Background:

Sma-and mad-related protein 7 (SMAD7) can affect tumor progression by closing transforming growth factor-beta intracellular signaling channels. Despite the extensive research on the correlation between SMAD7 polymorphisms and colorectal cancer (CRC), the conclusions of studies are still contradictory. We conducted a study focusing on the association of SMAD7 polymorphisms rs4939827, rs4464148, and rs12953717 with CRC.

Methods:

We searched through 5 databases for articles and used odd ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to discuss the correlation of SMAD7 polymorphisms with CRC risk. The heterogeneity will be appraised by subgroup analysis and meta-regression. Contour-enhanced funnel plot, Begg test and Egger test were utilized to estimate publication bias, and the sensitivity analysis illustrates the reliability of the outcomes. We performed False-positive report probability and trial sequential analysis methods to verify results. We also used public databases for bioinformatics analysis.

Results:

We conclusively included 34 studies totaling 173251 subjects in this study. The minor allele (C) of rs4939827 is a protective factor of CRC (dominant, OR/[95% CI] = 0.89/[0.83–0.97]; recessive, OR/[95% CI] = 0.89/[0.83–0.96]; homozygous, OR/[95% CI] = 0.84/[0.76–0.93]; heterozygous, OR/[95% CI] = 0.91/[0.85–0.97]; additive, OR/[95% CI] = 0.91/[0.87–0.96]). the T allele of rs12953717 (recessive, OR/[95% CI] = 1.22/[1.15–1.28]; homozygous, OR/[95% CI] = 1.25/[1.13–1.38]; additive, OR/[95% CI] = 1.11/[1.05–1.17]) and the C allele of rs4464148 (heterozygous, OR/[95% CI] = 1.13/[1.04–1.24]) can enhance the risk of CRC.

Conclusion:

Rs4939827 (T > C) can decrease the susceptibility to CRC. However, the rs4464148 (T > C) and rs12953717 (C > T) variants were connected with an enhanced risk of CRC.

Keywords: bioinformatics analysis, colorectal cancer, meta-analysis, SMAD7, SNPs

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a global disease with a high incidence and death rate, ranking fourth and fifth among all malignancies.[1] Hereditary genomic alterations have been linked to a person’s chance of acquiring cancer for decades.[2] As a result, research into the genetic variables that influence CRC susceptibility is critical. Sma-and mad-related protein 7 (SMAD7), as a member of the SMAD family, may play a damaging role in the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling pathway by interacting with the mobilization of other SMAD proteins, which indirectly contributes to tumorigenesis.[3] As a critical component in the intracellular signaling shutdown mechanism of transforming growth factor (TGF), it can block the tumor-suppressive function of TGF-β at an early stage of carcinogenesis, such as CRC.[4]

The TGF-β family is strongly associated with development and endocytosis in most tissues. TGF-β family members bind to type II and type I receptors, forming a receptor complex that phosphorylates type I receptors, initiating TGF-β signaling and phosphorylating the made-associated proteins SMAD2 and SMAD3. Later on, phosphorylated SMAD2 and SMAD3 bound to SMAD4 to forge the SMAD4- RSmad complex, which then enters into the nucleus and regulates the transcription of specific target genes with the help of DNA-binding protein chaperones.[4–6] TGF activation inhibits TGF-mediated phosphorylation of SMAD2 and SMAD3 since SMAD7 may connect to the TGF receptor complex but is not phosphorylated.[5]

All 3 polymorphic variants occur on chromosome 18. rs4939827, rs464148 and rs12953717 are located within intron 3 of SMAD7 on chromosome 18q21.[7] Rs4939827 and rs12953717, as 2 adjacent polymorphisms, do not have the same direction of base mutation. Rs4939827 mutates from base T to base C. In contrast, rs12953717 mutates from base C to base T to affect gene expression. rs4464148 has the same direction of base mutation as rs4939827. This irreversible mutation alters the protein structure at the molecular level and thus affects biological function.[8]

Since its discovery, SMAD7 has been widely researched, especially to study its single nucleotide polymorphisms with cancer because of its possible signaling inhibition in the cell nucleus. We found that rs4939827, rs4464148, and rs12953717 polymorphisms were studied more in association with various cancer, which contains colorectal, breast, hepatocellular carcinoma, esophageal, chronic lymphocytic leukemia.[9–12] Among them, CRC is the most. However, many studies have conflicting results. Some studies concluded that SMAD7 variants are not significantly associated with CRC.[13–15] but most of the results indicated the increased risk.[16–18] The inconsistent results might be attributed to a small sample or chance error. Therefore, we included studies of these 3 variants with CRC, providing a more adequate and accurate study of the correlation between SMAD7 polymorphisms and CRC.

2. Materials and methods

Our research has been registered in PROSPERO and the details are available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Since we are not engaged in human or animal experiments, we do not have to submit an ethical application. Our study was closely carried out according to the PRISMA guidelines.

2.1. Search strategy

Studies included in this meta-analysis that met the inclusion criteria were obtained from 5 databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Wan Fang database, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure), with a search time limit of literature published earlier than January 2022. The search strategy incorporated these terms: “Neoplasm,” “tumor,” “cancer,” “malignancy,” “colorectal cancer,” “CRC,” “SNP,” “Polymorphism,” “mutation,” “SMAD7,” “SMAD7 protein,” “rs4939827,” “rs4464148,” “rs12953717,” “case–control study”; the specific search formula can be viewed in the supporting information (See Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD/I297, which shows detailed search strategies). We also reviewed articles about our study by the references cited in the included studies; if feasible, gray literature searched via manual was also included. Two researchers independently searched through the above search strategy and deliberated on inconsistent search results. If necessary, we need a third researcher join us until reaching a consensus. There were no language constraints in this search.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two researchers searched and filtered separately in the specified databases under the same strategy. If discrepant results arose, discussions were held, and a third researcher joined when needed until a consensus was reached.

2.2.1. Inclusion criteria.

Studies can be included only by meeting the following inclusion criteria:

-

(a)

Case–control studies.

-

(b)

evaluating the correlation between SMAD7 loci (rs4464148, rs12953717, rs4939827) and CRC risk, participants in the case group must have malignancy confirmed by pathological methods.

-

(c)

Full text, acquired genotype frequencies existed in both the case and control groups.

2.2.2. Exclusion criteria.

Duplicate literature.

Non-human experiments. In multiple studies with overlapping, duplicate data published, only the most recent or intact study was included.

2.3. Data extraction

The 2 researchers respectively derived some contents from available pieces of literature: first author, country region, year of publication, ethnicity, source of the control group, cancer type, and genotype frequency of case and control groups, genotyping method. The 2 researchers cross-checked the extraction data to avoid any discrepancies. Genotype frequencies in the control group must follow Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). HWE for each study was measured by χ2 test, and P > .05 was consistent with HWE. We will exclude trials that do not conform to HWE.

2.4. Quality assessment

Two investigators assessed the value of included studies under the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, a total score of 9 points. Case–control trials were scored in 3 dimensions: selection, comparability, and exposure. Scores of 5 to 9 were categorized as high quality versus scores of 0 to 4, which were considered low quality (See Table S2, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD/I298, which show the results of literature quality evaluation). In case of differences between the 2 investigators, it was necessary to discuss with a third party until the 3 parties reached an acceptable resolution.

2.5. Statistical analysis

software: Stata 15.1 (http://www.stata.com), trial sequential analysis (TSA) 0.9.5.10 Beta.

2.5.1. Meta-analysis.

The pooled odd ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CIs) were taken to evaluate the relationship between the 3 polymorphisms and CRC in dominant, recessive, homozygous, heterozygous and additive models. We compared the relationship between the value of OR and 1.0 and whether the value 1.0 is in the 95% CI. If the 95% CI contains the value 1.0, then the results will be deemed insignificant.

2.5.2. Heterogeneity analysis and subgroup analysis.

We used Cochran Q test and I-square to assess the level of primary studies’ heterogeneity. a P-value of less than 0.1 or an I-square greater than 50% for the Cochran Q test was defined as significant heterogeneity. Fixed-effects models were adopted to pooled ORs to estimate the relationship between respective models and CRC risk in case of insignificant heterogeneity; otherwise, random-effects models were adopted. We performed a Meta-regression analysis to probe the root of heterogeneity. We conducted subgroup analyses of included studies for ethnicity, sample, and source of control group to further probe the sources of heterogeneity.

2.5.3. Publication bias.

We employed contour-enhanced funnel plots, Begg test, and Egger test to evaluate the risk of publication bias. The publication bias existed if the funnel plot was asymmetric in the white region or the P-value of the Begg test and Egger test was less than .05.

2.5.4. Sensitivity analysis.

Since we included more than 10 studies in each polymorphism, the reliability of the results for single nucleotide polymorphisms could be assessed by the leave-1-out method. We sequentially excluded a case–control study, and the leftover studies were subjected to sensitivity analysis to examine whether there was a discrepancy between the results of the excluded options and the primitive overall result. Some studies may be considered for exclusion if the study statistics compromise the reliability of the results.

2.6. Reliability assessment

We employed the false-positive report probability (FPRP) method for statistical indicators of positivity, which detects the occurrence probability of type 1 errors caused by cumulative meta-analysis. We set the threshold for FPRP at 0.2, calculated statistical power at an odd ratio of 1.5, and allocated a prior probability of 0.1. Results will be considered significant if the FPRP calculated by statistical power, prior probability, and the P-value is less than .2.[19] In addition, we also performed the test sequential analysis strictly according to the TSA user manual[20] and using the latest software (TSA 0.9.5.10 Beta, www.ctu.dk/tsa). All of them are available at www.ctu.dk/tsa. We set the probability of a type 1 error to 0.05, a power of 80%, and a conventional bound of 1.96 (Z = 1.96). The allele models for the 3 polymorphisms were analyzed, and we will consider the inclusion of sample size sufficient when the cumulative Z value crosses the monitor boundary or when the sample size is greater than the required information size.

2.7. Bioinformatics analysis

2.7.1. Protein interactions network analysis.

We use an open-source data site STRING (https://cn.string-db.org/) to analyze SMAD7 concerning its human protein interactions,[21] with data derived from high-throughput experimental data, computer genome prediction, and automated text mining data. In addition, it can also visualize the data into an intelligible gene co-expression network.

2.7.2. Enrichment analysis.

The DAVID database (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) is a bioinformatics database that integrates biological data and analytical tools to provide systematic and comprehensive biofunctional annotation information for the large-scale gene or protein lists.[22] We obtained functional annotation information of SMAD7 co-expressed proteins from it and visualized the data in the bioinformatics platform (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/). A false discovery rate less than 0.05 was statistically significant.

3. Result

3.1. Screening process

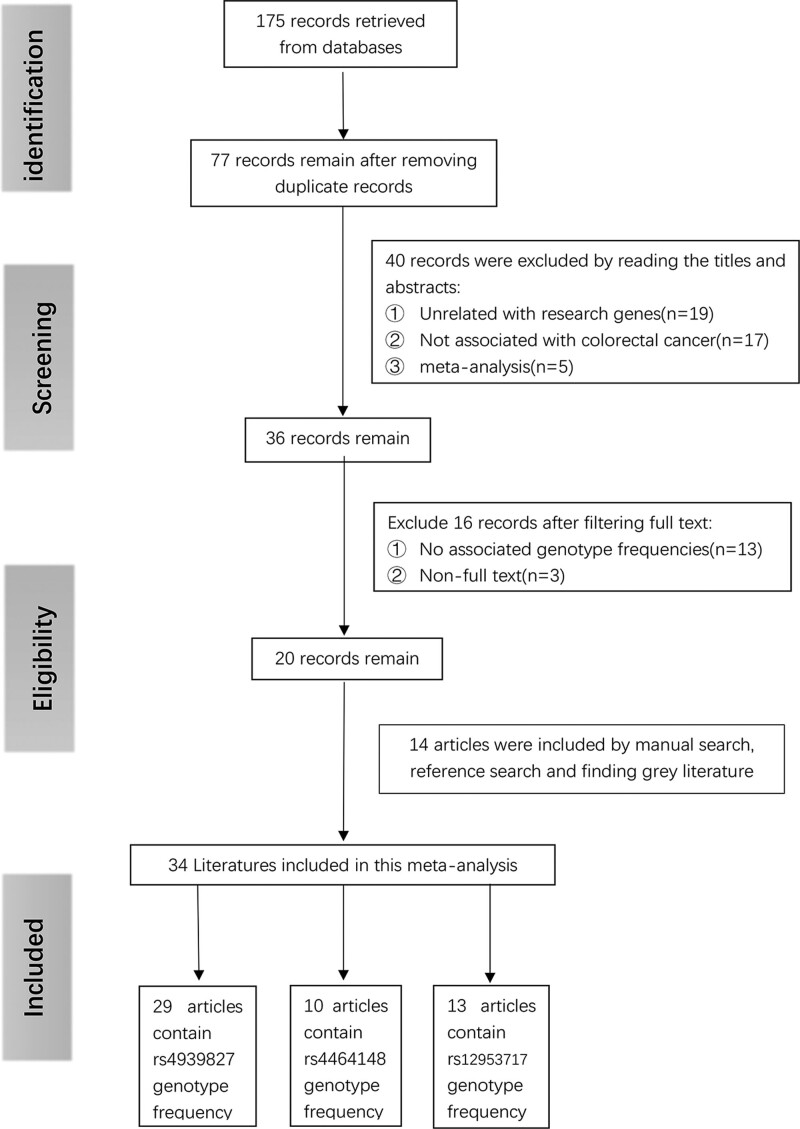

After searching methodically through 5 critical databases, we initially obtained 175 articles. After eliminating 98 repeated articles, 77 left. We then viewed the titles and abstracts and excluded 40 articles, including 19 non-related gene articles, 17 non-colorectal cancer-related articles, and 5 for meta-analysis. We read the remaining 36 papers in full text and excluded 16 articles, of which 3 were non-full-text articles, and another 13 had no relevant genotype frequencies in the text. We then included an additional 14 articles that matched the inclusion criteria by reference search in the remaining articles and other searches, which contains 1 gray literature. A totally of 34 articles were included in the final meta-analysis. After dropping studies that were not eligible for HWE (n = 10), a totally of 62 case–control studies were subsequently incorporated, 37 of which focused specifically on the connection between the rs4939827 and the chance of CRC,[7,8,14–18,23–41] while the number of studies examining the connection between rs4464148 and rs12953717 and CRC risk were 10 and 15, respectively.[7,23–27,29,30,38,39,41–44] The above process can be understood more intuitively from Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature search and screening.

3.2. Characteristics of included studies

As shown in Table 1, we extracted data from the 34 articles, including 80,281 cases and 92,970 controls. The tumors studied in the meta-analysis were limited to CRC, with 21 studies involving Caucasian populations and 10 studies involving Asian populations; there was also 1 study of blacks, and the remainder were mixed population studies. Among the comprehensive case–control studies, 10 studies are not in compliance with HWE (P < .05), and the results were more convincing after removing studies that did not comply with HWE than those that did not; therefore, we excluded the data of these studies. Quality among studies was evaluated via The Newcastle-Ottawa scale; studies all scored more significant than 6, indicating that the contained studies in this article were of high quality.

Table 1.

The primary data information that is extracted from the incorporated articles.

| SNPs | First Author | yr | Country | Ethnicity | Control source | Cancer type | Case | Control | HWE (P) | Genotyping method | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs4939827 | CC/TC/TT | CC/TC/TT | |||||||||

| (T > C) | Broderick | ||||||||||

| -A group | 2007 | UK | Caucasian | NA | colon | 153/449/328 | 229/480/251 | 0.987 | Illumina | 7 | |

| -B group | 2007 | UK | Caucasian | NA | colon | 852/2178/1392 | 845/1915/1084 | 0.989 | Allele-PCR | 7 | |

| -C group | 2007 | UK | Caucasian | NA | colon | 387/982/623 | 410/840/430 | 0.995 | Allele-PCR | 7 | |

| -D group | 2007 | UK | Caucasian | NA | colon | 194/477/292 | 76/171/96 | 0.993 | Allele-PCR | 7 | |

| Tenesa | |||||||||||

| Scotland | 2008 | Scotland | Caucasian | NA | colon | 538/1521/926 | 706/1508/845 | 0.506 | Illumina | 7 | |

| -Japan | 2008 | Japan | Asian | NA | colon | 233/1582/2576 | 131/1028/2019 | 0.992 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| -Canada | 2008 | Canada | Caucasian | NA | colon | 225/593/355 | 284/576/322 | 0.402 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| -England | 2008 | England | Caucasian | NA | colon | 418/1120/694 | 546/1126/578 | 0.959 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| -Spain | 2008 | Spain | Caucasian | NA | colon | 62/156/131 | 57/143/95 | 0.808 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| -Scotland | 2008 | Scotland | Caucasian | NA | colon | 156/420/254 | 189/446/288 | 0.497 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| -Israel | 2008 | Israel | Caucasian | NA | colon | 267/638/447 | 312/627/397 | 0.035 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| -Germany | 2008 | Germany | Caucasian | NA | colon | 420/1071/659 | 541/1057/530 | 0.762 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| -Germany | 2008 | Germany | Caucasian | NA | colon | 289/617/412 | 378/704/358 | 0.403 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| Curtin | 2009 | Multi | Caucasian | PB | colon | 221/520/324 | 229/538/274 | 0.251 | SNPlex | 8 | |

| Thompson | 2009 | US | Mixed | PB | colon | 125/275/154 | 146/378/185 | 0.064 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| Pittman | 2009 | UK | Caucasian | HB | colon | 785/1250/497 | 725/1300/582 | 0.987 | Mixed | 7 | |

| Slattery | 2010 | US | Caucasian | Mixed | colon | 360/773/457 | 492/992/503 | 0.947 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| Xiong | 2010 | China | Asian | PB | colon | 1370/677/77 | 1442/570/74 | 0.060 | PCR-RFLP | 8 | |

| von Hoslt | 2010 | Sweden | Caucasian | HB | colon | 395/886/501 | 387/884/408 | 0.029 | TaqMan | 8 | |

| Kupfer | 2010 | US | African | HB | colon | 379/340/76 | 455/429/101 | 0.993 | MassARRAY | 7 | |

| 2010 | US | Caucasian | HB | colon | 88/199/112 | 85/183/99 | 0.981 | MassARRAY | 7 | ||

| Mates | 2010 | Rome | Caucasian | PB | colon | 28/37/27 | 15/57/23 | 0.042 | Centaurus | 6 | |

| Mates | 2011 | Rome | Caucasian | PB | colon | 42/69/42 | 32/106/43 | 0.018 | Centaurus | 6 | |

| Cui | 2011 | Japan | Asian | PB | colon | 1628/1007/155 | 2247/1190/147 | 0.501 | Illumina | 8 | |

| Li | 2011 | China | Asian | PB | colon | 73/53/12 | 81/73/14 | 0.665 | MassARRAY | 8 | |

| Ho | 2011 | China | Asian | HB | colon | 343/420/129 | 376/405/109 | 0.997 | MassARRAY | 7 | |

| Song | 2012 | China | Asian | HB | colon | 399/232/10 | 732/272/33 | 0.214 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| Lubbe | 2012 | UK | Caucasian | HB | colon | 444/969/624 | 1394/3021/1636 | 0.993 | Allele-PCR | 7 | |

| Garcia-Albeniz | 2012 | US | Caucasian | HB | colon | 90/233/118 | 538/1120/600 | 0.731 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| Phipps | 2012 | US | Caucasian | HB | colon | 657/1526/884 | 574/1597/1112 | 0.988 | Illumina | 7 | |

| Kirac | 2013 | Croatia | Caucasian | PB | colon | 63/143/96 | 172/291/131 | 0.705 | TaqMan | 8 | |

| Yang | 2014 | China | Asian | PB | colon | 342/298/65 | 891/752/159 | 0.985 | MassARRAY | 7 | |

| Kurlapska | 2014 | Poland | Caucasian | PB | colon | 54/93/65 | 716/1394/730 | 0.330 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| Zhang | 2014 | MC | Asian | PB | colon | 400/277/51 | 1894/1170/212 | 0.086 | Mixed | 7 | |

| Hong | 2015 | Korea | Asian | PB | colon | 126/63/9 | 182/127/19 | 0.608 | Illumina | 7 | |

| Baert-Desurmont | 2016 | French | Caucasian | HB | colon | 89/157/104 | 191/493/343 | 0.555 | snapshot | 7 | |

| Abd EI-Fattah | 2016 | Egypt | Caucasian | NA | colon | 20/35/22 | 11/15/10 | 0.319 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| Alonso-Molero | 2017 | MC | Caucasian | PB | colon | 176/524/387 | 495/1185/729 | 0.738 | Illumina | 7 | |

| Shaker | 2018 | Egypt | Caucasian | HB | colon | 13/44/29 | 13/15/8 | 0.367 | Taq Man | 7 | |

| Reilly | 2021 | MC | Caucasian | HB | colon | 9/16/5 | 9/37/14 | 0.061 | Amplifluor | 6 | |

| Alidoust | 2022 | Iran | Caucasian | NA | colon | 89/83/37 | 78/101/16 | 0.330 | ARMS | 7 | |

| rs4464148 | TT/TC/CC | TT/TC/CC | |||||||||

| (T > C) | Broderick | ||||||||||

| -A group | 2007 | UK | Caucasian | NA | colon | 389/425/116 | 486/394/80 | 0.991 | Illumina | 7 | |

| -B group | 2007 | UK | Caucasian | NA | colon | 2017/1952/472 | 1886/1617/346 | 0.982 | Allele-PCR | 7 | |

| -C group | 2007 | UK | Caucasian | NA | colon | 922/845/193 | 827/696/146 | 0.980 | Allele-PCR | 7 | |

| -D group | 2007 | UK | Caucasian | NA | colon | 422/408/99 | 171/137/27 | 0.952 | Allele-PCR | 7 | |

| Thompson | 2009 | US | Mixed | PB | colon | 269/231/61 | 342/324/53 | 0.045 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| Curtin | 2009 | US | Caucasian | PB | colon | 503/472/95 | 535/423/89 | 0.678 | SNPlex | 8 | |

| Pittman | 2009 | UK | Caucasian | HB | colon | 1161/1107/264 | 1095/1277/235 | <0.001 | Mixed | 7 | |

| Ho | 2011 | China | Asian | HB | colon | 739/146/7 | 770/116/4 | 0.869 | MassARRAY | 7 | |

| Zhang | 2014 | MC | Asian | PB | colon | 1/52/675 | 14/305/2957 | 0.045 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| Kurlapska | 2014 | Poland | Caucasian | PB | colon | 1214/1228/400 | 84/96/33 | 0.523 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| Damavand | 2015 | Iran | Caucasian | HB | colon | 138/78/37 | 113/101/20 | 0.700 | PCR-RFLP | 7 | |

| Serrano-fernadez | 2015 | MC | Caucasian | PB | colon | 507/517/141 | 561/490/114 | 0.643 | Taqman | 8 | |

| Reilly | 2021 | MC | Caucasian | HB | colon | 10/16/2 | 27/23/5 | 0.974 | Amplifluor | 6 | |

| rs12953717 | CC/TC/TT | CC/TC/TT | |||||||||

| (C > T) | Broderick | ||||||||||

| A group | 2007 | UK | Caucasian | NA | colon | 159/309/151 | 326/467/167 | 0.991 | Illumina | 7 | |

| B group | 2007 | UK | Caucasian | NA | colon | 1247/2204/973 | 1248/1898/722 | 0.994 | Allele-PCR | 7 | |

| C group | 2007 | UK | Caucasian | NA | colon | 582/991/422 | 558/834/312 | 0.990 | Allele-PCR | 7 | |

| D group | 2007 | UK | Caucasian | NA | colon | 277/468/198 | 106/168/67 | 0.976 | Allele-PCR | 7 | |

| Middeldorp | 2009 | Netherlands | Caucasian | HB | colon | 301/493/201 | 482/643/215 | 0.982 | KASPar | 6 | |

| Curtin | 2009 | US | Caucasian | PB | colon | 314/530/226 | 332/521/188 | 0.509 | SNPlex | 8 | |

| Thompson | 2009 | US | Mixed | PB | colon | 196/248/116 | 220/370/129 | 0.218 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| Pittman | 2009 | UK | Caucasian | HB | colon | 716/1261/555 | 859/1275/473 | 0.998 | Mixed | 7 | |

| Kupfer | 2010 | US | African | HB | colon | 401/327/67 | 525/388/72 | 0.979 | MassARRAY | 7 | |

| 2010 | US | Caucasian | HB | colon | 197/121/81 | 119/180/68 | 0.996 | MassARRAY | 7 | ||

| Slattery | 2010 | US | Caucasian | Mixed | colon | 503/754/332 | 676/928/327 | 0.779 | Illumina | 7 | |

| Li | 2011 | China | Asian | PB | colon | 57/79/6 | 90/63/13 | 0.672 | MassARRAY | 8 | |

| Ho | 2011 | China | Asian | HB | colon | 276/343/97 | 304/345/65 | 0.018 | MassARRAY | 7 | |

| Scollen | 2011 | UK | Mixed | NA | colon | 710/1031/425 | 730/1083/437 | 0.326 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| Zhang | 2014 | China | Asian | PB | colon | 418/263/47 | 1947/1135/194 | 0.096 | TaqMan | 7 | |

| Damavand | 2015 | Iran | Caucasian | HB | colon | 78/90/66 | 68/97/88 | <0.001 | PCR-RFLP | 7 | |

| Lu | 2015 | China | Asian | NA | colon | 401/49/127 | 379/37/169 | <0.001 | PCR-RFLP | 6 | |

| Reilly | 2021 | MC | Caucasian | HB | colon | 9/13/8 | 19/30/11 | 0.889 | Amplifluor | 6 |

Bold indicates that the result of HWE is less than 0.05 (n = 10).

HB = hospital based, HWE = Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, MC = studies in the article were not conducted in the same country or region, mixed (control source) = the control group was derived from both PB and HB, Mixed (ethnicity) = Study subjects belong to two or more races that cannot be grouped together, Multi (country) = multi-center study, NA = the source of the control group was unclear, NOS = The Newcastle-Ottawa scale, PB = population based, SNPs = single nucleotide polymorphisms.

3.3. Meta-analysis findings

Table 2 shows the outcomes of meta-analysis for all snps.

Table 2.

Summary of the correlation between SMAD7 polymorphisms and CRC risk in five models.

| SNPs | Dominant model | Recessive model | Homozygous model | Heterozygous model | Additive model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P/I2 (%) | OR (95% CI) | P/I2 (%) | OR (95% CI) | P/I2 (%) | OR (95% CI) | P/I2 (%) | OR (95% CI) | P/I2 (%) | |

| rs4939827 (T > C) | CC + CT vs TT | CC vs CT + TT | CC vs TT | CT vs TT | C vs T | |||||

| Removel unHWE | 0.89 (0.83,0.97) | <0.01/80.2% | 0.89 (0.83,0.96) | <0.01/78.4% | 0.84 (0.76,0.93) | <0.01/82.6% | 0.91 (0.85,0.97) | <0.01/68.3% | 0.91 (0.87,0.96) | <0.01/84.7% |

| Include unHWE | 0.89 (0.77,1.04) | <0.01/95.5% | 0.91 (0.85,0.97) | <0.01/78.1% | 0.85 (0.77,0.94) | <0.01/81.2% | 0.90 (0.85,0.96) | <0.01/66.6% | 0.94 (0.88,0.99) | <0.01/88.4% |

| Subgroup # | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Caucasian | 0.87 (0.8,0.94) | <0.01/80.3% | 0.87 (0.79,0.95) | <0.01/80.7% | 0.79 (0.7,0.89) | <0.01/85.3% | 0.88 (0.83,0.94) | <0.01/64.3% | 0.89 (0.84,0.95) | <0.01/85.3% |

| Asian | 0.99 (0.82,1.2) | <0.01/71.0% | 0.93 (0.82,1.04) | <0.01/73.2% | 0.98 (0.79,1.21) | <0.01/68.2% | 1.04 (0.88,1.23) | 0.01/60.4% | 0.95 (0.85,1.07) | <0.01/85.1% |

| African | 1.08 (0.79,1.48) | –/– | 1.06 (0.88,1.28) | –/– | 1.11 (0.8,1.54) | –/– | 1.05 (0.76,1.46) | –/– | 1.05 (0.91,1.21) | –/– |

| Mixed | 0.92 (0.71,1.48) | –/– | 1.12 (0.86,1.47) | –/– | 1.03 (0.75,1.42) | –/– | 0.87 (0.67,1.14) | –/– | 1.01 (0.86,1.18) | –/– |

| Control source | ||||||||||

| PB | 0.82 (0.76,0.89) | 0.474/0.0% | 0.90 (0.82,0.99) | 0.014/55.0% | 0.80 (0.71,0.92) | 0.082/40.0% | 0.85 (0.78,0.92) | 0.672/0.0% | 0.9 (0.84,0.96) | 0.016/54.1% |

| HB | 1.09 (0.94,1.27) | <0.01/77.5% | 0.99 (0.85,1.15) | <0.01/82.3% | 1.07 (0.88,1.31) | <0.01/81.6% | 1.05 (0.92,1.19) | <0.01/65.8% | 1.0 (0.9,1.1) | <0.01/84.1% |

| Mixed | 0.77 (0.66,0.89) | –/– | 0.89 (0.76,1.04) | –/– | 0.81 (0.67,0.97) | –/– | 0.86 (0.73,1.00) | –/– | 0.89 (0.82,0.98) | –/– |

| NA | 0.83 (0.75,0.93) | <0.01/84.1% | 0.81 (0.74,0.88) | <0.01/64.6% | 0.73 (0.65,0.83) | <0.01/76.3% | 0.87 (0.79,0.96) | <0.01/77.7% | 0.87 (0.8,0.93) | <0.01/85.3% |

| Sample scale | ||||||||||

| LARGE | 0.90 (0.83, 0.97) | <0.01/82.8% | 0.88 (0.82, 0.95) | <0.01/81.4% | 0.84 (0.76, 0.93) | <0.01/86.9% | 0.92 (0.86, 0.98) | <0.01/73.4% | 0.91 (0.87, 0.96) | <0.01/86.4% |

| SMALL | 0.85 (0.62, 1.18) | <0.01/67.2% | 0.96 (0.74, 1.23) | <0.01/60.8% | 0.82 (0.67, 1.02) | <0.01/70.1% | 0.89 (0.72, 1.1) | <0.01/50.3% | 0.92 (0.7, 1.23) | 0.09/50.2% |

| rs4464148 (T > C) | CC + CT vs TT | CC vs CT + TT | CC vs TT | CT vs TT | C vs T | |||||

| Removel unHWE | 1.17 (1.07, 1.27) | 0.058/45.3% | 1.22 (1.11, 1.22) | 0.404/3.9% | 1.29 (1.17, 1.42) | 0.286/17.1% | 1.13 (1.04, 1.24) | 0.040/48.8% | 1.14 (1.09, 1.29) | 0.100/38.7% |

| Include unHWE | 1.11 (1.00, 1.23) | <0.01/72.1% | 1.23 (1.14, 1.33) | 0.492/0.0% | 1.25 (1.15, 1.36) | 0.220/22.1% | 1.07 (0.95, 1.20) | <0.01/73.7% | 1.12 (1.05, 1.20) | <0.01/63.4% |

| Subgroup # | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Caucasian | 1.15 (1.06, 1.26) | 0.051/48.2% | 1.21 (1.11, 1.33) | 0.34/11.4% | 1.29 (1.17, 1.42) | 0.229/24.2% | 1.12 (1.02, 1.23) | 0.037/51.3% | 1.13 (1.09, 1.18) | 0.102/39.9% |

| Asian | 1.33 (1.02, 1.72) | –/– | 1.75 (0.51, 6.01) | –/– | 1.82 (0.53, 6.25) | –/– | 1.31 (1.01, 1.71) | –/– | 1.32 (1.03, 1.68) | –/– |

| Control source | ||||||||||

| PB | 1.11 (0.95, 1.31) | 0.138/49.5% | 1.11 (0.93, 1.32) | 0.307/15.3% | 1.17 (0.97, 1.41) | 0.156/46.2% | 1.12 (0.97, 1.29) | 0.233/31.4% | 1.10 (1.01, 1.2) | 0.098/56.9% |

| HB | 1.12 (0.72, 1.75) | 0.039/69.3% | 1.69 (1.03, 2.76) | 0.639/0.0% | 1.52 (0.91, 2.55) | 0.894/0.0% | 1.07 (0.59, 1.96) | <0.01/81.3% | 1.17 (0.98, 1.4) | 0.316/13.2% |

| NA | 1.20 (1.09, 1.33) | 0.134/46.3% | 1.24 (1.11, 1.39) | 0.361/6.4% | 1.33 (1.18, 1.49) | 0.162/41.6% | 1.15 (1.07, 1.25) | 0.316/15.2% | 1.14 (1.1, 1.19) | 0.058/56.1% |

| Sample scale | ||||||||||

| LARGE | 1.18 (1.10, 1.27) | 0.151/34.8% | 1.21 (1.10, 1.32) | 0.419/1.3% | 1.27 (1.15, 1.41) | 0.12/40.7% | 1.15 (1.09, 1.23) | 0.379/6.3% | 1.14 (1.1, 1.19) | 0.058/48.6% |

| SMALL | 1.03 (0.49, 2.18) | 0.117/59.4% | 1.67 (0.98, 2.87) | 0.345/0.0% | 1.48 (1.03, 2.11) | 0.94/0.0% | 0.99 (0.35, 2.84) | 0.04/76.2% | 1.03 (0.8, 1.33) | 0.482/38.7% |

| rs12953717 (C > T) | TT + TC vs CC | TT vs CC + TC | TT vs CC | TC vs CC | T vs C | |||||

| Removel unHWE | 1.11 (1.01, 1.22) | <0.01/76.7% | 1.22 (1.15, 1.28) | 0.209/22.0% | 1.25 (1.13, 1.38) | <0.01/55.3% | 1.06 (0.96, 1.18) | <0.01/77.2% | 1.11 (1.05, 1.17) | <0.01/67.0% |

| Include unHWE | 1.08 (0.98, 1.18) | <0.01/76.4% | 1.17 (1.07, 1.28) | <0.01/60.4% | 1.18 (1.05, 1.33) | <0.01/70.9% | 1.06 (0.97, 1.17) | <0.01/73.3% | 1.08 (1.01, 1.15) | <0.01/75.7% |

| Subgroup # | ||||||||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Caucasian | 1.13 (1.01, 1.28) | <0.01/78.1% | 1.26 (1.19, 1.34) | 0.620/0.0% | 1.34 (1.21, 1.48) | 0.053/46.2% | 1.07 (0.94, 1.21) | <0.01/79.1% | 1.14 (1.071.22) | <0.01/66.8% |

| Asian | 1.32 (0.83, 2.11) | 0.048/74.4% | 1.00 (0.73, 1.37) | 0.17/46.9% | 1.08 (0.79, 1.49) | 0.426/0.0% | 1.4 (0.78, 2.53) | 0.017/82.4% | 1.10 (0.97, 1.24) | 0.337/0.0% |

| African | 1.12 (0.93, 1.35) | –/– | 1.17 (0.83, 1.65) | –/– | 1.22 (0.85, 1.74) | –/– | 1.10 (0.91, 1.34) | –/– | 1.1 (0.95, 1.28) | –/– |

| Mixed | 0.92 (0.78, 1.10) | 0.175/45.7% | 1.05 (0.92, 1.20) | 0.306/4.6% | 1.0 (0.86, 1.16) | 0.959/0.0% | 0.88 (0.68, 1.13) | 0.07/69.6% | 0.99 (0.92, 1.07) | 0.739/0.0% |

| Control source | ||||||||||

| PB | 1.09 (0.88, 1.35) | 0.019/70.0% | 1.16 (1.0, 1.34) | 0.406/0.0% | 1.14 (0.97, 1.35) | 0.562/0.0% | 1.08 (0.83, 1.41) | <0.01/78.5% | 1.07 (0.99, 1.16) | 0.363/6.1% |

| HB | 1.0 (0.75, 1.34) | <0.01/88.8% | 1.3 (1.17, 1.44) | 0.698/0.0% | 1.23 (0.97, 1.57) | 0.026/63.7% | 0.93 (0.67, 1.28) | <0.01/89.8% | 1.07 (0.91, 1.25) | <0.01/81.0% |

| Mixed | 1.16 (1.01, 1.34) | –/– | 1.3 (1.09, 1.54) | –/– | 1.36 (1.13, 1.65) | –/– | 1.09 (0.94, 1.27) | –/– | 1.16 (1.06, 1.28) | –/– |

| NA | 1.17 (1.04, 1.32) | 0.015/67.8% | 1.18 (1.10, 1.27) | 0.048/58.3% | 1.28 (1.07, 1.54) | <0.01/74.3% | 1.12 (1.02, 1.23) | 0.132/43.5% | 1.13 (1.04, 1.24) | <0.01/75.2% |

| Sample scale | ||||||||||

| LARGE | 1.17 (1.10, 1.25) | 0.073/42.8% | 1.21 (1.15, 1.28) | 0.339/10.8% | 1.26 (1.13, 1.41) | 0.046/55.7% | 1.12 (1.07, 1.17) | <0.01/0.0% | 1.11 (1.04, 1.17) | <0.01/71.2% |

| SMALL | 0.93 (0.63, 1.4) | <0.01/85.1% | 1.42 (1.03, 1.97) | 0.103/56.1% | 1.21 (1.0, 1.47) | 0.01/60.0% | 0.96 (0.62, 1.47) | <0.01/89.7% | 1.27 (0.94, 1.72) | 0.888/0.0% |

Bold font indicates statistically significant results.

CRC = colorectal cancer, HB = hospital based, HWE = Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, LARGER = the total sample size in the study was greater than 1000, Mixed (control source) = the control group was derived from both PB and HB, Mixed (ethnicity) = Study subjects belong to two or more races that cannot be grouped together, NA = the source of the control group was unclear, PB = population based, SMAD7 = Sma-and Mad-Related Protein 7, SMALL = the total sample size in the study was less than 1000, unHWE = Not in accordance with the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium study.

#, Data for subgroup analysis were obtained from the excluded unHWE study.

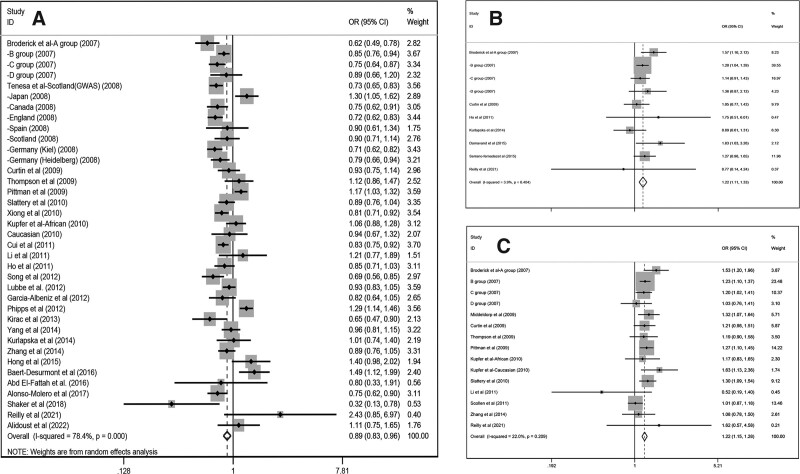

3.3.1. RS4939827 (T > C).

Our research uncovered that C allele of rs4939827 (46,784 cases, 60,938 controls) can reduced the overall CRC risk (dominant, OR/[95% CI] = 0.89/[0.83–0.97]; recessive, OR/[95% CI] = 0.89/[0.83–0.96]; homozygous, OR/[95% CI] = 0.84/[0.76–0.93]; heterozygous, OR/[95% CI] = 0.91/[0.85–0.97]; additive, OR/[95% CI] = 0.91/[0.87–0.96]). All these 5 types of models were analyzed using random effects model because of the significant heterogeneity (Fig. 2A). We in turn proceeded to subgroup analysis by ethnicity, control group source and sample, and the results are shown in Table 2. A detailed subgroup analysis of ethnicity unveiled that rs4939827 was only connected with Caucasians (dominant model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.87/[0.80–0.94]; recessive model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.87/[0.79–0.95]; homozygous model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.79/[0.70–0.89]; heterozygous model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.88/[0.83–0.94]; additive model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.89/[0.84–0.95]) and not with other ethnical groups. For the control source subgroup analysis, we found that this snp was a protective effect against CRC in the population-based groups (recessive model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.90/[0.82–0.99]; additive model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.90/[0.84–0.96]) and unknown source groups (dominant model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.89/[0.75–0.93]; recessive model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.81/[0.74–0.88]; homozygous model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.73/[0.65–0.83]; heterozygous model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.87/[0.79–0.96]; additive model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.87/[0.80–0.93]), but not in the hospital-based and mixed groups.

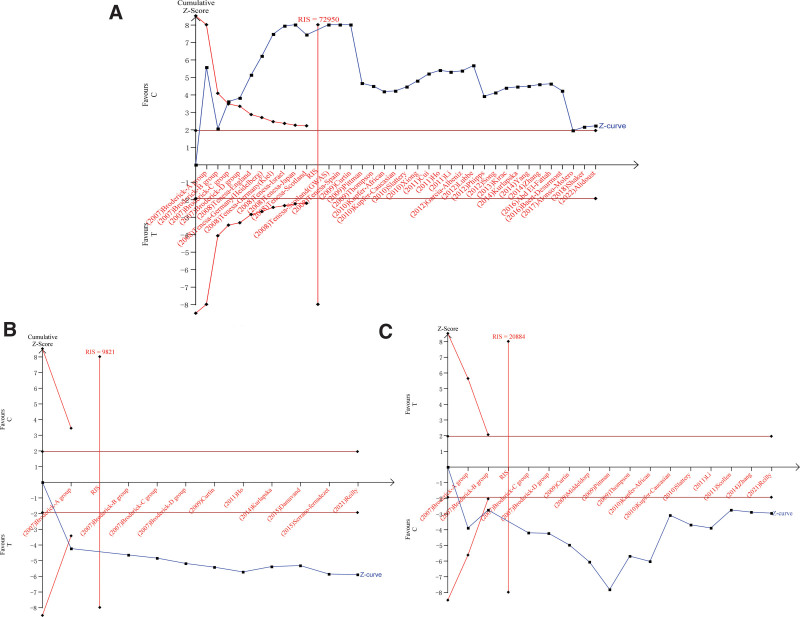

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the recessive model for the correlation between three polymorphisms and CRC susceptibility. (A): Forest plot of the recessive model for rs4939827 polymorphism. (B): Forest plot of the recessive model for rs4464148 polymorphism. (C): Forest plot of the recessive model for rs12953717 polymorphism. CRC = colorectal cancer.

For the sample subgroup analysis, we found that the polymorphism reduced CRC risk in the large sample subgroup (dominant model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.90/[0.83–0.97]; recessive model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.88/[0.82–0.95]; homozygous model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.84/[0.76–0.93]; heterozygous model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.92/[0.86–0.98]; additive model, OR/[95% CI] = 0.91/[0.87–0.96]) compared to the small sample subgroup.

3.3.2. RS4464148 (T > C).

In this part, random effect model was utilized for the dominant and heterozygous model and fixed-effect models for the recessive, homozygous and additive model, and then the results significantly indicated that rs4464148 (14,510 cases,10,417controls) increased the CRC risk (heterozygous, OR/[95% CI] = 1.12/[1.02-1.23], Fig. 2B). We analyzed this polymorphism in 3 subgroups and drew relevant conclusions that allelic mutations from C to T can increase CRC risk in Caucasian populations (dominant, OR/[95% CI] = 1.15/[1.06–1.26]; heterozygous, OR/[95% CI] = 1.12/[1.02–1.23]) but have no impact on Asian races. For control group source subgroup analysis, In the unknown origin group, it also revealed a relationship among rs4464148 and CRC (additive, OR/[95% CI] = 1.14/[1.10–1.19]), The correlation between the snp and CRC was also suggested in the population-based group (additive model, OR/[95% CI] = 1.10/[1.01–1.20]). And the large sample group also suggested a remarkable connection between this gene and CRC (additive model, OR/[95% CI] = 1.14/[1.10–1.19]), all outcomes of subgroup are shown in Table 2.

3.3.3. RS12953717 (C > T).

As for this snp, After collecting and processing the data, we can drag a conclusion that rs12953717 (18,987 cases, 21,615 controls) polymorphism increased risk of CRC (recessive, OR/[95% CI] = 1.22/[1.15–1.28]; homozygous, OR/[95% CI] = 1.25/[1.13–1.38]; additive, OR/[95% CI] = 1.11/[1.05–1.17], Fig. 2C),it indicates that C-allele to T-allele mutations may cause CRC, In further subgroup analyses, this gene polymorphism was statistically related with CRC only in Caucasian populations (dominant, OR/[95% CI] = 1.13/[1.01–1.28]; homozygous, OR/[95% CI] = 1.34/[1.21–1.48]; additive, OR/[95% CI] = 1.14/[1.07–1.22]), for the control source subgroup analysis, we found that unknown source group(dominant, OR/[95% CI] = 1.17/[1.04–1.32]; recessive, OR/[95% CI] = 1.18/[1.10–1.27]; homozygous, OR/[95% CI] = 1.28/[1.07–1.54]; additive, OR/[95% CI] = 1.13/[1.04–1.24]) are related to CRC. The same results can also be derived from the sample subgroup analysis that rs12953717 was regarded as important contributing factors in LARGE group (dominant, OR/[95% CI] = 1.17/[1.10–1.25]; homozygous, OR/[95% CI] = 1.26/[1.13–1.41]; heterozygous, OR/[95% CI] = 1.12/[1.07–1.17]; additive, OR/[95% CI] = 1.11/[1.04–1.17]), while no statistical meaningfulness was found in the SMALL group.

3.3.4. Heterogeneity analysis.

In data integration and analysis, we found that rs4939827 was highly heterogeneous (Ph < 0.01), for which we employed random effects model to pool ORs and perform subgroup analysis, this model is also used in dominant (I-squared = 45.3%, Ph = 0.058) and heterozygous model (I-squared = 48.8%, Ph = 0.040) of rs4464148 and rs12953717 for dominant (I-squared = 76.7%, Ph = 0.01), homozygous (I-squared = 55.3%, Ph = 0.005), heterozygous (I-squared = 77.2%, Ph = 0.01) and additive models (I-squared = 67.0%, Ph = 0.01), Instead, due to low heterogeneity, we applied fixed-effects models to subgroup analyses of the recessive (I-squared = 3.9%, Ph = 0.404), homozygous (I-squared = 17.1%, Ph = 0.286) and additive models (I-squared = 38.7%, Ph = 0.100) in rs4464148 and the recessive model (I-squared = 22.0%, Ph = 0.209) in rs12953717. Since the number of studies on these 3 polymorphisms belonging to SMAD7 exceeded 10, we used meta-regression to probe the root of their heterogeneity, then we found that the heterogeneity of rs12953717 was mainly derived from ethnicity (See Table S3, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD/I299, which show the results of meta-regression analysis of 3 polymorphisms). Although we did not identify any significant sources of heterogeneity in the meta-regressions about rs4939827 and rs4464148, the overall high heterogeneity should not be ignored, so subsequently subgroup analysis by ethnicity, control group source and sample can reveal that the heterogeneity of rs4464148 polymorphism mainly originates from the Caucasian group and hospital-based group of control group source, all subgroups of rs4939827 showed highly heterogeneous.

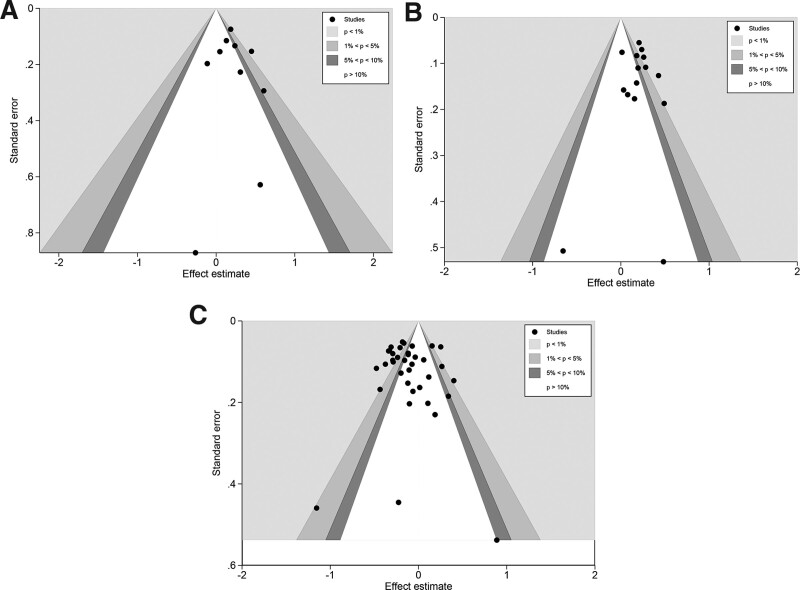

3.3.5. Publication bias.

The publication bias of the 5 models of rs4939827, rs4464148, and rs12953717 was evaluated separately using contour-enhanced funnel plots (Fig. 3), and we can detect noticeable dissymmetry in the funnel plots of dominant, recessive, homozygous, heterozygous, and additive models. However, this asymmetry was due to the distribution of studies in statistically significant regions outside the white of the funnel plot. In our further quantitative analysis of publication bias using Begg test and Egger test, no apparent publication bias was found in each of the 5 models (See Table S4, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD/I300, which show the results of publication bias) for these 3 gene polymorphisms, suggesting that the asymmetry in the funnel plot is caused by factors other than publication bias and most likely is caused by heterogeneity.

Figure 3.

Contour-enhanced Funnel plot of the recessive model for three polymorphisms. (A): contour-enhanced Funnel plot of the recessive model for rs4464148. (B): contour-enhanced Funnel plot of the recessive model for rs12953717. (C): contour-enhanced Funnel plot of the recessive model for rs4939827.

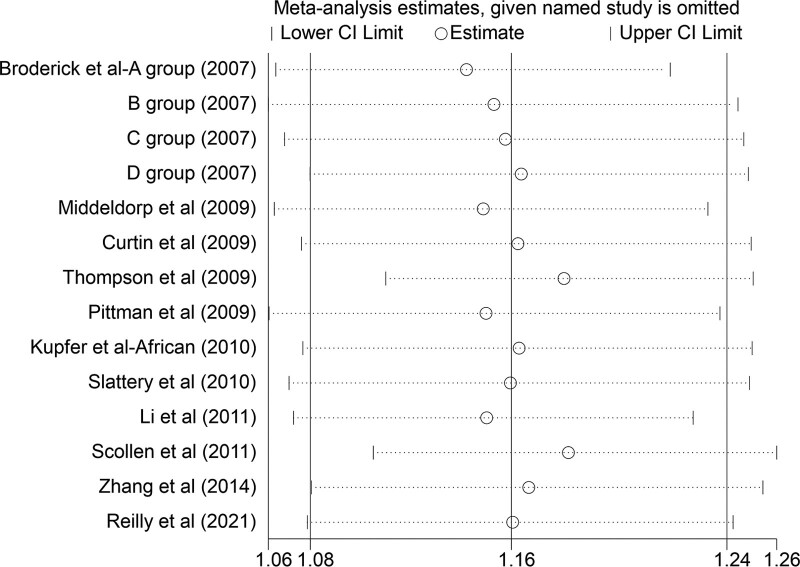

3.3.6. Sensitivity analysis.

We performed sensitivity analyses on the pooled results to assess the individual impact of each study. Removing any of the case–control studies did not result in a change in outcome except for the dominant model in rs12953717, where the results changed after excluding the 1 case–control study, which is the Caucasian group of Kupfer et al (399 cases,367controls). It suggests that this study had a distinctive effect on the results, making the results destabilizing (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Results of sensitivity analysis after excluding one study of the dominant model in rs12953717.

3.4. Result of FPRP analysis and TSA

The results of the false-positive report probability analysis are depicted in Table 3, which contains FPRPs for 3 polymorphisms with statistically significant ORs, all of which are less than 0.2 with an a priori probability of 0.1. It indicates that our results have a low probability of false positives and that our findings are noteworthy. We perform a trial sequential analysis for the allele model, and Figure 5 visualizes the results. We found that the Z curves for all 3 polymorphisms crossed the boundary curves, with cumulative Z values exceeding 1.96 (a = 0.05), and that the sample size exceeded the required information size. These results represent that our included sample size fulfills the sample size we need to draw factual conclusions, proving the reliability of our conclusions.

Table 3.

Result of False-positive probability analysis at six prior probability levels.

| Model | Subgroup | P value | OR (95% CI) | Statistical Power† | Prior probability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.00001 | |||||

| Rs4939827 | ||||||||||

| CC + CT vs TT | Remove HWE | .008 | 0.89 (0.83, 0.97) | 1.000 | 0.023 | 0.067 | 0.441 | 0.888 | 0.988 | 0.999 |

| Caucasian | <.001 | 0.87 (0.8, 0.94) | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.040 | 0.296 | 0.808 | 0.977 | |

| NA | .001 | 0.83 (0.75, 0.93) | 1.000 | 0.004 | 0.012 | 0.116 | 0.570 | 0.930 | 0.993 | |

| LAGER | <.001 | 0.90 (0.83, 0.97) | 1.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| CC vs CT + TT | Remove HWE | .003 | 0.89 (0.83, 0.96) | 1.000 | 0.008 | 0.022 | 0.202 | 0.718 | 0.962 | 0.996 |

| Caucasian | .002 | 0.87 (0.79, 0.95) | 1.000 | 0.006 | 0.017 | 0.159 | 0.657 | 0.950 | 0.995 | |

| PB | .03 | 0.90 (0.82, 0.99) | 1.000 | 0.083 | 0.014 | 0.750 | 0.968 | 0.997 | 1.000 | |

| NA | <.001 | 0.81 (0.74, 0.88) | 1.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.059 | |

| LAGER | .001 | 0.88 (0.82, 0.95) | 1.000 | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.095 | 0.515 | 0.914 | 0.991 | |

| CC vs TT | Remove HWE | <.001 | 0.84 (0.76, 0.93) | 1.000 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.072 | 0.440 | 0.887 | 0.987 |

| Caucasian | <.001 | 0.79 (0.7, 0.89) | 0.997 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.096 | 0.515 | 0.914 | |

| PB | .002 | 0.80 (0.71, 0.92) | 0.995 | 0.005 | 0.016 | 0.148 | 0.638 | 0.946 | 0.994 | |

| NA | <.001 | 0.73 (0.65, 0.83) | 0.917 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.017 | 0.145 | |

| LAGER | <.001 | 0.84 (0.76, 0.93) | 1.000 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.072 | 0.440 | 0.887 | 0.987 | |

| CT vs TT | Remove HWE | .004 | 0.91 (0.85, 0.97) | 1.000 | 0.011 | 0.033 | 0.273 | 0.791 | 0.974 | 0.997 |

| Caucasian | <.001 | 0.88 (0.83, 0.94) | 1.000 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.127 | 0.593 | 0.936 | |

| NA | .006 | 0.87 (0.79, 0.96) | 1.000 | 0.016 | 0.048 | 0.355 | 0.847 | 0.982 | 0.998 | |

| LAGER | .01 | 0.92 (0.86, 0.98) | 1.000 | 0.028 | 0.080 | 0.490 | 0.906 | 0.990 | 0.999 | |

| C vs T | Remove HWE | <.001 | 0.91 (0.87, 0.96) | 1.000 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.052 | 0.354 | 0.846 | 0.982 |

| Caucasian | <.001 | 0.89 (0.84, 0.95) | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.044 | 0.317 | 0.823 | 0.979 | |

| PB | .001 | 0.9 (0.84, 0.96) | 1.000 | 0.004 | 0.012 | 0.120 | 0.579 | 0.932 | 0.993 | |

| NA | <.001 | 0.87 (0.8, 0.93) | 1.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.041 | 0.299 | 0.810 | |

| LAGER | <.001 | 0.91 (0.87, 0.96) | 1.000 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.052 | 0.354 | 0.846 | 0.982 | |

| Rs4464148* | ||||||||||

| CC + CT vs TT | Caucasian | .003 | 1.15 (1.06, 1.26) | 1.000 | 0.008 | 0.024 | 0.212 | 0.730 | 0.964 | 0.996 |

| CT vs TT | Remove HWE | .01 | 1.13 (1.04, 1.24) | 1.000 | 0.029 | 0.082 | 0.495 | 0.908 | 0.990 | 0.999 |

| Caucasian | .018 | 1.12 (1.02, 1.23) | 1.000 | 0.051 | 0.138 | 0.637 | 0.947 | 0.994 | 0.999 | |

| C vs T | Include HWE | .001 | 1.12 (1.05, 1.20) | 1.000 | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.113 | 0.562 | 0.928 | 0.992 |

| PB | .03 | 1.10 (1.01, 1.2) | 1.000 | 0.087 | 0.023 | 0.759 | 0.969 | 0.997 | 1.000 | |

| NA | <.001 | 1.14 (1.1, 1.19) | 1.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| LAGER | <.001 | 1.14 (1.1, 1.19) | 1.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Rs12953717 | ||||||||||

| TT + TC vs CC | Remove HWE | .03 | 1.11 (1.01, 1.22) | 1.000 | 0.084 | 0.015 | 0.751 | 0.968 | 0.997 | 1.000 |

| Caucasian | .05 | 1.13 (1.01, 1.28) | 1.000 | 0.141 | 0.030 | 0.844 | 0.982 | 0.998 | 1.000 | |

| NA | .01 | 1.17 (1.04, 1.32) | 1.000 | 0.031 | 0.088 | 0.515 | 0.915 | 0.991 | 0.999 | |

| LAGER | <.001 | 1.17 (1.10, 1.25) | 1.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.032 | 0.247 | |

| TT vs CC + TC | Include HWE | <.001 | 1.17 (1.07, 1.28) | 1.000 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.057 | 0.381 | 0.860 | 0.984 |

| NA | <.001 | 1.18 (1.10, 1.27) | 1.000 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.092 | 0.504 | |

| TT vs CC | Remove HWE | <.001 | 1.25 (1.13, 1.38) | 1.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.090 | 0.496 |

| Include HWE | .007 | 1.18 (1.05, 1.33) | 1.000 | 0.020 | 0.057 | 0.399 | 0.870 | 0.985 | 0.999 | |

| Caucasian | <.001 | 1.34 (1.21, 1.48) | 0.987 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| NA | .009 | 1.28 (1.07, 1.54) | 0.954 | 0.027 | 0.077 | 0.480 | 0.903 | 0.989 | 0.999 | |

| LAGER | <.001 | 1.26 (1.13, 1.41) | 0.999 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.053 | 0.361 | 0.850 | |

| TC vs CC | LAGER | <.001 | 1.12 (1.07, 1.17) | 1.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.035 |

| T vs C | Remove HWE | <.001 | 1.11 (1.05, 1.17) | 1.000 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.093 | 0.505 | 0.911 |

| Include HWE | .016 | 1.08 (1.01, 1.15) | 1.000 | 0.047 | 0.128 | 0.618 | 0.942 | 0.994 | 0.999 | |

| Caucasian | <.001 | 1.14 (1.07, 1.22) | 1.000 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.132 | 0.604 | 0.939 | |

| NA | .01 | 1.13 (1.04, 1.24) | 1.000 | 0.029 | 0.082 | 0.495 | 0.908 | 0.990 | 0.999 | |

| LAGER | <.001 | 1.11 (1.04, 1.17) | 1.000 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.093 | 0.505 | 0.911 | |

CI = confidence interval, GC = gastric cancer, HWE = Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, LAGER = the total sample size in the study was greater than 1000, NA = control source unknow, OR = odds ratio, PB = population based.

No statistically significant ORs for the recessive and Homozygous models in RS4464148.

The statistical power is measured at an odd ratio of 1.5.

Figure 5.

Results of sample evaluation of three polymorphisms in allelic model. (A) rs4939827; (B) rs4464148; (C) rs12953717.

3.5. Outcome of bioinformation analysis

3.5.1. Protein interactions network analysis.

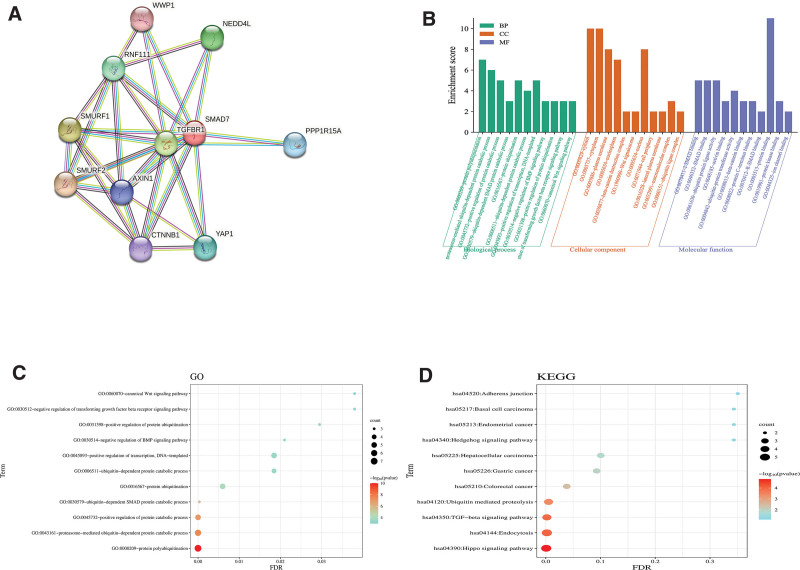

We imaged the SMAD7 gene co-expression network based on the STRING database (Fig. 6A), which displayed us the count and names of genes with strong expression association with SMAD7. These include WWP1, NEDD4L, RNF111, SMURF1, TGFBR1, PPP1R15A, SMURF2, AXIN1, CTNNB1, and YAP1, with a total number of 11.

Figure 6.

Gene relationship network diagram and enrichment analysis results of SMAD7. (A) Gene relationship network diagram of SMAD7. (B) Enrichment of SMAD7-related genes in each gene ontology (GO) term and gene counts. (C) The findings of gene ontology analysis. (D) The findings of Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes analysis. FDR = false discovery rate, GO = gene ontology, KEGG = Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes, SMAD7 = Sma-and mad-related protein 7.

3.5.2. Enrichment analysis.

Figure 6B shows the enrichment score of biological processes, cellular component and molecular function. Enrichment analysis with DAVID yielded 79 gene ontology terms and 11 Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes terms, excluding those with false discovery rate < 0.05, leaving 20 gene ontology terms and 5 Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes terms The bubble size was determined by the number of differential genes contained in the pathway, and the color represents the P-value, the smaller the P-value, the closer to red (Fig. 6C, D).

4. Discussion

SNPs are polymorphisms in DNA sequences caused by discrepancies in 1 base-pairs and such discrepancies include deletions, insertions, and substitutions. Some SNPs located within genes can directly alter protein structure and expression levels.[45] Now that polymorphisms have been intensively studied, researchers have been constantly probing the molecular mechanisms underlying the association of polymorphisms with diseases. Much evidence suggests that they alter an individual’s genetic susceptibility to cancer by regulating gene expression.[46] Mutations are irreversible variants in DNA that essentially include spontaneous or non-spontaneous mutations in the human genome. Most mutations are disease-causing in nature. Since mutations are influenced by both environment and genetics, the distribution of snp and mutations is region-specific and race-specific.[46,47] SMAD7, as an inhibitor of the TGF-β signaling pathway, blocks TGF-β signaling through a negative feedback loop, and due to this inhibitory function, SMAD7 can antagonize a variety of TGF-beta-regulated cellular metabolic processes, for instance, cell proliferation, cell differentiation, apoptosis, adhesion, and migration, then impacting CRC progression.[3,5,48] By including the maximum number of case–control studies to date, this analysis also consistently concluded that both the T allele of rs12953717 and the C allele of rs4464148 increased the risk of CRC whereas high expression of the C allele of rs4939827 reduced the risk of CRC.

A meta-analysis was written by Huang et al in 2016 also came to the non-contradictory conclusion,[49] This article also included substantial case–control studies. However, the analysis of rs4939827 focused on the major gene (T allele) and had problems with the calculation of the HWE, leading to the inclusion of some case–control studies that did not conform to the HWE. In addition, that article did not conduct meta-regression analysis and subgroup analysis to explore the sources of heterogeneity further. Our researchers were fully aware of these shortcomings. The present meta-analysis included as many articles that met the criteria as possible while excluding case–control studies that did not conform to the HWE, which can be said to be the most relevant study with the highest number of cases so far and included 5 more case–control studies than the previous 1 to increase the accuracy of the results. We also reduced selection bias and improved the accuracy of results by searching in Chinese databases and adding gray literature.

Moreover, we found that all of the 3 polymorphisms had heterogeneity in this analysis, so we employed a meta-regression analysis with subgroup analysis by ethnicity, control group source, and sample to find the specific sources of heterogeneity. We found that the heterogeneity of rs12953717 and rs4464148 was principally derived from ethnicity. We further discovered that heterogeneity existed mainly in studies on Caucasian populations; the reasons may be related to the socio-economic situation, food habits, and the wide distribution of ethnic groups, the source of heterogeneity of rs4939827 may be multifaceted, such as the genotyping method of case–control studies, the source of subject recruitment, environmental factors, and dietary habits.[50,51] The asymmetry of contour-enhanced funnel plots for the dominant, recessive, homozygous, heterozygous, and additive models may be associated with heterogeneity, and other results of Begg and Egger test did not find publication bias. For sensitivity analysis, we excluded each of the included studies 1 by 1 before combining effect sizes, and compared the new combined results with the results before the exclusion, and found no significant differences between the results of rs4464148 and rs4939827, which indicates that the results of the analysis of rs4464148 and rs4939827 in this article are robust and credible. In rs12953717, we found that the results changed after removing the Caucasian group of studies in the Kupfer et al study, which suggests that the results of the analysis with the removal of this study would be more credible.

It is worth noting that this meta-analysis also has inadequacies. For instance, we have only 1 study on the African population, and more studies may be needed in the future. The tumor we studied were also constrained to CRC; more research is needed in the future to explore the correlation between SMAD7 polymorphisms and cancer susceptibility further. Although smad7 has been extensively probed, the molecular mechanism of SMAD7 is not fully defined, so it cannot serve the clinic better. We also detected many co-expressed genes through bioinformatic analysis. We can further investigate the role of intracellular signaling pathways and gene co-expression, regarding the elucidation of the role of TGF-β1 signaling in specific pathogenic environments as an important direction for future research; this may pave the way for the development of strategies to modulate these disease processes to develop the most effective therapy plan better for CRC patients.[52]

5. Conclusion

To sum up the above, our study is very relevant. The results of our meta-analysis certified the noticeable relationship of the rs4939827 (T > C) variant with reduced CRC risk. However, the rs4464148 (T > C) and rs12953717 (C > T) variants were significantly correlated with an increased risk of CRC.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the General Science and Technology Program of the Health Commission of Jiangxi Province (202210415).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Qiang Xiao, Guomin Zhu.

Data curation: Jian Chen, Shukun Zeng.

Formal analysis: Qiang Xiao, Jian Chen, Hu Cai.

Funding acquisition: Guomin Zhu.

Resources: Qiang Xiao, Shukun Zeng, Hu Cai.

Software: Jian Chen.

Visualization: Qiang Xiao.

Writing – original draft: Qiang Xiao, Shukun Zeng.

Writing – review & editing: Jian Chen, Jia Zhu, Hu Cai.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations:

- CI =

- confidence interval

- CRC =

- colorectal cancer

- FPRP =

- false-positive report probability

- HWE =

- Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- OR =

- odd ratio

- SMAD7 =

- Sma-and mad-related protein 7

- TGF-β =

- transforming growth factor-beta

- TGF =

- transforming growth factor

- TSA =

- trial sequential analysis

QX, JC and JZ contributed equally to this work.

This work was supported by the General Science and Technology Program of Jiangxi Provincial Health Commission (202210415).

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

How to cite this article: Xiao Q, Chen J, Zhu J, Zeng S, Cai H, Zhu G. Association of several loci of SMAD7 with colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis based on case–control studies. Medicine 2023;102:1(e32631).

Contributor Information

Qiang Xiao, Email: 15007091090@163.com.

Jian Chen, Email: 3150246768@qq.com.

Jia Zhu, Email: DrGming1114@163.com.

Shukun Zeng, Email: 1351631964@qq.com.

Hu Cai, Email: acinel@163.com.

References

- [1].Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sud A, Kinnersley B, Houlston RS. Genome-wide association studies of cancer: current insights and future perspectives. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:692–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nakao A, Afrakhte M, Morén A, et al. Identification of Smad7, a TGFbeta-inducible antagonist of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 1997;389:631–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Massagué J. TGFbeta in cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hayashi H, Abdollah S, Qiu Y, et al. The MAD-related protein Smad7 associates with the TGFbeta receptor and functions as an antagonist of TGFbeta signaling. Cell. 1997;89:1165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Massagué J. TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:753–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Broderick P, Carvajal-Carmona L, Pittman AM, et al. A genome-wide association study shows that common alleles of SMAD7 influence colorectal cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1315–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tenesa A, Farrington SM, Prendergast JG, et al. Genome-wide association scan identifies a colorectal cancer susceptibility locus on 11q23 and replicates risk loci at 8q24 and 18q21. Nat Genet. 2008;40:631–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Seyed-Mehdi H. Relationship between rs6715345 Polymorphisms of MIR-375 gene and rs4939827 of SMAD-7 gene in women with breast cancer and healthy women: a case–control study. Asian Pac J Canc Prev. 2020;21:2479–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jiansong J. SMAD7 loci contribute to risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and clinicopathologic development among Chinese Han population. Oncotarget. 2016;7:22186–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Geng TT, Xun XJ, Li S, et al. Association of colorectal cancer susceptibility variants with esophageal cancer in a Chinese population. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Broderick P, Sellick G, Fielding S, et al. Lack of a relationship between the common 18q24 variant rs12953717 and risk of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:271–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Akbari Z, Safari-Alighiarloo N, Taleghani MY, et al. Polymorphism of SMAD7 gene (rs2337104) and risk of colorectal cancer in an Iranian population: a case–control study. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2014;7:198–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hong SN, Park C, Kim JI, et al. Colorectal cancer-susceptibility single-nucleotide polymorphisms in Korean population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:849–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Amal Ahmed AE-F. Are SMAD7 rs4939827 and CHI3L1 rs4950928 polymorphisms associated with colorectal cancer in Egyptian patients? Tumour Biol. 2016;37:9387–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Alidoust M, Hamzehzadeh L, Khorshid Shamshiri A, et al. Association of SMAD7 genetic markers and haplotypes with colorectal cancer risk. BMC Med Genomics. 2022;15:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Shaker OG, Mohammed SR, Mohammed AM, et al. Impact of microRNA-375 and its target gene SMAD-7 polymorphism on susceptibility of colorectal cancer. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;32:e22215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Alonso-Molero J, González-Donquiles C, Palazuelos C, et al. The RS4939827 polymorphism in the SMAD7 GENE and its association with Mediterranean diet in colorectal carcinogenesis. BMC Med Genet. 2017;18:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wacholder S, Chanock S, Garcia-Closas M, et al. Assessing the probability that a positive report is false: an approach for molecular epidemiology studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:434–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Thorlund K EJ, Wetterslev J, Brok J, et al. User Manual for Trial Sequential Analysis (TSA) [pdf]. 2nd ed. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Trial Unit. 2017:1–119. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Nastou KC, et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:10800D605–10800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sherman BT, Hao M, Qiu J, et al. DAVID: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:W216–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Karen C. Meta association of colorectal cancer confirms risk alleles at 8q24 and 18q21. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:616–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pittman AM, Naranjo S, Webb E, et al. The colorectal cancer risk at 18q21 is caused by a novel variant altering SMAD7 expression. Genome Res. 2009;19:987–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Thompson CL, Plummer SJ, Acheson LS, et al. Association of common genetic variants in SMAD7 and risk of colon cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:982–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kupfer SS, Anderson JR, Hooker S, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in colorectal cancer associations between African and European Americans. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1677–85.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Slattery ML, Herrick J, Curtin K, et al. Increased risk of colon cancer associated with a genetic polymorphism of SMAD7. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1479–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Xiong F, Wu C, Bi X, et al. Risk of genome-wide association study-identified genetic variants for colorectal cancer in a Chinese population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1855–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].J WH. Replication study of SNP associations for colorectal cancer in Hong Kong Chinese. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:369–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Li X, Yang X-x, N-y H, et al. A risk-associated single nucleotide polymorphism of SMAD7 is common to colorectal, gastric, and lung cancers in a Han Chinese population. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:5093–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].R C. Common variant in 6q26-q27 is associated with distal colon cancer in an Asian population. Gut. 2011;60:799–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lubbe SJ, Whiffin N, Chandler I, et al. Relationship between 16 susceptibility loci and colorectal cancer phenotype in 3146 patients. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:108–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Phipps AI, Newcomb PA, Garcia-Albeniz X, et al. Association between colorectal cancer susceptibility loci and survival time after diagnosis with colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:51–54.e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Song Q, Zhu B, Hu W, et al. A common SMAD7 variant is associated with risk of colorectal cancer: evidence from a case–control study and a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kirac I, Matošević P, Augustin G, et al. SMAD7 variant rs4939827 is associated with colorectal cancer risk in Croatian population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Xabier G-A. Phenotypic and tumor molecular characterization of colorectal cancer in relation to a susceptibility SMAD7 variant associated with survival. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:292–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Yang CY, Lu RH, Lin CH, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with colorectal cancer susceptibility and loss of heterozygosity in a Taiwanese population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zhang B, Jia W-H, Matsuo K, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a new SMAD7 risk variant associated with colorectal cancer risk in East Asians. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:948–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kurlapska A, Serrano-Fernández P, Baszuk P, et al. Cumulative effects of genetic markers and the detection of advanced colorectal neoplasias by population screening. Clin Genet. 2015;88:234–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Stéphanie B-D. Clinical relevance of 8q23, 15q13 and 18q21 SNP genotyping to evaluate colorectal cancer risk. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:99–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Reilly F, Burke JP, Lennon G, et al. A case–control study examining the association of smad7 and TLR single nucleotide polymorphisms on the risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23:1043–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Scollen S, Luccarini C, Baynes C, et al. TGF-beta signaling pathway and breast cancer susceptibility. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1112–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Damavand B, Derakhshani S, Saeedi N, et al. Intronic polymorphisms of the SMAD7 gene in association with colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:41–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Serrano-Fernandez P, Dymerska D, Kurzawski G, et al. Cumulative small effect genetic markers and the risk of colorectal cancer in Poland, Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:204089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Brookes AJ. The essence of SNPs. Gene. 1999;234:177–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Yang W, Zhang T, Song X, et al. SNP-target genes interaction perturbing the cancer risk in the post-GWAS. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:5636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Jing L, Su L, Ring BZ. Ethnic background and genetic variation in the evaluation of cancer risk: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Briones-Orta MA, Tecalco-Cruz AC, Sosa-Garrocho M, et al. Inhibitory Smad7: emerging roles in health and disease. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2011;4:141–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Yongsheng H. SMAD7 polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of case–control studies. Oncotarget. 2016;7:75561–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Jin Q, Shi G. Meta-analysis of SNP-environment interaction with heterogeneity. Hum Hered. 2019;84:117–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP. Meta-analysis methods for genome-wide association studies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:379–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Stolfi C, Troncone E, Marafini I, et al. Role of TGF-beta and Smad7 in gut inflammation, fibrosis and cancer. Biomolecules. 2020;11:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.