Abstract

We investigated the immunopathophysiologic responses during sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) in CD4-deficient (CD14 knockout [CD14KO]) mice. Our studies were designed to specifically test the role of CD14 in the inflammatory response to sepsis and to ascertain if alterations would improve morbidity or mortality. Sepsis was induced using the CLP model with appropriate antibiotic treatment. The severity of sepsis increased in the CD14KO mice with increasing puncture size (18 gauge [18G], 21G, and 25G). Following CLP, body temperature (at 12 h) and gross motor activity levels of the sham and 25G CLP groups recovered to normal, while the 21G and 18G CLP groups exhibited severe hypothermia coupled with decreased gross motor activity and body weight. There were no significant differences in survival, temperature, body weight, or activity levels between CD14KO and control mice after 21G CLP. However, CD14KO mice expressed two- to fourfold less pro-inflammatory (interleukin-1β [IL-1β], tumor necrosis factor [TNF], and IL-6) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10, IL-1 receptor antagonist, and TNF receptors I and II) cytokines in the blood after 21G CLP. Plasma levels of the chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein 2α and KC were similarly reduced in CD14KO mice. A similar trend of decreased cytokine and cytokine inhibitor levels was observed in the peritoneal cavity of CD14KO mice. Our results indicate that the CD14 pathway of activation plays a critical role in the production of both pro-inflammatory cytokines and cytokine inhibitors but has minimal impact on the morbidity or mortality induced by the CLP model of sepsis.

Surgery, trauma, or other sources of inflammation can ultimately lead to sepsis, a common cause of morbidity and mortality. Temperature alterations, inflammation, and elevated cytokine levels are some characteristics of sepsis (6). While the etiology of sepsis is multifactorial, endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide [LPS]), a major component of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria (39, 43), is capable of inducing a sepsis-like picture. Although endotoxin in appropriate amounts can activate favorable responses by increasing the ability of macrophages to mount antimicrobial activities (35, 43), large amounts of LPS can be toxic, ultimately leading to endotoxic shock (6, 39). Appropriate host recognition and responses to LPS therefore represent a key event in determining the level and type of available protection (43).

CD14 is an LPS receptor (54) and is anchored to the monocyte/macrophage cell membrane via glycosylphosphatidyl inositol (18, 20). In vitro studies have shown that cells bearing the CD14 receptor bind LPS in the presence of LPS-binding protein (44) and are activated to produce pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and a variety of other molecules active in the innate immune response. Recently, it has been shown that signal transduction via membrane CD14 requires a signaling complex which appears to include, at a minimum, the expression of Toll 4 (9, 24, 32, 36), MD2 (47), and MYD88 (28) molecules. In addition to the membrane form, a soluble form of CD14 is present in the blood primarily as a result of shedding of the membrane form (4, 5, 20). In vitro studies show that cells lacking the membrane CD14 receptor, such as the endothelial and epithelial cells, can respond to complexes of LPS and soluble CD14 (23, 34) via an as yet unidentified receptor.

Evidence of a physiological role for membrane CD14 in response to LPS has been shown using models of endotoxemia or infection. Transgenic mice overexpressing CD14 are more sensitive to LPS-induced shock than CD14-expressing controls (15, 48), while mice deficient in CD14 (CD14 knockout [CD14KO] mice) show little or no response to a dose of LPS that is 10-fold higher than a 100% lethal dose for CD14-expressing mice (21). Furthermore, intraperitoneal or intravenous administration of a dose of Escherichia coli O111 that is lethal for control mice produces little or no response in CD14KO mice, indicating that CD14 mediates the LPS-induced state (21). In addition, treatment of LPS-injected rabbits with anti-CD14 polyclonal antibodies protects against organ damage and death (42). Thus, CD14 is required for the induction of endotoxemia and/or shock by LPS and/or E. coli.

In addition to these in vivo studies documenting a role for CD14 in the induction of endotoxemia and/or shock by LPS and/or E. coli, several in vitro studies have suggested that CD14 may also play a role in the shock response to a variety of other microbial pathogens including gram-positive bacteria, yeast, and spirochetes (7, 19, 31, 33, 45, 46, 55). However, the relevance of CD14 to shock induced by these organisms has yet to be confirmed in vivo.

Since it has been argued that the classic models of murine sepsis cited above do not reflect all physiological parameters of human sepsis (10), it is important to investigate the role of CD14 in additional models. One such model is CLP (cecal ligation and puncture), a model of sepsis that may be more clinically relevant and acceptable for studying the systemic response to a local infection (10). This model induces a polymicrobial peritonitis by leakage of mixed intestinal flora and presents immunopathophysiologic responses that closely parallel those observed during sepsis in humans (10). Using the CLP model, including fluid resuscitation and antibiotic treatment following puncture, we investigated the role of CD14 in the immunopathologic response to sepsis in CD14KO mice. We measured the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor [TNF], interleukin-1β [IL-1β], and IL-6), murine IL-8 analogs (macrophage inflammatory protein 2α [MIP-2α] and KC), and naturally occurring cytokine inhibitors (IL-10, IL-1 receptor antagonist [RA], and soluble TNF [sTNF] receptors I and II [RI and RII]) in the peritoneum (local) and plasma (systemic). In addition, we monitored the physiologic responses in the lethal and nonlethal sepsis induced by CLP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental design:

Weight-matched wild-type (BALB/c) and CD14KO mice were used to determine host responses to septic insults. Mice were euthanized, and samples were collected 16 to 20 h and 48 h after CLP. Each time point reflects data from no fewer than two independent experiments with at least six mice in each experiment receiving CLP (21-gauge [21G] punctures) (21G mice) or sham treatment (sham mice). In all cases, both control BALB/c and the CD14KO mice underwent surgery in parallel. All surgeries were planned such that samples were harvested at the same time. We measured cytokine levels within the peritoneum (local) and plasma (systemic) at 16 to 20 h, a time point previously shown to represent peak responses (11). Samples were analyzed for the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF, IL-6, IL-1β, KC, and MIP-2α and for the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-1 RA, sTNF RI and RII, and IL-10.

In the mortality study, we monitored the temperature and gross motor activities of each animal in the study for 7 days. Temperature data were averaged for a 30-min interval, analyzed on a spreadsheet, and plotted against time after surgery. Gross motor activity counts for each animal in each treatment group for a given time point were pooled to correspond to 12-h light or dark cycle, analyzed, and plotted against time.

Animals.

BALB/c mice were obtained from Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc. (Indianapolis, Ind.). CD14KO mice, originally generated in a C57BL/6 background by targeted disruption of the CD14 gene in murine 129/Sv embryonic stem cells (21), were backcrossed onto the BALB/c background for 10 generations. Mice were acclimated to the laboratory environment for at least 24 h before surgery and were maintained under standard laboratory conditions. After surgery, mice were housed one per cage in a temperature-controlled room with food and water ad libitum and were kept under a 12-h light/12-h dark diurnal cycle.

The experiments described below were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the University of Michigan Animal Care and Use Committee.

CLP. (i) Mortality study.

CLP was performed as previously described (3, 11), with minor or no modifications. Briefly, female BALB/c mice (19 to 23 g) were anesthetized with ketamine (87 μg/g; Ketaset; Fort Dodge Laboratories, Inc., Fort Dodge, Iowa) and xylazine (13 μg/g; Rompun; Bayer Corporation, Shawnee Mission, Kans.) After a midline incision was made, the cecum was located, ligated, and perforated twice with a 25G, 21G, or 18G needle. A small amount of stool was extruded to ensure wound patency, and the abdomen was closed in two layers. Sham mice also had surgery done along with cecal manipulations but without CLP. To monitor continuous temperature and gross motor activities, animals were implanted subcutaneously with Minimitter transmitters (Vitalview Series 4000 E-Mitters; Minimitters Co., Sunriver, Oreg.). Each mouse received a subcutaneous injection of warm (37°C) saline immediately after surgery and was placed in an incubator (37°C) for 15 min. Mice were then moved to a closed room, maintained at 22°C with 12-h dark/light cycle, and given a subcutaneous injection of the antibiotic imipenem (Primaxin; Merck & Co., Inc., West Point, Pa.) at 2 h (and every 12 h up to 3 days). Cumulative mortality was assessed for 7 days with 3 to 15 mice per CLP group. We did not collect either blood or peritoneal fluid from these mice.

(ii) Kinetics study.

Groups of mice from each strain were subjected to 21G CLP needle as described above. Sham mice received a laparotomy. Minimitters were not implanted into these mice. Mice were sacrificed at 16 to 20 h or 48 h after surgery, and samples were collected for later analyses.

Sample harvesting. (i) Peripheral blood.

At the appropriate time point, EDTA-anticoagulated blood (20 μl) was collected from the tail while the mice were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine. Blood was also collected from the retro-orbital venous plexus into heparin tubes before mice were sacrificed. Plasma was collected by centrifugation (600 × g, 5 min) and stored at −20°C for later cytokine analyses.

(ii) Peritoneal lavage.

Peritoneal washes were performed with 1 ml of ice-cold Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS; GIBCO, Grand Island, N.Y.) followed by a separate 10-ml HBSS wash. The 1-ml wash was centrifuged (600 × g, 5 min), and the supernatant was stored at −20°C for later cytokine analyses. The cell pellet was pooled with cells from the 10-ml wash for cell counts and differentials.

(iii) Cell differentials.

Cells were prepared for differential counts in a cytospin fluid. Cytospin slides were then stained with Diff-Quick (Baxter, Detroit, Mich.), and white blood cell (WBC) differentials were performed after tallying 300 cells. The total for each cell type was calculated by dividing each cell type by 300 and multiplying by the total WBC count obtained from the Coulter Counter (model ZF; Coulter Electronics Inc., Hialeah, Fla.).

Cytokine analyses.

To reduce errors due to assay variation, all cytokine measures were performed simultaneously.

IL-6 assay.

An IL-6 bioassay using B9 cells was used to quantify IL-6 concentrations. These cells proliferate in the presence of IL-6 (1). Samples were serially diluted across a 96-well plate, and B9 cells (in Iscove's modified Dulbecco medium [GIBCO]) were seeded into each well. Plates were incubated in a humidified chamber (5% CO2, 37°C) for 3 days. Cell proliferation was determined by staining with the cell proliferation reagent {4-[3-(4-iodophenyl)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-5-tetrazolio]-1,2-benzene disulfonate (WST-1; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.)} at a final dilution of 1:63. Plates were then incubated for an additional 24 h, after which absorbances were quantified on a Bio-Kinetics reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc.) using dual filters (465 nm with a 630-nm reference filter). IL-6 concentrations were determined from a standard curve of the human recombinant IL-6 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, N.J.) that was used in the same assay. This assay reliably detected samples as low as 1 to 2 pg/ml.

TNF assay.

TNF concentrations were quantified by cytolytic activity directed against the WEHI 164 subclone 13 fibrosarcoma cell line as previously described (13, 14). Briefly, samples were serially diluted across flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates, and WEHI cells in suspension (in RPMI medium with actinomycin D) were added directly on top of the diluted samples. The plates were incubated overnight in a humidified chamber (5% CO2, 37°C), and after at least 18 h, cell viability was determined with WST-1 as noted above. The concentration of TNF was determined based on a standard curve generated with the recombinant human TNF (Cetus Corp., Emeryville, Calif.) in the same assay. This assay was sensitive to 1 to 2 pg of TNF/ml.

ELISA.

All other cytokines were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Plates (Immunoplate Maxisorb; Nunc, Neptune, N.J.) were coated with either anti-mouse IL-10 monoclonal antibody (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.), goat anti-mouse monoclonal IL-1β (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, Minn.), or goat anti-sTNF RI and RII (R&D). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were raised against murine recombinant KC, MIP-2α, and IL-1 RA, purified, and used as coating antibodies. After coating with the appropriate antibody, the plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were then washed using a wash buffer containing 0.05% Tween 20 (FisherBiotech, Fair Lawn, N.J.) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked by incubating the plates with Superblock blocking buffer in PBS (IL-1β and IL-10; Pierce, Rockford, Ill.), Blocker casein in PBS (KC and MIP-2α; Pierce), or 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS (Lab blocker, used for IL-1 RA, sTNF RI, and sTNF RII) for 1 h. This and subsequent incubations were conducted at room temperature on a shaker. After washing, samples were added, and plates were incubated for 1 h. Standard curves were prepared using the appropriate recombinant murine cytokine or chemokine (IL-10 [Pharmingen]; IL-1β, sTNF RI, and sTNF RII [R&D]). We generated recombinant KC, MIP-2α and IL-1 RA that were used for the standard curves. All standard and sample dilutions were made in dilution medium (10% casein or Superblock in PBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween 20 [Surfact-Amps 20; Pierce] and 0.1% normal rabbit plasma for nonspecific blocking) or in Lab buffer plus 0.05% Tween 20. Plates were washed, and biotinylated rat anti-mouse IL-10 or goat anti-IL-1β (diluted in dilution medium) was added. A portion of rabbit KC, MIP-2α, IL-RA, and sTNF RI and RII antibodies were biotinylated and used as the detection antibody. Plates were incubated for 1 h. After washing, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, Pa.) was added, and plates were incubated for 30 min. After a final wash, 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Genzyme Diagnostics, San Carlos, Calif.) was added, plates were incubated in the dark for 15 min, and the reaction was stopped with 1.5 N H2SO4. Plates were read using dual wavelengths (465 and 590 nm) on the Bio-Tek microplate reader, and cytokine concentrations were estimated using the recombinant cytokine standard curve. The lower limits of detection were 60, 90, 25, 10, and 10 pg/ml for IL-1β, IL-10, IL-1 RA, sTNF RII, respectively. Lower limits for KC and MIP-2α were 500 and 25 pg/ml, respectively. KC did not cross-react with MIP-2α, nor did sTNF RI cross-react with sTNF RII.

Statistical analyses.

Summary statistics were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) in all figures. Differences between all treatment groups were compared by analysis of variance. The Tukey test for pairwise comparisons was performed when the overall F value was statistically significant (P < 0.05). Cytokine levels that were not detectable were assigned a value equal to half the lower limit of detection for that assay. The reported data (temperature and activity) are for those mice that did not die in the lethality study. Statistics on survival data for the 21G BALB/c and CD14KO strains were performed using Epistat (Epistat Services, Richardson, Tex.).

RESULTS

CLP mortality study.

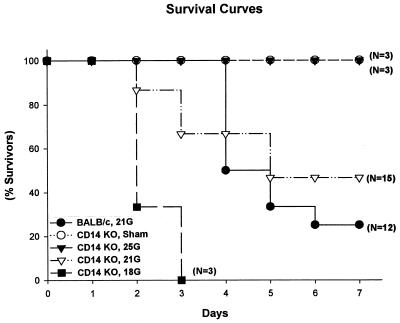

As described in Materials and Methods, a polymicrobial peritonitis was surgically induced by CLP; immediately following surgery, each mouse received fluid (warm saline, injected subcutaneously) and antibiotic (imipenem) at 2 h and every 12 h for up to 3 days. Initially, the lethality associated with different sizes of needle punctures was investigated. In agreement with previous studies with wild-type mice (11, 37), increasing the size of the puncture increased mortality in the CD14KO mice (Fig. 1). The 25G mice (three of three alive) represent the nonlethal septic group, while the 18G group (none of three alive) represented lethality. The 21G CD14KO mice (n = 15) developed essentially the same survival curves as the BALB/c mice. In the 21G model, 7 of 15 CD14KO mice and 4 of 12 wild-type mice survived. However, survival analyses showed that there were no significant differences between the CD14KO and control mice in the 21G model.

FIG. 1.

Mortality of CD14KO mice after CLP. Mortality coincided with the severity (needle gauge) of CLP. Mice received 25G, 21G, and 18G CLP, and mortality was recorded over 7 days; sham mice had surgery but no CLP. There were no statistical differences in survival between the CD14KO and BALB/c mice that had 21G CLP.

Physiologic responses.

We monitored physiologic reactions to determine the systemic responses to the different severity of insults. Similar to BALB/c mice, the physiologic response in the CD14KO mice was dependent on puncture size. Increasing puncture size led to decreasing weights, with the CLP mice losing more weight and also having a slower recovery toward normal weight (data not shown). Anorexia following sepsis could be a contributing factor to the weight loss.

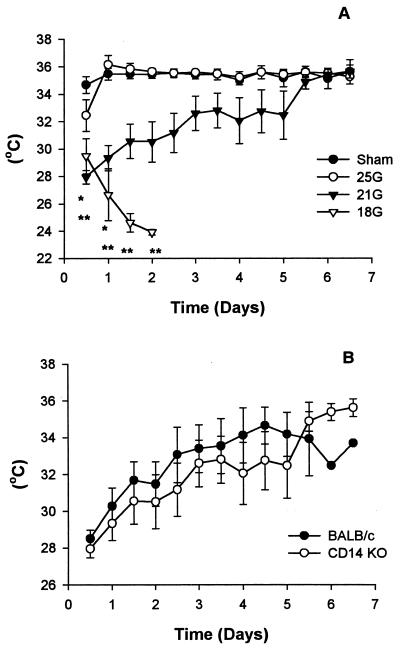

Temperature profile.

Immediately after sedation with ketamine-xylazine, all mice developed hypothermia, but the sham and 25G groups recovered to their normal temperatures within 12 h (Fig. 2A). The 21G mice did not fully attain normal temperature until day 7. The temperature of the 18G mice continued to drop until they died. There were significant differences in the temperatures of both the 21G (24 h) and 18G (until death) mice postsurgery compared to the sham-treated group in the CD14KO mice (Tukey test; P < 0.05). Temperature comparisons between the BALB/c and CD14KO mice of the 21G model (Fig. 2B) showed that there were no significant differences.

FIG. 2.

Temperature profile. Temperature measurements were monitored using Minimiters that had been inserted subcutaneously into each mouse during surgery. All mice developed hypothermia following ketamine-xylazine treatment. Both the sham and 25G CD14KO mice recovered to normal temperatures within 12 h. Although the 21G and 18G mice were initially hypothermic, the 21G mice later recovered. The symbol may be larger than the SEM. ∗, P < 0.05, 21G versus sham; ∗∗, P < 0.05, 18G versus sham.

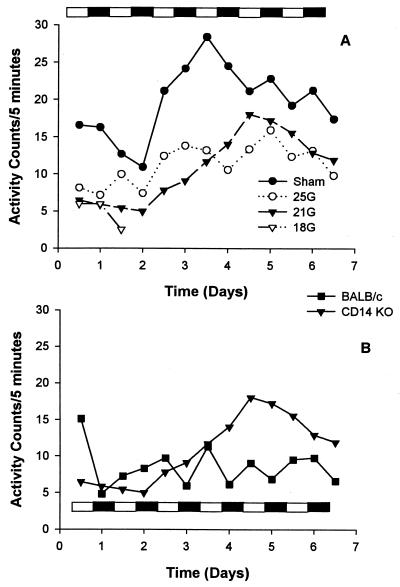

Gross motor activity profile.

The effects of sepsis on the diurnal rhythm of gross motor activity in the CD14KO and control mice were analyzed by following their day and night activities. Because mice are nocturnal, we anticipated higher activity levels at night. Mice were maintained in a temperature-controlled room with a 12-h light/dark cycle. The sham-treated CD14KO mice displayed higher activities throughout the study (Fig. 3A), while activities of the 25G- and 21G-treated groups initially declined and then gradually increased. In contrast to our previous report showing that the diurnal variations in sham BALB/c mice returned to normal within 1 day (11), the sham and 25G CD14KO mice did not recover their diurnal variations until after day 4. The 18G group exhibited decreased activities with no diurnal rhythm before death for both the CD14KO (Fig. 3A) and control BALB/c (data not shown) mice. There were no significant activity differences between the groups over the time course of the experiment. Although the 21G CD14KO mice showed a trend toward higher activities compared to similarly treated control mice (Fig. 3B), these differences were not significant. Additionally, the CD14KO mice subjected to 21G CLP did not develop a normal diurnal variation to their activity even though the activity counts were higher.

FIG. 3.

Gross motor activity and diurnal rhythm. Activity and diurnal rhythm recovery in the CD14KO mice coincided with the severity of insult (A). While the activity of the 21G BALB/c mice was generally less than the activity of the CD14KO, they did recover their diurnal variation more quickly (B). The bar showing the dark/light cycle indicates that mice were maintained in a temperature-controlled room with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. Measurements were performed using Minimitters.

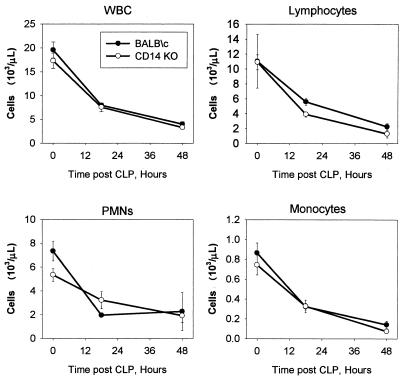

Hematologic changes.

We followed the hematologic profile of both strains by obtaining a blood sample before surgical manipulations (prebleed) and at 16 to 20 h and 48 h after 21G CLP. Peripheral blood values between the BALB/c and CD14KO mice were then compared. Blood that was collected from the retro-orbital venous plexus was cultured for microorganisms. Blood cultures were negative (consistent with the efficacy of the antibiotic treatment) although both strains showed gram-positive rod contamination, probably from hair around the retro-orbital venous plexus.

WBC counts for both strains were depressed after CLP. The peripheral blood cells were composed mostly of lymphocytes, although neutrophils were also present (Fig. 4). Consistent with previous reports, there is a significant drop induced by the sepsis which is probably related to lymphocyte apoptosis (2, 25, 26). The decrease in the total number of cells as well as the decreases in lymphocytes, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PMNs), and monocytes at 16 and 48 h were statistically different from the time zero (prebleed) value for both groups of mice (P < 0.05). The wild-type and CD14KO mice had a similar degrees of cellular loss, with little variation. There were also no significant differences in the red blood cell parameters over time or between groups (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Complete blood counts were performed using HEMAVET for the CD14KO or BALB/c mice after 21G CLP (WBC). Both strains of mice rapidly developed leukopenia due to a reduction in the number of lymphocytes, PMNs, and monocytes. The SEM may be smaller than the symbol. Each value is the mean ± SEM for 15 to 16 mice. Time zero represents the blood values prior to surgery or anesthesia. The 16- to 20-h and 48-h values are significantly different from the time zero values for all four measurements, but there are no differences between the BALB/c and CD14KO mice.

Inflammatory cytokines.

To further evaluate whether CD14 plays a role in the pathogenesis of CLP, we compared the levels of expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 in the peritoneal lavage fluid and in the blood of CD14KO and control mice that underwent 21G CLP at 16 to 20 h, a time point for peak responses (11). Control mice consistently expressed higher levels of each cytokine in the peritoneal cavity compared to CD14KO mice (Fig. 5), although these differences did not reach significance. However, these differences did reach significance in the blood, where control mice expressed two- to fourfold-higher levels of plasma IL-1β and IL-6 than CD14KO mice. No biologically active TNF was detected in the blood of either strain (data not shown), although we have previously reported TNF to be present, albeit at very low concentrations (12).

FIG. 5.

Inflammatory cytokine responses after 21G CLP. Peritoneal and plasma samples from CD14KO and BALB/c mice were harvested and measured by ELISA for IL-1β or by bioassay for TNF and IL-6. We did not detect biologically active TNF in the plasma (data not shown). Note the difference in the scale for IL-6 (nanograms per milliliter). Each value is the mean ± SEM for 15 to 16 mice. ∗, P < 0.05, BALB/c versus CD14KO.

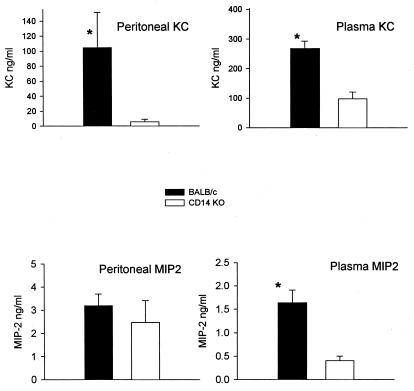

Chemokines.

To further compare the response of CD14KO and control mice to CLP, we analyzed the local and circulating expression of two chemokines, KC and MIP-2α KC levels were significantly higher in the control mice than in the CD14KO mice in both the peritoneal cavity and blood (Fig. 6). The amount of KC produced here is similar to KC levels in BALB/c mice in other studies using a similar treatment (11). Both strains of mice produced similar amounts of MIP-2α in the peritoneal cavity; however, the control BALB/c mice produced significantly higher levels of plasma MIP-2α than the CD14KO mice (Fig. 6). Thus, absence of CD14 generally resulted in decreased production of the cytokines, both within the peritoneal cavity and in the blood.

FIG. 6.

Chemokines after 21G CLP. Peritoneal fluid and plasma were collected, and chemokine levels were measured by ELISA. There was significantly more KC and peritoneal MIP-2α in the BALB/c mice than in the CD14KO mice. Each value is the mean ± SEM for 15 to 16 mice. ∗, P < 0.05, BALB/c versus CD14KO.

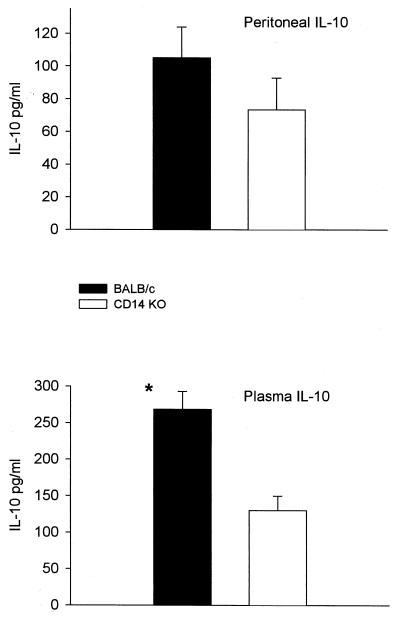

Anti-inflammatory cytokines.

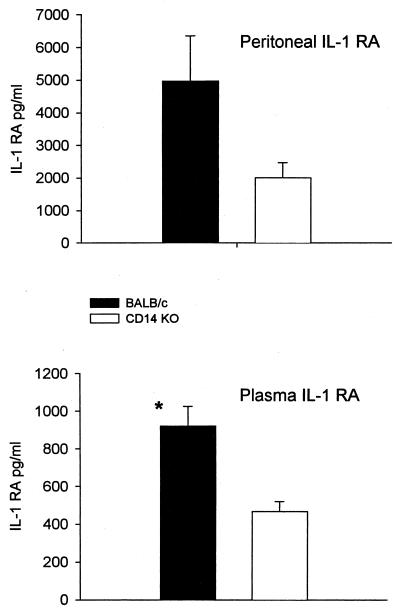

No significant differences in the expression of IL-10 were detected in the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 7), although CD14KO mice did show lower levels than the controls. In the plasma, levels of IL-10 were twice as high in the control BALB/c as in the CD14KO mice (Fig. 7). Additionally, twofold-higher levels of IL-1 RA were seen in both the peritoneal cavity and blood, with the difference in the blood achieving statistical significance (Fig. 8).

FIG. 7.

IL-10 production after 21G CLP in CD-14KO and BALB/c mice. Both strains had similar IL-10 levels, although there were greater concentrations in the BALB/c mice in the plasma at 16 to 20 h. ∗, P < 0.05, BALB/c compared to CD14KO.

FIG. 8.

IL-1 RA after 21G CLP. Plasma and peritoneal samples were collected and IL-1RA were measured by ELISA. Plasma levels in the BALB/c animals were higher than in the CD14KO mice. Each value is the mean ± SEM for 15 to 16 mice. ∗, P < 0.05, BALB/c versus CD14KO.

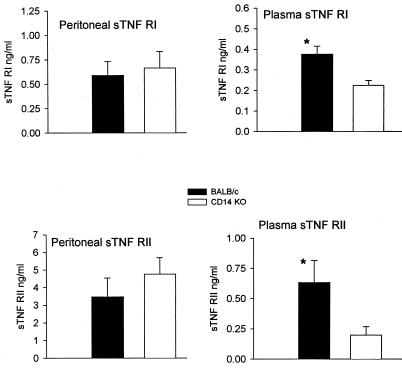

Examination of the peritoneal levels of sTNF RI or sTNF RII showed essentially no significant difference between control and CD14KO mice. In contrast, the control BALB/c mice had significantly higher plasma levels of sTNF RI and sTNF RII than CD14KO mice (Fig. 9). The increasing levels of the sTNF receptors and the concomitant decreasing levels of TNF (Fig. 5) may reflect the role of these receptors in neutralizing TNF, limiting the level of the inflammatory response to sepsis in this model.

FIG. 9.

sTNF receptors after 21G CLP. Peritoneal and plasma sTNF RI and RII levels were measured by ELISA. The plasma levels of the sTNF receptors were higher in the BALB/c mice. Each value is the mean ± SEM for 15 to 16 mice. ∗, P < 0.05, BALB/c versus CD14KO.

DISCUSSION

The goal of these studies was to determine the role of CD14 in a CLP model of sepsis. This model induces a polymicrobial peritonitis and represents a clinically relevant model for the study of the systemic response to local infection (52) since the immunopathologic manifestations of CLP are similar to those observed in a clinical setting (10). In this study, sepsis was induced from the leakage of endogenous intestinal microbial flora after perforating the ligated cecum. To model human disease, mice were given fluid (D5W) following surgery and treated with an antibiotic (imipenem) 2 h later and subsequently every 12 h for 3 days. Even though the antibiotic treatment resulted in no detectable bacteria in the blood, a 70% mortality was observed. To assess the role of CD14 in this model of sepsis, we compared mortality, temperature, and gross motor activity of CD14KO and control BALB/c mice. Additionally, we compared the levels of pro-inflammatory (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10, IL-1 RA, sTNF RI, and sTNF RII) cytokines and two chemokines (KC and MIP-2α) in both the peritoneal cavity and blood.

No significant differences in mortality, temperature, or activity were observed between CD14KO and control mice in the CLP model of sepsis (Fig. 1 to 3). Both groups of mice displayed similar rates of mortality and recovery in body temperature, and although the CD14KO mice showed a trend for faster recovery in normal activity rate, this difference was not statistically significant.

The CD14KO mice consistently showed two- to fourfold-lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, anti-inflammatory cytokines, and chemokines in both the peritoneum and blood (Fig. 5 to 9), although the differences in the peritoneal cavity often did not reach statistical significance. Nevertheless, despite these differences, CD14KO and control mice show no differences in CLP-induced sepsis. Although cytokine production depends on CD14, these differences in expression did not play a major role in the outcome of sepsis. An alternative hypothesis is that the primary determinant of biological activity is the ratio of endogenous inhibitors to the pro-inflammatory cytokines (40, 49, 50). Since both the pro-inflammatory cytokines and anti-inflammatory cytokines were depressed in the CD14KO mice, the net biological effect on the outcome of sepsis may have been the same as in the wild-type mice.

The compartmentalization of the inflammatory response has been proposed, and other studies have documented that there are higher concentrations of cytokines within the local compartment compared to the systemic circulation. This phenomenon has been termed the “tip of the iceberg” (8, 30, 41). Interestingly, no clear pattern emerges from our present study. While peritoneal levels of IL-1β, MIP-2α, IL-1 RA, and the soluble TNF receptors were higher than plasma levels, the plasma levels of IL-6 KC, and IL-10 exceeded those found within the peritoneum. Our data show that there is no clear compartmentalization of the inflammatory response following CLP. Part of this may relate to the permeability of the peritoneal cavity in the mouse, where intraperitoneal low-molecular-weight proteins gain easy access to the intravascular space.

These results differ markedly from previous observations using a different model of sepsis where the responses of CD14KO and control mice to LPS and infection with E. coli O111 were compared (21). In those studies, all of the CD14KO mice survived a lethal dose of LPS; indeed, even at a 10-fold lethal dose of LPS, CD14KO mice showed few or none of the symptoms that characterize sepsis (lethargy, ruffled fur, labored breathing, and death). Similarly, all CD14KO mice survived a lethal dose of E. coli and again showed none of the gross symptoms characteristic of sepsis. In both instances, CD14KO mice showed greatly (>1,000-fold) diminished pro-inflammatory responses compared to control mice. Similar results have been obtained with other strains of E. coli that have been isolated from septic patients (unpublished data).

The resistance displayed by CD14KO mice in the above two models of sepsis and the lack of resistance in this CLP model suggest that neither E. coli nor its LPS product plays a significant role in the latter model of sepsis. This is consistent with previous studies showing that the pathophysiology induced by administration of LPS is quite different from that induced by CLP (38). Thus, LPS and E. coli do not appear to play a role in this model of CLP-induced shock.

The lack of a role for LPS and E. coli in this model of CLP-induced shock is not surprising in view of the fact that the major organism released in this model of sepsis is Bacteroides, with a minor population of gram-positive organisms (27). Previous studies using CD14KO mice have shown that the pathophysiology induced by Bacteroides does not require CD14 (53). This is partially due to the fact that the LPS from Bacteroides is at least 1,000 times less potent than LPS from Salmonella serovar Minnesota or E. coli (17). Furthermore, studies showing that the polysaccharide capsular components of Bacteroides induce disease (51) even in the absence of CD14 (53) suggest that the pathogenic effects seen in CLP may, in large part, be mediated by the non-LPS bacterial components of Bacteroides. Similarly, it has also previously been shown that sepsis induced by gram-positive bacteria shows very little, if any, dependence on CD14. Although cell wall products of gram-positive bacteria stimulate macrophages weakly via CD14 (7, 19, 31, 33, 45, 46, 55), CD14KO mice do not show a difference from control mice in mortality or gross symptoms of shock induced by gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus [22] and Streptococcus [unpublished data]). Thus, in the two other models of infection studied using CD14KO mice, the response to Bacteroides or to gram-positive bacteria, the major types of bacteria found in this CLP model, is CD14 dependent.

There are some important similarities and differences between the present report and previous publications concerning the role of CD14. Many of the earlier studies used infusion of endotoxin as the model for sepsis (29). The inflammatory response to injected endotoxin is very different compared to CLP (38). Using endotoxin models, antibody inhibition of CD14 shows significant reductions in the production of cytokines and an improvement in either survival or physiologic parameters. In a primate model of endotoxin-induced shock, there were significant reductions in TNF, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8 (29). These results parallel those presented here, where a lack of CD14 results in significantly reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In a model of local bacterial infection induced by E. coli, there was some improvement in systemic physiologic parameters, but these were associated with decreased lung function (16). This study also documented that there were no differences in the changes in the numbers of circulating inflammatory cells with inhibition of CD14, similar to our results. While there were no reductions in the cytokines measured in this study, the authors did not measure the same profile of inflammatory mediators as we did and did not evaluate long-term outcome as an endpoint. Our results documented that a lack of CD14 will significantly modulate the inflammatory response to sepsis. However, using the clinically relevant model of CLP, there was no improvement in hypothermia, gross motor activity, leukopenia, or survival in mice which genetically lack CD14. These data clearly demonstrate that CD14 is important in modulating the inflammatory response but may not play a critical role in the outcome of sepsis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarden L A, De Groot E R, Schaap O L, Lansdorp P M. Production of hybridoma growth factor by human monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:1411–1416. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayala A, Herdon C D, Lehman D L, Ayala C A, Chaudry I H. Differential induction of apoptosis in lymphoid tissues during sepsis: variation in onset, frequency, and the nature of the mediators. Blood. 1996;87:4261–4275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker C C, Chaudry I H, Gaines H O, Baue A E. Evaluation of factors affecting mortality rate after sepsis in a murine cecal ligation and puncture model. Surgery. 1983;94:331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazil V, Baudys M, Hilgert I, Stefanova I, Low M G, Zbrozek J, Horejsi V. Structural relationship between the soluble and membrane-bound forms of human monocyte surface glycoprotein CD14. Mol Immunol. 1989;26:657–662. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(89)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bazil V, Strominger J L. Shedding as a mechanism of down-modulation of CD14 on stimulated human monocytes. J Immunol. 1991;147:1567–1574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bone R C. The pathogenesis of sepsis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:457–469. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-6-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cauwels A, Wan E, Leismann M, Tuomanen E. Coexistence of CD14-dependent and independent pathways for stimulation of human monocytes by gram-positive bacteria. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3255–3260. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3255-3260.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavaillon J M, Munoz C, Fitting C, Misset B, Carlet J. Circulating cytokines: the tip of the iceberg? Circ Shock. 1992;38:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow J C, Young D W, Golenbock D T, Christ W J, Gusovsky F. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction, J. Biol Chem. 1999;274:10689–10692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deitch E A. Animal models of sepsis and shock: a review and lessons learned. Shock. 1998;9:1–11. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199801000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebong S, Call D, Nemzek J, Bolgos G, Newcomb D, Remick D. Immunopathologic alterations in murine models of sepsis of increasing severity. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6603–6610. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6603-6610.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebong S J, Call D R, Bolgos G, Newcomb D E, Granger J I, O'Reilly M, Remick D G. Immunopathologic responses to non-lethal sepsis. Shock. 1999;12:118–126. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199908000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eskandari M K, Nguyen D T, Kunkel S L, Remick D G. WEHI 164 subclone 13 assay for TNF: sensitivity, specificity, and reliability. Immunol Investig. 1990;19:69–79. doi: 10.3109/08820139009042026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Espevik T, Nissen Meyer J. A highly sensitive cell line, WEHI 164 clone 13, for measuring cytotoxic factor/tumor necrosis factor from human monocytes. J Immunol Methods. 1986;95:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrero E, Jiao D, Tsuberi B Z, Tesio L, Rong G W, Haziot A, Goyert S M. Transgenic mice expressing human CD14 are hypersensitive to lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2380–2384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frevert C W, Matute-Bello G, Skerrett S J, Goodman R B, Kajikawa O, Sittipunt C, Martin T R. Effect of CD14 blockade in rabbits with Escherichia coli pneumonia and sepsis. J Immunol. 2000;164:5439–5445. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gangloff S C, Hijiya N, Haziot A, Goyert S M. Lipopolysaccharide structure influences the macrophage response via CD14-independent and CD14-dependent pathways. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:491–496. doi: 10.1086/515176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goyert S M, Ferrero E, Rettig W J, Yenamandra A K, Obata F, Le Beau M M. The CD14 monocyte differentiation antigen maps to a region encoding growth factors and receptors. Science. 1988;239:497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.2448876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta D, Kirkland T N, Viriyakosol S, Dziarski R. CD14 is a cell-activating receptor for bacterial peptidoglycan. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23310–23316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haziot A, Chen S, Ferrero E, Low M G, Silber R, Goyert S M. The monocyte differentiation antigen, CD14, is anchored to the cell membrane by a phosphatidylinositol linkage. J Immunol. 1988;141:547–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haziot A, Ferrero E, Kontgen F, Hijiya N, Yamamoto S, Silver J, Stewart C L, Goyert S M. Resistance to endotoxin shock and reduced dissemination of gram-negative bacteria in CD14-deficient mice. Immunity. 1996;4:407–414. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haziot A, Hijiya N, Schultz K, Zhang F, Gangloff S C, Goyert S M. CD14 plays no major role in shock induced by Staphylococcus aureus but down-regulates TNF-alpha production. J Immunol. 1999;162:4801–4805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haziot A, Rong G W, Silver J, Goyert S M. Recombinant soluble CD14 mediates the activation of endothelial cells by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1993;151:1500–1507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K, Akira S. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J Immunol. 1999;162:3749–3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hotchkiss R S, Swanson P E, Cobb J P, Jacobson A, Buchman T G, Karl I E. Apoptosis in lymphoid and parenchymal cells during sepsis: findings in normal and T- and B-cell-deficient mice. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1298–1307. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199708000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hotchkiss R S, Swanson P E, Knudson C M, Chang K C, Cobb J P, Osborne D F, Zollner K M, Buchman T G, Korsmeyer S J, Karl I E. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in transgenic mice decreases apoptosis and improves survival in sepsis. J Immunol. 1999;162:4148–4156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyde S R, Stith R D, McCallum R E. Mortality and bacteriology of sepsis following cecal ligation and puncture in aged mice. Infect Immun. 1990;58:619–624. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.3.619-624.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity. 1999;11:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leturcq D J, Moriarty A M, Talbott G, Winn R K, Martin T R, Ulevitch R J. Antibodies against CD14 protect primates from endotoxin-induced shock. J Clin Investig. 1996;98:1533–1538. doi: 10.1172/JCI118945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marie C, Losser M R, Fitting C, Kermarrec N, Payen D, Cavaillon J M. Cytokines and soluble cytokine receptors in pleural effusions from septic and nonseptic patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1515–1522. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.5.9702108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medvedev A E, Flo T, Ingalls R R, Golenbock D T, Teti G, Vogel S N, Espevik T. Involvement of CD14 and complement receptors CR3 and CR4 in nuclear factor-kappaB activation and TNF production induced by lipopolysaccharide and group B streptococcal cell walls. J Immunol. 1998;160:4535–4542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu M Y, Huffel C V, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pugin J, Heumann I D, Tomasz A, Kravchenko V V, Akamatsu Y, Nishijima M, Glauser M P, Tobias P S, Ulevitch R J. CD14 is a pattern recognition receptor. Immunity. 1994;1:509–516. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pugin J, Schurer-Maly C C, Leturcq D, Moriarty A, Ulevitch R J, Tobias P S. Lipopolysaccharide activation of human endothelial and epithelial cells is mediated by lipopolysaccharide-binding protein and soluble CD14. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2744–2748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qureshi S T, Gros P, Malo D. Host resistance to infection: genetic control of lipopolysaccharide responsiveness by TOLL-like receptor genes. Trends Genet. 1999;15:291–294. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qureshi S T, Lariviere L, Leveque G, Clermont S, Moore K J, Gros P, Malo D. Endotoxin-tolerant mice have mutations in Toll-like receptor 4 (Tlr4) J Exp Med. 1999;189:615–625. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.615. . (Erratum, 189:following 1518.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Remick D G, Garg S J, Newcomb D E, Wollenberg G, Huie T K, Bolgos G L. Exogenous interleukin-10 fails to decrease the mortality or morbidity of sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:895–904. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199805000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Remick D G, Newcomb D E, Bolgos G L, Call D R. Comparison of the mortality and inflammatory response of two models of sepsis: lipopolysaccharide vs. cecal ligation and puncture. Shock. 2000;13:110–116. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200013020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rietschel E T, Brade H, Holst O, Brade L, Muller-Loennies S, Mamat U, Zahringer U, Beckmann F, Seydel U, Brandenburg K, Ulmer A J, Mattern T, Heine H, Schletter J, Loppnow H, Schonbeck U, Flad H D, Hauschildt S, Schade U F, Di Padova F, Kusumoto S, Schumann R R. Bacterial endotoxin: chemical constitution, biological recognition, host response, and immunological detoxification. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;216:39–81. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80186-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rostoker G, Rymer J C, Bagnard G, Petit-Phar M, Griuncelli M, Pilatte Y. Imbalances in serum proinflammatory cytokines and their soluble receptors: a putative role in the progression of idiopathic IgA nephropathy (IgAN) and Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis, and a potential target of immunoglobulin therapy? Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:468–476. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schein M, Wittmann D H, Holzheimer R, Condon R E. Hypothesis: compartmentalization of cytokines in intraabdominal infection. Surgery. 1996;119:694–700. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80195-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schimke J, Mathison J, Morgiewicz J, Ulevitch R J. Anti-CD14 mAb treatment provides therapeutic benefit after in vivo exposure to endotoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13875–13880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schletter J, Heine H, Ulmer A J, Rietschel E T. Molecular mechanisms of endotoxin activity. Arch Microbiol. 1995;164:383–389. doi: 10.1007/BF02529735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schumann R R, Leong S R, Flaggs G W, Gray P W, Wright S D, Mathison J C, Tobias P S, Ulevitch R J. Structure and function of lipopolysaccharide binding protein. Science. 1990;249:1429–1431. doi: 10.1126/science.2402637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwandner R, Dziarski R, Wesche H, Rothe M, Kirschning C J. Peptidoglycan- and lipoteichoic acid-induced cell activation is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17406–17409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sellati T J, Bouis D A, Kitchens R L, Darveau R P, Pugin J, Ulevitch R J, Gangloff S C, Goyert S M, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins and synthetic lipopeptides activate monocytic cells via a CD14-dependent pathway distinct from that used by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1998;160:5455–5464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shimazu R, Akashi S, Ogata H, Nagai Y, Fukudome K, Miyake K, Kimoto M. MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1777–1782. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamura Y, Higuchi Y, Kataoka M, Akizuki S, Matsuura K, Yamamoto S. CD14 transgenic mice expressing membrane and soluble forms: comparisons of levels of cytokines and lethalities in response to lipopolysaccharide between transgenic and non-transgenic mice. Int Immunol. 1999;11:333–339. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsao T C, Hong J, Li L F, Hsieh M J, Liao S K, Chang K S. Imbalances between tumor necrosis factor-alpha and its soluble receptor forms, and interleukin-1beta and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in BAL fluid of cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis. Chest. 2000;117:103–109. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsao T C, Li L, Hsieh M, Liao S, Chang K S. Soluble TNF-alpha receptor and IL-1 receptor antagonist elevation in BAL in active pulmonary TB. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:490–495. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14c03.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tzianabos A O, Onderdonk A B, Rosner B, Cisneros R L, Kasper D L. Structural features of polysaccharides that induce intra-abdominal abscesses. Science. 1993;262:416–419. doi: 10.1126/science.8211161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wichterman K A, Baue A E, Chaudry I H. Sepsis and septic shock—a review of laboratory models and a proposal. J Surg Res. 1980;29:189–201. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(80)90037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woltmann A, Gangloff S C, Bruch H P, Rietschel E T, Solbach W, Silver J, Goyert S M. Reduced bacterial dissemination and liver injury in CD14-deficient mice following a chronic abscess-forming peritonitis induced by Bacteroides fragilis. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1999;187:149–156. doi: 10.1007/s004300050087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wright S D, Ramos R A, Tobias P S, Ulevitch R J, Mathison J C. CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science. 1990;249:1431–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1698311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshimura A, Lien E, Ingalls R R, Tuomanen E, Dziarski R, Golenbock D. Cutting edge: recognition of Gram-positive bacterial cell wall components by the innate immune system occurs via Toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 1999;163:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]