Abstract

Despite tremendous gains over the past decade, methods for characterizing proteins have generally lagged those for nucleic acids, which are characterized by extremely high sensitivity, dynamic range, and throughput. However, the ability to directly characterize proteins at “nucleic acid levels” would address critical biological challenges such as more sensitive medical diagnostics, deeper protein quantification, large-scale measurement and discovery of alternate protein isoforms and modifications, and would open new paths to single-cell proteomics. In response to this need, there has been a push to radically improve protein sequencing technologies by taking inspiration from high-throughput nucleic acid sequencing, with a particular focus on developing practical methods for single-molecule protein sequencing (SMPS). SMPS technologies fall generally into three categories: sequencing-by-degradation (such as e.g., mass spectrometry or fluorosequencing), sequencing-by-transit (e.g., nanopores or quantum tunneling), and sequencing-by-affinity (as in DNA hybridization-based approaches). We describe these diverse approaches, which range from those already experimentally well-supported to the merely speculative, in this nascent field striving to reformulate proteomics.

Keywords: single-molecule protein sequencing (SMPS), proteomics, fluorescence, fluorosequencing, nanopores, DNA nanotechnology, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), electron tunneling

1. Introduction

It’s no exaggeration that next-generation DNA and RNA sequencing (NGS) have revolutionized the study of biology. The ability to sequence DNA and RNA in many different cellular contexts has led to novel discoveries about the underlying causes of genetic diseases (58), organismal development (35), and tracing cell lineages (100), among innumerable others. These methods were invented to sequence nucleic acids at both the bulk and single-molecule level and capitalized on many technical advances ranging in scope from replicating nucleic acids with polymerases in a manner that provides a fluorescent readout, to threading nucleic acids through nanopores and measuring the resulting perturbations to electric current (6, 23, 28). Not only have these new methods increased the throughput and accuracy of nucleic acid sequencing, they have also massively decreased costs. While this substantial growth in nucleic acid sequencing approaches has occurred at a rapid clip, sequencing methods for proteins, especially at the single-molecule level, have largely lagged. As a consequence, knowledge about proteins’ abundances, processing, modifications, localizations, and interactions have not benefited to the same degree as have parallel studies on nucleic acids, motivating a recent, significant push by researchers to develop entirely new modes of protein sequencing.

The primary amino acid sequence of a protein was first obtained by Frederic Sanger in the early 1950s using the combination of difluoronitrobenzene, protein hydrolysis, and paper chromatography (86, 87). This early work was quickly superseded by a method presented by Pehr Edman that used phenylisothiocyanate as a reagent for the stepwise degradation of a protein, accompanied by chromatographic detection of each subsequent detached amino acid derivative (27). Despite several issues, such as the need for a free amino terminus, automated Edman sequencers remained the gold standard of proteomics until the 1990s with the rise of mass spectrometry-based proteomics (92). Early mass spectrometry experiments for proteomics relied heavily on a “bottom-up” approach, which involved digesting proteins into shorter peptides and identifying them using tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (105). Mass spectrometry has remained a standard method for protein identification and quantification up to the present and has seen remarkable increases in its sensitivity and applications in recent years (11). However, limitations in the dynamic range and sensitivity of conventional protein mass spectrometry, particularly when compared to what is achievable by nucleic acid sequencing methods, are serving to stimulate efforts to invent new methods for sequencing proteins (43, 113). Single-molecule protein sequencing has emerged as a viable goal for identifying and quantifying proteins at the ultimate possible (single-molecule) sensitivity. Importantly, both for methods that might rely on matching to a reference sequence database as well as for de novo (i.e., reference-free) methods for protein sequencing, even gaining partial sequence information can often be sufficiently informative to identify many proteins.

Although the field is still nascent, researchers of single-molecule protein sequencing have already made significant achievements and developed a strikingly diverse repertoire of technologies (2, 15, 78, 97). Some incorporate aspects previously developed for proteomics or nucleic acid sequencing, such as Pehr Edman’s sequencing chemistry or nanopores akin to those used for DNA sequencing. Others depart radically from tradition and take advantage of entirely new detection modalities, such as DNA hybridization-based methods. Nonetheless, there are clear parallels with approaches developed for nucleic acid sequencing, and it is helpful to consider the developing proteomics technologies by analogy to four broad categories of DNA sequencing methods: sequencing-by-synthesis, sequencing-by-degradation, sequencing-by-transit, and sequencing-by-affinity (Table 1). It’s particularly worth noting that the dominant technique used for nucleic acids (sequencing-by-synthesis) — the basis for example for Illumina, Sanger, and Pacific Biosciences sequencing methods — has no obvious parallel for proteins. There are as yet still no practical methods, neither enzymatic nor chemical, for copying amino acid polymers molecule-by-molecule. Without protein-dependent protein polymerases, “reverse ribosomes”, or “PCR for proteins”, for example, sequencing-by-synthesis has yet to be explored as a viable single molecule proteomics technology.

Table 1:

Analogies between available nucleic acid sequencing technologies and single molecule protein sequencing methods.

| Sequencing Category | DNA Sequencing Method | Protein Sequencing Method |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing-by-synthesis | Polymerase-based sequencing (Sanger, Illumina, Pacific Biosciences, etc) | None, as no practical chemical or enzymatic copying mechanisms are known for proteins |

| Sequencing-by-degradation | Enzymatic digest sequencing (26, 53) | Fluorosequencing NAAB binding Nanopore mass spectrometry |

| Sequencing-by-transit | Nanopore sequencing | Nanopore sequencing Electron tunneling ClpXP based fingerprinting |

| Sequencing-by-affinity | DNA microarrays Fluorescence in situ hybridization |

DNA nanotechnology (DNA PAINT, FRET X, DNA nanoscope) |

Thus, in this review we’ll explore the approaches that currently appear viable. We will discuss the remaining broad sequencing categories, describing the most recent developments for single-molecule protein sequencing approaches in each category. There are increasingly many proposed approaches for sequencing proteins and peptides at the single-molecule level, and several remain speculative with the only associated data found in patent applications. To focus this review, we’ve opted to restrict discussion just to those methods for which a theoretical justification or proof-of-principle experiment has been pre-printed or published, with an emphasis on recent developments for each technology.

2. Sequencing-by-degradation

In contrast to nucleic acids, proteomics is historically rooted in sequencing-by-degradation approaches, from Frederick Sanger’s degradative methods for identifying the primary sequences of the A and B chains of insulin (86, 87) to the subsequent methods of Edman degradation (27) and tandem mass spectrometry (62). Each of the SMPS methods covered in this section borrow aspects of these older tried-and-true proteomics methods, but now extended to the sensitivity of individual molecules and implemented with an eye to scalability to full proteomes.

2.1. Fluorosequencing

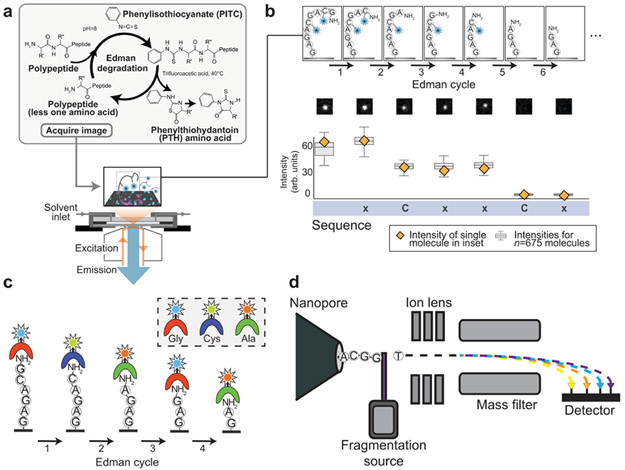

One of the first high-throughput SMPS methods developed, named fluorosequencing (95), combines single molecule microscopy of fluorescent peptides with Pehr Edman’s degradative chemistry, enabling many individual peptide molecules to be monitored in parallel in a sequencing flow cell as their consecutive N-terminal amino acids are removed in a cyclic fashion (Figure 1a). Edman degradation relies on the reactivity of phenylisothiocyanate (PITC) with the α-amino group of a protein or peptide (27). Following this reaction, the first amino acid can be removed from the protein in the presence of a strong acid, leaving behind a protein with a fresh amino terminus, one amino acid shorter in length (Figure 1a, inset). Historically, Edman sequencers were applied only to purified (homogenous) proteins, so the detached amino acid derivatives could then be identified by bulk chromatography. A protein’s primary sequence was ultimately obtained by repeating this chemistry and subsequent chromatography in a cyclical fashion (55, 96). The fluorosequencing method reported by Swaminathan et al. relies instead on proteolytic digestion of proteins into peptides, followed by chemically labeling select amino acid types on the peptides with amino acid-specific fluorophores, and subjecting the labeled peptides to successive rounds of Edman degradation (94). Rather than monitor the released amino acid derivatives, fluorosequencing analyzes the retained parent peptides, thus enabling analysis of protein mixtures, with the sequence of each molecule independently recorded by total internal reflectance fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy across cycles of Edman degradation. The resulting fluorosequence for each peptide molecule indicates the sequence positions at which the fluorescently labeled amino acids were removed (Figure 1b).

Figure 1: Sequencing-by-degradation approaches.

(a) Schematic of fluorosequencing, which uses single molecule microscopy to monitor the reduction in fluorescence from immobilized, fluorescently labeled peptides following consecutive rounds of Edman degradation. Panel a adapted with permission from ref. 94. (b) Example data from ref. 94 showing a peptide with labeled cysteines (blue stars) undergoing fluorosequencing. Top: Peptide sequence after each successive Edman cycle. Middle: Fluorescence emitted from one peptide molecule across Edman cycles. Bottom: Fluorescence quantified across 675 individual molecules with the characteristic stair-step decreases indicating positions of the fluorescently labeled cysteines. (c) A proposed strategy to combine Edman degradation with amino acid detection using NAABs (8,83,99). In one possible implementation, a palette of NAABs might be chosen that have weak but varying affinity for different amino acids, allowing for peptide sequencing based on binding kinetics (83). (d) Schematic representation of the nanopore mass spectrometer under development by Stein and colleagues (13). As single peptides or proteins are fed through the pore a fragmentation source releases each amino acid which will ultimately be identified by an ion detector. It has been speculated that a UV-laser fragmentation source could be used to dissociate amino acids.

Fluorosequencing is an example of a bottom-up proteomics approach, determining partial sequences of individual proteolytic peptides or protein fragments that are subsequently matched to a reference database for protein identification, taking advantage of a known proteome or genome sequence. Instead of requiring the full de novo identification of each amino acid on a protein, it has been shown that only identifying the sequence positions of a few amino acids (“fingerprinting”) can often be sufficient to identify proteins from a reference proteome (73, 95, 107). In practice, fluorosequencing is a hybrid method, identifying the sequence positions of labeled amino acids de novo, then matching those partial sequences to a reference database to identify proteins. A simulation study from this group showed that minimal labeling schemes (comprising 2-4 labeled amino acid types) in combination with various endoprotease choices can in principle be used to identify a large proportion of the proteome (95).

Bioconjugation strategies with high specificity are thus important for many SMPS fingerprinting approaches to identify proteins successfully. Lysine and cysteine have both been covalently labeled with fluorophores at high efficiency and sequenced using fluorosequencing (94), as well detected using FRET X (29) and ClpXP FRET (31), techniques discussed in subsequent sections. Additional labeling strategies have been demonstrated for labeling up to 6 amino acids (KDYWEC) with glutamate and aspartate being indistinguishable (38). In concert with side chain labeling, SMPS may require an N-terminal labeling strategy for reversibly blocking the N-terminus (required for lysine labeling) and a C-terminal labeling strategy, such as to conjugate a linker for slide coupling. In a recent study, Howard et al. applied the reagent 2-pyridinyl carboxaldehyde (PCA), which had previously been shown to specifically form a stable covalent attachment with the N-terminus of proteins, to fluorosequencing (40, 59). They showed that peptides captured onto beads coated in PCA could be labeled with fluorescent dyes, released from the solid-support, and sequenced by fluorosequencing with efficiencies comparable to that observed when the common protecting group fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (fmoc) was used for solution-phase labeling. For C-terminal labeling, Bloom et al. reported a covalent reaction that successfully differentiates between the C-terminus and the side chains of aspartate and glutamate that could be adapted to this approach (7). This approach was optimized for proteomics by Zhang, Floyd et al. and found to be 76% efficient for labeling human cell extract tryptic peptides (110). Further, using this approach peptides were successfully immobilized and fluorosequenced following conjugation of an alkyne linker to the C-terminus of the peptide.

While fluorosequencing has been successfully implemented to determine sparse amino acid–sequence information for individual protein molecules for thousands to millions of molecules in parallel (94), there are several technical hurdles that still must be overcome for widespread adoption of this sequencing approach. The first is the stability of the fluorophores used as labels. The propensity of the harsh Edman reagents to inactivate the fluorophores on the peptides requires a palette of fluorophores that are highly chemically stable (94). The length of the Edman cycle (~1 hr/cycle) has also given rise to some concern especially when considering sequencing peptides of longer length, although it’s worth noting that the approach is not unlike many DNA sequencing approaches in being highly parallel in nature. Borgo et al. proposed an alternative approach of using a designed cysteine protease, called an Edmanase, that would cleave the N-terminal amino acid and would diminish the need for the harsh reagents used for the Edman degradation reaction (9). Regardless, while sequencing of full-length proteins has yet to be shown, quantification of diagnostic peptides in samples of reduced complexity should be possible with this approach at the present.

Finally, in addition to protein identification, another goal of single molecule protein sequencing technologies is to identify post-translational modifications (PTMs) such as phosphorylation and glycosylation. PTM identification using tandem mass spectrometry often requires enrichment for modified peptides from larger amounts of starting sample, and this process can result in biases in the detected PTMs (65, 80). SMPS methods offer a potentially powerful approach to identify and quantify PTMs directly by sequencing. Initial experiments have confirmed the ability of single molecule approaches to localize PTMs: Phosphoserines were fluorosequenced after covalently labeling them with fluorophores (94), and, as discussed further below, electron tunneling (71) and nanopores (56)(79) have each been successfully employed to distinguish phosphorylated proteoforms.

2.2. NAAB binding

Another potential strategy for sequencing peptides by degradation considers N-terminal-specific amino acid binders (NAABs) as an alternative to chemical labeling. NAABs are a class of proteins whose affinity depends on the N-terminal amino acid. NAAB based sequencing therefore relies on the sequential removal of the N-terminal amino acid in order to obtain sequence information (8, 83), alternating removal with NAAB-based identification of the new terminal amino acid (Figure 1c). One looming question for this approach is how to generate a palette of NAABs with high specificity for a majority of the proteinogenic amino acids. One strategy presented by Tullman et al. is to use directed evolution of an enzyme, in this case the substrate recognition protein ClpS, to generate a protein with high specificity for specific N-terminal amino acids (99). By successive rounds of a yeast display screen they were able to obtain multiple variants with increased binding affinity to Phe, Tyr, or Trp. While some background affinity for the WT biases (Phe, Trp, Tyr, Leu) still remains, increasing the affinity for these amino acids over the background amino acids is a promising step for future applications to sequencing methods. To show how a NAAB-based single-molecule protein sequencing platform could work in practice, Rodriques et al. studied whether the weak binding affinity of NAABs could provide sufficient information for protein identification (83). The authors proposed the use of kinetic measurements on a set of NAABs, measuring their association and dissociation rates at the single molecule level, to assign identities to the N-terminal amino acid of an immobilized peptide. In a series of simulations that accounted for various error modes, the authors found that high accuracies of amino acid identification were in principle achievable by such a method. The use of NAABs in practice for protein sequencing has yet to be experimentally shown, but it is an interesting alternative to covalent labeling strategies such as in fluorosequencing and for which chemical destruction of dyes has previously been observed (94).

2.3. Single-molecule mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry has been the gold standard for protein identification for at least the last two decades (1, 108). Improved instrumentation and sampling over the years has increased the sensitivity of mass spectrometers to the point that single cell proteomics via mass spectrometry has become experimentally possible (20, 64, 74). Mass spectrometry utilizes the charging of peptides or proteins — often by electrospray ionization — to detect and identify the ion based on its mass per charge ratio (m/z) (92). Single-ion detection was originally made possible by the Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance instruments but was limited to the characterization of a molecule of interest rather than performing sequencing (48, 50, 84, 91). It has been posited that the placement of a nanopore as the ion source would allow for the sequencing of single proteins using mass spectrometry (13). This approach would rely on the threading of proteins through the pore and subsequent dissociation of individual amino acids at the exit of the pore which would release an amino acid for detection (Figure 1d). The sequential readout of the dissociated amino acids will allow for the sequencing of proteins through passage (66). While a dissociation method for this approach has not yet been shown, it has been proposed that a method such as UV-induced dissociation could perform the task (2, 10). Due to the sequential nature of the nanopore mass spectrometer, throughput could potentially be challenging, and it remains to be seen if the process could be parallelized or indeed what throughput might be feasible.

3. Sequencing-by-transit

Sequencing-by-transit has become an increasingly popular approach for single-molecule nucleic acid sequencing in large part due to the ongoing technological advances in nanopore sequencing. Commercialized by Oxford Nanopore, the nanopore DNA sequencer has proved a powerful platform for long-read single-molecule DNA sequencing while also affording high portability and field applications (46). Not surprisingly, nanopore sequencing has also promisingly been applied to single-molecule protein sequencing, as have other sequencing-by-transit methods such as electron tunneling and a protease-based FRET sequencing approach. Each of these approaches threads proteins or peptides of interest through a sensor, which differs according to the specific approach, e.g., a nanometer sized pore, gold electrodes, or a fluorescently labeled AAA+ protease. This section explores recent developments and applications of each of these different sequencing-by-transit approaches for protein sequencing.

3.1. Nanopore Sequencing

The passage of a biopolymer such as DNA through a nanometer-sized pore as detected by an electric current has rapidly moved from a laboratory proof-of-concept to successful commercialization by Oxford Nanopore Technologies over the past two and a half decades (23, 36). Nanopore sequencing works by separating two compartments containing an ionic buffer with either an organic, inorganic, or hybrid pore (49). A current is established across the cell containing the separated compartments and pore. The passage of a molecule through the pore from the cis to trans compartment results in a blockaded current which corresponds to the volume of the transiting molecule. In the case of DNA sequencing, the current blockade corresponds to the volume of the individual nucleobases and strings of bases can be threaded through the pore to give the DNA sequence in a length independent manner.

The combination of long-read capability and portability of nanopore sequencers is currently energizing the genomics field, and there has been a great push to apply this same technology to protein sequencing (78). However, some clear challenges emerge for applying this technology to protein sequencing. First among these is that proteins and peptides are far more heterogeneous in composition than nucleic acids, with some amino acids such as leucine and isoleucine being largely indistinguishable by charge or occluded volume. Additionally, unlike DNA, proteins do not have a homogenous charge, which complicates capturing and translocating the proteins across a pore. Many of the technical challenges for nanopore based protein sequencing have been well reviewed (22, 42) so this section largely focuses on recent advances in applying this technology to protein sequencing. Some of the main challenges in the field include how to construct pores to support efficient capture and translocation of peptides and proteins, how to unfold proteins prior to their passing through the pore, and how to best read out the amino acid sequence from a transiting protein.

3.1.1. Capture and Translocation

One of the main requirements for nanopore protein sequencing is the capture and translocation of the protein through the pore. In early nanopore sequencing experiments using silicon nitride pores only several dozen translocation events were recorded over the course of several days revealing challenges with the capture and passage of proteins (15, 51). These observed rates of passage would seriously hinder both read depth and increase experimental run time, so extensive effort has been put into developing new methods for capturing and translocating proteins through the pore. Unlike sequencing DNA where electrophoretic forces can be used to draw molecules from the cis to the trans side of a nanopore (93), the non-uniform charge distribution of proteins makes this approach untenable on unmodified proteins (42). One of the initial methods developed for getting around this translocation issue was to attach a highly charged polymer such as DNA or a peptide composed of charged amino acids (e.g., glutamate or arginine) to one or both of the proteins’ termini to support electrophoretically-driven translocation (79, 81, 82). This approach may prove challenging for whole proteomes, as it either requires extensive chemical modification or genetic tagging, stimulating researchers to seek other means of translocating proteins across pores.

One promising alternative approach is the use of electroosmotic flow (EOF) as a capture and translocation mechanism that can overcome the heterogeneous charge distribution of polypeptides. EOF is the flow generated by ions moving in solution under the influence of an electric field, inducing the surrounding water molecules to also move towards the cathode or anode (57). In an early study showing the use of EOF for capturing peptides, the rate of current blockages in an α-hemolysin pore was directly related to a lower buffer pH (67), interpreted as the increased presence of cations in the lower pH buffers providing more ions to drive liquid movement towards the trans anode. In a follow up study using an α-hemolysin pore at pH 2.8, EOF could overcome the electrophoretic effect on a cationic peptide, supporting the viability of this approach for translocation (3). Peptides could be retained and recaptured into the center, or lumen, of the nanopore with this approach, offering a means to repeatedly resample a peptide with the nanopore. More recently it was demonstrated that it is possible to engineer a nanopore to generate an EOF and capture folded proteins (45). Rather than relying on the flow generated by a low pH buffer, this study used site-specific mutagenesis to incorporate positively charged residues inside the pore to help to generate an EOF at pH 7.5. Ren and colleagues also developed field-effect transistors (FET) coupled with nanopores where the gate medium for the FET controls the flow of ions (76), thus adding selectivity to the capture and translocation of proteins. In a follow up study, adding protein specific (thrombin-binding) aptamers to the shell of the nanopipette used for the FET further increased selectivity in sampling. While EOF has been shown to translocate peptides and folded proteins through pores, it has not yet been determined whether full length proteins can be linearized in the nanopore lumen using only these forces. It is possible that in order to overcome the entropic barriers of protein unfolding, a detergent or additional enzyme, such as an unfoldase, may be necessary.

Enzyme driven unfolding and translocation has thus been seen as a promising approach for overcoming several of these technical hurdles to nanopore use. For DNA sequencing, the use of a modified version of the polymerase phi29 as a motor to ratchet DNA strands through a nanopore in a controlled manner greatly improved base calling accuracy (19, 63). A deliberate “slowing down” of pore traversal is also likely to benefit protein sequencing, and the use of exoproteases as molecular ratchets has been viewed as a feasible strategy for doing so. In one of the earliest examples of nanopore sequencing with proteins, Nivala et al. used a variant of the ATP-dependent chaperone ClpX that was placed on the trans side of an α-hemolysin pore to unfold and thread proteins containing an ssrA tag across the pore (68). In a follow-up study, the Akeson group showed that a nanopore used in conjunction with ClpXP (which contains ClpX as well as the proteolytic ClpP assembly) could discriminate variants of a titin fragment contained in a modified protein (69). It should be noted that the motor enzymes in these studies were placed on the trans side of the pores, so the step sizes taken by proteins transiting through the pores were dictated by the activities and structures of the motor enzymes. This use of motor enzymes as molecular ratchets speaks to the promise of exploring analogs of DNA sequencing approaches for next-generation proteomics platforms.

3.1.2. Amino Acid Identification Using Nanopores

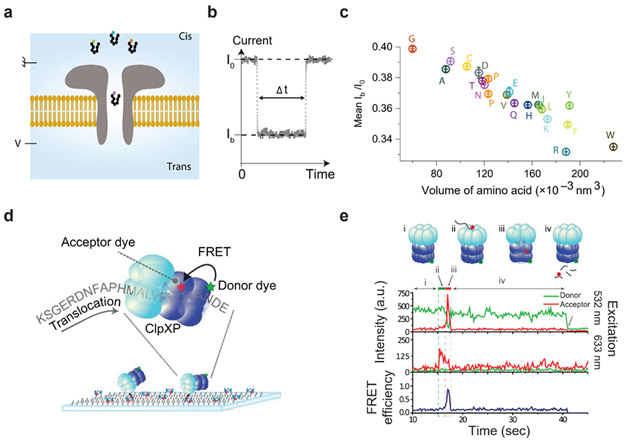

Great strides have been made in identifying amino acids using nanopore sequencing, with a particularly clear example of the ability of nanopores to discriminate the current blockades of the proteinogenic amino acids described by Ouldali and colleagues (72). Using a polyarginine peptide with a variable C-terminal amino acid, they showed that most of the 20 canonical amino acids could be differentiated based on residual current and blockage volume in a wild-type aerolysin pore (Figure 2a-c). These results in conjunction with the differential estimates of peptide length recorded in a previous study (75) support the promise of nanopores for discriminating peptide sequences to a high degree. Thus far, nanopore protein sequencing experiments have predominantly used wild-type alpha-hemolysin and aerolysin nanopores, but there has also been a push to engineer biological pores with improved characteristics. Cao et al. showed that the aerolysin pore sensitivity can be increased by rationally engineering its charge and diameter (16). In a more radical application of rational engineering to nanopore design, Zhang et al. constructed a proteasome-coupled nanopore that is capable of translocating unfolded proteins when the proteasome component was inactive (111). As an alternative to this “thread-and-read” approach, when the proteasome component was active, this pore could digest proteins into 6-10 amino acid long peptides which might then — at least, in principle — be identified in the nanopore in a “chop-and-drop” strategy. A somewhat related strategy for identifying individual amino acids was shown by Wei et al. (103). By using the aromatic reagents 2,3-naphthalenedicarboxaldehyde (NDA) and 2-naphthylisothiocyanate (NITC) as coupling reagents to the N-termini of free amino acids they showed that these additional tags boosted the distinguishability of the 9 amino acids they tested as they translocated across an α-hemolysin pore. Since free amino acids are required for identification with this approach, actual application would presumably require a protease or chemical reagent that cleaves amino acids processively so they could then be consecutively identified; such a combined approach has not yet been reduced to practice.

Figure 2: Sequencing-by-transit approaches.

(a) Schematic of a nanopore peptide sequencing experiment. An external voltage (V) is applied on the trans side of the pore, and a voltage ground is applied on the cis side, represented by the symbol on the top left side of the panel. (b) Depiction of a typical current blockade. I0 symbolizes the open pore ionic current, and Ib symbolizes the blockaded current. (c) Mean relative residual current (Ib/I0) and its standard deviation from the measurement of XR7 (X being any amino acid) peptides. (d) Schematic of the ClpX single-molecule protein sequencing approach. Donor dye-labeled ClpXP is immobilized on a slide surface, and an ssrA-conjugated peptide labeled with an acceptor dye is threaded through the complex. (e) A fluorescence time trace that captures the different moments of translocation. (i) The donor signal from Cy3-labeled ClpXP excited at 532 nm (top green trace). (ii) Appearance of acceptor signal due to acceptor-directed excitation at 633 nm (middle red trace) indicates the binding of the acceptor-labeled peptide to ClpXP. (iii) The fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) signal (bottom blue trace) reports on the presence of the peptide in ClpP. (iv) Loss of fluorescent and FRET signals indicates the release of the peptide. Panels a-c adapted with permission from Reference (72). Panels d and e adapted with permission from Reference (31).

In a strategy aimed at a more direct sequence readout, Brinkerhoff and colleagues attached a peptide to a DNA strand and pulled the peptide-DNA conjugate through an MspA nanopore via the action of a helicase acting on the DNA segment (115). The result was clear step-wise ion current traces such as are more typically seen in DNA nanopore sequencing experiments. Importantly, the authors demonstrated that peptides differing at individual amino acids gave rise to distinguishable step traces, supporting the notion that direct amino acid sequencing might be possible with such an approach, and that they could repeatedly resample the peptide, which should help in achieving low sequencing error rates. Such approaches and others (116) offer intriguing potential routes forward for fingerprinting and identifying proteins that would leverage nanopores’ abilities to discriminate amino acid types and potentially even modifications (44, 79).

In fact, protein fingerprinting can be achieved in different ways, and some current nanopore implementations rely on chemical labeling of specific residues such as lysine and cysteine. Simulations by Ohayon et al. showed that three labels could allow for discrimination of up to 97% of the human proteome by monitoring fluorescence intensity and protein translocation through the nanopore (70). Promisingly, multiple groups have demonstrated the feasibility of identifying labeled amino acids with a nanopore. Wang et al. showed that fluorescence microscopy and TiO2 nanopore detection could discriminate identical polypeptides with different fluorescent labels (102). This approach could in principle allow for the quantitation and localization of labels on a polypeptide. In another example of fingerprinting with a nanopore, Restrepo-Pérez et al. used a fragaceatoxin C nanopore to identify six different labels that, when conjugated to cysteine at various positions, could be resolved site-specifically (77). Fingerprinting proteins using nanopores may serve as a springboard for nanopore sequencing while full de novo sequencing strategies continue to develop.

Work done with nanopores has also shown the potential of PTM identification without any enrichment or labeling step. In one such study, Restrepo-Pérez et al. showed that on a dipolar peptide, phosphorylated and glycosylated modiforms could be distinguished from the unmodified peptide (79). Importantly, they observed that modified peptides tended to have an extended dwell time within the pore which could result in better characterization of the modified peptide. In a later study Li et al. used an engineered aerolysin nanopore to identify adjacent phosphorylation sites on the medically relevant Tau peptide (56). Notably, three variants of the phosphorylated Tau peptide were added to the same nanopore chamber sequentially and were ably distinguished indicating that even in samples with multiple proteoforms, discrimination will still be possible (at least in low complexity samples).

Single-molecule protein sequencing using nanopores is one of the most mature of the technologies covered in this review, but there are still challenges to its widespread adoption, among them the need for better computational strategies for discriminating amino acids. In one interesting approach, Rodriguez-Larrea trained a neural network to identify single amino acid differences on a point mutant of thioredoxin (81). This study focused on a limited set of 9 amino acids, but future studies will need to focus on discriminating at least the 20 proteinogenic amino acids. The promise of label-free identification of amino acids and their modified variants are very promising for the future of proteomics. As well as sequencing, nanopores have also begun to be used to profile folded proteins and obtain signatures based on the different orientations adopted by the protein in the pore (39, 89, 109). It can be imagined that the nanopore sensor will turn into a multitool for single-molecule protein analysis.

3.2. Electron tunneling

Where nanopore based sequencing relies on the electrical properties of biomolecules in the longitudinal direction (ie. down the strand of the polymer), electron, or quantum, tunneling surveys the electrical properties in the transverse direction (25). In the case of DNA this would mean the probing of individual bases perpendicular to the DNA strand (114), and in the case of peptides and proteins this would mean probing amino acid side chains perpendicular to the peptide bond. Measurements for electron tunneling involve measuring the electron tunneling current of a subunit sandwiched between two electrodes (typically gold electrodes) with a set gap distance (Figure 2d). For proteins and peptides, it is hoped that a distinct tunneling signature is observed for each amino acid as the polypeptide passes through a pore containing the electrodes.

Two pioneering studies have shown the feasibility of applying electron tunneling to single-molecule protein sequencing. The first by Zhao et al. used a 2 nm electrode gap to distinguish modified forms of the same amino acid, enantiomers of asparagine, and leucine from isoleucine to show the effectiveness of the approach (112). Using a support vector machine (SVM) classifier that was trained on the electronic signature of each amino acid sampled, this strategy for electron tunneling performed well enough to detect distinct signals between the enantiomers L- and D-asparagine. This study sampled only monomeric amino acids so when considering how to sequence proteins they proposed a microreactor with an exo-peptidase that can release a terminal amino acid that can then be sampled. A following study by Ohshiro et al. showed that electron tunneling could be used to discriminate between 12 amino acids including the phosphorylated form of tyrosine from the unphosphorylated variant (71). This required the use of two sizes of nanogaps — the distance between the sandwiching electrodes — of 0.55 and 0.7 nm. Of the 12 amino acids sampled, there was a clear discriminatory power for about half of the amino acids with the two nanogap sizes when both dwelling time and conductance were used to form an electronic signature (Figure 2e). In addition, when sampling a mixed solution of tyrosine and phosphotyrosine at different ratios it was possible to distinguish between the two based on their individual signals. Importantly, by using two peptides that had matching sequences except for a single residue they were able to show that peptides can be measured using this approach — all the previous measurements were with monomeric amino acids — and that single-residue differences can result in distinguishable electronic signatures. It is worth noting that distinguishable residues such as tyrosine and phenylalanine could be localized on the peptide with site specificity offering a clear protein fingerprinting option.

3.3. ClpXP based FRET

A unique protein fingerprinting method, first introduced in a simulation study by Yao et al., relies on the enzyme ClpX to gather sequential information on labeled amino acids (107). ClpX is a AAA+ protease that functions as a molecular motor that processively unfolds and degrades proteins (4, 61). By tethering ClpX labeled with a donor dye to a slide surface which can then unfold and translocate a protein labeled on cysteines and lysines with acceptor dyes, a linear fingerprint of these residues can be observed by fluorescence (aka Förster) resonance energy transfer (FRET) (31). (Figure 2f-g). Van Ginkel and colleagues demonstrated that peptides either labeled with one or two fluorophores and containing an N-terminal ssrA tag for ClpP recognition could be differentiated based on FRET signals. They further showed that differences in the wild type and mutant variant of the protein Titin could be distinguished based on their FRET signal. The authors noted that Titin’s tertiary structure was disrupted by the labeling process, suggesting that labels might potentially be applied even to sites buried in the native 3D structure, and moreover that the labels would sufficiently disrupt the structure for subsequent CplX fingerprinting. It is worth noting that the requirement of an ssrA tag for translocation through ClpX makes scaling this method to the full proteome difficult in practice.

4. Sequencing-by-affinity

Affinity-based strategies have been used for decades to identify and quantify DNA in mixtures with methods such as DNA microarray technologies (34, 37, 101). DNA microarrays use the hybridization of sample DNA to thousands of DNA strands coupled onto a slide surface to identify the sample sequence. The corresponding fluorescent signals give a rough estimate of gene expression in the cell (52). For proteins, affinity-based identification is extremely common thanks to the widespread use of antibodies as tools for protein assays and imaging (5, 12, 30, 47, 98, 104, 106). Antibody-based protein profiling assays such as for the Human Protein Atlas project and other affinity based methods such as the aptamer-based approach used by Somalogic are being successfully applied to complex samples and at large-scale, but as they profile proteins rather than sequence them, they will be excluded from this section (32, 60, 85). The technologies covered in this section largely rely on the hybridization of DNA to DNA strands covalently attached to a peptide or protein in order to read out amino acid composition.

4.1. DNA nanotechnology

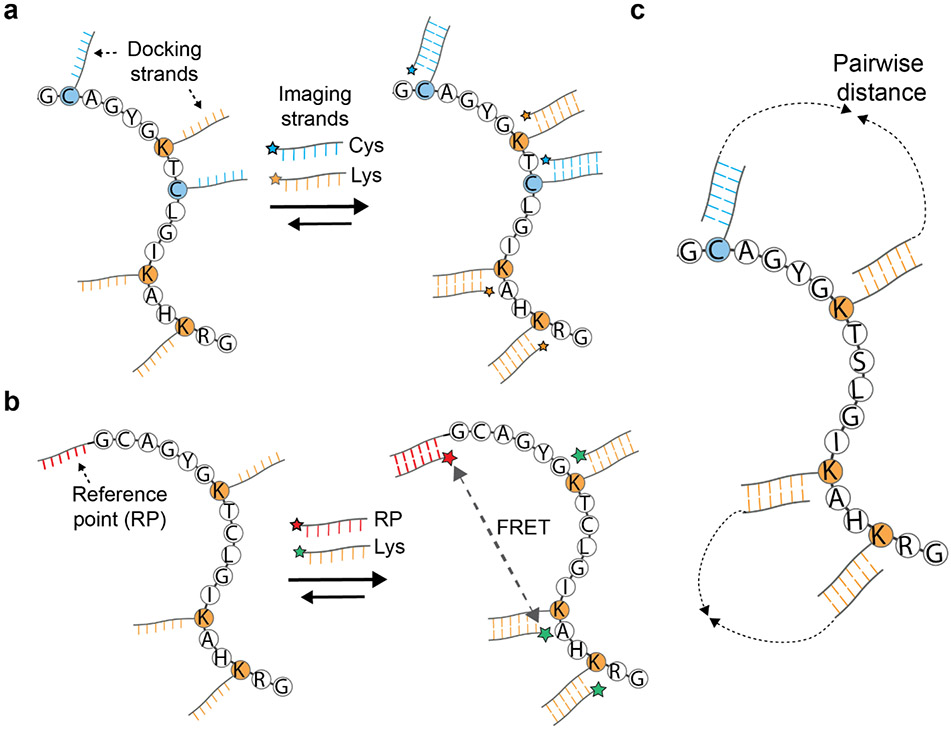

DNA nanotechnology has been applied for use in fields ranging from drug delivery to disease diagnostics (17, 18, 21, 41), and in the field of imaging to perform nanoscale topography. Super-resolution microscopy of DNA probes has been achieved by accumulating the centroids of observed fluorescence events from the DNA probes (DNA-PAINT) (90). DNA-PAINT relies on the programmable nature of DNA strand hybridization between docking and imaging strands to gain fine spatial resolution compositional information about a molecule of interest (Figure 3a). This spatial resolution can reach below 5 nm currently. It has been proposed that if individual protein chains could be linearized, the labeling of lysines or cysteines (or both) with docking strands and imaging with imager strands could be used for obtaining a protein fingerprint (24). By one estimate, localizing lysines in proteins within 5 nm imaging resolution might allow more than half of the proteome to be uniquely identified, extending to three-quarters if lysines and cysteines were labeled with unique strands and similarly localized (2). In practice it has yet to be shown how linearization will be achieved for this approach, although approaches akin to optical tweezers might possibly be applied (14).

Figure 3: Sequencing-by-affinity approaches.

(a) Depiction of the DNA-PAINT method and its proposed application to protein fingerprinting (24)(90). Proteins are first covalently labeled with docking DNA strands that contain sequences specific for the amino acids being labeled. Imaging DNA strands conjugated with fluorophores hybridize with docking strands for specific amino acids to provide compositional information about a peptide or protein. In principle, by linearizing a protein and visualizing by super-resolution microscopy, relative positional information for the labeled amino acids can also be obtained. (b) Depiction of the FRET X method (29) and an application to protein fingerprinting (54). Proteins are labeled with docking DNA strands in addition to an acceptor dye on the protein terminus, the latter serving as a fixed reference point. Imaging strands containing a donor dye are then hybridized onto the docking strands. The resulting FRET signals are proportional to distance, providing a distance histogram characteristic of the protein’s sequence and fold. (c) Depiction of the proposed DNA nanoscope protein fingerprinting method (33, 88). DNA strands are amplified in such a way as to record distances between pairs of oligonucleotide-conjugated amino acids, with the resulting histogram of pairwise distances giving information about the order and position of the labeled amino acids.

Another strategy that uses DNA probes to measure amino acid composition and spatial organization is termed FRET using DNA eXchange (FRET X). Rather than directly localizing DNA imaging strands as in DNA-PAINT, FRET X measures dye-dye distances via FRET as a readout (29). In FRET X, a single reference DNA strand is attached to either the C or N-terminus of the protein, and multiple docking strands are conjugated onto accessible reactive amino acids such as lysines or cysteines. One imaging strand containing an acceptor fluorophore is hybridized to the reference point DNA. An imaging strand containing a donor fluorophore can then be hybridized to one of the amino acid conjugated DNA strands, and the distance between the reference point (C or N-terminus) and the labeled amino acid position measured based on the acceptor-donor fluorophore FRET efficiency (Figure 3b). By sampling across multiple such amino acid-conjugated strands, a histogram of FRET distances can be collected and used as a fingerprint of the peptide or protein of interest. de Lannoy et al. determined by simulation that with cysteine, lysine, and arginine labels, FRET X could in principle be used to identify proteins with 95% accuracy in a sample of about 300 human proteins (54). This study also experimentally demonstrated the capability of FRET X to measure the distance of an amino acid (cysteine in this case) at variable distances along a peptide chain from the N-terminus of the peptide. Importantly, unlike DNA-PAINT, FRET X is applicable to folded proteins, removing the need to linearize proteins prior to fingerprinting.

Finally, DNA nanoscopy represents a DNA nanotechnology approach that relies on DNA amplification rather than docking and imager strands. The DNA nanoscope uses a process termed auto-cycling proximity recording to essentially build a molecular ruler out of DNA that can be used to measure the distance between conjugated molecules such as amino acids (33, 88) (Figure 3c). Proof-of-principle experiments have shown that this approach can work to reconstruct DNA nanostructure organization, but this approach has yet to be demonstrated on a protein sample.

5. Outlook

The recent ongoing development in single-molecule protein sequencing technologies in many ways parallels advances made for DNA and RNA sequencing. In addition to the technologies covered in this review, there have been numerous additional proposals and patent applications for more speculative technologies on which there is as yet no published data or information. In fact, there seems to be a perfect storm of factors propelling the SMPS field forward: a focused push by the technology community to develop new proteomics approaches, the strong progress made to date helping to spur new entrants to the field, the potential applicability of many interesting and powerful strategies from nucleic acid sequencing, and a drive to commercialize SMPS technologies. We expect that the coming years will witness even more diverse protein sequencing technologies, creating a rich ecosystem of complementary SPMS technologies.

In light of this notion, it’s worth noting that in many instances the goal of protein sequencing will often not be to obtain the sequences themselves, but rather to identify and quantify the proteins. In fact, we can expect the technologies under development to have very different strengths for sequencing vs. identification vs. quantification. In the world of nucleic acid sequencing, short-read, high-throughput approaches (as is common for e.g. Illumina sequencing) stand in contrast to long-read, moderate-throughput approaches (e.g. as for Pacific Biosciences or Oxford nanopore sequencing), and specialized applications leverage these strengths, as for RNA-sequencing benefitting from the deep read counts of short-read sequencing versus metagenomics or genome assembly benefitting from longer reads. We similarly expect short-read, highly parallelized SMPS technologies (e.g. fluorosequencing) to offer deep quantification, while long-read, moderate-throughput SMPS approaches (e.g. nanopores) promise characterization of long proteoforms or combinatorial mapping of PTMs. SMPS technologies will almost certainly be differentiated along other axes as well, including their abilities to perform absolute versus relative quantification, their abilities to identify novel modifications versus the detection and cataloging of known ones, their ability to quantify distinct proteoforms, and — a major factor that has not received the attention it deserves — the complexity of their sample preparations and its applicability to low abundance samples.

Nonetheless, the field of SMPS is still young, and most of the technologies with published proof-of-principle results have yet to demonstrate substantial results on complex protein samples, much less the most challenging proteomics samples, such as single-cell analysis of proteins or high-throughput PTM discovery. We are very excited to see these “bleeding-edge” single-molecule protein sequencing approaches make the leap from technology development to broader applications, fostered by a growing community effort to push back the boundaries of the field.

6. Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Jagannath Swaminathan and Eric Anslyn for helpful discussion, as well as research support from the Welch Foundation (F-1515), Erisyon, Inc., and the National Institutes of Health (R35 GM122480, R01 HD085901, R21 HD103588). E.M.M. is a co-founder and shareholder of Erisyon, Inc., and serves on the scientific advisory board. B.M.F. and E.M.M. are co-inventors on granted patents or pending patent applications related to single molecule protein sequencing.

Literature Cited

- 1.Aebersold R, Mann M. 2003. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature. 422(6928):198–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfaro JA, Bohländer P, Dai M, Filius M, Howard CJ, et al. 2021. The emerging landscape of single-molecule protein sequencing technologies. Nat. Methods 18(6):604–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asandei A, Schiopu I, Chinappi M, Seo CH, Park Y, Luchian T. 2016. Electroosmotic Trap Against the Electrophoretic Force Near a Protein Nanopore Reveals Peptide Dynamics During Capture and Translocation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8(20):13166–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aubin-Tam M-E, Olivares AO, Sauer RT, Baker TA, Lang MJ. 2011. Single-Molecule Protein Unfolding and Translocation by an ATP-Fueled Proteolytic Machine. Cell. 145(2):257–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avrameas S 1969. Coupling of enzymes to proteins with glutaraldehyde. Use of the conjugates for the detection of antigens and antibodies. Immunochemistry. 6(1):43–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow HP, Smith GP, Milton J, et al. 2008. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 456(7218):53–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloom S, Liu C, Kölmel DK, Qiao JX, Zhang Y, et al. 2018. Decarboxylative alkylation for site-selective bioconjugation of native proteins via oxidation potentials. Nat. Chem 10(2):205–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borgo B, Havranek JJ. 2014. Motif-directed redesign of enzyme specificity. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc 23(3):312–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borgo B, Havranek JJ. 2015. Computer-aided design of a catalyst for Edman degradation utilizing substrate-assisted catalysis. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc 24(4):571–79 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodbelt JS. 2014. Photodissociation mass spectrometry: new tools for characterization of biological molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev 43(8):2757–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunner A-D, Thielert M, Vasilopoulou CG, Ammar C, Coscia F, et al. 2021. Ultra-high sensitivity mass spectrometry quantifies single-cell proteome changes upon perturbation. bioRxiv. 2020.12.22.423933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnette WN. 1981. “Western Blotting”: Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels to unmodified nitrocellulose and radiographic detection with antibody and radioiodinated protein A. Anal. Biochem 112(2):195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bush J, Maulbetsch W, Lepoitevin M, Wiener B, Mihovilovic Skanata M, et al. 2017. The nanopore mass spectrometer. Rev. Sci. Instrum 88(11):113307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bustamante C, Alexander L, Maciuba K, Kaiser CM. 2020. Single-Molecule Studies of Protein Folding with Optical Tweezers. Annu. Rev. Biochem 89(1):443–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callahan N, Tullman J, Kelman Z, Marino J. 2020. Strategies for Development of a Next-Generation Protein Sequencing Platform. Trends Biochem. Sci 45(1):76–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao C, Cirauqui N, Marcaida MJ, Buglakova E, Duperrex A, et al. 2019. Single-molecule sensing of peptides and nucleic acids by engineered aerolysin nanopores. Nat. Commun 10(1):4918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandrasekaran AR, Punnoose JA, Zhou L, Dey P, Dey BK, Halvorsen K. 2019. DNA nanotechnology approaches for microRNA detection and diagnosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(20):10489–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen T, Ren L, Liu X, Zhou M, Li L, et al. 2018. DNA Nanotechnology for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci 19(6):1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cherf GM, Lieberman KR, Rashid H, Lam CE, Karplus K, Akeson M. 2012. Automated forward and reverse ratcheting of DNA in a nanopore at 5-Å precision. Nat. Biotechnol 30(4):344–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung TK, Lee C-Y, Bayer FP, McCoy A, Kuster B, Rose CM. 2021. Defining the carrier proteome limit for single-cell proteomics. Nat. Methods 18(1):76–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chi Q, Yang Z, Xu K, Wang C, Liang H. 2020. DNA Nanostructure as an Efficient Drug Delivery Platform for Immunotherapy. Front. Pharmacol 10: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chinappi M, Cecconi F. 2018. Protein sequencing via nanopore based devices: a nanofluidics perspective. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 30(20):204002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarke J, Wu H-C, Jayasinghe L, Patel A, Reid S, Bayley H. 2009. Continuous base identification for single-molecule nanopore DNA sequencing. Nat. Nanotechnol 4(4):265–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai M, Jungmann R, Yin P. 2016. Optical imaging of individual biomolecules in densely packed clusters. Nat. Nanotechnol 11(9):798–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Ventra M, Taniguchi M. 2016. Decoding DNA, RNA and peptides with quantum tunnelling. Nat. Nanotechnol 11(2):117–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donis-Keller H, Maxam AM, Gilbert W. 1977. Mapping adenines, guanines, and pyrimidines in RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 4(8):2527–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edman P 1949. A method for the determination of amino acid sequence in peptides. Arch. Biochem 22(3):475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eid J, Fehr A, Gray J, Luong K, Lyle J, et al. 2009. Real-time DNA sequencing from single polymerase molecules. Science. 323(5910):133–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Filius M, Kim SH, Severins I, Joo C. 2021. High-Resolution Single-Molecule FRET via DNA eXchange (FRET X). Nano Lett. 21(7):3295–3301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Free RB, Hazelwood LA, Sibley DR. 2009. Identifying Novel Protein-Protein Interactions Using Co-Immunoprecipitation and Mass Spectroscopy. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. Editor. Board Jacqueline N Crawley Al 0 5:Unit-5.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Ginkel J, Filius M, Szczepaniak M, Tulinski P, Meyer AS, Joo C. 2018. Single-molecule peptide fingerprinting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 115(13):3338–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gold L, Ayers D, Bertino J, Bock C, Bock A, et al. 2010. Aptamer-based multiplexed proteomic technology for biomarker discovery. PloS One. 5(12):e15004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gopalkrishnan N, Punthambaker S, Schaus TE, Church GM, Yin P. 2020. A DNA nanoscope that identifies and precisely localizes over a hundred unique molecular features with nanometer accuracy. bioRxiv. 2020.08.27.271072 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Govindarajan R, Duraiyan J, Kaliyappan K, Palanisamy M. 2012. Microarray and its applications. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci 4(Suppl 2):S310–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He P, Williams BA, Trout D, Marinov GK, Amrhein H, et al. 2020. The changing mouse embryo transcriptome at whole tissue and single-cell resolution. Nature. 583(7818):760–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heather JM, Chain B. 2016. The sequence of sequencers: The history of sequencing DNA. Genomics. 107(1):1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heller MJ. 2002. DNA Microarray Technology: Devices, Systems, and Applications. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 4(1):129–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernandez ET, Swaminathan J, Marcotte EM, Anslyn EV. 2017. Solution-phase and solid-phase sequential, selective modification of side chains in KDYWEC and KDYWE as models for usage in single-molecule protein sequencing. New J. Chem 41(2):462–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Houghtaling J, Ying C, Eggenberger OM, Fennouri A, Nandivada S, et al. 2019. Estimation of Shape, Volume, and Dipole Moment of Individual Proteins Freely Transiting a Synthetic Nanopore. ACS Nano. 13(5):5231–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howard CJ, Floyd BM, Bardo AM, Swaminathan J, Marcotte EM, Anslyn EV. 2020. Solid-Phase Peptide Capture and Release for Bulk and Single-Molecule Proteomics. ACS Chem. Biol 15(6):1401–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu Q, Li H, Wang L, Gu H, Fan C. 2019. DNA Nanotechnology-Enabled Drug Delivery Systems. Chem. Rev 119(10):6459–6506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu Z-L, Huo M-Z, Ying Y-L, Long Y-T. 2021. Biological Nanopore Approach for Single-Molecule Protein Sequencing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 60(27):14738–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang B, Wu H, Bhaya D, Grossman A, Granier S, et al. 2007. Counting Low-Copy Number Proteins in a Single Cell. Science. 315(5808):81–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang G, Voet A, Maglia G. 2019. FraC nanopores with adjustable diameter identify the mass of opposite-charge peptides with 44 dalton resolution. Nat. Commun 10(1):835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang G, Willems K, Bartelds M, van Dorpe P, Soskine M, Maglia G. 2020. Electro-Osmotic Vortices Promote the Capture of Folded Proteins by PlyAB Nanopores. Nano Lett. 20(5):3819–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jain M, Olsen HE, Paten B, Akeson M. 2016. The Oxford Nanopore MinION: delivery of nanopore sequencing to the genomics community. Genome Biol. 17(1):239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaboord B, Perr M. 2008. Isolation of proteins and protein complexes by immunoprecipitation. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 424:349–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kafader JO, Melani RD, Senko MW, Makarov AA, Kelleher NL, Compton PD. 2019. Measurement of Individual Ions Sharply Increases the Resolution of Orbitrap Mass Spectra of Proteins. Anal. Chem 91(4):2776–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kasianowicz JJ, Brandin E, Branton D, Deamer DW. 1996. Characterization of individual polynucleotide molecules using a membrane channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 93(24):13770–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keifer DZ, Jarrold MF. 2017. Single-molecule mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev 36(6):715–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kennedy E, Dong Z, Tennant C, Timp G. 2016. Reading the primary structure of a protein with 0.07 nm 3 resolution using a subnanometre-diameter pore. Nat. Nanotechnol 11(11):968–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kothapalli R, Yoder SJ, Mane S, Loughran TP. 2002. Microarray results: how accurate are they? BMC Bioinformatics. 3(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuchino Y, Nishimura S. 1989. Enzymatic RNA sequencing. Methods Enzymol. 180:154–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Lannoy C, Filius M, van Wee R, Joo C, de Ridder D 2021. Evaluation of FRET X for Single-Molecule Protein Fingerprinting. bioRxiv. 2021.06.30.450512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Laursen RA. 1971. Solid-Phase Edman Degradation. Eur. J. Biochem 20(1):89–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li S, Wu X-Y, Li M-Y, Liu S-C, Ying Y-L, Long Y-T. 2020. T232K/K238Q Aerolysin Nanopore for Mapping Adjacent Phosphorylation Sites of a Single Tau Peptide. Small Methods. 4(11):2000014 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li SFY, Wu YS. 2000. ELECTROPHORESIS ∣ Capillary Electrophoresis. In Encyclopedia of Separation Science, ed Wilson ID, pp. 1176–87. Oxford: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luo L, Boerwinkle E, Xiong M. 2011. Association studies for next-generation sequencing. Genome Res. 21(7):1099–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.MacDonald JI, Munch HK, Moore T, Francis MB. 2015. One-step site-specific modification of native proteins with 2-pyridinecarboxyaldehydes. Nat. Chem. Biol 11(5):326–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mahdessian D, Cesnik AJ, Gnann C, Danielsson F, Stenström L, et al. 2021. Spatiotemporal dissection of the cell cycle with single-cell proteogenomics. Nature. 590(7847):649–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maillard RA, Chistol G, Sen M, Righini M, Tan J, et al. 2011. ClpX(P) Generates Mechanical Force to Unfold and Translocate Its Protein Substrates. Cell. 145(3):459–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mann M 2016. The Rise of Mass Spectrometry and the Fall of Edman Degradation. Clin. Chem 62(1):293–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manrao EA, Derrington IM, Laszlo AH, Langford KW, Hopper MK, et al. 2012. Reading DNA at single-nucleotide resolution with a mutant MspA nanopore and phi29 DNA polymerase. Nat. Biotechnol 30(4):349–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marx V 2019. A dream of single-cell proteomics. Nat. Methods 16(9):809–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matheron L, van den Toorn H, Heck AJR, Mohammed S. 2014. Characterization of biases in phosphopeptide enrichment by Ti(4+)-immobilized metal affinity chromatography and TiO2 using a massive synthetic library and human cell digests. Anal. Chem 86(16):8312–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maulbetsch W, Wiener B, Poole W, Bush J, Stein D. 2016. Preserving the Sequence of a Biopolymer’s Monomers as They Enter an Electrospray Mass Spectrometer. Phys. Rev. Appl 6(5):054006 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mereuta L, Roy M, Asandei A, Lee JK, Park Y, et al. 2014. Slowing down single-molecule trafficking through a protein nanopore reveals intermediates for peptide translocation. Sci. Rep 4:3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nivala J, Marks DB, Akeson M. 2013. Unfoldase-mediated protein translocation through an α-hemolysin nanopore. Nat. Biotechnol 31(3):247–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nivala J, Mulroney L, Li G, Schreiber J, Akeson M. 2014. Discrimination among Protein Variants Using an Unfoldase-Coupled Nanopore. ACS Nano. 8(12):12365–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ohayon S, Girsault A, Nasser M, Shen-Orr S, Meller A. 2019. Simulation of single-protein nanopore sensing shows feasibility for whole-proteome identification. PLOS Comput. Biol 15(5):e1007067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ohshiro T 2014. Detection of post-translational modifications in single peptides using electron tunnelling currents. Nat. Nanotechnol 9:6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ouldali H, Sarthak K, Ensslen T, Piguet F, Manivet P, et al. 2020. Electrical recognition of the twenty proteinogenic amino acids using an aerolysin nanopore. Nat. Biotechnol 38(2):176–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Palmblad M 2021. Theoretical Considerations for Next-Generation Proteomics. J. Proteome Res 20(6):3395–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Petelski AA, Emmott E, Leduc A, Huffman RG, Specht H, et al. 2021. Multiplexed single-cell proteomics using SCoPE2. bioRxiv. 2021.03.12.435034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Piguet F, Ouldali H, Pastoriza-Gallego M, Manivet P, Pelta J, Oukhaled A. 2018. Identification of single amino acid differences in uniformly charged homopolymeric peptides with aerolysin nanopore. Nat. Commun 9(1):966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ren R, Zhang Y, Nadappuram BP, Akpinar B, Klenerman D, et al. 2017. Nanopore extended field-effect transistor for selective single-molecule biosensing. Nat. Commun 8(1):586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Restrepo-Pérez L, Huang G, Bohländer PR, Worp N, Eelkema R, et al. 2019. Resolving Chemical Modifications to a Single Amino Acid within a Peptide Using a Biological Nanopore. ACS Nano. 13(12):13668–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Restrepo-Pérez L, Joo C, Dekker C. 2018. Paving the way to single-molecule protein sequencing. Nat. Nanotechnol 13(9):786–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Restrepo-Pérez L, Wong CH, Maglia G, Dekker C, Joo C. 2019. Label-Free Detection of Post-translational Modifications with a Nanopore. Nano Lett. 19(11):7957–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Riley NM, Coon JJ. 2016. Phosphoproteomics in the Age of Rapid and Deep Proteome Profiling. Anal. Chem 88(1):74–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rodriguez-Larrea D 2021. Single-amino acid discrimination in proteins with homogeneous nanopore sensors and neural networks. Biosens. Bioelectron 180:113108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rodriguez-Larrea D, Bayley H. 2013. Multistep protein unfolding during nanopore translocation. Nat. Nanotechnol 8(4):288–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rodriques SG, Marblestone AH, Boyden ES. 2019. A theoretical analysis of single molecule protein sequencing via weak binding spectra. PLOS ONE. 14(3):e0212868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rose RJ, Damoc E, Denisov E, Makarov A, Heck AJR. 2012. High-sensitivity Orbitrap mass analysis of intact macromolecular assemblies. Nat. Methods 9(11):1084–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Shin JW, Rood JE, Hupalowska A, Regev A, Heyn H. 2021. Building a high-quality Human Cell Atlas. Nat. Biotechnol 39(2):149–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sanger F, Thompson EOP. 1953. The amino-acid sequence in the glycyl chain of insulin. 2. The investigation of peptides from enzymic hydrolysates. Biochem. J 53(3):366–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sanger F, Tuppy H. 1951. The amino-acid sequence in the phenylalanyl chain of insulin. 1. The identification of lower peptides from partial hydrolysates. Biochem. J 49(4):463–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schaus TE, Woo S, Xuan F, Chen X, Yin P. 2017. A DNA nanoscope via auto-cycling proximity recording. Nat. Commun 8(1):696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schmid S, Stömmer P, Dietz H, Dekker C. 2021. Nanopore electro-osmotic trap for the label-free study of single proteins and their conformations. bioRxiv. 2021.03.09.434634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schnitzbauer J, Strauss MT, Schlichthaerle T, Schueder F, Jungmann R. 2017. Super-resolution microscopy with DNA-PAINT. Nat. Protoc 12(6):1198–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Smith RD, Cheng X, Brace JE, Hofstadler SA, Anderson GA. 1994. Trapping, detection and reaction of very large single molecular ions by mass spectrometry. Nature. 369(6476):137–39 [Google Scholar]

- 92.Steen H, Mann M. 2004. The abc’s (and xyz’s) of peptide sequencing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 5(9):699–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Storm AJ, Storm C, Chen J, Zandbergen H, Joanny J-F, Dekker C. 2005. Fast DNA translocation through a solid-state nanopore. Nano Lett. 5(7):1193–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Swaminathan J, Boulgakov AA, Hernandez ET, Bardo AM, Bachman JL, et al. 2018. Highly parallel single-molecule identification of proteins in zeptomole-scale mixtures. Nat. Biotechnol 36(11):1076–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Swaminathan J, Boulgakov AA, Marcotte EM. 2015. A Theoretical Justification for Single Molecule Peptide Sequencing. PLOS Comput. Biol 11(2):e1004080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Takagi T, Suzuki M, Baba T, Minegishi K, Sasaki S. 1984. Complete amino acid sequence of amelogenin in developing bovine enamel. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 121(2):592–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Timp W, Timp G. 2020. Beyond mass spectrometry, the next step in proteomics. Sci. Adv 6(2):eaax8978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 76(9):4350–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tullman J, Callahan N, Ellington B, Kelman Z, Marino JP. 2019. Engineering ClpS for selective and enhanced N-terminal amino acid binding. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 103(6):2621–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wagner DE, Klein AM. 2020. Lineage tracing meets single-cell omics: opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet 21(7):410–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang L, Li PCH. 2011. Microfluidic DNA microarray analysis: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 687(1):12–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang R, Gilboa T, Song J, Huttner D, Grinstaff MW, Meller A. 2018. Single-Molecule Discrimination of Labeled DNAs and Polypeptides Using Photoluminescent-Free TiO2 Nanopores. ACS Nano. 12(11):11648–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wei X, Ma D, Jing L, Wang LY, Wang X, et al. 2020. Enabling nanopore technology for sensing individual amino acids by a derivatization strategy. J. Mater. Chem. B 8(31):6792–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wingren C 2016. Antibody-Based Proteomics. In Proteogenomics, ed Végvári Á, pp. 163–79. Cham: Springer International Publishing [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wiśniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. 2009. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat. Methods 6(5):359–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yalow RS, Berson SA. 1960. Immunoassay of endogenous plasma insulin in man. J. Clin. Invest 39:1157–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yao Y, Docter M, van Ginkel J, de Ridder D, Joo C. 2015. Single-molecule protein sequencing through fingerprinting: computational assessment. Phys. Biol 12(5):055003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yates JR, Ruse CI, Nakorchevsky A. 2009. Proteomics by Mass Spectrometry: Approaches, Advances, and Applications. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 11(1):49–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yusko EC, Bruhn BR, Eggenberger OM, Houghtaling J, Rollings RC, et al. 2017. Real-time shape approximation and fingerprinting of single proteins using a nanopore. Nat. Nanotechnol 12(4):360–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang L, Floyd BM, Chilamari M, Mapes J, Swaminathan J, et al. 2021. Photoredox-catalyzed decarboxylative C-terminal differentiation for bulk and single molecule proteomics. bioRxiv. 2021.07.08.451692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang S, Huang G, Versloot R, Herwig BM, de Souza PCT, et al. 2020. Bottom-up fabrication of a multi-component nanopore sensor that unfolds, processes and recognizes single proteins. bioRxiv. 2020.12.04.411884 [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhao Y, Ashcroft B, Zhang P, Liu H, Sen S, et al. 2014. Single-molecule spectroscopy of amino acids and peptides by recognition tunnelling. Nat. Nanotechnol 9(6):466–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zubarev RA. 2013. The challenge of the proteome dynamic range and its implications for in-depth proteomics. Proteomics. 13(5):723–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zwolak M, Di Ventra M. 2005. Electronic signature of DNA nucleotides via transverse transport. Nano Lett. 5(3):421–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Brinkerhoff H, Kang ASW, Liu J, Aksimentiev A, Dekker C. 2021. Infinite re-reading of single proteins at single-amino-acid resolution using nanopore sequencing. bioRxiv. 2021.07.13.452225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sampath G 2015. Amino acid discrimination in a nanopore and the feasibility of sequencing peptides with a tandem cell and exopeptidase. RSC Adv. 5:30694–30700 [Google Scholar]