Structured Abstract

Objective:

To identify the factors associated with days away from home in the year after hospital discharge for major surgery.

Summary Background Data:

Relatively little is known about which older persons are susceptible to spending a disproportionate amount of time in hospitals and other health care facilities after major surgery.

Methods:

From a cohort of 754 community-living persons, aged 70+ years, 394 admissions for major surgery were identified from 289 participants who were discharged from the hospital. Candidate risk factors were assessed every 18 months. Days away from home were calculated as the number of days spent in a health care facility.

Results:

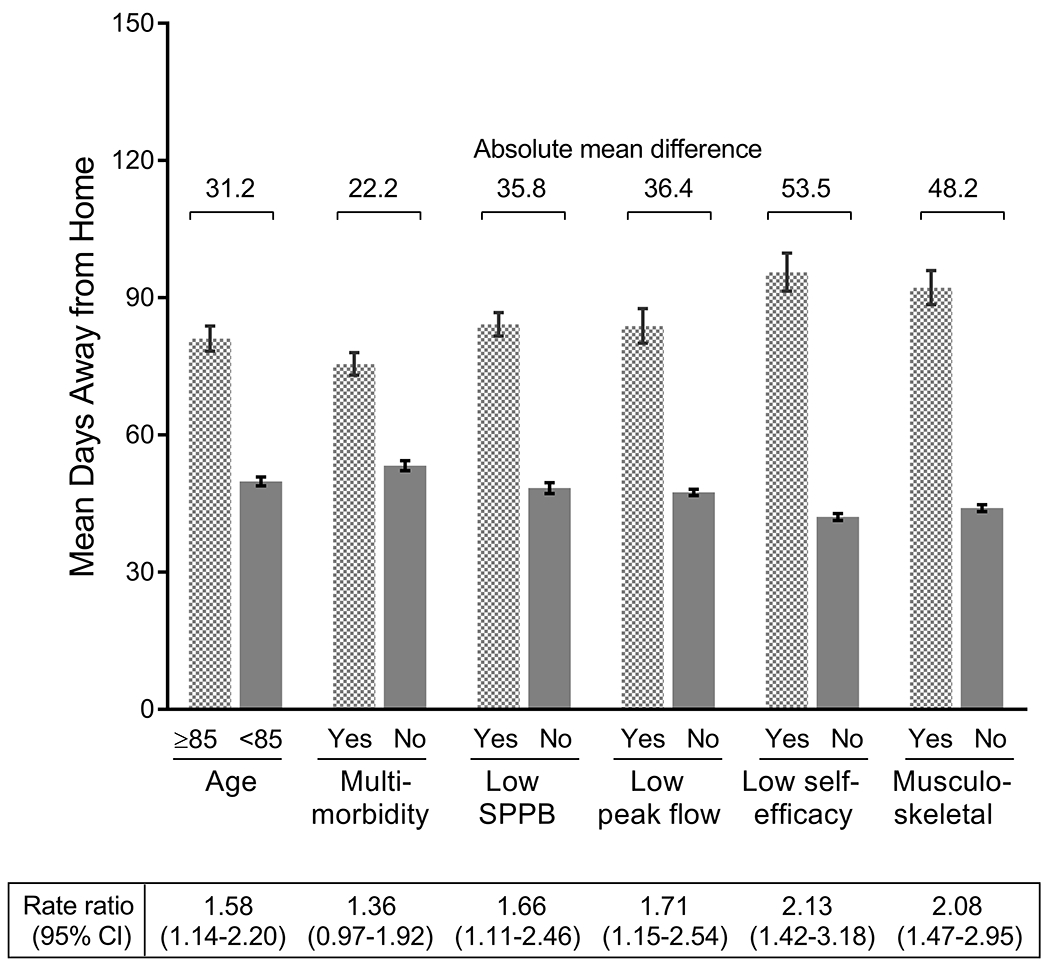

In the year after major surgery, the mean (SD) and median (IQR) number of days away from home were 52.0 (92.2) and 15 (0–51). In multivariable analysis, five factors were independently associated with the number of days away from home: age≥85 years, low score on the Short Physical Performance Battery, low peak expiratory flow, low functional self-efficacy, and musculoskeletal surgery. Based on the presence versus absence of these factors, the absolute mean differences in the number of days away from home ranged from 31.2 for age≥85 years to 53.5 for low functional self-efficacy.

Conclusions:

The five independent risk factors can be used to identify older persons who are particularly susceptible to spending a disproportionate amount of time away from home after major surgery, and a subset of these factors can also serve as targets for interventions to improve quality of life by reducing time spent in hospitals and other health care facilities.

Mini-Abstract

In a prospective longitudinal study of community-living older persons, five factors were independently associated with the number of days away from home in the year after hospital discharge for major surgery: age≥85 years, low score on the Short Physical Performance Battery, low peak flow, low functional self-efficacy, and musculoskeletal surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Major surgery is a common event in the lives of older persons. The 5-year cumulative risk of major surgery in the US is 13.8%, representing nearly 5 million persons 65 years or older.1 With the projected doubling of this population from 46 to 98 million between 2014 and 2060,2 the number of major surgeries among older Americans will increase substantially.

Days spent at home and days away from home have been identified as important patient-centered outcomes,3 especially in older persons who often value quality of life over longevity.4 New models of care, such as Hospital at Home, are being developed and evaluated,5 with the goal of reducing time spent in hospitals and other health care facilities, thereby allowing older persons to spend more time with loved ones in a familiar home environment.

Recently, days away from home has been evaluated as a patient-centered outcome after major surgery.6, 7 While these studies addressed recommendations to incorporate outcomes that matter to older persons into surgical research,8 they focused rather narrowly on high-risk cancer surgery6 and emergency general surgery,7 and neither study evaluated risk factors.

The objective of the current study was to identify the factors associated with days away from home in the year after major surgery in community-living older persons. We used high quality data from a unique longitudinal study that includes a large array of potential risk factors, which were assessed every 18 months for nearly 19 years, along with complete ascertainment of major elective and non-elective surgeries and of days away from home through linkages with Medicare data supplemented by monthly interviews and review of medical records.9 The results of this study should help clinicians to identify older persons who may be particularly susceptible to spending a disproportionate amount of time away from home after major surgery and could inform interventions to improve quality of life by reducing time spent in hospitals and other health care facilities.

METHODS

Study Population

Participants were members of an ongoing longitudinal study of 754 nondisabled community-living persons, 70 years or older.10, 11 Potential participants were members of a large health plan and were excluded for significant cognitive impairment with no available proxy,12 life expectancy less than 12 months, plans to move out of the area, or inability to speak English. Only 4.6% of persons refused screening and 4.0% met one of the aforementioned exclusion criteria, while 75.2% of those eligible agreed to participate and were enrolled from March 1998 to October 1999. The study was approved by the Yale Human Investigation Committee, and all participants provided informed consent. The STROBE Reporting Guidelines were followed.

Data Collection

Comprehensive assessments were completed by trained nurse researchers every 18 months, while telephone interviews were completed monthly through December 2018. For participants who had significant cognitive impairment or were otherwise unavailable, a proxy informant was interviewed using a rigorous protocol.12 Participants were asked to identify their race and ethnicity. These data were collected primarily for descriptive purposes. Deaths were ascertained by review of local obituaries and/or from an informant during a subsequent telephone interview, with a completion rate of 100%. Seven hundred and one (93.0%) participants died after a median of 109 months, while 43 (5.7%) withdrew from the study after a median of 27 months. Data were otherwise available for 94.8% of 4,760 comprehensive assessments and 99.2% of 85,842 monthly interviews. The cohort has been linked to Medicare data.9

Candidate Risk Factors

In addition to demographic characteristics, we considered factors from eight domains. The socioeconomic factors included years of education, living situation, social support,13 Medicaid eligibility,9 and neighborhood disadvantage.14, 15 The health-related factors included multimorbidity16, 17 and frailty.18 The functional factors included disability, which was assessed during the monthly interviews,12 and cognitive impairment.19 The physical capacity factors included the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB)20, 21 and peak expiratory flow, referred to hereafter as peak flow.22 The sensory factors included vision23 and hearing.24 The psychological factors included depressive symptoms25 and functional self-efficacy.26 The behavioral factors included smoking and obesity.27 The surgical factors included elective versus non-elective surgery and musculoskeletal (the most common type) versus non-musculoskeletal surgery, as described below.

To enhance clinical interpretability, values for the candidate risk factors were dichotomized using accepted cut-points.28 Additional operational details are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics Prior to Major Elective and Non-elective Surgery*

| All Surgeries (N=394) | Elective Surgery (N=234) | Non-elective Surgery (N=160) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Characteristic | Measurement Details | n (%) | ||

| Demographic | ||||

| Age ≥ 85 years | 159 (40.4) | 69 (29.5) | 90 (56.3) | |

| Female | 261 (66.2) | 151 (64.5) | 110 (68.8) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | Self identified† | 353 (89.6) | 202 (86.3) | 151 (94.4) |

| Socioeconomic | ||||

| Years of education < 12 | 110 (27.9) | 66 (28.2) | 44 (27.5) | |

| Lives alone | 182 (46.2) | 111 (47.4) | 71 (44.4) | |

| Low social support | Score on MOS ≤ 18‡ | 82 (20.8) | 52 (22.2) | 30 (18.8) |

| Medicaid eligible | Ascertained from Medicare data | 26 (6.6) | 17 (7.3) | 9 (5.6) |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | Highest quintile of ADI | 102 (25.9) | 70 (29.9) | 32 (20.0) |

| Health related | ||||

| Multimorbidity | > 2 chronic conditions§ | 154 (39.1) | 89 (38.0) | 65 (40.6) |

| Frailty | ≥ 3 criteria from Fried phenotype‖ | 131 (33.3) | 60 (25.6) | 71 (44.4) |

| Functional | ||||

| One or more disabilities | From 4 essential activities¶ | 72 (18.3) | 32 (13.7) | 40 (25.0) |

| Cognitive impairment | Score on Folstein MMSE < 24 | 52 (13.2) | 17 (7.3) | 35 (21.9) |

| Physical Capacity# | ||||

| Low SPPB score | <7 | 215 (54.6) | 108 (46.2) | 107 (66.9) |

| Low peak flow, % | < 10 standardized residual percentile | 83 (21.1) | 45 (19.2) | 38 (23.8) |

| Sensory | ||||

| Visual impairment | > 26%, assessed with a Jaeger card | 85 (21.6) | 36 (15.4) | 49 (30.6) |

| Hearing impairment | 4 tones missed out of 4** | 113 (28.7) | 54 (23.1) | 59 (36.9) |

| Psychological | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | Score on CES-D ≥ 20 | 62 (15.7) | 40 (17.1) | 22 (13.8) |

| Low functional self-efficacy | Score ≤ 27†† | 170 (43.2) | 89 (38.0) | 81 (50.6) |

| Behavioral | ||||

| Current or former smoker | 250 (63.5) | 150 (64.1) | 100 (62.5) | |

| Obesity | Body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 89 (22.6) | 57 (24.4) | 32 (20.0) |

| Surgical | ||||

| Musculoskeletal | 156 (39.6) | 76 (32.5) | 80 (50.0) | |

Abbreviations: ADI: Area Deprivation Index; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MOS, Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Characteristics were assessed at the beginning of each 18-month person interval, with the exception of Medicaid eligible and number of disabilities, which were ascertained immediately prior to the hospitalization for major surgery. The 394 observations were contributed by 289 participants.

Participants were asked by a trained nurse researcher to identify their race and ethnicity. These data were collected primarily for descriptive purposes and to fulfill federal regulations regarding the inclusion of minority participants in studies funded by the US National Institutes of Health.

Cut point demarcates the worst quartile, based on the first 356 enrolled participants who had been selected randomly from the source population.

Chronic conditions included hypertension, myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, diabetes mellitus, arthritis, hip fracture, chronic lung disease, and cancer (other than minor skin cancers).

Based on the five standard criteria: weight loss, exhaustion, low physical activity, muscle weakness, and slow walking speed.

Includes bathing, dressing, walking, and transferring.

Cut points denote low physical capacity.

Based on 1000 and 2000 HZ measurements for the left and right ears.

Maximum score is 40, based on level of confidence in performing 10 activities (each scored 0 to 4): dressing, bathing/showering, transferring, going up and down stairs, walking around the neighborhood, house cleaning, preparing simple meals, simple shopping, reaching into cabinets or closets, and hurrying to answer the telephone. Cut point demarcates the worst quartile, based on the first 356 enrolled participants who had been selected randomly from the source population.

Health Care Utilization

During the monthly interviews, information was obtained on hospitalizations and nursing home admissions. Participants were asked whether they had stayed at least overnight in a hospital since the last interview, i.e. during the past month. Dates of hospital admission and discharge were obtained from review of medical records.17 Participants were also asked whether they had been admitted to a nursing home during the past month; if yes, the interviewer noted whether the participant was currently in a nursing home. Based on an independent review of medical records, the accuracy of these reports was high.29

As described in detail elsewhere,17 participant-level data on health care utilization was also obtained through linkages with Medicare claims and nursing home Minimum Data Set (MDS).30, 31 The Medicare claims are divided into files based on billing form and location of care, including hospital (acute care and rehabilitation), nursing home, and hospice facility.32 For periods when participants had managed Medicare, utilization was ascertained using Medicare Provider and Analysis Review (MedPAR) files. Claims for hospice care and MDS were available for all participants regardless of plan type.

Days Away from Home

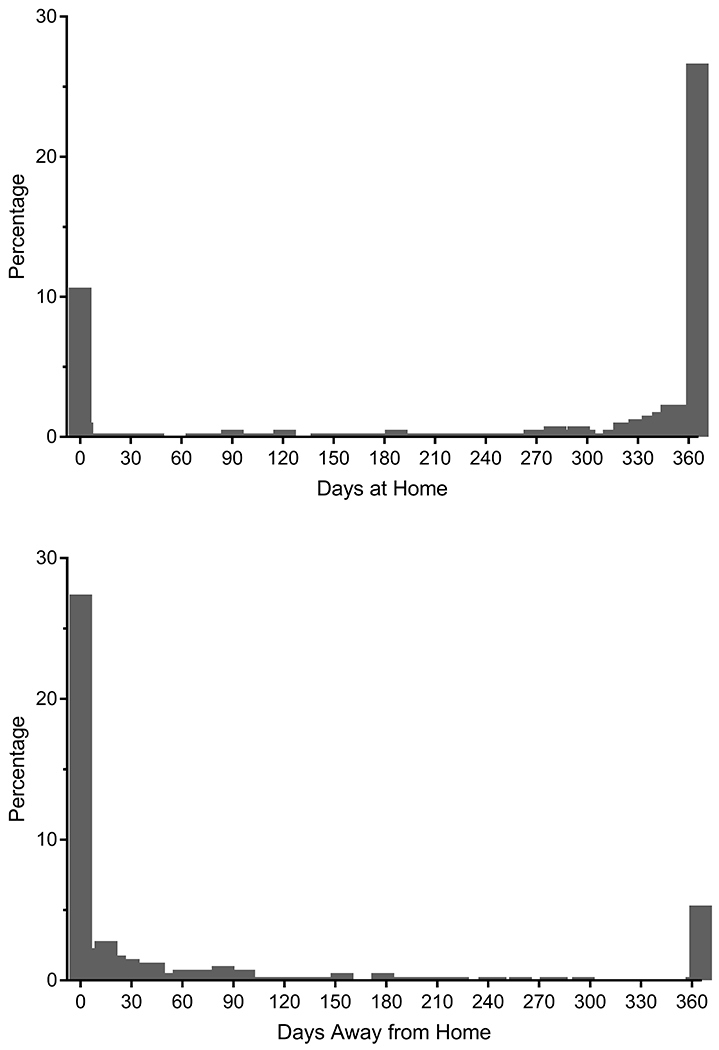

Days away from home were calculated as the number of days spent in a health care facility, including hospital, nursing home and hospice.3, 6 The primary sources for these data were the Medicare claims and MDS. To minimize incomplete data, we also used information from the monthly interviews and review of medical records, especially for periods when participants had managed Medicare (mean penetrance, about 21 per 100 person-months).17 We had considered evaluating days at home as the primary outcome,33 but statistical models could not satisfactorily accommodate the high clustering of data at 365 days (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Days at Home and Days Away from Home in the Year after Hospital Discharge for Major Surgery. The 394 observations were contributed by 289 participants. The percentages are based on the total number of observations. Although both distributions are bimodal, statistical models could not satisfactorily accommodate the high clustering at 365 for days at home. Values for the mean (standard deviation) and median (interquartile range) were 283.8 (124.7) and 346 (281–365) for days at home and 52.0 (92.2) and 15 (0–51) for days away from home. Because of the 56 deaths, the top and bottom panels are not mirror images of one another.

Ascertainment of Major Surgeries

As previously described,34 Medicare files and monthly interview data on self-reported surgeries, verified by chart review, were used to identify participants who had undergone an operation. Major surgery was defined as any procedure in an operating room requiring the use of general anesthesia for a non-percutaneous, non-endoscopic, invasive operation (open or laparoscopic). This is consistent with other definitions of high-risk major surgery in older persons.35 We categorized each major surgery as musculoskeletal, abdominal, vascular, cardiothoracic, neurologic, or other.34 Major surgeries identified from Medicare files were categorized as elective or non-elective by an indicator variable; non-elective surgeries included both urgent and emergent operations.36 Major surgeries identified by self-report and chart review were categorized as elective or non-elective based on the history in the chart; any admission for major surgery originating from the emergency department was categorized as non-elective, as were unscheduled operations due to a time-sensitive condition. For each admission, length of hospital stay was determined.

Assembly of analytic samples

Major surgeries were included through December 2017. Participants could contribute more than one major surgery to the analysis based on the following criteria: (1) observation represented the first major surgery within an 18-month interval; (2) participant was not admitted from a nursing home; (3) participant did not die during the index hospital admission; (4) participant was not discharged to hospice care; and (5) participant did not contribute a major surgery within the prior 12 months. Of the 548 major surgeries, 154 were excluded—82 did not represent the first major surgery within an 18-month interval, 43 were admitted from a nursing home, 11 died in the hospital, 4 were discharged to hospice, and 14 had overlapping follow-up intervals with a prior observation, leaving 394 major surgeries (from 289 participants), including 304 (77.2%) from Medicare claims and 90 (22.8%) from self-report and chart review.

Statistical Analysis

The primary analyses included all major surgeries, although descriptive results are also provided separately for elective and non-elective surgeries. Data on the candidate risk factors were obtained from the comprehensive assessment that preceded the major surgery except for age, Medicaid eligibility, and disability, which were assessed at the time of the monthly interview immediately prior to the major surgery.

No single probability distribution fit the days-away-from-home outcome perfectly. After testing potential alternatives, including the Poisson, negative binomial, and zero-inflated Poisson, we chose the zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) for two reasons. First, zero was the most common outcome value, the circumstance for which the ZINB was developed; and second, the ZINB had the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) score. Due to the varying duration of follow-up among decedents, all models accounted for the number of days of follow-up. Bivariate associations were evaluated between each of the candidate risk factors and days away from home. Rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated to quantify the strength and precision of these associations. The rate ratios denote the relative increase (or decrease) in days away from home for each risk factor.

As in prior studies,37, 38 the multivariable models included length of hospital admission, number of months to major surgery from start of the 18-month interval, and number of the specific 18-month interval (to account for calendar time). Because the ZINB does not include adjustment of standard errors for multiple observations, the bivariate and multivariable models also included the number of observations per participant to account for potential within-participant correlation. For the factors evaluated in the bivariate analyses, a backward selection approach was used with a retention criterion of P< 0.10. To determine whether the inability to fully account for within-participant correlation might have influenced our multivariable results, we performed two sets of sensitivity analyses. First, we fit the negative binomial distribution with and without generalized estimating equations (GEE). The goal was to determine whether the CIs changed substantively when GEE was not used to account for within-participant correlation. Second, we reran the final ZINB model on the subset of first observations per participant. The goal was to determine whether the point estimates differed from those of the primary analysis that included more than one observation per participant.

To enhance clinical interpretation, we calculated the least square means for the number of days away from home per unit of time based on the presence and absence of factors that were retained in the final multivariable model. Based on these estimates, the absolute mean difference in the number of days away from home per 1-year of follow-up was calculated for each risk factor. Finally, because the modal value for the number of days away from home was 0, we ran a multivariable logistic regression model with 1 or more days away from home as the outcome to confirm that our results were not dependent on the choice of a specific modeling approach.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, NC). Statistical significance was defined as a 2-tailed P < .05.

RESULTS

The participant characteristics for the 394 major surgeries are provided in Table 1. Overall, about 40% were 85 years or older, two-thirds were female, and nearly 90% were Non-Hispanic White. Participants who had elective surgery generally had a more favorable risk factor profile than those who had non-elective surgery, as evidenced by their younger age and lower prevalence of frailty, disability, impairments in cognition, physical capacity, vision and hearing, and low functional self-efficacy. However, participants who had elective surgery were more likely to be Black or Hispanic and to live in a disadvantaged neighborhood. The surgical characteristics are provided in Table 2. The three most common types of surgery, which differed considerably between elective and non-elective procedures, were musculoskeletal, vascular and abdominal. Hospital admissions were more than twice as long for non-elective versus elective surgeries. A complete list of operations is provided in Supplemental Table S1.

Table 2.

Surgical Characteristics According to Major Elective and Non-elective Surgery

| Characteristic | All Surgeries (N=394) | Elective Surgery (N=234) | Non-elective Surgery (N=160) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Surgery, n (%) | |||

| Musculoskeletal | 156 (39.6) | 76 (32.5) | 80 (50.0) |

| Vascular | 65 (16.5) | 48 (20.5) | 17 (10.6) |

| Abdominal | 64 (16.2) | 27 (11.5) | 37 (23.1) |

| Cardiothoracic | 29 (7.4) | 18 (7.7) | 11 (6.9) |

| Neurologic | 20 (5.1) | 15 (6.4) | 5 (3.1) |

| Other* | 60 (15.2) | 50 (21.4) | 10 (6.3) |

| Length of hospital admission (days), mean (SD) | 6.0 ± 7.1 | 3.9 ± 3.1 | 9.1 ± 9.8 |

Included thyroidectomies, major breast operations, extensive lymph node excisions, burn debridements, and skin grafts.

As shown in Figure 1, the distributions of days at home and away from home were bimodal and highly skewed, to the right for the former and to the left for the latter. For days away from home, the distributions were comparable for elective and non-elective surgeries, as shown in Supplemental Figure 1; however, the percentage with 0 days was larger for elective surgery, while the percentage with greater than 360 days was larger for non-elective surgery. Overall, the majority of days away from home were spent in a nursing home (87.5%), followed by hospital (11.9%) and hospice (0.6%). Over the 12 months of follow-up, there were 56 (14.2%) deaths at a median (interquartile range) of 150 (57–220) days. The bivariate associations between the candidate risk factors and days away from home are provided in Table 3. Statistically significant associations were observed for many of the factors, with rate ratios ranging from 1.57 for age ≥ 85 years to 2.80 for low SPPB score. These values indicate that the numbers of days away from home were 57% and 280% larger when these factors were present versus absent.

Table 3.

Bivariate Associations Between Candidate Risk Factors and Days Away From Home in the Year after Major Surgery (N=394)*

| Characteristic | Rate Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||

| Age ≥ 85 years | 1.57 (1.10, 2.26) | 0.014 |

| Female | 1.36 (0.92, 1.98) | 0.109 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.88 (0.46, 1.54) | 0.678 |

| Socioeconomic | ||

| Years of education ≤ 12 | 1.26 (0.86, 1.89) | 0.252 |

| Lives alone | 1.25 (0.87, 1.78) | 0.225 |

| Low social support | 0.82 (0.54, 1.30) | 0.382 |

| Medicaid eligible | 1.63 (0.86, 3.55) | 0.173 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | 1.33 (0.90, 2.03) | 0.166 |

| Health related | ||

| Multimorbidity | 1.23 (0.86, 1.78) | 0.262 |

| Frailty | 2.38 (1.67, 3.44) | < 0.001 |

| Functional | ||

| One or more disabilities | 2.16 (1.42, 3.42) | < 0.001 |

| Cognitive impairment | 1.60 (0.99, 2.74) | 0.066 |

| Physical Capacity | ||

| Low SPPB score | 2.80 (1.96, 3.98) | < 0.001 |

| Low peak flow | 1.75 (1.17, 2.73) | 0.009 |

| Sensory | ||

| Visual impairment | 1.65 (1.10, 2.56) | 0.019 |

| Hearing impairment | 1.32 (0.91, 1.97) | 0.153 |

| Psychological | ||

| Depressive symptoms | 1.61 (1.03, 2.66) | 0.048 |

| Low functional self-efficacy | 2.57 (1.82, 3.66) | < 0.001 |

| Behavioral | ||

| Current or former smoker | 1.17 (0.80, 1.69) | 0.400 |

| Obesity | 0.85 (0.57, 1.30) | 0.430 |

| Surgical | ||

| Non-elective | 2.29 (1.62, 3.27) | < 0.001 |

| Musculoskeletal | 1.59 (1.11, 2.29) | 0.011 |

The 394 observations were contributed by 289 participants. To account for the varying duration of follow-up among decedents, the models included the number of days of follow-up.

Figure 2 provides the rate ratios and mean number of days away from home based on the presence and absence of the risk factors identified from the multivariable model. Rate ratios for the statistically significant factors ranged from 1.58 for age ≥ 85 years to 2.13 for low functional self-efficacy. The corresponding values for the absolute mean differences based on the presence versus absence of these factors ranged from 31.2 days for age ≥ 85 years to 53.5 days for low functional self-efficacy. These values indicate that participants who were 85 years or older and those with low self-efficacy spent about a month and nearly two months longer away from home, on average, than those without these risk factors. The other factors that were independently associated with days away from home included low SPPB score, low peak flow and musculoskeletal surgery. As shown in Table 4, the confidence intervals for the rate ratios from the negative binomial models with and without GEE were very similar (first sensitivity analysis), while the point estimates for the final zero-inflated negative binomial model that included only the first observation for each participant did not differ significantly from those in Figure 2 (second sensitivity analysis). When the outcome was dichotomized as 1 or more days away from home, strong and independent associations were observed for each of the risk factors other than low peak flow, with adjusted odds ratios ranging from 1.87 for multimorbidity to 5.82 for musculoskeletal surgery, as shown in Table 5.

Figure 2.

Rate Ratios and Least Square Means for the Number of Days Away from Home for the Final Set of Risk Factors. The factors were identified from a multivariable model that used a backward, step-down selection procedure with p-value < .10, as described in the Methods. The multivariable model was adjusted for the number of days of follow-up, length of hospital admission, number of months to major surgery from start of the 18-month interval, number of the specific 18-month interval, and number of observations per participant. For each set of values, the rate ratio and 95% confidence intervals are provided below, and the absolute mean difference in the number of days away from home per 1-year of follow-up is provided above. The bars represent standard errors.

Table 4.

Sensitivity Analyses for Multivariable Associations Between Risk Factors and Days Away From Home in the Year after Major Surgery

| Rate Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| First Sensitivity Analysis† | Second | ||

| Risk Factors* | With GEE | Without GEE | Sensitivity Analysis‡ |

| Age ≥ 85 years | 1.76 (1.23, 2.53) | 1.76 (1.24, 2.51) | 1.44 (0.95, 2.20) |

| Multimorbidity | 1.52 (1.07, 2.17) | 1.50 (1.04, 2.19) | 1.48 (0.97, 2.30) |

| Low SPPB score | 1.74 (1.09, 2.77) | 1.74 (1.14, 2.64) | 1.58 (0.99, 2.54) |

| Low peak flow | 1.74 (1.20, 2.52) | 1.76 (1.15, 2.76) | 1.40 (0.84, 2.41) |

| Low functional self-efficacy | 2.29 (1.46, 3.60) | 2.27 (1.47, 3.50) | 2.23 (1.37, 3.62) |

| Musculoskeletal | 2.54 (1.69, 3.82) | 2.53 (1.75, 3.70) | 2.62 (1.72, 4.01) |

Abbreviation: GEE, generalized estimating equations; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Identified from the final zero-inflated negative binomial model that included all 394 observations.

Results from negative binomial models that included all 394 observations.

Results from final zero-inflated negative binomial model that included only the first observation for each of the 289 participants.

Table 5.

Multivariable Associations Between Risk Factors and One or More Days Away From Home in the Year after Major Surgery

| Risk Factors* | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)† |

|---|---|

| Age ≥ 85 years | 1.93 (1.10, 3.40) |

| Multimorbidity | 1.87 (1.06, 3.31) |

| Low SPPB score | 2.13 (1.18, 3.84) |

| Low peak flow | 1.28 (0.64, 2.57) |

| Low functional self-efficacy | 2.29 (1.20, 4.37) |

| Musculoskeletal | 5.82 (3.07, 11.1) |

Abbreviation: SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Identified from the final zero-inflated negative binomial model that included all 394 observations.

Results from a multivariable logistic regression model that included all 394 observations.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective longitudinal study of community-living older persons, we identified five factors that were independently associated with the number of days away from home in the year after hospital discharge for major surgery. Each of these factors, including age 85 years or older, low SPPB score, low peak flow, low functional self-efficacy, and musculoskeletal surgery, can be used to identify older persons who are particularly susceptible to spending a disproportionate amount of time away from home. Because three of these factors—low SPPB score, low peak flow and low functional self-efficacy—are potentially modifiable, they can also serve as targets for interventions to improve quality of life after major surgery by reducing time spent in hospitals and other health care facilities.

The differences in the number of days away from home between persons with and without each of the five independent risk factors were substantial, ranging from 31 to 54 days during the 1-year follow-up period. In a recently published study,39 a difference of only 19 days was found to be clinically meaningful. Four of the factors identified in the current study—age, peak flow, functional self-efficacy, and type of surgery—can be easily assessed. While the SPPB can take up to ten minutes to complete,40 gait speed, one of its three components, can be assessed quickly and accounts for up to 96% of its predictive accuracy for functional outcomes.20

To optimize time at home after major surgery, a highly-valued patient-centered outcome,41 at-risk older persons could be referred to innovative programs, such as the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE).42 Although not yet studied for post-acute care,43 another alternative would be the Community Aging in Place—Advancing Better Living for Elders (CAPABLE) program, which provides tailored action plans based on coordinated assessments by an occupational therapist and registered nurse, with the goal of promoting functional independence among vulnerable older persons.44 Our findings also suggest that time spent at home after major surgery could potentially be increased through interventions that improve functional self-efficacy and measures of physical capacity, such as the SPPB, since improvements in these intermediate outcomes have been shown to mediate improvements in more distal outcomes.45–47 Furthermore, peak flow, a strong predictor of subsequent disability,22 may improve through reconditioning, smoking cessation and more aggressive management of underlying lung disease.48 Nonetheless, personal preferences should be considered when making arrangements for post-surgical care since some older patients, particularly those who live alone or have special medical needs, may value time recovering at a rehabilitation facility.49

We found that non-elective surgery was significantly associated with days away from home in bivariate but not multivariable analyses. This is likely due to large differences in several of the independent risk factors between non-elective and elective surgeries, with the former group having a much higher prevalence of advanced age, low SPPB score, low functional self-efficacy, and musculoskeletal surgery.

A unique feature of the current study is the assembly of a large sample of major elective and nonelective surgeries from an ongoing longitudinal study, thereby reducing sampling bias50 and permitting assessment of a comprehensive set of premorbid factors. Additional strengths include reassessment of the candidate risk factors at 18-month intervals and complete ascertainment of a diverse mix of major surgeries using a standard definition35 and several different sources of information, including Medicare files, self-report, and medical records. These complementary sources of information also permitted us to optimize ascertainment of days spent in a health care facility.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. First, detailed information was not available on the hospitalizations for major surgery, including acuity of illness, surgical complexity, and postoperative complications. To partially address this issue, the multivariable models included length of hospital admission. Second, we focused primarily although not exclusively on patient-related factors since they can be more easily assessed and used to identify at-risk patients and are generally more readily amenable to potential interventions than provider-related factors such as surgeon quality ratings. Third, because this was an observational study, the reported associations cannot be construed as causal. Even if the associations were causal, whether days away from home can be reduced through currently available interventions is uncertain. Fourth, the highly skewed distribution of data did not permit us to evaluate days at home as the primary outcome or to fully account for within-participant correlation. At least two recent studies have evaluated days away from home rather than days at home as the primary outcome after major surgery.6, 7 In addition, two sets of sensitivity analyses indicated that our multivariable results were not substantively influenced by the inability to fully account for within-participant correlation. The results of a multivariable logistic regression analysis with one or more days away from home as the outcome were generally consistent with those of our primary and sensitivity analyses. Finally, because participants were members of a single health plan in South Central Connecticut, our findings may not be generalizable to older persons in other settings. Generalizability, however, depends not only on the choice of the study sample but also on the stability of the sample over time.51 One of the great strengths of our study is the low attrition rate. The generalizability of our findings is also enhanced by our high participation rate, which was greater than 75%.

In summary, among community-living older persons, age 85 years or older, low SPPB score, low peak flow, low functional self-efficacy, and musculoskeletal surgery are independently associated with days away from home in the year after major surgery. These factors can be used to identify older persons who are particularly susceptible to spending a disproportionate amount of time away from home after major surgery, and a subset of these factors can also serve as targets for interventions to improve quality of life after major surgery by reducing time spent in hospitals and other health care facilities.

Supplementary Material

On-line Supplemental Table S1: Complete List of 394 Operations Included in the Analysis by Operation Type

On-line Supplemental Figure 1. Distribution of Days Away from Home in the Year after Hospital Discharge for Major Elective and Non-Elective Surgery. The percentages are based on the total number of observations for each group.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Denise Shepard, BSN, MBA, Andrea Benjamin, BSN, Barbara Foster, and Amy Shelton, MPH, for assistance with data collection; Wanda Carr and Geraldine Hawthorne, BS, for assistance with data entry and management; Peter Charpentier, MPH, for design and development of the study database and participant tracking system; and Joanne McGloin, MDiv, MBA, for leadership and advice as the Project Director. Each of these persons were paid employees of Yale School of Medicine during the conduct of this study.

The work for this report was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (R01AG017560). The study was conducted at the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG21342).

REFERENCES

- 1.Becher RD, Vander Wyk B, Leo-Summers L, et al. The incidence and cumulative risk of major surgery in older persons in the United States. Ann Surg 2021; 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mather M, Jacobsen LA, Pollard KM. Aging in the United States. Popul Bull 2015; 70:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groff AC, Colla CH, Lee TH. Days spent at home - A patient-centered goal and outcome. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:1610–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L, et al. Health outcome prioritization as a tool for decision making among older persons with multiple chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1854–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Federman AD, Soones T, DeCherrie LV, et al. Association of a bundled hospital-at-home and 30-day postacute transitional care program with clinical outcomes and patient experiences. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178:1033–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suskind AM, Zhao S, Boscardin WJ, et al. Time spent away from home in the year following high-risk cancer surgery in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020; 68:505–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee KC, Sturgeon D, Lipsitz S, et al. Mortality and health care utilization among Medicare patients undergoing emergency general surgery vs those with acute medical conditions. JAMA Surg 2020; 155:216–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung C, Meissner MA, Garg T. Incorporating outcomes that matter to older adults into surgical research. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021; 69:618–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill TM, Han L, Gahbauer EA, et al. Cohort Profile: The Precipitating Events Project (PEP Study). J Nutr Health Aging 2020; 24:438–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill TM, Desai MM, Gahbauer EA, et al. Restricted activity among community-living older persons: incidence, precipitants, and health care utilization. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135:313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardy SE, Gill TM. Recovery from disability among community-dwelling older persons. J Am Med Assoc 2004; 291:1596–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill TM, Hardy SE, Williams CS. Underestimation of disability among community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50:1492–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardy SE, Gill TM. Factors associated with recovery of independence among newly disabled older persons. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kind AJH, Buckingham WR. Making neighborhood-disadvantage metrics accessible - the Neighborhood Atlas. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:2456–2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill TM, Zang EX, Murphy TE, et al. Association between neighborhood disadvantage and functional well-being in community-living older persons. JAMA Intern Med 2021; 181:1297–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60:E1–E25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill TM. Disentangling the disabling process: insights from the Precipitating Events Project. Gerontologist 2014; 54:533–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG, et al. Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol Med Sci 2000; 55A:M221–M231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gill TM, Murphy TE, Barry LC, et al. Risk factors for disability subtypes in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57:1850–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaz Fragoso CA, Gahbauer EA, Van Ness PH, et al. Peak expiratory flow as a predictor of subsequent disability and death in community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56:1014–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spaeth EB, Fralick FB, Hughes WF. Estimates of loss of visual efficiency. Arch Ophthalmol 1955; 54:462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lichtenstein MJ, Bess FH, Logan SA. Validation of screening tools for identifying hearing-impaired elderly in primary care. J Am Med Assoc 1988; 259:2875–2878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, et al. Two shorter forms of the CES-D Depression Symptoms Index. J Aging Health 1993; 5:179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reid MC, Williams CS, Gill TM. The relationship between psychological factors and disabling musculoskeletal pain in community-dwelling older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51:1092–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gill TM, Allore HG, Han L. Bathing disability and the risk of long-term admission to a nursing home. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006; 61:821–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gill TM, Han L, Gahbauer EA, et al. Risk factors and precipitants of severe disability among community-living older persons. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3:e206021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gill TM, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, et al. Association of injurious falls with disability outcomes and nursing home admissions in community-living older persons. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 178:418–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolinsky FD, Miller TR, An H, et al. Hospital episodes and physician visits: the concordance between self-reports and Medicare claims. Med Care 2007; 45:300–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Intrator O, Hiris J, Berg K, et al. The residential history file: studying nursing home residents’ long-term care histories. Health Serv Res 2011; 46:120–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Research Identifiable File Availability. Available at: https://www.resdac.org/file-availability. Accessed Assessed October 24, 2018.

- 33.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Leo-Summers L, et al. Days spent at home in the last six months of life among community-living older persons. Am J Med 2019; 132:234–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stabenau HF, Becher RD, Gahbauer EA, et al. Functional trajectories before and after major surgery in older adults. Ann Surg 2018; 268:911–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwarze ML, Barnato AE, Rathouz PJ, et al. Development of a list of high-risk operations for patients 65 years and older. JAMA Surg 2015; 150:325–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Medicare Provider and Analysis Review (MedPAR) Inpatient Admission Type Code from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Available at: https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/variables/medpar-inpatient-admission-type-code. Accessed August 5, 2021.

- 37.Gill TM, Han L, Gahbauer EA, et al. Functional effects of intervening illnesses and injuries after hospitalization for major surgery in community-living older persons. Ann Surg 2021; 273:834–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Becher RD, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, et al. Factors associated with functional recovery among older survivors of major surgery. Ann Surg 2020; 272:92–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee H, Shi SM, Kim DH. Home time as a patient-centered outcome in administrative claims data. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019; 67:347–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guralnik J Assessing physical performance in the older patient, https://sppbguide.com/training-videos.

- 41.Herbert C, Molinsky JH. What can be done to better support older adults to age successfully in their homes and communities? Health Aff (Millwood) 2019; 38:860–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirth V, Baskins J, Dever-Bumba M. Program of all-inclusive care (PACE): past, present, and future. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2009; 10:155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gill TM. Setting realistic expectations for an innovative program of home-based care for vulnerable older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc: 10.1111/jgs.17440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szanton SL, Leff B, Li QW, et al. CAPABLE program improves disability in multiple randomized trials. J Am Geriatr Soc: 10.1111/jgs.17383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Life Study Investigators, Pahor M, Blair SN, et al. Effects of a physical activity intervention on measures of physical performance: Results of the lifestyle interventions and independence for Elders Pilot (LIFE-P) study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006; 61:1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Ambrosius WT, et al. Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults: the LIFE study randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014; 311:2387–2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peduzzi P, Guo Z, Marottoli RA, et al. Improved self-confidence was a mechanism of action in two geriatric trials evaluating physical interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 2007; 60:94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quanjer PH, Lebowitz MD, Gregg I, et al. Peak expiratory flow: conclusions and recommendations of a Working Party of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J 1997; 24:2S-8S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arya S, Langston AH, Chen R, et al. Perspectives on home time and Its association with quality of life after inpatient surgery among US Veterans. JAMA Netw Open 2022; 5:e2140196–e2140196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kelley AS. Epidemiology of care for patients with serious illness. J Palliat Med 2013; 16:730–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szklo M Population-based cohort studies. Epidemiol Rev 1998; 20:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

On-line Supplemental Table S1: Complete List of 394 Operations Included in the Analysis by Operation Type

On-line Supplemental Figure 1. Distribution of Days Away from Home in the Year after Hospital Discharge for Major Elective and Non-Elective Surgery. The percentages are based on the total number of observations for each group.