Summary

Protamines are more arginine-rich and more basic than histones and are responsible for providing a highly compacted shape to the sperm heads in the testis. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation are two events that occur in the late phase of spermatogenesis before the maturation of sperms. In this work, we have studied the effect of phosphorylation of protamine-like cationic peptides using all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. Through thermodynamic analyses, we found that phosphorylation reduces the binding efficiency of such cationic peptides on DNA duplexes. Peptide phosphorylation leads to a less efficient DNA condensation, due to a competition between DNA-peptide and peptide-peptide interactions. We hypothesize that the decrease of peptide bonds between DNA together with peptide self-assembly might allow an optimal re-organization of chromatin and an efficient condensation through subsequent peptide dephosphorylation. Based on the globular and compact conformations of phosphorylated peptides mediated by arginine-phosphoserine H-bonding, we furthermore postulate that phosphorylated protamines could more easily intrude into chromatin and participate to histone release through disruption of histone-histone and histone-DNA binding during spermatogenesis.

Significance

Protamines are essential proteins that aid in the compaction of DNA in sperm cells. Protamines are heavily phosphorylated early after synthesis and before binding to DNA, but they are greatly dephosphorylated during sperm maturation. So, investigating the effects and repercussions of protamine phosphorylation and dephosphorylation on its interaction with DNA is crucial. This study investigates the influence of protamine phosphorylation and dephosphorylation on its binding affinity to DNA and the consequences for DNA compaction.

Introduction

Chromosomal DNA in the cells is packaged inside the minute-sized nucleus with the aid of histones or protamines, the arginine-rich basic proteins (1,2,3). Histones are the major chromatin proteins in somatic cells, and protamines are the major chromatin proteins of sperm cells (1,4,5). Mammalian sperm DNA is the mostly known compact eukaryotic DNA that is packaged around twenty times more tightly than the mitotic chromosomes of somatic cells (6,7,8). It is not possible to achieve such degree of compaction required for sperm cells by histones (7). Thus, the DNA inside the sperm chromatin has to be packed differently. In sperm cells, somatic histones are replaced by highly basic protamines (9,10,11,12,13), aiding the compaction of the paternal genome. Protamines are only half the size of the core histones and replace 85%–90% of the histones packing the sperm DNA in the late haploid phase of spermatogenesis (14,15,16,17). The extremely basic property with high amount of arginine residues and smaller shapes of protamines with high cooperativity should assist in forming a more compact structure of chromatin in comparison to that done by histones (17,18,19). Protamines are extensively phosphorylated shortly after synthesis and before binding to DNA, but they are dephosphorylated significantly during sperm maturation (5,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29). So, it is critical to investigate the effects and consequences of protamine phosphorylation and dephosphorylation on its interaction with DNA.

During the initial mitosis of the mammalian spermatocytes, the haploid spermatids have the DNA packaging similar to that of somatic cells by histones (24,25,26). After mitosis, the chromatin of haploid spermatid undergoes several changes, including acetylation, phosphorylation, and methylation (26,27,28). Each of the core histones consists of a globular core and a flexible tail with lysine residues that interact electrostatically with the negatively charged DNA backbone due to their positive charge (30,31,32). Posttranslational changes, like acetylation, phosphorylation, and methylation, occur on these lysines (33,34), which assist in the histone-protamine transition in the chromatin. The compaction of chromatin by protamine occurs in two steps: first phosphorylation and then dephosphorylation (24,35). In protamine, serine residues are the primary phosphorylation sites (36). Shortly after the synthesis of protamines, the serine and threonine residues in each protamine molecule are phosphorylated, which assists in replacing the core histones and other chromatin proteins (36). More protamine molecules are fitted into the gaps left on the DNA with an increasing degree of phosphorylation (24). Phosphorylation leads to a “protamine contraction” by intramolecular or intermolecular salt bridge formation with neighboring arginine residues (24). Due to their compactness, phosphorylated protamines can occupy areas not open to the unmodified species (24). A dephosphorylation and concomitant “expansion” of bound protamine could then support the rupture of stable contacts of the core histones and lead to their final release (24). So, the question of how protamines displace the somatic histones and build up a different and rather compact DNA-protein structure should be seen in connection with the fact that protamines after synthesis are extensively phosphorylated (20). Phosphorylated protamines displace the histones, and for the compaction of the chromatin to occur, dephosphorylation of protamines (removal of the protamine phosphoryl groups) is required (21,22). Phosphorylation-dephosphorylation is thus in general related to processes that change DNA compaction (25,35).

The present work is aimed to elaborate on the effect of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of protamine on the efficiency of binding to DNA duplex. The work is divided into two parts: 1) single DNA and single protamine simulation to study the protamine binding affinity to DNA and 2) two DNAs and multiple protamines simulation to study the compaction of two DNAs in the influence of the protamines. Due to the computational cost and difficulties in adequate sampling of internally disordered protein, we have used a short cationic peptide in place of the whole length of protamine. The cationic peptide taken is rich in arginine with few serine residues to mimic some important features of protamine. Here, a phosphorylated peptide is one in which all serine residues are phosphorylated, and the nonphosphorylated peptide, used to resemble the dephosphorylated peptide, is the native peptide without any modifications to its residues. Fig. 1 A describes the chemical structures of different residues of the cationic peptide and one of the nucleotides of the DNA. In the first part of the work, we have conducted all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and umbrella sampling (US) simulations of the short cationic peptide bound to double-stranded DNA. Then we analyzed the energetics of binding to assess the effect of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the serine residues of the cationic peptide. In the second part, we have conducted all-atom MD simulations of two DNAs separated at an initial distance of 40 Å and surrounded by multiple peptides. Our objective is to study how strongly DNAs are compacted under the influence of phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated peptides.

Figure 1.

Schematics of the chemical structures of different residues and snapshots of the DNA-peptide complexes used for simulations. (A) Chemical structures of arginine residue, serine residue, phosphorylated serine, and thymide-monophosphate (representative of the nucleotides of DNA). (B) Snapshot of initial configuration of the MAJ_NP complex of DNA and peptide. (C) Snapshot of the initial configuration of the complex with two DNAs and multiple nonphosphorylated peptides for the DNA compaction study. The arginine residue contains 1e+ charge, the serine residue is a chargeless polar residue, the phosphoserine contains 2e− charge, and each nucleotide of the DNA has a phosphate backbone with a charge 1e−. The chemical structures are adapted from the structures available on DrugBank (46).

This article is organized as follows. We begin with methods to describe DNA and protamine model building and details of equilibrium MD and US simulations. The results section will describe the different conformational and energetics analyses of protamine (cationic peptide) binding to DNA. It will be followed by the compaction analysis of two DNAs under the influence of multiple peptides. Finally, the results are summarized with an outlook for the events expected to result in highly compacted sperm cells in the testis.

Materials and methods

System preparation

A 36-basepair-long (d[GCAAAATTTTGC]3) DNA was prepared using the nucleic acid builder tool (37) of Amber18 (38). A cationic peptide ACE-RRRSRRRS-NME was built using the sequence command in the xleap module of AMBER18, where R stands for arginine (ARG) residue and S stands for the serine (SER) residue. The N- and C-terminals are capped with the acetyl (ACE) group (H3CO) and amide (NME) group (H2NCH3 ) to avoid the interaction between termini of the peptide chain. For the first part of the work, the complexes of DNA and the cationic peptide are built using the xleap module such that the peptide is facing the major groove of the DNA. Following the MD simulation results of Mukherjee et al. (39) that the protamine prefers the major groove for its stable binding, we have studied the cationic peptide, which is initially placed at a distance of 20 Å away from the major groove of DNA and, with time, gets adsorbed properly to the major groove. We built two such complexes: 1) MAJ_NP, with a nonphosphorylated peptide in the major groove, and 2) MAJ_PH, with a phosphorylated peptide in the major groove (see Fig. 1 B). The interactions are represented by Amber ff99SB-ILDN force field (40). For the phosphorylated serine (SEP) residues, we used the additional Amber phosaa10 force field (41,42) which is compatible with the Amber ff99SB-ILDN force field. The TIP3P water model (43,44) was used to solvate the complexes, resulting in a 12-Å TIP3P water buffer surrounding the structure in each direction. Systems were neutralized by adding counter ions, and additional monovalent salt was added to mimic the physiologically relevant ionic concentration of 0.15 M. In MAJ_NP, 64 Na+ ions are added to neutralize 70e− charges of DNA phosphates and 6e+ charges of arginine residues of peptide and additional 40 Na+ and 40 Cl− ions are added to make 0.15 M ionic concentration. In MAJ_PH, 68 Na+ ions are added to neutralize 70e− charges of DNA phosphates, 6e+ charges of arginine and 4e− charges of phosphoserine residues of peptide and additional 36 Na+ and 36 Cl− ions are added to make 0.15 M ionic concentration. In this way, the MAJ_NP system contains altogether 45,916 atoms with solvation box of size 54 70 155 Å3 and the MAJ_PH system contains altogether 35,855 atoms with solvation box of size 51 60 155 Å3. The Joung-Cheatham ion parameter set was used to characterize the interaction of ions with water and solute atoms (45). Fig. 1 B shows the snapshot of the initial configuration of the MAJ_NP complex.

For the second part of the work, we built two systems, each having two DNAs surrounded by cationic peptides, one system with nonphosphorylated peptides and the other with phosphorylated peptides. Fig. 1 C shows the snapshot of the initial configuration of one of the complexes with nonphosphorylated peptides. In each simulation, the DNA duplexes are initially placed at 40 Å separation with eleven cationic peptides surrounding each of them. Altogether, there are 22 peptides and two DNA duplexes in a complex system resulting in a ratio of positive charges of ARG in peptides to the negative charges of DNA duplexes (R+/−) of 0.95, i.e., close to the isoelectric point. In the system with nonphosphorylated peptides, 8 Na+ ions are added to neutralize 140e− charges of DNA phosphates, and 132e+ charges of arginine residues of peptides and an additional 200 Na+ and 200 Cl− ions are added to make 0.15 M ionic concentration. In the system with phosphorylated peptides, 96 Na+ ions are added to neutralize 140e− charges of DNA phosphates, and 132e+ charges of arginine and 88e− charges of phosphoserine residues of peptides and an additional 178 Na+ and 178 Cl− ions are added to make 0.15 M ionic concentration. In this way, the system with nonphosphorylated peptides contains altogether 221,718 atoms with a solvation box of size 148 116 155 Å3, and the system with phosphorylated peptides contains altogether 196,264 atoms with a solvation box of size 145 101 155 Å3.

Equilibrium MD

The systems prepared were simulated using AMBER18 (38) software. First, to remove any bad contacts that arise during the system preparation, we performed energy minimization of systems. We used the steepest descent algorithm (for 2500 steps), followed by the conjugate gradient algorithm (next 2500 steps). During energy minimization, all the solute atoms (nucleic acid and peptide atoms) were kept fixed, applying a harmonic restraint using a spring constant of 500 kcal mol−1 Å−2. The restraint applied to the solute atoms was reduced to zero in five stages with 5000 steps of energy minimization in each stage; no restraint was applied anymore during the final 5000 steps of minimization. The energy-minimized systems were then heated from 10 K to 300 K in four steps: 10–50 K, 50–100 K, 100–200 K, and 200–300 K. The DNAs and the peptides were position restrained using a harmonic constant of 20 kcal mol−1 Å−2 during the whole heating process. We used the Langevin thermostat (47,48) with a coupling constant of 0.5 ps to control the temperature. After the heating, the systems were subjected to 2 ns NPT simulation. Berendsen weak coupling method (49,50) with a coupling constant of 0.5 ps was employed to maintain the pressure to 1 atm. Finally, 750-ns-long MD simulations were conducted in the NVT ensemble using the Langevin thermostat (47,48). During simulation, the SHAKE algorithm (51) was adopted to constrain all the bonds involving hydrogen. This allowed use of an integration time step of 2 fs. To account for the long-range electrostatic interaction, we used the particle mesh Ewald method (52) with a cutoff distance of 10 Å. Similar simulation methodologies have been successfully implemented in several of our previous studies involving DNA and DNA-based nanostructures (53,54,55).

Umbrella sampling

All the water molecules and Na+ and Cl− ions are removed in the final structures of complexes MAJ_NP and MAJ_PH, obtained from the all-atom MD simulations. Thus, only the peptide bound with the major groove of the DNA remains in each system. Each system is again solvated with 50 Å of water buffer along the y direction (direction of pulling) and 12 Å of water buffer along the x and z directions. The systems are then neutralized with counter ions, and an additional 98 Na+ and 98 Cl− ions are added to achieve a 0.15 M salt concentration in the system with nonphosphorylated peptide, and an additional 92 Na+ and 92 Cl− ions are added to achieve a 0.15 M salt concentration in the system with phosphorylated peptide. In this way, the system with nonphosphorylated peptide contains altogether 108,010 atoms with a solvation box of size 67 128 150 Å3, and the system with phosphorylated peptide contains altogether 100,171 atoms with a solvation box of size 63 126 150 Å3. These systems are energy minimized and then equilibrated with 10 ns NPT MD simulations using the same procedure described in the previous section. During simulation, the temperature is maintained at 300 K. The potential of mean force (PMF) is calculated using the US method (56) implemented in NAMD (57). During the US runs, the center of mass (COM) of the DNA groove (at which the peptide is bound) is position restrained with a force constant of 10 kcal mol−1 Å−2, and the peptide is pulled perpendicular, from its binding position to a distance 40 Å away from the DNA groove, in steps of 1 Å. Using the collective variables module (58), the reaction coordinate ξ is defined to be the distance between the original position where the peptide binds and the COM of Cα atoms of the peptide (see Fig. 3 A). In each window, an equilibrium MD simulation is performed for 5 ns while the system is restrained by a harmonic spring with force a constant of 5 kcal mol−1 Å−2, allowing the peptide to be pulled perpendicularly. While pulling the peptide, three angular restraints are added to prevent the peptide from sliding along the average long axis of the DNA helix: an angle of 90° between the central Cα atom of the peptide, the COM of the basepair in the same plane, and the COM of the basepair just above it (or just below it), and an angle of 180° between the central Cα of the peptide and two atoms of the basepair in the same plane are fixed to prevent the peptide from rotating around the DNA long axis. All of the angular restraints employ a harmonic potential with a force constant of 0.1 kcal mol−1 Å−2. Histograms of ξ are recorded in each window and are used to calculate the PMF with the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) (59) using Alan Grossfield’s WHAM code (60).

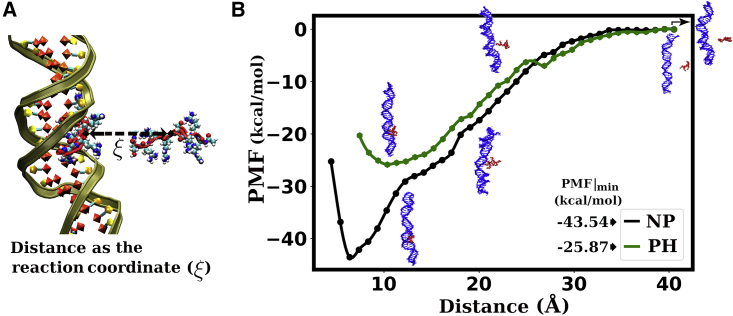

Figure 3.

Pulling of the peptide from its binding position. (A) Schematic of pulling, taking the distance between the initial position of peptide and the instantaneous position of its COM at each window as a reaction coordinate (ξ). (B) PMF profiles for pulling the peptide out of the major groove. Nonphosphorylated peptide shows higher binding preference to DNA compared with the phosphorylated peptide. The error bars are not shown in the plots as the size of the error bars is smaller than the size of the data points.

Results and discussion

Complexes with single DNA and single peptide

Conformational analysis

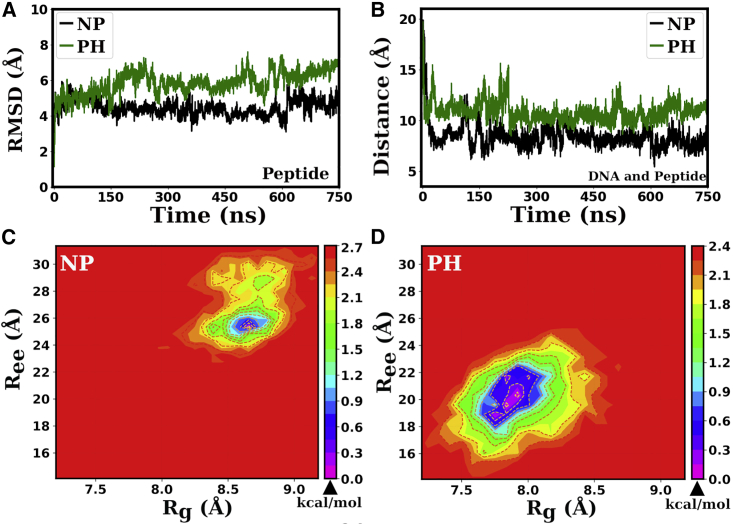

To assess the structural stability of peptide bound to the major groove of the DNA duplex, we have calculated the root mean-square deviation (RMSD) of Cα atoms of the peptide backbone. In Fig. 2 A, we have plotted the RMSDs of the peptide, both for the phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated cases. We find that fluctuations are substantially lower for the nonphosphorylated peptide, with an average value of RMSD of 4.5 0.4 Å. In contrast, the phosphorylated peptide presents larger fluctuations with an average value of 5.9 0.7 Å. Except for the US results, the average values reported in this work are the averages of the last 20 ns of 750-ns-long all-atom MD simulation trajectories in the NVT ensemble.

Figure 2.

RMSD and other conformational study plots for the peptide. (A) RMSD plots for the peptides. (B) Distance between the DNA and the peptide. Subfigures (C) and (D) are the contour maps of free energies as a function of and of the nonphosphorylated peptide and phosphorylated peptide, respectively. Contours are drawn in units of kcal/mol. Note that, in all figures in this work, the green-colored line labeled with PH and the black-colored line labeled with NP represent the plots for the phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated peptides, respectively.

The average distance between the COM of the peptide and the COM of the DNA groove in which the peptide is bound is computed and plotted in Fig. 2 B. The average COM-COM distance is 8.0 0.7 Å for the nonphosphorylated peptide and 10.8 0.9 Å for the phosphorylated peptide, indicating that the nonphosphorylated peptide binds more strongly to the DNA grooves than the phosphorylated one. The RMSD plots for DNA + peptide complexes and the solvent-accessible surface area plots of the peptides also further substantiate this observation (see Figs. S1 A and S1 B and their descriptions given in the Supporting Material (SM)).

The radius of gyration of the phosphorylated peptide is found to be smaller than the nonphosphorylated one (see Fig. S1 C in SM), with an average value of 8.8 0.3 Å for nonphosphorylated peptide and 7.9 0.4 Å for the phosphorylated peptide. We have also measured the end-to-end distance of the peptides. Fig. S1 D in SM shows the end-to-end distances of the peptides. The end-to-end distance analysis showed that the phosphorylated peptide has a lower end-to-end distance in comparison to the nonphosphorylated one. The average value of end-to-end distance observed is 26 2 Å for nonphosphorylated peptide and 20 3 Å for phosphorylated peptide. The energy landscape using contour plots is useful for simultaneously determining the most probable values of two physical quantities. One can use it to deduce information about the peptide’s conformations. The average values of radius of gyration and end-to-end distance reported above are also clearly evident in the contour plots presented in Fig. 2 C and D, corresponding to the minimum free energy defined as , with denoting the population of bin i, and denoting the population of the most populated bin (61). The extended region of lower energies with several strong minima seen in the contour plot for the phosphorylated peptide reflects its larger structural modulation ability. The lower values of the end-to-end distance and the radius of gyration displayed by the phosphorylated peptide indicate a more globular and compact conformation than for the nonphosphorylated peptide.

Energetics analysis

A. Binding free energies using MMGBSA/MMPBSA

We used molecular mechanics generalized Born surface area (MMGBSA) and molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MMPBSA) methods implemented with MMPBSA.py (62) module of AMBER18 to determine which of the peptides, phosphorylated or nonphosphorylated, has a greater binding affinity with the DNA duplex. In the MMGBSA or MMPBSA approach, the free energy for binding of the ligand L (peptide) to the receptor R (DNA) to form the complex C (DNA + peptide) is estimated as follows (63):

| (1) |

where is the free energy of ligand, is the free energy of receptor, and is the free energy of the complex. The terms , , and are differences in vdW energies, electrostatic energies, and the electrostatic solvation energies, respectively, between the complex (C) and the substrates (R + L) upon formation of the complex C (63,64,65). The change in conformational entropy – is generally ignored when just the relative binding free energies of similar ligands are needed because of the high computational expense (63). In this work, the phosphorylated peptide and nonphosphorylated peptide differ in their charge content, which may result in significant difference in their conformational entropy (66,67). Due to computational efficiency and high accuracy, we have computed the entropic contribution (−) term using a two-phase thermodynamic (2PT) model (68,69,70,71,72). The 2PT model computes entropy based on density of states (DoS) function. The DoS function is derived from the Fourier transform of the velocity autocorrelation function, which provides information on the system’s normal mode distribution (68).

We used the last 2000 frames (corresponding to last 20 ns) of the 750-ns simulation to compute the binding free energy for the phosphorylated as well as nonphosphorylated peptides using both MMGBSA and MMPBSA methods, taking the peptide as a ligand and DNA as a receptor. The different energy terms that are involved in yielding the endpoint binding free energy of the peptides are presented in Table 1. The binding free energy is stronger for the nonphosphorylated peptide than the phosphorylated peptide. Using MMGBSA, the binding free energy for the nonphosphorylated peptide is −62 10 kcal/mol, and that for the phosphorylated peptide is −30 9 kcal/mol. Using MMPBSA, the binding free energy for the nonphosphorylated peptide is −57 10 kcal/mol, and for phosphorylated peptide, this value is −22 10 kcal/mol. The binding affinity is greater when the binding free energy is more negative. The energy components presented in Table 1 show that both vdW energy and electrostatic energy terms are more favorable for the nonphosphorylated peptide. The change in entropy is more negative for the nonphosphorylated peptide, implying its strong binding to DNA, reducing its conformational freedom. The less negative for the phosphorylated peptide implies its weaker binding with DNA, allowing it to change the conformation more easily to attain a more spherical shape (due to phosphoserine-arginine interactions within the peptide). The electrostatic solvation energy is higher and more positive (unfavorable) for the nonphosphorylated peptide than the phosphorylated one. That means the nonphosphorylated peptide would lose the largest amount of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) and electrostatic interaction with water compared with the phosphorylated peptide. However, the sum of and components overcomes other components, and the overall binding free energy is negative for both the cases (phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated), with a more negative value for the nonphosphorylated peptide than the phosphorylated one. Thus, both the MMGBSA and MMPBSA analyses imply a higher affinity for binding of the nonphosphorylated peptide with the DNA than that of the phosphorylated peptide.

Table 1.

Different energy terms involved in the binding free energy of the peptides

| Energy Term | MMGBSA | MMPBSA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kcal/mol) | MAJ_NP | MAJ_PH | MAJ_NP | MAJ_PH |

| −54 ± 6 | −34 ± 6 | −54 ± 6 | −34 ± 6 | |

| −5816 ± 102 | −2238 ± 69 | −5816 ± 102 | −2238 ± 69 | |

| −5870 ± 104 | −2272 ± 70 | −5870 ± 104 | −2272 ± 70 | |

| 5802 ± 99 | 2143 ± 65 | 5765 ± 99 | 2214 ± 66 | |

| / + | −8.7 ± 0.6 | −6.4 ± 0.6 | 33 ± 5 | 31 ± 6 |

| a | 5793 ± 99 | 2236 ± 65 | 5799 ± 101 | 2244 ± 66 |

| −77 ± 9 | −36 ± 9 | −72 ± 10 | −28 ± 10 | |

| -b | 15 ± 3 | 6 ± 2 | 15 ± 3 | 6 ± 2 |

| −62 ± 10 | −30 ± 9 | −57 ± 10 | −22 ± 10 |

in MMGBSA and in MMPBSA. For more detail, see Section S3 in SM.

is computed using 2PT model.

To substantiate these results, we also computed the number of H-bonds formed between the peptide and the DNA (see Fig. S2 A in SM) as well as between residues of the peptide (see Fig. S2 B in SM), taking the distance cutoff of 3.5 Å and angle cutoff 120° as suggested by IUPAC (73). The hydrogen bonding between amino acid side chains and DNA bases has been shown to play a significant role (74,75) in protein-DNA interactions: the nonphosphorylated peptide makes an average of 25 5 H-bonds with the DNA, and the phosphorylated one forms, on average, only 14 4 H-bonds. This difference is most likely related to the fact that the phosphorylated peptide forms 5 times more H-bonds between its residues (9 2 versus 2 1 for the nonphosphorylated peptide) and therefore adopts a more globular conformation, reducing its contacts and hence effective interaction with the bases of DNA. Arginine H-bonding with DNA might also be prevented due to electrostatic repulsion between nearest-neighbor phosphoserine and phosphate groups. Indeed the binding of the peptide with DNA is disfavored electrostatically in the case of phosphorylated peptide with respect to the nonphosphorylated one, with an average electrostatic energy of −293 73 kcal/mol versus −577 75 kcal/mol (see Figs. S2 C and S2 D in SM); i.e., a repulsive component of interaction is also involved due to the presence of the SEP residues. This electrostatic effect also participates in the corresponding decrease in the number of H-bonds in the case of phosphorylated peptide, as an H-bond is primarily an electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen atom and a more electronegative atom such as oxygen or nitrogen (73). Taken all together, these conformational and energetics analyses showed that the nonphosphorylated peptide presents a more suitable conformation to enforce a stronger binding to the DNA than the phosphorylated peptide.

B. Potential of mean force

To complement calculations using MMGBSA and MMPBSA methods, we used the US method, to compute the PMF between the DNA and the cationic peptide considered either in its native or phosphorylated forms.

Fig. 3A describes the schematic of pulling. The PMF or dissociation free energy F(ξ) profiles generated from US simulations are shown in Fig. 3 B. At the position (position at which PMF is minimum), the PMF is more negative for the nonphosphorylated peptide than for the phosphorylated one. The free energy differences between the bound and unbound states are −43.54 0.09 kcal/mol and −25.87 0.07 kcal/mol for the nonphosphorylated and phosphorylated peptides, respectively, implying a reduced affinity of binding to DNA under phosphorylation of the peptide residues. Finally, the analysis of the conformation properties of the peptide (end-to-end distance and radius of gyration) in its bound state (first US sampling window) and unbound state (last US sampling window) reveals that the globular structure exhibited by the phosphorylated peptide and induced by phosphoserine-arginine intrapeptide interactions and the more extended conformation of the nonphosphorylated peptides are both enhanced by interactions with the DNA substrate (see Fig. S3 in SM).

DNA-DNA compaction

Different energetics calculations presented in the previous sections suggest that the binding affinity of cationic peptide, mimic of protamine, with DNA is reduced with phosphorylation of its serine residues. Protamine phosphorylation and dephosphorylation are two subsequent events that occur before the compaction of the chromatin in the sperm cells (22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29). In order to assess the importance of phosphorylation on condensation, we simulated the assembly of a pair of DNA in presence of several peptides either in their nonphosphorylated or phosphorylated state. Arginine to DNA phosphate charge ratio is kept close (0.95) from isoelectric point corresponding to the situation encountered in several species (76) in order to ensure a stable DNA packaging. Fig. 4 shows the instantaneous snapshots of the DNA compaction process in several time windows from the 750-ns-long all-atom MD simulations starting from a pair of DNAs initially separated by 40 Å with each DNA surrounded by eleven peptides. Native or nonphosphorylated peptides lead to a tighter self-assembly (see Fig. 4 A) than peptide with phosphorylated serine (see Fig. 4 B). Due to their more globular structure, phosphorylated peptides show a tendency to associate together, forming bulky and loose bridges between DNA. The self-aggregating behavior of phosphorylated peptides is also clearly seen in the inset figures in Fig. 4 where snapshots of the simulations of a single DNA and ten short cationic peptides (upper inset figure for the case of nonphosphorylated peptides and lower one for the case of phosphorylated peptides) are displayed.

Figure 4.

Time evolution of the DNA-DNA compaction under the influence of the cationic peptides. Instantaneous snapshots at 150-ns interval showing the compaction under the influence of (A) nonphosphorylated peptides. (B) phosphorylated peptides. The last snapshot in each panel shows zoomed view of the binding of short cationic peptides (upper: nonphosphorylated peptides, lower: phosphorylated peptides) on single DNA.

Distance between the DNA duplexes and the peptide bridges

To assess the level of compaction of the DNA duplexes, we measured the average distance between the DNA duplexes. Fig. 5 A shows the COM-COM distance of the DNA duplexes (calculated by averaging the COM to COM distance between corresponding basepairs of each DNA) as a function of time. Assembly occurs roughly over 75–100 ns and is faster and sharper in presence of nonphosphorylated peptides than phosphorylated ones. The final equilibrated separation distance (estimated as the average COM-COM distance between corresponding basepairs of the two DNAs and averaged over the last 20 ns) between the two duplexes is of 25.3 0.2 Å in presence of nonphosphorylated peptides, and of 30.1 0.7 Å with phosphorylated peptides.

Figure 5.

Distance between the DNA duplexes and the peptide bridges between them. (A) Average distance between two DNA duplexes. We averaged the COM to COM distance between corresponding basepairs of the two DNA duplexes to compute the average distance. (B) Number of peptide bridges formed between two DNA duplexes. The cationic peptides are expected to form contact bridges between the negative phosphate backbones of two DNAs for the compaction to be effective.

Fig. 5B shows the time evolution of the number of bridges formed by a single peptide between the two DNA duplexes (with a DNA-peptide contact defined when the distance between a peptide atom and a DNA atom is lower than or equal to 3.5 Å). The number of bridges increases sharply within the first 25 ns to reach an average value of 10.3 0.9 in presence of nonphosphorylated peptides. Phosphorylated peptides lead to a more linear increase over the 100 ns to reach an equilibrium average value of 5.9 0.6 bridges. Roughly twice as many bridges are formed by nonphosphorylated peptides, and we hypothesize that this is due to the combined effect of the more extended conformation (induced by a larger charge density) of the native peptides and the tendency of phosphorylated peptides to be self-associated (through phosphoserine-arginine interactions).

Fig. S4A in SM shows the time evolution of the number of H-bonds formed between the DNA duplexes and the peptides, whereas Fig. S4 B displays the time evolution of the number of H-bonds formed between the residues of the peptides themselves (within the same peptide as well as between peptides). As expected, phosphorylated peptides form significantly fewer H-bonds with DNA (258 13) than nonphosphorylated ones (484 17). On the other hand, phosphorylated peptides form many more H-bonds between their residues (378 22) than nonphosphorylated peptides (82 13 on average). The difference comes mostly from H-bond interactions between phosphoserine and arginine ( 300 interactions versus 35 between serine and arginine, data not shown) that contribute mostly to peptide self-aggregation (see interpeptide H-bonds in Figs. S4 C and S4 D of SM) and marginally to the more globular shape (see Figs. S5 A and S5 B) of phosphorylated peptide (due to intra-peptide SEP-ARG interactions). Such a self-aggregating property or cooperativity among peptides competes with bridge formation between the DNA duplexes and peptides, thereby weakening the compaction of the DNA duplexes (see Fig. 4 and insets). Figs. S4 E and S4 F in SM further substantiate this competing effect between peptide-peptide and peptide-DNA interactions through the time evolution of the number of contacts made by the ARG and SER/P residues of peptides with DNA duplexes.

Conclusion

Protamines are the arginine-rich, highly basic proteins responsible for causing compaction of sperm cells in the testis. It has been postulated (22,24,77,78,79) that phosphorylation and dephosphorylation may be necessary to help in organizing protamine locations along DNA during nucleoprotamine formation, whereas a subsequent complete dephosphorylation could favor optimal interactions between protamine and DNA, leading to a complete and tight condensation of chromatin. Such a tight packing might be critical to protect the genetic materials from damage imparted by small reactive oxidative species.

In the present study, we have used all-atom MD simulations to study the effect of phosphorylation on a small protamine-like cationic peptide. We have previously demonstrated (39) that small peptides show a preferential binding into the major groove of DNA with respect to the minor groove of DNA, in agreement with previous RMN studies (80). Here we have shown that peptide phosphorylation weakens its binding affinity to DNA major groove. By comparing the conformation properties (end-to-end distance and radius of gyration) in bound and unbound (bulk) states, we conclude that the extended structure of a single nonphosphorylated peptide is enhanced by its interactions with the DNA substrate (due to numerous favorable arginine-phosphate interactions), whereas DNA enhances a globular shape of a single phosphorylated peptide due to unfavorable phosphoserine-phosphate interactions. Phosphorylated peptides induce a much less efficient compaction of a pair of DNAs than nonphosphorylated ones. This loose compaction results from several interrelated effects, especially a weaker peptide-DNA electrostatic interaction (due to phosphoserine-phosphate repulsive interactions) promoting peptide bridging and a competition between peptide-peptide (via phosphoserine-arginine interactions) and peptide-DNA interactions that lead to “bulky” peptide aggregates contributing also to prevent a close-packing of DNA.

We hypothesize that the lower amount of direct bridges made by phosphorylated peptides between DNAs (due to competition with peptide self-assembly) might increase peptide mobility and re-organization along DNA and lead to a tighter condensation of chromatin under subsequent dephosphorylation. In addition, the smaller and more globular size of phosphorylated peptide induced by H-bonding within peptides found in the present study is in good agreement with the hypothesis of Bode et al. (24) that phosphorylated protamine could minimize their surface area to enter and fit into the gaps present on DNA and participate through subsequent dephosphorylation to the release of histone proteins by disrupting histone-histone and histone-DNA contacts.

Thus, our simulations give a microscopic picture of the DNA compaction process and show the importance of the competition between peptide-DNA and peptide-peptide interaction in assembly. The results predict that the phosphorylation of the protamines reduces their binding affinity to DNA. Also, whereas phosphorylation is required before DNA compaction, it is the dephosphorylation, not phosphorylation, that causes DNA compaction. Phosphorylation helps for intrusion and rearrangement of protamine inside DNAs before replacing histones.

Author contributions

Y.H.J., Y.L., and P.K.M. designed the research. K.B.C. carried out all simulations. K.B.C., Y.H.J., Y.L., and P.K.M. analyzed the data and wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank TUE-CMS, IISc, Bangalore, funded by DST, for providing the computing facilities and SERB, India (IPA/2020/000034) for the financial support. Y.H.J. and Y.L. thank the National Research Foundation of Korea (2019R1A2C2003118 and 2021H1D3A2A01099453) for financial support.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Editor: Lars Nodenskiold

Footnotes

Ned Seeman introduced PKM in the field of DNA nanotechnology almost two decades ago while he was working in the group of Bill Goddard at Caltech. He inspired us to continue to work on DNA nanotubes during his Bangalore visit in later years. His untimely death is a great personal loss as well as a big loss to the whole DNA nanotechnology community. We dedicate this article to his memory.

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2022.09.025.

Contributor Information

Yun Hee Jang, Email: yhjang@dgist.ac.kr.

Yves Lansac, Email: yves.lansac@univ-tours.fr.

Prabal K. Maiti, Email: maiti@iisc.ac.in.

Supporting material

material

References

- 1.Wolffe A.P. Packaging principle: how DNA methylation and histone acetylation control the transcriptional activity of chromatin. J. Exp. Zool. 1998;282:239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan Y., Nikitina T., et al. Skoultchi A.I. Histone H1 depletion in mammals alters global chromatin structure but causes specific changes in gene regulation. Cell. 2005;123:1199–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annunziato A. DNA packaging: nucleosomes and chromatin. Nature Education. 2008;1:26. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausió J. Histone H1 and evolution of sperm nuclear basic proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:31115–31118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rathke C., Baarends W.M., et al. Renkawitz-Pohl R. Chromatin dynamics during spermiogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1839:155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward W.S., Coffey D.S. DNA packaging and organization in mammalian spermatozoa: comparison with somatic cells. Biol. Reprod. 1991;44:569–574. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod44.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller D., Brinkworth M., Iles D. Paternal DNA packaging in spermatozoa: more than the sum of its parts? DNA, histones, protamines and epigenetics. Reproduction. 2010;139:287–301. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukherjee A., de Izarra A., et al. Lansac Y. Protamine-Controlled reversible DNA packaging: a molecular glue. ACS Nano. 2021;15:13094–13104. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c02337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ando T., Yamasaki M., Suzuki K. Springer-Verlag; 1973. Protamines. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliva R. Protamines and male infertility. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2006;12:417–435. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steger K., Balhorn R. Sperm nuclear protamines: a checkpoint to control sperm chromatin quality. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2018;47:273–279. doi: 10.1111/ahe.12361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zinchenko A., Hiramatsu H., et al. Akitaya T. Amino acid sequence of oligopeptide causes marked difference in DNA compaction and transcription. Biophys. J. 2019;116:1836–1844. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ando Y., Steiner M. Sulfhydryl and disulfide groups of platelet membranes. I. Determination of sulfhydryl groups. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1973;311:26–37. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Küçük N. Sperm DNA and detection of DNA fragmentations in sperm. Turk. J. Urol. 2018;44:1–5. doi: 10.5152/tud.2018.49321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louie A.J., Dixon G.H. Enzymatic modifications of the protamines. II. Separation and characterization of phosphorylated species of protamines from trout testis. Can. J. Biochem. 1974;52:536–546. doi: 10.1139/o74-078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ingles C.J., Trevithick J.R., et al. Dixon G.H. Biosynthesis of protamine during spermatogenesis in salmonoid fish. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1966;22:627–634. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(66)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balhorn R. A model for the structure of chromatin in mammalian sperm. J. Cell Biol. 1982;93:298–305. doi: 10.1083/jcb.93.2.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeRouchey J., Hoover B., Rau D.C. A comparison of DNA compaction by arginine and lysine peptides: a physical basis for arginine rich protamines. Biochemistry. 2013;52:3000–3009. doi: 10.1021/bi4001408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willmitzer L., Wagner K.G. The binding of protamines to DNA; role of protamine phosphorylation. Biophys. Struct. Mech. 1980;6:95–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00535747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marushige Y., Marushige K. Phosphorylation of sperm histone during spermiogenesis in mammals. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1978;518:440–449. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(78)90162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingles C.J., Dixon G.H. Phosphorylation of protamine during spermatogenesis in trout testis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1967;58:1011–1018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.3.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Louie A.J., Dixon G.H. Kinetics of enzymatic modification of the protamines and a proposal for their binding to chromatin. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;247:7962–7968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliva R., Dixon G.H. Vertebrate protamine genes and the histone-to-protamine replacement reaction. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1991;40:25–94. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60839-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bode J., Willmitzer L., Opatz K. On the competition between protamines and histones: studies directed towards the understanding of spermiogenesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 1977;72:393–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradbury E.M., Inglis R.J., Matthews H.R. Control of cell division by very lysine rich histone (F1) phosphorylation. Nature. 1974;247:257–261. doi: 10.1038/247257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luense L.J., Wang X., et al. Berger S.L. Comprehensive analysis of histone post-translational modifications in mouse and human male germ cells. Epigenet. Chromatin. 2016;9:24–35. doi: 10.1186/s13072-016-0072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marushige K., Ling V., Dixon G.H. Phosphorylation of chromosomal basic proteins in maturing trout testis. J. Biol. Chem. 1969;244:5953–5958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jergil B., Dixon G.H. Protamine kinase from rainbow trout testis: partial purification and characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:425–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silvestroni L., Frajese G., Fabrizio M. Histones instead of protamines in terminal germ cells of infertile, oligospermic men. Fertil. Steril. 1976;27:1428–1437. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)42260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mariño-Ramírez L., Kann M.G., et al. Landsman D. Histone structure and nucleosome stability. Expert Rev. Proteomics. 2005;2:719–729. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2.5.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saurabh S., Glaser M.A., et al. Maiti P.K. Atomistic simulation of stacked nucleosome core particles: tail bridging, the H4 tail, and effect of hydrophobic forces. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:3048–3060. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b11863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garai A., Saurabh S., et al. Maiti P.K. DNA elasticity from short DNA to nucleosomal DNA. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:11146–11156. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b03006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen S., Casaccia-Bonnefil P. Post-translational modifications of nucleosomal histones in oligodendrocyte lineage cells in development and disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2008;35:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s12031-007-9014-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robison A.D., Sun S., et al. Cremer P.S. Polyarginine interacts more strongly and cooperatively than polylysine with phospholipid bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:9287–9296. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b05604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner T.E., Hartford J.B., et al. Sung M.T. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of histone (V (H5): controlled condensation of avian erythrocyte chromatin. Appendix: phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of histone H5. II. Circular dichroic studies. Biochemistry. 1977;16:286–290. doi: 10.1021/bi00621a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balhorn R., Hud N., et al. Mazrimas J. Technical report, Lawrence Livermore National Lab.; 1995. Importance of Protamine Phosphorylation to Histone Displacement in Spermatids: Can the Disruption of This Process Be Used for Male Contraception. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macke T.J., Case D.A. Modeling unusual nucleic acid structures. ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society. 1997;682:379. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Case D., Cerutti D., et al. Homeyer N. University of California; 2018. AMBER Reference Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukherjee A., Saurabh S., et al. Lansac Y. Protamine binding site on DNA: molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations with full atomistic details. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2021;125:3032–3044. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c09166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindorff-Larsen K., Piana S., et al. Shaw D.E. Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins. 2010;78:1950–1958. doi: 10.1002/prot.22711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Homeyer N., Horn A.H.C., et al. Sticht H. AMBER force-field parameters for phosphorylated amino acids in different protonation states: phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, phosphotyrosine, and phosphohistidine. J. Mol. Model. 2006;12:281–289. doi: 10.1007/s00894-005-0028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinbrecher T., Latzer J., Case D.A. Revised AMBER parameters for bioorganic phosphates. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2012;8:4405–4412. doi: 10.1021/ct300613v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mark P., Nilsson L. Structure and dynamics of the TIP3P, SPC, and SPC/E water models at 298 K. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001;105:9954–9960. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., et al. Klein M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joung I.S., Cheatham T.E. Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:9020–9041. doi: 10.1021/jp8001614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wishart D.S., Knox C., et al. Woolsey J. DrugBank: a comprehensive resource for in silico drug discovery and exploration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D668–D672. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davidchack R.L., Handel R., Tretyakov M.V. Langevin thermostat for rigid body dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;130:234101. doi: 10.1063/1.3149788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Gunsteren W.F., Berendsen H.J.C. A leap-frog algorithm for stochastic dynamics. Mol. Simulat. 1988;1:173–185. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berendsen H.J.C., Postma J.P.M., et al. Haak J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hunenberger P.H. Thermostat algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2005;173:105. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryckaert J.P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H.J. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an Nlog(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chhetri K.B., Dasgupta C., Maiti P.K. Diameter dependent melting and softening of dsDNA under cylindrical confinement. Front. Chem. 2022;10:879746. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.879746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chhetri K.B., Naskar S., Maiti P.K. Probing the microscopic structure and flexibility of oxidized DNA by molecular simulations. Indian J. Phys. 2022;96:2597–2611. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chhetri K.B., Sharma A., et al. Maiti P.K. Nanoscale structure and mechanics of peptide nucleic acids. Nanoscale. 2022;14:6620–6635. doi: 10.1039/d1nr04239d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Torrie G.M., Valleau J.P. Nonphysical sampling distributions in Monte Carlo free-energy estimation: umbrella sampling. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:187–199. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phillips J.C., Braun R., et al. Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fiorin G., Klein M.L., Hénin J. Using collective variables to drive molecular dynamics simulations. Mol. Phys. 2013;111:3345–3362. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar S., Rosenberg J.M., et al. Kollman P.A. The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. J. Comput. Chem. 1992;13:1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grossfield A. 2014. An Implementation of WHAM: The Weighted Histogram Analysis Method, Version 2.0. 9. 18. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen J., Wang J., Zhu W. Molecular mechanism and energy basis of conformational diversity of antibody SPE7 revealed by molecular dynamics simulation and principal component analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:36900–36912. doi: 10.1038/srep36900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller B.R., III, McGee T.D., Jr., et al. Roitberg A.E. MMPBSA.py: an efficient program for end-state free energy calculations. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2012;8:3314–3321. doi: 10.1021/ct300418h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang E., Sun H., et al. Hou T. End-point binding free energy calculation with MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA: strategies and applications in drug design. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:9478–9508. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gilson M.K., Honig B. Calculation of the total electrostatic energy of a macromolecular system: solvation energies, binding energies, and conformational analysis. Proteins. 1988;4:7–18. doi: 10.1002/prot.340040104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang J., Hou T., Xu X. Recent advances in free energy calculations with a combination of molecular mechanics and continuum models. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug Des. 2006;2:287–306. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Korolev N., Berezhnoy N.V., et al. Nordenskiöld L. A universal description for the experimental behavior of salt-(in) dependent oligocation-induced DNA condensation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:7137–7150. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matulis D., Rouzina I., Bloomfield V.A. Thermodynamics of DNA binding and condensation: isothermal titration calorimetry and electrostatic mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;296:1053–1063. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin S.T., Blanco M., Goddard W.A., III The two-phase model for calculating thermodynamic properties of liquids from molecular dynamics: validation for the phase diagram of Lennard-Jones fluids. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;119:11792–11805. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lin S.T., Maiti P.K., Goddard W.A., III Two-phase thermodynamic model for efficient and accurate absolute entropy of water from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:8191–8198. doi: 10.1021/jp103120q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nandy B., Maiti P.K. DNA compaction by a dendrimer. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:217–230. doi: 10.1021/jp106776v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vasumathi V., Maiti P.K. Complexation of siRNA with dendrimer: a molecular modeling approach. Macromolecules. 2010;43:8264–8274. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maiti P.K., Bagchi B. Structure and dynamics of DNA- dendrimer complexation: role of counterions, water, and base pair sequence. Nano Lett. 2006;6:2478–2485. doi: 10.1021/nl061609m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arunan E., Desiraju G.R., et al. Nesbitt D.J. Definition of the hydrogen bond (IUPAC Recommendations 2011) Pure Appl. Chem. 2011;83:1637–1641. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rohs R., Jin X., West S.M., et al. Mann R.S. Origins of specificity in protein-DNA recognition. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:233–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060408-091030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lin M., Guo J.T. New insights into protein–DNA binding specificity from hydrogen bond based comparative study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:11103–11113. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bench G.S., Friz A.M., et al. Balhorn R. DNA and total protamine masses in individual sperm from fertile mammalian subjects. Cytometry. 1996;23:263–271. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(19960401)23:4<263::AID-CYTO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bode J., Lesemann D. The anatomy of cooperative binding between protamines and DNA. Hoppe. Seylers. Z. Physiol. Chem. 1977;358:1505–1512. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1977.358.2.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Green G.R., Balhorn R., et al. Hecht N.B. Synthesis and processing of mammalian protamines and transition proteins. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1994;37:255–263. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080370303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Balhorn R. A Clinician’s guide to sperm DNA and chromatin damage. 2018. Sperm chromatin: an overview; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hud N.V., Milanovich F.P., Balhorn R. Evidence of novel secondary structure in DNA-bound protamine is revealed by Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1994;33:7528–7535. doi: 10.1021/bi00190a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

material