Abstract

Background

Financial relationships between healthcare professionals and pharmaceutical companies have historically caused conflicts of interest and unduly influenced patient care. However, little was known about such relationship and its effect in clinical practice among specialists in respiratory medicine.

Methods

Based on the retrospective analysis of payment data made available by all 92 pharmaceutical companies in Japan, this study evaluated the magnitude and trend of financial relationships between all board-certified Japanese respiratory specialists and pharmaceutical companies between 2016 and 2019. Magnitude and prevalence of payments for specialists were analyzed descriptively. The payment trends were assessed using the generalized estimating equations for the payment per specialist and the number of specialists with payments.

Results

Among all 7,114 respiratory specialists certified as of August 2021, 4,413 (62.0%) received a total of USD 53,547,391 and 74,195 counts from 72 (78.3%) pharmaceutical companies between 2016 and 2019. The median (interquartile range) 4-year combined payment values per specialist were USD 2,210 (USD 715–8,178). At maximum, one specialist received USD 495,332 personal payments over the 4 years. Both payments per specialist and number of specialists with payments significantly increased during the 4-year period, with 7.8% (95% CI: 5.5–9.8; p < 0.001) in payments and 1.5% (95% CI: 0.61–2.4; p = 0.001) in number of specialists with payments, respectively.

Conclusion

The majority of respiratory specialists had increasingly received more personal payments from pharmaceutical companies for the reimbursement of lecturing, consulting, and writing between 2016 and 2019. These increasing financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies might cause conflicts of interest among respiratory physicians.

Keywords: Conflict of interest, Ethics, Health policy, Industry payment, Japan, Japanese respiratory society, Physician payment, Respiratory specialist

Introduction

Financial relationships between healthcare professionals and pharmaceutical companies might cause financial conflicts of interest (COIs) and jeopardize patient-centered care. Indeed, financial relationships between healthcare sectors and pharmaceutical companies might unintentionally influence physician prescribing patterns [1, 2, 3, 4], recommendations of clinical guidelines [5, 6, 7, 8, 9], and conduction of clinical research [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Therefore, proper management of COIs is currently one of the most fundamental challenges for all healthcare professionals [15]. To increase transparency in financial COIs in healthcare, Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (JPMA), the largest pharmaceutical trade organization in Japan, mandate all member companies to publish all payments made to physicians, including those for lecturing, writing, and consulting, itemizing the value of payments along with individuals' names and affiliations on each company webpage from 2013 onward, similar to the US Sunshine Act [16].

Among various specialties, respiratory medicine is one of the increasing markets for pharmaceutical companies alongside improvements in diagnostic technology and an increase in patients with respiratory diseases such as asthma. The market size for respiratory medications is forecasted to increase from 38,985 million USD in 2019 to 57,097 million USD in 2026 worldwide and from 2,519 million USD in 2019 to 3,160 million USD in 2026 in Japan [17]. Furthermore, lung cancer is one of the most common cancer types in Japan, with 125,636 patients (12.8% of all cancer patients) in 2018, ranking third out of 25 cancer types, and 75,394 annual deaths, ranking first out of 25 cancer types in 2019 [18]. The launch of mainly novel drugs for lung cancer contributed to the treatment of lung cancer and fierce market competition in Japan [17]. Consequently, the payments from pharmaceutical companies are expected to be increasingly concentrated on respiratory specialists in Japan, as did in other specialties such as hematology [19]. However, no studies have assessed the magnitude and trends in payments from pharmaceutical companies to respiratory specialists in Japan. This study aimed to elucidate the number of board-certified respiratory specialists receiving payments from pharmaceutical companies, the magnitude, and trends in the payments throughout recent years.

Methods

Participants

This retrospective study considered all of the respiratory specialists certified by the Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS) as of August 12, 2021. The name list of specialists in the previous years was not publicly available from the JRS. Thus, we used the latest version of the name list issued in August 2021 for this study. The JRS was established in 1961 and is the primary and the largest medical professional society in respiratory medicine in Japan, with 12,976 JRS members as of January 2021. The JRS contributed to training, certifying the physicians specializing in respiratory medicine in Japan, with the latest name list of the specialists publicly disclosed on the Society webpage. To become a board-certified respiratory specialist, physicians need to complete several requirements (online suppl. Material 1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000526576). The JRS also contributes to the development of clinical practice guidelines for respiratory diseases, promoting research and continuing medical education (CME) in respiratory medicine, and publishing several academic journals such as the Respiratory Investigation and Respirology in English and the Annals of the Japanese Respiratory Society in Japanese.

Data Collection

First, the name, affiliations, certifications in teaching respiratory medicine that trains respiratory physicians, and addresses of all respiratory specialists were collected from the webpage of the JRS (https://www.jrs.or.jp/modules/senmoni/) on November 6, 2021. The webpage of the specialist name list was last updated on August 12, 2021, at the time of our data collection. The payment data of JRS-certified respiratory specialists were extracted from all 92 pharmaceutical companies affiliated with the JPMA and other associated companies from 2016 to 2019 (online suppl. Material 2) [19, 20, 21]. The extracted data included recipients' names and affiliations, monetary amounts payment counts, payment categories, and pharmaceutical companies' names. To remove payment data of different persons with similar names, we compared affiliations and recipients' specialties between the data from the Society and the pharmaceutical companies. For payments to specialists whose affiliation and specialty reported by pharmaceutical companies differed from those reported by the JRS, we manually searched the name of respiratory specialists and collected additional data from official institutional web pages to verify whether they were the same persons, as we previously noted [19, 20, 21].

According to the JPMA transparency guideline [22], only the payments concerning lecturing, writing, and consulting were disclosed along with individuals' names and affiliations and analyzed based on individual specialists. The JPMA guideline voluntarily required all member companies to disclose their payments to healthcare professionals. This guideline did not include details regarding the process of the disclosure agreements, but basically, individual consent is obtained for disclosure in advance from physicians to disclose their payments data. Other types of personal payments such as for meals, education, travel, and accommodations were not disclosed individually, but only aggregated monetary value of these payments was disclosed by each company in Japan [16]. Personal payments such as lecturing, writing, and consulting are directly and widely paid to individual physicians by pharmaceutical companies [2, 23, 24]. Furthermore, payment data in 2019 were the latest available analyzable data in Japan. Considering such nature of payments, the personal payments concerning lecturing, writing, and consulting between 2016 and 2019 were included in this study.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses of payment values and the number of payment counts were performed based on the specialists and the pharmaceutical companies. As a few companies such as Shire Japan and Baxalta did not disclose the number of payment counts, the payments from these companies were excluded from the analysis for payment counts. The Gini index and the shares of the payment values held by the top 1%, 5%, 10%, and 25% of specialists were used to examine the payment concentration. The Gini index measures income inequality among a given population, ranging from 0 to 1. The greater Gini index indicates a greater disparity in the distribution of payments on a specialist basis [21, 25, 26, 27]. Subgroup analyses were conducted to elucidate the geographical differences in prefecture and region levels in the payments.

As the distribution of payments was highly right-skewed, the population-averaged generalized estimating equation negative binomial regression model for the trend of payment value per specialist and the linear generalized estimating equation model log linked with binomial distribution for the trend of the number of specialists with payments were used to evaluate payment trends through the 4 years. In addition, the relative percentage of the average annual increase in payments per specialist and the number of specialists with payments were used to report the results. The years of payments and the number of physicians receiving payments and payment values were set as independent variables and dependent variables, respectively [19, 28, 29, 30]. Several companies lacked payment data over the 4 years because the companies were disaffiliated from the JPMA and others newly joined the JPMA. Therefore, we calculated only the payment trends of companies that had complete data for 4 years. A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Japanese yen (¥) was converted into the corresponding USD ($) using the 2019 average monthly exchange rate of JPY 109.0 per USD 1. All analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel, version 16.0 (Microsoft Corp.), and Stata version 15 (StataCorp.).

Ethical Approval

The Ethics Committee of the Medical Governance Research Institute approved this study (approval number: MG2018-04-20200605; approval date: June 5, 2020). As this study was a retrospective analysis of publicly available information from pharmaceutical companies and the Society webpage, informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee.

Results

Overview of Payments

A total of 7,114 respiratory specialists were certified by the JRS as of August 12, 2021, including 3,002 (42.2%) certified teaching respiratory specialists. Our payment database recorded 1,474,653 payment counts worth USD 996,291,009 (JPY 108,595,720,027) from 92 pharmaceutical companies between 2016 and 2019. Of the 7,114 specialists, 4,413 (62.0%) received a total of USD 53,547,391 (JPY 5,836,665,622) and 74,195 payment counts from 72 (78.3%: 72 out of 92) pharmaceutical companies over the same period (Table 1). The payment counts and values to the respiratory specialists occupied 5.0% and 5.4% of total counts and values, respectively. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) and median (interquartile range [IQR]) 4-year combined payment values per specialist were USD 12,134 (SD: USD 34,045) and USD 2,210 (IQR: USD 715–8,178), respectively. At maximum, one specialist received USD 495,332 personal payments over the 4 years. The mean and median number of counts over the 4 years were 16.8 (SD: 34.9) and 5.0 (IQR: 2.0–16.0) counts per specialist. The respiratory specialists received the payments from 4.8 (SD: 4.3; median: 3.0; and IQR: 1.0–7.0) pharmaceutical companies on average. The maximum payment counts and pharmaceutical companies per specialist over the 4 years were 461 payments and 30 companies.

Table 1.

Summary of personal payments from pharmaceutical companies to respiratory specialists certified by the JRS between 2016 and 2019

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Total payments, USD | |

| Payment values, USD | 53,547,391 |

| Counts, n | 74,195 |

| Companies, n | 72 |

|

| |

| Average per specialist ± SD | |

| Payment values, USD | 12,134±34,045 |

| Counts, n | 16.8±34.9 |

| Companies, n | 4.8±4.3 |

|

| |

| Median (IQR) | |

| Payment values, USD | 2,210 (715–8,178) |

| Counts, n | 5.0 (2.0–16.0) |

| Companies, n | 3.0 (1.0–7.0) |

|

| |

| Range | |

| Payment values, USD | 31–495,332 |

| Counts, n | 1.0–461 |

| Companies, n | 1.0–30 |

|

| |

| Physicians with specific payments, n (%) | |

| Any payments | 4,413 (62.0) |

| Payments >USD 500 | 3,747 (52.7) |

| Payments >USD 1,000 | 3,000 (42.2) |

| Payments >USD 5,000 | 1,478 (20.8) |

| Payments >USD 10,000 | 940 (13.2) |

| Payments >USD 50,000 | 239 (3.4) |

| Payments >USD 100,000 | 111 (1.6) |

|

| |

| Gini index | 0.871 |

|

| |

| Category of payments, USD (%) | |

| Lecturing | 45,847,076 (85.6) |

| Consulting | 5,770,483 (10.8) |

| Writing | 1,701,141 (3.2) |

| Other | 228,691 (0.43) |

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

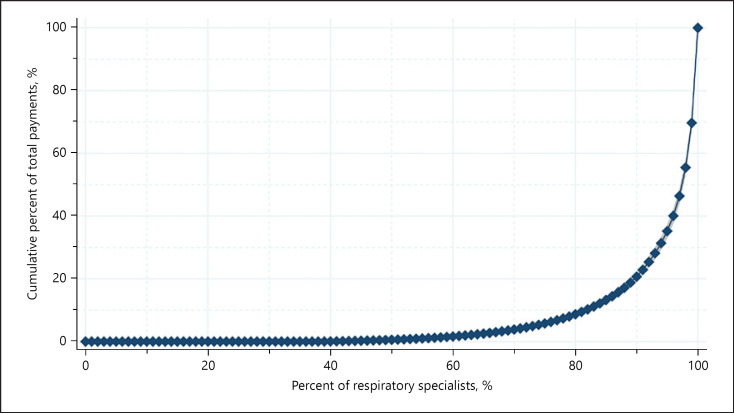

While 38.0% of the specialists had no personal payments, 52.7%, 42.2%, 20.8%, 13.2%, 3.4%, and 1.6% of respiratory specialists received more than USD 500, USD 1,000, USD 5,000, USD 10,000, USD 50,000, and USD 100,000 in the 4-year combined payments, respectively (online suppl. Material 3). The Gini index was 0.871 for the 4-year combined total payments per specialist, indicating that only a small portion of the respiratory specialists received large amount of the personal payments. Top 1%, 5%, 10%, and 25% of specialists occupied 30.3% (95% confidence interval [95% CI]L: 28.2–32.4), 64.8% (95% CI: 62.6–67.0), 79.3% (95% CI: 77.8–80.8), and 94.2% (95% CI: 93.7–94.7) of total monetary values, respectively (Fig. 1). The most common payment category was lecturing, occupying 85.6% of the total (USD 45,847,076). The average and median payments for top 1% respiratory specialists were USD 264,879 (SD: USD 70,965) and USD 247,747 (IQR: USD 209,087‒295,562), respectively. For payment counts per specialist, top 1% specialists received 241.4 (SD: 67.8) counts in average and 234 counts in median (IQR: 195–288) during the 4 years, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Pharmaceutical payment concentration among the respiratory specialists in Japan.

Trends of Payments

The median payments per specialist ranged USD 1,085 (IQR: USD 511‒3,192) in 2016 to USD 1,428 (IQR: USD 520‒4,034) in 2019. The annual change rates marked significant increases in both payments per specialist by 7.6% (95% CI: 5.5–9.8; p < 0.001) and number of specialists with payments by 1.5% (95% CI: 0.61–2.4; p = 0.001) (Table 2). Among 72 companies paying to the specialists, there were six companies making payments to the specialists without 4-year payment data. Therefore, we limited the analysis to the payments from the remaining 66 companies with 4-year data. Significant annual increases in payments and the number of specialists with payments were also observed, with 7.8% (95% CI: 5.6–9.9; p < 0.001) in payments and 1.6% (95% CI: 0.69–2.5; p < 0.001) in the number of respiratory specialists with payments, respectively.

Table 2.

Trend of personal payments from pharmaceutical companies to respiratory specialists certified by the JRS between 2016 and 2019

| Variables | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Average yearly change (95% CI), % | p value | Combined total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All pharmaceutical companies | |||||||

| Total payments, USD (JPY) | 12,439,754 | 12,025,229 | 13,911,371 | 15,171,038 | − | − | 53,547,391 |

| (1,355,933,145) | (1,310,749,925) | (1,516,339,453) | (1,653,643,099) | (5,836,665,622) | |||

| Average payments±SD, USD | 4,270±10,590 | 4,368±10,531 | 4,689±10,492 | 5,081±11,520 | 7.6 (5.5–9.8) | <0.001 | 12,134±34,045 |

| Median payments (IQR), USD | 1,085 (511–3,192) | 1,124 (511–3,325) | 1,328 (511–3,795) | 1,428 (520–4,034) | 2,210 (715–8,178) | ||

| Payment range, USD | 85–138,421 | 51–129,078 | 92–149,569 | 31–117,871 | − | − | 31–495,332 |

| Physicians with specific payments, n (%) | |||||||

| Any payments | 2,913 (40.9) | 2,753 (38.7) | 2,967 (41.7) | 2,986 (42.0) | 1.5 (0.61–2.4) | 0.001 | 4,413 (62.0) |

| Payments >USD 500 | 2,261 (31.8) | 2,174 (30.6) | 2,398 (33.7) | 2,457 (34.5) | 3.6 (2.5–4.6) | <0.001 | 3,747 (52.7) |

| Payments >USD 1,000 | 1,568 (22.0) | 1,490 (20.9) | 1,724 (24.2) | 1,806 (25.4) | 6.0 (4.7–7.3) | <0.001 | 3,000 (42.2) |

| Payments >USD 5,000 | 508 (7.1) | 504 (7.1) | 593 (8.3) | 634 (8.9) | 8.7 (6.3–11.2) | <0.001 | 1,478 (20.8) |

| Payments >USD 10,000 | 261 (3.7) | 269 (3.8) | 311 (4.4) | 331 (4.7) | 9.0 (5.7–12.4) | <0.001 | 940 (13.2) |

| Payments >USD 50,000 | 38 (0.53) | 34 (0.48) | 40 (0.56) | 49 (0.69) | 10.2 (−0.76 to 22.4) | 0.069 | 239 (3.4) |

| Payments >USD 100,000 | 6 (0.084) | 5 (0.070) | 2 (0.028) | 6 (0.084) | −6.1 (−32.5 to 30.5) | 0.71 | 111 (1.6) |

| Gini index | 0.892 | 0.897 | 0.884 | 0.885 | − | − | 0.871 |

|

| |||||||

| Pharmaceutical companies with 4-year payment dataa | |||||||

| Total payments, USD | 12,329,176 | 12,010,489 | 13,846,437 | 15,102,239 | − | − | 53,286,653 |

| (1,343,880,199) | (1,309,143,306) | (1,509,261,613) | (1,645,960,030) | (5,808,245,148) | |||

| Average payments±SD, USD | 4,259±10,517 | 4,367±10,519 | 4,679±10,470 | 5,073±11,490 | 7.8 (5.6–9.9) | <0.001 | 12,113±33,943 |

| Median payments (IQR), USD | 1,093 (511–3,180) | 1,124 (511–3,326) | 1,328 (511–3,780) | 1,420 (520–4,005) | 2,214 (715–8,169) | ||

| Payment range, USD | 85–136,230 | 51–129,078 | 92–149,569 | 31–117,871 | − | − | 31–495,332 |

| Physicians with specific payments, n (%) | |||||||

| Any payments | 2,895 (40.7) | 2,750 (38.7) | 2,959 (41.6) | 2,977 (41.8) | 1.6 (0.69–2.5) | 0.001 | 4,399 (61.8) |

| Payments >USD 500 | 2,248 (31.6) | 2,171 (30.5) | 2,391 (33.6) | 2,452 (34.5) | 3.7 (2.6–4.7) | <0.001 | 3,734 (52.5) |

| Payments >USD 1,000 | 1,562 (22.0) | 1,489 (20.9) | 1,714 (24.1) | 1,803 (25.3) | 6.0 (4.7–7.3) | <0.001 | 2,991 (42.0) |

| Payments >USD 5,000 | 503 (7.1) | 504 (7.1) | 591 (8.3) | 632 (8.9) | 8.9 (6.4–11.4) | <0.001 | 1,472 (20.7) |

| Payments >USD 10,000 | 259 (3.6) | 268 (3.8) | 310 (4.4) | 330 (4.6) | 9.2 (5.9–12.5) | <0.001 | 931 (13.1) |

| Payments >USD 50,000 | 37 (0.52) | 33 (0.46) | 40 (0.56) | 48 (0.67) | 10.7 (−0.36 to 23.0) | 0.058 | 239 (3.4) |

| Payments >USD 100,000 | 6 (0.084) | 5 (0.070) | 2 (0.028) | 6 (0.084) | −6.1 (−32.5 to 30.5) | 0.71 | 110 (1.6) |

| Gini index | 0.892 | 0.897 | 0.884 | 0.885 | − | − | 0.871 |

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

We analyzed the payments from 66 pharmaceutical companies with 4-year data.

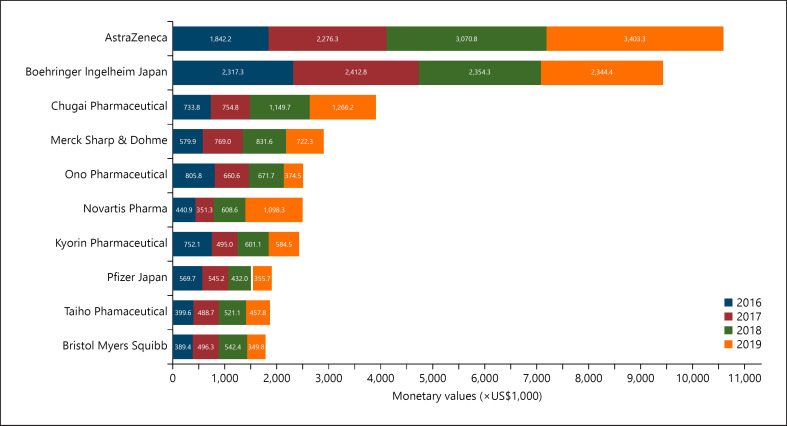

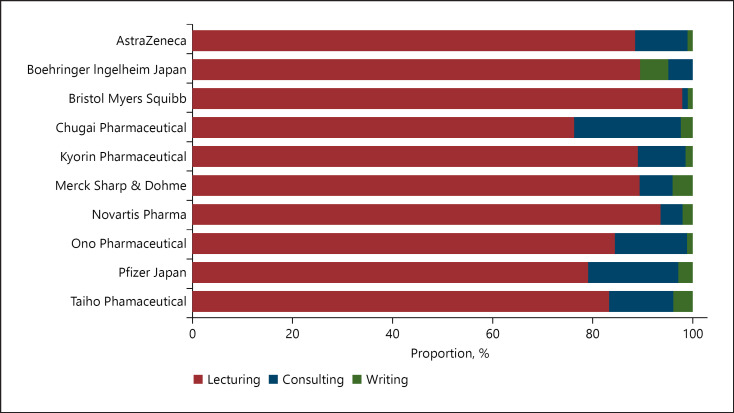

Payments by Company

Among 72 pharmaceutical companies making payments to specialists, payments from the top 10 companies accounted for 74.4% of total payments with USD 39,820,882 between 2016 and 2019 (Fig. 2; online suppl. Material 4). Particularly, the top two companies with the largest amount, AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim, Japan, shared 19.8% (USD 10,592,516) and 17.6% (USD 9,428,840) of the total payments. The payment types by the top 10 paying companies are shown in Figure 3.

Fig. 2.

Total payments to respiratory specialists made by the top 10 largest paying companies between 2016 and 2019.

Fig. 3.

Payment category by the pharmaceutical companies.

Geographical Payment Distribution

There were significant geographical differences in the distribution of respiratory and advising specialists in Japan (online suppl. Material 5A, B). The number of respiratory specialists per million population ranged from 28.6 in Aomori Prefecture to 86.0 in the Tokyo Metropolis based on the prefecture. The total payment values per prefecture are shown in online supplementary Material 5C. The average payment values per specialist were the highest in Miyagi Prefecture (USD 11,855) and the lowest in Oita Prefecture (USD 3,707) (online suppl. Material 5D). For analysis by region, the number of specialists per million population ranged from 43.8 in the Tohoku region (northernmost of Japan) to 64.7 in the Kyusyu region (southernmost of Japan), while the average payments per specialist ranged from USD 6,450 in the Kyusyu region to USD 9,971 in Tohoku region.

Discussion

Based on the published evidence extracted from Medline/PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, this is the first study assessing the magnitude and trends of the financial relationships between respiratory specialists and pharmaceutical companies, which found that 5.4% of total personal payments from all pharmaceutical companies were distributed to respiratory specialists, representing 2.2% (7,114 out of 327,210) of all physicians [31]. Among 7,114 respiratory specialists in Japan, 4,413 (62.0%) accepted USD 53,547,391 personal payments, totaling 74,195 counts from 72 (78.3%) pharmaceutical companies between 2016 and 2019. Furthermore, the respiratory specialists received USD 12,134 personal payments with 16.8 times those for the reimbursement of lecturing, consulting, and writing from 4.8 pharmaceutical companies on average in Japan. These financial interactions significantly increased by 7.8% in payment values per specialist and 1.6% in the number of specialists receiving payments between 2016 and 2019.

First, we should note that there was a dearth of research evaluating financial relationships between pharmaceutical companies and respiratory physicians with a large sample size worldwide. One study by Inoue et al. [32] assessed the financial relationships between physicians and pharmaceutical companies across 32 specialties in the USA and reported that pulmonology specialists received an average of USD 896 in annual general payments such as lecturing, consulting, meals, travel, and accommodations. Comparing with their findings, we observed that the Japanese respiratory specialists received 4.8–5.7 times higher average annual payments of USD 4,270 in 2016 and USD 5,081 in 2019. The discrepancy could have been caused by differences in payment categories and those in definition of respiratory specialists between their study in the USA and our study in Japan. Nevertheless, our findings indicated strong financial relationships between respiratory physicians and pharmaceutical companies in Japan. A literature review of previous studies was summarized in online supplementary Material 6. Particularly, this study represented large financial relationships of JRS-certified specialists with pharmaceutical companies as compared to other specialists in the USA and Japan.

One of the primary findings of this study was that both the magnitude and fraction of payments for respiratory specialists in Japan increased significantly during the past 4 years, with a 7.8% average annual increase in payments per specialist and 1.6% in the number of specialists with payments. This finding was consistent with previous studies conducted among US oncologists [30] and Japanese hematologists. Although Marshall et al. [28] reported that overall payment values and the number of physicians receiving payments declined since the introduction of the US Open Payments Database, greater payments were increasingly concentrated on a smaller proportion of the US oncologists [30]. Furthermore, Kusumi et al. [19] reported that both payments and the number of hematologists with payments constantly increased with a significant average annual increase of 10.4% and 2.9%, respectively. As Ozaki et al. [20] previously reported, the Japanese respiratory oncologists received the highest personal payments in 2016 due to the launch of the multiple novel oncology drugs for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Among the top 10 largest paying companies, in particular, the total annual payments from AstraZeneca, the largest paying company, constantly increased from USD 1,842,153 in 2016 to USD 3,403,281 in 2019. Meanwhile, Boehringer Ingelheim, the second-largest paying company, remained stable, ranging from USD 2,317,265 in 2016 to USD 2,412,839 in 2017. This increasing trend would also be due to the invention of several novel drugs for lung cancers. For example, osimertinib (TAGRISSO® from AstraZeneca) was approved for stage III NSCLC in March 2016, and then it was strongly recommended as a first-line treatment for stage III NSCLC in Japan in 2018 [33]. Consequently, USD 751 million worth of osimertinib was sold in 2019, accounting for the largest share of all oral molecular targeted drugs in Japan [34]. Also, durvalumab (IMFINZI® from AstraZeneca) received its first approval as an immune checkpoint inhibitor for NSCLC in Japan in July 2018 [33].

Aside from lung cancer drugs, there have been remarkable changes in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treatment. Current clinical guidelines such as the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guideline and the JRS guideline recommended dual therapy with the long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) and long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) or inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and LABA over monotherapy of each drug [35, 36]. Following these changes in guideline recommendations, several companies such as Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline developed combination drugs of LAMA/LABA, ICS/LABA, and further, ICS/LAMA/LABA [34]. Furthermore, novel biological drugs for asthma treatment have been increasingly developed, such as omalizumab (XOLAIR® from Novartis Pharma, approved for asthma in 2009); mepolizumab (NUCALA® from GlaxoSmithKline, approved for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 2016); benralizumab (FASENRA® from AstraZeneca, approved for asthma in 2018); and dupilumab (DUPIXENT® from Sanofi, approved for asthma in 2019) [34]. Considering the recent development of novel drugs in respiratory medicine, the personal payments from pharmaceutical companies to respiratory specialists are expected to increase in Japan in the future.

Increasing evidence outside of Japan suggests that only small amounts of payments from pharmaceutical companies would influence physicians' drug prescription [1, 4, 37, 38, 39] as well as medical device selection [40]. A recent study, assessing financial COIs and speakers' statements on pulmonary drugs at the US Food and Drug Administration meetings, found that speakers with financial COIs were 4.5 times more likely to give a positive testimony for a drug than those without them, while the presence of speakers with COIs was not associated with the approval of drugs [41]. Another recent systematic review by Mitchell et al. [4] found that financial transactions from industry to physicians, even for small amounts such as meals and beverages, led to more frequent prescriptions of drugs paid for by companies, higher healthcare costs, and a higher proportion of brand-name drugs over generic ones. However, many physicians, especially those receiving larger payments from pharmaceutical companies, believed that the financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies were appropriate, the company-sponsored conferences and educational events were important source for enhancing their scientific knowledge, and their prescribing patterns were not influenced by the payments from pharmaceutical companies [42]. Given the influence of pharmaceutical payments to physicians on patient care, more transparent and rigorous management of the financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies, such as the strategies implemented among clinical practice guideline authors [9, 43, 44], might be required among general physicians not only in respiratory medicine.

Limitations

First, as previously noted, the payment database was structured by the manual collection of payment data from 92 pharmaceutical companies and cross-checked to exclude duplicate physicians from the data. Therefore, this study might have included a few unavoidable human errors, but our repeated and careful scrutiny of payment data by more than two independent reviewers could have minimized such errors. Second, currently, pharmaceutical companies do not disclose their payments to healthcare professionals concerning meals, beverages, accommodations, travel, and stock ownerships. This would have led to significant underestimations of the extent and prevalence of overall financial relationships between respiratory specialists and industries. Third, the payment data disclosed by the companies did not include information on the purpose of the payments and drug and product names which were related to the payments as the JPMA does not mandate to disclose such information. Therefore, this study did not assess the direct associations between the payment amounts and related novel respiratory drugs. Finally, there was no monitoring system for ensuring the accuracy of the payments disclosed by the companies and no penalties for violation of the JPMA transparency guideline. Therefore, the payment data disclosed by the companies might be inaccurate.

Conclusion

The majority of respiratory specialists board-certified by the Japanese Respiratory Society increasingly received personal payments for the reimbursements of lecturing, consulting, and writing from the pharmaceutical companies. These financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies were potential COIs, and the vast majority of these payments concentrated on only a tiny proportion of specialists. Therefore, we believed this study would reach all respiratory medicine stakeholders, including patients, healthcare professionals, and policymakers, and promote discussion for better healthcare with harmony between patients, healthcare professionals, and industries.

Statement of Ethics

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Governance Research Institute (approval number: MG2018-04-20200605; approval date: June 5, 2020). As this study was a retrospective analysis of publicly available information from pharmaceutical companies and the Society webpage, informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee. As this study was a retrospective analysis of publicly available information from pharmaceutical companies and the Japanese Respiratory Society webpage, informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Governance Research Institute.

Conflict of Interest Statement

For financial conflicts of interest, Dr. Kusumi received personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. outside the scope of the submitted work. Dr. Saito received personal fees from TAIHO Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. outside the scope of the submitted work. Drs. Ozaki and Tanimoto received personal fees from Medical Network Systems, a dispensing pharmacy, outside the scope of the submitted work. Dr. Tanimoto also received personal fees from Bionics Co. Ltd., a medical device company, outside the scope of the submitted work. The remaining authors declared no financial conflicts of interest with pharmaceutical companies. Regarding nonfinancial conflicts of interest among the study authors, all are engaged in ongoing research examining financial and nonfinancial conflicts of interest among healthcare professionals and pharmaceutical companies in Japan. Individually, Anju Murayama, Hiroaki Saito, Toyoaki Sawano, Tetsuya Tanimoto, and Akihiko Ozaki contributed to several published studies addressing conflicts of interest and quality of evidence among clinical practice guideline authors in Japan and the USA. The other authors have no example of conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Sources

This study was funded in part by the Medical Governance Research Institute. This nonprofit research organization received donations from a dispensing pharmacy, Ain Pharmacies, other organizations, and private individuals. This study also received support from Tansa, an independent nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative journalism. None of the entities providing financial support for this study contributed to the design, execution, data analyses, interpretation of study findings, and manuscript drafting. There was no award/grant number for the financial support.

Author Contributions

Anju Murayama was the principal investigator and responsible for the data collection, data analysis, and coordination of this study. Anju Murayama: study concept, study design, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing − original draft, visualization, supervision, and project administration. Momoko Hoshi: study concept, study design, methodology, formal analysis, and writing − original draft. Hiroaki Saito: study concept, study design, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing − original draft, and writing − review and editing. Sae Kamamoto: study concept, study design, investigation, resources, writing − original draft, and writing − review and editing. Manato Tanaka, Moe Kawashima, and Hanano Mamada: study concept, study design, investigation, resources, and writing − original draft. Eiji Kusumi and Toyoaki Sawano: study concept, study design, methodology, and writing − review and editing. Binaya Sapkota, Sunil Shrestha, Rajeev Shrestha, and Divya Bhandari: study concept and writing − review and editing. Erika Yamashita: study concept, investigation, resources, and writing − review and editing. Tetsuya Tanimoto: study concept, study design, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing − original draft, writing − review and editing, and supervision. Akihiko Ozaki: study concept, software, formal analysis, investigation, resources, visualization, writing − review and editing, project administration, and funding acquisition.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available on the Japanese Respiratory Society's webpage. All the payment data used in this study are included as online supplementary Material 2. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Tansa (formerly known as Waseda Chronicle) for providing payment data. Also, we appreciate Mr. Souto Nagano, an undergraduate student from the Faculty of Letters, University of Tokyo; Mr. Kohki Yamada, a medical student at the Osaka University School of Medicine; Mr.Takuto Sakaemura, an undergraduate student from Faculty of Applied Science, Simon Fraser University; and Ms. Megumi Aizawa, a graduate student from the Department of Industrial Engineering and Economics, School of Engineering, Tokyo Institute of Technology, for their dedicated contribution on collecting and cross-checking the payment data.

Funding Statement

This study was funded in part by the Medical Governance Research Institute. This nonprofit research organization received donations from a dispensing pharmacy, Ain Pharmacies, other organizations, and private individuals. This study also received support from Tansa, an independent nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative journalism. None of the entities providing financial support for this study contributed to the design, execution, data analyses, interpretation of study findings, and manuscript drafting. There was no award/grant number for the financial support.

References

- 1.DeJong C, Aguilar T, Tseng C-W, Lin GA, Boscardin WJ, Dudley RA. Pharmaceutical industry-sponsored meals and physician prescribing patterns for medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176((8)):1114–1122. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartung DM, Johnston K, Cohen DM, Nguyen T, Deodhar A, Bourdette DN. Industry payments to physician specialists who prescribe repository corticotropin. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1((2)):e180482. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Modi PK, Wang Y, Kirk PS, Dupree JM, Singer EA, Chang SL. The receipt of industry payments is associated with prescribing promoted alpha-blockers and overactive bladder medications. Urology. 2018 Jul;117:50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell AP, Trivedi NU, Gennarelli RL, Chimonas S, Tabatabai SM, Goldberg J, et al. Are financial payments from the pharmaceutical industry associated with physician prescribing? A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2021 Mar;174((3)):353–361. doi: 10.7326/M20-5665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coyne DW. Influence of industry on renal guideline development. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2((1)):3–7. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02170606. discussion 13–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson L, Stricker RB. Attorney General forces Infectious Diseases Society of America to redo Lyme guidelines due to flawed development process. J Med Ethics. 2009 May;35((5)):283–288. doi: 10.1136/jme.2008.026526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nejstgaard CH, Bero L, Hrobjartsson A, Jorgensen AW, Jorgensen KJ, Le M, et al. Association between conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations in clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews: systematic review. BMJ. 2020 Dec 9;371:m4234. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashimoto T, Murayama A, Mamada H, Saito H, Tanimoto T, Ozaki A. Evaluation of financial conflicts of interest and drug statements in the coronavirus disease 2019 clinical practice guideline in Japan. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28((3)):460–462. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murayama A, Ozaki A, Saito H, Sawano T, Tanimoto T. Are clinical practice guideline for hepatitis C by the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease and Infectious Diseases Society of America evidence-based? Financial conflicts of interest and assessment of quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Hepatology. 2022;75((4)):1052–1054. doi: 10.1002/hep.32262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson JM. Lessons learned from the gene therapy trial for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2009 Apr;96((4)):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, Schroll JB, Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb 16;2((2)):MR000033. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozaki A. Conflict of interest and the CREATE-X trial in the New England Journal of Medicine. Sci Eng Ethics. 2018 Dec;24((6)):1809–1811. doi: 10.1007/s11948-017-9966-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawano T, Ozaki A, Saito H, Shimada Y, Tanimoto T. Payments from pharmaceutical companies to authors involved in the valsartan scandal in Japan. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 May 3;2((5)):e193817. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tijdink JK, Smulders YM, Bouter LM, Vinkers CH. The effects of industry funding and positive outcomes in the interpretation of clinical trial results: a randomized trial among Dutch psychiatrists. BMC Med Ethics. 2019 Sep 18;20((1)):64. doi: 10.1186/s12910-019-0405-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ABIM Foundation. ACP-ASIM Foundation. European Federation of Internal Medicine Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Feb 5;136((3)):243–246. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozaki A, Saito H, Senoo Y, Sawano T, Shimada Y, Kobashi Y, et al. Overview and transparency of non-research payments to healthcare organizations and healthcare professionals from pharmaceutical companies in Japan: analysis of payment data in 2016. Health Policy. 2020 Jul;124((7)):727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.QYResearch . QYResearch; 2020. Global and Japan respiratory drug market insights. Forecast to 2026. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuda T, Ajiki W, Marugame T, Ioka A, Tsukuma H, Sobue T, et al. Population-based survival of cancer patients diagnosed between 1993 and 1999 in Japan: a chronological and international comparative study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011 Jan;41((1)):40–51. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kusumi E, Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Kawashima M, Yoshida M, Saito H, et al. Pharmaceutical payments to Japanese certified hematologists: a retrospective analysis of personal payments from pharmaceutical companies between 2016 and 2019. Blood Cancer J. 2022 Apr 7;12((4)):54. doi: 10.1038/s41408-022-00656-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozaki A, Saito H, Onoue Y, Sawano T, Shimada Y, Somekawa Y, et al. Pharmaceutical payments to certified oncology specialists in Japan in 2016: a retrospective observational cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open. 2019 Sep 6;9((9)):e028805. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murayama A, Ozaki A, Saito H, Sawano T, Shimada Y, Yamamoto K, et al. Pharmaceutical company payments to dermatology clinical practice guideline authors in Japan. PLoS One. 2020;15((10)):e0239610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association . 2018. Regarding the transparency guideline for the relation between corporate activities and medical institutions. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng H, Wu P, Leger M. Exploring the industry-dermatologist financial relationship: insight from the open payment data. JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Dec 1;152((12)):1307–1313. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tringale KR, Marshall D, Mackey TK, Connor M, Murphy JD, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. Types and distribution of payments from industry to physicians in 2015. JAMA. 2017 May 2;317((17)):1774–1784. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozieranski P, Csanadi M, Rickard E, Tchilingirian J, Mulinari S. Analysis of pharmaceutical industry payments to UK Health Care Organizations in 2015. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Jun 5;2((6)):e196253. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nalleballe K, Sheng S, Li C, Mahashabde R, Annapureddy AR, Mudassar K, et al. Industry payment to vascular neurologists: a 6-year analysis of the open payments program from 2013 through 2018. Stroke. 2020 Apr;51((4)):1339–1343. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.027967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto K, Murayama A, Ozaki A, Saito H, Sawano T, Tanimoto T. Financial conflicts of interest between pharmaceutical companies and the authors of urology clinical practice guidelines in Japan. Int Urogynecol J. 2021 Feb;32((2)):443–451. doi: 10.1007/s00192-020-04547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall DC, Tarras ES, Rosenzweig K, Korenstein D, Chimonas S. Trends in industry payments to physicians in the United States from 2014 to 2018. JAMA. 2020 Nov 3;324((17)):1785–1788. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall DC, Tarras ES, Rosenzweig K, Yom SS, Hattangadi-Gluth J, Murphy J, et al. Trends in financial relationships between industry and radiation oncologists versus other physicians in the United States from 2014 to 2018. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;109((1)):15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarras ES, Marshall DC, Rosenzweig K, Korenstein D, Chimonas S. Trends in industry payments to medical oncologists in the United States since the inception of the open payments program, 2014 to 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7((3)):440–444. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2018. Survey of physicians, dentists and pharmacists 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inoue K, Blumenthal DM, Elashoff D, Tsugawa Y. Association between physician characteristics and payments from industry in 2015–2017: observational study. BMJ Open. 2019 Sep 20;9((9)):e031010. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Japan Lung Cancer Society . Online. The Japan Lung Cancer Society; 2021. The 2021 edition of the clinical guidelines for lung cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiho . Jiho; 2021. Yakuji handbook 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Japanese Respiratory Society . 5th ed. Japanese Respiratory Society; 2018. The JRS guidelines for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease . GOLD; 2022. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2022 report. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeh JS, Franklin JM, Avorn J, Landon J, Kesselheim AS. Association of industry payments to physicians with the prescribing of brand-name statins in Massachusetts. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176((6)):763–768. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitchell AP, Winn AN, Dusetzina SB. Pharmaceutical industry payments and oncologists' selection of targeted cancer therapies in medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178((6)):854–856. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goupil B, Balusson F, Naudet F, Esvan M, Bastian B, Chapron A, et al. Association between gifts from pharmaceutical companies to French general practitioners and their drug prescribing patterns in 2016: retrospective study using the French Transparency in Healthcare and National Health Data System databases. BMJ. 2019 Nov 5;367:l6015. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Annapureddy AR, Henien S, Wang Y, Minges KE, Ross JS, Spatz ES, et al. Association between industry payments to physicians and device selection in icd implantation. JAMA. 2020 Nov 3;324((17)):1755–1764. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bickford T, Kinder N, Arthur W, Wayant C, Vassar M. The potential effects of financial conflicts of interest of speakers at the US Food and Drug Administration's pulmonary-allergy drug advisory committee meetings. Chest. 2021 Jun;159((6)):2399–401. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fickweiler F, Fickweiler W, Urbach E. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry generally and sales representatives specifically and their association with physicians' attitudes and prescribing habits: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017 Sep 27;7((9)):e016408. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Institute of Medicine . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schunemann HJ, Al-Ansary LA, Forland F, Kersten S, Komulainen J, Kopp IB, et al. Guidelines international network: principles for disclosure of interests and management of conflicts in guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Oct 6;163((7)):548–553. doi: 10.7326/M14-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Data Availability Statement

All data are available on the Japanese Respiratory Society's webpage. All the payment data used in this study are included as online supplementary Material 2. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.