-astrocyte crosstalk: Anti-inflammatory protein alpha-crystallin b. Glia (2021) 69(4):1022–36. doi: 10.1002/glia.23946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Kigerl KA, Gensel JC, Ankeny DP, Alexander JK, Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci (2009) 29(43):13435–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Kroner A, Greenhalgh AD, Zarruk JG, Passos Dos Santos R, Gaestel M, David S. TNF and increased intracellular iron alter macrophage polarization to a detrimental M1 phenotype in the injured spinal cord. Neuron (2014) 83(5):1098–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Basu S, Choudhury IN, Lee JYP, Chacko A, Ekberg JAK, St John JA. Macrophages treated with VEGF and PDGF exert paracrine effects on olfactory ensheathing cell function. Cells (2022) 11(15):2408–28. doi: 10.3390/cells11152408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Reshamwala R, Shah M, St John J, Ekberg J. Survival and integration of transplanted olfactory ensheathing cells are crucial for spinal cord injury repair: Insights from the last 10 years of animal model studies. Cell Transpl (2019) 28(1_suppl):132S–59S. doi: 10.1177/0963689719883823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Lindsay SL, Toft A, Griffin J, MME A, Barnett SC, Riddell JS. Human olfactory mesenchymal stromal cell transplants promote remyelination and earlier improvement in gait co-ordination after spinal cord injury. Glia (2017) 65(4):639–56. doi: 10.1002/glia.23117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]