Abstract

Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains containing the cag Pathogenicity Island (cag PAI) is strongly correlated with the development of severe gastric disease, including gastric and duodenal ulceration, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric carcinoma. Although in vitro studies have demonstrated that the expression of genes within the cag PAI leads to the activation of a strong host inflammatory response, the functions of most cag gene products and how they work in concert to promote an immunological response are unknown. We developed a transcriptional reporter that utilizes urease activity and in which nine putative regulatory sequences from the cag PAI were fused to the H. pylori ureB gene. These fusions were introduced in single copies onto the H. pylori chromosome without disruption of the cag PAI. Our analysis indicated that while each regulatory region confers a reproducible amount of promoter activity under laboratory conditions, they differ widely in levels of expression. Transcription initiating upstream of cag15 and upstream of cag21 is induced when the respective fusion strains are cocultured with an epithelial cell monolayer. Results of mouse colonization experiments with an H. pylori strain carrying the cag15-ureB fusion suggested that this putative regulatory region appears to be induced in vivo, demonstrating the importance of the urease reporter as a significant development toward identifying in vivo-induced gene expression in H. pylori.

Chronic infection with the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori is a significant cause of worldwide morbidity and mortality. Millions of people annually experience H. pylori-associated disease that most often presents as chronic gastritis. However, infection has also been correlated with gastric and duodenal ulcer disease, gastric adenocarcinoma (22), and mucosa-associated lymphoma (8, 20). The most severe H. pylori-mediated disease states are attributable to strains harboring the cag pathogenicity island (cag PAI) (type I strains). Two groups independently identified this discrete 40-kb DNA element in different clinical isolates (1, 8).

Analysis of the cag PAI sequence suggested that it encodes a putative secretion apparatus with homology to type IV secretion systems (8, 35), which are involved in the transfer of effector macromolecules into host cells (7, 39). Evidence supporting such a role for the H. pylori cag PAI includes the finding that null mutations in several of the genes abolish the ability of type I strains to elicit interleukin 8 (IL-8) secretion by gastric epithelial cells (1, 8, 18, 37). This cytokine signal triggers an inflammatory response that, when chronic, contributes to epithelial cell death and tissue damage (34). The ability of type I strains to elicit an IL-8 response strongly supports a role for the cag PAI in chronic inflammation (8, 9, 10, 14, 27). Additionally, it has been demonstrated that one of the cag gene products, CagA, is translocated into host cells, where it becomes modified by tyrosine phosphorylation (2, 24, 26, 32). Inactivation of several of the cag genes was shown to abolish both CagA translocation and tyrosine phosphorylation, suggesting that both events depend on an intact cag PAI (24, 26, 32).

We are interested in how and to what extent H. pylori regulates its gene expression, particularly with regard to establishing infection. An impediment to this type of analysis for H. pylori has been the lack of sensitive reporter systems for measuring the gene expression that is required for establishing infection. Here we describe the development of a new reporter system for H. pylori that utilizes urease production as a measure of gene expression. The urease reporter provides a sensitive and accurate measure of H. pylori gene expression that can be quantified by an enzymatic assay, Western analysis, or mRNA determination. We have used this reporter system to identify and characterize transcriptionally active regions of the cag PAI in H. pylori. Our results suggest that the cag PAI is comprised of genes arranged in several multicistronic units. Each transcriptional unit that we investigated has a characteristic level of expression in H. pylori cells grown on laboratory medium. We provide evidence that transcription from two of these units is upregulated when H. pylori is cocultured in the presence of a human epithelial cell line.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

H. pylori C57, a type I clinical isolate, and M6, a mouse-adapted type I isolate, were donated by Steven Czinn (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio) and are described in Table 1. Strain 412 is a derivative of H. pylori C57 in which the ureB gene has been replaced by a kanamycin resistance (Km) gene from Tn903. A plasmid carrying the relevant upstream (1,546 bp) and downstream (945 bp) sequences flanking the Km gene was constructed from PCR DNA and used to transform strain C57 with selection for kanamycin resistance. The deletion in this strain extends from nucleotide 35 in the ureB coding sequence to 9 nucleotides beyond the 3′ end of the gene. Strain 472 is a derivative of strain 412 containing the ureB gene located downstream of the hpn gene.

TABLE 1.

H. pylori strains used in this study

| Name | Relevant genotype | Urease activitya |

|---|---|---|

| C57 | H. pylori type I clinical isolate | + |

| Alston | H. pylori type I clinical isolate | + |

| M6 | Mouse-adapted strain | + |

| 412 | ΔureB::kanb | − |

| 472 | 412 hpn::[Φ(Phpn-ureBcat)]c | ++ |

| 585 | 412 hpn::[Φ(Phpn–T1-T2–ureBcat)]c | ± |

| cag-ureB | 585; merodiploid for cag PAI noncoding sequences cloned between T1-T2 and ureBcat | Variable |

+, wild-type levels; −, undetectable; ++, greater than wild-type levels; ±, less than wild-type levels. All strains contained the cag PAI.

Replacement of the ureB ORF by a Kmr gene.

The fusions are located in a noncoding region 55 bp downstream of the hpn stop codon, leaving hpn intact.

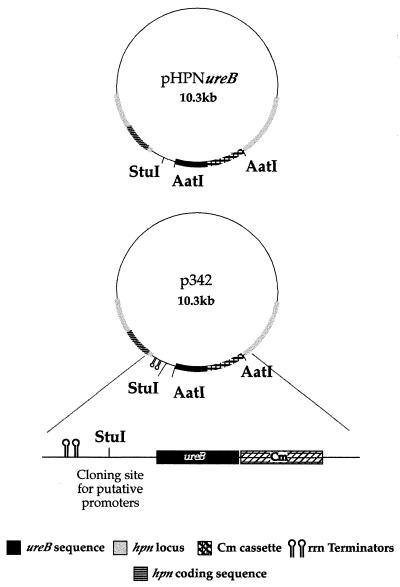

Strain 472 was constructed by cloning a 1.7-kb DNA fragment containing the entire ureB open reading frame (ORF) together with a 1.3-kb DNA fragment containing the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene (38) into pHPN2 (16) such that the ureB gene was positioned 55 bp downstream of the hpn ORF and the CAT gene was located directly downstream of ureB (Fig. 1). Transformation of strain 412 with the resulting plasmid, pHPNureB, yielded the Cmr Kmr urease-positive strain 472.

FIG. 1.

ureB reporter construct. A promoterless ureB gene with its native Shine-Dalgarno sequence was introduced, along with a chloramphenicol resistance gene, into the hpn locus of plasmid pHPN2 to give pHPNureB. In order to block any transcription originating upstream of ureB, DNA encoding tandem rrnB transcriptional terminators was inserted just downstream of the hpn coding sequence in pHPNureB, giving rise to the urease reporter plasmid p342.

Strain 585 is a derivative of strain 412 in which DNA encoding the strong tandem rRNA transcriptional terminators (T1 and T2) was inserted 55 bp downstream of the hpn gene, thus blocking hpn-mediated ureB expression. Strain 585 was derived by transformation of strain 412 with plasmid p342 (Fig. 1), which was constructed as follows. StuI/AatII restriction sites were introduced 55 bp downstream of the hpn ORF in pHPN2 by PCR amplification of the entire plasmid by the protocol of Barnes (4). The T1-T2 terminator region from pKK223-3 (6) was PCR amplified using compatible primers, and the product was cloned into the newly generated StuI/AatII site in pHPN2, resulting in pHPNrrnB. The ureB-CAT gene sequence from pHPNureB (see above), including AatII sites, was PCR amplified and cloned into pHPNrrnB to generate plasmid p342 (Fig. 1). Transformation of strain 472 with p342 gave rise to Cmr Kmr derivatives which lacked urease activity, indicating that the transcription of ureB from the hpn promoter is efficiently blocked by the T1 and T2 terminators.

An H. pylori plasmid, pUOA26, which contains a chloramphenicol resistance determinant from Campylobacter coli that has been shown to be expressed in H. pylori (38) was donated by Diane Taylor.

The Escherichia coli strains used were DH5α (Bethesda Research Laboratories) and ER1793 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.).

Bacterial growth and HEp-2 cell tissue culture.

H. pylori C57 was maintained on campylobacter agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.)–5% defibrinated sheep blood (Binax-NEL, Waterville, Maine) supplemented with 10 μg of vancomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml, 2.5 U of polymyxin B (Sigma) per ml, 5 μg of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Elkins Sinn, Cherry Hill, N.J.) per ml, and, where appropriate, 15 μg of kanamycin (Sigma) per ml and 10 μg of chloramphenicol (Sigma) per ml. H. pylori broth cultures were grown in brucella broth (Difco and Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) supplemented with 5% horse serum (Gibco BRL). All H. pylori cultures were incubated in GasPak jars (BBL, Becton Dickinson Labware, Lincoln, N.J.) with Campypaks (BBL) to generate a microaerobic environment. E. coli DH5α and ER1793 were grown on L medium. The human laryngeal carcinoma cell line HEp-2 was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% fetal calf serum and glutamine (Gibco BRL). Cells were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Urease assay.

Urease activity was determined by the phenol-hypochlorite method (Sigma) (3, 16, 17). For this, confluent cells from plate cultures of H. pylori strains were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), washed once, and resuspended in PBS. Equivalent numbers of cells from each strain, as determined by measurement of the optical density at 600 nm, were pelleted and resuspended in ice-cold water containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Samples were vortexed vigorously for 1 min, incubated on ice for 15 min, and revortexed. After centrifugation, supernatants were added to a buffer solution of urea (70 mg/ml) in 5 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 6.8) and incubated at room temperature. Samples were removed at 0, 5, 15, 60, and 120 min, added to phenol nitroprusside and alkaline hypochlorite, and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Color development was measured with a spectrophotometer as the optical density at 625 nm. Urease activity is reported as nanomoles of urea hydrolyzed per minute per microgram of total protein, as determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad).

Construction of cag-ureB fusions.

Several of the ORFs in the cag PAI DNA (35) are preceded by noncoding sequences of several hundred nucleotides, which we thought likely to contain sequences required for their expression. Nine of these putative promoter regions were analyzed using the ureB reporter. A portion (500 to 1,000 bp) of sequence located directly upstream of the ATG start codon of the nine selected cag genes was PCR amplified from the clinical isolate Alston. The primers used for the amplifications are listed as pairs using the following notation: primer designation (locus amplified, 5′ TIGR [The Institute for Genomic Research] genome coordinate) (35)—ure1 ( ureA, 78718) and ure2 (ureB, 80249); ure3 (ureI, 83814) and ure4 (ureI, 84848); ure5 (ureB, 77277) and ure6 (ureB, 75521); 520-5 (cag1, 546343) and 520-3 (cag1, 547345); 530-5 (cag10, 564951) and 530-3 (cag10, 563959); 531-5 (cag11, 563446) and 531-3 (cag11, 564405); 534-5 (cag13, 567653) and 534-3 (cag13, 566676); 535-5 (cag14, 568449) and 535-3 (cag14, 567487); 536-5 (cag15, 569258) and 536-3 (cag15, 568278); 537-5 (cag16, 567734) and 537-3 (cag16, 568771); 542-5 (cag21, 575199) and 542-3 (cag21, 574242); and 546-5 (cag25, 579087) and 546-3 (cag25, 580087). All primers were 20 to 25 nucleotides long and corresponded exactly to the published sequence (35).

The resulting fragments were cloned into the StuI cloning site of p342, just upstream of the promoterless ureB gene. Plasmids with the inserts oriented in the correct direction were identified by PCR and used for insertion of the fusions into the hpn chromosomal locus in strain 412 as described above. Individual colonies from each transformation were tested by PCR using primers specific to the 3′ end of the hpn coding sequence and the 5′ end of the ureB coding sequence to confirm that each cag-ureB fusion had specifically recombined at the hpn locus. In all cases, the expected increase in the size of the PCR products obtained from the fusion strains, compared to that obtained from strain 585 (no-insert control), was seen, indicating that the fusions were located at the hpn locus (data not shown). The fusion strains are described in Table 1.

Assay of adhesion of H. pylori strains to HEp-2 cells.

HEp-2 cells were seeded in 100-mm tissue culture dishes (Corning) at densities of 105 to 106 cells/dish. After a 24-h incubation period, the cells were washed twice with PBS and infected with 5 × 109 CFU of H. pylori strain C57, 412, 472, or 585 or one of the cag-ureB fusion strains. H. pylori cultures used for infections were harvested in PBS after 16 h of growth on campylobacter agar plates, pelleted, and then resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium to 109 CFU/ml. Negative controls included uninfected HEp-2 cells and samples of each cag-ureB fusion strain in the absence of a monolayer. Incubations were carried out for 8 h in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. Following this step, supernatants of all samples were removed for microscopic examination, determination of viable plate counts, IL-8 analysis, determination of urease activity, and Western analysis.

Assay of IL-8 induction by HEp-2 cells.

IL-8 analysis was performed at the laboratory of David Acheson (New England Medical Center, Boston, Mass.). The analysis was carried out with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as described by Sharma et al. (27). Following the adhesion assay, 300-μl aliquots of the supernatants overlaying the epithelial cell monolayer were removed and centrifuged to remove H. pylori cells. The resulting culture fluid was assayed for IL-8 using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Endogen, Woburn, Mass.) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Colonization ability of cag-ureB fusions in mice.

For mouse colonization, the cag-ureB constructs were transformed into M6, the mouse-adapted strain, in the following manner. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from strain 412 (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). The recipient strain, H. pylori M6, was grown overnight in brucella broth with 10% fetal calf serum (BBH10) under standard conditions. Cultures containing 108 to 109 CFU/ml were diluted 1:100 in 10 ml of BBH10 and incubated for up to 6 h, after which 20 to 50 ng of 412 chromosomal DNA was added; incubation was continued overnight. Each culture was then diluted 1:4 in BBH10 containing 20 μg of kanamycin per ml and grown overnight. Aliquots (1 ml) were plated on 5% sheep blood agar plates containing 20 μg of kanamycin per ml and incubated for 4 to 5 days. Several candidate colonies were chosen, and replacement of ureB with the kanamycin cassette was verified by PCR. One of the candidates, which was also shown to be urease negative, was selected and called 412M.

412M was used as the recipient for chromosomal DNA isolated from the 585 derivatives containing the cag-ureB fusions and was transformed exactly as described above. Colonies from each transformation were pooled and stored at −70°C in brucella broth with 15% glycerol until mouse inoculation. Urease activity was assayed in vitro as previously described (11).

Female 4- to 6-week-old Helicobacter-free C57BL/6 mice from Jackson Laboratory were orally inoculated with 107 to 108 rapidly motile, mid-log-phase H. pylori cells grown in BBH10. Mice were sacrificed 2 or 8 weeks after infection, and the number of CFU per gram of gastric mucosa was determined by plate dilution.

Protein preparation.

H. pylori whole cells and their supernatants incubated in the absence of an epithelial cell monolayer were transferred to 2-ml Microfuge tubes (USA Scientific, Ocala, Fla.) and precipitated overnight with trichloroacetic acid (10% final concentration). Precipitates were collected by centrifugation, washed with acetone, air dried, and resuspended in equal volumes of PBS and boiling buffer.

The supernatants of samples containing both H. pylori cells and epithelial cells were aspirated, and the monolayers were washed twice with PBS to remove any nonadherent H. pylori cells. One milliliter of lysis buffer, made with 9 ml of PBS, 0.9 ml of 0.05% Triton X-100 (Sigma), and one protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany), was added to the adherent H. pylori and epithelial cells; the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The lysed monolayers were scraped from the plates into Corex tubes and vortexed vigorously several times. One-twentieth of the sample volumes was removed to determine urease activity, and 1/50 of the sample volumes was used to measure protein concentrations. The samples were placed on ice and sonicated with three 30-s pulses using a 50% duty cycle, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm (Eppendorf microcentrifuge 5415C) for 5 min at 4°C. Supernatants, containing the cytoplasmic fractions, were mixed with 4 ml of methanol 1 ml of chloroform and collected by centrifugation at 7,500 rpm (Eppendorf microcentrifuge 5415C) for 1 min at 4°C. The resulting pellets were resuspended in equal volumes of PBS and boiling buffer. All protein samples were stored at −20°C.

Western analysis.

Samples, each containing protein from approximately 107 CFU of H. pylori, were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), and blocked overnight at 4°C in PBS–5% milk. Membranes were probed with monoclonal anti-UreB antibody (1:4,000), donated by Harry Kleanthous (Oravax, Cambridge, Mass.), and a polyclonal antibody raised against H. pylori isocitrate dehydrogenase (1:400), donated by LiLi Huang (St. Elizabeth's Hospital, Boston, Mass.), to normalize for loading differences. The secondary antibodies, goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (IgG) and rabbit anti-mouse IgG (1:1,500), were both conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Zymed, San Francisco, Calif.). Proteins were detected using an ECL kit (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations.

RESULTS

Use of urease as a reporter of gene expression.

A derivative of H. pylori C57 with a deletion of the ureB gene, which encodes one of the two subunits of urease, was constructed to determine if urease activity could be used as a reporter of promoter activity in H. pylori. This strain, 412, was devoid of urease activity (Table 2). Transformation of strain 412 with plasmid pHPNureB, carrying a promoterless ureB gene flanked by sequences homologous to the hpn locus, yielded recombinants with the ureB gene integrated immediately downstream of the hpn coding sequence on the chromosome. Since hpn is highly expressed in H. pylori (J. V. Gilbert, unpublished observation), we expected that transcription from the hpn promoter would drive the expression of ureB in this strain, complementing the urease defect. The recombinants produced high levels of urease (Table 2). Primer extension analysis of RNA isolated from one of the recombinants, strain 472, indicated that ureB was expressed from the hpn promoter (results not shown). These data indicate that the presence of ureB at the hpn locus efficiently complements the urease defect in strain 412. Plasmid pHPN was specifically designed to insert desired sequences at the neutral hpn locus. This plasmid is unable to replicate in H. pylori and, as a result of double-crossover events, yields recombinants containing the desired gene (ureB in this case) and lacking plasmid sequences. Thus, it is a convenient tool for complementation analysis and evaluation of the expression of genes present in single copies on the chromosome. It is particularly useful for H. pylori, which has few, if any, stable plasmid vectors.

TABLE 2.

In vitro urease activities of H. pylori C57 and cag-ureB fusion constructsa

| Strain | nmol of urea hydrolyzed/min/μg of total protein |

|---|---|

| C57 | 6.15 ± 0.03 |

| 412 | 0.16 ± 0.03 |

| 472 | 13.10 ± 0.7 |

| 585 | 0.38 ± 0.03 |

| 585(cag1-ureB) | 3.13 ± 0.39 |

| 585(cag10-ureB) | 0.69 ± 0.1 |

| 585(cag11-ureB) | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

| 585(cag13-ureB) | 0.11 ± 0.04 |

| 585(cag14-ureB) | 0.16 ± 0.01 |

| 585(cag15-ureB) | 0.28 ± 0.00 |

| 585(cag16-ureB) | 0.21 ± 0.00 |

| 585(cag21-ureB) | 0.69 ± 0.14 |

| 585(cag25-ureB) | 0.99 ± 0.08 |

Wild-type H. pylori strain C57, its ureB mutant derivative 412, and a series of derivatives containing chromosomal cag-ureB fusions are described in Materials and Methods. In the fusion strains, the gene fusions are integrated at a neutral site in the chromosome, leaving the cag PAI intact. Urease activities were quantitated by the phenol-hypochlorite method and are reported as the mean and standard deviation.

In order to use pHPNureB for analysis of promoter activity, as described above, it was modified so that upstream promoter activity would be blocked. DNA encoding the rRNA transcriptional terminators, T1 and T2 (6), was inserted just upstream of the ureB gene in pHPNureB, generating plasmid p342 (Fig. 1). Transformation of strain 412 with p342 gave rise to ureB recombinants that lacked urease activity (strain 585 in Tables 1 and 2), demonstrating that the T1 and T2 terminators efficiently block transcription initiating at the hpn promoter. As shown below, the insertion of promoter-containing DNA into a cloning site located between the rRNA terminators and ureB on plasmid p342 leads to ureB expression in cells transformed with the relevant plasmids.

Analysis of cag promoters using cag-ureB fusions.

The cag genes present on the cag PAI of type I H. pylori strains play a key role in interactions between the bacterium and its host. We wished to test the possibility that some of these genes might be induced when cocultured with eukaryotic cells. Since little information was available on the location of promoter sequences within the cag PAI region, we used the ureB reporter system to identify cag sequences with promoter activity. DNA containing 500 to 1,000 bp of sequence upstream from a number of the cag genes was tested for promoter activity. Nine cag PAI DNA sequences containing putative promoters were cloned into p342 in the correct orientation with respect to ureB, and the resulting plasmids were used for transformation of strain 412. The transformants were merodiploid for the cloned cag sequences and had an intact cag PAI. While each fusion strain gave a reproducible level of urease activity when grown on laboratory medium, the amount of urease activity among the fusions varied widely, ranging from 0.16 to 13.1 nmol of urea hydrolyzed/min/μg of total protein. Of the nine regions examined by this approach, four showed promoter activity above that of strain 585, as measured by the hydrolysis of urea (Table 2). The cag1-ureB fusion produced approximately 50% of the urease activity of parent strain C57, while the cag10-, cag21-, and cag25-ureB fusions produced between 10 and 15% of the parental urease activity. These results indicate that these cag DNA fragments contain promoters that give rise to substantial promoter activity. The urease activities in strains carrying the cag15- and cag16-ureB fusions were similar to that of strain 585. However, the urease activities in strains carrying the cag13- and cag14-ureB fusions and particularly the strain containing the cag11-ureB fusion, were markedly below that of strain 585.

Coculturing with an epithelial cell monolayer influences cag-ureB expression.

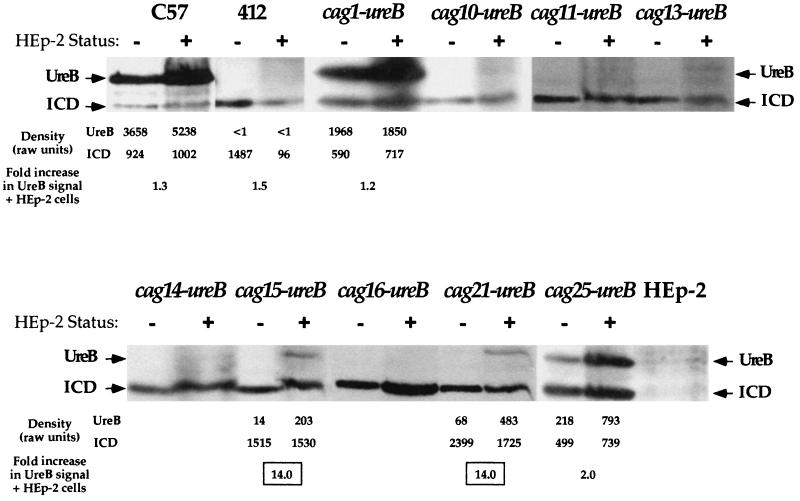

Figure 2 shows the results of a Western blot analysis performed on protein extracts isolated from cag-ureB fusion strains cocultured with epithelial cells as well as the same fusion strains cultured in medium alone. The expression of all but two of the cag-ureB fusions was unaltered under these conditions. The two exceptions, strain 585 containing the cag15-ureB fusion [585(cag15-ureB)] and strain 585(cag21-ureB), showed an approximately 14-fold increase in UreB protein levels upon coculturing with epithelial cells relative to the level strains cultured in RPMI 1640 medium alone (Fig. 2). To confirm that the fusion strains interacted with the epithelial cells, we measured IL-8 levels produced by the epithelial cells. High levels of IL-8 were produced in all cases, indicating that the cag PAI was intact and that some portion of the H. pylori population interacted with the epithelial cell monolayer (data not shown). The levels of IL-8 produced from uninfected monolayers were not above background, and no IL-8 was detected in supernatants collected from the cag-ureB fusion strains alone (data not shown). This differential expression of ureB suggests that the promoter activities of the cag15- and cag21-ureB fusions are responsive to environmental cues experienced during coculturing with an epithelial cell monolayer.

FIG. 2.

Western analysis of the cag-ureB fusions incubated with and without HEp-2 epithelial cells. Protein samples from H. pylori strains adhering to HEp-2 cells and H. pylori strains alone were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to membranes for Western analysis. Protein bands were detected and visualized by using a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. The relative amounts of ICD and UreB were determined by densitometry. The raw data are noted below a subset of the Western blots. Loading differences were corrected for by using the ICD data. Changes in UreB levels observed with and without HEp-2 cells are reported as a fold increase in the amounts of UreB compared to ICD.

Colonization ability of cag-ureB fusions in mice.

To determine if the increase in ureB expression from the cag15-ureB and cag21-ureB fusion strains had in vivo significance, mouse-adapted strains (from strain M6; designated with the suffix “M”) containing these fusions were constructed and tested for their ability to colonize mice. The results (Table 3) indicated that while fusion strains 585M(cag1-ureB) and 585M(cag15-ureB) were able to colonize mice, they achieved a cell density that was 10-fold lower than that of the parent strain, M6, under the conditions used. These two strains differ widely in their levels of in vitro urease activity, expressing 50 and 5% of the activity seen in M6, respectively. Strain 585M(cag21-ureB), which produces 11% of the parental level of urease, twofold more than the in vitro level of expression of strain 585M(cag15-ureB), failed to colonize mice. Although it is not known how much urease activity is required for colonization, these results suggest that the in vitro expression of cag15-driven ureB is not equivalent to its in vivo expression.

TABLE 3.

Colonization of C57BL/6 mice with H. pylori strains

| Strain | No. of mice colonized/ no. tested | CFU/g (106) at 8 wk postinfectiona |

|---|---|---|

| M6 | 5/5 | 9.70 ± 4.20 |

| 412M | 0/5 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 585M(cag1-ureB) | 3/5 | 0.25 ± 0.22 |

| 585M(cag15-ureB) | 2/4 | 0.13 ± 0.13 |

| 585M(cag21-ureB) | 0/5 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

Reported as the mean and standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

The ureB expression vector developed in this work offers several advantages for the analysis of gene expression in H. pylori. Fusions of genes to ureB, constructed using this vector, are readily inserted in single copies at a neutral site on the H. pylori chromosome, thus avoiding polar effects on downstream genes. The normal copy of the gene being examined remains intact. The production of urease in the ΔureB reporter strain is absolutely dependent on the expression of ureB from a promoter(s) located within the sequence fused upstream of ureB; thus, the levels of urease activity provide a direct measure of the strength of a promoter fused to the ureB reporter. Perhaps the most unique feature of the urease expression system is that it can be used as a selectable trait, both in vitro and in vivo. Urease is the most abundant protein synthesized by H. pylori, and it has one of the lowest reported Km values (0.17 mM) of any urease (23), enabling it to function efficiently under conditions of low substrate concentrations. Several well-established assays facilitate quick and easy quantitative measurements of enzyme activity (3, 17).

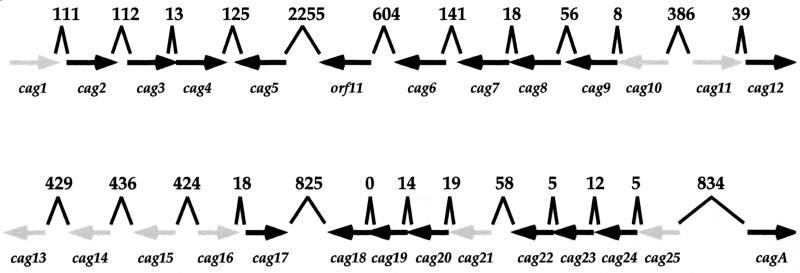

Little is known about the process of transcriptional regulation in H. pylori, particularly in relation to pathogenesis (5, 15, 25, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33). Since most H. pylori isolates from patients with gastric ulcers and cancers are classified as cagA-expressing type I strains, we used the urease reporter system to analyze gene expression in the cag PAI, 40-kb region of DNA which contains approximately 27 ORFs and which plays a key role in interactions between H. pylori and the gastric epithelium. Based on the known ORF sequence and organization within the cag PAI (Fig. 3), we selected nine noncoding intergenic DNA sequences that we considered likely to contain cag gene promoters for analysis using the urease reporter. One of the resulting cag-ureB fusion strains (cag1-ureB) gave high-level expression, while others (cag15-, cag16-, cag21-, and cag25-ureB) gave intermediate levels of expression. However, three strains (cag11-, cag13-, and cag14-ureB) gave levels of activity that were below that of strain 585. While these results indicate that the cloned fragments either lack a promoter or have a promoter that is not expressed under the growth conditions used, they may also imply that these sequences encode transcriptional terminators, which would suppress the background urease expression seen in strain 585.

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of the H. pylori cag PAI. Each cag gene is represented by an arrow pointing in the direction of transcription. The intergenic noncoding sequence between ORFs is noted in base pairs. Genes that were separated by more than 50 bp were targeted as potential promoter regions. The gray arrows represent genes whose 5′ noncoding sequences were chosen for study using the ureB transcriptional reporter.

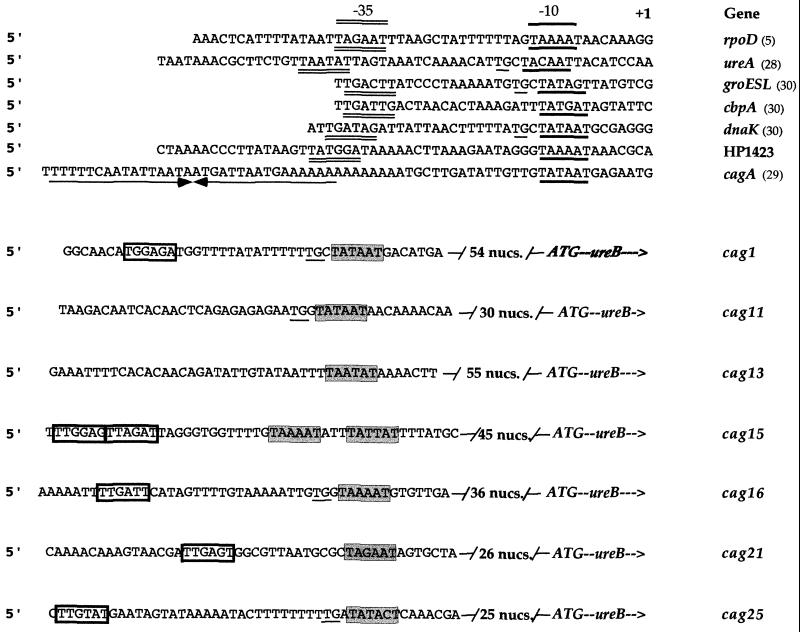

In an effort to identify DNA features that might be important for transcribing cag DNA, we compared the nine cag sequences with H. pylori promoters that had been previously mapped by primer extension or RNase I protection (Fig. 4). The cag sequences contain putative −10 and −35 regions, as well as other motifs that have been associated with promoter activity in H. pylori. Although five of the nine sequences that we examined have obvious homologies to both −10 and −35 sequences, the number of nucleotides between these putative sites varies; this variation may account for the observed differences in ureB expression. Shirai et al. (28) have reported that maximal levels of gene expression in H. pylori occur when spacing between the −10 and −35 sites is 17 or 18 nucleotides. In fact, the cag1 sequence, which gave the highest levels of urease activity when fused to ureB, contains highly conserved −10 and −35 sequences separated by 18 nucleotides (Fig. 4). All of the potential cag regulatory sequences identified here are 100% identical to the corresponding sequences present in the cag PAI of H. pylori strain J99. This finding suggests that phenotypic differences that these strains may show with regard to the cag PAI cannot obviously be attributed to differences in promoter structure.

FIG. 4.

Putative cag promoter sequences. Shown at the top is an alignment of seven previously characterized H. pylori promoter regions, illustrating the conserved −10 (thick line) and −35 (double underline) sites and the extended −10 (thin line) site. Putative promoter sequences were identified by sequence homology in seven of the nine cag sequences analyzed, which are shown at the bottom. Gray boxes indicate −10 sequences; underlining indicates extended −10 sequences; white boxes indicate −35 sequences. nucs., nucleotides.

Expression from all but two of the transcriptionally active cag regions was unaffected by interaction with epithelial cell monolayers. We conclude that most of the cag genes that we examined are expressed at some constitutive level under the conditions tested. The two exceptions were the fusions present in strains 585(cag15-ureB) and 585(cag21-ureB). Interestingly, although the putative cag15-ureB promoter region contains conserved −10 and −35 sequences separated by 18 nucleotides, it showed low promoter activity when 585(cag15-ureB) was grown under laboratory conditions. However, coculturing of this strain with epithelial cells resulted in a 14-fold increase in ureB expression from this putative promoter (Fig. 2). A similar observation was made for fusion strain 585(cag21-ureB), distinguishing the H. pylori cag PAI as an example of a type IV secretion system in which gene expression appears to be induced upon interaction with eukaryotic cells.

To determine if these observations had in vivo significance, we transferred the cag15- and cag21-ureB fusions into the mouse-adapted strain M6 and tested the ability of the M6 derivatives to colonize mice. Because of the low level of urease that these fusion strains produced during growth in bacteriological medium (Table 2) and because urease is essential for colonization (11, 12, 13, 19, 21, 23, 36), we expected that these strains would fail to colonize. Surprisingly, fusion strain 585M(cag15-ureB) colonized as well as 585M(cag1-ureB), another fusion strain, which produced much higher levels of urease. On the other hand, fusion strain 585M(cag21-ureB), which showed a similar increase in expression upon interaction with epithelial cells, failed to colonize mice (Table 3). The discrepancy among these observations underscores the significant differences between in vitro and in vivo situations, raising the intriguing possibility that the putative cag15 promoter may be induced in vivo.

cag15 does not appear to be part of an operon, based on its location within the cag gene cluster (Fig. 3). While there is a segment of DNA upstream of cag21 with promoter activity, the intergenic spacing between cag21 and the upstream coding sequence of cag22 is small, and the possibility exists that cag21 is also influenced by putative promoters located further upstream. The predicted protein product of cag15 (8) has low-level homology to a fimbrial assembly protein, FimB, from Dichelobacter nodosus and a type IV prepilin peptidase, encoded by pilD, from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The homology that Cag15 shares with PilD and FimB includes putative transmembrane regions. However, the critical residues in PilD that have been shown to be required for peptidase activity are not conserved in Cag15, suggesting that Cag15 probably does not act as a peptidase. Cag21 shares low-level homology with a flagellar motor switch protein, FliM, from Caulobacter crescentus and the toxin-coregulated pilus biosynthesis protein D from Vibrio cholerae.

Mutations in cag15 have not been reported. Experiments to delete cag15 in order to determine its effects on the epithelial cell induction of IL-8 or CagA secretion are currently under way. A null mutation has been made in cag21, and the resulting strain is unable to elicit IL-8 secretion or translocate CagA into a host cell. Although the roles of the Cag15 and Cag21 proteins in Cag function are presently unknown, their homologies with proteins involved in pilin-like biogenesis are intriguing and raise the possibility that there is an as-yet-unidentified pilin structure in type I H. pylori strains that contributes to the pathogenesis of the organism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the technical support provided by Anne Kane and her staff at the GRASP Digestive Disease Center at New England Medical Center, Boston, Mass., which is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIDDK grant P30DK34928). Joanne V. Gilbert is supported by NIH grant DK-3702. Support for K. A. Eaton is provided in part by Public Health Service grants R01 AI43643 and R29 DK-45340 from the NIH.

We also thank Dorothy Fallows, D. Scott Merrell, Matthew Waldor, and Anne Kane for critical review of the manuscript and thoughtful scientific discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akopyants N S, Clifton S W, Kersulyte D, Crabtree J E, Youree B E, Reece C A, Bukanov N O, Drazek E S, Roe B A, Berg D E. Analyses of the Cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:37–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asahi M, Azuma T, Ito S, Ito Y, Suto H, Nagai Y, Tsubokawa M, Tohyama Y, Maeda S, Omata M, Suzuki T, Sasakawa C. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein can be tyrosine phosphorylated in gastric epithelial cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:593–602. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.4.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes A R, Sugden J K. Comparison of colourimetric methods for ammonia determination. Pharm Acta Helv. 1990;65:258–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes W M. PCR amplification of up to 35-kb DNA with high fidelity and high yield from lambda bacteriophage templates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2216–2220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beier D, Spohn G, Rappuoli R, Scarlato V. Functional analysis of the Helicobacter pylori principal sigma subunit of RNA polymerase reveals that the spacer region is important for efficient transcription. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:121–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brosius J. Toxicity of an overproduced foreign gene product in Escherichia coli and its use in plasmid vectors for the selection of transcription terminators. Gene. 1984;27:161–172. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns D L. Biochemistry of type IV secretion. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:25–29. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Censini S, Lange C, Xiang Z, Crabtree J E, Ghiara P, Borodovsky M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. Cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14648–14653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crabtree J E, Covacci A, Farmery S M, Xiang Z, Tompkins D S, Perry S, Lindley I J, Rappuoli R. Helicobacter pylori induced interleukin-8 expression in gastric epithelial cells is associated with CagA positive phenotype. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:41–45. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crabtree J E, Farmery S M, Lindley I J, Figura N, Peichl P, Tompkins D S. CagA/cytotoxic strains of Helicobacter pylori and interleukin-8 in gastric epithelial cell lines. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:945–950. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.10.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eaton K A, Brooks C L, Morgan D R, Krakowka S. Essential role of urease in pathogenesis of gastritis induced by Helicobacter pylori in gnotobiotic piglets. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2470–2475. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2470-2475.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaton K A, Krakowka S. Avirulent, urease-deficient Helicobacter pylori colonizes gastric epithelial explants ex vivo. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:434–437. doi: 10.3109/00365529509093303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eaton K A, Krakowka S. Effect of gastric pH on urease-dependent colonization of gnotobiotic piglets by Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3604–3607. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3604-3607.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst P B, Crowe S E, Reyes V E. How does Helicobacter pylori cause mucosal damage? The inflammatory response. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(Suppl.):S35–S42. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)80009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forsyth M H, Cover T L. Mutational analysis of the vacA promoter provides insight into gene transcription in Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2261–2266. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2261-2266.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert J V, Ramakrishna J, Sunderman F W, Jr, Wright A, Plaut A G. Protein Hpn: cloning and characterization of a histidine-rich metal-binding polypeptide in Helicobacter pylori and Helicobacter mustelae. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2682–2688. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2682-2688.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon S A, Fleck A, Bell J. Optimal conditions for the estimation of ammonium by the Berthelot reaction. Ann Clin Biochem. 1978;15:270–275. doi: 10.1177/000456327801500164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang J, O'Toole P W, Doig P, Trust T J. Stimulation of interleukin-8 production in epithelial cell lines by Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1732–1738. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1732-1738.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karita M, Tsuda M, Nakazawa T. Essential role of urease in vitro and in vivo Helicobacter pylori colonization study using a wild-type and isogenic urease mutant strain. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;21(Suppl. 1):S160–S163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuipers E J. Helicobacter pylori and the risk and management of associated diseases: gastritis, ulcer disease, atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11(Suppl. 1):71–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.11.s1.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGee D J, May C A, Garner R M, Himpsl J M, Mobley H L. Isolation of Helicobacter pylori genes that modulate urease activity. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2477–2484. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2477-2484.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGowan C C, Cover T L, Blaser M J. Helicobacter pylori and gastric acid: biological and therapeutic implications. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:926–938. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8608904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mobley H L, Island M D, Hausinger R P. Molecular biology of microbial ureases. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:451–480. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.3.451-480.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odenbreit S, Puls J, Sedlmaier B, Gerland E, Fischer W, Haas R. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science. 2000;287:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmitz A, Josenhans C, Suerbaum S. Cloning and characterization of the Helicobacter pylori flbA gene. which codes for a membrane protein involved in coordinated expression of flagellar genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:987–997. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.987-997.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Segal E D, Cha J, Lo J, Falkow S, Tompkins L S. Altered states: involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14559–14564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma S A, Tummuru M K R, Miller G G, Blaser M J. Interleukin-8 response of gastric epithelial cell lines to Helicobacter pylori stimulation in vitro. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1681–1687. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1681-1687.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shirai M, Fujinaga R, Akada J K, Nakazawa T. Activation of Helicobacter pylori ureA promoter by a hybrid Escherichia coli-H. pylori rpoD gene in E. coli. Gene. 1999;239:351–359. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00389-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spohn G, Beier D, Rappuoli R, Scarlato V. Transcriptional analysis of the divergent cagAB genes encoded by the pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:361–372. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5831949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spohn G, Scarlato V. The autoregulatory HspR repressor protein governs chaperone gene transcription in Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:663–674. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spohn G, Scarlato V. Motility of Helicobacter pylori is coordinately regulated by the transcriptional activator FlgR, an NtrC homolog. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:593–599. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.593-599.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stein M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Helicobacter pylori CagA antigen after cag-driven host cell translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1263–1268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suerbaum S, Brauer-Steppkes T, Labigne A, Cameron B, Drlica K. Topoisomerase I of Helicobacter pylori: juxtaposition with a flagellin gene (flaB) and functional requirement of a fourth zinc finger motif. Gene. 1998;210:151–161. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Svanborg C, Godaly G, Hedlund M. Cytokine responses during mucosal infections: role in disease pathogenesis and host defence. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:99–105. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomb J F, White O, Kerlavage A R, Clayton R A, Sutton G G, Fleischmann R D, Ketchum K A, Klenk H P, Gill S, Dougherty B A, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness E F, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak H G, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzegerald L M, Lee N, Adams M D, Venter J C, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsuda M, Karita M, Mizote T, Morshed M G, Okita K, Nakazawa T. Essential role of Helicobacter pylori urease in gastric colonization: definite proof using a urease-negative mutant constructed by gene replacement. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;6(Suppl. 1):S49–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tummuru M K, Sharma S A, Blaser M J. Helicobacter pylori picB, a homologue of the Bordetella pertussis toxin secretion protein, is required for induction of IL-8 in gastric epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:867–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.18050867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Roos K P, Taylor D E. Transformation of Helicobacter pylori by chromosomal metronidazole resistance and by a plasmid with a selectable chloramphenicol resistance marker. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2485–2493. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-10-2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winans S C, Burns D L, Christie P J. Adaptation of a conjugal transfer system for the export of pathogenic macromolecules. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:64–68. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)81513-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]