Abstract

To address the unintended consequences of public health measures during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., emergency food insecurity, income loss), non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have partnered with diverse actors, including religious leaders, to provide humanitarian relief in resource-constrained communities. One such example is the Rapid Emergencies and Disasters Intervention (REDI), which is an NGO-led program in the Philippines that leverages a network of volunteer religious leaders to identify and address emergency food insecurity among households experiencing poverty. Guided by a realist evaluation approach, the objectives of this study were to identify the facilitators and barriers to effective implementation of REDI by religious leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic and to explore the context and mechanisms that influenced REDI implementation. In total, we conducted 25 virtual semi-structured interviews with religious leaders actively engaged in REDI implementation across 17 communities in Negros Occidental, Philippines. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and thematically analyzed. Three main context-mechanism configurations were identified in shaping effective food aid distribution by religious leaders, including program infrastructure (e.g., technical and relational support from partner NGO), social infrastructure (e.g., social networks), and community infrastructure (e.g., community assets as well as a broader enabling environment). Overall, this study contributes insight into how the unique positionality of religious leaders in combination with organizational structures and guidance from a partner NGO shapes the implementation of a disaster response initiative across resource-constrained communities. Further, this study describes how intersectoral collaboration (involving religious leaders, NGOs, and local governments) can be facilitated through an NGO-led disaster response network.

Keywords: Food aid, Disaster response, Community-based response, Humanitarian crisis, Non-governmental organizations, Southeast Asia

1. Introduction

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the unintended consequences of pandemic-related public health measures have disproportionately impacted resource-constrained communities and populations experiencing poverty. Globally, income loss, mobility restrictions, and associated food insecurity have contributed to a humanitarian crisis in some regions [1,[2], [3]]. Within this challenging context, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are mobilizing to meet immediate needs, including addressing emergency food insecurity, within resource-constrained communities [[3], [4]]. To support these mobilization efforts and facilitate community-based disaster response, some NGOs partner with networks of local community-based actors, including religious leaders and institutions.

In the context of humanitarian crises, religious leaders are uniquely positioned to provide multiple forms of support (e.g., physical resources, psychosocial support) in their communities. Indeed, previous research has pointed to how the geographic and social location of religious leaders in many communities, including remote areas, can create effective distribution systems for humanitarian aid [5,6]. Further, religious leaders are often regarded as trusted and influential members of communities, which can facilitate humanitarian aid responses, especially during times of uncertainty or when there is mistrust of government institutions [[7], [8], [9]]. Despite these potential contributions, there remains limited understanding of the role of religious leaders and institutions in the context of disaster response [10], especially in the Global South [6].

Building a more comprehensive understanding of the ways in which religious leaders contribute to disaster response and humanitarian relief efforts is important in light of global frameworks that promote collaboration among diverse actors within disaster risk reduction (e.g., 2015 Sendai Framework). Further, in the context of a public health crisis, there is a need to examine the contributions of religious leaders in addressing the unintended consequences of pandemic-related public health measures. In response, this study examines the experiences of religious leaders in addressing pandemic-related emergency food insecurity in the Philippines and evaluates a disaster response program administered through a collaboration between a Philippines-based NGO and a network of volunteer religious leaders. Overall, the objectives of this study were: 1) to identify the facilitators and barriers to effective implementation of an NGO's disaster response network by religious leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic; and 2) to explore the context and mechanisms that influenced the implementation of the disaster response network. Importantly, this study contributes insight into how the positionality of religious leaders, in combination with organizational structures and guidance from an NGO, shape the implementation of a disaster response initiative across resource-constrained communities.

1.1. The Rapid Emergencies and Disasters Intervention (REDI)

This study was conducted in partnership with International Care Ministries (ICM), which is a faith-based non-governmental organization (NGO) in the Philippines. ICM provides community-based poverty alleviation and health promotion programming to households experiencing extreme poverty through 12 regional bases in the Visayas and Mindanao [[11], [12]]. Further, there are approximately 10,000 religious leaders located across the Philippines that volunteer with ICM to support the implementation of the organization's programming in the communities where they live [13].

Recognizing the unacceptable lag time between a disaster event and the delivery of humanitarian assistance by external multi-lateral humanitarian organizations, the Rapid Emergencies and Disasters Intervention (herein referred to as REDI) was developed by ICM to more quickly respond to emergencies affecting households experiencing extreme poverty. Initially established after Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, REDI leverages ICM's existing network of volunteer religious leaders to monitor and report, in real time, local needs prior to and immediately following a disaster (e.g., typhoon, flood). When a need is documented in REDI by a religious leader (through SMS, message through REDI platform, or phone call), emergency humanitarian assistance can be quickly mobilized through one of ICM's 12 bases. The assistance (food aid, including nutrient fortified food packs and seeds for small scale agriculture) is then delivered by the religious leader to the household or community in need.

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, REDI was reconfigured to address the immediate and emergency food needs of households experiencing extreme poverty. More specifically, loss of employment and income connected to widespread and sustained lockdowns meant that many households experiencing poverty faced emergency food insecurity. Importantly, religious leaders connected to REDI were already embedded within their communities, providing local insights and real-time monitoring of emergent needs in the context of sporadic community quarantines that made travel across jurisdictions difficult. Since the introduction of quarantine measures across the Philippines in March 2020, ICM has used REDI to assess community needs and deliver food aid to over 5.3 million households, with approximately 15,000 religious leaders actively engaged in monitoring, reporting, and addressing local emergency food insecurity.

REDI is a national program that operates across hundreds of communities in the Philippines. As such, while ICM has standardized program protocols in place, REDI also has an inherent flexibility in order to be effective in different contexts with varying needs. For instance, while organizational guidelines exist to determine household aid eligibility, REDI implementers are also given autonomy to assess local needs and request a quantity of aid accordingly (within allocation limits), recognizing their particular knowledge of their communities as religious leaders. The program's adaptability has also been important during the COVID-19 pandemic, whereby restrictions have varied across communities and municipalities and invariably affected aid distribution and overall program implementation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Evaluation approach and methods

We used realist evaluation to identify the facilitators and barriers to effective implementation of REDI by religious leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic and to explore how various context-mechanism configurations affected implementation. Realist evaluation is a theory-driven evaluation approach that aims to determine how a program works and how different program components interact to shape program implementation and outcomes [14]. Further, realist evaluation assesses the implementation of an intervention through the lens of what worked, for whom, under what conditions, and why [15]. Thus, we sought to identify and describe the interactions among the context and mechanisms that facilitated REDI implementation and outcomes [16].

To conduct the realist evaluation, we used qualitative methods (e.g., semi-structured interviews). Qualitative methods have frequently been used in previous realist evaluations of food security programs [14] to provide an in-depth exploration of the interactions among program context, mechanisms, and outcomes. In addition, the use of qualitative methods enabled our team to be flexible and responsive to the dynamic implementation context of REDI amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

2.2. Data collection and recruitment

To gain a high-level understanding of REDI operations, virtual context-setting discussions were held with ICM program staff involved in overseeing REDI implementation throughout the Philippines. Following these discussions, virtual semi-structured interviews (n=25) were conducted with religious leaders providing emergency food aid through REDI between November 2020–January 2021. Interviews were conducted with religious leaders affiliated with the Bacolod regional base located in the province of Negros Occidental.

In addition to feasibility considerations, two additional considerations guided our decision to focus on REDI implementation in one province. First, we were aware that pandemic-related public health measures and experiences varied widely across the Philippines, which may have affected REDI implementation across provinces. Second, drawing on our previous research concerning health and social service decentralization across the Philippines [[17], [18]], we were conscious that government capacity to address pandemic-related food insecurity may differ across provinces. Thus, by focusing on one province, we aimed to conduct a more in-depth evaluation of the interactions among context, mechanisms, and outcomes surrounding REDI implementation in Negros Occidental.

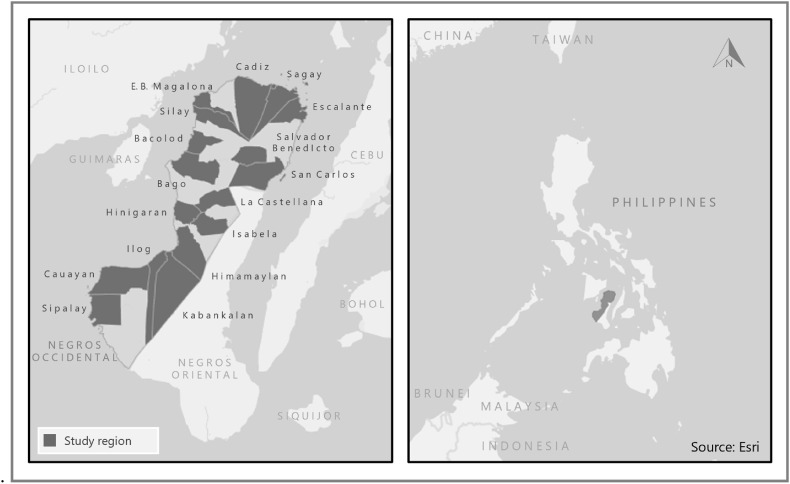

With the intention of maximizing information power [19], our team invited religious leaders to participate in the study based on their existing involvement with REDI in Negros Occidental. Further, we aimed to include a breadth of experiences with REDI by identifying religious leaders with diverse demographic characteristics from 17 different communities or cities throughout Negros Occidental (see Fig. 1 ). ICM staff then contacted these religious leaders by telephone and invited them to participate in the study.

Fig. 1.

Map of Negros Occidental, Philippines highlighting areas where religious leaders who participated in this study lived (n=17 communities or cities).

Interviews explored religious leaders’ experiences of implementing REDI and their perceived effectiveness of this intervention (see Appendix A in Supplementary Data for interview guide). For all interviews, two research team members were present, one of whom was multilingual and could provide real-time interpretation into English as needed. Interviews were conducted virtually using Skype© and in English, Hiligaynon, Cebuano, or Tagalog (or a combination of languages) based on the preference of the participant. Interviews lasted 50–120 minutes in length (average length of interviews was 77 minutes). All interviews were audio recorded and manually transcribed to facilitate analysis.

All respondents provided oral informed consent to participate. Research ethics approval was provided for this study by the University of Waterloo (ORE#42565).

2.3. Data analysis

Using a realist evaluation approach, transcripts were analyzed thematically to identify facilitators and challenges to REDI implementation [20]. Then, a second round of coding was conducted to identify contextual factors and associated mechanisms influencing implementation within and across individual participant interviews, using a constant comparative approach. QSR NVivo© software was used for organization of codes and retrieval of coded excerpts. Case classifications were applied to each transcript to facilitate querying of participant characteristics retrieved in interviews (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, household size) across codes. Regular meetings among research team members were held during analysis to discuss observations and thematic development. These collaborative meetings, in addition to the two rounds of coding, enhanced analytical rigour and credibility of findings.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of religious leaders

The majority of religious leaders (n=16; 64%) joined REDI and made their first request for emergency aid through the program during the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic. The remaining nine respondents reported that they were aware of REDI and had received training and information about the program prior to the pandemic. REDI training was mentioned across interviews, though was not reported to be a notable influence on religious leaders’ capacities to implement the program. In addition, seven respondents also described their involvement in other ICM programs prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond REDI.

Overall, religious leaders spoke very positively about REDI and the program's impact in their communities. Respondents reported requesting REDI aid a range of one to five separate times and, in total, supporting a range of 100–1400 distinct households with REDI aid. Most of these requests were made around June to July 2020 following the easing of some pandemic-related travel restrictions in Negros Occidental, but prior to all restrictions being lifted. Several respondents noted that their communities also received emergency food aid from the government; however, these religious leaders requested REDI aid to supplement this government support.

Although information on sociodemographic characteristics about each respondent were collected, religious leaders often did not explicitly connect how characteristics such as gender or age influenced facilitators or challenges of REDI implementation (see Table 1 ). When sociodemographic characteristics were discussed by respondents in relation to REDI implementation, these comments usually referenced the physicality of collecting, transporting, and distributing the boxes of food aid, which was sometimes challenging for older participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating religious leaders (n=25).

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 8 (32.0%) |

| Male | 17 (68.0%) |

| Age | |

| 30–39 years | 2 (8.0%) |

| 40–49 years | 5 (20.0%) |

| 50–59 years | 13 (52.0%) |

| 60–69 years | 4 (16.0%) |

| 70 years and older | 1 (4.0%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 18 (72.0%) |

| Single | 7 (28.0%) |

| Number of years as a religious leader | |

| 10 years or less | 3 (12.0%) |

| 11–19 years | 2 (8.0%) |

| 20–29 years | 8 (32.0%) |

| 30 years or more | 3 (12.0%) |

| Did not ask | 9 (36.0%) |

| Number of years affiliated with ICM | |

| 10 years or less | 7 (28.0%) |

| 11–19 years | 8 (32.0%) |

| 20 years or more | 10 (40.0%) |

3.2. Pathways to effective emergency food aid distribution (REDI program outcome)

Religious leaders reported shared challenges in moving centralized aid to their catchment areas and to households in need. These challenges included: transportation for pickup/delivery of aid, compounded by COVID-19 travel restrictions; determining aid eligibility and equitable distribution; and the physicality of moving boxes of emergency food. While geographic variability among respondents was noted (e.g., varying proximity to the pickup site in the city of Bacolod, degree of remoteness, and terrain to navigate for household delivery), transportation was a particular challenge for almost all religious leaders.

Pathways to mediating challenges and distributing food aid were unique to each respondent and largely shaped by individual context (e.g., personal background/experience, geographic location) and associated mechanisms. Despite these diverse pathways, common themes were identified that fundamentally shaped REDI program implementation, related to program infrastructure (e.g., administration, operations), social infrastructure (e.g., social position and networks held by religious leaders), and community infrastructure (e.g., assets leveraged and credibility of religious leaders within communities) (see Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Three main context-mechanism configurations that contributed to effective aid distribution (REDI program outcome), including (1) program infrastructure; (2) social infrastructure; and (3) community infrastructure.

3.3. Context-mechanism pathway (1): Program infrastructure

3.3.1. Administration of REDI operations

The administration of REDI operations by ICM staff was often cited as a positive influence on program implementation. Many religious leaders noted ICM's proactive communication with them, either to initiate REDI participation (P08, P13, P17, P22, P23), inform them of available supplies (P02, P11), and/or assess community needs (P04). Indeed, the general ease and efficiency of communication with ICM was highlighted by several religious leaders (P01, P20, P22). Respondents also commented on ICM's efficient coordination of REDI requests and distribution of supplies (P04, P12, P14). As one religious leader shared:

That's why we are so thankful about partnering with ICM. They give timely [aid]; we don't wait for so long. We are so happy about that … They do the job. They call us, they communicate [with] us, 'What is the need of your church, Pastor?' … and then they delivered the food packs as soon as possible (P04).

Relatedly, one respondent pointed to ICM's flexibility in giving religious leaders autonomy to determine local needs and request aid accordingly: “ICM again told us that they have available materials, so we can ask again. And if there is an area that we need to reach out to [to] give [aid], then ICM is open to that” (P22). With the exception of a few respondents who reported some technical challenges with submitting electronic aid requests (P08, P12, P14, P20), the program's mechanisms for initial registration and submitting aid requests were reportedly easy and straightforward to use. Overall, ICM's organizational competencies, as shown by their efficient communication and coordination of REDI, contributed to effective program implementation.

3.3.2. Relationships between ICM staff and religious leaders

Respondents described their positive relationships with ICM staff facilitating the program (P01, P05). For many, these relationships reflected decades (a range of 10–30 years often) of built-up social capital between ICM and participating religious leaders. As one respondent shared, positive relationship to ICM facilitated their REDI aid requests: “I find no difficulty in requesting because the relationship of the ICM staff to the pastors is good. The communication is open and there's a good partnership … with ICM here” (P15).

Relatedly, the longevity of other ICM programming in areas where REDI aid was distributed afforded the organization credibility among community members. These other programs (e.g., experiential learning opportunities for small business development, health education) were implemented prior to and alongside REDI, and respondents reported that these programs were perceived positively by community members (P02, P07, P15, P22). One religious leader accessed REDI support prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and noted it was very well-regarded by community recipients; this prior access also familiarized the respondent with REDI in advance of the pandemic and enabled them to pre-establish a system of determining aid eligibility that balanced ICM protocols and was responsive and contextualized to the needs of their community (P03).

3.4. Context-mechanism pathway (2): Social infrastructure

3.4.1. Leveraging social position and networks

In addition to being religious leaders at their specific churches, many respondents currently held other volunteer or paid roles in the community, such as a barangay chaplain, municipal guard, chairperson for another local organization, radio station volunteer, member of an evaluation committee in the barangay, and a volunteer with the Inter-Agency Task Force to monitor COVID-19 travel checkpoints.1 Through these varied roles, religious leaders were often well-known by others in the community, including those in leadership positions. As one respondent stated: “So, as a pastor, and also connected in the barangay as a chaplain, I have access … also more than 26 years already residing here in this area … I have the reputation also to keep up” (P10).

This ‘community visibility’ and the pre-existent social networks religious leaders held – outside of ICM programming – often mediated transportation barriers related to REDI implementation. In particular, many religious leaders were able to leverage assistance from their local government units (LGUs) to facilitate pickup and distribution of REDI supplies from the ICM base in Bacolod. Many respondents were approved to borrow government vehicles as community “frontliners” (P10) or received government assistance in some form to obtain a vehicle (P12). COVID-19 restrictions, such as travel checkpoints, would have reportedly impeded travel to Bacolod for religious leaders in some areas; yet, three respondents reported being part of the “lupon tagapamayapa” (P08, P13, P17) or “peace negotiators” (P13) involved in responding to COVID-19 cases in their barangay. Through holding these roles, these respondents were able to easily pass through COVID-19 travel checkpoints either on their way to the pickup site or in delivery of aid to recipients. Further, some respondents reported facilitating the entry of other ICM program staff to their community to provide further livelihood and health supports. As one religious leader explained:

Most of the people assigned [to] the checkpoint are my friends. I met them during my values commission in the barangay, in the city hall … when [ICM] go[es] to our place, they are being held in the checkpoint, interviewed, and [it was] difficult for them to pass by to go to our place. They will call me, I will also call my friend who is a policeman, if he can call the checkpoint and arrange with his co-policeman, and they did it (P17).

During a time when travel restrictions were frequently changing across communities in Negros Occidental, the strength of social relationships, in addition to the multiple roles held by some religious leaders, assisted with navigating uncertainty surrounding these restrictions. Of note, two respondents commented that other REDI religious leaders involved in REDI implementation did not hold additional roles outside of their role as a religious leader in their community. Recognizing that these individuals may experience barriers in transporting aid through COVID-19 checkpoints, the two respondents reported picking up supplies on behalf of their peers and bringing the supplies to a more proximate location for distribution (P08, P23). This recognition of diverse social positions among religious leaders, in addition to a willingness to leverage this social position to support peers, streamlined transportation of REDI supplies and facilitated REDI implementation.

3.4.2. Leveraging relationships among religious leaders

Relationships among religious leaders were highlighted as an important mechanism in facilitating the implementation of REDI. Specifically, several respondents discussed how they first learned about REDI through their peers and were also involved in encouraging other religious leaders to apply for food aid through the program (P11, P15, P23, P25). In addition, one respondent commented on how they had applied for aid through REDI on behalf of churches where they did not directly work (P25), and two respondents discussed supporting other religious leaders with the technical aspects of requesting aid (P07, P18). Further, religious leaders often drew upon social networks with one another – usually those already affiliated with ICM – to “encourage each other” (P08) as well as to facilitate distribution of supplies and mediate transportation challenges. Indeed, some respondents collated requests from other religious leaders to make a single supply request and pickup (P08, P12, P23), while other respondents reported supporting each other with household distribution (P09, P10, P13).

3.5. Context-mechanism pathway (3): Community infrastructure

3.5.1. Building on community assets

Religious leaders described a number of community assets that supported REDI implementation. Many respondents mentioned working with a team of local community members to distribute REDI aid to households in need (P05, P18, P21, P23). In particular, one respondent described how a church member had an active role in program coordination in their community and ensured that potential recipients of REDI were aware of the program (P22).

Many religious leaders also described pre-existing or parallel support programs operated by their churches (e.g., feeding programs) (P07, P12, P15, P19, P24) and the availability of church resources that mediated distribution challenges. For instance, some churches provided money for gasoline for travel to ICM's Bacolod base for aid pickup (P08) or church members offered means of transportation that would not otherwise have been available (e.g., loaning cars, motorcycles) (P21, P24). Overall, this broad community support provided to religious leaders was highlighted as a critical factor in facilitating REDI implementation.

3.5.2. Contributions of community credibility in creating an enabling environment

REDI implementation was facilitated, in part, through the credibility that religious leaders held within their communities. This credibility, which encompassed the collective trust placed in these leaders by community members and government officials, contributed to an enabling environment for REDI implementation. Importantly, the foundation for this credibility was often established within communities, outside of ICM programming, through pre-existing relationships with community members and through offering emotional and spiritual support. Because of the nature of these connections, multiple respondents referenced being able to continue visiting and counseling community members during the COVID-19 pandemic as a “spiritual front-liner” (P09), which subsequently facilitated REDI aid distribution (P03, P04, P09). As respondents shared, the trusted relationship of religious leaders to community members meant it is “easy for us to get close to them … they already know us and that's our way of extending help and care for the community” (P06), and that “it is easy for me to give that REDI help and their reception of me is good because they know me as a pastor” (P13). This pre-established “connection to the community” (P15) and having “lots of people already know me” (P14) was cited as an advantage of being a religious leader delivering aid. For a number of respondents, their knowledge of the community was also helpful in identifying households eligible for aid (P04, P07, P18, P25).

Similarly, several respondents noted how pre-existent connections to barangay officials, as chaplains or community volunteers, also secured them ‘quarantine passes’ to travel more freely in the province and locally (P05, P10, P14, P16). Even respondents without other explicit barangay roles were able, as religious leaders, to leverage assistance from their LGU or barangay health workers to retrieve supplies from Bacolod and bring them to a centralized site for recipients to pick up (P06); to help unload (P12); and/or to assist with distributing directly to recipients (P01, P07, P08, P10, P25). This assistance was noted as particularly helpful for those contexts with stricter COVID-19 protocols (P11, P12). In these areas, the barangay captain took a lead role in coordinating distribution. For instance, as one religious leader shared:

There’s a barangay that’s in lockdown … so we can’t go in there. So we’re just in the checkpoint. But we’re really grateful that the barangay captain is really helpful, and he’s the one facilitating. So, the people on the [eligibility] list were just being called and went to the checkpoint and that’s where they get the goods from REDI Help (P11).

Other religious leaders drew on LGU connections or prior career backgrounds to help mediate the challenges of determining aid eligibility and distributing REDI aid equitably. For some respondents, their LGU assisted by generating a list of households eligible for aid according to income (P09, P11, P19). Others had experience coordinating aid with other organizations to support community members both in and outside of the church (P02, P03). One of these religious leaders noted that her 19-year community development background helped her discern how to distribute aid equitably (P03).

Overall, the credibility held by religious leaders within their communities, combined with their awareness and understanding of community-level dynamics and needs, facilitated REDI implementation. Importantly, most religious leaders worked with a diverse network of actors within and beyond their communities to not only transport and distribute aid, but also to prioritize equity considerations in aid distribution amid the ongoing pandemic.

4. Discussion

Drawing on the experiences and insights of religious leaders engaged in REDI implementation, this study identified the broad facilitators and barriers to addressing emergency food insecurity among households experiencing extreme poverty during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, this study explored how different context-mechanism configurations shaped REDI implementation across Negros Occidental (see Table 2 ). Specifically, each respondent leveraged a unique combination of program, social, and community infrastructures to accomplish various REDI tasks (e.g., identifying needs, requesting aid, transporting aid, distributing aid). Across findings, this study highlights: 1) the important contributions and unique positionality of religious leaders in humanitarian relief efforts; and 2) how organizational structures can provide an implementation framework to guide local decision making and collaboration amid a dynamic humanitarian crisis.

Table 2.

Challenges to REDI implementation, as well as associated context-mechanism configurations that mediated challenges and facilitated implementation.

| Challenges | Context-Mechanism pathways to mediate challenges | |

|---|---|---|

| Transportation for pick-up and/or delivery of aid (e.g., COVID-19 travel restrictions) | Program infrastructure → Administration: | ICM's efficient coordination of aid requests & distribution of supplies. Proactive communication to inform leaders of available supplies. |

| Social infrastructure → Social position/networks of leaders: | Obtained local government assistance with aid distribution. Ability to pass through COVID-19 checkpoints. | |

| Social infrastructure → Relationships among leaders: | Collated aid requests and aid pickup; supported each other with aid distribution. | |

| Community infrastructure → Building on community assets: | Available resources for travel (e.g. gasoline money, loaning of cars). | |

| Community infrastructure → Community credibility/enabling environment: | Able to continue providing support in COVID-19 as religious leaders (therefore provide aid too). ‘Quarantine passes' to travel freely. | |

| Determining aid eligibility & equitable distribution | Program infrastructure → Administration: | ICM's flexibility to give religious leaders autonomy to determine local needs and request aid accordingly. |

| Program infrastructure → Relationships between ICM staff & REDI leaders: | ICM's credibility among communities. Leaders could balance ICM aid protocols with local needs. | |

| Community infrastructure → Community credibility/enabling environment: | Leaders' knowledge of who is eligible for aid. Local government unit assistance in determining aid eligibility. Leaders' prior background in aid. | |

| Physicality of moving food boxes | Community infrastructure → Building on community assets: | Team of people to distribute aid within the community. |

| Technical challenges with electronic aid requests | Program infrastructure → Administration: | ICM's mechanism for submitting aid requests is overall easy and straightforward to use (challenges were reportedly the exception). |

| Social infrastructure → Relationships among leaders: | Supported one another with technical aspects of aid requests. | |

4.1. The contributions of religious leaders amid dynamic humanitarian crises

Across respondents included in this study, the positionality as a religious leader was consistently highlighted as critical to shaping all aspects of REDI implementation. Indeed, in our study, the role of religious leader appeared more important than other demographic factors (e.g., age, gender) in shaping experiences with REDI implementation among respondents. However, distinctions in experiences with REDI implementation were noted between respondents who only held the position of religious leader and respondents who held the position of religious leader in addition to other roles (e.g., government official, volunteer outside of immediate faith community). Specifically, respondents who held other roles in addition to the role of religious leader appeared to have a wider social network to draw on to effectively implement REDI. Thus, in evaluating the contributions of religious leaders in humanitarian relief efforts, it is important to interrogate how diverse roles, positionalities, and networks held by these individuals may differentially shape experiences with the implementation of programs aimed at addressing acute needs amid crises.

Relatedly, respondents in this study did not implement REDI in isolation, but instead were members of broader community-based networks that included other religious leaders and community members. Although religious leaders were identified by ICM as the key implementers of REDI, many respondents relied on their faith communities and networks to accomplish various tasks associated with REDI implementation. Indeed, the potential of faith communities to contribute to disaster reduction and community resilience amid humanitarian crises has been previously highlighted as an area for further research and practice [[21], [22], [23]]. This study provides insight into how religious leaders worked in concert with their faith communities and networks to strategically leverage human, physical, and financial resources to implement REDI and address emergency food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.2. The contributions of an organizational implementation framework to guide community-based humanitarian relief efforts and collaboration

All respondents in this study were involved in the implementation of a specific program administered by one NGO (ICM) to address emergency food insecurity among households experiencing extreme poverty. The decision to participate in REDI implementation was often guided by previous positive experiences with ICM's broader community-based work or previous experience with REDI to address emergency needs following localized disasters (e.g., floods, fires). This previous working relationship with ICM facilitated the building of trust and social capital between ICM and religious leaders, which was critical to REDI implementation amid the uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic. This finding underscores the value and importance of NGOs cultivating trust-based community networks prior to disaster events to enhance preparedness and to ensure immediate mobilization of resources through these networks when crises occur [[24], [25], [26]]. Further, fostering these trust-based community networks, with the intention of enhancing community resilience, can be viewed as a tangible approach to mainstreaming disaster risk reduction principles among NGOs where disaster risk reduction falls outside their primary activities [26].

The decision to participate in REDI implementation and collaborate with ICM provided some overarching operational structure to the humanitarian relief efforts of respondents, which subsequently shaped their experiences in addressing emergency food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, following the receipt of aid requests, ICM ensured food aid was available at a central location for pickup, in addition to providing training and technical support for religious leaders. Despite this operational structure, there was also recognition among ICM and religious leaders that REDI implementation needed to be contextualized to each community to ensure a responsive and flexible approach amid the dynamic nature of the pandemic. This approach was particularly effective when navigating transportation challenges and community-specific travel restrictions, with respondents building on guidance from ICM to leverage a unique combination of social networks and resources to transport and distribute aid.

While transportation challenges were often remedied through collaborative and creative problem solving, determining eligibility for food aid was described as a more complex challenge among respondents, highlighting the difficulty of balancing organizational guidelines and meeting immediate needs in the context of disaster response [27]. Indeed, ICM worked to provide eligibility guidelines alongside empowering religious leaders to be responsive to local realities; however, the overwhelming need in some communities contributed to heterogeneity across respondents in terms of decision-making processes to determine aid eligibility. Overall, these diverse experiences among respondents highlight the complexity and contextual nature of operationalizing equity in disaster response and aid distribution [28]. Further, these insights offer an opportunity for reflection among NGOs involved in disaster risk reduction on how to prioritize equity at an organizational level, while empowering and supporting individuals on the front lines of disaster response.

NGO-led disaster response and humanitarian relief is frequently viewed as necessary to address gaps in state-led disaster response in resource-constrained settings [[29], [30], [31], [32]]. However, this study provides a more nuanced account of how ICM, religious leaders, and various levels of government collaborated to address emergency food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study complements recent research exploring localized disaster response in the Philippines and how local government units might enhance disaster preparedness [33,34]. Importantly, ICM provided guidance to religious leaders involved in REDI to partner with local governments to facilitate program implementation. These partnerships were especially important in a pandemic context, where travel restrictions and checkpoints needed to be navigated to transport and distribute food aid. Further, several religious leaders held positions adjacent to or within local governments, which provided opportunities to leverage government resources to facilitate REDI implementation. Despite the optimism among respondents surrounding this collaboration, previous research in the Philippines has critically examined NGO-government collaboration in disaster response, and argued that this collaboration may undermine more transformative disaster preparedness and response [29,35]. In this study, NGO-government collaboration, mediated by religious leaders, was effective in facilitating the distribution of food aid during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further research is needed to determine the extent to which this collaboration enhanced capacity among actors to prepare for and respond to subsequent crises.

4.3. Limitations

This study focused on the experiences of religious leaders involved in REDI implementation, which limited insights from other actors either directly or indirectly connected to REDI (e.g., recipients of REDI aid, broader faith communities, government officials). The inclusion of these actors in the study may have provided alternative perspectives on the facilitators and challenges of REDI implementation. In addition, due to the complexity of pandemic-related travel restrictions and public health measures across jurisdictions, as well as the decentralization of health and social service provision, we decided to only evaluate REDI implementation in one province (Negros Occidental) to facilitate a more in-depth exploration of other factors (e.g., beyond pandemic-related restrictions and public health measures) that shaped REDI implementation. The inclusion of other provinces where REDI was operational during the COVID-19 pandemic may have revealed additional challenges, as well as pathways through which REDI was successfully implemented.

5. Conclusion

This study identified three context-mechanism configurations that facilitated the effective implementation of REDI by religious leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, program infrastructure established by ICM ensured that participation in REDI implementation was both technically and relationally accessible for religious leaders. Second, social infrastructure held by religious leaders meant that respondents were able to leverage a range of social networks and relationships to accomplish REDI tasks. Third, community infrastructure provided key assets as well as an enabling environment where effective REDI implementation could occur. Across these context-mechanism configurations, REDI implementation was further made possible through the unique positionality of religious leaders within and beyond their geographic and faith communities. In addition, the organizational implementation framework created by ICM provided structure and guidance for the community-based humanitarian relief efforts of religious leaders, while also empowering religious leaders to adapt and respond to on-the-ground realities. Indeed, well-structured yet locally-responsive implementation guidelines, coupled with trust-based community networks, can aid disaster-response organizations in effective community-based response.

Overall, this study highlights the important role of religious leaders in addressing emergency food insecurity among resource-constrained communities in the Philippines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disaster-response organizations (e.g., NGOs, governments) would benefit from regularly considering religious leaders as effective actors in community-based response efforts and expanding their involvements. In addition, this study describes how religious leaders collaborate with other actors, such as NGOs and local governments, to provide community-based disaster response and humanitarian relief. Given broader calls for collaboration within community-based disaster response and humanitarian relief, this study provides insight into how intersectoral collaboration can be facilitated through an NGO-led disaster response network. Further research might explore the extent to which intersectoral collaboration enhances disaster preparedness and builds capacity for future community-based disaster response among the actors involved.

Funding

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (892-2021-1004).

Declaration of competing interest

Authors (DSJ, DJG, LLL) receive remuneration from International Care Ministries (ICM). The authors have been provided academic freedom by ICM to publish both negative and positive results. Authors WD, LJB, and SS have no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

A barangay is the smallest administrative division in the Philippines.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103545.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

The data that has been used is confidential.

References

- 1.Béné C. Resilience of local food systems and links to food security–A review of some important concepts in the context of COVID-19 and other shocks. Food Secur. 2020;12(4):805–822. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01076-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zurayk R. Pandemic and food security: a view from the Global South. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development. 2020;9(3):17–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu Y., Li R. Rebuilding resilient homeland: an NGO-led post-Lushan earthquake experimental reconstruction program. Nat. Hazards. 2020;104(1):853–882. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodd W., Brubacher L.J., Kipp A., Wyngaarden S., Haldane V., Ferrolino H., Wei X. Navigating fear and care: the lived experiences of community-based health actors in the Philippines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lunn J. The role of religion, spirituality and faith in development: a critical theory approach. Third World Q. 2009;30(5):937–951. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheikhi R.A., Seyedin H., Qanizadeh G., Jahangiri K. Role of religious institutions in disaster risk management: a systematic review. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021;15(2):239–254. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2019.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gianisa A., Le De L. The role of religious beliefs and practices in disaster: the case study of 2009 earthquake in Padang City, Indonesia. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2017;27(1):74–86. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joakim E.P., White R.S. Exploring the impact of religious beliefs, leadership, and networks on response and recovery of disaster-affected populations: a case study from Indonesia. J. Contemp. Relig. 2015;30(2):193–212. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sufri S., Dwirahmadi F., Phung D., Rutherford S. A systematic review of community engagement (CE) in disaster early warning systems (EWSs) Progress in Disaster Science. 2020;5 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheema A.R., Scheyvens R., Glavovic B., Imran M. Unnoticed but important: revealing the hidden contribution of community-based religious institution of the mosque in disasters. Nat. Hazards. 2014;71(3):2207–2229. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau L.L., Hung N., Go D.J., Choi M., Dodd W., Wei X. Dramatic increases in knowledge, attitudes and practices of COVID-19 observed among low-income households in the Philippines: a repeated cross-sectional study in 2020. J. Glob. Health. 2022;12 doi: 10.7189/jogh.12.05015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luu K., Brubacher L.J., Lau L.L., Liu J.A., Dodd W. Exploring the role of social networks in facilitating health service access among low-income women in the Philippines: a qualitative study. Health Serv. Insights. 2022;15 doi: 10.1177/11786329211068916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau L.L., Dodd W., Qu H.L., Cole D.C. Exploring trust in religious leaders and institutions as a mechanism for improving retention in child malnutrition interventions in the Philippines: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam S., Dodd W., Wyngaarden S., Skinner K., Papadopoulos A., Harper S.L. How and why are Theory of Change and Realist Evaluation used in food security contexts? A scoping review. Eval. Progr. Plann. 2021;89 doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2021.102008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rycroft-Malone J., McCormack B., Hutchinson A.M., DeCorby K., Bucknall T.K., Kent B., Titler M. Realist synthesis: illustrating the method for implementation research. Implement. Sci. 2012;7(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pawson R., Tilley N., Tilley N. Sage Publications Ltd; 1997. Realistic Evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsunaga Y., Yamauchi N., Okuyama N. What determines the size of the nonprofit sector?: a cross-country analysis of the government failure theory. Voluntas Int. J. Voluntary Nonprofit Organ. 2010;21(2):180–201. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gumasing M.J.J., Prasetyo Y.T., Ong A.K.S., Nadlifatin R. Determination of factors affecting the response efficacy of Filipinos under Typhoon Conson 2021 (Jolina): an extended protection motivation theory approach. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2022;70 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malterud K., Siersma V.D., Guassora A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ager J., Fiddian-Qasmiyeh E., Ager A. Local faith communities and the promotion of resilience in contexts of humanitarian crisis. J. Refug. Stud. 2015;28(2):202–221. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGregor A. Geographies of religion and development: rebuilding sacred spaces in Aceh, Indonesia, after the tsunami. Environ. Plann. 2010;42(3):729–746. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wisner B. Untapped potential of the world's religious communities for disaster reduction in an age of accelerated climate change: an epilogue & prologue. Religion. 2010;40(2):128–131. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henley L.J., Henley Z.A., Hay K., Chhay Y., Pheun S. Social work in the time of COVID-19: a case study from the global south. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2021;51(5):1605–1622. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcab100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Izumi T., Shaw R. In: Community-based Disaster Risk Reduction. Shaw R., editor. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; Bingley: 2012. Role of NGOs in community-based disaster risk reduction; pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seddiky M.A., Giggins H., Gajendran T. International principles of disaster risk reduction informing NGOs strategies for community based DRR mainstreaming: the Bangladesh context. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2020;48 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scolobig A., Prior T., Schröter D., Jörin J., Patt A. Towards people-centred approaches for effective disaster risk management: balancing rhetoric with reality. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2015;12:202–212. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eadie P., Su Y. Post-disaster social capital: trust, equity, bayanihan and Typhoon Yolanda. Disaster Prev. Manag.: Int. J. 2018;27:334–345. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bankoff G., Hilhorst D. The politics of risk in the Philippines: comparing state and NGO perceptions of disaster management. Disasters. 2009;33(4):686–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kita S.M. "Government doesn’t have the muscle”: state, NGOs, local politics, and disaster risk governance in Malawi. Risk Hazards Crisis Publ. Pol. 2017;8(3):244–267. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurata Y.B., Prasetyo Y.T., Ong A.K.S., Cahigas M.M.L., Robas K.P.E., Nadlifatin R.…Thana K. Predicting factors influencing intention to donate for super Typhoon Odette victims: a structural equation model forest classifier approach. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2022;81 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Espia J.C.P., Fernandez P., Jr. Insiders and outsiders: local government and NGO engagement in disaster response in Guimaras, Philippines. Disasters. 2015;39(1):51–68. doi: 10.1111/disa.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dodd W., Kipp A., Bustos M., McNeil A., Little M., Lau L.L. Humanitarian food security interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic in low-and middle-income countries: a review of actions among non-state actors. Nutrients. 2021;13(7):2333. doi: 10.3390/nu13072333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dodd W., Kipp A., Lau L.L., Little M., Conchada M.I., Sobreviñas A., Tiongco M. Limits to transformational potential: analysing entitlement and agency within a conditional cash transfer program in the Philippines. Soc. Pol. Soc. 2022:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dodd W., Kipp A., Nicholson B., Lau L.L., Little M., Walley J., Wei X. Governance of community health worker programs in a decentralized health system: a qualitative study in the Philippines. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021;21(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06452-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.