Abstract

Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) underlying case-control design have uncovered hundreds of genetic loci involved in tumorigenesis and provided rich resources for identifying risk factors and biomarkers associated with cancer susceptibility. However, the application of GWAS in determining the genetic architecture of cancer survival remains unestablished. Here, we systematically evaluated genetic effects at the genome-wide level on cancer survival that included overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS), leveraging data deposited in the UK Biobank cohort of a total of 19 628 incident patients across 17 cancer types. Furthermore, we assessed the causal effects of risk factors and circulating biomarkers on cancer prognosis via a Mendelian randomization (MR) analytic framework, which integrated cancer survival GWAS dataset, along with phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) and blood genome-wide gene expression/DNA methylation quantitative trait loci (eQTL/meQTL) datasets. On average, more than 10 traits, 700 genes, and 4,500 CpG sites were prone to cancer prognosis. Finally, we developed a user-friendly online database, SUrvival related cancer Multi-omics database via MEndelian Randomization (SUMMER; http://njmu-edu.cn:3838/SUMMER/), to help users query, browse, and download cancer survival results. In conclusion, SUMMER provides an important resource to assist the research community in understanding the genetic mechanisms of cancer survival.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer ranks as a leading cause of death and remains an important barrier to increasing life expectancy worldwide (1). According to global cancer statistics, there was an estimated 10.0 million cancer deaths occurred in 2020 (2). It is noteworthy that survival probability is an important index that can be used to directly measure the tumor burden of patients, and accurate survival estimate can provide valuable insights into the precision therapy of cancer patients (3,4). Thus, there is an urgent need to identify risk factors and biomarkers that can be used in the clinic to predict cancer prognosis early.

Currently, genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have uncovered hundreds of genetic loci involved in cancer susceptibility (5–7), but their application in identifying the genetic architecture of cancer survival has not been widely established. GWASs provide a way to better understand biological mechanisms linking potential risk factors or biomarkers to diseases (8). Mendelian randomization (MR) has become an important statistical approach routinely used in ‘post-GWAS’ analyses (9); it is a well-known causal inference method that uses single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as instrumental variables (IVs, i.e. genetic predictors), and has been widely used to assess the causal association between exposures [e.g. body mass index (BMI) and smoking] and outcomes (e.g. cancer survival) (10–12).

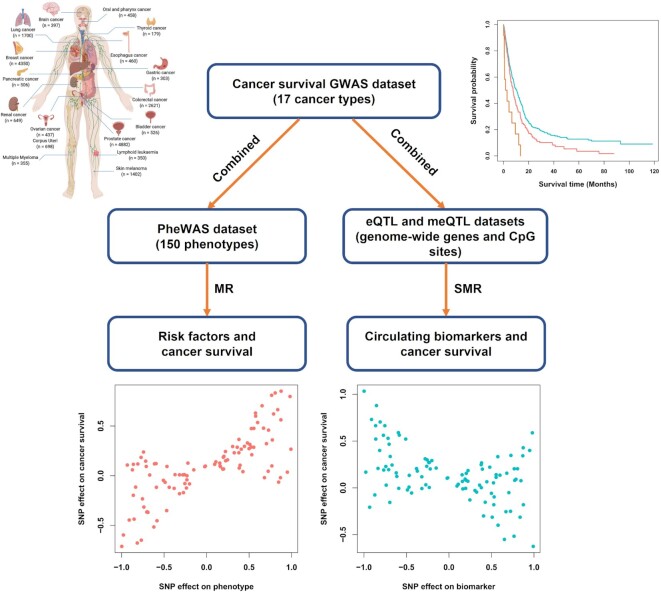

Therefore, we aimed to construct an online pan-cancer survival database that included available survival GWAS summary statistics, followed by causal risk factors and biomarkers involving cancer survival obtained via MR analysis. To meet this goal, we conducted a two-stage design in this study (Figure 1) as follows:

Figure 1.

Summary of the study design. Note: GWAS, genome-wide association study; PheWAS, phenome-wide association study; eQTL, expression quantitative trait loci; meQTL, methylation quantitative trait loci.

Construction of pan-cancer survival GWAS dataset: We aimed to systematically evaluate the effects of genome-wide genetic variants on cancer survival that included overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS), leveraging a total of 19,628 incident patients across 17 cancer types derived from the UK Biobank cohort.

Integrative analysis to identify cancer prognostic risk factors and circulating biomarkers: We aimed to evaluate the causal effects of risk factors and circulating biomarkers on cancer prognosis via a comprehensive MR approach that integrated pan-cancer survival GWAS dataset, along with phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) and blood gene expression/DNA methylation quantitative trait loci (eQTL/meQTL) datasets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of pan-cancer survival GWAS dataset

UK Biobank cohort

The UK Biobank cohort was a prospective, population-based study that recruited 502 528 adults aged 40–69 years from the general population between 2006 and 2010 (13). Participants visited one of 22 assessment centers across England, Scotland and Wales, where they completed touchscreen and nurse-led questionnaires, and provided biological samples. The study protocol and information about data access are available online (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). The current study was conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application #45611.

A total of 355 543 participants remained for analysis after the following individual-level quality control (QC) process: (i) excluded individuals with prevalent cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer, based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision [ICD-10, C44]) at baseline; (ii) excluded individuals of sex discordance; (iii) excluded outliers for genotype missingness or excess heterozygosity; (iv) retained unrelated participants; (v) restricted to ‘white British’ individuals of European ancestry and (vi) removed individuals who decided not to participate in this program. The follow-up time of cancer survival was calculated from cancer diagnosis (defined by ICD-10 codes (14)) to death or the last follow-up (14 February 2018). We determined whether an individual died of a specific cancer by considering the ICD-10 codes listed as the primary cause of death.

Pan-cancer survival GWAS analysis

All samples derived from UK Biobank were genotyped using the UK BiLEVE Axiom Array or UK Biobank Axiom Array by Affymetrix (15). The genotyping data were imputed using SHAPEIT3 and IMPUTE3 based on the reference panels of Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC), UK10K and 1000 Genomes Project (Phase 3). The study protocol and information about data access are available online (http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/UKBiobank-Protocol.pdf).

We kept variants based on a strict QC process consisting of (i) SNPs located within autosomal chromosomes; (ii) imputation info score ≥0.3; (iii) minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥0.01; (iv) call rate ≥95% and (v) Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) P value ≥1 × 10–6. Subsequently, the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis in an additive genetic model was applied to evaluate the association between each SNP and cancer survival that included OS and CSS, with adjustment for sex, age at diagnosis, BMI, smoking status, drinking status, and the top 10 principal components of population stratification when approximate. The genomic control inflation factor was used to assess the population stratification issues, and we determined cancer survival-associated loci at a suggestive genome-wide significance threshold of P-value ≤1 × 10–6.

Identification of cancer survival-associated risk factors

PheWAS dataset

The GWAS summary statistics in the PheWAS dataset were accessed through the IEU Open GWAS project (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/) and were extracted with the R package TwoSampleMR (16,17).

Based on a curated list of traits analyzed previously with an MR framework (18) and a strict QC process consisting of (i) limited in European population and (ii) with ≥3 independent [linkage disequilibrium (LD) r2 < 0.01] genetic instruments (defined by SNPs with P-value ≤ 5 × 10–8), we included a total of 150 traits in this study, which spanned the categories of anthropometric, autoimmune/inflammatory, behavioural, cardiovascular, ICD10 codes, miscellaneous, non-cancer illness, and psychiatric/neurological traits (Supplementary Table S1).

MR analysis

MR is a causal inference method, that uses germline genetic variants (i.e. SNPs) as genetic instruments to estimate and test for the causative effect of an exposure variable on an outcome (10).

Here, we used the R package TwoSampleMR to apply multiple MR methods in the phenotype-survival association analysis, including inverse variance weighted (IVW), weighted median, penalized weighted median, and MR Egger methods. In addition, the heterogeneity test was used to assess whether a genetic variant's effect on outcome was proportional to its effect on exposure, and the MR-Egger intercept test was fitted to evaluate the presence of horizontal pleiotropy (19). The suggestive evidence between phenotypes and cancer survival was identified when three nominal thresholds were met, including P-value for IVW analysis ≤0.05, P-value for egger intercept >0.05, and P-value for heterogeneity >0.05.

Identification of cancer survival-associated circulating biomarkers

eQTL and meQTL datasets

We obtained an eQTL dataset from the eQTLGen consortium (https://eqtlgen.org/), that incorporated 37 datasets, with a total of 31 684 blood samples with the majority in European ancestry. The detailed methods were described in previous studies (20). In addition, the meQTL dataset was derived from Hannon et al.’s study, with a total of 1175 blood samples of European ancestry for subsequent analysis (21).

Summary-data-based MR (SMR) analysis

Similar to phenotype-based MR analysis, the associations between biomarkers and cancer survival were evaluated using the SMR analytic framework with default settings (–peqtl-smr 5E-08 –peqtl-heidi 1.57E-03 –cis-wind 2000) by integrating the cancer survival GWAS summary statistics data with cis-eQTL and cis-meQTL results (i.e. with a window of 2000 kb to select SNPs centred around the target biomarker) (22,23). The genotype data from the European population of the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 3 were used for the LD estimation. The suggestive colocalized signals were determined at a nominal threshold of P-value for SMR analysis ≤0.05 and P-value for HEIDI (i.e. heterogeneity test in dependent instruments) >0.05.

RESULTS

Summary of cancer survival GWAS dataset

In the UK Biobank cohort, 19 628 of 355 543 individuals were newly diagnosed with one or more of 17 cancer types, ranging from 179 thyroid cancer cases to 4882 prostate cancer cases (Table 1). During a median follow-up time of 4.06 years after the clinical diagnosis, the proportion of all-cause deaths ranged from 7.33% (319/4350, breast cancer) to 90.91% (460/506, pancreatic cancer), and the proportion of cancer-specific deaths ranged from 3.35% (6/179, thyroid cancer) to 84.13% (334/397, brain cancer; Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of incident cancer cases in the UK Biobank cohort

| Gender (%) | Death (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer type | Cases | Median follow-up time (months) | Male | Female | Agea (mean ± SD) | BMI (mean ± SD) | All-cause | Cancer-specific |

| Bladder cancer | 526 | 49.63 | 426 (80.99) | 100 (19.01) | 67.11 ± 5.61 | 28.25 ± 4.34 | 170 (32.32) | 113 (21.48) |

| Brain cancer | 397 | 8.83 | 246 (61.96) | 151 (38.04) | 64.24 ± 7.04 | 27.65 ± 4.76 | 354 (89.17) | 334 (84.13) |

| Breast cancer | 4350 | 62.13 | 0 (0) | 4350 (100) | 61.84 ± 7.78 | 27.46 ± 5.10 | 319 (7.33) | 233 (5.36) |

| Colorectal cancer | 2621 | 48.57 | 1555 (59.33) | 1066 (40.67) | 65.25 ± 6.53 | 27.94 ± 4.59 | 779 (29.72) | 569 (21.71) |

| Corpus Uteri | 698 | 57.58 | 0 (0) | 698 (100) | 64.17 ± 6.29 | 30.30 ± 6.95 | 105 (15.04) | 78 (11.17) |

| Esophagus cancer | 460 | 19.57 | 344 (74.78) | 116 (25.22) | 66.42 ± 5.81 | 28.63 ± 5.61 | 296 (64.35) | 255 (55.43) |

| Gastric cancer | 303 | 14.60 | 222 (73.27) | 81 (26.73) | 66.30 ± 6.63 | 28.68 ± 4.91 | 220 (72.61) | 141 (46.53) |

| Lung cancer | 1700 | 11.47 | 945 (55.59) | 755 (44.41) | 66.65 ± 5.99 | 27.46 ± 4.73 | 1,287 (75.71) | 1,113 (65.47) |

| Lymphoid Leukaemia | 350 | 51.90 | 209 (59.71) | 141 (40.29) | 65.42 ± 6.04 | 27.96 ± 5.11 | 58 (16.57) | 26 (7.43) |

| Multiple Myeloma | 355 | 43.10 | 207 (58.31) | 148 (41.69) | 65.86 ± 6.78 | 27.79 ± 4.54 | 122 (34.37) | 90 (25.35) |

| Oral and pharynx cancer | 458 | 50.45 | 312 (68.12) | 146 (31.88) | 62.80 ± 6.94 | 27.27 ± 4.92 | 120 (26.2) | 71 (15.5) |

| Ovarian cancer | 437 | 40.33 | 0 (0) | 437 (100) | 63.65 ± 7.26 | 27.29 ± 4.86 | 201 (46) | 177 (40.5) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 506 | 5.35 | 274 (54.15) | 232 (45.85) | 66.27 ± 6.29 | 28.21 ± 5.02 | 460 (90.91) | 422 (83.4) |

| Prostate cancer | 4882 | 57.93 | 4,882 (100) | 0 (0) | 66.77 ± 5.32 | 27.55 ± 3.83 | 460 (9.42) | 258 (5.28) |

| Renal cancer | 649 | 44.40 | 425 (65.49) | 224 (34.51) | 65.21 ± 6.38 | 29.18 ± 5.26 | 209 (32.2) | 147 (22.65) |

| Skin Melanoma | 1402 | 56.27 | 717 (51.14) | 685 (48.86) | 63.39 ± 7.68 | 27.58 ± 4.48 | 119 (8.49) | 79 (5.63) |

| Thyroid cancer | 179 | 60.27 | 57 (31.84) | 122 (68.16) | 62.06 ± 7.56 | 27.66 ± 4.70 | 16 (8.94) | 6 (3.35) |

aAge at diagnosis.

Note: BMI, body mass index.

Subsequently, we applied GWAS analysis to evaluate the prognostic effects of an average of 8 332 476 SNPs across 17 cancer types. The genomic control inflation factor (i.e. lambda; OS/CSS) ranged from 0.77/0.37 for thyroid cancer to 1.12/1.12 for brain cancer, indicating no residual population stratification issues for most cancers. Based on a suggestive genome-wide significance threshold (P ≤ 1 × 10–6), we identified a total of 1209 OS-associated and 1539 CSS-associated SNPs across 17 cancer types, ranging from 4 loci for lung cancer to 57 loci for lymphoid leukemia among OS-related SNPs, and from 7 loci for colorectal cancer to 54 loci for gastric cancer among CSS-related SNPs (Table 2; Supplementary Figure S1; Table S2).

Table 2.

Summary of the significant associations of risk factors and circulating biomarkers with cancer survival via Mendelian randomization analysis

| Significant associations with overall survival | Significant associations with cancer-specific survival | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer type | No. of SNPs | Lambda | SNPsa | Locia | Phenotypesb | Genesc | CpG sitesc | Lambda | SNPsa | Locia | Phenotypesb | Genesc | CpG sitesc |

| Bladder cancer | 8 326 282 | 1.03 | 34 | 23 | 12 | 710 | 4692 | 1.03 | 134 | 38 | 13 | 737 | 5017 |

| Brain cancer | 8 390 743 | 1.12 | 108 | 39 | 4 | 847 | 5514 | 1.12 | 98 | 38 | 4 | 877 | 5574 |

| Breast cancer | 8 338 638 | 1.01 | 99 | 15 | 11 | 705 | 4681 | 1.01 | 29 | 12 | 14 | 677 | 4731 |

| Colorectal cancer | 8 334 629 | 1.01 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 692 | 4425 | 1.01 | 10 | 7 | 15 | 689 | 4301 |

| Corpus Uteri | 8 360 934 | 1.01 | 161 | 35 | 7 | 629 | 4774 | 0.98 | 138 | 31 | 8 | 708 | 4700 |

| Esophagus cancer | 8 296 714 | 1.07 | 47 | 36 | 9 | 717 | 5034 | 1.07 | 36 | 31 | 7 | 729 | 5198 |

| Gastric cancer | 8 283 963 | 1.06 | 177 | 50 | 11 | 743 | 4953 | 1.07 | 270 | 54 | 12 | 716 | 5117 |

| Lung cancer | 8 355 227 | 1.01 | 24 | 4 | 12 | 677 | 4518 | 1.01 | 13 | 9 | 13 | 666 | 4678 |

| Lymphoid Leukaemia | 8 425 952 | 0.97 | 98 | 57 | 12 | 757 | 5208 | 0.84 | 271 | 36 | 15 | 792 | 5142 |

| Multiple Myeloma | 8 258 091 | 1.07 | 73 | 39 | 12 | 680 | 4861 | 1.05 | 104 | 41 | 13 | 710 | 5041 |

| Oral and pharynx cancer | 8 272 464 | 1.05 | 99 | 30 | 9 | 762 | 4802 | 0.99 | 80 | 39 | 13 | 760 | 4819 |

| Ovarian cancer | 8 351 777 | 1.07 | 138 | 48 | 11 | 713 | 4978 | 1.06 | 90 | 46 | 6 | 671 | 4856 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 8 299 001 | 1.07 | 29 | 22 | 9 | 700 | 4746 | 1.06 | 86 | 26 | 10 | 678 | 4512 |

| Prostate cancer | 8 333 069 | 1.01 | 15 | 11 | 13 | 703 | 4559 | 1.00 | 29 | 9 | 18 | 719 | 4415 |

| Renal cancer | 8 376 852 | 1.03 | 32 | 17 | 11 | 754 | 5007 | 1.03 | 91 | 24 | 6 | 728 | 4712 |

| Skin Melanoma | 8 339 443 | 0.99 | 55 | 22 | 14 | 668 | 4350 | 0.96 | 60 | 25 | 16 | 679 | 4635 |

| Thyroid cancer | 8 308 306 | 0.77 | 13 | 7 | 23 | 721 | 4977 | 0.37 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 451 | 2491 |

a P-value for Cox regression model ≤ 1 × 10–6.

b P-value for IVW analysis ≤0.05, P-value for egger intercept >0.05, and P-value for heterogeneity >0.05.

c P-value for SMR analysis ≤0.05 and P-value for HEIDI >0.05.

Note: SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; IVW, inverse‐variance weighted; SMR, summary-data-based Mendelian randomization.

Identification of risk factors and circulating biomarkers associated with cancer survival

Furthermore, we performed an integrative MR analysis to identify cancer survival-associated risk factors and biomarkers. By combining cancer survival GWAS with PheWAS, eQTL and meQTL datasets, we found an average of 11 phenotypes [ranging from 4 (brain cancer) to 23 (thyroid cancer)], 716 genes [ranging from 629 (corpus uteri) to 847 (brain cancer)] and 4828 CpG sites [ranging from 4350 (skin melanoma) to 5514 (brain cancer)] associated with cancer OS, and an average of 11 phenotypes [ranging from 4 (brain cancer) to 18 (prostate cancer)], 705 genes [ranging from 451 (thyroid cancer) to 877 (brain cancer)] and 4702 CpG sites [ranging from 2491 (thyroid cancer) to 5574 (brain cancer)] associated with cancer CSS (Table 2; Supplementary Figures S2–S4). Interestingly, most of the prognostic biomarkers were specific to one cancer type, indicating high heterogeneity across cancers.

Web design and interface

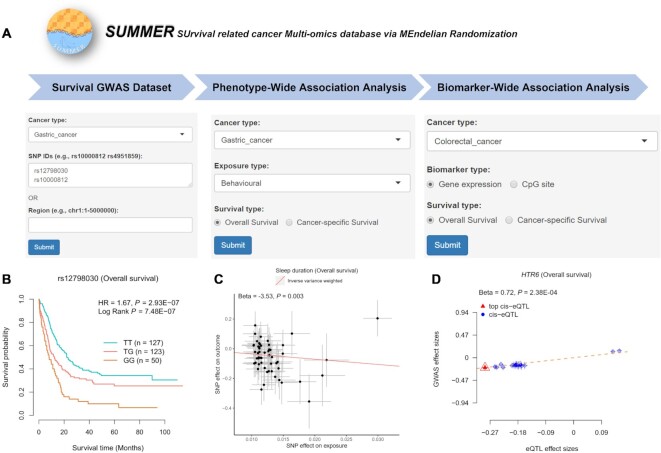

Finally, we applied the R package Shiny to develop a user-friendly database for the findings of the above two-stage analysis [SUrvival related cancer Multi-omics database via MEndelian Randomization (SUMMER): http://njmu-edu.cn:3838/SUMMER/; Figure 2A] with the following four modules: (i) ‘Survival GWAS Dataset’ module, to help users browse the association effects of over eight million genetic variants on pan-cancer survival; (ii) ‘Phenotype-Wide Association Analysis’ module, to help users browse the causal effects of 150 phenotypes on pan-cancer survival; (iii) ‘Biomarker-Wide Association Analysis’ module, to help users browse the causal effects of genome-wide genes and CpG sites on pan-cancer survival and (iv) ‘Running your data’ module, to allow users to evaluate their own data on pan-cancer survival. The ‘About’ page provides more details about the function of this database.

Figure 2.

Overview of the SUMMER database. (A) Advanced search box of the ‘Survival GWAS Dataset’, ‘Phenotype-Wide Association Analysis’ and ‘Biomarker-Wide Association Analysis’ pages. (B) Example of a KM plot for rs12798030 and gastric cancer OS, HR and P value were from the Cox regression model. (C) Example of an MR scatter plot for sleep duration and gastric cancer OS, beta and P value were from the IVW method. (D) Example of an SMR scatter plot for HTR6 and colorectal cancer OS, beta and P value were from the SMR method. Note: KM, Kaplan–Meier; OS, overall survival; MR, Mendelian randomization; SMR, summary-data-based Mendelian randomization; HR, hazard ratio; IVW, inverse‐variance weighted.

Data browsing and querying of the four modules

On the ‘Survival GWAS Dataset’ page, when users select a cancer type and enter a batch of SNP IDs or a genetic region, a table with cancer type, chromosome ID, SNP ID, SNP genomic position, SNP alleles (A1: minor/effect allele; A2: major/reference allele), MAF, hazard ratio (HR), standard error (SE) and P-value will be built to display the associations of SNPs with cancer survival that includes OS and CSS. Users can download the results by clicking the ‘Download’ button. Besides, users can select one SNP-survival pair and click the ‘Plot’ button, and the diagrams of Kaplan–Meier (KM) plot will be provided to display the associations. For example, our analysis showed that gastric cancer patients with the SNP rs12798030 TG or GG genotypes had shorter OS times than patients with the rs12798030 TT genotype (HR = 1.67, P = 2.93 × 10–7; P for log-rank test = 7.48 × 10–7; Figure 2B).

On the ‘Phenotype-Wide Association Analysis’ page, when users select a cancer type, a phenotype category (e.g. anthropometric and autoimmune/inflammatory) and a survival type (e.g. OS or CSS), a table with phenotype category, trait, trait ID, cancer type, survival type, MR method, number of IVs, and beta, SE and P-value from the MR analysis will be built to display the associations of related phenotypes with cancer survival. Users can download the results by clicking the ‘Download’ button. Besides, users can select one trait-survival pair and click the ‘Plot’ button, and the diagrams of MR scatter plot will be provided to display the associations. For example, we found that sleep duration was associated with an improved OS of gastric cancer (betaIVW = –3.53, PIVW = 0.003, Pegger intercept = 0.411, PIVW heterogeneity = 0.798; Figure 2C).

On the ‘Biomarker-Wide Association Analysis’ page, when users select a cancer type, a biomarker type (e.g. gene expression or CpG site) and a survival type (e.g. OS or CSS), a table with cancer type, survival type, probe ID, probe genomic position, top eQTL/meQTL SNP, top SNP genomic position, MAF from 1000 Genomes EUR population, top SNP-associated eQTL and survival GWAS results (including beta, SE and P-value), and beta, SE and P-value (including PSMR, Pmulti-SMR and PHEIDI) from SMR analysis will be built to display the associations of related biomarkers with cancer survival. Users can download the results by clicking the ‘Download’ button. Besides, users can select one biomarker-survival pair and click the ‘Plot’ button, and the diagrams of SMR scatter plot will be provided to display the associations. For example, our analysis showed that higher expression of HTR6 was associated with poorer OS in colorectal cancer (betaSMR = 0.72, PSMR = 2.38 × 10–4, Pmulti-SMR = 0.007, PHEIDI = 0.692; Figure 2D).

On the ‘Running your data’ page, this module consists of three steps: (i) selecting a cancer type, a data type (e.g. phenotype or biomarker), a survival type (e.g. OS or CSS), and entering a data name and email address (optional); (ii) uploading your summary statistic data (csv format); and (iii) submitting your data and performing analysis. A table derived from the MR or SMR analysis will be built to display the associations of related phenotypes/biomarkers with cancer survival, which can be downloaded by clicking the ‘Download’ button or received by email. Besides, users can select one pair and click the ‘Plot’ button, and the diagrams of MR/SMR scatter plots will be provided to display the associations.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we not only comprehensively evaluated genetic effects at the genome-wide level across pan-cancer prognoses, but also applied MR analysis to identify multiple risk factors and circulating biomarkers relevant to cancer survival. Importantly, we constructed a user-friendly database called SUMMER to help users query, browse, and download corresponding results.

Cancer mortality remains a major public health concern; therefore, the identification of prognostic risk factors or biomarkers may shed new light on precision oncology (24,25). Especially, circulating biomarkers that are usually detected in peripheral blood have been considered significant tools for monitoring cancer progression and treatment (26). Until now, it is still difficult for observational studies to estimate causal associations due to the potential confounding bias (27). Here, we proposed to apply GWAS analysis to calculate the genetic effects on cancer survival at the genome-wide level, and then used the MR analysis framework, a method for causal inference (28), to construct the SUMMER database for re-evaluating the associations of risk factors and circulating biomarkers with cancer survival. Since SNPs are randomly assorted at meiosis, MR is less likely to be affected by confounding factors compared to conventional observational studies. For example, we found that sleep duration was associated with an improved OS of gastric cancer, which was in agreement with the previously reported MR suggestive results between short sleep duration and increased gastric cancer risk (29).

Compared to other germline variants-related databases, our SUMMER database has several strengths. First, this is the first pan-cancer survival-related MR database that integrates survival GWAS with large-scale PheWAS, eQTL and meQTL datasets, to help users evaluate the causal effects of risk factors and circulating biomarkers on predicting cancer prognosis. Second, our database allows users to upload their own PheWAS or QTL summary statistics online. This allows biologists to easily conduct MR analyses for cancer survival without needing to use complex software packages. Third, we constructed a large-scale online pan-cancer survival GWAS dataset with a sufficient sample size (almost 20 000 cancer cases) derived from the well-designed UK Biobank cohort, which can help users easily evaluate the effects of genome-wide variants on cancer survival. Compared to some eQTL databases (e.g. PancanQTL) (30) with survival-eQTLs function, our database has the following advantages: (i) it is at the genome-wide level, not limited to SNPs with eQTL effects and (ii) it has a larger sample size than that from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort.

Some limitations and future directions related to this database should be noted. First, we only included European individuals in our database, and more survival-related data derived from multiple ancestries need to be incorporated in the future. Second, we need to add more cancer GWAS datasets with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up times to further increase the statistical power of our calculation. Third, more risk factors and multi-tissue biomarkers should be further included in our database.

In summary, we created a comprehensive pan-cancer survival GWAS database underlying MR analysis to evaluate the causal effects of risk factors and circulating biomarkers on cancer prognosis. We believe that SUMMER will greatly expand the understanding of the genetic mechanisms underlying cancer survival for researchers worldwide, further providing an important resource for precision oncology.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The raw genotype and clinical data have been deposited in UK Biobank (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). The pan-cancer survival results have been deposited in http://njmu-edu.cn:3838/SUMMER/. All other relevant data will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the participants and study staff of UK Biobank.

Author contributions: M.D. and M.W. are co-responders for this study. Study concept and design: J.X. and M.D. Acquisition of data: M.D. and J.X. Analysis and interpretation of data: J.X., D.G., S.C., S.B. and H.L. Study comment: Z.Z. Drafting of the manuscript: J.X. and M.D.

Ethics approval: All participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection. This study was conducted using UK Biobank (Application #45611) and other public resources.

Contributor Information

Junyi Xin, Department of Environmental Genomics, Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Cancer Biomarkers, Prevention and Treatment, Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Personalized Medicine, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Dongying Gu, Department of Oncology, Nanjing First Hospital, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Silu Chen, Department of Environmental Genomics, Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Cancer Biomarkers, Prevention and Treatment, Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Personalized Medicine, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China; Department of Genetic Toxicology, The Key Laboratory of Modern Toxicology of Ministry of Education, Center for Global Health, School of Public Health, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Shuai Ben, Department of Environmental Genomics, Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Cancer Biomarkers, Prevention and Treatment, Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Personalized Medicine, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China; Department of Genetic Toxicology, The Key Laboratory of Modern Toxicology of Ministry of Education, Center for Global Health, School of Public Health, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Huiqin Li, Department of Environmental Genomics, Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Cancer Biomarkers, Prevention and Treatment, Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Personalized Medicine, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China; Department of Genetic Toxicology, The Key Laboratory of Modern Toxicology of Ministry of Education, Center for Global Health, School of Public Health, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Zhengdong Zhang, Department of Environmental Genomics, Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Cancer Biomarkers, Prevention and Treatment, Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Personalized Medicine, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China; Department of Genetic Toxicology, The Key Laboratory of Modern Toxicology of Ministry of Education, Center for Global Health, School of Public Health, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Mulong Du, Department of Biostatistics, Center for Global Health, School of Public Health, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Meilin Wang, Department of Environmental Genomics, Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Cancer Biomarkers, Prevention and Treatment, Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Personalized Medicine, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China; Department of Genetic Toxicology, The Key Laboratory of Modern Toxicology of Ministry of Education, Center for Global Health, School of Public Health, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China; The Affiliated Suzhou Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Suzhou Municipal Hospital, Gusu School, Nanjing Medical University, Suzhou, China.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Natural Science Foundation of China [82173601, 82173603]; Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (Public Health and Preventive Medicine). Funding for open access charge: None.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lin L., Li Z., Yan L., Liu Y., Yang H., Li H.. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence and death for 29 cancer groups in 2019 and trends analysis of the global cancer burden, 1990-2019. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021; 14:197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F.. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021; 71:209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu J., Lichtenberg T., Hoadley K.A., Poisson L.M., Lazar A.J., Cherniack A.D., Kovatich A.J., Benz C.C., Levine D.A., Lee A.V.et al.. An integrated TCGA pan-cancer clinical data resource to drive high-quality survival outcome analytics. Cell. 2018; 173:400–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arnold M., Rutherford M.J., Bardot A., Ferlay J., Andersson T.M., Myklebust T.A., Tervonen H., Thursfield V., Ransom D., Shack L.et al.. Progress in cancer survival, mortality, and incidence in seven high-income countries 1995-2014 (ICBP SURVMARK-2): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2019; 20:1493–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sud A., Kinnersley B., Houlston R.S.. Genome-wide association studies of cancer: current insights and future perspectives. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2017; 17:692–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buniello A., MacArthur J., Cerezo M., Harris L.W., Hayhurst J., Malangone C., McMahon A., Morales J., Mountjoy E., Sollis E.et al.. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:D1005–D1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Visscher P.M., Brown M.A., McCarthy M.I., Yang J.. Five years of GWAS discovery. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012; 90:7–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gallagher M.D., Chen-Plotkin A.S.. The Post-GWAS era: from association to function. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018; 102:717–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zuber V., Grinberg N.F., Gill D., Manipur I., Slob E., Patel A., Wallace C., Burgess S.. Combining evidence from mendelian randomization and colocalization: review and comparison of approaches. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2022; 109:767–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith G.D., Ebrahim S.. Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease?. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2003; 32:1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davies N.M., Holmes M.V., Davey S.G.. Reading mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ. 2018; 362:k601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davey S.G., Hemani G.. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014; 23:R89–R98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sudlow C., Gallacher J., Allen N., Beral V., Burton P., Danesh J., Downey P., Elliott P., Green J., Landray M.et al.. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015; 12:e1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhu M., Wang T., Huang Y., Zhao X., Ding Y., Zhu M., Ji M., Wang C., Dai J., Yin R.et al.. Genetic risk for overall cancer and the benefit of adherence to a healthy lifestyle. Cancer Res. 2021; 81:4618–4627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bycroft C., Freeman C., Petkova D., Band G., Elliott L.T., Sharp K., Motyer A., Vukcevic D., Delaneau O., O’Connell Jet al.. The UK biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018; 562:203–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lyon M.S., Andrews S.J., Elsworth B., Gaunt T.R., Hemani G., Marcora E.. The variant call format provides efficient and robust storage of GWAS summary statistics. Genome Biol. 2021; 22:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hemani G., Zheng J., Elsworth B., Wade K.H., Haberland V., Baird D., Laurin C., Burgess S., Bowden J., Langdon R.et al.. The MR-base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. ELIFE. 2018; 7:e34408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prince C., Mitchell R.E., Richardson T.G.. Integrative multiomics analysis highlights immune-cell regulatory mechanisms and shared genetic architecture for 14 immune-associated diseases and cancer outcomes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021; 108:2259–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burgess S., Thompson S.G.. Interpreting findings from mendelian randomization using the MR-Egger method. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2017; 32:377–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vosa U., Claringbould A., Westra H.J., Bonder M.J., Deelen P., Zeng B., Kirsten H., Saha A., Kreuzhuber R., Yazar S.et al.. Large-scale cis- and trans-eQTL analyses identify thousands of genetic loci and polygenic scores that regulate blood gene expression. Nat. Genet. 2021; 53:1300–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hannon E., Gorrie-Stone T.J., Smart M.C., Burrage J., Hughes A., Bao Y., Kumari M., Schalkwyk L.C., Mill J.. Leveraging DNA-Methylation quantitative-trait loci to characterize the relationship between methylomic variation, gene expression, and complex traits. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018; 103:654–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhu Z., Zhang F., Hu H., Bakshi A., Robinson M.R., Powell J.E., Montgomery G.W., Goddard M.E., Wray N.R., Visscher P.M.et al.. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat. Genet. 2016; 48:481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu Y., Zeng J., Zhang F., Zhu Z., Qi T., Zheng Z., Lloyd-Jones L.R., Marioni R.E., Martin N.G., Montgomery G.W.et al.. Integrative analysis of omics summary data reveals putative mechanisms underlying complex traits. Nat. Commun. 2018; 9:918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smith J.C., Sheltzer J.M.. Genome-wide identification and analysis of prognostic features in human cancers. Cell Rep. 2022; 38:110569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mehta S., Shelling A., Muthukaruppan A., Lasham A., Blenkiron C., Laking G., Print C.. Predictive and prognostic molecular markers for cancer medicine. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2010; 2:125–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rapisuwon S., Vietsch E.E., Wellstein A.. Circulating biomarkers to monitor cancer progression and treatment. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2016; 14:211–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meuli L., Dick F.. Understanding confounding in observational studies. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2018; 55:737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sekula P., Del G.M.F., Pattaro C., Kottgen A.. Mendelian randomization as an approach to assess causality using observational data. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016; 27:3253–3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Titova O.E., Michaelsson K., Vithayathil M., Mason A.M., Kar S., Burgess S., Larsson S.C.. Sleep duration and risk of overall and 22 site-specific cancers: a mendelian randomization study. Int. J. Cancer. 2021; 148:914–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gong J., Mei S., Liu C., Xiang Y., Ye Y., Zhang Z., Feng J., Liu R., Diao L., Guo A.Y.et al.. PancanQTL: systematic identification of cis-eQTLs and trans-eQTLs in 33 cancer types. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:D971–D976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw genotype and clinical data have been deposited in UK Biobank (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). The pan-cancer survival results have been deposited in http://njmu-edu.cn:3838/SUMMER/. All other relevant data will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.