Abstract

From five mice immunized with Escherichia coli K1 bacteria, we produced 12 immunoglobulin M hybridomas secreting monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) that bind to Neisseria meningitidis group B (NMGB). The 12 MAbs also bound the capsular polysaccharide (PS) of E. coli K1 [which, like NMGB, is α(2-8)-linked polysialic acid (PSA)] and bound to EV36, a nonpathogenic E. coli K-12 strain producing α(2-8) PSA. Except for HmenB5, which cross-reacted with N. meningitidis group C, none of the MAbs bound to N. meningitidis groups A, C, and Y. Of the 12 MAbs, 6 were autoantibodies as defined by binding to CHP-134, a neuroblastoma cell line expressing short-chain α(2-8) PSA; five of these MAbs killed NMGB in the presence of rabbit complement, and two also killed NMGB with human complement. The other six MAbs, however, were nonautoreactive; all killed NMGB with rabbit complement, and five killed NMGB with human complement. To obtain peptide mimotopes of NMGB PS, four of the nonautoreactive MAbs (HmenB2, HmenB3, HmenB13, and HmenB14) were used to screen two types of phage libraries, one with a linear peptide of 7 amino acids and the other with a circular peptide of 7 amino acids inserted between two linked cysteines. We obtained 86 phage clones that bound to the screening MAb in the absence but not in the presence of E. coli K1 PSA in solution. The clones contained 31 linear and 4 circular mimotopes expressing unique sequences. These mimotopes nonrandomly expressed amino acids and were different from previously described mimotopes for NMGB PS. The new mimotopes may be useful in producing a vaccine(s) capable of eliciting anti-NMGB antibodies not reactive with neuronal tissue.

Neisseria meningitidis is the most common cause of bacterial meningitis in the United States, and a meningococcal vaccine is currently licensed in the United States. However, this vaccine needs to be improved for various reasons. First, this vaccine contains capsular polysaccharides (PS) from N. meningitidis serogroups A, C, Y, and W135 but not serogroup B (11). The lack of protection against N. meningitidis group B (NMGB) in a meningococcal vaccine is a serious shortcoming, because NMGB may account for 50% or more of all meningococcal meningitis cases in Europe and North America (3, 29). Second, this vaccine does not elicit antibodies in young children, who account for about 50% of meningococcal meningitis cases (29). Although conjugation of the meningococcal PS to protein carriers makes group A, C, and Y capsular PS immunogenic in young children, group B PS-protein conjugate remains poorly immunogenic (19).

There are several obstacles to generating a vaccine effective against NMGB. One obstacle is that NMGB PS may elicit autoantibodies. Antibodies to NMGB PS can be generated after natural infection (25) or after immunization with a chemically modified NMGB PS (18) or Escherichia coli K92 PS (9), which is a polymer of sialic acid (PSA) with alternating α(2-8) and α(2-9) linkages. However, the antibodies were found to bind frequently to both NMGB PS and neuronal tissue (15, 25). This cross-reaction occurs because both express a linear α(2-8) PSA. NMGB PS is a PSA with about 200 repeating units (12), and neuronal tissue has the same but shorter (about 10 to 50 repeating units) PSA as a part of neuronal cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) (8). Although the notion is controversial, the antibodies cross-reacting with the neuronal PSA are thought to have the potential to cause neurological damage. Another major obstacle is the absence of simple alternative NMGB vaccine candidate antigens. For instance, outer membrane proteins have been used as a vaccine, but this approach is limited because of significant serologic heterogeneity among different strains of NMGB (3).

Two new approaches for generating an NMGB vaccine have been suggested. One approach is to find a new vaccine candidate molecule. This approach received a significant boost from the sequencing of the entire genome of NMGB (26). Another approach is to use peptides that mimic the bacterium-specific epitope of NMGB PS as the vaccine. The feasibility of this approach has been demonstrated with the evaluation of peptide mimics of meningococcus group C (33). This approach has now become more amenable with the development of phage display technology (10, 30), which can be used to identify peptide mimotopes of PS (31). We now report the development of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) that bind and kill NMGB without binding neuronal PSA and use of these MAbs to identify peptide mimotopes of NMGB capsular PS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antigens and bacteria.

Various strains of bacteria used for this study are summarized in Table 1. All E. coli strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar plates. Neisseria strains were grown on chocolate agar plates in a candle jar. To obtain a large number of Neisseria bacteria with minimal biohazard, many chocolate agar plates were plated with the bacteria and the bacteria were then harvested from the plates after a 6-h incubation at 37°C. All bacteria were aliquoted in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 20% glycerol and stored at −70oC.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used for characterization of MAbs

| Species | Group | Strain | Characteristic(s) | Sourcea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. meningitidis | A | S-4185 | A:21 | FDA |

| A | A21 | A: | CDC | |

| A | M239 (F8238) | A:P1.5,2 | CDC | |

| B | ATCC 13090 | B: | ATCC | |

| B | H44/76 | B:15:P1.7,16 | FDA | |

| C | BB-305 | C:2b:P1.2 | FDA | |

| Y | S-1975 | Y:2a | FDA | |

| Y | WRAIR 6304 | Y:2a:P1.5,2 | FDA | |

| E. coli | RS218 | O18,K1,H7 | University of Rochester | |

| EV36 | K-12 expressing K1 PS | University of Rochester |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Ninety-six-well microtiter plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with various antibody capture agents as described below. The plates were then washed with 0.05% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBST) and blocked with 2% skim milk in PBST. Appropriately diluted samples were added to the plates and incubated for 1.5 h at 37oC. After washing, alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig; Sigma) was added. After a 90-min incubation, p-nitrophenyl phosphate was added to the plates and optical densities of the plates were measured at 405 nm.

For different purposes, the plates were coated with different agents. Some were coated with NMGB (ATCC 13090) by adding 100 μl of PBS containing heat-killed NMGB (optical density at 620 nm = 0.09) to each well and incubating the plates overnight at 37oC (1). NMGB was killed by incubating the frozen aliquots of NMGB at 65°C for 1 h followed by washes with PBS (0.82% NaCl, 1.28% Na2HPO4, pH 7.2). Some plates were coated with highly purified E. coli K1 PS (gift of R. Silver and W. Vann) by adding 100 μl of PBS containing E. coli K1 PS (10 μg/ml) to each well and incubating the plates at 37°C overnight in a humidified chamber. To determine the isotypes of antibodies, alkaline phosphatase-labeled rabbit anti-mouse isotype-specific antibodies (Zymed, South San Francisco, Calif.) were used.

Production of MAbs.

BALB/cByJ mice from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) were intraperitoneally immunized with E. coli K1 four times, twice with 107 CFU, on days 0 and 4, and twice with 108 CFU, on days 7 and 10. Live bacteria were used for fusions 1, 2, and 3, but heat-killed bacteria were used for fusions 4 and 5. Spleens were harvested on day 13 for fusion with Sp2/0-Ag14 myeloma cells, as described previously (24). The resulting hybridoma supernatants were screened by a sandwich-type ELISA as described above using ELISA plates coated with purified E. coli K1 PS in the first test and plates coated with killed NMGB bacteria in the second test. Only the hybridomas producing antibodies binding to both NMGB bacteria and E. coli K1 PS were cloned. Twelve hybridoma clones, all immunoglobulin M κ [IgM(κ)], were produced from five fusions.

To obtain purified MAbs, the tissue culture supernatant was concentrated 10-fold with ammonium sulfate, dialyzed in PBS, and fractionated by size-exclusion column chromatography using Sephacryl S-300HR (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden).

Flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry was used to test MAbs for binding to various strains of the bacteria, listed in Table 3. The bacteria were killed by incubation in 2% formaldehyde for 1 h, washed with HBSS, and suspended at 5 × 108 CFU/ml in HBSS containing 1% glycine in order to neutralize any remaining formalin. Twenty microliters of killed bacteria (5 × 108 CFU/ml) and 50 μl of MAb (5 μg/ml) were mixed in a well of a microtiter plate. An irrelevant IgM MAb was used as a negative control. After 1 h of incubation, this mixture of bacteria and MAbs was washed and suspended in 100 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse Ig (Sigma). After 1 h of incubation, the bacteria were washed again and fixed by resuspension in 400 μl of PBS containing 0.5% paraformaldehyde. Fluorescence, forward scatter, and side scatter of the bacteria were measured with a flow cytometer (FACScaliber; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.).

TABLE 3.

Bactericidal characteristics of MAbsa

| MAb | Result for complement source with N. meningitidis serogroup (strain)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rabbit

|

Human B (ATCC 13090) | |||||

| A (M239) | B (ATCC 13090) | B (H44/76) | C (BB-305) | Y (S-1975) | ||

| HmenB1 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| HmenB2 | − | +++ | +++ | − | − | +++ |

| HmenB3 | − | +++ | +++ | − | − | +++ |

| HmenB4 | − | ++ | +++ | − | − | − |

| HmenB5 | − | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | +++ |

| HmenB6 | − | +++ | +++ | − | − | + |

| HmenB7 | − | +++ | +++ | − | − | − |

| HmenB8 | − | +++ | +++ | − | − | − |

| HmenB9 | − | +++ | +++ | − | − | ++ |

| HmenB10 | − | +++ | +++ | − | − | +++ |

| HmenB13 | − | +++ | +++ | − | − | +++ |

| HmenB14 | − | +++ | +++ | − | − | +++ |

| Irrelevant antibody | − | − | − | − | − | − |

Bacterial assays were performed in triplicate, and the means of triplicates were used for calculations. −, +, ++, and +++, killing levels of <5, 10 to 40, 40 to 70, and >70%, respectively. The percent killing was calculated as follows: % killing of bacteria = [(CFUcontrol − CFUMAb)/CFUcontrol] × 100. The bactericidal assay was performed at 0.5 μg of MAb per ml and was performed at least two times to determine the reproducibility of the results. Baby rabbit serum was used at the concentration of 2% except for group B strain ATCC 13090. For ATCC 13090, 10 to 20% baby rabbit serum and human serum were used. Rabbit serum before or after heat inactivation did not kill the bacteria to any significant degree.

To test MAbs for binding to the PSA portion of NCAM, CHP-134 cells (21) were stained with MAb for flow cytometry as described below. Five hundred microliters of CHP-134 cell suspension (106 cells/ml) was mixed with 50 μl of MAb solution (10 μg/ml) in a test tube and incubated for 2 h on ice. After washing, the cells were incubated with 100 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig for 1 h at room temperature (RT). After another wash, the cells were resuspended in 400 μl of PBS containing 0.25% formaldehyde. Anti-CD56 (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.), which is specific for NCAM, and isotype-matched irrelevant mouse MAbs were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Fluorescence, forward scatter, and side scatter of the cells were measured with a flow cytometer (FACScaliber).

Bactericidal assay.

The bactericidal assay was performed in 96-well microtiter plates (Corning Inc., Corning, N.Y.) with modifications of a previously described procedure (27). Briefly, 30 μl of bacterial suspension containing 2,500 CFU, 50 μl of appropriately diluted antibiotic-free antibody, and 20 μl of baby rabbit complement or agammaglobulinemic human serum were added to each well. The concentration of complement was 2 to 20% depending on the susceptibility of the bacteria to the complement, and an isotype-matched irrelevant MAb was used as a negative control. Target bacterial strains are listed in Table 1. Two different strains of NMGB (ATCC 13090 and H44/76) were used to avoid killing by binding to antigens that were not capsular PS. After a 1-h incubation with shaking, 10 μl of the reaction mixture was plated on a chocolate agar plate. CFU were determined after an overnight incubation at 37°C in a candle jar. Each assay was performed in triplicate, and the mean of the triplicate was used to calculate the percentage of killing by the formula [(CFUno antibody − CFUsample)/ CFUno antibody] × 100. This assay was repeated at least two times.

Histochemistry.

The staining was performed with the brains obtained from 1- to 2-week-old C57BL/6 mice. Five-micrometer-thick cryosections of the brain were incubated with 1 to 2 μg of MAb/ml for 75 min at RT. The slide was washed with PBS and incubated with biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) for 30 min at RT. The slide was washed again with PBS and incubated with streptavidin-peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory, West Grove, Pa.) for 30 min. The slide was developed with a peroxidase substrate, 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole, from Scy Tek (Logan, Utah) and counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin stain (Poly Scientific, Bayshore, N.Y.).

Production of phage clones expressing the mimotopes.

Two phage libraries from New England Biolabs Inc. (Beverly, Mass.) were used for our study. One contained a linear peptide with 7 amino acids, and the other contained a circular peptide with 7 amino acids between two cysteines. The two cysteines were joined by a disulfide bond to form a circular peptide. The phage library was biopanned with purified MAbs HmenB1, HmenB2, HmenB3, HmenB13, and HmenB14, as described by the manufacturer of the library. Briefly, MAb-coated 60-mm-diameter culture dishes (Nunc) were prepared by incubating the dish with 1.5 ml of 0.1 M NaHCO3 (pH 8.6) containing 100 μg of MAb/ml overnight at 4°C, washing with 0.1% Tween 20–Tris-buffered saline (0.1% TBST; 50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl), and blocking with 0.5% bovine serum albumin in 0.1 M NaHCO3. Phage binding to the MAb was enriched by incubating the phage library in the dish, gently washing away unbound phage, and removing the phage bound to the dish by elution with 0.2 M glycine-HCl (pH 2.2) and rapidly neutralizing the phage with 1 M Tris-Cl (pH 9.1). Bound phage was expanded and subjected to additional cycles of enrichment as described above. After three cycles of enrichment, bound phage was cloned. Individual clones of phage were expanded for further studies.

Binding and competitive binding assays of phage on antibody-coated plates.

Ninety-six-well microtiter plates (Nunc) were coated with MAbs by adding 100 μl of a carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) containing 10 μg of MAb/ml. After an overnight incubation, the plates were washed and blocked with 2% skim milk in PBST. Fourfold serial dilution of the solutions containing amplified phage (1 × 1011 to 10 × 1011 PFU/ml) was performed, and the serially diluted phage was added to the plates. In some cases, to test for the specificity of phage binding to MAb, a serial dilution of E. coli K1 PS (from 1,600 to 0.2 μg/ml) or heat-inactivated NMGB (1.6 × 1010 to 2 × 105 cells/ml) was added to the well along with a fixed number of phage (1010 PFU/ml). After a 1.5-h incubation at RT with gentle agitation, the plates were washed and loaded with peroxidase-labeled antiphage MAb (Pharmacia). One and one-half hours later, the plates were washed and loaded with tetramethylbenzidine (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.). The color development was stopped, and the plates were read at 450 nm.

DNA sequencing of phage peptide motif.

To determine the DNA sequence of the peptide mimotope, phage clones were expanded by growing them in 1-ml E. coli cultures for 4 to 5 h at 37°C. To recover the phage, the bacteria were removed from the culture suspension by a brief centrifugation (10,000 × g for 10 s), 500 μl of the culture supernatant was mixed with 200 μl of 20% polyethylene glycol–2.5 M NaCl solution, and the mixture was centrifuged (10,000 × g) for 10 min. The pellet containing the phage was resuspended with 100 μl of a Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer with iodide (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 4 M NaI) and 250 μl of absolute ethanol. The phage was then washed with 70% ethanol, dried, and resuspended in 30 μl of TE buffer. Five microliters of the phage suspension was subjected to dideoxy termination reactions using a DNA sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.), −96 sequencing primer from New England Biolabs, and AmpliTaq DNA polymerase FS. The sequence of the mimotope was obtained by running the above reaction products through an automated DNA sequencer from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, Calif.).

RESULTS

Characterization of antigens for the MAb.

From five mice immunized with E. coli K1 bacteria (strain RS218), we obtained 12 hybridomas expressing IgM heavy and κ light chain isotypes. Consistent with their selection prior to cloning, these hybridoma antibodies bound to the ELISA plates coated with NMGB bacteria and purified E. coli K1 PS (data not shown). The preparation of E. coli K1 PS was highly purified and was not likely contaminated with other antigens (W. Vann, personal communication). In addition, the 12 hybridoma antibodies bound to EV36 (Table 2), which is an E. coli K-12 strain possessing the genes for K1 capsular PS production (32) and expresses nonacetylated α(2-8) PSA just like NMGB (R. Silver, personal communication). These findings taken together strongly suggest that all the MAbs bind to α(2-8) PSA and/or to a structure invariably associated with the PS (e.g., the lipid anchor of the capsular PS [4, 14]).

TABLE 2.

Binding characteristics of MAbs by flow cytometry

| Fusion no. | MAb name | Binding to:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli EV36a |

N. meningitidis groupa

|

CHP- 134b | |||||

| A | B | C | Y | ||||

| 1 | HmenB1 | + | − | +++ | − | − | + |

| 2 | HmenB2 | + | − | +++ | − | − | − |

| 2 | HmenB3 | + | − | +++ | − | − | − |

| 2 | HmenB4 | ++ | − | − | − | − | ± |

| 2 | HmenB5 | ++ | − | +++ | +++ | − | + |

| 2 | HmenB6 | + | − | +++ | − | − | − |

| 2 | HmenB7 | + | − | +++ | − | − | − |

| 3 | HmenB8 | + | − | +++ | − | − | ± |

| 3 | HmenB9 | ++ | − | +++ | − | − | + |

| 3 | HmenB10 | + | − | +++ | − | − | ± |

| 4 | HmenB13 | ND | − | +++ | − | − | − |

| 5 | HmenB14 | ND | − | +++ | − | − | − |

| Immune mouse serum | ++ | − | ++ | + | − | + | |

Binding of the antibody to the bacteria was determined with flow cytometry. −, ±, +, ++, and +++, <5, 5 to 10, 10 to 40, 40 to 70, and 70 to 100% of bacteria, respectively, displayed fluorescence above threshold levels. Target bacteria were strains S-4185, ATCC 13090, BB-305, and S-1975 for N. meningitidis groups A, B, C, and Y, respectively. ND, not done.

Binding of antibodies to PSA was determined by indirect fluorescence flow cytometry using CHP-134 cells, a PSA-expressing neuroblastoma cell line. +, ±, and −, >30, 15 to 30, and <15% of cells, respectively, were above the threshold.

To test the binding specificities of the MAbs for NMGB bacteria in solution, we examined their binding to N. meningitidis bacteria of groups A, B, C, and Y by flow cytometry (Table 2). All MAbs bound to group B meningococci except for HmenB4. Although it bound to NMGB immobilized on ELISA plates, it did not bind to NMGB in solution even at a high (5- to 10-mg/liter) antibody concentration. The cause of this discrepancy may be technical; the flow cytometric assay may be less sensitive than the ELISA. One hybridoma (HmenB5) bound to group C meningococci as well as to group B meningococci (Table 2). Since group C capsular PS is α(2-9) PSA and group B capsular PS is α(2-8) PSA, the cross-reactive epitope for HmenB5 is likely a part of the two very similar capsular PS and is not likely another bacterial molecule such as outer membrane protein. The remaining 10 MAbs strongly bound only to NMGB without binding to N. meningitidis groups A, C, and Y. Thus, the 10 MAbs are specific for NMGB PS.

Autoreactivities of the MAbs.

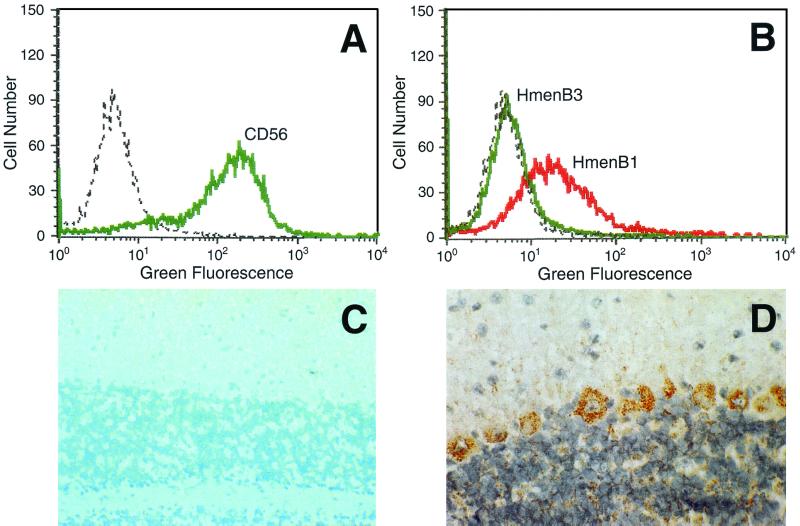

Since antibodies to NMGB PS often cross-react with human α(2-8) PSA expressed in neural tissue, cross-reactivity of our MAbs with human PSA was initially assessed with a human neuroblastoma cell line, CHP-134 (21). CHP-134 expresses NCAM decorated with a 50-mer of PSA (21) and can serve as a source of human PSA antigen. More than 90% of the CHP-134 cells used for our study expressed a marker of NCAM, CD56 (Fig. 1A), indicating that our CHP-134 cells expressed NCAM. Indeed, HmenB1, HmenB4, HmenB5, HmenB8, HmenB9, and HmenB10 had weak or moderate binding to CHP-134 cells at approximately 10 mg/liter (Table 2 and Fig. 1B). However, HmenB2, HmenB3, HmenB6, HmenB7, HmenB13, and HmenB14 did not bind to CHP-134 cells detectably under the conditions used here (Table 2 and Fig. 1B). For instance, HmenB2, HmenB3, HmenB13, and HmenB14 did not bind even at a high concentration (25 mg/liter). Thus, some of the MAbs are specific for the bacterial PSA and do not cross-react with human PSA.

FIG. 1.

(A and B) The number of CHP-134 cells (y axis) versus cellular fluorescence (x axis). (A) CHP-134 cells were stained with anti-CD56 (green line) or no antibody (dotted line). (B) Cells were stained with 25 μg of HmenB1 (red line) or HmenB3 (green line) per ml or no antibody (dotted line). (C and D) A cryosection of 10-day-old mouse brain (cerebellum) was stained with HmenB3 (C) and HmenB1 (D). Positive-staining cells have a brick-red color. Approximate magnifications, ×57 (C) and ×110 (D).

To further delineate the binding of the MAbs to the brain tissue, we examined HmenB1, HmenB3, HmenB13, and HmenB14 for binding to the frozen section of the brain of a newborn mouse. HmenB1 stained scattered cells in the cerebrum and the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum at 2.8 mg/liter (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the other three MAbs (HmenB3, HmenB13, and HmenB14) as well as an IgM MAb binding pneumococcal capsular PS did not stain the brain at similar antibody concentrations (Fig. 1C and data not shown). This finding further supports the conclusion that HmenB3, HmenB13, and HmenB14 are not reactive with α(2-8) PSA produced by the animal neuronal tissues.

Characterization of bactericidal activity of the MAb.

Antibodies may bind to bacteria without promoting the bactericidal activity of complement (15). Thus, the MAbs were tested at the concentrations of 5 and 0.5 mg/liter for killing N. meningitidis group A (M239), B (ATCC 13090 and H44/76), C (BB-305), and Y (S-1975) bacteria in the presence of rabbit or human complement. Similar results were obtained with both antibody concentrations, and results obtained at 0.5 mg/liter are shown in Table 3. No MAbs killed N. meningitidis groups A, C, and Y to any detectable degree even at a high (5-mg/liter) concentration, except for HmenB5. HmenB5, which bound group C meningococci very well, readily killed group C meningococci in the presence of rabbit complement (Table 3).

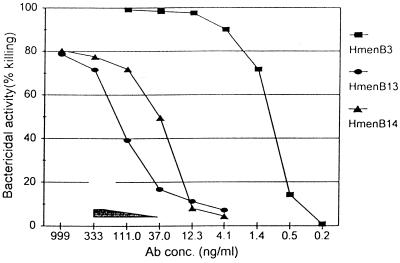

HmenB1 did not kill any NMGB strain with either rabbit or human complement. The remaining 11 MAbs killed more than 70% of two different strains of NMGB (strains ATCC 13090 and H44/76) in the presence of rabbit complement, but their bactericidal efficiency was quite variable. For instance, 1 ng of HmenB3 per ml killed 50% of NMGB (strain ATCC 13090), but 150 ng of HmenB14 per ml and 30 ng of HmenB13 per ml were required to do the same (Fig. 2). Bactericidal efficiencies of HmenB2 and HmenB3 were very similar (data not shown). With human complement, three MAbs (HmenB4, HmenB7, and HmenB8) had undetectable killing activities and two MAbs (HmenB6 and HmenB9) showed only weak bactericidal activity, but six MAbs (HmenB2, HmenB3, HmenB5, HmenB10, HmenB13, and HmenB14) continued to kill NMGB quite effectively (Table 3).

FIG. 2.

Bactericidal activities (y axis) at different concentrations of MAb (x axis). Individual curves show the bactericidal activities against NMGB (ATCC 13090) by HmenB3 (squares), HmenB13 (circles), and HmenB14 (triangles). All the curves showing the bactericidal activities against N. meningitidis groups A (strain M239), C (strain BB-305), and Y (strain S-1975) by the three MAbs are inside the shaded triangle.

Selection of phage clones and analysis of peptide sequence motif.

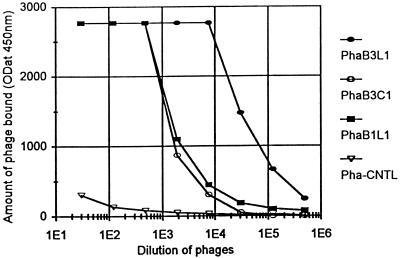

The above data taken together strongly suggested that six MAbs bind to α(2-8) PSA (and/or its associated structures) from NMGB and can promote killing of the bacterium by complement but do not bind the α(2-8) PSA from neural tissue. We therefore chose four (HmenB2, HmenB3, HmenB13, and HmenB14) of the six hybridomas as well as HmenB1 (a negative control) to isolate peptide mimotopes. After three rounds of biopanning a phage library displaying random linear and circular peptides, many phage clones binding to ELISA wells coated with the five MAbs were identified. A randomly chosen irrelevant phage (Pha-CNTL) clone bound poorly to these wells (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

The amount of bacteriophage bound (y axis) to the microwells coated with different MAbs versus various dilutions of phage clones (x axis). Dilution (x axis) indicates fold dilutions, and the optical density (y axis) is expressed in milli-absorbance units. PhaB3L1 (filled circles), PhaB3C1 (open circles), and Pha-CNTL (inverted open triangles) were tested with HmenB3-coated microwells. PhaB1L1 (filled squares) was tested with HmenB1-coated microwells.

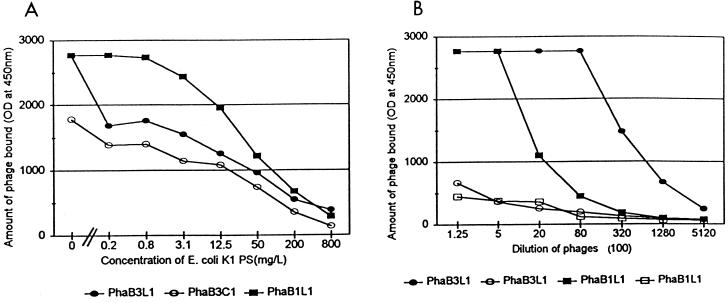

Ninety-two randomly chosen phage clones were subjected to additional binding studies in order to establish the specificity of their binding. All the phage clones bound only to the wells coated with the relevant antibody and did not bind to the wells coated with unrelated antibodies. For instance, PhaB1L1 bound to HmenB1-coated ELISA wells but did not bind to HmenB3-coated wells. PhaB3L1 bound to HmenB3-coated wells but not to HmenB1-coated wells (Fig. 4B). The binding specificity involved PSA since the binding of phage to each MAb was decreased with an increasing amount of purified capsular PS of E. coli K1 as the inhibitor (Fig. 4A) but not with an irrelevant PS. The binding of phage to each MAb was also inhibitable with heat-inactivated group B meningococci (data not shown). These findings indicate that the chosen phage clones specifically bind to the MAbs used for the biopanning.

FIG. 4.

(A) The amount of bacteriophage bound (y axis) to the microwells coated with different MAbs versus various concentrations of E. coli K1 PS in solution (x axis). The optical density (y axis) was expressed in milli-absorbance units. The concentration of phage used for the experiment was 1010 PFU/ml. PhaB3L1 (filled circles) and PhaB3C1 (open circles) were tested with HmenB3-coated microwells. PhaB1L1 (filled squares) was tested with HmenB1-coated microwells. (B) Cross-reactive binding of the phage clones to microwells (y axis) versus the dilution of the phage stocks (x axis). Dilution (x axis) indicates fold dilutions, and the optical density (y axis) is expressed in milli-absorbance units. Individual curves indicate the binding of PhaB3L1 to HmenB3-coated microwells (filled circles), PhaB3L1 to HmenB1-coated microwells (open circles), PhaB1L1 to HmenB1-coated microwells (filled squares), and PhaB1L1 to HmenB3-coated microwells (open squares).

The nucleotide sequence of the inserted DNA of all the cloned phage was determined, and the DNA sequences were translated into amino acid sequences (Table 4). A surprising observation was that the phage clones obtained with HmenB2 and HmenB3 had identical peptide mimotope sequences (data not shown). HmenB2 and HmenB3 were obtained from one fusion, and they could share clonal ancestry (Table 2). To exclude shared clonal ancestry, we determined the DNA sequences of the V regions of these two hybridomas and found them to be identical (data not shown), confirming our suspicion, and the sequence data obtained with the two hybridomas were pooled (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Peptide mimotope sequences of clones of four MAbs

| MAb | Phagea | Peptide sequenceb | No. of clonesc |

|---|---|---|---|

| HmenB1 | PhaB1L1 | DHQRFFV | 5/6 |

| PhaB1L2 | AHQASFV | 1/6 | |

| HmenB3 | PhaB3L1 | SHVPNAF | 23/37 |

| PhaB3L2 | SHAPNAF | 6/37 | |

| PhaB3L3 | SHVPDAF | 4/37 | |

| PhaB3L4 | SHVHNAF | 2/37 | |

| PhaB3L5 | SHAPSAF | 1/37 | |

| PhaB3L6 | SHVPHAF | 1/37 | |

| PhaB3C1 | (C) TGPGSWF (C) | 6/10 | |

| PhaB3C2 | (C) TSPGPWF (C) | 2/10 | |

| PhaB3C3 | (C) TAPGAWF (C) | 1/10 | |

| PhaB3C4 | (C) TTPGPWF (C) | 1/10 | |

| HmenB13 | PhaB13L1 | VVSTGSH | 5/17 |

| PhaB13L2 | IPMKGHW | 1/17 | |

| PhaB13L3 | LPMKYQA | 1/17 | |

| PhaB13L4 | HWGMWSY | 1/17 | |

| PhaB13L5 | ALSSDPH | 1/17 | |

| PhaB13L6 | DPRLSAL | 1/17 | |

| PhaB13L7 | KPSTLML | 1/17 | |

| PhaB13L8 | YHWYTSP | 1/17 | |

| PhaB13L9 | LFMPATP | 1/17 | |

| PhaB13L10 | ALLPWTD | 1/17 | |

| PhaB13L11 | SPPPPPI | 1/17 | |

| PhaB13L12 | SHAPYTH | 1/17 | |

| PhaB13L13 | NQDVPLF | 1/17 | |

| HmenB14 | PhaB14L1 | MELQTRS | 5/22 |

| PhaB14L2 | LPMKYQA | 5/22 | |

| PhaB14L3 | NTLQPSP | 2/22 | |

| PhaB14L4 | YMTPFSP | 2/22 | |

| PhaB14L5 | LHAQSRS | 1/22 | |

| PhaB14L6 | YHLQPTP | 1/22 | |

| PhaB14L7 | HFMEPVN | 1/22 | |

| PhaB14L8 | LSTPSLL | 1/22 | |

| PhaB14L9 | ITAARLP | 1/22 | |

| PhaB14L10 | SIDNPLP | 1/22 | |

| PhaB14L11 | SIITGYL | 1/22 | |

| PhaB14L12 | AYSMLGH | 1/22 |

Phage clones with linear random peptides (L).

Sequences of clones from heptapeptide insert or circular random peptide (C) phage library after third biopanning by HmenB1, HmenB3, HmenB13, and HmenB14.

Number of identical peptide sequences/total number of sequences.

Many phage clones had identical peptide sequences. For instance, six phage clones were chosen with HmenB1, and five of the six clones expressed the sequence of PhaB1L1 (Table 4). Among the phage clones obtained with HmenB3, the SHVPNAH (PhaB3L1) sequence was found in 62% (23 of 37) of the phage clones. Such shared peptide sequences were observed for the phage clones obtained with HmenB13 and HmenB14 as well. VVSTGSH (PhaB13L1) was seen in 31.3% of phage clones obtained with HmenB13. MELQTRS (PhaB14L1) and LPMKYQA (PhaB14L2) each were observed in 22.7% of phage clones obtained with HmenB14.

When the sequences were not identical, the sequences were often very similar, and the similarity could be used to identify consensus peptide sequences. PhaB1L2 shared 4 of the 7 amino acids with PhaB1L1. The shared amino acid sequences were HQ and FV, two polar and two nonpolar groups, respectively. Many phage clones obtained with HmenB3 differed by only 1 or 2 amino acids from each other, and their consensus peptide sequence was S-H-V/A-P/H-X-A-F. The consensus sequence had 2 polar amino acids, 1 nonpolar amino acid, 1 amino acid of either type, 1 polar amino acid, and 2 nonpolar amino acids, in that order. Similarity in the peptide sequences was observed among the phage clones obtained with unrelated MAbs. Peptide sequences of PhaB13L3 and PhaB14L2 are identical, although HmenB13 and HmenB14 were obtained from different fusions and their V regions had different nucleotide sequences (unpublished data). The first 4 amino acids of PhaB13L12 (SHAPYTH) are the same as those of PhaB3L2 and PhaB3L5. Interestingly, the peptide sequences of phage clones obtained with HmenB1 were totally different from those obtained with HmenB3, HmenB13, and HmenB14.

DISCUSSION

Due to the clinical importance of NMGB, the binding specificity of antibodies to its capsular PS has been studied extensively. The antibodies have been found to differ in their abilities to kill NMGB bacteria in the presence of complement, in their binding to NMGB PS of various lengths, and in their cross-reactivities to various antigens including neuronal cells. For instance, Jennings and his colleagues found that N-propionyl derivatization of NMGB reduces the induction of antibodies binding the host NCAM and described the binding specificity diversity among the hybridomas specific for N-propionylated NMGB (27). A recent study by Granoff et al. (15) showed that hybridomas obtained from mice immunized with N-propionylated NMGB differ in complement-dependent killing of NMGB bacteria and binding to NMGB PS. Furthermore, they found that some MAbs are autoreactive since they bind to NCAM expressed on the CHP-134 cell line.

Although our MAbs were obtained by immunizing mice with E. coli K1, they largely reflected the antigen binding pattern described above. We have also obtained several autoreactive hybridomas. For instance, HmenB1 readily bound the CHP-134 cells and the brain tissue. Even though it readily bound to NMGB PS, it was not bactericidal against NMGB. Another autoreactive antibody was found to display unusual binding properties: in addition to binding NMGB, HmenB5 bound to the PS of group C N. meningitidis and killed this bacterium. This type of antibody specificity may be produced with E. coli K92 immunization, but one MAb reported in the literature with the identical binding property was produced with NMGB immunization (20). Group C PS in the meningococcal vaccine used in the U.S. military may elicit this type of cross-reactive antibody, and such an antibody may be responsible for the observed lack of increase in group B serotype outbreaks in the U.S. military (5). The epitope bound by HmenB5 must include the PSA because this MAb binds to the CHP-134 cell line and to purified E. coli K1 PS. Interestingly, the mice carrying the autoreactive hybridomas in their peritoneum did not show any obvious neurological symptoms, consistent with previous observations of patients with a high level of anti-NCAM antibodies due to myelomas or meningococcal infections (25).

In addition to the autoreactive antibodies, however, we also obtained many MAbs recognizing a bacterium-specific epitope(s). The bacterium-specific hybridomas bound to the E. coli strain EV36. This finding indicates that an unrelated (K-12) strain of E. coli can gain the bacterium-specific epitope with the transfer of the gene only for the capsular PS of E. coli K1. Also, the bacterium-specific epitope was present on the purified E. coli K1 PS. These findings strongly support the idea that the bacterium-specific epitope is the capsular PS or a structure invariantly associated with the capsular PS. An example of the invariably associated molecule is a lipid tail, which is used to anchor the capsular PS to the membrane and which is invariably found for the capsular PS of both E. coli and NMGB (4, 14). Also, PS-lipid binds to the ELISA plates much better than does pure PS (C. Frasch, personal communication). Thus, antibodies to PS-lipid would be efficiently detected by the ELISA even though PS-lipid is only a minor contaminant of the purified preparation of PS. The epitope is not likely a protein because the preparation of purified E. coli K1 PS has very little protein contamination (W. Vann, personal communication) and any such protein would have to be conserved among widely different bacteria (E. coli versus N. meningitidis). We are currently investigating the nature of the bacterium-specific epitope further using EV36 variants with mutations in the synthesis or transport of the capsular PS. EV36 is nonpathogenic, and its use greatly simplifies such epitope studies.

These bacterium-specific MAbs differed in their bactericidal potencies. HmenB2 is extremely potent, but some MAbs are not bactericidal at all. All our hybridomas produce IgM antibody, and a possible explanation is that some highly potent antibodies (e.g., HmenB2) may be hexameric IgM. Hexameric IgM has been found to fix complement better (28) and is more frequent among antibodies produced by peritoneal B cells (17), which are often associated with B1 B cells and anti-PS antibodies (16). A more likely possibility is that functional variability resides in the V region of antibodies. The V region differences may result in differences in the avidity or in the recognized epitopes. Two recent studies support the idea that the specificity of the epitope can be critically important for antibody function. Casadevall and his colleagues have found two types of IgM anticryptococcal antibodies (22): one type binds the fungus with a rim-type pattern and is protective, whereas the other type binds it with a puffy-type pattern and is not protective. Another example was shown by Fusco et al., who described an antibody that, in the presence of complement alone, can kill group B streptococcus, which is a gram-positive bacterium and is normally resistant to complement-mediated bacteriolysis (13). To examine the possibilities described above, additional work is in progress.

When the peptide mimotopes of NMGB PS were obtained with the bacterium-specific MAbs, the heterogeneity of their epitopes was readily shown by the mimotope sequences. The mimotopes obtained with one hybridoma readily demonstrate the sequence similarities, and the consensus sequences can be easily identified in some cases. For instance, SHxxxAF is the readily recognizable consensus sequence of HmenB3 mimotopes. Identical mimotope sequences are frequently found among the phage clones independently derived from one selecting MAb. For instance, the PhaB14L1 sequence is expressed in 5 of 22 independent clones selected with HmenB14. In contrast to the mimotopes produced with one selecting antibody, mimotope peptides obtained with different selecting antibodies were quite distinct. For example, amino acids A, F, and H are common for mimotopes only from HmenB3 but amino acids L, M, and Q are common for those from HmenB14. An exception was observed for the phage clones obtained with HmenB2 and HmenB3. The sequences of the mimotopes were often identical, and additional studies (data not shown) found them to have the identical V region sequences (and the two hybridomas must have been obtained from two different B cells sharing the clonal origin). This finding is different from those of Granoff et al., who obtained identical mimotopes using different selecting antibodies with different fine specificities of binding (15). While the reason for this difference is unclear, our study identifies a large number of independent mimotopes that may bind the antigen binding region of the NMGB PS-specific antibodies.

Our mimotope sequences are different from the sequences of the six mimotopes of NMGB PS reported by Moe et al. (23). For instance, R is prominent in their sequences but not in our sequences. R is common among many PS mimotopes and may mimic hydroxyl groups. Their sequences have cysteine, but ours do not. In contrast, amino acids P and S were common for the phage clones from all the hybridomas. An unusual sequence is one in PhaB13L11 which has five P's in succession and likely forms a helix like NMGB PS. We believe, however, that the helices are different since polyproline forms a collagen-like helix with a 9-Å pitch whereas NMGB PSA most likely forms a helix with a 5.5-Å pitch (6). Another interesting phage is PhaB13L4, which has a WSY sequence. The W/YXY sequence motif has been found in the peptide mimics of several PS (31) including group C PS of N. meningitidis, another PSA with an α(2-9) linkage group (33). No other obvious similarities have been observed when our sequences were compared with mimotopes of other PS molecules.

The recent identification of new vaccine candidate molecules (26) has opened a new approach to making a vaccine against NMGB. However, these molecules have not been extensively studied so far, and the prospects for their becoming a successful vaccine are still unclear. In contrast, the capsular PS of NMGB has been extremely well studied, and the antibodies to NMGB PS have been shown to be effective against all strains of NMGB. There is also an increasing body of literature showing that mimotopes can serologically mimic carbohydrate epitopes and elicit antibodies to a variety of PS antigens including group C meningococcal PS (33), cryptococcal capsular PS (D. O. Beenhouwer, P. Valadon, R. May, S. L. Morrison, and M. D. Scharff, FASEB J. 14:A947, 2000), or carbohydrate epitopes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 or respiratory syncytial virus (7) and other PS (2, 31). Thus, we believe that bacterium-specific anti-NMGB PS antibody can be induced with the mimotopes. We are currently investigating the immunogenicity of additional mimotopes and the interaction between the mimotope peptide and the antibody in detail.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Willie Vann, Richard Silver, Carl Frasch, Tanja Popovic, Wendel Zollinger, and Mike Apicella for various bacterial strains and reagents. We also thank Jim Powers for the interpretation of histochemical stains; Carl Frasch for assisting us with various types of information; Evelyn Henderson for secretarial support; and G. Rabinovitch, D. Klein, and J. Treanor for encouragement.

The work was funded by funds from NIH, AI-85334 and AI-45248. M.H.N. was supported in part by NIAID contract NO1 AI-45248.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdillahi H, Poolman J T. Whole-cell ELISA for typing Neisseria meningitidis with monoclonal antibodies. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;48:367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agadjanyan M, Luo P, Westerink M A, Carey L A, Hutchins W, Steplewski Z, Weiner D B, Kieber-Emmons T. Peptide mimicry of carbohydrate epitopes on human immunodeficiency virus. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nbt0697-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ala'Aldeen D D A, Cartwright K A V. Neisseria meningitidis: vaccines and vaccine candidates. J Infect. 1996;33:153–157. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(96)92081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arakere G, Lee A L, Frasch C E. Involvement of phospholipid end groups of group C Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharides in association with isolated outer membranes and in immunoassays. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:691–695. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.691-695.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Artenstein M S, Winter P E, Gold R, Smith C D. Immunoprophylaxis of meningococcal infection. Mil Med. 1974;139:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brisson J, Baumann H, Imberty A, Perez S, Jennings H J. Helical epitope of the group B meningococcal α(2-8)-linked sialic acid polysaccharide. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4996–5004. doi: 10.1021/bi00136a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chargelegue D, Obeid O E, Hsu S-C, Shaw M D, Denbury A N, Taylor G, Steward M W. A peptide mimic of a protective epitope of respiratory syncytial virus selected from a combinatorial library induces virus-neutralizing antibodies and reduces viral load in vivo. J Virol. 1998;72:2040–2046. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2040-2046.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chuong C M, Edelman G M. Alteration in neural cell adhesion molecules during development of different regions of the nervous system. J Neurosci. 1984;4:2354–2368. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-09-02354.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devi S J, Robbins J B, Schneerson R. Antibodies to poly[(2->8)-α-N-acetylneuraminic acid] and poly[(2->9)-α-N-acetylneuramic acid] are elicited by immunization of mice with Escherichia coli K92 conjugates: potential vaccines for groups B and C meningococci and E. coli K1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7175–7179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devlin J J, Panganiban L C, Devlin P E. Random peptide libraries: a source of specific protein binding molecules. Science. 1990;249:404–406. doi: 10.1126/science.2143033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frasch C E. Meningococcal vaccines: past, present and future. In: Cartwright K, editor. Meningococcal disease. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1995. pp. 245–283. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frosch M, Edwards U. Molecular mechanisms of capsule expression in Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B. In: Roth J, Rutishauser U, Troy F A, editors. Polysialic acid, from microbes to man. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhauser Verlag; 1993. pp. 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fusco P C, Perry J W, Liang S M, Blake M S, Michon F, Tai J Y. Bactericidal activity elicited by the beta C protein of group B streptococci contrasted with capsular polysaccharides. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;418:841–845. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1825-3_200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gotschlich E C, Fraser B A, Nishimura O, Robbins J B, Liu T Y. Lipid on capsular polysaccharides of gram-negative bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:8915–8921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granoff D M, Bartoloni A, Ricci S, Gallo E, Rosa D, Ravenscroft N, Guarnieri V, Seid R C, Shan A, Usinger W R, Tan S, McHugh Y E, Moe G R. Bactericidal monoclonal antibodies that define unique meningococcal B polysaccharide epitopes that do not cross-react with human polysialic acid. J Immunol. 1998;160:5028–5036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herzenberg L A, Stall A M, Lalor P A, Sidman C, Moore W A, Parks D R. The LY-1 B cell lineage. Immunol Rev. 1986;93:81–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1986.tb01503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughey C T, Brewer J W, Colosia A D, Rosse W F, Corley R B. Production of IgM hexamers by normal and autoimmune B cells: implications for the physiologic role of hexameric IgM. J Immunol. 1998;161:4091–4097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jennings H J, Gamian A, Ashton F E. N-propionylated group B meningococcal polysaccharide mimics a unique epitope on group B Neisseria meningitidis. J Exp Med. 1987;165:1207–1211. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.4.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jennings H J, Lugowski C. Immunochemistry of groups A, B, and C meningococcal polysaccharide-tetanus toxoid conjugates. J Immunol. 1981;127:1011–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krambovitis E, McIllmurray M B, Lock P A, Holzel H, Lifely M R, Moreno C. Murine monoclonal antibodies for detection of antigens and culture identification of Neisseria meningitidis group B and Escherichia coli K-1. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1641–1644. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.9.1641-1644.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livingston B D, Jacobs J L, Glick M C, Troy F A. Extended polysialic acid chains (n>55) in glycoproteins from human neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:9443–9448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacGill T C, MacGill R S, Casadevall A, Kozel T R. Biological correlates of capsular (Quellung) reactions of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 2000;164:4835–4842. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moe G R, Tan S, Granoff D M. Molecular mimetics of polysaccharide epitopes as vaccine candidates for prevention of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B disease. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;26:209–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nahm M H, Clevinger B L, Davie J M. Monoclonal antibodies to streptococcal group A carbohydrate. I. A dominant idiotypic determinant is located on Vk. J Immunol. 1982;129:1513–1518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nedelec J, Boucraut J, Garnier J M, Bernard D, Rougon G. Evidence for autoimmune antibodies directed against embryonic neural cell adhesion molecules (N-CAM) in patients with group B meningitis. J Neuroimmunol. 1990;29:49–56. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(90)90146-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pizza M, Scarlato V, Masignani V, Giuliani M M, Arico B, Comanducci M, Jennings G T, Baldi L, Bartolini E, Capecchi B, Galeotti C L, Luzzi E, Manetti R, Marchetti E, Mora M, Nuti S, Ratti G, Santini L, Savino S, Scarselli M, Storni E, Zuo P, Broeker M, Hundt E, Knapp B, Blair E, Mason T, Tettelin H, Hood D W, Jeffries A C, Saunders N J, Granoff D M, Venter J C, Moxon E R, Grandi G, Rappuoli R. Identification of vaccine candidates against serogroup B meningococcus by whole-genome sequencing. Science. 2000;287:1816–1820. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pon R A, Lussier M, Yang Q, Jennings H J. N-propionylated group B meningococcal polysaccharide mimics a unique bactericidal capsular epitope in group B Neisseria meningitidis. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1929–1938. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.11.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reddy P S, Corley R B. The contribution of ER quality control to the biologic functions of secretory IgM. Immunol Today. 1999;20:582–588. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01542-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riedo F X, Plikaytis B D, Broome C V. Epidemiology and prevention of meningococcal disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:643–657. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott J K, Smith G P. Searching for peptide ligands with an epitope library. Science. 1990;249:386–390. doi: 10.1126/science.1696028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valadon P, Nussbaum G, Boyd L F, Margulies D H, Scharff M D. Peptide libraries define the fine specificity of anti-polysaccharide antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans. J Mol Biol. 1996;261:11–22. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vimr E R, Aaronson W, Silver R P. Genetic analysis of chromosomal mutations in the polysialic acid gene cluster of Escherichia coli K1. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1106–1117. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.1106-1117.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westerink M A J, Giardina P C, Apicella M A, Kieber-Emmons T. Peptide mimicry of the meningococcal group C capsular polysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4021–4025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]