Abstract

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) has been extensively described in patients following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. There are now questions about what MIS-C may look like in vaccinated children. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children has many clinical and laboratory features in common with other inflammatory disorders including Kawasaki disease and toxic shock syndrome. Rheumatologic conditions can present with similar musculoskeletal complaints and elevated inflammatory markers. Laboratory markers and clinical symptoms of MIS-C usually improve once therapy is begun. We describe a child with persistent thrombocytopenia as an example of variable presentation of MIS-C in vaccinated children. This case report discusses an atypical progression of MIS-C in a vaccinated child with a known prior positive COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test. She presented with nonspecific abdominal pain and fever and was found to have elevated inflammatory markers, lymphopenia, and thrombocytopenia. Intravenous immunoglobulin and steroid treatment failed to induce rapid recovery in her clinical condition or thrombocytopenia. Rheumatologic, hematologic, oncologic, and infectious causes were considered and worked up due to the uncertainty of her case and persistence of pancytopenia but ultimately were ruled out with extensive testing and monitoring. It was key to include a broad differential including viral-induced bone marrow suppression, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and malignancy. The spectrum of MIS-C and response to treatment continues to evolve, and prior vaccination in this child’s case complicated the clinical picture further. Additional evaluation of MIS-C in vaccinated cases will permit characterization of the range of MIS-C presentation and response to standard therapy.

Keywords: MIS-C, inflammatory, COVID-19, vaccination, pancytopenia

Introduction

Shortly after the worldwide outbreak of COVID-19 in December 2019, physicians in different countries began to see a new inflammatory syndrome in children. It was first described in Italy, the United Kingdom, and New York. The constellation of symptoms was officially designated “multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children” (MIS-C) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in May 2020. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children has been described as a state of uncontrolled inflammation or cytokine storm within a few weeks after COVID-19 infection.1,2

Before the identification of MIS-C, many children were thought to have similar inflammatory conditions including Kawasaki disease, macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) or secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (sHLH), and toxic shock syndrome (TSS). These conditions have many features in common with MIS-C including gastrointestinal symptoms, mucocutaneous involvement, cardiac complications, coagulopathy, and shock. Laboratory markers used to support a diagnosis of MIS-C include elevated serologic markers (neutrophil count, C-reactive protein [CRP], erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), procalcitonin, ferritin, lactate dehydrogenase, D-dimer), abnormal coagulation studies (prothrombin time [PT], partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and international normalized ratio (INR)), anemia, thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia, elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), and elevated troponin T. These values usually normalize over time once therapy is instituted.1,3

Immunosuppression and medications that target inflammation are used across many of the aforementioned differential diagnoses. In MAS, corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antithymocyte globulin, and an interleukin (IL)-1 receptor antagonist, anakinra, are used. Of note, anakinra is also being studied as a treatment for severe COVID-19 and MIS-C. Anti-IL-6 treatment with the monoclonal antibody tocilizumab is currently under research as well.3,4 Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is the first-line treatment for patients with Kawasaki disease along with aspirin, ±corticosteroids, to reduce cardiovascular complications.3 Methotrexate has been used as a treatment for HLH.5

In the other inflammatory syndromes, proinflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-17, IL-18, interferon (IFN)-γ, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1, also known as CCL2) have been known to be elevated. Interestingly, immunosuppressive factors such as IL-10 and TNF-b have also been activated in disorders of systemic hyperinflammation.1,3,4

As of March 2022, more than 7400 children in the United States have met criteria for MIS-C. The associated death rate for these cases was 0.84% with the median age of children being 9 years.6

There have been limited published reports of MIS-C in a vaccinated children as of March 2022.7-14 This case report is the first that we are aware of MIS-C in a vaccinated pediatric patient and reveals that the presentation may differ from that in unvaccinated children.

Case Presentation

A 9-year-old female of eastern Indian origin with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency room with abdominal pain, fever, nausea, and vomiting for 3 days. She had completed the 2-dose Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 immunization series 31 days before presentation to the emergency department. She had a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test done for travel purposes 16 days prior to presentation which was positive. She was asymptomatic at the time of the test. A rapid antigen test was negative before leaving for travel.

The patient traveled with her family to the US Virgin Islands for several days and was feeling well through her return. Parents did not notice any tick bites but did report multiple mosquito bites. A few days after returning to the United States, she developed persistent fever, emesis, nausea, and abdominal pain. Respiratory viral PCR panel (RVP) at the primary pediatrician’s office was negative including for SARS-CoV-2. While waiting for the results of the RVP patient was given a dose of oseltamivir. She continued to have nausea, emesis, and decreased intake, as well as painful area at the tip of her tongue.

Polymerase chain reaction tests remain the gold standard for COVID-19 testing. Home rapid antigen tests are intended to be used in serial testing. This patient had a positive PCR test and only one negative home rapid antigen test.15

Owing to persistent symptoms, she presented to the emergency department on her third day of illness. There, she was found to be persistently febrile, with maximum temperature of 40°C, heart rate between 124 and 133 beats per minute, respiratory rate between 20 and 30 breaths/min, with oxygen saturation 96% to 100%, and blood pressure 94 to 102/44 to 54 mm Hg. Her exam was unremarkable except for mild conjunctival injection and epigastric abdominal tenderness.

Initial laboratory work-up was notable for mild hyponatremia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia, and elevated inflammatory markers (Table 1). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 PCR was negative. Rapid streptococcal antigen test was negative. Urinalysis was notable for trace ketones, protein, small leukocyte esterase with white blood cell (WBC) 10 to 19, and few bacteria seen.

Table 1.

Laboratory Values on Admission.

| Measurement | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium | 134 | mmol/L |

| Potassium | 4.3 | mmol/L |

| Chloride | 98 | mmol/L |

| Bicarbonate | 22 | mmol/L |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 13 | mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.61 | mg/dL |

| Calcium | 9.5 | mg/dL |

| White blood cell count | 2580 | unit/uL |

| Hemoglobin | 12.4 | g/dL |

| Hematocrit | 39.3 | % |

| Red blood cell count | 4,660 | unit/uL |

| Mean corpuscular volume | 84.3 | fL |

| Red cell distribution width | 12.6 | % |

| Platelets | 68 000 | unit/uL |

| Mean platelet volume | 11.7 | fL |

| Absolute immature granulocyte count | 0 | unit/uL |

| Absolute neutrophil count | 2.20 | unit/uL |

| Absolute lymphocyte count | 0.24 | unit/uL |

| Absolute monocyte count | 0.10 | unit/uL |

| Absolute basophil count | 0 | unit/uL |

| Absolute eosinophil count | 0.05 | unit/uL |

| Prothrombin time (PT) | 16.1 | seconds |

| International normalized ratio (INR) | 1.3 | seconds |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | 64 | unit/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | 67 | unit/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 77 | unit/L |

| Lipase | 12 | unit/L |

| Fibrinogen | 486 | mg/dL |

| D-dimer | 10.86 | ug/mL FEU |

| Lactate | 2.4 | mmol/L |

| Type B-natriuretic peptide (BNP) | 253 | pg/mL |

| Troponin T | <.01 | ng/mL |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | 409 | unit/L |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) | 15.87 | mg/dL |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | 37 | mm/hr |

| Ferritin | 1028 | ng/mL |

| Procalcitonin | 2.45 | ng/mL |

Those in red text are abnormal.

On admission, the patient was started on 2 g/kg IVIG in addition to empiric ceftriaxone and doxycycline for possible bacterial infection. Antibiotics were discontinued after 72 hours once cultures were negative. Parasite and viral testing for diseases endemic to the United States Virgin Islands and northeastern United States were sent. This included Anaplasma, Babesia, dengue, Erlichia chaffeensis, Leptospira, tuberculosis, Parvovirus B19, Shigella species, enteroinvasive E. coli, Shiga-toxin producing genes, Campylobacter species (jejuni and coli), and Salmonella species. She developed a macular, nonpruritic, nonpetechial rash over the neck and hands with sparing of palm and soles approximately 5 hours after starting her IVIG treatment, and this did not abate until after IVIG was completed. She was also noted to have bilateral conjunctival injection without discharge on day 1 of admission which resolved by discharge. She was afebrile 24 hours after completion of IVIG treatment to the time of discharge. In addition to IVIG, the patient was started on 2 mg/kg/day prednisone due to continued symptoms. She also had intermittent episodes of confusion and agitation for the first few days of her admission, possibly related to the combination of systemic inflammation and/or known side effects of IVIG infusion and steroids.

Owing to elevated d-dimer approximately 20× above normal at 10.87 ug/mL FEU, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis with low-molecular weight heparin was initiated. Anticoagulation was discontinued with decreasing d-dimer and worsening thrombocytopenia. Aspirin was discussed with cardiology but was not started while patient was thrombocytopenic, with an unremarkable echocardiogram.

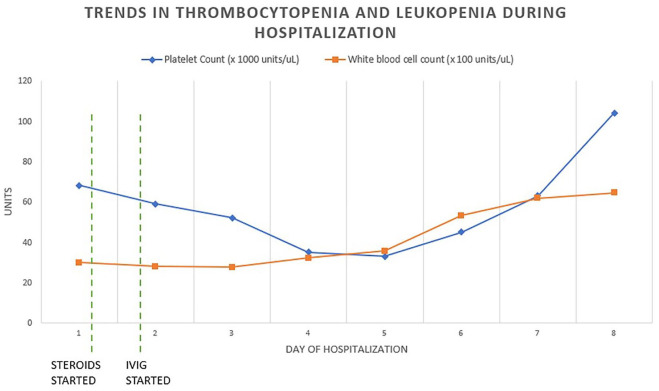

Her inflammatory markers trended downward after completion of IVIG; however, her pancytopenia persisted and reached a nadir of hemoglobin 9.7 g/dL, red blood cell count 3.61 M/uL, platelet count 30,000/uL, white blood cell count 2580 cells/uL, absolute lymphocyte count 240 (Figure 1). BNP increased to a peak of 4114 pg/mL on hospital day 3, and down trended to 429 pg/mL by day of discharge. Echocardiography remained normal at time of admission, after IVIG treatment, and after discharge.

Figure 1.

IVIG treatment was started on day 1 of hospitalization. Platelet count trended down through day 5 of hospitalization. White blood cell count was relatively stable until it increased on day 6 of hospitalization.

Because her hematologic abnormalities did not improve as expected with IVIG and steroid therapy, additional laboratory studies were obtained to exclude rheumatological conditions. Complement (C3 and C4) levels were normal; anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) was positive with titer 1:320; however, dsDNA and Smith antibodies were normal. Proinflammatory markers IL-6 and CXCL-9 were elevated at 284 pg/mL and 13 122 pg/mL, respectively.

Hematologic workup included negative direct antibody test (DAT) which decreases the likelihood of autoimmune cytopenia. Her initial peripheral smear prior to the initiation of steroids was negative for blasts, and repeat smear while on steroids remained negative. A bone marrow aspiration to further evaluate the pancytopenia was considered but was not performed due to her parents’ request. Thrombocytopenia began to improve on hospital day 7 and her platelet count was 104 000/uL at the time of discharge.

The patient met criteria for MIS-C as defined by the American Academy of Pediatrics and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: (1) she is under 21 years of age, with laboratory evidence of inflammation, requiring hospitalization, and had at least 2 systems involved; (2) other causes of her symptoms had been ruled out with extensive testing; and (3) she had a recent positive RT-PCR test for COVID-19.2,16

Discussion

The patient’s clinical history of recent positive COVID-19 PCR test and presentation with fever and gastrointestinal symptoms are both common for children who have been diagnosed with MIS-C over the last 2 years.1,3 The fact that she had traveled outside the country to a place where vector-borne infections are endemic made the differential diagnosis broader than is often the case. In addition, we could not use COVID-19 antibody testing to confirm previous infection as she was already vaccinated. The combination of empiric antibiotic treatment and prompt IVIG administration was prudent as early treatment in both infection and MIS-C are important to reduce likelihood of sepsis, need for intensive care, and poor outcomes.1,17

The patient’s lack of prompt improvement on MIS-C treatment suggested that other causes may be at play. Bone marrow suppression is not unusual in MIS-C but is rarely as severe as was observed in our patient. Pancytopenia is common with many infections including invasive bacterial infections, Rickettsia infections, dengue virus, and parvovirus, among others. All tests sent to evaluate for infectious diseases in our patient were negative. Vector borne infections usually respond within 48 to 72 hours to doxycycline, and with negative preliminary tests this left rheumatologic, hematologic, or oncologic causes in consideration.

Based on available laboratory studies, the patient met 3 of the 8 diagnostic criteria for HLH including fever, cytopenia affecting at least 2 lineages, and ferritin above 500 ug/L.18 A patient can be diagnosed with HLH if they satisfy at least 5 of the listed criteria. Our patient met 3 of these without further testing, thus it was conceivable that further workup was needed to truly rule out HLH as a diagnosis. The other 5 criteria include testing for fasting triglyceride, fibrinogen, soluble IL-2 receptor (also known as CD-25), and natural killer cell activity levels.

Although her IL-6 level was elevated, this is a nonspecific marker for a pro-inflammatory state.14 There have been many reports of IL-6 elevation in children diagnosed with MIS-C.19

Since her clinical course was atypical, it was important to keep an open mind with a broad differential including infection with bone marrow suppression, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), MAS or sHLH, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and malignancy. However, the spectrum of MIS-C and response to treatment continues to evolve, and prior vaccination in her case complicates the clinical picture further. She was vaccinated which made the MIS-C diagnosis one of exclusion, particularly since she had a persistent thrombocytopenia.

Immature platelet function (IPF) and mean platelet volume (MPV) were elevated, which can be seen with processes such as ITP but also with a recovering bone marrow (which occurred in this case on steroid therapy while hospitalized). In cases of MIS-C, there have been reports of ITP that have been discovered when steroids are weaned.20 In the case of our patient, this was determined to be less likely as her platelets decreased before steroids were weaned, but the case series did spark concern that her platelet count would not recover while tapering steroids.

The care team considered that the patient was experiencing drug-induced thrombocytopenia (DIT). Specifically, the advice of a clinical pharmacist was sought to determine if any of the patient’s current medications could be the cause. Although the patient had taken acetaminophen and ibuprofen before admission, it was deemed unlikely that these would have caused DIT. She did not present with bleeding, nor did she have clinically significant episodes of bleeding while hospitalized. In addition, upon discontinuation of both drugs, she did not have a spontaneous remission in thrombocytopenia as is seen in typical cases of DIT.21,22

Fortunately, follow-up laboratories over the subsequent 6 weeks did show that platelet count was recovering as were her ALC, WBC, and Hgb. Clinically, the patient recovered with only some mild persistent fatigue after 2 months. She was closely followed by cardiology, rheumatology, hematology and oncology, and infectious disease specialists without any evolution of an alternative diagnosis within 4 months.

Conclusions

The causes of other considered diagnoses including atypical Kawasaki disease, MAS, and HLH share in common with MIS-C the overactivation of inflammatory cascades. Utilizing a multi-specialty team and close observation of evolving laboratory abnormalities and the clinical scenario are vital when children who are vaccinated present in a similar fashion as this young lady. Infectious causes are relatively simple to rule out, but rheumatologic and hematologic/oncologic causes often require extensive workup.

Presently, children above the age of 5 years of age have been approved for vaccination against COVID-19. More data will likely be forthcoming about vaccinated children being infected with COVID-19 and whether these children may have atypical presentations of MIS-C as was witnessed in the patient discussed here.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: J.E. discloses relationship with Allergan as consultant.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed Consent: Verbal informed consent was obtained from a legally authorized representative(s) for anonymized patient information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Neera Shah Demharter  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4441-1488

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4441-1488

References

- 1. Dasgupta K, De P, Finch SE. The present state of understanding of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with SARS—CoV—2 infection—a comprehensive review of the current literature. S D Med. 2020;73(11):510-519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Childhood multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105:771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nakra NA, Blumberg DA, Herrera-Guerra A, et al. Multi-system inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) following SARS-CoV-2 infection: review of clinical presentation, hypothetical pathogenesis, and proposed management. Child (Basel). 2020;7:69. doi: 10.3390/children7070069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Otsuka R, Seino K-I. Macrophage activation syndrome and COVID-19. Inflamm Regen. 2020;40:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu L, Bashir H, Awada H, Alzubi J, Lane J. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome and multiorgan failure. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:23247096211052180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. Published 2020. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

- 7. Vogel TP, Top KA, Karatzios C, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adults (MIS-C/A): case definition & guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2021;39:3037-3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wangu Z, Swartz H, Doherty M. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) possibly secondary to COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15:e247176. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-247176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yousaf AR, Cortese MM, Taylor AW, et al. Reported cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children aged 12-20 years in the USA who received a COVID-19 vaccine, December, 2020, through August, 2021: a surveillance investigation. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6(5):303-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Poussaint TY, LaRovere KL, Newburger JW, et al. Multisystem inflammatory-like syndrome in a child following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. Vaccines. 2021;10:43. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10010043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yalçinkaya R, Öz FN, Polat M, et al. A case of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in a 12-year-old male after COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41:e87-e89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DeJong J, Sainato R, Forouhar M, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in a previously vaccinated adolescent female with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41:e104-e105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abdelgalil AA, Saeedi FA. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in a 12-year-old boy after mRNA-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41:e93-e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6:a016295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Self-testing at home or anywhere. Published 2022. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/testing/self-testing.html

- 16. American Academy of Pediatrics. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) interim guidance. Published 2022. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-mis-c-interim-guidance/

- 17. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Henter J-I, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gruber CN, Patel RS, Trachtman R, et al. Mapping systemic inflammation and antibody responses in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Cell. 2020;183:982-995.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kok EY, Srivaths L, Grimes AB. Immune thrombocytopenia following multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)—a case series. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2021;38(7):663-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bakchoul T, Marini I. Drug-associated thrombocytopenia. Hematology. 2018;2018:576-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Visentin GP, Liu CY.9. Drug induced thrombocytopenia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2007;21:685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]