Abstract

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) “Standards of Care in Diabetes” includes the ADA’s current clinical practice recommendations and is intended to provide the components of diabetes care, general treatment goals and guidelines, and tools to evaluate quality of care. Members of the ADA Professional Practice Committee, a multidisciplinary expert committee, are responsible for updating the Standards of Care annually, or more frequently as warranted. For a detailed description of ADA standards, statements, and reports, as well as the evidence-grading system for ADA’s clinical practice recommendations and a full list of Professional Practice Committee members, please refer to Introduction and Methodology. Readers who wish to comment on the Standards of Care are invited to do so at professional.diabetes.org/SOC.

Pharmacologic Therapy for Adults with Type 1 Diabetes

Recommendations

9.1 Most individuals with type 1 diabetes should be treated with multiple daily injections of prandial and basal insulin, or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. A

9.2 Most individuals with type 1 diabetes should use rapid-acting insulin analogs to reduce hypoglycemia risk. A

9.3 Individuals with type 1 diabetes should receive education on how to match mealtime insulin doses to carbohydrate intake, fat and protein content, and anticipated physical activity. B

Insulin Therapy

Because the hallmark of type 1 diabetes is absent or near-absent β-cell function, insulin treatment is essential for individuals with type 1 diabetes. In addition to hyperglycemia, insulinopenia can contribute to other metabolic disturbances like hypertriglyceridemia and ketoacidosis as well as tissue catabolism that can be life threatening. Severe metabolic decompensation can be, and was, mostly prevented with once- or twice-daily injections for the six or seven decades after the discovery of insulin. However, over the past three decades, evidence has accumulated supporting more intensive insulin replacement, using multiple daily injections of insulin or continuous subcutaneous administration through an insulin pump, as providing the best combination of effectiveness and safety for people with type 1 diabetes. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) demonstrated that intensive therapy with multiple daily injections or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) reduced A1C and was associated with improved long-term outcomes (1–3). The study was carried out with short-acting (regular) and intermediate-acting (NPH) human insulins. In this landmark trial, lower A1C with intensive control (7%) led to ∼50% reductions in microvascular complications over 6 years of treatment. However, intensive therapy was associated with a higher rate of severe hypoglycemia than conventional treatment (62 compared with 19 episodes per 100 patient-years of therapy). Follow-up of subjects from the DCCT more than 10 years after the active treatment component of the study demonstrated fewer macrovascular as well as fewer microvascular complications in the group that received intensive treatment (2,4).

Insulin replacement regimens typically consist of basal insulin, mealtime insulin, and correction insulin (5). Basal insulin includes NPH insulin, long-acting insulin analogs, and continuous delivery of rapid-acting insulin via an insulin pump. Basal insulin analogs have longer duration of action with flatter, more constant plasma concentrations and activity profiles than NPH insulin; rapid-acting analogs (RAA) have a quicker onset and peak and shorter duration of action than regular human insulin. In people with type 1 diabetes, treatment with analog insulins is associated with less hypoglycemia and weight gain as well as lower A1C compared with human insulins (6–8). More recently, two injectable insulin formulations with enhanced rapid-action profiles have been introduced. Inhaled human insulin has a rapid peak and shortened duration of action compared with RAA and may cause less hypoglycemia and weight gain (9) (see also subsection alternative insulin routes in pharmacologic therapy for adults with type 2 diabetes), and faster-acting insulin aspart and insulin lispro-aabc may reduce prandial excursions better than RAA (10–12). In addition, longer-acting basal analogs (U-300 glargine or degludec) may confer a lower hypoglycemia risk compared with U-100 glargine in individuals with type 1 diabetes (13,14). Despite the advantages of insulin analogs in individuals with type 1 diabetes, for some individuals the expense and/or intensity of treatment required for their use is prohibitive. There are multiple approaches to insulin treatment, and the central precept in the management of type 1 diabetes is that some form of insulin be given in a planned regimen tailored to the individual to keep them safe and out of diabetic ketoacidosis and to avoid significant hypoglycemia, with every effort made to reach the individual’s glycemic targets.

Most studies comparing multiple daily injections with CSII have been relatively small and of short duration. However, a systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that CSII via pump therapy has modest advantages for lowering A1C (−0.30% [95% CI −0.58 to −0.02]) and for reducing severe hypoglycemia rates in children and adults (15). However, there is no consensus to guide the choice of injection or pump therapy in a given individual, and research to guide this decision-making is needed (16). The arrival of continuous glucose monitors (CGM) to clinical practice has proven beneficial in people using insulin therapy. Its use is now considered standard of care for most people with type 1 diabetes (5) (see Section 7, “Diabetes Technology”). Reduction of nocturnal hypoglycemia in individuals with type 1 diabetes using insulin pumps with CGM is improved by automatic suspension of insulin delivery at a preset glucose level (16–18). When choosing among insulin delivery systems, individual preferences, cost, insulin type and dosing regimen, and self-management capabilities should be considered (see Section 7, “Diabetes Technology”).

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has now approved multiple hybrid closed-loop pump systems (also called automated insulin delivery [AID] systems). The safety and efficacy of hybrid closed-loop systems has been supported in the literature in adolescents and adults with type 1 diabetes (19,20), and evidence suggests that a closed-loop system is superior to sensor-augmented pump therapy for glycemic control and reduction of hypoglycemia over 3 months of comparison in children and adults with type 1 diabetes (21). In the International Diabetes Closed Loop (iDCL) trial, a 6-month trial in people with type 1 diabetes at least 14 years of age, the use of a closed-loop system was associated with a greater percentage of time spent in the target glycemic range, reduced mean glucose and A1C levels, and a lower percentage of time spent in hypoglycemia compared with use of a sensor-augmented pump (22).

Intensive insulin management using a version of CSII and continuous glucose monitoring should be considered in most individuals with type 1 diabetes. AID systems may be considered in individuals with type 1 diabetes who are capable of using the device safely (either by themselves or with a caregiver) in order to improve time in range and reduce A1C and hypoglycemia (22). See Section 7, “Diabetes Technology,” for a full discussion of insulin delivery devices.

In general, individuals with type 1 diabetes require 50% of their daily insulin as basal and 50% as prandial, but this is dependent on a number of factors, including whether the individual consumes lower or higher carbohydrate meals. Total daily insulin requirements can be estimated based on weight, with typical doses ranging from 0.4 to 1.0 units/kg/day. Higher amounts are required during puberty, pregnancy, and medical illness. The American Diabetes Association/JDRF Type 1 Diabetes Sourcebook notes 0.5 units/kg/day as a typical starting dose in individuals with type 1 diabetes who are metabolically stable, with half administered as prandial insulin given to control blood glucose after meals and the other half as basal insulin to control glycemia in the periods between meal absorption (23); this guideline provides detailed information on intensification of therapy to meet individualized needs. In addition, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) position statement “Type 1 Diabetes Management Through the Life Span” provides a thorough overview of type 1 diabetes treatment (24).

Typical multidose regimens for individuals with type 1 diabetes combine premeal use of shorter-acting insulins with a longer-acting formulation. The long-acting basal dose is titrated to regulate overnight and fasting glucose. Postprandial glucose excursions are best controlled by a well-timed injection of prandial insulin. The optimal time to administer prandial insulin varies, based on the pharmacokinetics of the formulation (regular, RAA, inhaled), the premeal blood glucose level, and carbohydrate consumption. Recommendations for prandial insulin dose administration should therefore be individualized. Physiologic insulin secretion varies with glycemia, meal size, meal composition, and tissue demands for glucose. To approach this variability in people using insulin treatment, strategies have evolved to adjust prandial doses based on predicted needs. Thus, education on how to adjust prandial insulin to account for carbohydrate intake, premeal glucose levels, and anticipated activity can be effective and should be offered to most individuals (25,26). For individuals in whom carbohydrate counting is effective, estimates of the fat and protein content of meals can be incorporated into their prandial dosing for added benefit (27) (see Section 5, “Facilitating Positive Health Behaviors and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes”).

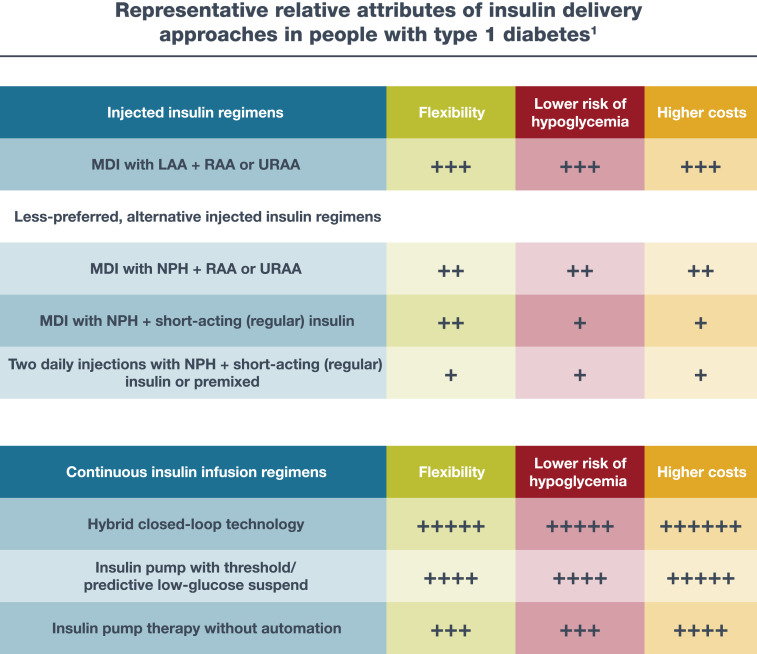

The 2021 ADA/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) consensus report on the management of type 1 diabetes in adults summarizes different insulin regimens and glucose monitoring strategies in individuals with type 1 diabetes (Fig. 9.1 and Table 9.1) (5).

Figure 9.1.

Choices of insulin regimens in people with type 1 diabetes. Continuous glucose monitoring improves outcomes with injected or infused insulin and is superior to blood glucose monitoring. Inhaled insulin may be used in place of injectable prandial insulin in the U.S. 1The number of plus signs (+) is an estimate of relative association of the regimen with increased flexibility, lower risk of hypoglycemia, and higher costs between the considered regimens. LAA, long-acting insulin analog; MDI, multiple daily injections; RAA, rapid-acting insulin analog; URAA, ultra-rapid-acting insulin analog. Reprinted from Holt et al. (5).

Table 9.1.

Examples of subcutaneous insulin regimens

| Regimen | Timing and distribution | Advantages | Disadvantages | Adjusting doses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regimens that more closely mimic normal insulin secretion | ||||

| Insulin pump therapy (hybrid closed-loop, low-glucose suspend, CGM-augmented open-loop, BGM-augmented open-loop) | Basal delivery of URAA or RAA; generally 40–60% of TDD. Mealtime and correction: URAA or RAA by bolus based on ICR and/or ISF and target glucose, with pre-meal insulin ∼15 min before eating. |

Can adjust basal rates for varying insulin sensitivity by time of day, for exercise and for sick days. Flexibility in meal timing and content. Pump can deliver insulin in increments of fractions of units. Potential for integration with CGM for low-glucose suspend or hybrid closed-loop. TIR % highest and TBR % lowest with: hybrid closed-loop > low-glucose suspend > CGM-augmented open-loop > BGM-augmented open-loop. |

Most expensive regimen. Must continuously wear one or more devices. Risk of rapid development of ketosis or DKA with interruption of insulin delivery. Potential reactions to adhesives and site infections. Most technically complex approach (harder for people with lower numeracy or literacy skills). |

Mealtime insulin: if carbohydrate counting is accurate, change ICR if glucose after meal consistently out of target. Correction insulin: adjust ISF and/or target glucose if correction does not consistently bring glucose into range. Basal rates: adjust based on overnight, fasting or daytime glucose outside of activity of URAA/RAA bolus. |

| MDI: LAA + flexible doses of URAA or RAA at meals | LAA once daily (insulin detemir or insulin glargine may require twice-daily dosing); generally 50% of TDD. Mealtime and correction: URAA or RAA based on ICR and/or ISF and target glucose. |

Can use pens for all components. Flexibility in meal timing and content. Insulin analogs cause less hypoglycemia than human insulins. |

At least four daily injections. Most costly insulins. Smallest increment of insulin is 1 unit (0.5 unit with some pens). LAAs may not cover strong dawn phenomenon (rise in glucose in early morning hours) as well as pump therapy. |

Mealtime insulin: if carbohydrate counting is accurate, change ICR if glucose after meal consistently out of target. Correction insulin: adjust ISF and/or target glucose if correction does not consistently bring glucose into range. LAA: based on overnight or fasting glucose or daytime glucose outside of activity time course, or URAA or RAA injections. |

| MDI regimens with less flexibility | ||||

| Four injections daily with fixed doses of N and RAA | Pre-breakfast: RAA ∼20% of TDD. Pre-lunch: RAA ∼10% of TDD. Pre-dinner: RAA ∼10% of TDD. Bedtime: N ∼50% of TDD. |

May be feasible if unable to carbohydrate count. All meals have RAA coverage. N is less expensive than LAAs. |

Shorter duration RAA may lead to basal deficit during day; may need twice-daily N. Greater risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia with N. Requires relatively consistent mealtimes and carbohydrate intake. |

Pre-breakfast RAA: based on BGM after breakfast or before lunch. Pre-lunch RAA: based on BGM after lunch or before dinner. Pre-dinner RAA: based on BGM after dinner or at bedtime. Evening N: based on fasting or overnight BGM. |

| Four injections daily with fixed doses of N and R | Pre-breakfast: R ∼20% of TDD. Pre-lunch: R ∼10% of TDD. Pre-dinner: R ∼10% of TDD. Bedtime: N ∼50% of TDD. |

May be feasible if unable to carbohydrate count. R can be dosed based on ICR and correction. All meals have R coverage. Least expensive insulins. |

Greater risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia with N. Greater risk of delayed post-meal hypoglycemia with R. Requires relatively consistent mealtimes and carbohydrate intake. R must be injected at least 30 min before meal for better effect. |

Pre-breakfast R: based on BGM after breakfast or before lunch. Pre-lunch R: based on BGM after lunch or before dinner. Pre-dinner R: based on BGM after dinner or at bedtime. Evening N: based on fasting or overnight BGM. |

| Regimens with fewer daily injections | ||||

| Three injections daily: N+R or N+RAA | Pre-breakfast: ∼40% N + ∼15% R or RAA. Pre-dinner: ∼15% R or RAA. Bedtime: 30% N. |

Morning insulins can be mixed in one syringe. May be appropriate for those who cannot take injection in middle of day. Morning N covers lunch to some extent. Same advantages of RAAs over R. Least (N+R) or less expensive insulins than MDI with analogs. |

Greater risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia with N than LAAs. Greater risk of delayed post-meal hypoglycemia with R than RAAs. Requires relatively consistent mealtimes and carbohydrate intake. Coverage of post-lunch glucose often suboptimal. R must be injected at least 30 min before meal for better effect. |

Morning N: based on pre-dinner BGM. Morning R: based on pre-lunch BGM. Morning RAA: based on post-breakfast or pre-lunch BGM. Pre-dinner R: based on bedtime BGM. Pre-dinner RAA: based on post-dinner or bedtime BGM. Evening N: based on fasting BGM. |

| Twice-daily “split-mixed”: N+R or N+RAA | Pre-breakfast: ∼40% N + ∼15% R or RAA. Pre-dinner: ∼30% N + ∼15% R or RAA. |

Least number of injections for people with strong preference for this. Insulins can be mixed in one syringe. Least (N+R) or less (N+RAA) expensive insulins vs analogs. Eliminates need for doses during the day. |

Risk of hypoglycemia in afternoon or middle of night from N. Fixed mealtimes and meal content. Coverage of post-lunch glucose often suboptimal. Difficult to reach targets for blood glucose without hypoglycemia. |

Morning N: based on pre-dinner BGM. Morning R: based on pre-lunch BGM. Morning RAA: based on post-breakfast or pre-lunch BGM. Evening R: based on bedtime BGM. Evening RAA: based on post-dinner or bedtime BGM. Evening N: based on fasting BGM. |

BGM, blood glucose monitoring; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; ICR, insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio; ISF, insulin sensitivity factor; LAA, long-acting analog; MDI, multiple daily injections; N, NPH insulin; R, short-acting (regular) insulin; RAA, rapid-acting analog; TDD, total daily insulin dose; URAA, ultra-rapid-acting analog. Reprinted from Holt et al. (5).

Insulin Injection Technique

Ensuring that individuals and/or caregivers understand correct insulin injection technique is important to optimize glucose control and insulin use safety. Thus, it is important that insulin be delivered into the proper tissue in the correct way. Recommendations have been published elsewhere outlining best practices for insulin injection (28). Proper insulin injection technique includes injecting into appropriate body areas, injection site rotation, appropriate care of injection sites to avoid infection or other complications, and avoidance of intramuscular (IM) insulin delivery.

Exogenously delivered insulin should be injected into subcutaneous tissue, not intramuscularly. Recommended sites for insulin injection include the abdomen, thigh, buttock, and upper arm. Insulin absorption from IM sites differs from that in subcutaneous sites and is also influenced by the activity of the muscle. Inadvertent IM injection can lead to unpredictable insulin absorption and variable effects on glucose and is associated with frequent and unexplained hypoglycemia. Risk for IM insulin delivery is increased in younger, leaner individuals when injecting into the limbs rather than truncal sites (abdomen and buttocks) and when using longer needles. Recent evidence supports the use of short needles (e.g., 4-mm pen needles) as effective and well tolerated when compared with longer needles, including a study performed in adults with obesity (29).

Injection site rotation is additionally necessary to avoid lipohypertrophy, an accumulation of subcutaneous fat in response to the adipogenic actions of insulin at a site of multiple injections. Lipohypertrophy appears as soft, smooth raised areas several centimeters in breadth and can contribute to erratic insulin absorption, increased glycemic variability, and unexplained hypoglycemic episodes. People treated with insulin and/or caregivers should receive education about proper injection site rotation and how to recognize and avoid areas of lipohypertrophy. As noted in Table 4.1, examination of insulin injection sites for the presence of lipohypertrophy, as well as assessment of injection device use and injection technique, are key components of a comprehensive diabetes medical evaluation and treatment plan. Proper insulin injection technique may lead to more effective use of this therapy and, as such, holds the potential for improved clinical outcomes.

Noninsulin Treatments for Type 1 Diabetes

Injectable and oral glucose-lowering drugs have been studied for their efficacy as adjuncts to insulin treatment of type 1 diabetes. Pramlintide is based on the naturally occurring β-cell peptide amylin and is approved for use in adults with type 1 diabetes. Clinical trials have demonstrated a modest reduction in A1C (0.3–0.4%) and modest weight loss (∼1 kg) with pramlintide (30–33). Similarly, results have been reported for several agents currently approved only for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. The addition of metformin in adults with type 1 diabetes caused small reductions in body weight and lipid levels but did not improve A1C (34,35). The largest clinical trials of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) in type 1 diabetes have been conducted with liraglutide 1.8 mg daily, showing modest A1C reductions (∼0.4%), decreases in weight (∼5 kg), and reductions in insulin doses (36,37). Similarly, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have been studied in clinical trials in people with type 1 diabetes, showing improvements in A1C, reduced body weight, and improved blood pressure (38–40); however, SGLT2 inhibitor use in type 1 diabetes is associated with an increased rate of diabetic ketoacidosis. The risks and benefits of adjunctive agents continue to be evaluated, with consensus statements providing guidance on patient selection and precautions (41).

Surgical Treatment for Type 1 Diabetes

Pancreas and Islet Transplantation

Successful pancreas and islet transplantation can normalize glucose levels and mitigate microvascular complications of type 1 diabetes. However, people receiving these treatments require lifelong immunosuppression to prevent graft rejection and/or recurrence of autoimmune islet destruction. Given the potential adverse effects of immunosuppressive therapy, pancreas transplantation should be reserved for people with type 1 diabetes undergoing simultaneous renal transplantation, following renal transplantation, or for those with recurrent ketoacidosis or severe hypoglycemia despite intensive glycemic management (42).

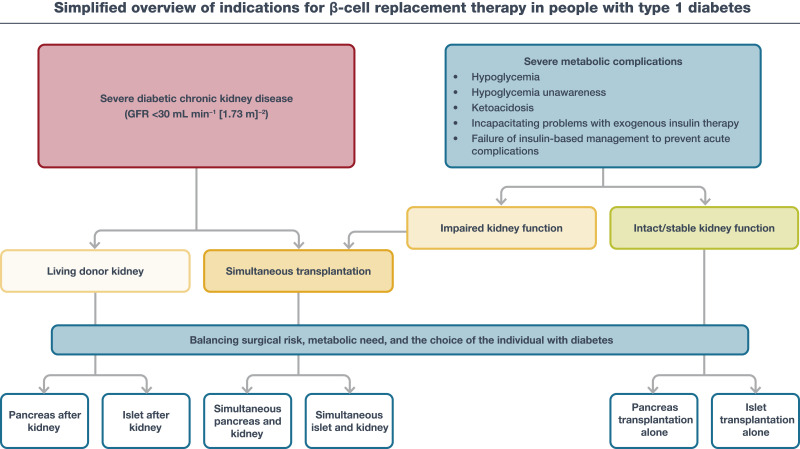

The 2021 ADA/EASD consensus report on the management of type 1 diabetes in adults offers a simplified overview of indications for β-cell replacement therapy in people with type 1 diabetes (Fig. 9.2) (5).

Figure 9.2.

Simplified overview of indications for β-cell replacement therapy in people with type 1 diabetes. The two main forms of β-cell replacement therapy are whole-pancreas transplantation or islet cell transplantation. β-Cell replacement therapy can be combined with kidney transplantation if the individual has end-stage renal disease, which may be performed simultaneously or after kidney transplantation. All decisions about transplantation must balance the surgical risk, metabolic need, and the choice of the individual with diabetes. GFR, glomerular filtration rate. Reprinted from Holt et al. (5).

Pharmacologic Therapy for Adults with Type 2 Diabetes

Recommendations

9.4a Healthy lifestyle behaviors, diabetes self-management education and support, avoidance of clinical inertia, and social determinants of health should be considered in the glucose-lowering management of type 2 diabetes. Pharmacologic therapy should be guided by person-centered treatment factors, including comorbidities and treatment goals. A

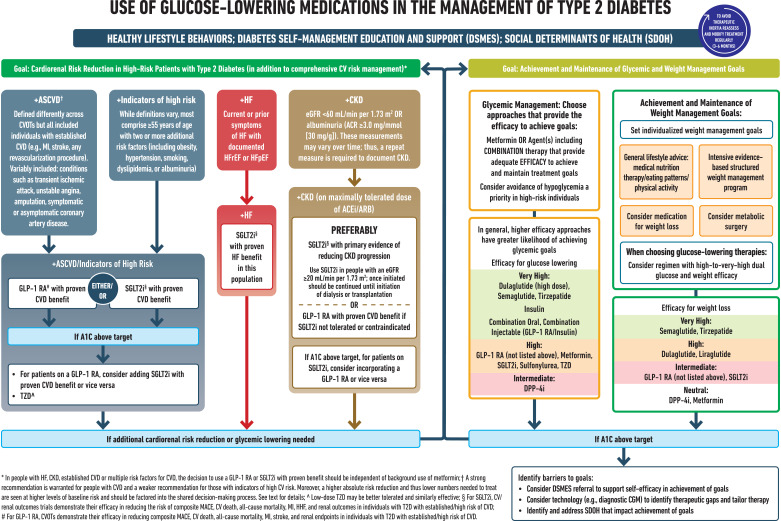

9.4b In adults with type 2 diabetes and established/high risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and/or chronic kidney disease, the treatment regimen should include agents that reduce cardiorenal risk (Fig. 9.3 and Table 9.2). A

9.4c Pharmacologic approaches that provide adequate efficacy to achieve and maintain treatment goals should be considered, such as metformin or other agents, including combination therapy (Fig. 9.3 and Table 9.2). A

9.4d Weight management is an impactful component of glucose-lowering management in type 2 diabetes. The glucose-lowering treatment regimen should consider approaches that support weight management goals (Fig. 9.3 and Table 9.2). A

9.5 Metformin should be continued upon initiation of insulin therapy (unless contraindicated or not tolerated) for ongoing glycemic and metabolic benefits. A

9.6 Early combination therapy can be considered in some individuals at treatment initiation to extend the time to treatment failure. A

9.7 The early introduction of insulin should be considered if there is evidence of ongoing catabolism (weight loss), if symptoms of hyperglycemia are present, or when A1C levels (>10% [86 mmol/mol]) or blood glucose levels (≥300 mg/dL [16.7 mmol/L]) are very high. E

9.8 A person-centered approach should guide the choice of pharmacologic agents. Consider the effects on cardiovascular and renal comorbidities, efficacy, hypoglycemia risk, impact on weight, cost and access, risk for side effects, and individual preferences (Fig. 9.3 and Table 9.2). E

9.9 Among individuals with type 2 diabetes who have established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or indicators of high cardiovascular risk, established kidney disease, or heart failure, a sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor and/or glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist with demonstrated cardiovascular disease benefit (Fig. 9.3, Table 9.2, Table 10.3B, and Table 10.3C) is recommended as part of the glucose-lowering regimen and comprehensive cardiovascular risk reduction, independent of A1C and in consideration of person-specific factors (Fig. 9.3) (see Section 10, “Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management,” for details on cardiovascular risk reduction recommendations). A

9.10 In adults with type 2 diabetes, a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist is preferred to insulin when possible. A

9.11 If insulin is used, combination therapy with a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist is recommended for greater efficacy, durability of treatment effect, and weight and hypoglycemia benefit. A

9.12 Recommendation for treatment intensification for individuals not meeting treatment goals should not be delayed. A

9.13 Medication regimen and medication-taking behavior should be reevaluated at regular intervals (every 3–6 months) and adjusted as needed to incorporate specific factors that impact choice of treatment (Fig. 4.1 and Table 9.2). E

9.14 Clinicians should be aware of the potential for overbasalization with insulin therapy. Clinical signals that may prompt evaluation of overbasalization include basal dose more than ∼0.5 units/kg/day, high bedtime–morning or postpreprandial glucose differential, hypoglycemia (aware or unaware), and high glycemic variability. Indication of overbasalization should prompt reevaluation to further individualize therapy. E

Figure 9.3.

Use of glucose-lowering medications in the management of type 2 diabetes. ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ACR, albumin-to-creatinine ratio; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CV, cardiovascular; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CVOT, cardiovascular outcomes trial; DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HHF, hospitalization for heart failure; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; SDOH, social determinants of health; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor; T2D, type 2 diabetes; TZD, thiazolidinedione. Adapted from Davies et al. (45).

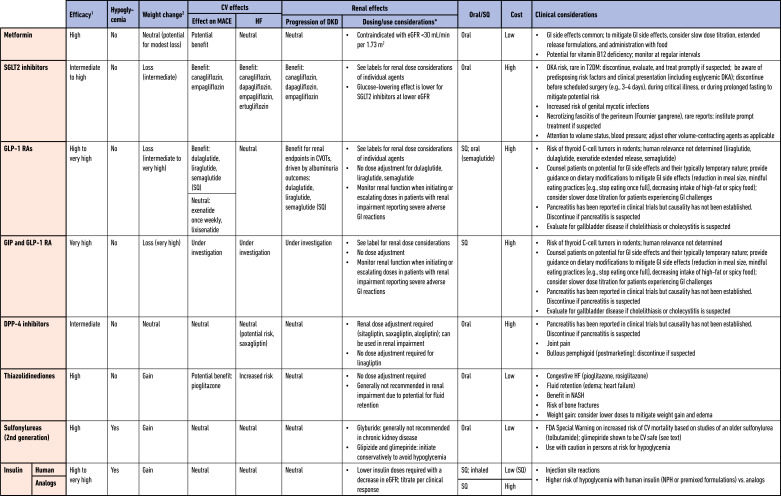

Table 9.2.

Medications for lowering glucose, summary of characteristics

CV, cardiovascular; CVOT, cardiovascular outcomes trial; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase 4; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; GI, gastrointestinal; GIP, gastric inhibitory polypeptide; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; HF, heart failure; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; SGLT2, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2; SQ, subcutaneous; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

For agent-specific dosing recommendations, please refer to manufacturers’ prescribing information.

Tsapas et al. (62).

The ADA/EASD consensus report “Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2022” (43–45) recommends a holistic, multifactorial person-centered approach accounting for the lifelong nature of type 2 diabetes. Person-specific factors that affect choice of treatment include individualized glycemic and weight goals, impact on weight, hypoglycemia and cardiorenal protection (see Section 10, “Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management,” and Section 11 “Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management”), underlying physiologic factors, side effect profiles of medications, complexity of regimen, regimen choice to optimize medication use and reduce treatment discontinuation, and access, cost, and availability of medication. Lifestyle modifications and health behaviors that improve health (see Section 5, “Facilitating Positive Health Behaviors and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes”) should be emphasized along with any pharmacologic therapy. Section 13, “Older Adults,” and Section 14, “Children and Adolescents,” have recommendations specific for older adults and for children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes, respectively. Section 10, “Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management,” and Section 11, “Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management,” have recommendations for the use of glucose-lowering drugs in the management of cardiovascular and renal disease, respectively.

Choice of Glucose-Lowering Therapy

Healthy lifestyle behaviors, diabetes self-management, education, and support, avoidance of clinical inertia, and social determinants of health should be considered in the glucose-lowering management of type 2 diabetes. Pharmacologic therapy should be guided by person-centered treatment factors, including comorbidities and treatment goals. Pharmacotherapy should be started at the time type 2 diabetes is diagnosed unless there are contraindications. Pharmacologic approaches that provide the efficacy to achieve treatment goals should be considered, such as metformin or other agents, including combination therapy, that provide adequate efficacy to achieve and maintain treatment goals (45). In adults with type 2 diabetes and established/high risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), heart failure (HF), and/or chronic kidney disease (CKD), the treatment regimen should include agents that reduce cardiorenal risk (see Fig. 9.3, Table 9.2, Section 10, “Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management,” and Section 11, “Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management”). Pharmacologic approaches that provide the efficacy to achieve treatment goals should be considered, specified as metformin or agent(s), including combination therapy, that provide adequate efficacy to achieve and maintain treatment goals ( Fig. 9.3 and Table 9.2). In general, higher-efficacy approaches have greater likelihood of achieving glycemic goals, with the following considered to have very high efficacy for glucose lowering: the GLP-1 RAs dulaglutide (high dose) and semaglutide, the gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP) and GLP-1 RA tirzepatide, insulin, combination oral therapy, and combination injectable therapy. Weight management is an impactful component of glucose-lowering management in type 2 diabetes (45,46). The glucose-lowering treatment regimen should consider approaches that support weight management goals, with very high efficacy for weight loss seen with semaglutide and tirzepatide (Fig. 9.3 and Table 9.2) (45).

Metformin is effective and safe, is inexpensive, and may reduce risk of cardiovascular events and death (47). Metformin is available in an immediate-release form for twice-daily dosing or as an extended-release form that can be given once daily. Compared with sulfonylureas, metformin as first-line therapy has beneficial effects on A1C, weight, and cardiovascular mortality (48).

The principal side effects of metformin are gastrointestinal intolerance due to bloating, abdominal discomfort, and diarrhea; these can be mitigated by gradual dose titration. The drug is cleared by renal filtration, and very high circulating levels (e.g., as a result of overdose or acute renal failure) have been associated with lactic acidosis. However, the occurrence of this complication is now known to be very rare, and metformin may be safely used in people with reduced estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR); the FDA has revised the label for metformin to reflect its safety in people with eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (49). A randomized trial confirmed previous observations that metformin use is associated with vitamin B12 deficiency and worsening of symptoms of neuropathy (50). This is compatible with a report from the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study (DPPOS) suggesting periodic testing of vitamin B12 (51) (see Section 3, “Prevention or Delay of Type 2 Diabetes and Associated Comorbidities”).

When A1C is ≥1.5% (12.5 mmol/mol) above the glycemic target (see Section 6, “Glycemic Targets,” for appropriate targets), many individuals will require dual-combination therapy or a more potent glucose-lowering agent to achieve and maintain their target A1C level (45,52) (Fig. 9.3 and Table 9.2). Insulin has the advantage of being effective where other agents are not and should be considered as part of any combination regimen when hyperglycemia is severe, especially if catabolic features (weight loss, hypertriglyceridemia, ketosis) are present. It is common practice to initiate insulin therapy for people who present with blood glucose levels ≥300 mg/dL (16.7 mmol/L) or A1C >10% (86 mmol/mol) or if the individual has symptoms of hyperglycemia (i.e., polyuria or polydipsia) or evidence of catabolism (weight loss) (Fig. 9.4). As glucose toxicity resolves, simplifying the regimen and/or changing to noninsulin agents is often possible. However, there is evidence that people with uncontrolled hyperglycemia associated with type 2 diabetes can also be effectively treated with a sulfonylurea (53).

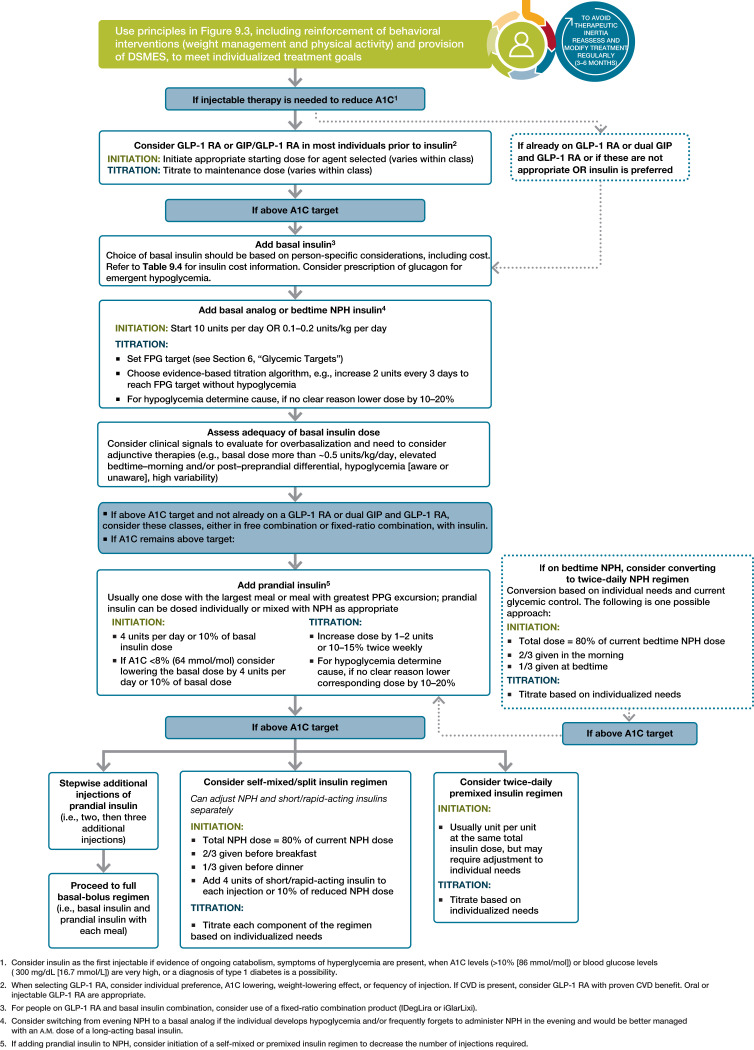

Figure 9.4.

Intensifying to injectable therapies in type 2 diabetes. DSMES, diabetes self-management education and support; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; max, maximum; PPG, postprandial glucose. Adapted from Davies et al. (43).

Combination Therapy

Because type 2 diabetes is a progressive disease in many individuals, maintenance of glycemic targets often requires combination therapy. Traditional recommendations have been to use stepwise addition of medications to metformin to maintain A1C at target. The advantage of this is to provide a clear assessment of the positive and negative effects of new drugs and reduce potential side effects and expense (54). However, there are data to support initial combination therapy for more rapid attainment of glycemic goals (55,56) and later combination therapy for longer durability of glycemic effect (57). The VERIFY (Vildagliptin Efficacy in combination with metfoRmln For earlY treatment of type 2 diabetes) trial demonstrated that initial combination therapy is superior to sequential addition of medications for extending primary and secondary failure (58). In the VERIFY trial, participants receiving the initial combination of metformin and the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitor vildagliptin had a slower decline of glycemic control compared with metformin alone and with vildagliptin added sequentially to metformin. These results have not been generalized to oral agents other than vildagliptin, but they suggest that more intensive early treatment has some benefits and should be considered through a shared decision-making process, as appropriate. Initial combination therapy should be considered in people presenting with A1C levels 1.5–2.0% above target. Finally, incorporation of high-glycemic-efficacy therapies or therapies for cardiovascular/renal risk reduction (e.g., GLP-1 RAs, SGLT2 inhibitors) may allow for weaning of the current regimen, particularly of agents that may increase the risk of hypoglycemia. Thus, treatment intensification may not necessarily follow a pure sequential addition of therapy but instead reflect a tailoring of the regimen in alignment with person-centered treatment goals (Fig. 9.3).

Recommendations for treatment intensification for people not meeting treatment goals should not be delayed. Shared decision-making is important in discussions regarding treatment intensification. The choice of medication added to initial therapy is based on the clinical characteristics of the individual and their preferences. Important clinical characteristics include the presence of established ASCVD or indicators of high ASCVD risk, HF, CKD, obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and risk for specific adverse drug effects, as well as safety, tolerability, and cost. Results from comparative effectiveness meta-analyses suggest that each new class of noninsulin agents added to initial therapy with metformin generally lowers A1C approximately 0.7–1.0% (59,60) (Fig. 9.3 and Table 9.2).

For people with type 2 diabetes and established ASCVD or indicators of high ASCVD risk, HF, or CKD, an SGLT2 inhibitor and/or GLP-1 RA with demonstrated CVD benefit (see Table 9.2, Table 10.3B, Table 10.3C, and Section 10, “Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management”) is recommended as part of the glucose-lowering regimen independent of A1C, independent of metformin use and in consideration of person-specific factors (Fig. 9.3). For people without established ASCVD, indicators of high ASCVD risk, HF, or CKD, medication choice is guided by efficacy in support of individualized glycemic and weight management goals, avoidance of side effects (particularly hypoglycemia and weight gain), cost/access, and individual preferences (61). A systematic review and network meta-analysis suggests greatest reductions in A1C level with insulin regimens and specific GLP-1 RAs added to metformin-based background therapy (62). In all cases, treatment regimens need to be continuously reviewed for efficacy, side effects, and burden (Table 9.2). In some instances, the individual will require medication reduction or discontinuation. Common reasons for this include ineffectiveness, intolerable side effects, expense, or a change in glycemic goals (e.g., in response to development of comorbidities or changes in treatment goals). Section 13, “Older Adults,” has a full discussion of treatment considerations in older adults, in whom changes of glycemic goals and de-escalation of therapy are common.

The need for the greater potency of injectable medications is common, particularly in people with a longer duration of diabetes. The addition of basal insulin, either human NPH or one of the long-acting insulin analogs, to oral agent regimens is a well-established approach that is effective for many individuals. In addition, evidence supports the utility of GLP-1 RAs in people not at glycemic goal. While most GLP-1 RAs are injectable, an oral formulation of semaglutide is commercially available (63). In trials comparing the addition of an injectable GLP-1 RA or insulin in people needing further glucose lowering, glycemic efficacy of injectable GLP-1 RA was similar or greater than that of basal insulin (64–70). GLP-1 RAs in these trials had a lower risk of hypoglycemia and beneficial effects on body weight compared with insulin, albeit with greater gastrointestinal side effects. Thus, trial results support GLP-1 RAs as the preferred option for individuals requiring the potency of an injectable therapy for glucose control (Fig. 9.4). In individuals who are intensified to insulin therapy, combination therapy with a GLP-1 RA has been shown to have greater efficacy and durability of glycemic treatment effect, as well as weight and hypoglycemia benefit, than treatment intensification with insulin alone (45). However, cost and tolerability issues are important considerations in GLP-1 RA use.

Costs for diabetes medications have increased dramatically over the past two decades, and an increasing proportion is now passed on to patients and their families (71). Table 9.3 provides cost information for currently approved noninsulin therapies. Of note, prices listed are average wholesale prices (AWP) (72) and National Average Drug Acquisition Costs (NADAC) (73), separate measures to allow for a comparison of drug prices, but do not account for discounts, rebates, or other price adjustments often involved in prescription sales that affect the actual cost incurred by the patient. Medication costs can be a major source of stress for people with diabetes and contribute to worse medication-taking behavior (74); cost-reducing strategies may improve medication-taking behavior in some cases (75).

Table 9.3.

Median monthly (30-day) AWP and NADAC of maximum approved daily dose of noninsulin glucose-lowering agents in the U.S.

| Class | Compound(s) | Dosage strength/product (if applicable) | Median AWP (min, max)† | Median NADAC (min, max)† | Maximum approved daily dose* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biguanides | • Metformin | 850 mg (IR) | $106 ($5, $189) | $2 | 2,550 mg |

| 1,000 mg (IR) | $87 ($3, $144) | $2 | 2,000 mg | ||

| 1,000 mg (ER) | $242 ($242, $7,214) | $32 ($32, $160) | 2,000 mg | ||

| Sulfonylureas (2nd generation) | • Glimepiride | 4 mg | $74 ($71, $198) | $3 | 8 mg |

| • Glipizide | 10 mg (IR) | $70 ($67, $91) | $6 | 40 mg | |

| 10 mg (XL/ER) | $48 ($46, $48) | $11 | 20 mg | ||

| • Glyburide | 6 mg (micronized) | $52 ($48, $71) | $12 | 12 mg | |

| 5 mg | $79 ($63, $93) | $9 | 20 mg | ||

| Thiazolidinedione | • Pioglitazone | 45 mg | $345 ($7, $349) | $4 | 45 mg |

| α-Glucosidase inhibitors | • Acarbose | 100 mg | $106 ($104, $106) | $29 | 300 mg |

| • Miglitol | 100 mg | $241 ($241, $346) | NA | 300 mg | |

| Meglitinides | • Nateglinide | 120 mg | $155 | $27 | 360 mg |

| • Repaglinide | 2 mg | $878 ($58, $897) | $31 | 16 mg | |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | • Alogliptin | 25 mg | $234 | $154 | 25 mg |

| • Saxagliptin | 5 mg | $565 | $452 | 5 mg | |

| • Linagliptin | 5 mg | $606 | $485 | 5 mg | |

| • Sitagliptin | 100 mg | $626 | $500 | 100 mg | |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | • Ertugliflozin | 15 mg | $390 | $312 | 15 mg |

| • Dapagliflozin | 10 mg | $659 | $527 | 10 mg | |

| • Canagliflozin | 300 mg | $684 | $548 | 300 mg | |

| • Empagliflozin | 25 mg | $685 | $547 | 25 mg | |

| GLP-1 RAs | • Exenatide (extended release) | 2 mg powder for suspension or pen | $936 | $726 | 2 mg** |

| • Exenatide | 10 μg pen | $961 | $770 | 20 μg | |

| • Dulaglutide | 4.5 mg mL pen | $1,064 | $852 | 4.5 mg** | |

| • Semaglutide | 1 mg pen | $1,070 | $858 | 2 mg** | |

| 14 mg (tablet) | $1,070 | $858 | 14 mg | ||

| • Liraglutide | 1.8 mg pen | $1,278 | $1,022 | 1.8 mg | |

| • Lixisenatide | 20 μg pen | $814 | NA | 20 μg | |

| GLP-1/GIP dual agonist | • Tirzepatide | 15 mg pen | $1,169 | $935 | 15 mg** |

| Bile acid sequestrant | • Colesevelam | 625 mg tabs | $711 ($674, $712) | $83 | 3.75 g |

| 3.75 g suspension | $674 ($673, $675) | $177 | 3.75 g | ||

| Dopamine-2 agonist | • Bromocriptine | 0.8 mg | $1,118 | $899 | 4.8 mg |

| Amylin mimetic | • Pramlintide | 120 μg pen | $2,783 | NA | 120 μg/injection†† |

AWP, average wholesale price; DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase 4; ER and XL, extended release; GIP, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; IR, immediate release; max, maximum; min, minimum; NA, data not available; NADAC, National Average Drug Acquisition Cost; SGLT2, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2.

Calculated for 30-day supply (AWP [72] or NADAC [73] unit price × number of doses required to provide maximum approved daily dose × 30 days); median AWP or NADAC listed alone when only one product and/or price.

Utilized to calculate median AWP and NADAC (min, max); generic prices used, if available commercially.

Administered once weekly.

AWP and NADAC calculated based on 120 μg three times daily.

Cardiovascular Outcomes Trials

There are now multiple large randomized controlled trials reporting statistically significant reductions in cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes treated with an SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 RA; see Section 10, “Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management” for details. Participants enrolled in many of the cardiovascular outcomes trials had A1C ≥6.5%, with more than 70% taking metformin at baseline, with analyses indicating benefit with or without metformin (45). Thus, a practical extension of these results to clinical practice is to use these medications preferentially in people with type 2 diabetes and established ASCVD or indicators of high ASCVD risk. For these individuals, incorporating one of the SGLT2 inhibitors and/or GLP-1 RAs that have been demonstrated to have cardiovascular disease benefit is recommended (see Fig. 9.3, Table 9.2, and Section 10, “Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management”). Emerging data suggest that use of both classes of drugs will provide additional cardiovascular and kidney outcomes benefit; thus, combination therapy with an SGLT2 inhibitor and a GLP-1 RA may be considered to provide the complementary outcomes benefits associated with these classes of medication (76). In cardiovascular outcomes trials, empagliflozin, canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, liraglutide, semaglutide, and dulaglutide all had beneficial effects on indices of CKD, while dedicated renal outcomes studies have demonstrated benefit of specific SGLT2 inhibitors. See Section 11, “Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management,” for discussion of how CKD may impact treatment choices. Additional large randomized trials of other agents in these classes are ongoing.

Insulin Therapy

Many adults with type 2 diabetes eventually require and benefit from insulin therapy (Fig. 9.4). See the section insulin injection technique, above, for guidance on how to administer insulin safely and effectively. The progressive nature of type 2 diabetes should be regularly and objectively explained to patients, and clinicians should avoid using insulin as a threat or describing it as a sign of personal failure or punishment. Rather, the utility and importance of insulin to maintain glycemic control once progression of the disease overcomes the effect of other agents should be emphasized. Educating and involving patients in insulin management is beneficial. For example, instruction of individuals with type 2 diabetes initiating insulin in self-titration of insulin doses based on glucose monitoring improves glycemic control (77). Comprehensive education regarding blood glucose monitoring, nutrition, and the avoidance and appropriate treatment of hypoglycemia are critically important in any individual using insulin.

Basal Insulin

Basal insulin alone is the most convenient initial insulin treatment and can be added to metformin and other noninsulin injectables. Starting doses can be estimated based on body weight (0.1–0.2 units/kg/day) and the degree of hyperglycemia, with individualized titration over days to weeks as needed. The principal action of basal insulin is to restrain hepatic glucose production and limit hyperglycemia overnight and between meals (78,79). Control of fasting glucose can be achieved with human NPH insulin or a long-acting insulin analog. In clinical trials, long-acting basal analogs (U-100 glargine or detemir) have been demonstrated to reduce the risk of symptomatic and nocturnal hypoglycemia compared with NPH insulin (80–85), although these advantages are modest and may not persist (86). Longer-acting basal analogs (U-300 glargine or degludec) may convey a lower hypoglycemia risk compared with U-100 glargine when used in combination with oral agents (87–93). Clinicians should be aware of the potential for overbasalization with insulin therapy. Clinical signals that may prompt evaluation of overbasalization include basal dose greater than ∼0.5 units/kg, high bedtime–morning or postpreprandial glucose differential (e.g., bedtime–morning glucose differential ≥50 mg/dL), hypoglycemia (aware or unaware), and high variability. Indication of overbasalization should prompt reevaluation to further individualize therapy (94).

The cost of insulin has been rising steadily over the past two decades, at a pace severalfold that of other medical expenditures (95). This expense contributes significant burden to patients as insulin has become a growing “out-of-pocket” cost for people with diabetes, and direct patient costs contribute to decrease in medication-taking behavior (95). Therefore, consideration of cost is an important component of effective management. For many individuals with type 2 diabetes (e.g., individuals with relaxed A1C goals, low rates of hypoglycemia, and prominent insulin resistance, as well as those with cost concerns), human insulin (NPH and regular) may be the appropriate choice of therapy, and clinicians should be familiar with its use (96). Human regular insulin, NPH, and 70/30 NPH/regular products can be purchased for considerably less than the AWP and NADAC prices listed in Table 9.4 at select pharmacies. Additionally, approval of follow-on biologics for insulin glargine, the first interchangeable insulin glargine product, and generic versions of analog insulins may expand cost-effective options.

Table 9.4.

Median cost of insulin products in the U.S. calculated as AWP (72) and NADAC (73) per 1,000 units of specified dosage form/product

| Insulins | Compounds | Dosage form/product | Median AWP (min, max)* | Median NADAC* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid-acting | • Lispro follow-on product | U-100 vial | $118 ($118, $157) | $94 |

| U-100 prefilled pen | $151 | $121 | ||

| • Lispro | U-100 vial | $99† | $79† | |

| U-100 cartridge | $408 | $326 | ||

| U-100 prefilled pen | $127† | $102† | ||

| U-200 prefilled pen | $424 | $339 | ||

| • Lispro-aabc | U-100 vial | $330 | $261 | |

| U-100 prefilled pen | $424 | $339 | ||

| U-200 prefilled pen | $424 | NA | ||

| • Glulisine | U-100 vial | $341 | $272 | |

| U-100 prefilled pen | $439 | $351 | ||

| • Aspart | U-100 vial | $174† | $140† | |

| U-100 cartridge | $215† | $172† | ||

| U-100 prefilled pen | $224† | $180† | ||

| • Aspart (“faster acting product”) | U-100 vial | $347 | $277 | |

| U-100 cartridge | $430 | $344 | ||

| U-100 prefilled pen | $447 | $357 | ||

| • Inhaled insulin | Inhalation cartridges | $1,418 | NA | |

| Short-acting | • Human regular | U-100 vial | $165†† | $132†† |

| U-100 prefilled pen | $208 | $166 | ||

| Intermediate-acting | • Human NPH | U-100 vial | $165†† | $132†† |

| U-100 prefilled pen | $208 | $168 | ||

| Concentrated human regular insulin | • U-500 human regular insulin | U-500 vial | $178 | $142 |

| U-500 prefilled pen | $230 | $184 | ||

| Long-acting | • Glargine follow-on products | U-100 prefilled pen | $261 ($118, $323) | $209 ($209, $258) |

| U-100 vial | $118 ($118, $323) | $95 | ||

| • Glargine | U-100 vial; U-100 prefilled pen | $136† | $109† | |

| U-300 prefilled pen | $346 | $277 | ||

| • Detemir | U-100 vial; U-100 prefilled pen | $370 | $296 | |

| • Degludec | U-100 vial; U-100 prefilled pen; U-200 prefilled pen | $407 | $326 | |

| Premixed insulin products | • NPH/regular 70/30 | U-100 vial | $165†† | $133†† |

| U-100 prefilled pen | $208 | $167 | ||

| • Lispro 50/50 | U-100 vial | $342 | $274 | |

| U-100 prefilled pen | $424 | $339 | ||

| • Lispro 75/25 | U-100 vial | $342 | $273 | |

| U-100 prefilled pen | $127† | $103† | ||

| • Aspart 70/30 | U-100 vial | $180† | $146† | |

| U-100 prefilled pen | $224† | $178† | ||

| Premixed insulin/GLP-1 RA products | • Glargine/Lixisenatide | 100/33 μg prefilled pen | $646 | $517 |

| • Degludec/Liraglutide | 100/3.6 μg prefilled pen | $944 | $760 |

AWP, average wholesale price; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; NA, data not available; NADAC, National Average Drug Acquisition Cost.

AWP or NADAC calculated as in Table 9.3.

Generic prices used when available.

AWP and NADAC data presented do not include vials of regular human insulin and NPH available at Walmart for approximately $25/vial; median listed alone when only one product and/or price.

Prandial Insulin

Many individuals with type 2 diabetes require doses of insulin before meals, in addition to basal insulin, to reach glycemic targets. If the individual is not already being treated with a GLP-1 RA, a GLP-1 RA (either in free combination or fixed-ratio combination) should be considered prior to prandial insulin to further address prandial control and to minimize the risks of hypoglycemia and weight gain associated with insulin therapy (45). For individuals who advance to prandial insulin, a prandial insulin dose of 4 units or 10% of the amount of basal insulin at the largest meal or the meal with the greatest postprandial excursion is a safe estimate for initiating therapy. The prandial insulin regimen can then be intensified based on individual needs (Fig. 9.4). Individuals with type 2 diabetes are generally more insulin resistant than those with type 1 diabetes, require higher daily doses (∼1 unit/kg), and have lower rates of hypoglycemia (97). Titration can be based on home glucose monitoring or A1C. With significant additions to the prandial insulin dose, particularly with the evening meal, consideration should be given to decreasing basal insulin. Meta-analyses of trials comparing rapid-acting insulin analogs with human regular insulin in type 2 diabetes have not reported important differences in A1C or hypoglycemia (98,99).

Concentrated Insulins

Several concentrated insulin preparations are currently available. U-500 regular insulin is, by definition, five times more concentrated than U-100 regular insulin. U-500 regular insulin has distinct pharmacokinetics with delayed onset and longer duration of action, has characteristics more like an intermediate-acting (NPH) insulin, and can be used as two or three daily injections (100). U-300 glargine and U-200 degludec are three and two times as concentrated as their U-100 formulations, respectively, and allow higher doses of basal insulin administration per volume used. U-300 glargine has a longer duration of action than U-100 glargine but modestly lower efficacy per unit administered (101,102). The FDA has also approved a concentrated formulation of rapid-acting insulin lispro, U-200 (200 units/mL), and insulin lispro-aabc (U-200). These concentrated preparations may be more convenient and comfortable for individuals to inject and may improve treatment plan engagement in those with insulin resistance who require large doses of insulin. While U-500 regular insulin is available in both prefilled pens and vials, other concentrated insulins are available only in prefilled pens to minimize the risk of dosing errors.

Alternative Insulin Routes

Insulins with different routes of administration (inhaled, bolus-only insulin delivery patch pump) are also available (45). Inhaled insulin is available as a rapid-acting insulin; studies in individuals with type 1 diabetes suggest rapid pharmacokinetics (8). Studies comparing inhaled insulin with injectable insulin have demonstrated its faster onset and shorter duration compared with rapid-acting insulin lispro as well as clinically meaningful A1C reductions and weight reductions compared with insulin aspart over 24 weeks (103–105). Use of inhaled insulin may result in a decline in lung function (reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1]). Inhaled insulin is contraindicated in individuals with chronic lung disease, such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and is not recommended in individuals who smoke or who recently stopped smoking. All individuals require spirometry (FEV1) testing to identify potential lung disease prior to and after starting inhaled insulin therapy.

Combination Injectable Therapy

If basal insulin has been titrated to an acceptable fasting blood glucose level (or if the dose is >0.5 units/kg/day with indications of need for other therapy) and A1C remains above target, consider advancing to combination injectable therapy (Fig. 9.4). This approach can use a GLP-1 RA or dual GIP and GLP-1 RA added to basal insulin or multiple doses of insulin. The combination of basal insulin and GLP-1 RA has potent glucose-lowering actions and less weight gain and hypoglycemia compared with intensified insulin regimens (106–111). The DUAL VIII (Durability of Insulin Degludec Plus Liraglutide Versus Insulin Glargine U100 as Initial Injectable Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes) randomized controlled trial demonstrated greater durability of glycemic treatment effect with the combination GLP-1 RA–insulin therapy compared with addition of basal insulin alone (57). In select individuals, complex insulin regimens can also be simplified with combination GLP-1 RA–insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes (112). Two different once-daily, fixed dual combination products containing basal insulin plus a GLP-1 RA are available: insulin glargine plus lixisenatide (iGlarLixi) and insulin degludec plus liraglutide (IDegLira).

Intensification of insulin treatment can be done by adding doses of prandial insulin to basal insulin. Starting with a single prandial dose with the largest meal of the day is simple and effective, and it can be advanced to a regimen with multiple prandial doses if necessary (113). Alternatively, in an individual on basal insulin in whom additional prandial coverage is desired, the regimen can be converted to two doses of a premixed insulin. Each approach has advantages and disadvantages. For example, basal-prandial regimens offer greater flexibility for individuals who eat on irregular schedules. On the other hand, two doses of premixed insulin is a simple, convenient means of spreading insulin across the day. Moreover, human insulins, separately, self-mixed, or as premixed NPH/regular (70/30) formulations, are less costly alternatives to insulin analogs. Figure 9.4 outlines these options as well as recommendations for further intensification, if needed, to achieve glycemic goals. When initiating combination injectable therapy, metformin therapy should be maintained, while sulfonylureas and DPP-4 inhibitors are typically weaned or discontinued. In individuals with suboptimal blood glucose control, especially those requiring large insulin doses, adjunctive use of a thiazolidinedione or an SGLT2 inhibitor may help to improve control and reduce the amount of insulin needed, though potential side effects should be considered. Once a basal-bolus insulin regimen is initiated, dose titration is important, with adjustments made in both mealtime and basal insulins based on the blood glucose levels and an understanding of the pharmacodynamic profile of each formulation (also known as pattern control or pattern management). As people with type 2 diabetes get older, it may become necessary to simplify complex insulin regimens because of a decline in self-management ability (see Section 13, “Older Adults”).

Footnotes

Disclosure information for each author is available at https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-SDIS.

Suggested citation: ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al., American Diabetes Association. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2023;46(Suppl. 1):S140–S157

References

- 1. Cleary PA, Orchard TJ, Genuth S, et al.; DCCT/EDIC Research Group . The effect of intensive glycemic treatment on coronary artery calcification in type 1 diabetic participants of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) Study. Diabetes 2006;55:3556–3565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JYC, et al.; Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) Study Research Group . Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2643–2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) Study Research Group . Mortality in type 1 diabetes in the DCCT/EDIC versus the general population. Diabetes Care 2016;39:1378–138327411699 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Writing Team for the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group . Effect of intensive therapy on the microvascular complications of type 1 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2002;287:2563–2569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Holt RIG, DeVries JH, Hess-Fischl A, et al. The management of type 1 diabetes in adults. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2021;44:2589–2625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tricco AC, Ashoor HM, Antony J, et al. Safety, effectiveness, and cost effectiveness of long acting versus intermediate acting insulin for patients with type 1 diabetes: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2014;349:g5459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bartley PC, Bogoev M, Larsen J, Philotheou A. Long-term efficacy and safety of insulin detemir compared to neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes using a treat-to-target basal-bolus regimen with insulin aspart at meals: a 2-year, randomized, controlled trial. Diabet Med 2008;25:442–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DeWitt DE, Hirsch IB. Outpatient insulin therapy in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: scientific review. JAMA 2003;289:2254–2264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bode BW, McGill JB, Lorber DL, Gross JL, Chang PC; Affinity 1 Study Group . Inhaled technosphere insulin compared with injected prandial insulin in type 1 diabetes: a randomized 24-week trial. Diabetes Care 2015;38:2266–2273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Russell-Jones D, Bode BW, De Block C, et al. Fast-acting insulin aspart improves glycemic control in basal-bolus treatment for type 1 diabetes: results of a 26-week multicenter, active-controlled, treat-to-target, randomized, parallel-group trial (onset 1). Diabetes Care 2017;40:943–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klaff L, Cao D, Dellva MA, et al. Ultra rapid lispro improves postprandial glucose control compared with lispro in patients with type 1 diabetes: Results from the 26-week PRONTO-T1D study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2020;22:1799–1807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blevins T, Zhang Q, Frias JP, Jinnouchi H; PRONTO-T2D Investigators . Randomized double-blind clinical trial comparing ultra rapid lispro with lispro in a basal-bolus regimen in patients with type 2 diabetes: PRONTO-T2D. Diabetes Care 2020;43:2991–2998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lane W, Bailey TS, Gerety G, et al.; Group Information; SWITCH 1 . Effect of insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 on hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes: the SWITCH 1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318:33–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Home PD, Bergenstal RM, Bolli GB, et al. New insulin glargine 300 units/mL versus glargine 100 units/mL in people with type 1 diabetes: a randomized, phase 3a, open-label clinical trial (EDITION 4). Diabetes Care 2015;38:2217–2225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yeh HC, Brown TT, Maruthur N, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of methods of insulin delivery and glucose monitoring for diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:336–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pickup JC. The evidence base for diabetes technology: appropriate and inappropriate meta-analysis. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2013;7:1567–1574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bergenstal RM, Klonoff DC, Garg SK, et al.; ASPIRE In-Home Study Group . Threshold-based insulin-pump interruption for reduction of hypoglycemia. N Engl J Med 2013;369:224–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buckingham BA, Raghinaru D, Cameron F, et al.; In Home Closed Loop Study Group . Predictive low-glucose insulin suspension reduces duration of nocturnal hypoglycemia in children without increasing ketosis. Diabetes Care 2015;38:1197–1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bergenstal RM, Garg S, Weinzimer SA, et al. Safety of a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system in patients with type 1 diabetes. JAMA 2016;316:1407–1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Garg SK, Weinzimer SA, Tamborlane WV, et al. Glucose outcomes with the in-home use of a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system in adolescents and adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2017;19:155–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tauschmann M, Thabit H, Bally L, et al.; APCam11 Consortium . Closed-loop insulin delivery in suboptimally controlled type 1 diabetes: a multicentre, 12-week randomised trial. Lancet 2018;392:1321–1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown SA, Kovatchev BP, Raghinaru D, et al.; iDCL Trial Research Group . Six-month randomized, multicenter trial of closed-loop control in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1707–1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peters AL, Laffel L (Eds.). American Diabetes Association/JDRF Type 1 Diabetes Sourcebook. Alexandria, VA, American Diabetes Association, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chiang JL, Kirkman MS, Laffel LMB; Type 1 Diabetes Sourcebook Authors . Type 1 diabetes through the life span: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2014;37:2034–2054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bell KJ, Barclay AW, Petocz P, Colagiuri S, Brand-Miller JC. Efficacy of carbohydrate counting in type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vaz EC, Porfírio GJM, Nunes HRC, Nunes-Nogueira VDS. Effectiveness and safety of carbohydrate counting in the management of adult patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Endocrinol Metab 2018;62:337–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bell KJ, Smart CE, Steil GM, Brand-Miller JC, King B, Wolpert HA. Impact of fat, protein, and glycemic index on postprandial glucose control in type 1 diabetes: implications for intensive diabetes management in the continuous glucose monitoring era. Diabetes Care 2015;38:1008–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Frid AH, Kreugel G, Grassi G, et al. New insulin delivery recommendations. Mayo Clin Proc 2016;91:1231–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bergenstal RM, Strock ES, Peremislov D, Gibney MA, Parvu V, Hirsch LJ. Safety and efficacy of insulin therapy delivered via a 4mm pen needle in obese patients with diabetes. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:329–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Whitehouse F, Kruger DF, Fineman M, et al. A randomized study and open-label extension evaluating the long-term efficacy of pramlintide as an adjunct to insulin therapy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002;25:724–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ratner RE, Want LL, Fineman MS, et al. Adjunctive therapy with the amylin analogue pramlintide leads to a combined improvement in glycemic and weight control in insulin-treated subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2002;4:51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hollander PA, Levy P, Fineman MS, et al. Pramlintide as an adjunct to insulin therapy improves long-term glycemic and weight control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 1-year randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2003;26:784–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ratner RE, Dickey R, Fineman M, et al. Amylin replacement with pramlintide as an adjunct to insulin therapy improves long-term glycaemic and weight control in type 1 diabetes mellitus: a 1-year, randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med 2004;21:1204–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meng H, Zhang A, Liang Y, Hao J, Zhang X, Lu J. Effect of metformin on glycaemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2018;34:e2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Petrie JR, Chaturvedi N, Ford I, et al.; REMOVAL Study Group . Cardiovascular and metabolic effects of metformin in patients with type 1 diabetes (REMOVAL): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:597–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mathieu C, Zinman B, Hemmingsson JU, et al.; ADJUNCT ONE Investigators . Efficacy and safety of liraglutide added to insulin treatment in type 1 diabetes: the ADJUNCT ONE treat-to-target randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2016;39:1702–1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ahrén B, Hirsch IB, Pieber TR, et al.; ADJUNCT TWO Investigators . Efficacy and safety of liraglutide added to capped insulin treatment in subjects with type 1 diabetes: the ADJUNCT TWO randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2016;39:1693–1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dandona P, Mathieu C, Phillip M, et al.; DEPICT-1 Investigators . Efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin in patients with inadequately controlled type 1 diabetes (DEPICT-1): 24 week results from a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:864–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rosenstock J, Marquard J, Laffel LM, et al. Empagliflozin as adjunctive to insulin therapy in type 1 diabetes: the EASE trials. Diabetes Care 2018;41:2560–2569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Snaith JR, Holmes-Walker DJ, Greenfield JR. Reducing type 1 diabetes mortality: role for adjunctive therapies? Trends Endocrinol Metab 2020;31:150–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Danne T, Garg S, Peters AL, et al. International consensus on risk management of diabetic ketoacidosis in patients with type 1 diabetes treated with sodium-glucose cotransporter (SGLT) inhibitors. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1147–1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dean PG, Kukla A, Stegall MD, Kudva YC. Pancreas transplantation. BMJ 2017;357:j1321. Accessed 18 October 2022. Available from https://www.bmj.com/content/357/bmj.j1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669–2701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, et al. 2019 Update to: management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2020;43:487–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2022;45:2753–2786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lingvay I, Sumithran P, Cohen RV, le Roux CW. Obesity management as a primary treatment goal for type 2 diabetes: time to reframe the conversation. Lancet 2022;399:394–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HAW. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1577–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Maruthur NM, Tseng E, Hutfless S, et al. Diabetes medications as monotherapy or metformin-based combination therapy for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:740–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. U.S. Food and Drug Administration . FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises warnings regarding use of the diabetes medicine metformin in certain patients with reduced kidney function. Accessed 18 October 2022. Available from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-revises-warnings-regarding-use-diabetes-medicine-metformin-certain

- 50. Out M, Kooy A, Lehert P, Schalkwijk CA, Stehouwer CDA. Long-term treatment with metformin in type 2 diabetes and methylmalonic acid: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled 4.3-year trial. J Diabetes Complications 2018;32:171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Aroda VR, Edelstein SL, Goldberg RB, et al.; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group . Long-term metformin use and vitamin B12 deficiency in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101:1754–1761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Henry RR, Murray AV, Marmolejo MH, Hennicken D, Ptaszynska A, List JF. Dapagliflozin, metformin XR, or both: initial pharmacotherapy for type 2 diabetes, a randomised controlled trial. Int J Clin Pract 2012;66:446–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Babu A, Mehta A, Guerrero P, et al. Safe and simple emergency department discharge therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and severe hyperglycemia. Endocr Pract 2009;15:696–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cahn A, Cefalu WT. Clinical considerations for use of initial combination therapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016;39(Suppl. 2):S137–S145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Abdul-Ghani MA, Puckett C, Triplitt C, et al. Initial combination therapy with metformin, pioglitazone and exenatide is more effective than sequential add-on therapy in subjects with new-onset diabetes. Results from the Efficacy and Durability of Initial Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes (EDICT): a randomized trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015;17:268–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Phung OJ, Sobieraj DM, Engel SS, Rajpathak SN. Early combination therapy for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014;16:410–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Aroda VR, González-Galvez G, Grøn R, et al. Durability of insulin degludec plus liraglutide versus insulin glargine U100 as initial injectable therapy in type 2 diabetes (DUAL VIII): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3b, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019;7:596–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Matthews DR, Paldánius PM, Proot P, Chiang Y, Stumvoll M; VERIFY study group . Glycaemic durability of an early combination therapy with vildagliptin and metformin versus sequential metformin monotherapy in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes (VERIFY): a 5-year, multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 2019;394:1519–1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bennett WL, Maruthur NM, Singh S, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of medications for type 2 diabetes: an update including new drugs and 2-drug combinations. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:602–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Maloney A, Rosenstock J, Fonseca V. A model-based meta-analysis of 24 antihyperglycemic drugs for type 2 diabetes: comparison of treatment effects at therapeutic doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2019;105:1213–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vijan S, Sussman JB, Yudkin JS, Hayward RA. Effect of patients’ risks and preferences on health gains with plasma glucose level lowering in type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1227–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tsapas A, Avgerinos I, Karagiannis T, et al. Comparative effectiveness of glucose-lowering drugs for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:278–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pratley R, Amod A, Hoff ST, et al.; PIONEER 4 investigators . Oral semaglutide versus subcutaneous liraglutide and placebo in type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 4): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3a trial. Lancet 2019;394:39–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Singh S, Wright EE Jr, Kwan AYM, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists compared with basal insulins for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017;19:228–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Levin PA, Nguyen H, Wittbrodt ET, Kim SC. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: a systematic review of comparative effectiveness research. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2017;10:123–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Abd El Aziz MS, Kahle M, Meier JJ, Nauck MA. A meta-analysis comparing clinical effects of short- or long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists versus insulin treatment from head-to-head studies in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017;19:216–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Giorgino F, Benroubi M, Sun JH, Zimmermann AG, Pechtner V. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly dulaglutide versus insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes on metformin and glimepiride (AWARD-2). Diabetes Care 2015;38:2241–2249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Aroda VR, Bain SC, Cariou B, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide versus once-daily insulin glargine as add-on to metformin (with or without sulfonylureas) in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 4): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, multinational, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:355–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Davies M, Heller S, Sreenan S, et al. Once-weekly exenatide versus once- or twice-daily insulin detemir: randomized, open-label, clinical trial of efficacy and safety in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin alone or in combination with sulfonylureas. Diabetes Care 2013;36:1368–1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Diamant M, Van Gaal L, Stranks S, et al. Once weekly exenatide compared with insulin glargine titrated to target in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-3): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2010;375:2234–2243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]