Abstract

Molecular electrocatalysts for electrochemical carbon dioxide (CO2) reduction has received more attention both by scientists and engineers, owing to their well-defined structure and tunable electronic property. Metal complexes via coordination with many π-conjugated ligands exhibit the unique electrocatalytic CO2 reduction performance. The symmetric electronic structure of this metal complex may play an important role in the CO2 reduction. In this work, two novel dimethoxy substituted asymmetric and cross-symmetric Co(II) porphyrin (PorCo) have been prepared as the model electrocatalyst for CO2 reduction. Owing to the electron donor effect of methoxy group, the intramolecular charge transfer of these push–pull type molecules facilitates the electron mobility. As electrocatalysts at −0.7 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE), asymmetric methoxy-substituted Co(II) porphyrin shows the higher CO2-to-CO Faradaic efficiency (FECO) of ~95 % and turnover frequency (TOF) of 2880 h−1 than those of control materials, due to its push–pull type electronic structure. The density functional theory (DFT) calculation further confirms that methoxy group could ready to decrease to energy level for formation *COOH, leading to high CO2 reduction performance. This work opens a novel path to the design of molecular catalysts for boosting electrocatalytic CO2 reduction.

Keywords: Co(II) porphyrin, carbon dioxide reduction, push–pull effect, electrocatalysis, faradaic efficiency

1. Introduction

Recently, metal complexes consisting of transition metal ions with heteroatom-embedded organic molecules as ligands are emerging as good catalyst materials in wide electrochemical application, due to the existence of occupied dz orbitals for the favorable catalytic CO2 reduction activity [1,2,3,4]. As the candidates of a molecular electrocatalyst, the metal complex with well-defined molecular structure could be ready to control by changing of various metal ions and organic ligands (e.g., dipyridine, terpyridine, dipyrromethane, porphyrin) with different π-conjugated systems, achieving tunable electrocatalytic performance [5,6,7]. Moreover, these metal complexes could be used as key building blocks for the preparation of organic porous polymers and single-atom carbon materials [8,9]. Different from other metal complexes, porphyrin possesses planar macrocyclic aromatics with extended π-electron conjugation, endowing them with some optical/electronic characteristics, like a broad photoabsorption wavelength, a narrow bandgap, and fast electron acceptors, among other properties [8,10,11,12,13,14]. Therefore, metal porphyrins have been proven as good candidates to be the electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction. So far, the research of porphyrin-based molecular electrocatalysts mostly focuses on the development of new porphyrin-based ligands for the improvement of CO2 reduction reactions (CO2RR).

To date, diverse analogues of porphyrins (including N-confused porphyrins [15], tetraaza [14], annulenes [16], and conjugated N4-macrocyclic ligand [17]) have been reported to coordinate with a large number of metal ions, exhibiting unique optoelectronic properties. In another way, modification of porphyrins with functional groups has been confirmed as a good strategy for improving their CO2RR performance [18,19,20]. For example, we have reported that the tertiary amine group could enhance CO production due to the enrichment of CO2 around molecules by amine groups [18]. Recently, some π-conjugated groups (like azulene, pyrene, etc.) were grafted onto the metal tetraphenylporphyrins to extend their conjugated system with lower bandgaps, resulting in the high electrocatalytic CO2 conversion [19,20]. Unfortunately, synthesis of these molecules often suffers from tedious synthetic steps with low reaction yields. Alternatively, side-chain engineering has been a versatile way to achieve functionalization of organic semiconductors [21,22,23,24,25]. For example, the push–pull structure prepared by side-chain engineering could enhance the electron delocalization for charge transfer, leading to the better electyrocatalysis [26,27]. Recently, Yaghi et al. reports that methoxy substituted Co(II) porphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks exhibit better electrocatalytic CO2 reduction, but are still far from satisfactory due to the low π-conjugation of imine bonds [22]. We also have found that methoxy substituent could efficiently tailor physical properties of conjugated polymers [28]. Owing to the commercial gain of methoxy-substituent aromatics, methoxy-functionalized metal porphyrins are easy to prepare and apply for electrochemical CO2RR. In addition, the topological structure of methoxy-functionalized metal porphyrins also is seldom exploited.

Herein, a novel kind of methoxy-functionalized Co(II) porphyrins were prepared via the conventional organic synthesis method. The chemical structures, optical/electronic properties of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe were well investigated. As electrocatalysts, these PorCo show the distinct electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. At −0.7 V versus. RHE, as-PorCo-OMe achieves a superior CO2RR performance, including FECO of 94.7% and TOF of 2880 h−1 at −0.7 V vs. RHE to the cs-PorCo-OMe. Furthermore, DFT also demonstrates that the methoxy substituent favors the push–pull effect on the porphyrin backbone, leading to the enhanced electrocatalytic CO2RR activity.

2. Results

2.1. Synthesis Description

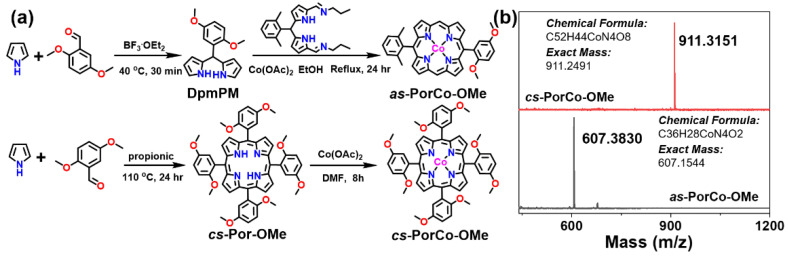

The synthetic route to two methoxy-functionalized CoPor (asymmetric and cross-symmetric CoPor named as as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe, respectively) are given in Figure 1a. The key intermediate of imine-containing dipyrromethane derivate (DMP-imine) was prepared from 2,6-dimethylbenzaldehyde using a three-step reaction in total yield of 57%, according to the reported work [29]. The 2,2′-((2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)methylene)bis(1H-pyrrole) (DmpMP) was synthesized by condensation reaction of 2,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde with pyrrole in good yield of 82%. Then, as-PorCo-OMe was prepared by a one-pot reflux reaction of DmpMP, DMP-imine and cobalt acetate [Co(OAc)2] in ethanol for 18 hrs. The pure as-PorCo-OMe was purified by alumina column chromatography with PE and DCM (v/v = 8:2) as a crimson solid in the yield of 17%. For cs-PorCo-OMe, the 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(2,5-dimethoxyphenyl) porphyrin was firstly synthesized from 2,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde and pyrrole in propionic acid for 24 h, and the crude purple solid was filtered and used without purification. After reaction with Co(OAc)2 in DMF, the cs-PorCo-OMe was obtained and purified by alumina column chromatography with PE and DCM (v/v = 6:4) as a crimson solid in yield of 15%. The detailed synthesis information and NMR spectra on these compounds is provided in Section 4 and Supplementary Materials (Figures S1–S4). The target molecular weight of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe are confirmed by mass spectrometry (MS). Figure 1b shows that the MS results are consistent with the predicted values of targeted compounds, suggesting the successful preparation of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe.

Figure 1.

(a) synthetic route to the as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe; (b) MALDI-TOF mass spectra of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe.

2.2. Structural Characterization

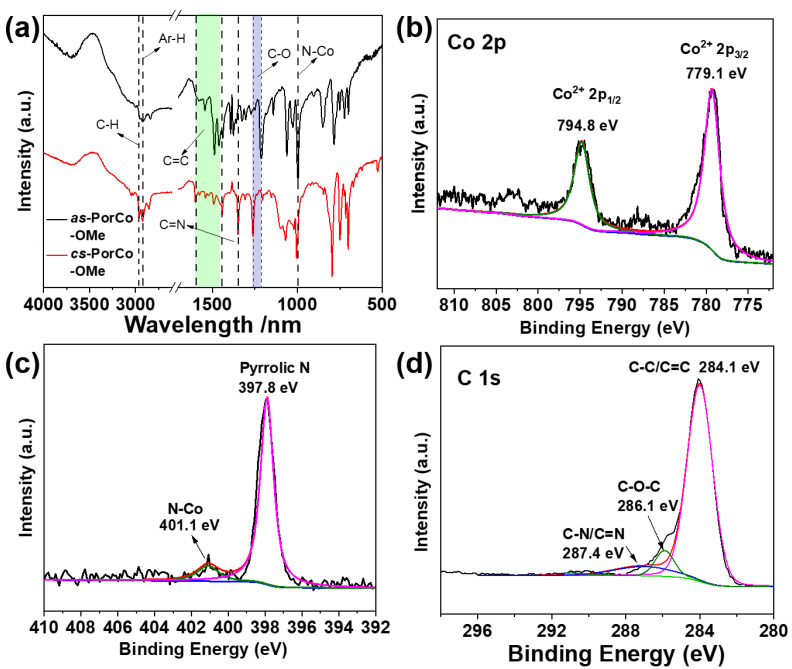

The structures of the as-prepared complexes were characterized by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). As shown in Figure 2a, the absorption bands between 1596 and 1445 cm−1 are attributed to the C = C vibration peaks of aromatic (like phenyl and pyrrole) groups, and absorption band at 1352 cm−1 is the C=N bond in the backbone of porphyrin [30], while the peak at 997 cm−1 is associated with the vibration of the Co-N bond [31]. These results demonstrate the successful preparation of Co(II) porphyrin derivates. The stretching vibration peaks of C-H is at 2965 and 2922 cm−1 for methyl and aromatic groups, respectively [18]. Moreover, the intensity of peak at 2965 cm−1 in cs-PorCo-OMe is stronger than that of as-PorCo-OMe, due to existence of eight methoxy group in cs-PorCo-OMe. The C-O bands in as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe are found at 1211 and 1258 cm−1, respectively, suggesting the stronger conjugation effect of the methoxy bond in cs-PorCo-OMe [32,33]. The chemical states of elementals of these complexes have also been investigated. Figures S5 and S6 show that elements of cobalt (Co), carbon (C), oxygen (O) and nitrogen (N) are displayed and both two complex show the similar high-resolution XPS results. In Figure 2b, the Co 2p high-resolution XPS spectra of as-PorCo-OMe exhibits two main peak at 779.1 and 794.8 eV, resulting from Co(II) atom with Co 2p3/2 and Co 2p1/2 binding energies, respectively [18]. For N 1s XPS spectra, these complexes exhibit two peaks at 397.8 and 401.1 eV, attributing to the pyrrolic N and Co-N structures, respectively (Figure 2c) [34]. In addition, the C 1s XPS spectra can be separated into three peaks at 284.1, 286.1 and 287.4 eV, indicating the bend energy of C-C/C=C, C-O and C=N, respectively (Figure 2d) [35]. These results demonstrate the accurate structure of Co(II) porphyrins with various methoxy substituents.

Figure 2.

(a) FTIR spectra of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe; High resolution Co 2p (b), N 1s (c) and C 1s (d) XPS spectra in as-PorCo-OMe.

2.3. Electronic Structures

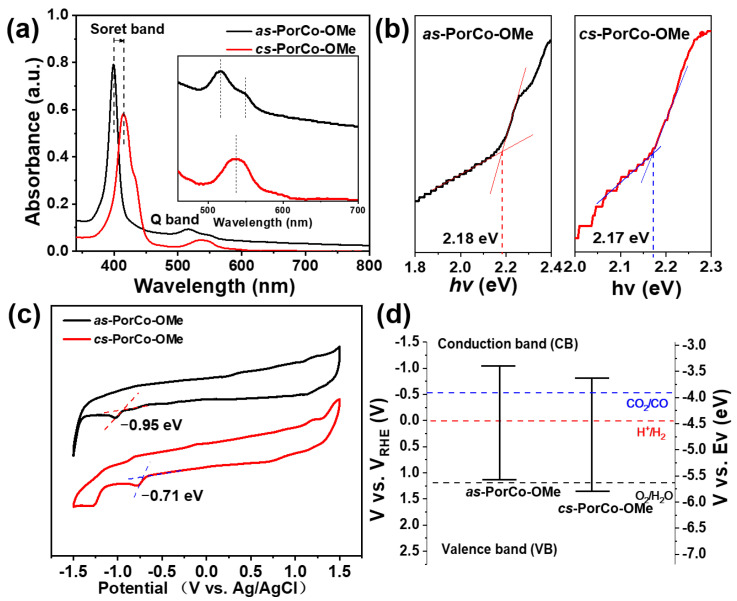

The photophysical properties of as-synthesized materials was investigated by ultraviolet and visible adsorption (UV–Vis) spectroscopy in dichloromethane (DCM) (Figure 3a). The Soret band of as-PorCo-OMe shows a strong absorbance at 398 nm, indicating the π-π* transition of porphyrin backbones, while its Q band is located between 498 and 564 nm indicating the n-π* transition from donor-acceptor structure [36]. Compared with that of as-PorCo-OMe, cs-PorCo-OMe has the enhanced push–pull effect, due to the increasing number of 2,5-dimethoxyphenyl groups, leading to the obvious red-shift phenomenon in the UV-Vis spectrum [37]. Furthermore, the board single peak of Q band suggests the symmetric structure of cs-PorCo-OMe [29]. On the basis of their UV-Vis results, the optical bandgap (Eg) of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe can be calculated to be 2.17 and 2.18 eV, respectively, by using Tauc measurement (Figure 3b). The decrease of bandgap in these complexes manifests the donor effect of the methoxy group, but, the slight change is caused by steric effect of α-functionalized methoxy substituent.

Figure 3.

(a) UV-vis absorption spectra of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe; (b) bandgap of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe calculated by Tauc method; (c) cyclic voltammetry curves of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe; (d) Band structure diagram for as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe.

The cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurement was exploited to characterize to the electronic structures of methoxy-substituted Co(II) porphrins. The CV curves, performed in argon (Ar)-saturated 0.1 M TBAPF6 DCM solution, are given in Figure 3c. The as-PorCo-OMe exhibits an irreversible one-electron reduction, while cs-PorCo-OMe has two successive reduction processes, indicating that the electron could be delocalized effectively over the molecular backbone, due to the symmetric structure of cs-PorCo-OMe [38]. The peak around −0.7~−0.9 V is the reduction reaction of Co(II)-to-Co(I) [39]. Based on the onset of first reduction potential, the LUMO energy level of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe is −3.39 and −3.63 eV, respectively. Following the equation:

| HOMO = LUMO − Eg, | (1) |

the HOMO energy levels of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe are calculated as −5.57 and−5.80 eV, respectively (Figure 3d) [40].

2.4. DFT Calculation

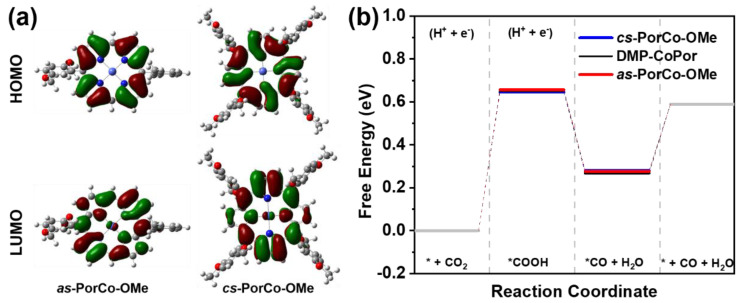

To gain deep insight into the electronic and geometric structures, frontier orbitals of these complexes were performed by DFT calculations (Figure 4a). The LUMOs of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe mainly reside on the backbone of porphyrin, indicative of their similar LUMO energy level at −2.05, and −2.08 eV, respectively. For HOMO, the porphyrin core and partial 2,5-dimethoxybenzene are covered, demonstrating the donor effect of methoxy group in the substituents [40]. With the increasing number of substituents, the push–pull effect becomes stronger. The calculated energy levels of methoxy-substituted porphyrins are well agreement with the tested results from CVs, and the detailed information is provided in Table 1.

Figure 4.

(a) Calculated HOMO and LUMO levels of of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe; (b) Free energy of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe in different CO2RR steps.

Table 1.

Electrochemical data of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe.

| Entry 1 | Ecv.red (V) [a] | Ecv,LUMO (eV) [b] | Ecv.HOMO (eV) [c] | Eopt.gap (eV) [d] | EDFT,LOMO (eV) [e] |

EDFT,HOMO (eV) [e] | EDFT,gap (eV) [e] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| as-PorCo-OMe | −0.95 | −3.39 | −5.57 | 2.18 | −2.05 | −5.13 | 3.08 |

| cs-PorCo-OMe | −0.71 | −3.63 | −5.80 | 2.17 | −2.08 | −5.12 | 3.04 |

[a] Ecv.red is the onset value of reduction potential. [b] For all molecules, Eferrocene(FOC) = 0.46 V vs. Ag/AgCl; calculated LUMO levels based on the following equation: LUMO = −[Ecv.red − EFOC] − 4.8 eV. [c] HOMO = LUMO-Eopt.gap. [d] Bandgaps determined from the UV/Vis absorption spectra using the Tauc method. [e] Calculated HOMO and LUMO levels and bandgap based on DFT simulation.

Based on pervious works, the Co(II) porphyrin has been approved as a good candidate to be the electrocatalyst for the CO2-to-CO reduction via a four-step reaction [41,42]. Thus, the DFT was carried out to investigate the reaction kinetics of the electrochemical CO2 reduction process with as-synthesized molecular catalysts (Figure S7). As shown in Figure 4b, the formation of *COOH is the rate-limiting step in CO2RR in this reaction energetics evolution. The free energy path of the conversion of CO2 to *COOH (Δ*GCOOH) requires 0.65 and 0.64 eV, respectively, for as-PorCo-OMe, and cs-PorCo-OMe, which is similar to that of 5,15-bis(2,6-dimethylphenyl) Co(II) porphyrin (DMP-CoPor). The methoxy substitution could provide the electron donor effect on a bit of enhancement of electrocatalytic activity.

2.5. Electrocatalytic CO2RR

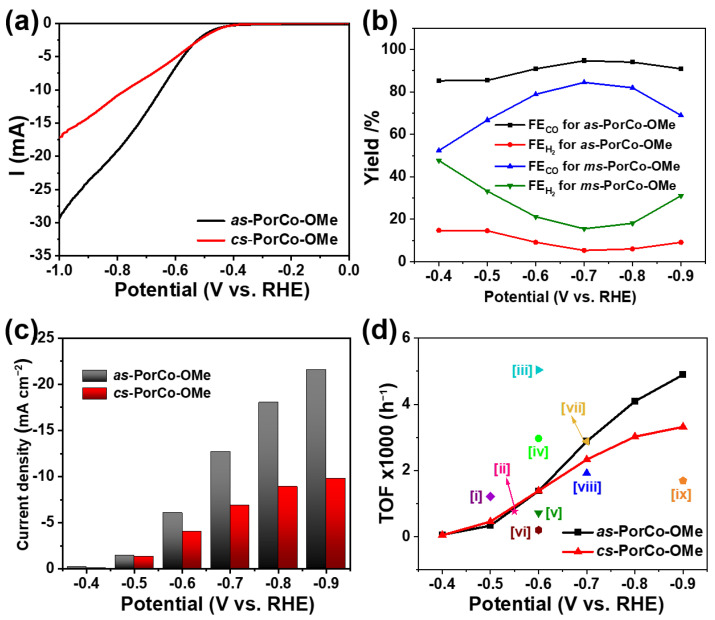

The electrocatalytic CO2RR performance of methoxy-substituted Co(II) porphyrins were evaluated in a the 0.5 M KHCO3 electrolyte using an H-type three-electrode cell with Nafion-117 as separator. All potentials are applied to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) [43]. The electrocatalytic activity of methoxy-substituted Co(II) porphyrins in the Ar- and CO2-saturated electrolyte was studied by the linear sweep voltammetry measurement. Figure S9 illustrates that the current densities of these molecules is higher in CO2 atmosphere than that in the Ar-saturated condition, suggesting the presence of electrocatalytic activity of the Co(II) porphyrin core [44]. As shown in Figure 5a, both of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe generate the increasing current densities with the increase of potential from −0.4 to −1.0 V versus RHE. Compared with cs-PorCo-OMe, the as-PorCo-OMe shows higher electrocatalytic activity. This result may result from the lower steric hindance effect of as-PorCo-OMe than that of cs-PorCo-OMe, leading to the fast electron transfer from carbon nanotubes to catalysts for enhanced electrochemical CO2RR [29].

Figure 5.

(a) LSV curves of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe in CO2-saturated 0.5 M KHCO3 electrolyte (scan rate: 5 mV s−1); (b) FECO and FEH2 of of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe at various specific potentials; (c) CO partial current densities at various specific potentials; (d) Comparison of TOF of as-prepared complex with various porphyrin-based electrocatalysts of [i] PorFe-MOF [47], [ii] COF-367-PorCo (1%) [10], [iii] PorCo/cationic POP [48], [iv] as-PorCo [29], [v] CoTMPP [49], [vi] PorCo-MOF [45], [vii] Co protoporphyrin [46], [viii] DMP-CoPor [18], [ix] PorNi-CTF [50].

The CO2RR products were tested by the online gas chromatography (GC) and off-line NMR techniques (Figure S10), which confirms that only CO and H2 were found during the reduction reaction, suggesting the high selectivity of methoxy-substituted Co(II) porphyrins. The CO Faraday efficiencies (FECO) of two complexes are given in Figure 5b. As expected, the FECO of as-PorCo-OMe reaches as high as 94.7%, which is much larger than those of DMP-CoPor (85.5%) [18], suggesting that the electron donor of methoxy substitution has the positive influence for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction by push–pull effect. Moreover, FECO of as-PorCo-OMe also is better than that of cs-PorCo-OMe (84.5%), as well as reported PorCo-TPP (91%) [39], PorCo-MOF (76%) [45] and Co proto-porphyrin (40%) [46]. Correspondingly, the partial current densities of methoxy-substituted CoPors for CO production increase with the increase of potentials. As the example of at −0.7 V, the specific current density of as-PorCo-OMe is over two times higher than that of cs-PorCo-OMe. The catalytic activities of these methoxy-substituted Co(II) porphyrins was comprehensively evaluated by the index of turnover frequency (TOF). In Figure 5d, the TOF values of two molecules gradually increased from the potential from −0.4 and −1.0 V vs. RHE, owing to the increase of current density at high potential. Compared with cs-PorCo-OMe, as-PorCo-OMe exhibits better TOF performance in the whole potentials, indicative its good electrochemical activity for CO2RR application. Furthermore, the TOF of as-PorCo-OMe (2880 h−1 at −0.7 V vs. RHE) also is superior to many reported state-of-the-art porphyrin-based electrocatalysts [10,18,29,45,46,47,48,49,50]. These results demonstrate the efficient electron and proton transfer kinetics for the push–pull type as-PorCo-OMe with weak steric hindrance.

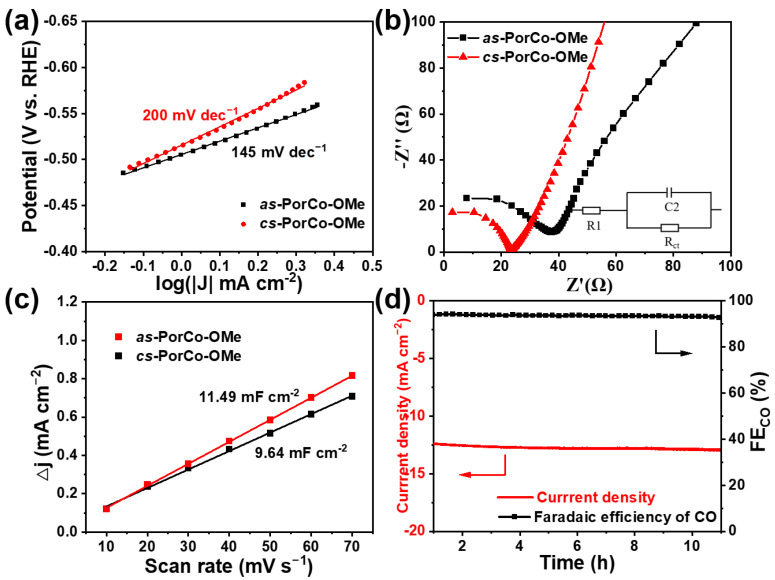

The Tafel slope represents a reaction kinetic of rate determining steps involved in electrocatalysis, which can be calculated from the polarization curves [51]. In Figure 6a, the as-PorCo-OMe shows the Tafel value of 145 mV dec−1, which is smaller than that of cs-PorCo-OMe (200 mV dec−1), indicating that as-PorCo-OMe has the higher catalytic activity of *COOH formation in CO2 reduction reaction via electron/proton transfer [52,53]. To evaluate the electrochemical behavior of as-prepared complexes in electrocatalytic CO2RR, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was carried out [54]. The charge transfer resistance (Rct) derived from the Nyquist plot exhibits that the resistance of 33.25 Ω for as-PorCo-OMe is lower than that of cs-PorCo-OMe (38.69 Ω) (Figure 6b), demonstrating the superior electron transfer ability of as-PorCo-OMe. Furthermore, the electrochemical capacitances from CV between −0.26 and −0.16 eV vs. RHE show that as-PorCo-OMe provides the higher electrochemical active surface area (Figure 6c and Figure S11), benefiting from its asymmetric push–pull structure and low steric hindrance effect. Thus, as-PorCo-OMe has been approved as the good catalyst for electrocatalytic CO2RR application. The durability performance of as-PorCo-OMe was investigated at −0.7 V vs. RHE (potential for best FECO) (Figure 4d). After testing for 12 hr, the FECO of as-PorCo-OMe remains over 93% and its current density has a low loss, and Figure S12 shows that Co 2p and N1s XPS spectra have a neglect binding energy change after the cycle experiment, demonstrating that such asymmetric Co(II) porphyrin exhibits a good electrochemical stability during long-term working.

Figure 6.

(a) Tafel slopes and (b) Nyquist plots of as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe; (c) capacitive current as a as a function of scan rate for as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe; (d) long-term stability of as-PorCo-OMe at −0.7 V vs. RHE for 12 h.

3. Conclusions

In summary, a novel kind of push–pull type Co(II) porphyrins with methoxy substitutions have been prepared efficiently by using 2,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde as starting material. The structures of these methoxy-substituted molecules have been confirmed by various measurement like MALDI-TOF MS, FTIR and XPS spectroscopy. Compared with that of as-PorCo-OMe, cs-PorCo-OMe shows the slight red-shift absorption properties and low bandgap, due to the limited donor effect of methoxy substitution in these structures. Such as-prepared Co(II) porphyrins bearing electrocatalytic active site of cobalt ion would be applied as electrocatalysts for CO2RR. In a CO2-saturated KHCO3 aqueous solution, as-PorCo-OMe exhibits the better electrochemical CO2-to-CO performance including FECO of 94.7% and TOF of 2880 h−1 at −0.7 V vs. RHE than those of cs-PorCo-OMe and reported DMP-CoPor, which is almost in agreement with that of DFT calculation. Therefore, this work provides a new molecular engineering strategy for boosting electrocatalytic CO2RR via methoxy functionalization.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

Pyrrole, 2,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde, BF3•Et2O, propionic acid, and cobalt acetate were purchased from Adamas. The DMP-imine has been prepared according to previous work. Organic solvents including chloroform (CHCl3), dichloromethane (CH2Cl2), petroleum ether (PE), dimethyl Formamide (DMF), ethyl acetate (EA), ethanol (EtOH) and all other materials were used without further purification.

4.2. Synthesis Procedures

Synthesis of 2,2′-((2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)methylene)bis(1H-pyrrole) (DpmPM). In a 250 mL flask, 2,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde (4.98 g, 30.0 mmol) and pyrrole (145 mL, 2.10 mol) was stirred under an N2 atmosphere for 30 min. BF3·OEt2 (3.56 g, 25.0 mmol) was added into the solution, and kept stirring at room temperature for 2 h. Then, NaOH (9.00 g, 225 mmol) was added for another 1 h. The crude product was received from the filtrate under reduced pressure after filtering the mixture of reaction. The product was purified by column chromatography with EtOAc and PE (v:v = 10:90) to afford a pale yellow solid product (6.8 g, 80%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ (ppm) = 3.71 (d, 6H, J = 4.25 Hz, OCH3), 5.75 (s, 1H, CHC3), 5.92 (s, 2H, Py-H), 6.13 (q, 2H, J = 8.08 Hz, Py H), 6.66 (q, 2H, J = 7.60 Hz, Py H), 6.71 (d, 1H, J = 2.77 Hz, Ar-H), 6.76 (m, 1H, Ar-H), 6.84 (d, 1H, J = 7.08 Hz, Ar-H), 8.15 (s, 8H, H-pyrrole).

Synthesis of as-PorCo-OMe. In a 250 mL flask, DMP-imine (2.00 g, 5.15 mmol), DpmPM (1.48 g, 5.27 mmol) and Co(OAc)2 (9.44 g, 51.5 mmol) were mixed in ethanol (250 mL) under an N2 atmosphere for 30 min. Then, the solution was stirred at 80 °C for 24 h. After the reaction, a dark-purple solid was collected by vacuum, and was purified by alumina column chromatography (PE/DCM = 8:2) to obtain as-PorCo-OMe (445 mg, 14%).

Synthesis of cs-Por-OMe. Pyrrole (400 mg, 5.96 mmol) and 2,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde (1002 mg, 6.04 mmol) were dissolved in propionic acid (200 mL). The solution was heated to 110 °C under an N2 atmosphere. After stirring for 24 h, the crude product was obtained via precipitation in the methanol. The pure purple solid was obtianed by washing with methanol until it was a transparent color (612 mg, 12%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ (ppm) = −2.66 (s, 2H, NH), 3.51 (m, 12H, OCH3), 3.91 (m, 12H, OCH3), 7.23–7.31 (m, 8H, Ar-H), 7.55–7.66 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 8.78 (s, 8H, H-pyrrole).

Synthesis of cs-PorCo-OMe. The obtained cs-Por-OMe (300 mg, 0.35 mmol) and Co(OAc)2 (800 mg, 4.52 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (30 mL). The solution was heated to 100 °C for 8 h under an N2 atmosephere. After reaction, the solvent was removed and the solid was precipitated in the methanol and purified by a silica gel column chromatography (PE/DCM = 6:4) to collect cs-PorCo-OMe (304 mg, 95%).

4.3. Characterizations

NMR spectra were obtained from a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz spectrometer using CDCl3 as solvents. MALDI–TOF mass spectrometry was recorded on autoflex speedTM TOF Mass Spectrometer. FTIR spectra were performed on Perkin Elmer Spectrum 100 spectrometer with KBr. XPS spectra were measured with a PHI 5000C ESCA System using C 1s (284.8 eV) as reference. UV–Vis spectra were recorded on a Lambda 950 spectrophotometer. CV tests were performed using 0.1 M TBAPF6 DCM solution as an electrolyte with the CH CHI 660E instrument.

4.4. Electrode Preparation

Firstly, catalysts (1 mg) were dispersed well in the commercial CNTs (9 mg) (Figure S8), then Nafion solution (2 mL, 0.5 wt. %) was added and stirred for 12 h. A quantity of 100 µL of mixed ink was dropped on carbon paper (surface: 1 cm2) until dry to achieve the working electrode with catalyst loading of 0.05 mg cm−2.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules28010150/s1, Electrochemical measurements; Figures S1 and S2: 1H NMR spectrum of DpmPM and cs-Por-OMe; Figure S3: TGA cruves; Figure S4: FTIR spectra of cs-PorCo-OMe and cs-Por-OMe; Figure S5: XPS spectra of as-PorCo-OMe; Figure S6: XPS spectra of cs-PorCo-OMe; Figure S7: Schematic of the reaction steps of CO2 reduction; Figure S8: SEM images; Figure S9: LSV curves in CO2-saturated and Ar-saturated electrolyte for as-PorCo-OMe and cs-PorCo-OMe; Figure S10: 1H NMR spectra of products from electrocatalyst; Figure S11: Cyclic voltammetry measurements; Figure S12: XPS spectra in as-PorCo-OMe before and after cycling test; Table S1: Comparison of CO2RR performance with reported electrocatalysts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Q. and C.L.; methodology, C.H., W.B. and S.H. (Senhe Huang); formal analysis, C.H., W.B. and B.W.; investigation, C.H., W.B. and F.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, C.H. and F.Q.; writing—review and editing, C.W. and C.L.; supervision, F.Q.; project administration, F.Q. and C.L.; funding acquisition, S.H. (Sheng Han), C.L. and F.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors.

Funding Statement

This work was financially supported from Shanghai Pujiang Program (22PJD070), Science and Technology Foundation for the Youth Development by Shanghai Institute of Technology (ZQ2021-14), the NSFC (52173205, 51973114, 21720102002), and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (19JC412600). C.L. thanks the financial support from China Postdoctoral Science Fund (2022M712032) and NSFC Young Scientists Fund (22208213).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Ren S., Joulié D., Salvatore D., Torbensen K., Wang M., Robert M., Berlinguette C.P. Molecular electrocatalysts can mediate fast, selective CO2 reduction in a flow cell. Science. 2019;365:367–369. doi: 10.1126/science.aax4608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Z., Zhang G., Du L., Zheng Y., Sun L., Sun S. Nanostructured Cobalt-Based Electrocatalysts for CO2 Reduction: Recent Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives. Small. 2020;16:2004158. doi: 10.1002/smll.202004158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nam D.-H., De Luna P., Rosas-Hernández A., Thevenon A., Li F., Agapie T., Peters J.C., Shekhah O., Eddaoudi M., Sargent E.H. Molecular enhancement of heterogeneous CO2 reduction. Nat. Mater. 2020;19:266–276. doi: 10.1038/s41563-020-0610-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marianov A.N., Jiang Y. Mechanism-Driven Design of Heterogeneous Molecular Electrocatalysts for CO2 Reduction. Acc. Mater. Res. 2022;3:620–633. doi: 10.1021/accountsmr.2c00041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maurin A., Robert M. Noncovalent Immobilization of a Molecular Iron-Based Electrocatalyst on Carbon Electrodes for Selective, Efficient CO2-to-CO Conversion in Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:2492–2495. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X., Wu Z., Zhang X., Li L., Li Y., Xu H., Li X., Yu X., Zhang Z., Liang Y., et al. Highly selective and active CO2 reduction electrocatalysts based on cobalt phthalocyanine/carbon nanotube hybrid structures. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14675. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leung J.J., Vigil J.A., Warnan J., Edwardes Moore E., Reisner E. Rational Design of Polymers for Selective CO2 Reduction Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:7697–7701. doi: 10.1002/anie.201902218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang S., Chen K., Li T.-T. Porphyrin and phthalocyanine based covalent organic frameworks for electrocatalysis. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 2022;464:214563. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du J., Ouyang H., Tan B. Porous Organic Polymers for Catalytic Conversion of Carbon Dioxide. Chem.—Asian J. 2021;16:3833–3850. doi: 10.1002/asia.202100991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin S., Diercks C.S., Zhang Y.-B., Kornienko N., Nichols E.M., Zhao Y., Paris A.R., Kim D., Yang P., Yaghi O.M., et al. Covalent organic frameworks comprising cobalt porphyrins for catalytic CO2 reduction in water. Science. 2015;349:1208–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.aac8343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y., McCrory C.C.L. Modulating the mechanism of electrocatalytic CO2 reduction by cobalt phthalocyanine through polymer coordination and encapsulation. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1683. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09626-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu H.-J., Lu M., Wang Y.-R., Yao S.-J., Zhang M., Kan Y.-H., Liu J., Chen Y., Li S.-L., Lan Y.-Q. Efficient electron transmission in covalent organic framework nanosheets for highly active electrocatalytic carbon dioxide reduction. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:497. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14237-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He T., Yang C., Chen Y., Huang N., Duan S., Zhang Z., Hu W., Jiang D. Bottom-Up Interfacial Design of Covalent Organic Frameworks for Highly Efficient and Selective Electrocatalysis of CO2. Adv. Mater. 2022;34:2205186. doi: 10.1002/adma.202205186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tahir M.N., Abdulhamied E., Nyayachavadi A., Selivanova M., Eichhorn S.H., Rondeau-Gagné S. Topochemical Polymerization of a Nematic Tetraazaporphyrin Derivative To Generate Soluble Polydiacetylene Nanowires. Langmuir. 2019;35:15158–15167. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b02187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He Q., Kang J., Zhu J., Huang S., Lu C., Liang H., Su Y., Zhuang X. N-confused porphyrin-based conjugated microporous polymers. Chem. Commun. 2022;58:2339–2342. doi: 10.1039/D1CC06572F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang Z., Zhang T., Cao P., Yoshida T., Tang W., Wang X., Zuo Y., Tang P., Heggen M., Dunin-Borkowski R.E., et al. A novel π-d conjugated cobalt tetraaza[14]annulene based atomically dispersed electrocatalyst for efficient CO2 reduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;442:136129. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.136129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun L., Huang Z., Reddu V., Su T., Fisher A.C., Wang X. A Planar, Conjugated N4-Macrocyclic Cobalt Complex for Heterogeneous Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction with High Activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:17104–17109. doi: 10.1002/anie.202007445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xuan X., Jiang K., Huang S., Feng B., Qiu F., Han S., Zhu J., Zhuang X. Tertiary amine-functionalized Co(II) porphyrin to enhance the electrochemical CO2 reduction activity. J. Mater. Sci. 2022;57:10129–10140. doi: 10.1007/s10853-022-07303-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan Y., Zhao Y., Yang S., Han S., Lu C., Ji H., Wang T., Ke C., Xu Q., Zhu J., et al. Modulating intramolecular electron and proton transfer kinetics for promoting carbon dioxide conversion. Chem. Commun. 2022;58:1966–1969. doi: 10.1039/D1CC06731A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dou S., Sun L., Xi S., Li X., Su T., Fan H.J., Wang X. Enlarging the π-Conjugation of Cobalt Porphyrin for Highly Active and Selective CO2 Electroreduction. ChemSusChem. 2021;14:2126–2132. doi: 10.1002/cssc.202100176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu M.-K., Wang N., Ma D.-D., Zhu Q.-L. Surveying the electrocatalytic CO2-to-CO activity of heterogenized metallomacrocycles via accurate clipping at the molecular level. Nano Res. 2022;15:10070–10077. doi: 10.1007/s12274-022-4444-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diercks C.S., Lin S., Kornienko N., Kapustin E.A., Nichols E.M., Zhu C., Zhao Y., Chang C.J., Yaghi O.M. Reticular Electronic Tuning of Porphyrin Active Sites in Covalent Organic Frameworks for Electrocatalytic Carbon Dioxide Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:1116–1122. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b11940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang X., Li Q.-X., Chi S.-Y., Li H.-F., Huang Y.-B., Cao R. Hydrophobic perfluoroalkane modified metal-organic frameworks for the enhanced electrocatalytic reduction of CO2. SmartMat. 2022;3:163–172. doi: 10.1002/smm2.1086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song Y., Zhang J.-J., Dou Y., Zhu Z., Su J., Huang L., Guo W., Cao X., Cheng L., Zhu Z., et al. Atomically Thin, Ionic–Covalent Organic Nanosheets for Stable, High-Performance Carbon Dioxide Electroreduction. Adv. Mater. 2022;34:2110496. doi: 10.1002/adma.202110496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costentin C., Drouet S., Robert M., Savéant J.-M. A Local Proton Source Enhances CO2 Electroreduction to CO by a Molecular Fe Catalyst. Science. 2012;338:90–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1224581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centane S., Sekhosana E.K., Matshitse R., Nyokong T. Electrocatalytic activity of a push-pull phthalocyanine in the presence of reduced and amino functionalized graphene quantum dots towards the electrooxidation of hydrazine. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2018;820:146–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2018.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdinejad M., Dao C., Deng B., Dinic F., Voznyy O., Zhang X.-a., Kraatz H.-B. Electrocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to CH4 and CO in Aqueous Solution Using Pyridine-Porphyrins Immobilized onto Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020;8:9549–9557. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c02791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu K., Bi S., Ming W., Wei W., Zhang Y., Xu J., Qiang P., Qiu F., Wu D., Zhang F. Side-chain-tuned π-extended porous polymers for visible light-activated hydrogen evolution. Polym. Chem. 2019;10:3758–3763. doi: 10.1039/C9PY00512A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bao W., Huang S., Tranca D., Feng B., Qiu F., Rodríguez-Hernández F., Ke C., Han S., Zhuang X. Molecular Engineering of CoII Porphyrins with Asymmetric Architecture for Improved Electrochemical CO2 Reduction. ChemSusChem. 2022;15:e202200090. doi: 10.1002/cssc.202200090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen L., Yang Y., Jiang D. CMPs as Scaffolds for Constructing Porous Catalytic Frameworks: A Built-in Heterogeneous Catalyst with High Activity and Selectivity Based on Nanoporous Metalloporphyrin Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:9138–9143. doi: 10.1021/ja1028556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Z.-S., Chen L., Liu J., Parvez K., Liang H., Shu J., Sachdev H., Graf R., Feng X., Müllen K. High-Performance Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction Derived from Cobalt Porphyrin-Based Conjugated Mesoporous Polymers. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:1450–1455. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chambon S., Rivaton A., Gardette J.-L., Firon M., Lutsen L. Aging of a donor conjugated polymer: Photochemical studies of the degradation of poly[2-methoxy-5-(3′,7′-dimethyloctyloxy)-1,4-phenylenevinylene] J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2007;45:317–331. doi: 10.1002/pola.21815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atreya M., Li S., Kang E.T., Neoh K.G., Ma Z.H., Tan K.L., Huang W. Stability studies of poly(2-methoxy-5-(2′-ethyl hexyloxy)-p- (phenylene vinylene) [MEH-PPV] Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1999;65:287–296. doi: 10.1016/S0141-3910(99)00018-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu J., Shi H., Shen Q., Guo C., Zhao G. A biomimetic photoelectrocatalyst of Co–porphyrin combined with a g-C3N4 nanosheet based on π–π supramolecular interaction for high-efficiency CO2 reduction in water medium. Green Chem. 2017;19:5900–5910. doi: 10.1039/C7GC02657A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li S., Kang E.T., Neoh K.G., Ma Z.H., Tan K.L., Huang W. In situ XPS studies of thermally deposited potassium on poly(p-phenylene vinylene) and its ring-substituted derivatives. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2001;181:201–210. doi: 10.1016/S0169-4332(01)00397-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng W., Shan N., Yu L., Wang X. UV–visible, fluorescence and EPR properties of porphyrins and metalloporphyrins. Dyes Pigment. 2008;77:153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2007.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuda A., Osuka A. Fully Conjugated Porphyrin Tapes with Electronic Absorption Bands That Reach into Infrared. Science. 2001;293:79–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1059552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qiu F., Zhang F., Tang R., Fu Y., Wang X., Han S., Zhuang X., Feng X. Triple Boron-Cored Chromophores Bearing Discotic 5,11,17-Triazatrinaphthylene-Based Ligands. Org. Lett. 2016;18:1398–1401. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu X.-M., Rønne M.H., Pedersen S.U., Skrydstrup T., Daasbjerg K. Enhanced Catalytic Activity of Cobalt Porphyrin in CO2 Electroreduction upon Immobilization on Carbon Materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:6468–6472. doi: 10.1002/anie.201701104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu K., Qiu F., Yang C., Tang R., Fu Y., Han S., Zhuang X., Mai Y., Zhang F., Feng X. Nonplanar Ladder-Type Polycyclic Conjugated Molecules: Structures and Solid-State Properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015;15:3332–3338. doi: 10.1021/acs.cgd.5b00429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han N., Wang Y., Ma L., Wen J., Li J., Zheng H., Nie K., Wang X., Zhao F., Li Y., et al. Supported Cobalt Polyphthalocyanine for High-Performance Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Chem. 2017;3:652–664. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Y.-R., Huang Q., He C.-T., Chen Y., Liu J., Shen F.-C., Lan Y.-Q. Oriented electron transmission in polyoxometalate-metalloporphyrin organic framework for highly selective electroreduction of CO2. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4466. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06938-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao P., Qiu Y., Zhang T., Su P., Li X., Zhang H. N-Doped Nanoporous Carbon from Biomass as a Highly Efficient Electrocatalyst for the CO2 Reduction Reaction. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019;7:5249–5255. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b06160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng Y., Zhao S., Johannessen B., Veder J.-P., Saunders M., Rowles M.R., Cheng M., Liu C., Chisholm M.F., De Marco R., et al. Atomically Dispersed Transition Metals on Carbon Nanotubes with Ultrahigh Loading for Selective Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Reduction. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1706287. doi: 10.1002/adma.201706287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kornienko N., Zhao Y., Kley C.S., Zhu C., Kim D., Lin S., Chang C.J., Yaghi O.M., Yang P. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Electrocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:14129–14135. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen J., Kortlever R., Kas R., Birdja Y.Y., Diaz-Morales O., Kwon Y., Ledezma-Yanez I., Schouten K.J.P., Mul G., Koper M.T.M. Electrocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide to carbon monoxide and methane at an immobilized cobalt protoporphyrin. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8177. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dong B.-X., Qian S.-L., Bu F.-Y., Wu Y.-C., Feng L.-G., Teng Y.-L., Liu W.-L., Li Z.-W. Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 to CO by a Heterogeneous Catalyst of Fe–Porphyrin-Based Metal–Organic Framework. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018;1:4662–4669. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.8b00797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang J.-K., Zhu C.-Y., Jiang T.-W., Wei L., Wang H., Yu K., Yang C.-L., Zhang Y.-B., Chen C., Li Z.-T., et al. Anion exchange-induced single-molecule dispersion of cobalt porphyrins in a cationic porous organic polymer for enhanced electrochemical CO2 reduction via secondary-coordination sphere interactions. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2020;8:18677–18686. doi: 10.1039/D0TA07068H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu M., Yang D.-T., Ye R., Zeng J., Corbin N., Manthiram K. Inductive and electrostatic effects on cobalt porphyrins for heterogeneous electrocatalytic carbon dioxide reduction. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019;9:974–980. doi: 10.1039/C9CY00102F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu C., Yang J., Wei S., Bi S., Xia Y., Chen M., Hou Y., Qiu M., Yuan C., Su Y., et al. Atomic Ni Anchored Covalent Triazine Framework as High Efficient Electrocatalyst for Carbon Dioxide Conversion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019;29:1806884. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201806884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang J., Wang M., Lu C., Ke C., Liu P., Zhu J., Qiu F., Zhuang X. Platinum Atoms and Nanoparticles Embedded Porous Carbons for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Materials. 2020;13:1513. doi: 10.3390/ma13071513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xin Z., Wang Y.-R., Chen Y., Li W.-L., Dong L.-Z., Lan Y.-Q. Metallocene implanted metalloporphyrin organic framework for highly selective CO2 electroreduction. Nano Energy. 2020;67:104233. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.104233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xin Z., Liu J., Wang X., Shen K., Yuan Z., Chen Y., Lan Y.-Q. Implanting Polypyrrole in Metal-Porphyrin MOFs: Enhanced Electrocatalytic Performance for CO2RR. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2021;13:54959–54966. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c15187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Y., Wang H., Liu F., Kang J., Qiu F., Ke C., Huang Y., Han S., Zhang F., Zhuang X. Self-Assembly Approach Towards MoS2-Embedded Hierarchical Porous Carbons for Enhanced Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Chem.—Eur. J. 2021;27:2155–2164. doi: 10.1002/chem.202004371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.