Abstract

Background

Neuropsychiatric disturbances are common manifestations of dementia disorders and are associated with caregiver burden and affiliate stigma. The present study investigated affiliate stigma and caregiver burden as mediators for the association between neuropsychiatric symptoms of people with dementia (PWD) and caregiver mental health such as depression and anxiety.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey study was carried out with 261 dyads of PWD and informal caregivers from the outpatient department of a general hospital in Taiwan. The survey included the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI), the Affiliate Stigma Scale (ASS), the Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire (TPQ), and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). Mediation models were tested using the Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 4 for parallel mediation model; Model 6 for sequentially mediation model).

Results

Caregiver burden, affiliate stigma, caregiver depression, and caregiver anxiety were significantly associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms. After controlling for several potentially confounding variables, it was found that PWD’s neuropsychiatric symptoms, caregiver burden and affiliate stigma significantly explained 52.34% of the variance in caregiver depression and 37.72% of the variance in caregiver anxiety. The parallel mediation model indicated a significantly indirect path from PWD’s neuropsychiatric symptoms to caregiver mental health through caregiver burden and affiliate stigma, while the direct effect was not significant. Moreover, there was a directional association between caregiver burden and affiliate stigma in the sequential mediation model.

Conclusions

These findings show that it is imperative to improve caregivers’ perception of those with dementia to reduce internalized stigma and to improve caregivers’ mental health. Implementation of affiliate stigma assessment in clinical practice would allow distinctions to be made between the impact of affiliate stigma and the consequences of caregiver burden to help inform appropriate intervention.

Keywords: Affiliate stigma, Burden, Caregiver, Dementia, Mediation

Introduction

According to the World Alzheimer Report [1], approximately 46.8 million individuals are living with dementia globally. The number has not plateaued and it is predicted that it will increase to 131.5 million individuals by the year 2050 [2]. Therefore, large demands on caring for older people, especially those with dementia, are needed and such burden is usually relied on informal caregivers. Informal caregivers have been viewed as invisible second patients [3]. Indeed, providing care to a family member with disease can cause emotional, physical, and financial burden to the informal caregivers [4–6]. Among caregivers taking care of family member with different types of disease, those taking care of people with dementia (PWD) appear to have greater levels of psychological burden. Some research has reported that caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety than caring for patients with other illnesses [6–8]. A meta-analysis comprising 17 studies (N = 10,825 participants) reported a high prevalence of depression (34.0%) and anxiety (43.6%) for caregivers of patients with AD [9]. In Taiwan (where the present study was carried out), similar prevalence rates have been reported: 23.7–43.8% at risk of depression and 37.4% at risk of anxiety among informal caregivers of PWD [10, 11]. Therefore, the mental health of caregivers who take care of PWD should also be taken care of by healthcare providers.

The model proposed by Pearlin et al. [12] provides a potential psychological framework for healthcare providers to tackle mental health of caregivers of PWD. More specifically, the Stress Process Model (SPM) comprises the caregiving context (e.g., social and economic characteristics). Also, during the process, stressors (including objective indicators such as problematic behavior and subjective indicators such as burnout felt by caregivers) lead to psychological manifestations (e.g., depression, anxiety) via some mediators such as coping strategies [12]. Therefore, behavioral disturbances, particularly angry or aggressive behaviors among PWD, are objective stressors associated with caregiver depression [13–15]. Similarly, caring for PWD increases caregiving burden, a type of subjective stressor, and such subjective burden also increases the risk of having depression and anxiety symptoms [16]. In sum, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (e.g., irritability, agitation, aggression, apathy) together with the caregivers’ caregiving burden are potential stressors that can result in impaired mental health among caregivers of PWD [15, 17].

The burden experienced by caregivers is a result of many factors. As individuals gradually lose the ability to care for themselves, there is increasing need for supervision and assistance. Novak et al. [18] have identified five dimensions of subjective burden comprising (i) time-dependence burden (i.e., time cost of the caregiver), (ii) developmental burden (i.e., the caregivers’ feelings of being ‘off-time’ in their development with respect to their peers [e.g., missing out on what others do because of their caring duties]), (iii) physical burden (i.e., caregivers’ feelings of chronic fatigue and damage to their physical health, (iv) social burden (i.e., caregivers’ feelings of role conflict), and (v) emotional burden (i.e., caregivers’ negative feelings toward their care receivers). The five dimensions of subjective burden may result from the individual’s unpredictable and often bizarre behavior [18, 19]. Studies of caregiver burden have also shown that increases in the care-receiver’s behavioral and psychological symptoms are strongly correlated with caregiver burden [15, 20–22]. Moreover, care-receiver’s behavioral and psychological symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, irritability, depression) are significant predictors of caregiver burden [17].

One study by Werner et al. assessed four dimensions of affiliate stigma—interpersonal interaction, concealment, structural discrimination, and access to social roles conducted [23]. Caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease have especially high levels of affiliate stigma in the four aforementioned dimensions. Such affiliate stigma prevents informal caregivers from seeking the services that might reduce caregiver burden. Other family members may blame informal caregivers for providing a poor home environment or mismanaging PWD [24]. Informal caregivers may lose their jobs due to managing symptoms of PWD in emergency situations related to their wandering, falls, and basic needs. These may include employment discrimination or other forms of structural discrimination as well as loss of social relationships and experiences of harsh social judgments [25]. Therefore, caregivers may internalize negative stereotypes from the social stigma, resulting in affiliate stigma. In brief, affiliate stigma is a type of internalized stigma (i.e., the caregivers internalize the stigma themselves because of their relationship with PWD), and the negative effects of internalized stigma on mental health of stigmatized populations have been widely reported [26–28].

From the information mentioned above, affiliate stigma is another important factor that could contribute to caregiving burden and psychological distress of caregivers of PWD. Many caregivers suffer from stigma experiences because of their family member’s mental illness (i.e., courtesy stigma as defined by Goffman [29]), and such stigma experiences may be internalized by the caregivers and become affiliate stigma [26]. In other words, when a society treats the caregivers of PWD with negative perceptions, attitudes, emotions, and avoidant behaviors, caregivers are at risk of having negative experiences in emotional (e.g., anxiety), social (e.g., family burden) and interpersonal (e.g., isolation) aspects [30]. Indeed, empirical evidence has shown strong associations between affiliate stigma among informal caregivers and negative outcomes, including caregiver burden [11, 31], quality of life [32], depression [27, 28], anxiety [27, 28, 31].

In order to provide high quality programs to improve the mental health of caregivers who take care of PWD, it is crucial for healthcare providers to better understand the psychological mechanisms that underpin their psychological distress such as depression and anxiety. More specifically, different factors (e.g., PWD’s clinical characteristics and caregivers’ demographics) should be tested to yield the most important factors for healthcare providers to foster an efficient program. The best way to investigate the psychological mechanisms is to use a well-established theory or model. Therefore, the present study was guided by the SPM and proposes two mediation models (a parallel mediation model and a sequential mediation model). More specifically, the present study proposed and tested the mediating role of affiliate stigma and caregiver burden after controlling for several confounding variables associated with the PWD’s behavioral and psychological symptoms (e.g., PWD’s age, sex, marital status, employment status, education and relationship of caregiver, and patient’s age, sex, marital status). The present study’s simplified SPM retains the following factors derived from the original SPM: background information (treated as the confounding variables); primary stressors, including behavioral and psychological symptoms (treated as the independent variables), affiliate stigma, and caregiver burden (treated as the mediator); and depression and anxiety (treated as the outcome). While the PWD’s conditions cannot be changed, reducing affiliate stigma or caregiver burden could be effective in improving caregiver mental health if either of them was found to be a significant mediator. Furthermore, by separating stressors into affiliate stigma and caregiver burden, the present study also addresses the question of which approach caregiver support services should be more emphasized.

To the best of the present authors’ knowledge, no empirical evidence has been reported regarding whether the SPM could be an effective model in explaining mental health consequences among caregivers of PWD. Therefore, the present study sought to address this knowledge gap in the literature on PWD through two types of mediation model examining the severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms that affect caregiver depression and anxiety. It was hypothesized that caregivers experiencing increasing levels of affiliate stigma would be more likely to report higher levels of depression and anxiety, and that the relationship between neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver mental health would be mediated by caregiver burden and affiliate stigma.

Methods

Participants and data collection

A cross-sectional survey study utilizing convenience sampling was designed to collect data from a dementia care center at a general hospital located in Southern Taiwan. 300 caregivers who took care of the patients with dementia at home were invited to participate in the study. More specifically, several psychiatrists in the dementia care center screened potential participants (please see the inclusion and exclusion criteria below for details) when the informal caregivers and the PWD visited the dementia care center for daycare service. Then, the psychiatrists transferred the eligible participants to several research assistants to further confirm the eligibility of the participants. When the eligibility was confirmed, the research assistants led the participants to a quiet room to complete the self-reported measures using pen and paper. After excluding those who had incomplete data (n = 39), the final data used for analyses included 261 patient-caregiver dyads (i.e., 87% of response rate). All the participants (i.e., both caregivers and patients) provided their informed consent after being told of the study purpose. For those who had severely impaired cognitive capacity, consent was obtained from their legally authorized representatives following assessment by their treating psychiatrist(s). The study’s inclusion criteria were: (i) ability to speak, understand and read Mandarin Chinese or Taiwanese, (ii) each caregiver participant had at least one family member aged older than 65 years (because young-onset dementia is conventionally thought to include patients with onset before the age of 65 years [33], and this cutoff point is indicative of a sociological partition in terms of employment and retirement age) with any type of diagnosed dementia (including AD and vascular dementia), and (iii) each caregiver participant was aged at least 20 years because the Civil Law in Taiwan sets 20 years as the age of adulthood. Caregivers who were diagnosed with a mental illness or had problems in understanding the survey questions were excluded. All procedures used for the present study were approved by the institutional review board of the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (IRB 102-3378B).

Measures

In the present study, all assessment items asked the current condition of each participant, except for those assessing depression and anxiety which concerned the condition over the past week. In addition, demographic information concerning the caregivers was collected (i.e., age, sex, years of education, marital status, employment status, relationship to the person with dementia) and the demographic variables for the person with dementia they cared for (i.e., age, sex, marital status, and neuropsychiatric symptoms).

Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI)

The 24-item Chinese version of the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) was used to assess caregivers’ burden in taking care of PWD. The CBI also provides a brief and comprehensive measure of caregiver burden that makes it a practical tool for assessing and responding to caregiver burden [19]. The CBI has five burden subscales (time-dependent = 5 items, developmental = 5 items, physical = 4 items, social = 4 items, and emotional = 6 items). Each CBI item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The total CBI score ranges from 0 to 96, where a higher score indicates a higher the level of caregiver burden [18]. The overall scale has been shown to have excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.91) [19].

Affiliate Stigma Scale (ASS)

The 22-item Chinese version of the Affiliate Stigma Scale (ASS) was used to assess caregivers’ internalization of stigma [26]. This theory driven instrument was designed for easy and practical use in clinical settings due to the fewer items, and its appropriateness for a wide range of family caregivers including children, spouses, grandchildren, and other relatives [27, 28]. The ASS has three subscales (cognitive = 7 items, affect = 7 items, and behavior = 8 items). Each ASS item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The total ASS score ranges from 22 to 88, where a higher score indicates a higher the level of affiliate stigma. The psychometric properties of the ASS have been tested for caregivers of family members with dementia and has been shown to have very good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.82–0.85) [27].

Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire (TDQ)

The 18-item Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire (TDQ) was used to assess caregivers’ depressive symptoms [34]. The TDQ was constructed for experiences among the Taiwanese population. Consequently, the TDQ has been widely used as a screening tool for studies conducted in Taiwan [35]. Each TDQ item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no or extremely few, < 1 day per week) to 3 (often or always, 5–7 days per week). The total TDQ score ranges from 0 to 54, where a higher score indicates a higher the level of depression. The overall scale has been shown to have excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.90) [34].

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The 21-item Chinese version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was used to assess caregivers’ anxiety [36]. The BAI is a brief somatic symptoms-focused screening tool that was specifically developed as a measure to discriminate between anxiety and depression [37]. Each BAI item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severe [“I could barely stand it”]) [38]. The total BAI score ranges from 0 to 63, where a higher score indicates a higher the level of anxiety. The overall scale has been shown to have excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.95, Guttman split-half coefficient = 0.91) [36].

Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)

The severity and frequency of behavioral and psychological symptoms of PWD were assessed using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) [39]. The NPI comprises 12 domains that are symptoms associated with dementia (i.e., delusions, hallucinations, agitation, dysphoria, anxiety, apathy, irritability, euphoria, disinhibition, aberrant motor behavior, night-time behavior disturbances, and appetite and eating abnormalities). The NPI is a general outcome measure that is widely used to assess behavioral changes for patients with dementia [40]. The participants in the present study (i.e., caregivers of the PWD) were asked to rate the frequency of the symptoms of that domain on a scale ranging from 1 (occasionally, less than once per week) to 4 (very frequently, once, or more per day or continuously) and the severity of the same symptoms on a scale ranging from 1 (mild) to 3 (severe). The total NPI score ranges from 0 to 120, where a higher score indicates a higher the level of behavioral and psychological symptoms. The overall scale has been shown to have good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.88 and a test–retest correlation of 0.79 for frequency and 0.86 for severity [41]).

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 22 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Descriptive statistics were carried out to compute means and standard deviations as well as internal consistency. Bivariate Pearson’s correlations were used to assess the associations between study variables.

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses were performed, with neuropsychiatric symptoms as the predictor, affiliate stigma and caregiver burden as proposed mediators, and the severity of depression and anxiety as the outcome measures. Covariates in the regression models included age, sex, marital status, employment status, education, and relationship of caregiver, and PWD’s age, sex, marital status. The parallel mediation (Model 4 in Hayes’ PROCESS macro) and the sequential multiple mediation (Model 6 in Hayes’ PROCESS macro) of PROCESS macro developed by Hayes [42] were conducted. In the parallel mediation model, the mediating effect of PWDs’ NPI on caregiver depression or anxiety were examined through caregiver burden and affiliate stigma. Sequential multiple mediation analysis was used to determine the effects of mediators in the models. Bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval (CI) based on 5000 bootstrapping samples with a 95% level of confidence was used to examine the mediation effects (i.e., indirect effects). When the confidence intervals do not include zero, the mediation effect is interpreted as significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the 261 patient-caregiver dyads. Overall, the gender distribution was approximately equal for the caregivers with mean age of 52.9 years (SD ± 12.3). On average, the caregivers had received 11.2 years of education (SD ±4.2). Most of the caregivers were children of PWD (60.9%), had full-time employment (more than 30 hours per week) (52.5%), were married (78.2%), were living with PWD (70.9%), and were a primary caregiver (83.14%). Nearly half of caregivers (49.43%) self-reported caring for PWD for more than 8 hours a day on average, and 26.43% of them were caring for PWD all-day. Regarding the psychosocial characteristics of the caregivers, the mean score was 40.0 (out of 96) for caregiver burden (SD ± 19.1), 35.2 (out of 88) for affiliate stigma (SD ± 11.0), 12.7 (out of 54) for depression (SD ± 11.2), and 7.9 (out of 63) for anxiety (SD ± 8.8). Nearly two-thirds of the PWD (63.6%) were females with a mean age of 79.3 years (SD ± 6.8). Slightly more than half of the PWD were married (55.2%). Moreover, the mean score for neuropsychiatric symptoms of the PWD was 18.7 (out of 120) (SD ± 20.4); more than three-quarters of PWD (75.9%) had Clinical Dementia Rating Stage 0.5–1, with Stage 1 being the majority.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Mean ± SD | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Caregivers | ||

| Age (in years) | 52.92 ± 12.33 | 261 (100) |

| Years of education | 11.22 ± 4.22 | 261 (100) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 125 (47.9) | |

| Female | 136 (52.1) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 204 (78.2) | |

| Single | 36 (13.8) | |

| Other | 21 (8.1) | |

| Employment status | ||

| Full-time employment (>30 hours per week) | 137 (52.5) | |

| Part-time employment (≦30 hours per week) | 6 (2.3) | |

| Housekeeper | 52 (19.9) | |

| Retired | 43 (16.5) | |

| No employment | 23 (8.8) | |

| Relationship with PWD | ||

| Children | 159 (60.9) | |

| Spouse | 37 (14.2) | |

| Other | 65 (24.9) | |

| Caregiver burden (range: 0–96) | 39.95 ± 19.18 | |

| Affiliate stigma (range: 22–88) | 35.19 ± 10.99 | |

| Depression (range: 0–54) | 12.66 ± 11.22 | |

| Anxiety (range: 0–63) | 7.93 ± 8.80 | |

| People with dementia | ||

| Age (in years) | 79.28 ± 6.78 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 95 (36.4) | |

| Female | 166 (63.6) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 144 (55.2) | |

| Widowed /Divorced /Single/Separated | 117 (44.8) | |

| Neuropsychiatry Inventory (range: 0–120) | 18.74 ± 20.37 | |

Note, PWD People with dementia

Table 2 shows the bivariate correlations between the studied variables. The results showed that neuropsychiatric symptoms were positively associated with caregiver burden (r = .44, p < .01), affiliate stigma (r = .34, p < .01), caregiver depression (r = .36, p < .01) and with caregiver anxiety (r = .35, p < .01). Table 2 additionally demonstrates how neuropsychiatric symptoms, caregiver burden, affiliate stigma, depression, and anxiety associated with other demographic characteristic of caregivers and PWD.

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlations among the study variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NPI (X) | – | |||||||||||||

| 2. CBI (M1) | 0.44** | – | ||||||||||||

| 3. ASS (M2) | 0.34** | 0.65** | – | |||||||||||

| 4. TDQ (Y1) | 0.36** | 0.67** | 0.55** | – | ||||||||||

| 5. BAI (Y2) | 0.35** | 0.53** | 0.49** | 0.80** | – | |||||||||

| 6. Cg Age | 0.05 | −0.15* | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | – | ||||||||

| 7. Cg Sex | 0.16** | 0.19** | 0.02 | 0.21** | 0.23** | −0.14* | – | |||||||

| 8. Cg Marital status | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.08 | −0.30** | 0.16** | – | ||||||

| 9. Cg Job | 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.14* | 0.21** | 0.26** | 0.11 | – | |||||

| 10. Cg Years of education | −0.15* | 0.09 | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.03 | − 0.55** | −0.16** | 0.18** | −0.10 | – | ||||

| 11. Relation | − 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.11 | − 0.04 | − 0.01 | −0.70** | 0.16** | 0.15* | −0.05 | 0.46** | – | |||

| 12. PWD sex | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.00 | −0.06 | − 0.10 | 0.14* | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.11 | – | ||

| 13. PWD Marital status | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | − 0.02 | −0.02 | − 0.23** | 0.02 | 0.23** | 0.01 | 0.13* | 0.33** | 0.22** | – | |

| 14. PWD age | −0.06 | − 0.12 | −0.26** | − 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.16** | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.27** | 0.04 | 0.17** | – |

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, NPI Neuropsychiatry Inventory, CBI Caregiver Burden Inventory, ASS Affiliate stigma scale, TDQ Taiwanese Depressive Questionnaire, BAI Beck Anxiety Inventory, Cg caregiver, PWD People with dementia, X independent variable; M1 and M2: mediator; Y1 and Y2: dependent variable

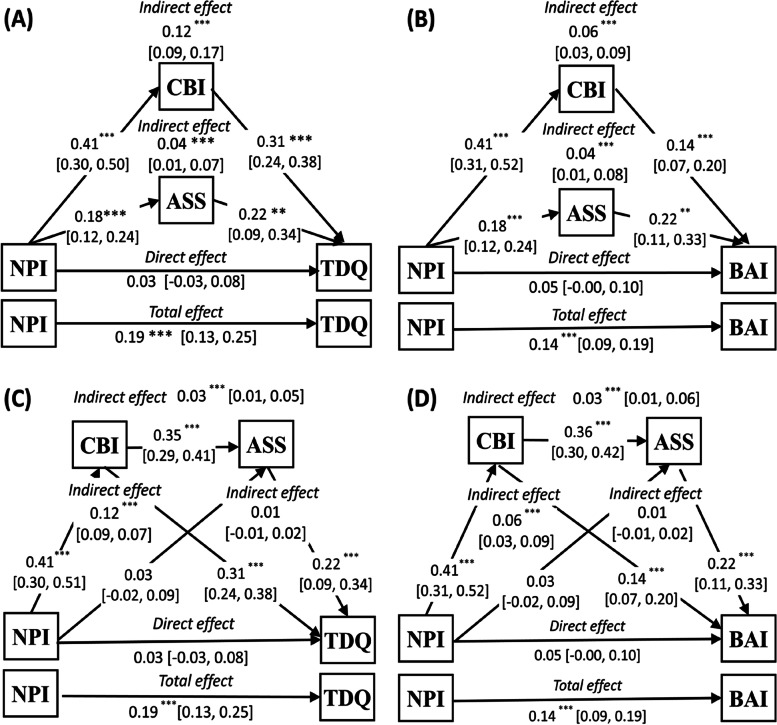

Four mediation models were carried out (Fig. 1 and Table 3). The first mediation model (Model A; Table 3 and Fig. 1 A) showed that the direct effect of PWDs’ neuropsychiatric symptoms on caregiver depression was not statistically significant (β = 0.03, p = .32) However, this mediation model showed a significant indirect path from PWDs’ neuropsychiatric symptoms to caregiver depression via caregiver burden (β = 0.12, 95% CI [0.09, 0.17]) and affiliate stigma (β = 0.04, 95% CI [0.01, 0.07]).

Fig. 1.

A Parallel mediation model with affiliate stigma (ASS) and caregiver burden (CBI) as mediators between behavioral and psychological symptoms (NPI) and depression (TPQ). B Parallel mediation model with ASS and CBI as mediators between NPI and anxiety (BAI). C Sequential mediation model with CBI and ASS as mediators between NPI and TPQ. D Sequential mediation model with CBI and ASS as mediators between NPI and BAI. All models controlled for age, sex, marital status, employment status, education and relationship of caregiver, and patient’s age, sex, marital status. * p <.05, ** p <.01, ***p<0.001

Table 3.

Models of the effect of patient’s behavioral and psychological symptoms on mental health of caregivers with mediators of caregiver burden and affiliate stigma

| Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | Coefficient | SE | t | p |

| Total effect of NPI on TDQ (without accounting the potential mediators) | 0.19 | 0.03 | 5.86 | < 0.001 |

| Direct effect of NPI on TDQ in mediated model | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.32 |

| Indirect effect of NPI on TDQ | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Total indirect effect | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.21 |

| Indirect effect via CBI | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.17 |

| Indirect effect via ASS | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 |

| (B) | Coefficient | SE | t | p |

| Total effect of NPI on BAI (without accounting the potential mediators) | 0.14 | 0.03 | 5.58 | < 0.001 |

| Direct effect of NPI on BAI in mediated model | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.95 | 0.05 |

| Indirect effect of NPI on BAI | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Total indirect effect | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.14 |

| Indirect effect via CBI | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Indirect effect via ASS | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.07 |

| (C) | Coefficient | SE | t | p |

|

Total effect of NPI on TDQ (without accounting the potential mediators) |

0.19 | 0.03 | 5.63 | < 0.001 |

| Direct effect of NPI on TDQ in mediated model | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.32 |

| Indirect effect of NPI on TDQ | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Total indirect effect | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.21 |

| Indirect effect via CBI | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.17 |

| Indirect effect via ASS | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Indirect effect via CBI and ASS | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| (D) | Coefficient | SE | t | p |

| Total effect of NPI on BAI (without accounting the potential mediators) | 0.14 | 0.03 | 5.73 | < 0.001 |

| Direct effect of NPI on BAI in mediated model | 0.05 | 0.02 | 1.93 | 0.05 |

| Indirect effect of NPI on BAI | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Total indirect effect | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| Indirect effect via CBI | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Indirect effect via ASS | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Indirect effect via CBI and ASS | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

Boot bootstrapping, LLCI lower limit confidence interval, ULCI upper limit confidence interval, SE standard error. (A) & (C) Unstandardized coefficients for the associations of affiliate stigma and caregiver burden with patient’s behavioral and psychological symptoms for model predicting depression of caregiver. (B) & (D) Unstandardized coefficients for the associations of affiliate stigma and caregiver burden with patient’s behavioral and psychological symptoms for model predicting anxiety of caregiver

The second mediation model (Model B; Table 3 and Fig. 1 B) showed that the direct effect of PWDs’ neuropsychiatric symptoms on caregiver anxiety was not statistically significant (β = 0.05, p = .054). However, this mediation model showed a significant indirect path from PWDs’ neuropsychiatric symptoms to caregiver anxiety via caregiver burden (β = 0.06, 95% CI [0.03, 0.09]) and affiliate stigma (β = 0.04, 95% CI [0.01, 0.07]).

The third mediation model (Model C; Table 3 and Fig. 1 C) showed that the direct effect of PWD’s neuropsychiatric symptoms on caregiver depression was not statistically significant (β = 0.03, p = .32). However, this sequential mediation model showed a significant indirect path from PWDs’ neuropsychiatric symptoms to caregiver depression via caregiver burden and affiliate stigma (β = 0.03, 95% CI [0.01, 0.05]). This model explained 52.34% of the variance in depression.

The final mediation model (Model D; Table 3 and Fig. 1 D) showed that the direct effect of PWD’s neuropsychiatric symptoms on caregiver anxiety was not statistically significant (β = 0.03, p = .05). However, this sequential mediation model showed a significant indirect path from PWDs’ neuropsychiatric symptoms to caregiver anxiety via caregiver burden and affiliate stigma (β = 0.06, 95% CI [0.03, 0.09]). This model explained 37.72% of the variance in anxiety.

Discussion

The results of the present study supported the simplified Stress Process Model (SPM) that affiliate stigma and caregiver burden mediated the association of PWDs’ behavioral and psychological symptoms and caregivers’ mental health. More specifically, the present study examined two mediation models, and the significant association between NPI score and affiliate stigma (Fig. 1 A, Fig. 1 B) became nonsignificant when affiliate stigma was positioned after caregiver burden (Fig. 1 C, Fig. 1 D). To the best of the present authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to examine whether caregiver burden and affiliate stigma are mediators in the association between behavioral and psychological symptoms and caregiver mental health. These findings indicated that there could be a directional association between these two mediators, such that caregiver burden may reduce affiliate stigma, which subsequently may improve the psychological health of caregivers. However, the cross-sectional design in the present study cannot provide evidence for these proposed directions. Only longitudinal designs can corroborate the directions proposed in the present study.

Previous studies have shown that affiliate stigma has an important effect on caregiver burden and that the caregiver dimension of affiliate stigma has the greatest impact [43]. The results of the present study concur with the literature in the finding that caregiver burden is a significant predictor of affiliate stigma [11, 44]. In order to better understand the mediating role of affiliate stigma for caregivers of PWD, the present study analyzed both a parallel mediation model (Table 3 and Fig. 1 A, Fig. 1 B) and a sequential mediation model (Table 3 and Fig. 1 C, Fig. 1 D). Results from both models were generally comparable. However, the association between NPI score and affiliate stigma was not found in sequential mediation model, only the parallel mediation model. Parallel mediation analysis showed that the two mediators (caregiver burden, affiliate stigma) fully mediated the relationship between PWDs’ behavioral and psychological symptoms and caregiver mental health. However, while caregiver burden was found to significantly contribute to the overall indirect effect, affiliate stigma did not mediate the relationship between PWDs’ behavioral and psychological symptoms and caregiver mental health in the sequential mediation model.

The aforementioned findings indicate that there might be a directional association between these two mediators. More specifically, caregiver burden may reduce affiliate stigma, which may subsequently improve the psychological health of caregivers. Nevertheless, the effect of affiliate stigma on mental health for caregivers of PWD was consistent between the two models. Therefore, a tentative conclusion is that affiliate stigma is an important factor in caregiver burden, with caregiver burden as the primary mediator. The finding of affiliate stigma as a mediator suggests that providing support services to caregivers to improve their mental health could also reduce caregiver burden.

The results of the present study indicated that experiencing subjective caregiver burden was associated with increased risk of psychological distress. These findings are consistent with previous findings [45–47] and in line with SPM (i.e., primary stressors such as caregiver burden leads to mental health problems such as psychological distress) [12]. Moreover, caregivers of PWD are reported to have poorer mental health and a higher level of psychological distress than those who are caring for individuals with a physical disability [48, 49]. The health problems, especially mental health problems, among caregivers of PWD are likely to be explained by their caregiver burden. It is challenging for caregivers of PWD to take care of their family member’s disruptive behaviors comprising behavioral and psychological symptoms resulting from their dementia [50, 51]. Such caregiver burden may be additional to the feelings of embarrassment and shame, which are further associated with affiliate stigma.

The results of the present study concur with the prior findings [27, 28] that affiliate stigma is positively associated with depression and anxiety. Therefore, the positive relationships between affiliate stigma and psychological distress can be explained by the reason that caregivers of PWD feel themselves as inferior (i.e., endorse stigma in themselves) and the negative opinions toward themselves increase their mood problems, such as psychological distress. Accordingly, healthcare providers and social services may consider developing appropriate interventions to reduce affiliate stigma. Given that affiliate stigma was found to be associated with depression and anxiety, the reduction of affiliate stigma is needed to help caregivers improve their psychological distress. Subsequently, other benefits, such as improved outcomes for PWD, may also be gained.

Limitations

The present study has some limitations. First, participants were from a convenience sample of PWD and their caregivers with referrals from the same area in Taiwan. Therefore, the findings may not be generalized to those who might not have been referred, because of the differences in types of dementia, need for caregiver assistance, and use of healthcare services. Second, the study was cross-sectional study and therefore causal relationships were unable to be determined. Future research should ideally comprise a longitudinal design, which can assess studied variables across time and provide stronger evidence for causal relationships. Third, the sample size in the present study was relatively small. However, the main analyses (i.e., the mediation models) were based on 5000 bootstrapped samples, which are robust and unlikely to have power issues [52]. However, given that the sample consisted of a small subset of kinship, future studies should separate these kinships of affiliate stigma in order to examine the distinct main effects.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, the present study provides new knowledge that caregiver burden and affiliate stigma were found to mediate the relationship between behavioral and psychological symptoms and caregivers’ psychological distress. Therefore, by considering mental health concerns in intervention or prevention measures in helping caregivers of PWD, it may provide more effective approaches to decrease psychological distress and potential negative consequences of the caregiver burden, especially in relation to their depression and anxiety. Future similar studies with bigger and more representative samples across different countries and cultures may help support the generalizability of the findings and better understand the mechanisms underlying the associations between dementia and affiliate stigma.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Department of Psychiatry, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, for their help with data collection.

Abbreviations

- PWD

People with Dementia

- CBI

Caregiver Burden Inventory

- ASS

Affiliate Stigma Scale

- TDQ

Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire

- BAI

Beck Anxiety Inventory

- AD

Alzheimer’s Disease

- SPM

Stress Process Model

- NPI

Neuropsychiatric Inventory

- OLS

Ordinary Least Squares

- CI

Confidence Interval

Authors’ contributions

J-AS, C-CC, H-CT, and C-YL created and organized the study and collected the data. J-YC, C-hL, and C-YL wrote the first draft and analyzed data. C-YL and H-CT provided the directions of data analysis. Y-JC, J-SC, C-hL, C-YL, and MDG interpreted the data results. MDG supervised the entire study and was responsible for all final editing. All the authors critically reviewed the manuscript and provided constructive comments.

Funding

This research was supported by grant CMRPG6C0451 from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. This research was also supported in part by (received funding from) the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-11A1-CG-CO-04-2225-1) and grants from Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, Taiwan, under Grant TCRD110–44.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available owing to patient privacy and ethical issues. However, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (IRB 102-3378B). All participants and their legal guardians were informed about the study goals. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians prior to the study enrollment according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants as well as their relatives or legal guardians could withdraw consent at any time.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hsin-Chi Tsai, Email: cssbmw45@gmail.com.

Chih-Cheng Chang, Email: rabiata@gmail.com.

Chung-Ying Lin, Email: cylin36933@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Prince M, Comas-Herrera A, Knapp M, Guerchet M, Karagiannidou M. World Alzheimer report 2016: improving healthcare for people living with dementia: coverage, quality and costs now and in the future. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prince MJ, Wimo A, Guerchet MM, Ali GC, Wu Y-T, Prina M. World Alzheimer report 2015-the global impact of dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodaty H, Donkin M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(2):217–228. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/hbrodaty. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sörensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2002;42(3):356–372. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douglas SL, Daly BJ, Kelley CG, O'Toole E, Montenegro H. Impact of a disease management program upon caregivers of chronically critically ill patients. Chest. 2005;128(6):3925–3936. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson B, Tatangelo G, McCabe M. Depression and anxiety among partner and offspring carers of people with dementia: a systematic review. Gerontologist. 2019;59(5):e597–e610. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(2):250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1052–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sallim AB, Sayampanathan AA, Cuttilan A. Ho RC-M: prevalence of mental health disorders among caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(12):1034–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang SS, Liao YC, Wang WF. Association between caregiver depression and individual behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in Taiwanese patients. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2015;7(3):251–259. doi: 10.1111/appy.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su J-A, Chang C-C. Association between family caregiver burden and affiliate stigma in the families of people with dementia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2772. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Covinsky KE, Newcomer R, Fox P, Wood J, Sands L, Dane K, Yaffe K. Patient and caregiver characteristics associated with depression in caregivers of patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(12):1006–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.30103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuijpers P. Depressive disorders in caregivers of dementia patients: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(4):325–330. doi: 10.1080/13607860500090078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolanowski A, Boltz M, Galik E, Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Resnick B, Van Haitsma KS, Knehans A, Sutterlin JE, Sefcik JS, et al. Determinants of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a scoping review of the evidence. Nurs Outlook. 2017;65(5):515–529. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper C, Balamurali TBS, Livingston G. A systematic review of the prevalence and covariates of anxiety in caregivers of people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(2):175–195. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206004297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torrisi M, De Cola MC, Marra A, De Luca R, Bramanti P, Calabrò RS. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia may predict caregiver burden: a Sicilian exploratory study. Psychogeriatrics. 2017;17(2):103–107. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novak M, Guest C. Application of a multidimensional Caregiver Burden Inventory. Gerontologist. 1989;29(6):798–803. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.6.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou KR, Jiann-Chyun L, Chu H. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Caregiver Burden Inventory. Nurs Res. 2002;51(5):324–31. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ornstein K, Gaugler JE. The problem with "problem behaviors": a systematic review of the association between individual patient behavioral and psychological symptoms and caregiver depression and burden within the dementia patient-caregiver dyad. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(10):1536–1552. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiao CY, Wu HS, Hsiao CY. Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62(3):340–350. doi: 10.1111/inr.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terum TM, Andersen JR, Rongve A, Aarsland D, Svendsboe EJ, Testad I. The relationship of specific items on the neuropsychiatric inventory to caregiver burden in dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(7):703–717. doi: 10.1002/gps.4704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Werner P, Heinik J. Stigma by association and Alzheimer's disease. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(1):92–99. doi: 10.1080/13607860701616325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stites SD, Milne R, Karlawish J. Advances in Alzheimer's imaging are changing the experience of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2018;10:285–300. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosin ER, Blasco D, Pilozzi AR, Yang LH, Huang X. A narrative review of Alzheimer's disease stigma. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;78(2):515–528. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mak WW, Cheung RY. Affiliate stigma among caregivers of people with intellectual disability or mental illness. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2008;21(6):532–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00426.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang CC, Su JA, Lin CY. Using the affiliate stigma scale with caregivers of people with dementia: psychometric evaluation. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0213-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saffari M, Lin CY, Koenig HG, O'Garo KN, Broström A, Pakpour AH. A Persian version of the Affiliate Stigma Scale in caregivers of people with dementia. Health Promot Perspect. 2019;9(1):31–9. doi: 10.15171/hpp.2019.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon and Schuster; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park S, Park KS. Family stigma: a concept analysis. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2014;8(3):165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pugh M, Perrin PB, Watson JD, Kuzu D, Tyler C, Villaseñor T, et al. Psychometric investigation of the Affiliate Stigma Scale in Mexican Parkinson’s disease caregivers: development of a short form. NeuroRehabilitation. 2021:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Zhang Y, Subramaniam M, Lee SP, Abdin E, Sagayadevan V, Jeyagurunathan A, Chang S, Shafie SB, Abdul Rahman RF, Vaingankar JA, et al. Affiliate stigma and its association with quality of life among caregivers of relatives with mental illness in Singapore. Psychiatry Res. 2018;265:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossor MN, Fox NC, Mummery CJ, Schott JM, Warren JD. The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(8):793–806. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70159-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee Y, Lin PY, Hsu ST, Cing-Chi Y, Yang LC, Wen JK. Comparing the use of the Taiwanese depression questionnaire and Beck Depression Inventory for screening depression in patients with chronic pain. Chang Gung Med J. 2008;31(4):369–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun YC, Chen CL, Wen SH. Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire revisit: factor structure and measurement invariance across genders. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118(9):1356–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Che HHLM, Chen HC, Chang SW, Lee YL. Validation of the Chinese version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory [in Chinese] Formos J Med. 2006;10(4):447–54. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oh H, Park K, Yoon S, Kim Y, Lee SH, Choi YY, et al. Clinical utility of Beck Anxiety Inventory in clinical and nonclinical Korean samples. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–897. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cummings JL. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology. 1997;48(5 Suppl 6):S10–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Fuh JL, Lam L, Hirono N, Senanarong V, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric Inventory workshop: behavioral and psychologic symptoms of dementia in Asia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(4):314–7. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213853.04861.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Hayes AF. Heteroscedasticity-consistent standard error estimates for the linear regression model: SPSS and SAS implementation. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Werner P, Mittelman MS, Goldstein D, Heinik J. Family stigma and caregiver burden in Alzheimer's disease. Gerontologist. 2012;52(1):89–97. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mak WW, Cheung RY. Psychological distress and subjective burden of caregivers of people with mental illness: the role of affiliate stigma and face concern. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48(3):270–274. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9422-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Lee J, Bakker TJ, Duivenvoorden HJ, Dröes RM. Multivariate models of subjective caregiver burden in dementia: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;15:76–93. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Del-Pino-Casado R, Rodríguez Cardosa M, López-Martínez C, Orgeta V. The association between subjective caregiver burden and depressive symptoms in carers of older relatives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2019;14(5):e0217648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Del-Pino-Casado R, Priego-Cubero E, López-Martínez C, Orgeta V. Subjective caregiver burden and anxiety in informal caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0247143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moon H, Dilworth-Anderson P. Baby boomer caregiver and dementia caregiving: findings from the National Study of caregiving. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):300–306. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riffin C, Van Ness PH, Wolff JL, Fried T. Family and other unpaid caregivers and older adults with and without dementia and disability. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(8):1821–1828. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in clinical settings: recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):762–769. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spiegl K, Luttenberger K, Graessel E, Becker L, Scheel J, Pendergrass A. Predictors of institutionalization in users of day care facilities with mild cognitive impairment to moderate dementia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1009. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-07017-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available owing to patient privacy and ethical issues. However, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.