Abstract

Background

Young adulthood (YA) is a complex phase of life, marked by key developmental goals, including educational and vocational attainment, housing independence, maintenance of social relationships, and financial stability. A cancer diagnosis during, or prior to, this phase of life can compromise the achievement of these milestones. Studies of adults with cancer have demonstrated that more than 70% report experiencing financial side-effects, which are associated with increased mortality, diminished health-related quality of life, and forgone medical care. The goal of this project is to evaluate financial distress of YA-aged survivors of blood cancers, and the impact of financial navigation on alleviating this distress.

Methods

This three-arm, multi-site, hybrid type 2 randomized effectiveness-implementation design (EID), study will be conducted through remote consent, remote data capture and telephone-based/virtual financial navigation. Participants will be aged 18–39, and more than three years from their blood cancer diagnosis. In this six-month intervention, the study will compare the primary outcome of financial distress in three arms: (1) usual care (2) participant-initiated, ad hoc navigation, and (3) study-directed proactive navigation. The study will be evaluated via the five-component Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) outcome strategy with a mixed-methods approach through quantitative assessment of participant-reported financial distress using the Personal Financial Wellness Scale™, as the primary outcome measure, and qualitative assessment through interviews.

Conclusion

The study will address many unanswered questions regarding financial navigation within the YA survivor population and will inform the most successful strategies to mitigate financial distress in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Oncology, Survivorship, Young Adult, Financial Distress, Navigation

Background

Young adulthood (YA) is a complex phase of life, marked by key developmental goals and milestones, including educational and vocational attainment, housing independence, creation and maintenance of intimate social relationships, and financial stability [1–3]. A diagnosis of cancer during or prior to this phase of life can compromise the achievement of these milestones. Studies of adults with cancer have demonstrated that more than 70% report experiencing financial side-effects of treatment [4], which are associated with increased mortality [5], diminished health-related quality of life (HRQL), and forgone medical care [6–10]. The impact of cancer on YA survivors’ ability to attain financial stability after their therapy ends and their associated levels of financial distress are less understood.

There is a growing number of YAs with a history of cancer in the United States (US). An estimated 10,470 children (<15 years) [11] and nearly 90,000 adolescents and young adults (15–39 years) are diagnosed annually, with five-year relative survival rates ranging from 83–86% [12]. Studies have demonstrated an increased risk of financial hardship among YA cancer survivors as compared to survivors of other age groups and YAs without cancer [6, 7, 10, 13–16]. While cancer may interfere with educational and vocational attainment, financial hardship can also impede educational and employment-related growth and financial stability [10, 13, 14]. YAs are less likely than older adults to have the financial reserves and experience to manage their medical bills and living expenses during cancer treatment [17]. Monetary and grant support is less available and harder to obtain for patients who have completed active treatment, yet many have ongoing medical care needs related to their cancer history. Moreover, access to financial support services varies and is influenced by personal and environmental characteristics, which may lead to substantial barriers to identifying and using financial supports [18, 19].

The goal of this project is to evaluate the impact of financial navigation in alleviating financial distress of YA survivors, currently 18–39 years old and more than three years from their blood cancer diagnosis. The focus is on blood cancer, including leukemia and lymphoma, as they commonly affect patients within this age group. Because of the well-established problem and urgency of financial distress in YA survivors, particularly within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and increase in nationwide financial hardship [20], this study was created with a blended effectiveness-implementation design (EID) [21] with the goal of accelerating the delivery of the intervention into practice with broad and timely reach to patients in need. In the spirit of meeting YAs “where they are” socially and technologically, the research team developed an innovative methodologic structure to engage survivors across the US, through remote consent, remote data capture and phone-based/virtual financial navigation.

Hybrid Type 2 Effectiveness-Implementation Design (HT2-EID)

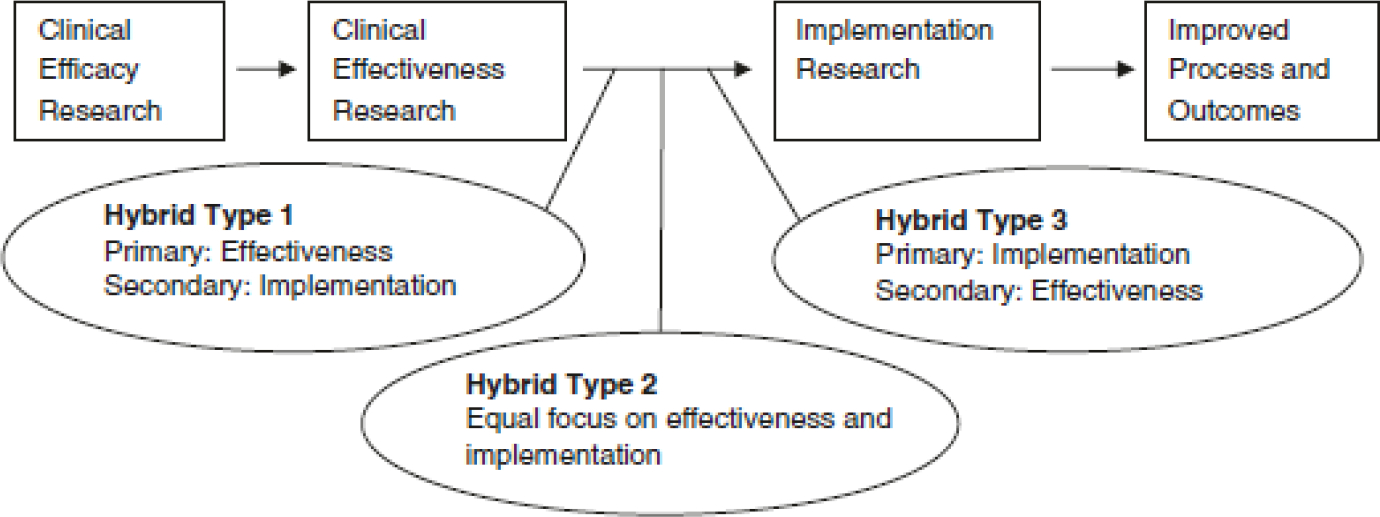

EID is a research methodology that helps translate clinical research into real-world practice more quickly than traditional research models [21]. EID research includes three different sub-types, which vary in their level of testing of the intervention’s effectiveness and implementation (Figure 1; Appendix A). This study implements a Hybrid Type 2 Design (HT2D) methodology, which focuses equally on the effectiveness and the implementation of an intervention. A key feature of the HT2D is developing a methodological “middle ground.” Curran et al., recommend that researchers adopt a “medium case, pragmatic set of delivery/implementation versus ‘best’ or ‘worst’ case conditions” [21]. In other words, researchers should avoid overly controlled or rigid conditions, as in traditional randomized control trial (RCT), but rather should aim for a “medium” approach whereby they deliver the intervention with enough flexibility to incorporate real life variability and diversity.

Figure 1.

Hybrid effectiveness-implementation designs as part of the clinical research continuum [22]

Study Design

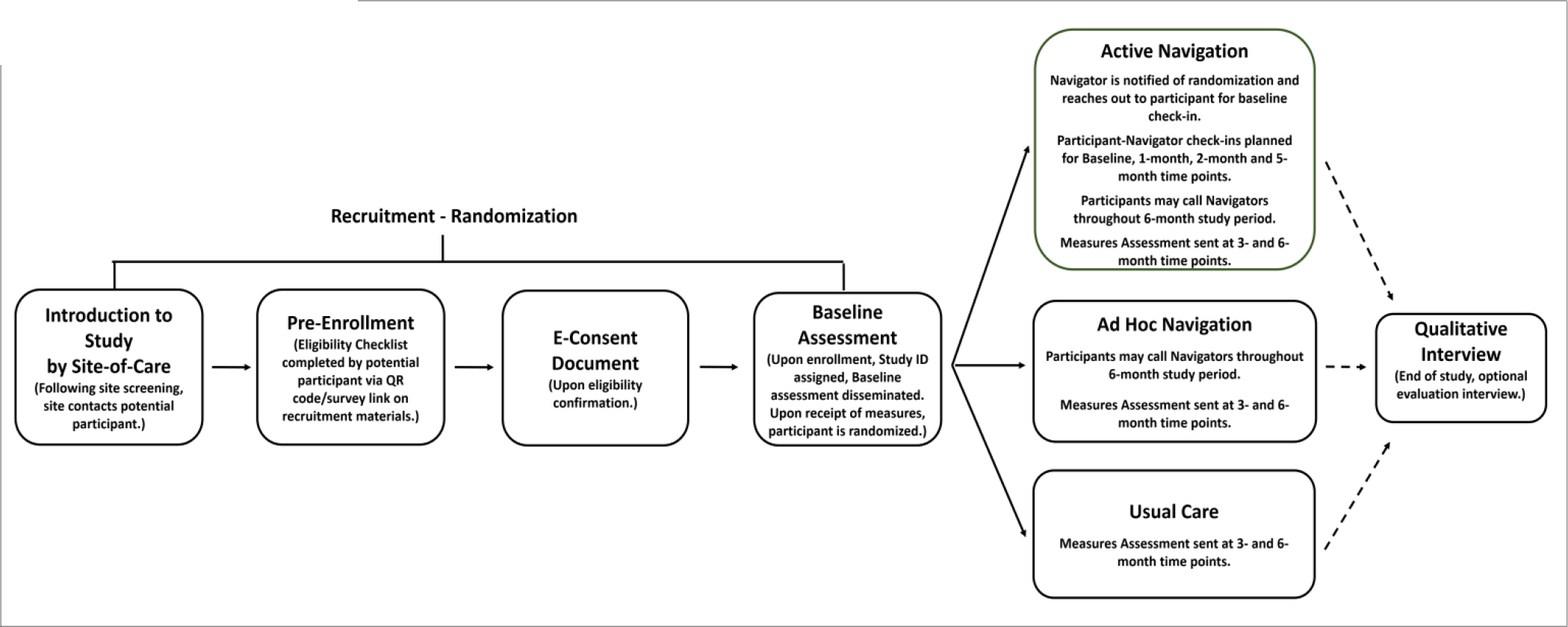

This remote study is a multi-site (n=6), randomized HT2-EID. The six-month study will implement a randomized comparison between YAs assigned to one of three arms: (1) usual care (2) participant-initiated, ad hoc financial navigation (ad hoc), or (3) study-directed pro-active financial navigation (active) with four scheduled check-ins (Figure 2). The ad hoc group, in particular, will reflect the EID real world methodology with engagement based upon the participant’s individual needs and their own outreach to the Financial Navigator (FN). Randomization will occur upon completion of baseline measures. This study will be evaluated via the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) outcome strategy [23] with a mixed-methods approach through quantitative assessment of participant-reported financial distress using the Personal Financial Wellness Scale™ (PFW) [24, 25] as the primary outcome measure, and qualitative assessment through interviews.

Figure 2.

Study and Database Design Flow

Tufts Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study in the fall of 2021 (STUDY00001828). The Tufts IRB is the reviewing IRB for five participating sites of care that will serve as recruitment sites. Tufts Medical Center (MC) will be responsible for all aspects of study administration from consenting through analysis. Recruitment activity at the participating sites is overseen via Reliance Agreements through the Smart IRB [26], where deemed necessary by the local institutions. In lieu of a Data and Safety Monitoring Board, we have developed a Data and Safety Monitoring Plan, which focuses on participant safety and data quality. Recruitment began at Tufts MC in February 2022.

Study Database

Data will be collected and stored within a dedicated study database built in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap™), a secure, web-based, HIPAA compliant application for research and clinical data [27, 28]. As part of the recruitment process, potential participants will be asked to complete an eligibility checklist built as a REDCap™ survey. Following eligibility confirmation, consent certification, randomization, measure dissemination and responses, along with content from navigator encounters will all be captured in this database. The database will send automated reminders and notifications to both the study team (via email to the study team inbox) and the participants (via their preferred mode: email or text message sent through Twilio, an integrated third-party service) [29].

Study Aims

The study is designed to address three aims.

Aim 1: Evaluate the effectiveness of the FN intervention among YA blood cancer survivors in reducing self-reported cancer-related financial distress, using the PFW, at 3- and 6-months compared to study baseline.

Hypothesis: Those randomized to study-directed active FN will demonstrate greater improvement in PFW scores by 6-months than those randomized to usual care or ad hoc navigation.

Aim 2: Describe differences at study baseline in self-reported cancer-related financial distress, using the PFW and demographic characteristics, among YA blood cancer survivors.

Hypothesis: Vulnerable patients, defined by lower socio-economic status, geography, or traditionally underrepresented racial or ethnic groups will have greater financial distress at study entry.

Aim 3: Evaluate the intervention’s performance through the RE-AIM framework.

Participating Sites

In addition to Tufts MC, potential participants will be invited to join the study through their site of care at five other YA cancer programs located across the US (three programs in Los Angeles, CA; Houston, TX; and Greenville, SC). Research partners were selected based on their strong commitment to the YA population and to reflect state-level variability related to Medicaid expansion and availability of health exchange products. All of the sites provide care to a sizeable (~30%), historically underrepresented populations, defined by racial, ethnic, geographic (i.e., urban vs. rural), and socio-economic diversity.

Sample Size and Randomization

A total of 240 participants will be randomized, with 80 participants allocated to each arm (active, ad hoc, usual care). Sample sizes from each site will vary based on available patients. Randomization will be stratified by site and age at cancer diagnosis (<18 or ≥18 years old). Age 18 was chosen as most pediatric cancers are treated within academic medical centers, as compared to older patients, where care can be delivered in either community oncology or academic settings [30, 31]. In addition, while there are several federal entitlement programs in place for children to help defray cost, many end at age 18.

Randomization will use permuted blocks to achieve better balance in sample size across arms. The three CA hospitals will be split into two subsites based on different patient populations and IRB oversight. Participants from two sites (Tufts MC, SC) will only be allocated to two arms (active, ad hoc) because they have FNs on staff as part of their program’s services. While participants from those sites may not all be aware or taken advantage of local navigation services, the study team felt those participants could not be offered less than what was available at site of care, pursuant the Declaration of Helsinki [32]. Participants from the other four sites (TX, CA) will be allocated to one of the three arms (active, ad hoc, usual care). (See Appendix B-Estimated Randomization Allocation by Site Table B.1).

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion

This study will include YAs currently aged 18–39 years old, who reside in the US and are able to understand and read English as study-based FN are English-speakers. Participants must have a history of a blood cancer diagnosed during childhood (0–17 years of age) or young adulthood (18–39 years of age). Eligibility is deliberately broad, consistent with a HT2-EID design. Participants will be at least three years post blood cancer diagnosis and be off treatment for their blood cancer or on a long-term regimen with an oral anti-cancer medication with stable disease. This will capture participants who are more distant from active treatment and, thus, more likely to be clinically stable with less risk for disease relapse. Individuals off treatment have longer interval follow-up and are less likely to have direct access to hospital staff and financial resources. They will also be off treatment for any secondary cancer or on a stable long-term regimen, such as hormone therapy or hormone replacement therapy. Pregnant women are eligible. Participants who are covered on a spouse’s insurance plan would be eligible to participate as would those uninsured. While primary place of residence is the US is a criteria, patients will not be screened with respect to citizenship or documentation.

Exclusion

YA survivors who are covered under their parent or guardian’s medical insurance will be excluded because they are likely not involved in the selection of the insurance plan and are not as likely to know the details of their parents’ insurance (such as annual deductible, out of pocket exposure) or be responsible for payment.

Screening and Recruitment

Participating sites will determine potentially eligible survivors by utilizing existing programmatic databases or consulting the electronic health record for general information about age, diagnosis and treatment end date. The recruitment flyer, distributed to potentially eligible participants by the site research teams, contains a QR code, which takes the potential participant to an eligibility check list built into the study database. When the potential participant accesses the survey link and answers questions related to inclusion/exclusion criteria, they will receive confirmation of eligibility in real time. After eligibility is confirmed, the potential participant will be asked to supply contact information and their preferred mode of contact (i.e., text or email) for study questionnaires. If the person is not eligible they will be notified, thanked for their interest and no contact information will be collected.

Remote Consent

After the potential participant is confirmed eligible, they will receive the e-consent to review, sign, and certify. There are two approved versions of the consent, one for the 2-arm randomization sites and one for the 3-arm sites. The potential participant will receive two reminder messages, if the consent document has not been signed within a 28 day window.

Study Measures and Data Collection Schedule

Participants will be asked to complete serial assessments at three time-points as outlined in Table 1, with the goal of describing the sample and exploring potential effect modifiers. These assessments will include validated measures (six PROMIS™ [33–35] and one Neuro-QoL™ [33, 36] short forms), as well as modified items from population-based surveys (the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) [37] and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) [38]. Specific items developed by the study team include identifying barriers to ongoing care (e.g., access, cost) and if they had already sought assistance and from whom (e.g., care team, social worker, financial navigator). The validated, primary outcome of financial distress will be assessed using the 8-item PFW Scale. Demographics and medical history information will be collected at baseline. Socio-economic status will be defined based on education and household income. Electronic gift-cards will be disseminated at each assessment point, to participants who complete measures (Appendix C).

Table 1:

Study Measures and Navigator-Collected Data Schedule

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Assessment | 1 Month FN Check-In | 2 Months FN Check-In | 3 Month Assessment | 5 Months FN Check-In | 6 Months Assessment | |

| Participant-completed assessment ^ | ||||||

| Measure (description) | ||||||

| PROMIS™ (i.e., domains of physical function, fatigue, anxiety, depression, emotional support and general self-efficacy) & Neuro-QoL (i.e., cognition function) SFs | X | X | X | |||

| Baseline Survivorship Care Characteristics | X | |||||

| Baseline Health Insurance and Finances (e.g., insured/uninsured) | X | |||||

| PFW Scale (primary outcome measure) | X | X | X | |||

| Demographics (e.g., age, sex, household composition, race/ethnicity, education, household income) | X | |||||

| Medical Information (e.g. age of diagnosis, diagnosis, history of relapse) | X | |||||

| Follow-up Survivorship Care, Health Insurance and Finances | X | X | ||||

| Study Evaluation | X | X | ||||

| Evaluation – optional interview | X | |||||

| Navigator-collected data | ||||||

| Check-ins with Active Arm participants | X | X | X | X | ||

| Encounter Form: (ongoing; completed after each contact with both Active and Ad-Hoc Arm participants) | → | → | → | → | → | → |

Presented in order of administration

Abbreviations: PROMIS, Patient-Reported Measurement Information System, SF, short forms; PFW, Personal Financial Wellness Scale, Neuro-Qol, Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders

FN Intervention

A multidisciplinary research team (e.g., oncology, nursing, psychology, sociology, biostatistics and health service research) with YA cancer survivorship care experience participated in the development of the intervention, guided by the available literature and informed by recommendations elicited from survivor stakeholders.

After completion of the baseline assessment, participants randomized to the active navigation arm will receive a total of four scheduled check-ins with the Tufts-based FN at baseline, 1-, 2-, and 5-months (Figure 2). The assigned FN will follow the participant throughout the study (Table 1). Additionally, the FN will follow-up with the participant and will respond to participant outreach as needed outside of the scheduled check-ins. The goal of these check-ins is to provide personalized financial guidance and support via telephone or audio-video platform. The check-ins will be scheduled for 30 minutes. If the discussion exceeds this time allotment, an additional follow-up call can be scheduled. The content of the interaction will be documented on study team designed encounter forms (i.e., comprehensive checklists covering a wide range of financial issues) stored in the study database. (Appendix D).

A set of materials was created to assist the FN in providing the highest level of support to the participant and to ensure the fidelity of services provided. This set of materials includes time-point specific check-in guides, site-specific contact lists, and problem-solving flow sheets. Five domains are included on each of these documents: work impact, cost of medical care, insurance concerns, material hardship, and pharmacy issues. These materials, which are described in more detail in Appendix D, were developed to reflect the heterogeneity of the sites across the US, because the study team recognizes that issues and potential solutions for one participant at one site might not work for another. Consistent with EID methodology, we worked to find a methodological “middle ground,” so that the intervention could be both expandable and fluid while also adhering to a structured format.

Participants in the ad hoc arm will have the option of contacting the study team at any time. They will be assigned a dedicated FN upon first outreach to discuss their concern(s) and develop a strategy to address each issue. The FN will follow them over the remaining time on the study. Follow-up calls or emails with the ad hoc participants will be based upon their engagement and individualized financial concern(s). Encounter forms will be completed to capture the navigation services provided at each interaction.

Qualitative Interview

Participants, who provided consent to be contacted for this additional research opportunity at study entry, and FN will be invited to be virtually interviewed after completing the 6-month assessment (Table 2). A minimum of 15 interviews will be conducted per study arm or until thematic saturation is reached. A separate interview guide will be used to gain the perspectives of the study FNs. The interviews will be professionally transcribed. All transcripts will be coded and analyzed using a grounded theory approach.

Table 2:

Interview Sample Heterogeneity and Themes

| Sample Heterogeneity | Participant Interview Themes |

|---|---|

| Participant Demographics: site of care; age at initial diagnosis; by race/ethnicity; geography; private insurance vs nonprivate insurance product | Overview of their reason(s) for joining the study; impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on finances and post-treatment cancer care; arm specific questions regarding FN interactions and resources; reflections and recommendations about the study |

| Participant Study Engagement: All assessments completed or not; navigation check-ins all completed or not |

Measuring Outcomes in Effectiveness-Implementations Designs

The RE-AIM model provides a thorough road map with five components to evaluate EID studies: reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance of the intervention over time (Table 3). RE-AIM is a commonly used framework to address the unique challenges of blended EIDs and to provide a structured process to evaluate them [23]. Because EID studies simultaneously test clinical effectiveness and implementation, researchers must measure diverse outcomes. In this study, we use a mixed methods approach to collect quantitative data and qualitative process data to evaluate the RE-AIM components. Experts in EID recommend a mixed methods approach, as historically quantitative data alone has not been sufficient to evaluate all RE-AIM dimensions [39].

Table 3.

RE-AIM Summary of Quantitative and Qualitative Evaluation

| RE-AIM Domain | Definition | Quantitative | Qualitative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reach | Participation rate of the targeted population | How does the study population at each site reflect general population characteristics? What were the participation rates and dropout rates across sites? What were the reasons for screening ineligibility? Among those who were eligible, how many successfully signed consent and proceeded to randomization? Of those who enrolled, what percentage completed the PFW primary outcome measure without the need for further outreach from the study staff? |

Participant Interview: How did you learn about the study? What were your reasons for participating in the study? Did the Covid-19 pandemic influence your decision to participate in the study? Did you face any challenges in enrolling in the study? |

| Effectiveness | The impact of the intervention on important outcomes | Did PFW Scale repeated measures improve for participants in the ad hoc and active arms? Was there a dose effect among participants whereby those who engaged with navigation services with increased frequency and/or increased duration showed subsequent improvement on their PFW scores? |

Participant Interview: What type of guidance and/or referrals did the FN provide? Did these help with your overall financial wellness? Did you address issues with the FN that you were not expecting to talk about? How many of the referrals/resources from the FN did you utilize? |

| Adoption | Institutions ’ uptake of the intervention | Was there a difference in uptake of the intervention between different institutions? Were institutions receptive to internal referrals (referring patients back for services)? |

FN Interview: How well did the intervention assist patients in managing their financial distress while meeting their financial obligations to the institution? |

| Implementation (FN Perspective) | Intervention integrity, quality, and consistency of delivery | Was there a change in the frequency and/or the length of the encounters through the duration of the study between the participants? Was there a change in the frequency and/or the length of the encounters between different FN? Was there a difference in the types or number of referrals made between different FN when addressing similar issues? |

FN Interview: Did FN feel that there were implementation differences between the different sites? Did the FN feel that there was consistency of delivery between the participants? Did the FN feel that the intervention changed over the duration of the study? Did the FN navigator feel that some financial problems were easier to address then others? Was there a perceived difference in providing the intervention based on the FN age and/or experience? |

| Implementation (Participant Perspective) | Intervention integrity, quality, and consistency of delivery | Did participants in the active and ad hoc groups prefer email, phone or video? In the active group how many reminders did it take to successfully schedule the check-ins? What was the rate of rescheduling or failure to complete the scheduled checkin? In the ad hoc group how often did participants reach out to the FN to discuss financial concerns? |

Participant Interview: What were your overall interactions with the FN? Did you feel comfortable talking about financial issues? For those in the active arm: In addition to the four-scheduled check-ins did you also reach out in between the check-ins? Did you like having scheduled meetings or prefer to check in as needed? |

| Maintenance (FN Perspective) | Sustainability of the intervention over time | Were the weekly FN meetings and research staff meetings adequate in helping to maintain the structure and quality of the intervention? If not, did their frequency or structure need to be increased and/or changed during the study? | Study Team Interview: Did the FN feel that their level of training was adequate over time? Did the study team observe drift during the intervention? Where the study meetings effective in identifying drift and maintaining intervention fidelity? Did the FN feel that executing the intervention became easier over time due to gained experience? How did it feel to navigate scheduling, increasing enrollment, and participants at different time-points during the study? |

| Maintenance (Participant Perspective) | Sustainability of the intervention over time | What proportion of the active participants completed the intervention? How were they different from non-completers? What were the completion rates of their scheduled check-ins? Among all participants were the study measures completed, as scheduled, with or without further outreach by the study staff? Of those enrolled in the intervention arms, how many completed check-ins with navigators? How many check-ins were completed? Of those enrolled in the ad hoc arm, how many reached out to the study team? |

Participant Interview: How did you feel about the duration of the study? Did it provide enough time to address your financial concerns? |

Adapted from RE-AIM framework, presented by Ma et al., 2015. [40]

Abbreviations: FN, financial navigation/navigators.

Statistical Analysis and Statistical Power

We will use summary statistics (e.g., means, standard deviations (SD), medians, quartiles, frequencies, percentiles) to describe all study variables. Distributions of continuous variables will be assessed, as well as assumptions of the statistical tests and models (e.g., linearity, normality of residuals). Violations will be addressed using transformations or different statistical tests or models. Missing data will be described, with examination of differences among participants with and without missing data.

Aim 1 will evaluate the effectiveness of the FN intervention by using a repeated measure analysis with the PFW score at 3-and 6-months as outcomes, and adjustment for baseline scores. We will also adjust for variables used in the stratified randomization (site; <18 vs ≥18 years old at diagnosis). Two primary models will be fit to test whether there is a difference between PFW scores for (1) usual care compared to any FN (ad hoc and active) and (2) ad hoc navigation compared to active navigation.

As part of Aim 1, we will explore whether baseline cognitive functioning, emotional support, and general self-efficacy (Table 1) are effect modifiers of the relationship between the navigation arm and PFW. We hypothesize, for example, that patients with lower self-efficacy will have greater baseline distress and may benefit less from the intervention. These modifiers will be categorized/dichotomized based on population mean of 50 (SD=10). For each of the primary models listed above, we fill fit separate repeated measures models for each hypothesized effect modifiers by including an interaction term between the navigation arm and the effect modifier. To assess potential differences in the effectiveness of the intervention based on whether the site already employs a financial navigator (two sites), we will also assess for effect modification in model 2 (ad hoc navigation compared to active navigation) based on this factor.

Aim 2 will describe differences in financial distress (using the PFW) at study baseline by geographic location (urban vs. rural), race/ethnicity, socio-economic status, and age at diagnosis (<18, ≥18 years). We will report mean PFW scores and SD separately by levels of these participant characteristics. To assess for statistically significant differences, we will conduct two-sample t-tests (binary variables) or analysis of variance (ANOVA) (categorical variables).

The quantitative component of Aim 3 will further evaluate the FN intervention using the RE-AIM framework. We will use frequencies, proportions to describe the items listed in Table 3 (e.g. participation, adoption, implementation, maintenance). We will also describe responses to the 3- and 6-month study evaluations.

Power Calculation

This study was powered to support the comparisons made in Aim 1. Our post-randomization sample will be 240 participants with 80 randomized to each arm (active, ad hoc, usual care) in an intent-to-treat analysis. Using this sample size, we calculated an effective sample size of 296, which takes into account correlations in assessments from the same person over time (using an intra-class correlation of 0.5) and assumes 10% dropout at each time (resulting in 1.62 PFW assessments per person on average). To maintain an overall two-sided alpha of 0.05, an alpha of 0.025 will be used to test for the statistical significance of each comparison. Using a two-sample t-test, we will have 96% power to test for an effect size of 0.5 when comparing usual care to any financial navigation; we will have 89% power to detect an effect size of 0.5 when comparing ad hoc navigation to active navigation. An effect size of 0.5, which is consistent with a moderate effect, is supported by prior research using the PFW measure [24].

Discussion

YAs are at increased risk for financial distress, and this vulnerability seems to have only been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic with upheaval in employment, changes in insurance, and health-related risks [41]. This study seeks to understand the financial challenges faced by YA survivors of blood cancer diagnosed in childhood, adolescence or young adulthood, and to provide and explore a feasible and appropriate level of support and assistance to address those challenges. The study team utilized an EID methodology, versus a more traditional RCT, due to the sense of urgency to get a financial assistance intervention out to YAs in the real world with both geographic reach and racial/ethnic diversity. The EID model provides a fluid “middle ground,” without rigidity, so that the FN can address individual concerns, while still providing a structured, stepwise intervention.

YAs tend to be hard to reach, not forthcoming, and reluctant to interface with health care providers until they are in crisis—financial or otherwise [42]. To address these challenges, the study’s remote consenting, assessment, and navigator intervention strategy aims to reach YAs where they are and represents a new era of technological innovation in study design. We expect there will be a lot to learn regarding participants’ engagement and capacity to enroll and complete this fully remote study. Data obtained from navigator-participant interactions will help determine if proactive outreach is more effective than passive participant-initiated outreach, which too often occurs when the patient has already fallen into financial crisis or is lost to follow-up due to overwhelming medical bills and/or the loss of medical insurance coverage. Unanswered in this study is how financial distress varies among non-English speaking YA survivors. Future studies are need to address the linguistic translation and culture adaptation of these key themes in other populations.

Further, YAs historically have been overrepresented among the uninsured or underinsured [43]. Prior to the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 [44], many YAs lost their insurance when they reached the age of maturity and were no longer covered by their parents’ insurance. The ACA addressed some of these barriers, as it offered Dependent Care Expansion to age 26, eliminated pre-existing condition restrictions, and offered affordable insurance products through health exchanges and federal subsidies. However, because implementation of some of the ACA provisions occurred at the state level, [45], there has been variability in health insurance cost and access from state to state. As of 2022, 13 states have a health insurance exchange with more than one product. Apart from any emergency provisions implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020–2022, only 39 states have elected to expand Medicaid. Alongside the expansion of health insurance access, YAs have alarmingly low levels of health insurance literacy [46, 47], which further contributes to their financial distress.

Lay navigators have been successfully incorporated into cancer care at several points along the care continuum. In recent initiatives, navigators have been used to guide cancer patients in issues related to the cost of care. In a four-hospital study of more than 11,000 patients, the inclusion of FN resulted in sizeable reduction both in out-of-pocket expenses for patients and financial losses for the treating institutions [48]. However, the use of FN in similar capacities has not been formally studied among YA survivors.

Conclusion

The study will address many unanswered questions regarding financial navigation within the YA cancer survivor population with implications for future program development including the ability to deliver navigation centrally thereby circumventing barriers or enhancing access to FN embedded within the cancer clinic in a more traditional face-to-face model. Can FN expand their foundational knowledge to address concerns at diverse locations nationwide? Alternatively, what level of site-specific input is needed to tailor services to the local environment? To what extent is an active approach needed with this population, given postulated high levels of distress and low levels of self-efficacy, even though active FN is albeit more labor-intensive and costly. Results of this T2H-EID will inform the most successful strategies to mitigate financial distress among YA cancer survivors and work to address the pressing barriers in this vulnerable population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Ruth Ann Weidner and Megan Catalano to the design and conduct of the study.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. This project was also supported, in part, by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, award number UL1TR002544. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Authors Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests, funding or employment exist, which may inappropriately affect the integrity of this submission.

We have no known conflict of interest or financial disclosures.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05620979

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zebrack B, Isaacson S: Psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol 2012, 30(11):1221–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vetsch J, Wakefield CE, McGill BC, Cohn RJ, Ellis SJ, Stefanic N, Sawyer SM, Zebrack B, Sansom-Daly UM: Educational and vocational goal disruption in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2018, 27(2):532–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warner EL, Kent EE, Trevino KM, Parsons HM, Zebrack BJ, Kirchhoff AC: Social well-being among adolescents and young adults with cancer: A systematic review. Cancer 2016, 122(7):1029–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon LG, Merollini KMD, Lowe A, Chan RJ: A Systematic Review of Financial Toxicity Among Cancer Survivors: We Can’t Pay the Co-Pay. Patient 2017, 10(3):295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, Blough DK, Overstreet KA, Shankaran V, Newcomb P: Financial Insolvency as a Risk Factor for Early Mortality Among Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016, 34(9):980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaul S, Avila JC, Mutambudzi M, Russell H, Kirchhoff AC, Schwartz CL: Mental distress and health care use among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer: A cross-sectional analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. Cancer 2017, 123(5):869–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, Weaver KE, de Moor JS, Rodriguez JL, Rowland JH: Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer 2013, 119(20):3710–3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, Aziz NM: Forgoing medical care because of cost: assessing disparities in healthcare access among cancer survivors living in the United States. Cancer 2010, 116(14):3493–3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, Chino F, Samsa GP, Altomare I, Tulsky J, Ubel P, Schrag D, Nicolla J et al. : Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J Oncol Pract 2014, 10(3):162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, Taylor DH, Goetzinger AM, Zhong X, Abernethy AP: The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. The Oncologist 2013, 18(4):381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Cancer Society: Key Statistics for Childhood Cancers. [https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-in-children/key-statistics.html], 2022. (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 12.American Cancer Society: Special Section: Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults. In: Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. 2020: 29–43. [https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/special-section-cancer-in-adolescents-and-young-adults-2020.pdf], (accessed 5 October 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salsman JM, Bingen K, Barr RD, Freyer DR: Understanding, measuring, and addressing the financial impact of cancer on adolescents and young adults. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2019, 66(7):e27660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landwehr MS, Watson SE, Macpherson CF, Novak KA, Johnson RH: The cost of cancer: a retrospective analysis of the financial impact of cancer on young adults. Cancer Med 2016, 5(5):863–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parsons SK, Kumar AJ: Adolescent and young adult cancer care: Financial hardship and continued uncertainty. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2019, 66(4):e27587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekwueme DU, Zhao J, Rim SH, de Moor JS, Zheng Z, Khushalani JS, Han X, Kent EE, Yabroff KR: Annual Out-of-Pocket Expenditures and Financial Hardship Among Cancer Survivors Aged 18–64 Years - United States, 2011–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019, 68(22):494–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin JT, Bumcrot C, Ulicny T, Lusardi A, Mottola G, Kieffer C, Walsh G: Financial Capabililty in the United States 2016. [https://finrafoundation.org/sites/finrafoundation/files/NFCS-2015-Report-Natl-Findings.pdf], 2016. (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 18.Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G: Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health 2013, 12:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gulliford M, Figueroa-Munoz J, Morgan M, Hughes D, Gibson B, Beech R, Hudson M: What does ‘access to health care’ mean? J Health Serv Res Policy 2002, 7(3):186–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Tracking the COVID-19 Economy’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships. [https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/], 10 February 2022. (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 21.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C: Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012, 50(3):217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cully JA, Armento ME, Mott J, Nadorff MR, Naik AD, Stanley MA, Sorocco KH, Kunik ME, Petersen NJ, Kauth MR: Brief cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care: a hybrid type 2 patient-randomized effectiveness-implementation design. Implementation science : IS 2012, 7:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM: Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 1999, 89(9):1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prawitz ADG, Thomas E; Sorhaindo Benoit; O’Neill Barbara; Kim Jinhee; Patricia Drentea: Incharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale: Development, Administration, and Score Interpretation. Financial Counseling and Planning 2006, 17(1):34–50. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Personal Finance Employee Education Fund (PFEEF): The Personal Financial Wellness Scale. [https://pfeef.org/] (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 26.The President and Fellows of Harvard College: The Reliance System | SMART IRB; [https://smartirb.org/reliance/], 2022. (accessed 5 October 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG: Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009, 42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J et al. : The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019, 95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Twilio Inc. [https://www.twilio.com/], 2022. (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 30.Yeager ND, Hoshaw-Woodard S, Ruymann FB, Termuhlen A: Patterns of care among adolescents with malignancy in Ohio. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2006, 28(1):17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albritton KH, Wiggins CH, Nelson HE, Weeks JC: Site of oncologic specialty care for older adolescents in Utah. J Clin Oncol 2007, 25(29):4616–4621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Medical Association: World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2001, 79(4):373–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Northwestern University: HealthMeasures. [https://www.healthmeasures.net/], 2022. (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 34.Siembida EJ, Reeve BB, Zebrack BJ, Snyder MA, Salsman JM: Measuring health-related quality of life in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors with the National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System((R)) : Comparing adolescent, emerging adult, and young adult survivor perspectives. Psychooncology 2021, 30(3):303–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berkman AM, Murphy KM, Siembida EJ, Lau N, Geng Y, Parsons SK, Salsman JM, Roth ME: Inclusion of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Adolescent and Young Adult Phase III Therapeutic Trials: An Analysis of Cancer Clinical Trials Registered on ClinicalTrials.gov. Value Health 2021, 24(12):1820–1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cella D, Lai JS, Nowinski CJ, Victorson D, Peterman A, Miller D, Bethoux F, Heinemann A, Rubin S, Cavazos JE et al. : Neuro-QOL: brief measures of health-related quality of life for clinical research in neurology. Neurology 2012, 78(23):1860–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ): Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Your Experience with Cancer. [https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/survey_results_saq_ques.jsp?SAQ=Cancer+Experiences+Questionnaire+-+English&Year3=AllYear&Submit2=Search], 2017. (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. [https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2019-BRFSS-Questionnaire-508.pdf], 2019. (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 39.Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, Rabin B, Smith ML, Porter GC, Ory MG, Estabrooks PA: RE-AIM Planning and Evaluation Framework: Adapting to New Science and Practice With a 20-Year Review. Frontiers in public health 2019, 7:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma J, Yank V, Lv N, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Lewis MA, Kramer MK, Snowden MB, Rosas LG, Xiao L, Blonstein AC: Research aimed at improving both mood and weight (RAINBOW) in primary care: A type 1 hybrid design randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2015, 43:260–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGeehan P Utility Bills Piled Up During the Pandemic. Will Shut-offs Follow?: [https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/19/nyregion/ny-utility-bill-moratorium.html], 20 March 2022. (accessed 5 October 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schultz KA, Ness KK, Whitton J, Recklitis C, Zebrack B, Robison LL, Zeltzer L, Mertens AC: Behavioral and social outcomes in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 2007, 25(24):3649–3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parsons HM, Schmidt S, Harlan LC, Kent EE, Lynch CF, Smith AW, Keegan TH, Collaborative AH: Young and uninsured: Insurance patterns of recently diagnosed adolescent and young adult cancer survivors in the AYA HOPE study. Cancer 2014, 120(15):2352–2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Congress.Gov: H.R.3590-Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. [congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/3590], 2010. (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 45.Roberts CJ: National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius. In: 11–393. Edited by States SCotU, vol. 567 U.S. 519. [https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/11pdf/11-393c3a2.pdf] 2012, (accessed 5 October 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tilley L, Yarger J, Brindis CD: Young Adults Changing Insurance Status: Gaps in Health Insurance Literacy. J Community Health 2018, 43(4):680–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong CA, Asch DA, Vinoya CM, Ford CA, Baker T, Town R, Merchant RM: Seeing Health Insurance and HealthCare.gov Through the Eyes of Young Adults. J Adolesc Health 2015, 57(2):137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yezefski T, Steelquist J, Watabayashi K, Sherman D, Shankaran V: Impact of trained oncology financial navigators on patient out-of-pocket spending. Am J Manag Care 2018, 24(5 Suppl):S74–S79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hariton E, Locascio JJ: Randomised controlled trials - the gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: randomised controlled trials. BJOG 2018, 125(13):1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tango Card Inc: Rewards Genius by Tango Card. [https://www.rewardsgenius.com/reward-catalog/], 2022. (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 51.Leukemia & Lymphoma Society: LLS Information Specialists. [https://www.lls.org/support-resources/information-specialists], 2015. (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 52.Triage Cancer: Triage Cancer: Providing free education on the practical and legal issues that arise after a cancer diagnosis. [https://triagecancer.org/], 2022. (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 53.Triage Cancer: Quick Guide to Health Insurance: Employer-Sponsored & Individual Plans. [https://triagecancer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/2022-Health-Insurance-Basics-Employer-Individual-Plans-Quick-Guide.pdf], 2022. (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 54.Gravier E: Here are the best free budgeting tools of 2022. [https://www.cnbc.com/select/best-free-budgeting-tools/], 2021. (accessed 5 October 2022)

- 55.INTUIT: Mint: Managing money, made simple. [https://mint.intuit.com/], (accessed 5 October 2022).

- 56.Cancer and Careers. [https://www.cancerandcareers.org/en], 2022. (accessed 5 October 2022).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.