Abstract

The local microenvironment where tumors develop can shape cancer progression and therapeutic outcome. Emerging evidence demonstrate that the efficacy of immune-checkpoint blockade (ICB) is undermined by fibrotic tumor microenvironment (TME). The majority of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) develops in liver fibrosis, in which the stromal and immune components may form a barricade against immunotherapy. Here, we report that nanodelivery of a programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) trap gene exerts superior efficacy in treating fibrosis-associated HCC when compared with the conventional monoclonal antibody (mAb). In two fibrosis-associated HCC models induced by carbon tetrachloride and a high-fat, high-carbohydrate diet, the PD-L1 trap induced significantly larger tumor regression than mAb with no evidence of toxicity. Mechanistic studies revealed that PD-L1 trap, but not mAb, consistently reduced the M2 macrophage proportion in the fibrotic liver microenvironment and promoted cytotoxic interferon gamma (IFNγ)+tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α)+CD8+T cell infiltration to the tumor. Moreover, PD-L1 trap treatment was associated with decreased tumor-infiltrating polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cell (PMN-MDSC) accumulation, resulting in an inflamed TME with a high cytotoxic CD8+T cell/PMN-MDSC ratio conductive to anti-tumor immune response. Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis of two clinical cohorts demonstrated preferential PD-L1 expression in M2 macrophages in the fibrotic liver, thus supporting the translational potential of nano-PD-L1 trap for fibrotic HCC treatment.

Keywords: HCC, immune-checkpoint blockade, fibrosis, macrophage, nanomedicine

Graphical abstract

This study uncovered the pivotal effect of PD-L1 nano-trap against M2 macrophages in the tumor-surrounding fibrosis, creating a CD8+T cell-inflamed TME for cancer eradication. The predominant PD-L1 expression in M2 macrophages of HCC mouse models and patient cohorts further support the translation of this effective nano-immunotherapy modality for HCC patients.

Introduction

Immunotherapy has transformed the paradigm of cancer treatment, especially for solid malignancies such as melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The monoclonal antibody (mAb) against programmed death 1 (PD-1) or its ligand PD ligand 1 (PD-L1) is the most well-established strategy for immune-checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy. Nonetheless, the efficacy of ICB therapy is dismal in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), exhibiting objective response rates of only 10%–20%.1 Moreover, around 30% of patients with HCC experienced immune-related adverse events in musculoskeletal, dermatologic, and endocrine sites.2 It has also been reported that patients with melanoma or NSCLC with liver metastasis were more resistant to pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1) and displayed shorter progression-free survival.3 Therefore, one of the grand challenges facing cancer immunotherapy is to understand the organ-specific tumor immune contexture.4 Liver is an organ with a unique immune tolerance feature predominantly through induction of macrophages or Kupffer cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), establishing a strong immunosuppressive barrier that may counteract with immunotherapy.5 Both resident and recruited macrophages are the key players in mediating liver homeostasis. In response to environmental signals, the macrophages undergo classical (M1) or alternative (M2) activation to facilitate tumoricidal response or tumor development, respectively.6 In addition, liver macrophages and immunosuppressive myeloid cells are also closely associated with fibrosis, which is a key pathological feature in chronic liver disease and HCC.7,8

Although diverse risk factors contribute to HCC development, liver fibrosis/cirrhosis characterized by matrix deposition and remodeling is a common feature in patients with HCC. With the dissemination of hepatitis B virus vaccine and development of anti-hepatitis C virus drugs, the incidence rate of virus-related HCC has been diminishing. Instead, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has emerged as a major growing cause of HCC in parallel with the diabetes and obesity epidemics.9 NAFLD encompasses a broad spectrum of histopathology ranging from liver steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatic fibrosis.10 Irrespective of the etiologies, around one-third of patients with liver cirrhosis will eventually develop HCC, highlighting the pivotal role of fibrotic liver in HCC development.11

A recent pan-cancer analysis revealed that the effect of ICB therapy relies not only on immune cell activity but also the presence and activity of stromal cells.12 In particular, the fibrotic tumor microenvironment was associated with poorer patient response to immunotherapy in multiple cancers.12 Our recent study has also shown that the fibrotic liver microenvironment promotes tumor immunosuppression and diminishes ICB efficacy in HCC.13 Moreover, disorganization by severe fibrosis or cirrhosis may limit the drug delivery efficiency to liver.14 Therefore, new drug development should be specifically designed to enable effective delivery by sophisticated encapsulation to facilitate preferential accumulation to fibrotic liver for maximal effects. Moreover, the therapeutic agents should overcome the potent liver immunosuppressive microenvironment that limits the efficacy of immunotherapy.

Nanomedicine is therapeutics formulated in carrier materials (such as polymers, lipids, metals, or inorganic materials) with a typical size smaller than 100 nm. Several nanoplatforms, including lipid-coated calcium phosphate (LCP) and lipid-protamine-DNA (LPD) nanoparticles, have been developed for the delivery of therapeutic agents including nucleic acid drugs.15,16 Nanotechnology confers multiple advantages for drug delivery, such as prolonging the circulation time of cargo via protection from degradation and thus increasing the therapeutic effect. It also enables specific targeting to organs or cell types while reducing the side effects. We and others have recently reported nanomedical approaches to target the cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF),17,18 which has been shown to hinder T cell penetration to tumor site and promote tumor progression.19 CAF has been shown to express a high level of sigma receptor and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA).20 By genetic cell-fate mapping, the hepatic stellate cell (HSC), which mediates liver fibrosis and cirrhosis formation, is the precursor of myofibroblasts including CAFs.21 Based on those characteristics, we have further developed a nano-platform that is engineered on the nanoparticle surface with aminoethylanisamide (AEAA), a ligand for sigma receptor, allowing for CAF targeting.22 Given the close relationship between CAF and HSC, as well as the prevalence of liver fibrosis/cirrhosis in patients with HCC, the AEAA-modified nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery system may potentiate the therapeutic effects for patients with HCC.

In this study, we investigated the therapeutic efficacy and mechanistic basis of a versatile LPD nanoparticle loaded with plasmid DNA (pDNA) coding an innovative PD-L1 trap for the treatment of HCC associated with liver fibrosis. Using two fibrosis-associated HCC preclinical models induced by the chemical carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) and a high-fat, high-carbohydrate (HFHC) diet, we showed that the nano-PD-L1 trap exerted potent anti-tumor immune surveillance by remodeling an M2 macrophage-mediated immunosuppressive microenvironment, resulting in a cytotoxic T cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment (TME) that could not be achieved by the conventional anti-PD-L1 mAbs. In concordance with the PD-L1 expression profiles in the mouse models, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis of two clinical cohorts demonstrated preferential PD-L1 expression in M2 macrophages in the fibrotic liver, thus supporting the translational potential of the nano-PD-L1 trap for future clinical application.

Results

Nanoparticle-parceled PD-L1 trap is prone to fibrotic liver delivery

To achieve efficient PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, we applied an LPD nanoparticle encapsulating pDNA encoding the PD-L1 trap, which was composed of a secretive signaling peptide, the extracellular domain of murine PD-1, and the C-terminal trimerization domain of cartilage matrix protein (CMP), followed by affinity tags (Figure 1A). The translation of the PD-L1 trap gene generates a trivalent trap protein that binds to mouse PD-L1 with significantly higher affinity than endogenous PD-1.23,24 The trap gene was encapsulated with ∼90% capture efficiency in LPD nanoparticles, protecting pDNA from enzymatic or hydrolytic degradation. The ligand for sigma receptor, AEAA, was further conjugated at the tip of DSPE-PEG on the surface of LPDs to increase nanoparticle uptake and PD-L1 trap synthesis by HSCs (Figure S1). The LPD nanoparticles thus formed had a hydrodynamic diameter of ∼100 nm and surface charge of ∼40 mV for easy penetration into the organ from circulation (Figures 1B and 1C).23,24 To examine whether the PD-L1 trap can be delivered to the fibrotic liver, we established a liver fibrosis model in C57BL/6 mice by CCl4 induction for 2 months and then administered a single dose of PD-L1 trap/LPD (Figure 1D). The CCl4-treated and age-matched control mice were sacrificed on day 2 post-PD-L1 trap/LPD administration. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Sirius red staining showed architectural distortion and collagen deposition in the liver of CCl4-treated mice (Figure 1E), consistent with α-SMA over-expression possibly by activated HSCs (Figure 1F). As the engineered PD-L1 trap contained a His (6×) tag at the C terminus, we demonstrated preferential production and accumulation of PD-L1 trap in fibrotic liver compared with the normal liver using western blot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analyses (Figures 1F and 1G). ELISA and immunofluorescence (IF) using anti-His antibody showed relatively selective distribution of PD-L1 trap in the fibrotic liver compared with other organs including kidney, lung, heart, and spleen (Figures S2A and S2B). We further consolidated the preferential PD-L1 trap delivery to fibrotic liver of an additional mouse model fed with an HFHC diet for 5 months (Figure 1H),13 which exhibited marked collagen deposition and α-SMA over-expression when compared with the liver of mice fed with a control diet (Figures 1I and 1J). Consistent with the findings in the CCl4-induced fibrosis model, a significant increase in His-tagged PD-L1 trap expression was noted in the HFHC-diet-induced fibrotic livers when compared with the control livers (Figures 1J and 1K) and the other organs (Figure S2C).

Figure 1.

Uptake of LPD nanoparticle-parceled PD-L1 trap by fibrotic liver

(A) Schematic diagram showing the structure of LPD nanoparticle-mediated PD-L1 trap. (B) Size distribution profile of LPD nanoparticle by dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis. (C) Transmission electron microscopic image of the LPD nanoparticle. Scale bar: 100 nm. (D) Experimental schedule for determining the PD-L1 trap uptake in mice with or without liver fibrosis treated by corn oil and CCl4, respectively. (E) Liver morphology, H&E, and Sirius red staining of control normal liver and CCl4-induced fibrotic liver. Scale bar: 100 μm. (F) Western blot analysis of α-SMA and His-tagged PD-L1 trap protein expression in normal liver and fibrotic liver induced by CCl4. (G) ELISA analysis of His-tagged PD-L1 trap protein expression in normal and fibrotic livers. (H) Experimental schedule for determining the PD-L1 trap uptake in mice with or without liver fibrosis induced by control and HFHC diet, respectively. (I) Liver morphology, H&E, and Sirius red staining of control liver and HFHC-diet-induced fibrotic liver. Scale bar: 100 μm. (J) Western blot analysis of α-SMA and His-tagged PD-L1 trap in normal liver or fibrotic liver induced by HFHC diet. (K) ELISA analysis of His-tagged PD-L1 trap protein expression. n ≥ 3. Data were analyzed by unpaired t test and are presented as mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01.

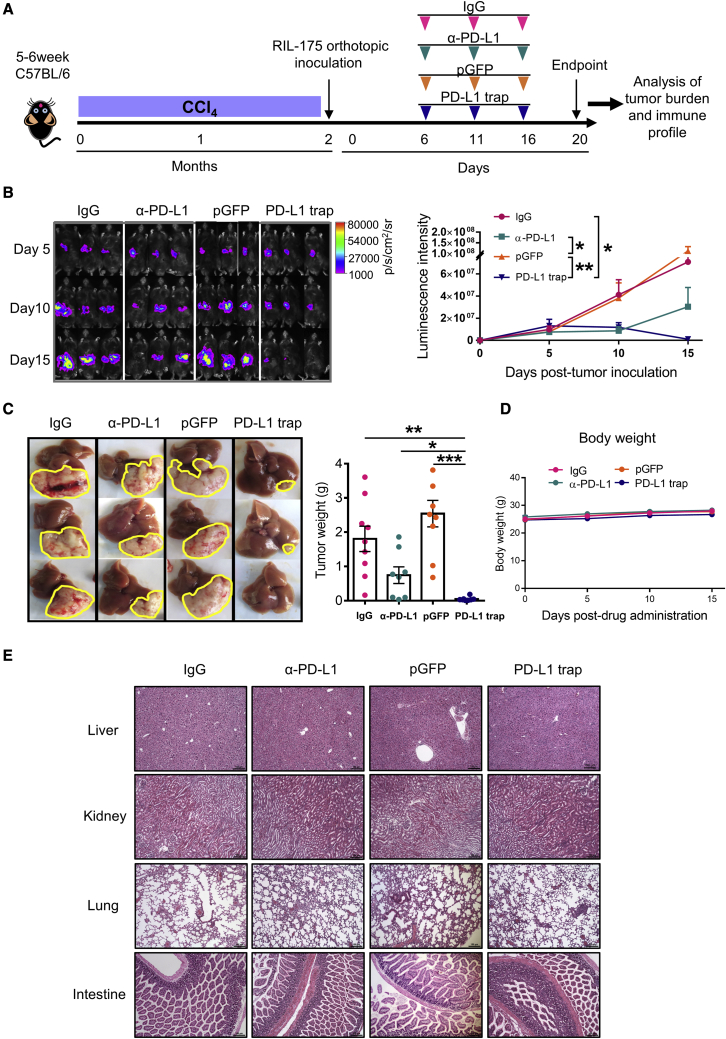

PD-L1 trap shows superior anti-tumor efficacy than conventional anti-PD-L1 mAb in CCl4-induced fibrotic HCC

To determine the therapeutic efficacy of PD-L1 trap, we first established a fibrosis-associated HCC mouse model by CCl4 gavage and followed by intrahepatic tumor inoculation. The tumor-bearing mice were then administered with immunoglublin G (IgG) control, anti-PD-L1 mAb, pGFP, or PD-L1 trap/LPD and monitored by luciferase in vivo imaging (Figure 2A). Anti-PD-L1 mAbs showed a trend to delay tumor growth when compared with the IgG group, but the PD-L1 trap induced significantly larger tumor eradication as indicated by in vivo imaging and endpoint tumor weight (Figures 2B and 2C). Concordant with the strong sigma receptor expression in this HCC model, the PD-L1 trap was markedly expressed and secreted in the fibrotic tumor (Figure S2D). Along with the treatment cycles, the PD-L1 trap did not cause any body weight loss (Figure 2D). Moreover, H&E staining showed no noticeable histological change in the liver, kidney, lung, and intestine (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

PD-L1 trap exhibits superior therapeutic effect in CCl4-induced fibrotic HCC model

(A) Experimental schedule for IgG, anti-PD-L1, pGFP, or PD-L1 trap treatment in CCl4-induced fibrosis-associated HCC mouse model. (B) In vivo imaging and quantification of the luciferase signal expressed by RIL-175 mouse hepatoma cells. (C) Representative images of livers and tumors as well as endpoint tumor weight in individual groups. (D and E) Body weight (D) and histological examination (E) of different organs in different groups (n ≥ 8). Scale bar: 150 μm. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA (C) or two-way ANOVA (B and D) and are presented as mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

PD-L1 trap ameliorates the immunosuppressive liver microenvironment

Liver microenvironment is immune tolerant compared with other organs, posing an obstacle to HCC immunotherapy. We and other have further shown that the fibrotic liver microenvironment contributes to T cell exclusion and limited ICB response.13,25 Since the PD-L1 trap was accumulated in fibrotic liver, we first profiled the liver immune cells to investigate the mechanistic basis of our nanoparticle approach. The myeloid lineages including monocytic (M)-MDSCs, polymorphonuclear (PMN)-MDSCs, and M1/M2 macrophages, as well as CD4+ and CD8+T cells, were determined (Figure S3). Since the PD-L1 trap is designed to block the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, portraying the PD-L1 expression pattern in the immune microenvironment would allow better understanding of the mechanism of action. In the CCl4-induced fibrotic HCC mouse model, macrophages, in particular M2 macrophages, exhibited the highest PD-L1 expression compared with other immune cells or liver cells, implying that M2 macrophages might be a major target for PD-L1 blockade (Figure 3A). While there was no distinction in M- and PMN-MDSC proportions (Figure S4A), M2, but not M1, macrophages were significantly reduced in the PD-L1 trap compared with anti-PD-L1, leading to a marked elevation of the M1/M2 ratio (Figures 3B and S4B). Moreover, CD8+T cells and cytotoxic CD8+T cells tended to be accumulated in the fibrotic liver, resulting in significant higher CD8+T cell/M2 macrophage or cytotoxic CD8+T cell/M2 macrophage ratios in response to PD-L1 trap (Figures 3C and 3D). These data indicate that in contrast to conventional ICB therapy, the PD-L1 trap could mitigate the immunosuppressive liver microenvironment in fibrosis-associated HCC.

Figure 3.

M2 macrophage ablation by PD-L1 trap mitigates the immunosuppressive liver microenvironment

(A) Heatmap of PD-L1 expression in macrophages (M1, M2), MDSCs (PMN-MDC, M-MDSC), T cells (CD4, CD8), and non-immune cells in fibrotic liver microenvironment. (B) Frequencies of total macrophage and M2 macrophage subtype treated by IgG, anti-PD-L1, pGFP, or PD-L1 trap. (C and D) Total CD8 or cytotoxic CD8+T cell proportion and their ratio to M2 macrophage in individual groups. n ≥ 7. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and are presented as mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

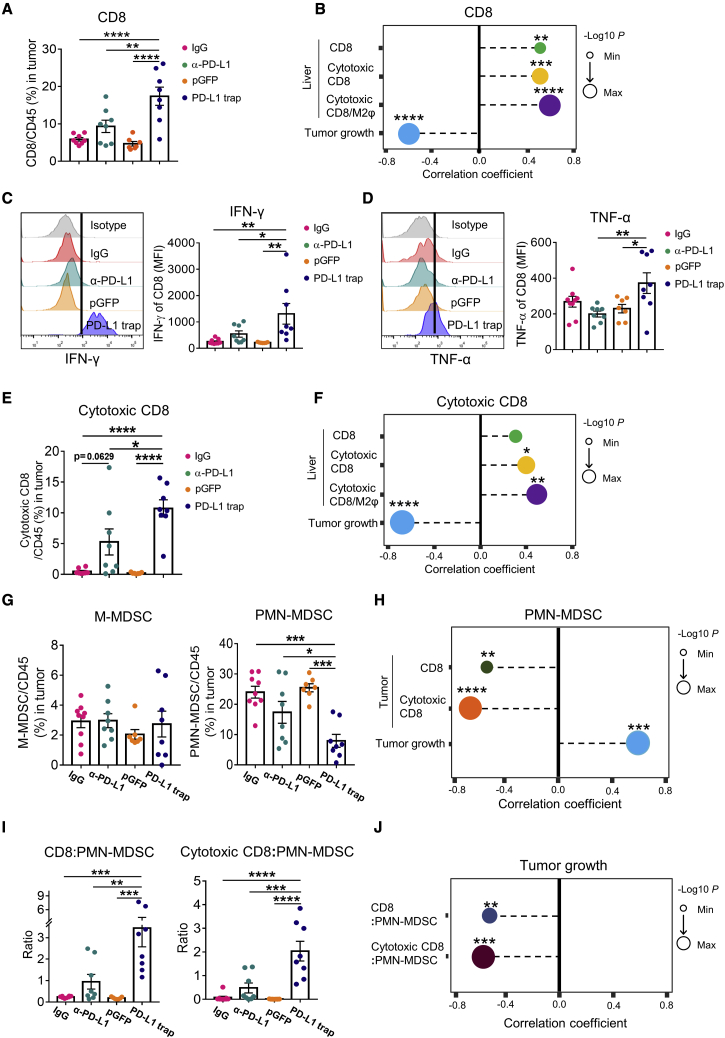

PD-L1 trap confers T cell-inflamed TME and restrains MDSCs in fibrotic HCC

To further decipher the superior anti-tumor efficacy exerted by the PD-L1 trap, we interrogated the immune profiles of TME. In CCl4-induced fibrotic HCC, the PD-L1 trap, but not anti-PD-L1 mAb, markedly boosted CD8+T cell infiltration to the tumor (Figure 4A), which was correlated with tumor regression (Figure 4B). Correlation analysis revealed that high tumor-infiltrating CD8+T cells were associated with increased CD8+T cells, cytotoxic CD8+T cells, and the cytotoxic CD8/M2 macrophage ratio in the liver microenvironment (Figure 4B), implying that modulation of the fibrotic liver milieu by PD-L1 trap could contribute to the T cell-inflamed TME. Furthermore, the cytotoxicity of CD8+T cells as indicated by interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), but not granzyme B, expressions were prominently potentiated by PD-L1 trap compared with the mAb group, leading to a significant increase in cytotoxic CD8+T cells (Figures 4C–4E and S4C). Given their positive correlations with liver CD8+T cells, cytotoxic CD8+T cells, and the cytotoxic CD8/M2 macrophage ratio (Figure 4F), such augmentation of CD8+T cell cytotoxicity might also originate from the change in the fibrotic microenvironment by PD-L1 trap. On the contrary, the proportion of macrophages was not interfered by the PD-L1 trap in the TME (Figure S4D).

Figure 4.

PD-L1 trap promotes cytotoxic CD8+T cell tumor infiltration and represses intra-tumoral PMN-MDSCs in CCl4-induced fibrotic HCC

(A) CD8+T cell percentage in the tumor of CCl4-induced fibrotic HCC treated by IgG, anti-PD-L1, pGFP, or PD-L1 trap. (B) Correlation analysis between intra-tumoral CD8+T cells and liver CD8, liver cytotoxic CD8, liver cytotoxic CD8+T cell/M2 macrophage ratio, or tumor weight. (C and D) IFN-γ and TNF-α expressions in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells for individual groups. (E and F) Frequency of tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic CD8 and its correlation with total CD8, cytotoxic CD8, and cytotoxic CD8+T cell/M2 macrophage ratio in surrounding liver or tumor weight. (G) Proportions of M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCSs in tumor of CCl4-induced fibrotic HCC model with different drug administrations. (H) Correlation between PMN-MDSCs and CD8, cytotoxic CD8+T cell, or tumor weight in fibrotic tumor. (I) Ratios of CD8+T cell/PMN-MDSCs and cytotoxic CD8+T cell/PMN-MDSCs in TME. (J) Tumor weight correlation analysis to the ratio of total CD8+T or cytotoxic CD8+T cell/PMN-MDSCs. n ≥ 7. Data were analyzed by Pearson correlation (B, F, H, and J) or one-way ANOVA and are presented as mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

A recent study demonstrated that activated T cells with up-regulated TRAIL expression by autocrine IFN-α/β could trigger MDSC apoptosis and abolish the immunosuppression on T cells.26 In accordance with this study, we observed a striking reduction of total tumor-infiltrating MDSCs, especially PMN-MDSCs, by PD-L1 trap but not mAb (Figure 4G). Such PMN-MDSC repression was significantly correlated with the enrichment of total and cytotoxic CD8+T cells (Figure 4H). As a whole, PD-L1 trap therapy reverted the immunosuppressive TME into an immune-activated one as shown by higher ratios of total and cytotoxic CD8+T cell/PMN-MDSCs, which were highly correlated with anti-tumor responses (Figures 4I and 4J).

To consolidate the above results, IF staining was performed using the tumor tissues (Figure 5). We found that the level of CD8+ cells was significantly increased, while the PMN-MDSC level, as indicated by CD11b and Ly6G double-positive cells, was reduced by PD-L1 trap but not anti-PD-L1 mAb. These data confirmed that a T cell-inflamed TME was orchestrated by PD-L1 trap for effective tumor eradication.

Figure 5.

Induction of T cell-inflamed TME by PD-L1 trap validated by IF staining in CCl4-induced fibrotic HCC

(A and B) CD8 (A) and CD11b (B) and Ly6G co-immunofluorescence in tumors of CCl4-induced fibrotic HCC. CD8-positive cells, or co-localization of CD11b-positive and Ly6G-positive cells, are shown in the merged images. Hoechst served as positive control for cell nuclei staining. Scale bar: 100 μm. n ≥ 3. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and are presented as mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01.

PD-L1 trap shows superior anti-tumor efficacy than conventional anti-PD-L1 mAb in HFHC-diet-induced fibrotic HCC

Recent clinical data showed that NAFLD blunts the efficacy of ICB therapy in patients with HCC,27,28 which could be recapitulated in our orthotopic HCC model fed by 4–5 months of an HFHC diet (Figures 6A and S5). As reported previously, this conventional ICB-resistant model exhibited liver fibrosis (Figure 6B),13 thus providing a pathophysiologically relevant model to validate the therapeutic efficacy and mechanistic basis of the PD-L1 trap. In contrast to the mAb therapy, we found that the PD-L1 trap markedly dampened the HCC tumorigenicity and prolonged mouse survival of this diet-induced fibrotic HCC model (Figures 6C and 6D). Indeed, half of the treated mice (4/8) showed tumor eradication upon PD-L1 trap treatment, with no obvious change in body weight, organ histology and liver function when compared with the mAb therapy (Figure S6).

Figure 6.

PD-L1 trap exhibits superior therapeutic effect in HFHC-diet-induced fibrotic HCC

(A) Schematic diagram showing the establishment of HFHC-diet-induced fibrotic HCC. (B) Sirius red staining of HFHC-diet-induced fibrotic HCC treated with anti-PD-L1 or PD-L1 trap. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Endpoint tumor weight and tumor incidence of mice treated with anti-PD-L1 or PD-L1 trap treatment (n ≥ 8). (D) Survival analysis of mice treated with anti-PD-L1 or PD-L1 trap (n ≥ 8). (E) Distribution of PD-L1 in fibrotic liver microenvironment. (F) Macrophage and M2 subtype proportion in liver with indicated treatments. (G) Cytotoxic CD8+T cells and the ratio of cytotoxic CD8+T cell/M2 macrophage in liver of different groups. n ≥ 5. (H and I) CD8 (H) or CD11b (I) and Ly6G co-immunofluorescence in tumors of HFHC-diet-induced fibrotic HCC. CD8-positive cells, or co-localization of CD11b-positive and Ly6G-positive cells, are shown in merged images. Hoechst served as positive control for cell nuclei staining. Scale bar: 100 μm. n ≥ 3. Data were analyzed by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test or unpaired t test and are presented as mean ± SE. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01.

Consistent with the CCl4-induced fibrotic HCC model, M2 macrophages in diet-induced liver fibrosis also highly expressed PD-L1 (Figure 6E). Moreover, PD-L1 trap treatment did not affect MDSCs but significantly reduced the abundance of total and M2 macrophages in the liver (Figures 6F and S7). More importantly, there was a marked augmentation of cytotoxic CD8+T cells by PD-L1 trap, resulting in an improved cytotoxic CD8+ T/M2 macrophage ratio (Figure 6G). We further analyzed the tumor immune profile by IF using the residual tissues from this effective therapeutic approach. We verified that the PD-L1 trap, but not anti-PD-L1 mAb, induced CD8+ T cell accumulation and attenuated PMN-MDSCs in the fibrotic TME (Figures 6H and 6I), thus underscoring its superior anti-tumor efficacy.

Predominant M2 macrophage PD-L1 expression in fibrotic liver of patients with HCC

To investigate the clinical relevance of our findings, we utilized published scRNA-seq datasets with paired tumor and adjacent fibrotic liver tissues in treatment-naive patients with primary HCC.29 We acquired 12,001 cells in this cohort of 12 patients with primary HCC after quality control filtering. By performing unsupervised clustering analysis, 22 cell clusters were identified and further annotated into four major cell populations including non-immune cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, and other myeloid cells (Figure 7A). In accordance with the data in our two mouse models, PD-L1 (CD274) expression was mainly expressed by macrophages in the fibrotic liver as well as HCC tumor tissues (Figure 7B). A sub-cluster of the macrophage population expressed the highest PD-L1 expression, which concurred with marker gene expressions of M2 macrophages (Figure 7C). Using an independent cohort of 4 patients with primary HCC with 19,197 single cells,30 we further confirmed the findings of preferential PD-L1 expression in M2 macrophages (Figures 7D–7F).

Figure 7.

PD-L1 expression profile in patients with primary HCC by scRNA-seq analysis

(A) T-SNE plot of all cells from 12 patients with primary HCC with paired adjacent liver and tumor tissues. 22 clusters were further classified into four major populations including non-immune cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, and other myeloid cells. (B) Dot plot showing the average expression and percent expression of CD274 in individual cell population identified with linage markers in both liver and tumor tissues.29 (C) Density plot of CD274 expression in macrophage and M2 macrophage-related signature genes including MRC1, CTSA, CTSC, LYVE1, CCL13, and VEGFB. (D) T-SNE plot of all cells from 4 patients with primary HCC with paired adjacent liver and tumor tissues.30 29 clusters were grouped into four major populations. (E) The dot plot of other linage markers used to identify different cell populations. (F) Density plot of CD274 in macrophage and gene expression related to M2 macrophage as shown in (C).

Discussion

Despite numerous targeted therapies that have been intensively developed for HCC treatment, most of the drugs did not achieve the predefined primary endpoints.31 mAb-mediated ICB therapy showed promise in multiple cancers by augmenting the host immunity. Unfortunately, the clinical outcome with ICB therapy is still unsatisfactory for patients with HCC. Concurred with the multiple functionality and tissue penetration property of nanoparticle-based platform,32,33 our PD-L1 trap/LPD has been engineered to target HSCs in the fibrotic liver. Using two fibrosis-associated HCC preclinical mouse models, we showed that the PD-L1 trap exhibited superior tumor ablation ability compared with the conventional anti-PD-L1 mAb. Mechanistic studies revealed that the PD-L1 trap, but not mAb, consistently reduced the M2 macrophage proportion in the fibrotic liver microenvironment and promoted cytotoxic CD8+T cell infiltration to the tumor. Moreover, PD-L1 trap treatment was associated with decreased tumor-infiltrating PMN-MDSC accumulation, resulting in an inflamed TME with a high cytotoxic CD8+T cell/PMN-MDSC ratio conductive to anti-tumor immune responses.

Understanding the mechanisms of tumor immune evasion provides insights for the inefficiency of current anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy and the rationale for future drug development for patients with HCC. To date, several mechanisms have been proposed for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 resistance, such as high tumor mutation burden, deficiency of antigen presentation, and low PD-L1 expression in tumor cells.34,35,36 It has been believed that PD-L1 expression in tumor cells can serve as a biomarker for predicting the cancer patients’ response and prognosis with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy in some cancer types.37,38 In this study, we found that PD-L1 was predominantly expressed in M2 macrophages in both mouse and human fibrotic livers. Concordantly, a recent clinical study reported that CD68+ macrophages possess much higher PD-L1 expression compared with other immune cells in both tumor and stromal compartments in NSCLC.39 These and other data suggest that tumor cell intrinsic PD-L1 expression may not be accurate to predict anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapeutic response.40,41 Taken together, myeloid-derived PD-L1 expression in both liver and cancer compartments should be considered as a potential biomarker in future ICB trials for patients with HCC.

By dissecting the liver immune profile, we found that the PD-L1 trap can ameliorate the immunosuppressive microenvironment by counteracting M2 macrophages. In addition to PD-L1 expression, M2 macrophages also suppress T cell activity via other molecules including arginase I, interleukin-10, interleukin-13, and transforming growth factor-β,42,43 which may also explain the superior therapeutic efficacy of the nanoparticle-based PD-L1 trap. Indeed, it has been reported that the macrophage is a key cellular mediator regulating the host exposure to nanomaterials and subsequent biodistribution.44 Nanoparticles have also been shown to preferentially accumulate in macrophages with systemic administration.45 Once the host encounters nanoparticles, macrophages identify them as foreign bodies and uptake nanoparticles by endocytosis or phagocytosis.46 However, the impact of nanoparticles on macrophages is still controversial, which may be attributable to the diverse materials used and the complexity of core and surface formulation in nanoparticles. Specifically, in two fibrosis-associated HCCs, we observed M2 macrophage reduction by the PD-L1 trap only in the surrounding liver compartment, presumably due to high sigma receptor expression in the stromal microenvironment for nanoparticle uptake and direct M2 macrophage targeting by the AEAA-conjugated nanoparticles (data not shown).47 Although the functional linkage between PD-L1 blockade and M2 macrophage dysregulation remains obscure, the resultant high cytotoxic CD8+T cell/M2 macrophage ratio in the fibrotic liver milieu may contribute to the T cell-inflamed TME, where PMN-MDSCs were subdued along with the accumulation and activation of CD8+T cells. Besides T cell-suppressive function, PMN-MDSCs have been implicated in tumor angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis through production of matrix metalloproteinase-9, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and vascular endothelial growth factor.48,49,50 Therefore, the restrained PMN-MDSC activities would also be responsible for the PD-L1 trap-induced tumor regression.

Although our data revealed that macrophages were compromised by the nanoparticle-mediated PD-L1 trap, the underlying molecular mechanisms are not fully understood. Since most of the studies focused on the TME, the surrounding liver environment has not been well appreciated. Our data indicate that the liver microenvironment is crucial in affecting the therapeutic response and tumor development. It should be noted that the PD-L1 trap does not contain Fc fragments and could interact with the liver environment in a manner different from that of mAb. However, the interactions and molecular mechanisms among M2 macrophages, PMN-MDSCs, and T cells in response to nanoparticle-mediated immunotherapy require further elucidation.

In conclusion, our study revealed a fibrotic liver-targeted nanoparticle approach for HCC immunotherapy, which exerted effective drug delivery and superior preclinical outcome compared with the conventional mAb-mediated therapy. Mechanistic studies uncovered the pivotal function of the nano-PD-L1 trap against M2 macrophages in the tumor-surrounding liver milieu, creating a CD8+T cell-inflamed and MDSC-deprived TME for cancer eradication. The predominant PD-L1 expression in M2 macrophages of two fibrosis-associated HCC mouse models and patient cohorts further support the translation of our effective treatment modality into the next-generation immunotherapy for patients with HCC.

Materials and methods

Nanoparticle-mediated PD-L1 trap

The nanoparticles encapsulated with pDNA encoding the PD-L1 trap were prepared according to a protocol as we previously reported.51 Specifically, the PD-L1 trap plasmid was constructed by genetically assembling the coding sequence of the extracellular domain of murine PD-1 and a trimerized C-terminal domain of CMP together with a coding sequence of a secretion signaling peptide cloned into a pcDNA3.1-expressing plasmid. The constructed plasmid was then mixed with protamine to formulate the core of the LPD nanoparticle. The preformed liposomes, which comprises DOTAP and cholesterol, were further applied to the polymer core for the generation of the LPD nanoparticle loaded with the PD-L1 trap plasmid. Finally, the PD-L1 trap was conjugated with DSPE-PEG and DSPE-PEG-AEAA and balanced by glucose solution for appropriate osmotic pressure. To demonstrate the effect of AEAA on nanoparticle uptake, rat sigma receptor-expressing HSC-T6 cells seeded in a 24-well plate were treated with nanoparticles with or without AEAA conjugation (0.6 μg DNA/well) for 48 h, followed by flow cytometry analysis of His-tagged PD-L1 trap expression.

Fibrosis-associated HCC mouse models and drug administration

All the animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. For the chemical-induced fibrotic HCC model, 5- to 6-week-old C57BL/6 male immune competent mice were administered with 150 μL CCl4 (20%, dissolved in corn oil) by oral gavage every other day for 2 months. Mice were then inoculated with luciferase-expressing murine hepatoma RIL-175 cells (3 × 105 per mouse) via intrahepatic injection. Tumor growth was monitored by in vivo imaging. For the HFHC-diet-induced fibrotic HCC model, 5- to 6-week-old C57BL/6 male mice were fed with an HFHC diet for 5 months, followed by tumor inoculation of RIL-175 cells (5 × 105 per mouse) as we previously described.13 Mice bearing fibrotic HCC were randomly and intravenously administered with IgG control (LTF-2, 10 mg/kg, Bio X Cell), anti-PD-L1 (10F.9G2, 10 mg/kg, Bio X Cell), pGFP (nanoparticle control, 2 mg plasmid/kg), or PD-L1 trap/LPD (2 mg plasmid/kg), respectively, on days 6, 11, and 16 post-tumor inoculation. Mice were sacrificed on day 21 or 30 post-tumor inoculation for CCl4 or HFHC diet models, respectively.

Western blot

Protein lysates were prepared using RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Bimake) and quantified by using detergent-compatible colorimetric assay kit (Bio-Rad). 20–100 μg of proteins in each sample was separated by 8%–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polycrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and electroblotted onto equilibrated nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in 1× TBST and probed with indicated primary antibodies followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies incubation. The immunoblotting signal intensity was detected with a Chemiluminescence kit (WesternBright ECL, or WesternBright Sirius) and ChemDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

ELISA

Tissue proteins were extracted and subjected to ELISA for measuring His-tag protein expression according to the manufacturer’s instructions (GenScript).

IF staining

Paraffin sections of liver and tumor tissues were dewaxed and received antigen retrieval in citrate buffer. The samples were then subjected to blocking by using BSA or goat serum and stained with primary antibody overnight. Subsequently, the sections were washed and stained with fluorescent secondary antibodies and counter stained with Hoechst. Image acquisition was performed by an Olympus IX83 Inverted Microscope with ZDC, Nikon Ti2-E Inverted Fluorescence Microscope, and Zeiss Axioscan 7 Automated Slide Scanner.

Flow cytometry

Cells were harvested and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies targeting surface markers in the staining buffer for 30 min on ice without light. Then, cells were washed with wash buffer, followed by permeabilization on ice for 20 min (BD Biosciences). After washing, antibodies targeting intracellular markers were applied to cells on ice for 1h. Cells were washed and fixed followed by multicolor flow cytometer analysis (BD Biosciences). The antibodies used for western blot, IF staining, and flow cytometry are listed in the Table S1.

scRNA-seq data analysis

Two single-cell sequencing datasets from 12 patients with primary HCC (study I) and 4 patients with primary HCC (study II) were downloaded from the China National GeneBank (CNGBdb: CNP0000650) and European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA: EGAS00001005194), respectively.29,30 After cell filtering, variable genes were identified with FindVariableFeatures function, and the top 2,000 genes were selected for data scaling and principal-component analysis. Subsequent analyses including dimensional reduction and classification were performed according to the standard pipeline with the default parameters in Seurat v.4.52 Clusters were then annotated with the lineage markers. Density plots were generated by using plot_density function in R package Nebulosa for visualizing specific gene expressions based on kernel density estimation.53

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 7, and data were presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Unpaired or paired t tests were used to analyze data with two groups. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze data with more than two groups’ comparison. Two-way ANOVA was applied to the comparison between multiple groups on a continuous variable. Correlation analysis was calculated by Pearson correlation coefficients. Survival analysis was performed by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund (16170451 to A.S.-l.C. and 07180556 to J.Z.), Collaborative Research Fund (C4045-18W to A.S.-l.C.), General Research Fund (14120621 to A.S.-l.C.), Li Ka Shing Foundation (to A.S.-l.C.), and NIH/NCI (CA151652 to R.L.).

Author contributions

Study concept and design, X.L., J.Z., L.H., R.L., and A.S.-l.C.; material preparation and data collection, X.L., S.C., L.Z., W.T., L.D., Y.W., E.M., M.H., and H.L.; bioinformatics analysis, H.W.; manuscript writing and editing, X.L., J.Z., Z.Y., C.H.J.C., J.J.-y.S., L.H., R.L., and A.S.-l.C.; funding source, J.Z., R.L., and A.S.-l.C.

Declaration of interests

The PD-1 ligand trap has been licensed to OncoTrap, Inc., which was co-founded by R.L.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.09.012.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Llovet J.M., Castet F., Heikenwalder M., Maini M.K., Mazzaferro V., Pinato D.J., Pikarsky E., Zhu A.X., Finn R.S. Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022;19:151–172. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00573-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das S., Johnson D.B. Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2019;7:306. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0805-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tumeh P.C., Hellmann M.D., Hamid O., Tsai K.K., Loo K.L., Gubens M.A., Rosenblum M., Harview C.L., Taube J.M., Handley N., et al. Liver metastasis and treatment outcome with anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody in patients with melanoma and NSCLC. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017;5:417–424. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hegde P.S., Chen D.S. Top 10 challenges in cancer immunotherapy. Immunity. 2020;52:17–35. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiegs G., Lohse A.W. Immune tolerance: what is unique about the liver. J. Autoimmun. 2010;34:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sica A., Invernizzi P., Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization in liver homeostasis and pathology. Hepatology. 2014;59:2034–2042. doi: 10.1002/hep.26754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amini-Nik S., Sadri A.R., Diao L., Belo C., Jeschke M.G. Accumulation of myeloid lineage cells is mapping out liver fibrosis post injury: a targetable lesion using Ketanserin. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018;50:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0118-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen Y.K., Lambrecht J., Ju C., Tacke F. Hepatic macrophages in liver homeostasis and diseases-diversity, plasticity and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2021;18:45–56. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-00558-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang D.Q., El-Serag H.B., Loomba R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021;18:223–238. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00381-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starley B.Q., Calcagno C.J., Harrison S.A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: a weighty connection. Hepatology. 2010;51:1820–1832. doi: 10.1002/hep.23594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Serag H.B. Current concepts hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagaev A., Kotlov N., Nomie K., Svekolkin V., Gafurov A., Isaeva O., Osokin N., Kozlov I., Frenkel F., Gancharova O., et al. Conserved pan-cancer microenvironment subtypes predict response to immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:845–865. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu M., Zhou J.Y., Liu X.Y., Feng Y., Yang W.Q., Wu F., Cheung O.K.W., Sun H., Zeng X., Tang W., et al. Targeting monocyte-intrinsic enhancer reprogramming improves immunotherapy efficacy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2020;69:365–379. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Banuelos J., Siller-Lopez F., Miranda A., Aguilar L.K., Aguilar-Cordova E., Armendariz-Borunda J. Cirrhotic rat livers with extensive fibrosis can be safely transduced with clinical-grade adenoviral vectors. Evidence of cirrhosis reversion. Gene Ther. 2002;9:127–134. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu K., Miao L., Goodwin T.J., Li J., Liu Q., Huang L. Quercetin remodels the tumor microenvironment to improve the permeation, retention, and antitumor effects of nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2017;11:4916–4925. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b01522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chono S., Li S.D., Conwell C.C., Huang L. An efficient and low immunostimulatory nanoparticle formulation for systemic siRNA delivery to the tumor. J. Control Release. 2008;131:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miao L., Liu Q., Lin C.M., Luo C., Wang Y.H., Liu L.N., Yin W., Hu S., Kim W.Y., Huang L. Targeting tumor-associated fibroblasts for therapeutic delivery in desmoplastic tumors. Cancer Res. 2017;77:719–731. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y.S., Elechalawar C.K., Hossen M.N., Francek E.R., Dey A., Wilhelm S., Bhattacharya R., Mukherjee P. Gold nanoparticles inhibit activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts by disrupting communication from tumor and microenvironmental cells. Bioactive Mater. 2021;6:326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desbois M., Udyavar A.R., Ryner L., Kozlowski C., Guan Y., Durrbaum M., Lu S., Fortin J.P., Koeppen H., Ziai J., et al. Integrated digital pathology and transcriptome analysis identifies molecular mediators of T-cell exclusion in ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5583. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19408-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miao L., Newby J.M., Lin C.M., Zhang L., Xu F., Kim W.Y., Forest M.G., Lai S.K., Milowsky M.I., Wobker S.E., Huang L. The binding site barrier elicited by tumor-associated fibroblasts interferes disposition of nanoparticles in stroma-vessel type tumors. ACS Nano. 2016;10:9243–9258. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b02776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mederacke I., Hsu C.C., Troeger J.S., Huebener P., Mu X., Dapito D.H., Pradere J.P., Schwabe R.F. Fate tracing reveals hepatic stellate cells as dominant contributors to liver fibrosis independent of its aetiology. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2823. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu M., Song W., Huang L. Drug delivery systems targeting tumor-associated fibroblasts for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2019;448:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miao L., Li J.J., Liu Q., Feng R., Das M., Lin C.M., Goodwin T.J., Dorosheva O., Liu R., Huang L. Transient and local expression of chemokine and immune checkpoint traps to treat pancreatic cancer. ACS Nano. 2017;11:8690–8706. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b01786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu M., Wang Y., Xu L., An S., Tang Y., Zhou X., Li J., Liu R., Huang L. Relaxin gene delivery mitigates liver metastasis and synergizes with check point therapy. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2993. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10893-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuczek D.E., Larsen A.M.H., Thorseth M.L., Carretta M., Kalvisa A., Siersbaek M.S., Simões A.M.C., Roslind A., Engelholm L.H., Noessner E., et al. Collagen density regulates the activity of tumor-infiltrating T cells. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2019;7:68. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0556-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen J., Sun H.W., Yang Y.Y., Chen H.T., Yu X.J., Wu W.C., Xu Y.T., Jin L.L., Wu X.J., Xu J., Zheng L. Reprogramming immunosuppressive myeloid cells by activated T cells promotes the response to anti-PD-1 therapy in colorectal cancer. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2021;6:4. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00377-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfister D., Nunez N.G., Pinyol R., Govaere O., Pinter M., Szydlowska M., Gupta R., Qiu M., Deczkowska A., Weiner A., et al. NASH limits anti-tumour surveillance in immunotherapy-treated HCC. Nature. 2021;592:450–456. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03362-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lombardi R., Piciotti R., Dongiovanni P., Meroni M., Fargion S., Fracanzani A.L. PD-1/PD-L1 Immuno-mediated therapy in NAFLD: advantages and obstacles in the treatment of advanced disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms23052707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Y., Wu L., Zhong Y., Zhou K., Hou Y., Wang Z., Zhang Z., Xie J., Wang C., Chen D., Huang Y., et al. Single-cell landscape of the ecosystem in early-relapse hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. 2021;184:404–421.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vong J.S.L., Ji L., Heung M.M.S., Cheng S.H., Wong J., Lai P.B.S., Wong V.W., Chan S.L., Chan H.L., Jiang P., et al. Single cell and plasma RNA sequencing for RNA liquid biopsy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Chem. 2021;67:1492–1502. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvab116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang A., Yang X.R., Chung W.Y., Dennison A.R., Zhou J. Targeted therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2020;5:146. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00264-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gelperina S., Kisich K., Iseman M.D., Heifets L. The potential advantages of nanoparticle drug delivery systems in chemotherapy of tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005;172:1487–1490. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200504-613PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patra J.K., Das G., Fraceto L.F., Campos E.V.R., Rodriguez-Torres M.D.P., Acosta-Torres L.S., Diaz-Torres L.A., Grillo R., Swamy M.K., Sharma S., et al. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018;16:71. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0392-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marabelle A., Le D.T., Ascierto P.A., Di Giacomo A.M., De Jesus-Acosta A., Delord J.P., Geva R., Gottfried M., Penel N., Hansen A.R., et al. Efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with noncolorectal high microsatellite instability/mismatch repair-deficient cancer: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38:1–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sade-Feldman M., Jiao Y.J., Chen J.H., Rooney M.S., Barzily-Rokni M., Eliane J.P., Bjorgaard S.L., Hammond M.R., Vitzthum H., Blackmon S.M., et al. Resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy through inactivation of antigen presentation. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1136. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01062-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herbst R.S., Soria J.C., Kowanetz M., Fine G.D., Hamid O., Gordon M.S., Sosman J.A., McDermott D.F., Powderly J.D., Gettinger S.N., et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563–567. doi: 10.1038/nature14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Topalian S.L., Hodi F.S., Brahmer J.R., Gettinger S.N., Smith D.C., McDermott D.F., Powderly J.D., Carvajal R.D., Sosman J.A., Atkins M.B., et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Passiglia F., Bronte G., Bazan V., Natoli C., Rizzo S., Galvano A., Listì A., Cicero G., Rolfo C., Santini D., Russo A. PD-L1 expression as predictive biomarker in patients with NSCLC: a pooled analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:19738–19747. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y.T., Zugazagoitia J., Ahmed F.S., Henick B.S., Gettinger S.N., Herbst R.S., Schalper K.A., Rimm D.L. Immune cell PD-L1 colocalizes with macrophages and is associated with outcome in PD-1 pathway blockade therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26:970–977. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith K.N., Llosa N.J., Cottrell T.R., Siegel N., Fan H., Suri P., Chan H.Y., Guo H., Oke T., Awan A.H., et al. Correction to: persistent mutant oncogene specific T cells in two patients benefitting from anti-PD-1. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2019;7:63. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0547-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ribas A., Hu-Lieskovan S. What does PD-L1 positive or negative mean? J. Exp. Med. 2016;213:2835–2840. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruffell B., Chang-Strachan D., Chan V., Rosenbusch A., Ho C.M.T., Pryer N., Daniel D., Hwang E.S., Rugo H.S., Coussens L.M. Macrophage IL-10 blocks CD8(+) T cell-dependent responses to chemotherapy by suppressing IL-12 expression in intratumoral dendritic cells. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:623–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y., Song Y., Du W., Gong L., Chang H., Zou Z. Tumor-associated macrophages: an accomplice in solid tumor progression. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019;26:78. doi: 10.1186/s12929-019-0568-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gustafson H.H., Holt-Casper D., Grainger D.W., Ghandehari H. Nanoparticle uptake: the phagocyte problem. Nano Today. 2015;10:487–510. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reichel D., Tripathi M., Perez J.M. Biological effects of nanoparticles on macrophage polarization in the tumor microenvironment. Nanotheranostics. 2019;3:66–88. doi: 10.7150/ntno.30052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walkey C.D., Olsen J.B., Guo H., Emili A., Chan W.C. Nanoparticle size and surface chemistry determine serum protein adsorption and macrophage uptake. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2139–2147. doi: 10.1021/ja2084338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou X.F., Liu Y., Hu M.Y., Wang M.L., Liu X.R., Huang L. Relaxin gene delivery modulates macrophages to resolve cancer fibrosis and synergizes with immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Sci. Adv. 2021;7 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb6596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang L., DeBusk L.M., Fukuda K., Fingleton B., Green-Jarvis B., Shyr Y., Matrisian L.M., Carbone D.P., Lin P.C. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boelte K.C., Gordy L.E., Joyce S., Thompson M.A., Yang L., Lin P.C. Rgs2 mediates pro-angiogenic function of myeloid derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment via upregulation of MCP-1. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kujawski M., Kortylewski M., Lee H., Herrmann A., Kay H., Yu H. Stat3 mediates myeloid cell-dependent tumor angiogenesis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3367–3377. doi: 10.1172/JCI35213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song W., Shen L., Wang Y., Liu Q., Goodwin T.J., Li J., Dorosheva O., Liu T., Liu R., Huang L. Synergistic and low adverse effect cancer immunotherapy by immunogenic chemotherapy and locally expressed PD-L1 trap. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2237. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04605-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hao Y., Hao S., Andersen-Nissen E., Mauck W.M., 3rd, Zheng S., Butler A., Lee M.J., Wilk A.J., Darby C., Zager M., et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell. 2021;184:3573–3587.e29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alquicira-Hernandez J., Powell J.E. Nebulosa recovers single-cell gene expression signals by kernel density estimation. Bioinformatics. 2021;37:2485–2487. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.