Abstract

Introduction:

There is a paucity of data exploring the extent that preclinical cognitive changes are predictive of subsequent sleep outcomes.

Methods:

Logistic regression models were used to evaluate data from a cohort of 196 African American adults who had measures of cognitive function assessed at 2 time points during a 20-year period across the mid- to late-life transition. Cognitive testing included the Delayed Word Recall, the Digit Symbol Substitution, and the Word Fluency tests, which were summarized as a composite cognitive z-score. Sleep apnea was measured by in-home sleep apnea testing and sleep duration and quality were derived from 7-day wrist actigraphy at the end of the study period.

Results:

A one standard deviation (SD) lower composite cognitive z-score at baseline was significantly associated with greater odds of low sleep efficiency (<85%) (odds ratio [OR] = 1.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.13, 3.04) and greater odds of increased wakefulness after sleep onset time (WASO; >60 minutes) (OR = 1.65, 95% CI = 1.05, 2.60) in adjusted models. A one SD faster rate of cognitive decline over the study period was significantly associated with greater odds of low sleep efficiency (OR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.04, 2.73), greater odds of sleep fragmentation (>35%); (OR = 1.73, 95% CI = 1.05, 2.85), and greater odds of increased WASO (OR = 1.85, 95% CI = 1.15, 2.95) in adjusted models. Neither baseline cognitive z-score nor rate of cognitive decline was associated with sleep apnea or the total average sleep duration.

Conclusion:

Cognition at baseline and change over time predicts sleep quality and may reflect common neural mechanisms and vulnerabilities.

Keywords: Sleep, Sleep disturbances, Cognition, Cognitive decline, Longitudinal analysis

Introduction

Cognitive impairment and sleep disturbances are common among older adults. Changes in sleep patterns, including reduced sleep duration, continuity, and quality could be a function of normal aging; however, some changes in sleep might result from accelerated aging and underlying neurodegenerative processes.1 Sleep-wake processes are regulated by complex interactions between brain regions and neurotransmitter systems, many of which are involved in memory and cognitive function.2,3 Sleep disorders are prevalent in Alzheimer disease and sleep abnormalities can also appear years before cognitive decline. Age-related disorders of both cognition and sleep are posited to have a long preclinical phase with some evidence that the etiologically important stage of life may be middle age for both of these pathophysiological processes.4,5

Cross-sectional studies suggest an association between poor sleep quantity and/or quality with cognitive impairment.6–8 Although there is significant evidence from longitudinal studies suggesting that poor sleep is a precursor to cognitive decline,9,10 few longitudinal studies have specifically examined the extent to which preclinical cognitive changes predate suboptimal sleep outcomes.11 The long latency period between the onset of neurodegenerative processes and the onset of dementia challenges the ability to determine the extent that sleep disruptions truly predate neurodegenerative cognitive processes, as opposed to the extent sleep abnormalities reflect preclinical pathological cognitive changes that are located in brain areas critical for good sleep.12 Further, there is growing evidence suggesting a bidirectional relationship between sleep pathologies and cognitive decline.13 Further, most studies exploring this association have used subjective assessments of sleep, have focused on older individuals in whom pathophysiological processes through which both poor sleep and cognitive decline develop may be well underway, have had limited follow-up, or have been done in predominately white populations.14 Thus, the relationship between cognitive decline and poor sleep, especially among nonwhite populations, remains unclear.

African Americans are disproportionately burdened by short sleep duration, poor sleep quality, and sleep disordered breathing (SDB), as well as age-related cognitive impairment,15–17 but few studies of sleep and cognitive function have included substantial numbers of this population. We sought to determine whether African Americans who experienced cognitive decline during a 20-year observational follow-up across the mid- to late-life transition were at increased risk of disturbed sleep, reduced sleep duration, or SDB.

Methods

Study population

This cohort study was conducted among the overlap of participants in the Jackson Heart Sleep Study (JHSS) and the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. The JHSS is an ancillary study of the Jackson Heart Study (JHS), a longitudinal study of African American adults recruited from the Jackson, Mississippi metropolitan area during 2000–2004 and designed to study the etiology of cardiovascular disease among African Americans.18

ARIC is a prospective cohort of 15,792 participants, aged 45–64 years old at the baseline visit of the study (1987–1989). ARIC participants were recruited from four communities in the United States: Jackson, Mississippi, Forsyth County, North Carolina, Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Washington County, Maryland. In brief, ARIC was designed to investigate the etiology of atherosclerosis and its clinical sequelae. All participants from Jackson, MS were African-American. The ARIC study design and objectives have been reported previously.19

Approximately 30% of the JHS participants were recruited from the Jackson, MS cohort of the ARIC study. Between 2012 and 2016, participants in the third JHS follow-up exam (N = 3609) or those who had participated in other follow-up JHS ancillary studies were eligible to enroll in the JHSS. Individuals who were first-degree relatives of a consenting participant or who reported regular use of continuous positive airway pressure were not eligible for the JHSS. Details of JHSS were previously published.20

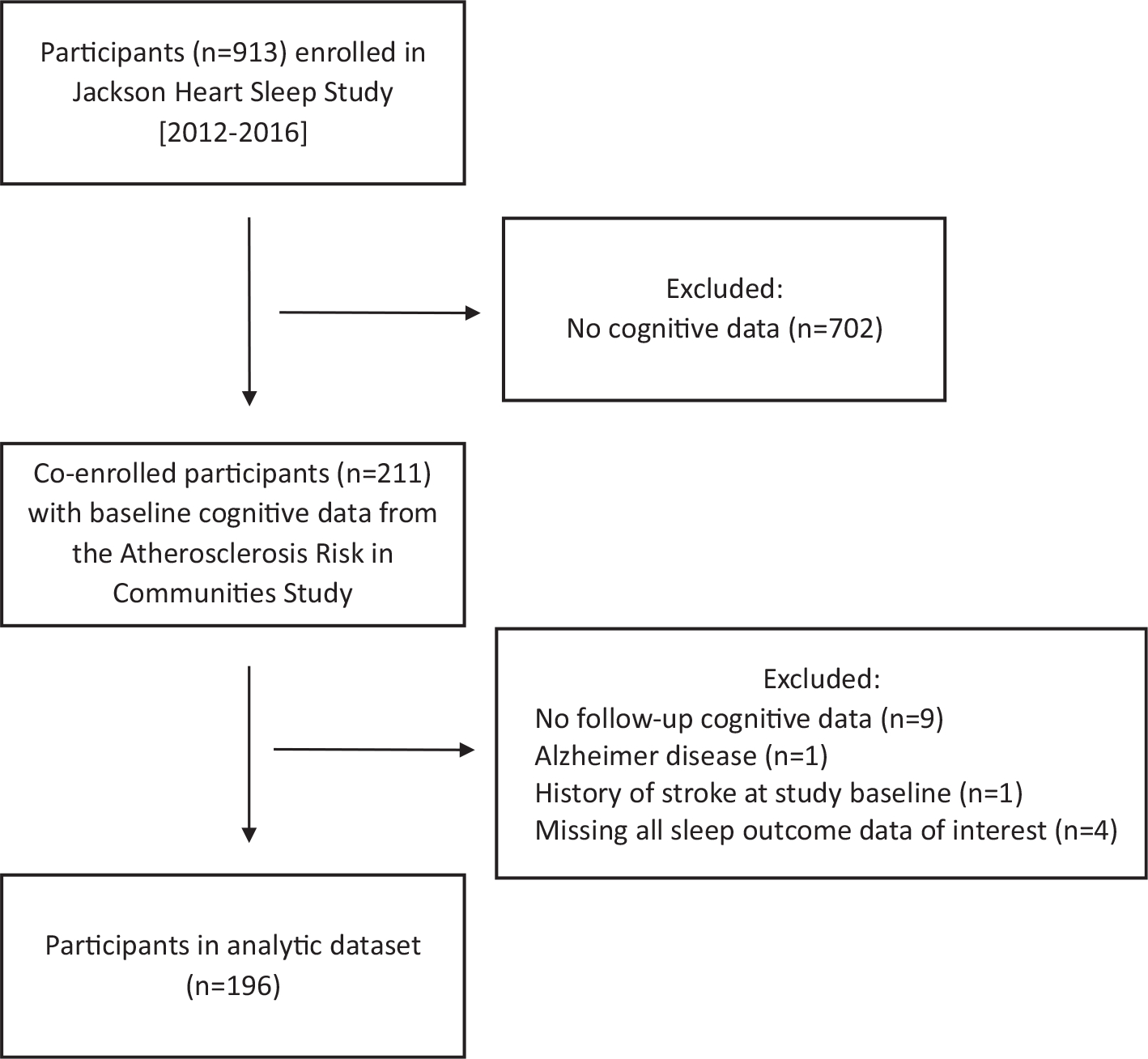

A total of 913 adults were enrolled in the JHSS (2012–2016). Of those, 211 had completed the baseline cognitive evaluation in the ARIC study (1990–1992). Participants were excluded from the current analysis if they did not have a follow-up cognitive evaluation (n = 9) at either ARIC visit 4 (1996–1998) or visit 5 (2011–2013), had self-reported physician-diagnosed Alzheimer disease (n = 1), had a history of stroke at the study baseline (n = 1), or were missing all sleep outcome data of interest for this analysis (n = 4); leaving a total of 196 individuals in the analytic dataset (shown in Fig. 1). The present analysis considered the “baseline” visit to be visit 2 of the ARIC study when cognitive data were first collected. Local institutional review boards approved the JHSS and ARIC study protocols and all participants gave informed consent.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of participants in the study.

Cognitive function tests

Delayed Word Recall (DWRT), Digit Symbol Substitution (DSST), and Word Fluency (WFT) tests were used to assess cognitive function at ARIC visit 2 (1990–1992), visit 4 (1996–1998), and visit 5 (2011–2013). Protocols for the standardized neurocognitive test battery were administered in the same sequence by trained examiners.

The DWRT tests verbal learning and recent memory.21 Participants learned 10 common nouns and used each in a sentence. After a 5-minute delay, participants were asked to recall the words. The score for the DWRT was the number of words recalled within 60 seconds. The DSST of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised tests processing speed and executive function.22 Using a key, participants were asked to translate numbers to symbols. The score was the count of numbers correctly translated to symbols in 90 seconds. The WFT tests executive function and expressive language.23 Participants generated as many words as possible beginning with each of the letters F, A, and S. The WFT score was the total number of words produced across the letters in 60 seconds.

Each cognitive test score was converted to a z-score and standardized to ARIC visit 2. A composite cognitive z-score was calculated for each visit by averaging the z-scores of the 3 tests and standardizing to visit 2. The rate of cognitive decline for each participant per year was estimated by taking the difference in the composite cognitive z-scores between the baseline score and the most recent follow-up score prior to the sleep study and dividing this difference by the time between test score examinations. The rates of decline were then standardized by subtracting an individual participant’s decline rate from the mean rate of all study participants and dividing by the rate standard deviation. The rate of decline for the DWRT, DSST, and WFT were calculated similarly.

Sleep measurements

Study participants underwent 7-day wrist actigraphy and in-home sleep apnea testing.

Participants underwent actigraphy using a GT3X+ Activity Monitor on the nondominant wrist for 7 consecutive days and completed a sleep diary to aid in scoring the actigraphy.24 Actigraphic data during 60-second epochs were scored as sleep or wake by ActiLife version 6.13 analysis software (ActiGraph Corp., Pensacola, FL) using a validated algorithm25 after manual editing records to indicate main sleep periods. Average sleep efficiency (%) was defined as the percentage of time spent asleep during the sleep period. Average sleep fragmentation (%) was defined as the percentage of 1-minute periods of sleep vs all periods of sleep during the sleep period. Wake after sleep onset (WASO) was defined as minutes of wake time after sleep onset until final awakening. Average sleep time was defined as the minutes spent asleep per main sleep period.

Sleep apnea was assessed with a validated Type 3 home sleep apnea device (Embletta-Gold device; Embla, Broomfield, CO) that records nasal pressure, thoracic and abdominal inductance plethysmography, finger pulse oximetry, body position, and electrocardiography.26,27 Obstructive apneas were identified when the amplitude of the nasal pressure signal was flat or nearly flat for >10 seconds and accompanied by respiratory effort on the abdominal or thoracic inductance plethysmography bands. Central apneas were identified if no displacement was noted on both thoracic and the abdominal inductance channels in addition to a flat nasal pressure signal. Hypopneas were identified if a ≥30% reduction of amplitude was visualized in the nasal pressure signal or, if unclear, in the respiratory inductance bands, for ≥10 seconds. The respiratory event index (REI) was calculated as the sum of all apneas plus hypopneas associated with ≥4% oxygen desaturation per hour of estimated sleep.

Covariates

The following baseline covariates were included in the models as potential confounders: age, sex, education (<high school; high school, high school equivalent, or vocational school; college, graduate, or professional school), body mass index, diabetes status (self-reported physician diagnosis, diabetes medication use, or HbA1c ≥6.5%), medication treatment for hypertension (yes/no), smoking status (current, former, never), alcohol use (current, former, never), and apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 genotype (0/at least 1 ε4 allele), which is a genetic variant associated with increased risk for cognitive decline.

Statistical analysis

The associations of sleep outcomes, modeled as dichotomized variables to enhance clinical interpretation, with baseline cognitive performance as well as rate of cognitive decline were assessed using logistic regression. Cutpoints that reflect clinically meaningful sleep disturbances and provided adequate data for the analysis were used (REI: < vs ≥15, efficiency: < vs ≥85%, fragmentation ≤ vs >35%, wake after sleep onset: < vs ≥ 60 minutes, sleep time: ≥ vs <6 hours). Long sleep was not separately evaluated due to the low numbers with a sleep duration >9 hours (n = 5). As a confirmatory analysis, we also ran the models with sleep measures as continuous variables. To reduce the impact of possible floor effects,28 we repeated the cognitive decline analyses after excluding participants in the lowest 5% of baseline composite z-score. The cognitive test scores (DWRT, DSST, WFT, and composite cognitive z-scores) were used to estimate associations with each of 5 sleep outcomes: sleep efficiency, fragmentation, wake after sleep onset, REI, and sleep time.

Results

At the baseline visit, the participants were an average age of 52.8 years (SD = 4.1; minimum = 47; maximum = 65), and were predominantly women (72%). Average length of cognitive follow-up was 20.3 years (SD = 2.5) and the average composite cognitive decline over the cognitive follow-up period was 0.45 SD. Participant characteristics at the baseline cognitive visit, stratified by rate of cognitive decline (above/below median), are presented in Table 1. Those with a higher rate of cognitive decline over the study period were significantly older, more likely to be current smokers, and scored higher on each of the baseline cognitive test scores.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by rate of cognitive decline

| Slower rate of cognitive decline (below median; n = 98) | Faster rate of cognitive decline (above median; n = 98) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age, years | 52.7 (3.9) | 54.0 (4.1) | .02 |

| Female | 73 (74%) | 69 (70%) | .52 |

| Education | .71 | ||

| Some high school or less | 16 (16%) | 21 (22%) | |

| High school/vocational school graduate | 33 (34%) | 19 (19%) | |

| College, graduate or professional school | 49 (50%) | 58 (59%) | |

| Apolipoprotein ε4 carrier | 35 (36%) | 38 (40%) | .57 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.2 (5.6) | 28.8 (4.6) | .57 |

| Diabetes | 4 (4%) | 2 (2%) | .40 |

| Hypertension, medication treated | 28 (29%) | 36 (37%) | .22 |

| Smoking status | .03 | ||

| Current | 9 (9%) | 19 (19%) | |

| Former | 30 (31%) | 32 (33%) | |

| Never | 59 (60%) | 47 (48%) | |

| Alcohol use | .63 | ||

| Current | 36 (37%) | 38 (39%) | |

| Former | 19 (19%) | 21 (21%) | |

| Never | 43 (44%) | 39 (40%) | |

| Composite cognitive z-score | −0.6 (0.8) | 0.1 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Delayed Word Recall z-score | −0.4 (0.8) | 0.3 (0.8) | <.001 |

| Digit Symbol Substitution z-score | −0.7 (0.9) | −0.3 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Word Fluency z-score | −0.2 (1.0) | 0.3 (1.1) | <.001 |

Data shown as mean (SD) or n (percentage).

The mean (SD) and percent for the sleep outcome variables were as follows: sleep efficiency: 87.6 (4.9) with 23% having a sleep efficiency < 85%; fragmentation: 29.2% (9.2) with 24% experiencing > 35% fragmentation; WASO: 52.3 (23.8) minutes with 29% experiencing > 60 minutes of WASO; REI: 10.7 (14.1) events per hour of sleep, with 22% experiencing ≥15.0 events per hour of sleep; and sleep time: 6.9 (1.1) hours with 19% sleeping < 6.0 hours.

Baseline composite cognitive z-score and sleep outcomes

The associations between the baseline composite cognitive z-score and 20-year subsequent sleep outcomes are shown in Table 2. The composite z-score at baseline was not associated with subsequently measured REI, average sleep time, or fragmentation but was significantly associated with subsequent sleep efficiency and WASO. A one SD lower cognitive score at baseline was significantly associated with increased odds of low sleep efficiency (OR = 1.85; P = .02) and increased odds of prolonged WASO (OR = 1.65; P = .03) in our fully adjusted models. Models with sleep outcomes entered as continuous variables confirmed these results (beta for baseline cognitive z-score and sleep efficiency = 1.5, P = .002; for WASO= −7.1, P = .002; P > .05 for REI, average sleep time, and fragmentation).

Table 2.

Baseline composite cognitive z-score associated with 20-year subsequent impaired sleep outcomes

| Sleep outcome | Odds ratio (95% CI) per 1 SD cognitive z-score decrement | P |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Efficiency (percentage) | ||

| Model 1 | 1.57 (1.06, 2.33) | .03 |

| Model 2 | 1.85 (1.13, 3.04) | .02 |

| Fragmentation (percentage) | ||

| Model 1 | 1.20 (0.82, 1.74) | .35 |

| Model 2 | 1.28 (0.80, 2.07) | .31 |

| Wake after sleep onset (min) | ||

| Model 1 | 1.37 (0.96, 1.97) | .09 |

| Model 2 | 1.65 (1.05, 2.60) | .03 |

| Respiratory event index | ||

| Model 1 | 0.69 (0.47, 1.03) | .07 |

| Model 2 | 0.66 (0.40, 1.10) | .11 |

| Sleep time (min) | ||

| Model 1 | 0.95 (0.63, 1.42) | .79 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (0.60, 1.67) | .99 |

Model 1: Age-adjusted.

Model 2: Adjusted for baseline age, sex, education, APOE ε4 status, BMI, diabetes status, antihypertensive medication use, smoking status, and alcohol use.

Individual baseline cognitive tests and sleep outcomes

The associations between the baseline DWRT, DSST, and WFT z-scores and 20-year subsequent sleep outcomes reveal that a 1 SD lower baseline WFT score, but not the DWRT or the DSST score, was significantly associated with subsequent low sleep efficiency (age-adjusted OR = 1.46, 95% CI 1.04–2.04; P = .03 and fully adjusted OR = 1.75, 95% CI 1.12–2.73; P = .01). None of the other individual cognitive test scores were significantly associated with any of the other measures of sleep impairment.

Composite cognitive decline and sleep outcomes

Rate of composite cognitive decline was not associated with REI or sleep duration, but was significantly associated with sleep efficiency, fragmentation, and WASO (Table 3). A one SD faster rate of decline was associated with increased odds of low sleep efficiency, (OR = 1.68; P = .03), increased odds of high sleep fragmentation (OR = 1.73; P = .03), and increased odds of prolonged WASO (OR = 1.85; P = .01) in our fully adjusted models, including the baseline cognitive z-score. Models with sleep outcomes entered as continuous variables confirmed these results (beta for baseline cognitive z-score and sleep efficiency = −1.0, P = .02; for fragmentation = 2.5, P = .002; for WASO = 5.0, P = .002; P > .05 for REI and average sleep time). We repeated the cognitive decline analyses after excluding participants in the lowest 5% of baseline composite z-score because of possible insensitivity of the tests to changes at the lowest range of their values (Table 3). After accounting for possible floor effects, the associations between rate of decline and the sleep outcomes were similar.

Table 3.

Association between rate of cognitive decline in composite cognitive z-scores over 20 years and subsequent impaired sleep outcomes, with and without exclusion of participants with a composite z-score in the lowest 5% at baseline

| Sleep outcome | Odds ratio (95% CI); p per 1 SD increment in rate of cognitive decline |

|

|---|---|---|

| All study participants | Exclusion of participants in the lowest 5% of baseline composite z-score | |

|

| ||

| Efficiency (percentage) | ||

| Model 1 | 1.69 (1.13, 2.53); 0.01 | 1.54 (1.00, 2.35); 0.048 |

| Model 2 | 1.68 (1.04, 2.73); 0.03 | 1.59 (0.97, 2.62); 0.07 |

| Fragmentation (percentage) | ||

| Model 1 | 2.00 (1.30, 3.07); 0.002 | 1.94 (1.24, 3.04); 0.004 |

| Model 2 | 1.73 (1.05, 2.85); 0.03 | 1.77 (1.06, 2.94); 0.03 |

| Wake after sleep onset (min) | ||

| Model 1 | 1.77 (1.19, 2.63); 0.005 | 1.64 (1.09, 2.48); 0.02 |

| Model 2 | 1.85 (1.15, 2.95); 0.01 | 1.79 (1.10, 2.91); 0.02 |

| Respiratory event index | ||

| Model 1 | 1.20 (0.80, 1.80); 0.39 | 1.25 (0.82, 1.90); 0.31 |

| Model 2 | 1.26 (0.79, 2.02); 0.33 | 1.33 (0.82, 2.14); 0.25 |

| Sleep time | ||

| Model 1 | 1.30 (0.86, 1.96); 0.21 | 1.35 (0.87, 2.10); 0.19 |

| Model 2 | 1.33 (0.83, 2.13); 0.23 | 1.45 (0.88, 2.38); 0.14 |

Model 1: Adjusted for baseline composite cognitive z-score and age.

Model 2: Adjusted for baseline age, baseline composite cognitive z-score, sex, education, APOE ε4 status, BMI, diabetes status, antihypertensive medication use, smoking status, and alcohol use.

Individual cognitive domain decline and sleep outcomes

A one SD increased rate of cognitive decline in the DWRT was significantly associated with increased odds of low sleep efficiency (OR = 2.12; P = .003), prolonged WASO (OR = 1.76; P = .01), and weakly associated with increased odds of high sleep fragmentation (OR = 1.51; P = .09) but not associated with REI or sleep duration in our fully adjusted models (Table 4). A one SD increased rate of decline in the DSST was significantly associated with low sleep efficiency (OR = 1.86; P = .04) and prolonged WASO (OR = 2.21; P = .005). Decline in WFT was not significantly associated with any sleep outcomes.

Table 4.

Association between the rates of cognitive decline for individual cognitive tests over 20 years and subsequent impaired sleep outcomes

| Odds ratio (95% CI); p Per 1 SD increment in rate of cognitive decline |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep outcome | Delayed word recall | Digit symbol substitution | Word fluency |

|

| |||

| Efficiency | |||

| Model 1 | 1.89 (1.23, 2.91); 0.004 | 1.55 (0.93, 2.57); 0.09 | 1.31 (0.85, 2.03); 0.22 |

| Model 2 | 2.12 (1.28, 3.51); 0.003 | 1.86 (1.03, 3.33); 0.04 | 1.30 (0.81, 2.08); 0.28 |

| Fragmentation | |||

| Model 1 | 1.63 (1.08, 2.48); 0.02 | 1.28 (0.79, 2.09); 0.32 | 1.38 (0.89, 2.16); 0.15 |

| Model 2 | 1.51 (0.93, 2.43); 0.09 | 1.23 (0.72, 2.12); 0.45 | 1.35 (0.85, 2.14); 0.20 |

| Wake after sleep onset | |||

| Model 1 | 1.61 (1.09, 2.39); 0.02 | 1.73 (1.07, 2.79); 0.03 | 1.41 (0.93, 2.13); 0.10 |

| Model 2 | 1.76 (1.12, 2.78); 0.01 | 2.21 (1.27, 3.85); 0.005 | 1.37 (0.88, 2.14); 0.17 |

| Respiratory event index | |||

| Model 1 | 1.26 (0.83, 1.91); 0.29 | 1.26 (0.76, 2.10); 0.38 | 1.17 (0.74, 1.84); 0.51 |

| Model 2 | 1.33 (0.80, 2.21); 0.28 | 1.25 (0.73, 2.16); 0.42 | 1.39 (0.86, 2.24); 0.18 |

| Sleep time | |||

| Model 1 | 1.13 (0.73, 1.76); 0.58 | 1.42 (0.83, 2.41); 0.20 | 0.98 (0.64, 1.52); 0.94 |

| Model 2 | 1.16 (0.68, 1.97); 0.58 | 1.52 (0.87, 2.68); 0.14 | 1.14 (0.74, 1.77); 0.55 |

Model 1: Adjusted for baseline cognitive z-score and age.

Model 2: Adjusted for baseline age, baseline cognitive z-score, sex, education, APOE ε4 status, BMI, diabetes status, antihypertensive medication use, smoking status, and alcohol use.

Discussion

In this prospective study of African American adults followed across the mid- to late-life transition, a single composite cognitive score that was assessed at study baseline was significantly predictive of subsequent 20-year disrupted sleep, as measured by sleep efficiency and WASO. This baseline z-score was not associated with sleep fragmentation, the frequency of SDB events, or the average total duration of sleep. Of the 3 tests of specific cognitive domains, the baseline score of word fluency—a measure of executive function and expressive language—was predictive of low sleep efficiency. Our data suggest that the value of the baseline composite cognitive score in predicting subsequent poor sleep efficiency was primarily driven by lesser scores in word fluency at the study baseline. The inclusion of potential confounding variables in the analytic models did not significantly attenuate the estimated associations.

The rate of cognitive decline, as measured by the composite cognitive score, over the 20-year period was significantly associated with increased likelihood of prospectively assessed disrupted sleep continuity, as measured by sleep efficiency, fragmentation, and WASO, but was not associated with the frequency of SDB events or the average total duration of sleep. These cognitive decline results were similar in our models accounting for floor effects. The associations between decline in the composite cognitive scores and disrupted sleep continuity appear to be primarily driven by declines in scores in the DWRT, a measure of verbal learning and recent memory, and the DSST, a measure of processing speed and executive function.

Our findings are consistent with prospective data from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures that demonstrated an association between cognitive decline and subsequent sleep disruptions, but not total duration of sleep, using data from 2,474 older white women followed for 15 years (mean age 69 years at baseline).11 Our study was able to expand on these previous results by including male participants, extending cognitive follow-up time, incorporating a more comprehensive cognitive test battery, adjusting for APOE e4, examining REI, and an examination of possible floor effects. Moreover, we observed the association between cognitive decline and subsequent disturbed sleep in African Americans—a group with a high prevalence of sleep disturbances—and showed that the trajectory of decline emerged during middle-life, at a time that likely preceded the onset of significant pathologies and multiple co-morbidities. Although we demonstrated this association occurred at an earlier age than the previous study (mean age 53 years vs 69 years), it is unclear whether the underlying mechanisms occur earlier for African-Americans or that the previous study observed the process later for white women. Cross-sectional data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis showed that compared with white study participants, Black participants had significantly higher odds of poor sleep quality at a similar age (mean 68.8 years for each group), suggesting that Blacks may have a greater incidence rate of sleep disturbances or develop sleep disturbances at an earlier age.15 Our study raises the possibility that opportunities for preventive strategies for the cognitive-sleep disturbances link be targeted for midlife or earlier.

Sleep disturbances are associated with various neurodegenerative diseases and are especially common among people with dementia.9 The association between cognitive decline and subsequent sleep disturbances could reflect a common underlying neurodegeneration etiology.3 Studies suggest that shared mechanisms underlie circadian rhythmicity and long-term memory formation.29 Alternatively, causal and reverse causal mechanisms may be operative. While sleep deprivation may be causally related to cognitive decline by reducing clearance of toxins, such as beta-amyloid, beta-amyloid deposition also may reduce sleep quality through impaired generation of slow wave oscillations.30 Growing experimental evidence suggests that beta-amyloid and p-tau proteins are deposited in areas of the brain that cause general cognitive impairment as well as in brain centers that influence wake and sleep promotion.31 The finding of an association between accelerated cognitive decline across mid-life with subsequent sleep disruption is consistent with the possibility that neurological processes that influence cognition over time also influence neurophysiological processes needed to maintain sleep continuity. However, it is also possible that cognitive decline and poor cognitive function are associated with psychological distress and depression that might affect the quality of sleep.32

In contrast to the significant associations between cognitive decline and disturbed sleep, we did not observe associations with short sleep duration. This may not be surprising given that disturbances in sleep-wake centers in individuals with Alzheimer disease and other disorders may result in disorders of arousal, with ensuing hypersomnolence. Therefore, despite low sleep efficiency (which may reduce sleep time), total sleep duration may be preserved or even increased.

Prior research suggests an association between SDB, particularly hypoxemia, with brain dysfunction. While strong evidence for reversibility is lacking, the existing data are most consistent with SDB as an antecedent risk factor for cognitive impairment.33 Our finding of no association with cognitive function or decline and subsequent frequency of respiratory disturbances provides further support that SDB is unlikely to be a consequence of early neurodegenerative processes reflected by cognitive decline. In fact, the pathoetiology of SDB appears to be more strongly related to anatomic factors that reduce upper airway size as well as ventilatory control abnormalities that reflect brainstem and peripheral chemoreflexes rather than cortical dysfunction.

A key limitation of this study is that in-home polysomnography and actigraphy were performed only at follow-up, precluding our ability to determine whether sleep disturbances were present in some participants at baseline; thus, we cannot exclude the possibility of reverse causation. Another limitation is the modest sample size, resulting in small numbers of cases with severe sleep apnea or with long sleep duration. Selection bias is another possible limitation, as the likelihood of nonparticipation in the sleep study may have been associated with both abnormal sleep characteristics and cognition. Although we were able to adjust for many potentially confounding variables, we did not have data on depression or menopausal status of women to include these covariates in the models; it is possible that residual confounding may have led to spurious associations. Further, there was no adjustment for multiple testing, either for the multiple sleep outcomes or when investigating the individual cognitive tests.

Strengths of this study include the use of objective estimates of sleep continuity and quantity, multiple objective measures of cognitive function measured over a the long follow-up period across the mid-to-late life transition, detailed measures of CVD risk factors and other potentially confounding factors, representation of both men and women, and investigation of the association in the well-characterized population of Black adults from the Jackson Heart and ARIC studies.

In summary, our study adds to the evidence suggesting that poorer cognitive function and faster cognitive decline are closely associated with indices of sleep disturbances, with a pattern suggesting that processes associated with accelerated cognitive decline increase the risk of subsequent sleep disruptions. In contrast, cognitive function did not predict SDB severity or short sleep duration, suggesting that these relationships may not be bidirectional during the mid- to late-life transition.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the staff and participants of the JHSS and the ARIC study for their important contributions.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [R01HL110068]. The Jackson Heart Study is supported and conducted in collaboration with Jackson State University [HHSN268201800013I], Tougaloo College [HHSN268201800014I], the Mississippi State Department of Health [HHSN268201800015I], and the University of Mississippi Medical Center HHSN268201800010I, HHSN268201800011I, and HHSN268201800012I contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. SR was supported in part by 5R35HL135818 and DJ was supported in part by K01HL138211.

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, and Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract nos. HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700005I, and HHSN268201700004I.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflict of interest

Dr Redline has received grant support and consulting fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and consulting fees from Eiasi Pharmaceutical. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Disclosures

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Human subjects protections

Local institutional review boards approved the JHSS and ARIC study protocols, and all participants gave informed consent.

References

- 1.Carroll JE, Irwin MR, Seeman TE, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, nighttime arousals, and leukocyte telomere length: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Sleep. 2019;42(7):zsz089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diekelmann S, Born J. The memory function of sleep. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(2):114–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhong G, Naismith SL, Rogers NL, Lewis SJ. Sleep-wake disturbances in common neurodegenerative diseases: a closer look at selected aspects of the neural circuitry. J Neurol Sci. 2011;307(1–2):9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frisoni GB, Winblad B, O’Brien JT. Revised NIA-AA criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a step forward but not yet ready for widespread clinical use. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(8):1191–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neikrug AB, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep disorders in the older adult—a mini-review. Gerontology. 2010;56(2):181–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackwell T, Yaffe K, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study G: associations between sleep architecture and sleep-disordered breathing and cognition in older community-dwelling men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Sleep Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(12):2217–2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dlugaj M, Weinreich G, Weimar C, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, sleep quality, and mild cognitive impairment in the general population. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(2):479–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramos AR, Tarraf W, Rundek T, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and neurocognitive function in a Hispanic/Latino population. Neurology. 2015;84(4):391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wennberg AMV, Wu MN, Rosenberg PB, Spira AP. Sleep disturbance, cognitive decline, and dementia: a review. Semin Neurol. 2017;37(4):395–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu W, Tan CC, Zou JJ, Cao XP, Tan L. Sleep problems and risk of all-cause cognitive decline or dementia: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(3):236–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yaffe K, Blackwell T, Barnes DE, Ancoli-Israel S, Stone KL. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures G: preclinical cognitive decline and subsequent sleep disturbance in older women. Neurology. 2007;69(3):237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward SA, Pase MP. Advances in pathophysiology and neuroimaging: implications for sleep and dementia. Respirology. 2020;25(6):580–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Egroo M, Narbutas J, Chylinski D, et al. Sleep-wake regulation and the hallmarks of the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep. 2019;42(4):zsz017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peter-Derex L, Yammine P, Bastuji H, Croisile B. Sleep and Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;19:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X, Wang R, Zee P, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in sleep disturbances: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Sleep. 2015;38(6):877–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hale L, Do DP. Racial differences in self-reports of sleep duration in a population-based study. Sleep. 2007;30(9):1096–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of dementia in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29(1–2):125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuqua SR, Wyatt SB, Andrew ME, Sarpong DF, Henderson FR, Cunningham MF, Taylor HA Jr. Recruiting African-American research participation in the Jackson Heart Study: methods, response rates, and sample description. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4 suppl 6):S6-18–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson DA, Guo N, Rueschman M, Wang R, Wilson JG, Redline S. Prevalence and correlates of obstructive sleep apnea among African Americans: the Jackson Heart Sleep Study. Sleep. 2018;41(10):zsy154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knopman DS, Ryberg S. A verbal memory test with high predictive accuracy for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol. 1989;46(2):141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sudarshan NJ, Bowden SC, Saklofske DH, Weiss LG. Age-related invariance of abilities measured with the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-IV. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(11):1489–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benton AL, Eslinger PJ, Damasio AR. Normative observations on neuropsychological test performances in old age. J Clin Neuropsychol. 1981;3(1):33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgenthaler T, Alessi C, Friedman L, et al. Practice parameters for the use of actigraphy in the assessment of sleep and sleep disorders: an update for 2007. Sleep. 2007;30(4):519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole RJ, Kripke DF, Gruen W, Mullaney DJ, Gillin JC. Automatic sleep/wake identification from wrist activity. Sleep. 1992;15(5):461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dingli K, Coleman EL, Vennelle M, et al. Evaluation of a portable device for diagnosing the sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(2):253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oldenburg O, Lamp B, Horstkotte D. Cardiorespiratory screening for sleep-disordered breathing. Eur Respir J. 2006;28(5):1065–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyenhuis DL, Garron DC. Psychometric considerations when measuring cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroepidemiology. 1997;16(4):185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerstner JR, Yin JC. Circadian rhythms and memory formation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(8):577–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mander BA, Marks SM, Vogel JW, et al. Beta-amyloid disrupts human NREM slow waves and related hippocampus-dependent memory consolidation. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(7):1051–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oh J, Eser RA, Ehrenberg AJ, et al. Profound degeneration of wake-promoting neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(10):1253–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guarnieri B, Cerroni G, Sorbi S. Sleep disturbances and cognitive decline: recommendations on clinical assessment and the management. Arch Ital Biol. 2015;153(2–3):225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yaffe K, Laffan AM, Harrison SL, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, hypoxia, and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older women. JAMA. 2011;306(6):613–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]