Abstract

Background:

Native Americans living in rural areas often rely upon wood stoves for home heating that can lead to elevated indoor concentrations of fine particulate matter (PM2.5). Wood stove use is associated with adverse health outcomes, which can be a particular risk in vulnerable populations including older adults.

Objectives:

We assessed the impact of portable air filtration units and educational approaches that incorporated elements of traditional knowledge on indoor and personal PM2.5 concentrations among rural, Native American elder households with wood stoves.

Methods:

EldersAIR was a three-arm, pre-post randomized trial among rural households from the Navajo Nation and Nez Perce Tribe in the United States. We measured personal and indoor PM2.5 concentrations over 2-day sampling periods on up to four occasions across two consecutive winter seasons in elder participant homes. We assessed education and air filtration intervention efficacy using linear mixed models.

Results:

Geometric mean indoor PM2.5 concentrations were 50.5 % lower (95 % confidence interval: −66.1, −27.8) in the air filtration arm versus placebo, with similar results for personal PM2.5. Indoor PM2.5 concentrations among education arm households were similar to placebo, although personal PM2.5 concentrations were 33.3 % lower for the education arm versus placebo (95 % confidence interval: −63.2, 21.1).

Significance:

The strong partnership between academic and community partners helped facilitate a culturally acceptable approach to a clinical trial intervention within the study communities. Portable air filtration units can reduce indoor PM2.5 that originates from indoor wood stoves, and this finding was supported in this study. The educational intervention component was meaningful to the communities, but did not substantially impact indoor PM2.5 relative to placebo. However, there is evidence that the educational interventions reduced indoor PM2.5 in some subsets of the study households. More study is required to determine ways to optimize educational interventions within Native American communities.

Keywords: Biomass burning, PM2.5, Indoor air pollution, Native American health, Rural health

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Wood fuel burning is a common practice for indoor heating in many rural areas of the United States (US) and can lead to high levels of indoor air pollution. Approximately 13 million US homes burn wood fuel, often in old and inefficient wood stove models, as a primary or secondary heating source (EPA, 2013; U.S. Energy Information Agency, 2015). Concentrations of indoor fine particulate matter (PM2.5; airborne particles <2.5 μm in aerodynamic diameter) of 20 to 50 μg/m3 have previously been measured in wood stove households across rural areas of the US (Noonan et al., 2012a; Semmens et al., 2015; Singleton et al., 2017; Walker et al., 2021; Ward and Noonan, 2008). Such elevated concentrations of indoor air pollution have the potential to adversely impact health, particularly in vulnerable populations such as children, older adults, and those with pre-existing health conditions (Sigsgaard et al., 2015).

Native Americans collectively experience among the most severe health disparities and environmental health concerns compared to other populations in the US (Barnes et al., 2010; Holm et al., 2010; MacDorman, 2011). In many rural areas of the US (including areas of the Nez Perce and Navajo Reservations), there are limited alternatives to burning wood for home heating. Many rural areas have no existing natural gas pipelines, and the costs of heating oil or other fossil fuels in rural areas make them impractical alternatives. Wood burning also has cultural and traditional relevance in many Native and rural areas. Evidence linking wood stove-generated PM2.5 with chronic respiratory conditions specifically in American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) adults is lacking. However, the use of wood stoves for heating is common throughout both the Nez Perce and Navajo Reservations, and we have shown that indoor PM2.5 concentrations are elevated in these settings (Semmens et al., 2011; Walker et al., 2021; Ward et al., 2011). In addition to elevated indoor PM2.5 exposures, Native American communities suffer from higher than average prevalence of asthma (Rhodes et al., 2004; Washington Department of Health, 2012) and mortality from influenza, pneumonia, and diabetes (Indian Health Service, 2013). Importantly, some of these co-morbidities are risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (de Marco et al., 2011) and may result in increased susceptibility to the health effects of PM2.5.

Higher-efficiency wood stove upgrade programs (i.e. “wood stove changeouts”) have been implemented in an effort to reduce wintertime ambient air pollution in communities with high wood stove use; however, wood stove upgrades are costly, difficult to implement on a large scale, and may not consistently lead to meaningful improvements in indoor air quality (Allen et al., 2009; Noonan et al., 2012a; Noonan et al., 2012b; Ward et al., 2011; Ward et al., 2010). In contrast, portable air filtration units and educational programs focused on best-burn practices may be more feasible for widespread distribution. Many, although not all, previous studies have found that portable air filters reduce indoor PM2.5 in homes heated with wood stoves (Allen et al., 2011; Cheek et al., 2020; Hart et al., 2011; Wheeler et al., 2014). In a pre-post randomized trial our research group previously reported that wood stove homes with portable air filters had 66 % lower indoor PM2.5 compared to placebo homes with no air filter (McNamara et al., 2017; Ward et al., 2017). However, in a subsequent post-only study that assessed air filtration interventions in rural wood stove homes, we did not find meaningful differences in indoor PM2.5 in the intervention arm relative to control (Walker et al., 2022). Educational best-burn practices have been recommended by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to reduce emissions from residential wood stoves (EPA, 2021). However, development and testing of educational strategies is limited, and there is no evidence in the context of randomized trials to indicate that such practices effectively reduce indoor PM2.5 in wood stove households (Walker et al., 2022). Further assessment of both air filtration and educational interventions in wood stove households is needed to inform community-based strategies for reducing indoor exposures to wood smoke.

To address these questions, two rural Native American communities were engaged in a program that included both a community-wide program and a randomized household-level intervention strategy. Each community had an existing wood delivery program primarily for elders that used wood stoves for heating. The communities were provided with additional resources to augment their ability to acquire, process, store and deliver high-quality, seasoned wood to homes. For the randomized, household-level trial, Residential Wood Smoke Interventions Improving Health in Native American Populations (EldersAIR), we introduced two intervention arms to improve indoor and personal concentrations of PM2.5 among wood-burning homes. Reported here are the findings from this household-level randomized trial of educational and air filtration interventions in communities from the Navajo Nation (NN) and Nez Perce Tribe (NPT) in the Western US.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

EldersAIR was a randomized, placebo-controlled intervention trial among rural Native American households that used wood stoves as a primary heating source. The aims of the trial were to reduce indoor and personal concentrations of PM2.5 and improve health outcomes of blood pressure and pulmonary function tests among elders over 50 years of age. The three study treatment arms were assigned at the household level and included an educational intervention focused on best-burn practices (Education arm), a portable air filtration unit intervention (Filtration arm), and a placebo-controlled group (Placebo arm). Participation occurred across two consecutive winter seasons; interventions were implemented prior to the second winter of 8observation, following a pre-post design with baseline (Winter 1) and post-intervention (Winter 2) periods of observation. Participants were recruited over a 5-year study period (2014–2018), with households that began during the same winter season considered part of the same study cohort (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at baseline (Winter 1).

| All participants (Total n = 149) |

Placebo (Total n = 47) |

Filtration (Total n = 47) |

Education (Total n = 49) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Participant sex | ||||

| Female, n (%) | 105 (70) | 31 (66) | 33 (70) | 36 (73) |

| Male, n (%) | 44 (30) | 16 (34) | 14 (30) | 13 (27) |

| Participant race | ||||

| AI/AN, n (%) | 144 (97) | 47 (100) | 43 (91) | 48 (98) |

| Asian, n (%) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| >1 race, n (%) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | 1 (2) |

| Participant ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic, n (%) | 5 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 3 (6) |

| Not Hispanic, n (%) | 144 (97) | 46 (98) | 46 (98) | 46 (94) |

| Participant education | ||||

| <High school, n (%) | 27 (18) | 11 (23) | 5 (11) | 11 (22) |

| High school, n (%) | 46 (31) | 13 (28) | 16 (34) | 13 (27) |

| Some college, n (%) | 52 (35) | 17 (36) | 18 (38) | 15 (31) |

| College degree, n (%) | 24 (16) | 6 (13) | 8 (17) | 10 (20) |

| Participant age (years) | ||||

| n | 148 | 46 | 47 | 49 |

| mean (sd) | 69.6 (9.2) | 68.9 (8.7) | 69.8 (9.5) | 69.8 (9.3) |

| min, median, max | 51, 69, 98 | 52, 66, 93 | 55, 70, 98 | 51, 69, 89 |

| Participant cohort (1st winter of participation) | ||||

| 2014–2015, n (%) | 12 (8) | 4 (9) | 4 (9) | 4 (8) |

| 2015–2016, n (%) | 25 (17) | 8 (17) | 8 (17) | 9 (18) |

| 2016–2017, n (%) | 38 (26) | 11 (23) | 13 (28) | 13 (27) |

| 2017–2018, n (%) | 43 (29) | 14 (30) | 13 (28) | 13 (27) |

| 2018–2019, n (%) | 31 (21) | 10 (21) | 9 (19) | 10 (20) |

n = number of homes or observations; sd = standard deviation; min = minimum; max = maximum; AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native.

2.2. Randomization and treatment arms

Treatment arm assignment was stratified on cohort (year of enrollment) nested within study area (NN and NPT). Randomization took place within blocks of three households in each stratum as households were enrolled. Intervention arms were similar to those used in a previous randomized trial of wood stove households (Noonan et al., 2019). Briefly, the Education arm households received a community-adapted educational intervention that included methods for optimally treating (i.e. drying) and burning wood fuel. Tools were provided to participants, including moisture meters to measure fuel moisture, fire starters to facilitate the rapid lighting of the fire, and wood stove thermometers to ensure that the wood stoves were burning at optimal temperatures. For the purposes of this paper, the Education arm tools are combined and not evaluated separately. Additionally, participants watched short, culturally-relevant digital stories that were developed by our team prior to the post intervention winter (Winter 2). These short videos stressed the most important factors related to best-burn practices, including using low-moisture fuels and burning their wood stove at optimal temperatures. Filtration arm households received a portable air filtration unit (Filtrete FAP03 and FAP02, 3M Company, USA; Winix 5500 and 5300, Winix America Inc., USA) and were instructed to operate the unit continuously on the “high” setting in the same room as the wood stove. The Filtrete unit was chosen based on its ideal combination of price, availability, clean air delivery rate (CADR), and ratings for larger room sizes. However, production of the Filtrete unit was discontinued prior to completion of the EldersAIR study, so the Winix models were selected based on comparable price and CADR relative to the Filtrete unit (CADR for smoke = 197 and 232, respectively). Placebo households used a sham filtration unit (i.e. with no filter inside the unit) in the same room as the wood stove and were also instructed to leave the unit running continuously on the high setting. Study coordinators assessed the air filtration units during household visits to ensure they were turned on, running at the desired setting, and filters were replaced as needed (i.e. when the “change filter” light came on).

2.3. Recruitment, eligibility criteria, and informed consent

The EldersAIR study took place in rural parts of the Four Corners region of the US (Navajo Nation) and the Nez Perce Reservation in the US state of Idaho. Wood burning is common in both of these regions, particularly for heating purposes during winter months. We aimed to recruit 63 households per study area, or 21 households per treatment arm within each study area, for a total of 126 households. The target sample size was based on a combination of previous literature, power calculations, and feasibility following recommendations from community partners. Recruitment strategies varied by study area. NPT households were recruited from an existing NPT Senior Wood Delivery Program that was administered by the NPT Forestry and Fire Management Division with household eligibility determined by the Social Services Division. For the NN community, recruitment occurred through chapter houses, word of mouth, and through other community event forums. All households with a resident 50 years of age or older that used a wood stove as a primary heating source were considered for inclusion in the study. Based on community-informed input, households were not excluded from participation if a household member smoked tobacco products. Participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. Participants were also compensated for the time they spent performing study tasks and reimbursed for the cost of electricity to use the air filtration units. Following the study, all households received the educational tools and the air filtration units used in the Education and Filtration study arms. The EldersAIR study was approved by the University of Montana IRB, the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board, and the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee. The EldersAIR trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under trial number NCT02240069.

2.4. Exposure assessment

We measured continuous, real-time mass concentrations of PM2.5 over 2-day sampling periods at 60-second time intervals using light-scattering aerosol monitors (DustTrak 8530, TSI, USA). Up to four of the 2-day sampling sessions were conducted at each household, with two sessions taking place during the pre-intervention (Baseline) winter and two sessions during the post-intervention winter. The DustTrak instruments were placed 1 to 1.5 m above ground level in the same room as the wood stove in each household. Instruments were cleaned and zero calibrated according to manufacturer standards prior to each sampling event. Since the indoor PM2.5 sampling was conducted near the wood stoves in the participant households, our assumption was that wood smoke was the primary source of indoor PM2.5 during sampling. We used a source-specific wood smoke correction factor of 1.65 that was developed specifically for DustTrak instruments collocated alongside reference monitors during wood smoke events (McNamara et al., 2011). Specifically, DustTrak PM2.5 concentrations were divided by 1.65 prior to analysis. DustTraks were also collocated with a certified BAM 1020 Continuous Particulate Monitor (Met One Instruments, Inc., USA) to assess performance prior to field deployment and were factory calibrated as necessary.

In addition to indoor PM2.5 concentrations using the DustTrak, we measured personal PM2.5 concentrations for each study participant using a continuous personal PM2.5 monitor (MicroPEM v3.2, RTI International, USA). Personal PM2.5 sampling occurred for 48-hour periods during up to four household visits simultaneous to the indoor PM2.5 sampling. If there were multiple participants in a household, personal PM2.5 was sampled for each participant. Participants were instructed to wear the MicroPEM instruments near their breathing zone throughout the sampling period. An accelerometer (Zip, Fitbit, Inc., USA) was attached to each MicroPEM during sampling to track minutes of participant activity, steps, and distance walked per day while wearing the monitor.

DustTrak and MicroPEM PM2.5 data were assessed for quality by checking descriptive statistics (n, minimum [min], mean, standard deviation [sd], median, maximum [max]), gaps in sampling or missing observations, and by visually inspecting a time-series plot of the PM2.5 concentrations following each sampling session. Data from 45 DustTrak sampling sessions (9.6 %) were excluded from analysis due to apparent instrument malfunction that resulted in extremely high minimum values (n = 4), a large proportion of negative values (n = 4), or sampling sessions <80 % of the expected duration (n = 37). MicroPEM data from the NN study area were excluded from the analysis entirely due to consistent instrument malfunctions and missing data issues. For the NPT study area, MicroPEM data from 16 sampling sessions (6.4 %) were excluded from analysis due to a large proportion of negative values (n = 7) or sampling sessions <80 % of the expected duration (n = 9).

2.5. Covariates

Study coordinators administered questionnaires to participants at the beginning of each winter season to collect information on demographic and household characteristics. Demographic characteristics included participant age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, and household income. Household characteristics included number of levels in the home, size of the home (square meters), number of pets in the home, age of the home, and whether or not any residents smoked inside or outside the home. We used Kill A Watt devices (P3 International Corporation, USA) in each household to measure kilowatt use by the air filtration units; measures of compliance were based on percent expected kilowatt use compared to laboratory tests for each filter unit/setting.

The overall quality of the wood stoves was assessed by participant-reported age of the stoves and whether or not the stove was an EPA certified model. We also implemented a wood stove quality grading method that has previously been utilized during wood stove studies in our group (Walker et al., 2021). An expert, independent wood stove consultant who was blinded to study site and intervention assignment assessed photos of a given household’s wood stove, stovepipe, chimney, and wood storage. Each stove was assigned a grade of high-, medium-, or low-quality based on the wood supply, the stove and chimney system, and the operation and maintenance of the stove. In addition, participants self-reported wood stove practices during a typical winter season, including primary wood collection method (i.e. purchase, harvest, or a local wood delivery program), the length of time they allowed the wood to dry prior to burning, and time since the chimney was last cleaned. Participants self-reported stove use during the PM2.5 sampling periods compared to a typical winter season (i.e. no burning, light burning, average burning, heavy burning). We also assessed stove use by placing temperature logging devices (iButton DS1921G, Thermochron, Australia or LogTag UTRIX-16, OnSolution, Australia) near the wood stoves to record temperature at 20-minute intervals during each winter of observation. We measured wood moisture content during household visits using a pin-type moisture meter (MMD4E, General Tools & Instruments LLC, USA).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Analysis was conducted using R version 4.0.4 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria). We calculated descriptive statistics for continuous variables (n, mean, sd, min, median, max) and categorical variables (n, percentage of total) across all study households and separately for each treatment arm and study area. We averaged indoor concentrations of PM2.5 over the 2-day sampling periods, which were then used to calculate mean PM2.5 for each household per winter of observation.

We conducted the primary analysis with linear mixed models using the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015). In the intent-to-treat (ITT) framework with indoor PM2.5 as the outcome of interest, we included a 3-level fixed term for treatment as the primary independent variable (levels = Placebo arm, Education arm, Filtration arm), a continuous fixed term for mean baseline (Winter 1) indoor PM2.5, and a nested random term to account for repeated measures (i.e. home:cohort:area). We used a similar model to assess differences in personal PM2.5 across treatment arms. The nested random term in the personal PM2.5 model included participant ID to account for repeated measures within participant. In addition, since personal PM2.5 was only used from the NPT study area, the random nested term did not include study area (i.e. random term = participant:home:cohort). The ITT models utilized the study’s randomization and were not adjusted for potential confounding variables in the primary analyses. Sensitivity analyses were conducted that added potential confounding variables into the ITT models to assess the effectiveness of the randomization in controlling for confounding.

We evaluated potential modification of the effect of treatment by participant and household characteristics by including interaction terms in the primary model. We assessed significance of the interaction terms using Type II Wald Chi-square tests. Model assumptions were evaluated in all analysis frameworks. Indoor and personal PM2.5 concentrations were natural-log transformed, and estimates are presented as percent difference in geometric mean PM2.5.

3. Results

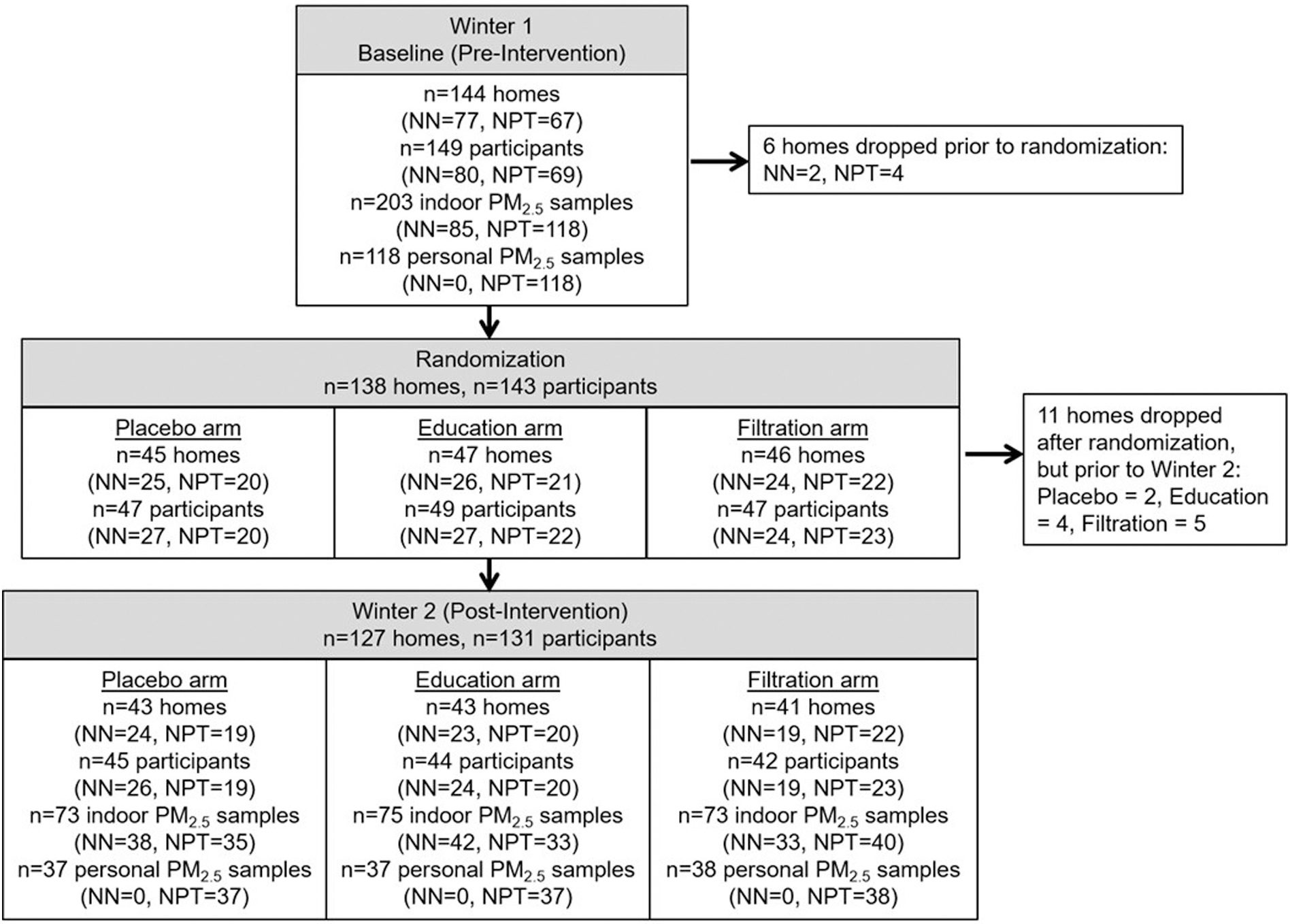

A total of 144 households and 149 participants were enrolled in the EldersAIR study and completed a baseline household visit during Winter 1 of observation (Fig. 1). During Winter 2 (post-intervention) 127 households and 131 participants remained enrolled in the study. Tables 1 and 2 highlight participant, household, and wood stove characteristics during Winter 1. A majority of the participants identified as female (70 %), AI/AN (97 %), and not Hispanic (97 %). Participants were 70 years of age on average and the majority reported having at least a high school education (Table 1). Study homes were generally single-level (89 %), and 61 % of participants reported a household income of less than $20,000 per year (Table 2). One third of the households had a resident who smoked tobacco products, and 8 % said the resident(s) smoked while indoors (Table 2). In general, participant and household characteristics were balanced across treatment arms (Tables 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Participant recruitment, enrollment, and retention.

n = number of homes or observations; NN = Navajo Nation study region; NPT = Nez Perce Tribe study region.

Table 2.

Household and wood stove characteristics at baseline (Winter 1).

| All households (Total n = 144) |

Placebo (Total n = 45) |

Filtration (Total n = 46) |

Education (Total n = 47) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Levels in home | ||||

| 1, n (%) | 128 (89) | 41 (91) | 42 (91) | 39 (83) |

| 2+, n (%) | 16 (11) | 4 (9) | 4 (9) | 8 (17) |

| Home square meters | ||||

| <111 (median), n (%) | 78 (54) | 21 (47) | 27 (59) | 27 (57) |

| 111+, n (%) | 66 (46) | 24 (53) | 19 (41) | 20 (43) |

| Household income | ||||

| Less than $20,000, n (%) | 88 (61) | 27 (60) | 26 (57) | 30 (64) |

| $20,000–$39,999, n (%) | 37 (26) | 10 (22) | 13 (28) | 13 (28) |

| $40,000+, n (%) | 19 (13) | 8 (18) | 7 (15) | 4 (9) |

| Year home was built | ||||

| <1981 (median), n (%) | 75 (52) | 25 (56) | 22 (48) | 26 (55) |

| ≥1981, n (%) | 69 (48) | 20 (44) | 24 (52) | 21 (45) |

| Pets in home | ||||

| 0, n (%) | 80 (56) | 25 (56) | 29 (63) | 23 (49) |

| 1, n (%) | 25 (17) | 7 (16) | 9 (20) | 6 (13) |

| 2+, n (%) | 39 (27) | 13 (29) | 8 (17) | 18 (38) |

| Household resident smokes | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 48 (33) | 17 (38) | 14 (30) | 16 (34) |

| No, n (%) | 95 (66) | 28 (62) | 32 (70) | 30 (64) |

| Household resident smokes inside | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 12 (8) | 2 (4) | 4 (9) | 6 (13) |

| No, n (%) | 122 (85) | 41 (91) | 36 (78) | 40 (85) |

| Age of stove | ||||

| <6 years, n (%) | 26 (18) | 10 (22) | 7 (15) | 7 (15) |

| 6 to 10 years, n (%) | 27 (19) | 9 (20) | 11 (24) | 7 (15) |

| 11 to 15 years, n (%) | 11 (8) | 3 (7) | 4 (9) | 4 (9) |

| 16+ years, n (%) | 80 (56) | 23 (51) | 24 (52) | 29 (62) |

| EPA certified stove | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 18 (13) | 7 (16) | 5 (11) | 6 (13) |

| No, n (%) | 47 (33) | 14 (31) | 18 (39) | 15 (32) |

| Do not know, n (%) | 79 (55) | 24 (53) | 23 (50) | 26 (55) |

| Chimney last cleaned | ||||

| <6 months, n (%) | 64 (44) | 22 (49) | 23 (50) | 16 (34) |

| 6 to 12 months, n (%) | 27 (19) | 10 (22) | 5 (11) | 11 (23) |

| 12 to 18 months, n (%) | 17 (12) | 4 (9) | 4 (9) | 8 (17) |

| 18+ months, n (%) | 36 (25) | 9 (20) | 14 (30) | 12 (26) |

| Self-reported relative burn level during PM2.5 sampling | ||||

| Light burning, n (%) | 29 (20) | 8 (18) | 9 (20) | 10 (21) |

| Average burning, n (%) | 86 (60) | 25 (56) | 31 (67) | 27 (57) |

| Heavy burning, n (%) | 29 (20) | 12 (27) | 6 (13) | 10 (21) |

| Primary wood collection method | ||||

| Harvest yourself, n (%) | 36 (25) | 14 (31) | 10 (22) | 11 (23) |

| Purchase, n (%) | 41 (28) | 11 (24) | 15 (33) | 14 (30) |

| Delivery program, n (%) | 65 (45) | 19 (42) | 21 (46) | 21 (45) |

| Other, n (%) | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Wood collection before burning | ||||

| <1 week, n (%) | 20 (14) | 5 (11) | 6 (13) | 9 (19) |

| 1 week to 1 month, n (%) | 36 (25) | 10 (22) | 14 (30) | 10 (21) |

| 1 to 3 months, n (%) | 41 (28) | 15 (33) | 9 (20) | 14 (30) |

| 3 to 6 months, n (%) | 21 (15) | 5 (11) | 7 (15) | 8 (17) |

| 6 months to 1 year, n (%) | 14 (10) | 8 (18) | 4 (9) | 2 (4) |

| 1 year+, n (%) | 12 (8) | 2 (4) | 6 (13) | 4 (9) |

| Wood stove grade | ||||

| High-quality, n (%) | 14 (10) | 3 (7) | 4 (9) | 6 (13) |

| Medium-quality, n (%) | 67 (47) | 21 (47) | 22 (48) | 22 (47) |

| Low-quality, n (%) | 46 (32) | 16 (36) | 15 (33) | 13 (28) |

n = number of homes or observations; sd = standard deviation; min = minimum; max = maximum; PM2.5 = fine particulate matter; AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; EPA = United States Environmental Protection Agency.

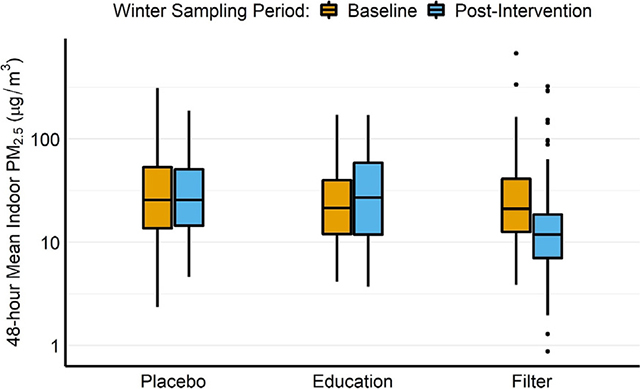

Concentrations of indoor and personal PM2.5 from pre- and post-intervention winters are presented in Table 3. Mean indoor PM2.5 during Winter 1 was 41.6 μg/m3 (sd = 59.9, min = 3.6, median = 23.6, max = 507.0), with small variations across treatment arms (Table 3). Baseline personal PM2.5 concentrations (from NPT participants only) were lower than the indoor PM2.5 concentrations, with a mean of 29.8 μg/m3 (sd = 48.7, min = 2.9, median = 15.7, max = 320.0). Personal PM2.5 also had some imbalance across treatment arms at baseline, with higher median concentrations measured among Placebo arm participants relative to measurements collected among Filtration and Education arm participants (Table 3). Participants reported that over half of the wood stoves (56 %) were over 16 years old when the study began (Table 2). Using the wood stove grading system, 10 % of the stoves were graded as high-quality, with the majority being graded as either medium-quality (47 %) or low-quality (32 %) (Table 2). In addition, 44 % of the households had cleaned the chimney within the past 6 months and 80 % of participants reported average or heavy burning in their wood stove during PM2.5 sampling relative to a typical winter period (Table 2). Table S4 reports the number of households that had indoor PM2.5 concentrations higher than EPA National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). At baseline (Winter 1), 36 % of households had mean indoor PM2.5 concentrations higher than the 24-hour standard of 35 μg/m3. Percentages were similar during the post-intervention winter, as 32 % of households had mean indoor PM2.5 concentrations higher than 35 μg/m3.

Table 3.

Mean fine particulate matter concentrations, wood moisture content, and wood stove temperature during pre- and post-intervention winters.

| All households (Total n = 144) |

Placebo (Total n = 45) |

Filtration (Total n = 46) |

Education (Total n = 47) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean indoor PM2.5 concentration during (μg/m3) | ||||

| Winter 1 | ||||

| n | 138 | 42 | 46 | 44 |

| mean (sd) | 41.6 (59.9) | 49.0 (65.4) | 41.6 (74.3) | 35.4 (35.9) |

| min, median, max | 3.6, 23.6, 507.0 | 3.6, 25.5, 310.8 | 4.9, 27.9, 507.0 | 5.9, 23.1, 171.6 |

| Winter 2 | ||||

| n | 123 | 41 | 39 | 43 |

| mean (sd) | 37.1 (41.8) | 41.6 (39.2) | 30.5 (51.5) | 38.8 (33.9) |

| min, median, max | 1.1, 19.2, 194.3 | 5.6, 30.1, 162.2 | 1.1, 12.1, 194.3 | 3.7, 23.6, 136.6 |

| Mean personal PM2.5 concentration (μg/m3); NPT participants only | ||||

| Winter 1 | ||||

| n | 66 | 20 | 22 | 21 |

| mean (sd) | 29.8 (48.7) | 39.0 (49.0) | 33.9 (67.8) | 17.8 (17.2) |

| min, median, max | 2.9, 15.7, 320.0 | 3.5, 25.5, 228.1 | 2.9, 12.0, 320.0 | 3.8, 10.2, 70.8 |

| Winter 2 | ||||

| n | 61 | 19 | 22 | 20 |

| mean (sd) | 23.7 (27.0) | 29.2 (22.3) | 23.1 (34.5) | 19.0 (21.6) |

| min, median, max | 2.2, 10.8, 128.2 | 5.8, 24.5, 75.4 | 2.5, 8.6, 128.2 | 2.2, 10.6, 70.3 |

| Wood moisture content (%) | ||||

| Winter 1 | ||||

| n | 127 | 39 | 41 | 41 |

| mean (sd) | 12.5 (4.6) | 12.1 (4.4) | 12.9 (4.4) | 12.3 (4.2) |

| min, median, max | 5.0, 12.5, 32.0 | 5.0, 12.2, 27.2 | 5.0, 12.5, 24.6 | 5.0, 12.7, 19.6 |

| Winter 2 | ||||

| n | 127 | 43 | 41 | 43 |

| mean (sd) | 12.0 (3.9) | 11.7 (4.1) | 12.3 (3.7) | 11.9 (3.9) |

| min, median, max | 5.0, 11.5, 21.5 | 5.9, 10.8, 21.5 | 5.1, 11.9, 19.2 | 5.0, 11.8, 19.5 |

| Wood stove temperature monitor (degrees Celsius) | ||||

| Winter 1 | ||||

| n | 131 | 38 | 44 | 43 |

| mean (sd) | 26.9 (6.1) | 26.7 (5.4) | 28.0 (6.8) | 26.1 (6.3) |

| min, median, max | 7.6, 26.3, 48.2 | 14.8, 26.4, 41.3 | 14.7, 26.5, 47.9 | 7.6, 25.5, 48.2 |

| Winter 2 | ||||

| n | 107 | 35 | 35 | 37 |

| mean (sd) | 26.4 (5.8) | 26.2 (5.6) | 27.4 (6.4) | 25.7 (5.4) |

| min, median, max | 7.6, 25.3, 52.8 | 14.8, 25.2, 43.9 | 13.9, 26.2, 52.8 | 7.6, 25.1, 35.9 |

n = number of homes or observations; sd = standard deviation; min = minimum; max = maximum; PM2.5 = fine particulate matter; NPT = Nez Perce Tribe study area.

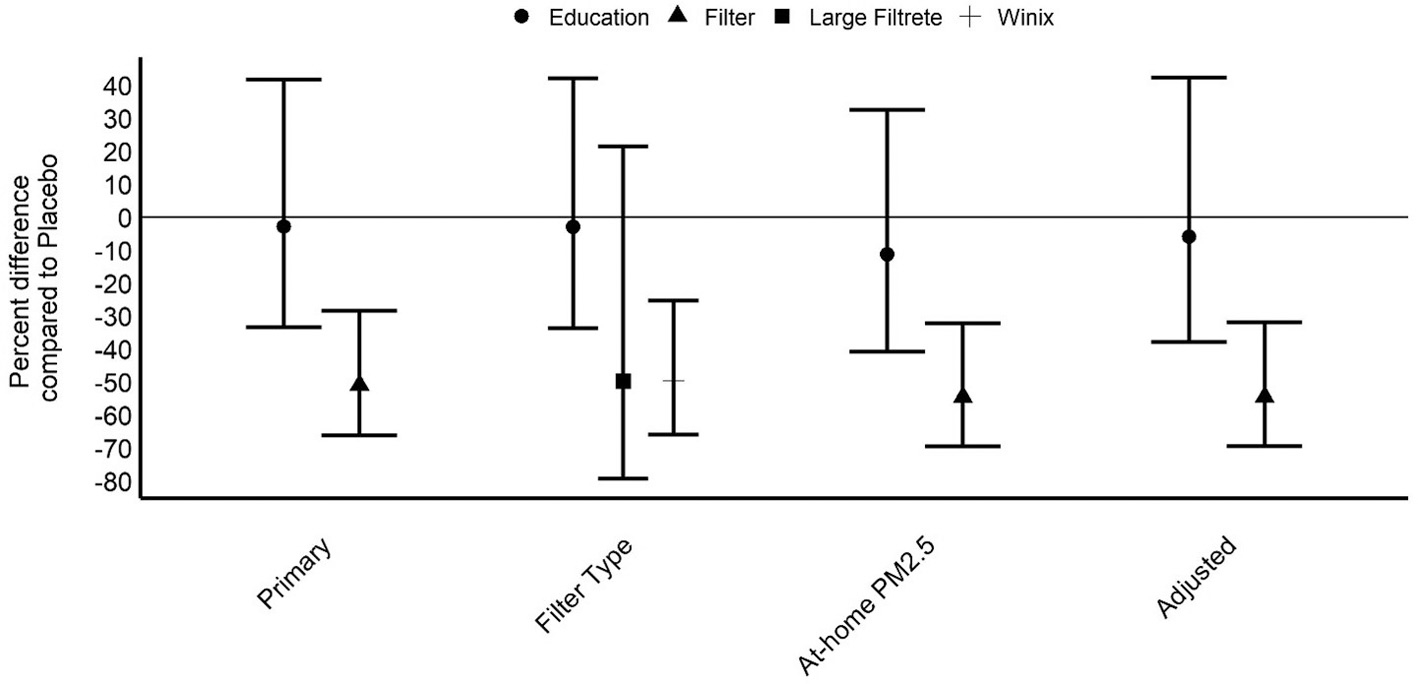

Results from the primary analysis (Table 4) are presented as percent differences and 95 % confidence intervals (95%CI) in geometric mean PM2.5 compared to the Placebo treatment arm. Indoor PM2.5 concentrations were 50.5 % lower (95%CI: −66.1, −27.8) in Filtration arm households relative to Placebo arm households. Overall, there was no difference in indoor PM2.5 among Education arm households compared to Placebo arm households (−2.9 %; 95%CI: −33.6, 42.0). Results from sensitivity analyses were generally the same as those reported in the primary analysis framework (Fig. 2). Personal PM2.5 concentrations among NPT participants were 44.7 % lower (95%CI: −69.0, −1.2) in the Filtration arm and 33.3 % lower (95%CI: −63.2, 21.1) in the education arm compared to Placebo.

Table 4.

Primary results.

| Estimateb (95 % CI) |

|

|---|---|

|

| |

| Intent-to-treat framework, indoor PM2.5a | |

| Primary model | |

| Placebo treatment (n = 68) | Reference |

| Education treatment (n = 70) | −2.9 (−33.6, 42.0) |

| Filtration treatment (n = 73) | −50.5 (−66.1, −27.8) |

| Intent-to-treat framework, personal PM2.5c | |

| Primary model | |

| Placebo treatment (n = 3s) | Reference |

| Education treatment (n = 37) | −33.3 (−63.2, 21.1) |

| Filtration treatment (n = 38) | −44.7 (−69.0, −1.2) |

PM2.5 = fine particulate matter; CI = confidence interval.

Model adjusted for baseline (Winter 1) outcome; model includes nested random term: home:cohort:area.

Estimate and 95 % Confidence Intervals reported as percent differences in geometric mean PM2.5.

Model only includes data from Nez PerceTribe study area; adjusted for baseline (Winter 1) outcome; model includes nested random term: participant:home:cohort.

Fig. 2.

Primary model results with sensitivity analyses for outcome of indoor fine particulate matter. PM2.5 = fine particulate matter.

Figure is showing model estimates and 95 % confidence intervals reported as percent differences in geometric mean PM2.5.

Model descriptions:

Primary (n = 211): Outcome variable of indoor PM2.5; exposure variable of assigned treatment (Placebo, Education, Filter); model adjusted for baseline (Winter 1) outcome; model includes nested random term (home:cohort:area).

Filter Type (n = 209): Same as Primary model, but Filter treatment is divided into 2 filtration unit types (Large Filtrete [n = 7], Winix [n = 64]). At-home PM2.5 (n = 216): Same as Primary model, but outcome is indoor PM2.5 during self-reported period when participant was home; model includes nested random term (participant:home:cohort:area). Adjusted (n = 180): Primary model, plus covariates for education, smoking status, home square meters, wood stove burn-level, gender, chimney cleaning timeline, wood stove grade, participant age, and wood moisture content.

In Table 5, we present results from analyses that assessed effect modification. Intervention efficacy varied significantly by study area (p-value for interaction = 0.05). Specifically, relative to placebo, Filtration and Education arm households in the NPT study area had substantially lower indoor PM2.5; we did not observe similar improvements among treatment arm households in the NN study area. The effect of the treatments on indoor PM2.5 was also stronger among households that dried their wood fuel for 6+ months (vs <6 months; p-value for interaction = 0.11) and among households that utilized a wood delivery program as the primary collection method (vs purchasing or self-harvesting wood fuel; p-value for interaction = 0.02). For personal PM2.5, participants in a household with no reported tobacco smoking had substantially lower PM2.5 exposures in both the Education and Filtration arms (relative to Placebo) compared to participants in a household with a tobacco user (p-value for interaction = 0.08).

Table 5.

Results from analyses assessing effect modification.

| Estimateb (95 % CI) |

p-value for interaction | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Intent-to-treat framework, indoor PM2.5a | ||

| Navajo Nation homes | 0.05 | |

| Placebo (n = 35) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 38) | 37.4 (−26.4, 156.4) | |

| Filtration (n = 33) | −23.7 (−60.3, 46.8) | |

| Nez Perce Tribe homes | ||

| Placebo (n = 33) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 32) | −34.3 (−66.3, 28.3) | |

| Filtration (n = 40) | −67.8 (−82.9, −39.4) | |

| Home square m < 110 | 0.90 | |

| Placebo (n = 42) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 34) | 6.2 (−43.2, 93.6) | |

| Filtration (n = 42) | −46.8 (−70.7, −3.1) | |

| Home square m 110+ | ||

| Placebo (n = 26) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 36) | −8.8 (−54.4, 82.2) | |

| Filtration (n = 31) | −54.9 (−78.0, −7.5) | |

| Resident smokes (yes) | 0.98 | |

| Placebo (n = 21) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 22) | −6.2 (−58.5, 111.9) | |

| Filtration (n = 15) | −47.0 (−78.3, 29.4) | |

| Resident smokes (no) | ||

| Placebo (n = 47) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 48) | −3.2 (−44.1, −67.6) | |

| Filtration (n = 58) | −49.8 (−70.5, −14.4) | |

| Burn level: none/light | 0.44 | |

| Placebo (n = 16) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 17) | 13.6 (−47.1, 143.8) | |

| Filtration (n = 15) | −62.9 (−83.2, −17.9) | |

| Burn level: average | ||

| Placebo (n = 42) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 40) | −12.4 (−48.8, 49.8) | |

| Filtration (n = 42) | −47.4 (−69.4, −9.7) | |

| Burn level: heavy | ||

| Placebo (n = 10) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 12) | 16.0 (−53.5, 189.0) | |

| Filtration (n = 16) | −39.5 (−75.4, 48.9) | |

| Stove age 0 to 10 years | 0.99 | |

| Placebo (n = 31) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 16) | 1.4 (−55.7, 132.0) | |

| Filtration (n = 27) | −49.9 (−76.0, 4.7) | |

| Stove 11+ years | ||

| Placebo (n = 37) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 54) | −5.8 (−47.4, 68.8) | |

| Filtration (n = 46) | −51.2 (−73.4, −10.8) | |

| Stove grade high quality | 0.33 | |

| Placebo (n = 1) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 12) | −51.6 (−96.0, 477.8) | |

| Filtration (n = 8) | −87.2 (−99.0, 57.0) | |

| Stove grade med quality | ||

| Placebo (n = 33) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 32) | 1.5 (−49.0, 102.0) | |

| Filtration (n = 32) | −56.0 (−78.2, −11.2) | |

| Stove grade low quality | ||

| Placebo (n = 24) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 19) | −17.5 (−65.8, 99.0) | |

| Filtration (n = 24) | −30.1 (−69.5, 60.4) | |

| Wood collection prior to burning: | 0.11 | |

| <1 month | ||

| Placebo (n = 25) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 28) | 43.4 (−31.8, 201.5) | |

| Filtration (n = 33) | −45.1 (−73.0, 11.7) | |

| 1 to 6 months | ||

| Placebo (n = 28) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 33) | 9.2 (−44.0, 112.9) | |

| Filtration (n = 26) | −40.0 (−71.4, 25.8) | |

| 6+ months | ||

| Placebo (n = 15) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 9) | −68.0 (−89.7, −0.1) | |

| Filtration (n = 14) | −72.8 (−90.1, −25.5) | |

| Primary wood collection method: | 0.02 | |

| Self-harvested | ||

| Placebo (n = 17) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 20) | 44.0 (−39.1, 240.5) | |

| Filtration (n = 13) | −17.8 (−69.0, 117.7) | |

| Purchase | ||

| Placebo (n = 18) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 16) | 40.1 (−43.2, 245.9) | |

| Filtration (n = 21) | −42.7 (−75.1, 31.7) | |

| Wood delivery program | ||

| Placebo (n = 33) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 30) | −35.1 (−66.6, 26.0) | |

| Filtration (n = 37) | −68.6 (−83.3, −40.9) | |

| Intent-to-treat framework, indoor PM2.5c | ||

| Participant age 50 to 68 | 0.56 | |

| Placebo (n = 38) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 31) | −9.2 (−52.5, 73.8) | |

| Filtration (n = 36) | −58.8 (−78.0, 22.9) | |

| Participant age 69+ | ||

| Placebo (n = 33) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 38) | 7.3 (−42.8, 101.3) | |

| Filtration (n = 39) | −38.9 (−67.4, 14.7) | |

| Female participant | 0.57 | |

| Placebo (n = 48) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 51) | 12.3 (−35.0, 93.9) | |

| Filtration (n = 49) | −49.9 (−71.2, −12.8) | |

| Male participant | ||

| Placebo (n = 24) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 20) | −23.6 (−65.8, 70.8) | |

| Filtration (n = 26) | −50.6 (−77.2, 7.0) | |

| Intent-to-treat framework, personal PM2.5d | ||

| Home square m < 110 | 0.35 | |

| Placebo (n = 17) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 12) | 4.3 (−66.8, 227.8) | |

| Filtration (n = 15) | −51.8 (−82.9, 35.4) | |

| Home square m 110+ | ||

| Placebo (n = 18) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 25) | −41.2 (−76.8, 48.9) | |

| Filtration (n = 23) | −36.2 (−75.3, 64.8) | |

| Resident smokes (yes) | 0.08 | |

| Placebo (n = 21) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 20) | −16.5 (−65.9, 104.2) | |

| Filtration (n = 16) | 11.8 (−56.1, 184.9) | |

| Resident smokes (no) | ||

| Placebo (n = 14) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 17) | −54.8 (−84.0, 27.3) | |

| Filtration (n = 22) | −68.4 (−88.1, −15.9) | |

| Stove age 0 to 10 years | 0.09 | |

| Placebo (n = 11) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 8) | −21.0 (−80.7, 224.2) | |

| Filtration (n = 10) | −76.6 (−93.8, −12.0) | |

| Stove 11+ years | ||

| Placebo (n = 24) | Reference | |

| Education (n = 29) | −34.3 (−71.8, 53.0) | |

| Filtration (n = 28) | −24.5 (−67.2, 73.9) | |

PM2.5 = fine particulate matter; CI = confidence interval; m = meter.

Model adjusted for baseline (Winter 1) outcome; model includes nested random term: home:cohort:area.

Estimate and 95 % Confidence Intervals reported as percent differences in geometric mean PM2.5.

Model adjusted for baseline (Winter 1) outcome; model includes nested random term: participant:home:cohort:area.

Model only includes data from Nez PerceTribe study area; adjusted for baseline (Winter 1) outcome; model includes nested random term: participant:home:cohort.

4. Discussion

We found that a portable air filtration intervention led to substantially lower indoor PM2.5 concentrations (−50.5 %, 95%CI: −66.1, −27.8) relative to placebo in a randomized field trial among rural, Native American elder households in the US that used wood stoves for heating. The educational intervention of best-burn practices did not substantially reduce PM2.5 concentrations relative to placebo among all study households. However, there is evidence that the educational strategies were more effective among households from the NPT study area than the NN study area. While these interventions show promise in their ability to lower indoor air pollution exposures in wood stove households, several homes post-intervention continued to show PM2.5 concentrations above the daily NAAQS standard (13 % and 40 % of homes in the filter and education arms, respectively).

A review of studies that have implemented portable air filters found that indoor PM2.5 was reduced by 23 % to 92 % across a variety of indoor settings and study designs (Cheek et al., 2020). While many of these studies were attempting to lower indoor PM2.5 from ambient sources, air filtration units have also been effective in lowering indoor PM2.5 from indoor sources such as wood stoves. Although the designs of previous studies have varied from randomized crossover studies (Allen et al., 2011; Hart et al., 2011; Wheeler et al., 2014) to randomized controlled trials (Ward et al., 2017), air filtration interventions in most studies have reduced indoor PM2.5 concentrations in wood stove homes by 50 % or more. Similar to the EldersAIR study, the ARTIS study was a pre-post household-level randomized trial in wood stove homes and showed 66 % lower geometric mean PM2.5 concentrations (95%CI: −77, −50) among homes in the air filtration arm relative to placebo (Ward et al., 2017). However, a study (KidsAIR) recently completed by our research group found that air filters did not meaningfully reduce indoor PM2.5 concentrations among rural US households with wood stoves used as a primary heating source (Walker et al., 2022). Unlike EldersAIR, the KidsAIR study was a post-only randomized trial (i.e. no baseline/pre-intervention PM2.5 samples) due to the primary study outcome of childhood lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) that decreases as children age. This post-only study design was appropriate when tracking LRTI over time (Mortimer et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2011), but baseline imbalance in PM2.5 concentrations across treatment arms – even with randomized treatment group assignment – may have impacted the KidsAIR results. Particularly in randomized studies with small sample sizes, it may be beneficial to collect baseline exposure measurements that can be incorporated into the analytical approach.

While there are multiple studies evaluating portable air filter interventions for lowering indoor PM2.5 concentrations within wood stove homes, there are limited studies of educational interventions of best burn practices. As mentioned, it is important to note that differences in PM2.5 in the EldersAIR education arm occurred among subgroups of the study households. The education intervention (relative to placebo) was more effective in reducing indoor PM2.5 among NPT households (34 % lower, 95%CI: −66, 28) than NN households (37 % higher, 95%CI: −26, 156). Similarly, personal PM2.5, which was only from the NPT study area, was 33 % lower (95%CI: −63, 21) in the education arm relative to placebo. Our team documented education delivery as part of our quality control procedures. However, given that education delivery was conducted by different study personnel, it is possible that the intervention did not have equal fidelity between the two study sites. The education programs also were adapted for specific communities. Such culturally-relevant adaptations included use of local language and, in particular, stories and experiences related to wood burning and health that were relevant to a given community (Walters et al., 2020). For example, in the NPT community a cultural leader shared the story of how fire came to the tribe in their oral histories of creation. The research team and NPT EldersAIR Community Advisory Board worked together to incorporate the fire creation story and the related symbol of the abalone shell into the videos that were part of the education intervention (Walters et al., 2020). Whether or not such community-specific adaptations accounted for the observed interaction effect between intervention and study site is unclear, but remains a possibility that would require further exploration in other communities.

The education intervention was also more effective among households that dried the wood fuel for >6 months prior to burning and among households that relied on the community wood delivery program as their primary wood collection method (Table 5), both practices which were more likely to be utilized in the NPT study area than the NN study area (Tables S1 and S2). This finding would be consistent with the hypothesis that dry wood fuel is one of the most important drivers of improved indoor air quality. If a home has dry wood fuel the education intervention has added value for improving indoor air quality, whereas the smoke generated from the use of wet wood may overwhelm any potential benefit from the education intervention. While the PM2.5 reductions in the NPT education arm were smaller than the reductions observed in the filtration arm, they may give an indication of potentially effective practices for further studies. Educational practices may also help augment other interventions (e.g. air filters or wood stove changeouts) when implemented together, which has been observed previously among NPT households that received supplemental education following a wood stove changeout intervention (Ward et al., 2011).

We cannot rule out the possible impact of measurement error, confounding, and missing data/loss to follow-up on the results we have reported. The 2-day measurements of PM2.5 may not accurately represent typical PM2.5 concentrations within the study homes. However, PM2.5 was sampled up to four times in each home over the course of the study (two times per winter), which gives us a better representation of typical indoor PM2.5 concentrations compared to many other studies which rely on proxies of exposure or a single sampling visit (Clark et al., 2013). Missing or lost data is also a potential issue with the PM2.5 measurements, particularly with the personal PM2.5 data from the NN study area. While equal numbers of PM2.5 samples were collected across treatment arms (Fig. 1), there were some differences in indoor PM2.5 concentrations among those who missed Winter 2 versus those who did not (Table S3). Specifically, participants who missed Winter 2 (n = 18) had median baseline indoor PM2.5 of 18 μg/m3 compared to a median baseline indoor PM2.5 of 24 μg/m3 for those who did not miss a study visit (n = 74). However, of the 18 participants who missed Winter 2, six were lost to follow-up prior to randomization to a treatment arm, two were in the Placebo arm, and five each were in the Education and Filtration arms; with such small sample sizes, it is difficult to make claims about missing data being related to treatment arm and potentially biasing results. Further, participants who missed any study visit (n = 72) had similar median indoor baseline PM2.5 compared to those who did not miss a visit (24 vs 23 μg/m3, respectively; Table S3). Overall, our retention of participants was excellent across the two winters of observation and missing PM2.5 data likely had minimal impact on our final results.

Confounding is a concern even in studies with randomized designs, although household and demographic characteristics were distributed relatively evenly across intervention arms (Tables 1 and 2), giving us reassurance that the randomization process accounted for both measured and unmeasured sources of confounding reasonably well. Further, results from sensitivity analyses that included potential confounders as covariates in the statistical models changed very little compared to the primary analysis results. Lastly, a potential weakness in our study is the relatively small geographic area where the research took place. Our results may not be generalizable to other wood stove users with different demographic, household, and wood stove use characteristics. However, our results are important for AI/AN communities that rely heavily on wood fuels and may be applicable to other similar populations across the US.

An important consideration in the discussion of our findings is the potential impact of ambient or outdoor air pollution on our results. It is unlikely that ambient air pollution was a confounding factor in our analysis due to the randomized nature of the study. Since households were randomized to treatment, ambient air pollution exposures were likely to be non-differential across treatment arms and have minimal impact on our results. However, there are other considerations related to the potential impact of ambient air pollution on our results. Some of the measured indoor PM2.5 concentrations we have reported were likely from ambient sources due to indoor/outdoor air exchange and ambient particle infiltration to the indoor environment. Similarly, some of the personal exposure measurements may be from ambient sources when the participants were outside their home. While air filtration units are known to effectively reduce indoor air pollution concentrations from various sources (Cheek et al., 2020), the educational intervention in EldersAIR was designed to target wood stove exposures specifically. The educational intervention may have been less effective than the air filter intervention if ambient air pollution commonly infiltrated study households. This hypothesis is purely speculative without the ability to calculate air exchange or particle infiltration in the study households. In similar settings we have previously shown that infiltration efficiency was relatively low (0.27 [sd = 0.20]) (Semmens et al., 2015). Nevertheless, indoor air pollution exposures are complex and dynamic, and indoor and ambient sources of air pollution are difficult to disentangle. Intervention strategies that can reduce exposures to both sources, such as portable air filtration units, may be most beneficial at reducing indoor air pollution exposures. This application is particularly important given the increasing PM2.5 exposures experienced throughout the Western US due to wildfires (Burke et al., 2021).

5. Conclusions

Overall, it is encouraging that the tribal-academic partnership allowed for a successful multi-site randomized trial and that air filtration interventions reduced indoor PM2.5 by 50 % relative to placebo homes. However, it is important to note that indoor PM2.5 concentrations remained high even following the interventions (Table 3). These results, along with the potential impact of educational practices, particularly in the presence of a reliable source of dry wood fuel, show some promising direction for future studies to focus on multifaceted intervention strategies in indigenous homes with wood stoves. Our results provide further evidence that portable air filtration units can reduce indoor PM2.5 that originates from indoor sources such as wood stoves. Further investigation of education-based interventions adapted to different communities will be required to determine if such strategies could provide added benefit to filter-based interventions.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Intervention study facilitated strong academic/Native American community partnerships.

Portable air filters reduced indoor fine particulate matter in wood stove homes.

Educational strategies reduced indoor fine particulate matter in subsets of homes.

More study is needed to optimize wood stove interventions in Native American homes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the many families that chose to participate in the EldersAIR study. The project also benefited from the strong support of community members and local research assistants from all study locations, including Carolyn Hester and Kathrene Conway from the University of Montana.

Funding statement

The study is funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS, 1R01ES022583). Intervention design was co-developed for the KidsAIR study (NIEHS, 1R01ES022649). Support for JG provided by Center for Population Health Research (NIGMS, 1P20GM130418).

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethics approval statement

The EldersAIR study was approved by the University of Montana IRB, the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board, and the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee.

Participant consent statement

Participants provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study. Participants were compensated for the time they spent performing study tasks and reimbursed for the cost of electricity when using the air filtration units within their homes.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ethan S. Walker: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization. Curtis W. Noonan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Annie Belcourt: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Johna Boulafentis: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Crissy Garcia: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Jon Graham: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Nolan Hoskie: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Eugenia Quintana: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Erin O. Semmens: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Julie Simpson: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Paul Smith: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Howard Teasley: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Desirae Ware: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Emily Weiler: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Tony J. Ward: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157029.

References

- Allen RW, Leckie S, Millar G, Brauer M, 2009. The impact of wood stove technology upgrades on indoor residential air quality. Atmos. Environ. 43, 5908–5915. [Google Scholar]

- Allen RW, Carlsten C, Karlen B, Leckie S, van Eeden S, Vedal S, et al. , 2011. An air filter intervention study of endothelial function among healthy adults in a woodsmoke-impacted community. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 183, 1222–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PM, Adams PF, Powell-Griner E, 2010. Health characteristics of the American Indian or Alaska native adult population: United States, 2004–2008. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S, 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using {lme4}. J. Stat. Softw. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Burke M, Driscoll A, Heft-Neal S, Xue J, Burney J, Wara M, 2021. The changing risk and burden of wildfire in the united states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheek E, Guercio V, Shrubsole C, Dimitroulopoulou S, 2020. Portable air purification: review of impacts on indoor air quality and health. Sci. Total Environ. 766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark ML, Peel JL, Balakrishnan K, Breysse PN, Chillrud SN, Naeher LP, et al. , 2013. Health and household air pollution from solid fuel use: the need for improved exposure assessment. Environ. Health Perspect. 121, 1120–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Marco R, Accordini S, Marcon A, Cerveri I, Anto JM, Gislason T, et al. , 2011. Risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a european cohort of young adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 183, 891–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA, 2013. Strategies for Reducing Residential Wood Smoke. Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards, Research Triangle Park, NC. [Google Scholar]

- EPA, 2021. Best wood-burning practices. Available: https://www.epa.gov/burnwise/best-wood-burning-practices. (Accessed 23 March 2021).

- Hart JF, Ward TJ, Spear TM, Rossi RJ, Holland NN, Loushin BG, 2011. Evaluating the effectiveness of a commercial portable air purifier in homes with wood burning stoves: a preliminary study. J. Environ. Public Health 2011, 324809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm JE, Vogeltanz-Holm N, Poltavski D, McDonald L, 2010. Assessing health status, behavioral risks, and health disparities in american indians living on the northern plains of the u.S. Public Health Rep. 125, 68–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian Health Service, 2013. Disparties. Available: http://www.ihs.gov/factsheets/index.cfm?module=dsp_fact_disparities. (Accessed 7 January 2013).

- MacDorman MF, 2011. Race and ethnic disparities in fetal mortality, preterm birth, and infant mortality in the United States: an overview. Semin. Perinatol. 35, 200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara ML, Noonan CW, Ward TJ, 2011. Correction factor for continuous monitoring of wood smoke fine particulate matter. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 11, 316–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara ML, Thornburg J, Semmens EO, Ward TJ, Noonan CW, 2017. Reducing indoor air pollutants with air filtration units in wood stove homes. Sci. Total Environ. 592, 488–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer K, Ndamala CB, Naunje AW, Malava J, Katundu C, Weston W, et al. , 2017. A cleaner burning biomass-fuelled cookstove intervention to prevent pneumonia in children under 5 years old in rural Malawi (the cooking and pneumonia study): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 389, 167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan CW, Navidi W, Sheppard L, Palmer CP, Bergauff M, Hooper K, et al. , 2012a. Residential indoor pm2.5 in wood stove homes: follow-up of the libby changeout program. Indoor Air 22, 492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan CW, Ward TJ, Navidi W, Sheppard L, 2012b. A rural community intervention targeting biomass combustion sources: effects on air quality and reporting of children’s respiratory outcomes. Occup. Environ. Med. 69, 354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan CW, Semmens EO, Ware D, Smith P, Boyer BB, Erdei E, et al. , 2019. Wood stove interventions and child respiratory infections in rural communities: kidsair rationale and methods. Contemp. Clin. Trials 89, 105909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes L, Bailey CM, Moorman JE, 2004. Asthma prevalence and control characteristics by race/ethnicity - United States, 2002. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 53, 145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semmens E, Noonan C, Ward T, Weiler E, Boulafentis J, 2011. Effectiveness of interventions in improving indoor and outdoor air quality: preliminary results from a randomized trial of woodsmoke and asthma. September 13–16Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Conference of the International Society for Environmental Epidemiology Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Semmens EO, Noonan CW, Allen RW, Weiler EC, Ward TJ, 2015. Indoor particulate matter in rural, wood stove heated homes. Environ. Res. 138, 93–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigsgaard T, Forsberg B, Annesi-Maesano I, Blomberg A, Bolling A, Boman C, et al. , 2015. Health impacts of anthropogenic biomass burning in the developed world. Eur. Respir. J. 46, 1577–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton R, Salkoski AJ, Bulkow L, Fish C, Dobson J, Albertson L, et al. , 2017. Housing characteristics and indoor air quality in households of Alaska native children with chronic lung conditions. Indoor Air 27, 478–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, McCracken JP, Weber MW, Hubbard A, Jenny A, Thompson LM, et al. , 2011. Effect of reduction in household air pollution on childhood pneumonia in Guatemala (respire): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 378, 1717–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Energy Information Agency, 2015. Residential energy consumption survey. 2015 recs survey data. Available: https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/data/2015/. (Accessed 17 February 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Walker ES, Noonan CW, Semmens EO, Ware D, Smith P, Boyer BB, et al. , 2021. Indoor fine particulate matter and demographic, household, and wood stove characteristics among rural us homes heated with wood fuel. Indoor Air 31, 1109–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker ES, Semmens E, Belcourt A, Boyer B, Erdei E, Graham J, et al. , 2022. Efficacy of air filtration and education interventions on indoor fine particulate matter and child lower respiratory tract infections among rural U.S. Homes heated with wood stoves: results from the kidsair randomized trial. Environ. Health Perspect. 130, 047002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Johnson-Jennings M, Stroud S, Rasmus S, Charles B, John S, et al. , 2020. Growing from our roots: strategies for developing culturally grounded health promotion interventions in american indian, Alaska native, and native hawaiian communities. Prev. Sci. 21, 54–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward T, Noonan C, 2008. Results of a residential indoor pm(2.5) sampling program before and after a woodstove changeout. Indoor Air 18, 408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward T, Boulafentis J, Simpson J, Hester C, Moliga T, Warden K, et al. , 2011. Lessons learned from a woodstove changeout on the nez perce reservation. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 664–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward TJ, Palmer CP, Noonan CW, 2010. Fine particulate matter source apportionment following a large woodstove changeout program in libby, Montana. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 60, 688–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward TJ, Semmens EO, Weiler E, Harrar S, Noonan CW, 2017. Efficacy of interventions targeting household air pollution from residential wood stoves. J. Exposure Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 27, 64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington Department of Health, 2012. Asthma Among Native Americans and Alaska Natives in Washington State. Washington State Department of Health, Division of Prevention and Community Health Office of Healthy Communities, Olympia, WA. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler AJ, Gibson MD, MacNeill M, Ward TJ, Wallace LA, Kuchta J, et al. , 2014. Impacts of air cleaners on indoor air quality in residences impacted by wood smoke. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 12157–12163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.