Abstract

Background

Because of the increased risk of acute renal failure (ARF), the use of cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors is not recommended in patients with decompensated hepatic cirrhosis. Metamizole is not a classic COX inhibitor, but there are insufficient data to support its safe use. In this study, we investigate the effect of metamizole on the risk of ARF in these patients.

Methods

Metamizole use, ARF incidence, and patient mortality were examined in a large, retrospective, exploratory cohort and validated with data from a prospective registry.

Results

523 patients were evaluated in the exploratory cohort. Metamizole use at baseline was documented in 110 cases (21%) and was independently associated with the development of ARF, severe (grade 3) ARF, and lower survival without liver transplantation at follow-up on day 28 (HR: 2.2, p < 0.001; HR: 2.8, p < 0.001; and HR: 2.6, p < 0.001, respectively). Interestingly, the risk of ARF depended on the dose of metamizole administered (HR: 1.038, p < 0.001). Compared to patients who were treated with opioids, the rate of ARF was higher in the metamizole group (49% vs. 79%, p = 0.014). An increased risk of ARF with metamizole use was also demonstrated in the independent validation cohort (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Metamizole therapy, especially at high doses, should only be used with a high level of caution in patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

Patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis suffer from various clinical complications, such as ascites or hepatorenal syndrome, as a result of impaired liver function and portal hypertension (1). Pain, with a prevalence ranging from 30% to 79%, is a frequent yet often neglected problem (2). Conventional analgesics such as acetaminophen or opioids are either contraindicated or should be used only with great caution. High doses of acetaminophen result in direct liver injury. Opioids are often metabolized in the liver, leading to higher effective doses or longer half-lives (3– 8). Moreover, the current European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines advise against the use of classic cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors due to the increased risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) (1, 9– 12), not least because the development of AKI or chronic renal insufficiency in patients with liver cirrhosis is associated with a distinct worsening of the prognosis (13– 15).

In Germany, metamizole is considered a comparably safe treatment option and is frequently used in clinical practice (16), although its international status is controversial, especially due to the risk of agranulocytosis (17). Agranulocytosis is an extremely rare but life-threatening complication (18). The production of vasodilating prostaglandin through COX is important for kidney perfusion (19). Similarly to classic COX inhibitors such as diclofenac, metamizole and its active metabolites lead to COX inhibition, at least to a certain degree (20– 22). However, the clinical impact, particularly on COX-1 and renal function, remains to be clarified (21, 22). To date, the use of metamizole in the general population has not been connected with an elevated risk of renal impairment compared to other analgesics (23). Metamizole is accepted as a treatment option also for patients with compensated liver disease, and several studies on pharmacokinetics and safety have been performed (24, 25). It has been shown, for example, that metamizole can bring about reduced prostaglandin production in the kidney but without significant loss of renal function (25). So far, however, data from patients with decompensated cirrhosis are sparse.

In patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis renal perfusion is already impaired as a result of portal hypertension, which can ultimately lead to AKI in the form of hepatorenal syndrome. Thus, these patients may be particularly vulnerable even if low-potency COX inhibitors are used.

Moreover, metamizole is metabolized in the liver. In patients with hepatic impairment this can result in an enhanced pharmacodynamic effect (18).

Therefore, in this study we set out to investigate the effect of metamizole on the occurrence of AKI and survival in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis.

Methods

Two independent cohorts (an exploratory cohort and a validation cohort) of patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis and ascites were analyzed for the purposes of this study (validation cohort: INFEKTA, German Clinical Trials Registry ID DRKS00010664, last accessed 20 October 2021). Patients were screened for the occurrence of AKI, severe AKI (grade 3), and death or liver transplantation (LTx). Further analyses were conducted via a multivariate competing risk approach. Additionally, the concentration of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), an early marker for renal damage, was measured in patients from the validation cohort. More detailed information on the cohorts and the conduct of the analyses can be found in the eMethods.

Ethics

This study was performed according to the principles of good clinical practice and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave their written informed consent for data analysis, and the local ethics committee approved all scientific activities (project numbers 7935_BO_K_2018 and 3188–2016).

Results

Exploratory cohort

Baseline characteristics

The characteristics of the patient data at the outset of the study (baseline) are shown in Table 1. Overall, 523 patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis and ascites were included in the retrospective analysis. Metamizole use was documented in 110 patients (21%). The mean daily dose at baseline was 2 g (0.5–5.0 g).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the data of patients from the exploratory cohort with and without metamizole use*.

| Metamizole use | No metamizole | P value | |

| Patients (n, %) | 110 (21) | 413 (79) | |

| Age (years) | 54 ± 12 | 58 ± 11 | 0.004 |

| Female/male (n, %) | 45 (41)/65 (59) | 140 (34)/273 (66) | 0.172 |

| Etiology | |||

| – Viral (n, %) | 18 (16) | 70 (17) | 0.884 |

| – Alcohol (n, %) | 49 (45) | 185 (45) | 0.963 |

| – Other (n, %) | 43 (39) | 158 (38) | 0.873 |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 78 ± 14 | 80 ± 13 | 0.158 |

| AST (U/L) | 79 ± 84 | 83 ± 136 | 0.786 |

| ALT (U/L) | 55 ± 161 | 46 ± 80 | 0.439 |

| Bilirubin (µmol/L) | 100 ± 149 | 90 ± 131 | 0.493 |

| GGT (U/L) | 212 ± 254 | 162 ± 178 | 0.064 |

| Leukocytes (103/µL) | 8.23 ± 5.17 | 8.28 ± 5.66 | 0.934 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 43 ± 53 | 29 ± 31 | 0.010 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 26 ± 6 | 27 ± 6 | 0.169 |

| INR | 1.48 ± 0.32 | 1.50 ± 0.36 | 0.536 |

| Platelets (103/µL) | 146 ± 101 | 145 ± 100 | 0.939 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 132 ± 83 | 121 ± 72 | 0.225 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 136 ± 6 | 135 ± 6 | 0.185 |

| MELD | 18.01 ± 6.69 | 17.54 ± 6.57 | 0.511 |

| HE (n, %) | 14 (13) | 51 (13) | 0.965 |

| Infection (n, %) | 41 (37) | 140 (34) | 0.519 |

| – SBP (n, %) | 19 (17) | 81 (20) | 0.572 |

| – UTI (n, %) | 7 (6) | 24 (6) | 0.832 |

| – Other (n, %) | 16 (15) | 39 (10) | 0.123 |

| Esophageal varices (n, %) | 82 (75) | 318 (77) | 0.590 |

| Status post variceal bleeding (n, %) | 14 (13) | 53 (13) | 0.968 |

| HCC (n, %) | 0 (0) | 28 (7) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes (n, %) | 24 (22) | 101 (25) | 0.564 |

| Diagnostic/interventional procedure in the 7 days preceding baseline (n, %) | 90 (82) | 354 (87) | 0.168 |

| Diuretics (n, %) | 79 (72) | 312 (76) | 0.401 |

| NSBB (n, %) | 32 (29) | 138 (34) | 0.381 |

* An unpaired t test was used for continuous data, a chi-square or Fisher´s exact test for categorical data. Data are expressed as mean with standard deviation or as absolute numbers with percentages.

ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CRP, C-reactive protein; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; INR, international normalized ratio; MAP, mean arterial blood pressure; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; NSBB, non-selective beta blockers; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; UTI, urinary tract infection

Association of metamizole use with the incidence of acute kidney injury

During the observation period, 241 patients (46%) developed AKI and 65 patients (12%) severe AKI, with mean observation times of 16 and 23 days. Patients with metamizole use at baseline had a higher incidence of AKI and severe AKI during 28-day follow-up (AKI: 68% versus 40%, p < 0.001; severe AKI: 24% versus 9%, p < 0.001) (Figure 1a, b). In a multivariate analysis, metamizole use was independently associated with the occurrence of AKI and severe AKI (hazard ratio [HR] 2.2, 95% confidence interval [1.6; 3.0], p < 0.001 and HR 2.8 [1.7; 4.7], p < 0.001) (Table 2a, b). Serum sodium and the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score were also independently associated with the occurrence of AKI (AKI: HR 0.97 [0.95; 0.99], p = 0.004 and HR 1.1 [1.0; 1.1], p < 0.001; severe AKI (MELD only): HR 1.2 [1.1; 1.2], p < 0.001). The route of metamizole administration (intravenous versus oral) was not associated with an increased 28-day risk of AKI (HR 0.76 [0.43; 1.35], p = 0.35).

Figure 1.

Exploratory cohort:

a) 28-day incidence of AKI

b) 28-day incidence of severe AKI

c) 28-day LTx-free survival

Univariate competing risk analysis (a, b) or a log-rank test (c) was used to determine the level of significance. Definition of severe AKI/stage 3 AKI : increase of serum creatinine (sCr) > 3-fold relative to baseline or sCr ≥ 4.0 mg/dL (353.6 µmol/L) with an acute increase ≥ 0.3 mg/dL (≥ 26.5 µmol/L) or dialysis

AKI, Acute kidney injury; LTx, liver transplantation

Table 2. Results of the multivariate competing risk analyses (a, b) and COX regression analyses (c) with data from the exploratory cohort.

| Risk factors | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P value |

| a, 28-day incidence of AKI | |||

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 0.968 | [0.946; 0.990] | 0.004 |

| MELD | 1.063 | [1.040; 1.087] | < 0.001 |

| MAP < 65 mm hg | 1.259 | [0.827; 1.917] | 0.280 |

| Infection | 1.252 | [0.958; 1.637] | 0.100 |

| Diabetes | 1.127 | [0.844; 1.504] | 0.420 |

| Age (years) | 1.003 | [0.992; 1.015] | 0.590 |

| Metamizole | 2.188 | [1.623; 2.949] | < 0.001 |

| b, 28-day incidence of severe AKI | |||

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 1.001 | [0.953; 1.052] | 0.960 |

| MELD | 1.168 | [1.128; 1.209] | < 0.001 |

| MAP < 65 mm hg | 1.371 | [0.724; 2.598] | 0.330 |

| Infection | 1.037 | [0.621; 1.732] | 0.890 |

| Diabetes | 1.011 | [0.545; 1.875] | 0.970 |

| Age (years) | 1.009 | [0.989; 1.031] | 0.380 |

| Metamizole | 2.825 | [1.693; 4.711] | < 0.001 |

| c, 28-day mortality/LTx | |||

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 0.975 | [0.934; 1.017] | 0.240 |

| MELD | 1.135 | [1.098; 1.174] | < 0.001 |

| MAP < 65 mm hg | 0.713 | [0.329; 1.546] | 0.392 |

| Infection | 1.300 | [0.768; 2.198] | 0.329 |

| Diabetes | 0.976 | [0.513; 1.858] | 0.942 |

| Age (years) | 1.017 | [0.992; 1.042] | 0.193 |

| Metamizole | 2.565 | [1.521; 4.327] | < 0.001 |

| c, 90-day mortality/LTx | |||

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 0.964 | [0.934; 0.994] | 0.021 |

| MELD | 1.126 | [1.098; 1.154] | < 0.001 |

| MAP < 65 mm hg | 0.706 | [0.405; 1.231] | 0.220 |

| Infection | 1.070 | [0.737; 1.553] | 0.724 |

| Diabetes | 1.084 | [0.670; 1.679] | 0.718 |

| Age (years) | 1.022 | [1.005; 1.040] | 0.012 |

| Metamizole | 1.667 | [1.113; 2.496] | 0.013 |

AKI, Acute kidney injury; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LTx, liver transplantation; MAP, mean arterial blood pressure; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease

Association of metamizole use with survival without liver transplantation

Overall, 53 patients died and 7 patients received a donor liver during the follow-up period (Figure 1c). Metamizole was associated with a higher risk of death/LTx within 28 days and 90 days of baseline (28 days: 22% versus 9%, p < 0.001; 90 days: 32% versus 21%, p = 0.010) (Figure 1c, eFigure 1). In the multivariate analysis, serum sodium, MELD, age, and metamizole were independently associated with LTx/mortality (28 days [only MELD and metamizole]: HR 1.1 [1.1; 1.2], p < 0.001; HR 2.6 [1.5; 4.3], p < 0.001; 90 days: HR 1.0 [0.9; 1.0], p = 0.021; HR 1.1 [1.1; 1.2], p < 0.001; HR 1.0 [1.0; 1.0], p = 0.012; HR 1.7 [1.1; 2.5], p = 0.013, respectively) (Table 2c).

eFigure 1.

Exploratory cohort: 90-day LTx-free survival The log-rank test was used to determine the level of significance.

LTx, Liver transplantation

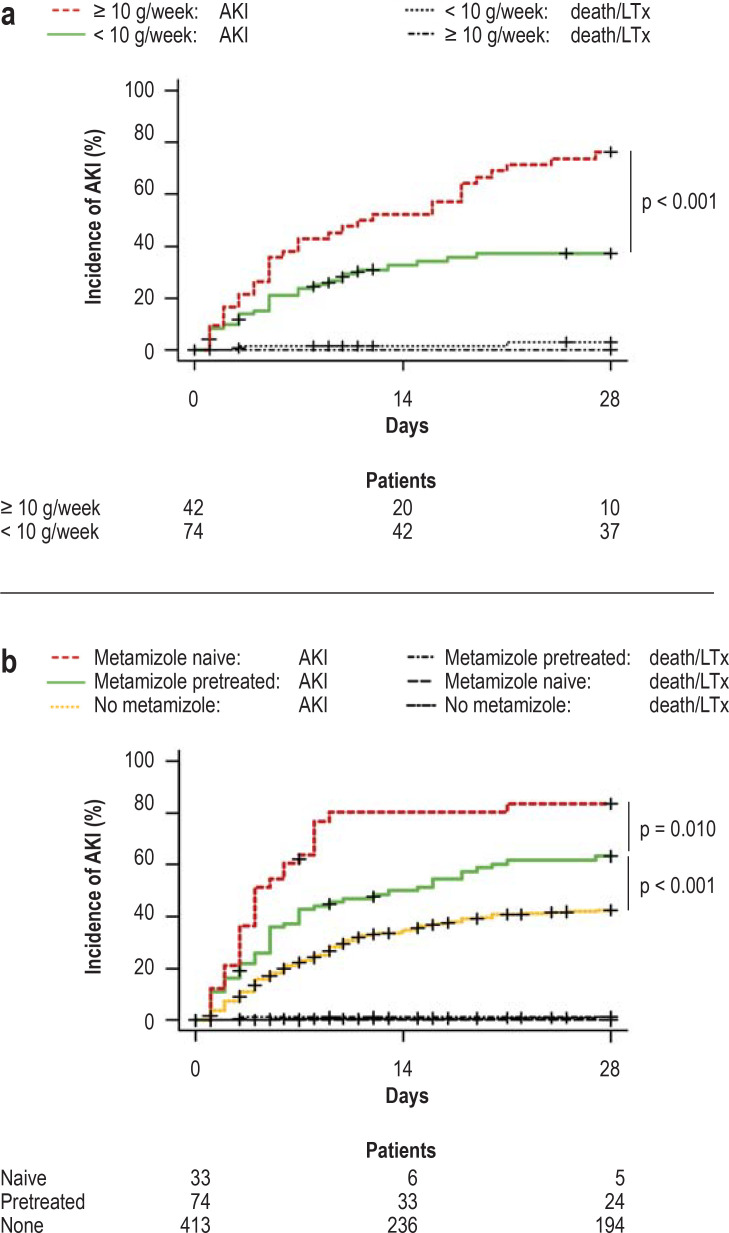

Impact of the metamizole dosage on the incidence of acute kidney injury

Multivariate competing risk analysis of the cumulative seven-day dosage revealed a 3.8% increase in AKI risk for each gram of metamizole (HR 1.038 [1.020; 1.055], p < 0.001) (etable 3). Using the Youden index, a 7-day metamizole dose of 10 g was identified as the optimal predictive cut-off for the occurrence of AKI. Only 35% of patients with a low dose (n = 30/74, < 10 g/7 days) developed AKI, compared with 76% in the high-dose group (n = 32/42, ≥ 10 g/ 7 days) (p < 0.001) (Figure 2a).

eTable 3. Results of the multivariate competing risk model for the 28-day incidence of AKI in patients from the exploratory cohort.

| Risk factors | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P value |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 0.969 | [0.946; 0.992] | 0.010 |

| MELD | 1.062 | [1.040; 1.085] | < 0.001 |

| MAP < 65 mm hg | 1.234 | [0.812; 1.876] | 0.320 |

| Infection | 1.315 | [1.007; 1.716] | 0.044 |

| Diabetes | 1.125 | [0.839; 1.510] | 0.430 |

| Age (years) | 1.002 | [0.990; 1.014] | 0.750 |

| Cumulative 7-day dose of metamizole (g) | 1.038 | [1.020; 1.055] | < 0.001 |

AKI, Acute kidney injury; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MAP, mean arterial blood pressure; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease

Figure 2.

Exploratory cohort: 28-day incidence of AKI

a) cumulative 7-day dose of metamizole 1 week prior to baseline (beginning of observation period)

b) Metamizole use newly started at baseline

Univariate competing risk analysis was carried out to determine the level of significance.

AKI, Acute kidney injury; LTx, liver transplantation

Impact of new versus pre-existing metamizole treatment

In three patients the information on previous metamizole use was incomplete. These patients were therefore excluded from this analysis. Among the remaining patients, new treatment with metamizole (no metamizole in the 7-day period immediately preceding baseline) was associated with a higher incidence of AKI than no previous metamizole treatment or no metamizole treatment at all (no metamizole: 413 patients, 40%; metamizole pretreatment: 74 patients, 61%; new treatment with metamizole: 33 patients, 82%; p < 0.001 and p = 0.010) (Figure 2b).

Comparison of incidence of acute kidney injury between metamizole and opioids

To analyze whether an elevated risk of AKI is specific to patients with need for pain medication, patients who used metamizole were compared with those who used opioids. Patients who received both substances were excluded. The AKI incidence was higher in patients with metamizole than in patients with opioids (metamizole: 78 patients, 71%; opioids: 33 patients, 49%; p = 0.014) (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Exploratory cohort: 28-day incidence of AKI

a) only opioids at baseline compared with only metamizole at baseline

Internal validation: 28-day incidence of AKI

b) internal validation

Univariate competing risk analysis was used to determine the level of significance.

AKI, Acute kidney injury; LTx, liver transplantation

Validation of the results in an independent cohort

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the validation cohort (INFEKTA) are shown in eTable 4. Overall, 115 patients were included.

eTable 4. Baseline characteristics of patients from the internal validation cohort with and without metamizole use*.

| Metamizole | No metamizole | P value | |

| Patients (n, %) | 20 (17) | 95 (83) | |

| Age (years) | 51 ± 10 | 58 ± 11 | 0.003 |

| Female/male (n, %) | 9 (45)/11 (55) | 30 (32)/65 (68) | 0.249 |

| Etiology | |||

| – Viral (n, %) | 4 (20) | 13 (14) | 0.493 |

| – Alcohol (n, %) | 9 (45) | 51 (54) | 0.480 |

| – Other (n, %) | 7 (35) | 31 (32) | 0.838 |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 81 ± 14 | 78 ± 14 | 0.516 |

| AST (U/L) | 56 ± 32 | 62 ± 68 | 0.715 |

| ALT (U/L) | 30 ± 20 | 35 ± 34 | 0.592 |

| Bilirubin (µmol/L) | 54 ± 61 | 60 ± 88 | 0.793 |

| GGT (U/L) | 174 ± 190 | 137 ± 160 | 0.368 |

| Leukocytes (103/µL) | 8.36 ± 4.89 | 6.73 ± 3.80 | 0.111 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 28 ± 40 | 25 ± 28 | 0.738 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 27 ± 6 | 28 ± 6 | 0.603 |

| INR | 1.46 ± 0.24 | 1.39 ± 0.30 | 0.399 |

| Platelets (103/µL) | 151 ± 123 | 123 ± 73 | 0.351 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 113 ± 63 | 116 ± 47 | 0.833 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 135 ± 5 | 135 ± 5 | 0.529 |

| MELD | 16.28 ± 5.65 | 15.46 ± 5.49 | 0.589 |

| HE (n, %) | 1 (5) | 18 (19) | 0.188 |

| Infection (n, %) | 11 (55) | 34 (36) | 0.118 |

| – SBP (n, %) | 4 (20) | 13 (14) | 0.495 |

| – UTI (n, %) | 1 (5) | 15 (16) | 0.297 |

| – Other (n, %) | 7 (35) | 11 (12) | 0.010 |

| Esophageal varices (n, %) | 12 (60) | 74 (80) | 0.050 |

| Status post variceal bleeding (n, %) | 3 (16) | 18 (21) | 0.758 |

| HCC (n, %) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes (n, %) | 8 (44) | 30 (44) | 0.980 |

| Diagnostic/interventional procedure in the 7 days preceding baseline (n, %) | 4 (20) | 31 (33) | 0.301 |

| Diuretics (n, %) | 15 (75) | 85 (90) | 0.081 |

| NSBB (n, %) | 6 (30) | 46 (48) | 0.132 |

* An unpaired t test was used for continuous data, a chi-square or Fisher´s exact test for categorical data. The data are expressed as mean with standard deviation or absolute numbers with percentages.

ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CRP, C-reactive protein; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; INR, international normalized ratio; MAP, mean arterial blood pressure; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; NSBB, non selective beta blockers; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; UTI, urinary tract infection

Association of metamizole use with the incidence of acute kidney injury

The cumulative 28-day incidence of AKI is shown in Figure 3b. In total, 46 patients (40%) developed AKI. The risk for AKI was higher in patients with metamizole use (75% versus 33%, 15/20 patients versus 31/95 patients, p < 0.001).

Impact of metamizole use on NGAL levels

Because NGAL is a potential marker for kidney injury, the NGAL levels in plasma and urine were compared in selected patients. eFigure 2a shows the NGAL concentrations measured in the plasma of these patients at several time points, grouped according to metamizole treatment. The levels were higher with metamizole (p = 0.032). Analysis of plasma and urine samples from patients without AKI showed that the NGAL levels among metamizole users were only numerically higher (p = 0.344 and p = 0.480) (efigure 3).

eFigure 3.

Pooled NGAL plasma (a) and urine (b) measurements in patients without acute kidney injury, categorized according to metamizole treatment. In the event of multiple samples for one patient in a subgroup, the sample obtained at the earliest time was chosen. The medians are shown by horizontal lines. The significance level was calculated using a Mann–Whitney test.

NGAL, Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin

For five patients, plasma samples before and during/after metamizole use were available. The NGAL levels were higher during/after metamizole in four of these patients (p = 0.130). Furthermore, plasma samples taken at various times were available from four patients who had not been given metamizole. No obvious pattern in the kinetics of NGAL levels was documented for these patients (p = 0.880) (eFigure 2b).

Discussion

This study shows an association between metamizole use and increased AKI incidence in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. To our knowledge, this is the first study to focus directly on the impact of metamizole in a large cohort of persons with decompensated liver cirrhosis. The findings were confirmed in an independent cohort. Moreover, there was a dose-dependent link between the dose of metamizole used and AKI incidence.

Comparison of patients taking metamizole with those taking opioids reveals that the increased risk for AKI cannot be explained exclusively by the administration of pain medication. Nonetheless, use of opioids in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis is also not advisable because opioids have been connected with hepatic decompensation and, among other events, the occurrence of encephalopathy (8, 26). It is assumed that particularly COX-1 inhibition mediates the classical disadvantages of COX inhibitors (1, 27), while other studies imply that highly selective COX-2 inhibition does not lead to kidney dysfunction (11, 28). However, clinical data regarding these substances in patients with decompensated cirrhosis remain sparse. Of note, use of COX-2 inhibitors in patients without liver cirrhosis was associated with an increased risk for AKI compared with patients without COX-2 inhibition, although non-selective COX inhibitors represented an even higher risk. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the control groups in this study may not have been comparable, so the data should be interpreted with caution (29). Moreover, more recent studies have revealed that metamizole does not, as originally assumed, primarily inhibit COX-2 (22), but also exhibits relevant effects on COX-1 (21).

One randomized study compared the renal safety profile of acetaminophen and metamizole in liver cirrhosis (25). Patients with metamizole showed lower urine and plasma prostaglandin levels after 72 hours. However, no significant increase in creatinine was documented. Altogether, the doses were relatively low (1.725 g/day). Furthermore, the mean MELD score was lower, at 10.9, and only one patient with ascites needed paracentesis. Metamizole in low doses for a limited period of time in patients with compensated cirrhosis, may therefore not be associated with an elevated risk of kidney injury. The patients in our study had advanced, decompensated liver disease with ascites and a mean MELD score of 18. Moreover, the documented link between metamizole dosage and the risk for AKI supports the hypothesis of a causal relationship. One study also showed an association between metamizole use and a higher incidence of AKI in patients admitted to the intensive care unit, i.e. another vulnerable group of patients. These authors also demonstrated a higher rate of AKI in patients with higher metamizole dosage (> 2 g/day) (30).

Our results are in line with the published data of a study that investigated the impact of different drugs, e.g., COX inhibitors and metamizole, in patients with cirrhosis and AKI on the persistence of AKI. Only metamizole was significantly associated with persistent AKI (12). Furthermore, metamizole-related AKI intake was associated with higher NGAL levels than other etiologies of AKI. NGAL is thought to be an early marker of kidney injury even at a subclinical level (31). The predictive value of NGAL in the context of liver cirrhosis has already been demonstrated (32– 34).

We did not observe any cases of metamizole-induced agranulocytosis in this study, and most deaths were liver-related. Nevertheless, it should be noted that a growing body of findings shows a relationship between liver injury (of medicinal-toxic origin) and metamizole (35, 36), even though this is a highly rare event. Moreover, it is unclear whether patients with liver cirrhosis are at a higher risk of this occurrence.

With regard to analgesia, unfortunately no safe alternative medication can currently be generally recommended. In low dosage and depending on the severity of liver disease, acetaminophen may be relatively safe (6). The use of opioids, like that of acetaminophen, should be discussed on a case by case basis. Recent studies investigating the rate of adverse events during opioid treatment in a mixed population of compensated and decompensated patients have shown that opioid prescribing differs depending on the severity of the liver disease. A higher rate of adverse events was not observed (37, 38). Evidence-based recommendations on the safe use of medications in patients with liver cirrhosis may continue to support clinicians in their decisions regarding adequate pharmacotherapy (39).

Our study has some limitations. The exploratory data were collected retrospectively, and the registry data were not originally compiled explicitly for use in this study. Furthermore, a single tertiary center was analyzed. Due to the retrospective design, further analysis of the impact of metamizole treatment duration is limited. To investigate the extent to which metamizole treatment could be a surrogate parameter for the severity of underlying disease, we adjusted our findings to take account of the MELD score, a parameter of liver disease severity. Moreover, the number of events in the validation cohort was relatively low, so these findings have to be interpreted with caution. In addition, only a small number of plasma samples were available for NGAL measurement from patients with changes in their metamizole use in the course of long-term follow-up. Further studies are therefore needed to confirm our results.

Altogether, we have shown that metamizole use in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites is independently associated with the occurrence of acute kidney injury. Metamizole, especially in high doses, should therefore be used with caution in this group of patients.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Patients and methods

Exploratory cohort

For this study we recruited a large retrospective cohort of consecutive hospitalized patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis and ascites who were admitted to Hannover Medical School between December 2011 and April 2018 (etable 1). The beginning of the observation period (baseline) was defined as the first paracentesis in the current hospital stay. The patients were observed continuously until they reached the primary and/or secondary endpoint or the end of the maximum observation period.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria have been described previously (e1). They can be summarized as follows: Patients with secondary intra-abdominal inflammation, extrahepatic malignancy, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) beyond the MILAN criteria, HIV-positive patients, patients with organ transplantation (except liver transplantation), and patients with congenital immune dysfunction were excluded, as were patients without written informed consent. Also excluded were patients with dialysis or acute kidney injury (AKI) at baseline.

The occurrence of AKI was defined according to the International Club of Ascites definitions (etable 2) (1). The patients’ medication was carefully evaluated with the aid of their medical records. All relevant substances (metamizole, opioids, diuretics, and non-selective beta blockers [NSBB]) used at baseline and for metamizole additionally 1 week prior to baseline were documented.

Validation cohort

For the validation cohort, patients were recruited from the registry for infectious complications in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites (INFEKTA, DRKS ID: DRKS00010664, last accessed 20 October 2021; eTable 1). INFEKTA is a prospective observational study including patients treated at Hannover Medical School since 2016. Patients that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria for both cohorts were included only in the INFEKTA cohort. INFEKTA patients are evaluated at predefined time points after entry in the registry (at addition, then at 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, and 12 months later, and subsequently every year), with documentation of detailed information on medication as well as clinical events in standardized form. To ensure documentation of all relevant endpoints throughout the observation period, all patients were followed up in the same way as in the exploratory cohort. Moreover, several blood and urine samples were collected and stored at –80 °C.

Measurement of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in plasma and urine

EDTA plasma and urine samples taken from INFEKTA patients at different times during the observation period were used to measure the concentration of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL). Quantitative NGAL determination was achieved by means of a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). A human NGAL-ELISA kit (ref. no.: KIT 036RUO) from Bioporto Diagnostics was used for this purpose. Validation, operation, and calculation of the results was carried out according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Study design

This is a hypothesis-generating study in which patients with and without metamizole use at baseline were compared with regard to the primary endpoint of AKI within the 28-day observation period. In addition we evaluated the secondary endpoints of severe AKI (grade 3) within 28 days as well as death/liver transplantation (LTx), documented as 28-day and 90-day LTx-free survival. Moreover, the cumulative 7-day dose of metamizole in the week preceding baseline was calculated and used to investigate possible dose dependency. Subsequently, the results were confirmed using the same approach in the independent validation cohort (INFEKTA). In the validation cohort we also investigated potential alterations in plasma and urine NGAL levels. To enable closer examination of the impact of metamizole on the kinetics of NGAL levels, we identified INFEKTA patients with plasma samples were available before and during/after metamizole administration.

Statistics

The results were expressed as mean values with standard deviation or absolute numbers with percentages and/or with precise definition of the units. The appropriate statistical tests were used to identify differences between the individual groups and/or values. The cumulative incidence curves of competing endpoints or Kaplan–Meier curves were used to illustrate the incidence of the analyzed clinical endpoints. The corresponding p-values were calculated using univariate competing risk analysis or log-rank testing. A multivariate competing risk model with stepwise selection according to p-value and stepwise Cox regression, also according to p-value, was used to analyze independent associations. To adjust the multivariate model for possible confounders, the following variables were selected to depict the progression of liver disease, portal hypertension, the general risk for AKI, and/or the patients’ individual health status: serum sodium, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, MAP < 65 mm Hg, presence of infection, diabetes, and age. The optimal cut-off for cumulative dosages of metamizole was determined with the aid of ROC curves and the Youden index. Data acquisition and data organization took place in Microsoft Excel 2016 (Redmond, USA). The final analyses were performed in SPSS Statistics 26 (Armonk, USA), R Software (R × 64 in Rgui; version 4.1.3 with cmprsk, aod, rcmdr.EZR plug-in in the rcmdr interface) and GraphPad Prism 7 (San Diego, USA).

eTable 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the exploratory and validation cohorts.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Exploratory cohort | |

| Hospitalized | Secondary intra-abdominal inflammation |

| 18 years or older | Extrahepatic malignancy |

| Diagnosis of decompensated liver cirrhosis | Hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the MILAN criteria |

| Diagnosis of ascites | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| Presented to Hannover Medical School between December 2011 and April 2018 | Organ transplantation (except liver transplantation) |

| Paracentesis within the current hospital stay (baseline) | Congenital immune dysfunction |

| No written informed consent | |

| Dialysis | |

| Acute kidney injury | |

| Validation cohort | |

| 18 years or older | Extrahepatic malignancy |

| Diagnosis of decompensated liver cirrhosis | Hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the MILAN criteria |

| Diagnosis of ascites | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| Under treatment at Hannover Medical School from 2016 onwards | Organ transplantation (except liver transplantation) |

| Congenital immune dysfunction | |

| Complete portal vein thrombosis | |

| Bone marrow transplantation | |

| Dialysis | |

| Acute kidney injury | |

eTable 2. Definitions for the diagnosis of acute kidney injury in patients with liver cirrhosis.

| Item | Definition |

| Baseline sCr | ● An sCr measurement obtained in the previous 3 months, when available, can be used as baseline sCr. In patients with more than one measurement within this period, the measurement closest to hospital admission should be used. ● In patients without sCr measurement before admission, the sCr on admission should be used as baseline. |

| Definition of AKI | ● Increase in sCr ≥ 0.3 mg/dL (≥ 26.5 µmol/l) within 48 h or ● A percentage increase in sCr ≥ 50% which is known, or can be assumed, to have occurred within the prior 7 days |

| Staging of AKI | ● Stage 1: increase in sCr ≥ 0.3 mg/dL (≥26.5 µmol/l) or an increase in sCr ≥ 1.5-fold to 2-fold from baseline ● Stage 2: increase in sCr > 2-fold to 3-fold from baseline ● Stage 3: increase of sCr > 3-fold from baseline or sCr ≥ 4.0 mg/dL (353.6 µmol/l) with an acute increase ≥ 0.3 mg/dL (≥ 26.5 µmol/l) or dialysis |

AKI, Acute kidney injury; sCr, serum creatinine

(see: EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis, 2018)

eFigure 2.

a) Pooled NGAL plasma levels, categorized according to metamizole treatment. The medians are shown by horizontal lines. The significance level was calculated using a Mann–Whitney test.

b) Longitudinal measurement of plasma NGAL in patients with sample availability over time, categorized according to metamizole treatment. Patients with acute kidney injury were excluded. Altogether, five patients are shown with metamizole initiation and four patients as control group. For metamizole initiation the mean time that elapsed between samples was 90 days (8–257 days). For the control group with no metamizole use the mean was calculated as 64 days (6–148 days). The significance level was calculated with the Wilcoxon matched pairs test.

NGAL, Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin

Acknowledgments

The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The INFEKTA Registry is financed by a donation from the German Center for Infection Research to the HepNet Study House of the German Liver Foundation (DLS).

Dr. Dörge is coordinator of the HepNet Study House of the German Liver Foundation.

Dr. Kahlhöfer is a project manager at the HepNet Study House of the German Liver Foundation.

Statement of data availability

The research data are not shared.

Acknowledgements and financial support statement

Thanks are due to Hagen Schmaus and Helena Lickei for their assistance in preparation, organization, and conduct of NGAL measurements and to Nicolas Simon for IT support and structured preparation of some of the study data. We are grateful to all the patients for their participation in this study. The INFEKTA Registry is supported by a grant from the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) to the HepNet Study House of the German Liver Foundation (DLS). The DZIF is not involved in study conception, data preparation, analysis and interpretation of the data, manuscript writing, or the decision for publication, or in any other possible way.

Ethics

This study was conducted according to the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written informed consent, and the local ethics committee of Hannover Medical School approved all scientific activities (No.: 7935_BO_K_2018 and 3188–2016).

Trial registration

The prospective registry (INFEKTA) is registered as DRKS00010664 (German Register for Clinical Trials; https://www.drks.de/drks_web/; last accessed: 20/10/2021).

References

- 1.EASL clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018;69:406–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peng J, Hepgul N, Higginson IJ, Gao W. Symptom prevalence and quality of life of patients with end-stage liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat Med. 2019;33:24–36. doi: 10.1177/0269216318807051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakoski M, Goyal P, Spencer-Safier M, Weissman J, Mohr G, Volk M. Pain management in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2018;11:135–140. doi: 10.1002/cld.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klinge M, Coppler T, Liebschutz JM, et al. The assessment and management of pain in cirrhosis. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2018;17:42–51. doi: 10.1007/s11901-018-0389-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson GD. Acetaminophen in chronic liver disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33:95–101. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1983.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGill MR, James LP, McCullough SS, et al. Short-term safety of repeated acetaminophen use in patients with compensated cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:361–373. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acharya C, Betrapally NS, Gillevet PM, et al. Chronic opioid use is associated with altered gut microbiota and predicts readmissions in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:319–331. doi: 10.1111/apt.13858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moon AM, Jiang Y, Rogal SS, Tapper EB, Lieber SR, Barritt AS. Opioid prescriptions are associated with hepatic encephalopathy in a national cohort of patients with compensated cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:652–660. doi: 10.1111/apt.15639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arroyo V, Ginés P, Rimola A, Gaya J. Renal function abnormalities, prostaglandins, and effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in cirrhosis with ascites An overview with emphasis on pathogenesis. Am J Med. 1986;81:104–122. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gentilini P. Cirrhosis, renal function and NSAIDs. J Hepatol. 1993;19:200–203. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80571-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clària J, Kent JD, López-Parra M, et al. Effects of celecoxib and naproxen on renal function in nonazotemic patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Hepatology. 2005;41:579–587. doi: 10.1002/hep.20595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elia C, Graupera I, Barreto R, et al. Severe acute kidney injury associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in cirrhosis: a case-control study. J Hepatol. 2015;63:593–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leão GS, de Mattos AA, Picon RV, et al. The prognostic impact of different stages of acute kidney injury in patients with decompensated cirrhosis: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;33:e407–e412. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000002120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bassegoda O, Huelin P, Ariza X, et al. Development of chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis is common and impairs clinical outcomes. J Hepatol. 2020;72:1132–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karagozian R, Bhardwaj G, Wakefield DB, Verna EC. Acute kidney injury is associated with higher mortality and healthcare costs in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Ann Hepatol. 2019;18:730–735. doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2019.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preissner S, Siramshetty VB, Dunkel M, Steinborn P, Luft FC, Preissner R. Pain-prescription differences—an analysis of 500,000 discharge summaries. Curr Drug Res Rev. 2019;11:58–66. doi: 10.2174/1874473711666180911091846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cascorbi I. The uncertainties of metamizole use. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;109:1373–1375. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH. prescribing information Novalgin. 2021 January [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sacerdoti D, Merlo A, Merkel C, Zuin R, Gatta A. Redistribution of renal blood flow in patients with liver cirrhosis The role of renal PGE2. J Hepatol. 1986;2:253–261. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(86)80084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patrignani P, Patrono C. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors: from pharmacology to clinical read-outs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1851:422–432. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinz B, Cheremina O, Bachmakov J, et al. Dipyrone elicits substantial inhibition of peripheral cyclooxygenases in humans: new insights into the pharmacology of an old analgesic. Faseb J. 2007;21:2343–2351. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-8061com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campos C, de Gregorio R, García-Nieto R, Gago F, Ortiz P, Alemany S. Regulation of cyclooxygenase activity by metamizol. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;378:339–347. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00477-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kötter T, da Costa BR, Fässler M, et al. Metamizole-associated adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122918. e0122918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zylber-Katz E, Caraco Y, Granit L, Levy M. Dipyrone metabolism in liver disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995;58:198–209. doi: 10.1016/0009-9236(95)90198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zapater P, Llanos L, Barquero C, et al. Acute effects of dipyrone on renal function in patients with cirrhosis: a randomized controlled trial. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;116:257–263. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogal SS, Beste LA, Youk A, et al. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions to veterans with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1165–1174e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X, Donnan PT, Bell S, Guthrie B. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug induced acute kidney injury in the community dwelling general population and people with chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18 doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0673-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosch-Marcè M, Clària J, Titos E, et al. Selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase 2 spares renal function and prostaglandin synthesis in cirrhotic rats with ascites. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1167–1175. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ungprasert P, Cheungpasitporn W, Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stueber T, Buessecker L, Leffler A, Gillmann H. The use of dipyrone in the ICU is associated with acute kidney injury: a retrospective cohort analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2017;34:673–680. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mishra J, Dent C, Tarabishi R, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. Lancet. 2005;365:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74811-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huelin P, Solà E, Elia C, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin for assessment of acute kidney injury in cirrhosis: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2019;70:319–333. doi: 10.1002/hep.30592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ariza X, Graupera I, Coll M, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is a biomarker of acute-on-chronic liver failure and prognosis in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2016;65:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barreto R, Elia C, Solà E, et al. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin predicts kidney outcome and death in patients with cirrhosis and bacterial infections. J Hepatol. 2014;61:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sebode M, Reike-Kunze M, Weidemann S, et al. Metamizole: an underrated agent causing severe idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86:1406–1415. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weber S, Benesic A, Neumann J, Gerbes AL. Liver injury associated with metamizole exposure: features of an underestimated adverse event. Drug Saf. 2021;44:669–680. doi: 10.1007/s40264-021-01049-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bloom A, Mudiyansalage VW, Rhodes A, et al. Can adequate analgesia be achieved in patients with cirrhosis without precipitating hepatic encephalopathy? A prospective study. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2020;6:243–252. doi: 10.5114/ceh.2020.99521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubin JB, Lai JC, Shui AM, Hohmann SF, Auerbach A. Patterns of inpatient opioid use and related adverse events among patients with cirrhosis: a propensity-matched analysis. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5:1081–1094. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weersink RA, Bouma M, Burger DM, et al. Evidence-based recommendations to improve the safe use of drugs in patients with liver cirrhosis. Drug Saf. 2018;41:603–613. doi: 10.1007/s40264-017-0635-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Schultalbers M, Tergast TL, Simon N, et al. Frequency, characteristics and impact of multiple consecutive nosocomial infections in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis and ascites. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:567–576. doi: 10.1177/2050640620913732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Patients and methods

Exploratory cohort

For this study we recruited a large retrospective cohort of consecutive hospitalized patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis and ascites who were admitted to Hannover Medical School between December 2011 and April 2018 (etable 1). The beginning of the observation period (baseline) was defined as the first paracentesis in the current hospital stay. The patients were observed continuously until they reached the primary and/or secondary endpoint or the end of the maximum observation period.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria have been described previously (e1). They can be summarized as follows: Patients with secondary intra-abdominal inflammation, extrahepatic malignancy, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) beyond the MILAN criteria, HIV-positive patients, patients with organ transplantation (except liver transplantation), and patients with congenital immune dysfunction were excluded, as were patients without written informed consent. Also excluded were patients with dialysis or acute kidney injury (AKI) at baseline.

The occurrence of AKI was defined according to the International Club of Ascites definitions (etable 2) (1). The patients’ medication was carefully evaluated with the aid of their medical records. All relevant substances (metamizole, opioids, diuretics, and non-selective beta blockers [NSBB]) used at baseline and for metamizole additionally 1 week prior to baseline were documented.

Validation cohort

For the validation cohort, patients were recruited from the registry for infectious complications in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites (INFEKTA, DRKS ID: DRKS00010664, last accessed 20 October 2021; eTable 1). INFEKTA is a prospective observational study including patients treated at Hannover Medical School since 2016. Patients that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria for both cohorts were included only in the INFEKTA cohort. INFEKTA patients are evaluated at predefined time points after entry in the registry (at addition, then at 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, and 12 months later, and subsequently every year), with documentation of detailed information on medication as well as clinical events in standardized form. To ensure documentation of all relevant endpoints throughout the observation period, all patients were followed up in the same way as in the exploratory cohort. Moreover, several blood and urine samples were collected and stored at –80 °C.

Measurement of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in plasma and urine

EDTA plasma and urine samples taken from INFEKTA patients at different times during the observation period were used to measure the concentration of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL). Quantitative NGAL determination was achieved by means of a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). A human NGAL-ELISA kit (ref. no.: KIT 036RUO) from Bioporto Diagnostics was used for this purpose. Validation, operation, and calculation of the results was carried out according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Study design

This is a hypothesis-generating study in which patients with and without metamizole use at baseline were compared with regard to the primary endpoint of AKI within the 28-day observation period. In addition we evaluated the secondary endpoints of severe AKI (grade 3) within 28 days as well as death/liver transplantation (LTx), documented as 28-day and 90-day LTx-free survival. Moreover, the cumulative 7-day dose of metamizole in the week preceding baseline was calculated and used to investigate possible dose dependency. Subsequently, the results were confirmed using the same approach in the independent validation cohort (INFEKTA). In the validation cohort we also investigated potential alterations in plasma and urine NGAL levels. To enable closer examination of the impact of metamizole on the kinetics of NGAL levels, we identified INFEKTA patients with plasma samples were available before and during/after metamizole administration.

Statistics

The results were expressed as mean values with standard deviation or absolute numbers with percentages and/or with precise definition of the units. The appropriate statistical tests were used to identify differences between the individual groups and/or values. The cumulative incidence curves of competing endpoints or Kaplan–Meier curves were used to illustrate the incidence of the analyzed clinical endpoints. The corresponding p-values were calculated using univariate competing risk analysis or log-rank testing. A multivariate competing risk model with stepwise selection according to p-value and stepwise Cox regression, also according to p-value, was used to analyze independent associations. To adjust the multivariate model for possible confounders, the following variables were selected to depict the progression of liver disease, portal hypertension, the general risk for AKI, and/or the patients’ individual health status: serum sodium, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, MAP < 65 mm Hg, presence of infection, diabetes, and age. The optimal cut-off for cumulative dosages of metamizole was determined with the aid of ROC curves and the Youden index. Data acquisition and data organization took place in Microsoft Excel 2016 (Redmond, USA). The final analyses were performed in SPSS Statistics 26 (Armonk, USA), R Software (R × 64 in Rgui; version 4.1.3 with cmprsk, aod, rcmdr.EZR plug-in in the rcmdr interface) and GraphPad Prism 7 (San Diego, USA).