Abstract

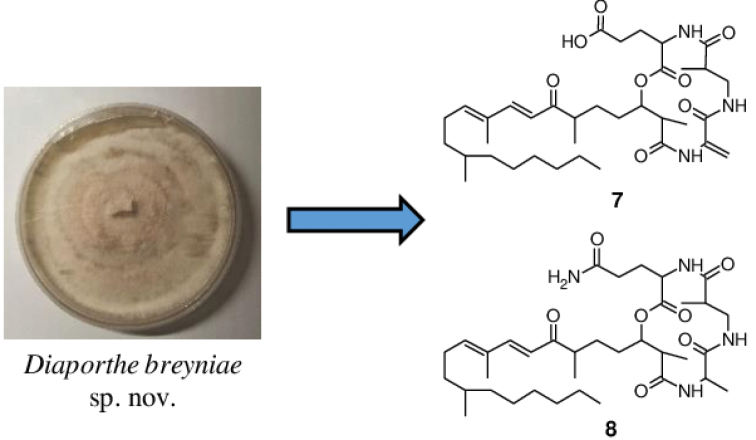

During the course of a study on the biodiversity of endophytes from Cameroon, a fungal strain was isolated. A multigene phylogenetic inference using five DNA loci revealed that this strain represents an undescribed species of Diaporthe, which is introduced here as D.breyniae. Investigation into the chemistry of this fungus led to the isolation of two previously undescribed secondary metabolites for which the trivial names fusaristatins G (7) and H (8) are proposed, together with eleven known compounds. The structures of all of the metabolites were established by using one-dimensional (1D) and two-dimensional (2D) Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopic data in combination with High-Resolution ElectroSpray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (HR-ESIMS) data. The absolute configuration of phomopchalasin N (4), which was reported for the first time concurrently to the present publication, was determined by analysis of its Rotating frame Overhauser Effect SpectroscopY (ROESY) spectrum and by comparison of its Electronic Circular Dichroism (ECD) spectrum with that of related compounds. A selection of the isolated secondary metabolites were tested for antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities, and compounds 4 and 7 showed weak antifungal and antibacterial activity. On the other hand, compound 4 showed moderate cytotoxic activity against all tested cancer cell lines with IC50 values in the range of 5.8–45.9 µM. The latter was found to be less toxic than the other isolated cytochalasins (1–3) and gave hints in regards to the structure-activity relationship (SAR) of the studied cytochalasins. Fusaristatin H (8) also exhibited weak cytotoxicity against KB3.1 cell lines with an IC50 value of 30.3 µM.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Antimicrobial, cytotoxicity, Diaporthe , endophytic fungi, one new species, secondary metabolites

Introduction

The genus Diaporthe (including their asexual states, which were previously referred to as Phomopsis spp.) comprises several hundred species mostly attributed to plant pathogens, non-pathogenic endophytes, or saprobes in terrestrial host plants (Chepkirui and Stadler 2017; Xu et al. 2021). The term “endophytic fungi” herein refers to a group of microorganisms that inhabit the internal parts of a plant, but typically cause no apparent symptoms of disease in the host plant (Stone et al. 2000). Fungal endophytes belonging to the genus Diaporthe have been widely investigated by natural product chemists and have proven to be a rich source of novel organic compounds with interesting biological activities and a high level of chemical diversity (Chepkirui and Stadler 2017). They have been shown to predominantly produce polyketides, but PKS/NRPS-derived hybrids like cytochalasins have also been frequently reported from Diaporthe (Jouda et al. 2016; Chepkirui and Stadler 2017). Initially, cytochalasins have been discovered for their potent cytotoxic effects, which are due to their interference with the actin cytoskeleton (Yahara et al. 1982) and have been targeted primarily as anticancer agents. However, not all cytochalasins are equally active on actin (Kretz et al. 2019), and they were even found to significantly inhibit biofilm formation of an important human pathogenic bacterium (Yuyama et al. 2018). The current paper supports the activities of an interdisciplinary consortium that aims at exploring the chemical space of the cytochalasins, in order to establish structure-activity relationships (SAR) and systematically explore their utility for application in various medical applications. Owing to the structural complexity of cytochalasins, their total synthesis remains tedious and requires several reaction steps with relatively low final yields (Zaghouani et al. 2016; Long et al. 2018). Moreover, most of the compounds that were reported previously have not been studied thoroughly for their biological effects; hence, it is worth obtaining them from the fungal producer organisms by de novo isolation and characterization.

We have recently isolated and studied a new endophytic species of Diaporthe from the twigs of Breyniaoblongifolia. We noted prominent antimicrobial effects in the extracts derived from this strain and decided to study its secondary metabolites. The current paper includes the description of the new species D.breyniae sp. nov., and reports details on the isolation and structure elucidation of its secondary metabolites, as well as an account of their biological properties.

Materials and methods

Fungal isolation

The fungus was isolated from fresh twigs of an apparently healthy plant belonging to Breyniaoblongifolia in Kala Mountain (Yaoundé, Cameroon). Fresh twigs (5 × 5 cm length) of Breyniaoblongifolia were thoroughly washed with running tap water, then disinfected in 75% ethanol for 1 min, in 3% sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) for 10 min, and finally in 75% ethanol for 30 s. These twigs were then rinsed three times in sterile distilled water and dried on sterile tissue paper under a laminar flow hood. Small segments of the twigs were transferred to Petri dishes containing potato dextrose agar (PDA, HiMedia, Mumbai, India) supplemented with 100 mg/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin sulphate and incubated at 28 °C. After 10 days, fungal colonies were examined and hyphal tips were transferred to PDA using a sterile needle and incubated at 28 °C.

Herbarium type material and the ex-type strain of the new species are maintained at the collection of the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute (CBS), Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Phenotypic study

For cultural characterization, the isolate was grown for 15 days on malt extract agar (MEA; HiMedia, Mumbai, India), oatmeal agar (OA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), and PDA at 21 °C in darkness (Guarnaccia et al. 2018). Color notations in parentheses are taken from the color chart of The Royal Horticultural Society London (1966). The fungus was grown in 2% tap water agar supplemented with sterile pine needles (PNA; Smith et al. 1996) to induce sporulation.

Molecular study

DNA of the fungus was extracted and purified directly from colony growing in yeast malt agar (YM agar; malt extract 10 g/L, yeast extract 4 g/L, D-glucose 4 g/L, agar 20 g/L, pH 6.3 before autoclaving), following the Fungal gDNA Miniprep Kit EZ-10 Spin Column protocol (NBS Biologicals, Cambridgeshire, UK). The amplification of the ITS, cal, his3, tef1 and tub2 loci were performed according to White et al. (1990) (ITS), Carbone and Kohn (1999) (cal and tef1), Glass and Donaldson (1995) (his3 and tub2) and Crous et al. (2004) (his3). PCR products were purified and sequenced using Sanger Cycle Sequencing method at Microsynth Seqlab GmbH (Göttingen, Germany), and the consensus sequences obtained employing the de-novo assembly feature of the Geneious 7.1.9 (http://www.geneious.com, Kearse et al. 2012) program package using a forward and reverse read.

In order to restrict the phylogenetic inference to the relevant species to compare with, a first phylogenetic analysis was carried out based on the combination of the five loci sequences (ITS, cal, his3, tef1, tub2) of our isolate and a selection of sequence data derived from type material or reference strains from all Diaporthe spp. available in NCBI. Each locus was aligned separately using MAFFT v. 7.017 (algorithm G-INS-I, gap open penalty set to 1.53, offset value 0.123 with options set for automatically determining sequence direction automatically and more accurately) as available as a Geneious 7.1.9 plugin (Katoh and Standley 2013) and manually adjusted in MEGA v. 10.2.4 (Kumar et al. 2018). Alignment errors were minimized by using gblocks (Talavera and Castresana 2007); with options set for allowed block positions ‘with half’, minimum length of a block set to 5 and a maximum of 10 contiguous nonconserved positions) and concatenated by employing the phylosuite v 1.2.2 program package (Zhang et al. 2020). Maximum-Likelihood tree inference followed using IQTree V2.1.3 (Minh et al. 2020) preceded by calculation and automatic selection of the appropriate nucleotide exchange model using ModelFinder (Chernomor et al. 2016; Kalyaanamoorthy et al. 2017) based on Bayesian inference criterion. Bootstrap support was calculated by parallelizing 10 independent maximum-likelihood (ML) tree searches with 100 bootstrap replicates each to minimize computational burden. The total 1000 bootstrap replicates were consequently mapped onto the ML tree with the best (highest) ML score. After selection of the core group related to the sequences derived from D.breyniae sp. nov., a second phylogenetic analysis was performed including all five sequenced loci, using D.amygdaliCBS 126679T and D.eresCBS 138594T as outgroups. Sequence alignment and curation steps were identical, with exemption of a manual curation instead of employing automatic filtering for misaligned alignment sections using gblocks. ML trees using the supermatrix and single loci, respectively, were inferred using IQTree 2.1.3 with ModelFinder to determine optimal substitution models for each loci and partition, using 1000 bootstrap replicates to assign statistical support. The clade in which the sequences of the novel strain clustered, was checked visually for congruence among the single locus trees. Concurrently, a second tree was inferred following a Bayesian approach using MrBayes 3.2.7a (Ronquist et al. 2012) with nucleotide substitution models previously determined using PartitionFinder2 (Lanfear et al. 2016, options set for unlinked partitions, BIC, restricting models for Bayesian inference) and concatenated in Phylosuite V.1.2.2. Bayesian inference was done in Mr. Bayes v. 3.2.7 (Ronquist et al. 2012), using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) with four incrementally heated chains (temperature parameter set to 0.15), starting from a random tree topology. Generations were set to 100.000.000 with convergence controlled by average standard deviation of split frequencies arriving below 0.01. Trees were sampled every 1000 generations with the first 25% of saved trees treated as “burn-in” phase. Posterior probabilities were mapped using the remaining trees. Bootstrap support (bs) ≥ 70 and posterior probability values (pp) ≥ 0.95 were considered significant (Alfaro et al. 2003). The sequences generated in this study are deposited in GenBank (Table 1) and the alignments used in the phylogenetic analysis are included in Supplementary material. Sequences retrieved from GenBank are indicated in Table 1 and Suppl. material 1: S4.

Table 1.

Isolated and reference strains of Diaporthe included in this study. # GenBank accession numbers in bold were newly generated in this study. The taxonomic novelty is indicated in bold italic.

1BRIP: Queensland Plant Pathology Herbarium, Brisbane, Australia; CBS: Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands; CGMCC: Chinese General Microbiological Culture Collection Center, Beijing, China; COAD: Culture Collection of Octávio de Almeida Drumond. Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Brasil; FAU: Isolates in culture collection of Systematic Mycology and Microbiology Laboratory; ICMP: International Collection of Micro-organisms from Plants, Auckland, New Zealand; KUMCC: Kumming Institute of Botany, Kumming, China; LGMF, Laboratório de Genética de Microrganismos (LabGeM) culture collection, at the Federal University of Paraná, Brazil; MAFF: Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Tokyo, Japan; MFLUCC: Mae Fah Luang University Culture Collection, Chiang Rai, Thailand; SAUCC: Shandong Agricultural University Culture Collection, Shandong, China; STE-U: Department of Plant Pathology, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa; URM: Culture Collection at the Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil; VTCC: Vietnam Type Culture Collection, Center of Biotechnology, Vietnam National University, Hanoi, Vietnam; ZHKUCC: Culture Collection of Zhongkai University of Agriculture and Engineering, Guangzhou, China. T indicates type material. 2ITS: internal transcribed spacers and intervening 5.8S nrDNA; tub2: partial β-tubulin gene; his3: partial histone H3 gene; tef1: partial elongation factor 1-alpha gene; cal: partial calmodulin gene.

Chromatography and spectral methods

Electrospray ionization mass (ESIMS) spectra were recorded with an UltiMate 3000 Series uHPLC (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltman, MA, USA) utilizing a C18 Acquity UPLC BEH column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 µm; Waters, Milford, USA) connected to an amaZon speed ESI-Iontrap-MS (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). HPLC parameters were set as follows: solvent A: H2O + 0.1% formic acid, solvent B: acetonitrile (ACN) + 0.1% formic acid, gradient: 5% B for 0.5 min increasing to 100% B in 19.5 min, then isocratic condition at 100% B for 5 min, a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min, and Diode-Array Detection (DAD) of 210 nm and 190–600 nm.

High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HR-ESIMS) spectra were recorded with an Agilent 1200 Infinity Series HPLC-UV system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA; column 2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 µm, C18 Acquity UPLC BEH (waters), solvent A: H2O +0.1% formic acid; solvent B: ACN + 0.1% formic acid, gradient: 5% B for 0.5 min increasing to 100% B in 19.5 min and then maintaining 100% B for 5 min, flow rate 0.6 mL/min, UV/Vis detection 200–640 nm) connected to a MaXis ESI-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker) (scan range 100–2500 m/z, capillary voltage 4500 V, dry temperature 200 °C).

Optical rotations were recorded in methanol (Uvasol, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) by using an Anton Paar MCP-150 polarimeter (Seelze, Germany) at 20 °C. UV/Vis spectra were recorded using methanol (Uvasol, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with a Shimadzu UV/Vis 2450 spectrophotometer (Kyoto, Japan). ECD spectra were obtained on a J-815 spectropolarimeter (JASCO, Pfungstadt, Germany). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded at a temperature of 298 K with an Avance III 500 spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA/USA, 1H-NMR: 500 MHz and 13C-NMR: 125 MHz) and an Ascend 700 spectrometer with 5 mm TCI cryoprobe (Bruker, Billerica, MA/USA, 1H-NMR: 700 MHz and 13C-NMR: 175 MHz).

Small-scale fermentation and extraction

The fungus was cultivated in three different liquid media (YM 6.3 medium: 10g/mL malt extract, 4g/mL, yeast extract, 4g/mL, D-glucose and pH = 6.3, Q6 ½ medium: 10 g/mL glycerin, 2.5 g/mL D-glucose, 5 g/mL cotton seed flour and pH = 7.2; ZM ½ medium: 5 g/mL molasses, 5 g/mL oatmeal, 1.5 g/mL D-glucose, 4 g/mL saccharose, 4 g/mL mannitol, 0.5 g/mL edamin, ammonium sulphate 0.5 g/mL, 1.5 g/mL calcium carbonate and pH = 7.2) (Chepkirui et al. 2016). A well-grown 14-day-old mycelial culture grown on YM agar was cut into small pieces using a cork borer (7mm), and five pieces used for inoculation of 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 200 mL of media. The cultures were incubated at 23 °C on a rotary shaker at 140 rpm. The growth of the fungus was monitored by checking the amount of free glucose daily using Medi-Test glucose strips (Macherey Nagel, Düren, Germany). The fermentation was terminated three days after glucose depletion and the biomasses and supernatants were separated via vacuum filtration. Afterwards, the supernatants were extracted with equal amount of ethyl acetate (200 mL) and filtered through anhydrous sodium sulphate. The resulting ethyl acetate extracts were evaporated to dryness in vacuo (Rotary Evaporator: Heidolph Instruments GmbH & Co. KG, Schwabach, Germany; pump: Vacuubrand GmbH & Co. KG, Wertheim am Main, Germany) at 40 °C. The mycelia were extracted with 200 mL of acetone in an ultrasonic bath (Sonorex Digital 10 P, Bandelin Electronic GmH & Co. KG, Berlin, Germany) at 40 °C for 30 min, filtered and the organic phase evaporated. The volume of the remaining aqueous phase was adjusted with an equal amount of distilled water and subjected to the same procedure as described for the supernatants.

The small-scale cultivation of Diaporthebreyniae was also carried out on YM agar medium and rice solid medium (BRFT, brown rice 28 g as well as 0.1 L of base liquid (yeast extract 1 g/L, di-sodium tartrate di-hydrate 0.5 g/L, KH2PO4 0.5 g/L) (Becker et al. 2020a). Briefly, the fungus was grown on a YM agar plate and the mycelia was extracted with 200 mL of ethyl acetate in an ultrasonic water bath at 40 °C for 30 min, filtered and the filtrate evaporated to dryness in vacuo at 40 °C. For BFRT medium, three small pieces of the mycelial culture grown on а YM agar plate were inoculated into a 250 ml Erlenmeyer flask containing 100 mL of YM 6.3 medium. The seed culture was incubated at 23 °C under shake condition at 140 rpm. After 5 days, 10 mL of this seed culture were transferred to a 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing BRFT medium and incubated for 28 days at 23 °C. Afterwards, extraction of the culture was performed following the same procedure as above mentioned for the mycelia obtained from the liquid cultures.

Scale-up fermentation in shake flask batches and extraction

Preliminary results obtained from small-scale screening suggested that the fungus grew and produced best in ZM ½ medium (Suppl. material 1: Figs S1, S2). Moreover, the extracts obtained from the fungal culture in ZM ½ were active against Bacillussubtilis and Mucorplumbeus. Therefore, this medium was selected for scale-up fermentation. Three well-grown 14-day-old YM agar plate of the mycelial culture were cut into small pieces using a 7 mm cork borer and 5 pieces inoculated in 10 × 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 200 mL of ZM ½ medium. The culture was incubated at 23 °C on a rotary shaker at 140 rpm for 11 days. Fermentation was aborted 3 days after the depletion of free glucose. The mycelia and supernatant from the batch fermentation were separated via vacuum filtration. The mycelia were extracted with 3 × 500 mL of acetone in an ultrasonic water bath at 40 °C for 30 min. The extracts were combined and the solvent evaporated in vacuo (40 °C). The remaining water phase was subjected to the same procedure as previously described for the mycelial fraction in small-scale extraction, repeating the extraction step 3 times, yielding 955 mg dark brown solid-like extract. The supernatant (2 L) was extracted with equal amount of ethyl acetate and filtered through anhydrous sodium sulphate. The resulting ethyl acetate extract was evaporated to dryness in vacuo to afford 251 mg of extract.

Isolation of secondary metabolites

The mycelial and the supernatant extracts from shake flask batch fermentation dissolved in methanol were centrifuged by means of a centrifuge (Hettich Rotofix 32 A, Tuttlingen, Germany) for 10 min at 4000 rpm. Afterwards, the mycelia and supernatant extracts were fractionated separately using preparative reverse phase HPLC (Büchi, Pure C-850, 2020, Switzerland). VP Nucleodur 100-5 C18ec column (150 × 40 mm, 7 µm: Machery-Nagel, Düren, Germany) was used as stationary phase. Deionized water (Milli-Q, Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany) supplemented with 0.1% formic acid (FA) (solvent A) and acetonitrile (ACN) with 0.1% FA (solvent B) were used as the mobile phase. The elution gradient used for fractionation was 5–35% solvent B for 20 min, 35–80% B for 30 min, 80–100% B for 10 min and thereafter isocratic condition at 100% solvent B for 15 min. The flow rate was set to 30 mL/min and UV detection was carried out at 210, 320 and 350 nm. For the supernatant extract, 13 fractions (F1-F13) were selected according to the observed peaks, and further analysis of the fractions using HPLC-MS revealed that four of the obtained fractions constituted pure compounds. Using the same elution conditions as mentioned, the mycelia extract afforded 17 fractions (F1–F17) selected from the observed peaks. HPLC-MS analysis of the obtained fractions revealed that seven fractions constituted pure compounds. The compounds obtained from mycelial and supernatant extracts were combined according to their respective HPLC-ESIMS retention time and molecular weight. Compound 1 (55.2 mg, tR = 7.80 min) was obtained from both the mycelium and supernatant extracts as well as compounds 2 (10.9 mg, tR = 6.27 min), 3 (2.6 mg, tR = 11.42 min) and 4 (5.6 mg, tR = 9.49 min). Compounds 5 (3.6 mg, tR = 13.46 min), 11 (0.7 mg, tR = 12.11 min) and 12 (2.0 mg, tR = 3.83 min) were only isolated from the mycelial extract. Fractions F4 from both the mycelium and supernatant extracts were combined and purified using an Agilent Technologies 1200 Infinity Series semi-preparative HPLC instrument (Waldbronn, Germany). The elution gradient used was 20–30% solvent B for 5 min followed by isocratic condition at 30% B for 25 min and thereafter increased gradient from 30–100% B for 5 min. VP Nucleodur 100-5 C18ec column (250 × 10 mm, 5 µm: Machery-Nagel, Düren, Germany) was used as stationary phase and the flow rate was 3 mL/min. These fractions afforded compound 13 (2.34 mg, tR = 5.13 min). Fractions F13 and F14 from the mycelial extract were combined with F12 from the supernatant as they contained the same compounds. The pooled fractions were purified by preparative reverse phase HPLC (Büchi, Pure C-850, 2020, Switzerland). VP Nucleodur 100-5 C18ec column (250 × 21 mm, 5 µm: Machery-Nagel, Düren, Germany) was used as stationary phase with a flow rate of 15 mL/min and an elution gradient of 5–70% solvent B for 5 min, followed by isocratic conditions at 70% B for 25min, and thereafter increased gradient from 70–100% B for 5 min. These fractions afforded compound 9 (10.5 mg, tR = 13.02 min) and sub-fraction G1. Sub-fraction G1 was further purified using an Agilent Technologies 1200 Infinity Series semi-preparative HPLC with the elution gradient starting from 65–70% B for 5 min followed by isocratic condition at 70% B for 25 min and thereafter increased gradient from 70–100% B for 5 min to afford compounds 7 (1.4 mg, tR = 13.91 min) and 8 (0.52 mg, tR = 13.56 min). Fraction F15 from the mycelium were also purified using the same instrument and same elution conditions as described for sub-fraction G1. This fraction afforded compounds 6 (1.1 mg, tR = 14.02 min) and 10 (1.7 mg, tR = 13.58 min).

Note: The given retention times were obtained from HPLC-ESIMS following the HPLC parameters as described in the general experimental procedures.

Antimicrobial assay

The antifungal and antibacterial activities (Minimum Inhibition Concentration, MIC) of all extracts obtained from small-scale fermentation were determined in serial dilution assays as described previously (Chepkirui et al. 2016; Becker et al. 2020b) against Bacillussubtilis, Candidatenuis, Escherichiacoli and Mucorplumbeus. The assays were carried out in 96-well microtiter plates in YM 6.3 medium for filamentous fungi and yeast and MHB medium (Müller-Hinton Broth: SN X927.1, Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) for bacteria. Starting concentration for all extracts were 300 µg/mL. In addition, the antimicrobial activity of the isolated pure compounds was also assessed as previously described (Matio Kemkuignou et al. 2020) against a panel of bacteria and fungi including Pichiaanomala DSM 6766, Schizosaccharomycespombe DSM 70572, Mucorhiemalis DSM 2656, Candidaalbicans DSM 1665, and Rhodotorulaglutinis DSM 10134 for fungal microorganisms, Bacillussubtilis DSM 10, Staphylococcusaureus DSM 346 and Mycobacteriumsmegmatis ATCC 700084 for Gram-positive bacteria, Acinetobacterbaumannii DSM 30008, Chromobacteriumviolaceum DSM 30191, Escherichiacoli DSM 1116 and Pseudomonasaeruginosa for Gram-negative bacteria. Starting concentration for tested compounds was adjusted to 66.7 µg/mL.

Cytotoxicity assay

The in vitro cytotoxicity (IC50) of the isolated metabolites against several mammalian cell lines (human endocervical adenocarcinoma KB 3.1, mouse fibroblasts L929, squamous cancer A431, breast cancer MCF-7, lung cancer A549, ovary cancer SK-OV-3 and prostate cancer PC-3) was determined by colorimetric tetrazolium dye MTT assay using epothilone B as a positive control in accordance to our previously reported experimental procedure (Becker et al. 2020b).

Results and discussion

Phylogenetic study

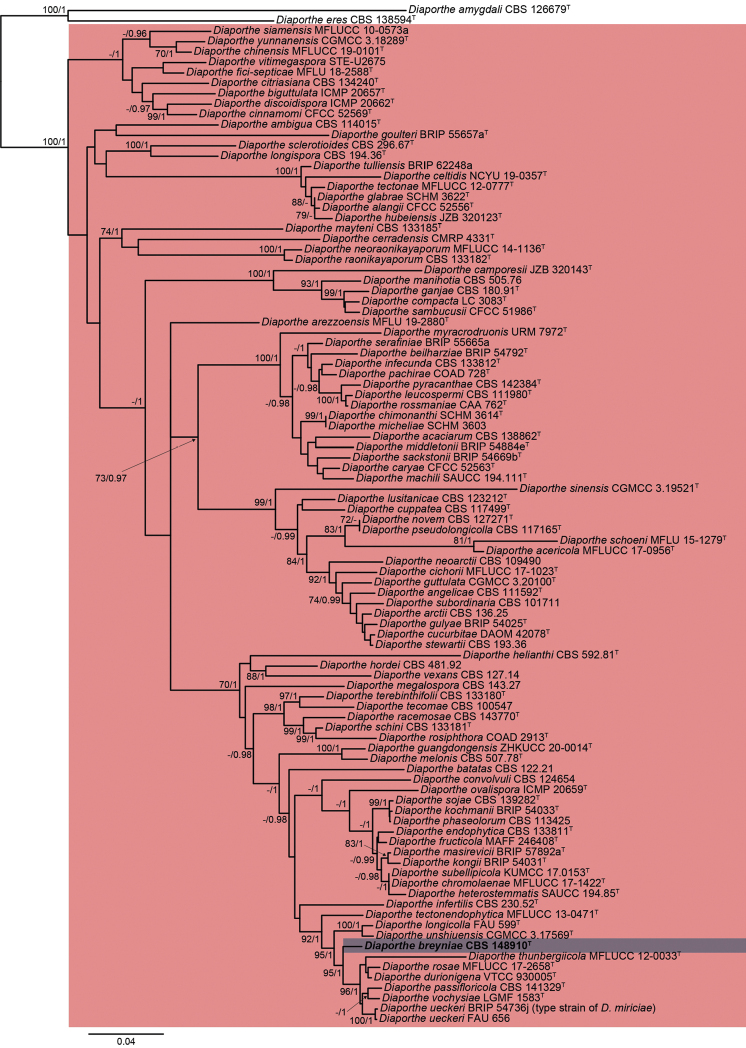

The lengths of the fragments of the first phylogenetic inference using the five previously mentioned loci used in the combined dataset for the tree including all Diaporthe spp. were 454 bp (ITS), 318 bp (cal), 296 bp (his3), 153 bp (tef1) and 487 bp (tub2), comprising in total 341 taxa. The length of the final alignment was 1708 bp. The inferred phylogeny with the best maximum likelihood score with bootstrap support (bs) values mapped onto branch bipartitions is shown in Suppl. material 1: Fig. S100. The here studied strain was located in a clade with 92% bs including 341 taxa, including species belonging to the D.sojae complex. A second molecular phylogeny was inferred including sequences of the same loci, but restricted to the aforementioned clade, including 98 taxa. The lengths of the fragments used in the combined dataset were 572 bp (ITS), 449 bp (cal), 373 bp (his3), 452 bp (tef1) and 862 bp (tub2), totaling 2708 bp for the final alignment. Fig. 1 shows the consensus ML tree, including bs and Bayesian posterior probability (pp) values at the nodes. Our strain was located in an independent branch distant from other species of Diaporthe, demonstrating that this represented a new species, which is introduced here as D.breyniae. Unfortunately, the new species lacked sporulation in all media tested in the present study. Therefore, the introduction of it is based only on molecular data.

Figure 1.

ML (lnL = -28100.2019) phylogram obtained from the combined ITS, cal, his3, tef1 and tub2 sequences of our strain and related Diaporthe spp. DiaportheamygdaliCBS 126679T and D.eresCBS 138594T were used as an outgroup. Bootstrap support values ≥ 70/Bayesian posterior probability scores ≥ 0.95 are indicated along branches. Branch lengths are proportional to distance. New taxon is indicated in bold. Type material of the different species is indicated with T.

Taxonomy

. Diaporthe breyniae

Y. Marín & C. Lamb. sp. nov.

F343AAD4-1A66-5164-A82C-57BFBA0E28B9

843243

Etymology.

Name refers to the host genus that this fungus was isolated from, Breynia.

Description.

Not sporulated. Diaporthebreyniae differs from its closest phylogenetic neighbour, D.durionigena by unique fixed alleles in three loci based on alignments of the separate loci included in the supplementary material: ITS positions 93 (indel), 159 (G), 436 (T), 437 (C), 451 (G), 453 (A), 485 (C); tef1 positions 46 (A), 62 (G), 80 (T), 100 (G), 146 (T), 274 (indel), 304 (A), 310 (G), 313 (C), 339 (T), 343 (A), 385 (G); tub2 positions 393 (A), 402 (indel), 426 (A), 565 (C), 675 (T), 713 (G), 770 (T).

Culture characters.

Colonies on PDA reaching 55–70 mm in 2 weeks, greyed yellow (161A) with a white ring and transparent margins, lobate, cottony, raised, margins filamentous to fimbriate; reverse greyed yellow (161A–D) with transparent margins. Colonies on MEA covering the surface of the Petri dish in 2 weeks, white with greyed yellow center (161A), velvety to cottony, flat to raised in some zones, margins filamentous to fimbriate; reverse greyed yellow (162A–B). Colonies on OA covering the surface of the Petri dish in 2 weeks, white with greyed yellow ring (161D), velvety, flat, margins filamentous to fimbriate; reverse grey brown (199D).

Specimen examined.

Cameroon, Kala mountain, on leaves of Breyniaoblongifolia, 02 Jan. 2019, S.C.N. Wouamba (holotype: CBS H-24920, culture ex-type CBS 148910 = STMA 18284).

Notes.

Diaporthebreyniae is introduced based only on molecular data since sporulation could not be induced in any media used. This species is located in a well-supported clade (97% bs / 1 pp) together with D.durionigena, D.passifloricola, D.rosae, D.thunbergiicola, D.ueckeri and D.vochysiae. The latter species has only been reported from Brazil occurring on different hosts, i.e. Stryphnodendronadstringens (Fabaceae, Fabales) and Vochysiadivergens (Vochysiaceae, Myrtales) (Noriler et al. 2019). Diaporthedurionigena has been only isolated from Duriozibethinus (Malvaceae, Malvales) in Vietnam (Crous et al. 2020, 2021). Diaporthepassifloricola has been found on Passiflorafoetida (Passifloraceae, Malpighiales) and Citrus spp. (Rutaceae, Sapindales) in China and Malaysia (Crous et al. 2016; Chaisiri et al. 2021; Dong et al. 2021), while D.rosae has been isolated from Rosa sp. (Rosaceae, Rosales), Magnoliachampaca (Magnoliaceae, Magnoliales) and Sennasiamea (Fabaceae, Fabales) in Thailand (Perera et al. 2018; Wanasinghe et al. 2018). Diaportheueckeri (syn. D.miriciae, Gao et al. 2016) has been reported in Australia, Colombia and the USA, on Cucumismelo (Cucurbitaceae, Cucurbitales), Glycinemax (Fabaceae, Fabales) and Helianthusannuus (Asteraceae, Asterales) (Thompson et al. 2015; Udayanga et al. 2015; López-Cardona et al. 2021). Diaporthethunbergiicola has been only isolated from Thunbergialaurifolia (Acanthaceae, Lamiales) in Thailand (Liu et al. 2015). The new species D.breyniae is the only of these species reported on Breynia (Phyllanthaceae, Malpighiales) in Africa. In fact, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first species of Diaporthe reported in Cameroon and occurring in this host.

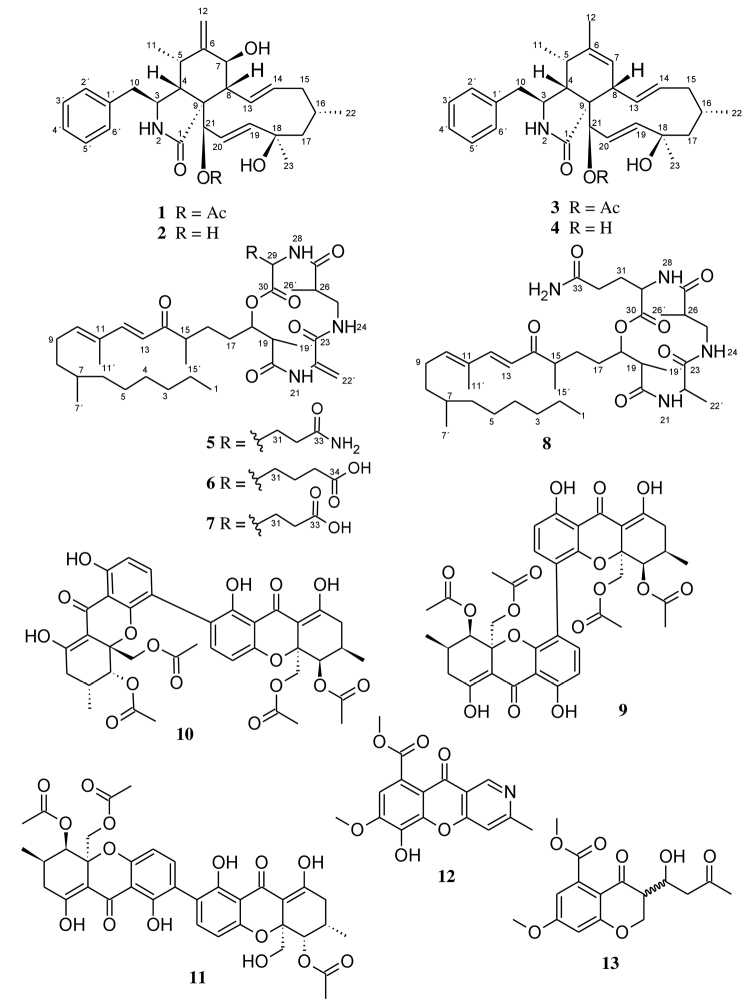

Structure elucidation of compounds 1–13

Cultivation trials carried out on Diaporthebreyniae in different culture media including YM 6.3, Q6 ½, ZM ½, rice solid and YM agar highlighted its potential for producing secondary metabolites. During antimicrobial screening of the extracts, the fungus revealed significant antifungal and antibacterial activity against Mucorhiemalis and Bacillussubtilis respectively, especially when cultured in ZM ½ medium, encouraging more detailed examination. Investigation into the chemistry of Diaporthebreyniae led to the isolation of two new secondary metabolites (7, 8) together with eleven known compounds (1–4, 5, 6, 9–13) from the EtOAc extracts of a 2 L scale-up ZM ½ liquid medium of the fungus (Fig. 2). The structure elucidation of 1–13 was determined by detailed spectroscopic analysis of their 1D and 2D NMR data in combination with their HR-ESIMS data.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of compounds 1–13 isolated from Diaporthebreyniae.

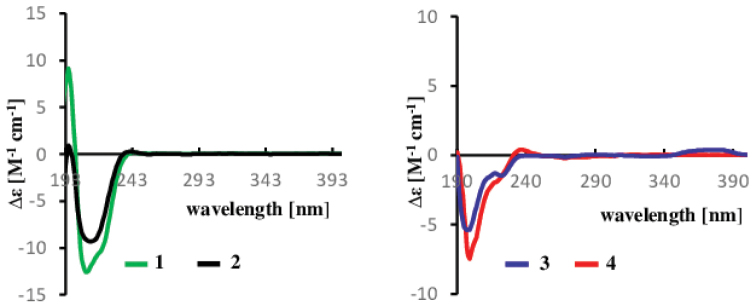

HR-ESI(+)MS and NMR spectroscopic analysis identified compounds 1–3 as cytochalasin H (1) (Suppl. material 1: Figs S3–S10) (Beno et al. 1977; Shang et al. 2017), deacetylcytochalasin H or cytochalasin J (2) (Suppl. material 1: Figs S11–S17) (Cole et al. 1981; Shang et al. 2017) and cytochalasin RKS-1778 (3) (Suppl. material 1: Figs S18–S24) (Kakeya et al. 1997) respectively. The absolute configuration of cytochalasins H (1) and J (2) was confirmed by comparing their optical rotation values ([α]20D +55.7 (c 0.158, MeOH) for 1 and [α]20D +35.3 (c 0.394, MeOH) for 2) and ECD spectrum (Fig. 3) with those reported in the literature (Shang et al. 2017; Ma et al. 2021). The literature reports only the relative configuration of compound 3 (rel- (3S, 4R, 5S, 8S, 9S, 13E, 16S, 18R, 19E, 21R)) (Kakeya et al. 1997), therefore, its absolute configuration was investigated by comparison of its ECD spectrum with that of cytochalasins H (1) and J (2) (Fig. 3). The ECD spectrum of 3 showed negative (~ 200 nm) cotton effect, the shape of which matched with that of compounds 1 and 2. Thus, the hitherto unestablished absolute configuration of cytochalasin RKS-1778 (3) was confirmed to be 3S, 4R, 5S, 8R, 9R, 13E, 16S, 18R, 19E, 21R.

Figure 3.

ECD spectra of compounds 1–4 in MeOH.

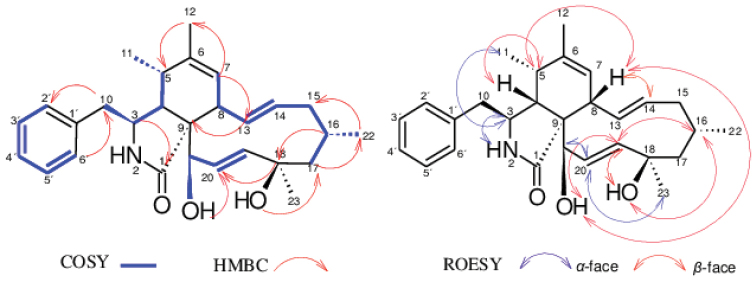

HR-ESI (+) MS analysis of 4 isolated as a yellowish oil afforded pseudo-molecular ion peaks [M+H]+ at m/z 436.2852 and [M+Na]+ at m/z 458.2665 attributed to the molecular formula C28H37NO3 (11 degrees of unsaturation). Comparison of the 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopic data for 4 (DMSO-d6) with those for 3 (Table 2) revealed that both compounds are closely related, with compound 4 being the deacetylated derivative of 3. This was confirmed on the 1H NMR spectrum of compound 4 by the absence of the methyl group H3-25 and on its 13C NMR spectrum by the absence of both C-24 carbonyl group and C-25 methyl group as visible on the NMR data recorded for compound 3 (Table 2). The relative configuration of compound 4 was determined by analysis of the coupling constants and NOESY correlations. The E-geometry of the ∆13,14 and ∆19,20 double bonds in the macrocyclic ring was determined based on the large coupling constants J = 15.3 and 16.7 Hz observed between H-13 and H-14 and between H-19 and H-20 respectively. The small coupling constant J = 4.4 Hz observed between H-4 and H-5 confirmed their cis relationship (Kakeya et al. 1997). The NOESY spectrum arbitrarily suggested α-orientation of H-3, H-11, H-21 and H-23 based on the observed correlations between H-3/H-11, H-20/H-21 and H-20/H-23,while the β-orientation of H-4, H-5, H-8, H-16, 18-OH and 21-OH were apparent from a network NOESY correlations between H-4/H-5, H-5/H-8, H-8/21-OH, 21-OH/H-19, H-19/H-16 and H-16/18-OH (Fig. 4). These correlations allowed the assignment of the relative configuration of compound 4 as either rel- (3S, 4R, 5S, 8S, 9S, 13E, 16S, 18R, 19E, 21R) or rel- (3R, 4S, 5R, 8R, 9R, 13E, 16R, 18S, 19E, 21S). In addition, the optical rotation value of 4 ([α]20D -17.6 (c 0.278, MeOH)) approximating that reported in the literature for 3 ([α]20D -20 (c 0.05, MeOH, Kakeya et al. 1997) revealed that both compounds are levorotatory, and this suggested the stereochemistry of 4 to be identical to that of 3. The latter assumption was confirmed by comparing the ECD spectrum of 4 with those of compounds 1, 2 and 3. The same negative Cotton effect (~ 200 nm) observed for all those compounds unambiguously certified the absolute configuration of compound 4 established as 3S, 4R, 5S, 8S, 9S, 13E, 16S, 18R, 19E, 21R. Thus, the structure of 4 was determined. This compound was regarded new while the current study has been under review, but concurrently it was published as phomopchalasin N by Chen et al. (2022). Interestingly, the authors also isolated it from a member of the genus Diaporthe, but inadvertently referred to their producer organism under the outdated name “Phomopsis”. We have decided to leave our complete data on the structure elucidation in the manuscript, so they can be compared with those of Chen et al. (2022) by other scientists, but the compounds are indeed identical.

Table 2.

13C (125 MHz) and 1H-NMR (500 MHz) spectroscopic data (DMSO-d6, δ in ppm) of compounds 3, 4.

| 3 | 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | δC, type | δH (J in Hz) | δC, type | δH (J in Hz) |

| 1 | 174.3, C | - | 175.9, C | - |

| 2-NH | - | 7.89, s | - | 7.57, s |

| 3 | 53.9, CH | 3.16, m | 53.8, CH | 3.14, q (4.9) |

| 4 | 50.5, CH | 2.02, t (4.1) | 50.9, CH | 2.47, t (4.4) |

| 5 | 34.1, CH | 2.18, m* | 34.3, CH | 2.3, m |

| 6 | 137.3, C | - | 137.1, C | - |

| 7 | 126.8, CH | 5.21* | 127.4, CH | 5.17, br s |

| 8 | 42.3, CH | 3.06 br d (9.9) | 40.9, CH | 3.04, br d (9.8) |

| 9 | 55.5, C | - | 57.2, C | - |

| 10 | 44.0, CH2 | 2.59, dd (13.2, 7.4) 2.74, dd (13.1, 5.3) | 43.6, CH2 | 2.65, dd (13.6, 5.2) 2.70, dd (13.6, 5.2) |

| 11 | 12.8, CH3 | 0.64, d (7.2) | 13.0, CH3 | 0.84, d (7.3) |

| 12 | 19.2, CH3 | 1.62, s | 19.3, CH3 | 1.63, s |

| 13 | 129.2, CH | 5.73, dd (15.7, 10.1) | 129.7, CH | 5.66, dd (15.3, 10.1) |

| 14 | 133.5, CH | 5.08, ddd (15.3, 10.9, 4.5) | 132.8, CH | 5.02, ddd (15.3, 11.0, 4.4) |

| 15 | 42.1, CH2 | 1.57, m* 1.89, br dd (12.4, 4.3) | 42.3, CH2 | 1.52, q (12.5) 1.84, br dd (12.5, 4.2) |

| 16 | 27.6, CH | 1.69, m | 27.7, CH | 1.69, m |

| 17 | 53.1, CH | 1.37, br dd (13.6, 3.2) 1.59, m* | 53.1, CH2 | 1.34, br dd (13.4, 3.3) 1.60, dd (13.6, 3.3) |

| 18 | 72.1, C | - | 72.2, C | - |

| 19 | 137.3, CH | 5.36, dd (16.6, 2.3) | 136.2, CH | 5.61, dd (16.7, 2.4) |

| 20 | 125.1, CH | 5.71, dd (16.9, 2.4) | 130.7, CH | 5.76, dd (16.7, 2.4) |

| 21 | 75.7, CH | 5.23* | 73.7, CH | 3.63, br s |

| 22 | 25.8, CH3 | 0.94, d (7.3) | 25.9, CH3 | 0.93, d (7.1) |

| 23 | 31.0, CH3 | 1.13, s | 31.5, CH3 | 1.12, s |

| 24 | 169.3, C | - | - | - |

| 25 | 20.2, CH3 | 2.18, s | - | - |

| 1´ | 136.8, C | - | 136.9, C | - |

| 2´/6´ | 129.6, CH (x2) | 7.12, d (7.0) | 129.8, CH (x2) | 7.21* |

| 3´/5´ | 127.9, CH (x2) | 7.29, t (7.5) | 127.7, CH (x2) | 7.29, t (7.7) |

| 4´ | 126.0, CH | 7.21, t (7.5) | 126.0, CH | 7.21* |

| 18-OH | - | 4.36, s | - | 4.17, s |

| 21-OH | - | - | - | 4.88, br d (5.6) |

*overlapping signals, assignments were supported by HSQC and HMBC

Figure 4.

Selected 1H–1H COSY, NOESY and HMBC correlations of 4.

Compounds 5 and 6 were readily identified as the known fusaristatins A and B respectively, after careful analysis of their HR-ESI (+) MS and NMR spectroscopic data (Suppl. material 1: Figs S34–S47). Fusaristatins A (5) and B (6) were first reported in 2007 from an endophytic Fusarium sp. (Shiono et al. 2007) and so far, only fusaristatin A (5) has been isolated from D.phaeseolorum and D.longicolla (syn: Phomopsislongicolla) (Santos et al. 2011; Choi et al. 2013; Cui et al. 2017). Therefore, this is the first report for the isolation of fusaristatin B (6) from the genus Diaporthe. In addition, two new derivatives of fusaristatin A (7, 8) were isolated from Diaporthebreyniae and their structures were established by intensive analysis of their 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopic data in combination with HR-ESIMS data and by comparison with the data reported in the literature for fusaristatins A (5) and B (6) (Shiono et al. 2007).

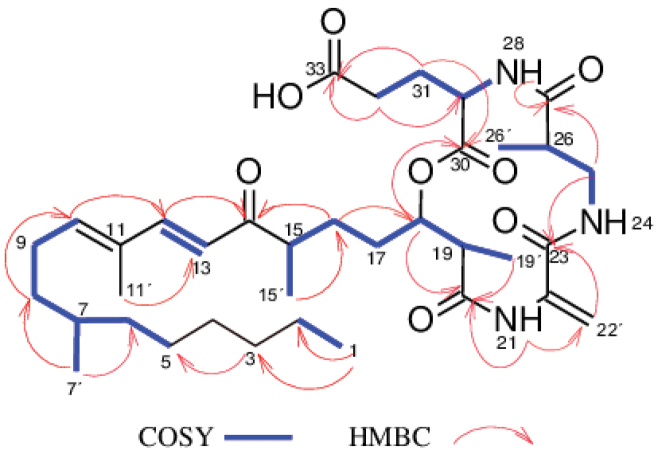

The molecular formula of compound 7, isolated as a colorless oil, was determined to be C36H57N3O8 from the HR-ESIMS (positive mode) which showed pseudo-molecular ion peaks [M+H]+ at m/z 660.4219 and [M+Na]+ at m/z 682.4024, indicating 10 degrees of unsaturation. Inspection of the molecular formula of 7 (C36H57N3O8) in comparison to that of 5 (C36H58N4O7) suggested that an amino group (-NH2) in compound 5 could probably have been replaced by a hydroxyl group (-OH) in compound 7. Intensive analysis of 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopic data (C5D5N) of compound 7 in comparison to that of 5 indicated that most signals in 7 were the same as those for 5 (Table 3), implying that 7 and 5 are closely related. The only difference was observed on the 1H NMR spectrum where the signal corresponding to the amino group 34-NH2 (δH 8.34) in compound 5 was absent in compound 7 (Table 3). Moreover, in the HMBC spectrum of 7, correlations from H-31 to C-30, H-31/H-32 to C-33 suggested the presence of a glutamic acid residue instead of a glutamine residue as observed in 5. Based on 1H-1H COSY, 1H-13C HSQC and 1H-13C HMBC experiments (Fig. 5), the signals of all protons and carbons in the molecule were unambiguously assigned and compound 7 was identified as a new derivative of fusaristatin A named fusaristatin G.

Table 3.

13C and 1H-NMR spectroscopic data (pyridine-d5, δ in ppm) of compounds 5, 7, 8.

| 5a | 7b | 8b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | δC, type | δH (J in Hz) | δC, type | δH (J in Hz) | δC, type | δH (J in Hz) |

| 1 | 14.7, CH3 | 0.88* | 14.7, CH3 | 0.87* | 14.5, CH3 | 0.87, t (6.9)* |

| 2 | 23.4, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* | 23.4, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* | 23.1, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* |

| 3 | 32.6, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* | 32.6, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* | 32.3, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* |

| 4 | 27.7, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* | 27.7, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* | 27.4, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* |

| 5 | 30.3, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* | 30.3, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* | 30.1, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* |

| 6 | 37.5, CH2 | 1.09, m* 1.20-1.31, m* | 37.5, CH2 | 1.09, m* 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* | 37.3, CH2 | 1.09, m* 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* |

| 7 | 33.2, CH | 1.39, m* | 33.2, CH | 1.40, m* | 32.9, CH | 1.38, m* |

| 7´ | 20.0, CH3 | 0.88* | 20.0, CH3 | 0.88* | 19.8, CH3 | 0.87, d (6.9)* |

| 8 | 36.8, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31* 1.40, m* | 36.9, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* 1.40, m* | 36.6, CH2 | 1.20 ~ 1.31, m* 1.40, m* |

| 9 | 27.2, CH2 | 2.19, m* | 27.2, CH2 | 2.18, m | 27.0, CH2 | 2.21, m* |

| 10 | 144.5, CH | 6.03, br t (7.4) | 144.5, CH | 6.03, br t (7.2) | 144.3, CH | 6.01, t (7.4) |

| 11 | 133.9, C | - | 140.0, C | - | 133.9, C | - |

| 11´ | 12.6, CH3 | 1.83, s | 12.7, CH3 | 1.83, s | 12.5, CH3 | 1.85, s |

| 12 | 148.4, CH | 7.54, d (15.7) | 148.3, CH | 7.56, d (15.7) | 148.2, CH | 7.55, d (15.7) |

| 13 | 123.7, CH | 6.40, d (15.7) | 123.8, CH | 6.40, d (15.7) | 123.6, CH | 6.45, d (15.7) |

| 14 | 203.8, C | - | 203.6, C | - | 204.1, C | - |

| 15 | 44.5, CH | 2.84, m | 44.6, CH | 2.80 ~ 2.88, m* | 44.6, CH | 2.88, m |

| 15´ | 17.7, CH3 | 1.10, d (6.9) | 17.6, CH3 | 1.10, d (6.9) | 17.1, CH3 | 1.13, d (6.9) |

| 16 | 28.5, CH2 | 1.57, m 1.93 ~ 2.00, m* | 28.3, CH2 | 1.54, m 1.93 ~ 2.00, m* | 29.1, CH2 | 1.66, m 2.04, m* |

| 17 | 30.3, CH2 | 1.87, m 1.93 ~ 2.00, m* | 30.2, CH2 | 1.84, m 1.93 ~ 2.00, m* | 31.3, CH2 | 1.97, m 2.04, m* |

| 18 | 77.3, CH | 5.44, m | 77.2, CH | 5.48, m | 77.6, CH | 5.45, m |

| 19 | 44.6, CH | 3.03, quin (7.0) | 44.5, CH | 3.05, quin (7,0) | 45.6, CH | 2.95, m |

| 19´ | 15.8, CH3 | 1.30, d (7.0)* | 15.9, CH3 | 1.33, d (7.3)* | 14.9, CH3 | 1.35, d (7.3) |

| 20 | 173.9, C | - | 174.0, C | - | 173.5, C | - |

| 21-NH | - | 10.43, s | - | 10.55, s | - | 8.15, br s |

| 22 | 139.6, C | - | 139.8, C | - | 50.9, CH | 4.89, m |

| 22´ | 114.6, CH2 | 5.60, s 6.24, s | 114.3, CH2 | 5.59, s 6.22, s | 17.3, CH3 | 1.65, d (7.1) |

| 23 | 165.2, C | - | 165.3, C | 173.9, C | - | |

| 24-NH | - | 7.81, br s | - | 7.88, br t (6.1) | - | 7.96, br s |

| 25 | 43.0, CH2 | 3.81, dt (13.5, 6.9) 3.92, dt (13.3, 4.9) | 43.0, CH2 | 3.78, dt (13.5, 6.7) 3.94, m | 42.1, CH2 | 3.49, dt (13.6, 3.8) 4.04, dt (13.5, 7.9) |

| 26 | 42.7, CH | 2.87, m | 42.7, CH | 2.92, m | 42.8, CH | 2.85, m |

| 26´ | 15.5, CH3 | 1.30, d (7.0)* | 15.8, CH3 | 1.33, d (7.3)* | 14.9, CH3 | 1.22, d (7.3) |

| 27 | 175.0, C | - | 175.1, C | - | 175.4, C | - |

| 28-NH | - | 9.06, br d (7.5) | - | 9.11, br d (7.7) | - | 8.90, br d (7.7) |

| 29 | 53.6, CH | 5.13, dd (14.3, 7.6) | 53.4, CH | 5.18, m* | 53.6, CH | 5.06, dd (12.9, 6.2) |

| 30 | 172.3, C | - | 172.4, C | - | 172.5, C | - |

| 31 | 27.6, CH2 | 2.63, dt (13.7, 7.0) 2.69 ~ 2.77, m* | 27.5, CH2 | 2.62, dt (13.8, 6.9) 2.71, tt (13.8, 6.9) | 27.3, CH2 | 2.51, m 2.68 ~ 2.74, m* |

| 32 | 32.8, CH2 | 2.69 ~ 2.77, m* | 32.1, CH2 | 2.80 ~ 2.88, m* | 32.7, CH2 | 2.68 ~ 2.74, m* |

| 33 | 175.7, C | - | 176.1, C | - | 176.7, C | - |

| 34-NH2 | - | 8.34, s | - | - | - | 8.32, br s |

*overlapping signals: assignments were supported by HSQC and HMBC, a 1H 500 MHZ, 13C 125 MHz; b 1H 700 MHZ, 13C 175 MHZ.

Figure 5.

Selected 1H–1H COSY and HMBC correlations of 7.

Compound 8 was obtained as a white amorphous solid. The molecular formula was established as C36H60N4O7 on the basis of the pseudo-molecular ion peaks [M+H]+ at m/z 661.4542 and [M+Na]+ at m/z 683.4354 observed in the HR-ESI(+)MS, indicating 9 double bond equivalents. The molecular formula of 8 (C36H60N4O7) compared to that of 5 (C36H58N4O7) showed an increase of 2 Da suggesting that a reduction occurred in compound 5 to afford compound 8. This assumption was confirmed on the 1H NMR spectrum of 8 where the signals in the downfield region corresponding to Ha-22´ (δH 5.60) and Hb-22´ (δH 6.24) as observed in 5 were missing, but instead the signal in the upfield region corresponding to a methyl group H3-22´ at δH 1.65 was recorded (Table 3). Moreover, an additional signal observed on the 1H NMR of 8 attributable to the methine H-22 (δH 4.89) further confirmed this assumption, indicating that the reduction of 5 occurred on the ∆22-22´ double bond to afford 8. The reduction of the double bond ∆22-22´ further justified the upfield shift of the nitrogen-bearing proton 21-NH, which resonated at δH 8.15 in compound 8 instead of δH 10.43 as in compound 5. In the HMBC spectrum, the correlations observed between H-22´ and C-22/C-23, H-22 and C-22´/C-23 confirmed the presence of an alanine residue instead of dehydroalanine residue as previously reported for 5 (Shiono et al. 2007). Finally, the unambiguous assignment of all proton and carbon signals in metabolite 8 was achieved based on 1H-13C HSQC and 1H-13C HMBC experiments, thus identifying compound 8 as a new derivative of fusaristatin A, for which the trivial name fusaristatin H was assigned.

Compounds 9–13 were respectively identified as phomoxanthones A (9) and B (10) (Isaka et al. 2001), dicerandrol B (11) (Wagenaar and Clardy 2001), phomochromenone C (12) (Ding et al. 2017; Wei et al. 2021), and diaporchromanone C (13) (Wei et al. 2021) by comparison of their HR-ESIMS and 1D and 2 D NMR spectroscopic data (Suppl. material 1: Figs S65–S99) with those reported in the literature.

Physico-chemical characteristic of compounds 4, 7 and 8

Phomopchalasin N (4): Yellowish oil. [α]20D -17.6 (c 0.278, MeOH), UV (MeOH, c = 0.013 mg/mL) λmax (log ε) 202 (4.32) nm. CD (c = 2.83 × 10-3 M, MeOH) λmax (Δε) 200 (-7.66) nm. HR-ESIMSm/z 458.2665 [M + Na]+, m/z 893.5440 [2M + Na]+, m/z 871.5621 [2M + H]+, m/z 418.2746 [M + H - H2O]+, m/z 436.2852 [M + H]+ (Calcd for C28H38NO3+ 436.2846), tR = 10.47 min. For NMR data (1H: 500 MHz, 13C: 125 MHz, DMSO-d6), see Table 2.

Fusaristatin G (7): colorless oil. [α]20D -8 (c 0.1, MeOH), UV (MeOH, c = 0.02 mg/mL) λmax (log ε) 201 (4.21), 283 (3.96) nm. HR-ESIMSm/z 682.4024 [M + Na]+, m/z 1341.8157 [2M + Na]+, m/z 1319.8354 [2M + H]+, m/z 642.4102 [M + H - H2O]+, m/z 660.4219 [M + H]+ (Calcd for C36H58N3O8+ 660.4218), tR = 14.80 min. For NMR data (1H: 700 MHz, 13C: 175 MHz, C5H5N-d5), see Table 3.

Fusaristatin H (8): White amorphous solid. [α]20D +14 (c 0.03, MeOH), UV (MeOH, c = 0.02 mg/mL) λmax (log ε) 201 (4.24), 283 (4.20) nm. HR-ESIMSm/z 683.4354 [M + Na]+, m/z 1343.8820 [2M + Na]+, m/z 1321.9000 [2M + H]+, m/z 661.4542 [M + H]+ (Calcd for C36H61N4O7+ 661.4535), tR = 14.46 min. For NMR data (1H: 700 MHz, 13C: 175 MHz, C5H5N-d5), see Table 3.

Biological activity

The extracts obtained from the fungal culture in ZM ½ exhibited activities against Bacillussubtilis with MIC values of 75 µg/mL for the supernatant´s extract and 2.3 µg/mL for the mycelial extract. These extracts were also active against Mucorplumbeus with respective MIC values of 150 and 37.5 µg/mL. Moreover, the purified compounds 1–7, 9, 10, 12, and 13 were subjected to antimicrobial assays against a panel of bacteria and fungi. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values showed that all compounds were active against at least one of the tested micro-organisms at concentration of 66.7 μg/mL (Table 4). Overall, the majority of the tested compounds exhibited weak to moderate activity. However, significant activity was noted for phomoxanthones A (9) and B (10) against Bacillussubtilis. Both compounds inhibited the growth of the latter bacterium with a MIC value of 1.7 μg/mL, which turned out to be 5 times stronger than that of oxytetracyclin used as positive control. In addition, their MIC value of 4.2 μg/mL against the Gram-positive bacterium S.aureus was quite considerable in comparison to that of the other tested compounds. This finding concurs well with previously published data which reported the antimicrobial activity of xanthone derivatives isolated from Diaporthe spp. (Wagenaar and Clardy 2001; Elsässer et al. 2005; Lim et al. 2010). The antimicrobial activity of dicerandrol B (11), a closely related congener of phomoxanthones A (9) and B (10) was not investigated in the present work due to the low amount of available sample, however, its activity against B.subtilis and S.aureus has previously been reported (Wagenaar and Clardy 2001). The antimicrobial activity of compound 8 was not assessed due to the paucity of the sample.

Table 4.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC) of compounds 1–7, 9–10, 12–13 against tested microorganisms.

| MIC (μg/mL) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test organisms | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | References |

| Acinetobacterbaumannii | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.26c |

| Bacillussubtilis | - | - | 16.7 | 66.7 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 66.7 | 8.3° | ||

| Candidaalbicans | - | - | - | - | - | - | 66.7 | - | - | - | 16.6n | |

| Chromobacteriumviolaceum | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.83° |

| Escherichiacoli | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.7° | |

| Mucorhiemalis | 66.7 | - | 66.7 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 16.7 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 8.3n |

| Mycobacteriumsmegmatis | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 66.7 | - | - | - | 1.7k |

| Pichiaanomala | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8.3n |

| Pseudomonasaeruginosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.21g |

| Rhodotorulaglutinis | 66.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4.2n |

| Schizosaccharomycespombe | 16.7 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 66.7 | - | - | - | - | 66.7 | - | - | 8.3n |

| Staphylococcusaureus | - | - | 66.7 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 66.7 | - | 0.83° | |

(-): No inhibition, cCiprobay 2.54 mg/mL, gGentamycin 1 mg/mL, kKanamycin 1 mg/mL, nNystatin 1 mg/mL, °Oxytetracyclin 1 mg/mL. Starting concentration for antimicrobial assay were 66.7 μg/mL.

The cytotoxicity of all the isolated compounds except 11 was evaluated against a panel of mammalian cell lines. Eight compounds, 1–5 and 8–10 showed activity in this assay whereas the other isolated metabolites were inactive under test conditions (Table 5). The very significant activity exhibited by compounds 1–4 against all tested cancer cell lines were in agreement with previous studies which have reported cytochalasins as potent cytotoxins (Shang et al. 2017). However, when comparing the activity of the cytochalasin 4, which is the deacetylated derivative of 3, it was quite interesting to notice that 4 is significantly less toxic than 3 leading to the hypothesis that the presence of the acetyl group in 3 is an important structural element in the biological activity of the studied cytochalasins. The aforementioned assumption, was also observed when comparing the cytotoxicity of compound 1 and 2. In effect, 2 is the deacetylated derivative of 1, and the latter was also found to be less toxic than 1. These results therefore give some hints in regards to the structure activity relationship (SAR) of the isolated cytochalasins, which will be tested further for their inhibitory effect on actin. In the same assay, compound 5 and 8 were found to be active against KB3.1 cell line with IC50 value of 10.63 and 30.3 µM respectively whereas compound 6 and 7 bearing the same core skeleton did not show any activity. These results indicated that the cytotoxicity of this class of compounds might possibly be enhanced by the presence of an amide group (C-33) as shown in 5 and 8 instead of a carboxylic acid as observed in 6 (C-34) and 7 (C-33). In addition, phomoxanthones A (9) and B (10), exhibited strong cytotoxic activities with half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) in the range 0.02 – 9.7 µM. These results were in accordance with previous published cytotoxicity of dimeric tetrahydroxanthone derivatives against human epidermoid carcinoma (KB), human breast cancer (BC-1), mouse lymphoma (L5178Y), human ovarian carcinoma (A2780), and African monkey kidney fibroblast (Vero) cell lines among others (Isaka et al. 2001; Rönsberg et al. 2013).

Table 5.

Cytotoxic activity of compounds 1–10, 12–13.

| IC50 (µM) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell lines | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | Epothilone B |

| KB3.1 | 0.064 | 0.33 | 1.7 | 5.8 | 10.6 | - | - | 30.3 | 0.36 | 0.91 | - | - | 6.5×10-5 |

| L929 | 0.19 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 10.8 | >30.4 | - | - | - | 1.06 | 5.6 | - | - | 6.5×10-4 |

| A431 | 0.085 | 0.33 | 14.3 | 11.0 | 12.0 | n.t | n.t | n.t | 0.04 | 0.17 | n.t | n.t | 1.2×10-4 |

| MCF-7 | 0.14 | 3.1 | 7.3 | 19.3 | 7.44 | n.t | n.t | n.t | 0.02 | 0.36 | n.t | n.t | 8.2×10-5 |

| A549 | 0.16 | 0.73 | 3.1 | 10.3 | 19.7 | n.t | n.t | n.t | 0.43 | 1.0 | n.t | n.t | 6.1×10-5 |

| SKOV-3 | 0.073 | 0.33 | 13.6 | 45.9 | 13.9 | n.t | n.t | n.t | 0.15 | 0.65 | n.t | n.t | 2.9×10-4 |

| PC-3 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 4.2 | 9.4 | 7.3 | n.t | n.t | n.t | 1.1 | 9.7 | n.t | n.t | 9.5×10-4 |

n.t: not tested, (-): no activity. Starting concentration for cytotoxicity assay was 37 µg/mL

Conclusion

The genus Diaporthe has been regarded for decades as a potential source for the production of diverse bioactive secondary metabolites. In the present study, we suggest the introduction of the new species D.breyniae isolated from the twigs of Breyniaoblongifolia in Cameroon. From the liquid culture of this fungus, two previously undescribed polyketides were isolated together with eleven known compounds. The isolated compounds showed weak to strong antimicrobial activities as well as moderate cytotoxic activities overall. These results demonstrated that it should certainly be worthwhile to explore untapped geographic area like the African tropics in general and Cameroon in particular for the discovery of new fungi and the isolation of novel secondary metabolites produced by these with significant biological activities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to W. Collisi for conducting the cytotoxicity assays, C. Kakoschke for recording NMR data and E. Surges for recording HPLC-MS data. The authors wish to thank V. Nana (National Herbarium of Cameroon) for the botanical identifications and S.C.N. Wouamba for the isolation of the strain CBS 148910. Financial support by a personal PhD stipend from the German Academic exchange service (DAAD) to B.M.K. is gratefully acknowledged (programme ID- 57440921). Y.M.F. is grateful for the postdoctoral stipendium received from Alexander-von-Humboldt Foundation, Germany. We are also grateful to The World Academy of Sciences (TWAS) (grant 18‐178 RG/CHE/AF/AC_G‐FR 3240303654), and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (AvH) through the equipment subsidies (Ref 3.4 - 8151/20 002), the Research Group Linkage (grant IP-CMR-1121341) and the hub project CECANOPROF (3.4-CMR-Hub). Furthermore, we are grateful to the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for a Research Unit grant “Cytolabs” (DFG-FOR-5170).

Citation

Matio Kemkuignou B, Schweizer L, Lambert C, Anoumedem EGM, Kouam SF, Stadler M, Marin-Felix Y (2022) New polyketides from the liquid culture of Diaporthe breyniae sp. nov. (Diaporthaceae, Diaporthales). MycoKeys 90: 85–118. https://doi.org/10.3897/mycokeys.90.82871

Funding Statement

German Academic exchange service (DAAD) Postdoctoral stipendium received from Alexander-von-Humboldt Foundation, Germany. The World Academy of Sciences (TWAS) (grant 18‐178 RG/CHE/AF/AC_G‐FR 3240303654), and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (AvH) through the equipment subsidies (Ref 3.4 - 8151/20 002) and the Research Group Linkage (grant IP-CMR-1121341). F Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for a Research Unit grant “Cytolabs” (DFG-FOR-5170).

Supplementary materials

Figures S1–S100, Tables S1–S5

This dataset is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). The Open Database License (ODbL) is a license agreement intended to allow users to freely share, modify, and use this Dataset while maintaining this same freedom for others, provided that the original source and author(s) are credited.

Blondelle Matio Kemkuignou, Lena Schweizer, Christopher Lambert, Elodie Gisèle M. Anoumedem, Simeon F. Kouam, Marc Stadler, Yasmina Marin-Felix

Data type

Docx file.

Explanation note

The following are available online: 1D, 2D NMR, ESIMS and HR-ESIMS spectra of compounds 1–13; Fig. S100, ML phylogram including our strain and type and reference strains of Diaporthe spp.; Table S1–S4, Information of the phylogenetic study; Alignment of the ITS, cal, his3, tef1, tub2 sequences used in the second phylogenetic study.

References

- Alfaro ME, Zoller S, Lutzoni F. (2003) Bayes or bootstrap. A simulation study comparing the performance of Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling and bootstrapping in assessing phylogenetic confidence. Molecular Biology and Evolution 20(2): 255–266. 10.1093/molbev/msg028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker K, Wongkanoun S, Wessel AC, Bills GF, Stadler M, Luangsa-Ard JJ. (2020a) Phylogenetic and chemotaxonomic studies confirm the affinities of Stromatoneurosporaphoenix to the coprophilous Xylariaceae. Journal of Fungi (Basel, Switzerland) 6(3): 1–21. 10.3390/jof6030144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker K, Wessel AC, Luangsa-Ard JJ, Stadler M. (2020b) Viridistratins A–C, antimicrobial and cytotoxic benzo[j]fluoranthenes from stromata of Annulohypoxylonviridistratum (Hypoxylaceae, Ascomycota). Biomolecules 10(5): 805. 10.3390/biom10050805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beno MA, Christoph GG, Cox RH, Wells JM, Cole RJ, Kirksey JW. (1977) Structure of a New [1 l]Cytochalasin, Cytochalasin H or Kodo-cytochalasin-1. Journal of the American Chemical Society 99(12): 4123–4130. 10.1021/ja00454a035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone I, Kohn LM. (1999) A method for designing primer sets for the speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 91(3): 553–556. 10.1080/00275514.1999.12061051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaisiri C, Liu X-Y, Yin W-X, Luo C-X, Lin Y. (2021) Morphology characterization, molecular phylogeny, and pathogenicity of Diaporthepassifloricola on Citrusreticulata cv. Nanfengmiju in Jiangxi Province, China. Plants 10(2): e218. 10.3390/plants10020218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chang CQ, Cheng YH, Xiang MM, Jiang ZD. (2005) New species of Phomopsis on woody plants in Fujian Province. Junwu Xuebao 24: 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Yang W, Zou G, Wang G, Kang W, Yuan J, She Z. (2022) Cytotoxic bromine- and iodine-containing cytochalasins produced by the mangrove endophytic fungus Phomopsis sp. QYM-13 using the OSMAC approach. Journal of Natural Products. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c01115 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chepkirui C, Stadler M. (2017) The genus Diaporthe: A rich source of diverse and bioactive metabolites. Mycological Progress 16(5): 477–494. 10.1007/s11557-017-1288-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chepkirui C, Richter C, Matasyoh JC, Stadler M. (2016) Monochlorinated calocerins A-D and 9-oxostrobilurin derivatives from the basidiomycete Favolaschiacalocera. Phytochemistry 132: 95–101. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, Monh BQ. (2016) Terrace aware data structure for Phylogenomic Inference from Supermatrices. Systematic Biology 65(6): 997–1008. 10.1093/sysbio/syw037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JN, Kim J, Ponnusamy K, Lim C, Kim JG, Muthaiya MJ, Lee CH. (2013) Metabolic Changes of Phomopsislongicolla Fermentation and Its Effect on Antimicrobial Activity Against Xanthomonasoryzae. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 23(2): 177–183. 10.4014/jmb.1210.10020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole RJ, Wells JM, Cox RH, Cutler HG. (1981) Isolation and biological properties of deacetylcytochalasin H from Phomopsis sp. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 29(1): 205–206. 10.1021/jf00103a057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Groenewald JZ, Risede JM, Simoneau P, Hyde KD. (2004) Calonectria species and their Cylindrocladium anamorphs: Species with sphaeropedunculate vesicles. Studies in Mycology 50: 415–430. 10.3114/sim.55.1.213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Summerell BA, Shivas RG, Romberg M, Mel’nik VA, Verkley GJM, Groenewald JZ. (2011) Fungal Planet description sheets: 92–106. Persoonia 27(1): 130–162. 10.3767/003158511X617561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Wingfield MJ, Schumacher RK, Summerell BA, Giraldo A, Gené J, Guarro J, Wanasinghe DN, Hyde KD, Camporesi E, Garethjones EB, Thambugala KM, Malysheva EF, Malysheva VF, Acharya K, Álvarez J, Alvarado P, Assefa A, Barnes CW, Bartlett JS, Blanchette RA, Burgess TI, Carlavilla JR, Coetzee MPA, Damm U, Decock CA, Denbreeÿen A, Devries B, Dutta AK, Holdom DG, Rooney-Latham S, Manjón JL, Marincowitz S, Mirabolfathy M, Moreno G, Nakashima C, Papizadeh M, Shahzadehfazeli SA, Amoozegar MA, Romberg MK, Shivas RG, Stalpers JA, Stielow B, Stukely MJC, Swart WJ, Tan YP, Vanderbank M, Wood AR, Zhang Y, Groenewald JZ. (2014) Fungal Planet description sheets: 281–319. Persoonia 33(1): 212–289. 10.3767/003158514X685680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Wingfield MJ, Le Roux JJ, Richardson DM, Strasberg D, Shivas RG, Alvarado P, Edwards J, Moreno G, Sharma R, Sonawane MS, Tan YP, Altés A, Barasubiye T, Barnes CW, Blanchette RA, Boertmann D, Bogo A, Carlavilla JR, Cheewangkoon R, Daniel R, de Beer ZW, de Jesús Yáñez-Morales M, Duong TA, Fernández-Vicente J, Geering ADW, Guest DI, Held BW, Heykoop M, Hubka V, Ismail AM, Kajale SC, Khemmuk W, Kolařík M, Kurli R, Lebeuf R, Lévesque CA, Lombard L, Magista D, Manjón JL, Marincowitz S, Mohedano JM, Nováková A, Oberlies NH, Otto EC, Paguigan ND, Pascoe IG, Pérez-Butrón JL, Perrone G, Rahi P, Raja HA, Rintoul T, Sanhueza RMV, Scarlett K, Shouche YS, Shuttleworth LA, Taylor PWJ, Thorn RG, Vawdrey LL, Solano-Vidal R, Voitk A, Wong PTW, Wood AR, Zamora JC, Groenewald JZ. (2015) Fungal Planet description sheets: 371–399. Persoonia 35(1): 264–327. 10.3767/003158515X690269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Wingfield MJ, Richardson DM, Leroux JJ, Strasberg D, Edwards J, Roets F, Hubka V, Taylor PWJ, Heykoop M, Martín MP, Moreno G, Sutton DA, Wiederhold NP, Barnes CW, Carlavilla JR, Gené J, Giraldo A, Guarnaccia V, Guarro J, Hernández-Restrepo M, Kolařík M, Manjón JL, Pascoe IG, Popov ES, Sandoval-Denis M, Woudenberg JHC, Acharya K, Alexandrova AV, Alvarado P, Barbosa RN, Baseia IG, Blanchette RA, Boekhout T, Burgess TI, Cano-Lira JF, Čmoková A, Dimitrov RA, Dyakov MY, Dueñas M, Dutta AK, Esteve-Raventós F, Fedosova AG, Fournier J, Gamboa P, Gouliamova DE, Grebenc T, Groenewald M, Hanse B, Hardy GESTJ, Held BW, Jurjević Ž, Kaewgrajang T, Latha KPD, Lombard L, Luangsa-ard JJ, Lysková P, Mallátová N, Manimohan P, Miller AN, Mirabolfathy M, Morozova OV, Obodai M, Oliveira NT, Ordóñez ME, Otto EC, Paloi S, Peterson SW, Phosri C, Roux J, Salazar WA, Sánchez A, Sarria GA, Shin H-D, Silva BDB, Silva GA, Smith MTH, Souza-Motta CM, Stchigel AM, Stoilova-Disheva MM, Sulzbacher MA, Telleria MT, Toapanta C, Traba JM, Valenzuela-Lopez N, Watling R, Groenewald JZ. (2016) Fungal Planet description sheets: 400–468. Persoonia 36(1): 316–458. 10.3767/003158516X692185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Carnegie AJ, Wingfield MJ, Sharma R, Mughini G, Noordeloos ME, Santini A, Shouche YS, Bezerra JDP, Dima B, Guarnaccia V, Imrefi I, Jurjević Ž, Knapp DG, Kovács GM, Magistà D, Perrone G, Rämä T, Rebriev YA, Shivas RG, Singh SM, Souza-Motta CM, Thangavel R, Adhapure NN, Alexandrova AV, Alfenas AC, Alfenas RF, Alvarado P, Alves AL, Andrade DA, Andrade JP, Barbosa RN, Barili A, Barnes CW, Baseia IG, Bellanger J-M, Berlanas C, Bessette AE, Bessette AR, Biketova AYu, Bomfim FS, Brandrud TE, Bransgrove K, Brito ACQ, Cano-Lira JF, Cantillo T, Cavalcanti AD, Cheewangkoon R, Chikowski RS, Conforto C, Cordeiro TRL, Craine JD, Cruz R, Damm U, de Oliveira RJV, de Souza JT, de Souza HG, Dearnaley JDW, Dimitrov RA, Dovana F, Erhard A, Esteve-Raventós F, Félix CR, Ferisin G, Fernandes RA, Ferreira RJ, Ferro LO, Figueiredo CN, Frank JL, Freire KTLS, García D, Gené J, Gęsiorska A, Gibertoni TB, Gondra RAG, Gouliamova DE, Gramaje D, Guard F, Gusmão LFP, Haitook S, Hirooka Y, Houbraken J, Hubka V, Inamdar A, Iturriaga T, Iturrieta-González I, Jadan M, Jiang N, Justo A, Kachalkin AV, Kapitonov VI, Karadelev M, Karakehian J, Kasuya T, Kautmanová I, Kruse J, Kušan I, Kuznetsova TA, Landell MF, Larsson K-H, Lee HB, Lima DX, Lira CRS, Machado AR, Madrid H, Magalhães OMC, Majerova H, Malysheva EF, Mapperson RR, Marbach PAS, Martín MP, Martín-Sanz A, Matočec N, McTaggart AR, Mello JF, Melo RFR, Mešič A, Michereff SJ, Miller AN, Minoshima A, Molinero-Ruiz L, Morozova OV, Mosoh D, Nabe M, Naik R, Nara K, Nascimento SS, Neves RP, Olariaga I, Oliveira RL, Oliveira TGL, Ono T, Ordoñez ME, de M Ottoni A, Paiva LM, Pancorbo F, Pant B, Pawłowska J, Peterson SW, Raudabaugh DB, Rodríguez-Andrade E, Rubio E, Rusevska K, Santiago ALCMA, Santos ACS, Santos C, Sazanova NA, Shah S, Sharma J, Silva BDB, Siquier JL, Sonawane MS, Stchigel AM, Svetasheva T, Tamakeaw N, Telleria MT, Tiago PV, Tian CM, Tkalčec Z, Tomashevskaya MA, Truong HH, Vecherskii MV, Visagie CM, Vizzini A, Yilmaz N, Zmitrovich IV, Zvyagina EA, Boekhout T, Kehlet T, Læssøe T, Groenewald JZ. (2019) Fungal Planet description sheets: 868–950. Persoonia 42: 291–473. 10.3767/persoonia.2019.42.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Wingfield MJ, Chooi Y-H, Gilchrist CLM, Lacey E, Pitt JI, Roets F, Swart WJ, Cano-Lira JF, Valenzuela-Lopez N, Hubka V, Shivas RG, Stchigel AM, Holdom DG, Jurjević Ž, Kachalkin AV, Lebel T, Lock C, Martín MP, Tan YP, Tomashevskaya MA, Vitelli JS, Baseia IG, Bhatt VK, Brandrud TE, De Souza JT, Dima B, Lacey HJ, Lombard L, Johnston PR, Morte A, Papp V, Rodríguez A, Rodríguez-Andrade E, Semwal KC, Tegart L, Abad ZG, Akulov A, Alvarado P, Alves A, Andrade JP, Arenas F, Asenjo C, Ballarà J, Barrett MD, Berná LM, Berraf-Tebbal A, Bianchinotti MV, Bransgrove K, Burgess TI, Carmo FS, Chávez R, Čmoková A, Dearnaley JDW, Santiago ALCMA, Freitas-Neto JF, Denman S, Douglas B, Dovana F, Eichmeier A, Esteve-Raventós F, Farid A, Fedosova AG, Ferisin G, Ferreira RJ, Ferrer A, Figueiredo CN, Figueiredo YF, Reinoso-Fuentealba CG, Garrido-Benavent I, Cañete-Gibas CF, Gil-Durán C, Glushakova AM, Gonçalves MFM, González M, Gorczak M, Gorton C, Guard FE, Guarnizo AL, Guarro J, Gutiérrez M, Hamal P, Hien LT, Hocking AD, Houbraken J, Hunter GC, Inácio CA, Jourdan M, Kapitonov VI, Kelly L, Khanh TN, Kisło K, Kiss L, Kiyashko A, Kolařík M, Kruse J, Kubátová A, Kučera V, Kučerová I, Kušan I, Lee HB, Levicán G, Lewis A, Liem NV, Liimatainen K, Lim HJ, Lyons MN, Maciá-Vicente JG, Magaña-Dueñas V, Mahiques R, Malysheva EF, Marbach PAS, Marinho P, Matočec N, McTaggart AR, Mešić A, Morin L, Muñoz-Mohedano JM, Navarro-Ródenas A, Nicolli CP, Oliveira RL, Otsing E, Ovrebo CL, Pankratov TA, Paños A, Paz-Conde A, Pérez-Sierra A, Phosri C, Pintos Á, Pošta A, Prencipe S, Rubio E, Saitta A, Sales LS, Sanhueza L, Shuttleworth LA, Smith J, Smith ME, Spadaro D, Spetik M, Sochor M, Sochorová Z, Sousa JO, Suwannasai N, Tedersoo L, Thanh HM, Thao LD, Tkalčec Z, Vaghefi N, Venzhik AS, Verbeken A, Vizzini A, Voyron S, Wainhouse M, Whalley AJS, Wrzosek M, Zapata M, Zeil-Rolfe I, Groenewald JZ. (2020) Fungal Planet description sheets: 1042–1111. Persoonia 44(1): 301–459. 10.3767/persoonia.2020.44.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Hernández-Restrepo M, Schumacher RK, Cowan DA, Maggs-Kölling G, Marais E, Wingfield MJ, Yilmaz N, Adan OCG, Akulov A, Álvarez Duarte E, Berraf-Tebbal A, Bulgakov TS, Carnegie AJ, de Beer ZW, Decock C, Dijksterhuis J, Duong TA, Eichmeier A, Hien LT, Houbraken JAMP, Khanh TN, Liem NV, Lombard L, Lutzoni FM, Miadlikowska JM, Nel WJ, Pascoe IG, Roets F, Roux J, Samson RA, Shen M, Spetik M, Thangavel R, Thanh HM, Thao LD, van Nieuwenhuijzen EJ, Zhang JQ, Zhang Y, Zhao LL, Groenewald JZ. (2021) New and Interesting Fungi. 4. Fungal Systematics and Evolution 7: 255–343. 10.3114/fuse.2021.07.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Yu J, Chen S, Ding M, Huang X, Yuan J, She Z. (2017) Alkaloids from the mangrove endophytic fungus Diaporthephaseolorum SKS019. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 27(4): 803–807. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva RMF, Soares AM, Pádua APSL, Firmino AL, Souza-Motta CM, da Silva GA, Plautz Jr HL, Bezerra JDP, Paiva LM, Ryvarden L, Oliani LC, de Mélo MAC, Magalhães OMC, Pereira OL, Oliveira RJV, Gibertoni TB, Oliveira TGS, Svedese VM, Fan XL. (2019) Mycological Diversity Description II. Acta Botanica Brasílica 33(1): 163–173. 10.1590/0102-33062018abb0411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Silva NI, Maharachchikumbura SSN, Thambugala KM, Bhat DJ, Karunarathna SC, Tennakoon DS, Phookamsak R, Jayawardena RS, Lumyong S, Hyde KD. (2021) Morphomolecular taxonomic studies reveal a high number of endophytic fungi from Magnoliacandolli and M.garrettii in China and Thailand. Mycosphere: Journal of Fungal Biology 11(1): 163–237. 10.5943/mycosphere/12/1/3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding B, Wang Z, Xia G, Huang X, Xu F, Chen W, She Z. (2017) Three new chromone derivatives produced by Phomopsis sp. HNY29‐2B from Acanthusilicifolius Linn. Wiley Online Library 35(12): 1889–1893. 10.1002/cjoc.201700375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake AJ, Camporesi E, Hyde KD, Zhang W, Yan JY, Li XH. (2017) Molecular phylogenetic analysis reveals seven new Diaporthe species from Italy. Mycosphere: Journal of Fungal Biology 8(5): 853–877. 10.5943/mycosphere/8/5/4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake AJ, Chen Y-Y, Liu J-K. (2020) Unravelling Diaporthe species associated with woody hosts from karst formations (Guizhou) in China. Journal of Fungi 6: e251. 10.3390/jof6040251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Doilom M, Dissanayake AJ, Wanasinghe DN, Boonmee S, Liu J-K, Bhat DJ, Taylor JE, Bahkali AH, McKenzie EHC, Hyde KD. (2017) Microfungi on Tectonagrandis (teak) in Northern Thailand. Fungal Diversity 82: 107–182. [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Manawasinghe IS, Huang Y, Shu Y, Phillips AJL, Dissanayake AJ, Hyde KD, Xiang M, Luo M. (2021) Endophytic Diaporthe associated with Citrusgrandis cv. tomentosa in China. Frontiers in Microbiology 11: e3621. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.609387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Elsässer B, Krohn K, Flörke U, Root N, Aust HJ, Draeger S, Schulz B, Antus S, Kurtán T. (2005) X-ray structure determination, absolute configuration and biological activity of Phomoxanthone A. European Journal of Organic Chemistry 2005(21): 4563–4570. 10.1002/ejoc.200500265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X-X, Chen J-J, Wang G-R, Cao T-T, Zheng Y-L, Zhang C-L. (2019) Diaporthesinensis, a new fungus from Amaranthus sp. in China. Phytotaxa 425(5): 259–268. 10.11646/phytotaxa.425.5.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Liu F, Cai L. (2016) Unravelling Diaporthe species associated with Camellia. Systematics and Biodiversity 14(1): 102–117. 10.1080/14772000.2015.1101027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao YH, Liu F, Duan W, Crous PW, Cai L. (2017) Diaporthe is paraphyletic. IMA Fungus 8(1): 153–187. 10.5598/imafungus.2017.08.01.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass NL, Donaldson GC. (1995) Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 61(4): 1323–1330. 10.1128/aem.61.4.1323-1330.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes RR, Glienke C, Videira SIR, Lombard L, Groenewald JZ, Crous PW. (2013) Diaporthe: A genus of endophytic, saprobic and plant pathogenic fungi. Persoonia 31(1): 1–41. 10.3767/003158513X666844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaccia V, Crous PW. (2017) Emerging citrus diseases in Europe caused by Diaporthe spp. IMA Fungus 8(2): 317–334. 10.5598/imafungus.2017.08.02.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaccia V, Groenewald JZ, Woodhall J, Armengol J, Cinelli T, Eichmeier A, Ezra D, Fontaine F, Gramaje D, Gutierrez-Aguirregabiria A, Kaliterna J, Kiss L, Larignon P, Luque J, Mugnai L, Naor V, Raposo R, Sándor E, Váczy KZ, Crous PW. (2018) Diaporthe diversity and pathogenicity revealed from a broad survey of grapevine diseases in Europe. Persoonia 40(1): 135–153. 10.3767/persoonia.2018.40.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilário S, Amaral IA, Gonçalves MFM, Lopes A, Santos L, Alves A. (2020) Diaporthe species associated with twig blight and dieback of Vacciniumcorymbosum in Portugal, with description of four new species. Mycologia 112(2): 293–308. 10.1080/00275514.2019.1698926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Hou X, Dewdney MM, Fu Y, Chen G, Hyde KD, Li H. (2013) Diaporthe species occurring on citrus in China. Fungal Diversity 61(1): 237–250. 10.1007/s13225-013-0245-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Udayanga D, Wang X, Hou X, Mei X, Fu Y, Hyde KD, Li H. (2015) Endophytic Diaporthe associated with Citrus, a phylogenetic reassessment with seven new species from China. Fungal Biology 119(5): 331–347. 10.1016/j.funbio.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Xia J, Zhang X, Sun W. (2021) Morphological and phylogenetic analyses reveal three new species of Diaporthe from Yunnan, China. MycoKeys 78: 49–77. 10.3897/mycokeys.78.60878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde KD, Chaiwan N, Norphanphoun C, Boonmee S, Camporesi E, Chethana KWT, Dayarathne MC, de Silva NI, Dissanayake AJ, Ekanayaka AH, Hongsanan S, Huang SK, Jayasiri SC, Jayawardena RS, Jiang HB, Karunarathna A, Lin CG, Liu JK, Liu NG, Lu YZ, Luo ZL, Maharachchimbura SSN, Manawasinghe IS, Pem D, Perera RH, Phukhamsakda C, Samarakoon MC, Senwanna C, Shang QJ, Tennakoon DS, Thambugala KM, Tibpromma S, Wanasinghe DN, Xiao YP, Yang J, Zeng XY, Zhang JF, Zhang SN, Bulgakov TS, Bhat DJ, Cheewangkoon R, Goh TK, Jones EBG, Kang JC, Jeewon R, Liu ZY, Lumyong S, Kuo CH, McKenzie EHC, Wen TC, Yan JY, Zhao Q. (2018) Mycosphere notes 169–224. Mycosphere: Journal of Fungal Biology 9(2): 271–430. 10.5943/mycosphere/9/2/8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde KD, Dong Y, Phookamsak R, Jeewon R, Bhat DJ, Jones EBG, Liu N-G, Abeywickrama PD, Mapook A, Wei D, Perera RH, Manawasinghe IS, Pem D, Bundhun D, Karunarathna A, Ekanayaka AH, Bao D-F, Li J, Samarakoon MC, Chaiwan N, Lin C-G, Phutthacharoen K, Zhang S-N, Senanayake IC, Goonasekara ID, Thambugala KM, Phukhamsakda C, Tennakoon DS, Jiang H-B, Yang J, Zeng M, Huanraluek N, Liu J-KJ, Wijesinghe SN, Tian Q, Tibpromma S, Brahmanage RS, Boonmee S, Huang S-K, Thiyagaraja V, Lu Y-Z, Jayawardena RS, Dong W, Yang E-F, Singh SK, Singh SM, Rana S, Lad SS, Anand G, Devadatha B, Niranjan M, Sarma VV, Liimatainen K, Aguirre-Hudson B, Niskanen T, Overall A, Alvarenga RLM, Gibertoni TB, Pfliegler WP, Horváth E, Imre A, Alves AL, da Silva Santos AC, Tiago PV, Bulgakov TS, Wanasinghe DN, Bahkali AH, Doilom M, Elgorban AM, Maharachchikumbura SSN, Rajeshkumar KC, Haelewaters D, Mortimer PE, Zhao Q, Lumyong S, Xu J, Sheng J. (2020) Fungal diversity notes 1151–1276: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions on genera and species of fungal taxa. Fungal Diversity 100(1): 5–277. 10.1007/s13225-020-00439-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iantas J, Savi DC, Schibelbein Rd S, Noriler SA, Assad BM, Dilarri G, Ferreira H, Rohr J, Thorson JS, Shaaban KA, Glienke C. (2021) Endophytes of Brazilian medicinal plants with activity against phytopathogens. Frontiers in Microbiology 12: e714750. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.714750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Isaka M, Jaturapat A, Rukseree K, Danwisetkanjana K, Tanticharoen M, Thebtaranonth Y. (2001) Phomoxanthones A and B, novel xanthone dimers from the endophytic fungus Phomopsis species. Journal of Natural Products 64(8): 1015–1018. 10.1021/np010006h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouda JB, Tamokou J de D, Mbazoa CD, Douala-Meli C, Sarkar P, Bag PK, Wandji J. (2016) Antibacterial and cytotoxic cytochalasins from the endophytic fungus Phomopsis sp. harbored in Garciniakola (Heckel) nut. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 16(1): 1–9. 10.1186/s12906-016-1454-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakeya H, Morishita M, Onozawa C, Usami R, Horikoshi K, Kimura KI, Yoshihama M, Osada H. (1997) RKS-1778, a new mammalian cell-cycle inhibitor and a key intermediate of the [11]cytochalasin group. Journal of Natural Products 60(7): 669–672. 10.1021/np970151o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. (2017) ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nature Methods 14(6): 587–589. 10.1038/nmeth.4285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM. (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software v. 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30(4): 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Mentjies P, Drummond A. (2012) Geneious basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 28(12): 1647–1649. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretz R, Wendt L, Wongkanoun S, Luangsa-Ard JJ, Surup F, Helaly SE, Noumeur SR, Stadler M, Stradal TEB. (2019) The effect of cytochalasans on the actin cytoskeleton of eukaryotic cells and preliminary structure-activity relationships. Biomolecules 9(2): e73. 10.3390/biom9020073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. (2018) MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary Genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35(6): 1547–1549. 10.1093/molbev/msy096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfear R, Frandsen PB, Wright AM, Senfeld T, Calcott B. (2016) PartitionFinder 2: new methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Molecular Biology and Evolution 34: 772–773. 10.1093/molbev/msw260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WJ, McKenzie EHC, Liu JK, Bhat DJ, Dai D-Q, Camporesi E, Tian Q, Maharachchikumbura SSN, Luo Z-L, Shang Q-J, Zhang J-F, Tangthirasunun N, Karunarathna SC, Xu J-C, Hyde KD. (2020) Taxonomy and phylogeny of hyaline-spored coelomycetes. Fungal Diversity 100(1): 279–801. 10.1007/s13225-020-00440-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C, Kim J, Choi JN, Ponnusamy K, Jeon Y, Kim SU, Kim JG, Lee CH. (2010) Identification, fermentation, and bioactivity against Xanthomonasoryzae of antimicrobial metabolites isolated from Phomopsislongicolla S1B4. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 20: 494–500. 10.4014/JMB.0909.09026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]