Abstract

Purpose:

We estimated penetrance of actionable genetic variants and assessed near-term outcomes following return of results (RoR).

Methods:

Participants (n=2535) with hypercholesterolemia and/or colon polyps underwent targeted sequencing of 68 genes and 14 single nucleotide variants. Penetrance was estimated based on presence of relevant traits in the electronic health record (EHR). Outcomes occurring within 1-year of RoR were ascertained by EHR review. Analyses were stratified by Tier 1 and non-Tier 1 disorders.

Results:

Actionable findings were present in 122 individuals and results were disclosed to 98. The average penetrance for Tier 1 disorder variants (67%; n=58 individuals) was higher than in non-Tier 1 variants (46.5%; n=58 individuals). After excluding 45 individuals (decedents, non-responders, known genetic diagnoses, mosaicism), ≥1 outcomes were noted in 83% of 77 participants following RoR; 77.9% had a process outcome (referral to a specialist, new testing, surveillance initiated); 67.9% had an intermediate outcome (new test finding or diagnosis); 19.2% had a clinical outcome (therapy modified, risk reduction surgery). Risk reduction surgery occurred more often in participants with Tier 1 than those with non-Tier 1 variants.

Conclusions:

Relevant phenotypic traits were observed in 57% whereas a clinical outcome occurred in 19.2% of participants with actionable genomic variants in the year following RoR.

INTRODUCTION

Several genome sequencing projects are being conducted in diverse healthcare and population settings including the eMERGE network, the Implementing Genomics in Practice (IGNITE) network, Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research (CSER) and Geisinger Health System’s MyCode project. Additional large population scale projects such as the All of Us Research Program which aims to sequence 1 million US participants, the UK Biobank project comprising 500,000 individuals, and the Genomics England project sequencing 100,000 genomes, plan to return results from genome sequencing. Several health systems in the United States and other countries1 have begun to integrate genomic sequencing data into patient care and disease prevention. However, knowledge gaps in two key areas need to be addressed to enable the appropriate implementation of genomic medicine.

First, estimates of penetrance of pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants identified by genome sequencing are needed.2. Initial reports suggest that P/LP variants in several genes may have low penetrance3,4 and the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) has highlighted the need for more accurate estimates of penetrance obtained through genotype–phenotype correlation studies.2 Previous attempts to refine penetrance estimates have been limited in their size and scope5 and large population-based sequencing studies may contribute substantially to our understanding of the pathogenicity of rare genetic variants.6

Second, the effects of returning actionable genomic variants on health-related outcomes are largely unknown.7–11 Genomic sequencing has potential applications in medical diagnosis, risk assessment, treatment, and prevention of both rare and common diseases.12 Currently there is limited evidence supporting clinical utility of genome sequencing to guide health service delivery and disease prevention in the general population.13 Few studies8,11 have examined the effect of genome sequencing on participant outcomes, including the influence of return of results (RoR) on testing and changes in therapy or intervention. Such information is necessary to develop an evidence base that will inform clinical practice recommendations, guidelines for reimbursement, and insurance coverage decisions.

The Return of Actionable Variants Empiric (RAVE) Study, conducted as part of phase III of the NHGRI funded eMERGE network, aimed to begin to address these gaps in knowledge. The eMERGEseq panel comprised 68 medically relevant genes including the ACMG 5613 plus 12 genes selected by eMERGE investigators.14 The panel also included 14 single nucleotide variants for which homozygosity for risk alleles was considered actionable. Our objectives were: 1) to estimate penetrance of actionable variants by reviewing electronic health record (EHR) data for presence of relevant phenotypic traits; 2) assess near-term (1-year) outcomes after returning clinically actionable findings. Such data is needed to assess the broader medical impact of genome sequencing, including referral for additional medical evaluation, clinical management of genetic risk, and initiation of risk mitigation strategies.

METHODS

Study design

The design of the RAVE study, an eMERGE network genomic medicine implementation study, has been previously described.15 The study prospectively recruited individuals for targeted genomic sequencing. The genes included those associated with Tier 1 conditions (defined by CDC’s Office of Public Health Genomics as “those having significant potential for positive impact on public health based on available evidence-based guidelines and recommendations”), as well as genes with established clinical associations but lesser evidence on clinical utility (e.g., non-Tier 1 genomic conditions).15,16 This report follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.17

Setting

Participants were recruited from biobanks established at Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, primarily the Mayo Clinic Biobank and IRB-approved Mayo Clinic Vascular Diseases Biorepository. The Mayo Clinic Biobank was established in 2009 and contains biological specimens, patient-provided health information and EHR clinical data (see biobank website https://www.mayo.edu/research/centers-programs/mayo-clinic-biobank/for-researchers). RAVE study candidates were asked to complete a study consent form, health questionnaires and provide a blood sample (if an existing sample was not available) to participate in this study. This study and the informed consent process were approved by the Mayo Institutional Review Board. Information about the Mayo Clinic Biobank’s collection and enrollment methods are described here.18 Data is deposited in dbGAp (accession code phs001616.v2.p2)

Participants

Participants (n=2,535) were ascertained based on the presence of an elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (≥155 mg/dL) and/or at least one polyp on colonoscopy to undergo targeted sequencing of 68 genes and 14 SNVs using the eMERGEseq panel.14 DNA samples were sent to Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center (BCM-HGSC), a Central Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA)-certified facility, for targeted sequencing. Additional details of sequencing methods and variant annotation have been previously described.14,15,19 The ACMG five-tier classification system was used to classify variants as pathogenic, likely pathogenic, uncertain significance, likely benign and, benign.19 The BCM-HGSC laboratory identified actionable variants, confirmed these by Sanger sequencing and issued clinical reports which were reviewed by investigators at the Mayo Clinic prior to disclosure to participants and placement of results in the EHR. Variants of uncertain significance were not returned.

Return of Results (RoR).

Participants with an actionable variant (a P/LP variant in any of the 68 genes, or actionable genotypes at any of the 14 SNVs) were contacted by postal mail informing them that a medically important result had been detected and advised that they attend an assigned study genetic counselor (GC) to review the finding.20 Participants who were unable to attend an in-person GC appointment had the option to receive results by telephone. Participants could opt-out from receiving their result consistent with ACMG guidelines.21 A detailed family history was obtained by the GC and a family pedigree chart (family tree) was constructed. Familial implications of the findings were discussed in all cases and information regarding family screening was provided to all participants. Following consultation with a GC, participants were referred to a specialist or to their primary care provider. In cases where a genetic diagnosis had been previously established and associated with appropriate follow up, no referral took place.

Data sources

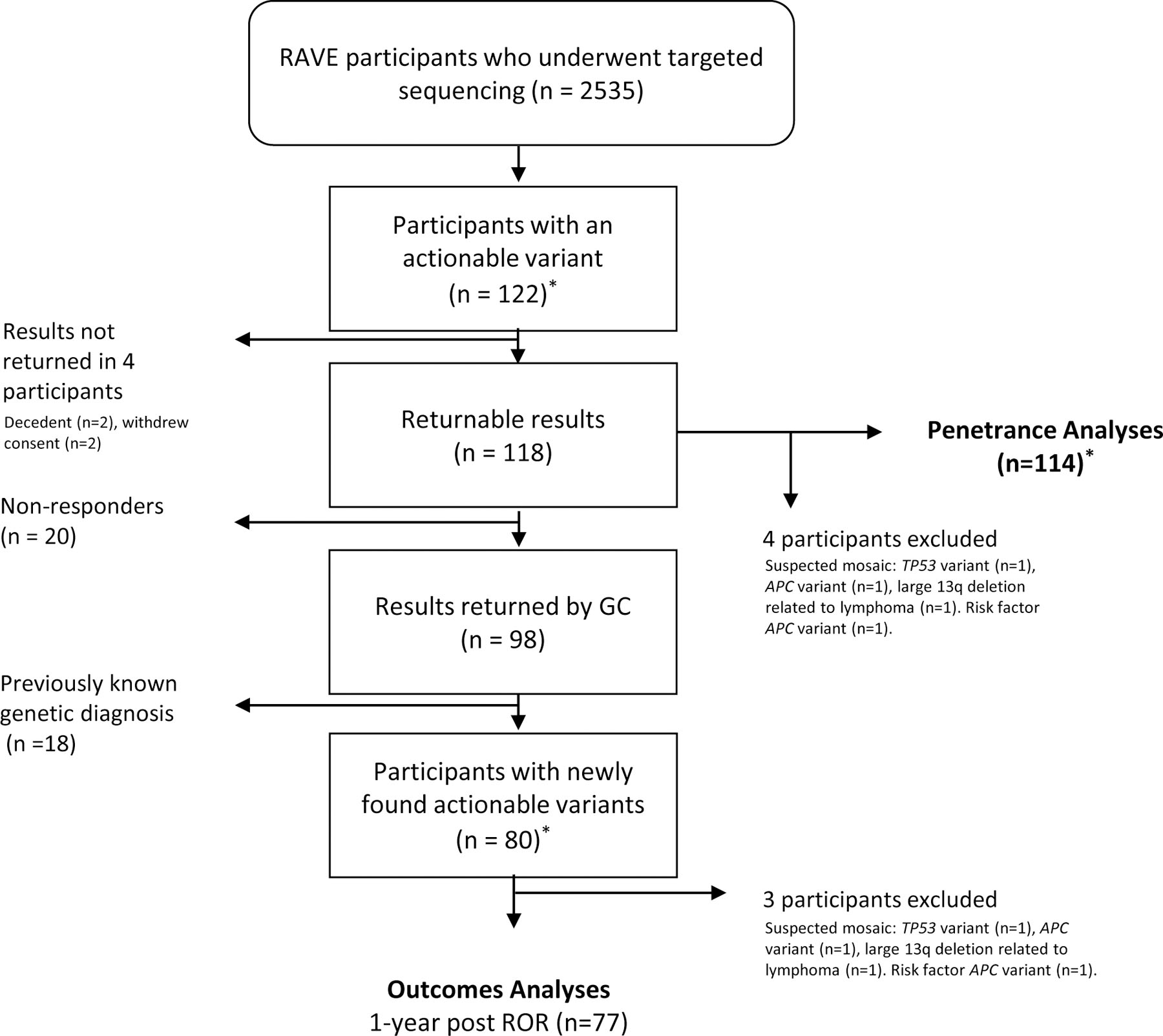

The study sample consisted of 122 participants who had actionable genomic results (Figure 1). Data including demographics, and prior diagnoses were abstracted from the Mayo Clinic EHR.22 Family history of the condition relevant to the actionable genomic result was ascertained from the detailed family pedigree drawn by the GC. A positive family history was defined as the presence of the relevant trait or condition in a first or second degree relative (Table 1 of the Supplement).

Figure 1. Participant Selection for Penetrance and Outcomes Analyses.

*Two participants had 2 actionable variants each; total number of actionable variants identified = 123

Outcomes were reviewed and categorized by Tier 1 and non-Tier 1 variants. For each participant with an actionable variant (list of actionable variants is in Table 2 of the Supplement), EHR data were abstracted separately by two of the three authors (CL, LA, FF). Any discrepancies in the abstraction were flagged and reviewed by a third author (OE) for resolution. Pre-RoR and post-RoR investigations were recorded as well as specialist evaluation.

Estimation of Penetrance.

Of 122 participants with actionable variants, we excluded 8 from the penetrance analyses (Figure 1). A variant was considered penetrant if a relevant trait or diagnosis was noted on EHR review (these traits/diagnoses are listed in Table 3 of the Supplement). To estimate penetrance, a detailed review of the EHR including results of new tests ordered after RoR, was performed by at least two of three authors (CL, LA, FF); any discrepancies were flagged and reviewed by a third author (OE). We considered P/LP variants in BRCA1/BRCA2 to be penetrant if the participant had undergone prophylactic bilateral mastectomy. Penetrance was compared between Tier 1 and non-Tier 1 variants.

Measurement of Outcomes.

Outcomes were ascertained by manual EHR review by at least two of three authors (CL, LA, FF); any discrepancies were flagged and reviewed by a third author (OE). Only outcomes clearly attributable to RoR based on EHR review were counted. For outcomes analyses we excluded participants who did not respond for result disclosure (n=20) and those who had previously known of the results or had somatic mosaicism (n=21). The latter group comprised 13 participants with returned Tier 1 variants of whom 12 already knew their results and 1 participant with a large 13q deletion likely secondary to mosaicism; and 8 participants with returned non-Tier 1 returned variants of whom 6 already knew their results and 2 with suspected mosaicism (Figure 1). We did review outcomes in participants with a previously recognized variant prior to study RoR (n=18) and present these separately in Table 4 of the Supplement. We classified outcomes based on a framework previously suggested by Williams23 and Peterson et al.24 as: a) process outcomes (referral to a specialist, new tests, initiation of surveillance); b) intermediate outcomes (new diagnoses, positive findings on tests); and c) clinical outcomes (modification of drug therapy, risk reducing surgery or procedure). The intermediate outcome ‘new diagnoses’ includes any new diagnoses related to the returned results. This includes diagnoses such as ‘carrier of high-risk variant for HBOC’ in addition diagnoses that reflect the presence a known related phenotype such as breast cancer. Process, intermediate and clinical outcomes were compared between Tier 1 and non-Tier 1 conditions.

Bias

The diversity in the study cohort was limited; the majority of participants who had results returned were white (96.7%), with a high proportion having college (59%) or graduate (19%) education. The efficiency of a tertiary care center and the available resources may not be representative of other healthcare settings.25 The average age of participants with returned variants was 62.5 years, possibly conferring a survivor bias. Ascertainment of the study cohort based on hypercholesterolemia and colon polyps may affect generalizability of this study to the population.

Study size

The maximal sample size was determined by the funding agency. Each eMERGE site could enroll up to 3000 participants. This report is based on the 2535 individuals enrolled at Rochester MN.

Quantitative variables/groupings

Outcomes were analyzed stratifying by Tier 1 vs Tier 2 conditions. Tier 1 conditions include Familial Hypercholesterolemia (LDLR, APOB, PCSK9), Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer syndrome (HBOC) (BRCA1 and BRCA2), and Lynch syndrome (MLH1, MSH2 MSH6, PMS2).26

Statistical methods

Initial evaluations of the data included general inspection of the raw data, examination of outliers and group distributions, and evaluation of missing data. The ages of participants with Tier 1 and non-Tier 1 conditions were compared by t-test. The frequencies (%) of categorical factors were compared between Tier 1 and non-Tier 1 conditions using 2-Tail Fisher’s exact test.

RESULTS

Out of 2535 participants, 122 (4.8%) had actionable results and 2% had actionable variant in genes related to Tier 1 disorders. 20 Table 2 of the Supplement lists each variant returned along with its pathogenicity classification and whether a relevant phenotype was present. Of 122 participants with actionable results, 20 did not respond to invitations for RoR, two opted out of receiving their results, and two died prior to RoR. Of the remaining participants, 18 had an existing diagnosis of the exact variant discovered as part of this study, as confirmed by EHR review (Figure 1); 77 participants had results returned and outcomes were assessed at 1-year post RoR. Actionable variants were categorized as related to either Tier 1 or non-Tier 1 conditions. Participant characteristics, overall and stratified by the presence of a Tier 1 disorder are summarized in Table 1. The median age of participants at the time of RoR was 63 years (IQR=8 years, range 34–73) and 59.8% were female. Results were disclosed by a GC in-person in 86 (70.4%) cases and by telephone in 12 cases (9.8%). Family history relevant to the actionable genomic result was present in 24 (31%) of 77 participants enrolled in the outcomes analysis; those with a variant related to a Tier 1 condition were more likely to have a positive family history than those with a variant related to a non-Tier 1 condition (44.4% vs. 19.5%, P=0.026)

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants with an Actionable Variant

| Characteristic |

n=122 |

Tier 1 n=59 |

non-Tier 1 n=63 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63 (8) | 63 (8) | 63 (9) | 0.09 |

| Female | 73 (59.8) | 35 (59.3) | 38 (60.3) | 0.82 |

| Whites | 118 (96.7) | 57 (96.6) | 61 (96.8) | 1 |

| Education | ||||

| High school | 23 (18.8) | 11 (18.6) | 12 (19) | 1 |

| College (1 – 4 yrs.) | 64 (52.4) | 36 (61) | 28 (44.4) | 0.10 |

| Graduate school education | 23 (18.8) | 8 (13.5) | 15 (23.8) | 0.16 |

| Return of results | ||||

| Disclosed by GC in person | 86 (70.4) | 43 (72.9) | 43 (68) | 0.69 |

| Disclosed by GC over telephone | 12 (9.8) | 5 (9) | 7 (11) | 0.76 |

| Non-responders | 20 (16.3) | 10 (17) | 10 (15.8) | 1 |

| Previously known genetic diagnosis | 18 (14.7) | 12 (20.3) | 6 (9.5) | 0.12 |

Age is presented as median (IQR), the remaining features are presented as n (percentage). Tier 1 conditions include Familial Hypercholesterolemia (LDLR, APOB, PCSK9), Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer syndrome (HBOC) (BRCA1 and BRCA2) and Lynch syndrome (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM).

Penetrance

An estimate of penetrance for each actionable variant is presented in Table 2. On average, the penetrance was higher in Tier 1 variants than non-Tier 1 variants; 67.2% (n=58 individuals) versus 46.5% (n=58 individuals) (P=0.03). Table 3 of the Supplement lists elements on EHR review that were used to determine whether a variant was penetrant. The penetrance of FH related variants was 92%; for HBOC related variants, the penetrance was 91% in females and 20% in males; and for Lynch syndrome variants, the penetrance was 20%. Penetrance varied in the three main subsets of non-Tier 1 variants: 7.7% in cardiomyopathy variants vs. 53.8% in arrhythmia variants and 75% in hemochromatosis variants. Cumulatively, 1 of 13 participants with cardiomyopathy variants and 7 of the 13 participants with long QT/Brugada syndrome variants (SCN5A, KCNQ1, KCNH2) manifested relevant traits. Relevant traits were present in 12 (4 male and 8 female) of the 16 participants (7 male and 9 female) homozygous for the c.845G>A variant in HFE that is associated with hemochromatosis. History of venous thromboembolism was present in one of four participants homozygous for the Factor V Leiden variant.27

Table 2.

Estimated Penetrance in 114a Participants with Actionable Variants (n=116)

| Gene | Disorder | Participants (n) | Relevant Traits Present (n) |

Penetrance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 variants | |||||

| LDLR | Familial hypercholesterolemia | 19 | 17 | 0.89 | |

| APOB | 6 | 6 | 1 | ||

| PCSK9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 26 | 24 | 0.92 | |||

| BRCA1 | Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome (HBOC) † | All | 7 | 6 (2) | 0.86 (0.28) |

| Males | - | - | - | ||

| Females | 7 | 6 (2) | 0.86 (0.28) | ||

| BRCA2 | All | 10 | 6 (2) | 0.6 (0.2) | |

| Males | 5 | 1 (1) | 0.2 (0.2) | ||

| Females | 5 | 5 (1) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| 17 | 12 (4) | 0.70 (0.23) | |||

| MSH6 | Lynch Syndrome | All | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Males | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Females | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| MSH2 | All | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Males | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Females | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| PMS2 | All | 9 | 1 | 0.11 | |

| Males | 3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Females | 6 | 1 | 0.16 | ||

| MLH1 | Males | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 15 | 3 | 0.20 | |||

| Overall penetrance of Tier 1 variants | 58 | 39 | 0.67 | ||

| Non-Tier 1 Variants | |||||

| APC | FAP | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| TNNI3 | Dilated cardiomyopathy | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| MYPBC3 | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| MYH7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| MYL3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| DSC2 | ARVC | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| PKP2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| DSP | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| KCNQ1 | Long QT syndrome | 6 | 3 | 0.5 | |

| KCNE1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||

| KCNH2 | 3 | 2 | 0.66 | ||

| SCN5A | Brugada/Long Q-T syndrome | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| COL3A1 | EDS, vascular type | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| FBN1 | Marfan syndrome | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| HFE | Hereditary hemochromatosis | All | 16 | 12 | 0.75 |

| Male | 7 | 4 | 0.57 | ||

| Female | 9 | 8 | 0.88 | ||

| F5 | Thrombophilia | 4 | 1 | 0.25 | |

| PALB2 | Breast and pancreatic cancer | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| CHEK2 | Various types of cancer | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| RET | Multiple endocrine neoplasia II | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| CACNA1S | Hypokalemic periodic paralysis | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| ACADM | MCAD deficiency | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| RYR1 | Malignant hyperthermia | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Overall penetrance of non-Tier 1 variants | 58 | 27 | 0.46 | ||

| Overall penetrance | 116 | 66 | 0.57 | ||

The lower bound of penetrance estimates for HBOC are shown in parentheses the lower estimate includes only those in whom a related cancer was observed and not those who underwent prophylactic mastectomy. MCAD = medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, ARVC = arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, EDS = Ehlers Danlos syndrome.

Two participants had two P/LP variants. Additional details of relevant traits are provided in the supplementary material.

Outcomes

The occurence of outcomes was stratified by Tier 1 (FH, HBOC and Lynch syndrome) vs non-Tier 1 variants, as summarized in Table 3. Of 77 participants with newly identified P/LP variants or actionable SNVs as part of our study, 83% had one or more outcomes following RoR; 77.9% had a process outcome – referral to a specialist (64.9%), new testing (66.2 %), surveillance initiation (38.9%); 67.9% had an intermediate outcome – new test finding (19.48%) or diagnosis (62.3%); 19.2% had a clinical outcome – risk reduction surgery (7.8%) or modification of therapy (11.7%). Risk reduction surgery occurred more often in participants with Tier 1 than those with non-Tier 1 actionable variants. Clinical outcomes in 18 participants with previously known genetic diagnosis are summarized in Table 4 of the Supplement.

Table 3.

1-Year Outcomes after Return of Results.

| Overall n=77 |

Tier 1 n=36 |

non-Tier 1 n=41 |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.5 (8.75) | 62.5 (7.25) | 64 (9) | 0.08 |

| Female | 43 (55.8) | 19 (52.8) | 24 (58.5) | 0.65 |

| Family history | 24 (31) | 16 (44.4) | 8 (19.5) | 0.026 |

| Any outcome | 64 (83.1) | 26 (72.2) | 38 (92.7) | 0.030 |

| Process Outcomes | 60 (77.9) | 26 (72.2) | 34 (82.9) | 0.28 |

| Referral to a specialist | 50 (64.9) | 23 (63.9) | 27 (65.8) | 1 |

| Investigations based on RoR | 51 (66.2) | 24 (66.7) | 27 (65.8) | 0.52 |

| Surveillance initiated | 30 (38.9) | 18 (50) | 12 (29.2) | 0.10 |

| Intermediate Outcomes | 53 (67.9) | 23 (63.9) | 30 (71.4) | 0.62 |

| New tests finding | 15 (19.48) | 6 (16.7) | 9 (21.9) | 0.77 |

| New diagnosis | 48 (62.3) | 21 (58.3) | 27 (65.8) | 0.63 |

| Clinical Outcomes | 15 (19.2) | 9 (25) | 6 (14.3) | 0.38 |

| Risk reduction surgery | 6 (7.8) | 6 (16.7) | 0 | <0.01 |

| Medication or therapy started/altered | 9 (11.7) | 3 (8.33) | 6 (14.63) | 0.35 |

Age is presented as median (IQR); the remaining features are presented as n (percentage)

Tier 1 Conditions

Outcomes observed in participants who received Tier 1 results are summarized in Table 4. Of 36 participants with newly identified P/LP Tier 1 variants, 72% of participants had one or more outcomes following RoR; 72% had a process outcome – referral to a specialist (63.9%), new testing (66.7%), surveillance initiation (50%); 64% had an intermediate outcome – new test finding (16.7%) or diagnosis (58%); 25% had a clinical outcome – risk reduction surgery (16.7%) or modification of therapy (8.3%). Additional details are available in the Supplemental material (Table 4; Tables 5-7 and Figures 1-3 of the Supplement).

Table 4.

Outcomes in 77a Participants with Newly Identified Variants (n=79).

| Disorder | Gene (n of participants) |

Process Outcomes | Intermediate Outcomes | Clinical Outcomes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referral to specialist (n=50) | Tests performed (n=51) | Surveillance (n=30) | New test findings (n=15) | New diagnosis (n=48) | Change in therapy (n=9) | Risk reduction surgery (n=6) | ||

| Tier 1 variants | ||||||||

| Familial Hypercholesterolemia n=18 |

LDLR (14) APOB (3) PCSK9 (1) |

9 | (n=10) Lipoprotein (a) (5) Apo B (6) Lipid Panel (9) CT Coronary Calcium (4) ECG (7) Stress Echocardiogram (2) |

4 | 3 | 7 | Statin dose increased (1) Ezetimibe started (2) |

— |

| Lynch Syndrome n=10 |

PMS2 (8) MSH6 (2) 6 females 4 males |

9 | (n=8) Colonoscopy (7) Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (5) Transvaginal Pelvic Ultrasound (2) Urine Cytology (2) |

8 | 2 | 8 | — | Hysterectomy and bilateral salphingo-oophorectomy (3) |

| Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome n=8 |

BRCA2 (7) BRCA1 (1) 3 females 5 males |

5 | (n=6) MRI Breast (3) Mammogram (1) Ca 125 (1) Pelvic U/S (1) PSA (2) |

6 | 1 | 6 | — | Mastectomy (3) |

| Non-Tier 1 Variants | ||||||||

| Hypertrophic/Dilated Cardiomyopathy n=7 |

MYBPC3 (3), TNNI3 (2), MYH7 (1), MYL3 (1) | 5 | (n=4) Echocardiogram with strain (4) ECG (3) Cardiac MRI (2) 24h Holter (2) |

4 | 1 | 3 | Verapamil replaced with Metoprolol (1) | — |

| Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy n=4 |

DSC2 (1), DSP (1), PKP2 (2) | 3 | (n=3) Standard ECG (3) Signal-Averaged ECG (2) Exercise Test (3) Echocardiogram (2) 24h Holter (3) Cardiac MRI (2) |

1 | — | 3 | — | — |

| Long Q-T/Brugada Syndrome n=10 |

KCNQ1 (4), KCNE1(2), SCN5A (2), KCNH2 (2) | 9 | (n=8) 24h Holter (5) ECG (8) Brugada Protocol ECG (2) Signal-Averaged ECG (2) Exercise Test (5) Echocardiogram (4) |

1 | 3 | 7 | Nadolol Started (1) | — |

| Ehlers-Danlos n=1 |

COL3A1 (1) | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | — | — |

| Hemochromatosis n=8 |

HFE (8) | 3 | (n=7) Iron studies (7) Liver MRI (3) Cardiac MRI (1) LFTs (3) |

3 | 4 | 7 | Therapeutic Phlebotomy Started (3) | — |

| Factor V Leiden n=4 |

F5 (4) | 1 | — | — | — | 1 | Rivaroxaban started (1) | — |

| Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type IIA n=2 |

RET (2) | 2 | (n=2) Calcitonin (2) PTH (2) Calcium (2) Albumin (2) Vitamin D (2) 24h metanephrines (2) 24h urinary calcium (2) Thyroid U/S (2) |

1 | — | 2 | — | — |

| Familial Adenomatous Polyposis n=1 |

APC (1) | 0 | 0 | — | — | 1 | — | — |

| Breast and Colorectal Cancer Risk n=2 |

CHEK2 (2) | 1 | Mammogram (1) |

1 | 1 | — | — | — |

| Breast and Pancreatic Cancer Risk n=2 |

PALB2 (2) | 1 | (n=2) Mammogram (1) Breast MRI (1) PSA (1) |

1 | — | 1 | — | — |

| MCAD Deficiency n=1 |

ACADM (1) | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Malignant Hyperthermia n=1 |

RYR2 (1) | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | — |

n = number of participants; Apo B =apolipoprotein B; CT = computed tomography; ECG = electrocardiogram; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; Ca 125 = cancer antigen 125; U/S = ultrasound; PSA = prostate specific antigen; LFTs = liver function tests; PTH = parathyroid hormone; MCAD = medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase

2 participants had P/LP variants identified in 2 genes.

Non-Tier 1 Conditions

Of 41 participants with newly identified non-Tier 1 P/LP variants or actionable SNVs, 92.7% had one or more outcomes following RoR; 82.9% had a process outcome – referral to a specialist (65.8%), new testing (65.8%), surveillance initiation (29.2%); 71.4% had an intermediate outcome – new test finding (21.9%) or diagnosis (65.8%); 14.3% had a clinical outcome – risk reduction surgery (0%) or therapy modified (14.63%). Additional details are available in the Supplemental material (Table 4; Tables 8-10 and Figures 4-5 of the Supplement).

Comparison of Outcomes in Participants with Tier 1 vs. Non-Tier 1 Variants

Overall, outcomes occurred more frequently in those with non-Tier 1 variants (92.7%) vs. participants with Tier 1 variants (72.2%) (Table 3). This was because participants with non-Tier 1 variants tended to have higher occurrence of process and intermediate outcomes.

DISCUSSION

Essential elements of translational research to evaluate use of genome sequencing in primary care and population screening have been proposed,28 and there is an urgent need to develop this agenda, given the relatively sparse data for clinical validity and utility.11 In particular, data about penetrance of actionable variants and outcomes after their return is needed prior to adoption of genome sequencing in the clinical setting. In the present study, placing genome sequencing results in the EHR enabled subsequent assessment of penetrance and outcomes. The penetrance of actionable variants, on average was 67% for Tier 1 variants and 46.5% for non-Tier 1 variants. While the majority (77.9%) of the 77 participants who received a previously unknown actionable result, experienced a ‘process’ outcome, 67.9% had intermediate outcomes and 19.2% had clinical outcomes, motivating longer term follow up of larger cohorts to assess changes in health outcomes.

Penetrance

Estimates of penetrance of P/LP variants have not been fully defined4,29–31 and are needed to guide patients, family members, and clinicians on appropriate health management decisions. Linkage of genomic data to phenotypes in the EHR in the present study enabled us to ascertain traits/conditions relevant to an actionable variant which we used as surrogate for penetrance. The penetrance of FH related P/LP variants was 92%, likely an inflated estimate resulting from selection of participants based on elevated cholesterol levels. Prior studies have reported penetrance of 70–90% in FH variants.32 For HBOC related variants, the penetrance was 91% in females and 20% in males, similar to what has been previously reported (87% in females and 20% in males).33 The penetrance of Lynch syndrome variants was 20%, lower than prior reports of 50–60%.34,35 The lower penetrance of Lynch syndrome variants is potentially related to the predominance of PMS2 variants (n=9) which are associated with a substantially lower risk of cancer compared to the other variants associated with colorectal cancer.36 The penetrance of non-Tier 1 variants was 46.5%, with variability in the three main subsets: 7.7% in cardiomyopathy variants vs. 53.8% in arrhythmia variants and 75% in hemochromatosis variants.

Several caveats need to be considered in interpreting estimates of penetrance and these should be considered preliminary, with need for additional studies. First, as mentioned above, penetrance estimates for FH variants could be inflated given the ascertainment of participants based on presence of elevated LDL-cholesterol. Second, new evidence of ‘penetrance’ could manifest with additional testing in the future and with longer follow-up; however, the likelihood in this cohort is low, given the mean age of the participants at the time of testing (~63 years). Third, absence of clinical features that are associated with a P/LP variant may be due to truly reduced penetrance, absence of relevant phenotyping information (e.g., ECG or echocardiograms), or an insufficient follow-up period.37 Fourth, survival bias may affect the estimates.

In 2013, the ACMG issued a statement recommending consideration of the return of actionable variants from 56 genes (ACMG 56)13 sequenced in a clinical setting to participants/patients. However, several of the P/LP variants in the genes on this list appear to have uncertain or low penetrance in asymptomatic individuals, prompting the ACMG to issue a recent statement discouraging the return of secondary findings detected as part of population screening.2 Further, the statement highlights the need for reliable estimates of penetrance obtained through robust genotype-phenotype correlation studies and research to establish the efficacy of interventions in asymptomatic patients with P/LP variants.2 Of note we did not find penetrance estimates to be different in P vs. LP variants (55.2% vs 60%, P =0.69; analyses not shown)

Outcomes

For appropriate adoption of genomic medicine it is important to measure outcomes consequent to return of sequencing results.24 Clinical utility encompasses several domains.38 As a step towards assessing clinical utility after RoR in a targeted genomic medicine study, we ascertained near term (1-year) outcomes (process, intermediate and clinical) using a previously recommended framework.24 Most outcomes were process outcomes, but intermediate and clinical outcomes occurred in significant proportions, 67.9% and 19.2%, respectively. When examining specific subsets of outcomes, risk reduction surgery occurred more often in participants with Tier 1 than in those with non-Tier 1 actionable variants (Table 3) but no significant differences were noted for the remaining subsets of outcomes.

The prevalence of actionable variants in the RAVE study was 4.8%, higher than previously reported39 and the prevalence of Tier 1 variants was 2%, twice of what expected in a population-based sample, likely due to enrichment for participants with hypercholesterolemia. Less than half of individuals with Tier 1 variants had family history of the related disorder, indicating that population genomic screening would identify a substantial proportion of individuals at risk for coronary heart disease, HBOC and colorectal cancer, and who would not have had an indication for genomic testing. These findings are consistent with those of a UK Biobank study, in which ~60% of individuals with Tier 1 variants did not have a relevant family history.40 Several participants in our study underwent potentially life-altering interventions. For example, after learning about having a pathogenic BRCA2 variant and a subsequent abnormal mammogram, a female participant opted for bilateral mastectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

It has been argued that genomic testing should focus on diseases with strong genotype–phenotype correlation, high penetrance, the effects of the disease are serious, there are options for prevention and/or treatment, and the net costs incurred are acceptable for the health gains achieved.41 Compared to those with Tier-1 variants, participants with non-Tier 1 variants tended to experience process outcomes more often than, manifested the relevant trait/s in the EHR less often and had a lower prevalence of family history of the relevant disease. These results motivate additional scrutiny of the costs and long-term outcomes following return of non-Tier 1 secondary findings to assess the balance between risk reduction versus increased health-care overutilization.11,42

Strengths of this study include selection of the participants based on the presence of hypercholesterolemia and/or colon polyps to emulate real world practice patterns where individuals are likely to undergo sequencing based on a specific indication, essentially to screen for Tier-1 disorders in an at risk population. Participants were recruited from a defined geographic area of Southeast Minnesota, enabling nearly complete capture of outcomes 1-year after RoR since the majority of individuals residing in this area receive care at the Mayo Clinic Rochester Minnesota or the Mayo Health System and have associated follow up and referrals completed within this system.

Several limitations of the present study should be noted. Our data is observational since randomized controlled trials to assess outcomes based on returning versus not returning results are challenging to conduct given the actionable nature of genetic findings. The number of participants with actionable results was relatively modest and a meta-analysis of multiple genomic sequencing studies will be necessary to create an evidence base to inform appropriate implementation of genomic sequencing in clinical and public health contexts.12,43 Our report is limited to near-term outcomes and further work is needed to assess costs and health care utilization, sharing of genetic results with family members, psychosocial changes and long-term changes in health outcomes.

Conclusion

We report results regarding penetrance and 1-year clinical outcomes of actionable variants identified by targeted sequencing as part of a genomic medicine implementation study. Penetrance, estimated based on presence of relevant traits in the EHR, was 57% on average; process outcomes were noted in the majority (77.9%), whereas intermediate and clinical outcomes occurred in 67.9% and 19.2% of participants, respectively. Both penetrance and outcomes differed based on Tier 1 vs. non-Tier status. Penetrance was higher in participants with Tier 1 actionable variants (67% vs. 46.5%). Overall, outcomes occurred more frequently in those with non-Tier 1 variants (92.7% vs. 72.2%) whereas risk reduction surgery occurred more often in participants with Tier 1 actionable variants (16.7% vs. 0%). Our study provides estimates of penetrance of actionable genomic variants identified by targeted sequencing and adds to the growing body of literature reporting outcomes following return of such variants to patients and clinicians. Additional studies of larger cohorts followed over a longer period are necessary to assess changes in health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The RAVE study was funded as part of the NHGRI-supported eMERGE (Electronic Records and Genomics) Network (U01HG006379) and by the Mayo Center for Individualized Medicine. IJK was additionally funded by K24 HL137010.

Footnotes

ETHICS DECLARATION

RAVE study candidates were asked to complete a study consent form, health questionnaires and provide a blood sample (if an existing sample was not available) to participate in this study. This study and the informed consent process were approved by the Mayo Institutional Review Board. Information about the Mayo Clinic Biobank’s collection and enrollment methods are described here: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24001487/.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare they have no disclosures regarding conflict of interest with respect to this manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data is deposited in dbGAP (accession code phs001616.v2.p2)

REFERENCES

- 1.Feero WG, Wicklund CA, Veenstra D. Precision medicine, genome sequencing, and improved population health. JAMA 2018;319:1979–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ACMG Board of Directors. The use of ACMG secondary findings recommendations for general population screening: a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med 2019;21:1467–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hosseini SM, Kim R, Udupa S, et al. Reappraisal of reported genes for sudden arrhythmic death: Evidence-based evaluation of gene validity for Brugada Syndrome. Circulation 2018;138:1195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Natarajan P, Gold NB, Bick AG, et al. Aggregate penetrance of genomic variants for actionable disorders in European and African Americans. Sci Transl Med 2016;8:364ra151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah N, Hou YC, Yu HC, et al. Identification of misclassified ClinVar variants via disease population prevalence. Am J Hum Genet 2018;102:609–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright CF, West B, Tuke M, et al. Assessing the pathogenicity, penetrance, and expressivity of putative disease-causing variants in a population setting. Am J Hum Genet 2019;104:275–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khoury MJ. No shortcuts on the long road to evidence-based genomic medicine. JAMA 2017;318:27–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones LK, Kulchak Rahm A, Manickam K, et al. Healthcare utilization and patients’ perspectives after receiving a positive genetic test for familial hypercholesterolemia. Circ Genom Precis Med 2018;11:e002146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchanan AH, Lester Kirchner H, Schwartz MLB, et al. Clinical outcomes of a genomic screening program for actionable genetic conditions. Genet Med 2020;22:1874–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams JL, Chung WK, Fedotov A, et al. Harmonizing outcomes for genomic medicine: Comparison of eMERGE outcomes to ClinGen outcome/intervention pairs. Healthcare (Basel) 2018;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hart MR, Biesecker BB, Blout CL, et al. Secondary findings from clinical genomic sequencing: prevalence, patient perspectives, family history assessment, and health-care costs from a multisite study. Genet Med 2019;21:1100–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vassy JL, Christensen KD, Schonman EF, et al. The impact of whole-genome sequencing on the primary care and outcomes of healthy adult patients: A pilot randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:159–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ, et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med 2017;19:249–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.eMERGE Clinical Annotation Working Group. Frequency of genomic secondary findings among 21,915 eMERGE network participants. Genet Med 2020;22:1470–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kullo IJ, Olson J, Fan X, et al. The Return of Actionable Variants Empirical (RAVE) Study, a Mayo Clinic Genomic Medicine Implementation Study: Design and initial results. Mayo Clin Proc 2018;93:1600–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dotson WD, Douglas MP, Kolor K, et al. Prioritizing genomic applications for action by level of evidence: a horizon-scanning method. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2014;95:394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007;370:1453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olson JE, Ryu E, Johnson KJ, et al. The Mayo Clinic Biobank: a building block for individualized medicine. Mayo Clin Proc 2013;88:952–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015;17:405–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kochan DC, Winkler E, Lindor N, et al. Challenges in returning results in a genomic medicine implementation study: the Return of Actionable Variants Empirical (RAVE) study. NPJ Genomic Med 2020;5:19. doi: 10.1038/s41525-020-0127-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ACMG Board of Directors. ACMG policy statement: updated recommendations regarding analysis and reporting of secondary findings in clinical genome-scale sequencing. Genet Med 2015;17:68–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams MS. Early lessons from the implementation of genomic medicine programs. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2019;20:389–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson JF, Roden DM, Orlando LA, Ramirez AH, Mensah GA, Williams MS. Building evidence and measuring clinical outcomes for genomic medicine. Lancet 2019;394:604–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaibi GQ, Kullo IJ, Singh DP, et al. Returning genomic results in a federally qualified health center: The intersection of precision medicine and social determinants of health. Genet Med 2020;22:1552–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tier 1 Genomics Applications and their Importance to Public Health CDC, 2014. (Accessed May 9th, 2019, at https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/implementation/toolkit/tier1.htm.)

- 27.Gallego CJ, Burt A, Sundaresan AS, et al. Penetrance of hemochromatosis in HFE genotypes resulting in p.Cys282Tyr and p.[Cys282Tyr];[His63Asp] in the eMERGE Network. Am J Hum Genet 2015;97:512–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khoury MJ, Feero WG, Chambers DA, et al. Correction: A collaborative translational research framework for evaluating and implementing the appropriate use of human genome sequencing to improve health. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manickam K, Buchanan AH, Schwartz MLB, et al. Exome sequencing-based screening for BRCA1/2 expected pathogenic variants among adult biobank participants. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e182140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnston JJ, Lewis KL, Ng D, et al. Individualized iterative phenotyping for genome-wide analysis of loss-of-function mutations. Am J Hum Genet 2015;96:913–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haer-Wigman L, van der Schoot V, Feenstra I, et al. 1 in 38 individuals at risk of a dominant medically actionable disease. Eur J Hum Genet 2019;27:325–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Youngblom E, Pariani M, Knowles JW. Familial Hypercholesterolemia. 2014 Jan 2 [Updated 2016 Dec 8]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al. , editors. GeneReviews® [Internet] Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK174884/. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petrucelli N, Daly MB, Pal T. BRCA1- and BRCA2-Associated Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. 1998 Sep 4 [Updated 2016 Dec 15]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al. , editors. GeneReviews® [Internet] Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1247/. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohlmann W, Gruber SB. Lynch Syndrome. 2004 Feb 5 [Updated 2018 Apr 12]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al. , editors. GeneReviews® [Internet] Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1211/. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Møller P, Seppälä T, Bernstein I, et al. Cancer incidence and survival in Lynch syndrome patients receiving colonoscopic and gynaecological surveillance: first report from the prospective Lynch syndrome database. Gut 2017;66:464–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Senter L, Clendenning M, Sotamaa K, et al. The clinical phenotype of Lynch syndrome due to germ-line PMS2 mutations. Gastroenterology 2008;135:419–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Driest SL, Wells QS, Stallings S, et al. Association of arrhythmia-related genetic variants with phenotypes documented in electronic medical records. JAMA 2016;315:47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grosse SD, Khoury MJ. What is the clinical utility of genetic testing? Genet Med 2006;8:448–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dorschner MO, Amendola LM, Turner EH, et al. Actionable, pathogenic incidental findings in 1,000 participants’ exomes. Am J Hum Genet 2013;93:631–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel AP, Wang M, Fahed AC, et al. Association of rare pathogenic DNA variants for familial hypercholesterolemia, hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, and Lynch Syndrome with disease risk in adults according to family history. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doble B, Schofield DJ, Roscioli T, Mattick JS. Prioritising the application of genomic medicine. NPJ Gen Med 2017;2:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang L, Bao Y, Riaz M, et al. Population genomic screening of all young adults in a health-care system: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Genet Med 2019;21:1958–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McMurry AJ, Murphy SN, MacFadden D, et al. SHRINE: enabling nationally scalable multi-site disease studies. PLoS One 2013;8:e55811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is deposited in dbGAP (accession code phs001616.v2.p2)