Abstract

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is associated with irregular menstrual cycles, hyperandrogenemia, and obesity. It is currently accepted that women with PCOS are also at risk for endometriosis, but the effect of androgen and obesity on endometriosis has been underexplored. The goal of this study was to determine how testosterone (T) and an obesogenic diet impact the progression of endometriosis in a nonhuman primate (NHP) model. Female rhesus macaques were treated with T (serum levels approximately 1.35 ng/ml), Western-style diet (WSD; 36% of calories from fat compared to 16% in standard monkey chow) or the combination (T + WSD) at the time of menarche as part of a longitudinal study for ~7 years. Severity of endometriosis was determined based on American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) revised criteria, and staged 1–4. Stages 1 and 2 were associated with extent of abdominal adhesions, while stages 3 and 4 were associated with presence of chocolate cysts. The combined treatment of T + WSD resulted in earlier onset of endometriosis and more severe types associated with large chocolate cysts compared to all other treatments. There was a strong correlation between glucose clearance, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and total percentage of body fat with presence of cysts, indicating possible indirect contribution of hyperandrogenemia via metabolic dysfunction. An RNA-seq analysis of omental adipose tissue revealed significant impacts on a number of inflammatory signaling pathways. The interactions between obesity, hyperandrogenemia, and abdominal inflammation deserve additional investigation in NHP model species.

Keywords: endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, testosterone, obesity, metabolism

This nonhuman primate study demonstrates metabolic disturbances associated with exposure to androgens and an obesogenic diet accelerates onset of cystic endometriosis.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a disorder of women and menstruating nonhuman primates (NHPs) where tissues histologically similar to the endometrium occur at sites outside the uterus. Factors associated with endometriosis include a history of infertility [1], dysmenorrhea, and pelvic pain [2]. A predominant theory, the Sampson hypothesis [3], is that endometriosis may occur following retrograde menstruation, in which endometrium travels outside of the fallopian tubes and establishes outside of the uterus. Retrograde menstruation has been observed at higher rates in both women and NHPs with spontaneous endometriosis, indicating similar potential mechanisms between species [4, 5]. Rhesus macaques develop spontaneous endometriosis [6] at rates comparable to those observed in women [7] and similar to women show increased prevalence following abdominal surgical procedures [8]. Other factors modulating endometriosis severity remain relatively unknown.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common causes of infertility in women [9]. It is often associated with infertility, irregular menstrual cycles, hyperandrogenemia, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction. An increased risk for endometriosis for women with PCOS is reported clinically, especially those with infertility [10]; however, the etiology of endometriosis in PCOS women is unknown. The paradox of endometriosis and PCOS is many women with ongoing infertility have high body mass index (BMI), which is thought to be protective [11]. Several of those studies evaluated data from women of European descent, while other studies in women of different ethnicities have reported conflicting data for endometriosis risk and BMI [12]. Our research group has conducted a longitudinal study to assess the effects of two well-known phenotypes of PCOS, mildly elevated testosterone (T) and an obesogenic “Western-style diet” (WSD), and determined the impact of these treatments alone and in combination on reproductive and metabolic function in a primate species (rhesus macaques, Macaca mulatta) [13–15]. We observed altered ovarian and uterine function in T and T + WSD-treated rhesus females, including delayed and reduced fertility especially in the T + WSD cohort which had a high prevalence of obesity and metabolic dysfunction [13]. Interestingly, during this multi-year study we observed a high prevalence of endometriosis, particularly in the T + WSD cohort which had a higher prevalence of metabolic dysfunction than other treatment groups. [16]. Endometrial progesterone resistance is associated with endometriosis in humans [17, 18] and NHPs, including the baboon [19]. Hyperandrogenemia drove signs of progesterone resistance in the endometrium of the T and T + WSD treated females, as demonstrated by reduced progesterone-induced attenuation of estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) and the classical progesterone receptor (PGR) in endometrial glands as compared to non-T-treated groups [14], which could have pre-disposed the NHP females in this PCOS model to develop endometriosis. Signs of progesterone resistance developed prior to endometriosis diagnosis, indicating this trait may develop prior to the presence of endometriotic lesions. However, because other cohorts also developed endometriosis, a systemic evaluation of onset and severity of endometriosis in these females is needed to determine whether hyperandrogenemia, obesity, or the combination may play a role in onset and/or progression of this disease state in primates. Some have proposed that the local inflammatory abdominal milieu may predispose women to development of endometriosis regardless of BMI—this question can be addressed in this well-characterized NHP model.

The current study sought to characterize onset and progression of endometriosis in our experimental NHP cohort, and compare metabolic function of those with and without cystic disease to provide insights into the link between endometriosis, hyperandrogenemia, and metabolic dysfunction. To ascertain if there is a correlation between abdominal inflammatory milieu and endometriosis severity, a subanalysis was performed on the omental adipose transcriptome, contrasting females with and without cystic disease. It was hypothesized that animals with hyperandrogenemia and WSD (T + WSD) would have an increased inflammatory state in the abdominal adipose tissue, which may accelerate onset of severe endometriosis in the pelvic cavity.

Methods

Ethics

All animal procedures were approved by the Oregon Health & Science University, Oregon National Primate Research Center (ONPRC) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and comply with the Animal Welfare Act and the APA Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in the Care and Use of Nonhuman Animals in Research.

Treatments

Female rhesus macaques, aged roughly 2.5–3.5 years (n = 39), were exposed to treatments as previously described [15]: females were subjected to mildly elevated levels of testosterone (~5-fold, T) or were treated with vehicle (cholesterol) by use of subcutaneous silastic implants. These treatments were then divided into two additional cohorts by diet, wherein females consumed a standard, healthy macaque chow diet, or a WSD with an increased number of calories from animal fat. This resulted in a 2 × 2 factorial arrangement of treatment groups of C (cholesterol, chow; n = 10), T (T, chow; n = 9), WSD (cholesterol, WSD; n = 10), and T + WSD (T, WSD; n = 10). Serum T levels were checked weekly as previously described [15], and implants replaced when necessary; during the first 3 years the average serum levels were 1.35 ng/ml in T-treated groups compared to 0.27 ng/ml in the cholesterol treated groups [15]. At the time of the current report, the animals were on these current treatments for 7 years. Females were monitored for onset and extent of endometriosis by trained ONPRC Division of Comparative Medicine’s (DCM) veterinary staff. Abdominal cavities were examined during annual laparoscopic procedures, and abdominal ultrasound was performed twice yearly by experienced staff (CVB and HS). Observations were used to stage endometriosis as previously published [16].

Surgeries

All females underwent laparoscopic procedures involving yearly collection of omental adipose tissue and liver biopsies, as well as ovarian follicle aspiration (single and multiple follicles), and uterine biopsies. Animals underwent at least one and at most two Caesarian section(s) in the third trimester of pregnancy [13]. All females had at least one surgical procedure involving the reproductive tract prior to diagnosis.

Endometriosis staging

Staging for endometriosis was done similarly to the ASRM revised criteria for endometriosis, modified for rhesus females [16]. Briefly, minor abdominal adhesions were considered stage 1, extensive adhesions (but no endometriotic cysts) were considered stage 2, presence of chocolate cysts <1 cm were considered stage 3, and presence of multiple large >1 cm chocolate cysts surrounding reproductive tract (usually accompanied by extensive adhesions) were considered stage 4. Laparoscopic and ultrasound images of reproductive tracts with these characteristics were published previously (Supplemental Figure 1 in ref. [16]).

Longitudinal analyses

Because of the documented connection in women between abdominal surgery and endometriosis risk [8], all staging was based on time from first abdominal surgical procedure. The surgeon’s description of intrabdominal adhesions and lesions during laparoscopic examination, and physical evaluation (abdominal/uterine palpation), ultrasound images, and necropsy reports were used for disease staging at multiple time points throughout the study. Time of stage IV diagnosis was considered the final endpoint, unless the female was necropsied for an unrelated ailment. Females underwent necropsy if at any point in the study ONPRC DCM Veterinarians determined endometriosis could no longer be managed by palliative care.

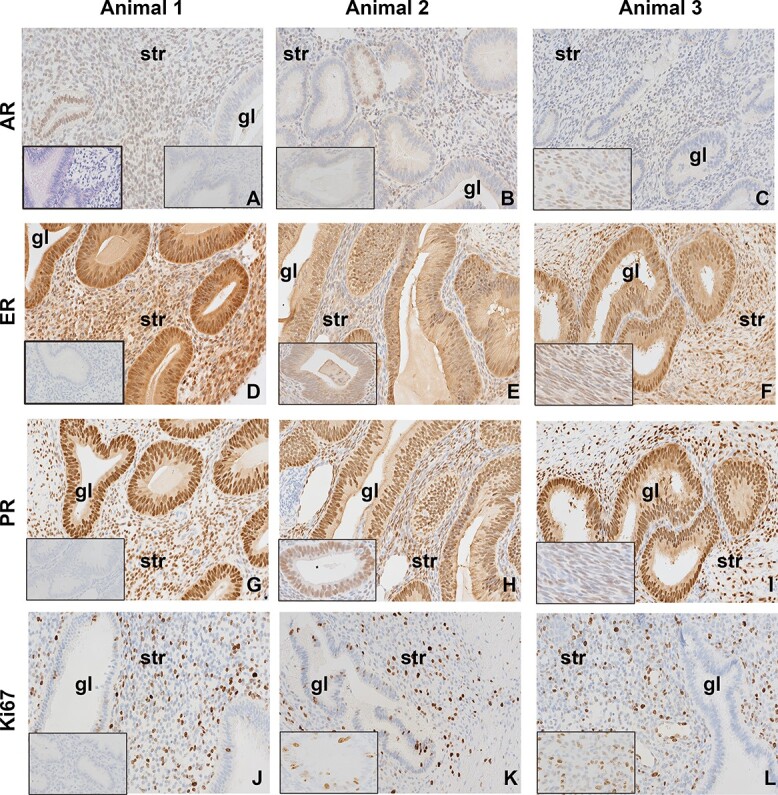

Histologic analyses of endometriotic lesions

Biopsies of endometriotic lesions recovered from 4 T + WSD-treated females with advanced endometriosis at time of necropsy were processed for paraffin embedding as previously described [14]. Paraffin tissue sections (5 μm) were placed on glass slides and analyzed for ESR1 (catalog #MS-354-P, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; final concentration 1 μg/ml; Research Resource Identifier (RRID) #AB_61341), PGR (catalog #Ab15509, Abcam, Cambridge, UK; final concentration 1 μg/ml; RRID # AB_301918), androgen receptor (AR; BioGenex, Fremont, CA, USA; final dilution 1:50 RRID # AB_2687514), and marker of proliferation Ki-67 (MKI67; Abcam; final dilution 1:100; RRID # AB_302459) using established methods [14]. Expression of each target protein was visualized with DAB staining (ABC kit, Vector Laboratories, Inc. Burlingame, CA, USA; RRID # AB_2336827). Sections were lightly counter-stained with Meyer’s hematoxylin to identify negatively-staining nuclei in endometriotic lesion.

Metabolic status

During treatment animals underwent yearly metabolic assessments according to previously published protocols [14, 15, 20]. Metabolic parameters such as BMI, % body fat, and HOMA-IR (insulin sensitivity index) were calculated based on established protocols in NHPs [21]. Metabolic status (BMI, measurements of insulin sensitivity) was compared to staging to determine impact of onset of symptoms.

Statistics on discrete and longitudinal variables

For each stage of endometriosis, time to disease events were analyzed using nonparametric k-sample test analyses of the probability of an individual female remaining disease-free throughout the experimental time interval. This was accomplished by using the Life Test procedure of SAS Enterprise Guide (Version 9.4, SAS Institute, Carey, NC, USA) with Log-rank test adjustment for multiple comparisons by treatment group (C, T, WSD, T + WSD). Main effects analyzed included steroid exposure (denoted T), diet consumption (denoted WSD), and interactions between combined T and WSD treatment. Females were excluded (censored) from the analysis if they were necropsied for circumstances unrelated to cystic stages of endometriosis, and stages were confirmed in these females at time of necropsy. To determine if metabolic function of females was associated with accelerated time to diagnosis of endometriosis stages 3 and 4, Pearson’s bias-adjusted correlation statistics between time to disease state and metabolic function by treatment group (as well as testing main effects of T, WSD, and interaction of T and WSD) were generated by the generalized linear model function of SAS. Pairwise comparisons between treatment groups were analyzed by least squared means function of SAS, using Tukey–Kramer adjustment for multiple comparisons. Effects of steroid exposure (T), diet (WSD), and interactions, as well as pairwise differences between individual treatment groups, were considered significant if P ≤ 0.05, while data with P = 0.06–0.09 were considered to trend toward differences.

RNA-seq analyses of omental transcriptome

Omental adipose biopsies obtained from discrete cohorts of treated females (n = 10 C, 7 T, 7 WSD, and 4 T + WSD) in year 7 described above were submitted to the OHSU Gene Profiling Shared Resource for isolation of total RNA. Samples were randomized prior to isolation. A 50–100 mg piece was excised with a clean razor from each sample while on dry ice. This was then added to a 2 ml tube with a stainless-steel bead and 1 ml of QIAzol. The tissue then went through two rounds of bead bashing to homogenize the sample. Chloroform (200 μl) was added, vortexed, and then spun down to create a separation between the aqueous and organic phases. About 600 μl of the upper aqueous phase was then processed in one batch by Qiagen RNeasy Mini Adipose Tissue Kit utilizing two QIAcube sample processing robots. RNA was eluted in 50 μl of nuclease-free water. RNA concentration and yields were determined by UV absorption (using a Nanodrop One spectrophotometer), and sample quality was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and RNA 6000 Nano/Pico Chip (run with the Eukaryotic Total RNA Nano program). Average RNA concentration was 93.6 ng/ml, and average RNA Integrity Number (RIN) score was 8.3. No biopsy yielded RNA with RIN values <7, and all samples were advanced to library formation for sequencing.

RNA libraries were prepared by the OHSU Massively Parallel Sequencing Shared Resource (MPSSR) using a TruSeq Stranded mRNA library prep kit with rRNA depletion (Illumina). Library quality was verified by TapeStation System (Agilent) and real-time PCR using StepOnePlus Real Time PCR System (ABI). Paired-end sequencing (100 cycles) was performed by the MPSSR using a NovaSeq platform (Illumina).

Differential gene expression (DGE) analyses were performed by the ONPRC Bioinformatics and Biostatistics Core similar to previous sequencing projects of tissues obtained from these rhesus monkeys [16, 20]. After sequences were assessed for quality and trimmed to remove any remaining Illumina adaptor sequences, they were aligned to the latest version of the rhesus genome (mmul10, Ensembl release 100).

Details of the data analysis pipelines in similar tissues obtained from these macaque females were published previously [16, 20]. There were 35 432 genes from 28 libraries identified in the raw analysis. Three samples (1 T and 2 WSD) were determined to be outliers due to poor library quality and excluded from further analyses. After filtering out genes with extreme low counts [defined as no more than 1 count per million (CPM) in a sample] in 25 libraries, 14 788 genes were retained for further analyses. Briefly, after filtering and trimming raw gene level counts were transformed to log CPM with associated observational precision weights using the voom method. Endometriosis status of female at time of biopsy was determined and females without evidence of cysts (stages 0–2, n = 13) were compared to females with cysts (stages 3 and 4, n = 12) for DGE by limma with empirical Bayes moderation. An additional DGE analysis accommodating the 2 × 2 factorial design between diet and steroid was also analyzed separately (n = 10 C, 6 T, 5 WSD, and 4 T + WSD). Because of expected large within-group variation, and to provide mechanistic insight into the underlying biology, DGE genes are defined as genes with raw P <0.05 without multiple testing adjustment. Pathway analyses were then performed with Ingenuity Pathway Analyses (IPA) software, and gene pathways were also mapped with PANTHER (16.0), similar to previous studies [16].

Results

We observed deep, infiltrating endometriosis in females diagnosed with stages 3 and 4 disease, including tissues recovered from necropsies. Endometriotic lesions of a subset of T + WSD females with advanced disease obtained following necropsy possessed recognizable glandular-like structures (Figure 1). Expression of AR was variable with a few gland-like structures in each lesion possessing cells with AR expression localized primarily to the nuclei of cells (Figure 1 A–C, gl). However, most stromal-like cells do express AR protein (str). Intense staining for ESR1 and PGR were noted in these gland-like structures, while intensity of staining in stromal-like cells varied by lesion/female (Figure 1D–I). Many MKI67-expressing cells were found throughout the stromal-like tissues (Ki67, Figure 1 J–L), and a few of the glandular-like structures possessed a small number of cells with MKI67 expression.

Figure 1.

Rhesus late-stage endometriotic lesions from three separate T + WSD-treated females (Animal 1, Animal 2, Animal 3) show glandular (gl)-like and stromal (str)-like characteristics and expected expression of proteins associated with endometrial function. Expression of androgen receptor (AR, A–C), estrogen receptor α (ESR1, D–F), progesterone receptor (PGR, G–I), and marker of proliferation ki-67 (MKI67/Ki67, J–L) in endometriotic lesions. All tissues were collected at necropsy for late-stage disease (stage 4). Positive protein expression is denoted by brown staining, while blue counter-stained nuclei are negative for these proteins. All images were visualized at 20X magnification with the same brightness. Inset image to left in panel A shows hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of glandular-like morphology. Inset images in right of panel A, and left in panels D, G, and J show negative IgG controls. Inset images in left of panels B, E, H and K show increased magnification images of gl-like structures. Inset images in left of panels C, F, I and L show increased magnification images of str-like cells.

The proportion of females within each disease stage by treatment group as well as disease stage at end of 7 years of treatment was initially analyzed by nonparametric Chi-squared analyses (two-way generalized linear model function of SAS) to determine if any of the treatments increased the severity of endometriosis, especially those associated with cystic disease (stages 3 and 4). While an overall trend was noted for consumption of the WSD on disease severity at the end of 7 years of treatment (P = 0.068, Table 1), this appears to be primarily driven by the T + WSD cohort and is especially striking when compared to control females. After 7 years of treatment, 70% of females within the control cohort had yet to progress to stage 4 endometriosis, 60% had yet to progress to stage 3, and 10% remained free of severe adhesions associated with stage 2 diagnosis (Table 1). This is in contrast to females in the T + WSD cohort, where only 20% were yet to be diagnosed with stage 4, 10% had not progressed to stage 3, but all females had received a diagnosis of stage 2/severe adhesions during the 7-year study interval.

Table 1.

Prevalence of endometriosis in rhesus females

| Average stage after 7 years of treatment | Total number of affected females in each diagnostic stagea |

Average days to diagnosis (mean ± SEM)b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | |

| C (n = 10) | 2.6 ± 3.2 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 1770 ± 151 | 2177 ± 93a | 2445 ± 81a | 2547 ± 44a |

| T (n = 9) | 2.7 ± 3.4 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 1857 ± 166 | 2183 ± 117a | 2278 ± 132a,b,* | 2395 ± 110a,b |

| WSD (n = 10) | 2.9 ± 3.2 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 1704 ± 74 | 1861 ± 124a,b | 2228 ± 120a,b | 2356 ± 104a,b |

| T + WSD (n = 10) | 3.7 ± 3.2 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 1599 ± 106 | 1627 ± 118b | 1802 ± 116b,** | 2046 ± 135b |

aFemales evaluated longitudinally; therefore, this depicts total number of diagnoses per group for each stage.

bCommon mean square error.

Differences between uppercase letters (A vs B) within columns/stage indicate differences between treatment groups, P < 0.05.

* vs** denotes P < 0.06.

Since there appeared to be a trend toward greater disease severity in the T + WSD cohort, we then analyzed females by time to diagnosis for each disease stage (survival curves Supplemental Figure 1, Table 1). The T + WSD cohort presented with onset of stage 2, 3, and 4 disease more rapidly than similarly diagnosed controls (Sidak bias-adjusted P = 0.013, 0.004, and 0.03, respectively, Table 1, Supplemental Figure 1). This cohort also progressed more rapidly than T-only treated females diagnosed with stage 2 (Sidak P = 0.03) and tended to progress to stage 3 faster (Sidak P = 0.07, Raw P = 0.01; Table 1). No differences by cohort were detected in females in time to stage 1 (minor adhesions, Supplemental Figure 1D). Minimum time and maximum time to diagnoses are also reported by treatment group, and reflect these patterns (Supplemental Table 1A). Finally, an analysis was performed to determine the number of abdominal procedures to diagnosis of each stage of endometriosis (Supplemental Figure 2). The T + WSD treated females developed stage 2 disease after fewer number of procedures compared to control females (P < 0.01; Supplemental Figure 2C). Prevalence of endometriosis and severity was not impacted by previous pregnancies in the study interval (Supplemental Table 1B).

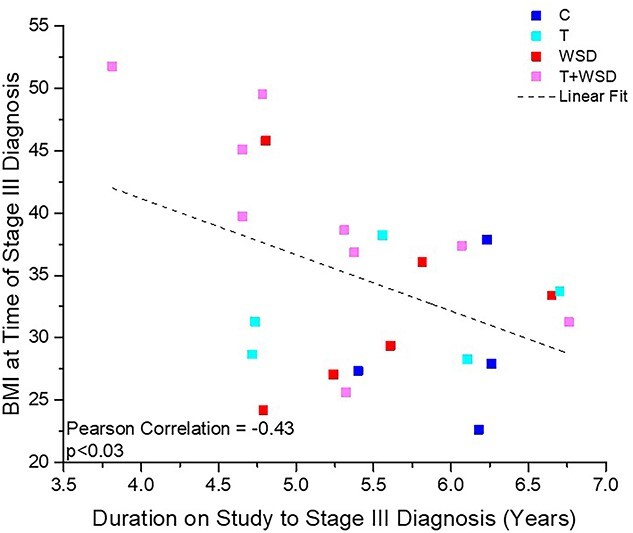

To determine if worsening metabolic state previously observed in our T + WSD cohort contributed to more rapid onset of endometriosis disease, we next compared metabolic status with the time to diagnosis of disease stages 3 and 4 (Tables 2 and 3). A higher BMI was associated with reduced time to stage 3 diagnosis (bias-adjusted Pearson correlation −0.43, P = 0.03, Supplemental Table 2, Figure 2). When metabolic status at time of diagnosis was analyzed as a discrete variable by treatment group for either stage 3 or stage 4 diagnoses, there were no significant effects of either steroid treatment or significant interaction between treatments (Table 3, Supplemental Table 2). However, consumption of the WSD was associated with significantly higher glucose (P = 0.004), HOMA-IR (P = 0.005), fasting insulin (P = 0.01), and % body fat (P = 0.01) at time of stage 3 diagnosis, most prominently in the T + WSD cohort (Table 2). Similarly, elevated glucose and percent body fat were identified as significantly impacted by consumption of the WSD at time of stage 4 diagnosis (P = 0.002 and 0.001, respectively, Table 3), and elevated insulin levels during ivGTT (P = 0.03, Table 3); again, this was driven by the changes in the T + WSD cohort.

Table 2.

Metabolic function and endometriosis: correlation with time to diagnosis of stage 3 disease

| P-value; Correlation | C | T | WSD | T + WSD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Diet | Steroid | Interaction | Mean ± SEMa | Mean ± SEMa | Mean ± SEMa | Mean ± SEMa |

| AUCb glucose | 0.004 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 7344.5 ± 1481.3a | 7331.9 ± 1481.3a | 8322.3 ± 1481.3a,b | 10448.9 ± 1481.3B |

| AUCb insulin | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 14424.7 ± 14857.5 | 13625.6 ± 14857.5 | 16604.9 ± 14857.5 | 36697.7 ± 14857.5 |

| Fasting glucose [mg/dl] | 0.66 | 0.84 | 0.48 | 61 ± 8.7 | 57.6 ± 8.7 | 60 ± 8.7 | 61.9 ± 8.7 |

| HOMA-IRc | 0.005 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 4 ± 4.7a | 5.5 ± 4.7a | 8.4 ± 4.7a,b | 14.1 ± 4.7b |

| Fasting insulin (uU/ml) | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 26.5 ± 32.1 | 38.8 ± 32.1 | 54.2 ± 32.1 | 92.8 ± 32.1 |

| BMId | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.54 | 28.9 ± 7.2 | 32 ± 7.2 | 32.6 ± 7.2 | 39.5 ± 7.2 |

| Total % fat | 0.012 | 0.19 | 0.88 | 32.9 ± 10a | 38 ± 10a,b | 44.1 ± 10a,b | 50.5 ± 10b |

aCommon mean square error, metabolic status at time of diagnosis.

bArea under curve.

cHOMA-IR = fasting glucose*fasting insulin)/405.

dBMI = weight(kg)/CrownRumpLengthb (meters).

Differences between uppercase letters (A vs B) within rows indicate differences between treatment groups, P < 0.05.

Table 3.

Metabolic function and endometriosis: correlation with time to diagnosis of stage 4 disease

| P-value; Correlation | C | T | WSD | T + WSD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Diet | Steroid | Interaction | Mean ± SEMa | Mean ± SEMa | Mean ± SEMa | Mean ± SEMa |

| AUC glucoseb | 0.002 | 0.49 | 0.6 | 7092.8 ± 1656.7A | 7241.9 ± 1656.7A | 9705.6 ± 1656.7A,B | 10708.7 ± 1656.7B |

| AUC insulinb | 0.03 | 0.91 | 0.3 | 16114.8 ± 11043.4 | 10837.3 ± 11043.4* | 23,797 ± 11043.4 | 30336.5 ± 11043.4** |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 0.4 | 0.87 | 0.2 | 65.7 ± 11.8 | 57 ± 11.8 | 63 ± 11.8 | 69.7 ± 11.8 |

| HOMA-IRc | 0.3 | 0.48 | 0.5 | 4.2 ± 27 | 4.6 ± 27 | 9.3 ± 27 | 28.2 ± 27 |

| Fasting insulin (uU/ml) | 0.2 | 0.44 | 0.5 | 26 ± 104.8 | 32.4 ± 104.8 | 60.3 ± 104.8 | 136.6 ± 104.8 |

| BMId | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.7 | 29.4 ± 7.8 | 30.9 ± 7.8 | 35.7 ± 7.8 | 40.1 ± 7.8 |

| Total % fat | 0.001 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 33.4 ± 8A | 34.8 ± 8A | 49.9 ± 8A,B | 50 ± 8B |

aCommon mean square error, metabolic status at time of diagnosis.

bArea under curve.

cHOMA-IR = (fasting glucose*fasting insulin)/405.

dBMI = weight(kg)/CrownRumpLength2 (meters).

Differences between uppercase letters (A vs B) within rows indicate differences between treatment groups, P < 0.05.

* vs** denotes P < 0.06.

Figure 2.

Linear correlation between time to onset of diagnosis with stage 3 disease and BMI at time of diagnosis. BMI measurements of individual females at time of stage 3 endometriosis diagnosis were compared to the time of diagnosis during the study (in years). Females in treatment groups C (n = 4), T (n = 5), WSD (n = 6), and T + WSD (n = 9) are represented by individual symbols with colors by group (figure legend). Dashed line represents linear fit and Pearsons bias-adjusted correlation value, as well as significance, is depicted in graph. See Results section for further details.

Omental adipose transcriptome analyses compared females with and without cystic disease at time of biopsy in year 7 (stages 0–2 vs 3 and 4; Supplemental Table 3, Supplemental File 1). There were 474 differentially expressed mRNAs in females with cystic disease, of them 277 were downregulated and 197 were upregulated (Supplemental Table 3). The most impacted “causal network”, as well as upstream regulator, was LARP1 (La ribonucleoprotein 1, translational regulator; Supplemental Table 3), which also is reflected in the Top Regulator Effect Network (Supplemental Figure 3). PANTHER analyses of gene pathways identified “Inflammation mediated by chemokine and cytokine signaling pathway (P00031)” as the most impacted gene pathway (Table 4). When gene expression was analyzed in omental adipose tissue by treatments, the greatest number of differentially expressed molecules was again in the contrast T + WSD versus C (654 downregulated and 723 upregulated gene products; Table 5, Supplemental File 2). This analysis also identified LARP1 as a “top regulator” and top “causal network”, contributing to observed changes in RNA expression (Table 5). PANTHER pathway analyses identified the top pathway as “Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor pathway (P06664)” (Table 6), and 6 of the top 10 pathways overlapped with those identified by the DGE analyses of RNAs associated with presence of cystic endometriosis (Table 4).

Table 4.

PANTHER pathways; impact of presence of cystic endometriosis on omental adipose transcriptome

| Pathways | Category name (accession): | No. of genes | Percent of gene hit vs total no. of genes | Percent of gene hit vs total no. of pathway hits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inflammation mediated by chemokine and cytokine signaling pathway (P00031) | 9 | 1.80% | 4.90% |

| 2 | Angiogenesis (P00005) | 8 | 1.60% | 4.30% |

| 3 | Wnt signaling pathway (P00057) | 7 | 1.40% | 3.80% |

| 4 | CCKR signaling map (P06959) | 6 | 1.20% | 3.20% |

| 5 | Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor signaling pathway (P00044) | 6 | 1.20% | 3.20% |

| 6 | Alzheimer disease-presenilin pathway (P00004) | 5 | 1.00% | 2.70% |

| 7 | T-cell activation (P00053) | 5 | 1.00% | 2.70% |

| 8 | PDGF signaling pathway (P00047) | 5 | 1.00% | 2.70% |

| 9 | Integrin signaling pathway (P00034) | 5 | 1.00% | 2.70% |

| 10 | Oxytocin receptor mediated signaling pathway (P04391) | 5 | 1.00% | 2.70% |

| 11 | Huntington disease (P00029) | 5 | 1.00% | 2.70% |

| 12 | EGF receptor signaling pathway (P00018) | 5 | 1.00% | 2.70% |

| 13 | Cytoskeletal regulation by Rho GTPase (P00016) | 5 | 1.00% | 2.70% |

Table 5.

IPA analyses of impact of 7 years of exposure to testosterone and WSD on omental adipose transcriptome

| Contrast | Down | Up | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| T vs C | 558 | 461 | 1019 |

| WSD vs C | 431 | 525 | 956 |

| T vs WSD | 480 | 303 | 783 |

| T + WSD vs C | 654 | 723 | 1377 |

| T + WSD vs T | 441 | 719 | 1160 |

| T + WSD vs WSD | 185 | 224 | 409 |

| Interaction | 300 | 401 | 701 |

| Top Upstream Regulators T + WSD vs C | Causal network T + WSD vs C | ||

| Name | p-value | Name | p-value |

| LARP1 | 1.07E-32 | LARP1 | 5.43E-33 |

| torin1 | 2.83E-22 | MLXIPL | 2.25E-23 |

| MLXIPL | 2.93E-22 | MYCN | 1.45E-20 |

| MYCN | 2.38E-19 | AURK | 2.23E-19 |

| YAP1 | 1.86E-14 | STUB1 | 7.00E-19 |

Table 6.

PANTHER pathways; impact of 7 years of exposure to testosterone and WSD on omental adipose transcriptome

| Pathway | Category name (accession) | No. of genes | Percent of gene hit vs total no. of genes | Percent of gene hits vs total no. of pathway hits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor pathway (P06664) | 22 | 1.70% | 5.20% |

| 2 | Wnt signaling pathway (P00057) | 19 | 1.50% | 4.50% |

| 3 | Integrin signaling pathway (P00034) | 16 | 1.30% | 3.80% |

| 4 | Angiogenesis (P00005) | 15 | 1.20% | 3.60% |

| 5 | PDGF signaling pathway (P00047) | 14 | 1.10% | 3.30% |

| 6 | EGF receptor signaling pathway (P00018) | 14 | 1.10% | 3.30% |

| 7 | Alzheimer disease-presenilin pathway (P00004) | 13 | 1.00% | 3.10% |

| 8 | CCKR signaling map (P06959) | 13 | 1.00% | 3.10% |

| 9 | Inflammation mediated by chemokine and cytokine signaling pathway (P00031) | 13 | 1.00% | 3.10% |

| 10 | Parkinson disease (P00049) | 11 | 0.90% | 2.60% |

Discussion

We report that exposure to elevated androgens in the presence of an obesogenic diet increases risk for severe endometriosis in rhesus macaques undergoing a longitudinal study (stages 3 and 4). Females in the T + WSD cohort, those with the most severe PCOS-like phenotype [14], also presented with stages 2 through 4 of endometriosis earlier than similarly diagnosed control females. While exposure to either T or WSD alone appears to play a role in disease onset, these groups had fewer numbers of affected females than the combined treatment. While clinically it is noted that women with PCOS are at increased risk for diagnosis with endometriosis if they experience ongoing infertility despite treatment [10], the link between PCOS and endometriosis is unclear. However, both conditions are associated with chronic inflammation as a proposed causal risk factor [3, 22]. These data demonstrate in a primate that consumption of an obesogenic diet in the presence of hyperandrogenemia, two phenotypic characteristics of PCOS, accelerates onset of the most severe forms of endometriosis. Therefore, women with co-diagnoses of PCOS and endometriosis may warrant aggressive intervention at earlier stages of disease.

We previously reported females in this cohort treated with either T or T + WSD developed hallmarks of progesterone resistance [14], similar to that observed in women with endometriosis [18]. These tissues were androgen-responsive as evidenced by expression of AR in lesions of a few T + WSD females recovered at necropsy. If the resulting endometriosis was solely attributed to elevated androgen exposure alone, we would expect the T alone group to develop cystic endometriosis in similar proportions as the T + WSD cohort. This was not what was observed—the T alone cohort had approximately half of the cystic disease prevalence as the T + WSD cohort. Interestingly, previous research in rhesus monkeys suggested that androgens acting via AR have an antiproliferative effect in the endometrium [23]. This would argue that if increased proliferation was driving the phenomena of endometriosis in our primates any androgenic actions might be protective. Indeed T agonists including danazol are commonly prescribed for treatment of endometriosis, due to the antiproliferative activities. While women with PCOS are reported to have elevated levels of AR in endometrium [24], they are also at higher risk for certain endometrial cancers [25]. A previous cohort study of women with a diagnosis of PCOS and continuing infertility and/or pelvic pain were 5.6-fold more likely to be diagnosed with early-stage endometriosis than fertile women seeking tubal ligation [26]. Lesions from T + WSD females in stages 3–4 displayed widespread expression of MKI67 protein, showing this tissue was highly proliferative as would be expected by these stages of endometriosis. Analyses of eutopic endometrium collected prior to onset of late-stage endometriosis in this cohort did not show a difference by treatment group in MKI67 protein expression by immunohistochemistry [14]. A later RNA-seq analysis of the eutopic endometrium collected at/near the time of diagnosis of endometriosis for several females found a significant upregulation of MKI67 mRNA expression (Log2 increase 0.8, P = 0.02) by T when compared to WSD-only treated females [16]. However, no significant changes were noted in expression of MKI67 mRNA in eutopic endometrium between females by diagnosis of endometriosis or by stage of disease at that time [16]. Thus, the impact between androgen signaling and proliferation of endometrial tissues in this NHP model may be complex and stage-specific; this concept needs further study.

PCOS and endometriosis share evidence for common involvement of a systemic inflammatory state contributing to onset and severity of disease; of note, classically inflammation is highly associated with obesity [25]. One of the hallmarks of obesity is an altered metabolic state. Therefore, we first analyzed correlations between metabolic status and time to onset of disease for each stage of endometriosis. We previously reported females treated with T + WSD in this cohort gained more weight in a shorter time period on the diet and developed hallmarks of insulin resistance quicker than T or WSD alone [15]. The strong negative correlation between BMI and time to diagnosis with stage 3 disease (lower BMI was associated with increased time to diagnosis with stage 3 disease), along with the significant alterations to glucose clearance, insulin response, and insulin sensitivity measured near time of diagnosis in the T + WSD cohort, indicates that overall metabolic dysfunction promotes the development of cystic disease. It remains to be investigated if the worsened metabolic state of the T + WSD group is solely responsible for accelerated onset of cystic disease, or if the interaction between T and altered metabolism played a role. It should be noted that transgender adolescents undergoing T therapy show persistent endometriosis [27]. Regardless, further therapies for endometriosis may include modulation of metabolic status including use of insulin sensitizers. Indeed, exposure to metformin resulted in reduction in size of endometrial grafts in a rat model of endometriosis [28], and future studies focused on metabolic pathways could be used to treat persistent disease.

Endometrial progesterone resistance is one of the factors contributing to infertility in women with PCOS. This is not related to anovulation. Even after ovulation induction with clomiphene citrate the endometrium of women still displayed dysregulated endometrial gene expression, including alterations in normal estrogen receptor signaling [29]. This is similar to a previous analysis in this cohort of females demonstrating dysregulated estrogen receptor signaling in the endometrium was observed in females who had cystic stages of disease (stages 3 and 4) [16]. Clomiphene citrate has been shown to alter insulin-like growth factor signaling in women with PCOS, but does not improve insulin sensitivity [30]. A Cochrane review of the use of insulin sensitizers and clomiphene citrate found that when combined with metformin, a higher rate of clinical pregnancies was observed [31]. Metformin treatment alone may have led to a similar live birth rate, but this varied by presence of obesity. A caveat of these studies was the reported low quality of evidence despite rather large number of studies (48) including RCTs (2) analyzed. These data show improvement of metabolic status may help normalize endometrial gene expression, reducing risk for endometriosis in women with PCOS. While rhesus macaque females in this cohort treated with T were subfertile, there is also a strong correlation between suboptimal metabolic status and poor pregnancy outcomes following timed-mating in these females [13]. Given the link between the metabolic alterations in these rhesus females, particularly the T + WSD cohort, documented evidence for some endometrial progesterone resistance [14], and elevated risk for endometriosis [16], future experiments examining insulin sensitizing agents and endometriosis treatments, and fertility post-treatment in rhesus monkeys are warranted.

The T + WSD cohort also displayed alterations in metabolism within their omental adipose tissue depot earlier in the study compared to other cohorts [32]. This depot reflects the abdominal environment, and further analyses of alterations in gene expression can be used to analyze the overall inflammatory state of the individual. The most significantly altered gene pathway associated with cystic disease, “Inflammation mediated by chemokine and cytokine signaling pathway”, includes several immune modulators previously associated with endometriosis in women [33]. We previously reported altered gene expression within the eutopic primate endometrium itself was associated with presence of cystic disease [16]. Alterations to this same inflammatory pathway within eutopic endometrial tissue were identified as significantly associated with cystic disease, suggesting an overall inflammatory phenotype may contribute to disease severity. And the effects of the Top Regulator Network include alterations in cell death pathways and nerve growth, both of which are shown to be altered in tissues adjacent to endometriotic lesions [33, 34]. While the RNA-seq study revealed a modest number of genes associated with cystic disease in this cohort, it is clear these pathways can be further analyzed for future therapeutic targets for endometriosis in primates.

In conclusion, these data demonstrate metabolic disturbances associated with exposure to androgens in the presence of an obesogenic “Western-style” diet are correlated with accelerated onset of cystic endometriosis in rhesus females. This NHP study provides evidence that endometriosis observed in women with PCOS diagnosis may be closely related to alterations to their metabolic status, and not androgen exposure alone. These data should also provide guidance for further therapies to treat recurrent endometriosis not alleviated by current therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the ONPRC Surgical Services Unit and Clinical Medicine Unit staff for their care, treatment and accurate descriptions of females in this long-term study. The authors acknowledge financial support by Bayer Pharma for RNA-seq analyses of the omental transcriptome. We thank the current and former members of the ONPRC NICTRI NHP Core for their assistance in all aspects of this study.

Library preparation and sequencing were performed by the OHSU Massively Parallel Sequencing Shared Resource. This core is supported by the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA069533 and by funding from the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust.

RNA isolation from the omental adipose tissues was performed in the OHSU Gene Profiling Shared Resource. This core receives partial support from the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA069533.

Contributor Information

Cecily V Bishop, Division of Reproductive and Developmental Sciences, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Oregon Health & Science University, Beaverton, Oregon, USA; Department of Animal and Rangeland Sciences, College of Agricultural Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA.

Diana L Takahashi, Division of Cardiometabolic Health, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Beaverton, Oregon, USA.

Fangzhou Luo, Division of Reproductive and Developmental Sciences, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Oregon Health & Science University, Beaverton, Oregon, USA.

Heather Sidener, Division of Comparative Medicine, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Beaverton, Oregon, USA.

Lauren Drew Martin, Division of Comparative Medicine, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Beaverton, Oregon, USA.

Lina Gao, Bioinformatics & Biostatistics Core, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Beaverton, Oregon, USA.

Suzanne S Fei, Bioinformatics & Biostatistics Core, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Beaverton, Oregon, USA.

Jon D Hennebold, Division of Reproductive and Developmental Sciences, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Oregon Health & Science University, Beaverton, Oregon, USA; Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Ov D Slayden, Division of Reproductive and Developmental Sciences, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Oregon Health & Science University, Beaverton, Oregon, USA; Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Data availability statement

The RNA-seq datasets generated from omental adipose tissues for this study can be found in the openly available repository NCBI BioProject database under BioProject ID: PRJNA695089 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA695089). All other summarized discrete data are available within the article and/or its supplementary materials. Raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, ODS, upon reasonable request with permission from Oregon National Primate Research Center, Oregon Health & Science University officials.

Conflict of interests

The authors acknowledge financial support by Bayer Pharma AG for RNA-seq analyses of the omental transcriptome (to ODS). However, these data were not reviewed before publication by Bayer Pharma nor did authors seek approval by Bayer Pharma before publication of these data. Research reported in this publication was also supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the Office of the Director, of the United States National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authors’ Contributions

CB performed ultrasonography for endometriosis diagnosis; provided all final analyses of endometriosis staging, metabolism, and onset in rhesus females; coordinated and evaluated RNA-seq analyses of omental tissues; compiled all data; and prepared manuscript. DT collected all metabolic data and performed preliminary assessment of metabolic function, assisted in tissue collection and processing, proofread and approved manuscript. FL validated all details of biopsy and endometriosis tissues, performed histological staining of endometriosis lesions, proofread and approved manuscript. HS performed physical examinations, including ultrasonography of rhesus females for endometriosis diagnosis and staging, proofread and approved manuscript. LM supervised laparoscopic evaluations of rhesus females for endometriosis diagnosis and staging, proofread and approved manuscript. LG performed all statistical analyses of RNA-seq data, proofread and approved manuscript. SF supervised statistical analyses of RNA-seq data, including consultation on transcript quality and sequencing, proofread and approved manuscript. JH contributed to study design, provided feedback on data interpretation, obtained continued funding for the study, proofread and approved manuscript. OS contributed to study design, provided feedback on data interpretation, obtained continued funding for the study, proofread and approved manuscript.

References

- 1. Peterson CM, Johnstone EB, Hammoud AO, Stanford JB, Varner MW, Kennedy A, Chen Z, Sun L, Fujimoto VY, Hediger ML, Buck Louis GM, Group ESW . Risk factors associated with endometriosis: importance of study population for characterizing disease in the ENDO study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013; 208:451 e451–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agarwal SK, Antunez-Flores O, Foster WG, Hermes A, Golshan S, Soliman AM, Arnold A, Luna R. Real-world characteristics of women with endometriosis-related pain entering a multidisciplinary endometriosis program. BMC Womens Health 2021; 21:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. FertilSteril 2012; 98:511–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu DT, Hitchcock A. Endometriosis: its association with retrograde menstruation, dysmenorrhoea and tubal pathology. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1986; 93:859–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. D'Hooghe TM, Bambra CS, Raeymaekers BM, Koninckx PR. Increased prevalence and recurrence of retrograde menstruation in baboons with spontaneous endometriosis. Hum Reprod 1996; 11:2022–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rippy MK, Lee DR, Pearson SL, Bernal JC, Kuehl TJ. Identification of rhesus macaques with spontaneous endometriosis. J Med Primatol 1996; 25:346–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zondervan KT, Weeks DE, Colman R, Cardon LR, Hadfield R, Schleffler J, Trainor AG, Coe CL, Kemnitz JW, Kennedy SH. Familial aggregation of endometriosis in a large pedigree of rhesus macaques. Hum Reprod 2004; 19:448–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carsote M, Terzea DC, Valea A, Gheorghisan-Galateanu AA. Abdominal wall endometriosis (a narrative review). Int J Med Sci 2020; 17:536–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, Dokras A, Laven J, Moran L, Piltonen T, Norman RJ, International PN . Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 2018; 33:1602–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holoch K, Savaris RF, Forstein DA, Miller PB, Higdon L, Likes CE, Lessey BA. Coexistence of polycystic ovary syndrome and endometriosis in women with infertility. J endometriosis and Pelvic Pain Disorders 2014; 6:4. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferrero S, Anserini P, Remorgida V, Ragni N. Body mass index in endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2005; 121:94–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tang Y, Zhao M, Lin L, Gao Y, Chen GQ, Chen S, Chen Q. Is body mass index associated with the incidence of endometriosis and the severity of dysmenorrhoea: a case-control study in China? BMJ Open 2020; 10:e037095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bishop CV, Stouffer RL, Takahashi DL, Mishler EC, Wilcox MC, Slayden OD, True CA. Chronic hyperandrogenemia and Western-style diet beginning at puberty reduces fertility and increases metabolic dysfunction during pregnancy in young adult, female macaques. Hum Reprod 2018; 33:694–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bishop CV, Mishler EC, Takahashi DL, Reiter TE, Bond KR, True CA, Slayden OD, Stouffer RL. Chronic hyperandrogenemia in the presence and absence of a Western-style diet impairs ovarian and uterine structure/function in young adult rhesus monkeys. Hum Reprod 2018; 33:128–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. True CA, Takahashi DL, Burns SE, Mishler EC, Bond KR, Wilcox MC, Calhoun AR, Bader LA, Dean TA, Ryan ND, Slayden OD, Cameron JL et al. Chronic combined hyperandrogenemia and Western-style diet in young female rhesus macaques causes greater metabolic impairments compared to either treatment alone. Hum Reprod 2017; 32:1880–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bishop CV, Luo F, Gao L, Fei SS, Slayden OD. Mild hyperandrogenemia in presence/absence of a high-fat, Western-style diet alters secretory phase endometrial transcriptome in nonhuman primates. F&S Science 2020; 1:172–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bulun SE, Cheng YH, Yin P, Imir G, Utsunomiya H, Attar E, Innes J, Julie KJ. Progesterone resistance in endometriosis: link to failure to metabolize estradiol. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2006; 248:94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Patel BG, Rudnicki M, Yu J, Shu Y, Taylor RN. Progesterone resistance in endometriosis: origins, consequences and interventions. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2017; 96:623–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fazleabas AT. Progesterone resistance in a baboon model of endometriosis. SeminReprodMed 2010; 28:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bishop CV, Reiter TE, Erikson DW, Hanna CB, Daughtry BL, Chavez SL, Hennebold JD, Stouffer RL. Chronically elevated androgen and/or consumption of a Western-style diet impairs oocyte quality and granulosa cell function in the nonhuman primate periovulatory follicle. J Assist Reprod Genet 2019; 36:1497–1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Raman A, Colman RJ, Cheng Y, Kemnitz JW, Baum ST, Weindruch R, Schoeller DA. Reference body composition in adult rhesus monkeys: glucoregulatory and anthropometric indices. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005; 60:1518–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. González F. Inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome: underpinning of insulin resistance and ovarian dysfunction. Steroids 2012; 77:300–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. El Hayek S, Bitar L, Hamdar LH, Mirza FG, Daoud G. Poly cystic ovarian syndrome: an updated overview. Front Physiol 2016; 7:124–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Apparao KB, Lovely LP, Gui Y, Lininger RA, Lessey BA. Elevated endometrial androgen receptor expression in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Biol Reprod 2002; 66:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Holoch KJ, Savaris RF, Forstein DA, Miller PB, Higdon HL, Likes CE, Lessey BA. Coexistence of polycystic ovary syndrome and endometriosis in women with infertility. J Endometr Pelvic Pain Disord 2014; 6:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chavarro JE, Rich-Edwards JW, Gaskins AJ, Farland LV, Terry KL, Zhang C, Missmer SA. Contributions of the nurses' health studies to reproductive health research. Am J Public Health 2016; 106:1669–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shim JY, Laufer MR, Grimstad FW. Dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in transgender adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2020; 33:524–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jamali N, Zal F, Mostafavi-Pour Z, Samare-Najaf M, Poordast T, Dehghanian A. Ameliorative effects of quercetin and metformin and their combination against experimental endometriosis in rats. Reprod Sci 2021; 28(3):683–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Savaris RF, Groll JM, Young SL, DeMayo FJ, Jeong J-W, Hamilton AE, Giudice LC, Lessey BA. Progesterone resistance in PCOS endometrium: a microarray analysis in clomiphene citrate-treated and artificial menstrual cycles. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 2011; 96:1737–1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. De Leo V, la Marca A, Morgante G, Ciotta L, Mencaglia L, Cianci A, Petraglia F. Clomiphene citrate increases insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 and reduces insulin-like growth factor-I without correcting insulin resistance associated with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Hum Reprod 2000; 15:2302–2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morley LC, Tang T, Yasmin E, Norman RJ, Balen AH. Insulin-sensitising drugs (metformin, rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, D-chiro-inositol) for women with polycystic ovary syndrome, oligo amenorrhoea and subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 11:Cd003053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Varlamov O, Bishop CV, Handu M, Takahashi D, Srinivasan S, White A, Roberts CT Jr. Combined androgen excess and Western-style diet accelerates adipose tissue dysfunction in young adult, female nonhuman primates. Hum Reprod 2017; 32:1892–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Di Nisio V, Rossi G, Di Luigi G, Palumbo P, D'Alfonso A, Iorio R, Cecconi S. Increased levels of proapoptotic markers in normal ovarian cortex surrounding small endometriotic cysts. Reprod Biol 2019; 19:225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morotti M, Vincent K, Brawn J, Zondervan KT, Becker CM. Peripheral changes in endometriosis-associated pain. Hum Reprod Update 2014; 20:717–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq datasets generated from omental adipose tissues for this study can be found in the openly available repository NCBI BioProject database under BioProject ID: PRJNA695089 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA695089). All other summarized discrete data are available within the article and/or its supplementary materials. Raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, ODS, upon reasonable request with permission from Oregon National Primate Research Center, Oregon Health & Science University officials.