Abstract

The alkoxy substituents at C4 and C2 of septanoses control the stereochemical outcomes of O-glycosylation reactions of these seven-membered ring intermediates. Isolation of a bicyclic acetal byproduct in some substitution reactions suggests that the C4 benzyloxy substituent engaged in long-range participation, stabilizing intermediates by formation of an oxonium ion intermediate. Inductive destabilization of the carbocationic intermediate provided by the C2 substituent is crucial to the participation of the remote alkoxy group.

Graphical Abstract

Nucleophilic substitution reactions of seven-membered-ring acetals are useful transformation for the synthesis of a variety of oxepanes.1–3 The stereoselectivity of substitution reactions in seven-membered rings is often higher than it is for six-membered rings, as illustrated by the O-glycosylation of septanoses 1 (Figure 1).4–6 To date, the origin of the high diastereoselectivity in glycosylations of septanoses has not been explained.

Figure 1.

Higher diastereoselectivity in glycosylation of septanoses compared to that of pyranoses.

In this paper, we report that the high stereoselectivity of glycosylation of benzyl-protected septanoses is controlled by remote participation of a benzyloxy group at C4. This remote participation induces 1,4-trans selectivity even though alkoxy groups are considered to be non-participating functional groups.7 The remote participation by an alkoxy group contrasts with the unreliability of even strongly participating acyloxy groups to control selectivity through remote participation in six-membered systems (Figure 2, acetals 3 vs 4)8 or neighboring-group participation in seven-membered systems (Figure 2, acetals 5 vs 6).4 Remote participation of the C4 alkoxy group relied on the presence of another alkoxy group to destabilize the oxocarbenium ion intermediates inductively.

Figure 2.

The effect of participation from the acyloxy group on the stereoselectivity is substrate-dependent.

Our approach to determine the origin of stereoselectivity in glycosylation reactions such as those used to form septanose 1 involved studies of substrates with fewer substituents. Conclusions drawn from reactions of substrates with a single substituent could not be extrapolated to explain the stereoselective formation of acetal 1.9 In particular, the presence of alkoxy groups on homovicinal carbon atoms (i.e., in a 1,3-relationship) could result in destabilizing 1,3-diaxial interactions if the substituents both adopted their favored axial orientations.9,10 To examine the possibility that 1,3-interactions were responsible for stereoselectivity, substitution reactions were studied using disubstituted septanoses that contained only these homovicinal alkoxy substituents (Scheme 1)

Scheme 1.

Syntheses of acetal and thioacetal substrates.

The outcomes of C-glycosylation reactions of the cis-3,5-disubstituted acetal 8 depended upon the nucleophile employed. Reactions with a weak nucleophile, allyltrimethylsilane, proceeded with trans diastereoselectivity (Table 1, entries 1A and 1B). The diastereoselectivity in the absence of triflate ions decreased with increasing reactivity of the nucleophile (entries 2A-4A), which suggests that these reactions proceeded via oxocarbenium ion intermediates.9,11 In the presence of a triflate ion in a highly non-polar solvent, which should favor the anomeric triflates,12 stronger nucleophiles reacted with the opposite diastereoselectivity, favoring the 1,3-cis/1,5-cis product (entries 2B-4B).

Table 1.

C-Glycosylations of cis-3,5-dibenzyoxy oxepane acetal.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| trans-13 : cis-13b | ||||

| Entry | Nucleophile | Na | Without TfOc (A) | With TfOd (B) |

| 1 | 14 | 1.68 | 90 : 10 | 87 : 13 |

| 2 | 15 | 4.41 | 83 : 17 | 32 : 68 |

| 3 | 16 | 9.00 | 82 : 18 | ≤ 3 : 97 |

| 4 | 17 | 10.32 | 56 : 44 | 16 : 84 |

Nucleophilicity parameters; higher N number indicates higher nucleophilicity.13

Diastereomeric ratios were determined from 13C and 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of the crude product mixture.14 Relative stereochemistry was determined by J coupling constants and NOE experiments.15

BF3•OEt2, CH2Cl2, −78 °C.

Me3SiOTf, Cl2CCHCl, −78 °C.

Similar trends in diastereoselectivity were observed for O-glycosylation reactions with various alcohols (Table 2). The weakly nucleophilic alcohol hexafluoroisopropanol reacted with thioacetal 9 with high 1,3-trans/1,5-trans diastereoselectivity (entry 1A), which diminished when stronger nucleophiles were used (entries 2A-6A). In the presence of triflate ions, 1,3-cis/1,5-cis stereoselectivity was observed only for reactions of the somewhat stronger nucleophiles trifluoroethanol and 2,2-difluoroethanol (entries 2B-3B). As nucleophilicity of the alcohol increased further, however, stereoselectivity decreased (entries 4B-6B). Control experiments indicated that all of these products were formed in reactions under kinetic control and supported the hypothesis that the loss of stereochemical control as nucleophilicity increased was consistent with reaction rates of addition of the alcohol to the oxocarbenium ion approaching the diffusion limit.15

Table 2.

O-Glycosylations of cis-3,5-dibenzyoxy oxepane thioacetal

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| trans-13 : cis-13b | ||||

| Entry | Nucleophile | Fa | Without TfOc (A) | With TfOd (B) |

| 1 | 18 | > 0.38 | 84 : 16 | 82 : 18 |

| 2 | 19 | 0.38 | 52 : 48 | 16 : 84 |

| 3 | 20 | 0.29 | 47 : 53 | 8 : 92 |

| 4 | 21 | 0.15 | 52 : 48 | 52 : 48 |

| 5 | 22 | 0.13 | 47 : 53 | 68 : 32 |

| 6 | 23 | 0 | 41 : 59 | 66 : 34 |

Field inductive effect parameter of R2; lower F value indicates higher nucleophilicity.16

Diastereomeric ratios were determined from 13C and 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of the crude product mixture.14 Relative stereochemistry was determined by J coupling constants and NOE experiments.15

NIS, CH2Cl2, −78 °C.

NIS, AgOTf, CH2Cl2, −40 °C.

The high trans stereoselectivity of reactions of cis-3,5-dibenzyloxyoxepane acetals 8 and thioacetal 9 with weak nucleophiles can be explained by considering the stereoelectronic model of reactions of seven-membered oxocarbenium ions.9 Oxocarbenium intermediate 24a likely adopts a chair conformation that positions both the C3 and C5 benzyloxy groups in pseudoaxial orientations (Scheme 2). The electrostatic stabilization provided by the oxygen atoms of the pseudoaxial benzyloxy substituents to the positively charged anomeric carbon atom17 is likely strong enough to compensate for the unfavorable 1,3-diaxial interaction developed between these substituents.18 These predictions are supported by computational analysis, which suggested that 24a is the lowest energy conformer (2.6 kcal/mol lower than the diequatorial conformer).19 Weak nucleophiles react with oxocarbenium ion 24a along the torsionally favored trajectory A (Scheme 2), which forms the product in the lowest-energy twist-chair conformation trans-13.18 Trajectory B is torsionally disfavored because the resulting product cis-13 would experience destabilizing 1,3-diaxial and 1,4-transannular interactions.18 With strong nucleophiles, both trajectories A and B are accessible because the rate of bond formation is likely faster than separation of any encounter complex between the reactants,20 resulting in loss of stereoselectivity (Table 1, entry 4A;Table 2, entries 2A-6A).

Scheme 2.

SN1- and SN2-like pathways of the diaxial cis-3,5-dibenzyloxy acetal

The 1,3-cis/1,5-cis stereoselectivities observed for the reactions of some nucleophiles in the presence of the triflate ion corresponds to an SN2-like pathway with either the contact ion pair intermediate 24b or the covalent triflate (Scheme 2).21,22 The triflate ion occupies the torsionally favored bottom face, leading to an approach of the nucleophile from the opposite face (Scheme 2, trajectory C).9 This SN2-like displacement of the ion pair 24b likely has a higher energy barrier than that of the nucleophilic addition to oxocarbenium ion 24a.23 Such an energy barrier could not be overcome by the weakly nucleophilic hexafluoroisopropanol and only stronger nucleophiles such as trifluoroethanol, 2,2-difluoroethanol, and silyl ketene acetals 16 and 17 can react via this SN2 pathway. The decreased diastereoselectivity observed with the most reactive nucleophiles (Table 2, entries 4B-6B;Table 1, entry 4B) can be explained by considering a front-side substitution on the ion pair (trajectory D),24,25 which becomes competitive as nucleophilicity increased further. The high 1,3-cis/1,5-cis stereoselectivity with the most sterically hindered nucleophile (Table 1, entry 3B) may reflect steric hindrance to that front-side attack, leading to exclusive back-side displacement.

Taken together, the results with the cis-3,5-disubstituted septanoses are not fully consistent with the stereoselectivity observed for the formation of fully substituted septanose 1. O-Glycosylation of a septanose with a substitution pattern similar to septanose 1 led to 1,3-cis/1,5-cis stereoselectivity exclusively even in the absence of the triflate ion, which contradicts the selectivity observed for the cis-3,5-dibenzyloxy acetal 9 (Table 2).26 Consequently, the origin of consistently high stereoselectivity for the formation of products such as 1 do not appear to be controlled by just these two substituents.

By contrast, reactions of the cis-2,4-dialkoxy septanoses, particularly the O-glycosylation reactions, provided results that are more consistent with the chemistry of the fully substituted system. C-Glycosylation reactions of cis-2,4-dialkoxy oxepane acetal 11 proceeded with high 1,2-trans/1,4-trans stereoselectivity only with allyltrimethylsilane, and stereoselectivity decreased with increased nucleophilicity (Table 3). In the presence of the triflate counterion, selectivities were similar, suggesting that contact ion pairs or anomeric triflates are unlikely to be important reactive intermediates.

Table 3.

C-Glycosylations of cis-2,4-dibenzyoxy oxepane acetal

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| trans-25 : cis-25b | ||||

| Entry | Nucleophile | Na | Without TfOc (A) | With TfOd (B) |

| 1 | 14 | 1.68 | 88 : 12 | 94 : 6 |

| 2 | 15 | 4.41 | 59 : 41 | 58 : 42 |

| 3 | 16 | 9.00 | 75 : 25 | 82 : 18 |

| 4 | 17 | 10.32 | 50 : 50 | 50 : 50 |

Nucleophilicity parameters; higher N number indicates higher nucleophilicity.13

Diastereomeric ratios were determined from 13C and 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of the crude product mixture.14 Relative stereochemistry was determined by J coupling constants and NOE experiments.15

BF3•OEt2, CH2Cl2, −78 °C.

Me3SiOTf, Cl2CCHCl, −78 °C.

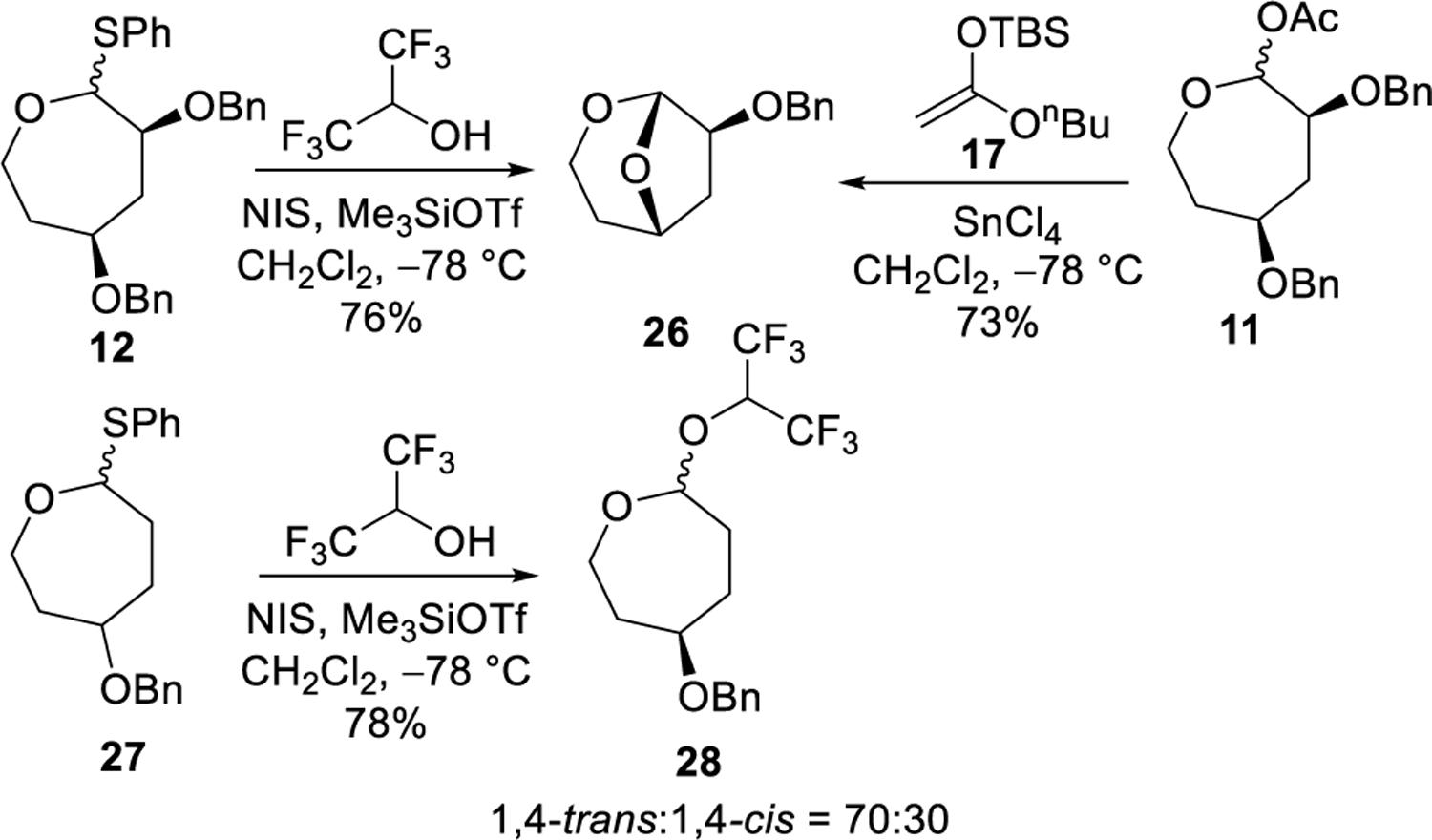

The isolation of an intermediate in some of the substitution reactions of the 2,4-dialkoxy oxepane acetals provided evidence for long-range participation by the alkoxy group at C4. The reaction of acetal 11 with nucleophile 17 in the presence of SnCl4 gave the bicyclic acetal 26 (Scheme 3) and BnCl. The same bicyclic acetal was observed upon substitution with hexafluoroisopropanol in the presence of Me3SiOTf. The comparable reaction of the 4-alkoxy acetal 27, however, provided no bicyclic products, instead forming the substitution product 28. The formation of the bicyclic acetal 26 could result from participation of the alkoxy group at C4 followed by debenzylation, as has been suggested for other reactions of septanoses27 and other reactions involving participation of a benzyloxy group.28–33 The fact that the bridged acetal 26 was not formed in reactions of C4 benzyloxy acetal 27 suggests that long-range participation of the alkoxy group is itself not strong, but instead is only possible when an electron-withdrawing substituent is present to destabilize an oxocarbenium ion intermediate.

Scheme 3.

Oxonium ion formation and debenzylation

O-Glycosylation reactions of cis-2,4-dialkoxy oxepane thioacetal 12 proceeded with 1,2-trans/1,4-trans stereoselectivity (Table 4). The presence of the triflate counterion generally increased the 1,2-trans/1,4-trans selectivity instead of leading to a reversal of selectivity. Reactions of cis-2,4 thioacetal 12 with trifluoroethanol and 2,2-difluoroethanol (Table 4, entries 2A-3A), whose nucleophilicities are most similar to that of a carbohydrate nucleophile,34 resulted in higher stereoselectivity compared to the reactions with the cis-3,5 thioacetals 9 (Table 2, entries 2A-3A).

Table 4.

O-Glycosylations of cis-2,4-dibenzyoxy oxepane thioacetal

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| trans-25 : cis-25b | ||||

| Entry | Nucleophile | Fa | Without TfOc (A) | With TfOd (B) |

| 1 | 18 | > 0.38 | ≥ 97 : 3 | ≥ 97 : 3 |

| 2 | 19 | 0.38 | 82 : 18 | ≥ 97 : 3 |

| 3 | 20 | 0.29 | 82 : 18 | 91 : 9 |

| 4 | 21 | 0.15 | 65 : 35 | 81 : 19 |

| 5 | 22 | 0.13 | 60 : 40 | 70 : 30 |

| 6 | 23 | 0 | 66 : 34 | 66 : 34 |

Field inductive effect parameter of R2; lower F value indicates higher nucleophilicity.16

Diastereomeric ratios were determined from 13C and 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of the crude product mixture.14 Relative stereochemistry was determined by J coupling constants and NOE experiments.15

NIS, CH2Cl2, −78 °C.

NIS, AgOTf, CH2Cl2, −40 °C.

The stereoselectivities of reactions of cis-2,4-dialkoxy acetal 11 and thioacetal 12 are consistent with reactions that proceed through the unsymmetric oxonium ion 30 and diaxial oxocarbenium ion 29 (Scheme 4). Computational analysis suggests that oxonium ion 30 is a low-energy intermediate, but the more reactive oxocarbenium ion 29 is only 9.9 kcal/mol higher, which could be accessible even at low temperatures.19 The formation of the 1,2-cis/1,4-cis product in some cases is likely a result of a reaction through the highly reactive oxocarbenium ion 29 (pathway F) and is sensitive to the size of the nucleophile. The highly reactive but bulky nucleophile 16 therefore, reacted with moderate trans selectivity due to the steric hindrance provided by the C2 and C4 substituents. Compared to the cis-2,4-dialkoxy acetal 11, fully substituted septanoses likely favored the oxonium ion even more than the oxocarbenium ion due to the presence of a greater number of inductively withdrawing groups destabilizing the oxocarbenium ion. This increased preference for the bridged oxonium ion of the fully substituted septanoses could explain why high stereoselectivity was observed even with strong nucleophiles,4 in contrast to the decline in stereoselectivity observed for acetal 11 and thioacetal 12. The lack of significant changes in selectivity when the triflate ion is present suggests that remote participation from the C4 benzyloxy substituent is preferred over stabilization by the triflate anion.36,37

Scheme 4.

Glycosylation pathways involving cis-2,4 oxocarbenium ion and cis-2,4 unsymmetric oxonium ion35

In conclusion, the C4 and C2 positions were determined to be the most important positions in determining the stereoselectivity of O-glycosylation reactions of septanoses. The C4 benzyloxy group imposes 1,4-trans stereoselectivity by stabilizing the positively charged carbon center via a bridged oxonium ion intermediate. The formation of this intermediate depends on the presence of an inductively withdrawing group at C2, which destabilizes the oxocarbenium ion intermediate. High diastereoselectivity eventually diminishes when strong nucleophiles react at rates approaching the diffusion limit. The inductive assistance of remote participation38 is likely also provided by substituents further from the oxocarbenium ion carbon center, although to a lesser extent.39,40

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1R01GM129286). The authors acknowledge NYU’s Shared Instrumentation Facility and the support provided by NSF award CHE-01162222 and NIH award S10-OD016343. The authors thank Dr. Chin Lin (NYU) for his assistance with NMR spectroscopy and mass spectroscopy.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Detailed experimental procedure, computational analysis, 1H and 13C NMR spectra of new compounds (PDF).

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

REFERENCES

- (1).Gurjar MK; Rao BV; Krishna LM; Chorghade MS; Ley SV Stereoselective synthesis of (2S,7S)-7-(4-phenoxymethyl)-2-(1-N-hydroxyureidyl-3-butyn-4-yl)oxepane: a potential anti-asthmatic drug candidate. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2005, 16, 935–939. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Boone MA; McDonald FE; Lichter J; Lutz S; Cao R; Hardcastle KI 1,5-α-d-Mannoseptanosides, Ring-Size Isomers That Are Impervious to α-Mannosidase-Catalyzed Hydrolysis. Org. Lett 2009, 11, 851–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Sabatino D; Damha MJ Oxepane Nucleic Acids: Synthesis, Characterization, and Properties of Oligonucleotides Bearing a Seven-Membered Carbohydrate Ring. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 8259–8270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Castro S; Fyvie WS; Hatcher SA; Peczuh MW Synthesis of α-D-Idoseptanosyl Glycosides Using an S-Phenyl Septanoside Donor. Org. Lett 2005, 7, 4709–4712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Takeo K; Teramoto Y; Shimono Y; Nitta Y Synthesis of the oligosaccharides α-d-Glcp(1→4)-D-Xylp, α-D-Xylp-(1→4)-D-Glcp, α-D-Glcp-(1→4)-α-D-Glcp-(1→4)-D-Xylp, α-D-Glcp-(1→4)-α-D-Xylp-(1→4)-D-Glcp, and α-D-Xylp-(1→4)-α-D-Glcp-(1→4)-D-Glcp. Carbohydr. Res 1991, 209, 167–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Cai D; Bian Y; Wu S; Ding K Conformation-Controlled Hydrogen-Bond-Mediated Aglycone Delivery Method for α-Xylosylation. J. Org. Chem 2021, 86, 9945–9960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Guberman M; Seeberger PH Automated Glycan Assembly: A Perspective. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 5581–5592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hansen T; Elferink H; van Hengst JMA; Houthuijs KJ; Remmerswaal WA; Kromm A; Berden G; van der Vorm S; Rijs AM; Overkleeft HS; Filippov DV; Rutjes FPJT; van der Marel GA; Martens J; Oomens J; Codée JDC; Boltje TJ Characterization of glycosyl dioxolenium ions and their role in glycosylation reactions. Nat. Commun 2020, 11, 2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Beaver MG; Buscagan TM; Lavinda O; Woerpel KA Stereoelectronic Model To Explain Highly Stereoselective Reactions of Seven-Membered-Ring Oxocarbenium-Ion Intermediates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 1816–1819; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 2016, 128,1848–1851. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Lucero CG; Woerpel KA Stereoselective C-Glycosylation Reactions of Pyranoses: The Conformational Preference and Reactions of the Mannosyl Cation. J. Org. Chem 2006, 71, 2641–2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Franconetti A; Ardá A; Asensio JL; Blériot Y; Thibaudeau S; Jiménez-Barbero J Glycosyl Oxocarbenium Ions: Structure, Conformation, Reactivity, and Interactions. Acc. Chem. Res 2021, 54, 2552–2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Kendale JC; Valentín EM; Woerpel KA Solvent Effects in the Nucleophilic Substitutions of Tetrahydropyran Acetals Promoted by Trimethylsilyl Trifluoromethanesulfonate: Trichloroethylene as Solvent for Stereoselective C- and O-Glycosylations. Org. Lett 2014, 16, 3684–3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Mayr H; Bug T; Gotta MF; Hering N; Irrgang B; Janker B; Kempf B; Loos R; Ofial AR; Remennikov G; Schimmel H Reference Scales for the Characterization of Cationic Electrophiles and Neutral Nucleophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 9500–9512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Otte DAL; Borchmann DE; Lin C; Weck M; Woerpel KA 13C NMR Spectroscopy for the Quantitative Determination of Compound Ratios and Polymer End Groups. Org. Lett 2014, 16, 1566–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15). Details are provided as supporting information.

- (16).Hansch C; Leo A; Taft RW A survey of Hammett substituent constants and resonance and field parameters. Chem. Rev 1991, 91, 165–195. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Chamberland S; Ziller JW; Woerpel KA Structural Evidence that Alkoxy Substituents Adopt Electronically Preferred Pseudoaxial Orientations in Six-Membered Ring Dioxocarbenium Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 5322–5323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Espinosa A; Gallo MA; Entrena A; Gómez JA Theoretical conformational analysis of seven-membered rings. V. MM2 and MM3 study of oxepane. J. Mol. Struct 1994, 323, 247–256. [Google Scholar]

- (19). Energy calculations were performed using B3LYP-D3 functional, 6–311+G(2df,2p) basis set and the SMD model for THF.

- (20).Beaver MG; Woerpel KA Erosion of Stereochemical Control with Increasing Nucleophilicity: O-Glycosylation at the Diffusion Limit. J. Org. Chem 2010, 75, 1107–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Krumper JR; Salamant WA; Woerpel KA Continuum of Mechanisms for Nucleophilic Substitutions of Cyclic Acetals. Org. Lett 2008, 10, 4907–4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Santana AG; Montalvillo-Jiménez L; Díaz-Casado L; Corzana F; Merino P; Cañada FJ; Jiménez-Osés G; Jiménez-Barbero J; Gómez AM; Asensio JL Dissecting the Essential Role of Anomeric β-Triflates in Glycosylation Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 12501–12514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Fu Y; Bernasconi L; Liu P Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the SN1/SN2 Mechanistic Continuum in Glycosylation Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 1577–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Liras JL; Lynch VM; Anslyn EV The Ratio between Endocyclic and Exocyclic Cleavage of Pyranoside Acetals Is Dependent upon the Anomer, the Temperature, the Aglycon Group, and the Solvent. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 8191–8200. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Garcia A; Sanzone JR; Woerpel KA Participation of Alkoxy Groups in Reactions of Acetals: Violation of the Reactivity/Selectivity Principle in a Curtin–Hammett Kinetic Scenario. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 12087–12090; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 2015, 127, 12255–12258. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Saha J; Peczuh MW Glycosylations with a septanosyl fluoride donor lacking a C2 protecting group. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 5667–5670. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Vannam R; Pote AR; Peczuh MW Formation and selective rupture of 1,4-anhydroseptanoses. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 418–425. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Chao C-S; Lin C-Y; Mulani S; Hung W-C; Mong K.-k. T. Neighboring-Group Participation by C-2 Ether Functions in Glycosylations Directed by Nitrile Solvents. Chem. Eur. J 2011, 17, 12193–12202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Garcia A; Otte DAL; Salamant WA; Sanzone JR; Woerpel KA Influence of Alkoxy Groups on Rates of Acetal Hydrolysis and Tosylate Solvolysis: Electrostatic Stabilization of Developing Oxocarbenium Ion Intermediates and Neighboring-Group Participation To Form Oxonium Ions. J. Org. Chem 2015, 80, 4470–4480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Ramdular A; Woerpel KA Diastereoselective Substitution Reactions of Acyclic β-Alkoxy Acetals via Electrostatically Stabilized Oxocarbenium Ion Intermediates. Org. Lett 2022, 24, 3217–3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Siyabalapitiya Arachchige S; Crich D Side Chain Conformation and Its Influence on Glycosylation Selectivity in Hexo- and Higher Carbon Furanosides. J. Org. Chem 2022, 87, 316–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Persky R; Albeck A An Unexpected Rearrangement during Mitsunobu Epimerization Reaction of Sugar Derivatives. J. Org. Chem 2000, 65, 3775–3780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Martin OR; Feng Y; Fang X Spontaneous cyclization of triflates derived from δ-benzyloxy alcohols: Efficient and general synthesis of C-vinyl furanosides. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- (34).van der Vorm S; Hansen T; Overkleeft HS; van der Marel GA; Codée JDC The influence of acceptor nucleophilicity on the glycosylation reaction mechanism. Chem. Sci 2017, 8, 1867–1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35). Structure calculations were performed using ωB97X-D functional and 6–31G* basis set.

- (36).Mensink RA; Elferink H; White PB; Pers N; Rutjes FPJT; Boltje TJ A Study on Stereoselective Glycosylations via Sulfonium Ion Intermediates. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2016, 2016, 4656–4667. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Zeng Y; Wang Z; Whitfield D; Huang X Installation of Electron-Donating Protective Groups, a Strategy for Glycosylating Unreactive Thioglycosyl Acceptors using the Preactivation-Based Glycosylation Method. J. Org. Chem 2008, 73, 7952–7962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Lambert JB; Mark HW; Holcomb AG; Magyar ES Inductive enhancement of neighboring group participation. Acc. Chem. Res 1979, 12, 317–324. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Namchuk MN; McCarter JD; Becalski A; Andrews T; Withers SG The Role of Sugar Substituents in Glycoside Hydrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 1270–1277. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Withers SG; MacLennan DJ; Street IP The synthesis and hydrolysis of a series of deoxyfluoro-d-glucopyranosyl phosphates. Carbohydr. Res 1986, 154, 127–144. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.